Portable Low-Field MRI: Democratizing Clinical Neuroscience and Drug Development

Portable low-field magnetic resonance imaging (LF-MRI) is re-emerging as a transformative technology for clinical neuroscience and therapeutic development.

Portable Low-Field MRI: Democratizing Clinical Neuroscience and Drug Development

Abstract

Portable low-field magnetic resonance imaging (LF-MRI) is re-emerging as a transformative technology for clinical neuroscience and therapeutic development. Once limited by lower signal-to-noise ratio, modern LF-MRI systems now integrate advanced hardware design, artificial intelligence-based reconstruction, and refined pulse sequences to deliver clinically viable imaging. This article explores the foundational principles, methodological applications, and optimization strategies for LF-MRI, highlighting its potential to expand neuroimaging access into point-of-care, intensive care, and resource-limited settings. We validate its diagnostic performance against conventional high-field MRI and CT, examining its specific utility for conditions like hydrocephalus, stroke, and neurodegenerative diseases. For researchers and drug development professionals, LF-MRI offers a platform for decentralized clinical trials, longitudinal monitoring, and inclusion of underrepresented populations, ultimately promising to democratize neuroscience research and accelerate therapeutic innovation.

The Resurgence of Low-Field MRI: Principles and Drivers

Portable low-field Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) represents a paradigm shift in medical imaging, moving away from fixed, high-power installations towards accessible, point-of-care diagnostic tools. Within the context of clinical neuroscience research, these systems are redefining the boundaries of where and how brain imaging can be conducted. Portable low-field MRI is broadly defined as MRI technology operating at field strengths below 1.5 Tesla that features physical portability, reduced infrastructure requirements, and significantly lower operational costs compared to conventional high-field systems [1]. The "low-field" designation historically indicated inferior image quality, but modern implementations integrate advanced reconstruction algorithms, refined imaging techniques, and improved hardware design to significantly narrow this performance gap [1].

For neuroscience researchers and drug development professionals, these systems offer unprecedented opportunities to conduct longitudinal studies, monitor therapeutic efficacy in real-time, and expand research into non-traditional settings. The technological evolution of low-field MRI challenges the long-held notion that high field strength is prerequisite for diagnostic utility, instead emphasizing optimized hardware and software integration to deliver clinically relevant image quality [1]. This guide establishes the technical foundations, classifications, and methodological frameworks essential for leveraging portable low-field MRI in neuroscience research applications, with particular focus on field strength parameters that define system capabilities and limitations.

Technical Specifications and Field Strength Classification

The classification of portable low-field MRI systems is primarily governed by their static magnetic field strength (B₀), measured in Tesla (T), which serves as the fundamental determinant of their operational characteristics and potential applications. Field strength directly influences key imaging parameters including signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), contrast mechanisms, and hardware requirements [1]. The historical progression of MRI technology toward higher field strengths was largely driven by the pursuit of greater SNR and spatial resolution; however, contemporary low-field systems demonstrate that field strength is not the sole determinant of image quality, with advanced hardware and computational approaches effectively compensating for lower inherent signal [1].

Table 1: Field Strength Classification of Portable Low-Field MRI Systems

| Classification | Field Strength Range | Representative Systems | Primary Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Low-Field (ULF) | < 0.1 T (e.g., 46-64 mT) | Hyperfine Swoop (0.064 T) | Point-of-care neuroimaging, dementia screening, ARIA-E monitoring, ambulance transport studies [1] [2] [3] |

| Very-Low-Field (VLF) | 0.1 T - 0.5 T | Custom research systems (e.g., 50 mT) | Intraoperative imaging, continuous brain monitoring, technical development studies [4] |

| Mid-Low-Field | 0.5 T - 1.5 T | Siemens MAGNETOM Free.Max (0.55 T) | Musculoskeletal imaging, abdominal imaging, functional MRI feasibility studies [1] [4] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Characteristics Across Field Strengths

| Parameter | Ultra-Low-Field (64 mT) | Mid-Low-Field (0.55 T) | Conventional High-Field (1.5 T) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approximate Cost | Up to 50-60% less than 1.5T [1] | 40-50% of 1.5T system cost [1] | Reference (>$1M per Tesla) [1] |

| Installation Cost Reduction | Up to 70% (no shielding, no reinforced flooring) [1] | Significant savings | Reference |

| Maintenance Cost Reduction | Up to 45% (no cryogenics) [1] | Moderate savings | Reference |

| Typical Spatial Resolution | Limited (e.g., 1.6-5 mm slice thickness) [2] | Moderate to High | High (<1 mm isotropic) |

| Key Advantages | Portability, safety near metals, lower acoustic noise, patient comfort [1] | Balance of performance and accessibility, reduced artifacts [1] | Gold standard for image quality and resolution |

The operational advantages of portable low-field systems extend beyond field strength specifications to encompass practical implementation benefits. These systems typically utilize compact superconducting magnets (e.g., Siemens MAGNETOM Free.Max) or high-performance permanent magnets (e.g., Hyperfine Swoop) that eliminate requirements for cryogenic cooling and substantially reduce electricity consumption [1]. This magnet technology, combined with optimized radiofrequency (RF) coil designs that minimize resistance and thermal noise, enables diagnostic-quality imaging in diverse environments from intensive care units to mobile research vehicles [1]. For neuroscience research, this facilitates study designs previously considered impractical, including home-based imaging, monitoring during therapeutic interventions, and rapid serial assessment of disease progression.

Key Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Brain Morphometry Analysis Using Ultra-Low-Field MRI

The validation of portable low-field MRI for quantitative neuroimaging requires rigorous methodological frameworks to ensure research-grade data quality. Hsu et al. developed an optimized protocol specifically for brain volume analysis using ultra-low-field (ULF) MRI, achieving reliable morphometric measurements with a scan time of approximately 15 minutes [4]. This protocol employs deep learning enhancement methods trained on the optimized acquisition to improve the accuracy and reliability of subsequent volumetric analyses.

Methodology Details:

- Data Acquisition: The protocol utilizes T1-weighted and T2-weighted sequences optimized for ULF systems. Specific parameters are tailored to maximize contrast-to-noise ratio within time constraints.

- Image Enhancement: A dedicated deep learning framework processes acquired ULF images to enhance quality and resolution before morphometric analysis.

- Validation Approach: Processed images are segmented into 33 distinct brain regions using automated parcellation tools. The volumetric measurements from ULF data are statistically compared against reference measurements obtained from high-field (3T) MRI scans to assess concordance.

- Quality Control: The protocol incorporates bootstrapping methods to propagate segmentation uncertainties, providing confidence intervals for volumetric estimates rather than single-point measurements [4].

This methodology demonstrates that with optimized acquisition and computational enhancement, ULF MRI can yield brain morphometric measurements that correlate strongly with high-field references, enabling longitudinal tracking of brain volume changes in clinical research settings where traditional MRI is impractical.

Protocol for Contrast-Enhanced Tumor Imaging

The application of contrast-enhanced imaging in portable low-field MRI systems addresses a critical need in neuro-oncology research, particularly for monitoring treatment response. Altaf et al. established the first documented protocol for post-contrast enhancement in a portable ultra-low-field (pULF) MRI system for brain tumor imaging [2]. This protocol successfully identified tumor presence that was subsequently confirmed histologically, validating the clinical relevance of the methodology.

Methodology Details:

- Patient Preparation: Standard gadolinium-based contrast agent (0.10 mmol/kg) administered intravenously.

- Imaging Sequences: The comprehensive protocol includes T2 Axial, T2 sagittal, T2-weighted FLAIR (TR: 4,000 ms, TE: 166.72 ms), T1 Axial, and DWI + ADC sequences (TR: 1,000 ms, TE: 76.04 ms).

- Spatial Resolution: For T1 and T2 sequences, pixel spacing of 1.6 mm with slice thickness of 5 mm; for DWI and ADC sequences, pixel spacing of 2.4 mm with slice thickness of 5.88 mm.

- Timing: Total scan time of 31 minutes for post-contrast imaging, with a 15-minute interval between high-field and pULF-MRI scanning to account for patient and equipment positioning.

- Validation: Comparative assessment with high-field (1.5T) MRI confirmed lesion detection, though with noted reductions in contrast-to-noise ratio and lesion conspicuity compared to standard MRI [2].

This protocol demonstrates that despite technical challenges, contrast-enhanced neuroimaging is feasible with pULF-MRI systems, potentially enabling brain tumor monitoring in resource-limited research settings where conventional MRI is unavailable.

Protocol for ARIA-E Detection in Alzheimer's Therapy Monitoring

The CARE PMR study established a specialized protocol for detecting Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities with Edema (ARIA-E) in patients receiving amyloid-targeting therapies for Alzheimer's disease [3]. This application highlights the particular value of portable MRI for frequent monitoring requirements in clinical trials.

Methodology Details:

- Study Design: Multi-site prospective trial assessing clinical utility and workflow benefits of portable MRI for ARIA detection.

- Imaging Protocol: Standardized acquisition protocol optimized for edema detection on ultra-low-field system.

- Analysis Method: Images interpreted by trained physicians with comparison to high-field MRI reference standard.

- Performance Metrics: Demonstrated 100% sensitivity for detecting mild to moderate ARIA-E, supporting use as triage tool despite some cases still requiring high-field MRI for comprehensive evaluation [3].

This protocol validates portable low-field MRI as an effective screening tool for treatment-related adverse events, facilitating the practical implementation of appropriate monitoring guidelines for novel Alzheimer's therapies in both clinical and research settings.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methods and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Portable Low-Field MRI Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Gadolinium Chelates | Contrast enhancement for lesion characterization | 0.10 mmol/kg for tumor imaging at 64 mT; effective across field strengths from 0.15 T to 1.5 T [2] |

| Deep Learning Models (LoHiResGAN) | Image quality enhancement through low-to-high-field translation | Improves SNR and spatial resolution; enables automated brain morphometry on ULF data [5] |

| Segmentation Algorithms (SynthSeg+) | Automated volumetric brain analysis | Provides robust segmentation across various MRI resolutions and contrasts; enables quantitative studies [5] |

| Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Particles | Alternative contrast mechanism | "Negative enhancers" with strong susceptibility effects; potential for cellular tracking in neuroscience research [2] |

| Macromolecular Gd-based Agents | Advanced contrast for angiogenesis imaging | Molecular weight range 64-17,500 d; investigational for tumor characterization [2] |

The research toolkit for portable low-field MRI extends beyond traditional contrast agents to encompass computational resources that are equally critical for generating research-grade data. Deep learning models specifically address the inherent signal-to-noise limitations of low-field systems through image-to-image translation techniques that synthesize high-field-like images from low-field acquisitions [5]. The LoHiResGAN architecture, which incorporates ResNet components and structural similarity index measure (SSIM) loss functions, has demonstrated superior performance in generating synthetic high-field images that preserve essential morphological information while significantly improving quantitative measurement consistency across diverse brain regions [5]. These computational tools, combined with robust segmentation algorithms like SynthSeg+ that maintain performance across varying image contrasts and resolutions, form an essential component of the modern low-field MRI research pipeline [5].

Emerging Applications in Clinical Neuroscience Research

Portable low-field MRI systems are enabling novel research paradigms across multiple neuroscience domains by removing traditional barriers to MRI access. In neurodegenerative disease research, these systems are being deployed for dementia screening in outpatient clinics and for monitoring treatment safety in Alzheimer's clinical trials [6] [3]. The ACE-AD study at the University of Kansas Alzheimer's Disease Research Center exemplifies this approach, combining portable MRI with cognitive testing and blood biomarkers in a single nurse-led clinic visit to expedite diagnosis and improve accessibility for rural and underserved populations [6].

In neuro-oncology research, portable systems demonstrate feasibility for both diagnostic applications and treatment monitoring. The documented case of contrast-enhanced tumor imaging at 0.064 T establishes a foundation for future studies investigating tumor progression and treatment response in settings where conventional MRI is unavailable [2]. Additionally, technical innovations presented at the 2025 ISMRM conference highlight emerging capabilities including functional MRI at 0.55 T, which demonstrates feasibility despite traditionally being considered a high-field application [4]. This expansion of functional imaging to low-field systems could potentially enable task-based fMRI studies in naturalistic environments beyond the scanner room, opening new avenues for cognitive neuroscience investigation.

The methodological frameworks and technical specifications detailed in this guide provide neuroscience researchers with the foundational knowledge required to strategically implement portable low-field MRI across diverse research scenarios. As the technology continues to evolve through hardware refinements and computational advances, these systems are positioned to fundamentally transform the scope and accessibility of neuroimaging research, particularly for longitudinal studies, point-of-care applications, and research involving special populations where conventional MRI presents logistical challenges.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at low magnetic field strengths (conventionally defined as <0.5 T, and more recently encompassing systems down to 0.01 T) is experiencing a remarkable renaissance in clinical neuroscience research [1] [7]. This renewed interest challenges the long-held notion that high magnetic field strength is inherently superior, driven instead by the distinct advantages of portable, low-cost systems that can expand access to neuroimaging [8] [9]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the core physical principles of signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR), and relaxometry at low fields is paramount to leveraging this technology effectively. The fundamental trade-off in low-field MRI is the reduced signal strength, which must be balanced against benefits including reduced susceptibility artifacts near metallic hardware or air-tissue interfaces, lower specific absorption rate (SAR) enhancing patient safety, and significantly lower operational costs and infrastructure demands [1] [10]. These characteristics make low-field systems particularly valuable for point-of-care imaging, monitoring neurological conditions in intensive care settings, and conducting large-scale population studies in resource-limited environments, thereby addressing critical gaps in global healthcare accessibility [8] [11].

Fundamental Physics of Signal and Contrast at Low Field

Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) Fundamentals

The signal-to-noise ratio represents the most critical determinant of image quality in MRI, quantifying the strength of the desired signal relative to background noise. The fundamental challenge of low-field MRI lies in the physics of signal generation: the net magnetization vector (M0), which forms the basis of the MR signal, is directly proportional to the static magnetic field strength (B0) [1]. This relationship establishes a fundamental field strength dependency for the MR signal. However, the complete theoretical framework for SNR is more nuanced, incorporating both signal and noise contributions from the sample and radiofrequency (RF) coil.

The voltage induced in an RF receiver coil by the precessing magnetization is governed by Faraday's Law of Induction, which states that the induced electromotive force is proportional to the rate of change of magnetic flux. Since the precession frequency (Larmor frequency) increases linearly with B0, the overall MR signal exhibits a quadratic dependence on the static magnetic field (Signal ∝ B₀²) [10]. The noise in MRI systems originates primarily from Johnson-Nyquist noise in the conductive components of the receiver coil and the subject being imaged. In the low-field regime (typically below 0.1 T), where the noise from the sample is comparable to or less than the coil noise, the overall SNR demonstrates a dependence of approximately SNR ∝ B₀^(3/2) [10] [7]. At ultra-low fields (<0.01 T), where coil noise dominates, the relationship may approach SNR ∝ B₀ [7].

Table 1: SNR Dependence on Magnetic Field Strength Across Different Regimes

| Field Strength Regime | Theoretical SNR Dependence | Dominant Noise Source | Practical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultra-Low-Field (<0.01 T) | ∝ B₀ | Coil resistance | Maximum benefit from coil optimization; longest acquisition times |

| Very-Low-Field (0.01-0.1 T) | ∝ B₀^(3/2) | Mixed (Coil & Sample) | Balanced hardware/software optimization needed |

| Mid-Field (0.1-1 T) | ∝ B₀^(7/4) to ∝ B₀² | Sample dielectric losses | Closest performance to high-field; most clinical low-field systems |

Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR) and Relaxometry

While SNR measures overall signal quality, contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) defines the ability to distinguish between different tissue types. CNR is calculated as the difference in signal intensity between two tissues divided by the background noise [12]. At low field strengths, the longitudinal (T1) and transverse (T2) relaxation times of tissues exhibit distinct behavior that directly impacts image contrast.

T1 relaxation times demonstrate a strong field dependence, with values decreasing as field strength decreases [10]. This phenomenon occurs because the dominant relaxation mechanisms at lower fields are more efficient. For example, the T1 of gray matter decreases from approximately 1500 ms at 3 T to around 600 ms at 0.1 T [10]. This reduction has significant implications for sequence parameters: shorter repetition times (TR) can be used in T1-weighted sequences without saturating the signal, potentially reducing scan times.

In contrast, T2 and T2* relaxation times increase at lower field strengths due to reduced susceptibility effects and diminished influence of diffusion through intrinsic field inhomogeneities [10]. This T2 prolongation enhances signal in T2-weighted sequences and reduces artifacts near tissue-air interfaces or metallic implants, representing a key advantage for postoperative imaging and musculoskeletal applications [1].

Table 2: Field Dependence of Relaxation Parameters for Brain Tissues

| Tissue Type | Relaxation Parameter | Field Dependence Model | Approximate Value at 0.055 T |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gray Matter | T1 | T1(ms) = 1160 × (γB₀)^(0.376) [10] | ~650 ms |

| T2* | T2*(ms) = 90 × e^(-0.142×B₀) [10] | ~85 ms | |

| White Matter | T1 | T1(ms) = 710 × (γB₀)^(0.382) [10] | ~450 ms |

| T2* | T2*(ms) = 64 × e^(-0.132×B₀) [10] | ~62 ms | |

| Blood | T1 | T1(ms) = 3350 × (γB₀)^(0.340) [10] | ~1200 ms |

The field dependence of relaxation times means that the CNR efficiency (CNR per unit time) follows different optimization rules than at high field. T1-weighted CNR between gray and white matter is generally reduced at low field, while T2-weighted CNR may be preserved or even enhanced in certain scenarios [10]. Proton-density weighted imaging often provides excellent CNR at low fields due to the reduced T1 weighting and lower power requirements for RF pulses.

Figure 1: Fundamental Relationships Governing SNR and CNR at Low Magnetic Fields. The diagram illustrates how static magnetic field strength (B₀) influences signal generation, noise contributions, and relaxation parameters that collectively determine the resulting SNR and CNR in low-field MRI.

Technical Strategies for SNR Enhancement at Low Field

Hardware Optimization Approaches

Modern low-field MRI systems incorporate sophisticated hardware designs to mitigate the inherent SNR limitations. Permanent magnet technology has advanced significantly, with contemporary systems utilizing samarium-cobalt (SmCo) or neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) magnets offering improved temperature stability and field homogeneity [9] [11]. These magnets enable compact designs with weights ranging from 350-750 kg for brain-dedicated systems, making them truly portable [9] [11].

RF coil design is particularly critical at low field, where the reduced resonance frequency places the system in the quasi-static regime, altering the traditional noise contributions. Several innovative approaches have been implemented:

- Superconducting RF coils: Operating at high or low temperatures to minimize resistance and thermal noise, thereby improving SNR [1].

- Multimodal surface coils: Leveraging multiple resonant modes to increase RF field efficiency and enhance image quality [1].

- Optimized coil arrays: Multi-channel arrays designed specifically for the lower Larmor frequencies encountered at low field [13].

Gradient system performance has also seen substantial improvements, with modern low-field systems incorporating optimized gradient coils that provide sufficient strength and switching rates for clinical imaging while maintaining low acoustic noise and power consumption [11].

Software and Reconstruction Techniques

Advanced software solutions play a pivotal role in compensating for the reduced SNR at low field strengths, often leveraging developments originally made for high-field systems:

- Advanced k-space sampling: Non-Cartesian trajectories such as spiral and radial sampling provide more efficient k-space coverage and inherent motion robustness [13]. These approaches increase the sampling duty cycle (T_sampling in Equation 2), directly improving SNR efficiency.

- Parallel imaging and compressed sensing: These techniques enable accelerated acquisitions by undersampling k-space, allowing for either shorter scan times or increased averages within the same timeframe to boost SNR [13].

- Deep learning reconstruction: Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and other deep learning architectures can effectively denoise images, suppress artifacts, and even enhance resolution beyond the intrinsic acquisition limits [13] [11]. These methods can learn complex mappings from noisy low-field images to their cleaner high-field counterparts when trained on paired datasets.

- Electromagnetic interference (EMI) cancellation: Operating without RF shielding requires sophisticated EMI cancellation algorithms. Deep learning approaches have demonstrated remarkable success in predicting and removing dynamically changing EMI signals captured by strategically placed reference coils [9] [13].

Table 3: Software Solutions for SNR Enhancement in Low-Field MRI

| Technique Category | Specific Methods | Key Principle | Impact on SNR Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquisition Strategies | Radial/Spiral Trajectories | Efficient k-space coverage; oversampling center | Increases sampling duty cycle |

| Balanced Steady-State Free Precession (bSSFP) | Optimal signal for given TR | Maximizes signal per unit time | |

| Reconstruction Methods | Parallel Imaging (SENSE, GRAPPA) | k-space undersampling with multiple coils | Enables more averages in fixed time |

| Compressed Sensing | Leveraging image sparsity | Reduces required sampling | |

| Post-Processing | Deep Learning Denoising | Learned noise patterns from training data | Direct noise suppression |

| Super-Resolution Networks | Synthesizing high-frequency information | Enhanced apparent resolution | |

| EMI Cancellation | Adaptive Filtering | Reference-based interference modeling | Reduces structured noise |

Experimental Protocols for Low-Field MRI Research

SNR Quantification Methodology

Accurate quantification of SNR is essential for validating system performance and optimizing sequences. The recommended methodology involves:

- Dual-Acquisition Technique: Acquire two identical datasets with identical parameters and reconstruct them separately [12]. This approach provides the most reliable SNR measurement in clinical imaging scenarios.

- Region of Interest (ROI) Analysis: Place uniform ROIs in background air and in homogeneous tissue regions (e.g., central white matter).

- SNR Calculation: Calculate SNR as SNR = Stissue / σbackground, where Stissue is the mean signal intensity in tissue and σbackground is the standard deviation in background noise [12].

- Correlation Analysis: For enhanced precision, use the correlation function of two independent acquisitions to quantify SNR, which provides robustness against structured noise [12].

For systems with array coils, combine ROIs from multiple elements to ensure comprehensive noise characterization. When employing parallel imaging, account for the spatially varying noise amplification (g-factor) in SNR calculations.

Protocol Optimization for Neuroscience Applications

Implementing clinical neuroimaging protocols at low field requires careful parameter adjustment to account for the altered relaxation times and contrast mechanisms:

- T1-Weighted Imaging: Utilize the shorter T1 values to reduce TR and increase slice coverage within a given time. While T1-weighted CNR is generally reduced at low field, optimized protocols can still provide diagnostically useful images [14] [11].

- T2-Weighted Imaging: Leverage the prolonged T2 times to employ longer echo times (TE) while maintaining signal. T2-weighted images often provide superior CNR compared to T1-weighted images at low field [14].

- Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR): Adjust inversion times (TI) based on the field-dependent T1 values of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and brain tissue. FLAIR-like imaging has been successfully implemented at 0.055 T for detecting pathologies like white matter lesions [9].

- Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI): The reduced T2 weighting at low field can be advantageous for DWI, allowing for stronger diffusion weighting. Isotropic DWI has been demonstrated at 0.055 T for stroke detection [9].

For volumetric analysis in neuroscience research, the "TomoBrain" approach has shown promise, combining orthogonal imaging directions (axial, coronal, and sagittal) for T2-weighted images to form higher resolution image volumes suitable for automated segmentation of gray matter, white matter, and hippocampal volumes [14].

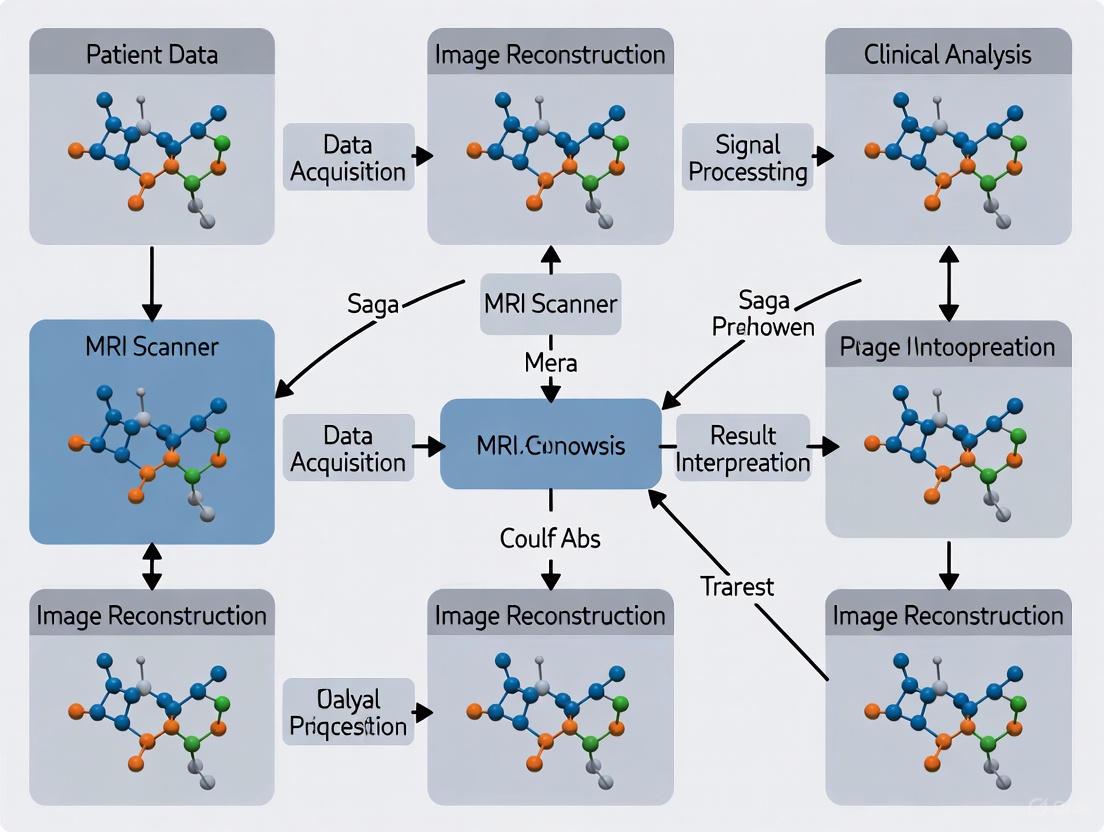

Figure 2: Comprehensive Experimental Workflow for Low-Field MRI in Neuroscience Research. The diagram outlines the key stages in designing and executing low-field MRI experiments, from hardware preparation through data acquisition to advanced reconstruction and quantitative analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Low-Field MRI Development and Validation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phantom Materials | NiCl₂-doped agarose gels | Mimicking tissue T1/T2 values | Concentration optimization for field strength |

| Structured resolution phantoms | Spatial resolution assessment | Must account for lower resolution limits | |

| EMI Cancellation Systems | Deep learning models (U-Net, CNN) | Predicting and removing EMI | Requires training on paired shielded/unshielded data |

| Reference sensor arrays | Capturing environmental EMI | Strategic placement around scanner | |

| Image Reconstruction Software | Compressed sensing libraries | Accelerated acquisition reconstruction | Parameter optimization for low SNR regime |

| Parallel imaging toolboxes (SENSE, GRAPPA) | Accelerated parallel imaging | Coil sensitivity mapping at low field | |

| Quantitative Analysis Tools | Automated segmentation (SynthSeg, FreeSurfer) | Brain volume quantification | Validation against high-field references |

| SNR/CNR calculation scripts | Objective image quality assessment | Implementation of dual-acquisition method | |

| Magnet Design Components | Samarium-Cobalt (SmCo) permanent magnets | B₀ field generation with thermal stability | Preferred over NdFeB for temperature stability |

| Passive shimming components | B₀ homogeneity optimization | Ferromagnetic pieces for field correction |

The physics of SNR, CNR, and relaxometry at low magnetic fields presents both challenges and unique opportunities for clinical neuroscience research. While the reduced polarization at low field strengths inherently limits SNR, this can be effectively mitigated through sophisticated hardware design, optimized pulse sequences, and advanced reconstruction algorithms. The distinct relaxation properties at low field create contrast mechanisms that differ from conventional high-field MRI, requiring specialized protocol development but offering advantages for specific applications. For drug development professionals and neuroscientists, low-field portable MRI systems represent a transformative technology that can democratize access to neuroimaging, enable longitudinal monitoring at point-of-care, and facilitate large-scale population studies. As hardware miniaturization and artificial intelligence-driven reconstruction continue to advance, the performance gap between low-field and high-field systems will further narrow, solidifying the role of portable MRI as an indispensable tool in clinical neuroscience research.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has undergone a significant pendulum swing in technological emphasis over its development history. The narrative of MRI field strength is characterized by an early dominance of low-field systems, a subsequent industry-wide shift toward high-field machines driven by signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) advantages, and a contemporary renaissance of low-field technology fueled by engineering innovations and specific clinical needs. This evolution is particularly relevant within clinical neuroscience research, where the portability, cost-effectiveness, and unique imaging characteristics of modern low-field systems are opening new possibilities for study design and patient access. Understanding this historical trajectory provides essential context for evaluating the current and future role of portable low-field MRI in neuroscientific investigation and therapeutic development.

The Early Dominance of Low-Field MRI Systems

Technological Foundations of Early MRI

The initial development and commercialization of MRI technology in the 1980s were dominated by low-field systems, broadly defined as those operating at field strengths below 1.5 Tesla (T) [1]. These early scanners predominantly utilized resistive magnets or permanent magnets [1] [15]. Resistive magnets, while inexpensive and relatively straightforward to manufacture, were constrained to maximum field strengths of approximately 0.28 T and consumed substantial electrical power during operation [1]. Permanent magnets emerged as an alternative technology, offering the advantage of passive operation without continuous electrical current and enabling open scanner designs that improved patient comfort [1]. However, these systems were limited to approximately 0.4 T and exhibited sensitivity to temperature fluctuations, lacked dynamic shimming capabilities, and provided limited gradient performance [1].

Table 1: Characteristics of Early Low-Field MRI Magnet Technologies

| Magnet Type | Maximum Field Strength | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistive | ~0.28 T | Low manufacturing cost, relative ease of production | High power consumption, limited field strength |

| Permanent | ~0.4 T | Passive operation (no electrical current), open design possibilities | Temperature sensitivity, limited shimming and gradient performance |

Despite these technological constraints, low-field systems established MRI as a vital clinical tool during this formative period, providing unparalleled soft-tissue contrast without ionizing radiation.

The Shift Toward High-Field Systems

The 1980s and 1990s witnessed a decisive transition in the MRI market toward high-field systems. The introduction of the first 1.5T scanners in 1985 marked a turning point [15]. The subsequent decades saw a widening "citation gap" as scientific and clinical literature increasingly focused on high-field applications [15]. This shift was driven by a fundamental physical principle: SNR is directly proportional to the strength and homogeneity of the static magnetic field [1]. Higher field strengths yielded superior SNR, which translated to improved spatial resolution, reduced scan times, and enhanced contrast sensitivity [15] [16]. The development of superconducting magnets was instrumental in this transition, enabling stable high field strengths and superior image quality, albeit with substantial infrastructure demands including cryogenic cooling using liquid helium [1] [16]. Consequently, low-field MRI was largely relegated to niche applications or cost-sensitive environments, while 1.5T and later 3.0T systems became the clinical standard in high-income countries [1] [15].

The Present-Day Technological Renaissance

Drivers of the Low-Field Revival

The renewed academic, industry, and philanthropic interest in low-field MRI since the late 2010s stems from converging factors that address the limitations of both historical low-field and contemporary high-field systems.

Economic Accessibility: The high cost of high-field MRI represents a significant barrier to global healthcare access. The capital cost of a high-field system has been estimated to approach $1 million USD per tesla of field strength [1] [15]. In contrast, a modern 0.55T system may cost only 40-50% as much as a standard 1.5T scanner [1]. Additional savings are realized through reduced installation costs (up to 70% less), diminished infrastructure requirements (no reinforced flooring or copper shielding), and lower ongoing maintenance expenses (up to 45% less) [1]. This economic proposition is crucial for expanding access in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and underserved rural areas [15].

Technological Innovations: Advances in hardware and software have effectively mitigated the traditional image quality limitations of low-field MRI. Improved magnet designs, sophisticated gradient systems, and optimized radiofrequency (RF) coils have enhanced baseline performance [1] [15]. Furthermore, artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning reconstruction techniques now compensate for lower intrinsic SNR by denoising images and reducing acquisition times, significantly narrowing the performance gap with high-field systems for specific diagnostic tasks [1] [15].

Clinical and Operational Advantages: Modern low-field systems offer unique benefits aligned with evolving clinical needs. Their portability enables point-of-care imaging in intensive care units, emergency departments, and even ambulances [1]. They demonstrate reduced susceptibility artifacts, proving particularly valuable for imaging patients with metallic implants [1]. Enhanced patient comfort through quieter operation and more open designs improves tolerance and reduces scan termination rates [1].

Key Modern Low-Field Systems and Specifications

The current market landscape reflects this renaissance, with several low-field systems receiving FDA clearance and demonstrating clinical utility.

Table 2: Representative Modern Low-Field MRI Systems

| System Name | Field Strength | Primary Application | Key Technological Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperfine Swoop | 0.064 T | Portable head imaging | First FDA-cleared portable MRI; utilizes permanent magnets; can be integrated into mobile platforms [1] [15] |

| Siemens MAGNETOM Free.Max | 0.55 T | General purpose | Compact superconducting magnet; demonstrates advanced engineering for high-performance low-field imaging [1] [15] |

| Synaptive Evry | 0.5 T | Intraoperative | Designed for surgical guidance; integrates with operative workflow [15] |

| Aspect Embrace | 1.0 T | Neonatal | Tailored for infant imaging; addresses specific pediatric clinical needs [15] |

These systems exemplify the trend toward application-specific design, moving beyond the one-size-fits-all approach of earlier MRI generations.

Experimental Protocols and Validation in Clinical Neuroscience

Methodology for Diagnostic Accuracy Studies

Rigorous validation against clinical reference standards is essential for establishing low-field MRI in neuroscience research. The following protocol, derived from a hydrocephalus diagnostic study, provides a template for such validation [17].

- Patient Cohort: Recruit a sufficient sample size (e.g., N=130) with suspected pathology (e.g., hydrocephalus) to ensure statistical power [17].

- Multimodal Imaging: Each participant undergoes imaging with three modalities: the experimental mobile low-field (ML) MRI, conventional CT, and high-field 3.0T MRI as a reference standard [17].

- Image Analysis: Acquire key quantitative ventricular measurements from all three imaging modalities. Examples include ventricular volume, Evan's index (ratio of the maximum width of the frontal horns of the lateral ventricles to the maximal internal diameter of the skull), and callosal angle [17].

- Statistical Validation: Calculate Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) to assess agreement between ML MRI and reference standards. ICC values >0.95 indicate excellent reliability [17]. Perform Bland-Altman analysis to evaluate measurement bias and limits of agreement. Construct Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves to determine diagnostic accuracy, reporting Area Under the Curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy [17].

Quantitative Imaging Biomarker Acquisition

In neuroscience, quantitative MRI (qMRI) provides objective biomarkers for disease tracking. Low-field systems must demonstrate capability in acquiring these metrics.

- T1/T2 Relaxometry: Measures longitudinal (T1) and transverse (T2) relaxation times in milliseconds (ms), sensitive to tissue composition like myelin content [18]. Acquisition involves inversion-recovery (IR) or variable flip angle (VFA) sequences for T1, and multi-echo spin echo (MESE) for T2, typically requiring 4-8 minutes [18].

- Diffusion Metrics: Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC, mm²/s) and Fractional Anisotropy (FA) derived from diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequences, sensitive to microstructural integrity and white matter organization [18].

- Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping (QSM): Maps magnetic susceptibility (χ, ppm) to quantify brain iron deposition in neurodegenerative diseases, utilizing multi-echo gradient echo sequences [19].

- Volumetry: Regional brain volumes (cm³) and cortical thickness (mm) obtained from 3D T1-weighted sequences, crucial for tracking atrophy in dementia [18].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Low-Field MRI Neuroscience Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Phantom Kits | Validation of quantitative metrics (T1, T2, ADC); system calibration | Multimodal phantoms with known relaxation times and diffusion properties [18] |

| AI Reconstruction Software | Image denoising; resolution enhancement; acceleration of acquisition | Deep learning models (e.g., convolutional neural networks) trained on low/high-field image pairs [1] [15] |

| Perfusion Analysis Plugin | Calculation of hemodynamic parametric maps (e.g., CBF, CBV) from DCE-MRI data | Certified software (e.g., UMMperfusion 1.5.2) [20] |

| Tri-Variate Color Mapping Algorithm | Fusion of multiparametric MRI data (e.g., T2, ADC, PBF) into a single intuitive visualization | Custom MATLAB scripts implementing CIELAB color space for perceptual uniformity [20] |

Technical Workflows and Visualization

Workflow for Advanced Color Visualization of Multiparametric Data

The integration of multiple quantitative parameters is a challenge in neuroscience. The following workflow, adapted from a proven methodology, details the process for creating informative tri-variate color maps [20].

Diagram Title: Tri-Variate MRI Color Mapping

This visualization technique translates complex multiparametric data (e.g., T2-weighted images, Apparent Diffusion Coefficient maps, and perfusion maps) into a single, intuitively interpretable image by leveraging the three-dimensional CIELAB color space, which is perceptually uniform to the human visual system [20]. The process ensures that Euclidean distances in the data correspond linearly to perceived color differences, maximizing information transfer to the researcher [20]. This method has demonstrated diagnostic performance comparable to conventional side-by-side radiological evaluation in prostate cancer, and is equally applicable to neuroscience datasets [20].

Technical Implementation of a Portable MRI System

The deployment of a truly portable MRI system for point-of-care neuroscience research involves a specialized technical pipeline, from data acquisition to image interpretation.

Diagram Title: Portable MRI Data Pipeline

This workflow highlights the integrated role of portable hardware (e.g., the Hyperfine Swoop) and advanced software. The hardware employs permanent magnets, minimal RF shielding, and operates on standard power sources [1] [15]. The acquisition utilizes SNR-efficient strategies like balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP) or long readout spiral imaging to maximize information per unit time [15]. The computational processing heavily relies on AI-driven reconstruction to overcome inherent SNR limitations, and finally generates the quantitative maps essential for neuroscience research [1] [15]. Visualization should employ perceptually uniform color scales (e.g., "jet" or "hot" scales) that have been shown to improve performance in intensity discrimination tasks compared to grayscale [21].

The field of clinical neuroscience research is undergoing a transformative shift with the advent of portable low-field Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) systems. For decades, MRI has been a cornerstone of neurological investigation, yet its utility has been constrained by the high costs, limited accessibility, and substantial infrastructure demands of conventional high-field scanners. The re-emergence of low-field MRI, powered by significant advancements in hardware miniaturization, artificial intelligence (AI)-based image reconstruction, and sustainable design principles, is poised to democratize this critical technology [22] [23]. These innovations are creating a new paradigm where high-quality neuroimaging can be performed at the point-of-care, in resource-limited settings, and within novel research environments, thereby accelerating the pace of discovery in neuroscience and drug development. This whitepaper details the core technological drivers behind this revolution, providing a technical guide for researchers and scientists leveraging these tools for advanced clinical neuroscience applications.

Hardware Miniaturization: Enabling Portability and Accessibility

The development of portable MRI systems has been fundamentally enabled by breakthroughs in magnet design and hardware miniaturization. Traditional high-field MRI systems rely on large, heavy superconducting magnets that require costly infrastructure, including cryogenic cooling with liquid helium and specialized shielding [22]. In contrast, modern portable low-field systems utilize innovative magnet technologies that dramatically reduce their size, weight, and operational complexity.

Core Magnet Technologies

Contemporary portable low-field MRI systems primarily employ two types of magnet technologies, each with distinct advantages for neuroscience research:

- Permanent Magnets: Constructed from materials that generate a persistent magnetic field without requiring external power, permanent magnets enable truly portable and passive operation. Systems like the Hyperfine Swoop, the first FDA-cleared portable MRI, utilize this technology, operating at ultra-low field strengths (e.g., 0.064 Tesla) [22]. Their key advantages include zero helium consumption and minimal power requirements, making them ideal for bedside or mobile deployment.

- Compact Superconducting Magnets: Newer systems, such as the Siemens MAGNETOM Free.Max, are leveraging compact superconducting magnets that do not require active cooling or substantial electricity [22]. These designs maintain the stability and field homogeneity benefits of superconductivity while significantly reducing the size and infrastructure burden compared to their high-field counterparts.

The miniaturization of these core components has a direct and profound impact on the logistical and economic feasibility of MRI. As summarized in the table below, low-field portable systems offer substantial reductions in cost and infrastructure compared to traditional 1.5T systems.

Table 1: Economic and Infrastructure Comparison of MRI Systems

| Characteristic | Traditional 1.5T MRI | Modern Low-Field MRI |

|---|---|---|

| Estimated Capital Cost | ~$1 million USD per tesla [22] | 40-50% of a 1.5T system [22] |

| Installation & Transport Costs | Baseline (High) | Up to 70% reduction [22] |

| Maintenance Costs | Baseline (High) | Up to 45% lower [22] |

| Infrastructure Needs | Reinforced flooring, copper shielding, dedicated HVAC [22] | Significantly reduced or eliminated [22] |

| Power Consumption | High | Lower operational power demands [24] |

Neuroscience Research Applications

The portability enabled by hardware miniaturization unlocks novel research applications:

- Point-of-Care Neuroimaging: Researchers can perform brain imaging in intensive care units (ICUs), emergency departments, and stroke units, facilitating rapid diagnosis and monitoring of neurological conditions like traumatic brain injury and stroke without moving critically ill patients [22] [23].

- In-Situ and Longitudinal Studies: Proof-of-concept studies have demonstrated the integration of portable MRI into a standard van for home-based neuroimaging, enabling longitudinal studies of brain development or neurodegenerative diseases in community settings [22].

- Imaging Patients with Implants: Low-field systems produce reduced susceptibility artifacts near metallic hardware, making them particularly suitable for postoperative neurosurgical imaging and research involving patients with implants [22] [23].

AI and Deep Learning Reconstruction: Compensating for SNR Limitations

A fundamental challenge in low-field MRI is the inherently lower signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) compared to high-field systems. While hardware improvements contribute, the most significant gains in image quality are now being achieved through software, specifically artificial intelligence and deep learning-based reconstruction algorithms.

Technical Approaches and Experimental Protocols

AI-based reconstruction methods are designed to mitigate the SNR penalty and accelerate acquisition. The following table outlines key methodologies and their implementation in recent experimental protocols.

Table 2: AI-Based Reconstruction Methods for Low-Field MRI

| AI Method | Technical Function | Experimental Protocol & Application | Impact on Low-Field Neuroimaging |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning Denoising | Neural networks are trained to remove noise from MRI images, often using self-supervised learning techniques that do not require fully clean reference data [25]. | Protocol: A self-supervised learning method using Average-to-Average (Avg2Avg) loss was implemented for 0.55T MRI [25]. This technique adapts to the specific noise profile of the scanner. | Encourages the use of 0.55T and other low-SNR MRI scanners, making imaging more affordable and accessible for large-scale research studies [25]. |

| Accelerated Acquisition Reconstruction | Neural networks learn to reconstruct high-quality images from highly undersampled k-space data, dramatically reducing scan time [26]. | Protocol: A joint-attention deep learning network was used to reconstruct pre- and post-contrast T1-weighted 3D brain tumor images from accelerated acquisitions, exploiting correlations across sequences [25]. | Enables significant reductions in MRI protocol time, improving patient comfort and throughput, which is critical for clinical trials [25]. |

| Physics-Coupled Synthetic Data Generation | Generates synthetic MRI data from natural images by incorporating MRI physics models, enabling effective denoising without the need for large, difficult-to-acquire in-vivo datasets [25]. | Protocol: A method was developed to train a complex MRI denoising model using physics-coupled synthetic data derived from natural images, achieving performance on par with models trained on in-vivo data [25]. | Reduces dependence on large in-vivo datasets, addressing a major practical bottleneck in developing AI tools for low-field MRI [25]. |

These protocols demonstrate that AI is not merely an incremental improvement but a transformative technology that redefines the performance boundaries of low-field MRI. For neuroscience research, this translates to diagnostic-quality brain images acquired in shorter times or at lower field strengths, facilitating more efficient research workflows.

Visualization of AI-Driven Image Reconstruction Workflow

The diagram below illustrates a generalized workflow for AI-accelerated image reconstruction in low-field MRI, integrating the key methods described above.

Diagram 1: AI-Driven Low-Field MRI Reconstruction. This workflow shows how undersampled or noisy data from a low-field scanner is processed through an AI reconstruction engine, often incorporating a dedicated denoising step, to produce a high-quality image suitable for neuroscience research.

Sustainable Design: Environmental and Economic Imperatives

The push for sustainability in healthcare is redefining medical imaging. Portable low-field MRI systems align perfectly with this trend, offering significant advantages in energy efficiency and environmental impact over their high-field counterparts.

Energy Consumption and Regulatory Drivers

MRI systems are among the most energy-intensive devices in a hospital [24]. The energy demands of high-field scanners are driven by the need to maintain strong magnetic fields (particularly for superconducting magnets) and operate powerful gradient and cooling systems. In response, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has introduced the first-ever ENERGY STAR guidelines for medical imaging equipment, with an effective date of November 3, 2025 [24]. These specifications focus on automatic and manual power management features, emphasizing transitions to low-power modes during periods of inactivity. Low-field portable systems, with their inherently lower power demands for magnet operation and reduced cooling needs, are well-positioned to meet these new sustainability benchmarks.

Broader Sustainability Benefits

Sustainable design in portable MRI extends beyond energy consumption:

- Reduced Helium Dependency: Many portable systems using permanent magnets or novel compact superconductors eliminate or drastically reduce the consumption of liquid helium, a finite natural resource [22] [23].

- Lifecycle and Waste Reduction: Innovations like syringeless contrast injectors (e.g., Bracco's Max 3) help reduce plastic waste associated with MRI procedures [27].

- Economic Sustainability: The lower total cost of ownership—encompassing acquisition, installation, maintenance, and energy—makes low-field MRI economically sustainable for a wider range of research institutions and healthcare systems, thereby expanding the global research footprint [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

For neuroscientists designing experiments with portable low-field MRI, a suite of specialized "research reagents"—both chemical and computational—is essential. The following table details key components of this toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Portable Low-Field MRI in Neuroscience

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Macrocyclic GBCAs (e.g., VUEWAY) | Gadolinium-based contrast agents designed for effective enhancement at lower doses (e.g., 0.05 mmol/kg), minimizing gadolinium exposure in longitudinal studies and reducing environmental excretion [27]. |

| AI-Powered Contrast Enhancement Software (e.g., AiMIFY) | Software that uses AI to amplify image contrast in post-processing, potentially allowing for diagnostic-quality images with standard or reduced contrast doses, enhancing safety for research participants [27]. |

| AI Reconstruction Algorithms (e.g., Denoising, Super-Resolution) | Computational tools essential for enhancing SNR and resolution in low-field images. These are critical for extracting high-fidelity quantitative data on brain microstructure and pathology from inherently noisier datasets [26] [25]. |

| Multiparametric Quantitative Mapping Sequences | Advanced pulse sequences (e.g., MR Fingerprinting) for simultaneous T1, T2, and T2* mapping. When combined with AI reconstruction, these enable rapid, quantitative assessment of tissue properties in a single breath-hold or acquisition, crucial for studying disease biomarkers [25]. |

| Cloud-Based Imaging Platforms | Platforms that facilitate the transfer, storage, and remote analysis of imaging data, enabling multi-center neuroscience trials and collaboration by aggregating data from geographically dispersed portable scanners [28]. |

The convergence of hardware miniaturization, AI-driven reconstruction, and sustainable design is not merely improving portable low-field MRI—it is creating a new, versatile tool for clinical neuroscience. These innovation drivers are deeply interconnected: compact hardware enables portability, which creates a need for robust AI to ensure diagnostic quality, and the entire system is bound together by a design philosophy that prioritizes economic and environmental sustainability. For researchers and drug development professionals, this means unprecedented access to neuroimaging capabilities directly at the point of care, in the community, and within diverse populations previously excluded from advanced imaging research. As these technologies continue to mature, evidenced by a robust pipeline of AI research and evolving sustainability standards, portable low-field MRI is set to become an indispensable component of the modern neuroscience toolkit, powering more inclusive, efficient, and impactful brain research.

The pursuit of understanding the human brain is one of science's most ambitious endeavors, yet the benefits of neuroscience research remain starkly inaccessible to large portions of the global population. Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) carry over 70% of the world's neurological disease burden but generate only a small fraction of global neuroimaging research [8]. This disparity stems not from a lack of scientific interest but from systemic barriers in healthcare and research infrastructure that have created what can be termed the "global neuroscience equity gap."

The core of this challenge lies in the traditional tools of neuroscience itself. Conventional high-field magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) systems, operating at 1.5 Tesla or higher, have remained the gold standard for clinical neuroscience research despite their profound limitations in global accessibility. These systems require specialized infrastructure, substantial financial investment (often approaching $1 million USD per tesla of field strength), cryogenic cooling, significant power demands, and highly trained personnel [22]. The result is a dramatic imbalance in global research capacity—whereas Japan has approximately 276 MRI scanners per 5 million people, West African nations average just 1.1 scanners per 5 million people, representing a 178-fold discrepancy in accessibility [8].

This paper argues that addressing this equity gap requires a fundamental reimagining of neuroscience research infrastructure, with portable low-field MRI (LF-MRI) technology serving as a catalytic platform for democratizing global brain research. Operating at field strengths below 0.1 Tesla, these systems represent not merely a scaled-down version of conventional MRI but a paradigm shift in how neuroscience research can be conducted in resource-limited settings worldwide [8].

Low-Field MRI Technology: Technical Foundations and Innovations

Physical Principles and Historical Context

Low-field MRI technology represents a return to the foundational principles of magnetic resonance imaging, leveraging modern engineering innovations to overcome historical limitations. The earliest MRI scanners deployed in the 1980s were predominantly low-field systems utilizing resistive or permanent magnets, but they fell out of favor as the field prioritized increasing magnetic field strength to improve signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and spatial resolution [22]. This historical trajectory created a persistent assumption that "low field means low quality means low utility"—a misconception that has hindered technological development for global applications [8].

The physics of signal generation in MRI begins with the static magnetic field (B₀), measured in Tesla, which aligns hydrogen proton spins in biological tissues. When radiofrequency (RF) energy pulses are applied at the resonance frequency, protons are excited and subsequently relax, emitting signals that are spatially encoded using gradients and reconstructed into anatomical images. While SNR is directly proportional to field strength, this relationship is no longer the sole determinant of diagnostic utility, thanks to revolutionary advances in hardware design, acquisition physics, and computational reconstruction methods [22].

Modern Technical Advancements

Contemporary LF-MRI systems incorporate multiple technological innovations that collectively overcome the traditional limitations of low-field imaging:

Advanced Magnet Designs: Modern systems utilize compact superconducting magnets or high-performance permanent magnets that eliminate the need for liquid helium cryogenics and reduce power requirements. Innovations like Halbach array configurations optimize magnetic field homogeneity while minimizing weight and size [22] [4].

Enhanced RF Coils: Sophisticated receiver coil designs, including superconducting RF coils and multimodal surface coils, significantly improve SNR by minimizing resistance and thermal noise. These innovations enhance signal detection capabilities despite lower field strengths [22].

Artificial Intelligence Reconstruction: Deep learning algorithms and advanced reconstruction techniques substantially enhance image quality from LF-MRI systems. These computational methods can compensate for lower intrinsic SNR, enabling diagnostic-quality images previously achievable only with high-field systems [8] [22].

Portable System Architecture: Unlike conventional MRI systems weighing tons and requiring dedicated facilities, modern LF-MRI devices are designed for mobility. The Hyperfine Swoop, the first FDA-cleared portable MRI system, exemplifies this approach, enabling brain imaging at the point-of-care without infrastructure modifications [22].

Open-Source Platforms: A growing movement toward open-source hardware and software for LF-MRI promises to accelerate innovation and adaptation for specific research needs in diverse global settings [8].

Table 1: Key Technical Innovations in Modern Low-Field MRI

| Innovation Category | Specific Technologies | Performance Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Magnet Design | Halbach arrays, compact superconducting magnets, permanent magnets | Reduced size/weight, eliminated cryogenics, improved field homogeneity |

| RF Coils | Superconducting coils, multimodal surface coils, optimized geometries | Enhanced signal-to-noise ratio, improved signal detection |

| Image Reconstruction | AI-enhanced reconstruction, deep learning algorithms, noise reduction | Improved image quality, diagnostic utility comparable to high-field |

| System Architecture | Portable designs, single-sided configurations, battery operation | Enabled point-of-care imaging, reduced infrastructure requirements |

| Data Acquisition | Optimized pulse sequences, parallel imaging, accelerated protocols | Reduced scan times, motion artifact minimization |

Quantitative Evidence: Validating LF-MRI for Neuroscience Research

Diagnostic Performance and Clinical Utility

Empirical studies across diverse clinical settings have demonstrated that LF-MRI systems provide sufficient image quality for meaningful neuroscience research and clinical diagnosis. In a feasibility study conducted in remote Canada, implementation of a 0.064T portable MRI system produced diagnostic-quality images in 100% of 25 patients scanned, despite the challenging environment [29]. Notably, the technology demonstrated particular value in triaging patients, with an estimated 44% of patients avoiding transfer to a tertiary center for neuroimaging [29].

The diagnostic performance of LF-MRI extends across multiple neurological conditions. In a notable study of 221 patients with multiple sclerosis, researchers found no significant difference in diagnostic accuracy between 0.5T and 1.5T scanners, with both achieving an area under the curve of 0.96 [22]. This demonstrates that field strength alone does not determine diagnostic utility when modern acquisition and reconstruction techniques are employed.

Economic Advantages and Implementation Cost Analysis

The economic case for LF-MRI in global neuroscience research is compelling, with substantial cost advantages across the technology lifecycle:

Table 2: Comparative Cost Analysis: Low-Field vs. High-Field MRI Implementation

| Cost Component | High-Field MRI (1.5T-3T) | Low-Field MRI (<0.1T) | Cost Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capital Equipment | $1-3 million | $50,000-$500,000 | 50-90% |

| Installation/Infrastructure | Reinforced flooring, magnetic shielding, dedicated HVAC | Minimal infrastructure modifications | Up to 70% |

| Maintenance/Service | Expensive service contracts, cryogen replenishment | Lower maintenance costs, no cryogenics | Up to 45% |

| Transportation | Specialized transport, significant expenses | Highly portable, standard transport | >80% |

| Space Requirements | Dedicated suite (400-500 sq ft) | Standard room or mobile deployment | ~60% |

A detailed cost analysis of portable MRI implementation in remote Canada demonstrated significant healthcare system savings of approximately $854,841 based on 50 patients scanned over one year. A five-year budget impact analysis projected nearly $8 million in cumulative savings compared to patient transfers for conventional MRI [29]. Similar economic advantages were documented in prostate cancer imaging, where LF-MRI guided biopsy procedures demonstrated substantial cost efficiency compared to high-field approaches [30].

Research-Grade Data Capabilities

Beyond clinical triage, LF-MRI systems are increasingly capable of supporting sophisticated neuroscience research. A 2025 feasibility study demonstrated that task-based functional MRI (fMRI) is achievable at 0.55T, opening possibilities for functional neuroimaging in diverse global populations previously excluded from such research [4]. Additionally, methodological innovations in ultra-low-field protocol optimization enable reliable brain volume analysis with scan times of approximately 15 minutes, making population-scale neuroimaging studies feasible in resource-limited settings [4].

The Society for Equity Neuroscience (SEQUINS), established in 2024, exemplifies the growing institutional recognition that addressing brain health inequities requires dedicated research infrastructure capable of reaching underrepresented populations [31]. LF-MRI technology aligns precisely with this mission by enabling neuroimaging research across diverse geographic, socioeconomic, and cultural contexts.

Implementation Framework: Protocols for Global Neuroscience Research

Technical Protocol for LF-MRI Neuroscience Studies

Implementing successful neuroscience research with LF-MRI requires standardized protocols optimized for lower field strengths. The following methodology has been validated across multiple research contexts:

Equipment and Reagents:

- Portable LF-MRI system (0.064T-0.1T operating field)

- Integrated or compatible RF head coils

- Battery pack or standard power source (110V/220V)

- DICOM-compatible workstation for image reconstruction

- Secure data transmission capability (PACS network)

- AI-enhanced image reconstruction software

Imaging Protocol:

- System Calibration: Quality assurance checks including signal-to-noise ratio measurement and geometric distortion assessment

- Patient Positioning: Supine position with head immobilization using system-specific cushions

- Protocol Selection: Anatomical T1-weighted and T2-weighted sequences optimized for low-field

- Parameter Optimization: Repetition Time (TR): 500-2000ms; Echo Time (TE): 20-100ms; Matrix Size: 160×160 to 256×256; Slice Thickness: 3-5mm

- Data Acquisition: Scan duration 15-30 minutes depending on protocol complexity

- Image Reconstruction: Application of AI-based enhancement algorithms

- Quality Assessment: Real-time evaluation of diagnostic quality

- Data Management: Secure transfer to PACS with automated backup

This protocol has demonstrated feasibility in remote settings with scan success rates exceeding 95% and diagnostic quality adequate for quantitative volumetric analysis and lesion detection [29] [4].

Research Reagent Solutions for LF-MRI Neuroscience

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Low-Field MRI Neuroscience Studies

| Research Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Portable LF-MRI System | Primary imaging hardware for data acquisition | 0.064T-0.1T field strength, portable design, battery capability |

| AI Reconstruction Software | Image quality enhancement, noise reduction | Deep learning algorithms trained on matched low-field/high-field datasets |

| Quality Assurance Phantom | System calibration, performance validation | Geometric distortion assessment, SNR measurement, contrast resolution |

| Mobile Data Transmission Unit | Secure image transfer from remote locations | DICOM-compatible, encrypted transmission to central PACS |

| Open-Source Analysis Platform | Standardized image processing, volumetric analysis | Compatible with low-field image characteristics, automated processing |

Diagram 1: LF-MRI Research Implementation Workflow

Implementation Strategy for Global Neuroscience Equity

Building Research Capacity in Resource-Limited Settings

Successful implementation of LF-MRI neuroscience research requires a comprehensive approach that addresses both technical and social dimensions of global research partnerships. The "Second Track" program pioneered by Global Access Partners provides a valuable model, fostering innovative, cross-disciplinary approaches to complex problems through collaboration between community, government, and business stakeholders [32]. This approach emphasizes moving beyond policy discussion to focus on the "how" and "who" of policy delivery—exactly the implementation gap that often hinders global research equity.

Critical components of successful capacity building include:

Localized Training Pathways: Developing sustainable expertise through hands-on training programs for local researchers and technicians, creating a self-sustaining research ecosystem rather than creating dependency on external expertise [8].

Research Infrastructure Co-Development: Engaging local researchers in system customization and protocol development to ensure technologies are appropriately adapted to local healthcare contexts and research priorities [8].

Ethical Data Governance Frameworks: Establishing clear protocols for data ownership, sharing, and utilization that prioritize equitable benefits for participating communities and respect local norms and regulations [8].

Cross-Sector Partnerships: Creating sustainable collaborations between academic institutions, healthcare providers, technology developers, and community organizations to ensure research addresses locally relevant questions while maintaining scientific rigor [32].

Addressing Underrepresentation in Neuroscience Research

The equity imperative in neuroscience extends beyond geographic access to include representation of diverse populations in research. Current neurological studies disproportionately represent Western, educated, industrialized populations, creating critical gaps in understanding brain health across different genetic backgrounds, environmental exposures, and cultural contexts [31]. The Society for Equity Neuroscience (SEQUINS) has identified this representation gap as a fundamental challenge for the field, noting that certain racial and ethnic communities, lower socioeconomic groups, and marginalized populations experience both poorer neurological outcomes and systematic underrepresentation in research [31].

LF-MRI technology directly addresses this challenge through its unique ability to deploy research infrastructure directly to underserved communities. Mobile research units, such as those highlighted by the Global Alzheimer's Platform Foundation, demonstrate how portable neuroimaging can increase participation of historically underrepresented populations in clinical research [33]. Similarly, the ENACT Act legislation recognizes that increasing diversity in clinical trials requires fundamentally rethinking research infrastructure to reduce participation burdens and expand outreach to underrepresented communities [34].

Diagram 2: Multidimensional Strategy for Neuroscience Equity

Future Directions and Implementation Challenges

While LF-MRI technology presents transformative potential for global neuroscience equity, several challenges require ongoing attention. Technical limitations in spatial resolution and scan times continue to improve but remain considerations for certain research applications. The development of comprehensive training curricula specifically designed for LF-MRI operators in resource-limited settings is essential for sustainable implementation. Perhaps most critically, establishing sustainable funding models and business cases for LF-MRI deployment in LMICs requires coordinated effort across technology developers, funding agencies, and healthcare systems.

The research community is actively addressing these challenges through initiatives such as the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM) Low-Field Study Group, which coordinates technical innovation and knowledge sharing [4]. Recent advances presented at the 2025 ISMRM conference include improved B₀ homogeneity through active cooling of permanent magnets, novel RF coil designs for enhanced transmit efficiency, and optimized protocols for specific research applications including neurodevelopment and aging [4].

The global access gap in neuroscience research represents both an ethical imperative and a scientific limitation. Portable low-field MRI technology offers a transformative pathway toward more equitable, representative, and globally relevant brain research. By fundamentally reimagining research infrastructure to prioritize accessibility, adaptability, and local capacity building, the neuroscience community can address both the ethical challenges of research equity and the scientific limitations of unrepresentative sampling.

The technical evidence is compelling: modern LF-MRI systems provide diagnostically relevant image quality, research-grade data capabilities, and substantial economic advantages over conventional high-field systems. When implemented within a framework of equitable partnership, community engagement, and local capacity building, this technology can democratize neuroscience research and ensure that brain health discoveries benefit all global populations, not merely the most privileged.

Realizing this vision requires coordinated action across researchers, technology developers, funding agencies, and policy makers. Through collective commitment to research equity, the neuroscience community can harness LF-MRI technology to create a more inclusive, representative, and effective global research ecosystem—transforming the equity imperative from moral aspiration to scientific reality.

Deploying Portable MRI: From Bedside to Global Health Neuroscience

Point-of-care (POC) neuroimaging represents a paradigm shift in diagnostic medicine, bringing advanced imaging capabilities directly to the patient bedside. The development of portable, low-field magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) systems has enabled this transformation, particularly for critically ill patients in intensive care units (ICUs), emergency departments (EDs), and intraoperative settings. These innovative technologies operate at magnetic field strengths substantially lower than conventional high-field MRI systems (typically 1.5-3 T), utilizing strengths ranging from 0.064 T to 0.55 T to provide diagnostic-quality imaging at the point of care [1] [35].

The fundamental advantage of portable low-field MRI lies in its ability to perform neuroimaging without the risks and logistical challenges associated with intrahospital transport of critically ill patients. Studies have demonstrated that intrahospital transport carries significant risks, with adverse event rates as high as 60% and serious adverse events occurring in nearly 10% of transports [36]. These include severe hypoxia, hypotension, accidental extubation, and equipment failure [36]. Portable MRI technology eliminates these risks while providing timely diagnostic information that can guide clinical decision-making in time-sensitive neurological emergencies.

This technical guide examines the clinical applications, technological foundations, and implementation methodologies for portable low-field MRI systems in critical care and emergency settings, framed within the broader context of clinical neuroscience research.

Technical Specifications of Portable Low-Field MRI Systems

Fundamental Physical Principles

Low-field MRI systems operate on the same fundamental physical principles as high-field systems but with important technical distinctions. The signal generation process in MRI involves three key steps: (1) alignment of hydrogen proton spins with the static magnetic field (B0), creating a net magnetization vector; (2) excitation of these protons using radiofrequency (RF) energy pulses at the resonance frequency; and (3) detection of the signal generated as protons relax back to equilibrium, characterized by T1 (longitudinal) and T2 (transverse) relaxation processes [1].

The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in MRI is directly proportional to the strength and homogeneity of the static magnetic field. While higher field strengths generally produce higher SNR, recent innovations in magnet design, RF coil technology, and advanced reconstruction algorithms have significantly narrowed the performance gap between low-field and high-field systems [1]. Modern low-field systems incorporate engineering advances including compact superconducting magnets (e.g., Siemens MAGNETOM Free.Max) or high-performance permanent magnets (e.g., Hyperfine Swoop) that do not require active cooling or substantial electricity [1].

System Specifications and Capabilities

The Hyperfine Swoop system, as a representative portable MRI device, operates at 0.064 T magnetic field strength and has received FDA 510(k) clearance for clinical use [37] [35]. Key technical specifications include:

- Physical dimensions: Height of 140 cm, width of 86 cm, and weight of approximately 630 kg [35]

- Power requirements: Standard 15 A, 110 V wall outlet without need for cryogens [35]

- Imaging sequences: T1-weighted fast spin-echo, T2-weighted fast spin-echo, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) with apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) sequences [37]