Overcoming the Signal-to-Noise Ratio Challenge in Non-Invasive Brain-Computer Interfaces: Strategies for Biomedical Research

Non-invasive Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) offer tremendous potential for clinical diagnostics, neurorehabilitation, and cognitive research, yet their widespread adoption is hampered by a fundamental challenge: the low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of...

Overcoming the Signal-to-Noise Ratio Challenge in Non-Invasive Brain-Computer Interfaces: Strategies for Biomedical Research

Abstract

Non-invasive Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) offer tremendous potential for clinical diagnostics, neurorehabilitation, and cognitive research, yet their widespread adoption is hampered by a fundamental challenge: the low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of neural recordings. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the physiological and technical origins of poor SNR in systems like EEG. It details cutting-edge methodological advances in signal processing, electrode technology, and hybrid approaches that enhance signal fidelity. The article further offers practical optimization frameworks for real-world deployment, presents a comparative analysis of BCI modalities, and concludes with future trajectories for integrating high-fidelity BCIs into biomedical research and therapeutic development.

Understanding the SNR Bottleneck: The Core Challenge in Non-Invasive BCI

Defining Signal-to-Noise Ratio in the Context of EEG and fNIRS

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) and why is it a critical challenge in non-invasive BCI research?

Answer: Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) quantifies the strength of a desired neural signal relative to the background noise. A high SNR indicates a clear, detectable signal, while a low SNR means the signal is obscured by noise. In non-invasive BCI research, this is a fundamental challenge because the signals of interest (neural electrical activity for EEG, hemodynamic responses for fNIRS) are inherently weak when measured through the scalp and skull [1] [2]. The resulting low SNR can severely limit the reliability, accuracy, and information transfer rate of BCI systems, making it difficult to distinguish a user's intentional commands from irrelevant brain activity or artifacts [3] [1].

FAQ 2: What are the primary sources of noise in EEG and fNIRS experiments?

Answer: The two modalities are susceptible to different types of noise, which can be categorized as follows:

Table: Common Noise Sources in EEG and fNIRS

| Modality | Physiological Noise | Motion & Environmental Noise | Instrumental Noise |

|---|---|---|---|

| EEG | Ocular artifacts (EOG), muscle activity (EMG), cardiac activity (ECG) [4] | Head movement, line noise (50/60 Hz) from power sources [5] [1] | Electrode impedance fluctuations, amplifier noise [1] |

| fNIRS | Cardiac pulsation, respiration, blood pressure changes (Mayer waves), systemic scalp blood flow [4] [6] [7] | Head movement, which directly disrupts optode-scalp coupling [5] [6] | Instrument instability, ambient light leakage [6] |

A key challenge in fNIRS is that task-evoked systemic physiology (e.g., changes in heart rate or blood pressure) can create hemodynamic changes in the scalp that mimic the genuine cortical brain signal, leading to potential "false positives" if not properly corrected [7].

FAQ 3: How does the combination of EEG and fNIRS help to overcome low SNR limitations?

Answer: EEG and fNIRS are highly complementary modalities. Their integration, known as multimodal fusion, leverages the strengths of one to compensate for the weaknesses of the other, thereby effectively increasing the system's overall SNR for decoding brain states [5] [4] [8].

- Temporal-Spectral Complementarity: EEG provides millisecond-scale temporal resolution, capturing the direct electrical firing of neurons, while fNIRS tracks the slower, secondary hemodynamic response (over seconds) with better spatial resolution [5] [8].

- Physiological Cross-Validation: The signals are linked via neurovascular coupling—the process where neural activity triggers a localized hemodynamic response [5]. An observed change in hemoglobin concentrations from fNIRS that coincides with a specific EEG rhythm pattern provides built-in validation that a genuine neural event has occurred, increasing confidence over a single-modality measurement [5] [4].

- Noise Resistance: fNIRS is relatively robust to motion artifacts and electrical noise that severely corrupt EEG signals. Conversely, advanced data-driven fusion methods can use the fast electrical information from EEG to help model and remove physiological noise (like cardiac pulsation) from the fNIRS signal [4].

Research using multilayer network models has demonstrated that this integrated approach provides a richer and more comprehensive understanding of brain function than unimodal analyses alone [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Low SNR in fNIRS Data

Problem: The measured fNIRS signal shows a weak or non-existent hemodynamic response, or the signal is dominated by large, irregular artifacts.

Solution: Implement a robust pre-processing and processing pipeline.

Table: Common fNIRS Pre-processing and Processing Techniques

| Step | Technique | Function | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-processing | Bandpass Filtering [6] | Removes high-frequency noise (e.g., cardiac) and low-frequency drift (e.g., respiration). | High-pass: ~0.01 Hz; Low-pass: ~0.2-0.3 Hz |

| Wavelet Filtering [6] | Effective for removing specific, structured noise like motion artifacts. | Decomposes signal into time-frequency components. | |

| Short-Channel Regression [7] | Critical step. Uses a short source-detector separation channel (~8-10 mm) to measure and regress out scalp hemodynamics. | Source-detector distance < 15 mm | |

| Processing | General Linear Model (GLM) [6] | Models the expected hemodynamic response to task conditions, statistically isolating the task-related signal. | Canonical Hemodynamic Response Function (HRF) |

| Multi-Channel Regression [7] | An alternative when short channels are unavailable; regresses out a global component common to multiple long-distance channels. | Requires multiple channels over the head. |

Important Considerations:

- The choice of processing pipeline significantly impacts results and reproducibility. Studies show that nearly 80% of research teams agreed on group-level findings when using proper methods, but agreement was lower for individual-level data, largely due to differences in how poor-quality data and physiological confounders were handled [9].

- Avoid using manufacturer-provided standard processing as a "black box" without understanding the steps, as this can lead to false positives from uncorrected systemic artifacts [7].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Low SNR in EEG Data

Problem: The EEG signal is noisy, making it difficult to detect event-related potentials (ERPs) or distinct brain rhythms (e.g., alpha, beta).

Solution: Focus on artifact removal and signal enhancement techniques.

- Artifact Removal: Use advanced algorithms to identify and remove contaminants.

- Ocular Artifacts: Apply regression-based methods or Blind Source Separation (e.g., Independent Component Analysis - ICA) to identify and remove components associated with eye blinks and movements [4] [1].

- Muscle Artifacts: Utilize filtering and ICA to target the high-frequency components characteristic of EMG noise [4].

- Spatial Filtering: Implement techniques like Common Average Reference (CAR) or Laplacian filtering to reduce global noise and enhance the locality of brain signals [1].

- Trial Averaging: For evoked responses like ERPs, averaging multiple trials together will suppress random noise and reinforce the time-locked neural signal.

Guide 3: A Methodological Protocol for Multimodal fNIRS-EEG to Enhance SNR

This protocol outlines a concurrent fNIRS-EEG experiment based on a motor imagery paradigm, a common BCI task [8].

Objective: To simultaneously record and analyze electrophysiological (EEG) and hemodynamic (fNIRS) brain activity during a motor imagery task, leveraging their complementarity to achieve a higher effective SNR for brain state classification.

Materials and Setup:

- EEG System: A high-density EEG system with compatible electrode cap.

- fNIRS System: A continuous-wave fNIRS system with wavelengths typically at 760 nm and 850 nm, integrated into the same cap or worn separately [5] [8].

- Optode Placement: Optodes should be positioned over the brain regions of interest (e.g., the sensorimotor cortex for motor imagery, using the international 10-20 system for placement) [8].

- Short-Separation Channels: Incorporate fNIRS source-detector pairs with short separations (e.g., < 15 mm) to record superficial scalp hemodynamics for later regression [4] [7].

- Stimulus Presentation: Software to present visual cues (e.g., arrows indicating "left-hand" or "right-hand" motor imagery).

Procedure:

- Participant Preparation: Fit the participant with the integrated EEG-fNIRS cap. Apply electrolyte gel for EEG electrodes and ensure good optical contact for fNIRS optodes. Check signal quality before starting.

- Experimental Paradigm:

- Use a block design consisting of alternating periods of rest and task.

- Each trial begins with a fixation cross (rest period, e.g., 20 seconds).

- A visual cue is then displayed, instructing the participant to perform either left-hand or right-hand motor imagery (task period, e.g., 10 seconds).

- Repeat for multiple trials (e.g., 20-30 per condition).

- Data Acquisition: Start simultaneous recording of EEG and fNIRS data. Synchronize the timing of the paradigm with the data acquisition systems using trigger signals.

- Data Processing:

- fNIRS Processing: Convert raw light intensity to changes in oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) concentration. Apply a bandpass filter, then use the short-separation channels to regress out superficial noise. Model the hemodynamic response using a GLM [6] [7].

- EEG Processing: Apply bandpass filtering (e.g., 0.5-45 Hz). Correct for artifacts using ICA. For motor imagery, focus on extracting power in specific frequency bands (e.g., sensorimotor rhythms in the mu/beta band) [1].

- Data Fusion and Analysis: Employ data-driven fusion methods (e.g., concatenating features, joint classification) to combine the temporal features from EEG with the spatial features from fNIRS to improve the classification accuracy of the motor imagery tasks [4] [8].

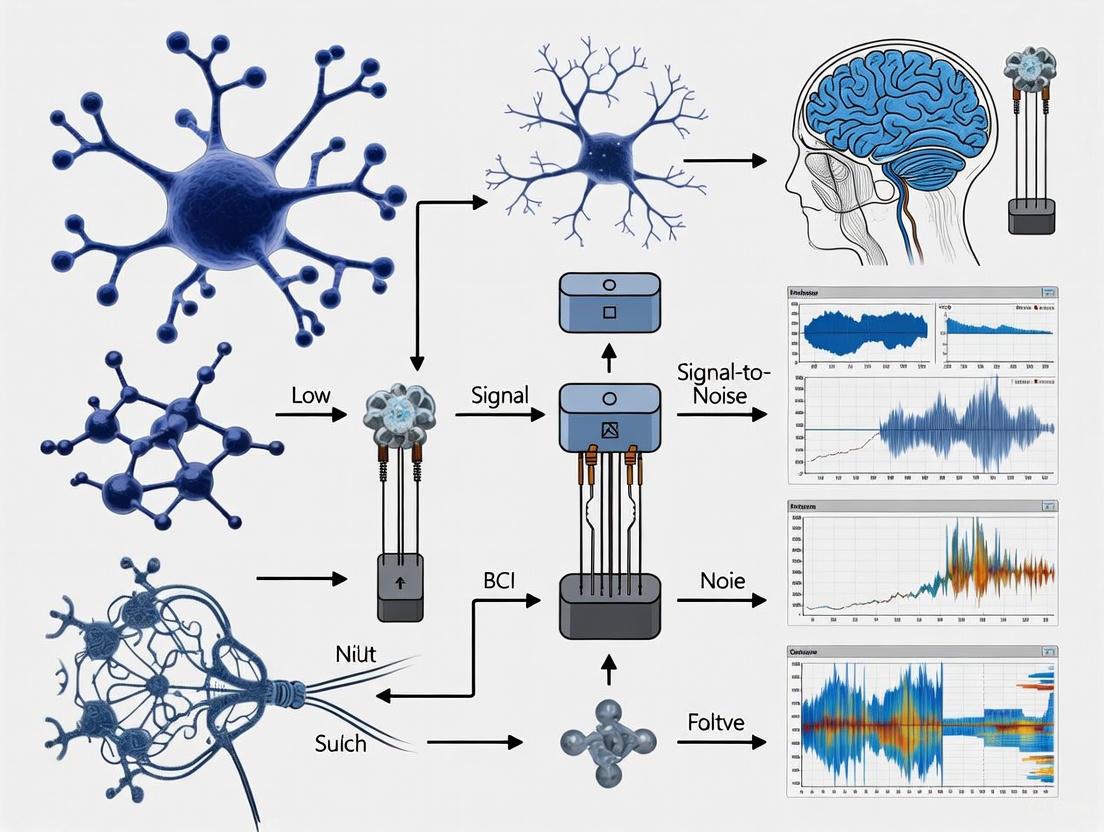

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Neural Activity to Measured Signals

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Concurrent fNIRS-EEG Experiments

| Item | Function in Research | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Integrated EEG-fNIRS Cap | A head cap with pre-configured positions for both EEG electrodes and fNIRS optodes. | Ensures consistent and co-registered placement of both modalities on the scalp according to the 10-20 system [8]. |

| Short-Separation fNIRS Channels | fNIRS source-detector pairs placed 8-15 mm apart. | Critical for measuring and subsequently regressing out hemodynamic noise originating from the scalp, which is a major confounder for cortical signals [4] [7]. |

| Electrolyte Gel | A conductive medium used for EEG electrodes. | Reduces impedance between the scalp and electrode, improving the quality of the recorded electrical signal and reducing noise [1]. |

| General Linear Model (GLM) Software | A statistical framework (e.g., in MATLAB, Python) for analyzing fNIRS data. | Used to model the expected hemodynamic response to stimuli and statistically evaluate the presence of a task-related signal, isolating it from noise [6]. |

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) Algorithm | A blind source separation algorithm for EEG data. | Effectively identifies and removes stereotypical artifacts like eye blinks and muscle activity from the continuous EEG signal [4] [1]. |

| Data Fusion Toolbox | Software libraries (e.g., in Python) for multimodal data analysis. | Enables the integration of EEG and fNIRS features at the data, feature, or decision level to improve the SNR and performance of brain state decoding [4] [8]. |

Multimodal fNIRS-EEG Experimental Workflow

For researchers and scientists working in non-invasive Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) development, understanding the physiological origins of signal degradation is fundamental to improving the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Non-invasive BCIs, particularly those using electroencephalography (EEG), face inherent challenges because the electrical signals generated by the brain are significantly attenuated and distorted as they pass through various biological tissues before reaching electrodes on the scalp [10] [11].

The brain's electrical activity originates from the summed postsynaptic potentials of pyramidal neurons. To be detectable at the scalp, this activity must propagate through the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), skull, and scalp—each with different electrical conductive properties. This journey results in substantial signal weakening, spatial blurring, and contamination by various biological and environmental artifacts [11] [12]. This guide provides a structured troubleshooting framework to identify, understand, and mitigate these sources of signal degradation in your experimental setups.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary physiological sources of the low signal-to-noise ratio in non-invasive EEG?

The low SNR stems from multiple physiological factors [11]:

- Signal Attenuation and Spatial Smearing: The skull acts as a low-pass filter, severely attenuating signals (especially higher frequencies) and blurring their spatial origin. The electrical signal can be weakened by as much as 100 times as it passes through these layers [10] [12].

- Non-Neural Biological Artifacts: These include electrical activity from eye movements (electrooculogram, EOG), muscle contractions (electromyogram, EMG), and heart activity (electrocardiogram, ECG). These signals are often orders of magnitude stronger than cortical EEG, making them a predominant source of contamination [11].

- Physiological Variability: Brain signals are inherently non-stationary and influenced by the subject's age, psychology, fatigue, and testing environment, leading to significant intra- and inter-subject variability [11].

Q2: How does the choice between wet and dry electrodes impact signal quality?

The electrode-skin interface is a critical factor in signal quality [13] [14]:

- Wet Electrodes: Use a conductive gel to reduce impedance between the scalp and electrode. They provide higher signal quality and lower impedance, making them the standard for clinical-grade research. The main trade-offs are the lengthy setup time, need for expert application, and subject discomfort during prolonged use. Gel can also dry out, degrading signal over long sessions [13].

- Dry Electrodes: Are quick to set up and more comfortable for users, ideal for consumer wearables and long-term monitoring. However, the convenience comes with a tradeoff: they typically have a higher and more variable electrode-skin impedance, resulting in a noisier signal more susceptible to motion artifacts [13] [14]. Modern designs with active electronics help mitigate this issue.

Q3: What are the most effective signal processing techniques to isolate neural signals from noise?

A combination of denoising and advanced feature extraction techniques is required [11]:

- Preprocessing & Denoising: Use band-pass filters to isolate frequency bands of interest (e.g., Alpha: 8-13 Hz, Beta: 13-30 Hz). Apply techniques like Independent Component Analysis (ICA) to identify and remove stereotypical artifacts like eye blinks and heartbeats.

- Feature Extraction: To overcome the low SNR, move beyond raw signal analysis. Extract informative features such as temporal patterns (e.g., event-related potentials like P300), spectral power in specific bands, or connectivity measures between electrodes [11].

- Machine Learning Classification: Employ classifiers like Support Vector Machines (SVM) or deep learning models such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to recognize patterns in the extracted features that correlate with the user's intent, even in a noisy background [11] [15].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Symptom | Potential Physiological Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High-frequency noise and slow drift in signal | Poor electrode-skin contact; sweating; dry gel. | Re-prep or replace the electrode. Ensure skin is clean and lightly abraded. For wet electrodes, check for sufficient gel [11] [14]. |

| Large, slow voltage shifts | Ocular artifacts (eye blinks and movements). | Apply ICA to remove components correlated with EOG. Instruct the subject to minimize eye movements and fixate on a point [11]. |

| High-frequency, burst-like noise | Muscle artifacts (EMG) from jaw clenching, forehead frowning, or neck tension. | Use spectral analysis to identify EMG contamination (typically 20-300 Hz). Apply notch or high-pass filtering. Encourage the subject to relax facial and neck muscles [11]. |

| Periodic, sharp spikes in the signal | Cardiogenic artifacts (ECG) or pulse artifacts. | This can be removed using ICA or template subtraction algorithms that are synchronized with the heartbeat [11]. |

| Unstable signal and high impedance across multiple channels | Mechanical motion of cables or the subject; poor grounding. | Secure the headset and cables to prevent tugging. Ensure the ground/reference electrode has excellent contact. Use a head cap for stability [12]. |

| Inconsistent BCI performance across subjects or sessions | High inter-subject variability and non-stationary nature of EEG signals. | Employ subject-specific calibration and adaptive machine learning models like Transfer Learning (TL) to personalize the BCI system [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Signal Quality Validation

Protocol 1: Systematic Impedance Checking and artifact Labeling

Objective: To establish a baseline for signal quality at the start of an experiment. Materials: EEG system, abrasive skin prep gel, conductive gel, impedance checker. Methodology:

- Application: Apply electrodes according to the international 10-20 system.

- Impedance Check: Measure impedance at every electrode. The target is typically < 10 kΩ for wet electrode systems [14]. For dry electrodes, consistent impedance across channels is more critical than an absolute value.

- Baseline Recording: Before the main task, record a 2-minute resting-state baseline (eyes-open and eyes-closed). This helps identify subject-specific noise profiles.

- Artifact Labeling: During the experiment, use a trigger or marker to label periods of known artifacts (e.g., experimenter-tagged eye blinks, subject-reported swallows). Outcome: A log of initial impedance values and a baseline recording that can be used for data-driven cleaning (e.g., ICA) later.

Protocol 2: Validation of Dry Electrode Performance Against Wet Electrodes

Objective: To quantitatively compare the signal quality of a dry electrode system against a clinical-grade wet system. Materials: A wet EEG system, a dry EEG headset, and a data synchronization unit. Methodology:

- Setup: Fit the subject with both systems simultaneously, ensuring electrodes are as co-located as possible.

- Task Paradigm: Conduct a block-designed experiment with alternating periods of rest and a known neural response task (e.g., alternating eyes-open/eyes-closed to evoke Alpha rhythm, or a visual P300 task).

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) of the event-related potential (ERP) for both systems.

- Compare the band power in the Alpha band during eyes-closed vs. eyes-open conditions.

- Compute the Cohen's Kappa agreement for sleep staging or another well-defined neural state classification, if applicable [14]. Outcome: A direct, quantitative comparison of SNR and classification accuracy, validating the dry electrode system's performance for a specific research application.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Signal Degradation Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the journey of a neural signal from its origin in the cortex to the scalp electrode, highlighting the points of degradation.

Experimental Workflow for SNR Improvement

This workflow outlines a systematic approach to diagnosing and improving SNR in BCI experiments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Essential Material / Tool | Function in BCI Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Abrasive Skin Prep Gel | Removes dead skin cells and oils to lower electrode-skin impedance. | Critical for achieving stable impedances <10 kΩ. Avoid excessive abrasion that causes irritation [14]. |

| Electrolyte Gel (Wet Systems) | Forms a stable ionic bridge between skin and electrode, reducing impedance and half-cell potential. | Choose a chloride-based gel for stable DC potentials. Beware of drying over long sessions [13]. |

| Active Dry Electrodes | Amplifies the signal directly at the source to mitigate noise from high electrode-skin impedance. | Ideal for consumer applications and quick setups. Signal quality is improving but may not yet match high-end wet systems [13] [14]. |

| ICA Algorithm Software | Statistically separates neural signals from non-neural artifacts (EOG, EMG) in recorded data. | A powerful blind source separation tool. Requires good-quality input data and is computationally intensive [11]. |

| Machine Learning Toolboxes (e.g., SVM, CNN, TL) | Classifies noisy neural signals into intended commands by learning complex patterns. | Transfer Learning (TL) is key for overcoming inter-subject variability and reducing calibration time [15]. |

| Multimodal Fusion (fNIRS/EEG) | fNIRS provides complementary hemodynamic data that is less susceptible to electrical artifacts. | Helps validate EEG findings and can improve robustness of state detection in hybrid BCI systems [14] [16]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common technical noise sources in non-invasive BCI experiments? The most common technical noise sources can be categorized into hardware limitations and environmental artifacts. Hardware limitations include the physical and electrical properties of the electrodes and the recording equipment itself, such as high impedance at the skin-electrode interface and amplifier noise [10]. Environmental artifacts encompass electromagnetic interference from power lines (50/60 Hz) and other electronic equipment, as well as fluctuations in environmental conditions that can affect signal stability [17].

FAQ 2: How can I tell if my EEG signal is contaminated by environmental noise versus a hardware problem? Environmental noise, like 50/60 Hz power line interference, often appears as a distinct, persistent peak in the frequency spectrum. Hardware problems, such as a faulty electrode with high impedance, typically manifest as abnormal signal patterns on a specific channel, including unusually low amplitude, flatlining, or high-frequency noise that isn't coherent across other channels [17]. A systematic check of each electrode's impedance is the first step in diagnosing a hardware issue.

FAQ 3: What is the impact of these noise sources on the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in BCI research? Noise sources directly degrade the SNR by introducing unwanted signal variance that obscures the neural signals of interest. A low SNR makes it difficult to detect event-related potentials (like the P300) or classify motor imagery tasks accurately, leading to reduced BCI performance and reliability [10]. Effectively managing these noise sources is therefore critical for overcoming the inherent challenge of low SNR in non-invasive BCI research [3].

FAQ 4: Are there specific experimental protocols to minimize environmental artifacts? Yes, several protocols can help. These include:

- Artifact Avoidance: Using electrically shielded rooms, increasing the distance between the subject and electromagnetic sources, and employing active electrodes that amplify the signal closer to the source [17].

- Subject Preparation: Properly preparing the scalp to reduce skin-electrode impedance and instructing participants to minimize blinks and muscle movements during critical trial periods. However, note that asking users to refrain from blinking can lead to mental fatigue [17].

- Online Parity in Filtering: Applying digital filters to short, segmented data epochs in real-time (as would be done during online BCI use) rather than only filtering the entire dataset offline after collection. This approach has been shown to improve model performance [17].

FAQ 5: What recent hardware innovations are helping to overcome traditional limitations? Recent innovations focus on improving the quality and stability of the signal acquisition at the source. A key development is the creation of wearable microneedle sensors that slightly penetrate the skin. These sensors avoid hair follicles, reduce impedance, and get closer to the neural signal source, resulting in higher-fidelity recordings that are robust to motion artifacts. Such devices have demonstrated high classification accuracy (e.g., 96.4%) during activities like walking and running [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving High Impedance Electrode Issues

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Visual Inspection | Check for dried electrolyte gel, poor skin contact, or damaged wires. | Ensure all electrodes are firmly attached with sufficient conductive medium. |

| 2 | Impedance Check | Use your amplifier's built-in impedance measurement function. | Impedance should ideally be below 10 kΩ for each channel. Mark channels with significantly higher readings. |

| 3 | Re-prep Skin | Gently abrade the skin site and apply fresh conductive gel or paste. | This is the most common solution for high impedance. |

| 4 | Re-test Impedance | Measure the impedance again after re-prepping. | If impedance remains high, proceed to hardware checks. |

| 5 | Hardware Check | Swap the problematic electrode with one from a known good channel. | If the problem moves with the electrode, the electrode/cable is faulty. If the problem stays on the original channel, the amplifier input may be faulty. |

Guide 2: Mitigating Power Line (50/60 Hz) Interference

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Environment Scan | Identify and turn off non-essential electronic devices near the subject and recording setup. | Common sources: monitors, power supplies, unshielded cables. |

| 2 | Impedance Balancing | Ensure all electrode impedances are low and, crucially, balanced. | Balanced impedances help reject common-mode noise. A difference of >10 kΩ between electrodes can cause issues. |

| 3 | Check Grounding | Verify the subject ground electrode has excellent contact and low impedance. | A poor ground is a frequent cause of 50/60 Hz noise. |

| 4 | Apply Notch Filter | As a last resort, apply a 50 Hz or 60 Hz notch filter in your acquisition software. | Use cautiously, as it may remove neural signals in the same frequency band. Always document filter settings [17]. |

Quantitative Data on Noise and Performance

Table 1: Comparison of Non-Invasive BCI Sensor Technologies and Noise Characteristics

| Sensor Type | Key Feature | Reported Advantage / Impact on Noise | Classification Accuracy (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Wet Electrodes | Conductive gel for low impedance [10] | Gold standard for signal quality but cumbersome; gel can dry, increasing noise over time. | Varies widely with paradigm and subject. |

| Dry Electrodes | No gel required [10] | Higher and more variable impedance, prone to motion artifacts. Faster setup. | Generally lower than wet electrodes due to higher noise. |

| Wearable Microneedle Sensors | Minimal skin penetration [18] | Reduces impedance by avoiding hair and getting closer to signal source; stable for up to 12 hours. | 96.4% (Visual stimulus classification during movement) [18]. |

| Optimized Channel Selection (SPEA-II) | Algorithmically selects best EEG channels [19] | Reduces redundant data and noise from non-informative channels, improving SNR for Motor Imagery. | Outperformed conventional methods in MI-based BCI systems [19]. |

Table 2: Common Artifact Types and Filtering Approaches

| Artifact Type | Origin | Typical Frequency Range | Recommended Filtering Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power Line Interference | Environment | 50 Hz or 60 Hz (narrowband) | Notch Filter [17] |

| Ocular Artifacts (Blinks, Eye Movements) | Physiological | Low-frequency (< 4 Hz) | High-pass filter (e.g., 0.5-1.0 Hz); Advanced techniques like Independent Component Analysis (ICA) [17] |

| Muscle Artifacts (EMG) | Physiological | High-frequency (20+ Hz) | Low-pass filter (e.g., 40-70 Hz); Careful to not remove neural gamma activity [17] |

| Motion Artifacts | Physical Movement | Broadband | Hardware solutions (e.g., microneedle sensors) [18]; Online digital filtering with segmented epochs [17] |

Experimental Protocols for Noise Mitigation

Protocol 1: Implementing Online Parity in Signal Filtering

This protocol ensures that the data processing steps used during offline analysis match those used during real-time, closed-loop BCI operation, which is crucial for generalizable performance [17].

- Data Acquisition: Record EEG data during your BCI paradigm (e.g., P300 speller task).

- Online Simulation (Segmented Filtering): Instead of filtering the entire continuous dataset, break the data into short epochs (e.g., 1-second segments following a stimulus). Apply your chosen digital filter (e.g., a 0.1-30 Hz bandpass filter) to each of these individual segments.

- Model Training: Train your classification model (e.g., for P300 detection) using features extracted from these segmented-and-filtered epochs.

- Online Application: During real-time BCI use, apply the exact same filtering process to the incoming, real-time data streams segmented into the same epoch length.

This method has shown significant benefits to model performance compared to conventional offline filtering of the entire dataset [17].

Protocol 2: Regularized CSP with SPEA-II for Optimal Channel Selection

This protocol reduces the number of EEG channels, which minimizes setup time, improves user comfort, and, crucially, enhances the SNR by eliminating noisy or redundant channels for Motor Imagery (MI) tasks [19].

- Data Collection: Collect multi-channel EEG data from a subject performing MI tasks (e.g., left-hand vs. right-hand movement imagery).

- Feature Extraction: Apply Regularized Common Spatial Patterns (RCSP) to the data from all channels to extract features that maximize the variance between the two MI classes.

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Use the Strength Pareto Evolutionary Algorithm II (SPEA-II) to find the optimal subset of channels. The algorithm evaluates different channel subsets based on two objectives: a) maximizing classification accuracy and b) minimizing the number of channels used.

- Model Training & Validation: Train a classifier (e.g., SVM, LDA) using the features from the optimal channel subset identified by SPEA-II. Validate the performance on a separate test set. This approach has been demonstrated to optimize performance in MI-based BCI systems by effectively managing noise and redundancy [19].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Algorithms for Noise-Resilient BCI Research

| Item / Solution | Function in BCI Research | Relevance to Noise Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Gel/Paste | Establishes a low-impedance electrical connection between the scalp and electrode [10]. | Directly addresses hardware-level noise from poor skin-contact. |

| Active Electrodes | Incorporate a miniature amplifier within the electrode itself to boost the signal at the source. | Reduces environmental interference picked up along the cable to the main amplifier. |

| Impedance Checker | A tool (often built into modern amplifiers) to measure the electrical impedance at each electrode site. | Critical for diagnosing hardware noise and ensuring balanced impedances for noise cancellation. |

| Wearable Microneedle BCI Sensor | A sensor that slightly penetrates the skin, avoiding hair follicles [18]. | Directly tackles hardware and motion artifacts by providing a stable, high-fidelity interface. |

| Regularized CSP (RCSP) | A feature extraction algorithm for discriminating between different Motor Imagery tasks [19]. | Improves signal separability, making the classifier more robust to noise. |

| SPEA-II Algorithm | A multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for selecting an optimal subset of EEG channels [19]. | Removes noisy or redundant channels, thereby improving the overall SNR for the system. |

| Online Digital Filtering | A processing technique where filters are applied to short, real-time data segments [17]. | Maintains "online parity," ensuring noise removal is consistent and effective during actual BCI use. |

The Impact of Low SNR on Information Transfer Rate (ITR) and System Performance

FAQs: Understanding SNR and ITR in Non-Invasive BCI

What is Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) in the context of non-invasive BCI? Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is a metric, often expressed in decibels (dB), that quantifies the strength of a desired neural signal relative to the background noise. In non-invasive BCI systems like electroencephalography (EEG), a high SNR means the brain signals of interest (such as SSVEPs or ERDs) are clear and distinct from noise, enabling more accurate decoding. A low SNR indicates that the system struggles to distinguish the neural signal from noise, leading to degraded BCI performance and reliability [20].

How does low SNR directly impact the Information Transfer Rate (ITR)?

Low SNR directly reduces the Information Transfer Rate (ITR), a key metric for BCI communication speed measured in bits per minute (bpm). The mathematical relationship between classification accuracy (P), the number of possible choices (N), and the selection time per character (T) is given by the ITR formula [21]:

Since classification accuracy (P) drops significantly with low SNR, the ITR decreases accordingly. For instance, one study noted that classification accuracy below 80% substantially hinders free communication, directly reducing the practical ITR a user can achieve [21].

What are the most common sources of noise degrading SNR in non-invasive BCI? The common sources of noise that degrade SNR in non-invasive BCI include [22]:

- Biological Artifacts: Electrical activity from eye movements (EOG), muscle contractions (EMG), and heart rhythms (ECG).

- Environmental Noise: Electromagnetic interference (EMI) from power lines, fluorescent lighting, motors, or other electronic equipment [20].

- Improper Setup: Dirty or damaged electrodes and connectors, incorrect application of conductive gel, and using the wrong type of electrodes (e.g., dry vs. gel-based) can introduce significant signal loss and noise [22] [20].

- Inherent Physiological Limitations: Non-invasive signals like EEG measure the average activity of neurons from the scalp. The signal is attenuated and spatially blurred as it passes through the cerebrospinal fluid, skull, and scalp, which is an intrinsic cause of lower SNR compared to invasive methods [1] [23].

Why is achieving a high ITR in a real-world "free communication" scenario more difficult than in a cued lab experiment? Cued lab experiments (e.g., repetitively typing "HIGH SPEED BCI") simplify the user's cognitive task and minimize eye movements, which helps maintain a stable SNR. In contrast, genuine free communication involves the continuous generation of novel thoughts, spelling unfamiliar words, and locating characters on a keyboard. This increased cognitive load and visual scanning can introduce more neural "noise" and variability, which reduces classification accuracy and, consequently, the achieved ITR [21].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Low SNR to Improve ITR

Follow this systematic guide to identify and resolve common issues that cause low SNR.

Step 1: Verify Signal Acquisition Integrity

Begin by inspecting the physical setup of your BCI system.

- Action: Visually inspect and clean all electrodes and connectors. Ensure electrodes are properly seated with good electrical contact. For gel-based systems, check that the conductive gel is correctly applied. For research systems using fiber optics, ensure connectors are clean and undamaged [20].

- Rationale: Dirty or poorly connected electrodes are a primary cause of signal loss and increased noise [20].

Step 2: Check for Environmental Interference

- Action: Identify and isolate the system from potential sources of electromagnetic interference (EMI), such as power cables, fluorescent lights, and unshielded electrical equipment [20].

- Rationale: EMI can be inductively or capacitively coupled into the recording equipment, corrupting the neural signal with high-frequency noise.

Step 3: Optimize Experimental and Signal Processing Parameters

If the hardware and environment are correct, optimize your experimental paradigm and processing chain.

The following table summarizes parameter adjustments to enhance SNR and ITR, supported by recent research:

| Parameter | Low SNR/ITR Approach | High SNR/ITR Approach | Experimental Support & Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulation Frequency | Using limited or traditional frequency bands (e.g., 8-15 Hz for SSVEP). | Implementing a broadband white noise stimulus across a wider frequency spectrum [24]. | A 2024 study demonstrated that a broadband BCI outperformed a standard SSVEP BCI by 7 bps, achieving a record 50 bps ITR by improving the channel's spectral resources [24]. |

| Stimulation Duration | Very short trial durations (e.g., 0.5-1.0 s). | Moderately longer trial durations (e.g., 1.5 s) combined with a flicker-free period (0.75 s) [21]. | Longer durations allow the SSVEP response to build up, increasing SNR. A flicker-free period reduces user fatigue, indirectly supporting sustained attention and signal quality [21]. |

| Classification Algorithm | Using standard Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA). | Employing Filter-Bank CCA and incorporating individualized template optimization [21]. | These advanced methods improve the discrimination between target and non-target signals, boosting classification accuracy (P in the ITR equation) even at lower SNRs [21]. |

| User Training & Paradigm | Testing only on cued, repetitive phrases with experienced users. | Evaluating systems with naïve users in genuine free communication tasks [21]. | This reveals the true cognitive load and performance under realistic conditions. Providing real-time character feedback can improve usability and help users maintain better control [21]. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating SNR Improvements using a Broadband BCI Paradigm

Objective: To empirically demonstrate that a broadband visual stimulus can surpass the ITR of traditional Steady-State Visual Evoked Potential (SSVEP) BCIs by improving the SNR in the frequency domain [24].

Methodology:

- Stimulus Design:

- Control Condition: Use a conventional SSVEP speller with stimuli flickering at specific, discrete frequencies.

- Experimental Condition: Implement a broadband "white noise" stimulus where the visual flicker's intensity changes randomly according to a white noise sequence, stimulating a broader range of frequencies [24].

- Information Theory Analysis:

- Use information theory to estimate the upper and lower bounds of the information rate for the white noise stimulus. The key is to analyze the SNR in the frequency domain, which reflects the available spectrum resources of the visual-evoked channel [24].

- Signal Decoding:

Expected Outcome: The broadband BCI paradigm is expected to yield a significantly higher ITR (as demonstrated by a 7 bps increase, reaching 50 bps) compared to the SSVEP BCI, validating that optimizing the stimulus spectrum is an effective strategy to overcome low SNR limitations [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key computational and experimental "reagents" essential for modern non-invasive BCI research focused on overcoming low SNR.

| Research Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Filter-Bank CCA | A signal processing algorithm that decomposes the EEG signal into multiple sub-bands. It enhances the detection of SSVEPs by leveraging harmonic components, thereby improving classification accuracy and ITR [21]. |

| Transfer Learning (TL) | A machine learning technique that uses data from previous subjects or sessions to reduce the calibration time for a new user. This addresses the high variability in neural signals across individuals, a major source of effective "noise" [25] [15]. |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | A class of deep learning models adept at automatically learning optimal spatial and spectral features from raw or preprocessed EEG signals, reducing the reliance on hand-crafted features that may be sensitive to noise [25] [15]. |

| Dry EEG Electrodes | Electrodes that make direct contact with the scalp without conductive gel. They offer a trade-off: faster setup improves practicality but can sometimes result in higher impedance and susceptibility to motion artifacts compared to wet electrodes [22]. |

| High-Density EEG Montages | Arrays with a large number of electrodes (e.g., 64, 128, or 256) placed according to the international 10-20 system. This allows for sophisticated source localization and noise cancellation through spatial filtering [22]. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical pathway from low SNR to its ultimate impact on system performance, and the corresponding optimization strategies.

SNR Impact and Optimization Pathway

This workflow maps the critical steps for diagnosing and resolving low SNR issues. The red nodes indicate problems, while the green nodes represent the corresponding solutions. Implementing the optimization strategies directly counteracts the negative cascade that leads to poor system performance.

Technical Comparison of BCI Signal Acquisition Modalities

The core challenge in selecting a Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) methodology involves balancing signal fidelity against practical and clinical risks. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of key signal acquisition technologies.

Table 1: Technical Specifications of BCI Signal Acquisition Methods

| Feature | EEG (Non-Invasive) | MEG (Non-Invasive) | fNIRS (Non-Invasive) | ECoG (Minimally-Invasive) | Intracortical Recording (Invasive) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | ~10 mm [26] | ~5 mm [26] | ~5 mm [26] | ~1 mm [26] | ~0.05-0.5 mm [26] |

| Temporal Resolution | ~0.05 s [26] | ~0.05 s [26] | ~1 s [26] | ~0.003 s [26] | ~0.003 s [26] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Low [27] | Acceptable | Low (Slow, metabolic) [26] | High [1] [26] | Very High [26] |

| Invasiveness & Risk | Non-Invasive, Safe [10] [28] | Non-Invasive, No Surgical Risk [28] | Non-Invasive, Minimal Risk [28] | Invasive, Surgical Risks [28] [29] | Invasive, Highest Surgical Risks [28] [29] |

| Key Signal Source | Scalp potentials from post-synaptic currents [23] | Magnetic fields from neuronal activity [28] | Hemodynamic response (Hb concentration) [28] | Cortical surface potentials [1] [28] | Local Field Potentials (LFP) & Action Potentials (AP) [23] [26] |

| Primary Limitations | Sensitive to noise/artifacts, low spatial resolution [10] [28] | Bulky equipment, high cost, limited portability [28] [26] | Low temporal resolution, limited penetration depth [28] | Limited coverage, requires surgery [1] | Tissue response, signal stability over time [1] [29] |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Signal Fidelity Challenges

FAQ 1: What are the fundamental neurophysiological reasons for the lower signal quality in non-invasive BCIs like EEG compared to invasive methods?

The lower signal quality stems from several intrinsic physical and biological barriers:

- Signal Attenuation and Distortion: The skull and other tissues between the brain and scalp electrodes act as a low-pass filter, severely attenuating high-frequency neural signals and burying them in background noise [23]. These tissues also have varying electrophysiological properties, causing significant spatial distortion of the electric fields before they reach the scalp [23].

- Neuronal Source Requirements: For the microvolt-level electrical fields to reach the scalp, a massive number of neurons (pyramidal neurons) must be activated synchronously in a confined area [23]. This means non-invasive EEG largely misses the activity of small, specialized neuronal clusters that invasive methods can detect.

- Limited Information Content: Non-invasive signals are predominantly restricted to lower frequency bands (<90 Hz) and are dominated by a specific type of neuronal activity (post-synaptic potentials), whereas invasive methods can capture the full spectrum of brain signals, including high-frequency action potentials and local field potentials that carry rich information about local processing and output [23].

FAQ 2: What specific signal processing techniques can help overcome the low Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) in non-invasive Motor Imagery (MI)-BCI systems?

Overcoming low SNR is a multi-stage process involving advanced algorithmic approaches:

- Spatial Filtering: Use algorithms like Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) to maximize the variance of the EEG signal for one class (e.g., left-hand imagery) while minimizing it for the other, effectively enhancing the discriminability of MI tasks [30].

- Deep Learning (DL) Models: Employ Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for their ability to perform end-to-end learning from raw or pre-processed EEG data, automatically extracting relevant spatio-temporal features. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are particularly effective for decoding the time-series nature of EEG signals [30].

- Data Augmentation: Combat limited dataset sizes and overfitting by artificially expanding your training data. Techniques include:

- Adding Gaussian noise to original signals.

- Cropping and Segmentation/Recombination (S&R) of trials in the time domain.

- Window Warping to expand or contract random windows of data [30].

- Transfer Learning (TL): To address the high inter-subject variability that necessitates frequent recalibration, use TL to adapt a model pre-trained on a large group of subjects to a new individual, significantly reducing training time and data requirements [15] [30].

FAQ 3: Are there any emerging hardware technologies that aim to bridge the gap between non-invasive and invasive signal quality?

Yes, recent research focuses on developing novel sensors that improve signal acquisition at the hardware level:

- Wearable Microneedle Sensors: Researchers at Georgia Tech have developed a painless, wearable wireless microneedle BCI sensor. The micro-needles slightly penetrate the skin, bringing the electrodes closer to the neural signal source and avoiding the hair follicle interference that plagues traditional scalp EEG. This design achieves higher-fidelity signals and stable recording over many hours, even during user movement, marking a significant step toward practical daily BCI use [18].

Experimental Protocol: Motor Imagery (MI) Workflow for Non-Invasive BCI

This protocol outlines a standard procedure for conducting an EEG-based MI-BCI experiment, from setup to data analysis.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for a standard MI-BCI protocol.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Subject Preparation & Hardware Setup

- Fit the subject with an EEG cap following the international 10-20 system for electrode placement [10].

- Apply conductive electrode gel to achieve and maintain impedance below 5 kΩ throughout the experiment to ensure high-quality signal acquisition [18].

- Configure the EEG amplifier settings (e.g., sampling rate typically at 250 Hz or higher, appropriate band-pass filter).

Experimental Paradigm Design

- Use a cue-based paradigm. Present visual cues on a screen instructing the subject to perform kinesthetic motor imagery (e.g., imagining left-hand vs. right-hand movement without any physical motion).

- Each trial should consist of: (1) a fixation cross, (2) a visual cue indicating the task, (3) the MI period, and (4) a rest period. Randomize the order of cues.

Signal Preprocessing

- Filtering: Apply a band-pass filter (e.g., 8-30 Hz) to isolate the mu and beta rhythms, which are most relevant for MI [30].

- Artifact Removal: Use algorithms like Independent Component Analysis (ICA) to identify and remove artifacts from eye blinks, eye movements, and muscle activity.

Feature Extraction & Classification

- Feature Extraction: Apply the Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) algorithm to the preprocessed EEG epochs. CSP finds spatial filters that maximize the variance of the signals from one class while minimizing the variance from the other, providing highly discriminative features [30].

- Feature Classification: Feed the CSP features into a classifier. For initial studies, a Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) or Support Vector Machine (SVM) is recommended due to their simplicity and robustness. For more complex patterns, a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) can be used [15] [30].

Online Testing & Feedback

- Using the trained model, run an online session where the subject's brain signals are processed and classified in real-time.

- Provide immediate performance feedback to the subject, for example, by moving a cursor on a screen or controlling a simple game. This closed-loop feedback is critical for user learning and engagement [15] [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for BCI Research

| Item/Tool | Function/Purpose | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density EEG Cap | Records electrical brain activity from the scalp using multiple electrodes (e.g., 64, 128 channels). | Primary sensor for non-invasive signal acquisition in MI, P300, and SSVEP paradigms [10] [30]. |

| Conductive Electrode Gel | Improves electrical contact between scalp and electrodes, reducing impedance and improving signal quality. | Applied during EEG cap setup to ensure high-fidelity signal acquisition; crucial for gel-based systems [18]. |

| Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) | A spatial filtering algorithm that optimizes the discrimination between two classes of EEG signals. | Extracting features from multi-channel EEG data during motor imagery tasks (e.g., left vs. right hand) [30]. |

| OpenBCI/BCI2000 Software | Open-source software platforms for BCI data acquisition, stimulus presentation, and protocol design. | Providing a standardized, accessible framework for developing and testing BCI experiments [1]. |

| Transfer Learning (TL) Toolboxes | Machine learning tools that adapt pre-trained models to new subjects, reducing calibration time. | Addressing the challenge of high inter-subject variability in EEG signals, enabling faster subject-specific model training [15] [30]. |

| Wearable Microneedle Sensors | Novel dry electrodes that minimally penetrate the skin for higher SNR and long-term stability. | Enabling high-fidelity, mobile EEG recording for BCIs outside the lab environment; a emerging hardware solution [18]. |

Advanced Signal Acquisition and Processing Methodologies for Enhanced Fidelity

Electrode Performance Comparison

The core challenge in non-invasive Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) research is overcoming the low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The choice of electrode technology directly impacts signal quality. The table below compares the key characteristics of different EEG electrode types.

Table 1: Comparison of Non-Invasive EEG Electrode Types

| Electrode Type | Contact Medium | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Contact Impedance | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Electrodes [31] | Electrolyte gel (e.g., NaCl) | Stable, low impedance, high-quality signal gold standard [31] | Long setup time, gel dries out, skin irritation, messy [31] | < 10 kΩ (with gel) [31] | Laboratory research requiring the highest signal quality [31] |

| Dry Electrodes [31] | Direct metal/solid contact (no gel) | Quick setup, no skin preparation, long-term use, user-friendly [31] | Higher impedance, more susceptible to motion artifacts [31] | Can be > 100 kΩ [31] | Rapid, mobile BCI applications and consumer products [31] |

| Semi-Dry Electrodes [31] | Minimal liquid (e.g., from a reservoir) | Compromise between wet and dry; lower impedance than dry, less messy than wet [31] | Liquid may still dry out or cause irritation; more complex design [31] | Lower than dry electrodes [31] | Applications requiring good signal quality with faster setup than wet electrodes [31] |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

This section addresses common experimental issues related to electrode use and signal quality.

FAQ 1: Why is my EEG signal consistently noisy, and how can I improve the SNR?

- Problem: A consistently low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) makes it difficult to isolate neural signals of interest.

- Solution:

- Verify Electrode-Skin Impedance: High impedance is a primary cause of noise. Ensure impedance is below 10 kΩ for wet electrodes and as low as achievable for dry electrodes. Reapply conductive gel or adjust electrode placement if necessary [31].

- Check for Proper Grounding: A faulty ground electrode can introduce 50/60 Hz line noise and other environmental interference into all recording channels. Ensure your ground electrode has a stable, low-impedance connection [31].

- Control Environmental Noise: Perform experiments in a shielded room, if possible, and keep cables away from power sources and monitors to reduce electromagnetic interference [31].

- Consider Advanced Materials: For dry electrodes, explore designs using highly conductive and biocompatible materials like graphene or polymer-based composites, which can offer a better trade-off between impedance and usability [31].

FAQ 2: My dry electrodes show unstable signals and are sensitive to motion. What can I do?

- Problem: Dry electrodes are prone to motion artifacts and signal instability due to poor mechanical contact with the scalp.

- Solution:

- Optimize Mechanical Design: Use electrodes with flexible, spring-loaded, or finger-like structures that can maintain consistent pressure and adapt to scalp and hair movement [31].

- Implement Signal Processing: Apply advanced artifact removal algorithms in real-time, such as Adaptive Filtering or Independent Component Analysis (ICA), to identify and subtract motion-related signal components [26].

- Ensure Proper Fit: Use a cap or headset with a tight but comfortable fit to minimize relative movement between the electrodes and the scalp.

FAQ 3: How can I achieve higher spatial resolution for more precise brain signal mapping?

- Problem: Standard low-density electrode arrays (e.g., 32-64 channels) provide limited spatial resolution.

- Solution:

- Adopt High-Density Arrays: Move to high-density EEG (HD-EEG) systems with 128, 256, or more channels. This provides superior spatial sampling for more accurate source localization of brain activity [32].

- Utilize Flexible MEAs: Flexible High-Density Microelectrode Arrays (FHD-MEAs) offer mechanical compliance, improved long-term biocompatibility, and stable contact, enabling high-resolution neural recording [32].

- Explore Novel Signals: Investigate emerging non-invasive technologies like Digital Holographic Imaging (DHI), which can detect nanometer-scale tissue deformations associated with neural activity, potentially offering a new high-resolution signal source [2].

Experimental Protocols for Electrode Validation

Protocol 1: Validating Electrode Performance and Signal Quality

This protocol provides a methodology for quantitatively comparing the performance of different electrode types in a controlled setting.

Diagram: Electrode Validation Workflow

- Objective: To systematically evaluate and compare the signal quality and performance of wet, dry, and semi-dry EEG electrodes.

- Materials:

- EEG acquisition system with multiple channels.

- Different electrode types (wet, dry, semi-dry) to be tested.

- Conductive gel and skin preparation supplies (abrasive gel, alcohol wipes).

- A standardized headcap or holder that allows for consistent placement of different electrode types.

- A computer with a monitor for visual stimulus presentation.

- Data analysis software (e.g., MATLAB, Python with MNE, BrainVision Analyzer [33]).

- Procedure:

- Subject & Setup Preparation: Recruit subjects following ethical guidelines. Explain the experiment and obtain informed consent. Set up the EEG system according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Electrode Application & Impedance Check: Apply the different electrode types to the subject's scalp according to the international 10-20 system (e.g., at positions C3, C4, Pz). For wet electrodes, prepare the skin and apply gel. Measure and record the initial contact impedance for every electrode. The target for wet electrodes is typically < 10 kΩ [31].

- Data Acquisition Protocol: Record EEG data under the following conditions:

- Resting State: 5 minutes with eyes open and 5 minutes with eyes closed. . Event-Related Potentials (ERPs): Present a visual P300 oddball paradigm. This involves displaying a series of frequent (non-target) and rare (target) stimuli on a screen. Instruct the subject to mentally count the target stimuli. . Motor Imagery (MI): Instruct the subject to imagine moving their right hand or left hand in response to a visual cue, following a standard timing protocol.

- Signal Analysis & Metric Calculation: For each condition and electrode type, calculate the following quantitative metrics [31] [26]:

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): Calculate as the ratio of the power of the neural signal (e.g., alpha band during eyes closed) to the power of the noise (e.g., during a pre-stimulus baseline).

- Noise Amplitude: Measure the root mean square (RMS) of the signal during a resting baseline period.

- ERP Amplitude/Latency: For the P300 paradigm, measure the peak amplitude and latency of the P300 component at the Pz electrode. . Task Classification Accuracy: For the MI data, use a machine learning classifier (e.g., Linear Discriminant Analysis) to decode left vs. right hand imagery and report the cross-validated accuracy.

- Statistical Comparison: Perform statistical tests (e.g., repeated-measures ANOVA) to determine if there are significant differences in the calculated metrics (SNR, P300 amplitude, classification accuracy) between the different electrode types.

Protocol 2: Testing a Novel Non-Invasive Signal Source

This protocol outlines the methodology for experimenting with a cutting-edge signal modality, as demonstrated by Johns Hopkins APL [2].

Diagram: Novel Signal Acquisition Setup

- Objective: To detect and validate neural activity through non-invasive recording of associated neural tissue deformations using a Digital Holographic Imaging (DHI) system [2].

- Materials:

- Digital Holographic Imaging system (including a laser source, specialized camera, and processing unit).

- (Note: This protocol is based on a laboratory setup and may not be immediately feasible for all researchers due to the specialized equipment required.)

- Procedure:

- System Calibration: Calibrate the DHI system for nanometer-scale sensitivity. This involves ensuring the laser and camera are aligned to precisely measure the phase of the scattered light, which is affected by tiny tissue movements [2].

- Signal Acquisition: Position the laser to illuminate the subject's scalp over the primary motor cortex. Record the scattered light with the camera while the subject performs a motor task (e.g., finger tapping) or motor imagery.

- Clutter Mitigation: The primary challenge is separating the neural signal from physiological "clutter" like blood flow and respiration. Use signal processing techniques to filter out these known noise sources based on their characteristic frequencies [2].

- Signal Validation: Correlate the extracted tissue deformation signal with the onset and offset of the motor task. Simultaneous recording with a validated method like EEG or fMRI can be used to confirm that the detected signal is temporally correlated with neural activity [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for Next-Generation BCI Electrode Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Key Characteristics & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Electrolyte Gels [31] | Establishes electrical connection for wet electrodes; reduces skin-electrode impedance. | NaCl-based, chloride-based; must be non-irritating and have stable conductivity [31]. |

| Flexible Substrate Materials [32] | Base material for flexible MEAs and comfortable dry electrodes; improves long-term wearability and contact. | Soft polymers like PDMS, polyimide; biocompatible; allow for conformal contact with the scalp [31] [32]. |

| Advanced Conductive Coatings [31] [32] | Coating for dry electrodes to enhance charge transfer and lower contact impedance. | Materials like graphene, CNTs (Carbon Nanotubes), PEDOT:PSS; offer high conductivity and biocompatibility [31]. |

| High-Density EEG Caps | Holds a large number of electrodes (128-256+) for high spatial resolution mapping. | Durable, precisely mapped according to 10-10/10-5 systems; often use Ag/AgCl sintered electrodes [32]. |

| Digital Holographic Imaging System [2] | A novel non-invasive system for detecting neural activity via nanometer-scale tissue deformations. | Includes laser, specialized camera; measures changes in scattered light phase; high spatial resolution potential [2]. |

Leveraging Machine Learning and Deep Learning for Noise Filtering and Feature Extraction

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most effective deep learning architectures for removing noise and artifacts from non-invasive BCI data? Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are highly effective for this task. Architectures like EEGNet are specifically optimized for EEG-based BCI systems, automatically learning hierarchical representations from raw signals to isolate neural patterns from noise [34] [35]. For handling temporal dependencies and non-stationary data, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) or Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks are often employed [35]. Furthermore, hybrid models that combine a CNN with a Kalman filter (CNN-KF) have demonstrated a significant performance boost, improving task performance by a factor of nearly 4 times in some real-time control experiments by effectively filtering noisy time-series data [36].

Q2: Our BCI system's performance drops with new users. How can we reduce calibration time? Transfer Learning (TL) is the primary technique to address this. It allows a model pre-trained on a large dataset from multiple subjects to be rapidly fine-tuned with a minimal amount of data from a new user [25]. For instance, one protocol involves training a base model on an initial session, then fine-tuning it with same-day data from a new user, which has been shown to significantly enhance task performance across sessions [34]. Domain adaptation networks, such as those used for SSVEP, can transform source user data to align with a new user's signal template, drastically reducing calibration needs [35].

Q3: Which feature extraction methods work best for decoding motor imagery? The Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) algorithm is a classic and powerful method for feature extraction in motor imagery paradigms, as it maximizes the variance between two classes of signals [37] [35]. For more nuanced tasks, such as individual finger movement decoding, time-frequency analysis using wavelet transforms is highly effective [37] [34]. With the advancement of deep learning, end-to-end models that perform automatic feature extraction from raw or minimally pre-processed EEG signals are increasingly demonstrating superior performance, eliminating the need for manual feature engineering [34] [25].

Q4: How can we improve the real-time performance of our BCI decoding pipeline? Implementing adaptive filtering techniques, such as the Recursive Least Squares algorithm, can robustly denoise signals in real-time [35]. Leveraging edge computing platforms allows for powerful on-device signal processing, reducing latency [38]. Additionally, applying online smoothing algorithms to the decoder's output can stabilize control signals, making the real-time operation more robust and reliable [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Classification Accuracy Despite Strong Raw Signals

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Inadequate Pre-processing:

- Cause: Residual noise from eye movements (EOG), muscle activity (EMG), or power line interference is confounding the classifier.

- Solution: Implement a robust pre-processing pipeline. Use band-pass and notch filtering to isolate relevant frequency bands and remove line noise. Follow this with Independent Component Analysis (ICA) to identify and remove stereotypical artifact components [37] [35].

Non-Stationary EEG Signals:

- Cause: Brain signals change over time due to user fatigue, learning, or changes in attention, causing a model trained on initial data to become obsolete.

- Solution: Employ adaptive classification algorithms. These models can update their parameters in a closed-loop system during use. Utilizing error-related potentials as feedback for reinforcement learning agents is a cutting-edge approach to maintain system accuracy [35].

Suboptimal Feature Set:

- Cause: The manually selected features do not adequately capture the discriminative information in the signal for the specific task or user.

- Solution: Transition to a deep learning-based approach. Models like EEGNet can learn the most informative spatiotemporal features directly from the data, often leading to higher accuracy than traditional methods [34].

Problem: High Latency in Real-Time Control Systems

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Computationally Expensive Feature Extraction:

- Cause: Time-frequency decompositions (e.g., wavelets) or other complex feature calculations are creating a bottleneck.

- Solution: Simplify the feature space or adopt an end-to-end deep learning model that operates on raw data. Alternatively, optimize code and leverage GPU acceleration for faster computation [34].

Inefficient Model Architecture:

- Cause: The machine learning model is too large or complex for the hardware.

- Solution: Use models optimized for embedded and real-time use, such as the lightweight EEGNet architecture. Consider model pruning or quantization to reduce computational load without significantly sacrificing performance [34].

Lack of an AI Copilot:

- Cause: The BCI is relying solely on the noisy neural decode for every aspect of control.

- Solution: Implement a shared autonomy model. An AI copilot can interpret the user's high-level intent from the neural signals and handle the low-level details of device control, drastically improving speed and accuracy. This has been shown to enable paralyzed users to perform tasks that were otherwise impossible [36].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: CNN-KF with AI Copilot for Real-Time Control

This protocol is based on a UCLA study that significantly improved BCI performance for cursor and robotic arm control [36].

1. Objective: To achieve high-performance, real-time control of an external device using a non-invasive BCI enhanced by an AI copilot.

2. Methodology Summary:

- Signal Acquisition: Record EEG from a 64-channel cap.

- Pre-processing: Apply standard band-pass filtering and artifact removal.

- Decoding: Use a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to decode the user's intended movement from the EEG signals.

- Filtering: A Kalman Filter (KF) is used to smooth the CNN's output, providing a stable estimate of the user's intent from the noisy time-series data.

- AI Copilot: A second AI module uses task structure and environmental observations (e.g., target locations) to "collaborate" with the user, changing the distribution of actions to achieve the goal more efficiently.

3. Key Workflow Diagram:

Protocol 2: Deep Learning for Individual Finger Movement Decoding

This protocol, derived from a study in Nature Communications, enables real-time robotic hand control at the individual finger level [34].

1. Objective: To decode and classify movement execution (ME) and motor imagery (MI) of individual fingers from EEG signals for dexterous robotic control.

2. Methodology Summary:

- Paradigm: Participants execute or imagine movements of individual fingers (thumb, index, pinky) on their dominant hand.

- Model: Use the EEGNet-8,2 architecture for real-time decoding.

- Training & Fine-tuning:

- Train a subject-specific base model on data from an initial offline session.

- In subsequent online sessions, collect new data and use it to fine-tune the base model, mitigating inter-session variability.

- Feedback: Provide users with both visual (on-screen) and physical (robotic hand movement) feedback.

3. Key Workflow Diagram:

The following table quantifies the performance of various ML/DL techniques as reported in recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Advanced BCI Decoding Models

| Model / Technique | Application / Paradigm | Reported Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNN-KF with AI Copilot | Cursor & robotic arm control | 3.9x performance improvement for a paralyzed participant; tasks impossible without AI copilot. | [36] |

| EEGNet with Fine-Tuning | Individual finger MI (2-finger task) | Real-time decoding accuracy of 80.56%. | [34] |

| EEGNet with Fine-Tuning | Individual finger MI (3-finger task) | Real-time decoding accuracy of 60.61%. | [34] |

| LSTM-CNN-RF Ensemble | Hybrid prosthetic arm control (BRAVE system) | Achieved high decoding accuracy of 96%. | [35] |

| POMDP-based Model | RSVP typing communication | Symbol recognition accuracy of >85%. | [35] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for BCI Experimentation

| Item / Technique | Function / Purpose | Example in Use |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density EEG Systems | Captures brain electrical activity with high temporal resolution. Essential for source localization of fine motor commands. | 64-channel caps used for decoding individual finger movements [34]. |

| Dry EEG Sensors | Increases portability and user comfort by eliminating the need for electrolytic gel. Key for practical, long-term use. | Implemented in commercial headsets like Synaptrix's "Neuralis" for wheelchair navigation [38]. |

| Digital Holographic Imaging (DHI) | A breakthrough non-invasive method that detects nanometer-scale tissue deformations from neural activity, offering a potential new signal source. | Johns Hopkins APL used DHI to identify a novel neural signal through the scalp and skull [2]. |

| EEGNet Architecture | A compact convolutional neural network specifically designed for EEG-based BCIs. Balances performance with computational efficiency. | Used as the core decoder for real-time finger movement classification [34]. |

| Transfer Learning (TL) | Adapts a pre-trained model to a new subject with minimal calibration data, solving the problem of inter-user variability. | Fine-tuning a base EEGNet model with a small amount of same-day data to boost online performance [34] [25]. |

| Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) | A spatial filtering algorithm optimal for distinguishing two classes of motor imagery (e.g., left vs. right hand). | A standard technique for feature extraction in motor imagery paradigms before classification [35]. |

Motor Imagery Paradigms and ERD/ERS Analysis for Robust Control Signals

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: Why is my Motor Imagery (MI) classification accuracy low, and how can I improve it?

- Potential Cause: The most common issue is a low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in the Event-Related Desynchronization (ERD) and Event-Related Synchronization (ERS) patterns. This can be due to suboptimal frequency band selection, inadequate user training, or contamination by artifacts.

- Solution:

- Optimize Frequency Bands: Do not rely on a standard frequency range for all subjects. The reactive frequencies in the mu (8-12 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) bands can vary significantly between individuals [39] [40]. Implement a subject-specific band selection protocol by analyzing the power spectrum density during a resting state and during motor imagery to identify the most responsive frequencies.

- Employ Advanced Feature Extraction: Move beyond simple band power features. Consider using a filter bank approach, which applies multiple narrower bandpass filters (e.g., 4-8 Hz, 8-12 Hz, 12-16 Hz, etc.). This allows the classifier to determine which frequency bands are most discriminative for the specific user, thereby improving performance [40].

- Utilize Transfer Learning: If the user is a low performer or finds MI difficult, consider using a transfer learning approach. Research shows that a classification model trained on data from Motor Execution (ME) can achieve statistically similar accuracy on MI tasks. Combining a small amount of a user's MI data with ME data from other subjects can significantly boost performance, especially for users with initial accuracy below 70% [41].

FAQ 2: The ERD/ERS patterns for my ALS patient participants are weak or delayed. Is this normal?

- Potential Cause: Yes, this is a documented neuropathological effect of ALS. Studies have quantified that ALS patients often exhibit reduced and delayed ERD during motor imagery tasks compared to age-matched healthy controls. This is particularly pronounced during right-hand MI [39].

- Solution:

- Adjust Expectations and Protocols: Account for these abnormalities in your experimental design. The magnitude and timing of sensorimotor oscillations are valid cortical markers of the disease and should not be solely interpreted as poor task performance.

- Correlate with Clinical Scores: These weakened ERD features have been shown to correlate with clinical scores, including disease duration, bulbar function, and cognitive scores [39]. Quantifying these relationships can be part of your analysis rather than a problem to be solved.

- Ensure Proper Task Engagement: For patients with advanced ALS and communication difficulties, use alternative methods like a P300 speller or eye-tracking systems to verify task understanding and engagement before and during the experiment [39].

FAQ 3: How can I reduce the long and tedious calibration time for a new BCI user?

- Potential Cause: The standard calibration phase requires users to perform numerous MI trials to collect enough data to train a subject-specific model. This is tiring and can lead to user frustration [41].

- Solution:

- Implement Task-to-Task Transfer Learning: As mentioned in FAQ 1, use data from easier tasks like Motor Execution (ME) or Motor Observation (MO) to pre-train your model. These tasks share similar neural mechanisms with MI but are less fatiguing and yield better initial data. You can then fine-tune this model with a small amount of the user's own MI data [41].

- Incorporate User-State Estimation: System performance can drop if the user is fatigued or not engaged. Implement a system that estimates the user's state (e.g., focused, resting) based on brain functional connectivity or other signals. This allows the BCI to pause or switch modes when the user is not in an optimal state, making training time more efficient [42].

- Use Predictive Screening: Some studies suggest that resting-state EEG metrics or heart rate variability can partially predict a user's future BCI performance [43]. This can help set realistic expectations and tailor the training protocol from the very beginning.

FAQ 4: My EEG signals are contaminated with noise. How can I ensure my ERD/ERS analysis is robust?

- Potential Cause: Non-invasive EEG is susceptible to various artifacts, including eye blinks (EOG), muscle activity (EMG), and line noise.

- Solution:

- Apply Robust Pre-processing: Always use artifact removal techniques. Common Average Referencing (CAR) can help reduce the effect of noise common to all electrodes [40].

- Leverage Time-Frequency Analysis: Instead of analyzing raw EEG traces, use time-frequency analysis (e.g., wavelet transform) to quantify ERD/ERS. This method is excellent for visualizing and capturing non-phase-locked oscillatory dynamics in specific frequency bands over time, making the signal of interest more robust against background noise [39].