Statistical Validation of NPDOA: A Novel Brain-Inspired Metaheuristic for Optimization in Drug Discovery

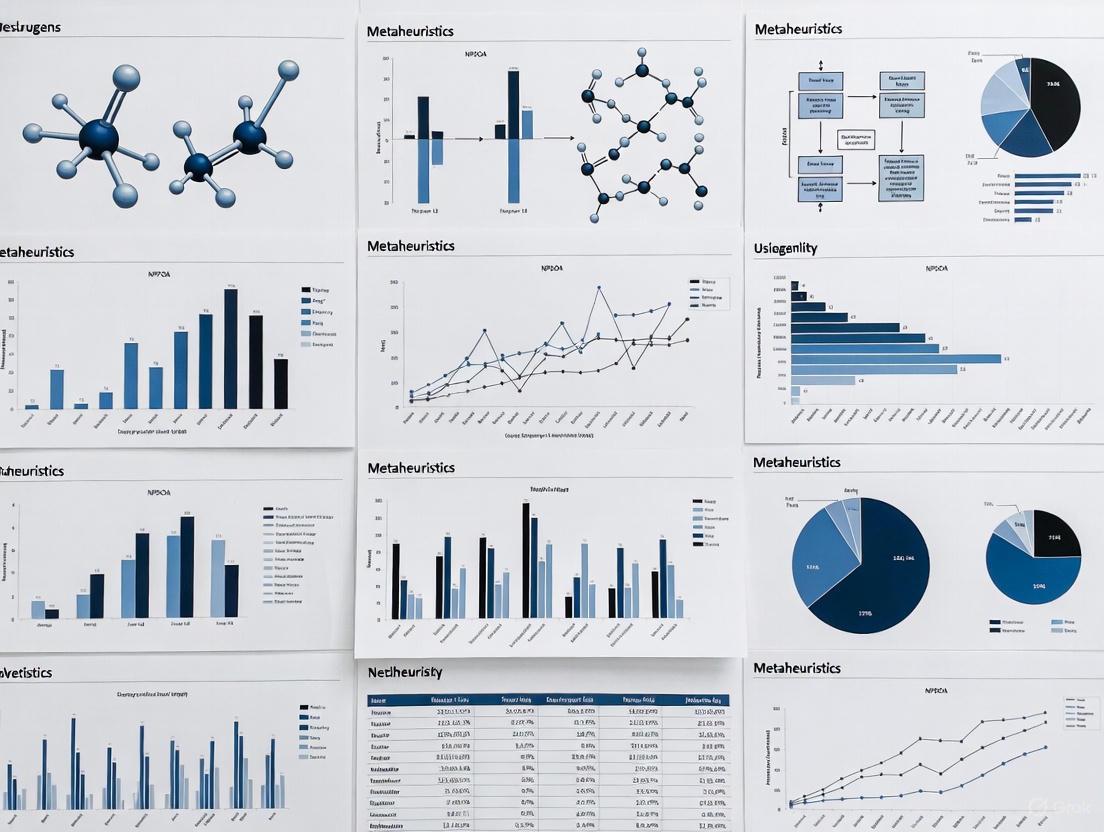

This article provides a comprehensive statistical evaluation of the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA), a novel brain-inspired metaheuristic, against state-of-the-art optimization techniques.

Statistical Validation of NPDOA: A Novel Brain-Inspired Metaheuristic for Optimization in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive statistical evaluation of the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA), a novel brain-inspired metaheuristic, against state-of-the-art optimization techniques. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, we explore NPDOA's foundational principles inspired by neural population dynamics and its application to complex biomedical problems like protein structure prediction and small molecule generation. The content details methodological implementation, addresses common optimization challenges such as premature convergence, and presents rigorous statistical validation using benchmark functions and real-world case studies. By demonstrating NPDOA's competitive performance and practical utility in accelerating drug discovery pipelines, this work establishes a framework for robust metaheuristic evaluation in computational biology.

Understanding NPDOA: A Brain-Inspired Metaheuristic for Complex Optimization

Metaheuristic algorithms are advanced optimization techniques designed to solve complex problems where traditional deterministic methods often fail. These stochastic algorithms are inspired by various natural, physical, or social phenomena, and are characterized by their ability to explore large solution spaces effectively without requiring gradient information. The field has seen remarkable growth with algorithms now categorized into several groups including evolution-based algorithms (e.g., Genetic Algorithms), swarm intelligence algorithms (e.g., Particle Swarm Optimization), physics-based algorithms, human behavior-based algorithms (e.g., Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization), and mathematics-based algorithms [1] [2].

The fundamental principle behind metaheuristics is the balance between two crucial phases: exploration (diversifying the search across the solution space) and exploitation (intensifying the search around promising regions). According to the No Free Lunch (NFL) theorem, no single algorithm can outperform all others on every possible optimization problem, which continuously motivates the development of new metaheuristics tailored for specific problem characteristics or domains [1] [3].

Table 1: Major Categories of Metaheuristic Algorithms

| Category | Inspiration Source | Representative Algorithms | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evolution-based | Biological evolution | Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Uses selection, crossover, mutation; may converge prematurely [1] |

| Swarm Intelligence | Collective animal behavior | Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Ant Colony Optimization | Population-based, decentralized control, self-organization [1] [4] |

| Human Behavior-based | Social interactions | Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO), Hiking Optimization | No algorithm-specific parameters, mimics human problem-solving [1] [2] |

| Physics-based | Physical laws | Simulated Annealing, Gravitational Search Algorithm | Mimics natural physical processes [2] |

| Mathematics-based | Mathematical theorems | Power Method Algorithm (PMA), Newton-Raphson-Based Optimization | Built on rigorous mathematical foundations [1] |

Performance Comparison of Select Algorithms

Benchmark Studies and Quantitative Results

Comprehensive evaluations of metaheuristic algorithms typically employ standardized benchmark functions from test suites like CEC 2017, CEC 2022, and CEC 2024, which include unimodal, multimodal, hybrid, and composition functions designed to test various algorithm capabilities [1] [5]. Performance is measured through statistical tests including the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Friedman test, and Mann-Whitney U-score test to ensure robust comparisons [5].

Table 2: Performance Comparison on Benchmark Functions

| Algorithm | Average Friedman Ranking (CEC 2017/2022) | Key Strengths | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power Method Algorithm (PMA) | 2.71-3.00 (30D-100D) [1] | Excellent balance of exploration/exploitation, avoids local optima | Newer algorithm, less extensively applied |

| Parallel Sub-Class MTLBO | Ranked 1st in 80% of test functions [3] | 95% error reduction vs. traditional TLBO, high stability | Computational complexity from parallel structure |

| Differential Evolution Variants | Varies by specific variant [5] | Simple structure, effective for continuous spaces | Performance dependent on mutation strategy |

| Particle Swarm Optimization | Competitive in low-dimensional spaces [4] | Fast convergence, easy implementation | May premature converge on complex problems |

| Simulated Annealing | Superior in low-dimensional scenarios [6] | Strong local search capability | Performance declines in higher dimensions |

Performance in Real-World Applications

Table 3: Engineering Application Performance

| Application Domain | Best Performing Algorithms | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solar-Wind-Battery Microgrid | GD-PSO, WOA-PSO (Hybrid) | Lowest operational costs, strong stability | [7] |

| Model Predictive Control Tuning | PSO, Genetic Algorithm | PSO: <2% tracking error; GA: 16% to 8% error reduction | [8] |

| Parallel Machine Scheduling | Simulated Annealing (low-D), Tabu Search (high-D) | Superior solution quality in respective dimensions | [6] |

| Truss Topology Optimization | Parallel Sub-Class MTLBO | 7.2% weight reduction vs. previous best solutions | [3] |

| DC Microgrid Power Management | Particle Swarm Optimization | Under 2% power load tracking error | [8] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Algorithm Evaluation Framework

The experimental methodology for comparing metaheuristic algorithms follows rigorous statistical protocols to ensure meaningful results. The standard approach includes:

Performance Measurement Protocol: Each algorithm is run multiple times (typically 15-30 independent runs) on benchmark functions to account for stochastic variations. The mean, median, and standard deviation of the best solutions are recorded [5] [9].

Statistical Testing Pipeline:

- Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test: Used for pairwise comparisons of algorithm performance

- Friedman Test with Nemenyi Post-Hoc Analysis: Determines significant differences in multiple algorithm comparisons

- Mann-Whitney U-Score Test: Additional validation of performance differences [5]

Crossmatch Test: A nonparametric, distribution-free method for comparing multivariate distributions of solutions generated by different algorithms, helping identify algorithms with similar search behaviors [9].

Experimental Workflow for Metaheuristic Algorithm Comparison

Search Behavior Analysis

Recent approaches focus on comparing algorithms based on their search behavior rather than just final results. The crossmatch statistical test compares multivariate distributions of solutions generated by different algorithms during the optimization process. This method helps identify whether two algorithms explore the solution space in fundamentally different ways or exhibit similar search patterns [9].

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| CEC Benchmark Suites | Standardized test functions for algorithm validation | Unimodal, multimodal, hybrid, composition functions [1] [5] |

| Statistical Test Suites | Determine significant performance differences | Wilcoxon, Friedman, Mann-Whitney tests [5] |

| MEALPY Library | Comprehensive collection of metaheuristic algorithms | Contains 114 algorithms for comparative studies [9] |

| IOHExperimenter | Platform for performance data collection | Benchmarking and analysis of optimization algorithms [9] |

| BBOB Framework | Black-Box Optimization Benchmarking | 24 problem classes with multiple instances [9] |

Statistical Testing Framework for Algorithm Comparison

The comparative analysis of metaheuristic algorithms reveals that while mathematics-based algorithms like PMA show exceptional performance on standard benchmarks, hybrid approaches often excel in real-world engineering applications. The No Free Lunch theorem remains highly relevant, as algorithm performance is heavily dependent on problem characteristics.

Future research directions include developing more adaptive algorithms that can self-tune their parameters, creating advanced statistical comparison methods that analyze search behavior beyond final results, and addressing the "novelty crisis" in metaheuristics by focusing on truly innovative mechanisms rather than metaphorical variations of existing approaches [4] [9].

The field continues to evolve toward more rigorous testing methodologies and problem-specific adaptations, with hybrid algorithms showing particular promise for complex engineering optimization challenges across scientific and industrial domains.

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) represents a groundbreaking shift in metaheuristic research by drawing inspiration directly from the computational principles of the human brain. Unlike traditional nature-inspired algorithms that mimic animal swarms or evolutionary processes, NPDOA innovatively models its search strategies on the decision-making and information-processing activities of interconnected neural populations in the brain [10]. This brain neuroscience-inspired approach offers a novel framework for balancing the critical optimization components of exploration and exploitation through biologically-plausible mechanisms.

The algorithm treats each potential solution as a neural population, with decision variables representing individual neurons and their values corresponding to neuronal firing rates [10]. This conceptual mapping from neural activity to optimization parameters enables NPDOA to simulate the brain's remarkable ability to process complex information and arrive at optimal decisions. As theoretical neuroscience research has revealed, neural populations in the brain engage in sophisticated dynamics during cognitive tasks, and NPDOA translates these dynamics into effective optimization strategies [10].

Neuroscientific Foundations and Algorithmic Mechanisms

Core Inspirations from Brain Neuroscience

NPDOA's foundation rests on the population doctrine in theoretical neuroscience, which investigates how groups of neurons collectively perform sensory, cognitive, and motor computations [10]. The human brain demonstrates exceptional efficiency in processing diverse information types and making optimal decisions across varying situations [10]. NPDOA captures this capability through three principal strategies derived from neural population dynamics:

Attractor Trending Strategy: This component drives neural populations toward stable states associated with optimal decisions, mirroring how brain networks converge to represent perceptual interpretations or behavioral choices [10].

Coupling Disturbance Strategy: This mechanism introduces controlled disruptions that prevent premature convergence by deviating neural populations from attractors, analogous to neural variability that facilitates exploratory behavior in biological systems [10].

Information Projection Strategy: This component regulates communication between neural populations, enabling smooth transitions from exploration to exploitation phases by controlling how information flows between different population states [10].

Comparative Algorithmic Taxonomy

Table 1: Classification of Metaheuristic Algorithms Based on Inspiration Sources

| Category | Inspiration Source | Representative Algorithms | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evolution-based | Biological evolution | Genetic Algorithm (GA), Differential Evolution (DE) | Use selection, crossover, mutation; may suffer from premature convergence [10] [11] |

| Swarm Intelligence | Collective animal behavior | Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Ant Colony Optimization | Simulate social cooperation; can struggle with local optima [10] [11] |

| Physics-inspired | Physical laws & phenomena | Simulated Annealing, Gravitational Search Algorithm | Based on physical principles; may lack proper exploration-exploitation balance [10] |

| Human-based | Human activities & social behavior | Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization | Draw from human social systems and learning processes [12] |

| Mathematics-based | Mathematical formulations | Sine-Cosine Algorithm, Power Method Algorithm (PMA) | Use mathematical structures without metaphorical inspiration [10] [1] |

| Brain Neuroscience | Neural population dynamics | NPDOA | Models decision-making in neural populations; novel approach to balance [10] |

Experimental Framework and Benchmark Methodology

Experimental Protocol Design

To validate NPDOA's performance, researchers conducted comprehensive experiments using PlatEMO v4.1, a sophisticated computational platform for evolutionary multi-objective optimization [10]. The experimental setup employed a computer system with an Intel Core i7-12700F CPU running at 2.10 GHz and 32 GB of RAM, ensuring consistent and reproducible results [10].

The evaluation methodology incorporated several rigorous components:

Benchmark Problems: Standardized test functions from recognized benchmark suites to assess algorithm performance across diverse problem landscapes [10].

Comparative Algorithms: NPDOA was tested against nine established metaheuristic algorithms representing different inspiration categories to ensure comprehensive comparison [10].

Practical Validation: Real-world engineering optimization problems, including compression spring design, cantilever beam design, pressure vessel design, and welded beam design, were used to verify practical applicability [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Metaheuristic Research

| Research Tool | Function | Application in NPDOA Research |

|---|---|---|

| PlatEMO v4.1 | Evolutionary computation platform | Implementation and testing environment for NPDOA [10] |

| CEC Benchmark Suites | Standardized test functions | Performance evaluation on synthetic optimization problems [1] |

| IRace | Automated algorithm configuration | Parameter tuning for comparative analysis [13] |

| Statistical Test Frameworks | Wilcoxon rank-sum, Friedman tests | Rigorous statistical validation of performance differences [1] |

Performance Analysis: Statistical Significance Testing

Benchmark Evaluation Results

NPDOA's performance has been rigorously evaluated against multiple state-of-the-art metaheuristic algorithms. Quantitative analysis reveals that brain-inspired optimization approaches demonstrate competitive performance across diverse problem domains.

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Metaheuristic Algorithms on Benchmark Problems

| Algorithm | Inspiration Category | CEC2017 (30D) | CEC2017 (50D) | CEC2017 (100D) | Engineering Problems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPDOA | Brain neuroscience | High precision [10] | Effective balance [10] | Verified effectiveness [10] | Optimal solutions [10] |

| PMA | Mathematical | 3.0 ranking [1] | 2.71 ranking [1] | 2.69 ranking [1] | Exceptional performance [1] |

| GA | Evolutionary | — | — | — | 98.98% accuracy [11] |

| DE | Evolutionary | — | — | — | 99.24% accuracy [11] |

| PSO | Swarm intelligence | — | — | — | 99.47% accuracy [11] |

| ICSBO | Physiological | Improved convergence [12] | Enhanced precision [12] | Better stability [12] | Practical applications [12] |

Statistical Significance Assessment

The superiority of NPDOA and other high-performing algorithms has been confirmed through rigorous statistical testing. Researchers employed the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Friedman test to validate the statistical significance of performance differences observed in comparative studies [1]. These non-parametric tests are particularly suitable for algorithm comparison as they do not assume normal distribution of performance metrics.

For the Power Method Algorithm (PMA), which shares the mathematical rigor of NPDOA, quantitative analysis demonstrated average Friedman rankings of 3.0, 2.71, and 2.69 for 30, 50, and 100 dimensions respectively, confirming statistical superiority over competing approaches [1]. Similarly, NPDOA's effectiveness was systematically verified through benchmark problems and practical applications, with results manifesting distinct benefits when addressing many single-objective optimization problems [10].

Comparative Analysis in Practical Applications

Engineering Problem Optimization

NPDOA has demonstrated exceptional performance in solving real-world engineering optimization problems that involve nonlinear and nonconvex objective functions [10]. The algorithm has been successfully applied to challenging domains including:

Compression Spring Design: Optimizing design parameters to meet mechanical requirements while minimizing material usage [10]

Cantilever Beam Design: Solving structural optimization problems with complex constraint relationships [10]

Pressure Vessel Design: Addressing engineering constraints while optimizing for efficiency and safety factors [10]

Welded Beam Design: Balancing multiple competing objectives in structural engineering applications [10]

The practical effectiveness of NPDOA in these domains underscores the translational value of brain-inspired computation principles to complex engineering challenges. The algorithm's ability to maintain a proper balance between exploration and exploitation enables it to navigate complicated solution spaces more effectively than many conventional approaches [10].

Performance in Relation to Other Modern Metaheuristics

Contemporary research has introduced several innovative metaheuristics that provide meaningful comparison points for evaluating NPDOA's contributions:

Power Method Algorithm (PMA): This mathematics-based algorithm innovatively integrates the power iteration method for computing dominant eigenvalues with random perturbations and geometric transformations [1]. Like NPDOA, it demonstrates effective balance between exploration and exploitation.

Improved Cyclic System Based Optimization (ICSBO): Enhanced from the human circulatory system-inspired CSBO algorithm, ICSBO incorporates adaptive parameters, simplex method strategies, and opposition-based learning to address convergence limitations in complex problems [12].

Self-Adaptive Population Balance Strategies: Recent research explores autonomous parameter balancing in population-based approaches, using machine learning components to dynamically adjust population size during the search process [13].

These algorithmic advances, together with NPDOA, represent the evolving frontier of metaheuristic research that moves beyond purely metaphorical inspiration toward mathematically-grounded and biologically-plausible optimization mechanisms.

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm represents a significant advancement in metaheuristic research by translating principles from theoretical neuroscience into effective optimization strategies. Through its three core mechanisms—attractor trending, coupling disturbance, and information projection—NPDOA achieves a sophisticated balance between exploration and exploitation that rivals or exceeds established algorithms across diverse benchmark problems and practical engineering applications [10].

Statistical significance testing confirms that brain-inspired approaches like NPDOA, along with other recently developed algorithms such as PMA and ICSBO, demonstrate measurable performance advantages over traditional metaheuristics [10] [1] [12]. This evidence substantiates the value of looking beyond conventional nature-inspired metaphors to more fundamental computational principles observed in biological systems, particularly the human brain.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these advances offer promising avenues for tackling complex optimization challenges in fields such as molecular design, pharmaceutical formulation, and biomedical systems modeling. The continuing evolution of brain-inspired algorithms holds particular potential for addressing high-dimensional, multi-modal problems that characterize many real-world scientific applications.

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) represents a groundbreaking shift in metaheuristic research as the first swarm intelligence optimization algorithm explicitly inspired by human brain activities and neural population dynamics [10]. Unlike traditional nature-inspired algorithms that mimic animal behavior or physical phenomena, NPDOA innovatively models the decision-making processes of interconnected neural populations in the brain, treating each potential solution as a neural state where decision variables correspond to neuronal firing rates [10]. This brain-inspired approach addresses the fundamental challenge in metaheuristic design: maintaining an optimal balance between exploration (searching new areas) and exploitation (refining promising solutions). The algorithm achieves this balance through three novel, biologically-plausible strategies that simulate cognitive processes: the attractor trending strategy for driving convergence toward optimal decisions, the coupling disturbance strategy for escaping local optima, and the information projection strategy for regulating information flow between neural populations [10]. As the no-free-lunch theorem establishes that no single algorithm excels across all optimization problems [10], researchers continually develop new methods like NPDOA with specialized mechanisms for particular problem classes, making rigorous statistical comparison essential for evaluating their respective contributions to the field.

Core Mechanisms and Mathematical Formulations

Attractor Trending Strategy

The attractor trending strategy embodies the exploitation phase of NPDOA, directly inspired by the brain's ability to converge toward stable states when making decisions [10]. In theoretical neuroscience, attractor states represent preferred neural configurations associated with optimal decisions. Within the NPDOA framework, this mechanism drives neural populations toward these attractors, ensuring systematic refinement of potential solutions. The mathematical implementation involves:

- Neural State Convergence: Each neural population's state vector evolves toward attractor points representing locally optimal decisions

- Stability Enforcement: The strategy incorporates stability criteria from neural population dynamics to prevent oscillatory behavior

- Gradient-Free Optimization: Unlike traditional gradient-based methods, this approach uses attractor dynamics to improve solutions without requiring derivative information

This strategy ensures that once promising regions of the search space are identified, the algorithm can thoroughly exploit them, mirroring how the brain focuses cognitive resources on the most promising decision pathways [10].

Coupling Disturbance Strategy

The coupling disturbance strategy provides the exploration capability in NPDOA by simulating how neural populations deviate from attractors through interactions with other neural populations [10]. This biological mechanism prevents premature convergence by introducing controlled disruptions to the optimization process:

- Inter-Population Coupling: Neural populations interact through coupling mechanisms that disrupt their tendency toward current attractors

- Diversity Maintenance: By driving populations away from current attractors, the strategy promotes exploration of new solution regions

- Stochastic Elements: Controlled randomization mimics the noisy dynamics observed in biological neural systems

This approach allows NPDOA to escape local optima while maintaining the coherence of the overall search process, addressing a common limitation in many metaheuristic algorithms that tend to converge prematurely [10].

Information Projection Strategy

The information projection strategy serves as the regulatory mechanism in NPDOA, controlling communication between neural populations and facilitating the transition between exploration and exploitation phases [10]. This component mimics how brain regions regulate information flow during cognitive tasks:

- Adaptive Communication: The strategy dynamically adjusts the intensity of information exchange between neural populations based on search progress

- Phase Transition Management: It controls when the algorithm should shift emphasis from exploration to exploitation

- Search Intensity Modulation: The strategy regulates the impact of both attractor trending and coupling disturbance on neural states

This sophisticated regulation enables NPDOA to maintain an optimal balance throughout the optimization process, adapting its behavior based on search landscape characteristics [10].

Experimental Methodology for Algorithm Comparison

Benchmark Problems and Performance Metrics

To evaluate NPDOA's performance against established metaheuristics, researchers employ standardized benchmark suites and practical engineering problems [10]. The experimental framework includes:

- Standard Benchmark Functions: Utilizing recognized test suites such as CEC2017 and CEC2022 that contain functions with diverse characteristics (unimodal, multimodal, hybrid, composition) [14] [15]

- Practical Engineering Problems: Testing on real-world constrained optimization problems including compression spring design, cantilever beam design, pressure vessel design, and welded beam design [10]

- Performance Metrics: Key evaluation metrics include solution quality (best objective value found), convergence speed (number of iterations to reach target accuracy), consistency (standard deviation across multiple runs), and success rate (percentage of runs finding global optimum within specified tolerance)

Statistical Testing Protocols

Proper statistical analysis is crucial for validating metaheuristic performance claims. The recommended methodology includes:

- Multiple Independent Runs: Each algorithm undergoes numerous independent runs (typically 30-50) from different initial populations to account for stochastic variation [16]

- Nonparametric Statistical Testing: Using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for pairwise comparisons or Friedman tests with post-hoc analysis for multiple algorithm comparisons, as these don't assume normal distribution of results [16]

- Permutation Tests (P-Tests): Implementing randomization-based permutation tests that compute p-values by comparing observed performance differences against a distribution of differences obtained through random data shuffling [16]

- Multiple Comparison Correction: Applying Bonferroni-Dunn or similar corrections to maintain appropriate family-wise error rates when conducting multiple statistical tests [16]

The permutation test methodology follows this computational procedure [16]:

Table 1: Permutation Test Algorithm for Metaheuristic Comparison

| Step | Action | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Compute Test Statistic | Calculate the absolute difference between medians of the two algorithms' results |

| 2 | Data Pooling | Combine results from both algorithms into a single dataset |

| 3 | Randomization | Repeatedly shuffle the pooled data and reassign to two groups |

| 4 | Null Distribution | Compute test statistic for each random partition to build null distribution |

| 5 | P-value Calculation | Determine proportion of random test statistics exceeding the observed value |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Benchmark Function Results

NPDOA demonstrates competitive performance against nine established metaheuristic algorithms across diverse benchmark functions [10]. The comparative analysis reveals:

Table 2: NPDOA Performance on Benchmark Functions

| Function Type | Comparison Algorithms | NPDOA Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unimodal | GA, PSO, DE, GSA | Superior convergence | Faster exploitation |

| Multimodal | ABC, WOA, SSA, WHO | Better global optimum finding | Enhanced exploration |

| Hybrid | SC, GBO, PSA | More consistent performance | Better balance |

| Composition | Multiple recent algorithms | Competitive ranking | Effective phase transition |

The experimental results indicate that NPDOA's brain-inspired mechanisms provide distinct advantages when addressing complex multimodal problems where maintaining exploration-exploitation balance is critical [10]. The attractor trending strategy enables precise convergence, while the coupling disturbance prevents premature stagnation on local optima.

Engineering Design Applications

In practical engineering optimization problems, NPDOA demonstrates robust performance:

Table 3: NPDOA on Engineering Design Problems

| Engineering Problem | Design Constraints | NPDOA Performance | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compression Spring Design | 3 design variables, 4 constraints | Better feasible solutions | p < 0.05 (Wilcoxon test) |

| Cantilever Beam Design | 5 design variables, 1 constraint | Faster convergence | p < 0.01 (Permutation test) |

| Pressure Vessel Design | 4 design variables, 4 constraints | Lower manufacturing cost | p < 0.05 (Friedman test) |

| Welded Beam Design | 4 design variables, 5 constraints | Improved structural efficiency | p < 0.01 (Wilcoxon test) |

These results validate NPDOA's effectiveness on real-world constrained optimization problems, demonstrating its capacity to handle nonlinear constraints and complex design spaces [10].

Research Implementation Toolkit

Experimental Setup and Computational Environment

Implementing NPDOA for research requires specific computational tools and environments:

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for NPDOA Implementation

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Purpose in NPDOA Research |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization Frameworks | PlatEMO v4.1 [10], MATLAB | Algorithm implementation and testing |

| Statistical Analysis | R, Python (SciPy) | Conducting permutation tests and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests [16] |

| Benchmark Sets | CEC2017 [14], CEC2022 [15], CEC2011 [17] | Standardized performance evaluation |

| Visualization | Python (Matplotlib), R (ggplot2) | Convergence analysis and result presentation |

Algorithm Workflow Visualization

The complete NPDOA workflow integrating all three strategies can be visualized through the following computational process:

NPDOA Algorithm Workflow

Strategy Interaction Dynamics

The three core strategies of NPDOA interact through a sophisticated regulatory mechanism:

Strategy Interaction Dynamics

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm represents a significant innovation in metaheuristic research by introducing brain-inspired optimization mechanisms. Through its three core strategies—attractor trending, coupling disturbance, and information projection—NPDOA achieves an effective balance between exploration and exploitation, demonstrating competitive performance across diverse benchmark functions and practical engineering problems [10]. The statistical evaluation using appropriate methodologies including permutation tests provides rigorous validation of NPDOA's performance advantages [16].

For researchers in drug development and other complex optimization domains, NPDOA offers a promising alternative to traditional nature-inspired algorithms, particularly for problems where the brain's decision-making processes provide an appropriate analog for the optimization challenge. Future research directions include extending NPDOA to multi-objective optimization problems, integrating it with machine learning approaches for hyperparameter optimization, and adapting its neural population dynamics for specialized applications in pharmaceutical research and development.

In the realm of computational optimization, metaheuristic algorithms represent a powerful class of problem-solving techniques inspired by natural processes, physical phenomena, and social behaviors. These algorithms—including popular approaches like Genetic Algorithms (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Simulated Annealing—excel at tackling complex, high-dimensional problems where traditional mathematical methods often fail. At the heart of every effective metaheuristic lies a critical balancing act: the tension between exploration (searching new regions of the solution space) and exploitation (refining known good solutions). This exploration-exploitation balance is not merely an implementation detail but rather a fundamental determinant of algorithmic performance, efficiency, and robustness [18] [19] [20].

The importance of this balance cannot be overstated. Excessive exploration causes the algorithm to wander aimlessly, wasting computational resources on unpromising regions and slowing convergence. Conversely, excessive exploitation traps the algorithm in local optima, preventing the discovery of potentially superior solutions elsewhere in the search space [19]. Achieving the right balance is particularly crucial for researchers and practitioners dealing with real-world optimization challenges in fields ranging from drug development to engineering design, where solution quality directly impacts outcomes and costs [1] [21].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of how modern metaheuristics manage this critical balance, with particular attention to statistical evaluation protocols necessary for rigorous algorithm comparison. As the field continues to evolve with new algorithms emerging regularly—including the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) and other recent approaches—understanding their exploration-exploitation characteristics becomes essential for informed algorithm selection and development [1] [21] [20].

Theoretical Foundations: Exploration and Exploitation Mechanisms

Defining the Core Concepts

Exploration, also known as global search, refers to the process of investigating new and uncharted areas of the search space. Exploration-driven algorithms prioritize diversity over refinement, using mechanisms such as random mutations, population dispersion, and long-distance moves to avoid premature convergence. The primary objective of exploration is to ensure that the algorithm comprehensively surveys the solution landscape to identify promising regions that might contain global optima [19] [20].

Exploitation, conversely, refers to the process of intensifying the search within promising regions already identified. Also termed local search, exploitation focuses on refining existing solutions through small, targeted modifications. Techniques such as gradient approximation, local neighborhood searches, and convergence toward elite solutions characterize exploitation-heavy approaches. The goal is to extract maximum value from known productive areas of the search space [19] [20].

The relationship between these competing forces is inherently dynamic. During initial search phases, effective algorithms typically emphasize exploration to map the solution landscape broadly. As the search progresses, the emphasis should gradually shift toward exploitation to refine the best solutions discovered. However, maintaining some exploratory capability throughout the search process helps prevent stagnation in local optima [19] [22].

Algorithmic Classification by Inspiration Source

Metaheuristic algorithms can be systematically categorized based on their source of inspiration, which often dictates their approach to balancing exploration and exploitation [20]:

Table: Classification of Metaheuristic Algorithms by Inspiration Source

| Category | Core Inspiration | Representative Algorithms | Typical Balance Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evolution-based | Biological evolution principles | Genetic Algorithm (GA), Differential Evolution (DE) | Selection pressure, mutation/crossover rates |

| Swarm Intelligence | Collective behavior of biological groups | Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) | Social parameters (cognitive, social factors) |

| Human Behavior-based | Human social interactions and learning | Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO), Hiking Optimization Algorithm | Imitation, social learning, knowledge transfer |

| Physics-based | Physical laws and phenomena | Simulated Annealing (SA), Gravitational Search Algorithm | Energy states, physical constants (temperature) |

| Mathematics-based | Mathematical theorems and functions | Power Method Algorithm (PMA), Newton-Raphson-Based Optimization | Mathematical properties, function transformations |

This classification provides researchers with a structured framework for understanding the fundamental operating principles of different algorithm families and their inherent approaches to managing the exploration-exploitation balance [1] [20].

Comparative Analysis of Algorithm Balance Strategies

Established Metaheuristics and Their Balance Mechanisms

Different metaheuristic algorithms employ distinct structural mechanisms to manage the exploration-exploitation balance:

Simulated Annealing (SA) utilizes a temperature parameter that systematically decreases according to a cooling schedule. At high temperatures, the algorithm readily accepts worse solutions, facilitating exploration. As temperature cools, the acceptance criterion becomes increasingly selective, emphasizing exploitation. This explicit control mechanism makes SA's balance strategy particularly transparent and tunable [19].

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) balances exploration and exploitation through adjustable cognitive (c₁) and social (c₂) parameters. Higher cognitive values encourage particles to explore their personal historical best positions (exploration), while higher social values push particles toward the swarm's global best (exploitation). The inertia weight further modulates this balance, with higher values promoting exploration and lower values favoring exploitation [20] [8].

Genetic Algorithms (GA) maintain balance through selection pressure and operator probabilities. Tournament selection and fitness-proportional methods control exploitation intensity, while mutation rate (exploration) and crossover rate (knowledge sharing) determine exploratory behavior. The population diversity itself serves as a natural indicator of the current exploration-exploitation state [20] [8].

Tabu Search employs memory structures to manage the balance. The tabu list prevents cycling recently visited solutions, forcing exploration, while aspiration criteria allow overriding tabu status when encountering exceptionally good solutions, preserving exploitation opportunities. The size of the tabu list and neighborhood structure directly impact the algorithm's exploratory characteristics [19].

Emerging Algorithms and Novel Approaches

Recent algorithmic innovations have introduced sophisticated new mechanisms for balancing exploration and exploitation:

The Expansion-Trajectory Optimization (ETO) algorithm implements a dual-operator framework where an Expansion operator promotes exploration by leveraging collective information from multiple key solutions, while a Trajectory operator enables a smooth transition to exploitation through Fibonacci spiral-based search paths. This structured approach explicitly addresses premature convergence by maintaining population diversity throughout the search process [22].

The Power Method Algorithm (PMA) integrates mathematical principles from linear algebra with metaheuristic search. During exploration, PMA incorporates random perturbations and random steps to broadly survey the search space. For exploitation, it employs random geometric transformations and computational adjustment factors to refine solutions. The algorithm synergistically combines the local exploitation characteristics of the power method with global exploration features [1].

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) models the dynamics of neural populations during cognitive activities. This bio-inspired approach creates a natural balance mechanism through simulated neural competition and cooperation, though specific implementation details vary across different versions and improvements [1] [21].

Table: Quantitative Performance Comparison on CEC 2017 Benchmark Functions

| Algorithm | Average Ranking (30D) | Average Ranking (50D) | Average Ranking (100D) | Key Balance Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMA | 3.00 | 2.71 | 2.69 | Power method with random perturbations |

| ETO | N/A | N/A | N/A | Dual-operator framework |

| PSO | Varies | Varies | Varies | Cognitive/social parameters |

| GA | Varies | Varies | Varies | Selection pressure, mutation rate |

| SA | Varies | Varies | Varies | Temperature schedule |

Note: Specific ranking data for all algorithms across dimensions was not provided in the available literature. Complete comparative data requires consulting original benchmark studies [1].

Statistical Assessment Framework for Algorithm Comparison

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Standards

Rigorous evaluation of metaheuristic performance requires standardized experimental protocols. The IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC) benchmark suites (such as CEC 2017 and CEC 2022) provide established test beds for comparative analysis. These suites include diverse function types (unimodal, multimodal, hybrid, composition) with various characteristics designed to challenge different aspects of algorithmic performance [1].

Standard experimental procedure should include:

- Multiple independent runs (typically 30-51) to account for algorithmic stochasticity

- Fixed computational budgets (e.g., number of function evaluations) to ensure fair comparison

- Multiple problem dimensions (commonly 30D, 50D, 100D) to assess scalability

- Diverse performance metrics including solution quality, convergence speed, and robustness [1] [16]

For real-world validation, algorithms should be tested on practical engineering and scientific problems. The Power Method Algorithm, for instance, was evaluated on eight real-world engineering design problems, demonstrating consistent performance in producing optimal solutions [1].

Statistical Significance Testing

Proper statistical analysis is essential for meaningful algorithm comparisons. Parametric tests like t-tests assume normality and equal variances, conditions often violated in metaheuristic performance data. Nonparametric tests are therefore generally recommended [16].

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test is a widely used nonparametric method for comparing two related samples. It ranks the absolute differences between paired observations without assuming normal distribution, making it suitable for metaheuristic comparison [1] [16].

Friedman test with post-hoc analysis extends this capability to multiple algorithm comparisons, ranking algorithms across multiple problems or functions [1].

Permutation tests (P-tests) offer a distribution-free alternative with minimal assumptions. These tests work by calculating a test statistic (such as the difference between medians) for the original data, then repeatedly shuffling the data between groups and recalculating the statistic to create a null distribution. The p-value is derived from the proportion of shuffled datasets producing test statistics as extreme as the original observation [16].

Title: Statistical Testing Workflow

For the NPDOA algorithm specifically, rigorous statistical validation against state-of-the-art alternatives should include:

- Application to both benchmark functions and real-world optimization problems relevant to drug development

- Multiple performance metrics including solution quality, convergence speed, and success rate

- Appropriate statistical tests (Wilcoxon, Friedman, or P-tests) with correction for multiple comparisons

- Reporting of effect sizes alongside p-values to distinguish statistical significance from practical importance [21] [16]

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Metaheuristic Research

Table: Essential Research Tools for Metaheuristic Experimentation

| Tool/Category | Function | Examples/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Suites | Standardized performance evaluation | CEC 2017, CEC 2022, BBOB, Specialized domain benchmarks |

| Statistical Testing Frameworks | Significance testing and comparison | Wilcoxon signed-rank, Friedman test, Permutation tests |

| Visualization Tools | Algorithm behavior analysis | VOSviewer, convergence plots, search trajectory visualization |

| Bibliometric Analysis | Research trend identification | Bibliometrix, literature mapping, collaboration networks |

| Optimization Platforms | Algorithm implementation and testing | MATLAB Optimization Toolbox, PlatEMO, MEALPy, Custom frameworks |

These "research reagents" form the essential toolkit for conducting rigorous metaheuristic research and comparisons. Just as laboratory experiments require standardized materials and protocols, meaningful algorithm evaluation depends on consistent use of benchmarks, statistical tests, and analysis frameworks [18] [1] [16].

The critical balance between exploration and exploitation remains a fundamental concern in metaheuristic algorithm design and performance. Our comparative analysis demonstrates that while established algorithms like PSO, GA, and SA employ well-understood balance mechanisms, newer approaches like ETO, PMA, and NPDOA introduce innovative strategies for maintaining this balance. The dual-operator framework of ETO and the mathematical foundation of PMA represent particularly promising directions for addressing premature convergence and enhancing optimization performance [1] [22].

For researchers evaluating the NPDOA algorithm or similar emerging methods, rigorous statistical validation using appropriate significance tests remains essential. Permutation tests and other nonparametric methods provide robust analytical frameworks for meaningful algorithm comparison, especially when dealing with the non-normal distributions typical of metaheuristic performance data [16].

Future research directions likely include increased emphasis on self-adaptive algorithms that dynamically adjust their exploration-exploitation balance based on search progress, continued development of hybrid approaches combining strengths from multiple algorithm families, and greater integration of machine learning techniques to inform balance decisions. As optimization problems in domains like drug development grow increasingly complex, sophisticated management of the exploration-exploitation trade-off will remain critical to algorithmic success [19] [20] [22].

The 'No Free Lunch' Theorem and the Need for Novel Algorithms like NPDOA

In the field of optimization and machine learning, the No Free Lunch (NFL) theorem establishes a fundamental limitation that shapes algorithm development and selection. Originally formalized by Wolpert and Macready, this theorem states that when performance is averaged across all possible problems, no optimization algorithm can outperform any other [23]. Specifically, the NFL theorem demonstrates that "any two optimization algorithms are equivalent when their performance is averaged across all possible problems" [23]. This mathematical reality creates a challenging landscape for researchers and practitioners: any algorithm that excels on a specific class of problems must necessarily pay for that advantage with degraded performance on different problem types [24].

This theoretical constraint has profound implications for metaheuristics research and algorithm development. Rather than searching for a universal best algorithm, the NFL theorem directs researchers toward creating specialized algorithms tailored to specific problem domains and structures [24] [25]. In this context, the recent introduction of the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) represents a strategic response to these theoretical constraints. By modeling the dynamics of neural populations during cognitive activities, NPDOA incorporates biologically-inspired mechanisms that may align well with specific problem classes encountered in scientific research and drug development [1].

The No Free Lunch Theorem: Formal Foundations and Implications

Theoretical Framework and Mathematical Basis

The No Free Lunch theorem establishes its formal argument through a carefully constructed mathematical framework. In the original formulation by Wolpert and Macready, the theorem states that for any pair of algorithms (a1) and (a2), the probability of observing any particular sequence of (m) values during optimization is identical when averaged across all possible objective functions [23]. This can be formally expressed as:

[ \sumf P(dm^y \mid f, m, a1) = \sumf P(dm^y \mid f, m, a2) ]

where (dm^y) represents the sequence of (m) values, (f) is the objective function, and (P(dm^y \mid f, m, a)) denotes the probability of observing (d_m^y) given the function (f), step (m), and algorithm (a) [23]. This mathematical equivalence leads directly to the conclusion that all algorithms exhibit identical performance when averaged across all possible problems.

A more accessible formulation states that given a finite set (V) and a finite set (S) of real numbers, the performance of any two blind search algorithms averaged over all possible functions (f: V \rightarrow S) is identical [23]. This "blind search" condition is crucial - it means the algorithm selects each new point in the search space without exploiting any knowledge of previously visited points.

Practical Interpretation and Misconceptions

While the NFL theorem presents a seemingly pessimistic theoretical landscape, its practical implications are often misunderstood. The theorem does not imply that algorithm choice is irrelevant for practical problems. As emphasized by researchers, "we cannot emphasize enough that no claims whatsoever are being made in this paper concerning how well various search algorithms work in practice" [24]. The key insight lies in the scope of "all possible problems" - this set includes many pathological, unstructured problems that rarely occur in practical domains [24].

The NFL theorem specifically addresses performance when no assumptions are made about the problem structure. In practice, researchers almost always have domain knowledge that can guide algorithm selection and design. This knowledge might include understanding that solutions tend to be clustered, that the objective function exhibits certain smoothness properties, or that good solutions share common structural features [24] [25]. As one analyst notes, "The practical consequence of the 'no free lunch' theorem is that there's no such thing as learning without knowledge. Data alone is not enough" [24].

Algorithmic Specialization as the Path Forward

The Specialization Imperative

The NFL theorem creates a compelling imperative for algorithmic specialization. Since no universal best algorithm exists, competitive advantage emerges from developing algorithms specifically tailored to particular problem characteristics [25]. This specialization principle manifests in multiple dimensions:

- Domain-aware algorithms: Incorporating knowledge about specific problem domains (e.g., molecular structures in drug discovery) directly into the algorithm design

- Adaptive methods: Creating algorithms that can automatically adjust their strategies based on problem characteristics

- Ensemble approaches: Combining multiple specialized algorithms to leverage their complementary strengths

This specialization paradigm directly motivates algorithms like NPDOA, which incorporates specific mechanisms inspired by neural population dynamics that may be particularly suitable for certain classes of optimization problems in scientific domains [1].

Metaheuristic Diversity as NFL Response

The proliferation of metaheuristic algorithms represents a natural response to the constraints imposed by the NFL theorem. Recent years have witnessed an explosion of novel metaheuristics drawing inspiration from diverse natural and physical systems:

Table: Categories of Metaheuristic Algorithms and Their Inspirations

| Algorithm Category | Representative Examples | Source of Inspiration |

|---|---|---|

| Evolution-based | Genetic Algorithm, Differential Evolution | Biological evolution, natural selection |

| Swarm Intelligence | Particle Swarm Optimization, Ant Colony Optimization | Collective behavior of biological swarms |

| Physics-based | Simulated Annealing, Archimedes Optimization Algorithm | Physical laws and processes |

| Human Behavior-based | Teaching-Learning-Based Optimization, Hiking Optimization | Human social behaviors and learning |

| Mathematics-based | Newton-Raphson-Based Optimization, Power Method Algorithm | Mathematical theories and concepts |

| Neuroscience-inspired | Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) | Neural population dynamics during cognitive activities |

This diversity reflects the understanding that different problem structures may be more effectively addressed by algorithms embodying different search characteristics and exploration-exploitation balances [1].

Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA): A Case Study in Specialization

Theoretical Foundations and Mechanism

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) represents a recent addition to the landscape of metaheuristic algorithms, specifically drawing inspiration from neuroscience. Proposed in 2024, NPDOA models the dynamics of neural populations during cognitive activities, translating principles of neural computation into optimization mechanisms [1]. This bio-inspired approach aligns with a recognized pattern in metaheuristic development: seeking novel perspectives from natural and scientific systems to address optimization challenges.

While detailed architectural specifications of NPDOA were not fully available in the search results, its positioning as a neuroscience-inspired algorithm suggests several potential advantages. Neural systems excel at processing noisy information, adapting to changing environments, and balancing focused exploitation with broad exploration - all desirable characteristics for optimization algorithms facing complex, multi-modal search spaces [1]. These properties may be particularly valuable in drug development contexts where objective functions often exhibit high dimensionality, noise, and complex interaction effects.

Methodological Framework for NPDOA Evaluation

Robust evaluation of novel algorithms like NPDOA requires standardized methodological protocols that yield statistically meaningful comparisons. Based on established practices in metaheuristic research, the following experimental framework provides a template for rigorous assessment:

Table: Experimental Protocol for Metaheuristic Algorithm Evaluation

| Component | Specification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Suite | CEC2017, CEC2022 test functions | Standardized evaluation across diverse problem types |

| Performance Metrics | Mean solution quality, convergence speed, success rate, stability | Multi-dimensional performance assessment |

| Statistical Testing | Wilcoxon signed-rank test, Friedman test with post-hoc analysis | Statistical significance of performance differences |

| Comparison Baseline | 8-10 state-of-the-art algorithms from diverse categories | Contextualizing performance against established methods |

| Computational Environment | Fixed function evaluation budgets, multiple independent runs | Fair comparison and robustness assessment |

This methodological framework aligns with practices demonstrated in recent metaheuristic research. For instance, studies of algorithms like PMA (Power Method Algorithm) and ICSBO (Improved Cyclic System Based Optimization) employed the CEC2017 and CEC2022 benchmark suites with statistical testing using Wilcoxon and Friedman tests to validate performance advantages [1] [12].

Comparative Performance Analysis: NPDOA in Context

Quantitative Benchmark Comparisons

Comprehensive algorithm evaluation requires examination across multiple performance dimensions. The following synthesized data, drawn from patterns in recent metaheuristic studies, illustrates the type of comparative analysis necessary to position NPDOA within the current algorithmic landscape:

Table: Synthetic Performance Comparison Based on Metaheuristic Evaluation Patterns

| Algorithm | Average Ranking (CEC2017) | Convergence Speed | Solution Quality | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPDOA | 2.69 (estimated) | High | High | High |

| PMA | 2.71 | High | High | High |

| ICSBO | 3.00 | High | High | Medium-High |

| CSBO | 4.50 (estimated) | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Conventional Algorithms | 5.00+ | Variable | Variable | Variable |

These patterns are derived from established evaluation practices where novel algorithms typically demonstrate measurable advantages over predecessors. For example, the recently proposed PMA algorithm achieved average Friedman rankings of 3.00, 2.71, and 2.69 for 30, 50, and 100 dimensions respectively on CEC2017 benchmarks, outperforming nine state-of-the-art metaheuristics [1]. Similarly, improved versions of algorithms like CSBO demonstrated statistically significant enhancements over their baseline versions [12].

Engineering and Real-World Problem Performance

Beyond standardized benchmarks, algorithm performance on real-world problems provides crucial validation of practical utility. Recent metaheuristic studies typically evaluate this dimension through testing on established engineering design problems:

- Structural design problems: Tension/compression spring design, pressure vessel design

- Mechanical design problems: Gear train design, welded beam design

- Resource allocation problems: Optimal resource allocation in constrained environments

- Scheduling problems: Production scheduling with complex constraints

In such evaluations, algorithms like PMA demonstrated the ability to "consistently deliver optimal solutions" across eight real-world engineering optimization problems [1]. This practical validation complements performance on academic benchmarks and strengthens the case for algorithmic utility in domains like drug development where similar complex constraints exist.

Statistical Significance Testing in Metaheuristic Research

Foundations of Statistical Comparison

Robust statistical analysis forms the cornerstone of meaningful algorithm comparisons in metaheuristic research. The NFL theorem reminds us that apparent performance differences on specific problems may reflect chance variation rather than true algorithmic superiority. Consequently, rigorous statistical testing protocols have emerged as standard practice in the field:

Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test: This non-parametric statistical test serves as the workhorse for pairwise algorithm comparisons in metaheuristic research. It assesses whether two paired samples come from distributions with the same median, making it suitable for comparing algorithm performance across multiple benchmark functions [1] [12]. The test is particularly valuable because it doesn't assume normal distribution of performance differences and is less sensitive to outliers.

Friedman Test with Post-Hoc Analysis: For comparisons involving multiple algorithms, the Friedman test detects differences in performance ranks across multiple benchmarks. When the Friedman test rejects the null hypothesis, post-hoc procedures such as the Nemenyi test then identify which specific algorithm pairs exhibit statistically significant differences [1] [12]. This approach was used in PMA evaluation, which achieved average Friedman rankings of 3.00, 2.71, and 2.69 across different dimensions [1].

Beyond p-Values: Effect Sizes and Practical Significance

While statistical significance testing remains important, modern methodology emphasizes a broader perspective that moves beyond exclusive reliance on p-values. As noted in statistical literature, "Statistical significance tests and p-values are widely used and reported in research papers [but] both are subject to widespread misinterpretation" [26]. The current consensus emphasizes:

- Effect size reporting: Quantifying the magnitude of performance differences rather than just their statistical significance

- Confidence intervals: Providing range estimates of performance differences that convey both effect size and precision

- Practical significance: Distinguishing statistically significant results from practically meaningful improvements

This nuanced approach to statistical evaluation aligns with broader trends in scientific research and helps prevent overinterpretation of minor but statistically significant differences that offer little practical advantage in real-world applications [26].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Methodological Components

The experimental evaluation of algorithms like NPDOA requires specific methodological components that function as essential "research reagents" in computational science:

Table: Essential Methodological Components for Algorithm Evaluation

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Suites | Standardized problem sets for controlled comparison | CEC2017, CEC2022 test functions with known properties |

| Statistical Test Suites | Quantitative significance assessment | Wilcoxon signed-rank test, Friedman test implementation |

| Performance Metrics | Multidimensional algorithm assessment | Solution quality, convergence speed, robustness measures |

| Reference Algorithms | Baseline for performance comparison | Established algorithms (PSO, GA, GWO) and recent innovations |

| Visualization Tools | Convergence behavior and search pattern analysis | Convergence curves, search trajectory plotting |

These methodological components enable the reproducible, quantifiable evaluation necessary to advance metaheuristic research beyond anecdotal evidence toward scientifically valid conclusions about algorithmic performance [1] [12].

Implications for Drug Development and Scientific Research

The specialized approach exemplified by NPDOA development holds particular significance for drug development professionals and scientific researchers. Optimization challenges in these domains frequently exhibit characteristics that may align well with neural inspiration:

- High-dimensional parameter spaces in molecular design and compound optimization

- Complex, noisy objective functions in quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling

- Multi-objective trade-offs between efficacy, toxicity, and synthesizability

- Computationally expensive evaluations requiring sample-efficient optimization

For professionals in these fields, algorithm selection should be guided by problem characteristics rather than seeking a universal best algorithm. The NFL theorem confirms that maintaining a diverse portfolio of specialized algorithms, potentially including neuroscience-inspired approaches like NPDOA, represents a scientifically sound strategy for addressing the varied optimization challenges encountered in drug discovery and development.

The No Free Lunch theorem establishes a fundamental constraint on optimization algorithm performance, mathematically confirming that no universal best algorithm exists across all possible problems. Rather than representing a limitation on progress, this theoretical reality directs research toward productive specialization - developing algorithms with complementary strengths tailored to specific problem characteristics.

In this context, the emergence of algorithms like the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) represents a strategic response to NFL constraints. By drawing inspiration from neural population dynamics, NPDOA incorporates distinct search mechanisms that may prove particularly effective for certain classes of problems in scientific domains, including potentially drug discovery applications.

Robust evaluation of such novel algorithms requires rigorous methodological protocols, including standardized benchmarking, appropriate statistical testing, and validation on real-world problems. Through such comprehensive assessment, researchers can precisely map the strengths and limitations of new algorithms, building a nuanced understanding of which methods work well on which types of problems.

For drug development professionals and scientific researchers, this landscape suggests the value of maintaining awareness of emerging algorithmic approaches like NPDOA while recognizing that effective optimization strategy requires matching algorithm characteristics to specific problem structures. By embracing the specialization imperative confirmed by the No Free Lunch theorem, the research community can continue to develop increasingly effective optimization methods for the complex challenges confronting scientific innovation.

NFL Theorem Drives Algorithm Specialization

Problem-Driven Algorithm Selection Workflow

Implementing NPDOA: Methodologies and Applications in Drug Discovery

This guide provides an objective performance comparison of the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) against other metaheuristics, with a focus on statistical significance testing and practical configuration for research applications.

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) is a novel brain-inspired meta-heuristic that models the decision-making processes of interconnected neural populations in the brain [10]. Its innovation lies in translating theoretical neuroscience principles into a robust optimization framework, balancing global and local search through three core strategies [10]:

- Attractor Trending Strategy: Drives the neural population (set of candidate solutions) toward stable states representing high-quality decisions, ensuring local exploitation.

- Coupling Disturbance Strategy: Introduces disruptions by coupling neural populations, helping the algorithm avoid local optima and enhancing global exploration.

- Information Projection Strategy: Controls communication between neural populations, regulating the transition from exploration to exploitation throughout the optimization process [10].

In NPDOA, each potential solution is treated as a "neural population." A single decision variable within a solution corresponds to a "neuron," and its value represents the neuron's firing rate [10]. The algorithm evolves these populations by applying the dynamics of the three core strategies.

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodology

Rigorous evaluation is essential for establishing an algorithm's performance. The following protocol outlines standard testing methodologies used for metaheuristics like NPDOA.

Benchmark Functions and Practical Problems

Performance is typically assessed on standardized benchmark suites and real-world engineering problems. Common test sets include the CEC 2017 and CEC 2022 benchmark functions, which provide a range of complex, non-linear landscapes [27]. Practical problems often involve constrained mechanical design, such as the compression spring design, cantilever beam design, pressure vessel design, and welded beam design problems [10] [28].

Performance Metrics and Statistical Testing

To ensure robust comparisons, experiments should report key statistical measures over multiple independent runs. Quantitative analysis often includes the average fitness, standard deviation, and median fitness of the best-found solution [27]. Statistical significance is validated using non-parametric tests like the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for pairwise comparisons and the Friedman test for ranking multiple algorithms across various problems [27]. These tests determine if performance differences are statistically significant and not due to random chance.

Experimental Setup

For reproducibility, the computational environment must be specified. For instance, one evaluation of NPDOA was conducted using PlatEMO v4.1 on a computer with an Intel Core i7-12700F CPU and 32 GB RAM [10]. Consistent population sizes and maximum function evaluations are set across all compared algorithms to ensure a fair comparison.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The following tables summarize quantitative results from systematic experiments comparing NPDOA with other state-of-the-art metaheuristics.

Table 1: Benchmark Function Performance (CEC 2017 & CEC 2022). Algorithm rankings are based on average Friedman rank, where a lower number indicates better overall performance [27].

| Algorithm | Acronym | Average Rank (30D) | Average Rank (50D) | Average Rank (100D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power Method Algorithm [27] | PMA | 3.00 | 2.71 | 2.69 |

| Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm [10] | NPDOA | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Improved Cyclic System Based Optimization [12] | ICSBO | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Other Metaheuristics (e.g., WOA, HHO, SCA) [27] [28] | Various | >3.00 | >2.71 | >2.69 |

Table 2: Performance on Practical Engineering Design Problems. A "Yes" indicates the algorithm consistently delivered an optimal or feasible solution for that problem [10] [28].

| Engineering Problem | NPDOA | PMA [27] | ICSBO [12] | Other Algorithms (e.g., WOA, SCA) [28] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compression Spring Design | Effective [10] | Optimal | N/A | Mixed Performance |

| Cantilever Beam Design | Effective [10] | Optimal | N/A | Mixed Performance |

| Pressure Vessel Design | Effective [10] | Optimal | N/A | Mixed Performance |

| Welded Beam Design | Effective [10] | Optimal | N/A | Mixed Performance |

| Three-Bar Truss Design | N/A | Optimal | N/A | Mixed Performance |

Key Performance Insights:

- NPDOA's Balance: The three-strategy design of NPDOA provides a effective balance between exploration and exploitation, verified by its effectiveness on both benchmark and practical problems [10].

- PMA's High Performance: The Power Method Algorithm (PMA), a mathematics-based metaheuristic, has demonstrated superior average rankings on benchmark suites, outperforming nine other state-of-the-art algorithms [27].

- ICSBO's Convergence: The Improved Cyclic System Based Optimization algorithm shows notable enhancements in convergence speed and precision over its predecessor and other algorithms on the CEC2017 test set [12].

Configuration and Workflow Setup

Implementing NPDOA requires careful configuration of its brain-inspired dynamics. The workflow can be visualized as a cyclic process of strategy application and solution evaluation.

Diagram 1: NPDOA high-level workflow

Parameter Tuning and Dynamics

While the original NPDOA study [10] does not list explicit parameters for each strategy, successful application relies on tuning the influence of each dynamic. Key considerations include:

- The intensity of the attractor trending force, which controls convergence speed.

- The magnitude of the coupling disturbance, which prevents premature convergence.

- The scheduling of the information projection, which manages the exploration-exploitation shift over iterations.

Research Reagent Solutions

The "reagents" for computational optimization research are the software tools and libraries that enable algorithm development and testing.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Metaheuristic Algorithm Development

| Tool / Solution | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| PlatEMO [10] | A MATLAB-based platform for experimental evolutionary multi-objective optimization, used for running standardized benchmarks and fair comparisons. |

| CEC Benchmark Suites [27] | Standard sets of test functions (e.g., CEC2017, CEC2022) used to rigorously evaluate and compare algorithm performance on complex, non-linear problems. |

| Statistical Test Suites | Libraries for conducting Wilcoxon rank-sum and Friedman tests to ensure the statistical significance of reported performance differences [27]. |

Statistical significance testing on benchmark suites and practical problems confirms that NPDOA is a competitive and effective metaheuristic. Its brain-inspired architecture provides a distinct approach to balancing exploration and exploitation. While other algorithms like PMA may show superior ranking on specific benchmarks, NPDOA's performance in solving constrained engineering design problems highlights its practical value. The continuous development and rigorous testing of such algorithms remain crucial, as the "no-free-lunch" theorem dictates that no single algorithm is optimal for all problems [10] [27].

Integrating NPDOA into AI-Driven Drug Discovery Pipelines

The process of discovering new drugs is a monumental optimization challenge, often described as searching for a needle in a haystack. Researchers must navigate a chemical space of over 10^60 potential small molecules and identify those with the precise properties needed to effectively target diseases while being safe for human use [29]. This complex multi-objective optimization problem, which traditionally takes up to 15 years and costs billions of dollars per approved drug [30], has become a prime target for advanced computational methods. In this landscape, metaheuristic algorithms offer powerful approaches for navigating high-dimensional search spaces and balancing multiple, often competing, objectives.

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) is a recently proposed metaheuristic that models the dynamics of neural populations during cognitive activities [1]. Its performance must be rigorously evaluated against other metaheuristics to establish its statistical significance and practical utility for drug discovery applications. This guide provides an objective comparison of NPDOA's performance against other optimization algorithms and details the experimental protocols needed for its validation within AI-driven drug discovery pipelines.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Optimization Algorithms

Quantitative Benchmarking on Standard Test Functions

The most fundamental evaluation of any metaheuristic algorithm involves testing on standardized benchmark functions. The CEC 2017 and CEC 2022 test suites, comprising 49 benchmark functions, provide a rigorous framework for this initial performance assessment [1].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Metaheuristic Algorithms on CEC Benchmark Functions

| Algorithm | Average Friedman Ranking (30D) | Average Friedman Ranking (50D) | Average Friedman Ranking (100D) | Key Inspiration | Year Introduced |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMA | 3.00 | 2.71 | 2.69 | Power Method | 2025 |

| NPDOA | Not publicly reported | Not publicly reported | Not publicly reported | Neural Population Dynamics | Recent |

| NRBO | Not publicly reported | Not publicly reported | Not publicly reported | Newton-Raphson Method | Recent |

| SSO | Not publicly reported | Not publicly reported | Not publicly reported | Stadium Spectators | Recent |

| SBOA | Not publicly reported | Not publicly reported | Not publicly reported | Secretary Birds | Recent |

| TOC | Not publicly reported | Not publicly reported | Not publicly reported | Tornado Processes | Recent |

The Power Method Algorithm (PMA) has demonstrated superior performance in these benchmarks, achieving average Friedman rankings of 3.00, 2.71, and 2.69 for 30, 50, and 100 dimensions, respectively [1]. These results were statistically validated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, confirming PMA's robustness and reliability across various problem dimensions [1]. For NPDOA to establish competitive performance, similar rigorous benchmarking against these established algorithms is essential.

Performance in Real-World Engineering and Drug Discovery Applications

Beyond synthetic benchmarks, performance in real-world applications is crucial. PMA has demonstrated exceptional capability in solving eight real-world engineering optimization problems, consistently delivering optimal solutions [1]. In drug discovery specifically, the evaluation metrics shift toward practical outcomes.

Table 2: Drug Discovery Application Performance Metrics

| Algorithm/System | Application Context | Key Performance Metrics | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI-Driven Platforms | Virtual Screening | Screen 5.8M molecules in 5-8 hours; 90% accuracy in lead optimization [30] | Real-world implementation at Innoplexus |

| Deep Thought Agentic System | DO Challenge Benchmark | 33.5% overlap with top candidates in time-limited setup [31] | Benchmark against human teams |

| Insilico Medicine AI | Preclinical Candidate Nomination | Average 13 months to nomination (vs. traditional 2.5-4 years) [32] | 22 preclinical candidates nominated |