Scalability Assessment of Neural Population Dynamics Optimization: From Algorithmic Innovation to Clinical Translation in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive assessment of the scalability of neural population dynamics optimization methods, a class of brain-inspired algorithms increasingly applied to complex problems in biomedical research and drug...

Scalability Assessment of Neural Population Dynamics Optimization: From Algorithmic Innovation to Clinical Translation in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive assessment of the scalability of neural population dynamics optimization methods, a class of brain-inspired algorithms increasingly applied to complex problems in biomedical research and drug development. We explore the foundational principles of these algorithms, inspired by the coordinated activity of neural populations in the brain, and detail their methodological implementation for high-dimensional optimization tasks. The scope includes a critical analysis of computational bottlenecks, strategies for enhancing performance on large-scale datasets, and rigorous validation through comparative benchmarks against established meta-heuristic and machine learning approaches. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current capabilities and future directions, highlighting the transformative potential of these methods in accelerating target identification, lead optimization, and clinical trial design.

The Rise of Neural Population Dynamics: Core Principles and Scalability Drivers in Computational Biology

Neural population dynamics optimization represents a foundational framework for understanding how collectives of neurons collaboratively encode, process, and adapt to sensory information. This paradigm shifts focus from single-neuron characterization to the computational principles governing coordinated network activity, revealing how biological systems achieve efficient information transmission across diverse sensory environments. Research in this domain bridges microscopic neuronal mechanisms and macroscopic brain-wide computations, providing a critical lens through which to examine sensory processing, perceptual decision-making, and adaptive behavior. The optimization lens further provides a powerful tool for translating biological principles into algorithmic designs for artificial intelligence and medical applications, particularly in drug discovery and neurological therapeutics. This guide systematically compares the performance and scalability of contemporary approaches to studying and leveraging neural population dynamics, providing researchers with actionable insights for method selection and implementation.

Foundational Neuroscience of Population Coding

Contrast Gain Control as a Canonical Optimization Mechanism

At the core of neural population optimization is contrast gain control, a form of adaptive sensory processing where neuronal populations adjust their response gain according to the statistical structure of the environment. In primary visual cortex (V1), for instance, population responses to a fixed stimulus can be described by a vector function r(gₑc), where the gain factor gₑ decreases monotonically with the mean contrast of the visual environment [1]. This reparameterization represents an elegant geometric solution to the dynamic range problem: rather than each stimulus being mapped to a unique response pattern that changes with environment, a visual stimulus generates a single, invariant contrast-response curve across environments [1]. Downstream areas can thus identify stimuli simply by determining whether population responses lie on a given stimulus curve, dramatically simplifying decoding complexity.

The functional goal of such adaptation is to align the region of maximal neuronal sensitivity with the geometric mean of contrasts observed in recent stimulus history, thereby maximizing information transmission efficiency [1]. This optimization principle operates similarly in the auditory system, where cortical contrast adaptation dynamics predict perception of signals in noise [2]. Normative modeling reveals that these adaptation dynamics are asymmetric: target detectability decreases rapidly after switching to high-contrast environments but improves slowly after switching to low-contrast conditions [2]. This asymmetry reflects an efficient coding strategy where neural systems prioritize different temporal windows for statistical estimation depending on environmental context.

Cross-Population Dynamics and Interactive Processing

Beyond adaptation within single populations, the brain optimizes information flow through coordinated dynamics across neural populations. Cross-population interactions face a fundamental challenge: shared dynamics between regions can be masked or confounded by dominant within-population dynamics [3]. To address this, the Cross-population Prioritized Linear Dynamical Modeling (CroP-LDM) framework explicitly prioritizes learning cross-population dynamics over within-population dynamics by setting the learning objective to accurately predict target population activity from source population activity [3]. This prioritized approach enables more accurate identification of interaction pathways between brain regions, such as quantifying that premotor cortex (PMd) better explains primary motor cortex (M1) activity than vice versa, consistent with known neuroanatomy [3].

Table 1: Key Optimization Principles in Neural Population Coding

| Optimization Principle | Neural Implementation | Functional Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Contrast Gain Control | Reparameterization of population response curves r(gₑc) [1] | Maintains coding fidelity across varying environmental statistics |

| Efficient Dynamic Adaptation | Asymmetric gain adjustment timescales [2] | Maximizes information transmission while minimizing metabolic cost |

| Cross-Population Prioritization | Separate learning of shared vs. within-population dynamics [3] | Reveals true interactive signals masked by dominant local dynamics |

| Invariant Stimulus Representation | Stimulus-specific response curves with common origin [1] | Simplifies downstream decoding regardless of adaptation state |

Computational Frameworks for Modeling Neural Population Dynamics

Scalable Neural Forecasting Architectures

Accurate prediction of future neural states represents a critical benchmark for models of population dynamics. POCO (Population-Conditioned Forecaster) introduces a unified architecture that combines a lightweight univariate forecaster for individual neuron dynamics with a population-level encoder that captures brain-wide influences [4] [5]. This hybrid approach uses Feature-wise Linear Modulation (FiLM) to condition individual neuron predictions on global population state, enabling accurate cellular-resolution forecasting up to 15 seconds into the future across multiple species (zebrafish, mice, C. elegans) and recording sessions [4]. Notably, POCO learns biologically meaningful embeddings without anatomical labels, with unit embeddings spontaneously clustering by brain region [4] [5].

For capturing evolutionary dynamics from population-level snapshot data, the iJKOnet framework combines the Jordan-Kinderlehrer-Otto (JKO) scheme from optimal transport theory with inverse optimization techniques [6]. This approach is particularly valuable when individual particle trajectories are unavailable, such as in single-cell genomics where destructive sampling only provides isolated population profiles at discrete time points [6]. By framing dynamics recovery as an inverse optimization problem, iJKOnet can reconstruct the underlying energy functionals governing population evolution without restrictive architectural constraints like input-convex neural networks [6].

Comparative Analysis of Computational Approaches

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Neural Population Dynamics Models

| Model | Primary Application | Key Innovation | Scalability Advantages | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POCO [4] [5] | Cross-session neural forecasting | Population-conditioned univariate forecasting | Adapts to new recordings with minimal fine-tuning; handles variable neuron counts across sessions | State-of-the-art accuracy on 5 calcium imaging datasets across zebrafish, mice, C. elegans |

| CroP-LDM [3] | Cross-region interaction mapping | Prioritized learning of cross-population dynamics | Lower-dimensional latent states than alternatives; causal and non-causal inference options | Multi-regional motor cortical recordings in NHPs; identifies dominant PMd→M1 pathway |

| iJKOnet [6] | Population dynamics from snapshots | JKO scheme + inverse optimization | End-to-end adversarial training without architectural constraints | Synthetic datasets and single-cell genomics; outperforms prior JKO-based methods |

| GC-GLM [2] | Contrast gain dynamics | Dynamic gain control estimation | Captures adaptation dynamics after environmental transitions | Auditory cortex recordings in mice; predicts behavioral performance variability |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Neural Population Dynamics

Protocol 1: Measuring Contrast Gain Control in Visual Cortex

Objective: Quantify how neural populations in primary visual cortex adapt their contrast-response functions across different statistical environments.

Materials and Methods:

- Subjects: Genetically engineered mice (e.g., TRE-GCaMP6s x CaMKII-tTA crosses) for calcium imaging [1]

- Surgical Preparation: Implant cranial windows over V1 for two-photon imaging through intact dura [1]

- Visual Stimulation: Present dynamic random chords with different contrast distributions using a calibrated display system [1]

- Data Acquisition: Use two-photon microscopy at 15.6 Hz frame rate with 920 nm excitation; process images with suite2p pipeline and custom deconvolution algorithms [1]

- Analysis: Model population responses as r(gₑc) and fit gain parameter gₑ for each environment; test reparameterization invariance [1]

Protocol 2: Behavioral Assessment of Contrast Adaptation

Objective: Establish causal relationship between cortical contrast adaptation dynamics and perceptual performance.

Materials and Methods:

- Behavioral Task: Train mice in GO/NO-GO detection task with targets embedded in switching low/high contrast backgrounds [2]

- Cortical Manipulation: Use optogenetics or pharmacological inhibition to establish necessity of auditory cortex for detection in noise [2]

- Neural Recording: Simultaneously record cortical activity using silicon probes or two-photon imaging during behavior [2]

- Modeling: Fit Generalized Linear Models with dynamic gain control (GC-GLM) to estimate moment-to-moment changes in neuronal gain [2]

- Correlation Analysis: Relate trial-by-trial variability in estimated neuronal gain to behavioral performance metrics [2]

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Neural Population Dynamics Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| GCaMP6s Transgenic Mice | Genetically encoded calcium indicator for neural activity imaging | TRE-GCaMP6s x CaMKII-tTA crosses for cell-type specific expression [1] |

| Two-Photon Microscopy Systems | High-resolution calcium imaging through cranial windows | Resonant two-photon microscope (Neurolabware) with 920 nm excitation [1] |

| Dynamic Random Chord Stimuli | Precisely controlled visual stimuli with parameterized contrast statistics | Samsung CHG90 monitor calibrated with spectro-radiometer [1] |

| Suite2p Pipeline | Automated image registration, cell segmentation, and signal extraction | Standardized processing of calcium imaging data [1] |

| POCO Framework | Cross-session neural forecasting architecture | MLP forecaster with population encoder using FiLM conditioning [4] [5] |

| CroP-LDM Algorithm | Prioritized modeling of cross-population dynamics | Linear dynamical systems with focused learning objective [3] |

| JKO Scheme Implementation | Modeling population dynamics from distribution snapshots | iJKOnet for inverse optimization of energy functionals [6] |

Integration with Drug Discovery and Development Applications

The optimization principles governing neural population dynamics have significant implications for drug development, particularly in neurological and psychiatric disorders. AI-assisted approaches that incorporate population dynamics models can accelerate multiple phases of the pharmaceutical pipeline [7]. For instance, population-based modeling of healthy and disease electrophysiological phenotypes enables reverse phenotypic screening for ideal therapeutic perturbations [8]. In Huntington's disease models, such approaches have identified coherent sets of ion channel modulations that can restore wild-type excitability profiles from diseased neuronal populations [8].

Similarly, OptiNet-CKD demonstrates how population optimization algorithms (POA) can enhance deep neural networks for medical prediction tasks, achieving 100% accuracy in chronic kidney disease prediction by maintaining population diversity to explore solution spaces more effectively and avoid local minima [9]. This same principle of population-level optimization mirrors how neural populations maintain diverse response properties to efficiently encode sensory information [1] [10].

The study of neural population dynamics optimization reveals conserved principles operating across biological and computational domains. From contrast gain control in sensory systems to cross-population prioritized learning and scalable forecasting architectures, the consistent theme is efficient information processing through coordinated population-level coordination. The comparative analysis presented here demonstrates that modern computational frameworks like POCO, CroP-LDM, and iJKOnet achieve remarkable performance by embodying these biological principles while leveraging mathematical optimization theory. For researchers and drug development professionals, these approaches offer powerful tools for understanding neural computation, disease pathophysiology, and therapeutic mechanism of action. As these methods continue to evolve, they promise to further blur the boundaries between brain neuroscience and algorithmic design, enabling more biologically-inspired AI systems and more computationally-precise neuroscience.

This guide provides an objective performance comparison of the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA), a novel brain-inspired meta-heuristic, against other established optimization methods. We focus on its three core strategies—Attractor Trending, Coupling Disturbance, and Information Projection—and evaluate its efficacy using standard benchmark and practical engineering problems [11].

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) is a swarm intelligence meta-heuristic inspired by the information processing and decision-making capabilities of the human brain. In NPDOA, a potential solution to an optimization problem is treated as the neural state of a population of neurons. Each decision variable in the solution represents a neuron, and its value corresponds to that neuron's firing rate [11]. The algorithm operates by simulating the dynamics of multiple interconnected neural populations through three core strategies:

- Attractor Trending Strategy: This strategy is responsible for the algorithm's exploitation capability. It drives the neural states of populations towards stable configurations, or "attractors," which represent high-quality decisions or optimal solutions within the search space. This ensures the algorithm converges toward promising areas [11].

- Coupling Disturbance Strategy: This strategy enhances the algorithm's exploration ability. It introduces deviations in the neural populations by coupling them with other populations, pulling them away from their current attractors. This mechanism helps prevent premature convergence by exploring new regions of the search space [11].

- Information Projection Strategy: This strategy governs the transition between exploration and exploitation. It controls the communication and information flow between different neural populations, thereby regulating the influence of the Attractor Trending and Coupling Disturbance strategies on the overall neural state evolution [11].

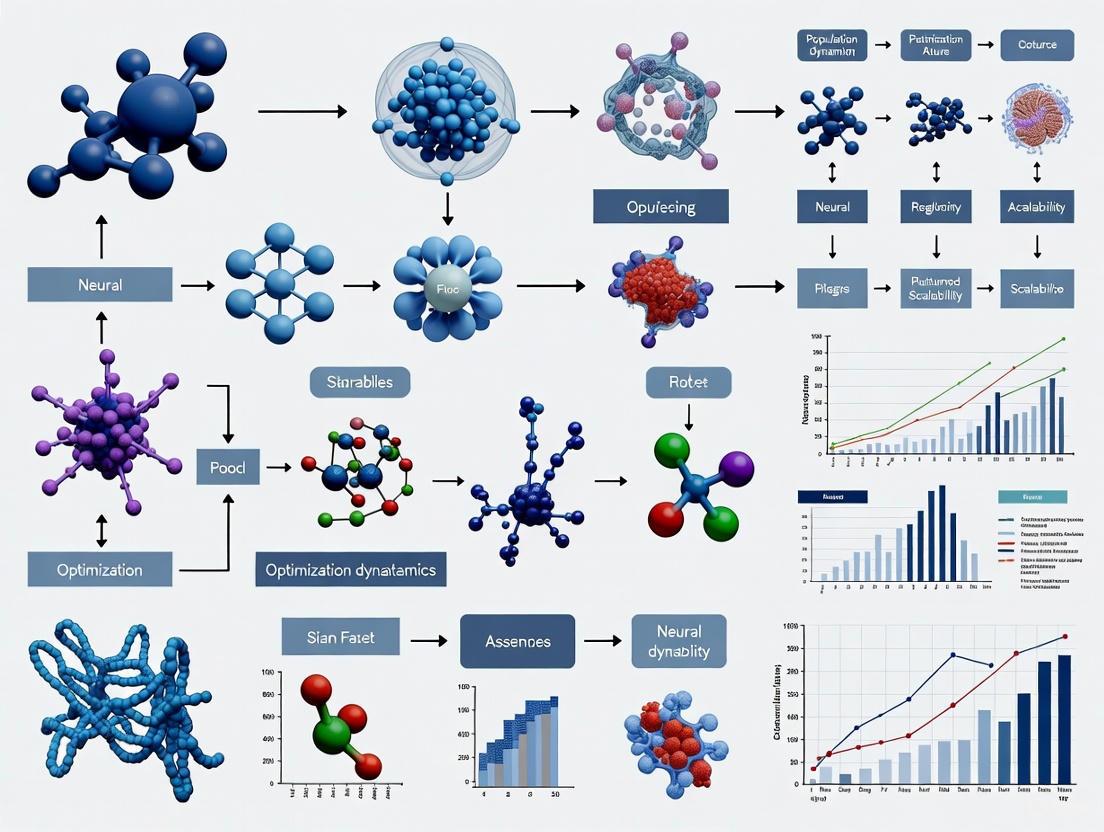

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow between these three core strategies.

Experimental Protocols and Performance Comparison

To validate its performance, NPDOA was systematically compared against nine other meta-heuristic algorithms on a suite of benchmark problems and practical engineering design challenges [11].

Detailed Experimental Methodology

The experimental protocol was designed to ensure a fair and rigorous comparison:

- Algorithm Implementation: The proposed NPDOA and all nine competitor algorithms were implemented within the PlatEMO v4.1 framework, a standard platform for evolutionary multi-objective optimization [11].

- Hardware and Computational Environment: All experiments were executed on a computer system equipped with an Intel Core i7-12700F CPU (2.10 GHz) and 32 GB of RAM to ensure consistent runtime performance [11].

- Benchmarking Suite: The algorithms were tested on widely recognized single-objective benchmark functions. These functions are designed to probe different aspects of algorithmic performance, including the ability to avoid local optima (unimodal and multimodal functions) and navigate complex search spaces (composition functions).

- Practical Problem Application: The evaluation was extended to real-world engineering optimization problems, such as the compression spring design, cantilever beam design, pressure vessel design, and welded beam design problems [11]. These problems often involve nonlinear and nonconvex objective functions with constraints.

- Performance Metrics: The primary metric for comparison was the solution quality—the objective function value achieved by each algorithm upon convergence. This directly measures the algorithm's effectiveness in finding the optimal or near-optimal solution.

Quantitative Performance Comparison on Benchmarks

The following table summarizes the comparative performance of NPDOA against other algorithms on standard benchmark functions.

| Algorithm | Inspiration Source | Exploration/Exploitation Balance | Key Mechanism | Reported Performance vs. NPDOA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPDOA | Brain Neural Dynamics | Balanced via Information Projection | Attractor Trending & Coupling Disturbance | Benchmark Leader |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Natural Evolution | Selection, Crossover, Mutation | Survival of the Fittest | Prone to Premature Convergence [11] |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | Bird Flocking | Local & Global Best Particles | Social Cooperation | Lower Convergence, Local Optima [11] |

| Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) | Humpback Whale Hunting | Encircling & Bubble-net Attack | Random Walk Exploration | Higher Computational Complexity [11] |

| Sine-Cosine Algorithm (SCA) | Mathematical Formulations | Sine and Cosine Functions | Oscillatory Movement | Lacks Trade-off, Local Optima [11] |

Performance on Practical Engineering Problems

NPDOA was also evaluated on constrained real-world engineering problems. The table below outlines the problems and the general advantage of NPDOA.

| Practical Problem | Description | Key Constraints | NPDOA's Performance Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compression Spring Design [11] | Minimize spring weight | Shear stress, surge frequency, deflection | Effective handling of nonlinear constraints |

| Cantilever Beam Design [11] | Minimize beam weight | Bending stress | Efficient search in complex design space |

| Pressure Vessel Design [11] | Minimize total cost | Material, forming, welding costs | Superior solution quality |

| Welded Beam Design [11] | Minimize fabrication cost | Shear stress, bending stress, deflection | Balanced exploration/exploitation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following "research reagents"—computational tools and models—are essential for working in this field.

| Tool/Model Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| PlatEMO v4.1 [11] | Software Platform | Framework for implementing and testing evolutionary algorithms. |

| Functional Connectome-based Hopfield Network (fcHNN) [12] [13] | Computational Model | Models large-scale brain dynamics as an attractor network for simulation. |

| Cross-Attractor Coordination Model [14] [15] | Analytical Framework | Predicts functional connectivity by analyzing correlations across all attractor states. |

| POCO (Population-Conditioned Forecaster) [4] [5] [16] | Forecasting Architecture | Predicts future neural activity by combining single-neuron and population-level dynamics. |

Workflow for Validating Neural Dynamics in Optimization

The diagram below outlines a generalized experimental workflow for validating brain-inspired optimization algorithms, integrating both computational and empirical approaches discussed in the research.

Experimental results from benchmark and practical problems confirm that NPDOA offers distinct advantages in addressing complex single-objective optimization challenges [11]. Its brain-inspired architecture, governed by the three core strategies, provides a robust mechanism for maintaining a critical balance between exploring new solutions and refining existing ones. This makes NPDOA a compelling choice for researchers and engineers tackling nonlinear, nonconvex optimization problems in both scientific and industrial domains.

The escalating dimensionality of data in modern drug discovery presents a critical scalability challenge. Traditional computational methods are often overwhelmed by the complexity of biological systems, necessitating advanced artificial intelligence (AI) platforms that can efficiently navigate vast search spaces. This guide objectively compares the performance and scalability of leading AI-driven drug discovery platforms, framing the analysis within methodologies pioneered in neural population dynamics research, which specialize in extracting low-dimensional, interpretable structures from high-dimensional data [17] [18].

Experimental Protocols & Workflow Diagrams

The evaluation of computational platforms is based on their published performance in tackling high-dimensional problems, from target identification to molecule generation. The following workflows and protocols are central to this assessment.

Workflow for High-Dimensional Drug Target Identification

This diagram illustrates the integrated stacked autoencoder and optimization framework for classifying drugs and identifying druggable targets, a method demonstrating high accuracy and low computational overhead [19].

Experimental Protocol for optSAE + HSAPSO Framework [19]:

- Data Curation: Assemble datasets from validated pharmacological sources (e.g., DrugBank, Swiss-Prot). Preprocess data to handle missing values and normalize features.

- Feature Extraction with Stacked Autoencoder (SAE): Train a deep stacked autoencoder network in an unsupervised manner to learn compressed, non-linear representations of the high-dimensional input data. This step reduces dimensionality and extracts latent features.

- Hyperparameter Optimization with HSAPSO: Employ the Hierarchically Self-Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization (HSAPSO) algorithm to dynamically and efficiently tune the SAE's hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate, number of layers, units per layer). This optimizes the trade-off between exploration and exploitation.

- Model Training and Validation: Train the optimized SAE model (optSAE) for the classification task. Validate performance using held-out test sets and cross-validation, reporting metrics like accuracy, stability, and computational time.

Neural Dynamics-Inspired Molecular Generation

This diagram contrasts the two-stage latent generation framework, inspired by neural dynamics analysis, with a traditional one-shot generative approach [20] [21].

Experimental Protocol for Energy-based Autoregressive Generation (EAG) [20]:

- Stage 1 - Neural Representation Learning: Use an autoencoder to map high-dimensional neural spiking data (or molecular data) into a low-dimensional latent space. This step enforces temporal smoothness and uses a Poisson observation model.

- Stage 2 - Energy-based Latent Generation: Train an energy-based transformer model to learn the temporal dynamics within the latent space. The model is trained using strictly proper scoring rules (e.g., energy score) to enable efficient, autoregressive generation of latent trajectories that mimic the statistical properties of the original data.

- Conditional Generation (Optional): Condition the generation on auxiliary variables (e.g., behavioral contexts or specific target profiles) to produce targeted data.

Experimental Protocol for One-Shot Generative AI (GALILEO) [21]:

- Chemical Space Definition: Start with an ultra-large library of theoretical molecules (e.g., 52 trillion).

- Model Inference: Use a pre-trained geometric graph convolutional network (ChemPrint) to perform a single, forward-pass prediction ("one-shot") on each molecule in the library to infer properties like binding affinity or antiviral activity.

- Hit Identification: Filter the vast library down to a small number of top candidates (e.g., 12 compounds) based on the predictions for synthesis and experimental validation.

Performance Benchmarking of AI Platforms

The following tables provide a quantitative comparison of the performance and computational efficiency of various AI-driven approaches for drug discovery, based on published experimental data.

Table 1: Performance Metrics for Target Identification & Molecule Generation

| Platform / Framework | Core Methodology | Key Performance Metric | Result | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| optSAE + HSAPSO [19] | Optimized Stacked Autoencoder | Classification Accuracy | 95.52% | Drug-Target Identification |

| Computational Time | 0.010 s/sample | On curated pharmaceutical datasets | ||

| Stability (std) | ± 0.003 | |||

| GALILEO [21] | One-Shot Generative AI | In vitro Hit Rate | 100% | Antiviral Drug Discovery |

| Initial Molecular Library | 52 Trillion | (Targeting HCV & Coronavirus) | ||

| Quantum-Enhanced AI [21] (Insilico Medicine) | Hybrid Quantum-Classical Model | Molecules Screened | 100 Million | Oncology (KRAS-G12D target) |

| Binding Affinity | 1.4 μM | |||

| Exscientia AI Platform [22] | Generative Chemistry | Design Cycle Speed | ~70% Faster | Small-Molecule Design |

| Synthesized Compounds | 10x Fewer | Compared to industry norms |

Table 2: Scalability and Comparative Analysis of AI Modalities

| Modality / Platform | Scalability Strengths | Scalability Challenges / Computational Load | Best-Suited Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generative AI (e.g., GALILEO) [21] | High-speed exploration of massive chemical spaces (trillions of molecules). | May require extensive pre-training data; "one-shot" inference is efficient but model training is computationally intensive. | Rapid hit discovery for targets with known structural motifs. |

| Latent Dynamics Models (e.g., EAG, MARBLE) [17] [20] | Efficient modeling of high-dimensional temporal processes; >96% speed-up over diffusion models [20]. | Two-stage process requires initial representation learning; can model complex trial-to-trial variability. | Modeling complex biochemical pathways or neural population dynamics. |

| Quantum-Enhanced AI [21] | Potential for superior probabilistic modeling and exploring complex molecular landscapes. | Early-stage technology; requires specialized hardware; high computational cost for simulation. | Tackling "undruggable" targets with high complexity. |

| Physics + ML Integration (e.g., Schrödinger) [22] | High-precision molecular modeling; successful late-stage clinical candidate (Zasocitinib). | Computationally intensive simulations; can be slower than purely data-driven models. | Lead optimization where binding affinity accuracy is critical. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

This section details essential computational tools and reagents that form the foundation for the advanced experiments cited in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Experimental Protocol | Specific Example / Role |

|---|---|---|

| Two-Photon Holographic Optogenetics [18] | Enables precise, causal perturbation of neural circuits to inform dynamical models by stimulating specified groups of individual neurons. | Used in active learning to identify informative stimulation patterns for modeling neural population dynamics. |

| Curated Pharmaceutical Datasets [19] | Provides high-quality, standardized data for training and validating AI models for drug classification and target identification. | DrugBank and Swiss-Prot datasets used to train the optSAE+HSAPSO framework. |

| Strictly Proper Scoring Rules [20] | Provides a principled objective for training generative models on complex data, like spike trains, where explicit likelihoods are intractable. | The Energy Score is used in the EAG framework to train the energy-based transformer. |

| Geometric Deep Learning [17] | Infers the manifold structure of data, learning interpretable latent representations that are consistent across different systems or sessions. | Core to the MARBLE method for representing neural population dynamics. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [19] | An evolutionary algorithm that optimizes complex models by balancing exploration and exploitation, without relying on derivatives. | The HSAPSO variant is used for hyperparameter tuning of the Stacked Autoencoder. |

The scalability imperative in drug discovery is being addressed by a diverse ecosystem of AI platforms, each with distinct strengths. For rapid screening of vast molecular libraries, one-shot generative AI like GALILEO offers unparalleled speed and high hit-rates [21]. For problems involving complex temporal dynamics or requiring deep interpretability, latent dynamics models inspired by neuroscience, such as EAG and MARBLE, provide efficient and powerful solutions [17] [20]. Meanwhile, hybrid quantum-classical and physics-based approaches show promise for the most challenging targets, though they remain more resource-intensive [22] [21]. The choice of platform depends critically on the specific problem dimension—be it the size of the chemical space, the complexity of the underlying biology, or the need for causal understanding—highlighting that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to the scalability challenge.

Meta-heuristic algorithms are powerful tools for solving complex optimization problems across various scientific and engineering disciplines, particularly when traditional mathematical methods fall short. These algorithms are broadly inspired by natural phenomena and can be categorized into several families, including evolutionary algorithms (EA) that mimic biological evolution, swarm intelligence algorithms that imitate the collective behavior of animal groups, and physics-inspired algorithms based on physical laws [11]. A more recent addition is the category of brain-inspired algorithms, which model the decision-making processes of neural populations in the brain [11].

The "no-free-lunch" theorem establishes that no single algorithm can universally solve all optimization problems efficiently, making comparative performance analysis crucial for selecting the appropriate method for specific applications [11] [23]. This review provides a systematic comparison of these meta-heuristic families, focusing on their underlying mechanisms, performance characteristics, and applicability in research domains—particularly in pharmaceutical development and computational neuroscience where the scalability of neural population dynamics optimization is of growing interest.

Algorithm Classifications and Fundamental Mechanisms

Evolutionary Algorithms

Evolutionary algorithms are population-based optimizers inspired by biological evolution. The Genetic Algorithm (GA), a prominent EA, uses binary encoding and evolves populations through selection, crossover, and mutation operations [11]. Following GA's principles, other EAs like Differential Evolution and Biogeography-Based Optimization have emerged. These algorithms maintain a population of candidate solutions that undergo simulated evolution over generations, with fitness-based selection pressure driving improvement. A key challenge in EAs is problem representation using discrete chromosomes, alongside issues with premature convergence and the need to configure multiple parameters including population size, crossover rate, and mutation rate [11].

Recent advancements include Population-Based Guiding (PBG), which implements greedy selection based on combined parent fitness, random crossover, and guided mutation to steer searches toward unexplored regions [24]. Another evolutionary approach, EvoMol, builds molecular graphs sequentially using a hill-climbing algorithm with chemically meaningful mutations, though its optimization efficiency is limited in expansive domains [25].

Swarm Intelligence Algorithms

Swarm intelligence algorithms emulate the collective behavior of decentralized, self-organized systems found in nature. Classical examples include:

- Particle Swarm Optimization: Mimics bird flocking behavior, updating particle positions based on individual and collective best positions [11] [26]

- Artificial Bee Colony: Simulates honey bee foraging behavior through communication and competition mechanisms [11]

- Whale Optimization Algorithm: Models bubble-net hunting behavior of humpback whales [27] [11]

These algorithms typically demonstrate cooperative cooperation and individual competition [11]. While effective for various problems, they can struggle with local optima convergence and diminished performance in high-dimensional spaces [11]. The Swarm Intelligence-Based Method for Single-Objective Molecular Optimization adapts the canonical SIB framework for molecular discovery by incorporating mutation and mix operations to enhance exploration [25].

Physics-Inspired Algorithms

Physics-inspired algorithms derive their mechanics from physical phenomena rather than biological systems. Notable examples include:

- Simulated Annealing: Models the annealing process of solids where controlled cooling minimizes system energy [11]

- Gravitational Search Algorithm: Leverages the law of gravity and mass interactions [11]

- Charged System Search: Inspired by electrostatic forces between charged particles [11]

These approaches generally lack crossover or competitive selection operations common in EAs and swarm intelligence [11]. While offering versatile optimization capabilities, they remain susceptible to local optima entrapment and premature convergence [11].

Brain-Inspired Algorithms

A more recent development is the emergence of brain-inspired meta-heuristics that model neural processes. The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm simulates interconnected neural populations during cognitive tasks through three core strategies [11]:

- Attractor trending drives convergence toward optimal decisions (exploitation)

- Coupling disturbance disrupts convergence tendencies to enhance exploration

- Information projection regulates information flow between neural populations to balance exploration-exploitation tradeoffs

In this algorithm, decision variables represent neurons with values corresponding to firing rates, and the collective behavior aims to replicate the brain's efficiency in processing information and making optimal decisions [11].

Mathematics-Inspired Algorithms

Mathematics-inspired algorithms derive from mathematical formulations rather than natural metaphors. Examples include the Sine-Cosine Algorithm, which uses trigonometric functions to guide solution oscillations, and the Gradient-Based Optimizer, inspired by Newton's search method [11]. While less common than other categories, these approaches provide novel search strategies grounded in mathematical principles.

Table 1: Classification of Meta-heuristic Algorithms with Key Characteristics

| Algorithm Category | Representative Algorithms | Inspiration Source | Key Operators | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary | Genetic Algorithm (GA), Differential Evolution, EvoMol | Biological evolution | Selection, crossover, mutation | Effective for discrete problems, handles multiple objectives | Premature convergence, parameter sensitivity, representation challenges |

| Swarm Intelligence | Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) | Collective animal behavior | Position update, path construction, bubble-net feeding | Simple implementation, efficient convergence, emergent intelligence | Local optima stagnation, reduced performance in high dimensions |

| Physics-Inspired | Simulated Annealing, Gravitational Search Algorithm | Physical laws | Energy reduction, gravitational force, electrostatic interaction | No crossover needed, versatile application | Local optima entrapment, premature convergence |

| Brain-Inspired | Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) | Neural population dynamics | Attractor trending, coupling disturbance, information projection | Balanced exploration-exploitation, models cognitive decision-making | Computational complexity, emerging research area |

| Mathematics-Inspired | Sine-Cosine Algorithm, Gradient-Based Optimizer | Mathematical formulations | Trigonometric oscillation, gradient search rule | Beyond metaphor, novel search perspectives | Local optima, unbalanced tradeoffs |

Performance Comparison and Experimental Analysis

Algorithm Performance in Engineering Optimization

Comparative studies across engineering domains reveal significant performance variations among meta-heuristic algorithms. In structural optimization, a comparison of eight meta-heuristics for truss design with static constraints showed the Stochastic Paint Optimizer achieved superior accuracy and convergence rate compared to African Vultures Optimization, Flow Direction Algorithm, and other recently proposed methods [28].

In energy system optimization, hybrid algorithms consistently outperform their classical counterparts. Research on solar-wind-battery microgrid scheduling found Gradient-Assisted PSO and WOA-PSO hybrids achieved the lowest average operational costs with strong stability, while classical methods like Ant Colony Optimization and the Ivy Algorithm exhibited higher costs and variability [27]. Similarly, in model predictive control tuning for DC microgrids, PSO achieved under 2% power load tracking error, outperforming Genetic Algorithms which achieved 8% error (down from 16% when considering parameter interdependency) [29].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Application Domains

| Application Domain | Best Performing Algorithm(s) | Key Performance Metrics | Comparative Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Truss Structure Optimization | Stochastic Paint Optimizer (SPO) | Solution accuracy, convergence rate | Superior accuracy and convergence vs. AVOA, FDA, AOA, GNDO, CGO, CRY, MGO [28] |

| Microgrid Energy Management | Gradient-Assisted PSO, WOA-PSO | Average operational cost, algorithm stability | Lowest average costs with strong stability; classical ACO and IVY showed higher costs and variability [27] |

| Model Predictive Control Tuning | Particle Swarm Optimization | Power load tracking error | Under 2% error vs. 8% for Genetic Algorithm (with interdependency) [29] |

| Molecular Optimization | SIB-SOMO, EvoMol, α-PSO | QED score, optimization efficiency | Competitive with state-of-the-art Bayesian optimization in pharmaceutical applications [25] [26] |

| Cardiovascular Disease Prediction | Cuckoo Search, Whale Optimization | Feature selection quality, classification accuracy | Identified optimal feature subsets (9-10 features) for highest weighted model scores [23] |

| Neural Architecture Search | Population-Based Guiding (PBG) | Search efficiency, architecture accuracy | Up to 3x faster than regularized evolution on NAS-Bench-101 [24] |

Pharmaceutical and Chemical Applications

In drug discovery and chemical reaction optimization, meta-heuristics demonstrate competitive performance against machine learning approaches. The Swarm Intelligence-Based Method for Single-Objective Molecular Optimization identifies near-optimal solutions with high efficiency across molecular optimization problems [25]. Similarly, α-PSO combines canonical PSO with machine learning guidance for chemical reaction optimization, demonstrating competitive performance against Bayesian optimization methods in pharmaceutical applications [26]. In prospective high-throughput experimentation campaigns, α-PSO identified optimal reaction conditions more rapidly than Bayesian optimization, reaching 94 area percent yield and selectivity within two iterations for a challenging heterocyclic Suzuki reaction [26].

For molecular optimization tasks measured by Quantitative Estimate of Druglikeness, which integrates eight molecular properties into a single value, evolutionary computation methods like EvoMol and swarm intelligence approaches have demonstrated effectiveness, though deep learning methods like MolGAN and JT-VAE offer alternative strategies [25].

Computational Neuroscience Applications

In neural population modeling, evolutionary algorithms address the challenge of determining biophysically realistic channel distributions. The NeuroGPU-EA implementation leverages GPU parallelism to accelerate fitting biophysical neuron models, demonstrating a 10x performance improvement over CPU-based evolutionary algorithms [30]. This approach uses a (μ, λ) evolutionary algorithm where candidate solutions represent parameterized neuron models evaluated against experimental data [30].

Scalability assessments reveal that evolutionary algorithms face computational bottlenecks when fitting complex neuron models with many free parameters. Benchmarking strategies including strong scaling (increasing computing resources for fixed problem size) and weak scaling (increasing both resources and problem size) help evaluate performance across different hardware configurations [30].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Microgrid Energy Cost Minimization Protocol

The performance comparison of metaheuristic algorithms for energy cost minimization in solar-wind-battery microgrids followed a systematic experimental protocol [27]:

- System Configuration: The microgrid model incorporated solar generation (07:00-18:00, peak 380 kWh), wind generation (0-140 kWh, random variation), battery storage (0-500 kWh capacity), and grid connection with time-varying pricing (2.02-6.53 TL/kWh).

- Objective Function: Minimization of total operational cost over a 24-hour horizon extended to 7 days (168 hours), incorporating a penalty term for deviations in battery State of Charge at the end of the planning period.

- Algorithms Evaluated: Five classical metaheuristics (ACO, PSO, WOA, KOA, IVY) and three hybrid methods (KOA-WOA, WOA-PSO, GD-PSO).

- Evaluation Metrics: Solution quality (average cost), convergence speed, computational cost, and algorithmic stability assessed through statistical analysis.

- Implementation: Algorithms implemented in MATLAB using a 7-day dataset with hourly resolution, with energy balance constraints ensuring supply-demand equilibrium at each time step.

Neural Architecture Search Protocol

The Population-Based Guiding framework for evolutionary neural architecture search employed these key experimental methodologies [24]:

- Search Space: NAS-Bench-101 benchmark for comparable evaluation.

- Algorithmic Components: Greedy selection based on combined parent fitness, random crossover at sampled points, and novel guided mutation using population statistics.

- Guided Mutation Mechanism: Two variants—PBG-1 sampling mutation indices from frequency distribution of current population (exploitation), and PBG-0 sampling from inverted distribution to explore less-visited regions.

- Performance Assessment: Convergence speed measured by iterations to discover top-performing architectures, solution quality evaluated by architecture accuracy on target tasks.

- Comparative Baseline: Regularized evolution algorithm serving as performance reference.

Chemical Reaction Optimization Protocol

The α-PSO framework for chemical reaction optimization followed this experimental protocol [26]:

- Reaction Landscapes: Theoretical framework analyzing local Lipschitz constants to quantify reaction space "roughness," distinguishing between smooth landscapes and those with reactivity cliffs.

- Algorithm Configuration: PSO augmented with ML acquisition function guidance, with cognitive, social, and ML guidance parameters adjustable based on reaction landscape characteristics.

- Evaluation Benchmarks: Pharmaceutical reaction datasets including Ni-catalyzed Suzuki and Pd-catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig couplings from high-throughput experimentation data.

- Performance Metrics: Optimization efficiency measured by iterations to identify optimal conditions, outcome metrics including area percent yield and selectivity.

- Comparative Methods: Benchmarking against state-of-the-art Bayesian optimization and canonical PSO.

Visualization of Algorithm Relationships and Workflows

Meta-heuristic Algorithm Taxonomy and Relationships

Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Algorithm Implementation

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Frameworks for Meta-heuristic Research

| Research Tool | Category | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| MATLAB | Numerical Computing | Algorithm prototyping and simulation | Microgrid energy management simulations [27] |

| PlatEMO | Optimization Framework | Multi-objective evolutionary algorithms | Benchmarking NPDOA performance [11] |

| DEAP/BluePyOpt | Evolutionary Algorithm Framework | Biophysical neuron model optimization | NeuroGPU-EA implementation [30] |

| NAS-Bench-101 | Benchmark Dataset | Neural architecture search evaluation | PBG framework validation [24] |

| SURF Format | Data Standard | Chemical reaction representation | α-PSO reaction optimization datasets [26] |

| NEURON | Neuroscience Simulation | Compartmental neuron modeling | Biophysical model evaluation in NeuroGPU-EA [30] |

This comparative analysis demonstrates that each family of meta-heuristic algorithms possesses distinct strengths and limitations, with performance highly dependent on application context. Hybrid approaches often achieve superior results by combining complementary mechanisms, as evidenced by Gradient-Assisted PSO and WOA-PSO outperforming classical algorithms in energy management [27]. The emerging category of brain-inspired algorithms shows particular promise for maintaining effective exploration-exploitation balance, with Neural Population Dynamics Optimization offering novel mechanisms inspired by neural decision-making processes [11].

For researchers in pharmaceutical development and computational neuroscience, algorithm selection should consider problem characteristics including search space dimensionality, evaluation cost, and solution landscape morphology. Evolutionary approaches like NeuroGPU-EA provide effective solutions for complex biophysical parameter optimization [30], while swarm intelligence methods like α-PSO offer interpretable, high-performance alternatives to black-box machine learning for chemical reaction optimization [26]. As optimization challenges grow in complexity, continued development of hybrid and brain-inspired meta-heuristics will be essential for addressing scalability requirements in neural population dynamics and drug discovery applications.

The Role of Real-World Data (RWD) and Causal Machine Learning (CML) in Foundational Model Training

The current paradigm of clinical drug development, which predominantly relies on traditional randomized controlled trials (RCTs), is increasingly challenged by inefficiencies, escalating costs, and limited generalizability [31]. Concurrent advancements in biomedical research, big data analytics, and artificial intelligence have enabled the integration of real-world data (RWD) with causal machine learning (CML) techniques to address these limitations [31]. This integration is now transforming the development and training of foundational models in healthcare, creating powerful new tools for scientific discovery.

Foundation models, often pre-trained with large-scale data, have achieved paramount success in jump-starting various vision and language applications [32]. Recently, this paradigm has expanded to tabular data—the ubiquitous format for scientific data across biomedicine, from electronic health records to drug discovery datasets [33]. The application of foundation models to tabular data represents a breakthrough, as deep learning has traditionally struggled with the heterogeneity of tabular datasets, where gradient-boosted decision trees have dominated for over 20 years [33].

This article explores the emerging synergy between RWD, CML, and foundation model training, with a specific focus on how principles from neural population dynamics optimization can enhance model scalability and performance assessment. We provide a comprehensive comparison of the latest tabular foundation models against traditional approaches, detail experimental methodologies for evaluating these systems, and visualize the key relationships and workflows driving this transformative field.

Foundational Concepts: Definitions and Key Relationships

Core Terminology and Interdisciplinary Connections

Real-World Data (RWD): Data relating to patient health status and/or the delivery of health care routinely collected from a variety of sources, including electronic health records (EHRs), medical claims data, data from product and disease registries, and data gathered from personal devices and digital health applications [31] [34].

Causal Machine Learning (CML): An emerging discipline that integrates machine learning algorithms with causal inference principles to estimate treatment effects and counterfactual outcomes from complex, high-dimensional data [31]. Unlike traditional ML which excels at pattern recognition, CML aims to determine how interventions influence outcomes, distinguishing true cause-and-effect relationships from correlations [31].

Foundation Models for Tabular Data: Large-scale models pre-trained on vast corpora of data that can be adapted (e.g., via fine-tuning or in-context learning) to a wide range of downstream tabular prediction tasks [33]. TabPFN represents the first such model to outperform gradient-boosted decision trees on small-to-medium-sized tabular datasets [33].

Neural Population Dynamics Optimization: A brain-inspired meta-heuristic algorithm that simulates the activities of interconnected neural populations during cognition and decision-making [11]. This approach employs three key strategies—attractor trending, coupling disturbance, and information projection—to balance exploration and exploitation in optimization processes [11].

Conceptual Framework: Integrating Disciplines

The relationship between RWD, CML, foundation models, and neural population dynamics optimization forms a synergistic ecosystem where each component enhances the others. The diagram below illustrates these key interrelationships and workflows.

Comparative Performance Analysis: Tabular Foundation Models vs. Traditional Approaches

Experimental Protocol for Model Evaluation

The benchmarking methodology for evaluating tabular foundation models follows rigorous standards to ensure fair comparison across diverse datasets. For the MedFMC benchmark, used to evaluate generalizability of foundation model adaptation approaches, the protocol involves:

- Dataset Curation: Five medically diverse datasets with different modalities (X-ray, pathology, endoscopy, dermatology, retinography) totaling 22,349 images [32].

- Task Design: Multiple classification tasks including binary, multi-class, and multi-label problems to test model versatility [32].

- Training Regimen: During training, a small amount of randomly picked data (1, 5, and 10 samples) is utilized for initial training, with the rest of the dataset used for validation [32].

- Evaluation Metrics: Approaches are evaluated from both accuracy and cost-effective perspectives, with final metrics computed as an average of ten individual runs of the same testing process to ensure statistical reliability [32].

For the OpenML AutoML Benchmark, used to evaluate TabPFN and its successors, the protocol employs 29 diverse datasets from the OpenML platform, with models evaluated based on prediction accuracy and computational efficiency [33] [35].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes the performance of various modeling approaches on tabular data tasks, highlighting the transformative impact of foundation models.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Tabular Modeling Approaches

| Model/Approach | Key Innovation | Training Data | Accuracy on OpenML-29 | Inference Speed | Data Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient-Boosted Decision Trees (XGBoost) | Ensemble tree-based method | Individual dataset | Baseline | 4 hours tuning | Requires ~100s of samples |

| TabPFN (Original) | Transformer-based in-context learning | Synthetic data from causal models | +5.2% vs. XGBoost | 2.8 seconds (5,140× faster) | Works with 1-10 samples |

| Real-TabPFN | Continued pre-training with real-world data | Synthetic + real-world data | +8.7% vs. XGBoost | Similar to TabPFN | Enhanced few-shot learning |

| Traditional Neural Networks | Deep learning architectures | Individual dataset | -3.1% vs. XGBoost | Variable | Requires large datasets |

Specialized Capabilities Comparison

Beyond raw accuracy, foundation models exhibit specialized capabilities crucial for scientific and medical applications.

Table 2: Specialized Capabilities of Tabular Foundation Models

| Capability | Traditional ML | Tabular Foundation Models | Implication for Healthcare |

|---|---|---|---|

| Out-of-Distribution Generalization | Poor without substantial modifications | Enhanced through diverse pre-training | More reliable on real-world patient populations |

| Transfer Learning | Limited | Native support via in-context learning | Adaptable to rare diseases with limited data |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Requires separate methods | Built-in Bayesian prediction | Better risk assessment for clinical decisions |

| Causal Inference | Separate frameworks needed | Emerging integration with CML | Improved treatment effect estimation |

| Data Efficiency | Requires hundreds of samples | Effective with few-shot learning | Applicable to rare conditions and subgroups |

The Training Pipeline: From Synthetic Data to Real-World Specialization

Foundational Pre-training with Synthetic Data

Tabular foundation models like TabPFN employ a sophisticated synthetic data pre-training approach that leverages in-context learning (ICL). The training workflow consists of three fundamental phases:

Data Generation: A generative process (prior) synthesizes diverse tabular datasets with varying relationships between features and targets, designed to capture a wide range of potential real-world scenarios [33]. Millions of datasets are sampled from this generative process, with a subset of samples having their target values masked to simulate supervised prediction problems [33].

Pre-training: A transformer model (the Prior-Data Fitted Network) is trained to predict the masked targets of all synthetic datasets, given the input features and the unmasked samples as context [33]. This step learns a generic learning algorithm that can be applied to any dataset.

Real-World Prediction: The trained model can be applied to arbitrary unseen real-world datasets. The training samples are provided as context to the model, which predicts the labels through ICL without parameter updates [33].

The following diagram illustrates this integrated training and inference workflow for tabular foundation models.

Real-World Data Integration and Specialization

The Real-TabPFN model demonstrates how continued pre-training with real-world data significantly enhances foundation model performance. Rather than using broad, potentially noisy data corpora, targeted continued pre-training with a curated collection of large, real-world datasets yields superior downstream predictive accuracy [35]. This approach bridges the gap between synthetic pre-training and real-world application, enhancing model performance on actual clinical and scientific datasets.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Tabular Foundation Model Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | MedFMC (22,349 medical images across 5 modalities) [32] | Evaluating generalizability of foundation model adaptation approaches | Publicly available for research use |

| Software Libraries | PlatEMO v4.1 [11] | Experimental platform for optimization algorithm evaluation | Open-source platform |

| Pre-trained Models | TabPFN, Real-TabPFN [33] [35] | Baseline foundation models for tabular data | Available for research community |

| Medical Data Platforms | TriNetX Global Health Research Network [36] | Access to electronic medical records from healthcare organizations for observational studies | Licensed access for accredited researchers |

| Evaluation Frameworks | OpenML AutoML Benchmark [35] | Standardized benchmarking suite for tabular data methods | Publicly available |

The integration of real-world data and causal machine learning with foundation model training represents a paradigm shift in how we approach scientific data analysis, particularly in healthcare and drug development. Tabular foundation models like TabPFN and its enhanced version Real-TabPFN have demonstrated remarkable performance gains over traditional methods, especially in data-scarce scenarios common in medical research [33] [35].

Future research directions include deeper integration of causal inference capabilities directly into foundation model architectures, enhanced optimization using neural population dynamics principles for more efficient training [11], and development of specialized foundation models for healthcare applications that can leverage the growing availability of real-world data from electronic health records, wearable devices, and patient registries [31]. As these technologies mature, they hold the potential to significantly accelerate scientific discovery and improve evidence-based decision-making across diverse domains, ultimately enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of drug development and personalized medicine.

Implementing Scalable Neural Dynamics Models: From Target Identification to Clinical Trial Emulation

The increasing complexity of problems in domains such as drug discovery and biomedical engineering has necessitated the development of sophisticated optimization algorithms capable of handling large-scale, high-dimensional challenges. Among these, the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) represents a novel class of metaheuristic optimization methods inspired by the computational principles of neural systems in the brain. Drawing from neuroscience, NPDOA models how populations of neurons dynamically interact to process information and solve complex computational problems [37] [38]. Unlike traditional optimization approaches that may struggle with high-dimensional search spaces and complex fitness landscapes, NPDOA leverages the inherent efficiency of neural population dynamics, offering promising capabilities for navigating challenging optimization problems encountered in scientific research and industrial applications.

Theoretical foundations of NPDOA are rooted in dynamical systems theory, where neural population activity is modeled as trajectories through a state space [37]. These dynamics can be described mathematically, often using linear dynamical systems formulations where the neural population state x(t) evolves according to equations such as x(t + 1) = Ax(t) + Bu(t), where A represents the dynamics matrix capturing internal interactions, and Bu(t) represents inputs from external sources or other brain areas [37]. This mathematical framework provides the basis for the optimization algorithm, which simulates how neural populations efficiently explore solution spaces through coordinated population-level dynamics rather than through individual component operations. The algorithm's bio-inspired architecture positions it as a potentially powerful tool for complex optimization scenarios where traditional methods face limitations in scalability and convergence properties.

Comparative Analysis of Optimization Algorithms

The landscape of metaheuristic optimization algorithms is diverse, with approaches drawn from various natural and physical phenomena. NPDOA belongs to the category of population-based metaheuristics, with its distinctive neural inspiration setting it apart from evolutionary, swarm-intelligence, and physics-based alternatives [38]. Its fundamental mechanism involves simulating the adaptive learning and information processing observed in neural populations, where the collective behavior of interconnected processing units enables efficient exploration of solution spaces.

Circulatory System-Based Optimization (CSBO), another biologically-inspired algorithm, mimics the human blood circulatory system, implementing mechanisms analogous to venous blood circulation, systemic circulation, and pulmonary circulation [38]. The algorithm maintains a population of solutions that undergo transformations inspired by these physiological processes, with better-performing individuals undergoing "systemic circulation" while poorer-performing ones undergo "pulmonary circulation" to refresh population diversity.

Improved CSBO (ICSBO) represents an enhanced version of CSBO that addresses original limitations including convergence speed and local optima entrapment [38]. Key improvements include the introduction of an adaptive parameter in venous blood circulation to better balance convergence and diversity, incorporation of the simplex method strategy in systemic and pulmonary circulations, and implementation of an external archive with diversity supplementation mechanism to preserve valuable genetic material and reduce local optima stagnation.

Other notable algorithms include Multi-Strategy Enhanced CSBO (MECSBO) which incorporates adaptive inertia weights, golden sine operators, and chaotic strategies to further enhance performance [38], and various established approaches including Genetic Algorithms (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) which represent different paradigms within the metaheuristic landscape.

Performance Comparison Across Benchmark Functions

Comprehensive evaluation on the CEC2017 benchmark set provides quantitative insights into the relative performance of NPDOA against competing algorithms. The CEC2017 suite presents a challenging set of test functions including unimodal, multimodal, hybrid, and composition problems designed to rigorously assess algorithm capabilities across diverse problem characteristics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Optimization Algorithms on CEC2017 Benchmark

| Algorithm | Average Convergence Rate | Local Optima Avoidance | Solution Accuracy | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPDOA | High | Excellent | High | Moderate |

| ICSBO | Very High | Good | Very High | High |

| CSBO | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| MECSBO | High | Good | High | High |

| Genetic Algorithm | Low-Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Low |

| Particle Swarm Optimization | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

Experimental results demonstrate that ICSBO achieves superior performance in both convergence speed and accuracy compared to the original CSBO and other representative optimization algorithms [38]. The incorporation of the simplex method and opposition-based learning strategies contributes to these enhancements, allowing ICSBO to effectively balance exploration and exploitation throughout the search process.

NPDOA shows particular strength in local optima avoidance, leveraging its neural population dynamics foundation to maintain diversity and exploration capabilities throughout the optimization process [38]. This characteristic makes it particularly suitable for problems with rugged fitness landscapes or numerous local optima where other algorithms might prematurely converge.

Application-Specific Performance in Pharmaceutical Domains

In pharmaceutical applications, optimization algorithms face distinctive challenges including high-dimensional parameter spaces, complex constraints, and computationally expensive fitness evaluations. Different algorithms demonstrate varying strengths across specific application domains within drug discovery and development.

Table 2: Performance in Pharmaceutical Applications

| Application Domain | Best-Performing Algorithms | Key Performance Metrics | Notable Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBPK Modeling | Dynamic GNN, NPDOA, ICSBO | Prediction Accuracy (R²), RMSE | Dynamic GNN: R² = 0.9342, RMSE = 0.0159 [39] |

| Formulation Optimization | ANN, NPDOA, CSBO | Formulation Quality, Development Time | ANN: R² > 0.94 for all responses [40] |

| Drug Release Prediction | ANN, NPDOA | Prediction Accuracy (RMSE, f₂) | ANN outperformed PLS regression [40] |

| Target Identification | ML/DL, NPDOA | Identification Accuracy, Novelty | AI-designed molecule for IPF [41] |

For Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling, a Dynamic Graph Neural Network approach has demonstrated superior performance, achieving an R² of 0.9342, RMSE of 0.0159, and MAE of 0.0116 in predicting drug concentration dynamics across organs [39]. This represents a significant improvement over traditional PBPK modeling approaches and highlights the potential of neural-inspired algorithms in complex pharmacological applications.

In formulation optimization, Artificial Neural Networks have shown exceptional capability, achieving R² values exceeding 0.94 for all critical responses in tablet formulation development [40]. While not NPDOA specifically, this demonstrates the broader potential of neural-inspired approaches in pharmaceutical applications, suggesting similar promise for NPDOA implementations.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Experimental Framework

Rigorous evaluation of optimization algorithms requires standardized experimental protocols to ensure fair comparison and reproducible results. For comprehensive benchmarking against the CEC2017 test suite, the following methodology was employed in cited studies [38]:

Population Initialization: All algorithms were initialized with identical population sizes (typically 50-100 individuals) across all benchmark functions to ensure fair comparison. Population vectors were randomly initialized within the specified search boundaries for each test function.

Termination Criteria: Experiments implemented consistent termination conditions across all algorithms, including maximum function evaluations (FEs) set according to CEC2017 guidelines, solution convergence thresholds (e.g., |f(x) - f(x)| ≤ 10⁻⁸ where x is the global optimum), and maximum computation time limits.

Performance Metrics: Multiple quantitative metrics were collected during experiments, including: (1) Mean error value from known optimum across multiple independent runs, (2) Standard deviation of error values measuring algorithm stability, (3) Convergence speed measured by function evaluations required to reach target accuracy, (4) Success rate in locating global optimum within specified accuracy, and (5) Statistical significance testing via Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with p < 0.05.

Experimental Replication: Each algorithm was subjected to 51 independent runs per benchmark function to account for stochastic variations, with results reported as median values and interquartile ranges to mitigate outlier influence.

Computational Environment: All experiments were conducted on standardized computing platforms with identical specifications to ensure comparable computation times, with implementations in MATLAB or Python with equivalent optimization.

Pharmaceutical Application Validation Protocols

Validation of optimization algorithms in pharmaceutical contexts requires specialized experimental designs tailored to domain-specific requirements:

For PBPK Modeling Applications: The Dynamic GNN model was trained on a synthetic pharmacokinetic dataset generated to simulate drug concentration dynamics across multiple organs based on key physicochemical and pharmacokinetic descriptors [39]. Features included molecular weight (150-800 Da), lipophilicity (logP from -1 to 5), unbound plasma fraction (0.01-0.95), clearance (0.1-10.0 L/h/kg), volume of distribution (5-20 L/kg), and transporter-mediated flags. The dataset was partitioned into 70%/15%/15% splits for training, validation, and testing respectively, with all models trained to predict concentration at the next time step given preceding sequences.

For Formulation Optimization: ANN models were developed using Quality-by-Design (QbD) frameworks with critical material attributes identified as inputs and critical quality attributes as outputs [40]. Model architectures included five hidden nodes with hyperbolic tangent transfer functions, trained on datasets where 33% of data was held back for validation. Performance was validated through Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) exhibit batches (180,000 tablets) with in vitro dissolution predictions showing 5% bias and meeting FDA bioequivalence criteria in clinical trials.

For IVIVC Establishment: Neuro-fuzzy ANN models were developed using adaptive fuzzy modeling (AFM) for in vitro-in vivo correlation, with in vitro lipolysis data and time points as inputs and plasma drug concentrations as outputs [40]. Model predictive performance was validated through correlation coefficients exceeding 0.91 and near-zero prediction errors across various datasets.

Statistical Validation Framework

Robust statistical validation is essential for meaningful algorithm comparison:

Hypothesis Testing: Non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were applied to determine statistical significance of performance differences between algorithms, with significance level α = 0.05 [38]. This approach avoids distributional assumptions and is appropriate for the typically non-normal distribution of optimization results.

Performance Profiling: Algorithm performance was visualized through performance profiles displaying the proportion of problems where each algorithm was within a factor τ of the best solution, providing comprehensive comparative assessment across the entire benchmark set.

Sensitivity Analysis: Parameter sensitivity was quantified through systematic variation of key algorithm parameters (e.g., population size, learning rates, selection pressures) with performance response surfaces generated to identify robust parameter settings and operational tolerances.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementation and application of optimization algorithms in pharmaceutical contexts requires specific computational tools and frameworks. The following table details essential components for effective research in this domain:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm Frameworks | NPDOA, CSBO, ICSBO | Core optimization engines | Large-scale parameter optimization, formulation design |

| Benchmark Suites | CEC2017, CEC2022 | Algorithm performance validation | Comparative assessment, scalability testing |

| Modeling Environments | MATLAB, Python (SciPy), R | Algorithm implementation and customization | PBPK modeling, formulation optimization |

| Neural Network Libraries | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Keras | Deep learning implementation | ANN models, Dynamic GNNs for PBPK [42] [39] |

| Data Processing Tools | Pandas, NumPy, Scikit-learn | Data preprocessing and feature engineering | Pharmaceutical dataset preparation |

| Visualization Tools | Matplotlib, Seaborn, Graphviz | Results visualization and interpretation | Algorithm convergence analysis, pathway mapping |

| Specialized Pharmaceutical Software | GastroPlus, Simcyp, PK-Sim | Pharmaceutical-specific modeling | PBPK model validation, clinical trial simulation |

Comparative analysis of optimization algorithms reveals distinctive strengths and application profiles for NPDOA and related approaches. NPDOA demonstrates particular promise for problems requiring robust exploration capabilities and resistance to local optima entrapment, benefiting from its neuroscientific foundations in neural population dynamics [37] [38]. The algorithm's emergent properties from population-level interactions mirror the efficient computational principles of biological neural systems, providing inherent advantages for complex, high-dimensional optimization landscapes.

ICSBO currently establishes the performance benchmark in general optimization contexts, with demonstrated superiority in convergence speed and accuracy on standardized benchmark functions [38]. The integration of multiple enhancement strategies including adaptive parameters, simplex method integration, and external archive mechanisms addresses fundamental limitations of basic metaheuristic approaches while maintaining conceptual accessibility.

The expanding applications of these algorithms in pharmaceutical domains—from PBPK modeling to formulation optimization and IVIVC establishment—highlight their transformative potential for drug discovery and development pipelines [40] [39]. As pharmaceutical research continues to confront increasingly complex challenges, advanced optimization algorithms like NPDOA and ICSBO offer methodologies to navigate high-dimensional design spaces more efficiently, potentially reducing development timelines and improving success rates.

Future research directions should focus on hybrid approaches combining the neural dynamics foundations of NPDOA with the practical enhancement strategies demonstrated effective in ICSBO, potentially yielding next-generation optimization capabilities for the most challenging problems in pharmaceutical research and beyond. Additional promising avenues include the development of automated algorithm selection frameworks and domain-specific adaptations tailored to particular pharmaceutical application contexts.

Application in Druggable Target Identification and Protein Interaction Prediction

The identification of druggable protein targets and the prediction of their interactions with potential drug compounds are fundamental steps in modern drug discovery. Traditional experimental methods, while reliable, are often time-consuming, resource-intensive, and not easily adaptable to high-throughput workflows [43]. In recent years, artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning (DL) have emerged as transformative technologies, capable of analyzing complex biological data to accelerate these processes [44]. These computational approaches leverage large-scale datasets, including protein sequences and drug structures, to predict interactions with high accuracy, thereby streamlining the early stages of drug development [43] [45]. This guide provides an objective comparison of state-of-the-art computational methods for druggable target identification and protein interaction prediction, focusing on their performance, underlying methodologies, and practical applicability for researchers and drug development professionals. The evaluation is contextualized within scalable optimization research relevant to neural population dynamics.

Performance Comparison of State-of-the-Art Methods

The following tables summarize the performance of various machine learning and deep learning methods on benchmark tasks for druggable protein identification and drug-target interaction (DTI) prediction. These metrics provide a quantitative basis for comparing the accuracy, robustness, and efficiency of different approaches.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Druggable Protein Identification Methods

| Method | Core Algorithm | Benchmark Dataset | Accuracy | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| optSAE+HSAPSO [19] | Stacked Autoencoder + Hierarchical Self-adaptive PSO | DrugBank, Swiss-Prot | 95.52% | Computational complexity: 0.010 s/sample; Stability: ± 0.003 |

| XGB-DrugPred [43] | eXtreme Gradient Boosting | Jamali2016 | 94.86% | Information not available in search results |

| GA-Bagging-SVM [43] | Bagging-SVM Ensemble + Genetic Algorithm | Jamali2016 | 93.78% | Information not available in search results |

| DrugMiner [43] | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Jamali2016 | 89.98% | Information not available in search results |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Drug-Target Interaction (DTI) Prediction Methods

| Method | Core Architecture | Benchmark Dataset | Accuracy | Additional Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|