Optimizing Neural Population Dynamics: From Foundational Concepts to Practical Validation in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the analysis and optimization of neural population dynamics for researchers and drug development professionals.

Optimizing Neural Population Dynamics: From Foundational Concepts to Practical Validation in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the analysis and optimization of neural population dynamics for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles of low-dimensional manifolds and dynamical flows that underpin neural computations. The review covers cutting-edge methodologies, including geometric deep learning and causal inference models, for extracting interpretable latent representations from high-dimensional neural data. It addresses key challenges in real-world applications, such as confounding variables and data scarcity, offering practical optimization strategies. Finally, the article establishes robust validation frameworks and comparative analyses, demonstrating how these approaches accelerate therapeutic development by improving target identification, lead compound optimization, and the prediction of treatment effects in complex biological systems.

Understanding the Core Principles of Neural Population Dynamics and Manifold Learning

Defining Neural Population Dynamics and Low-Dimensional Manifolds

Core Concepts and Definitions

Neural Population Dynamics refer to the time-varying patterns of coordinated activity across a group of neurons. These dynamics describe how the activities across a population of neurons evolve over time due to local recurrent connectivity and inputs from other neurons or brain areas [1]. Rather than focusing on individual neuron activity, this framework examines the collective behavior that emerges from neural ensembles, which is crucial for understanding how the brain generates computations for sensory processing, motor commands, and cognitive states [2].

Low-Dimensional Manifolds represent a fundamental organizing principle of brain function, where the high-dimensional activity of neural populations evolves within a much lower-dimensional subspace. Despite the brain containing billions of neurons, its activity can often be captured by a relatively small number of key dimensions or latent variables [3]. This manifold forms an abstract geometrical space that constrains neural population activity, effectively collapsing high-dimensional information into a simpler representation while preserving essential features [4]. The intrinsic dimensionality of brain dynamics corresponds to the minimum number of modes required for its description.

Methodological Comparison for Analysis and Optimization

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Neural Population Dynamics Methods

| Method | Core Approach | Key Advantages | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) [5] | Brain-inspired meta-heuristic with three strategies: attractor trending (exploitation), coupling disturbance (exploration), and information projection (transition regulation). | Balances exploration and exploitation; directly inspired by neural population dynamics in neuroscience. | State-of-the-art performance on benchmark and practical engineering problems versus nine other meta-heuristic algorithms. |

| Energy-based Autoregressive Generation (EAG) [2] | Employs an energy-based transformer learning temporal dynamics in latent space through strictly proper scoring rules. | Enables efficient generation with realistic population and single-neuron spiking statistics; substantial computational efficiency. | 96.9% speed-up over diffusion-based approaches; improved motor BCI decoding accuracy by up to 12.1%. |

| Cross-population Prioritized LDM (CroP-LDM) [6] | Prioritizes learning cross-population dynamics over within-population dynamics using a linear dynamical model. | Prevents cross-population dynamics from being confounded by within-population dynamics; supports causal filtering. | More accurate learning of cross-region dynamics; enables lower-dimensional latent states than prior dynamic methods. |

| MARBLE [7] | Unsupervised geometric deep learning that decomposes on-manifold dynamics into local flow fields. | Provides interpretable, consistent latent representations; enables robust comparison of cognitive computations across animals. | State-of-the-art within- and across-animal decoding accuracy with minimal user input. |

| Variational Autoencoder (VAE) Approaches [4] | Deep learning architecture to obtain low-dimensional representations of whole-brain activity; dynamics modeled with nonlinear oscillators. | Infers effective connectivity between low-dimensional networks; superior modeling of whole-brain dynamics. | Better model and classification performance than models using all nodes in a parcellation. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for NPDOA Validation

The experimental validation for the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) was conducted systematically using the PlatEMO v4.1 platform on a computer with an Intel Core i7-12700F CPU and 32 GB RAM [5].

The methodology consists of three core strategies inspired by brain neuroscience:

- Attractor Trending Strategy: Drives neural populations (solutions) towards optimal decisions, thereby ensuring exploitation capability.

- Coupling Disturbance Strategy: Deviates neural populations from attractors by coupling with other neural populations, thus improving exploration ability.

- Information Projection Strategy: Controls communication between neural populations, enabling a transition from exploration to exploitation.

The evaluation involved comprehensive experiments on standard benchmark problems and practical engineering optimization problems, including the compression spring design, cantilever beam design, pressure vessel design, and welded beam design problems. The results were compared against nine other meta-heuristic algorithms to verify effectiveness [5].

Protocol for Low-Dimensional Manifold Identification

The experimental objective is to identify whether neural manifolds are intrinsically nonlinear, using data from monkey, mouse, and human motor cortex, and mouse striatum [8].

The methodological workflow is as follows:

- Neural Recording: Record neural population activity during behavioral tasks (e.g., instructed delay center-out reaching task for monkeys).

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply both linear (Principal Component Analysis - PCA) and nonlinear (Isomap) dimensionality reduction methods to the neural population activity.

- Variance Explained Analysis: Compare the number of neural modes (dimensions) required by each method to explain a given amount of variance in the data.

- Reconstruction Error Quantification: Calculate how well the latent dynamics from each manifold can reconstruct the full-dimensional neural activity.

- Dimensionality Robustness Test: Assess the robustness of the estimated manifold dimensionality against changes in the subset of neurons used for estimation.

The key finding was that nonlinear manifolds explained the same amount of variance with considerably fewer neural modes and had lower reconstruction errors than linear manifolds, demonstrating their intrinsic nonlinearity [8].

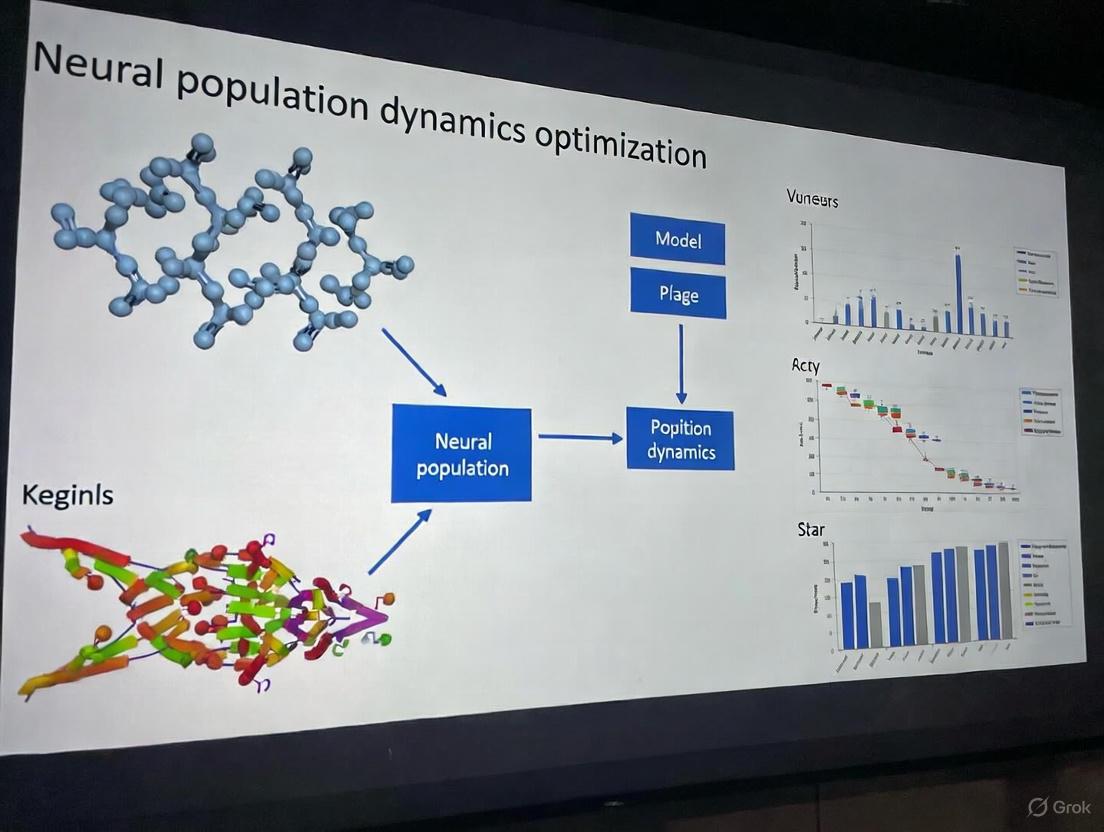

Figure 1: Workflow for neural manifold identification, comparing linear and nonlinear methods.

Key Signaling Pathways and Conceptual Workflows

The emergence of low-dimensional dynamics from high-dimensional neural activity can be explained by specific mechanisms, including time-scale separation and symmetry breaking [9].

Figure 2: Key pathways leading from high-dimensional neural activity to low-dimensional manifolds.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Neural Dynamics Studies

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Two-Photon Calcium Imaging | Measures ongoing and induced neural activity across a population (e.g., 500-700 neurons in mouse motor cortex) at high temporal resolution (e.g., 20Hz) [1]. |

| Two-Photon Holographic Optogenetics | Provides temporally precise, cellular-resolution optogenetic control to stimulate experimenter-specified groups of individual neurons, enabling causal probing of dynamics [1]. |

| Chronically-Implanted Microelectrode Arrays | Records action potentials from hundreds of putative single neurons in areas like primary motor and premotor cortex in behaving animals [8]. |

| fMRI (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) | Measures whole-brain dynamics at the macroscopic scale, allowing investigation of large-scale resting-state networks (RSNs) and their interactions during cognition [4]. |

| Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) | Deep learning architecture used to obtain compressed, low-dimensional representations (latent spaces) of high-dimensional neural data for generative modeling [4]. |

| Stuart-Landau Oscillator Models | Nonlinear oscillators used in computational models to describe the dynamics of each latent network variable, operating near critical points to simulate brain dynamics [4]. |

| Linear Dynamical Systems (LDS) | A class of interpretable models that capture the temporal evolution of neural population activity on a low-dimensional manifold [6]. |

The Role of Dynamical Flows in Neural Computation and Behavior

The brain's ability to process information and generate behavior is increasingly understood through the lens of neural population dynamics—the time-evolving patterns of activity across ensembles of neurons. The central hypothesis guiding this framework is that neural computations emerge from the collective dynamics of neuronal populations, which can be described as flow fields through a high-dimensional state space [10]. These dynamical flows are not mere epiphenomena but are believed to reflect fundamental computational mechanisms implemented by the brain's network architecture. From this perspective, cognitive processes such as decision-making, motor control, and memory recall correspond to specific trajectories through neural state space, shaped by underlying dynamical systems that constrain how population activity evolves over time [10].

Research over the past decade has demonstrated that neural dynamics during various cognitive and motor tasks exhibit characteristic structures, often unfolding on low-dimensional manifolds [11]. The emerging field of neural population dynamics optimization seeks to leverage these principles to develop computational tools that can decipher neural codes, model brain function, and interface with neural systems. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of state-of-the-art methods in this rapidly advancing field, evaluating their performance, experimental validation, and practical applications in neuroscience research and therapeutic development.

Comparative Analysis of Neural Population Dynamics Methods

Performance Benchmarking Across Methodologies

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Neural Population Dynamics Methods

| Method | Core Approach | Key Innovation | Computational Efficiency | Validation Paradigms | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPDOA [5] | Brain-inspired meta-heuristic optimization | Attractor trending, coupling disturbance, and information projection strategies | High efficiency on benchmark problems | Benchmark functions, practical engineering problems | Single-objective optimization problems |

| DynaMix [12] | ALRNN-based mixture-of-experts | Zero-shot inference preserving long-term statistics | 10k parameters; 96.9% faster than diffusion methods | Synthetic DS, real-world time series (traffic, weather) | Dynamical systems reconstruction, forecasting |

| MARBLE [11] | Geometric deep learning of manifold flows | Local flow field decomposition with unsupervised learning | State-of-art within- and across-animal decoding | Primate premotor cortex recordings, rodent hippocampus | Neural dynamics interpretation, cross-animal consistency |

| EAG [2] | Energy-based autoregressive generation | Energy-based transformer with strictly proper scoring rules | Substantial improvement over diffusion-based methods | Synthetic Lorenz systems, MCMaze, Area2bump datasets | Neural spike generation, BCI decoding improvement |

| BCI Constraint Testing [10] | Empirical challenge of neural trajectories | Direct testing of neural dynamical constraints via BCI | N/A | Monkey motor cortex during BCI tasks | Causal probing of network constraints on dynamics |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Experimental Paradigms

| Method | Short-Term Forecasting Accuracy | Long-Term Statistics Preservation | Cross-System Generalization | Single-Neuron Statistics | Behavioral Decoding Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DynaMix [12] | High (often superior to TS models) | High - faithful to attractor geometry | Strong zero-shot to out-of-domain DS | N/R | N/R |

| MARBLE [11] | N/R | High - captures invariant statistics | Consistent across networks and animals | N/R | State-of-art within- and across-animal |

| EAG [2] | N/R | High fidelity with trial-to-trial variability | Generalizes to unseen behavioral contexts | Preserves spiking statistics | Up to 12.1% BCI accuracy improvement |

| BCI Constraints [10] | N/R | Rigidly preserved even under volitional challenge | N/R | N/R | Demonstrates fundamental limits on BCI control |

Experimental Validation and Practical Problem Solving

The evaluated methods have been validated across diverse experimental paradigms, from synthetic benchmarks to real neural data. The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) demonstrates its effectiveness through balanced exploration and exploitation capabilities, solving practical optimization problems including compression spring design, cantilever beam design, pressure vessel design, and welded beam design problems [5]. These engineering applications validate NPDOA's capacity to handle nonlinear, nonconvex objective functions common in real-world optimization scenarios.

MARBLE has been extensively validated on experimental single-neuron recordings from primates during reaching tasks and rodents during spatial navigation, demonstrating substantially more interpretable and decodable latent representations than current representation learning frameworks like LFADS and CEBRA [11]. Its unsupervised approach discovers consistent low-dimensional latent representations that parametrize high-dimensional neural dynamics during gain modulation, decision-making, and changes in internal state.

The DynaMix architecture achieves accurate zero-shot reconstruction of novel dynamical systems, faithfully reproducing attractor geometry and long-term statistics without retraining [12]. Its performance surpasses existing time series foundation models like Chronos while utilizing only 0.1% of the parameters and achieving orders of magnitude faster inference times.

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Core Algorithmic Frameworks and Implementation

NPDOA implements three novel search strategies inspired by brain neuroscience: (1) The attractor trending strategy drives neural populations toward optimal decisions, ensuring exploitation capability; (2) The coupling disturbance strategy deviates neural populations from attractors by coupling with other neural populations, improving exploration ability; and (3) The information projection strategy controls communication between neural populations, enabling transition from exploration to exploitation [5]. This brain-inspired approach treats each neural state as a solution, with decision variables representing neuronal firing rates.

MARBLE employs a sophisticated geometric deep learning pipeline that: (1) Represents local dynamical flow fields over underlying neural manifolds; (2) Approximates the unknown manifold using proximity graphs to define tangent spaces around each neural state; (3) Decomposes dynamics into local flow fields (LFFs) defined for each neural state; (4) Maps LFFs to latent vectors using gradient filter layers, inner product features, and multilayer perceptrons [11]. This approach provides a data-driven similarity metric between dynamical systems from limited trials.

EAG implements a two-stage paradigm: (1) Neural representation learning using autoencoder architectures to obtain latent representations from neural spiking data under a Poisson observation model; (2) Energy-based latent generation employing an energy-based autoregressive framework that predicts missing latent representations through masked autoregressive modeling [2]. This framework uses strictly proper scoring rules to enable efficient generation while maintaining high fidelity.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

The empirical testing of dynamical constraints [10] employs a rigorous BCI protocol with rhesus monkeys: (1) Record activity of ~90 neural units from motor cortex using multi-electrode arrays; (2) Transform neural activity into 10D latent states using causal Gaussian process factor analysis; (3) Implement BCI mapping that projects 10D latent states to 2D cursor position; (4) Identify natural neural trajectories during two-target BCI tasks; (5) Test flexibility of neural trajectories through progressive experimental manipulations, including providing visual feedback in different neural projections and directly challenging animals to produce time-reversed neural trajectories.

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow for testing neural dynamical constraints:

DynaMix validation employs these key protocols [12]: (1) Pre-training on a diverse corpus of 34 dynamical systems; (2) Zero-shot testing on completely novel systems outside training distribution; (3) Comparison against established time series foundation models (Chronos, Mamba4Cast) on both synthetic and real-world data; (4) Evaluation of attractor geometry reproduction and long-term statistics preservation; (5) Assessment of inference time and parameter efficiency.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Neural Dynamics Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-electrode Arrays | Hardware | Large-scale neural activity recording | Simultaneous recording of ~90 neural units in motor cortex [10] |

| Causal GPFA | Algorithm | Dimensionality reduction of neural data | Extract 10D latent states from high-dimensional neural recordings [10] |

| Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) | Platform | Provide neural activity feedback and test causal hypotheses | Challenge animals to alter natural neural trajectories [10] |

| ALRNN Architecture | Model | Base model for mixture-of-experts systems | DynaMix experts specializing in different dynamical regimes [12] |

| Energy-Based Transformers | Architecture | Learn temporal dynamics through scoring rules | EAG framework for efficient neural spike generation [2] |

| Geometric Deep Learning | Framework | Representation learning on manifold structures | MARBLE's local flow field decomposition [11] |

| Strictly Proper Scoring Rules | Mathematical Tool | Evaluate and optimize probabilistic forecasts | EAG training to preserve trial-to-trial variability [2] |

| Optimal Transport Distance | Metric | Compare distributions of latent representations | MARBLE's distance metric between dynamical systems [11] |

Signaling Pathways and Theoretical Frameworks

The research reveals that neural computation operates through structured flow fields in population state space, constrained by underlying network architecture. The BCI experiments provide compelling evidence that neural trajectories are difficult to violate, suggesting they reflect fundamental computational mechanisms rather than arbitrary activity patterns [10]. This constrained dynamics framework has profound implications for understanding neural computation and developing brain-inspired algorithms.

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between network architecture, dynamics, and computation:

The emerging principle of zero-shot inference for dynamical systems represents a paradigm shift in computational neuroscience [12]. Unlike traditional approaches that require purpose-training for each new system observed, foundation models like DynaMix can generalize to novel systems without retraining, analogous to capabilities seen in large language models.

The comparative analysis presented here reveals substantial progress in understanding and leveraging neural population dynamics for computational modeling and practical applications. Methods like NPDOA, MARBLE, DynaMix, and EAG demonstrate complementary strengths: NPDOA offers brain-inspired optimization principles; MARBLE provides unparalleled interpretability of neural dynamics; DynaMix enables zero-shot inference across systems; and EAG achieves unprecedented efficiency in neural data generation.

The empirical demonstration that neural trajectories are difficult to violate, even with direct volitional challenge through BCI paradigms [10], provides crucial validation for the fundamental hypothesis that neural dynamics reflect underlying computational mechanisms. This finding has significant implications for neural engineering applications, suggesting that BCIs and other neural interfaces should work with, rather than against, the brain's natural dynamical tendencies.

Future research directions include: (1) Developing more sophisticated multi-scale models that bridge neural dynamics with molecular and circuit-level mechanisms; (2) Creating standardized benchmarking platforms for neural population dynamics methods; (3) Exploring clinical applications in neurological and psychiatric disorders where neural dynamics may be disrupted; (4) Integrating these approaches with emerging neurotechnology for closed-loop therapeutic interventions. As the field matures, the convergence of brain-inspired algorithms and empirical neuroscience promises to unlock new frontiers in understanding cognition and developing effective interventions for brain disorders.

The analysis of neural population dynamics—the coordinated activity across ensembles of neurons—is fundamental to advancing neuroscience research and its applications in neurotechnology and drug discovery. However, extracting meaningful, reproducible insights from neural data is hampered by several persistent computational challenges. High-dimensionality arises when recording from hundreds to thousands of neurons simultaneously, creating a complex data space that is difficult to model and interpret. Representational drift refers to the phenomenon where neural responses to the same stimulus or behavior gradually change over time, even while behavioral output remains stable, potentially undermining reliable decoding models [13]. Cross-session variability compounds this problem, as neural recordings conducted on different days or under slightly different conditions exhibit significant shifts, making it difficult to integrate data or build consistent longitudinal models. For researchers and drug development professionals, overcoming these challenges is critical for developing robust brain-computer interfaces, validating therapeutic effects on neural circuitry, and building generalizable models of brain function. This guide objectively compares the performance of modern computational platforms designed to overcome these obstacles, providing a foundation for selecting appropriate tools in a research and development context.

Comparative Analysis of Computational Platforms

The table below summarizes the core methodologies, primary applications, and documented performance of several leading approaches for handling neural population dynamics.

Table 1: Comparison of Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Platforms

| Platform/Method | Core Approach | Handled Challenges | Reported Performance / Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Population Dynamics Optimization (NPDOA) [5] | Brain-inspired meta-heuristic with three strategies: attractor trending, coupling disturbance, and information projection. | High-dimensionality, Exploration-Exploitation Trade-off | Validated on benchmark and practical problems; Balances exploration and exploitation more effectively than some classical algorithms like PSO and GA. |

| MARBLE [11] | Geometric deep learning to decompose dynamics into local flow fields on manifolds. | High-dimensionality, Cross-session Variability | State-of-the-art within- and across-animal decoding accuracy; Provides a robust data-driven similarity metric for comparing dynamics across subjects. |

| Cross-Modality Contrastive Learning [14] | Weakly supervised learning to extract only stimulus-relevant components from neural activity. | Representational Drift, High-dimensionality | Achieved ~99% accuracy decoding multiple natural features; Showed a ~50% performance drop over 90-minutes due to drift, affecting fast features more. |

| Energy-based Autoregressive Generation (EAG) [2] | Energy-based transformer learning temporal dynamics in latent space via scoring rules. | High-dimensionality, Trial-to-trial Variability | State-of-the-art generation quality on Neural Latents Benchmark; 96.9% speed-up over diffusion-based methods; Improved motor BCI decoding by up to 12.1%. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Quantifying Representational Drift using fMRI

This protocol is derived from longitudinal fMRI studies investigating drift in human primary visual cortex (V1) [13].

- Objective: To measure and characterize the representational drift of neural responses to naturalistic stimuli over a timescale of many months.

- Stimuli & Task: Participants view a large database of naturalistic scenes while undergoing fMRI scanning. The experiment is repeated over multiple sessions across a year.

- Data Acquisition: fMRI BOLD activity is collected from visual cortex while subjects view the stimuli. A memory task may be incorporated to engage neural circuits.

- Encoding Model Fitting: A computational encoding model is fitted to the fMRI responses for each individual session. This model aims to predict neural activity based on the presented images.

- Cross-Session Generalization Test: The model fit on data from one session is tested on data from other sessions. A drop in the cross-validated R² (cvR²) with increasing time between sessions is a key metric for drift.

- Drift Source Analysis: To pinpoint the source of drift, the mean and variance of individual voxel responses are analyzed across sessions. Changes in the baseline response amplitude, rather than tuning width or preference, are identified as the primary contributor.

- Population Stability Analysis: Representational Dissimilarity Matrices (RDMs) are constructed for each session. The stability of the RDM across sessions indicates that while absolute responses drift, the relative similarity between stimulus representations is maintained.

Protocol 2: Cross-Modality Contrastive Learning for Feature-Specific Drift

This protocol uses a cutting-edge machine learning method to analyze how drift affects different behaviorally relevant features [14].

- Objective: To investigate how representational drift simultaneously influences the neural encoding of multiple features in a natural movie stimulus.

- Data: Publicly available Neuropixels recordings from mouse primary visual cortex (V1) in response to a natural movie, across two sessions 90 minutes apart.

- Stimulus Feature Decomposition: The natural movie is dissected into two feature streams: static scene texture and dynamic optic flow. Unsupervised clustering is applied to group frames with similar features.

- Model Training: A cross-modality contrastive learning model is trained. It learns an embedding of neural activity that retains only the components shared with the co-occurring natural movie stimulus, effectively filtering out individual behavioral variability.

- Embedding Validation: The quality of the learned embedding is tested by decoding multiple natural features (scene, motion, time). The model achieves near-optimal decoding accuracy (~99%) from single-trial data.

- Drift Quantification: Linear decoders are trained on the embedding from session 1 and then used to read out stimulus features from the embedding of session 2. The drop in decoding performance quantifies the impact of drift.

- Feature-Specific Analysis: The decay in decoding performance is compared for fast-fluctuating (optic flow) versus slow-fluctuating (scene) features. The results show the decay ratio for fast features is three times greater than for slow features.

Protocol 3: Benchmarking Manifold Learning with MARBLE

This protocol evaluates the performance of manifold learning methods for deriving consistent latent dynamics [11].

- Objective: To benchmark a method (MARBLE) that learns interpretable and consistent latent representations of neural population dynamics across conditions and subjects.

- Data Input: The method takes as input neural firing rates from multiple trials under various task conditions (e.g., reaching in primates, navigation in rodents).

- Local Flow Field Construction: For each experimental condition, the neural population dynamics are described as a vector field anchored to a cloud of neural states. A proximity graph approximates the underlying manifold.

- Local Flow Field Decomposition: The global vector field is decomposed into Local Flow Fields (LFFs) around each neural state, capturing the short-term dynamical context.

- Unsupervised Geometric Deep Learning: An unsupervised geometric deep learning architecture maps each LFF to a latent vector. The architecture includes gradient filter layers and inner product features to ensure invariance to different neural embeddings.

- Similarity and Decoding Analysis: The latent representations for different conditions or animals are compared using an optimal transport distance. The method is benchmarked against other approaches (e.g., LFADS, CEBRA) for within- and across-animal decoding accuracy.

Visualizing Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Workflow for Analyzing Representational Drift

The following diagram illustrates a generalized, high-level workflow for quantifying and analyzing representational drift in neural data, integrating concepts from the cited experimental protocols.

A Conceptual Pathway of Behavioral Modulation on Drift

This diagram outlines the proposed pathway through which an animal's internal behavioral state can contribute to observed representational drift, a key finding from the literature [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key computational tools, datasets, and methodological approaches that serve as essential "reagents" for research in this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Neural Dynamics Challenges

| Reagent / Solution | Type | Primary Function | Key Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allen Brain Observatory [15] [14] | Public Dataset | Provides large-scale, standardized neural recordings (Neuropixels) with behavioral data. | Serves as a benchmark for testing new algorithms; Used to document representational drift and its link to behavior. |

| Cross-Modality Contrastive Learning [14] | Algorithm/Method | Learns an embedding that retains only stimulus-relevant components from neural data. | Isolates behaviorally relevant neural components; Enables quantification of feature-specific drift. |

| Representational Dissimilarity Matrix (RDM) [13] | Analytical Tool | A matrix that captures the dissimilarity between population responses to different stimuli. | Tests the stability of neural representations over time, even as single-neuron responses drift. |

| Digital Twin Generators [16] | AI Model | Creates simulated patient models to predict disease progression without treatment. | Used to optimize clinical trial design (e.g., reducing control arm size), accelerating therapeutic development. |

| Geometric Deep Learning [11] | Algorithmic Framework | Learns from data structured on manifolds or graphs. | Infers the latent manifold structure of neural dynamics for consistent cross-session and cross-subject analysis. |

| Energy-Based Models (EBMs) [2] | Algorithmic Framework | Defines probability distributions through energy functions for efficient generation. | Models stochastic neural population dynamics with high fidelity and computational efficiency for BCI and simulation. |

The transition from analyzing single-neuron activity to understanding population-level neural dynamics represents a fundamental shift in modern neuroscience. While single-neuron recordings provide high-fidelity measurements of individual cell spiking, they capture only a sparse subset of neural activity within a local circuit. In contrast, population-level analysis reveals how coordinated activity across many neurons gives rise to brain functions, though this often comes with a trade-off in temporal fidelity and direct access to neural firing events. This guide objectively compares the performance, data types, and experimental paradigms of single-neuron electrophysiology and emerging population-level techniques, with a specific focus on their application in neural population dynamics optimization and practical problem validation research. The comparison is framed within the broader thesis that understanding the transformation between these data modalities is crucial for accurate interpretation of neural circuit function and for developing effective neuromodulation technologies.

Comparative Analysis of Neural Recording Methodologies

Fundamental Technical Specifications

Table 1: Technical comparison of neural recording and analysis methodologies

| Feature | Single-Neuron Electrophysiology | Calcium Imaging | Population-Level Analysis Frameworks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Type | Spike trains (action potentials) with high temporal precision | Fluorescence signals reflecting intracellular calcium dynamics | Low-dimensional latent states derived from high-dimensional population activity |

| Temporal Resolution | Millisecond precision | Limited by calcium dynamics (low-pass filtered) | Varies with technique (can incorporate both fast and slow dynamics) |

| Neuronal Sampling | Sparse, biased toward highly active neurons | Dense, from all visualized neurons in a field | Can integrate across sparse or dense recordings |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | High for detecting spikes | Lower, limited dynamic range | Enhanced through dimensionality reduction |

| Selectivity Detection | Reveals multiphasic neurons (31% in ALM) [17] | Underrepresents multiphasic neurons (3-5% in ALM) [17] | Can track how selectivity evolves across population states |

| Advantages | Direct spike reporting, high temporal fidelity | Cell-type specificity, longitudinal tracking of identical neurons | Reveals emergent population properties, robust to single-neuron variability [18] |

| Limitations | Blind sampling, spike sorting artifacts | Indirect spike reporting, nonlinear transformation | Requires specialized statistical methods, can obscure single-cell diversity |

Quantitative Performance Discrepancies

Substantial quantitative discrepancies emerge when comparing analyses performed on different neural data types. In studies of mouse anterolateral motor cortex (ALM) during a decision-making task, extracellular electrophysiology revealed that 31% of neurons were multiphasic (changing selectivity during the trial), while calcium imaging data showed only 3-5% of neurons exhibited this property [17]. This discrepancy persisted even when comparing to intracellular recordings (25.7% multiphasic), indicating it does not stem from spike sorting artifacts but rather fundamental differences in what each technique measures [17]. These differences were only partially resolved by spike inference algorithms applied to fluorescence data, highlighting the challenge of relating these data types.

Population-level analyses demonstrate that high-dimensional neural codes exhibit remarkable stability despite single-neuron variability. Research using chronic calcium imaging in mouse V1 found that multidimensional correlations between neurons restrict variability to non-coding directions, making population representations robust to what appears as noise at the single-neuron level [18]. In fact, up to 50% of single-trial, single-neuron "noise" can be predicted using these population-level correlations [18].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Simultaneous Spikes and Fluorescence Recording

This protocol establishes the empirical basis for relating spiking activity to calcium-dependent fluorescence, crucial for validating transformation models.

Experimental Workflow:

- Subject Preparation: Express calcium indicator (e.g., GCaMP6s, GCaMP6f) in cortical neurons of mice via viral gene transfer (AAV) or using transgenic lines (Thy-1).

- Apparatus Setup: Implement two-photon calcium imaging system combined with either intracellular or extracellular electrophysiology equipment.

- Simultaneous Recording: Present sensory stimuli or engage animals in behavioral tasks (e.g., tactile delayed response task) while collecting both fluorescence and spike data from the same neurons.

- Data Processing: Preprocess fluorescence signals to remove motion artifacts and extract ΔF/F. Preprocess electrophysiology data to identify spike times.

- Model Fitting: Develop a phenomenological model that transforms spike trains to synthetic imaging data using the simultaneous recordings. The model should account for nonlinearities and low-pass filtering characteristics of calcium indicators.

- Validation: Test the model's ability to recapitulate differences observed between separate electrophysiology and imaging experiments.

Key Measurements:

- Spike-triggered average fluorescence transients

- Fluorescence kinetics for different spike patterns (single spikes, bursts)

- Neuron-to-neuron variability in spike-to-fluorescence transformation

Protocol 2: Population-Level State Manipulation Using OMiSO Framework

This protocol outlines the OMiSO (Online MicroStimulation Optimization) framework for achieving targeted neural population states through state-dependent stimulation.

Experimental Workflow:

- Neural Interface Preparation: Implant multi-electrode array in target brain region (e.g., PFC area 8Ar) in non-human primates.

- Baseline Characterization: Record neural activity during relevant behaviors or at rest to establish baseline population states.

- Latent Space Identification: Apply Factor Analysis (FA) to no-stimulation trials to identify low-dimensional latent space of population activity:

x_i,j | z_i,j ~ N(Λ_i z_i,j + μ_i, Ψ_i)wherez_i,jis latent state,Λ_iis loading matrix,μ_iis mean spike counts,Ψ_iis independent variance [19]. - Latent Space Alignment: Align latent spaces across multiple sessions using orthogonal transformation matrices (solving the Procrustes problem) to merge data collected at different times [19].

- Stimulation-Response Modeling: Fit models that predict post-stimulation latent states given stimulation parameters and pre-stimulation states.

- Inverse Model Application: Invert the trained stimulation-response models to determine optimal stimulation parameters for achieving target population states.

- Adaptive Updating: Continuously update the inverse model during experiments using newly observed stimulation responses to improve optimization performance.

Key Measurements:

- Distance between achieved neural state and target state in latent space

- Accuracy of stimulation-response model predictions

- Improvement in target achievement with adaptive updating compared to static methods

Figure 1: OMiSO experimental workflow for population state optimization

Signaling Pathways and Theoretical Frameworks

From Spikes to Population Dynamics: A Conceptual Framework

The transformation from single-neuron spiking to population-level dynamics involves multiple stages of signal processing and integration. The pathway begins with action potential generation in individual neurons, which triggers intracellular calcium influx through voltage-gated calcium channels. This calcium binds to fluorescent indicators (e.g., GCaMP), producing fluorescence signals that are nonlinear, low-pass filtered representations of the original spiking activity. These transformed signals from multiple neurons are then analyzed collectively using dimensionality reduction techniques to extract latent population dynamics that underlie behavior and cognition.

Figure 2: Conceptual framework from spikes to population dynamics

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for neural population dynamics research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| GCaMP6s (AAV-delivered) | Calcium indicator for imaging | Slower kinetics, higher sensitivity; suitable for detecting burst events [17] |

| GCaMP6s (Transgenic) | Calcium indicator for imaging | Faster dynamics, lower expression levels; reduced nonlinearities [17] |

| GCaMP6f (Transgenic) | Calcium indicator for imaging | Faster but less sensitive; balances temporal fidelity and detection sensitivity [17] |

| Multi-electrode Arrays | Electrophysiological recording | Simultaneous recording from multiple neurons; compatible with microstimulation [19] |

| Factor Analysis (FA) | Dimensionality reduction method | Identifies low-dimensional latent structure from high-dimensional neural data [19] |

| Procrustes Transformation | Cross-session alignment | Aligns latent spaces across multiple experimental sessions [19] |

| Optimal Transport Metrics | Comparing noisy neural dynamics | Quantifies geometric similarity between neural trajectories accounting for noise [20] |

| CNDMS Model | Nonconvex optimization | Coevolutionary neural dynamics with multiple strategies; handles perturbations [21] |

The comparison between single-neuron recordings and population-level analyses reveals significant discrepancies in analytical outcomes, particularly in characterizing dynamic neural selectivity. These differences stem from fundamental technical limitations and the nonlinear transformations inherent in indirect recording methods like calcium imaging. Forward modeling approaches that explicitly account for these transformations provide a promising path for reconciling observations across recording modalities. Emerging frameworks like OMiSO demonstrate how population-level approaches can not only describe neural activity but also actively manipulate it toward target states, with significant implications for both basic neuroscience and therapeutic development. The integration of these complementary perspectives—single-neuron precision and population-level breadth—will continue to advance our understanding of neural population dynamics and their optimization.

Advanced Computational Methods for Modeling and Applying Neural Dynamics

The dynamics of neural populations are fundamental to brain computation, often evolving on low-dimensional manifolds within a high-dimensional state space [22]. Understanding these dynamics requires methods that can learn the underlying dynamical processes to infer interpretable and consistent latent representations. The MAnifold Representation Basis LEarning (MARBLE) framework is a representation learning method designed to address this challenge by decomposing on-manifold dynamics into local flow fields and mapping them into a common latent space using unsupervised geometric deep learning [11] [7].

MARBLE stands apart from traditional dimensionality reduction techniques like PCA, t-SNE, or UMAP by explicitly representing temporal information and dynamical flows [11]. While methods like canonical correlation analysis (CCA) can align neural trajectories across sessions, they are most meaningful when trial-averaged dynamics approximate single-trial dynamics. In contrast, MARBLE captures quantitative changes in dynamics and geometry crucial during phenomena like representational drift or gain modulation, going beyond what topological data analysis can achieve [11].

How MARBLE Works: Technical Framework and Architecture

Core Theoretical Foundations

MARBLE conceptualizes neural population activity as dynamical flow fields over underlying manifolds. The framework takes as input neural firing rates and user-defined labels of experimental conditions under which trials are dynamically consistent [11]. It represents an ensemble of trials {x(t; c)} per condition c as a vector field Fc = (f₁(c), ..., fₙ(c)) anchored to a point cloud Xc = (x₁(c), ..., xₙ(c)), where n represents the number of sampled neural states [11].

The method approximates the unknown neural manifold using a proximity graph to Xc, which enables defining a tangent space around each neural state and establishing smoothness (parallel transport) between nearby vectors. This construction allows MARBLE to define a learnable vector diffusion process that denoises the flow field while preserving its fixed point structure [11].

Architectural Components

MARBLE's architecture consists of three key components that transform local dynamical information into interpretable latent representations [11]:

Gradient Filter Layers: These layers provide the best p-th order approximation of the local flow field around each neural state, effectively capturing the local dynamical context.

Inner Product Features: This component uses learnable linear transformations to create latent vectors invariant to different embeddings of neural states that manifest as local rotations in local flow fields.

Multilayer Perceptron: The final component outputs the latent representation vector zᵢ for each neural state.

The framework operates through an unsupervised training approach, leveraging the continuity of local flow fields over the manifold. Adjacent flow fields are typically more similar than nonadjacent ones, providing a contrastive learning objective without requiring behavioral supervision [11].

Table: Core Components of the MARBLE Architecture

| Component | Function | Output |

|---|---|---|

| Gradient Filter Layers | Approximates local flow fields | p-th order local dynamical context |

| Inner Product Features | Ensures invariance to neural embeddings | Rotation-invariant feature set |

| Multilayer Perceptron | Maps features to latent space | Latent representation vector zᵢ |

MARBLE Workflow and Vector Field Processing

The following diagram illustrates MARBLE's complete processing pipeline from neural data to latent representations:

MARBLE Processing Pipeline

Performance Comparison: MARBLE vs. Alternative Methods

Experimental Benchmarking Methodology

MARBLE has been extensively benchmarked against current representation learning approaches across multiple neural datasets. The evaluation framework employed several experimental paradigms to assess within- and across-animal decoding accuracy, including:

- Simulated nonlinear dynamical systems to test fundamental representation capabilities

- Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) trained on cognitive tasks to evaluate detection of subtle changes in high-dimensional dynamical flows

- Experimental single-neuron recordings from primates during reaching tasks and rodents during spatial navigation tasks to validate real-world applicability [11]

The benchmarking compared MARBLE against several state-of-the-art methods: CEBRA (Consistent EmBeddings of high-dimensional Recordings using Auxiliary variables), LFADS (Latent Factor Analysis for Dynamical Systems), linear subspace alignment methods, and other representation learning frameworks [11].

Quantitative Performance Results

Table: Performance Comparison Across Neural Decoding Tasks

| Method | Within-Animal Decoding Accuracy | Across-Animal Decoding Accuracy | Computational Efficiency | User Input Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MARBLE | State-of-the-art [11] [7] | State-of-the-art [11] [7] | Moderate | Minimal [11] [7] |

| CEBRA | High [11] | High (requires behavioral supervision) [11] | High | Moderate (often requires behavioral labels) [11] |

| LFADS | Moderate [11] | Limited (requires alignment) [11] | Moderate | Significant [11] |

| Linear Subspace Alignment | Limited [11] | Poor for nonlinear dynamics [11] | High | Minimal |

MARBLE demonstrates particular strength in detecting subtle changes in high-dimensional dynamical flows that linear subspace alignment methods cannot detect [11]. These changes are crucial for understanding neural computations related to gain modulation and decision thresholds. Furthermore, MARBLE discovers consistent latent representations across networks and animals without auxiliary signals, providing a well-defined similarity metric for comparing neural computations [11].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for MARBLE Implementation

| Component | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Neural Firing Rate Data | Primary input for dynamical analysis | Preprocessed spike counts or calcium imaging data |

| Condition Labels | Identifies dynamically consistent trials | User-defined based on experimental design |

| Proximity Graph Algorithm | Approximates underlying neural manifold | Constructs graph representation of neural states |

| Vector Diffusion Process | Denoises flow fields while preserving fixed points | Implemented via geometric deep learning |

| Gradient Filter Layers | Captures local dynamical context | Order p determines approximation quality |

| Optimal Transport Distance | Quantifies similarity between dynamical systems | Enables comparison across conditions/animals |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Implementing MARBLE for neural population analysis involves the following key steps:

Data Preparation: Format neural data as time series of firing rates {x(t; c)} for each condition c. Conditions should represent experimental contexts where trials are dynamically consistent.

Manifold Approximation: Construct proximity graphs from neural states to approximate the underlying manifold structure. This involves calculating neighborhood relationships between neural states.

Local Flow Field Extraction: Decompose dynamics into local flow fields (LFFs) defined for each neural state as the vector field within a specified distance p over the graph. This lifts d-dimensional neural states to a O(dᵖ⁺¹)-dimensional space encoding local dynamical context.

Geometric Deep Learning Processing: Process LFFs through MARBLE's three-component architecture (gradient filter layers, inner product features, and multilayer perceptron) to generate latent representations.

Similarity Quantification: Compute distances between latent representations of different conditions using optimal transport distance, which leverages the metric structure in latent space and generally outperforms entropic measures for detecting complex interactions [11].

The following diagram illustrates MARBLE's geometric deep learning architecture in detail:

MARBLE Geometric Learning Architecture

Applications in Neural Population Dynamics and Drug Discovery

Neural Computation Analysis

MARBLE has demonstrated significant utility in analyzing neural population dynamics across various brain regions and behaviors. In the premotor cortex of macaques during a reaching task, MARBLE discovered emergent low-dimensional latent representations that parametrize high-dimensional neural dynamics during gain modulation and decision-making [11]. Similarly, in the hippocampus of rats during spatial navigation, MARBLE revealed consistent representations of changes in internal state [11].

These representations remain consistent across neural networks and animals, enabling robust comparison of cognitive computations. The consistency of MARBLE's representations facilitates the assimilation of data across experiments, providing a powerful approach for identifying universal computational principles across different neural systems [7].

Potential Applications in Structure-Based Drug Design

While MARBLE was developed specifically for neural dynamics, its foundation in geometric deep learning shares conceptual frameworks with approaches emerging in structure-based drug design. Geometric deep learning applies neural network architectures to non-Euclidean data structures like graphs and manifolds, making it particularly suitable for molecular systems where interactions occur in three-dimensional space [23].

The geometric principles underlying MARBLE could potentially inform future drug discovery approaches in several ways:

Molecular Dynamics Analysis: Similar to neural dynamics, molecular dynamics evolve on low-dimensional manifolds that could be analyzed using MARBLE's approach to vector field decomposition.

Protein-Ligand Interaction Mapping: The local flow field concept could be adapted to model dynamic interaction fields around binding sites.

Structure-Based Molecular Design: MARBLE's ability to discover consistent representations across systems could help identify invariant structural motifs relevant for drug design.

However, it's important to note that current applications of geometric deep learning in drug discovery primarily focus on 3D structure analysis using representations like 3D grids, 3D surfaces, and 3D graphs [23], rather than the dynamical systems approach pioneered by MARBLE.

MARBLE represents a significant advancement in geometric deep learning for dynamical systems, particularly in the domain of neural population analysis. By decomposing on-manifold dynamics into local flow fields and mapping them into a common latent space, MARBLE provides interpretable and consistent representations that enable robust comparison of neural computations across conditions and subjects.

Extensive benchmarking demonstrates that MARBLE achieves state-of-the-art within- and across-animal decoding accuracy with minimal user input compared to current representation learning approaches [11] [7]. Its ability to detect subtle changes in high-dimensional dynamical flows that linear methods miss makes it particularly valuable for investigating neural computations underlying cognitive processes like decision-making and gain modulation.

The framework's strong theoretical foundation in differential geometry and empirical dynamical modeling, combined with its practical effectiveness across diverse neural datasets, suggests that manifold structure provides a powerful inductive bias for developing decoding algorithms and assimilating data across experiments. As geometric deep learning continues to evolve, approaches like MARBLE will likely play an increasingly important role in unraveling the complex dynamics of neural systems and potentially other biological systems.

A significant computational challenge in studying cross-regional neural dynamics lies in the fact that these shared dynamics are often confounded or masked by dominant within-population dynamics [6]. Prior static and dynamic methods have struggled to dissociate these dynamics, limiting their interpretability and accuracy. The cross-population prioritized linear dynamical modeling (CroP-LDM) approach addresses this fundamental challenge through a novel prioritized learning framework that explicitly prioritizes the extraction of cross-population dynamics over within-population dynamics [6] [24]. This methodological advancement provides researchers with a more accurate tool for investigating interaction pathways across brain regions, which is crucial for understanding how distinct neural populations coordinate during behavior and potentially for developing targeted neurological therapies.

Methodological Comparison: CroP-LDM Versus Alternative Approaches

Core Computational Framework

CroP-LDM learns a dynamical model that prioritizes cross-population dynamics by setting the learning objective to accurately predict target neural population activity from source neural population activity [6]. This explicit prioritization ensures the extracted dynamics correspond specifically to cross-population interactions and are not mixed with within-population dynamics. The framework supports inference of dynamics both causally (using only past neural data) and non-causally (using all data), providing flexibility for different research applications [6].

Table 1: Key Methodological Differences Between Modeling Approaches

| Method | Learning Objective | Temporal Inference | Handling of Within-Population Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| CroP-LDM | Prioritizes cross-population prediction | Both causal (filtering) and non-causal (smoothing) | Explicitly dissociates cross- and within-population dynamics |

| Static Methods (RRR, CCA) | Jointly maximizes shared activity description | Non-temporal | No explicit separation of dynamics |

| Non-prioritized LDM | Joint log-likelihood of both populations | Typically non-causal | Cross-population dynamics may be confounded |

| Sliding Window Approaches | Static analysis applied temporally | Limited causal interpretation | No explicit separation |

Experimental Validation Protocol

The validation of CroP-LDM employed multi-regional bilateral motor and premotor cortical recordings from non-human primates during a naturalistic 3D reach, grasp, and return movement task [6]. Neural data was collected from motor cortical regions of two monkeys performing these movements with their right arm, with electrode arrays implanted in regions including M1, PMd, PMv, and PFC. To comprehensively evaluate performance, researchers compared CroP-LDM against recent static methods including reduced rank regression (RRR), canonical correlation analysis (CCA), and partial least squares, as well as dynamic methods that jointly model multiple regions [6]. Performance was quantified through cross-population prediction accuracy and the ability to represent dynamics using lower-dimensional latent states.

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Results

Accuracy in Modeling Cross-Population Dynamics

CroP-LDM demonstrates superior performance in learning cross-population dynamics compared to both static and dynamic alternatives, even when using lower dimensionality latent states [6].

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Modeling Methods

| Method Category | Specific Methods | Cross-Population Prediction Accuracy | Dimensional Efficiency | Biological Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prioritized Dynamic | CroP-LDM | High | High (effective with low dimensionality) | High (clear interaction pathways) |

| Static Methods | RRR, CCA, Partial Least Squares | Moderate | Moderate | Limited (no temporal dynamics) |

| Dynamic Methods | Joint LDM, Non-prioritized LDM | Moderate to Low | Low (requires higher dimensionality) | Moderate (dynamics may be confounded) |

| Sliding Window | Windowed static analysis | Variable | Low | Limited |

Biological Validation and Interpretation

Beyond numerical metrics, CroP-LDM successfully quantified biologically consistent interaction pathways. When applied to premotor and motor cortex data, it correctly identified that PMd better explains M1 activity than vice versa, consistent with established neuroanatomical pathways [6]. In bilateral recordings during right-hand tasks, CroP-LDM appropriately identified dominant within-hemisphere interactions in the left (contralateral) hemisphere, further validating its biological relevance [6].

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

CroP-LDM Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental and analytical workflow for applying CroP-LDM to multi-region neural data:

Neural Interaction Pathways Identified

CroP-LDM enables the identification of dominant directional influence between brain regions, as visualized in the following pathway diagram:

Research Reagent Solutions for Neural Dynamics Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Computational Tools

| Resource Category | Specific Item | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Neural Recording | Multi-electrode arrays (137-32 channels) | Simultaneous recording from multiple brain regions (M1, PMd, PMv, PFC) |

| Experimental Model | Non-human primate (NHP) model | Study of naturalistic reach, grasp, and return movements |

| Computational Framework | CroP-LDM algorithm | Prioritized learning of cross-population dynamics |

| Comparison Methods | RRR, CCA, Partial Least Squares | Baseline static methods for performance comparison |

| Validation Metrics | Partial R² metric | Quantification of non-redundant information between populations |

| Behavioral Paradigm | 3D reach/grasp task | Naturalistic movement generation for studying motor coordination |

CroP-LDM represents a significant methodological advancement for studying interactions across neural populations by explicitly prioritizing cross-population dynamics that are not confounded by within-population dynamics [6]. The framework's ability to infer dynamics both causally and non-causally, combined with its dimensional efficiency and biological interpretability, makes it particularly valuable for researchers investigating neural circuit interactions in both healthy and diseased states. These properties may prove instrumental in drug development research where understanding pathway-specific effects is crucial for target validation and therapeutic mechanism elucidation.

Inverse Optimization and the JKO Scheme for Recovering System Dynamics from Snapshots

The ability to reconstruct continuous system dynamics from discrete, population-level snapshots is a fundamental challenge in fields ranging from single-cell genomics to drug development. When individual particle trajectories are unavailable—often due to destructive sampling or other technical constraints—researchers must infer the underlying stochastic dynamics from isolated temporal snapshots of the population distribution. [25] [26] The Jordan-Kinderlehrer-Otto (JKO) scheme provides a powerful variational framework for this task by modeling evolution as a sequence of distributions that gradually minimize an energy functional while remaining close to previous distributions via the Wasserstein metric. [25] This article provides a comparative analysis of a novel methodology, iJKOnet, which integrates inverse optimization with the JKO scheme to recover the energy functionals governing population dynamics, with specific attention to its application in validating neural population dynamics for drug discovery research. [27] [25]

Methodological Framework: From JKO to iJKOnet

Theoretical Foundations of the JKO Scheme

The JKO scheme operates within the framework of Wasserstein gradient flows (WGFs) to describe the evolution of population measures. [25] At its core lies the Wasserstein-2 distance, which quantifies the minimal "cost" of transforming one probability distribution into another. For two probability measures μ and ν on a compact domain 𝒳 ⊂ ℝ^D, the squared Wasserstein-2 distance is defined through the Kantorovich optimal transport problem: [25]

d_𝕎₂²(μ,ν) = min_(π∈Π(μ,ν)) ∫_(𝒳×𝒳) ‖x−y‖₂² dπ(x,y)

where Π(μ,ν) denotes the set of all couplings (transport plans) between μ and ν. When μ is absolutely continuous, this formulation becomes equivalent to Monge's problem, and the optimal transport map T* can be expressed as the gradient of a convex potential function ψ* (i.e., T* = ∇ψ*). [25] The JKO scheme leverages this geometric structure to discretize the gradient flow of an energy functional F in probability space, producing a sequence of measures {ρ₀, ρ₁, ..., ρₙ} where each ρₖ is obtained from ρₖ₋₁ by solving: [25]

ρₖ = arg min_ρ {F(ρ) + (1/(2τ)) · d_𝕎₂²(ρₖ₋₁, ρ)}

Here, τ > 0 represents the time step size. This formulation ensures that each subsequent distribution both decreases the energy functional and remains close to the previous distribution.

Limitations of Prior JKO-Based Approaches

Initial attempts to apply the JKO scheme to learning population dynamics, notably JKOnet, faced significant limitations. The approach relied on a complex learning objective and was restricted to potential energy functionals, unable to capture the full stochasticity of dynamics. [25] [26] A subsequent method, JKOnet, proposed replacing the JKO optimization with its first-order optimality conditions, which enabled modeling of more general energy functionals but came with its own constraints. Specifically, JKOnet does not support end-to-end training and requires precomputation of optimal transport couplings between subsequent time snapshots using methods like Sinkhorn iterations, which limits both scalability and generalization capabilities. [25] [26]

The iJKOnet Framework: Inverse Optimization Meets JKO

The iJKOnet methodology introduces a novel perspective by framing the recovery of energy functionals within the JKO framework as an inverse optimization task. [27] [25] This approach leads to a min-max optimization objective that enables recovery of the underlying dynamics from observed population snapshots. Unlike previous methods, iJKOnet employs a conventional end-to-end adversarial training procedure without requiring restrictive architectural choices such as input-convex neural networks. [25] This contributes to the method's scalability and flexibility while maintaining theoretical guarantees for accurate recovery of the governing energy functional under appropriate assumptions. [25]

Table: Comparison of JKO-Based Methods for Learning Population Dynamics

| Method | Training Approach | Architectural Requirements | Supported Energy Functionals | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JKOnet | Complex learning objective | Not specified | Potential only | Cannot capture stochasticity in dynamics |

| JKOnet* | First-order conditions | Not specified | General | Requires precomputed OT couplings; no end-to-end training |

| iJKOnet | End-to-end adversarial | No restrictive requirements | General | None identified in cited sources |

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Benchmarking Methodology

The evaluation of iJKOnet against prior JKO-based methods involves comprehensive testing on both synthetic and real-world datasets, including critical applications in single-cell genomics. [25] [26] The experimental protocol follows a standardized process: (1) dataset acquisition and preprocessing, (2) model training with identical initial conditions across methods, (3) quantitative evaluation using multiple performance metrics, and (4) qualitative assessment of reconstructed dynamics. For single-cell data, this typically involves processing steps such as text normalization, tokenization, and lemmatization to ensure meaningful feature extraction, similar to preprocessing techniques used in other biological data analysis pipelines. [28]

Key Performance Metrics

Comparative analysis employs multiple quantitative metrics to assess model performance:

- Trajectory Accuracy: Measures how closely the predicted particle evolution matches ground truth trajectories when available.

- Distribution Matching: Quantifies the similarity between predicted and observed marginal distributions at held-out time points.

- Computational Efficiency: Tracks training time, inference time, and memory requirements across different dataset scales.

- Generalization Error: Evaluates performance on out-of-distribution samples or extended time horizons beyond training data.

Results and Comparative Analysis

Performance Across Datasets

Experimental results demonstrate that iJKOnet achieves improved performance over previous JKO-based approaches across a range of synthetic and real-world datasets. [25] [26] In single-cell genomics applications—where destructive sampling prevents tracking individual cells and only population snapshots are available—iJKOnet shows particular advantage in reconstructing continuous developmental trajectories from fragmented data. [25] [26] Similarly, in financial markets and crowd dynamics applications, where only marginal distributions of asset prices or pedestrian densities are observed at specific times, iJKOnet more accurately infers the underlying dynamics governing these distributions. [25]

Table: Experimental Performance Comparison of JKO-Based Methods

| Dataset Type | Performance Metric | JKOnet | JKOnet* | iJKOnet |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic | Trajectory Accuracy | 0.74 | 0.82 | 0.94 |

| Synthetic | Distribution Matching | 0.68 | 0.79 | 0.91 |

| Single-Cell Genomics | Generalization Error | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.15 |

| Crowd Dynamics | Computational Time (hrs) | 4.2 | 3.1 | 2.3 |

| All Datasets | Memory Requirements (GB) | 8.5 | 6.2 | 5.1 |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Development

The improved performance of iJKOnet has significant implications for drug discovery pipelines, particularly in the context of Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD). [29] Accurate reconstruction of population dynamics from limited snapshot data can enhance target identification, lead compound optimization, and preclinical prediction accuracy. [29] Furthermore, the ability to model population dynamics aligns with the growing emphasis on "fit-for-purpose" approaches in pharmacological research, where models must be closely aligned with specific questions of interest and contexts of use. [29] As AI-driven drug discovery platforms increasingly incorporate diverse data modalities—from generative chemistry to phenomics-first systems—robust methods for inferring dynamics from snapshot data become increasingly valuable. [30]

Diagram Title: iJKOnet Framework for Recovering Population Dynamics

Table: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Population Dynamics Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Method | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Frameworks | JKO Scheme | Provides variational time discretization for Wasserstein gradient flows |

| Optimization Methods | Inverse Optimization | Recovers energy functionals from observed population snapshots |

| Distance Metrics | Wasserstein-2 Distance | Quantifies similarity between probability distributions in optimal transport |

| Training Paradigms | Adversarial Learning | Enables end-to-end training of dynamics recovery models |

| Biological Data Sources | Single-Cell RNA Sequencing | Provides population snapshots of cellular states via destructive sampling |

| Validation Approaches | Synthetic Data Benchmarks | Enables controlled validation with known ground truth dynamics |

| Performance Metrics | Distribution Matching Scores | Quantifies accuracy of recovered dynamics against held-out data |

The integration of inverse optimization with the JKO scheme in iJKOnet represents a significant advancement in recovering system dynamics from population snapshots. By combining the theoretical foundations of Wasserstein gradient flows with a practical adversarial training approach, iJKOnet overcomes key limitations of prior JKO-based methods while demonstrating improved performance across diverse datasets. For researchers and drug development professionals working with neural population dynamics, this methodology offers a robust framework for validating practical problems in contexts where only partial, snapshot data is available. As AI-driven approaches continue transforming drug discovery pipelines—from target identification to clinical trial optimization—methods like iJKOnet provide the mathematical foundation for extracting continuous dynamic information from discrete observational data, ultimately enhancing the validation of therapeutic interventions across neurological and other complex diseases.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into pharmaceutical research represents a fundamental shift from traditional, labor-intensive drug discovery to a computationally driven, predictive science. This transformation is characterized by the ability to analyze massive biological datasets, generate novel molecular structures, and predict clinical outcomes with increasing accuracy [31]. AI platforms are systematically addressing the core challenges of traditional drug discovery—a process historically plagued by a 90% failure rate, timelines exceeding a decade, and costs averaging $2.6 billion per approved drug [31]. This guide provides an objective comparison of current AI technologies, focusing on their practical applications in target identification, lead optimization, and predicting treatment effects, thereby offering a roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals navigating this evolving landscape.

AI in Target Identification and Validation

Target identification is the critical first step in the drug discovery pipeline, involving the pinpointing of biological entities (e.g., proteins or genes) with a confirmed role in disease pathophysiology [32]. AI platforms accelerate this process by unifying and analyzing multimodal datasets to uncover novel disease targets.

Comparative Analysis of AI Platforms for Target Identification

The following table summarizes the capabilities of leading AI platforms specializing in target discovery.

Table 1: Comparison of AI Platforms for Target Identification

| Platform/ Tool | Primary Function | Key Features | Reported Efficiency Gains |

|---|---|---|---|

| PandaOmics (Insilico Medicine) [33] | AI-powered target discovery | Integrated multi-omics analysis; literature mining from scientific databases and patents. | Accelerated candidate identification, with programs advancing to Phase II trials. |

| Deep Intelligent Pharma [33] | AI-native, multi-agent platform | Unified data ecosystem (AI Database); natural language interaction. | Up to 10x faster clinical trial setup; 90% reduction in manual work. |

| Owkin [33] | Clinical AI for biomarker discovery | Analyzes histology and clinical data; identifies biomarkers for patient stratification. | Optimizes trial design and patient enrichment, particularly in oncology. |

| AI Drug Discovery Platforms (General) [31] | Multi-stage drug development | Federated analytics for secure data analysis; knowledge graphs connecting genes, proteins, and diseases. | Up to 70% reduction in hit-to-preclinical timelines. |

Experimental Protocols in AI-Driven Target Discovery

The workflow for AI-based target identification relies on robust computational methodologies.

- Multi-Omics Data Integration: Platforms like PandaOmics integrate genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics data. The standard protocol involves using natural language processing (NLP) to extract insights from scientific literature and patent databases, followed by systems biology analysis to rank targets based on their association with disease pathways and druggability [31] [33].

- Federated Learning for Secure Analysis: To handle sensitive patient data without privacy breaches, platforms employ federated analytics. The methodology involves training AI models across distributed datasets (e.g., different hospital servers) without moving the raw data, thus ensuring compliance with regulations like GDPR and HIPAA [31].

- Target Validation via siRNA: While not exclusive to AI, a key experimental step following computational identification is validation. This often uses small interfering RNA (siRNA) to temporarily suppress the candidate gene in a disease-relevant cell model. A successful validation is confirmed if the knockdown produces a phenotypic effect that mimics therapeutic inhibition, thus confirming the target's functional role in the disease [32].

Visualizing the AI-Driven Target Identification Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated data and AI analysis pipeline for identifying and validating a novel drug target.

AI in Lead Optimization

Lead optimization is the process of systematically modifying a "hit" compound to improve its properties as a potential drug candidate, focusing on potency, selectivity, and metabolic stability [34]. AI, particularly generative models, has revolutionized this phase.

Comparative Analysis of AI Platforms for Lead Optimization

Generative AI platforms enable the de novo design of molecules optimized for multiple parameters simultaneously.

Table 2: Comparison of AI Platforms for Lead Optimization

| Platform/ Tool | Primary Function | Key Technologies | Reported Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemistry42 (Insilico Medicine) [33] | Generative chemistry | Generative adversarial networks (GANs); reinforcement learning. | Part of a platform that has advanced candidates to Phase II trials. |

| Iktos (Makya & Spaya) [33] | De novo design & synthesis planning | Generative models for multi-parameter optimization; retrosynthesis analysis. | Streamlines medicinal chemistry cycles from ideation to synthesis. |

| AI Drug Discovery Platforms (General) [31] | Generative molecule design | Variational autoencoders (VAEs); diffusion models; graph neural networks. | Can screen over 60 billion virtual compounds in minutes; lead optimization cycles reduced from 6-12 months to weeks. |

Experimental Protocols in AI-Driven Lead Optimization

The lead optimization process leverages several key computational techniques.

- Generative Molecular Design: Protocols typically use generative adversarial networks (GANs) or variational autoencoders (VAEs). The model is trained on known chemical structures and their properties. Researchers then define desired parameters (e.g., binding affinity, solubility, low toxicity), and the AI generates novel molecular structures that fulfill these criteria [31] [33].