Optimizing Frequency Bands for Motor Imagery EEG Feature Extraction: A Guide for Enhanced BCI Performance

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced strategies for optimizing frequency bands in motor imagery (MI) electroencephalography (EEG) feature extraction, tailored for researchers and biomedical professionals.

Optimizing Frequency Bands for Motor Imagery EEG Feature Extraction: A Guide for Enhanced BCI Performance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced strategies for optimizing frequency bands in motor imagery (MI) electroencephalography (EEG) feature extraction, tailored for researchers and biomedical professionals. It explores the neurophysiological foundations of sensorimotor rhythms and the critical role of event-related desynchronization (ERD) and synchronization (ERS). The scope extends to current methodological approaches, including subject-specific band selection and hybrid deep learning models, while addressing key challenges like inter-subject variability and signal non-stationarity. It further covers validation techniques and comparative analyses of optimization algorithms, synthesizing findings to outline future directions for clinical translation in neurorehabilitation and drug development.

The Neurophysiological Basis of Motor Imagery Frequency Bands

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are sensorimotor rhythms and where do they originate? Sensorimotor rhythms, specifically the mu (8-13 Hz) and beta (13-25 Hz) rhythms, are synchronized patterns of electrical activity generated by large numbers of neurons in the sensorimotor cortex—the brain region controlling voluntary movement [1] [2]. These oscillations are most prominent when the body is physically at rest. The mu rhythm is thought to originate slightly more posteriorly, in the postcentral gyrus (related to somatosensory processes), while the beta rhythm originates more anteriorly, in the precentral gyrus (associated with motor functions) [1].

2. What is the functional significance of ERD and ERS? Event-Related Desynchronization (ERD) refers to a decrease in mu or beta power, reflecting cortical activation during movement preparation, execution, or observation [1]. It indicates the engagement of neural networks for information processing. Conversely, Event-Related Synchronization (ERS) refers to a power increase above baseline levels, often observed after movement termination [1]. Beta ERS (or "beta rebound") is particularly pronounced and is interpreted as a return to an cortical "idling" state or active inhibition of the motor cortex following movement [1].

3. How do sensorimotor rhythms change with aging? In older adults, mu/beta activity shows distinct changes compared to younger adults [1]. These include increased ERD magnitude during voluntary movement, an earlier beginning and later end of the ERD period, a more symmetric ERD pattern across brain hemispheres, and substantially reduced beta ERS (rebound) after movement [1]. Older adults also tend to recruit wider cortical areas during motor tasks [1].

4. Why is my motor imagery experiment yielding inconsistent results? Inconsistent results can stem from several factors. Individual variability in the exact frequency bands is common; using a standardized subject-specific band selection method based on individual ERD patterns can improve consistency [3]. Artifacts from eye movements (EOG) or muscle activity (EMG) can contaminate EEG signals [4] [5]. Furthermore, participant factors such as age [1] or clinical conditions can affect rhythm patterns and should be accounted for in your experimental design.

5. What are the best practices for removing ECG artifacts from EMG signals? ECG contamination is a common issue when recording EMG from upper trunk muscles. Effective removal often requires a multi-step approach. Adaptive subtraction methods involve QRS complex detection, forming an ECG template by averaging complexes, and subtracting this template from the contaminated signal [6]. This method has demonstrated performance with a cross-correlation of 97% between cleaned and pure EMG signals [6]. Advanced filtering techniques like Feed-Forward Comb (FFC) filters can also effectively remove powerline interference and motion artifacts with low computational cost, making them suitable for real-time applications [7].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Quality | Poor signal-to-noise ratio | - Loose electrodes- Muscle tension artifacts- Environmental interference (50/60 Hz) | - Ensure proper skin preparation and electrode adhesion [6]- Use notch filters or FFC filters for powerline noise [7]- Apply artifact rejection algorithms [4] |

| ERD/ERS Analysis | Weak or absent ERD/ERS pattern | - Incorrect frequency band selection- Poor task timing or instruction- Contamination by artifacts | - Use subject-specific frequency band determination (e.g., based on ERD mapping) [3]- Ensure clear cues and practice sessions for participants- Implement thorough artifact removal preprocessing [4] [5] |

| Data Classification | Low motor imagery classification accuracy | - Non-stationary EEG signals- Suboptimal feature extraction- Inadequate classifier tuning | - Use advanced feature extraction (e.g., spatial-temporal features with 1D CNN and SIFT) [3]- Employ optimized classifiers (e.g., Evolutionary-optimized ELM) [3]- Validate on benchmark datasets (e.g., BCI Competition IV, EEGMMIDB) [8] |

| Subject Performance | Inability to modulate SMR | - Lack of subject engagement- Ineffective neurofeedback | - Ensure informative and engaging feedback [9]- Consider adjusting protocol (e.g., theta/SMR training) [10] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Removing ECG Artifact from EMG using Adaptive Subtraction

This protocol is essential for obtaining clean EMG signals from muscles near the torso, where ECG contamination is significant [6].

- Equipment Setup: Record sEMG signals (e.g., from pectoralis major) and a reference ECG signal (e.g., from lead V4) simultaneously. Use a sampling frequency of at least 2000 Hz and band-pass filter the raw EMG from 0.3-500 Hz [6].

- Simulation & Processing:

- QRS Detection: Apply a QRS detection algorithm to the reference ECG signal to identify the timing of each heart cycle [6].

- Template Formation: Create an averaged ECG artifact template from the contaminated EMG signal by aligning and averaging the ECG complexes identified in the previous step. Using ~30 complexes is effective [6].

- Low-Pass Filtering: Apply a low-pass filter (cutoff ~50 Hz) to the ECG template to remove undesirable high-frequency artifacts [6].

- Subtraction: Subtract the filtered ECG template from the contaminated EMG signal at the location of each R-wave to obtain the cleaned EMG signal [6].

- Validation: Quantitatively validate the results by calculating the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), Relative Error (RE), and Cross-Correlation (CC) between the cleaned signal and a true clean EMG recording. This method has achieved SNR of ~10.5, RE of 0.04, and CC of 97% [6].

Protocol for Suppressing Ocular Artifacts from EEG using Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD)

This data-adaptive technique is effective for removing Electro-oculogram (EOG) artifacts without distorting the underlying neural signals [4].

- Method Principle: EMD decomposes the recorded EEG signal

s(t)into a set of band-limited functions called Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs),C1(t), C2(t), ..., CM(t), and a residuerM(t)such thats(t) = C1(t) + C2(t) + ... + CM(t) + rM(t)[4]. - Implementation Steps:

- Decomposition: Decompose the multi-channel EEG data into its IMFs [4].

- Identification & Thresholding: Identify the IMFs predominantly containing the EOG artifact (typically low-frequency components). Apply an adaptive threshold to these components to suppress the artifact [4].

- Reconstruction: Reconstruct the purified EEG signal from the thresholded IMFs and the remaining unaltered IMFs [4].

- Advantages: This method requires no prior training and effectively separates the artifact from the brain signal based on its intrinsic characteristics, preserving the original EEG information better than conventional filtering [4].

Protocol for Theta/SMR Neurofeedback Training

This protocol is used in clinical research to modulate impulsivity or motor recovery by training subjects to enhance their Sensorimotor Rhythm [10].

- Setup: Record EEG from the central scalp position (Cz) referenced to the right ear mastoid, with a ground at FPz [10].

- Training Parameters: Use a protocol designed to enhance SMR (12-15 Hz) while inhibiting theta (3.5-7.5 Hz) activity. Conduct 20 training sessions, typically scheduled as two sessions per week for 10 weeks [10].

- Procedure: Provide participants with real-time auditory and/or visual feedback based on their instantaneous SMR and theta power. The goal for the participant is to learn cognitive strategies that increase SMR magnitude, a process based on operant conditioning [9] [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density EEG System | Records electrical brain activity from the scalp with high temporal resolution. Essential for ERD/ERS analysis. | Opt for systems with high sampling rates (>1000 Hz) and many electrodes for better spatial resolution [1]. |

| EMG Amplifier & Electrodes | Records muscle electrical activity. Used to validate motor execution or study muscle-cortex coupling. | Use surface electrodes with pre-gelled adhesive. Proper skin preparation (shaving, abrasion, cleaning) is critical for signal quality [6] [5]. |

| MEG/fMRI | Provides high spatial resolution for localizing the sources of mu and beta rhythms (MEG) or examining broader network activation (fMRI). | MEG is less distorted by skull/scalp than EEG [1]. fMRI has slower temporal resolution but is useful for combined investigations [4]. |

| Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) Software | Provides the platform for real-time signal processing, neurofeedback, and motor imagery classification. | Look for support for standard protocols (like Wadsworth) and the ability to implement custom classifiers and feature extraction algorithms [3] [8]. |

| Validated Behavioral Tasks | Elicits reproducible ERD/ERS responses. Common tasks include finger tapping, hand grasping, or motor imagery. | Tasks should have clear cues for preparation, execution, and rest phases to isolate movement-related potentials [1]. |

Core Concepts and Experimental Workflows

Sensorimotor Rhythm Signatures During Movement

The following diagram illustrates the typical behavior of mu and beta rhythms during a voluntary motor task, from preparation to recovery.

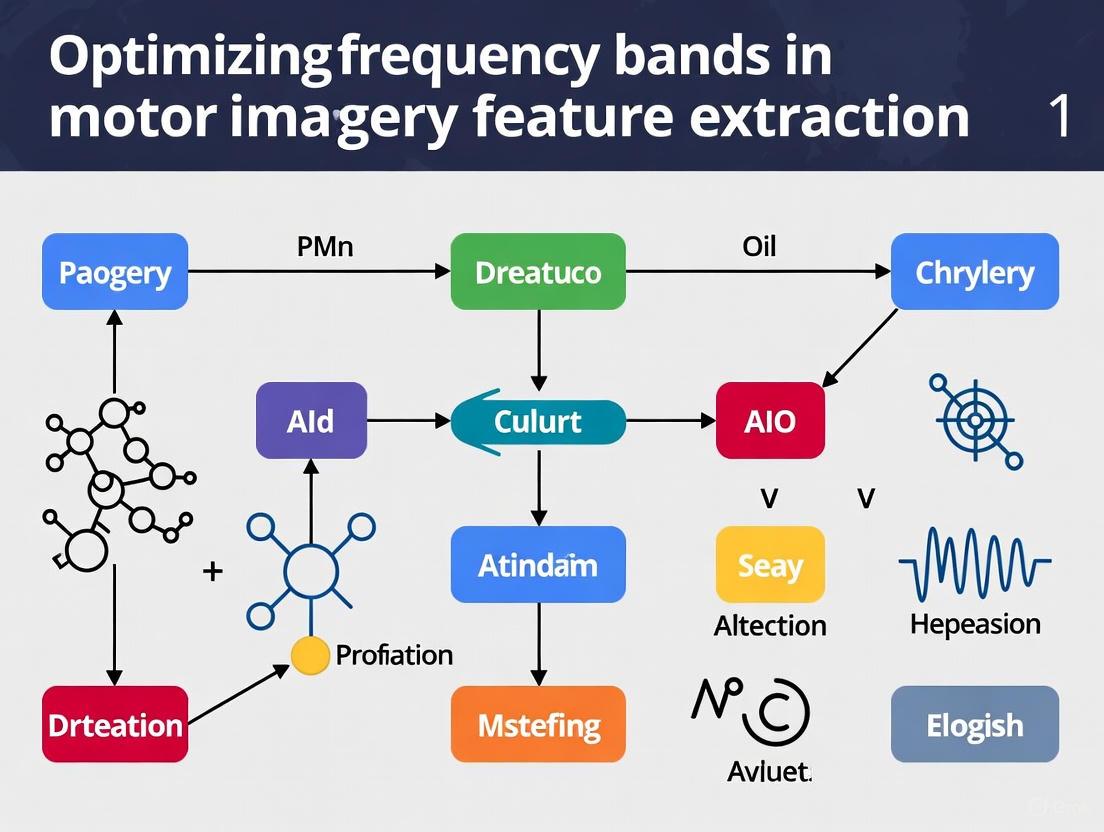

Sensorimotor Rhythm Analysis Pipeline

This workflow outlines the key steps for processing EEG data to extract and analyze sensorimotor rhythms for motor imagery classification, a common goal in BCI research.

Quantitative ERD/ERS Changes in Aging

The following table summarizes key age-related changes in mu and beta rhythm activity during voluntary movement, as identified in comparative studies [1].

| Characteristic | Young Adults | Older Adults | Functional Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERD Magnitude | Moderate | Increased | Possible compensatory recruitment of additional neural resources [1]. |

| ERD Duration | Shorter | Earlier onset and later end | Altered timing of motor preparation and inhibition processes [1]. |

| ERD Topography | Contralateral focus | More symmetric/Bilateral | Age-related shift towards less lateralized brain activity during motor tasks [1]. |

| Post-Movement Beta ERS | Strong rebound | Substantially Reduced | Possibly reflects less effective cortical inhibition or idling after movement [1]. |

Event-Related Desynchronization (ERD) and Synchronization (ERS) as Key Biomarkers

Event-Related Desynchronization (ERD) and Event-Related Synchronization (ERS) are fundamental phenomena in brain oscillatory activity, representing a relative power decrease or increase, respectively, in specific electroencephalography (EEG) frequency bands in response to internal or external events [11]. On a physiological level, ERD is interpreted as a correlate of brain activation, while ERS (particularly in the alpha band) likely reflects deactivation or inhibition of cortical areas [12]. The quantification of ERD, introduced in 1977, opened a new field in brain research by demonstrating that brain oscillations play a crucial role in information processing [12].

These biomarkers are exceptionally valuable for Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) applications, especially in motor imagery (MI) tasks where users mentally simulate movements without physical execution [13]. During motor imagery of hand movements, ERD typically occurs in the mu (8-13 Hz) and beta (14-30 Hz) frequency bands over sensorimotor areas, while ERS often follows movement termination [11] [14]. The high reproducibility and subject-specific nature of ERD/ERS patterns make them particularly suitable for biometric applications and clinical BCI implementation [14].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges & Solutions

FAQ 1: Why do I observe weak or inconsistent ERD/ERS patterns in my motor imagery experiments?

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Incorrect Frequency Band Selection: ERD/ERS are highly subject-specific in their most reactive frequency components. Use subject-specific frequency band selection based on event-related desynchronization (ERD) analysis to reduce non-stationarity and improve signal relevance [13].

- High Inter-Subject Variability: This is particularly pronounced in stroke patients or clinical populations. Implement a tailored model that handles inter-subject variability and limited data availability per patient [13].

- Poor Signal Quality: Ensure proper electrode placement with impedance less than or equal to 25 kΩ for EEG recordings [15]. Use appropriate preprocessing techniques like adaptive filtering to remove artifacts from muscle movements and eye blinks [13].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the classification accuracy of motor imagery tasks for BCI applications?

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Suboptimal Feature Extraction: Relying on single-domain features may miss important information. Combine spatial and temporal features using methods like Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) with a one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (1D CNN) for a comprehensive representation of EEG signal dynamics [13] [3].

- Classifier Limitations: Standard classifiers may not handle high-dimensional, non-stationary EEG data effectively. Use optimized classification algorithms like an Enhanced Extreme Learning Machine (EELM) with hidden layer weights optimized using dynamic multi-swarm particle swarm optimization (DMS-PSO), which has achieved 97% accuracy in stroke patient MI classification [13].

- Insufficient Training Data: Incorporate data augmentation algorithms [13] and transfer learning approaches fine-tuned with subject-specific data to enhance individual adaptation [13].

FAQ 3: What factors influence ERD/ERS strength and topography during motor tasks?

- Key Influencing Factors:

- Movement Kinematics: The speed of movement execution affects ERD strength. Studies show that both mu and beta ERD during task periods are significantly weakened during isometric contractions (Hold condition) compared to repetitive movements at 1/3 Hz or 1 Hz [11].

- Kinetic Factors: Unlike speed, external kinetic loads (e.g., 0, 2, 10, and 15 kgf grasping loads) show no significant difference in ERD strength according to some studies [11], though others report longer duration of post-movement ERD/ERS under heavier loads [11].

- Psychological Factors: Individual differences such as trait anxiety can modulate the functional coupling between motor ERD and ERS, with high trait anxiety disrupting the normal correlation between β ERD and α ERS/β ERS [16].

Table 1: Motor Imagery Classification Performance Across Methodologies

| Methodology | Dataset | Subjects | Accuracy | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMS-PSO Optimized EELM with SIFT/1D-CNN [13] [3] | Stroke Patients | 50 | 97.0% | Subject-specific frequency bands, hybrid feature extraction |

| DMS-PSO Optimized EELM with SIFT/1D-CNN [13] | BCI Competition IV 1a | - | 95.0% | Evolutionary optimization, multi-domain features |

| DMS-PSO Optimized EELM with SIFT/1D-CNN [13] | BCI Competition IV 2a | - | 91.56% | Lightweight architecture, robust to non-stationarity |

| HBA-Optimized BPNN with HHT/PCMICSP [8] | EEGMMIDB | - | 89.82% | Chaotic perturbation, global convergence properties |

Table 2: ERD Modulation Factors During Hand Grasping Movements [11]

| Experimental Factor | Effect on Mu-ERD (8-13 Hz) | Effect on Beta-ERD (14-30 Hz) |

|---|---|---|

| Speed (Kinematics) | Significantly weaker during Hold vs. 1/3Hz/1Hz | Significantly weaker during Hold vs. 1/3Hz/1Hz |

| Grasping Load (Kinetics) | No significant difference across 0-15 kgf | No significant difference across 0-15 kgf |

| Interaction (Speed × Load) | No significant interaction effect | No significant interaction effect |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Standardized Protocol for Investigating ERD/ERS During Reaching Tasks

This protocol is adapted from the NeBULA dataset methodology for capturing neuromechanical biomarkers during upper limb assessment [17] [15].

Objective: To capture synchronized EEG and EMG responses during standardized reaching tasks for assessing ERD/ERS patterns.

Materials:

- High-density EEG system (e.g., ActiCHamp with 128 channels) [15]

- Surface EMG system (e.g., Cometa Waveplus with 16 wireless sensors) [15]

- Custom-designed touch panel with 9 targets featuring LED indicators and touch-sensitive covers [15]

- Synchronization system (TriggerBox for minimal latency <1 ms) [15]

- Optional: Upper limb exoskeleton for assessing assistive technology effects [15]

Procedure:

- Participant Preparation: Apply EEG electrodes according to the extended 128-channel montage (10-20 system). Place reference electrode at FCz and ground at Fpz. Maintain impedance ≤25 kΩ [15]. Apply EMG electrodes on relevant upper limb muscles (e.g., deltoid, biceps, triceps, forearm flexors/extensors) [15].

- Experimental Setup: Position participant seated or standing facing the touch panel. Ensure all targets are within full arm's reach.

- Task Execution: Participants perform 10 repetitions of three standardized reaching tasks based on motor primitives framework: Moving objects, anterior reaching, and hand-to-mouth [15]. For anterior reaching skill:

- Each trial consists of: Rest (8-10s random duration), Preparation (1s visual cue), Task (6s execution) [11].

- Participants perform point-to-point reach and reposition movements prompted by visual cues.

- Data Collection: Simultaneously record EEG (1000 Hz), EMG (2000 Hz), and touch panel events with precise synchronization [15].

- Data Analysis: Compute event-related spectral perturbation (ERSP), inter-trial coherence (ITC), and ERD/ERS for EEG. Perform time- and frequency-domain decomposition for EMG [15].

Advanced MI Classification with Evolutionary Optimization

This protocol details the methodology for achieving high classification accuracy in motor imagery tasks, particularly for clinical populations [13] [3].

Workflow Overview:

Procedure:

- Preprocessing: Implement subject-specific frequency band selection based on event-related desynchronization (ERD) analysis to reduce non-stationarity and improve signal relevance [13].

- Feature Extraction: Combine spatial and temporal features using:

- Feature Fusion: Fuse SIFT and 1D-CNN features to create a unified feature representation [13].

- Classification: Process fused features using an Enhanced Extreme Learning Machine (EELM) for preliminary classification [13] [3].

- Optimization: Fine-tune EELM's hidden layer weights using evolutionary algorithms:

- Validation: Evaluate using 10-fold cross-validation on stroke patient datasets and standard BCI competition datasets [13].

Frequency Band Optimization Strategy

Optimizing frequency bands is crucial for enhancing motor imagery feature extraction, as ERD/ERS patterns are highly subject-specific [14]. The following diagram illustrates the strategic approach to this optimization:

Key Optimization Principles:

- Subject-Specific Bands: Focus on individual reactive frequency components rather than fixed bands [14].

- Dual-Band Analysis: Simultaneously monitor both mu (8-13 Hz) and beta (14-30 Hz) bands, as they provide complementary information [11].

- Kinematic Considerations: Adapt frequency selection based on movement type, as ERD strength varies with movement speed and type (isometric vs. dynamic) [11].

- Clinical Adaptation: In stroke rehabilitation, optimize bands to enhance antagonistic ERD/ERS patterns that support activation of the stroke-affected hemisphere [14].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for ERD/ERS Research

| Item | Specification/Example | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| EEG System | ActiCHamp Plus (Brain Products) [15] | High-density EEG recording (up to 128 channels) for detailed spatial analysis of ERD/ERS |

| EMG System | Cometa Waveplus [15] | Wireless EMG recording (16 sensors) for correlating brain activity with muscle activation |

| Synchronization Hardware | TriggerBox (Brain Products) [15] | Precise device synchronization (<1 ms latency) for multimodal data alignment |

| Standardized Motor Task Platform | Custom touch panel with 9 targets [15] | Implements standardized reaching tasks based on motor primitives taxonomy |

| Robotic Assistive Device | Float exoskeleton [15] | Studies human-robot interaction and assistive technology impact on ERD/ERS |

| Evolutionary Optimization Algorithms | DMS-PSO, DE, PSO [13] | Optimizes classifier parameters for enhanced MI decoding accuracy |

| Feature Extraction Algorithms | SIFT + 1D-CNN fusion [13] | Provides comprehensive spatial-temporal feature representation |

| Public Datasets | BCI Competition IV (1a, 2a), EEGMMIDB [13] [8] | Benchmarking and validation of novel ERD/ERS classification methods |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary EEG frequency bands and their general functions? Electroencephalography (EEG) signals are categorized into specific frequency bands, each associated with distinct physiological and cognitive states. These oscillations result from the synchronized activity of millions of neurons and are fundamental to understanding brain function, especially in Motor Imagery (MI) research [18] [19] [20].

2. Why is subject-specific frequency band optimization critical in MI research? Using a fixed, wide frequency band for all subjects often leads to suboptimal results. The neural response to a motor imagery task is highly subject-specific; ERD/ERS patterns occur at different frequency bands and with different time latencies in different individuals. Optimizing bands for each subject is therefore essential for improving classification accuracy in Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) systems [21] [22].

3. What are the common challenges when working with EEG signals for MI? EEG-based MI research faces several key challenges:

- Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): EEG signals are weak and easily contaminated by biological artifacts (e.g., eye blinks, muscle activity) and environmental noise [23] [24] [19].

- Non-Stationarity and Inter-Subject Variability: The statistical properties of EEG signals change over time and vary significantly between individuals, making it difficult to develop generalized models [23] [13].

- Data Complexity: EEG datasets are typically limited in size, while deep learning models often have many parameters, leading to potential overfitting and high computational demands [23].

4. Which frequency bands are most relevant for Motor Imagery tasks? Motor imagery primarily involves changes in the mu rhythm (8-13 Hz) and the beta rhythm (13-30 Hz) over the sensorimotor cortex. These changes, known as Event-Related Desynchronization (ERD) and Event-Related Synchronization (ERS), provide the key features for classifying imagined movements [24] [22].

5. What advanced techniques can improve MI feature extraction? Advanced methods include:

- Filter Bank Common Spatial Pattern (FBCSP): This approach extracts features from multiple narrowband filters and selects optimal bands using feature selection algorithms [22].

- Deep Learning with Attention Mechanisms: Networks like HA-FuseNet use multi-scale feature extraction and hybrid attention mechanisms to improve classification accuracy and robustness to individual variability [23].

- Evolutionary Optimization: Algorithms like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) can tune classifier parameters and select subject-specific features, enhancing performance on high-dimensional EEG data [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Motor Imagery Classification Accuracy

Problem: Your model's classification accuracy for left-hand vs. right-hand MI tasks is low or unstable across subjects.

Solution: Implement a subject-specific optimization pipeline for time windows and frequency bands.

| Step | Action | Protocol/Method | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Preprocessing | Remove artifacts and prepare data. | Apply band-pass filter (e.g., 4-40 Hz). Remove artifacts using Independent Component Analysis (ICA) or other techniques [19] [22]. | Cleaner EEG data with reduced noise. |

| 2. Multi-Dimensional Segmentation | Segment data into multiple time windows and frequency bands. | Use a sliding window approach over the MI task period (e.g., 0.5-2.5s post-cue). Decompose each window into multiple frequency sub-bands (e.g., using Dual-Tree Complex Wavelet Transform) [22]. | A multi-view feature tensor containing data from various time-frequency combinations. |

| 3. Feature Extraction | Extract spatial features from each segment. | Apply Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) to each time-frequency segment to get features that maximize variance between MI classes [22]. | A comprehensive set of candidate features. |

| 4. Feature Selection | Select the most discriminative features. | Use a learning-based feature selection method like regularized neighbourhood component analysis (RNCA) to identify optimal time-frequency features without losing the multi-view data structure [22]. | A reduced, optimized set of features for classification. |

| 5. Classification & Validation | Train and validate the model. | Use a classifier like Support Vector Machine (SVM) with cross-validation. Evaluate on both within-subject and cross-subject data [23] [22]. | Improved and more robust classification accuracy. |

Diagram 1: Subject-specific optimization workflow for MI.

Issue 2: Handling High Inter-Subject Variability and Limited Data

Problem: Your BCI model performs well on some subjects but fails on others, and you have a limited number of trials per patient (common in clinical stroke applications).

Solution: Adopt a robust feature extraction and lightweight classification model designed for high variability and small datasets.

Experimental Protocol:

- Subject-Specific Band Selection: Begin by identifying the individual's ERD-reactive frequency bands instead of using a fixed band for all subjects [13].

- Hybrid Feature Extraction: Fuse features from different domains to create a comprehensive signal representation.

- Evolutionary-Optimized Classification:

- Fuse the SIFT and 1D-CNN features.

- Classify using an Enhanced Extreme Learning Machine (EELM), a fast and efficient single-layer neural network.

- Optimize the hidden layer weights of the EELM using a metaheuristic algorithm like Dynamic Multi-Swarm Particle Swarm Optimization (DMS-PSO) to enhance generalization on limited data [13].

Expected Outcome: This methodology has been shown to achieve high classification accuracy (over 90% on standard datasets) while being computationally efficient and robust to the challenges posed by clinical data [13].

EEG Frequency Band Reference Tables

Table 1: Core characteristics and functions of primary EEG frequency bands. [18] [19] [25]

| Band | Frequency Range | Associated States & Behaviors | Physiological & Cognitive Correlates | Relevance to MI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delta (δ) | 0.1 - 4 Hz | Deep, dreamless sleep (non-REM), unconsciousness, trance [18]. | Healing, regeneration, not attentive, lethargic [18]. Dominant in infants [18]. | Low relevance; peak performers suppress delta for focused tasks [18]. |

| Theta (θ) | 4 - 8 Hz | Deep relaxation, drowsiness, creativity, intuition, dreaming (REM sleep), emotional processing [18] [20]. | Healing, mind/body integration, memory, emotional experience [18] [25]. | Present during drowsiness; may be involved in implicit learning [20]. |

| Alpha (α) | 8 - 13 Hz | Relaxed alertness, calm focus, eyes closed, meditation. Peak around 10 Hz [18] [19]. | Mental resourcefulness, coordination, relaxation, bridges conscious/subconscious [18]. Mu rhythm (8-13 Hz) is central to MI, showing ERD/ERS over sensorimotor cortex [24] [25]. | |

| Beta (β) | 13 - 30 Hz | Active thinking, focus, problem-solving, alertness, anxiety [18] [19]. | Active information processing, judgment, decision making [18]. | High relevance; shows ERD/ERS during MI tasks alongside the mu rhythm [24] [22]. |

| Gamma (γ) | >30 Hz (up to 100 Hz) | Peak cognitive functioning, information processing, heightened perception, binding of sensory information [18] [19]. | High-level information integration, memory recall [18]. | Emerging relevance; may be involved in simultaneous processing of complex information [18]. |

Table 2: Advanced sub-band specifications for refined analysis. [18] [21]

| Band | Sub-Band | Frequency Range | Detailed Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha | Low Alpha | 8 - 10 Hz | Inner-awareness of self, mind/body integration, balance [18]. |

| High Alpha | 10 - 12 Hz | Centering, healing, mind/body connection [18]. | |

| Beta | Low Beta (SMR) | 12 - 15 Hz | Relaxed yet focused, integrated; lack of focus may reflect attention deficits [18]. |

| Mid Beta | 15 - 18 Hz | Thinking, aware of self & surroundings, mental activity [18]. | |

| High Beta | 18 - 30 Hz | Alertness, agitation, complex mental activity (math, planning) [18]. | |

| Optimized for Pathology | Theta (for AD) | 4 - 7 Hz | Optimal for detecting Alzheimer's Disease, similar to classical theta [21]. |

| Alpha (for AD) | 8 - 15 Hz | Provides better classification than traditional 8-12 Hz band for Alzheimer's [21]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key components for a modern MI-BCI research pipeline. [23] [24] [22]

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Data Acquisition | EEG System with Electrodes (following 10-20 system), Conductive Gel/Gold Cup Electrodes [24]. | Captures electrical brain activity from the scalp. High-quality systems with proper electrode placement are crucial for signal quality [24] [19]. |

| Core Algorithms | Common Spatial Patterns (CSP), Filter Bank CSP (FBCSP) [22]. | Extracts discriminative spatial features from MI EEG data. FBCSP works across multiple optimized frequency bands [22]. |

| Advanced Feature Extractors | 1D Convolutional Neural Networks (1D-CNN), Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT), Hybrid Attention Mechanisms [23] [13]. | Automatically learns temporal (1D-CNN) and robust spatial (SIFT) features from EEG signals. Attention mechanisms help models focus on relevant features [23]. |

| Classification Engines | Support Vector Machine (SVM), Enhanced Extreme Learning Machine (EELM) [22] [13]. | Classifies extracted features into specific MI tasks (e.g., left hand, right hand). EELM offers a fast, lightweight alternative [13]. |

| Optimization Tools | Regularized NCA (RNCA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Dynamic Multi-Swarm PSO (DMS-PSO) [22] [13]. | Selects optimal features (RNCA) and tunes classifier parameters (PSO) to handle inter-subject variability and improve model accuracy [22] [13]. |

The Impact of Kinesthetic vs. Visual Motor Imagery on Spectral Power

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental spectral power difference between kinesthetic and visual motor imagery? Kinesthetic Motor Imagery (KMI) primarily induces power suppression (Event-Related Desynchronization or ERD) in the sensorimotor mu (8-13 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) rhythms over motor cortical areas [26] [27]. In contrast, Visual Motor Imagery (VMI) elicits a more posterior pattern, with prominent power changes, including Event-Related Synchronization (ERS), in the alpha and high-beta bands within the parieto-occipital regions [28].

Q2: Which frequency bands are most discriminative for classifying KMI and VMI? The following table summarizes the key discriminative frequency bands and their topographies based on experimental findings:

Table 1: Discriminative Frequency Bands for KMI and VMI

| Imagery Modality | Key Frequency Bands | Topographical Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Kinesthetic (KMI) | Mu (8-13 Hz), Beta (13-30 Hz) [26] | Contralateral sensorimotor cortex [26] [27] |

| Visual (VMI) | Alpha, High-Beta [28] | Parieto-occipital network [28] |

Q3: Does the perspective of visual imagery (first- vs. third-person) affect spectral power? Yes, the perspective significantly modulates brain activity. First-person perspective (1pp) VMI enhances top-down modulation from the occipital cortex, while third-person perspective (3pp) VMI engages the right posterior parietal region more strongly, suggesting distinct processing mechanisms [28].

Q4: Why is my motor imagery EEG classification accuracy low, and how can I improve it? Low accuracy often stems from non-optimized frequency bands, redundant channels, or inadequate features. To improve performance:

- Employ Filter-Bank Common Spatial Patterns (FBCSP) to handle multiple, subject-specific frequency bands [29].

- Implement channel selection algorithms, such as those based on Wavelet-Packet Energy Entropy, to remove non-informative sensors and improve the signal-to-noise ratio [30].

- Use advanced feature extraction methods like Permutation Conditional Mutual Information Common Space Pattern (PCMICSP) that are robust to noise and non-stationarity [8].

Q5: Can the presence of an object in the imagined task influence motor imagery spectral power? Yes. Studies show that object-oriented motor imagery (e.g., imagining kicking a ball) produces a significantly stronger contralateral suppression in the mu and beta rhythms over sensorimotor areas compared to non-object-oriented imagery (e.g., imagining the same leg movement without a ball) [27]. This suggests that embedding a task in a meaningful, goal-oriented context can enhance the associated brain responses.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Lack of Significant ERD/ERS in the Sensorimotor Rhythms

Problem: Expected mu or beta power desynchronization is weak or absent during motor imagery tasks. Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Ineffective Imagery Instructions.

- Solution: Provide subjects with more specific, modality-driven instructions.

- For KMI: Instruct them to "focus on the feeling of muscle contraction, joint movement, and exerted force" [26].

- For VMI: Instruct them to "visualize the action as if watching a video of themselves (third-person) or from their own eyes (first-person)" [28]. Validate imagery quality with post-experiment questionnaires like the Vividness of Movement Imagery Questionnaire-2 [28].

- Solution: Provide subjects with more specific, modality-driven instructions.

- Cause 2: Suboptimal Frequency Band Selection.

- Cause 3: Contamination by Muscle Artifacts or Covert Muscle Activity.

Issue 2: Poor Classification Accuracy Between Different Motor Imagery Tasks

Problem: A machine learning model fails to distinguish between different types of motor imagery (e.g., left vs. right hand, KMI vs. VMI). Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inadequate Feature Set.

- Cause 2: Redundant EEG Channels.

- Solution: Apply a channel selection method to reduce dimensionality and improve model generalization. The Wavelet-Packet Energy Entropy difference is one effective method that quantifies a channel's spectral energy complexity and its separability between classes [30].

- Cause 3: Small and Unbalanced Dataset.

- Solution: Implement data augmentation techniques to artificially expand your training set. Use methods like Wavelet-Packet Decomposition and sub-band swapping to generate synthetic, physiologically plausible EEG trials, which has been shown to significantly improve classification accuracy [30].

Experimental Protocols & Reference Data

Protocol 1: Differentiating VMI Perspectives using Effective Connectivity

This protocol, adapted from [28], is designed to investigate the neural networks of first-person (1pp) and third-person (3pp) visual motor imagery.

- Subjects: 17 right-handed subjects with normal or corrected-to-normal vision.

- EEG Setup: 64-channel system according to the 10-10 international system.

- Paradigm:

- Cue Phase (3s): A video showing a left or right hand performing a fist-opening/closing movement from either a 1pp or 3pp perspective is displayed.

- Fixation (3s): A cross is shown on the screen.

- Imagery Phase (5s): Subjects perform VMI of the cued movement from the instructed perspective.

- Rest: A rest cue appears. Each condition (Left/Right Hand × 1pp/3pp) is repeated 20 times.

- Preprocessing: Band-pass filtering (0.1-50 Hz), common average re-referencing, and artifact removal using Independent Component Analysis (ICA).

- Analysis:

- Time-Frequency: Calculate ERD/ERS in the alpha and high-beta bands.

- Connectivity: Apply Multi-scale Symbolic Transfer Entropy to electrodes of interest (e.g., C3, C4, P5, P6, O1, O2) to compute directed information flow.

The workflow for this protocol is outlined below:

Protocol 2: Quantifying Object-Oriented vs. Non-Object-Oriented Imagery

This protocol, based on [27], measures the enhancement of sensorimotor rhythm suppression during goal-directed imagery.

- Subjects: 15 right-handed volunteers.

- EEG/EMG Setup: 128-channel EEG. EMG electrodes placed on relevant muscles (e.g., leg muscles) to monitor for covert contractions.

- Conditions:

- Object-Oriented Imagery (OI): Imagine a leg movement involving an object (e.g., kicking a ball).

- Non-Object-Oriented Imagery (NI): Imagine the same leg movement without an object.

- Visual Observation (VO): Watch a video of the movement.

- Simple Imagery (SI): Imagine the movement without any video cue.

- Trial Structure: A fixation cross (2s) is followed by a directional cue (1s), then the imagery/observation period (OI/NI/VO: 1.7s; SI: 3s).

- Preprocessing: Surface Laplacian derivation to improve spatial resolution; EMD-regression to remove ocular artifacts.

- Core Analysis: Compute ERD/ERS in mu and beta rhythms over contralateral sensorimotor areas and compare across conditions.

Table 2: Representative Classification Accuracies for MI-BCI Paradigms

| Study Focus | Feature Extraction Method | Classifier | Reported Performance | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General MI EEG Classification | PCMICSP | Optimized Back Propagation Neural Network | 89.82% Accuracy | [8] |

| Visual Imagery (VI) Task Classification | EMD + AR Model | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 78.40% Mean Accuracy | [31] |

| Multi-class MI Classification | FBCSP + Dual Attention | DAS-LSTM | 91.42% Accuracy (BCI-IV-2a) | [29] |

| MI with Channel Selection | Wavelet-packet features | Multi-branch Spatio-temporal Network | 86.81% Accuracy (with 27% channels removed) | [30] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Motor Imagery EEG Research

| Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| EEG Acquisition System | High-density systems (e.g., 64-channel); g.HIamp system [28] [27] | Records electrical brain activity from the scalp with high temporal resolution. |

| Electrode Cap | 32-128 channels following the 10-10 or 10-20 international system [31] [27] | Standardized placement of electrodes for consistent and replicable measurements. |

| Surface EMG System | Bipolar electrode placement on target muscles [26] [27] | Monitors for covert muscle contractions that could contaminate the EEG signal during imagery. |

| Stimulus Presentation Software | Psychophysics Toolbox [27] | Precisely controls the timing and presentation of visual cues and instructions. |

| Data Preprocessing Toolbox | MNE Toolkit [28] | Performs filtering, re-referencing, artifact removal (e.g., via ICA), and epoching. |

| Imagery Ability Questionnaire | Vividness of Movement Imagery Questionnaire-2 (VMIQ-2) [28] | Subjectively assesses and ensures participants' compliance and quality of imagery. |

Advanced Techniques for Frequency Band Selection and Feature Extraction

Subject-Specific Band Selection Based on Individual ERD Patterns

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Why is a fixed frequency band (e.g., 8–30 Hz) inadequate for all subjects in MI-BCI research? The sensorimotor rhythms manifested during motor imagery are highly subject-specific. The most reactive frequency bands that exhibit Event-Related Desynchronization, as well as their temporal evolution, vary significantly between individuals due to physio-anatomical differences [32]. Using a non-customized broad band can include non-reactive frequencies and noise, diluting the discriminative power of the extracted features and leading to subpar classification results [33].

FAQ 2: What are the common computational methods for optimizing subject-specific frequency bands? Several advanced methods move beyond fixed filters. The Filter Bank Common Spatial Pattern (FBCSP) algorithm decomposes the EEG signal into multiple sub-bands and selects the most discriminative ones [34] [33]. More recently, adaptive optimization algorithms, such as the Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA), directly and automatically find the optimal time-frequency segment for a subject without being constrained by a preset filter bank [33]. Another approach involves space-time-frequency (S-T-F) analysis using algorithms like Flexible Local Discriminant Bases (F-LDB) to find subject-specific reactive patterns across electrodes, time, and frequency without prior knowledge [32].

FAQ 3: How can I identify the individual ERD pattern for a new subject? A standard protocol involves recording a calibration session where the subject performs multiple trials of different motor imagery tasks (e.g., left hand, right hand). You should then perform a time-frequency analysis (e.g., using the MNE-Python toolbox [35]) on data from sensorimotor channels. By examining the power decrease (ERD) in the alpha (8-13 Hz) and beta (14-30 Hz) bands, you can identify the specific frequencies and latencies where the most prominent desynchronization occurs for that particular subject [32] [33]. This subject-specific band can then be used for feature extraction.

FAQ 4: We are getting poor classification accuracy despite using CSP. Could the frequency band be the issue? Yes. The performance of the Common Spatial Pattern (CSP) algorithm is highly dependent on the frequency band of the input signal [34] [33]. Applying CSP to a broad, non-optimized band is a common limitation. We recommend implementing a subject-specific band selection method, such as FBCSP or an adaptive time-frequency segment optimization algorithm, to improve results [33].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

The following table summarizes key methodologies from cited research for optimizing frequency bands and features.

| Method Name | Key Function | Brief Description | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Bank CSP (FBCSP) [34] [33] | Frequency Band Selection | Decomposes EEG into multiple frequency bands, applies CSP to each, and selects discriminant bands using a feature selection algorithm. | Foundational method; performance is surpassed by newer adaptive techniques [33]. |

| Dual-Tree Complex Wavelet Transform (DTCWT) & NCA [34] | Spectral-Spatial Feature Optimization | Uses DTCWT as a filter bank to get sub-bands (e.g., 8-16, 16-24 Hz). Extracts CSP features from each band and optimizes them using Neighbourhood Component Analysis (NCA). | Avg. acc. of 84.02% and 89.10% on two BCI competition datasets [34]. |

| Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA) for Time-Frequency Optimization [33] | Adaptive Time-Frequency Segment Optimization | Employs the SSA to adaptively find the optimal time window and frequency band for each subject without being limited by a preset list of segments. | Achieved 99.11% accuracy on BCI Competition III Dataset IIIa, outperforming non-customized methods [33]. |

| Adaptive Space-Time-Frequency (S-T-F) Analysis [32] | Subject-Specific S-T-F Pattern Extraction | Uses a merge/divide strategy to find discriminant time segments and frequency clusters for a multi-electrode setup, adapting to individual patterns. | Average classification accuracy of 96% across 5 subjects [32]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials and Tools for MI-EEG Research

| Item Name | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| High-Density EEG System (e.g., 118-electrode setup) | Records brain electrical activity with high spatial resolution, crucial for locating subject-specific cortical activity [32]. |

| BCI Competition Public Datasets | Provide standardized, high-quality EEG data for developing and benchmarking new algorithms (e.g., BCI Competition III IVa, IV 2b) [34] [32]. |

| MNE-Python Software Toolkit | An open-source Python package for exploring, visualizing, and analyzing human neurophysiological data, including time-frequency analysis and ERD calculation [35]. |

| EEGLAB Toolkit | An interactive MATLAB toolbox for processing continuous and event-related EEG data; offers functions for ICA, artifact removal, and spectral analysis [36]. |

| Dual-Tree Complex Wavelet Transform (DTCWT) | A nearly shift-invariant wavelet transform used as an advanced filter bank to decompose EEG signals into sub-bands with minimal artifacts [34]. |

Workflow Diagram

Subject-Specific Band Selection Workflow

Fixed vs. Adaptive Band Selection

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: The Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) from my EMD analysis appear mixed with noise or show mode mixing. How can I mitigate this? Mode mixing occurs when an IMF contains oscillations of dramatically different scales, or when similar oscillations are split across different IMFs, often due to noise or intermittent components in the EEG signal [37].

- Solution A (Ensemble EMD): Apply Ensemble EMD (EEMD). This involves adding white noise of finite amplitude to the original signal multiple times and performing EMD on each resulting signal. The ensemble mean of the corresponding IMFs is then calculated, which helps to cancel out the noise and provide a cleaner decomposition [38].

- Solution B (Hybrid Filtering): Pre-process the EEG signal with a Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) to decompose it into predefined sub-bands first. Then, apply EMD to these narrower-band signals. This confines the EMD operation to more specific frequency ranges, reducing the likelihood of mode mixing and producing more physiologically meaningful IMFs [39].

Q2: My time-frequency representation lacks clarity, or I struggle to select the optimal mother wavelet for CWT. What should I do? The choice of mother wavelet is critical as it should closely match the morphology of the signal components of interest. Inappropriate selection can lead to poor energy concentration in the time-frequency plane [39].

- Solution A (Empirical Testing): For motor imagery EEG, start with the

'dmeyer'or complex Morlet wavelet. Test several wavelets and quantitatively compare the resulting features (e.g., by checking the resulting classification accuracy in your pipeline) to identify the most discriminative one for your specific dataset [39] [38]. - Solution B (Hilbert-Huang Transform): Bypass the mother wavelet selection entirely by using the Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT). Since HHT derives its basis functions (IMFs) adaptively from the data itself, it is inherently matched to your signal. The Hilbert Spectrum of the IMFs often provides a sharper time-frequency representation for non-stationary signals like EEG compared to pre-defined wavelets [37] [8].

Q3: The final classification accuracy of my motor imagery tasks is lower than expected after implementing the hybrid pipeline. Where should I focus my optimization? Suboptimal performance can stem from multiple points in the pipeline, but feature extraction and subject-specific variability are common culprits.

- Solution A (Feature Optimization): Ensure you are extracting robust features from the time-frequency representations. Approximate Entropy is a powerful feature for reconstructed signals from IMFs or wavelet coefficients, as it quantifies signal complexity and regularity, which often changes during motor imagery [39]. Furthermore, do not rely on a fixed frequency band; use optimization algorithms like the Improved Novel Global Harmony Search (INGHS) to find the subject-specific optimal frequency band and time interval for feature extraction, which can significantly boost accuracy [40].

- Solution B (Spatial Feature Enhancement): The time-frequency features can be further enhanced by combining them with spatial filtering. Integrate methods like Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) or Source Power Coherence (SPoC) with your EMD/CWT features. This creates a rich set of spectral-spatial-temporal features that are more discriminative for the classifier [34] [38].

Q4: The computational time for the hybrid EMD-CWT-HHT process is too high for real-time application. How can I improve efficiency? The iterative sifting process of EMD and subsequent transforms are computationally intensive [37].

- Solution A (Lightweight Hybrid Models): Investigate more recent lightweight deep learning models that are designed for raw EEG or simple time-frequency inputs. Models like HA-FuseNet or EEGNet integrate attention mechanisms and efficient architectures that can achieve high accuracy without the need for overly complex preprocessing, making them more suitable for real-time systems [41].

- Solution B (Parameter Pruning and Optimized Code): Within the hybrid preprocessing, limit the number of IMFs you consider. Often, only the first few IMFs contain the most relevant information in the mu and beta rhythm bands. Use optimized and compiled libraries (e.g., in Python,

PyEMDandPyWT) and ensure your code is vectorized to avoid slow loops [39].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Hybrid DWT-EMD with Approximate Entropy for Feature Extraction

This protocol outlines a method to overcome the wide frequency band coverage of EMD by first decomposing the signal with DWT [39].

1. Preprocessing:

- Data Source: Utilize a public dataset like BCI Competition IV 2b or IIIa [34] [39].

- Channels: Focus on electrodes C3, Cz, and C4.

- Filtering: Apply a band-pass filter (e.g., 0.5-40 Hz) and a 50 Hz/60 Hz notch filter.

2. Decomposition & Reconstruction:

- DWT Decomposition: Decompose each EEG epoch using a 4-level DWT with the

'dmeyer'wavelet. This yields approximation (A4) and detail (D1-D4) coefficients. - Sub-band Selection: Identify the detail coefficients corresponding to the motor imagery-relevant mu (8-13 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) rhythms (typically found in D2, D3, D4).

- Signal Reconstruction: Reconstruct the time-domain signal for these selected sub-bands.

- EMD on Sub-bands: Apply EMD to each of the reconstructed sub-band signals to obtain their Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs).

- IMF Selection: Calculate the FFT of each IMF and select only those IMFs whose dominant spectral power falls within the mu and beta bands for final signal reconstruction.

3. Feature Extraction & Classification:

- Feature Calculation: Compute the Approximate Entropy of the reconstructed signals from the previous step.

- Classification: Feed the feature vectors into a Support Vector Machine (SVM) or Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) classifier for final motor imagery task discrimination [39].

Table 1: Representative Performance of Hybrid DWT-EMD Method

| Dataset | Channels Used | Key Features | Classifier | Reported Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCI Competition 2008 2b [39] | C3, C4 | Approximate Entropy of DWT-EMD reconstructed signals | SVM | Up to ~85% (subject-dependent) |

Protocol 2: HHT with Optimized Neural Network Classification

This protocol uses the adaptive nature of HHT for time-frequency analysis and a metaheuristic-optimized classifier for high accuracy [8].

1. Preprocessing & Decomposition:

- Data Source: Use a dataset like the EEG Motor Movement/Imagery Dataset (EEGMMIDB) [8].

- Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT):

- EMD: Decompose the preprocessed EEG signals into IMFs.

- Hilbert Spectral Analysis (HSA): Apply the Hilbert Transform to each IMF to generate the Hilbert Spectrum, providing a high-resolution time-frequency-energy distribution.

2. Feature Extraction:

- Spatio-Spectral Features: Extract features from the Hilbert Spectrum or use advanced spatial patterns like Permutation Conditional Mutual Information Common Spatial Pattern (PCMICSP), which incorporates mutual information to handle non-linear relationships and noise in EEG signals [8].

3. Classification with Optimization:

- Classifier: Employ a Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN).

- Optimization: Use the Honey Badger Algorithm (HBA) to optimize the initial weights and thresholds of the BPNN. Introduce chaotic disturbances to the solution to avoid local minima and improve convergence speed and accuracy [8].

Table 2: Representative Performance of HHT with Optimized Classifier

| Dataset | Method | Feature Extraction | Classifier | Reported Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEGMMIDB [8] | HHT + PCMICSP | Spatial-spectral features with mutual information | HBA-Optimized BPNN | 89.82% |

Workflow Visualization

Hybrid EMD-CWT-HHT Preprocessing Workflow

Experimental Validation Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Algorithms for Hybrid Preprocessing

| Tool/Algorithm | Function/Purpose | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) | Adaptive signal decomposition into Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs). | Data-driven, does not require a predefined basis; ideal for non-stationary, non-linear signals like EEG [37] [39]. |

| Ensemble EMD (EEMD) | A noise-assisted variant of EMD. | Reduces mode mixing by performing decomposition over an ensemble of signals with added white noise [38]. |

| Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT) | Provides a high-resolution time-frequency representation (Hilbert Spectrum). | Combines EMD and the Hilbert Transform. Overcomes the Heisenberg uncertainty limitation of fixed-basis transforms [37] [8]. |

| Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) | Multi-resolution analysis using filter banks. | Provides a compact representation of signal energy in time and frequency; useful for initial sub-band creation [39]. |

| Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) | Produces a scalable time-frequency map. | Excellent for visualizing and analyzing the continuous evolution of frequency components over time [38]. |

| Approximate Entropy (ApEn) | Quantifies the regularity and complexity of a time series. | Effective for short, noisy data; useful as a feature from reconstructed IMF or wavelet signals [39]. |

| Common Spatial Pattern (CSP) | Optimal spatial filtering for maximizing variance between two classes. | Extracts features highly discriminative for motor imagery tasks; can be combined with spectral methods [34] [40]. |

| Improved Novel Global Harmony Search (INGHS) | Metaheuristic optimization algorithm. | Used for finding subject-specific optimal frequency bands and time windows, enhancing CSP feature quality [40]. |

Spatio-Spectral Feature Extraction with CSP and its Advanced Variants (e.g., FBCSP, PCMICSP)

Understanding CSP and Its Core Challenge

What is the Common Spatial Pattern (CSP) algorithm and why is it fundamental to Motor Imagery (MI) research?

Common Spatial Pattern (CSP) is a spatial filtering technique used to enhance the discriminative power of EEG signals, particularly for binary classification problems like distinguishing between left-hand and right-hand motor imagery [42]. The core idea of CSP is to find spatial filters that maximize the variance of the EEG signal for one class while simultaneously minimizing it for the other class [43]. This is effective because motor imagery tasks produce event-related desynchronization (ERD) and event-related synchronization (ERS) in the sensorimotor cortex, which are changes in oscillatory power in specific frequency bands [24] [33]. By maximizing the variance difference between classes, CSP effectively enhances the ERD/ERS features, making them more separable for a classifier [43].

Why is frequency band selection a critical challenge in standard CSP?

The performance of the standard CSP algorithm is highly dependent on the selection of EEG frequency bands [43]. This is a major limitation because the ERD/ERS phenomena show significant variability in their frequency characteristics across different individuals [43] [33]. A frequency band that works well for one subject might be suboptimal for another. Using a fixed, non-customized frequency band (e.g., 8-30 Hz) often leads to subpar classification results, as it may not align with the subject-specific frequency range where their ERD/ERS is most pronounced [33].

Troubleshooting Common CSP Implementation Issues

Why does my CSP implementation sometimes produce complex-numbered filters or poor accuracy?

This serious flaw can occur when preprocessing steps, such as artifact removal using Independent Component Analysis (ICA), decrease the rank of the EEG signal [44]. The standard CSP algorithm assumes that the covariance matrices of the signal have full rank. When this assumption is violated, it can lead to errors in the CSP decomposition, resulting in spatial filters with complex numbers (which lack a clear neurophysiological interpretation) and a significant drop in classification accuracy—by up to 32% in some cases [44].

- Solution: Ensure your CSP implementation or analysis pipeline properly handles rank-deficient signals. When using toolboxes like MNE or BBCI, check the documentation for parameters related to rank estimation and regularization (

regparameter in MNE) to mitigate this issue [45] [44].

How do I choose the right number of CSP components (n_components)?

The number of components is a trade-off between retaining discriminative information and avoiding overfitting.

- Solution: There is no universal best value; it should be set via cross-validation [45]. A common starting point is 4 or 6 components (taking 2 or 3 from each class). Use a hyperparameter tuning method like grid search in combination with cross-validation on your training data to find the optimal value for your specific dataset.

When should I uselog=Trueversuslog=Falsein my CSP parameters?

The log parameter controls the feature scaling after spatial filtering.

- Use

log=True(orNone, which defaults toTrue) whentransform_into='average_power'. This applies a log transform to the feature variances, which helps standardize them and often improves classification performance [45] [46]. - Use

log=Falseonly if you are z-scoring your features later in the pipeline. logmust beNoneiftransform_into='csp_space', as you are returning the projected time-series data, not power [45].

Advanced Variants: Overcoming Frequency Band Limitations

Advanced variants of CSP have been developed primarily to tackle the critical issue of subject-specific frequency band optimization. The table below summarizes the core methodologies and their evolution.

Table 1: Comparison of Advanced CSP Variants for Frequency Band Optimization

| Variant Name | Core Methodology | Key Advantage | Reported Performance Gain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Bank CSP (FBCSP) [43] [33] | Decomposes EEG into multiple frequency bands using a filter bank, applies CSP to each, and selects discriminative features. | Automates frequency band selection from a predefined set, mitigating reliance on a single band. | Serves as a strong baseline; outperforms standard CSP. |

| Common Sparse Spectral-Spatial Pattern (CSSSP) [43] | Optimizes a finite impulse response (FIR) filter and spatial filter simultaneously. | Automatically selects subject-specific frequency bands. | Better performance than CSSP, but optimization is complex and time-consuming. |

| Transformed CSP (tCSP) [43] | Applies a transform to the CSP-filtered signals to extract discriminant features from multiple frequency bands after CSP. | Performs frequency selection after CSP filtering, which is reported to be more effective than pre-filtering. | Significantly higher than CSP (~8%) and FBCSP (~4.5%); combination with CSP achieved up to 100% peak accuracy. |

| Adaptive Time-Frequency Segment Optimization [33] | Uses an optimization algorithm (Sparrow Search Algorithm) to find subject-specific time and frequency segments. | Overcomes limitation of fixed time windows and frequency bands; fully personalized. | Achieved up to 99.11% accuracy on a BCI competition dataset, outperforming non-customized methods. |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow difference between FBCSP and the novel tCSP approach.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing and Validating FBCSP

This protocol is based on the established FBCSP method which won a BCI competition [43] [33].

- Data Acquisition: Record EEG data using a system with at least the standard 10-20 system electrode placements. Focus on channels over the sensorimotor cortex (e.g., C3, Cz, C4). Sample rate should be at least 128 Hz.

- Experimental Paradigm: Use a cue-based MI paradigm. For example, a single trial could consist of: a fixation cross (2 s), a cue indicating the MI task (e.g., left or right hand, 3-4 s), and a rest period (randomized, 1.5-2.5 s).

- Filter Bank Setup: Decompose the continuous EEG data into multiple frequency sub-bands. A common approach is to use overlapping bands covering 4-40 Hz, for example: 4-8 Hz, 8-12 Hz, ..., 36-40 Hz.

- Epoching: Segment the data from each filter band into epochs time-locked to the cue onset (e.g., 0-4 s after cue).

- CSP Application: For each frequency band and each class, calculate the spatial filters using the CSP algorithm. Typically, 2-4 spatial filters are computed for each class per band.

- Feature Extraction: For each epoch and frequency band, compute the log-variance of the CSP-filtered signals.

- Feature Selection: Use a feature selection algorithm (e.g., Mutual Information Feature Selection) to choose the most discriminative features from the pool of all features from all bands.

- Classification & Validation: Train a classifier (e.g., Linear Discriminant Analysis or SVM) on the selected features. Always validate performance using cross-validation or a held-out test set.

Protocol 2: Evaluating the Novel tCSP Method

This protocol outlines the key steps for replicating the novel tCSP method as described in recent literature [43].

- Data Preprocessing: Begin with a broad bandpass filter (e.g., 0.5-100 Hz) on the raw EEG data. Segment data into epochs based on the task cues.

- Standard CSP Filtering: Perform standard CSP on the broad-band filtered epochs to obtain spatially filtered signals.

- Post-CSP Frequency Transformation: Apply a transform (e.g., a filter bank or time-frequency analysis like Wavelet Transform) to the CSP-filtered signals to decompose them into multiple frequency bands.

- Feature Extraction: From the transformed signals in each frequency band, extract features. This could be the variance or another statistical measure of the power.

- Feature Selection & Classification: Select the most discriminative frequency band features and feed them into a classifier. The study [43] found that combining features from tCSP and standard CSP further improved performance.

The workflow for a modern, comprehensive MI-BCI pipeline incorporating these advanced concepts is shown below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Tools and Software for MI-BCI Research with CSP

| Item Name / Category | Function / Purpose | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| EEG Acquisition System | Records electrical brain activity from the scalp. | Systems from BrainVision, Neuroscan, g.tec, or portable consumer-grade headsets like Emotiv. Key parameters: number of channels, sampling rate, input impedance. |

| Electrodes & Caps | Interface for signal acquisition. | Wet electrodes (Ag/AgCl with gel) for high signal quality; dry electrodes for ease of use but more prone to artifacts [24]. Standard 10-20 system caps ensure consistency. |

| Data Processing & BCI Toolboxes | Provides implemented algorithms for CSP, preprocessing, and classification. | MNE-Python [45] [42], PyRiemann [46], BBCI Toolbox, FieldTrip, EEGLAB. Crucial to check their handling of rank-deficient data [44]. |

| Classification Algorithms | Translates extracted CSP features into class labels. | Support Vector Machine (SVM) [42] [33], Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), Random Forests. SVM with a linear kernel is a common, robust choice. |

| Regularization Parameters | Prevents overfitting and stabilizes covariance matrix estimation, especially with low-rank data. | The reg parameter in MNE's CSP [45]. Can be 'empirical', 'oas', or a shrinkage value between 0 and 1. |

| Optimization Algorithms | Automates the selection of subject-specific parameters like time-frequency segments. | Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA) [33], Particle Swarm Optimization. Used in cutting-edge research to move beyond manual parameter tuning. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

My classification accuracy is stuck at chance level. What should I check?

- Data Quality: Inspect your raw EEG signals for excessive noise or artifacts (eye blinks, muscle movement).

- Event Markers: Verify that the event markers in your data are correctly synchronized with the experimental paradigm.

- Label Alignment: Ensure the labels (

y) used inCSP.fit(X, y)correctly correspond to the epochs in your data (X). - Parameter Tuning: Review the frequency band and time interval you are using for analysis. They must align with the expected ERD/ERS response. Consider using FBCSP or adaptive optimization to find better parameters.

- Rank Deficiency: Check if your preprocessing is causing rank-deficient data and use a regularized CSP implementation [44].

How can I extend CSP for multi-class MI problems (e.g., left hand, right hand, foot)?

The standard CSP is inherently binary. Multi-class problems are typically solved by:

- One-vs-Rest (OvR) Approach: Training a separate CSP model for each class against all others, then combining the results.

- One-vs-One (OvO) Approach: Training a CSP model for every pair of classes.

- Approximate Joint Diagonalization (AJD): Using multi-class CSP extensions that find spatial filters to discriminate all classes simultaneously. This is implemented in toolboxes like PyRiemann [46].

Is CSP sensitive to artifacts in the EEG signal?

Yes, CSP is highly sensitive to artifacts because it optimizes for variance, and artifacts often have very high variance. It is crucial to include robust preprocessing steps for artifact removal, such as:

- Bandpass filtering to remove slow drifts and high-frequency noise.

- Techniques like ICA to identify and remove ocular and muscle artifacts.

- Note: Be aware that ICA can reduce the data rank, so ensure your CSP pipeline can handle this [44].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the role of CNNs and LSTMs in optimizing frequency bands for Motor Imagery EEG? CNNs are primarily used to extract robust spatial features from EEG signals, effectively handling the inherent low signal-to-noise ratio and capturing the spatial distribution of brain activity across electrode channels [47] [23]. LSTMs then model the temporal dynamics and long-range dependencies within these spatially-filtered signals, which is crucial for understanding the oscillatory nature of brain activity during motor imagery tasks [47]. When combined, particularly in hierarchical or hybrid architectures, they facilitate automated band optimization by learning to focus computational resources on the most discriminative frequency bands and time windows, moving beyond rigid, manually-defined filters [47] [48] [49].

FAQ 2: Why is my CNN-LSTM model performing poorly, and how can I improve it?

Poor performance can stem from several issues. First, incorrect tensor shapes between CNN and LSTM layers are a common problem; ensure the feature sequence is correctly formatted for the LSTM's input, often by using a TimeDistributed wrapper for the CNN when processing sequences [50]. Second, suboptimal optimizer selection significantly impacts results; research indicates that optimizers like Adagrad and RMSprop consistently perform well for EEG data across different frequency bands, while SGD can be unstable [51]. Third, ignoring subject-specific variability can limit accuracy; employing attention mechanisms or adaptive filters can help the model generalize across different individuals [47] [23].

FAQ 3: What are the key computational challenges when deploying these models? The main challenges are high computational load and model overfitting. EEG datasets are typically small, while deep learning models can have many parameters [23]. To mitigate this, use lightweight architectures (e.g., depthwise convolutions in EEGNet variants) and model compression techniques, such as reducing the number of layers or using efficient kernels, which maintain performance while lowering resource demands [23] [52]. Furthermore, focusing on the most critical frequency band (e.g., below 2kHz for some signals) reduces input data volume and computational complexity [52].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Model Inconsistencies Across Subjects

Problem: Your model achieves high accuracy for some subjects but fails on others due to the high inter-subject variability of EEG signals.

Solution:

- Implement Attention Mechanisms: Integrate spatial and temporal attention modules. These allow the model to adaptively weight features from different electrode locations and time points, making it more robust to individual differences [47] [23]. For example, a hybrid attention mechanism can improve feature representation without a prohibitive computational cost [23].

- Leverage Feature Fusion: Design a model that fuses features from multiple domains. One effective approach is to use a dual-subnetwork architecture where a CNN subnetwork (

DIS-Net) extracts fine-grained local spatio-temporal features, while an LSTM subnetwork (LS-Net) captures global contextual dependencies. Fusing their outputs creates a more comprehensive representation [23]. - Systematic Validation: Always validate your model using both within-subject and cross-subject paradigms to get a true measure of its generalizability [23].

Issue 2: Suboptimal Frequency Band Selection

Problem: Manual selection of frequency bands is inefficient and may discard informative features.

Solution:

- Adopt Automated Band Optimization Frameworks: Move beyond fixed filter banks. Implement architectures like the Common Time-Frequency-Spatial Patterns (CTFSP), which extracts sparse CSP features from multiple frequency bands and multiple time windows, allowing the model to identify the most relevant spatio-temporal-spectral patterns [48].

- Use Multi-Branch Input Architectures: Feed multiple frequency bands (e.g., Delta, Theta, Alpha, Beta, Gamma) in parallel into the network. Research shows that a multiple frequency bands parallel spatial–temporal 3D deep residual learning framework (

MFBPST-3D-DRLF) can effectively learn from entire frequency-spatial-temporal domains, with studies indicating the gamma band is often highly discriminative [49]. - Apply Group Sparse Regression: Utilize techniques like group sparse regression for subject-specific adaptive selection of the most critical frequency bands before feature extraction [49].

Issue 3: Implementation and Performance Disparities

Problem: The same model architecture yields different results when implemented in different deep learning frameworks (e.g., Keras vs. PyTorch).

Solution:

- Verify Input Data Shape and Layer Configuration: This is critical. A common error is mismanaging the data flow from convolutional layers to recurrent layers. In Keras, a

TimeDistributedlayer is often used to apply the same CNN to each time step. In PyTorch, you must ensure the tensor is correctly shaped(sequence_length, batch_size, features)before passing it to the LSTM [50] [53]. - Check Optimizer Hyperparameters: Confirm that optimizer settings (e.g., learning rate, momentum) are truly identical across frameworks. As one study found, optimizers like Adagrad and RMSprop are reliable, but their parameters need careful tuning [51] [53].

- Reproduce a Simple, Verified Model: Start by implementing a simple, well-documented CNN-LSTM model (e.g., for activity recognition) in both frameworks to isolate the source of the discrepancy before scaling up to your complex EEG model [50].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Performance of Deep Learning Models in MI-EEG Classification

| Model Name | Key Architecture Features | Dataset | Reported Accuracy | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attention-enhanced CNN-RNN [47] | CNN + LSTM + Attention Mechanisms | Custom 4-class MI Dataset | 97.24% | Demonstrated state-of-the-art accuracy via spatiotemporal feature weighting. |

| HA-FuseNet [23] | Multi-scale CNN + LSTM + Hybrid Attention | BCI Competition IV 2a | 77.89% (within-subject) | Robustness to spatial resolution variations and individual differences. |

| CTFSP [48] | Sparse CSP in Multi-band & Multi-time windows + SVM | BCI Competition III & IV | High (Outperformed benchmarks) | Effective optimization of both frequency band and time window. |

| MFBPST-3D-DRLF [49] | Multi-band 3D Deep Residual Network | SEED / SEED-IV | 96.67% / 88.21% | Single gamma band was most suitable for emotion classification. |

Table 2: Optimizer Performance Across Frequency Bands

| Optimizer | Best Performing Frequency Band | Reported Consistency | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adagrad [51] | Beta Band | High | Excels in specific band feature learning. |

| RMSprop [51] | Gamma Band | High | Achieves superior performance in the gamma band. |

| Adadelta [51] | Multiple Bands | Robust | Showed strong performance in cross-model evaluations. |

| SGD [51] | N/A | Inconsistent | Exhibited unstable and poor performance. |

| FTRL [51] | N/A | Inconsistent | Exhibited unstable and poor performance. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Computational Tools

| Item / Tool Name | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Public EEG Datasets (e.g., BCI Competition IV 2a, DeepShip) | Provide standardized, annotated data for training and benchmarking models in motor imagery and acoustic recognition tasks [23] [52]. |

| TimeDistributed Layer (Keras) / Tensor Manipulation (PyTorch) | Critical for correctly applying CNN feature extraction across each time step in a sequence before passing the output to an LSTM [50]. |

| Attention Modules (Spatial, Temporal, Channel) | Enhance model interpretability and performance by allowing the network to focus on salient features from specific electrodes, time points, or frequency channels [47] [23] [49]. |

| Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) & Variants | A classical but powerful spatial filtering method used for feature extraction, often enhanced or automated within deep learning pipelines [48]. |

| Lightweight CNN Architectures (e.g., EEGNet, Depthwise Convolution) | Reduce computational overhead and risk of overfitting, making models more suitable for real-time BCI applications [23] [52]. |

| Group Sparse Regression | A method for optimal, subject-specific frequency band selection, improving the quality of input features for the deep learning model [49]. |

Workflow and Architecture Diagrams

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guide

This technical support resource addresses common challenges in motor imagery (MI) research, specifically focusing on the fusion of time, frequency, and spatial domain features for electroencephalogram (EEG) signal analysis. The guidance is framed within the broader context of optimizing frequency bands for MI feature extraction.

Feature Extraction and Fusion

Q1: What are the primary advantages of fusing time, frequency, and spatial domain features over using a single domain?