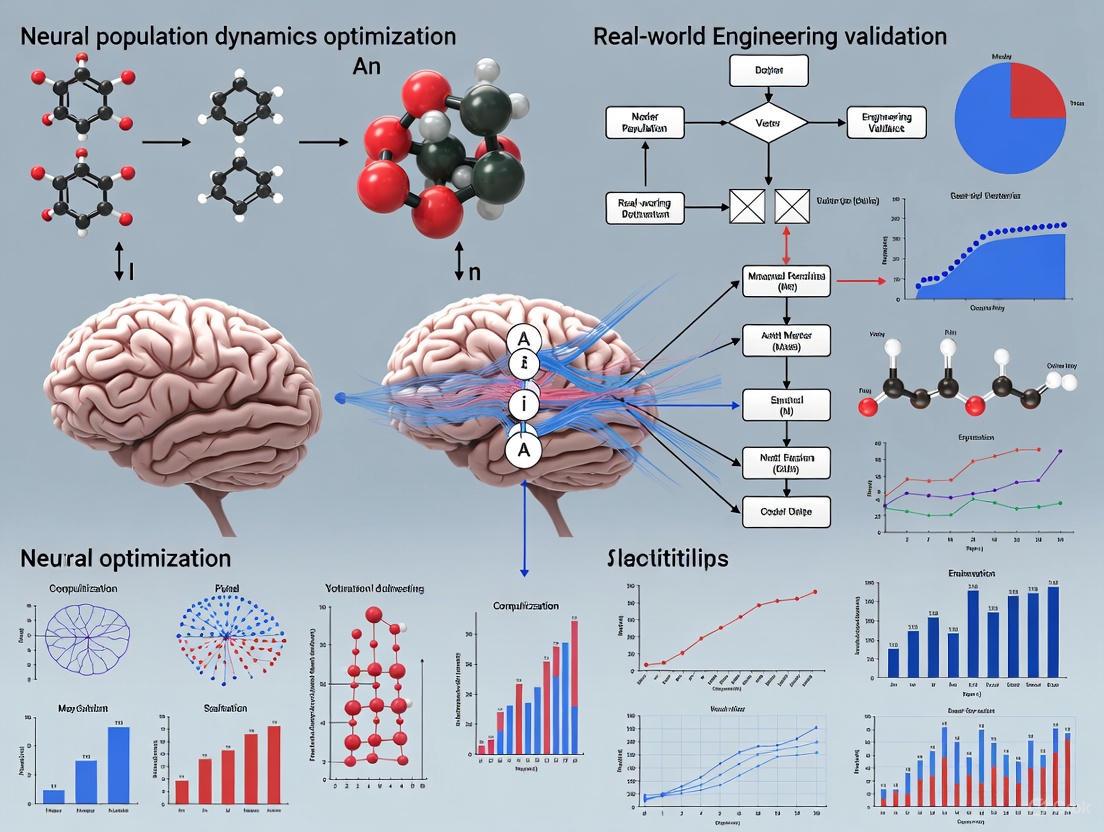

Optimizing Neural Population Dynamics: From Foundational Principles to Real-World Engineering Validation

This article synthesizes the latest advances in understanding, modeling, and optimizing neural population dynamics, with a focus on translating these computational principles into real-world biomedical applications.

Optimizing Neural Population Dynamics: From Foundational Principles to Real-World Engineering Validation

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest advances in understanding, modeling, and optimizing neural population dynamics, with a focus on translating these computational principles into real-world biomedical applications. We explore the foundational theory of how neural circuits generate constrained dynamics essential for cognition and motor control. The review then details cutting-edge methodologies for learning these dynamics from experimental data, including active learning frameworks and geometric deep learning. A dedicated section addresses central optimization challenges, such as overcoming dynamical constraints and designing efficient experiments. Finally, we critically evaluate strategies for the experimental validation of these models in clinical and pre-clinical settings, including brain-computer interfaces and novel perturbation paradigms. This synthesis provides researchers and drug development professionals with a roadmap for leveraging neural dynamics to develop next-generation diagnostics and therapies for neurological disorders.

The Biological Basis of Neural Dynamics: From Circuit Constraints to Computational Functions

Defining Neural Population Dynamics and Their Role in Brain Computation

Neural population dynamics describe the coordinated, time-varying activity of groups of neurons that underpin brain functions like motor control and decision-making. The field is advancing from observation to causal validation, with brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) now providing direct experimental evidence that these dynamics are fundamental to the brain's computational framework.

Theoretical Foundations and Computational Principles

Neural population dynamics are grounded in the concept that computation in the brain arises from the time evolution of activity patterns within neural networks [1]. This activity is not random; it follows structured trajectories shaped by the underlying neural circuitry, much like the flow fields described in computational network models [2] [1].

- Representational Geometry and Modularity: The structure of population activity can be characterized through two complementary lenses: representational geometry (the arrangement of population activity patterns in a high-dimensional state space) and modularity (the organization of neurons into functional groups with similar response properties) [3]. The alignment between these structures has specific computational implications, enabling functions like flexibility and generalization [3].

- The Role of Network Connectivity: In models, the specific time courses of activity are dictated by the network's connectivity [1]. A key prediction from this view is that these natural, stereotyped activity sequences are difficult to violate because doing so would effectively require altering the network itself [2] [1].

Comparative Analysis of Key Methodological Approaches

The following table compares the core methodologies used to investigate and validate neural population dynamics.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Methodologies in Neural Population Dynamics Research

| Methodology | Core Principle | Key Experimental Validation | Primary Findings | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCI-Based Causal Testing [2] [1] | Uses a brain-computer interface to challenge subjects to volitionally alter their native neural trajectories. | Monkeys were challenged to produce time-reversed neural trajectories in motor cortex. | Subjects were unable to violate natural neural trajectories, providing causal evidence they are constrained by the underlying network [1]. | Provides a direct, causal test of dynamical constraints; high interpretability. |

| Cross-Population Prioritized Linear Dynamical Modeling (CroP-LDM) [4] | A computational model that prioritizes learning dynamics shared across neural populations over those within a single population. | Applied to multi-regional recordings in motor and premotor cortex during a movement task. | More accurately identified known biological pathways (e.g., PMd to M1) and required lower dimensionality than non-prioritized models [4]. | Isolates cross-region interactions from within-region dynamics; supports both causal and non-causal inference. |

| Spike-Sorting-Free Population Analysis [5] | Uses multiunit threshold crossings instead of sorted single-neuron spikes to estimate population dynamics. | Data from Neuropixels probes in primate motor cortex was re-analyzed with and without spike sorting. | Neural dynamics and scientific conclusions were nearly identical using the simpler multiunit activity [5]. | Dramatically reduces data processing burden; enables new analyses of existing large-scale datasets. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: BCI Validation of Dynamical Constraints

This paradigm provides a direct test of whether observed neural trajectories are a fundamental feature of the network [1].

- Neural Recording & Decoding: Implant a multi-electrode array in the motor cortex. Record population activity and reduce it to a lower-dimensional latent state in real-time using a causal dimensionality reduction method (e.g., Gaussian process factor analysis) [1].

- Mapping to Feedback: Create two different BCI mappings that transform the latent state into a 2D cursor position:

- A Movement-Intention (MoveInt) Mapping that produces intuitive cursor control.

- A Separation-Maximizing (SepMax) Mapping designed to reveal the inherent temporal structure (e.g., curvature) of neural trajectories [1].

- Behavioral Task: Animals perform a two-target center-out task, moving the cursor between two diametrically opposed targets.

- Experimental Challenge:

- Baseline: Animals perform the task with the MoveInt mapping.

- Visual Feedback Manipulation: Switch the visual feedback to the SepMax mapping to see if the inherent neural trajectories persist or if the animal can straighten them [1].

- Direct Volitional Challenge: Provide incentives and feedback that require the animal to traverse a natural neural trajectory in a time-reversed order [2] [1].

- Outcome Measurement: The primary metric is the animal's ability or inability to successfully produce the altered (e.g., time-reversed) neural trajectories and complete the task.

Diagram 1: BCI Constraint Test Workflow

Protocol: Cross-Population Dynamics Modeling with CroP-LDM

This computational protocol identifies how different brain regions interact [4].

- Data Acquisition: Simultaneously record neural activity from two separate neural populations (e.g., in two different brain regions like PMd and M1) during a behavioral task.

- Model Definition: Designate one population as the 'source' and the other as the 'target'. The goal is to predict the target's activity from the source's activity.

- Prioritized Learning: Fit the CroP-LDM model using a learning objective that prioritizes the accuracy of cross-population prediction over the reconstruction of either population's own activity. This ensures the extracted latent states capture shared dynamics rather than within-population dynamics [4].

- State Inference: Extract the latent states representing cross-population dynamics. This can be done:

- Causally (Filtering): Using only past neural data, preserving temporal interpretability.

- Non-Causally (Smoothing): Using all data, potentially achieving higher accuracy [4].

- Pathway Quantification: Use a metric like partial R² to quantify the unique, non-redundant information that the source population provides about the target population, thereby identifying the dominant direction of interaction [4].

Diagram 2: Cross-Population Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for Neural Dynamics Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Electrode Arrays | High-temporal-resolution recording from dozens to hundreds of neurons simultaneously. | Chronic implants in non-human primate motor cortex for BCI experiments [1] [4]. |

| Neuropixels Probes | Dense, large-scale neural recording from thousands of sites across brain regions. | Validating spike-sorting-free analyses and large-scale population studies [5]. |

| GCaMP Calcium Indicators | Fluorescent imaging of neural activity via calcium dynamics; allows cell-type specificity and large population tracking. | Studying neural population dynamics in behaving mice [6]. |

| Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) Software | Provides real-time decoding of neural activity into a control signal and visual feedback for the subject. | Causal experiments challenging subjects to alter their neural activity patterns [2] [1]. |

| Dimensionality Reduction Algorithms (GPFA) | Extracts low-dimensional neural trajectories from high-dimensional population activity data. | Visualizing the temporal structure of population activity in a lower-dimensional space [1]. |

| Linear Dynamical Models (LDM) | Generative models that describe the evolution of neural population activity over time. | Serving as the base for advanced models like CroP-LDM to interpret cross-region interactions [4]. |

Empirical evidence, particularly from BCI studies, strongly supports a core computational principle: neural population dynamics are not an epiphenomenon but are central to the brain's algorithm for computation. The failure of subjects to violate these trajectories, even with strong incentives, indicates they are rigidly constrained by the underlying network connectivity [2] [1]. This convergence of causal experimentation and advanced computational modeling marks a significant step in validating long-theorized network models and provides a foundation for future clinical applications, such as developing optimized learning paradigms for stroke recovery that work with, rather than against, the brain's inherent dynamical constraints [2].

Empirical Evidence for Constrained Neural Trajectories from BCI Studies

The brain's operations are increasingly understood through the lens of neural population dynamics—the time-evolving patterns of activity across groups of neurons that underlie functions ranging from motor control to decision-making. A fundamental hypothesis in computational neuroscience proposes that these activity patterns, or neural trajectories, are constrained to follow specific paths through high-dimensional state space, much like a train following railroad tracks. This constraint is theorized to arise from the underlying network architecture of neural connections, which shapes how activity flows through the system. While theoretical models have long incorporated this principle, only recently have brain-computer interface (BCI) technologies provided the precise experimental control necessary to empirically test whether neural trajectories are indeed fixed, or whether they can be volitionally altered.

Brain-computer interfaces have emerged as a transformative tool for studying neural dynamics because they establish a direct, defined relationship between neural activity and an output behavior (e.g., cursor movement). This allows experimenters to causally test theoretical principles by challenging subjects to generate specific, often unnatural, neural activity patterns. Recent BCI studies have provided critical evidence addressing a central question: To what extent are the temporal sequences of neural population activity modifiable by learning or volition? The answer has profound implications for understanding the fundamental mechanisms of computation in the brain, as well as for developing therapies for neurological injury and disease. This guide synthesizes empirical evidence from key BCI studies that have directly tested the constraints on neural trajectories, comparing their methodologies, findings, and implications for the field of neural population dynamics.

Empirical Evidence from Key BCI Studies

The Causal Test: Challenging Neural Trajectories to Move Backwards

A landmark 2025 study by Degenhart, Oby, Batista, Yu, and colleagues provided the most direct causal test of the neural constraint hypothesis to date. Published in Nature Neuroscience, this work leveraged a BCI paradigm to challenge the fundamental assumption that neural trajectories are obligatory [2] [1] [7].

- Experimental Protocol: Researchers recorded from approximately 90 neural units in the primary motor cortex of Rhesus monkeys. They first identified the natural, stereotyped sequences of neural population activity that occurred when the monkeys moved a BCI cursor between two targets. They then designed a critical experimental challenge: they asked the monkeys to traverse these natural neural activity sequences in a time-reversed manner—essentially, to go backwards along a one-way neural path [2] [1].

- Key Findings: Despite providing clear visual feedback and strong liquid reward incentives, the monkeys were strikingly unable to violate the natural time courses of their neural activity. Even with extended practice over one to two hours, subjects could not produce the time-reversed neural trajectories. The neural activity consistently adhered to its natural, forward-going sequences, suggesting these paths are obligatory on short timescales and likely reflect hard constraints imposed by the underlying neural circuitry [2] [7].

- Interpretation: The study concluded that the neural trajectories observed in the motor cortex are not merely preferences but are robustly constrained, supporting the view that the brain's network architecture inherently shapes the flow of neural activity. As co-author Byron Yu stated, this finding "validates principles that researchers have brought out in neural network models for decades" [2].

The Intrinsic Manifold: A Framework for Understanding Constraints

Earlier foundational work from the same research groups established the concept of an "intrinsic manifold" (IM), a low-dimensional space that captures the dominant patterns of neural co-variation within a larger high-dimensional neural state space. This framework formalizes the structural constraints on neural activity [8].

- Experimental Protocol: In a 2014 study, monkeys controlled a BCI cursor using a population of 85-91 motor cortex neurons. The researchers characterized the IM from initial neural recordings. They then altered the BCI mapping between neural activity and cursor velocity in two distinct ways: through a "within-manifold perturbation" (WMP), where the new mapping was consistent with the existing IM, and an "outside-manifold perturbation" (OMP), where the new mapping required neural activity patterns that deviated from the IM [8].

- Key Findings: The results demonstrated a stark learning asymmetry. Monkeys could readily learn WMPs within a single session, as this only required reassociating existing neural patterns with new cursor movements. In contrast, they showed minimal learning of OMPs over the same timeframe. This indicated that generating new neural activity patterns that lay outside the intrinsic manifold was highly difficult on short timescales [8].

- Interpretation: The intrinsic manifold acts as a network-level constraint on learnable behaviors. The ease or difficulty of learning a new skill is profoundly shaped by whether that skill's required neural activity patterns are consistent with the brain's existing neural architecture [8].

The Timescale of Learning: Emergence of New Patterns with Long-Term Practice

The constraints revealed in the short-term studies are not necessarily absolute. A 2019 study investigated whether the brain can overcome these initial limitations and generate全新的neural activity patterns through long-term learning [9].

- Experimental Protocol: Monkeys were again tasked with learning outside-manifold perturbations (OMPs) in a BCI cursor task. However, in this experiment, they were given extended practice over multiple days (ranging from 6 to 16 days) using an incremental training paradigm [9].

- Key Findings: With multi-day practice, the monkeys successfully learned the OMP mappings, achieving performance levels comparable to those seen with within-manifold learning. Crucially, the researchers developed a "speed limit" analysis to detect new neural patterns. They found that the monkeys' learned success was directly correlated with the generation of novel neural activity patterns that lay outside the original intuitive repertoire. The percentage of these new patterns significantly increased over the course of learning [9].

- Interpretation: This study demonstrated that the neural constraints observed in short-term experiments are malleable over longer timescales. The brain can, in fact, generate new neural activity patterns to support learning, but this process is slow and requires sustained practice. This suggests that learning complex new skills, like playing a musical instrument, may indeed involve the gradual formation of new neural dynamics [9].

Comparative Analysis of Key Studies

The table below synthesizes the experimental approaches and central findings of these pivotal studies, highlighting the evolving understanding of neural constraints.

Table 1: Comparison of Key BCI Studies on Neural Trajectory Constraints

| Study (Year) | Central Research Question | Experimental Paradigm | Key Finding | Implication for Neural Constraints |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degenhart et al. (2025) [2] [1] | Can neural trajectories be volitionally reversed? | Challenged monkeys to time-reverse natural neural sequences using BCI. | Inability to generate time-reversed trajectories over hours. | Constraints are obligatory on short timescales; trajectories are "one-way paths." |

| Sadtler et al. (2014) [8] | Does neural network structure constrain learning? | Compared learning of BCI mappings inside vs. outside the intrinsic manifold. | Ready learning of within-manifold vs. poor learning of outside-manifold perturbations. | Constraints define a low-dimensional "search space" for rapid learning. |

| Oby et al. (2019) [9] | Can new neural activity patterns emerge with learning? | Assessed multi-day learning of outside-manifold perturbations. | Successful learning accompanied by emergence of novel neural patterns. | Constraints are plastic over long timescales with sustained practice. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The empirical advances in understanding neural constraints are built upon a foundation of sophisticated BCI methodologies. This section details the core protocols and workflows common to these studies.

Core BCI Workflow for Probing Neural Dynamics

The following diagram illustrates the standardized experimental pipeline used to acquire neural data, define dynamics, and test their constraints.

Specific Experimental Challenges

Within the core workflow, different types of experimental perturbations are used to test specific hypotheses about neural constraints.

- Time-Reversal Challenge: After identifying a natural neural trajectory for a specific movement, the BCI mapping or task goal is manipulated to require the subject to produce the sequence of neural population activity patterns in the reverse temporal order [2] [1].

- Projection Manipulation: Researchers switch the 2D visual feedback provided to the subject from a "movement-intention" projection, where neural trajectories for different directions may overlap, to a "separation-maximizing" projection, where the distinct, direction-dependent neural paths become visually apparent. This tests if the subject can alter these deeply embedded dynamics when they are made explicit [1].

- Manifold Perturbation: As described in Section 2.2, this involves mathematically rotating the mapping from the high-dimensional neural space to the low-dimensional control space, creating a perturbation that is either consistent with (WMP) or deliberately deviates from (OMP) the intrinsic manifold [8] [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table catalogues the critical hardware, software, and analytical tools that form the foundation of this research domain.

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for BCI Studies of Neural Dynamics

| Tool Category | Specific Examples & Functions | Key Role in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Acquisition | - Multi-Electrode Arrays (e.g., Utah Array from Blackrock Neurotech): Chronically implanted to record action potentials and local field potentials from dozens to hundreds of neurons simultaneously [10].- Electrocorticography (ECoG) Grids: Placed on the cortical surface for high-resolution signal recording [11]. | Provides the raw, high-dimensional neural population data that is the basis for all subsequent analysis. |

| Computational Modeling | - Dimensionality Reduction (e.g., Gaussian Process Factor Analysis - GPFA): Extracts smooth, low-dimensional "latent states" from noisy, high-dimensional spike trains [1].- Generative Models (e.g., Energy-based Autoregressive Generation - EAG): Models and generates realistic neural population dynamics for hypothesis testing and data augmentation [12]. | Enables the visualization and quantification of neural trajectories and manifolds. Critical for building testable models. |

| BCI Control Software | - Real-Time Decoding Algorithms: Translate neural latent states into commands for external devices (e.g., cursor velocity) with minimal latency [1] [8].- Closed-Loop Feedback Systems: Provide the subject with real-time visual information of their neural activity or its consequences [7] [9]. | Creates the causal link between neural activity and behavior, allowing for precise experimental perturbation. |

| Theoretical Framework | - Dynamical Systems Theory: Provides a mathematical language for describing how neural state variables evolve over time [1].- Network Models: Offers hypotheses about how neural connectivity gives rise to observed population dynamics and constraints [2]. | Guides experimental design and interpretation of results, connecting data to fundamental principles of computation. |

The collective evidence from BCI studies paints a nuanced picture of neural constraints. In the short term, neural trajectories are indeed highly constrained, behaving as obligatory one-way paths [2] [1] [7]. These constraints are formalized by the intrinsic manifold, which powerfully shapes initial learning capacity [8]. However, the brain exhibits remarkable long-term plasticity, capable of generating new neural activity patterns to support skill acquisition over days of practice [9]. This reconciliation of rigidity and flexibility is a major achievement of the field.

The implications are vast. Understanding these principles is guiding the development of optimized neurorehabilitation strategies for stroke or spinal cord injury, where therapies could be designed to work with, rather than against, the brain's inherent dynamics [2] [13]. Furthermore, this research provides critical empirical validation for the neural network models that underpin modern artificial intelligence, confirming that biological computation operates through structured dynamics [2] [12]. Future research will continue to bridge the gap between these population-level dynamics and their underlying circuit-level mechanisms, further unlocking the brain's computational secrets for both therapeutic and engineering applications.

Hippocampal Theta Dynamics in Real-World and Imagined Navigation

Hippocampal theta oscillations (∼3-12 Hz) represent a fundamental rhythm in the brain, serving as a core timing mechanism for coordinating neural activity during spatial navigation and memory processes. While decades of rodent research have firmly established theta's role in organizing place cell sequences during physical navigation, its characteristics and functions in humans—particularly during internally generated experiences like imagination—have remained less clear. Recent advances in intracranial electroencephalography (iEEG) and motion capture technologies have enabled unprecedented investigation into how these neural dynamics support both real-world and imagined experiences. This comparison guide examines the neurophysiological properties, experimental methodologies, and functional significance of hippocampal theta dynamics across behavioral states, providing researchers with a framework for evaluating these mechanisms in health and disease. Evidence now indicates that human hippocampal theta operates in intermittent bouts rather than the continuous oscillations observed in rodents, yet maintains its essential role in segmenting experience into discrete computational units [14]. Surprisingly, recent findings demonstrate that memory-related processing may be a more potent driver of human hippocampal theta than navigation itself, suggesting a shift in functional emphasis across species [15].

Comparative Analysis of Theta Dynamics Across Navigation States

Experimental Paradigms and Neural Recording Approaches

The investigation of hippocampal theta dynamics employs specialized experimental protocols and recording methodologies tailored to capture neural activity during both physical and mental navigation:

Real-World Navigation Tasks: Participants physically navigate predefined routes while neural activity is recorded via intracranial electrodes. Motion capture systems synchronize precise positional data with neural recordings, enabling correlation of theta dynamics with specific locations and behaviors [14] [16].

Imagined Navigation Tasks: Participants mentally simulate previously learned routes while walking on a treadmill at a steady speed, eliminating confounding effects of physical navigation while maintaining locomotor context [14] [15].

Control Conditions: Treadmill walking without explicit imagination instructions establishes baseline activity, distinguishing imagination-specific processes from general locomotor effects [14].

Neural Recording Techniques: Intracranial EEG (iEEG) from chronically implanted electrodes in the medial temporal lobe provides direct hippocampal recordings with high temporal resolution, particularly valuable in patients with implanted responsive neurostimulation devices for epilepsy treatment [14] [17].

Quantitative Comparison of Theta Properties

Table 1: Theta Oscillation Characteristics During Navigation States

| Parameter | Real-World Navigation | Imagined Navigation | Control Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theta Prevalence | Intermittent bouts (21.2±6.6% prevalence) [14] | Similar bout-like pattern [14] | Reduced temporal structure [14] |

| Bout Duration | 0.524±0.077 seconds [14] | Comparable duration | Not reported |

| Temporal Consistency | Highest (rd=0.15) [14] | Significant (rd=0.15) [14] | Lower consistency [14] |

| Spatial Encoding | Encodes position, segments routes [14] | Reconstructs imagined position [14] | Not present |

| Peak Timing | -0.94s before turns [14] | Aligned with imagined turns [14] | Not applicable |

| Functional Driver | Combination of navigation and memory [14] | Primarily memory processes [15] | Minimal cognitive load |

Table 2: Spectral and Functional Properties of Hippocampal Theta

| Characteristic | Human Theta Properties | Rodent Theta Properties | Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency Range | 3-12 Hz [14] | 4-12 Hz [14] | Potential species differences in timing |

| Continuity | Intermittent bouts [14] [15] | Continuous oscillations | Different computational mechanisms |

| Memory Link | Strong driver [15] | Present but secondary to movement | Humans may emphasize memory functions |

| Spatial Tuning | Position-dependent [14] | Position-dependent [14] | Conservation of spatial coding |

| Hemispheric Differences | Lateralized functional contributions [18] | Less investigated | Specialized memory processes per hemisphere |

Theta Dynamics in Spatial Segmentation and Memory

Hippocampal theta oscillations exhibit precise temporal organization during navigation tasks, serving to segment experience into computationally manageable units:

Spatial Segmentation: Theta dynamics partition navigational routes into linear segments, with increased theta power preceding turns by approximately 0.94 seconds, effectively marking transitions between route segments [14]. This pre-turn theta enhancement occurs before observable behavioral changes like reduced walking speed or body rotation, suggesting its role in cognitive planning rather than merely reflecting motor execution.

Temporal Consistency: Theta bouts demonstrate significant alignment across multiple trials of the same route, with temporal consistency measures (rd=0.15) significantly exceeding control conditions during both real and imagined navigation [14]. This consistency enables reliable decoding of spatial information from theta patterns alone.

Spectral Specificity: While theta frequencies (3-12 Hz) show the most prominent task-modulation, complementary oscillations in delta (1-3 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) ranges also exhibit route-segment dependencies, suggesting a multi-frequency organization of navigational processing [14].

Methodological Framework for Theta Research

Experimental Protocols and Technical Specifications

Table 3: Key Methodological Approaches in Theta Dynamics Research

| Methodology | Technical Specifications | Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intracranial EEG (iEEG) | Chronically implanted depth electrodes; Medial Temporal Lobe targeting [14] [17] | Direct hippocampal recording | Surgical implantation required; limited to clinical populations |

| Motion Capture | Multi-camera systems with reflective markers [14] | Precise tracking of position and movement | Synchronization with neural data critical |

| Task Design | Defined routes with turns; hidden visual cues [14] | Examines spatial segmentation | Requires learning phase to establish route knowledge |

| Imagination Paradigm | Treadmill walking with mental simulation instructions [14] [15] | Isolates internal cognitive processes | Subjective experience; verification challenging |

| Theoretical Modeling | Statistical position reconstruction models [14] | Tests functional significance | Model complexity must match data limitations |

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Tools

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Hippocampal Theta Investigations

| Research Tool | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Responsive Neurostimulation System | Chronic intracranial recording and stimulation [14] | Long-term monitoring in epilepsy patients |

| Motion Capture Systems | Precise tracking of position and body movements [14] | Correlating theta dynamics with navigational behavior |

| Spatial Navigation Tasks | Structured routes with decision points [14] | Examining theta segmentation of spatial experience |

| Computational Modeling | Position decoding from neural data [14] [12] | Reconstructing real and imagined navigation paths |

| Mnemonic Similarity Task | Assessing pattern separation/completion [18] [17] | Linking theta to memory discrimination processes |

Neural Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

The coordination of hippocampal theta oscillations involves complex interactions between oscillatory networks and computational processes. The following diagram illustrates the key mechanisms and their relationships in organizing neural dynamics during navigation and memory processes:

Theta-Gamma Coupling in Sequence Development

The development of spatially informative theta sequences relies on precise coordination with finer-timescale gamma oscillations:

Fast Gamma Modulation: A subset of hippocampal place cells (∼23%) shows strong phase-locking to fast gamma rhythms (65-100 Hz), with firing concentrated around the peak of fast gamma cycles [19]. These FG-cells fire across all positions within their place fields and display theta phase precession, providing a foundation for sequence formation.

Slow Gamma Coordination: During slow gamma episodes (25-45 Hz), place cells exhibit dominant theta phase-locking and attenuated theta phase precession, creating mini-sequences within theta cycles that enable highly compressed spatial representations [19]. The slow gamma phase precession pattern facilitates the integration of compressed spatial information.

Sequence Development: Theta sequences develop through experience-dependent processes, with FG-cells playing a crucial role in establishing sweep-ahead structures that represent potential future paths. This development correlates with the intensity of slow gamma phase precession, particularly during early learning phases [19].

Functional Specialization and Hemispheric Differences

The hippocampal longitudinal axis and hemispheric specialization provide additional dimensions to theta functional organization:

Anterior-Posterior Specialization: Neurophysiological evidence indicates functional differentiation along the hippocampal longitudinal axis, with anterior and posterior regions contributing differently to memory processes [17]. These differences may reflect variations in representational granularity, with posterior hippocampus supporting more precise spatial representations.

Hemispheric Complementarity: Theta oscillations in left and right hippocampus support complementary functions in mnemonic decision-making [18]. Left hippocampal theta power shows positive associations with evidence accumulation toward "new" responses, implementing a novelty-oriented decision bias, while right hippocampal theta negatively correlates with false alarms to foil items, curtailing evidence accumulation based on false familiarity [18].

Computational Implications: These specialized contributions enable the hippocampus to balance pattern separation (creating distinct representations for similar inputs) and pattern completion (retrieving complete memories from partial cues) [18] [17]. Theta oscillations may temporally coordinate these complementary processes through phase-based coding schemes.

The comparative analysis of hippocampal theta dynamics during real-world and imagined navigation reveals conserved computational principles across behavioral states while highlighting human-specific adaptations. The surprising finding that memory processing may drive human hippocampal theta more powerfully than navigation itself [15] suggests a shift in functional emphasis from rodents to humans, possibly reflecting the evolution of complex memory systems. The demonstrated ability to reconstruct both real and imagined positions from theta dynamics [14] confirms the oscillation's role as a fundamental organizing mechanism for spatial experience, whether externally perceived or internally generated.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings offer promising directions for therapeutic innovation. The detailed characterization of theta properties across states provides potential biomarkers for memory disorders, while the mechanistic insights into theta generation suggest novel targets for intervention. Future research leveraging emerging technologies like the Energy-based Autoregressive Generation framework [12] may enable more sophisticated modeling of these neural population dynamics, accelerating both basic understanding and clinical applications in conditions ranging from Alzheimer's disease to navigational impairments.

Understanding how complex cognitive functions and behavior emerge from the activity of millions of neurons remains a central challenge in systems neuroscience. Two dominant theoretical frameworks have emerged to address this challenge: the neural manifold perspective and the dynamical systems perspective. While often discussed in conjunction, these frameworks offer distinct conceptual approaches to deciphering neural population activity.

The neural manifold framework posits that the seemingly high-dimensional activity of neural populations is intrinsically constrained to a low-dimensional subspace, or "manifold," within the full neural state space [20] [21] [22]. This manifold represents the set of permissible activity patterns that can be generated by the underlying neural circuit. The geometry of this manifold is thought to reflect computational principles and behavioral constraints [22] [23].

In contrast, the dynamical systems framework models neural population activity as trajectories evolving within a state space according to definable dynamical rules [1] [24]. This perspective emphasizes how the time evolution of neural states—governed by the network's connectivity and inputs—directly implements computations. Critical dynamics, such as attractor states that guide decision-making or rotational dynamics that generate motor commands, are hallmarks of this view [1].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of these frameworks, focusing on their theoretical foundations, experimental validation, and utility for real-world engineering applications in research and therapeutic development.

Framework Comparison: Core Principles and Experimental Validation

Conceptual Foundations and Key Differentiators

The table below summarizes the core principles and technical approaches that distinguish the neural manifold and dynamical systems frameworks.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Neural Manifold and Dynamical Systems Frameworks

| Aspect | Neural Manifold Framework | Dynamical Systems Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Unit of Analysis | Low-dimensional subspaces (manifolds) embedded in high-dimensional neural state space [21] [22]. | Temporal evolution of neural population states (trajectories and flow fields) [1] [24]. |

| Central Tenet | Neural population activity is confined to a low-dimensional manifold due to constraints imposed by network connectivity and task structure [20] [22]. | Neural computations are implemented by the time evolution of population activity, shaped by the network's inherent flow field [1]. |

| View on Connectivity | Manifold structure is an emergent consequence of underlying circuit connectivity [20]. | Connectivity directly dictates the dynamical flow field that governs neural trajectories [1]. |

| Typical Analytical Methods | Dimensionality reduction (PCA, FA, UMAP, Isomap) [21] [22]. | System identification, analysis of fixed points/attractors, and vector field reconstruction [23] [24]. |

| Temporal Dynamics | Often descriptive of the structure of activity patterns; dynamics may be inferred secondarily [25]. | Intrinsically models and predicts the temporal progression of activity patterns [1] [23]. |

| Causal Testability | Requires linking manifold structure to connectivity; control of latent dynamics is an emerging approach [20] [25]. | Directly tested by challenging the system to violate its natural flow field [1] or via closed-loop control [25]. |

Quantitative Performance and Experimental Evidence

Empirical studies have provided robust, quantitative data supporting both frameworks. The following table consolidates key experimental findings that validate their core predictions.

Table 2: Experimental Evidence Supporting Each Framework

| Framework | Experimental System/Task | Key Finding | Quantitative Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Manifold | Primate motor cortex during reaching [22]. | Population activity confined to a low-dimensional subspace. | ~10 neural modes explained >90% of population variance [22]. | [22] |

| Neural Manifold | Fly head direction system [20]. | Circuit connectivity directly defines a ring manifold for encoding head direction. | Topographic mapping of neural tuning onto the physical layout of the ellipsoid body [20]. | [20] |

| Dynamical Systems | Primate motor cortex in BCI task [1]. | Neural trajectories are robust and cannot be volitionally time-reversed. | Animals failed to produce time-reversed neural activity despite strong incentive [1]. | [1] |

| Dynamical Systems | Macaque premotor cortex; delayed reach [22]. | Target-specific clusters of latent activity during delay period. | A 3D manifold sufficed to separate neural states for different reach targets [22]. | [22] |

| Unified Approach (MARBLE) | Rodent hippocampus, primate premotor cortex [23]. | Learned latent representations decode behavior and align dynamics across subjects. | State-of-the-art within- and across-animal decoding accuracy [23]. | [23] |

| Unified Approach (Control) | Spiking Neural Network (SNN) simulation [25]. | Model Predictive Control (MPC) can effectively steer latent dynamics. | MPC provided more accurate control of latent trajectories than PID controllers [25]. | [25] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Analytical Workflows

A Standard Protocol for Identifying Neural Manifolds

The standard workflow for identifying neural manifolds from population recordings involves a series of data processing and analysis steps [21].

- Neural Data Collection: Simultaneously record the activity (e.g., spike counts or calcium fluorescence) from a population of N neurons over T time points during a behavioral task. This forms a neural activity matrix, X (N neurons × T time points).

- Preprocessing: Smooth the activity of each neuron to estimate instantaneous firing rates. The data may be z-scored (mean-centered and normalized by standard deviation) per neuron across time.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply a linear or non-linear dimensionality reduction algorithm to the neural activity matrix.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): A linear method that finds the orthogonal axes (principal components, PCs) that capture the maximum variance in the data. The manifold is defined by the top-K PCs, which form a linear hyperplane in the neural state space [21] [22].

- Factor Analysis (FA): A linear method that distinguishes shared covariance (the signal) from neuron-specific variance (the noise), providing a generative model for the data [22].

- Non-linear Methods (e.g., UMAP, Isomap): Used when the manifold is suspected to be non-linearly embedded. These methods can find lower-dimensional embeddings than linear methods but may be less interpretable [21].

- Manifold Visualization and Analysis: Visualize the neural trajectories in the low-dimensional space (typically 2D or 3D for visualization). Analyze how these trajectories relate to task variables (e.g., stimuli, decisions, movements). The geometry of the manifold, such as its topology (e.g., a ring for cyclic variables) or the presence of separate clusters for discrete states, is then interpreted [20] [22].

A Protocol for Testing Dynamical Systems Constraints

A seminal experiment testing the dynamical systems framework used a brain-computer interface (BCI) to challenge the inherent neural trajectories [1]. The protocol is as follows:

- Baseline Recording and Mapping:

- Record from a population of motor cortex neurons (e.g., ~90 units) while a monkey performs a standard BCI task (e.g., moving a cursor to targets).

- Use a dimensionality reduction technique (e.g., Gaussian Process Factor Analysis, GPFA) to extract a low-dimensional latent state, z(t), from the high-dimensional neural activity at each time t [1].

- Define an intuitive "Movement-Intention" (MoveInt) BCI mapping that projects the latent state to cursor position, allowing the animal flexible control.

- Identification of Natural Neural Trajectories:

- Have the animal perform a two-target center-out task. Observe the neural trajectories in the latent space for movements from Target A to B and from B to A.

- Even if the cursor paths overlap in the MoveInt projection, identify a different 2D projection (a "Separation-Maximizing" or SepMax projection) where the A→B and B→A neural trajectories are distinct and exhibit characteristic dynamical structure (e.g., curved paths) [1].

- The Flexibility Challenge:

- Change the BCI mapping so that the cursor now reports the animal's neural activity in the SepMax projection, making the intrinsic dynamics visible.

- Task: The animal must still move the cursor between the same two targets.

- Observation: The animal continues to produce the same directionally curved neural trajectories even when this creates curved cursor paths, instead of straightening them out. This suggests an inability to violate the natural neural flow field [1].

- The Stringent Challenge (Time-Reversal):

- Directly task the animal with traversing its natural neural trajectory in a time-reversed order. For example, require it to trace a path from the endpoint of a B→A movement back to its starting point, following the reverse temporal sequence.

- Observation: Animals are unable to successfully produce the time-reversed neural trajectories, providing strong evidence that the natural time courses are fundamental constraints imposed by the underlying network [1].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core logical and experimental workflow for analyzing neural population dynamics by unifying the manifold and dynamical systems perspectives.

Neural Population Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

This section details key methodological "reagents" — computational tools and experimental paradigms — essential for research in neural manifolds and dynamical systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

| Category | Tool/Reagent | Specific Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensionality Reduction | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [21] [22] | Identifies dominant linear patterns of covariance; defines a linear manifold. | Computationally efficient but may miss non-linear structure. |

| Factor Analysis (FA) [22] | Separates shared neural variance from private noise; provides a generative model. | Better for isolating latent signals in noisy data compared to PCA. | |

| UMAP/Isomap [21] | Discovers non-linear manifolds; can achieve lower dimensions. | May sacrifice interpretability and dynamical consistency. | |

| Dynamical Modeling | Latent Factor Analysis for Dynamical Systems (LFADS) [23] | Infers single-trial latent dynamics and inputs from neural data. | A powerful tool for denoising and inferring dynamics. |

| MARBLE (MAnifold Representation Basis LEarning) [23] | Learns interpretable latent representations by decomposing dynamics into local flow fields on the manifold. | Enables comparison of dynamics across sessions and subjects without behavioral labels. | |

| Causal Testing | Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) [1] | Provides real-time feedback of neural states to volitionally manipulate neural activity. | The gold standard for testing the causal role of specific neural trajectories. |

| Model Predictive Control (MPC) [25] | An optimal control method to steer latent neural dynamics along a desired trajectory. | More accurate than reactive controllers (e.g., PID) for controlling non-linear neural systems [25]. | |

| Experimental Model | Spiking Neural Network (SNN) Simulation [25] | Provides a biologically plausible model circuit for testing control theories in silico. | Allows full access to "ground truth" connectivity and dynamics. |

Integrated Frameworks and Future Directions for Engineering Validation

The most significant recent advances have emerged from integrating the geometric perspective of neural manifolds with the causal, temporal logic of dynamical systems. This synergy is critical for real-world engineering validation, such as developing closed-loop neurotherapeutics or robust brain-machine interfaces.

Unified Frameworks for Analysis and Control

MARBLE for Cross-System Validation: The MARBLE framework exemplifies this integration by representing neural dynamics as local flow fields on a manifold [23]. Its ability to create a common latent space allows for the direct comparison of neural computations not just across trials within an animal, but across different animals and even artificial neural networks. This provides a powerful, generalizable metric for assessing the functional similarity of dynamics, which is essential for validating disease models or therapeutic effects.

Control on the Manifold: The demonstration that Model Predictive Control (MPC) can effectively steer latent dynamics in a spiking neural network simulation provides a blueprint for causal validation [25]. This approach allows researchers to test hypotheses by asking: "If the dynamics are forced to follow a specific trajectory on the manifold, does the expected behavior or computation result?" This moves beyond correlation to direct causation. MPC's superior performance over simpler controllers like PID highlights the need for model-based, anticipatory control to handle the non-linear and noisy nature of neural systems [25].

Application to Precision Psychiatry and Medicine

The integrated framework is being applied to develop objective biomarkers for neuropsychiatric disorders. The core idea is to treat the brain's neuroelectric field, measurable via EEG, as a dynamical system and to extract dynamical features that can signal deviations from a healthy trajectory [24]. These features, combined with clinical data, can be used to build predictive models for personalized risk assessment and treatment monitoring, shifting the paradigm from reactive disease care to proactive brain health management [24].

The neural manifold and dynamical systems frameworks are not competing but deeply complementary. The manifold perspective provides the geometric stage—the low-dimensional subspace of possible neural states—while the dynamical systems perspective describes the play—the lawful evolution of trajectories across that stage that implements computation. For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice of framework depends on the specific goal.

- Use the neural manifold framework to reduce data complexity, reveal the fundamental geometry of neural representations, and relate population activity structure to underlying circuit constraints.

- Use the dynamical systems framework to model and predict the temporal evolution of neural computations, identify fundamental constraints on neural activity, and formulate testable causal hypotheses about network function.

- Prioritize integrated approaches like MARBLE or manifold-based control for cross-system validation, developing robust biomarkers, and engineering closed-loop systems that interact with neural circuitry in a biologically principled way. The future of therapeutic intervention in neurology and psychiatry lies in our ability to not just read, but also to correctly interpret and gently guide these intrinsic neural dynamics.

Advanced Methods for Learning and Modeling Neural Population Dynamics

Cross-Population Prioritized Linear Dynamical Modeling (CroP-LDM)

Understanding how different neural populations interact is fundamental to unraveling the brain's computational capabilities. A significant challenge in this endeavor is that the dynamics shared across populations can be confounded or masked by the dynamics within each population [4]. Cross-Population Prioritized Linear Dynamical Modeling (CroP-LDM) is a computational framework specifically designed to address this challenge. By prioritizing the learning of shared, cross-population dynamics, it provides a more accurate and interpretable tool for analyzing multi-region neural recordings, thereby offering robust validation for engineering applications in neuroscience [4]. This guide objectively compares the performance of CroP-LDM against other contemporary static and dynamic methods, providing the experimental data and protocols necessary for researchers to evaluate its efficacy.

Methodological Comparison: CroP-LDM vs. Alternative Approaches

Core Innovation of CroP-LDM

The primary innovation of CroP-LDM is its prioritized learning objective. Unlike methods that jointly maximize the data log-likelihood of all dynamics, CroP-LDM's objective is the accurate prediction of a target neural population's activity from a source population's activity. This explicit prioritization ensures that the extracted latent states correspond to genuine cross-population interactions and are not mixed with within-population dynamics [4]. Furthermore, CroP-LDM supports both causal (filtering) and non-causal (smoothing) inference of latent states, enhancing its flexibility for different analysis goals, such as real-time prediction or post-hoc analysis [4].

Competing Models

To evaluate CroP-LDM's performance, it is compared against several alternative classes of models [4]:

- Static Methods: These include Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) and Reduced Rank Regression (RRR), which learn shared latent variables from both regions but do not explicitly model temporal dynamics.

- Non-Prioritized Linear Dynamical Models (LDM): This approach first fits an LDM to the source population and then regresses the resulting states to the target activity, lacking an integrated, prioritized objective.

- Joint Log-Likelihood LDM: This model fits the same structure as CroP-LDM but by numerically optimizing the joint log-likelihood of both cross- and within-population dynamics, thereby failing to prioritize cross-population signals.

Performance Benchmarking: Experimental Data

Accuracy in Learning Cross-Population Dynamics

CroP-LDM was rigorously tested on multi-regional recordings from the bilateral motor and premotor cortices of non-human primates during a naturalistic movement task [4]. The model's performance was quantified by its accuracy in predicting target population activity and in capturing the true underlying interaction pathways.

Table 1: Comparative Performance in Modeling Cross-Population Dynamics

| Model Category | Specific Model | Key Characteristic | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prioritized Dynamic | CroP-LDM | Prioritizes cross-population prediction | More accurate learning of dynamics, even with low-dimensional states [4] |

| Static | CCA, RRR | Learns shared latents without dynamics | Less accurate than dynamical methods [4] |

| Non-Prioritized Dynamic | Joint Log-Likelihood LDM | Fits model without prioritization | Less accurate and efficient than CroP-LDM [4] |

| Non-Prioritized Dynamic | Non-Prioritized LDM | Two-stage fitting (source then target) | Less accurate and efficient than CroP-LDM [4] |

Dimensionality Efficiency

A key advantage of CroP-LDM's prioritized approach is its efficiency. The model can represent cross-region and within-region dynamics using lower dimensional latent states than a prior dynamic method (Gokcen et al., 2022) while maintaining high accuracy, which simplifies the model and enhances interpretability [4].

Biological Interpretability and Pathway Validation

Beyond predictive accuracy, CroP-LDM was validated by its ability to recover known biological interaction pathways [4]:

- In premotor (PMd) and motor (M1) cortex recordings, CroP-LDM quantified that PMd better explains M1 activity than vice versa, consistent with known hierarchical motor control pathways.

- In bilateral recordings during a right-hand task, the model correctly identified dominant interaction pathways within the contralateral (left) hemisphere.

Table 2: Validation of Biologically Consistent Interpretations

| Experimental Dataset | CroP-LDM Finding | Biological Consistency |

|---|---|---|

| PMd and M1 recordings | PMd → M1 pathway is stronger | Consistent with known hierarchical organization [4] |

| Bilateral motor cortex recordings | Left hemisphere interactions are dominant | Consistent with contralateral motor control [4] |

Experimental Protocols

Neural Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The experimental data used to validate CroP-LDM came from two monkeys (Monkey J and Monkey C) performing 3D reach, grasp, and return movements with their right arm [4].

- Surgical and Experimental Procedures: Approved by the New York University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and compliant with NIH guidelines.

- Recording Arrays: For Monkey J, a 137-electrode array was used to record from the left hemisphere across M1, PMd, PMv, and PFC. For Monkey C, four 32-electrode arrays were implanted [4].

- Data Processing: Standard spike sorting and binning procedures were applied to obtain neural population activity timeseries.

CroP-LDM Model Fitting and Evaluation Protocol

Workflow Diagram: CroP-LDM Experimental Validation

The core methodology for the key experiments involved [4]:

- Population Selection: To model cross-region dynamics, neural populations were selected from two distinct brain regions (e.g., PMd and M1). To model within-region dynamics, two non-overlapping populations within the same region were used.

- Model Fitting: The CroP-LDM model was fit using a subspace identification learning approach similar to preferential subspace identification to optimize its prioritized prediction objective.

- State Inference: Latent states were inferred either causally (using only past data) or non-causally (using all data), depending on the analysis goal.

- Performance Metric: The primary quantitative metric was the accuracy of predicting the target population's activity. A partial R² metric was also used to quantify the non-redundant information one population provides about another [4].

- Comparison: The same evaluation metrics were computed for the alternative static and dynamic models on the same datasets for a direct comparison.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for CroP-LDM Research

| Item Name | Function / Description | Relevance in CroP-LDM Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-electrode Array | High-density neural recording device for simultaneous multi-region data acquisition. | Enabled the collection of simultaneous spike train data from motor and premotor cortical areas, which is the essential input for the model [4]. |

| Linear Dynamical System (LDS) | A mathematical framework for modeling the temporal evolution of latent states and their relation to observations. | Forms the core dynamical structure of the CroP-LDM model, providing a simple yet interpretable foundation [4]. |

| Subspace Identification Algorithm | A numerical technique for estimating the parameters (state transition, input, output matrices) of an LDS. | Used for the efficient learning of the CroP-LDM model parameters from neural data [4]. |

| Partial R² Metric | A statistical measure that quantifies the proportion of variance uniquely explained by one variable after accounting for others. | Used to quantify the non-redundant predictive information flowing from one neural population to another, strengthening causal interpretation [4]. |

Cross-Population Prioritized Linear Dynamical Modeling (CroP-LDM) represents a significant advance in the computational toolkit for analyzing neural population interactions. The experimental data demonstrates that its prioritized learning objective provides a clear advantage over both static methods and non-prioritized dynamical models in accurately capturing cross-population dynamics. Its ability to do so with lower-dimensional states and to generate biologically interpretable results, such as quantifying dominant interaction pathways, makes it a powerful framework for the real-world engineering validation of hypotheses in systems neuroscience. For researchers and drug development professionals investigating brain-wide neural circuits, CroP-LDM offers a robust, interpretable, and efficient method for uncovering the dynamic dialogues between brain regions.

Active Learning of Dynamics with Two-Photon Holographic Optogenetics

Understanding how neural circuits perform computations requires precise identification of the underlying neural population dynamics—the rules that govern how the activity of a group of neurons evolves over time due to intrinsic circuitry and external inputs [26]. Traditional methods for modeling these dynamics involve recording neural activity during a behavioral task and then fitting a model to this passively collected data. This correlational approach suffers from two key limitations: it lacks causal interpretability, and the experimenter has limited control over how the neural activity space is sampled, often leading to inefficient data collection [27] [28].

Recent advances in two-photon holographic optogenetics have created an unprecedented opportunity to overcome these limitations. This technology allows researchers to precisely control the activity of specified ensembles of individual neurons with high temporal precision while simultaneously measuring the evoked activity across the population using two-photon calcium imaging [27] [29] [30]. This "all-optical" platform enables causal perturbation experiments. However, the vast space of possible photostimulation patterns makes exhaustive testing impractical.

Active learning addresses this challenge by algorithmically selecting the most informative photostimulation patterns to efficiently identify the neural population dynamics. This guide provides a comparative analysis of this emerging methodology, its experimental protocols, and its performance against alternative approaches for real-world neural circuit identification.

Performance Comparison: Active Learning vs. Alternative Strategies

The primary goal of active learning in this context is to achieve a more data-efficient identification of neural population dynamics or connectivity compared to passive stimulation strategies. The table below summarizes quantitative performance data from key studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Neural Circuit Mapping Strategies

| Methodology | Key Principle | Reported Efficiency Gain | Primary Application | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active Learning of Dynamics [27] [28] | Algorithmically selects optimal photostimulation patterns to inform a low-rank dynamical model. | Up to 2-fold reduction in data required for a given model accuracy [27]. | Identifying causal neural population dynamics for computation. | Requires initial model; computational complexity for pattern selection. |

| Compressive Sensing (CS) Connectivity Mapping [31] | Leverages sparse connectivity to recover synapses from multi-neuron stimulation trials using numerical de-mixing. | Up to 3-fold reduction in measurements in sparsely connected populations [31]. | High-throughput mapping of monosynaptic connectivity. | Assumes sparse connectivity; less effective for dense networks. |

| Passive Random Stimulation (Baseline) | Stimulates random groups of neurons according to a pre-defined, non-adaptive schedule. | Baseline efficiency (No gain) [27] [28]. | General purpose optogenetic perturbation. | Inefficient data collection; oversamples some dynamics, misses others. |

Analysis of Comparative Data

The data indicates that active learning for dynamics and compressive sensing for connectivity are complementary rather than directly competing strategies. Active learning excels at learning the complete functional dynamics of a network—how activity flows and evolves—making it ideal for studying neural computations [27]. In contrast, compressive sensing is highly specialized for the sparser problem of recovering physical synaptic connections [31]. Both significantly outperform passive random stimulation, underscoring the value of algorithmic experiment design.

The two-fold efficiency gain from active learning means that researchers can either achieve a more accurate model of neural dynamics with the same experimental duration or reduce the time an animal is under experiment, which is critical for animal welfare and experimental throughput [27] [28].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The implementation of active learning for neural dynamics involves a tightly integrated loop of optical perturbation, measurement, and algorithmic analysis.

Core Workflow for Active Learning of Dynamics

The following diagram illustrates the cyclic process of an all-optical active learning experiment.

Protocol Steps

- Initial Data Collection & Model Initialization: The process typically begins with a small set of passive photostimulation trials, often involving random groups of 10-20 neurons. Neural population activity is recorded in response to these stimuli using two-photon calcium imaging at high frame rates (e.g., 20 Hz). This initial dataset is used to fit a preliminary model of the neural dynamics [27] [28].

- Dynamical Model Fitting: A low-rank linear autoregressive (AR) model is a common and effective choice for capturing neural population dynamics [27]. This model describes how the neural state vector

xat timet+1depends on its previous states and the applied photostimulusu:x_{t+1} = Σ_{s=0}^{k-1} (A_s x_{t-s} + B_s u_{t-s}) + vThe matricesA_s(governing internal dynamics) andB_s(governing stimulation effects) are constrained to be "diagonal plus low-rank," efficiently capturing the high-dimensional but low-dimensional structure of neural population activity [27]. - Active Stimulation Selection: The core of the active learning algorithm uses the current best model to predict which photostimulation pattern, from a set of feasible patterns, would maximize the information gain about the model parameters (e.g., the

A_sandB_smatrices). This is often framed as optimizing an acquisition function like the reduction in uncertainty of the low-rank components of the matrices [27]. - All-Optical Perturbation & Measurement: The selected pattern of neurons is photostimulated. For reliable activation, high-speed lasers (e.g., ~1030 nm, 500 kHz) are shaped by a Spatial Light Modulator (SLM) to generate multiple holographic spots, each targeting a single neuron soma with high temporal precision (e.g., 10 ms pulse) [31] [30]. Simultaneously, the activity of hundreds to thousands of neurons in the population is recorded via two-photon imaging of a calcium indicator like GCaMP [30].

- Model Update and Iteration: The newly recorded neural response is added to the training dataset, and the dynamical model is refit. The cycle (steps 3-5) repeats until the model achieves a desired level of predictive accuracy on held-out data [27] [28].

Conceptual Foundation of the Low-Rank Model

A key insight enabling efficient active learning is that neural population activity often resides on a low-dimensional manifold. The active learning strategy explicitly targets this low-rank structure for rapid identification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful implementation of this technology requires a suite of specialized biological and optical tools. The table below details key components.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for All-Ooptical Active Learning

| Item Name | Function / Role | Key Characteristics & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Fast Soma-Targeted Opsin | Enables precise, reliable depolarization of specific neuron somas via holographic light patterns. | ST-ChroME [31]: Provides high photocurrent, fast kinetics, and soma-restricted expression for minimal axonal stimulation. ChroME2f/2s [29]: Potent variants with fast/slow kinetics. |

| Genetically Encoded Calcium Indicator (GECI) | Reports neural activity as changes in fluorescence, allowing simultaneous measurement of population responses. | GCaMP [30]: The most widely used GECI; excited at ~920 nm. jGCaMP8 [30]: Offers improved sensitivity and kinetics for better spike detection. |

| High-Power Pulsed Lasers | Provides the light for both two-photon imaging and two-photon optogenetic stimulation. | Imaging Laser: Ti:Sapphire oscillator (~920 nm, 80 MHz) [30]. Stimulation Laser: Ytterbium-doped amplifier (1030-1070 nm, 0.5-10 MHz, >50 μJ pulse energy) [30]. |

| Spatial Light Modulator (SLM) | A core component for holography; shapes the stimulation laser wavefront to generate multiple simultaneous excitation spots in 3D. | Liquid crystal SLM with high refresh rate (300-600 Hz) for dynamic pattern generation [29] [30]. |

| Calcium Imaging Analysis Software | Performs real-time processing of imaging data to extract neuronal fluorescence traces and, in closed-loop systems, guide stimulation. | Suite-2P [32] or other custom packages for rapid online cell detection and activity readout [32]. |

Active learning of dynamics using two-photon holographic optogenetics represents a paradigm shift in neural system identification. By moving beyond passive observation and random perturbation, it leverages algorithmic experiment design to efficiently uncover the causal principles of neural computation. While compressive sensing offers superior performance for the specific problem of mapping sparse synaptic connectivity, active learning is a more general-purpose framework for identifying the complete functional dynamics of a network. The integration of advanced opsins, high-speed holography, and intelligent algorithms is creating a powerful toolkit for researchers and drug development professionals to validate theories of brain function with unprecedented speed and precision, bringing the field closer to a true engineering-level understanding of neural circuits.

Geometric Deep Learning for Interpretable Representations (MARBLE)

The dynamics of neural populations are fundamental to brain computation, often evolving on low-dimensional manifolds—smooth subspaces within the high-dimensional space of neural activity [23] [26]. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for deciphering how the brain processes information and generates behavior. The MAnifold Representation Basis LEarning (MARBLE) framework is a geometric deep learning method designed to infer interpretable and consistent latent representations from these complex neural population dynamics [23] [33]. By decomposing on-manifold dynamics into local flow fields and mapping them into a common latent space, MARBLE provides a powerful tool for comparing cognitive computations across different sessions, individuals, and even species [23]. This approach is particularly valuable for real-world engineering validation research in neuroscience and neuroengineering, where interpreting the underlying computational principles of neural systems is paramount.

MARBLE operates on the principle that neural computations can be understood through the lens of dynamical systems theory. In this framework, the evolution of neural population activity over time is described by dynamical flows on a manifold, much like how a pendulum's motion can be described by its position and velocity trajectories in a state space [26]. This perspective enables researchers to move beyond analyzing individual neurons to understanding the collective computation emerging from population-level interactions. MARBLE's unsupervised approach leverages the manifold structure as an inductive bias, allowing it to discover emergent low-dimensional representations that parametrize high-dimensional neural dynamics during various cognitive processes such as gain modulation, decision-making, and changes in internal state [23] [33].

How MARBLE Works: Core Methodological Framework

Theoretical Foundations

MARBLE builds upon concepts from differential geometry and the statistical theory of collective systems to characterize neural computations [23]. The method takes as input neural firing rates and user-defined labels of experimental conditions under which trials are dynamically consistent. Rather than treating these labels as class assignments, MARBLE uses them to infer similarities between local flow fields across multiple conditions, allowing a global latent space structure to emerge organically [23]. This approach differs significantly from supervised methods that require behavioral data to align representations, which can introduce unintended correspondence between experimental conditions.

The framework assumes that neural population recordings under fixed conditions are dynamically consistent—governed by the same potentially time-varying inputs. This allows describing the dynamics as a vector field Fc = (f1(c), ..., fn(c)) anchored to a point cloud Xc = (x1(c), ..., xn(c)), where n represents the number of sampled neural states [23]. MARBLE approximates the unknown neural manifold by constructing a proximity graph from the neural state samples, which enables defining a tangent space around each neural state and establishing a mathematical notion of smoothness (parallel transport) between nearby vectors [23].

Technical Architecture and Implementation

MARBLE's architecture employs a three-component geometric deep learning pipeline to transform neural dynamics into interpretable representations [23]:

Gradient Filter Layers: These layers provide the best p-th order approximation of the local flow field around each neural state, effectively capturing the local dynamical context [23].

Inner Product Features: This component uses learnable linear transformations to make latent vectors invariant to different embeddings of neural states that manifest as local rotations in flow fields [23].

Multilayer Perceptron: The final component outputs the latent representation vector for each neural state, which collectively represents the flow field under each condition as an empirical distribution [23].

The network is trained using an unsupervised contrastive learning objective that leverages the continuity of local flow fields over the manifold—adjacent flow fields are typically more similar than nonadjacent ones, except at fixed points [23]. This training approach allows MARBLE to learn meaningful representations without requiring labeled data or behavioral supervision.

The following diagram illustrates MARBLE's core workflow for processing neural data into interpretable dynamical representations:

Performance Comparison: MARBLE vs. Alternative Methods

Benchmarking Results Across Neural Systems

MARBLE has been extensively benchmarked against current representation learning approaches across various neural systems, including simulated nonlinear dynamical systems, recurrent neural networks, and experimental single-neuron recordings from primates and rodents [23]. The method demonstrates state-of-the-art within- and across-animal decoding accuracy with minimal user input, substantially outperforming existing frameworks in interpretability and decodability of the resulting latent representations [23] [33].

The following table summarizes MARBLE's performance advantages compared to alternative approaches:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Neural Representation Learning Methods

| Method | Within-Animal Decoding Accuracy | Across-Animal Decoding Accuracy | Interpretability | Required Supervision | Dynamical Consistency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MARBLE | State-of-the-art | State-of-the-art | High | Minimal (unsupervised) | Preserves fixed point structure |

| CEBRA | High | Moderate | Moderate | Requires behavioral data | Limited |

| LFADS | Moderate | Low | Low to Moderate | Requires alignment | Linear alignment only |

| PCA | Low | Low | Low | None | No explicit dynamics |

| t-SNE/UMAP | Low | Low | Moderate | None | Only implicit time information |

MARBLE's key advantage lies in its ability to provide a well-defined similarity metric between dynamical systems from a limited number of trials, expressed enough to detect subtle changes in high-dimensional dynamical flows that linear subspace alignment methods miss [23]. This capability enables researchers to relate dynamical changes to task variables such as gain modulation and decision thresholds with unprecedented sensitivity.

Applications in Specific Neural Systems

In primate studies involving the premotor cortex during reaching tasks, MARBLE discovered emergent low-dimensional latent representations that parametrize high-dimensional neural dynamics during decision-making [23]. These representations proved consistent across individuals, enabling robust comparison of cognitive computations. Similarly, in rodent hippocampus recordings during spatial navigation tasks, MARBLE achieved superior decoding accuracy compared to existing methods while providing more interpretable representations of the underlying neural dynamics [23].

When applied to recurrent neural networks (RNNs) trained on cognitive tasks, MARBLE successfully identified subtle changes in high-dimensional dynamical flows related to task variables like gain modulation and decision thresholds—changes that went undetected by linear subspace alignment methods [23] [33]. This demonstrates MARBLE's sensitivity to nonlinear variations in neural data that are crucial for understanding the neural basis of cognition.

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Protocol for Neural Data Analysis with MARBLE

Implementing MARBLE for neural population dynamics analysis involves a systematic protocol with specific steps for data preparation, model configuration, and validation:

Neural Data Preprocessing: Convert raw spike data into continuous-valued firing rates using appropriate smoothing techniques. The firing rates represent the latent neural states that must be inferred from observed spike counts, typically through an inhomogeneous Poisson process [26].

Condition Label Assignment: Define experimental condition labels under which trials are dynamically consistent. These labels are not used as class assignments but rather to identify conditions for local feature extraction [23].

Manifold Graph Construction: Approximate the underlying neural manifold by building a proximity graph from the neural state samples. This graph defines neighborhood relationships between states and enables tangent space construction [23].