Real-Time EEG Classification for Prosthetic Control: From Neural Decoding to Clinical Deployment

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of recent advancements in real-time electroencephalography (EEG) classification for intuitive prosthetic device control.

Real-Time EEG Classification for Prosthetic Control: From Neural Decoding to Clinical Deployment

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of recent advancements in real-time electroencephalography (EEG) classification for intuitive prosthetic device control. It explores the neuroscientific foundations of motor execution and motor imagery for generating classifiable brain signals, details the implementation of machine learning and deep learning models like EEGNet and temporal convolutional networks for signal decoding, and addresses critical challenges in signal noise, user training, and computational optimization for embedded systems. By evaluating performance benchmarks, hybrid neuroimaging approaches, and commercial translation pathways, this review synthesizes a roadmap for developing robust, clinically viable brain-computer interfaces that restore dexterous motor function, highlighting future directions in personalized algorithms, sensor fusion, and real-world integration for transformative patient impact.

The Neuroscience of Motor Commands: Decoding Intent from EEG Signals

An electroencephalography (EEG)-based Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) is a system that provides a direct communication pathway between the brain and external devices by interpreting EEG signals acquired from the scalp [1]. These systems translate specific patterns of brain activity into commands that can control computers, prosthetic limbs, or other assistive technologies without relying on the body's normal neuromuscular output channels [2] [3]. The foundation for EEG was established by Hans Berger who discovered in 1924 that the brain's electrical signals could be measured from the scalp, while the term "BCI" was later coined by Jacques Vidal in the 1970s [3] [1].

EEG-based BCIs are particularly valuable due to their non-invasive nature, portability, and relatively low cost compared to invasive methods such as electrocorticography (ECoG) or intracortical microelectrode recording [2] [1]. While EEG offers superior temporal resolution (on the millisecond scale), it suffers from relatively low spatial resolution compared to invasive techniques [3] [1]. These characteristics make EEG-based BCIs especially suitable for both clinical applications, such as restoring communication and motor function to individuals with paralysis, and non-medical domains including gaming and attention monitoring [1].

Core Principles of EEG Recording and Signal Types

EEG Signal Acquisition Principles

EEG measures electrical activity generated by the synchronized firing of neuronal populations in the brain, primarily capturing postsynaptic potentials from pyramidal cells [1]. As these electrical signals travel from their cortical origins to the scalp surface, they are significantly attenuated by intermediate tissues including the cerebrospinal fluid, skull, and skin, resulting in low-amplitude signals (microvolts, μV) that require substantial amplification [4]. This phenomenon, known as volume conduction, also blurs the spatial resolution of EEG, making it challenging to precisely localize neural activity sources [4].

The international 10-20 system provides a standardized method for electrode placement across the scalp, ensuring consistent positioning for reproducible measurements across subjects and sessions [5]. Modern BCI systems typically use multi-electrode arrays (ranging from 8 to 64+ channels) to capture spatial information about brain activity patterns [5] [1].

Major EEG Paradigms for BCI Control

EEG-based BCIs primarily utilize three major paradigms, each relying on distinct neural signals and mechanisms:

P300 Event-Related Potential (ERP): The P300 is a positive deflection in the EEG signal occurring approximately 300ms after a rare, task-relevant stimulus [2]. This response is typically elicited using an "oddball" paradigm where subjects focus on target stimuli interspersed among frequent non-target stimuli [2] [6]. The P300 potential reflects attention rather than gaze direction, making it suitable for users who lack eye-movement control [2]. Research has shown that stimulus characteristics significantly impact P300-BCI performance, with red visual stimuli yielding higher accuracy (98.44%) compared to green (92.71%) or blue (93.23%) stimuli in some configurations [6].

Sensorimotor Rhythms (SMR): SMRs are oscillations in the mu (8-12 Hz) and beta (18-30 Hz) frequency bands recorded over sensorimotor cortices [2]. These rhythms exhibit amplitude changes (event-related synchronization/desynchronization) during actual movement, movement preparation, or motor imagery [2]. Users can learn to voluntarily modulate SMR amplitudes to control external devices. While motor imagery initially facilitates SMR control, this process tends to become more implicit and automatic with extended training [2]. SMR-based BCIs have demonstrated particular utility for multi-dimensional control applications, including prosthetic devices [2] [7].

Steady-State Visual Evoked Potentials (SSVEP): SSVEPs are rhythmic brain responses elicited by visual stimuli flickering at constant frequencies, typically between 5-30 Hz [8]. When a user focuses on a stimulus flickering at a specific frequency, the visual cortex generates oscillatory activity at the same frequency (and harmonics), which can be detected through spectral analysis of the EEG signal [8]. SSVEP-based BCIs can support high information transfer rates and require minimal user training [2]. This paradigm has been successfully employed for various applications, including novel approaches to color vision assessment [8].

Table 1: Comparison of Major EEG-Based BCI Paradigms

| Paradigm | Neural Signal | Typical Latency/Frequency | Control Mechanism | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P300 ERP | Positive deflection ~300ms post-stimulus | 250-500ms | Attention to rare target stimuli | Spelling devices, communication aids [2] |

| Sensorimotor Rhythms (SMR) | Mu (8-12 Hz) and beta (18-30 Hz) oscillations | Frequency-specific power changes | Motor imagery or intention | Prosthetic control, motor rehabilitation [2] [4] |

| Steady-State VEP (SSVEP) | Oscillatory activity at stimulus frequency | 5-30 Hz steady-state response | Gaze direction/visual attention | High-speed spelling, color assessment [8] |

BCI System Architecture and Workflow

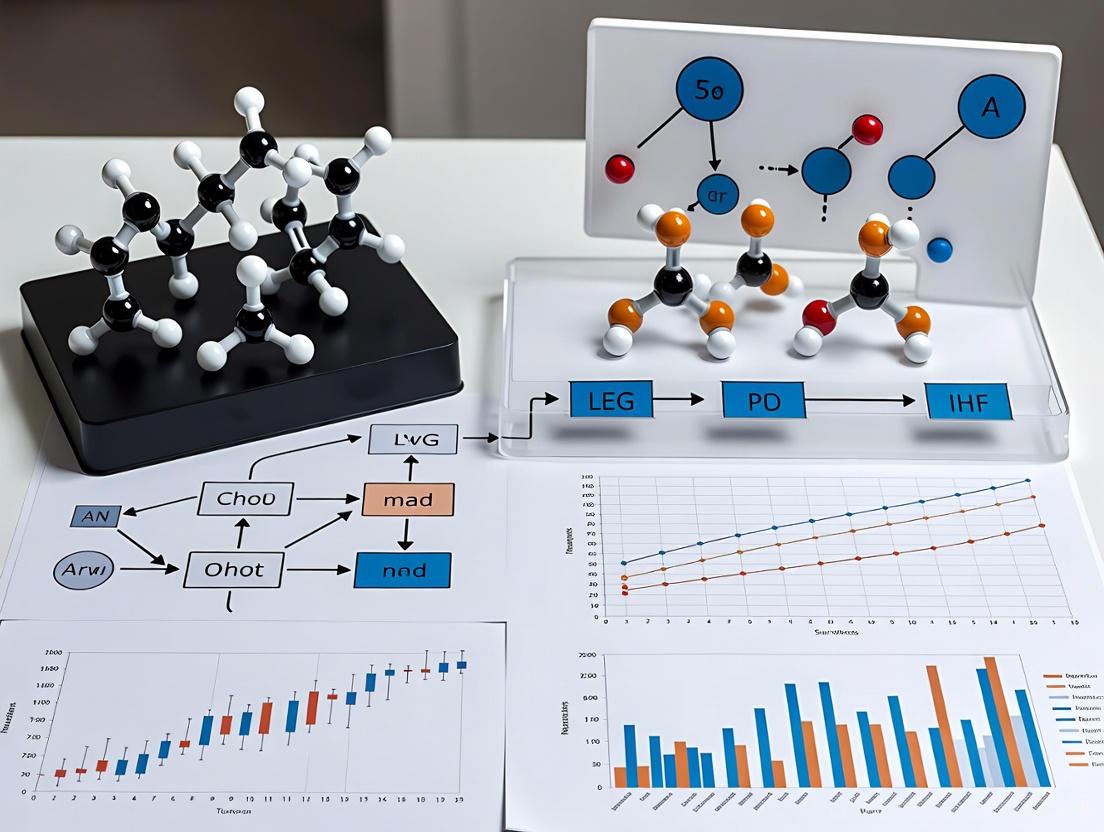

A typical EEG-based BCI system follows a structured processing pipeline consisting of four sequential stages: signal acquisition, preprocessing, feature extraction, and classification/translation [3] [1]. The diagram below illustrates this fundamental workflow and the transformation of raw brain signals into device commands.

Signal Acquisition and Preprocessing

The initial stage involves collecting raw EEG data using electrodes placed on the scalp according to standardized systems (e.g., 10-20 international system) [5]. Both wet and dry electrode configurations are used, with trade-offs between signal quality and usability [2]. Wet electrodes (using conductive gel) typically provide superior signal quality but require more setup time and maintenance, while modern dry electrode systems offer greater convenience for daily use [2].

Preprocessing aims to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio by removing various artifacts and interference [3]. Common preprocessing steps include:

- Filtering: Application of bandpass filters (e.g., 0.5-40 Hz for P300) to remove irrelevant frequency components and powerline noise [3]

- Artifact Removal: Elimination of signals originating from non-cerebral sources such as eye movements (EOG), muscle activity (EMG), or poor electrode contact using techniques like Independent Component Analysis (ICA) or Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) [3]

- Segmentation: Epoching of continuous EEG data into time-locked segments relative to stimulus onset or movement imagery [5]

Feature Extraction and Classification

Feature extraction identifies discriminative patterns in the preprocessed EEG signals that correlate with specific user intentions [3]. For P300 paradigms, this typically involves analyzing time-domain amplitudes within specific windows after stimulus presentation [6]. For SMR-based BCIs, features often include band power in specific frequency bands (mu, beta) or spatial patterns of oscillation [2]. SSVEP systems primarily rely on spectral power at stimulation frequencies and their harmonics [8].

Classification algorithms then map these features to specific output commands. Both traditional machine learning approaches (Linear Discriminant Analysis, Support Vector Machines) and modern deep learning architectures (EEGNet, Convolutional Neural Networks) have been successfully employed [7] [4]. The selected features and classification approach significantly impact the overall BCI performance and robustness.

Experimental Protocols for Prosthetic Control Applications

Motor Imagery Protocol for Multi-Degree Freedom Control

Objective: To train users in controlling a prosthetic arm/hand through motor imagery for real-time applications.

Materials:

- High-quality EEG acquisition system with at least 16 channels (focusing on central regions: C3, Cz, C4)

- Visual feedback display system

- Prosthetic arm/hand device or virtual simulation

- EEG processing software (e.g., BrainFlow, OpenViBE) [7]

Procedure:

- Preparation: Apply EEG cap according to 10-20 system. Ensure electrode impedances are below 10 kΩ for optimal signal quality.

- Calibration Session:

- Online Training:

- Provide real-time visual feedback of classifier output (e.g., cursor movement, prosthetic activation)

- Implement adaptive training where task difficulty increases with performance

- Conduct multiple sessions (3+ days) to account for inter-session variability [5]

- Prosthetic Control Integration:

- Map classifier outputs to specific prosthetic commands (e.g., hand open/close, wrist rotation)

- Implement hierarchical control for multiple degrees of freedom

- Incorporate error correction mechanisms and rest states

Data Analysis:

- Extract trial epochs time-locked to cue presentation

- Compute band power features in mu (8-12 Hz) and beta (18-26 Hz) frequency bands

- Train subject-specific classifiers using Linear Discriminant Analysis or Regularized Linear Regression

- Evaluate performance using cross-validation and online accuracy metrics

P300-Based Robotic Hand Control Protocol

Objective: To enable individual finger-level control of a robotic hand using P300 responses.

Materials:

- 64-channel EEG system for comprehensive coverage

- Robotic hand prototype with individually controllable fingers

- Visual stimulation interface with finger-specific targets

- Real-time signal processing platform (e.g., NVIDIA Jetson) [7]

Procedure:

- Stimulus Design:

- Create visual interface displaying representations of each finger

- Implement oddball paradigm with intensification of individual finger stimuli

- Set stimulus parameters: duration 200ms, inter-stimulus interval 400ms [6]

- Training Protocol:

- Instruct user to focus on target finger and mentally count each time it flashes

- Record EEG during stimulation sequences

- Collect data for all finger combinations (thumb, index, middle, ring, pinky)

- Online Implementation:

- Extract P300 features from central-parietal electrodes (Cz, Pz, P3, P4)

- Apply ensemble classification with deep learning models (EEGNet)

- Map detected P300 responses to specific finger movements

- Incorporate fine-tuning mechanisms to adapt to inter-session variability [4]

Table 2: Performance Metrics for EEG-Based Prosthetic Control Systems

| System | Control Paradigm | Accuracy (%) | Latency | Degrees of Freedom | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CognitiveArm [7] | Motor Imagery | 90% (3-class) | Real-time (<100ms) | 3 DoF | On-device processing enabled low-latency control |

| Individual Finger BCI [4] | ME/MI Hybrid | 80.56% (2-finger) 60.61% (3-finger) | Real-time | Individual fingers | Fine-tuning enhanced performance across sessions |

| SSVEP Color Assessment [8] | SSVEP Minimization | ~98% (CVD detection) | N/A | N/A | Automated metamer identification successful |

Technical Implementation and Hardware Considerations

EEG Recording Technologies

Effective BCI systems require reliable, high-quality EEG recording capabilities. Several electrode technologies are currently available:

Wet Electrodes: Traditional Ag/AgCl electrodes using conductive gel provide excellent signal quality but require careful application, periodic gel replenishment, and can be uncomfortable for long-term use [2].

Dry Electrodes: Emerging technologies including g.SAHARA (gold-plated pins) and QUASAR (hybrid resistive-capacitive) systems offer more convenient alternatives with comparable performance for certain BCI paradigms [2]. These are particularly advantageous for home use and long-term applications.

Electrode Positioning Systems: The physical device holding electrodes significantly impacts signal quality and user comfort. Ideal systems should accommodate different head sizes and shapes, maintain secure electrode placement, and be reasonably unobtrusive [2]. Comparative studies have found that systems like the BioSemi provide superior accommodation for anatomical variations [2].

Embedded Processing for Real-Time Control

Real-time prosthetic control demands efficient processing of EEG signals on resource-constrained embedded hardware. The CognitiveArm system demonstrates a successful implementation using:

- Evolutionary Search Algorithms to identify Pareto-optimal deep learning configurations through hyperparameter tuning and window selection [7]

- Model Compression Techniques including pruning and quantization to reduce computational demands while maintaining accuracy [7]

- Edge AI Hardware such as NVIDIA Jetson platforms for low-latency processing without cloud dependence [7]

This approach achieved 90% classification accuracy for three core actions (left, right, idle) while running entirely on embedded hardware, demonstrating the feasibility of real-time prosthetic control [7].

Applications in Neurorehabilitation and Future Directions

BCI technology holds significant promise for enhancing neurorehabilitation, particularly for individuals with stroke, spinal cord injuries, or neuromuscular disorders [2] [3]. The design of rehabilitation applications hinges on the nature of BCI control and how it might be used to induce and guide beneficial plasticity in the brain [2]. By creating closed-loop systems where brain activity directly controls prosthetic movements, BCIs can promote neural reorganization and functional recovery [2].

Future developments in EEG-based BCIs will likely focus on improving signal acquisition hardware for greater comfort and reliability, developing more adaptive signal processing algorithms that accommodate non-stationary EEG signals, and creating more intuitive control paradigms that reduce user cognitive load [2] [1]. Additionally, hybrid BCI systems combining multiple signal modalities (e.g., EEG + EOG, EEG + EMG) may enhance robustness and information transfer rates for complex prosthetic control applications [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for EEG-Based BCI Research

| Item | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| EEG Acquisition System | Records electrical brain activity from scalp | OpenBCI UltraCortex Mark IV, Biosemi, Neuracle 64-channel [7] [5] |

| Electrode Technologies | Interface between scalp and recording system | Wet electrodes (Ag/AgCl with gel), Dry electrodes (g.SAHARA, QUASAR) [2] |

| Signal Processing Library | Real-time EEG analysis and feature extraction | BrainFlow (open-source for data acquisition and streaming) [7] |

| Deep Learning Framework | EEG pattern recognition and classification | EEGNet, CNN, LSTM, Transformer models [7] [4] |

| Edge Computing Platform | On-device processing for low-latency control | NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano, embedded AI processors [7] |

| Prosthetic Arm Platform | Physical implementation of BCI control | 3-DoF prosthetic arms, robotic hands with individual finger control [7] [4] |

| Visual Stimulation System | Presents paradigms for evoked potentials | LCD monitors with precise timing (Psychtoolbox for MATLAB) [6] |

| Data Annotation Pipeline | Labels EEG signals with corresponding actions | Custom software for precise temporal alignment of trials [7] |

In the pursuit of intuitive, brain-controlled prosthetic devices, the neural processes of motor execution (ME) and motor imagery (MI) represent two foundational pillars for brain-computer interface (BCI) development. The "functional equivalence" hypothesis posits that MI and ME share overlapping neural substrates, activating a distributed premotor-parietal network including the supplementary motor area (SMA), premotor area (PMA), primary sensorimotor cortex, and subcortical structures [9] [10]. However, critical distinctions exist in their neural signatures, intensity, and functional connectivity patterns, which directly impact their application in real-time electroencephalography (EEG) classification for prosthetic control [11] [10].

Understanding these shared and distinct neural mechanisms is crucial for developing more robust and intuitive neuroprosthetics, particularly for individuals with limb loss who cannot physically execute movements but can imagine them [12]. This application note details the key neural correlates, provides experimental protocols for their investigation, and discusses their implications for prosthetic control systems.

Neural Correlates: A Comparative Analysis

Overlapping Networks with Distinct Key Nodes

Neuroimaging studies confirm that ME and MI activate a similar network of brain regions. However, graph theory analyses of functional connectivity reveal that they possess different key nodes within this network. During ME, the supplementary motor area (SMA) serves as the central hub, whereas during MI, the right premotor area (rPMA) takes on this role [10]. This suggests that while the overall network is similar, the flow of information and control is prioritized differently—ME emphasizes integration with the SMA, likely for detailed motor command execution, while MI relies more heavily on the premotor cortex for movement planning and simulation [10].

Spectral Power Modulations in EEG

Mobile EEG studies during whole-body movements like walking show that MI reproduces many of the oscillatory patterns seen in ME, particularly in the alpha (8-13 Hz) and beta (13-35 Hz) frequency bands. Both conditions exhibit event-related desynchronization (ERD), a power decrease linked to cortical activation, during movement initiation [9]. Furthermore, a distinctive beta rebound (power increase) occurs at the end of both actual and imagined walking, suggesting a shared process of resetting or inhibiting the motor system after action completion [9].

The critical difference lies in the intensity and distribution of these signals. MI elicits a more distributed pattern of beta activity, especially at the task's beginning, indicating that imagined movement requires the recruitment of additional, possibly more cognitive, cortical resources in the absence of proprioceptive feedback [9].

Corticospinal Excitability and Intracortical Circuits

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) studies provide a more granular view of the motor cortex's state during ME and MI. While both states facilitate corticospinal excitability, the effect is significantly stronger after ME than after MI [11]. Research indicates that this difference in excitability is not due to changes in short-interval intracortical inhibition (SICI) but is primarily attributed to the differential activation of intracortical excitatory circuits [11].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Motor Execution and Motor Imagery Neural Correlates

| Neural Feature | Motor Execution (ME) | Motor Imagery (MI) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Network | Distributed premotor-parietal network (SMA, PMA, M1, S1, cerebellum) | Overlapping network with ME, but with different key nodes | [9] [10] |

| Key Node (Graph Theory) | Supplementary Motor Area (SMA) | Right Premotor Area (rPMA) | [10] |

| EEG Spectral Power | Alpha/Beta ERD during action; Beta rebound post-action | Similar pattern but with more distributed beta activity; Beta rebound post-action | [9] |

| Corticospinal Excitability | Strong facilitation | Weaker facilitation | [11] |

| Primary Motor Cortex (M1) Involvement | Direct movement execution, strong sensory feedback | Represents motor information, but activation is weaker and more transient | [13] |

| Primary Somatosensory (S1) Involvement | Strong activation due to sensory feedback | Significantly less activation due to lack of movement | [13] |

Experimental Protocols for EEG Investigation

Protocol 1: Mobile EEG for Whole-Body Movement Analysis

This protocol is designed to capture the neural dynamics of naturalistic actions like walking, which is highly relevant for lower-limb prosthetics.

- Objective: To compare neural oscillatory patterns (ERD/ERS) in alpha and beta bands during executed and imagined walking.

- Equipment: Mobile EEG system with active electrodes (e.g., 32-channel setup), a computer for stimulus presentation, and a clear, safe walking path.

- Participant Preparation: Fit the EEG cap according to the 10-20 system. Ensure electrode impedances are below 10 kΩ. Apply conductive gel if using wet electrodes.

- Experimental Paradigm:

- Conditions: The experiment should include three conditions in randomized order:

- Motor Execution (ME): Participant walks six steps on the path.

- Motor Imagery (MI): Participant vividly imagines walking six steps without any overt movement.

- Control Task: Participant performs a non-motor task (e.g., mental counting from one to six).

- Trial Structure: Each trial begins with a fixation cross (2 s), followed by an auditory or visual cue indicating the condition (e.g., "Walk," "Imagine Walking," "Count") (1 s). This is followed by the action/imagery period (duration determined by the task, e.g., ~5-10 s for six steps), and ends with a rest period (10-15 s).

- Blocks: Conduct 5-6 blocks, with each block containing 10-15 trials per condition. Provide rest periods between blocks.

- Conditions: The experiment should include three conditions in randomized order:

- Data Processing & Analysis:

- Preprocessing: Bandpass filter raw EEG data (e.g., 0.5-45 Hz). Apply artifact removal techniques (e.g., ICA) to correct for eye blinks and muscle noise.

- Time-Frequency Analysis: For each condition, calculate event-related spectral perturbation (ERSP) in the alpha and beta bands. Focus on electrodes over the sensorimotor cortex (e.g., C3, Cz, C4).

- Statistical Comparison: Use non-parametric cluster-based permutation tests to identify significant differences in ERD/ERS patterns between ME, MI, and the control condition [9].

Protocol 2: Real-Time EEG Decoding for Individual Finger Movements

This protocol is critical for developing dexterous upper-limb prosthetic control.

- Objective: To train a subject-specific decoder for classifying individual finger movements from MI or ME EEG signals for real-time robotic control.

- Equipment: High-density EEG system (e.g., 32+ channels), a robotic hand or visual feedback system, a computer with real-time BCI software (e.g., BCILAB, OpenVibe).

- Participant Preparation: Same as Protocol 1. Position the participant comfortably with their hand resting on a table.

- Experimental Paradigm:

- Offline Training Session:

- Cue-Based Tasks: Present visual cues indicating which finger to move or imagine moving (e.g., thumb, index, pinky). Use a blocked design, with each trial consisting of a rest period (3 s), a cue period (2 s), and the movement/imagery period (4 s).

- Data Collection: Collect a minimum of 50-100 trials per finger movement class.

- Online Control Session:

- Model Training: Train a subject-specific decoder (e.g., a deep learning model like EEGNet or an SVM) on the collected offline data.

- Real-Time Feedback: Participants perform MI of the finger movements. The decoded output is used to control the movement of a corresponding robotic finger in real-time, providing closed-loop feedback [4].

- Offline Training Session:

- Data Processing & Analysis:

- Feature Extraction: Extract spatial-spectral features from the EEG signals. Common approaches include Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) or feeding raw data into a deep neural network.

- Model Training & Fine-Tuning: Train a classifier to discriminate between the different finger movement intentions. For deep learning models, employ a fine-tuning strategy using data from the online session to adapt the model and combat inter-session variability [4].

- Performance Metrics: Evaluate system performance using online decoding accuracy, precision, and recall for each finger class.

Diagram 1: Real-time EEG Classification Workflow for Prosthetic Control

Application in Prosthetic Control

The translation of ME and MI research into functional prosthetic control has seen significant advances. Non-invasive BCIs can now decode finger-level movements with sufficient accuracy for real-time robotic hand control. Recent studies achieved real-time decoding accuracies of 80.56% for two-finger MI tasks and 60.61% for three-finger tasks using deep neural networks [4]. This level of dexterity is a substantial step toward restoring fine motor skills.

For lower-limb prosthetics, the identification of locomotion activities is crucial. Machine learning models, such as Random Forest, have been applied to EEG signals to classify activities like level walking, ascending stairs, and descending ramps with accuracies exceeding 90% [14]. This demonstrates the potential for creating lower-limb prosthetics that can anticipate the user's intent to change locomotion mode.

A primary challenge in this domain is the performance gap between ME and MI. MI-based BCIs are often less reliable and require more user training than ME-based systems [12]. This is likely due to the weaker and more variable neural signals generated during imagination. Furthermore, body position compatibility affects MI performance; imagining an action is most effective when the body is in a congruent posture [9]. This has implications for designing training protocols for amputees.

Table 2: BCI Performance in Prosthetic Control Applications

| Application | Control Signal | Classification Task | Reported Performance | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robotic Hand Control | Motor Imagery (MI) of fingers | 2-finger vs. 3-finger MI tasks | 80.56% (2-finger)60.61% (3-finger) | Deep learning (EEGNet) with fine-tuning enables real-time individual finger control. | [4] |

| Locomotion Identification | EEG during walking | Walking, Ascending/Descending Stairs/Ramps | Up to 92% accuracy | Random Forest classifier outperformed kNN; feasible for prosthesis control input. | [14] |

| Embedded Prosthetic Control (CognitiveArm) | EEG for arm actions | Left, Right, Idle intentions | Up to 90% accuracy | On-device DL on embedded hardware (NVIDIA Jetson) achieves low-latency real-time control. | [7] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials and Solutions for EEG-Based Prosthetic Control Research

| Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| EEG Acquisition System | 32-channel mobile system (e.g., from g.tec, OpenBCI); Active electrodes; Wireless capability. | Records scalp electrical activity with high temporal resolution; mobility enables naturalistic movement studies. |

| Conductive Gel / Paste | Electro-gel, Ten20 paste, SignaGel. | Ensures high conductivity and reduces impedance between EEG electrodes and the scalp, improving signal quality. |

| Robotic Hand / Prosthesis | 3D-printed multi-finger robotic hand; Commercially available prosthetic arm (e.g., with 3 DoF). | Provides physical actuation for real-time closed-loop feedback and validation of decoding algorithms. |

| Stimulus Presentation Software | Psychtoolbox (MATLAB), Presentation, OpenSesame. | Prescribes the experimental paradigm, delivers precise visual/auditory cues, and records event markers. |

| Signal Processing & BCI Platform | EEGLAB, BCILAB, BrainFlow, OpenVibe, Custom Python/MATLAB scripts. | Performs preprocessing, feature extraction, and real-time classification of EEG signals. |

| Deep Learning Framework | EEGNet, CNN, LSTM, PyTorch, TensorFlow. | Provides state-of-the-art architectures for decoding complex spatial-temporal patterns in EEG data. |

| Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) | TMS apparatus with figure-of-eight coil. | Investigates corticospinal excitability and intracortical circuits (SICI, ICF) during ME and MI. |

Diagram 2: Neural Pathways of Motor Execution vs. Motor Imagery

Electroencephalography (EEG)-based Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) represent a transformative technology for establishing a direct communication pathway between the human brain and external devices, bypassing traditional neuromuscular channels [15]. This capability is particularly vital for restoring communication and motor control to individuals severely disabled by devastating neuromuscular disorders and injuries [15]. For prosthetic device control, two primary categories of EEG signals have emerged as critical: endogenous Sensorimotor Rhythms (SMR), which are spontaneous oscillatory patterns modulated by motor intention, and exogenous Event-Related Potentials (ERPs), which are time-locked responses to specific sensory or cognitive events [15] [16]. This application note details the characteristics, experimental protocols, and practical implementation considerations for these key rhythms within the context of real-time EEG classification research for advanced prosthetic control.

Key EEG Rhythms for Prosthetic Control

Sensorimotor Rhythms (SMR)

Sensorimotor rhythms are oscillatory activities recorded over the sensorimotor cortex and are among the most widely used signals for non-invasive BCI control, enabling continuous and intuitive multi-dimensional control [15].

- Neurophysiological Basis: SMRs are modulated by actual movement, motor intention, or motor imagery (MI). The primary observable phenomenon is Event-Related Desynchronization (ERD)—a decrease in power in the alpha (8-13 Hz, also known as mu rhythm) and beta (14-26 Hz) frequency bands—which is accompanied by an increase in the gamma band (>30 Hz), known as Event-Related Synchronization (ERS) [15]. These modulations are organized in a somatotopic manner along the primary sensorimotor cortex (the Homunculus), allowing discrimination between the imagination of moving different body parts [15].

- Application in Prosthetics: SMR-based BCIs have demonstrated the capability for multi-dimensional prosthesis control, including 2D and 3D movement [15] [17]. Recent advances show that SMRs can even be decoded for individual finger movements, enabling real-time control of a robotic hand at the finger level with accuracies of 80.56% for two-finger and 60.61% for three-finger motor imagery tasks [4].

Event-Related Potentials (ERPs)

ERPs are brain responses that are time-locked to a specific sensory, cognitive, or motor event. They are characterized by their latency and polarity.

- The P300 Potential: The most prominent ERP for BCI control is the P300, a positive deflection in the EEG signal occurring approximately 300 ms after the presentation of a rare or task-relevant stimulus amidst a stream of standard or frequent stimuli [16]. Its amplitude is linked to the attention directed towards the infrequent stimulus.

- Application in Prosthetics: P300-based BCIs are often implemented in a discrete control paradigm. For example, a user might select a target from a matrix of choices (e.g., different grip types or movements on a screen). This offers a high-accuracy, low-speed control channel suitable for issuing discrete commands to a prosthetic device [16].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of SMR and ERP for BCI Control

| Feature | Sensorimotor Rhythms (SMR) | Event-Related Potentials (P300) |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Type | Endogenous, spontaneous oscillations | Exogenous, evoked response |

| Control Paradigm | Continuous, asynchronous | Discrete, synchronous |

| Key Phenomenon | ERD/ERS in Alpha (Mu) & Beta bands | Positive peak ~300ms post-stimulus |

| Primary Mental Strategy | Motor Imagery (MI) / Motor Execution (ME) | Focused attention on a rare stimulus |

| Typical Control Speed | Moderate to High (Continuous control) | Low (Sequential selection) |

| Information Transfer Rate | Variable, can be high with user skill | Typically lower than SMR |

| Key Advantage | Intuitive, continuous, multi-dimensional control | Requires little to no training, high accuracy |

Quantitative Data and Performance

The performance of EEG-based prosthetic control systems is rapidly advancing. The tables below summarize key quantitative metrics from recent research.

Table 2: Recent Performance Metrics in EEG-Based Prosthetic Control

| Study / System | Control Type | EEG Rhythm Used | Classification Accuracy | Tasks / Degrees of Freedom (DoF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIBRA NeuroLimb [18] | Hybrid (EEG + sEMG) | SMR | 76% (EEG only) | Real-time control of a prosthesis with 3 active DoF |

| Finger-Level Control [4] | SMR (MI/ME) | SMR | 80.56% (2-finger), 60.61% (3-finger) | Individual robotic finger control |

| CognitiveArm [7] | SMR (MI) | SMR | Up to 90% | 3 DoF prosthetic arm control (Left, Right, Idle) |

| Large SMR-BCI Dataset [17] | SMR (MI) | SMR (ERD/ERS) | Variable (User-dependent) | 1D, 2D, and 3D cursor control |

Table 3: Key Frequency Bands and Their Functional Roles in SMR-BCIs

| Frequency Band | Common Terminology | Functional Correlation in Motor Tasks |

|---|---|---|

| 8-13 Hz | Mu Rhythm, Low Alpha | Strong ERD during motor planning and execution/imagery of contralateral limbs [15]. |

| 14-26 Hz | Beta Rhythm | ERD during movement, followed by ERS (beta rebound) after movement cessation [15]. |

| >30 Hz | Gamma Rhythm | ERS associated with movement and sensorimotor processing; more easily recorded with ECoG [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Real-Time EEG Classification

General SMR-BCI Protocol for Prosthetic Control

This protocol outlines the standard methodology for acquiring and utilizing SMR signals for continuous prosthetic control, based on established practices in the field [15] [17] [4].

Participant Preparation and EEG Setup:

- Equipment: A 64-channel EEG cap arranged according the international 10-10 system is recommended for sufficient spatial resolution [17] [4]. Impedance for each electrode should be reduced to below 5-10 kΩ to ensure high-quality signal acquisition [17].

- Calibration: Precisely measure the distances between nasion, inion, and preauricular points to ensure correct cap positioning [17].

Experimental Paradigm and Task Instruction:

- Participants are seated comfortably in a chair facing a computer monitor for feedback.

- Instruction: Participants are instructed to perform kinesthetic motor imagery (e.g., "Imagine opening and closing your left hand without actually moving it") to control a prosthetic device or a cursor on a screen [17]. The imagined movement should be correlated with a specific output command (e.g., hand close, elbow flexion).

Data Acquisition and Real-Time Processing:

- Recording: EEG signals are digitized at a sampling rate of 1000 Hz and band-pass filtered between 0.1-200 Hz, with a 60 Hz (or 50 Hz) notch filter applied to suppress line noise [17] [4].

- Feature Extraction: In real-time, the EEG data is processed to extract features. Common features include the band power in specific frequency bands (e.g., mu, beta) from channels over the sensorimotor cortex (e.g., C3, Cz, C4). The log-variance of the signals after spatial filtering (e.g., using Common Spatial Patterns) is also a highly effective feature [15] [4].

- Classification: A classifier (e.g., Linear Discriminant Analysis or a deep learning model like EEGNet) translates the extracted features into a continuous control signal [4] [7]. For example, the intensity of motor imagery can be mapped to the velocity or position of a prosthetic joint.

Feedback and Training:

- Participants receive real-time visual (cursor movement) and/or physical (robotic hand movement) feedback based on the classifier's output [4].

- Training occurs across multiple sessions (e.g., 7-11 sessions) to allow users to learn to modulate their SMR more effectively and for the classifier to adapt to the user [17].

Protocol for Individual Finger Decoding

This advanced protocol enables fine control at the finger level, a recent breakthrough in non-invasive BCI [4].

Offline Model Training Session:

- Participants perform executed or imagined movements of individual fingers (e.g., thumb, index, pinky) of the dominant hand in a cue-based paradigm.

- High-density EEG (64 channels) is recorded during these tasks.

- A subject-specific deep learning model (e.g., EEGNet) is trained on this data to discriminate between the different finger movement intentions [4].

Online Real-Time Control Sessions:

- The pre-trained model is used for real-time decoding.

- Fine-Tuning: To combat inter-session variability, the base model is fine-tuned at the beginning of each online session using a small amount of newly collected data, which significantly enhances performance [4].

- Feedback: Participants receive two forms of feedback: (1) visual (the target finger on a screen changes color to indicate correct/incorrect decoding), and (2) physical, from a robotic hand that moves the decoded finger in real time [4].

SMR-BCI Control Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details the essential hardware, software, and methodological "reagents" required for developing real-time EEG classification systems for prosthetic control.

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for EEG-Based Prosthetic Control Research

| Category | Item / Solution | Function and Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware | High-Density EEG System (64+ channels) | Gold-standard for signal acquisition and source localization. Enables individual finger decoding [4]. |

| Portable EEG System (32 channels) | Enables community-based and more naturalistic data collection with comparable data quality to lab systems [19]. | |

| OpenBCI UltraCortex Mark IV | A popular, customizable, and relatively low-cost EEG headset used in research prototypes [7]. | |

| Robotic Hand / Prosthetic Arm | A physical output device for providing real-time feedback and validating control algorithms (e.g., 3-DoF arms) [4] [7]. | |

| Embedded AI Hardware (NVIDIA Jetson) | Enables real-time, on-device processing of EEG signals, critical for low-latency prosthetic control outside the lab [7]. | |

| Software & Algorithms | BrainFlow Library | An open-source library for unified data acquisition and streaming from various EEG amplifiers [7]. |

| EEGNet (Deep Learning Model) | A compact convolutional neural network architecture designed for EEG-based BCIs, achieving state-of-the-art performance [4]. | |

| Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) | A spatial filtering algorithm optimal for maximizing the variance between two classes of SMR data [15]. | |

| Model Compression Techniques (Pruning, Quantization) | Reduces the computational complexity and memory footprint of deep learning models for deployment on resource-constrained edge devices [7]. | |

| Methodological Concepts | Kinesthetic Motor Imagery (KMI) | The mental rehearsal of a movement without execution; the primary cognitive strategy for modulating SMR [16]. |

| End-to-End System Integration | The practice of creating a closed-loop system that integrates sensing, processing, and actuation, which is crucial for validating real-world performance [7]. |

Experimental Workflow for Real-Time BCI

Electroencephalography (EEG)-based brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) hold immense potential for enabling dexterous control of prosthetic hands at the individual finger level. Such fine-grained control would dramatically improve the quality of life for individuals with neuromuscular disorders or upper limb impairments by restoring their ability to perform activities of daily living. However, achieving this goal presents significant challenges due to the fundamental limitations of non-invasive neural recording technologies. The primary obstacles lie in the limited spatial resolution of scalp EEG and the substantial overlap in neural representations of individual fingers within the sensorimotor cortex [4]. This application note examines these challenges in detail, summarizes current decoding methodologies and their performance, and provides detailed experimental protocols for researchers working in real-time EEG classification for prosthetic control.

Neural Correlates of Finger Movements

Movement-Related Spectral Changes

During finger movements, characteristic changes occur in specific frequency bands of the EEG signal. Research has consistently identified two prominent phenomena:

- Event-Related Desynchronization (ERD): A decrease in power in the alpha (8-13 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) bands over contralateral central brain regions during movement execution [20]. This desynchronization reflects cortical activation during motor planning and execution.

- Event-Related Synchronization (ERS): A post-movement power increase, particularly prominent in the beta band ("beta rebound"), believed to reflect cortical inhibition or deactivation following movement termination [20].

These spectral changes provide critical features for distinguishing movement states (movement vs. rest) but offer more limited discrimination between movements of different individual fingers due to overlapping cortical representations.

Movement-Related Cortical Potentials (MRCPs)

MRCPs are low-frequency (0.3-3 Hz) voltage shifts observable in the EEG time domain [20]. Key components include:

- Bereitschaftspotential (Readiness Potential): A slow negative deflection beginning up to 2 seconds before movement onset, with early bilateral distribution shifting to contralateral predominance approximately 500ms before movement.

- Reafferent Potential: A positive deflection following movement execution, related to sensory feedback processing.

MRCPs have shown particular value in finger movement decoding, with some studies suggesting that low-frequency time-domain amplitude provides better differentiation between finger movements compared to spectral features [20].

Table 1: Neural Correlates of Finger Movements and Their Characteristics

| Neural Correlate | Frequency Range | Temporal Characteristics | Spatial Distribution | Primary Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERD | Alpha (8-13 Hz) & Beta (13-30 Hz) | Begins prior to movement onset; persists during movement | Contralateral central regions | Cortical activation during motor planning & execution |

| ERS | Beta (13-30 Hz) | Prominent after movement termination | Contralateral central regions | Cortical inhibition or deactivation post-movement |

| MRCP | 0.3-3 Hz | Begins 1.5-2s before movement; evolves through movement | Bilateral early, contralateral later | Motor preparation, execution, & sensory processing |

Technical Challenges in Finger-Level Decoding

Spatial Resolution Limitations

The human sensorimotor cortex contains finely organized representations of individual fingers, but these representations are small and highly overlapping [4]. The fundamental challenge for EEG arises from several factors:

- Volume Conduction: As electrical signals travel from the cortex through cerebrospinal fluid, skull, and scalp, they undergo significant spatial blurring [4] [21]. This effect substantially reduces EEG's ability to distinguish adjacent finger representations.

- Electrode Density Limitations: Conventional EEG systems following the 10-20 international system have inter-electrode distances of 60-65mm on average [21], which is insufficient to capture the fine-grained spatial patterns of finger movements. While high-density systems (128-256 channels) improve spatial sampling, they still face fundamental physiological limitations.

Signal Overlap in the Sensorimotor Cortex

Neuroimaging studies have shown that each digit shares overlapping cortical representations in the primary motor cortex [20]. This organization presents a fundamental challenge for decoding individual finger movements:

- The thumb often exhibits the most distinct EEG response, making it more decodable than other fingers [20].

- Neighboring fingers (particularly index and middle fingers) show the highest classification confusion due to their adjacent cortical representations and extensive functional coupling during natural movements.

- This overlap results in a performance ceiling for finger classification, with 4-finger classification achieving only ~46% accuracy for motor imagery tasks [4].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Finger Decoding Approaches

| Study | Classification Type | Fingers Classified | Paradigm | Accuracy | Key Features Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ding et al. (2025) [4] | 2-finger | Thumb vs Pinky | Motor Imagery | 80.56% | Deep Learning (EEGNet), broadband (4-40 Hz) |

| Ding et al. (2025) [4] | 3-finger | Thumb, Index, Pinky | Motor Imagery | 60.61% | Deep Learning (EEGNet), broadband (4-40 Hz) |

| Ding et al. (2025) [4] | 4-finger | Multiple fingers | Motor Imagery | 46.22% | Deep Learning (EEGNet), broadband (4-40 Hz) |

| Sun et al. (2024) [20] | Pairwise | Thumb vs Others | Movement Execution | >60% | Low-frequency amplitude, MRCP, ERD/S |

| Lee et al. (2022) [21] | Pairwise | Middle vs Ring | Movement Execution | 70.6% | uHD EEG, mu/band power |

| Liao et al. (2014) [cited in 7] | Finger pairs | Multiple pairs | Movement Execution | 77% | Broadband features |

Experimental Protocols for Finger Movement Decoding

Basic Experimental Setup for Finger Movement Studies

Participant Preparation and Equipment

- Participants: Recruit right-handed healthy adults (sample size: 10-21 participants based on study design). For clinical applications, include participants with upper limb impairments [4] [22].

- EEG System: Use high-density EEG systems (≥58 channels) covering frontal, central, and parietal areas [20]. Ground electrode at AFz, reference at FCz [20].

- Impedance Control: Maintain electrode impedance below 5 kΩ [20] to ensure signal quality.

- Data Glove: Simultaneously record finger trajectories using digital data gloves (e.g., 5DT Ultra MRI) to validate movement execution and timing [20].

Experimental Paradigm

The flex-maintain-extend paradigm has been successfully used to study individual and coordinated finger movements [20]:

- Conditions: Include five individual fingers (Thumb, Index, Middle, Ring, Pinky) and coordinated gestures (Pinch, Point, ThumbsUp, Fist), plus rest condition.

- Trial Structure:

- Preparation period (2s): Blank screen, participants prepare for trial

- Fixation period (2s): Cross-hair display, resting state

- Cue period (2s): Visual instruction for specific finger movement

- Movement execution: Continuous flexion and extension of cued finger (typically twice per trial)

- Session Structure: 30 blocks per session, with adequate rest between trials to prevent fatigue.

Signal Acquisition and Processing Protocol

Data Acquisition Parameters

- Sampling Rate: 1000 Hz [20] or 256 Hz [22] depending on system capabilities

- Filtering: Online bandpass filtering 0.1-100 Hz, with notch filter at 50/60 Hz for line noise removal

- Recording Environment: Electrically shielded room or low-noise laboratory setting

Preprocessing Pipeline

- Bandpass Filtering: 4th order Butterworth bandpass filter (0.5-60 Hz) [22]

- Artifact Removal:

- Re-referencing: Common average reference or reference to linked mastoids

Feature Extraction and Classification Methods

Feature Extraction Techniques

Multiple feature domains have been explored for finger movement decoding:

Time-Domain Features:

Frequency-Domain Features:

Advanced Feature Selection:

Classification Approaches

Traditional Machine Learning:

Deep Learning Architectures:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Equipment and Software for EEG Finger Decoding Research

| Category | Specific Product/Model | Key Specifications | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| EEG Systems | Neuroscan SynAmps RT [20] | 58+ channels, 1000 Hz sampling | High-quality data acquisition for movement studies |

| g.tec GAMMAcap [22] | 32 channels, 256 Hz sampling | Prosthetic control applications | |

| g.Pangolin uHD EEG [21] | 256 channels, 8.6mm inter-electrode distance | Ultra-high-density mapping | |

| Data Gloves | 5DT Ultra MRI [20] | 5-sensor configuration | Synchronized finger trajectory recording |

| Software Platforms | BCI2000 [22] | Open-source platform | Experimental control and data acquisition |

| EEGLab/MATLAB | ICA analysis toolbox | Data preprocessing and artifact removal | |

| Classification Tools | EEGNet [4] | Compact convolutional neural network | Deep learning-based decoding |

| SVM with Bayesian Optimizer [22] | Statistical learning model | Traditional machine learning approach | |

| Experimental Control | Psychtoolbox-3 [20] | MATLAB/Python toolbox | Visual stimulus presentation and synchronization |

The challenge of finger-level decoding from EEG signals remains substantial due to the fundamental limitations of spatial resolution and overlapping neural representations. However, recent advances in high-density EEG systems, sophisticated feature extraction methods, and deep learning approaches have progressively improved decoding performance. The integration of multiple feature types—particularly combining low-frequency time-domain features with spectral power changes—shows promise for enhancing classification accuracy. While current systems have achieved reasonable performance for 2-3 finger classification, significant work remains to achieve the dexterity of natural hand function. Future research directions should focus on hybrid approaches combining EEG with other modalities, advanced signal processing techniques to mitigate spatial limitations, and longitudinal adaptation paradigms that leverage neural plasticity to improve performance over time.

Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) represent a revolutionary technology that establishes a direct communication pathway between the brain and external devices, bypassing the peripheral nervous system [25] [26]. For individuals with motor disabilities resulting from conditions such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), spinal cord injury, or stroke, BCI-controlled prosthetics offer the potential to restore lost functions and regain independence. The core principle involves measuring and decoding brain activity, then translating it into control commands for prosthetic limbs in real-time [27]. This application note details the complete pipeline, from signal acquisition to prosthetic actuation, with a specific focus on electroencephalography (EEG)-based systems for non-invasive prosthetic control, providing structured protocols and quantitative performance assessments for research implementation.

The fundamental pipeline operates through a closed-loop design: acquire neural signals, process and decode intended movements, execute commands on the prosthetic device, and provide sensory feedback to the user [27]. Non-invasive EEG-based systems offer greater accessibility compared to invasive methods, though they typically provide lower spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio [4]. Recent advances in deep learning and embedded computing have significantly enhanced the real-time decoding capabilities of EEG-based systems, making sophisticated prosthetic control increasingly feasible [4] [7].

The Complete BCI-Prosthetic Workflow

The entire process from brain signal acquisition to prosthetic movement involves multiple stages of sophisticated processing. The following diagram illustrates this complete integrated pipeline, highlighting the critical stages and data flow.

Figure 1: Complete BCI-Prosthetic Control Pipeline Showing the Closed-Loop System

Performance Comparison of BCI Control Modalities

Research demonstrates varying levels of performance across different BCI control paradigms and modalities. The table below summarizes key quantitative metrics from recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of BCI Control Modalities for Prosthetic Applications

| Control Paradigm | Signal Modality | Accuracy (%) | Information Transfer Rate (bits/min) | Latency | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Finger MI | EEG | 80.56 (2-finger)60.61 (3-finger) | Not Reported | Real-time | Robotic hand control [4] |

| Speech Decoding | Intracortical | 99 (word output) | ~56 WPM | <250 ms | Communication, computer control [28] |

| Hybrid sEMG+EEG | EEG+sEMG | Up to 99 (sEMG)76 (EEG) | Not Reported | 0.3s (grip) | Transhumeral prosthesis [18] |

| Core Actions (Left, Right, Idle) | EEG | Up to 90 | Not Reported | Low latency | 3-DoF prosthetic arm [7] |

| Sensorimotor Rhythms | EEG | Variable by subject | ~20-30 (typical) | Real-time | Cursor control, basic prosthesis [26] |

Table 2: BCI Signal Acquisition Modalities Comparison

| Modality | Invasiveness | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEG | Non-invasive | Low (~1-3 cm) | High (ms) | Safe, portable, low-cost | Low signal-to-noise ratio, sensitivity to artifacts [4] |

| ECoG | Partially-invasive (subdural) | High (~1 mm) | High (ms) | Better signal quality than EEG | Requires craniotomy [26] |

| Intracortical | Fully-invasive | Very high (~100 μm) | High (ms) | Highest signal quality | Surgical risk, tissue response [28] |

| Endovascular | Minimally-invasive | Moderate | High (ms) | No open brain surgery | Limited electrode placement [27] |

Experimental Protocol: EEG-Based Robotic Finger Control

Study Design and Participant Selection

This protocol is adapted from recent research demonstrating real-time non-invasive robotic control at the individual finger level using movement execution (ME) and motor imagery (MI) paradigms [4]. The study typically involves 21 able-bodied participants with prior BCI experience, though it can be adapted for clinical populations. Each participant completes one offline familiarization session followed by two online testing sessions for both ME and MI tasks. The offline session serves to train subject-specific decoding models, while online sessions validate real-time control performance with robotic feedback.

Equipment and Software Setup

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

| Item | Specification/Model | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| EEG Acquisition System | OpenBCI UltraCortex Mark IV | Multi-channel EEG signal acquisition [7] |

| Robotic Hand | Custom or commercial model | Physical feedback device for BCI control |

| Deep Learning Framework | TensorFlow/PyTorch | Implementation of EEGNet and other models |

| Signal Processing Library | BrainFlow | EEG data acquisition, denoising, and streaming [7] |

| Classification Model | EEGNet-8.2 | Spatial-temporal feature extraction and classification [4] |

Step-by-Step Experimental Procedure

The experimental workflow for implementing and validating an EEG-based prosthetic control system involves multiple precisely coordinated stages, as visualized below.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for BCI Prosthetic Validation

Participant Preparation and Setup: Fit EEG headset with appropriate electrode configuration. For the UltraCortex Mark IV, ensure proper positioning of electrodes over sensorimotor areas (C3, Cz, C4 according to 10-20 system). Apply conductive gel to achieve electrode-scalp impedance below 10 kΩ.

Offline Data Collection and Model Training:

- Present visual cues instructing participants to execute or imagine movements of specific fingers (thumb, index, pinky) in randomized order.

- Record EEG signals during task performance with precise timing markers.

- Extract trial epochs (e.g., 0-2s relative to cue onset) and preprocess signals (bandpass filtering 0.5-40 Hz, artifact removal).

- Train subject-specific EEGNet model using offline data with k-fold cross-validation.

Real-Time Testing with Feedback:

- Implement closed-loop BCI control where decoded finger commands drive robotic finger movements in real-time.

- Provide both visual feedback (on-screen finger color changes: green for correct, red for incorrect) and physical feedback (robotic finger movement).

- For the first 8 runs of each task, use the base model; for subsequent runs, employ a fine-tuned model adapted to same-day data [4].

Performance Assessment:

- Calculate majority voting accuracy as the percentage of trials where the predicted class matches the true class.

- Compute precision and recall for each finger class to assess classifier robustness.

- Perform statistical analysis (e.g., two-way repeated measures ANOVA) to evaluate performance improvements across sessions.

Advanced Implementation: Embedded System Integration

For practical prosthetic applications, implementing the BCI pipeline on embedded hardware is essential for portability and real-time operation. Recent research has demonstrated successful deployment on platforms like the NVIDIA Jetson Orin Nano [7]. The integration architecture for such embedded systems is detailed below.

Figure 3: Embedded System Architecture for Portable BCI Prosthetic Control

Embedded Implementation Protocol

Model Optimization for Edge Deployment:

- Perform evolutionary search to identify Pareto-optimal model configurations balancing accuracy and efficiency.

- Apply model compression techniques including pruning (up to 70%) and quantization to reduce computational demands while maintaining >90% accuracy [7].

- Optimize window sizes for EEG segment analysis to minimize latency while preserving classification performance.

System Integration and Validation:

- Interface the optimized deep learning models with the prosthetic arm's control system through a dedicated API.

- Implement voice command integration for seamless mode switching between different grasp patterns and functionalities.

- Validate end-to-end system latency with targets below 300ms for real-time responsiveness.

The complete BCI pipeline for prosthetic applications represents a rapidly advancing field with significant potential to restore function and independence to individuals with motor impairments. The protocols outlined herein provide researchers with comprehensive methodologies for implementing and validating both laboratory and embedded BCI-prosthetic systems. As the field evolves, key areas for future development include enhancing the longevity and stability of chronic implants [28], improving non-invasive decoding resolution through advanced machine learning techniques [4], and developing more sophisticated sensory feedback systems to create truly bidirectional neural interfaces [28]. Standardization of performance metrics as discussed in [29] will further accelerate clinical translation and enable more effective comparison across studies and systems.

Implementing AI-Driven Decoders: Machine Learning Architectures for Real-Time Classification

The evolution of non-invasive brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) for prosthetic control represents a paradigm shift in neuroengineering, offering individuals with motor impairments the potential to regain dexterity through direct neural control. Electroencephalography (EEG)-based systems have emerged as particularly promising due to their safety and accessibility compared to invasive methods [4]. However, the accurate decoding of motor intent from EEG signals remains challenging due to the low signal-to-noise ratio and non-stationary nature of these signals [30] [31].

Within this research landscape, deep learning architectures have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in extracting spatiotemporal features from raw EEG data. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), particularly specialized variants like EEGNet, excel at identifying spatial patterns across electrode arrays and spectral features, while Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), including Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, effectively model temporal dependencies in brain activity [32] [33]. The integration of these architectures has produced hybrid models that achieve state-of-the-art performance in classifying Motor Imagery (MI) tasks, forming the computational foundation for next-generation prosthetic devices [4] [7].

This application note provides a comprehensive technical resource for researchers developing real-time EEG classification systems for prosthetic control. We present quantitative performance comparisons of dominant architectures, detailed experimental protocols for model implementation, and essential toolkits for practical system development.

Performance Analysis of Deep Learning Architectures

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Models on Major EEG Datasets

| Model Architecture | Dataset | Accuracy (%) | Key Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIACNet | BCI IV-2a | 85.15 | Dual-branch CNN, CBAM attention, TCN | [30] |

| BCI IV-2b | 90.05 | Dual-branch CNN, CBAM attention, TCN | [30] | |

| CNN-LSTM Hybrid | BCI Competition IV | 98.38 | Combined spatial and temporal feature extraction | [33] |

| CNN-LSTM Hybrid | PhysioNet EEG | 96.06 | Synergistic combination of CNN and LSTM | [32] |

| AMEEGNet | BCI IV-2a | 81.17 | Multi-scale EEGNet, ECA attention | [31] |

| BCI IV-2b | 89.83 | Multi-scale EEGNet, ECA attention | [31] | |

| HGD | 95.49 | Multi-scale EEGNet, ECA attention | [31] | |

| EEGNet with Fine-tuning | Individual Finger ME/MI | 80.56 (binary) 60.61 (ternary) | Transfer learning, real-time robotic feedback | [4] |

| CognitiveArm (Embedded) | Custom EEG Dataset | ~90 (3-class) | Optimized for edge deployment, voice integration | [7] |

The performance metrics in Table 1 demonstrate the effectiveness of hybrid and specialized architectures across diverse experimental paradigms. The CNN-LSTM hybrid model achieves exceptional accuracy (98.38%) on the Berlin BCI Dataset 1 by leveraging the spatial feature extraction capabilities of CNNs with the temporal modeling strengths of LSTMs [33]. Similarly, another CNN-LSTM hybrid reached 96.06% accuracy on the PhysioNet Motor Movement/Imagery Dataset, significantly outperforming traditional machine learning classifiers like Random Forest (91%) and individual deep learning models [32].

Attention mechanisms have emerged as powerful enhancements to base architectures. The CIACNet model incorporates an improved Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) to enhance feature extraction across both channel and spatial domains, achieving 85.15% accuracy on the BCI IV-2a dataset [30]. The AMEEGNet architecture employs Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) in a multi-scale EEGNet framework, achieving 95.49% accuracy on the High Gamma Dataset (HGD) while maintaining a lightweight design suitable for potential real-time applications [31].

For real-world prosthetic control, researchers have demonstrated that EEGNet with fine-tuning can decode individual finger movements with 80.56% accuracy for binary classification and 60.61% for ternary classification, enabling real-time robotic hand control at an unprecedented granular level [4]. The CognitiveArm system further advances practical implementation by achieving approximately 90% accuracy for 3-class classification on embedded hardware, highlighting the feasibility of real-time, low-latency prosthetic control [7].

Experimental Protocols for Real-Time EEG Classification

Protocol 1: Hybrid CNN-LSTM Model Development

Objective: Develop a hybrid CNN-LSTM model for high-accuracy classification of motor imagery EEG signals.

Workflow Diagram:

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Utilize standard EEG recording systems with appropriate electrode configurations based on the international 10-20 system. For motor imagery tasks, focus on electrodes covering sensorimotor areas (C3, Cz, C4) [31].

- Preprocessing: Apply band-pass filtering (e.g., 4-40 Hz) to isolate mu (8-12 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) rhythms associated with motor imagery. Implement artifact removal techniques such as Independent Component Analysis (ICA) to eliminate ocular and muscle artifacts [32].

- Data Augmentation: Employ synthetic data generation using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to increase dataset size and improve model generalization. This addresses the common challenge of limited EEG training data [32].

- Spatial Feature Extraction: Implement CNN layers with multiple filter sizes to extract multi-scale spatial features from EEG channels. Use depthwise and separable convolutions to maintain parameter efficiency as in EEGNet [30] [31].

- Temporal Modeling: Process CNN output features through bidirectional LSTM layers to capture long-range temporal dependencies in EEG sequences. This enables the model to learn both preceding and subsequent context for each time point [32] [33].

- Classification: Implement a fully connected layer with softmax activation to generate final predictions for motor imagery classes (e.g., left hand, right hand, feet, tongue).

Validation: Perform subject-dependent and subject-independent evaluations using k-fold cross-validation. For real-time systems, assess latency requirements with end-to-end processing time under 300ms for responsive control [7].

Protocol 2: Embedded Deployment for Real-Time Prosthetic Control

Objective: Implement and optimize EEG classification models for deployment on resource-constrained embedded systems.

Workflow Diagram:

Methodology:

- Design Space Exploration: Use evolutionary search algorithms to identify Pareto-optimal model configurations balancing accuracy and efficiency. Systematically evaluate hyperparameters, optimizer selection, and input window sizes [7].

- Model Compression:

- Apply pruning techniques to remove redundant weights (e.g., achieving 70% sparsity without significant accuracy loss)

- Implement quantization to reduce precision from 32-bit floating point to 8-bit integers

- These techniques reduce computational load and memory requirements for edge deployment [7]

- Hardware-Software Co-Design: Select appropriate embedded AI platforms (e.g., NVIDIA Jetson series) considering power consumption, computational capability, and I/O requirements. Optimize inference engines using TensorRT or similar frameworks [7].

- Real-Time BCI Integration: Implement the optimized model within a closed-loop BCI system such as CognitiveArm, which integrates BrainFlow for EEG data acquisition and streaming. Ensure end-to-end latency of <300ms for responsive prosthetic control [7].

- Multi-Modal Control: Incorporate complementary control modalities such as voice commands for mode switching, enabling users to seamlessly transition between different grasp types or operational modes [7].

Validation: Conduct real-time performance profiling to monitor memory usage, inference latency, and power consumption. Execute functional validation with able-bodied participants performing motor imagery tasks with simultaneous prosthetic actuation feedback [4] [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for EEG-based Prosthetic Control Research

| Category | Specific Resource | Function/Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| EEG Hardware | OpenBCI UltraCortex Mark IV | Non-invasive EEG signal acquisition with open-source platform | CognitiveArm system interface [7] |

| Delsys Trigno System | High-fidelity sEMG/EEG recording with integrated IMU | Motion tracking reference [34] | |

| Software Libraries | BrainFlow | Cross-platform library for EEG data acquisition and streaming | Real-time data pipeline in CognitiveArm [7] |

| EEGNet | Compact CNN architecture optimized for EEG classification | Baseline model in AMEEGNet [30] [31] | |

| Model Architectures | CIACNet | Dual-branch CNN with attention for MI-EEG | Achieving 85.15% on BCI IV-2a [30] |

| CNN-LSTM Hybrid | Combined spatial-temporal feature extraction | 96.06-98.38% accuracy on benchmark datasets [32] [33] | |

| Experimental Paradigms | BCI Competition IV 2a/2b | Standardized datasets for method comparison | Benchmarking AMEEGNet performance [31] |

| Individual Finger ME/MI | Fine-grained motor decoding paradigm | Real-time robotic finger control [4] | |

| Deployment Tools | TensorRT, TensorFlow Lite | Model optimization for edge deployment | Embedded implementation in CognitiveArm [7] |

The integration of convolutional and recurrent architectures represents a significant advancement in real-time EEG classification for prosthetic control. CNN-based models like EEGNet and its variants effectively capture spatial-spectral features, while LSTM networks model temporal dynamics critical for interpreting movement intention. Hybrid architectures that combine these strengths have demonstrated exceptional classification accuracy exceeding 96% on benchmark datasets.

Future research directions should focus on enhancing model interpretability, improving cross-subject generalization through transfer learning, and developing more efficient architectures for resource-constrained embedded deployment. The successful demonstration of individual finger control using noninvasive EEG signals [4] and the development of fully integrated systems like CognitiveArm [7] highlight the transformative potential of these technologies in creating intuitive, responsive prosthetic devices that can significantly improve quality of life for individuals with motor impairments.

The evolution of brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) for prosthetic control demands robust feature extraction methods that can translate raw electroencephalogram (EEG) signals into reliable control commands. Effective feature extraction is paramount for differentiating subtle neural patterns associated with motor imagery and intention, directly impacting the classification accuracy and real-time performance of prosthetic devices. This Application Note details three pivotal feature extraction methodologies—Wavelet Transform, Time-Domain analysis, and novel Synergistic Features—providing structured protocols and comparative data to guide researchers in developing advanced EEG-based prosthetic systems. By moving beyond raw data analysis, these methods enhance the signal-to-noise ratio, reduce data dimensionality, and capture the underlying neurophysiological phenomena essential for dexterous prosthetic control.

Feature Extraction Methods: Principles and Applications

Wavelet Transform

Wavelet Transform provides a powerful time-frequency representation of non-stationary EEG signals by decomposing them into constituent frequency bands at different temporal resolutions. Unlike Fourier-based methods, it overcomes the Heisenberg uncertainty principle limitation, allowing for simultaneous high temporal and frequency resolution, which is crucial for capturing transient motor imagery events like event-related desynchronization/synchronization (ERD/ERS) [35].

The Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) is commonly applied, using a cascade of high-pass and low-pass filters to decompose a signal into approximation (low-frequency) and detail (high-frequency) coefficients. For EEG, this breaks down the signal into sub-bands corresponding to standard physiological rhythms (e.g., Delta, Theta, Alpha, Beta, Gamma) [35]. Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD), another adaptive technique, decomposes signals into Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) suitable for nonlinear, non-stationary data analysis [35]. Recent advancements like Wavelet-Packet Decomposition (WPD) and Flexible Analytic Wavelet Transform (FAWT) offer more nuanced frequency binning and improved feature localization, proving highly effective for EMG and EEG signal classification [36] [37].

Time-Domain Features

Time-domain features are computationally efficient metrics calculated directly from the raw signal amplitude over time, making them ideal for real-time BCI systems. These features provide information on the signal's amplitude, variability, and complexity without requiring transformation to another domain. Key time-domain features include:

- Mean Absolute Value (MAV): Represents the average absolute value of the signal, indicating the level of electrical activity [38].

- Variance (Var): Measures the signal's variability or power [38].

- Zero Crossings (ZC): Counts the number of times the signal crosses zero, reflecting signal frequency content [38].

- Waveform Length (WL): The cumulative length of the signal waveform, providing information on waveform complexity [37].

These features are often used in combination to form a feature vector that characterizes the signal for subsequent classification.

Synergistic Features

Synergistic features represent a paradigm shift by moving beyond single-signal analysis to exploit the coordinated patterns between different physiological signals or brain regions. This approach is grounded in the concept of "brain synergy," where coordinated temporal patterns within the brain network contain valuable information for decoding movement intention [22].

In practice, synergy can be extracted through:

- Inter-channel Coordination: Analyzing coherence and power spectral density (PSD) patterns across multiple EEG channels covering frontal, central, and parietal regions [22].

- Multimodal Data Fusion: Integrating EEG with other signals like electromyography (EMG) to create a hybrid control system that compensates for the limitations of individual modalities [39].

- Network Dynamics: Employing independent component analysis (ICA) to identify synergistic spatial distribution patterns that decode complex hand movements with high accuracy [22].

Performance Comparison of Feature Extraction Methods

Table 1: Classification Performance of Different Feature Extraction Methods for EEG Signals

| Feature Method | Specific Technique | Application Context | Classifier Used | Accuracy (%) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelet Transform | DWT + EMD + Approximate Entropy | Motor Imagery (MI) EEG | SVM | High (Specific values not directly comparable across datasets) | Solves wide frequency band coverage during EMD; Improved time-frequency resolution [35] |

| Wavelet Transform | Wavelet-Packet Energy Entropy | MI-EEG Channel Selection | Multi-branch CNN-Transformer | 86.64%-86.81% | Quantifies spectral-energy complexity & class-separability; Enables significant channel reduction (27%) [36] |

| Time-Domain | Statistical Features (Mean, Variance, etc.) | EEG-based Emotion Recognition | SVM | 77.60%-78.96% | Efficiently discriminates emotional states; Low computational load [40] |

| Time-Domain | MAV, Variance, ZC | Hybrid EEG-EMG Prosthetic Control | LDA | >85% (for combined schemes) | Low computational cost; Proven effectiveness for real-time control [38] |

| Synergistic Features | Coherence of Spatial Power & PSD | Hand Movement Decoding (Grasp/Open) | Bayesian SVM | 94.39% | Captures valuable brain network coordination information [22] |

| Synergistic Features | EEG-Augmented EMG with Channel Attention | Rehabilitation Wheelchair Control | WCA-HTT Model | 97.5% | Integrates brain-muscle signals; Highlights most salient components [39] |

| Entropy-Based | SVD Entropy | Alzheimer's vs. FTD Discrimination | KNN | 91%-93% | Effective for neurodegenerative disease biomarker identification [41] |

Table 2: Computational Characteristics and Implementation Context

| Feature Method | Computational Load | Real-Time Suitability | Best-Suited Applications | Primary Physiological Basis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelet Transform | Moderate to High | Yes (with optimization) | Motor Imagery, Seizure Detection, Emotion Recognition | Time-Frequency Analysis of ERD/ERS |

| Time-Domain Features | Low | Excellent | Real-time Prosthetic Control, Basic Movement Classification | Signal Amplitude, Frequency, and Complexity |

| Synergistic Features | High | Emerging | Complex Hand Movement Decoding, Hybrid BCI Systems | Brain Network Coordination & Multimodal Integration |

| Entropy-Based Features | Moderate | Yes | Neurological Disorder Diagnosis, Signal Complexity Assessment | Signal Irregularity and Predictability |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: DWT- and EMD-Based Feature Extraction for Motor Imagery EEG

This protocol outlines the hybrid DWT-EMD method for extracting features from motor imagery EEG signals to improve classification accuracy [35].