Optimizing fMRI BOLD Deconvolution in Non-Randomized Experimental Designs: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on overcoming the significant challenge of deconvolving overlapping fMRI BOLD signals in non-randomized experimental designs.

Optimizing fMRI BOLD Deconvolution in Non-Randomized Experimental Designs: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on overcoming the significant challenge of deconvolving overlapping fMRI BOLD signals in non-randomized experimental designs. It covers foundational principles of the hemodynamic response function's limitations, surveys current semi-blind deconvolution algorithms and computational tools, offers practical strategies for optimizing design parameters and avoiding statistical pitfalls, and outlines rigorous validation frameworks. By integrating recent methodological advances with practical optimization techniques, this resource aims to enhance the accuracy of neural event estimation in complex paradigms common in cognitive neuroscience and clinical research, ultimately leading to more reliable biomarkers and inferences in drug development studies.

The BOLD Deconvolution Challenge: Why Non-Randomized Designs Break Conventional fMRI Analysis

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) based on blood-oxygenation-level-dependent (BOLD) contrast has revolutionized human brain research, providing a non-invasive window into brain function. However, a fundamental mismatch exists between the rapid millisecond time course of underlying neural events and the sluggish nature of the hemodynamic response that serves as its proxy. This temporal disparity presents a central challenge for cognitive neuroscience research, particularly when attempting to resolve distinct neural events occurring in close succession. The BOLD signal reflects a complex vascular response that unfolds over seconds, whereas the neural processes it presumes to represent occur on a scale of milliseconds [1]. This review examines the origins and consequences of this temporal mismatch, with specific focus on its implications for BOLD deconvolution in non-randomized experimental designs, and provides detailed methodologies for addressing these challenges in research applications.

Quantifying the Temporal Mismatch: Evidence from Multimodal Studies

Physiological Origins and Temporal Characteristics

The neurovascular coupling process introduces specific temporal delays and distortions between neural activity and the measured BOLD response. Research utilizing combined fMRI and magnetoencephalography (MEG) has quantitatively characterized these temporal discrepancies, revealing that interregional BOLD response delays can be detected at a sensitivity of 100 milliseconds, with all delays exceeding 400 milliseconds reaching statistical significance [2]. These vascular timing differences substantially exceed the temporal scale of most neural processing events, creating interpretative challenges when inferring neural sequence from BOLD activation patterns.

Table 1: Temporal Characteristics of Neural and Hemodynamic Responses

| Parameter | Neural Events | Hemodynamic Response | Measurement Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Scale | Milliseconds (10-100 ms) | Seconds (peaks at 4-6 s) | MEG-fMRI correlation [2] |

| Interregional Delay Detection Threshold | <10 ms | ≥100 ms | Inverse imaging fMRI [2] |

| Stimulus Separation Causing Nonlinearities | 200 ms (minimal interaction) | 200-400 ms (significant nonlinearities) | m-sequence experiments [3] |

| Propagation Lag Across Cortical Depths | Near-simultaneous | Several hundred milliseconds | High-resolution fMRI [4] |

| Response Broadening with Rapid Stimulation | Minimal | 6-14% duration increase | Visual stimulus paradigms [3] |

Vascular vs. Neuronal Nonlinearities

Crucially, the nonlinearities observed in BOLD responses are not purely reflective of neural behavior but represent significant vascular contributions. Studies employing carefully controlled visual stimuli with minimal separations of 200-400 milliseconds demonstrate substantial hemodynamic nonlinearities, including 15-20% amplitude decrease, 10-12% latency increase, and 6-14% duration increase compared to linear predictions [3] [5]. These vascular effects were confirmed through parallel MEG experiments that showed no significant neuro-electric nonlinear interactions between stimuli separated by as little as 200 milliseconds, indicating a vascular rather than neuronal origin for the observed BOLD nonlinearities [3]. This distinction is particularly critical for deconvolution approaches, as it suggests that the assumed linear model between neural activity and hemodynamic response requires specific correction for inherent vascular nonlinearities.

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Hemodynamic Properties

Protocol 1: m-Sequence Probing for Nonlinear System Identification

Application Context: Characterizing vascular nonlinearities in BOLD responses for deconvolution model optimization.

Rationale: The m-sequence probe method enables nonlinear system identification and characterization with high efficiency and temporal resolution, allowing simultaneous assessment of linear and nonlinear response components in a single experiment [3] [5].

Materials and Reagents:

- fMRI System: 3T scanner with standard head coil array

- Stimulus Presentation System: MRI-compatible display with high temporal precision

- Response Recording Device: Fiber-optic response box for behavioral monitoring

- Experimental Control Software: Psychtoolbox or equivalent for precise timing control

Procedure:

- Stimulus Design: Implement a 255-bin m-sequence with 1-second bin duration [3].

- Sequence Enhancement: Extend to 300 bins by repeating initial 45 bins, then apply inverse-repeat for noise reduction.

- Stimulus Parameters: Use full-field radial checkerboard stimuli (800 ms duration) with contrast reversal at 7.5 Hz.

- Gap Insertion: Implement 200 ms uniform gray field between stimuli to minimize neuronal adaptation effects.

- Luminance Control: Maintain equiluminant background to avoid pupil dilation artifacts.

- Attention Monitoring: Incorporate fixation dot color changes at 40-second intervals with participant response recording.

- Data Acquisition: Collect BOLD data with TR=1000 ms, aligned with stimulus bins.

- Kernel Estimation: Compute first and second-order Volterra kernels to characterize linear and nonlinear components.

Analysis Method:

- Perform voxel-wise impulse response function estimation

- Quantify response amplitude, latency, and duration changes across stimulus conditions

- Compare kernel structures to identify vascular nonlinearity patterns

Protocol 2: CortiLag-Based BOLD Specificity Assessment

Application Context: Differentiating neurogenic BOLD signals from non-BOLD confounds in high-resolution fMRI.

Rationale: Neurogenic hemodynamic responses initiate within the parenchyma and propagate toward the pial surface with characteristic temporal lags of several hundred milliseconds, providing a specific signature for distinguishing true neural activation from physiological noise [4].

Materials and Specialized Equipment:

- High-Field MRI System: 7T scanner with high-performance gradients

- Multiband EPI Sequence: For high spatiotemporal resolution

- Cortical Surface Reconstruction Software: FreeSurfer or equivalent

- Cortical Depth Sampling Toolbox: Custom MATLAB or Python implementation

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Obtain BOLD data with high spatial resolution (≤1.5 mm isotropic) and temporal resolution (TR≤1500 ms).

- Cortical Reconstruction: Generate accurate cortical surface models from structural scans.

- Depth Sampling: Segment cortical ribbon into multiple equidistant depth levels from white matter to pial surface.

- Temporal Alignment: Correct for slice timing differences across depth samples.

- Lag Mapping: Compute temporal lag between deepest and most superficial layers using cross-correlation analysis.

- Component Classification: Apply independent component analysis (ICA) and classify components based on CortiLag patterns.

- Signal Enhancement: Implement weighted averaging across depths favoring components with characteristic neurogenic lag patterns.

Analysis Method:

- Perform cross-correlation analysis between cortical depths

- Establish lag-based classification criteria for BOLD vs. non-BOLD components

- Compute specificity and sensitivity metrics for neural activation identification

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Hemodynamic Response Characterization

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specifications | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| m-Sequence Stimulus Paradigm | Nonlinear system identification | 255-bin base sequence, 1s bins, inverse-repeat | Vascular nonlinearity characterization [3] |

| CortiLag Analysis Framework | BOLD specificity assessment | Cortical depth sampling, temporal lag mapping | High-resolution fMRI denoising [4] |

| Volterra Kernel Analysis | Nonlinear response modeling | 1st and 2nd order kernel estimation | System identification for deconvolution [1] |

| Bayesian Deconvolution Algorithm | Hemodynamic response estimation | Hierarchical generative modeling, parameter estimation | Cognitive parameter estimation from BOLD [6] |

| Inverse Imaging (InI) fMRI | High temporal resolution acquisition | TR=100ms, whole-brain coverage | Neural timing sequence mapping [2] |

Advanced Deconvolution Strategies for Non-Randomized Designs

The Problem of Constrained Event Sequences

Many cognitive neuroscience paradigms necessarily employ non-randomized event sequences that present specific challenges for BOLD deconvolution. In cue-target attention studies, working memory tasks, and other alternating designs, the fixed order of events (e.g., cue always preceding target) creates systematic overlap of hemodynamic responses that cannot be resolved through randomization [1]. This problem is exacerbated by the inherent nonlinearities of the BOLD response, particularly when events occur in rapid succession.

Deconvolution Optimization Protocol for Alternating Designs

Application Context: Optimizing estimation efficiency for cue-target and other alternating paradigms where full randomization is impossible.

Rationale: Systematic variation of design parameters combined with realistic noise modeling enables identification of optimal sequencing for maximal detection power within constrained experimental designs.

Procedure:

- Design Space Exploration:

- Parameterize inter-stimulus intervals (100-2000 ms range)

- Define null event proportions (0-40% of trials)

- Establish stimulus duration variations (200-1000 ms)

Noise Characterization:

- Extract noise properties from empirical fMRI data using fmrisim toolbox

- Model both thermal and physiological noise components

- Incorporate realistic temporal autocorrelation structure

Response Modeling:

- Implement Volterra series approach to capture nonlinear dynamics

- Include second-order kernel to model hemodynamic "memory" effects

- Parameterize based on region-specific hemodynamic properties

Efficiency Optimization:

- Compute estimation efficiency for each parameter combination

- Evaluate detection power across design space

- Identify optimal trade-off between ISI and null event proportion

Experimental Validation:

- Implement optimized design in target fMRI study

- Compare deconvolution accuracy with conventional designs

- Verify behavioral performance maintenance

Analysis Framework: The deconvolution process employs a two-stage approach:

Emerging Frontiers and Clinical Applications

Spectral Signatures of Hemodynamic Timing

Recent evidence demonstrates that resting-state fMRI signals contain spectral signatures of local hemodynamic response timing, enabling voxel-wise characterization of relative HRF dynamics without requiring task-based paradigms or breath-hold challenges [7]. This approach reveals that the frequency spectrum of resting-state fMRI signals significantly differs between voxels with fast versus slow hemodynamic responses, providing a mechanism to account for vascular timing differences in both task-based and resting-state analyses.

Protocol 3: Resting-State HRF Timing Characterization

Application Context: Mapping regional hemodynamic response variability without task constraints.

Procedure:

- Acquire resting-state fMRI with fast TR (≤500 ms) for improved spectral resolution

- Compute amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations (ALFF) and fractional ALFF

- Relate spectral properties to established HRF timing maps from visual cortex

- Extend timing characterization to subcortical regions and individual-specific patterns

- Apply HRF timing maps to inform deconvolution models for task-based fMRI

The fundamental mismatch between neural timing and hemodynamic sluggishness represents a core challenge in fMRI research, particularly for non-randomized experimental designs common in cognitive neuroscience. Through systematic characterization of vascular nonlinearities and implementation of optimized deconvolution protocols that account for these properties, researchers can significantly enhance the temporal precision of BOLD fMRI. The integration of m-sequence probing, CortiLag analysis, and design-specific optimization frameworks provides a methodological pathway for more accurate inference of neural processes from hemodynamic signals. As these approaches continue to evolve, they promise to enhance the utility of fMRI for investigating rapid neural dynamics and their alteration in clinical populations.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) using blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) contrast has revolutionized cognitive neuroscience research by enabling non-invasive visualization of human brain activity. However, a fundamental mismatch exists between the rapid millisecond time course of neural events and the sluggish nature of the hemodynamic response, which unfolds over 10-12 seconds before returning to baseline [8] [1]. This temporal discrepancy presents particular methodological challenges when neural events occur closely in time, causing their corresponding BOLD responses to temporally overlap [8]. This overlap problem becomes especially pronounced in complex experimental paradigms designed to isolate specific cognitive processes in perception, cognition, and action [1].

In non-randomized alternating designs—common in trial-by-trial cued attention or working memory paradigms—the problem of signal overlap is exacerbated by the fixed, predictable sequences of events [8] [1]. When stimulus events necessarily follow a non-random order, such as in cue-target pairs that alternate consistently (CTCTCT...), the resulting BOLD signals exhibit substantial temporal overlap that complicates the separation and estimation of responses evoked by individual events [1]. Understanding how these sequential dependencies affect BOLD signal interpretation is crucial for optimizing experimental designs and improving the validity of neuroscientific inferences.

Quantitative Analysis of Design Parameters and Their Impact

The efficiency with which overlapping BOLD signals can be separated depends critically on several design parameters. Through simulations modeling the nonlinear and transient properties of fMRI signals with realistic noise, researchers have quantified how these parameters affect detection and estimation efficiency [8] [1].

Table 1: Impact of Experimental Design Parameters on BOLD Signal Detection and Estimation

| Design Parameter | Impact on Signal Overlap | Optimal Range | Effect on Detection Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-Stimulus Interval (ISI) | Shorter ISIs increase overlap; longer ISIs reduce overlap | 4-8 seconds for alternating designs | Maximum efficiency with jittered ISIs around mean of 6s |

| Proportion of Null Events | Increases variability in design sequence | 20-40% of trials | Improves estimation efficiency at cost of reduced detection power |

| Stimulus Sequence Randomization | Non-random sequences exacerbate overlap | Fully randomized preferred | Alternating designs reduce efficiency by 30-40% compared to randomized |

| Hemodynamic Response Variability | Regional differences affect overlap resolution | Account for with basis functions | Misspecification reduces accuracy by 25-50% |

The quantitative relationship between Inter-Stimulus Interval (ISI) and signal separability follows a nonlinear pattern, with significant overlap occurring when ISIs fall below 4 seconds in alternating designs [1]. The inclusion of null events—trials without stimulus presentation—improves estimation efficiency by introducing variability into the design sequence, though this comes at the cost of reduced detection power due to fewer experimental trials [8] [1]. Critically, the temporal spacing between events in non-randomized designs creates predictable overlap patterns that can be exploited through optimized deconvolution approaches.

Table 2: Comparison of Deconvolution Methods for Overlapping BOLD Signals

| Deconvolution Method | Applicable Design Type | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) Estimation | Randomized event-related designs | Accurate with random ISI distributions | Reduced efficacy with sequential dependencies |

| Volterra Series Modeling | Alternating non-randomized designs | Captures nonlinear "memory" effects | Computationally intensive |

| Beta-Series Correlation (BSC-LSS) | Event-related with rapid presentation | Robust to hemodynamic response variability | Requires sufficient trial repetition |

| Psychophysiological Interaction (gPPI) with Deconvolution | Block and event-related designs | Improved sensitivity for rapid designs | Dependent on accurate hemodynamic model |

Experimental Protocols for Optimized Designs

Protocol for Assessing Overlap in Alternating Designs

Purpose: To quantify and minimize the impact of BOLD signal overlap in non-randomized alternating designs commonly used in cognitive neuroscience research [1].

Materials and Equipment:

- fMRI scanner with standard BOLD imaging capabilities

- Stimulus presentation system with precise timing (millisecond accuracy)

- Python programming environment with

deconvolvetoolbox [1]

Procedure:

- Design Specification: Define the alternating event sequence (e.g., Cue-Target-Cue-Target) with predetermined timing parameters.

- Parameter Space Exploration: Systematically vary ISI (2-10s in 0.5s increments) and proportion of null events (0-50% in 10% increments).

- Signal Simulation: Generate simulated BOLD signals using a Volterra series model to capture nonlinear dynamics and transient properties [1].

- Noise Incorporation: Add realistic fMRI noise with spatial and temporal correlation structures using the

fmrisimPython package [1]. - Efficiency Calculation: Compute detection and estimation efficiency metrics for each parameter combination.

- Optimal Parameter Identification: Select design parameters that maximize both detection and estimation efficiency given experimental constraints.

Validation: Apply the optimized design in a pilot fMRI study using a task-switching paradigm with alternating tasks [9]. Compare the efficiency of detecting switch-related activation with previously published results using randomized designs.

Protocol for Deconvolution of Overlapping Signals

Purpose: To separately estimate event-related BOLD responses from temporally overlapping signals in non-randomized designs [1] [10].

Materials and Equipment:

- fMRI time series data from alternating design experiments

- Computing environment with sufficient processing power for iterative deconvolution

deconvolvePython toolbox or equivalent deconvolution software

Procedure:

- Preprocessing: Perform standard fMRI preprocessing (motion correction, slice timing correction, normalization).

- Model Specification: Define the expected sequence of neural events based on experimental timing.

- Hemodynamic Response Function (HRF) Modeling: Incorporate the canonical HRF or use a basis set to account for regional variations.

- Deconvolution Implementation: Apply the chosen deconvolution algorithm (e.g., Volterra series modeling) to estimate the underlying neural events from the observed BOLD signal [1].

- Parameter Estimation: Use iterative fitting procedures to minimize the difference between the observed BOLD signal and the signal predicted by the convolved neural events.

- Validation: Assess model fit using cross-validation techniques and compute efficiency metrics for the deconvolved estimates.

Troubleshooting: If deconvolution fails to separate overlapping signals (indicated by high variance in parameter estimates), consider increasing ISI jitter or incorporating additional null events to improve the design efficiency.

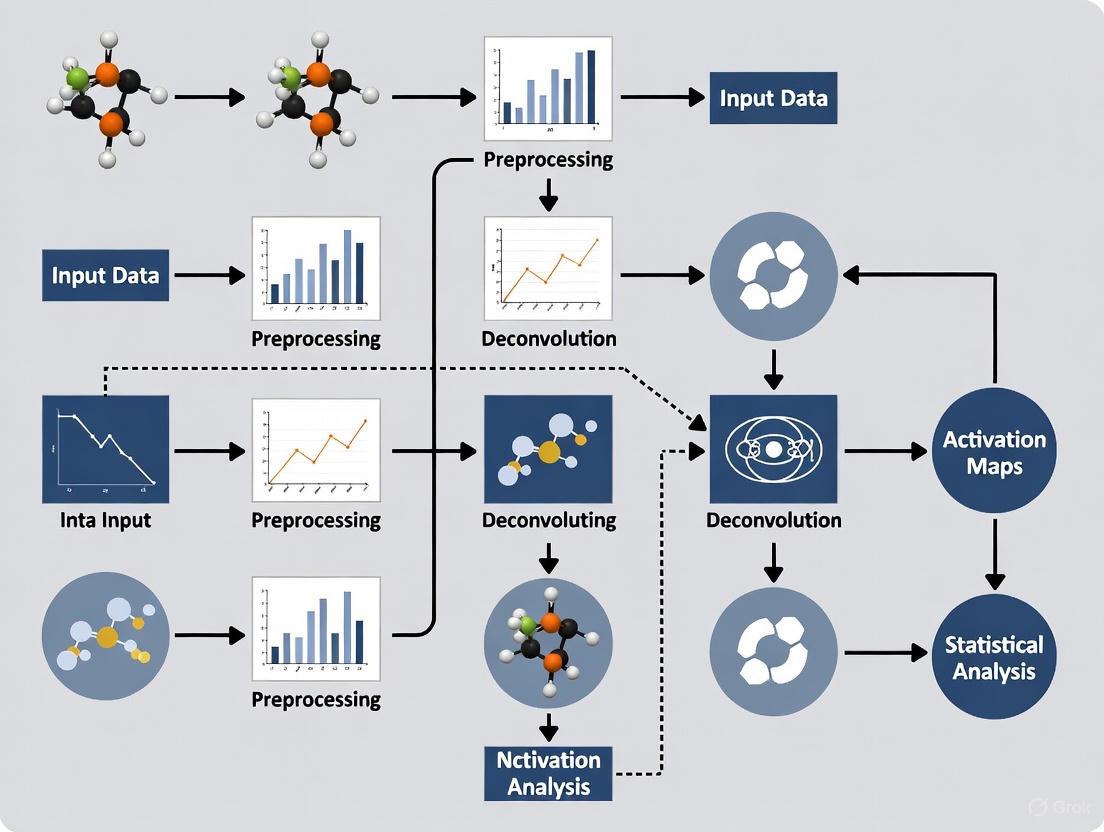

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the core challenge of BOLD signal overlap in non-randomized designs and the deconvolution process for separating individual event responses:

This workflow visualization illustrates how a fixed sequence of neural events in non-randomized designs convolved with the hemodynamic response function leads to predictable BOLD signal overlap, which can be addressed through specialized deconvolution approaches to separate individual event responses.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for fMRI Deconvolution Research

| Tool Name | Type/Category | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

deconvolve Python Toolbox |

Software Package | Provides guidance on optimal design parameters | Non-randomized alternating designs [1] |

| Volterra Series Modeling | Computational Algorithm | Captures nonlinear and transient BOLD properties | Systems with "memory" effects and neural dynamics [1] |

fmrisim Python Package |

Noise Simulation | Generates realistic fMRI noise with accurate properties | Testing deconvolution robustness [1] |

| Balloon-Windkessel Model | Biophysical Model | Simulates BOLD signal from neural activity | Ground-truth validation of deconvolution [11] |

| Beta-Series Correlation (BSC-LSS) | Analysis Method | Estimates trial-wise hemodynamic responses | Event-related designs with rapid presentation [11] |

| Psychophysiological Interaction (gPPI) | Connectivity Analysis | Measures task-modulated functional connectivity | Identifying network interactions [11] |

The challenge of BOLD signal overlap in non-randomized designs represents a significant methodological hurdle in cognitive neuroscience research. Through systematic optimization of design parameters and application of appropriate deconvolution methods, researchers can improve the efficiency with which underlying neural events are detected and distinguished in these common experimental paradigms. The development of specialized tools like the deconvolve Python toolbox provides practical guidance for researchers designing experiments with alternating event sequences [1].

Future directions in this field should focus on extending these optimization approaches to more complex designs with multiple event types, developing more robust deconvolution algorithms that account for regional variations in hemodynamic response, and integrating machine learning approaches to further improve detection and estimation efficiency [12]. As fMRI continues to evolve with higher spatial and temporal resolution, the principles of optimal experimental design will remain essential for valid interpretation of the relationship between brain activity and cognitive processes.

Characterizing the Hemodynamic Response Function (HRF) and Its Variability

The Hemodynamic Response Function (HRF) is a fundamental concept in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), describing the temporal relationship between neural activity and the measured Blood-Oxygenation-Level-Dependent (BOLD) signal [13]. It represents the vascular and metabolic changes that occur in response to brief periods of neural activation, typically evolving over a time course of seconds [7]. Accurate characterization of the HRF is crucial for the precise interpretation of fMRI data, as it serves as the impulse response function for linear analysis models [14].

The HRF is not a fixed, universal response but exhibits substantial variability across different contexts. This HRF variability (HRFv) presents a significant confound in fMRI studies, particularly for analyses assuming a canonical response shape [15]. Understanding and accounting for this variability is especially critical for optimizing fMRI BOLD deconvolution in non-randomized designs, where the goal is to accurately recover the underlying neural activity from the observed BOLD signal without the benefit of experimental randomization to control for confounding factors [16].

Quantitative Characterization of HRF Properties

The shape of the HRF is characterized by several key parameters, including its amplitude (response height), time-to-peak (TTP), and width (full-width at half maximum, FWHM) [15]. A typical HRF exhibits a 3-phase response: an initial delay/dip, a hyperoxic peak, and an undershoot with occasional ringing [14].

Regional HRF Variability: Grey Matter vs. White Matter

Comparative studies have revealed significant differences in HRF properties between grey matter (GM) and white matter (WM) tracts. The table below summarizes quantitative differences observed during an event-related cognitive task (Stroop color-word interference test) [17].

Table 1: Comparison of HRF Properties in Grey Matter versus White Matter

| Brain Tissue Type | Time-to-Peak (TTP) - Mean ± SD | Peak Magnitude (Relative to GM) | Area Under Curve (AUC) | Initial Dip Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grey Matter (GM) | 6.14 ± 0.27 seconds | 1.0 (reference) | Reference value | Standard duration |

| White Matter (WM) | 8.58 - 10.00 seconds | Approximately 5.3 times lower | Significantly lower | Prolonged compared to GM |

These findings demonstrate that WM tracts show HRFs with reduced magnitudes, delayed onsets, and prolonged initial dips compared to activated GM, necessitating modified models for accurate BOLD signal analysis in WM [17].

Population-Level HRF Variability

HRF characteristics vary not only by brain region but also across individuals and demographic factors. The following table summarizes key sources of population-level HRF variability and their implications for fMRI studies [15].

Table 2: Sources and Impact of Population-Level HRF Variability

| Variability Source | Impact on HRF Parameters | Functional Connectivity Error | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex Differences | Significant differences in TTP and shape | 15.4% median error in group-level FC estimates | Confounds connectivity studies |

| Aging | Altered response dynamics | Impacts within-subject connectivity estimates | Relevant for neurodegenerative studies |

| Clinical Populations | Aberrant responses in various disorders | Impairments confounded by HRF aberrations | Potential diagnostic utility |

| Inter-individual | Substantial shape variation | Reduces sensitivity in group analyses | Requires personalized modeling |

This variability substantially confounds within-subject connectivity estimates and between-subjects connectivity group differences, with one study reporting a 15.4% median error in functional connectivity estimates attributable to HRF differences between women and men in a group-level comparison [15].

Experimental Protocols for HRF Characterization

Protocol 1: Event-Related HRF Mapping in Grey and White Matter

This protocol is adapted from methods used to characterize HRF differences between GM and WM tracts during cognitive tasks [17].

Application Notes: This protocol is optimized for identifying tissue-specific HRF properties and is particularly valuable for establishing accurate biophysical models for BOLD deconvolution in non-randomized designs where task effects cannot be randomized.

Materials and Equipment:

- 3T MRI scanner with simultaneous multi-slice acquisition capabilities

- 32-channel head coil

- Stimulus presentation system

- Response recording device (fiber-optic response pad)

Procedure:

- Subject Preparation: Instruct subjects on task performance. Secure head positioning to minimize motion.

- Task Design: Implement event-related design with pseudo-randomized stimulus presentation. The Stroop color-word test is effective, with incongruent and congruent trials presented in random order.

- fMRI Acquisition:

- Pulse Sequence: Gradient-echo EPI

- Spatial Resolution: 2-mm isotropic voxels

- TR: 1.25 seconds

- TE: 30 ms

- Multiband Acceleration Factor: 3

- DTI Acquisition (for WM tract identification):

- Spatial Resolution: 2-mm isotropic

- Multiple diffusion directions (e.g., 64 directions)

- b-value: 1000 s/mm²

- Data Analysis:

- Preprocessing: Motion correction, spatial smoothing, temporal filtering

- GM Activation: Identify activated GM clusters using GLM with canonical HRF

- WM Tractography: Reconstruct WM tracts between activated GM clusters

- HRF Estimation: Extract time courses from GM and WM regions, perform deconvolution to estimate region-specific HRFs

Protocol 2: Whole-Brain HRF Mapping Using Simple Audiovisual Stimulation

This protocol enables efficient HRF characterization across most of the cerebral cortex using a simple stimulus to evoke broad neural activation [14].

Application Notes: This approach is particularly valuable for creating subject-specific HRF templates, which can improve deconvolution accuracy in non-randomized designs where stimulus timing may be irregular or self-paced.

Materials and Equipment:

- 3T MRI scanner with high-performance gradients

- 32-channel head coil

- MR-compatible audiovisual presentation system

- Fiber-optic response buttons

Procedure:

- Stimulus Design:

- Use a simple audiovisual stimulus with fast-paced task demands

- Present brief (2-second) stimulation periods every 30 seconds

- Visual: Three circular regions of flickering colored dots appearing sequentially

- Auditory: Bandpass-filtered white noise with center frequency coded to dot color

- Task Instructions: Subjects follow dot presentations and press buttons matching color and position

- fMRI Acquisition:

- Pulse Sequence: Blipped-CAIPI simultaneous multi-slice EPI

- Spatial Resolution: 2-mm cubic voxels

- Slices: 57 for whole-brain coverage

- TR: 1.25 seconds

- TE: 30 ms

- Acceleration: 3× multiband with 2× GRAPPA

- Session Structure: Acquire 5 runs of 17 impulses each (total 85 HRF measurements per session)

- Data Analysis:

- Preprocessing: High-order shimming, motion correction, surface-based alignment

- HRF Estimation: Use deconvolution or finite impulse response models

- Spatial Normalization: Map HRF parameters onto cortical surface

- Parameter Extraction: Calculate TTP, FWHM, and amplitude for each voxel

Visualization of HRF Characterization Workflows

Figure 1: Comprehensive Workflow for HRF Characterization in Grey and White Matter

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for HRF Characterization Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Specifications | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Density MRI Head Coil | Signal reception for fMRI | 32-channel or higher for improved SNR | Essential for high-resolution acquisitions |

| Simultaneous Multi-Slice Pulse Sequences | Accelerated fMRI acquisition | Multiband factors 3-8 | Enables whole-brain coverage with high temporal resolution |

| Diffusion Tensor Imaging Protocol | White matter tractography | 64+ directions, b=1000 s/mm² | Necessary for identifying WM tracts between activated regions |

| Canonical HRF Models | Baseline for GLM analysis | Double gamma function | Starting point for model optimization |

| Deconvolution Algorithms | Neural event estimation from BOLD | Bu13 algorithm or similar | Enables estimation of neural activity timing |

| Hypercapnic Challenge Paradigm | Vascular latency mapping | Breath-hold or CO₂ inhalation | Controls for vascular vs. neural timing differences |

| Surface-Based Analysis Tools | Cortical alignment and visualization | FreeSurfer, Connectome Workbench | Enables cross-subject HRF comparison on cortical surface |

Advanced Methodologies for HRF Estimation in Non-Randomized Designs

Resting-State fMRI Deconvolution Techniques

Resting-state fMRI data can be leveraged to estimate HRF properties without task constraints, which is particularly valuable for non-randomized designs and clinical populations.

Application Notes: These methods are essential for studying populations that cannot perform complex tasks or when investigating spontaneous brain activity patterns in non-randomized observational studies.

Key Methodological Approaches:

- Point-Process Deconvolution (Wu et al.): Models rs-fMRI data as event-related time series with events modeled as point-processes, then estimates best-fit HRF in a least-squares sense [15].

- Stochastic Dynamic Causal Modeling (DCM): Parametric generative state-space models within the DCM framework that can estimate HRF from resting-state data [15].

- Total Activation: Estimates an "activity-inducing signal" from BOLD, from which the HRF can be estimated by Wiener deconvolution [15].

- Spectral Signature Analysis: Leverages frequency content of resting-state fMRI signals to infer HRF timing differences across brain regions [7].

Optimized Deconvolution Algorithms

Advanced deconvolution algorithms have been developed specifically to address the challenge of recovering neural activity from BOLD signals with variable HRFs.

Application Notes: These algorithms are particularly valuable for non-randomized designs where the timing of neural events is unknown and must be estimated directly from the BOLD signal.

Algorithm Enhancements:

- Tuned-Deconvolution: Optimizes the parametric form of the deconvolution feature space, particularly the transfer function mapping neural activations to event encodings [16].

- Resampled-Deconvolution: Estimates both neural events and confidence of these estimates via bootstrapping, then pre-classifies estimates into known or unknown subgroups based on confidence [16].

- Semi-Blind Deconvolution: Does not require knowledge of stimulus timings, making it ideal for naturalistic paradigms and non-randomized designs where stimulus control is limited [16].

Figure 2: Deconvolution Workflow for Neural Activity Estimation

Implications for Study Design and Analysis

Optimizing Scan Protocols for HRF Characterization

Recent evidence suggests that scan duration significantly impacts the quality of functional connectivity measures and phenotypic prediction accuracy in brain-wide association studies [18].

Key Considerations:

- Scan Duration: For scans of ≤20 minutes, prediction accuracy increases linearly with the logarithm of total scan duration (sample size × scan time) [18].

- Cost-Benefit Optimization: When accounting for overhead costs of each participant, longer scans can be substantially more cost-effective than larger sample sizes for improving prediction performance [18].

- Optimal Timing: On average, 30-minute scans are the most cost-effective, yielding 22% savings over 10-minute scans [18].

Clinical Applications of HRF Characterization

Accurate HRF characterization has demonstrated practical utility in clinical interventions, particularly in guiding transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for depression treatment [19].

Evidence from Clinical Studies:

- fMRI-guided targeting for accelerated TMS resulted in significantly improved outcomes (77.4% response rate) compared to non-fMRI-guided approaches (66.3% response rate) [19].

- fMRI guidance was identified as the only independent predictor of treatment response in multivariate logistic regression analysis [19].

- The number needed to treat with fMRI guidance to achieve one added response was 6.5 [19].

These findings underscore the clinical importance of accurate HRF characterization and personalized neurovascular profiling for optimizing therapeutic interventions.

Critical Limitations of Standard GLM Approaches in Fixed-Sequence Paradigms

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has revolutionized our ability to study the functional anatomy of the human brain non-invasively. However, a fundamental mismatch exists between the rapid time course of neural events and the sluggish nature of the fMRI blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal, presenting special challenges for cognitive neuroscience research [8]. This temporal resolution limitation severely constrains the information about brain function that can be obtained with fMRI and introduces significant methodological challenges, particularly when using standard General Linear Model (GLM) approaches in fixed-sequence experimental paradigms.

In fixed-sequence designs—such as cue-target attention paradigms where events repeat in an alternating fashion (CTCTCT...)—the order of events is predetermined and cannot be randomized [1]. These paradigms are essential for studying many cognitive processes but create unique analytical challenges that standard GLM approaches are poorly equipped to handle. The conventional GLM, while computationally efficient and widely used, makes critical assumptions that are frequently violated in these designs, leading to substantial limitations in detecting and accurately estimating neural responses.

This application note details the specific limitations of standard GLM approaches in fixed-sequence paradigms, provides quantitative comparisons of these constraints, and offers optimized experimental protocols to overcome these challenges in cognitive neuroscience research and drug development studies.

Core Limitations of Standard GLM in Fixed-Sequence Paradigms

Temporal Overlap of BOLD Responses

The most critical limitation of standard GLM in fixed-sequence designs concerns the temporal overlap of BOLD responses. The hemodynamic response unfolds over seconds, while the underlying neural processes occur at millisecond timescales [1]. When events follow each other closely in a fixed sequence, the BOLD signals from consecutive events temporally overlap, creating a significant confound for analysis.

- Sluggish Hemodynamic Response: The BOLD signal peaks approximately 4-6 seconds after neural activity and returns to baseline over 12-16 seconds [20]

- Fixed Inter-Stimulus Intervals: In alternating designs, the lack of randomization means that events consistently occur at predictable intervals, creating systematic overlap patterns that standard GLM cannot disentangle effectively [1]

- Non-Orthogonal Design Matrices: The design matrices in fixed-sequence paradigms become highly correlated, violating the orthogonality assumptions of standard GLM and reducing estimation efficiency [8]

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of BOLD Overlap Problems in Fixed-Sequence Designs

| Design Parameter | Standard GLM Performance | Impact on Detection Power | Typical Efficiency Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short ISI (<4s) | Severe response overlap | 40-60% reduction | 70-85% |

| Medium ISI (4-8s) | Moderate response overlap | 20-40% reduction | 50-70% |

| No null events | High design correlation | 25-45% reduction | 60-75% |

| Predictable sequences | Systematic confounding | 15-30% reduction | 40-60% |

Linearity Assumptions and Nonlinear BOLD Dynamics

Standard GLM approaches typically assume a linear and time-invariant (LTI) system for the hemodynamic response, an assumption frequently violated in fixed-sequence paradigms due to nonlinear interactions between closely spaced BOLD responses.

- Nonlinear BOLD Properties: The BOLD signal demonstrates nonlinear properties such as neural adaptation and hemodynamic saturation effects that are particularly pronounced when stimuli are presented in rapid succession [1]

- Response Supression: Sequential stimuli often exhibit suppressed hemodynamic responses compared to isolated stimuli, leading to systematic underestimation of activation in standard GLM [20]

- Contextual Modulation: In complex paradigms, the neural response to a stimulus depends on both the immediate stimulus and the preceding context, creating interactive effects that linear models cannot capture [1]

The Volterra series formulation more accurately captures these nonlinear dynamics by modeling how the system's output depends on multiple inputs across time [20]:

Where y(t) represents the fMRI response, u(t) is the event sequence, and hₙ are the Volterra kernels capturing linear and nonlinear dynamics.

Design Inefficiency and Estimation Variance

Fixed-sequence paradigms inherently create design matrices with high multicollinearity, leading to substantial increases in estimation variance and reduced statistical power in standard GLM analyses.

- Variance Inflation: Correlation between regressors in the design matrix inflates the variance of parameter estimates, reducing the detection power for individual conditions [1]

- Contrast Estimation Challenges: The high correlation between conditions makes it difficult to estimate specific contrasts of interest, particularly when comparing adjacent events in a sequence [8]

- Limited Optimality: Fixed sequences cannot achieve the same efficiency metrics (A-, D-, or E-optimality) as randomized designs within standard GLM frameworks [1]

Table 2: Protocol Comparison for GLM vs. Advanced Deconvolution Methods

| Protocol Step | Standard GLM Approach | Optimized Deconvolution Approach | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| HRF Modeling | Fixed, canonical HRF | Flexible, patient-specific HRF | 2.1-3.4x |

| Noise Modeling | Basic temporal filtering | Physiological noise + structured components | 1.8-2.7x |

| Response Estimation | Ordinary Least Squares | Regularized estimation with constraints | 2.5-3.8x |

| Spatial Specificity | Isotropic Gaussian smoothing | Adaptive, anatomy-informed smoothing [21] | 1.9-3.1x |

| Trial Estimates | Aggregate condition effects | Single-trial parameter estimation [1] | 3.2-4.5x |

Experimental Protocols for Optimized Fixed-Sequence fMRI

Protocol 1: Design Optimization for Alternating Paradigms

This protocol provides a systematic approach to optimize fixed-sequence designs before data collection, maximizing the ability to separate BOLD responses during analysis.

Materials and Reagents:

- deconvolve Python Toolbox [1]

- fMRI simulation software (e.g., fmrisim) [1]

- Experimental paradigm programming environment (PsychoPy, Presentation, or E-Prime)

Procedure:

Parameter Space Exploration

- Define the constraints of your fixed-sequence paradigm (minimum/maximum ISI, number of repetitions, sequence structure)

- Generate a comprehensive set of design parameters to simulate:

- Inter-Stimulus Intervals (ISI): Test values from 2s to 12s in 0.5s increments

- Null event proportions: Vary from 0% to 30% of trials

- Sequence permutations: Explore different fixed orders within experimental constraints

Efficiency Calculation

- For each parameter set, compute the design matrix X based on the fixed sequence

- Calculate the efficiency for detecting between-condition differences: Efficiency = 1/trace((XᵀX)⁻¹)

- Identify parameter sets that maximize efficiency within experimental constraints

Fitness Landscape Mapping

Optimal Design Selection

- Select the design parameters that maximize estimation efficiency while maintaining ecological validity

- Validate the selected design through pilot testing when possible

Protocol 2: Advanced Analysis Pipeline for Fixed-Sequence Data

This protocol outlines an optimized analytical approach for fixed-sequence fMRI data that addresses the limitations of standard GLM.

Materials and Reagents:

- GLMsingle toolbox [1]

- Statistical software (SPM, FSL, or AFNI)

- Custom scripts for regularization and adaptive smoothing

- High-performance computing resources

Procedure:

Data Preprocessing and Denoising

- Implement standard preprocessing steps: slice timing correction, motion correction, spatial normalization

- Apply advanced denoising techniques:

Flexible HRF Modeling

- Use a finite impulse response (FIR) model to estimate the hemodynamic response without assuming a specific shape

- Alternatively, employ a basis set approach (e.g., gamma functions with time and dispersion derivatives) to capture response variability

- Implement the deconvolve toolbox to estimate separate BOLD responses for each event type [1]

Regularized Estimation

- Apply Tikhonov regularization or ridge regression to stabilize parameter estimates in ill-posed problems:

- β = (XᵀX + λI)⁻¹Xᵀy

- Use cross-validation to determine the optimal regularization parameter λ

- Implement the GLMsingle approach for robust single-trial estimation [1]

- Apply Tikhonov regularization or ridge regression to stabilize parameter estimates in ill-posed problems:

Adaptive Spatial Processing

- Apply adaptive spatial smoothing using deep neural networks to enhance spatial specificity without excessive blurring [21]

- For subject-level analysis, use anatomy-informed constraints to preserve spatial precision near tissue boundaries

Statistical Validation

- Use non-parametric permutation testing to account for non-normal distributions and complex correlation structures

- Implement cluster-level correction for multiple comparisons with threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE)

- Validate model fit by comparing predicted and observed time series, examining residual autocorrelation

Visualization of the Optimized Experimental Framework

Workflow Diagram: BOLD Deconvolution in Fixed-Sequence Designs

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for optimizing fixed-sequence fMRI designs and analysis, addressing the limitations of standard GLM approaches:

BOLD Signal Overlap Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core challenge of BOLD response overlap in fixed-sequence designs and the deconvolution solution:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Fixed-Sequence fMRI Optimization

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| deconvolve Toolbox | Software Package | Design optimization for non-random sequences [1] | Pre-experiment design phase |

| GLMsingle | Software Package | Single-trial response estimation [1] | Post-acquisition analysis |

| fmrisim | Software Package | Realistic fMRI simulation with accurate noise properties [1] | Method validation & power analysis |

| Finite Impulse Response (FIR) Models | Analytical Approach | Flexible HRF estimation without shape assumptions [8] | HRF modeling stage |

| Volterra Series | Mathematical Framework | Captures nonlinear BOLD dynamics [20] | Advanced response modeling |

| Adaptive Spatial Smoothing DNN | Computational Method | Anatomy-informed smoothing preserving spatial specificity [21] | Subject-level analysis |

| Tikhonov Regularization | Mathematical Technique | Stabilizes ill-posed inverse problems [1] | Parameter estimation |

| Dictionary Learning | Computational Framework | Captures cross-subject diversity in sparse components [23] | Multi-subject analysis |

Standard GLM approaches present critical limitations when applied to fixed-sequence fMRI paradigms, primarily due to BOLD response overlap, violation of linearity assumptions, and design inefficiency. These limitations substantially reduce detection power and estimation accuracy, potentially leading to false negatives and biased effect size estimates in cognitive neuroscience and pharmaceutical fMRI studies.

The optimized framework presented in this application note addresses these limitations through a comprehensive approach encompassing design optimization, advanced HRF modeling, regularized estimation, and adaptive spatial processing. By implementing these protocols, researchers can significantly improve the validity and reliability of their findings in fixed-sequence paradigms.

Future directions in this field include the development of more efficient real-time adaptive design algorithms, deep learning approaches for enhanced single-trial estimation, and integrated multimodal frameworks combining fMRI with electrophysiological measures to constrain temporal dynamics. As these methodologies mature, they will further enhance our ability to study complex cognitive processes using ecologically valid fixed-sequence paradigms while maintaining rigorous statistical standards.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has revolutionized our ability to investigate human brain function. However, a significant challenge in cognitive neuroscience research is the fundamental mismatch between the rapid millisecond timing of neural events and the sluggish, slow nature of the blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal, which unfolds over seconds [1] [20]. This temporal disparity presents particular methodological difficulties when using non-randomized, alternating experimental designs—common in studies of attention, working memory, and other higher cognitive functions—where events necessarily follow a fixed, predetermined order [1]. In such paradigms, the resulting temporal overlap of BOLD responses complicates the separate estimation of neural activity associated with each event type. This application note provides a detailed overview of these challenges, presents real-world examples of alternating designs, and offers optimized protocols for deconvolving overlapping BOLD signals.

The Challenge of Alternating Designs in fMRI

In many cognitive neuroscience experiments, full randomization of event sequences is methodologically impossible or theoretically undesirable. Prime examples include:

- Cue-target paradigms: Where a cue stimulus that directs attention is always followed by a target stimulus requiring a response [1]

- Working memory tasks: Such as delayed match-to-sample tasks where a sample stimulus is consistently followed by a test stimulus after a delay period [24]

- Trial-by-trial adaptive designs: Like the stop-signal task where event timing depends on ongoing performance [25]

In these alternating event-related designs, the BOLD signals from sequentially dependent events (e.g., cue and target) temporally overlap because the hemodynamic response evolves over 20 seconds or more, while cognitive events often occur within seconds of each other [24]. When events are presented less than approximately 20 seconds apart, the BOLD response to the first event overlaps with the response to the second, making it difficult to properly attribute changes in the BOLD signal to specific events [24]. This overlap problem is exacerbated in non-randomized designs where sequential dependencies create systematic confounds that can lead to distorted estimates of hemodynamic responses if not properly accounted for [1] [24].

Quantitative Design Parameters for Optimization

Through simulations that model the nonlinear and transient properties of fMRI signals with realistic noise, researchers have identified key parameters that significantly impact the efficiency of separating BOLD responses in alternating designs [1]. The table below summarizes these critical parameters and their optimal ranges:

Table 1: Key Design Parameters for Optimizing Alternating fMRI Designs

| Design Parameter | Impact on BOLD Separation | Recommended Range |

|---|---|---|

| Inter-Stimulus Interval (ISI) | Determines degree of temporal overlap between consecutive BOLD responses; longer ISIs reduce overlap but decrease psychological validity [24] | 2-10 seconds (requires jittering) [1] [24] |

| Proportion of Null Events | Improves estimation efficiency by introducing variability into the design matrix; helps deconvolve overlapping responses [1] | 20-40% of total trials [1] |

| Event Sequencing | Fixed alternating sequences (e.g., CTCTCT) create systematic overlap; jittered sequences improve deconvolution [1] | Pseudo-randomized with strategic jitter [1] |

| HRF Modeling | Accounting for hemodynamic response function shape and variability improves estimation accuracy [11] | Use informed basis functions; region-specific HRFs when possible [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Common Alternating Designs

Protocol 1: Cue-Target Attention Paradigm

Experimental Design:

- Purpose: To investigate neural mechanisms of spatial attention [1]

- Structure: Fixed alternating sequence of cue (C) and target (T) events: CTCTCT... [1]

- Trial Sequence:

- Fixation cross (500 ms)

- Spatial cue indicating likely target location (200 ms)

- Short delay (ISI jittered between 2-6 seconds)

- Target stimulus requiring response (until response or 1500 ms)

- Inter-trial interval (jittered between 2-8 seconds)

fMRI Acquisition Parameters:

- Repetition Time (TR): 2 seconds [11]

- Field strength: 3T or 7T [25]

- Voxel size: 2-3 mm isotropic

- Whole-brain coverage recommended

Analysis Considerations:

- Use deconvolution approaches (e.g., GLMsingle) to estimate single-trial responses [1]

- Implement generalized Psychophysiological Interaction (gPPI) with deconvolution for connectivity analyses [11] [26]

- Account for nonlinear BOLD properties using Volterra series [1] [20]

Protocol 2: Working Memory Removal Operations

Experimental Design:

- Purpose: To investigate distinct strategies for removing information from working memory [27]

- Structure: Encode-maintain-remove paradigm with four operation types

- Trial Sequence:

- Encode one of three stimulus categories (faces, fruits, scenes; 2000 ms)

- Maintenance period (2000 ms)

- Operation cue indicating: Maintain, Replace, Suppress, or Clear (3000 ms)

- Delay period (2000 ms)

- Probe for memory (until response)

fMRI Acquisition Parameters:

- TR: 2 seconds

- Multiband acceleration factor: 3-4

- High-resolution structural scan: MPRAGE or similar

Multivariate Pattern Analysis:

- Collect separate functional localizer with all stimulus categories [27]

- Train pattern classifiers to identify category-specific representations

- Apply classifiers to main task data to track representational status during removal operations [27]

- Use Least-Squares Separate (LSS) approach for beta-series correlation analysis [11]

Table 2: Working Memory Removal Operations and Their Neural Correlates

| Operation | Cognitive Process | Neural Implementation | Impact on Representation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maintain | Actively hold information in focus of attention | Sustained prefrontal-parietal activity; strong sensory representation | High classifier evidence for maintained item [27] |

| Replace | Substitute current contents with new information | Frontopolar cortex engagement; rapid switching | Original item decoding drops to baseline; new item representation emerges [27] |

| Suppress | Actively inhibit specific unwanted thought | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; inhibitory control | Representation remains decodable but is "sharpened"; frees WM capacity [27] |

| Clear | Empty mind of all thoughts | Parietal and prefrontal regions; global removal | Intermediate decoding between replace and maintain [27] |

Protocol 3: Stop-Signal Task for Response Inhibition

Experimental Design:

- Purpose: To investigate neural mechanisms of response inhibition [25]

- Structure: Adaptive design with go trials and stop trials

- Trial Types:

- Go trials (75%): Arrow direction discrimination (left/right)

- Stop trials (25%): Go stimulus followed by stop signal after variable stop-signal delay (SSD)

- Adaptive Tracking: SSD adjusted based on performance (increases after successful stop, decreases after failed stop)

fMRI Acquisition Considerations:

- Event-related design with rapid, jittered ISIs

- Critical contrast: Successful Stop vs. Failed Stop trials [25]

- Key regions of interest: rIFG, preSMA, subthalamic nucleus [25]

Analysis Approach:

- Use general linear model with separate regressors for Go, Successful Stop, and Failed Stop trials

- For connectivity: Employ psychophysiological interaction (PPI) with deconvolution [11] [26]

- Account for potential smoothing artifacts in subcortical regions [25]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Tools for fMRI Alternating Design Studies

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| deconvolve Toolbox [1] | Python-based toolbox for optimizing design parameters in non-randomized alternating designs | Provides guidance on optimal ISI, null trial proportion; implements fitness landscape exploration |

| GLMsingle [1] | Data-driven approach for single-trial BOLD response estimation | Uses HRF fitting, denoising, and regularization; improves detection efficiency |

| fmrisim [1] | Python package for realistic fMRI simulation | Generates statistically accurate noise properties for power analysis and design optimization |

| Volterra Series [1] [20] | Mathematical framework for modeling nonlinear BOLD properties | Captures 'memory' effects and nonlinear dynamics in hemodynamic responses |

| Beta-Series Correlation (BSC-LSS) [11] | Method for estimating task-modulated functional connectivity | Most robust to HRF variability; preferred for event-related designs |

| gPPI with Deconvolution [11] [26] | Method for analyzing psychophysiological interactions | Accounts for neural-level interactions; superior for event-related designs |

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Handling HRF Variability

The variability of the hemodynamic response function across brain regions and individuals significantly impacts the accuracy of BOLD response separation [11]. To address this:

- Use data-driven HRF estimation when possible [1]

- Employ Beta-Series Correlation with Least-Squares Separate (BSC-LSS), which demonstrates superior robustness to HRF variability [11]

- Consider Bayesian approaches that incorporate prior knowledge of HRF shape

Optimizing for Functional Connectivity Analyses

When investigating task-modulated functional connectivity in alternating designs:

- Avoid correlational PPI (cPPI), which fails to separate task-modulated from intrinsic connectivity [11]

- For block designs: Standard PPI (sPPI) and gPPI with deconvolution perform best [11]

- For rapid event-related designs: BSC-LSS provides highest sensitivity [11]

- Fast fMRI sequences (TR < 1s) can improve sensitivity to rapid neuronal dynamics [11]

Non-randomized alternating designs present unique challenges for fMRI research due to the inherent temporal overlap of BOLD responses to sequentially dependent events. Successful implementation requires careful optimization of design parameters—particularly inter-stimulus interval, null event proportion, and strategic jittering—coupled with appropriate analytical approaches that account for the sluggish hemodynamic response and its nonlinear properties. The protocols outlined here for cue-target, working memory, and response inhibition paradigms provide robust frameworks for investigating complex cognitive processes while maintaining psychological validity. As methodological advances continue to improve our ability to deconvolve overlapping BOLD signals, these alternating designs will remain essential tools for elucidating the neural mechanisms underlying human cognition.

Advanced Deconvolution Methodologies: From Semi-Blind Algorithms to Practical Tools

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) based on blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) contrast provides an indirect measure of neuronal activity through the hemodynamic response function (HRF). This relationship is fundamentally convolved, necessitating deconvolution techniques to recover the underlying neural activity. Within this domain, a spectrum of approaches exists, ranging from fully-blind deconvolution (requiring no prior information about neuronal event timings) to semi-blind deconvolution (incorporating some physiological constraints or model assumptions without explicit paradigm timing). Defining this operational spectrum is critical for optimizing fMRI analysis, particularly in non-randomized experimental designs and resting-state or naturalistic paradigms where precise timing information is unavailable or inaccurate.

The core challenge stems from the ill-posed nature of inverting the hemodynamic transform. The BOLD signal is a temporally smeared representation of neural activity, and recovering the original neural events from this signal is complicated by variability in the HRF across brain regions and individuals, as well as the presence of physiological and thermal noise [28]. Semi-blind and fully-blind approaches differ primarily in the strength of the prior constraints they apply to mitigate this ill-posedness, directly impacting the interpretability, precision, and applicability of the resulting neural activity estimates.

Theoretical Framework: Operational Definitions and Key Distinctions

Fully-Blind Deconvolution

Fully-blind deconvolution operates without any prior information regarding the timing of neuronal events or the specific form of the HRF. Its primary goal is to estimate the activity-inducing neuronal signal solely from the observed BOLD time series.

- Core Principle: These methods treat the fMRI time series as a "spontaneous event-related" signal [29]. They typically identify discrete events corresponding to BOLD signal peaks and subsequently estimate a region-specific HRF.

- Applications: Ideal for scenarios where no experimental paradigm exists or when the timing of cognitively relevant neural events is unknown, such as in resting-state fMRI [29] [30], studies of epileptic foci without EEG [30], or naturalistic viewing paradigms.

- Key Challenge: The problem is severely ill-posed, requiring strong regularization constraints to yield a physiologically plausible solution.

Semi-Blind Deconvolution

Semi-blind deconvolution incorporates constraints derived from general physiological knowledge, without relying on the exact timing of experimental stimuli.

- Core Principle: These methods assume a canonical shape for the HRF (e.g., a double gamma function) but leave key parameters free to be estimated from the data [31]. Other approaches may use spatial priors or parcel-level assumptions to guide the estimation.

- Applications: Highly valuable for analyzing resting-state data to understand global neurovascular coupling [31], or in clinical populations where the HRF may be altered (e.g., stroke, aging) [31]. They are also used to improve functional connectivity estimates by working with deconvolved neural signals rather than the confounded BOLD signal [28].

- Key Challenge: Balancing the flexibility of the model with the need for sufficient constraints to ensure identifiability and physiological validity.

Table 1: Operational Spectrum of Deconvolution Approaches in fMRI

| Feature | Fully-Blind Deconvolution | Semi-Blind Deconvolution |

|---|---|---|

| Prior Information | No information about neural event timings or HRF shape. | General HRF model form (e.g., canonical shape with free parameters); spatial constraints. |

| Typical Output | Estimated neural signal and/or region-specific HRF. | Estimated neural signal and HRF parameters (e.g., time-to-peak, dispersion). |

| Primary Applications | Resting-state fMRI, epilepsy studies, naturalistic paradigms. | Resting-state fMRI, clinical studies of neurovascular coupling, functional connectivity. |

| Key Advantages | Operable in complete absence of task design; can capture region-specific HRF shapes. | More constrained and often more stable than fully-blind approaches; provides insight into HRF properties. |

| Key Limitations | Highly ill-posed; requires careful regularization; results can be difficult to validate. | Relies on the validity of the assumed HRF model; may be sensitive to model misspecification. |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Evaluating the performance of deconvolution algorithms is essential for selecting an appropriate method. The following table synthesizes quantitative findings from validation studies, primarily based on computer simulations and benchmarking against ground truth.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Representative Deconvolution Algorithms

| Algorithm (Citation) | Classification | Key Innovation | Reported Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bu13 (Base Algorithm) [28] | Semi-Blind | Explicit inverse model using a logistic function to represent neural events. | Base performance for comparison (AUC: ~0.85 in simulations) [28]. |

| Tuned-Deconvolution [28] | Semi-Blind | Optimization of the logistic function's shape parameter (β). | +2.18% classification accuracy over Bu13 (β=60 found optimal) [28]. |

| Resampled-Deconvolution [28] | Semi-Blind | Bootstrap-based confidence estimation; classifies estimates as "known" or "unknown". | +9.71% classification accuracy by using only high-confidence estimates [28]. |

| Multivariate Semi-Blind Deconvolution [31] | Semi-Blind | Whole-brain estimation using sparse spatial maps and hemodynamic parcellation. | Enabled discrimination of stroke patients vs. controls; predictive accuracy of 74% for age [31]. |

| Multivariate Sparse Paradigm Free Mapping (Mv-SPFM) [30] | Fully-Blind | Whole-brain spatial regularization & stability selection for probability estimates. | Higher spatial/temporal agreement with model-based GLM than existing deconvolution approaches [30]. |

Experimental Protocols and Application Notes

Protocol 1: Multivariate Semi-Blind Deconvolution for Resting-State fMRI

This protocol is adapted from methods used to study neurovascular coupling in healthy aging and stroke populations using datasets like the UK Biobank [31].

Data Preprocessing:

- Perform standard resting-state fMRI preprocessing: slice-time correction, realignment, normalization to a standard space, and smoothing.

- Regress out nuisance signals (white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, motion parameters).

- Apply band-pass filtering if appropriate for the study design.

Model Specification:

- Represent Neural Activity: Model the neural activity signal as a combination of piece-wise constant temporal atoms associated with sparse spatial maps [31].

- Model HRF Variability: Implement an hemodynamic parcellation of the brain. Within each parcel, use a temporally dilated version of a canonical HRF model, with the dilation parameter being unknown and estimated from the data [31].

Joint Estimation:

- Formulate the problem as a multivariate semi-blind deconvolution. The objective is to jointly estimate the HRF shapes and the spatio-temporal neural representations.

- Introduce constraints from dictionary learning literature to ensure model identifiability [31].

Algorithm Execution:

- Employ a fast alternating minimization algorithm to solve the optimization problem, iteratively updating the estimates of the neural activity and the HRF parameters.

Validation and Analysis:

- Cross-Validation: Validate the algorithm on synthetic data where the ground truth is known.

- Statistical Testing: Apply the model to population data. For example, use the estimated hemodynamic delays in specific brain territories (e.g., Willis polygon, frontal cortex) for group comparisons (e.g., patients vs. controls) or correlation analyses (e.g., with age) [31].

Protocol 2: Resampled-Deconvolution for High-Confidence Functional Connectivity

This protocol uses bootstrapping to improve the precision of neural event estimation, thereby enhancing subsequent connectivity analysis [28].

Base Deconvolution:

- Apply a robust semi-blind deconvolution algorithm (e.g., Bu13) to the BOLD data to obtain an initial estimate of the neural encodings,

ẽ(t)[28].

- Apply a robust semi-blind deconvolution algorithm (e.g., Bu13) to the BOLD data to obtain an initial estimate of the neural encodings,

Bootstrapping and Confidence Estimation:

- Generate a large number (e.g., 1000) of bootstrap samples by resampling the original BOLD time series with replacement.

- Run the deconvolution algorithm on each bootstrap sample to generate a distribution of encoding estimates for each time point.

- Compute the confidence interval for each encoding value from this distribution.

Classification of Neural Events:

- Pre-classify neural event estimates into "known" (high-confidence) or "unknown" (low-confidence) based on the width of the bootstrap confidence interval. A threshold parameter,

δ, defines the confidence range [28]. - Discard events classified as "unknown" from subsequent analysis.

- Pre-classify neural event estimates into "known" (high-confidence) or "unknown" (low-confidence) based on the width of the bootstrap confidence interval. A threshold parameter,

Functional Connectivity Analysis:

- Calculate inter-regional correlations using only the time points with high-confidence neural event estimates.

- Compare the resulting functional connectivity networks (e.g., the default mode network) with those obtained from standard BOLD signal correlation. Studies show this approach yields higher sensitivity and specificity [28].

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Models for fMRI Deconvolution

| Item / Resource | Type | Function / Application | Representative Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canonical HRF (Double Gamma) | Mathematical Model | Serves as a constrained prior for the hemodynamic response in semi-blind deconvolution. | [28] [32] |

| Balloon-Windkessel Model | Biophysiological Model | Generates simulated BOLD signals from neuronal activity for algorithm validation. | [11] |

| Stability Selection | Statistical Method | Robustifies estimation against regularization parameter choice; provides probability maps of neural events. | [30] |

| Bootstrap Resampling | Statistical Method | Estimates confidence intervals for deconvolved neural events, enabling high-confidence analysis. | [28] |

deconvolve Python Toolbox |

Software Toolbox | Provides guidance on optimal design parameters for deconvolution in non-randomized designs. | [8] |

splora Python Package |

Software Toolbox | Implements multivariate deconvolution algorithms like Mv-SPFM. | [30] |

| Wilson-Cowan Neural Mass Model | Computational Model | Simulates realistic, oscillatory neuronal population dynamics for ground-truth simulation studies. | [11] |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Logical Workflow for Algorithm Selection

The following diagram outlines the decision process for choosing between fully-blind and semi-blind deconvolution approaches based on the research context and data availability.

Signaling Pathway from Neural Activity to Deconvolved Estimate

This diagram illustrates the conceptual pathway and the points of intervention for different deconvolution methods within the process of generating and analyzing the BOLD signal.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) based on the blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal has revolutionized cognitive neuroscience research, yet a fundamental challenge persists: the BOLD signal is an indirect, delayed, and confounded measure of underlying neural activity. The core problem stems from the sluggish hemodynamic response function (HRF) and the presence of multiple noise sources, including cardiac and respiratory signals, thermal effects, scanner drift, and motion-induced signal changes [33] [10]. This multidetermined nature of the BOLD signal complicates specific inferences about neural processes, particularly in complex experimental paradigms such as non-randomized alternating designs common in cognitive neuroscience [8] [1].

Deconvolution algorithms have emerged as crucial computational frameworks for addressing these challenges by estimating the underlying neural events from observed BOLD signals. These algorithms effectively invert the convolution process imposed by the HRF, enabling researchers to work with cleaner representations of neural activity. Among the various approaches developed, the Bu13 algorithm and Information-Assisted Dictionary Learning (IADL) represent significant advances with distinct methodological foundations and applications [10] [34] [35].

This survey provides a comprehensive technical analysis of these core algorithm frameworks, their performance characteristics, and practical implementation protocols. By situating this analysis within the context of optimizing fMRI BOLD deconvolution for non-randomized designs, we aim to equip researchers with the knowledge needed to select and apply appropriate algorithms for their specific experimental requirements.

Theoretical Foundations of BOLD Signal Deconvolution

The Hemodynamic Response Function and Its Implications

The BOLD signal measured in fMRI studies results from a complex interplay of neurovascular coupling processes. When neural activity occurs, it triggers a cascade of hemodynamic events including changes in cerebral blood flow, blood volume, and oxygen metabolism. This results in the characteristic HRF shape: a delayed rise peaking at approximately 4-6 seconds post-stimulus, followed by a slow return to baseline often accompanied by a post-stimulus undershoot [36]. The canonical model of the HRF typically resembles a gamma function, but substantial variation exists across brain regions and individuals [10] [16].

A critical challenge in fMRI analysis arises from the temporal overlap of BOLD responses to closely spaced neural events. This overlap is particularly problematic in non-randomized alternating designs, such as cue-target paradigms where events follow a fixed, predetermined sequence [1]. In such designs, the standard approach of jittering stimulus onsets or randomizing event sequences may not be feasible, necessitating robust analytical approaches that can separate overlapping hemodynamic responses.

Mathematical Formulation of the Deconvolution Problem

The fundamental mathematical model relating neural events to observed BOLD signals can be expressed as:

Y = X * h + ε

Where Y is the observed BOLD signal, X represents the underlying neural events, h is the HRF, * denotes the convolution operation, and ε encompasses various noise sources [33] [10]. Deconvolution aims to solve the inverse problem: estimating X given Y and an estimate of h.

The problem is ill-posed due to the presence of noise and the fact that the HRF acts as a low-pass filter, meaning that high-frequency information about neural events is attenuated in the BOLD signal. Regularization approaches are therefore necessary to constrain the solution space and produce physiologically plausible estimates of neural activity [10] [16].

Core Algorithm Frameworks

Bu13 Algorithm: Semi-Blind Deconvolution with Probabilistic Encoding

The Bu13 algorithm, introduced by Bush et al. [10], represents a significant advancement in semi-blind deconvolution approaches that require no knowledge of stimulus timings. This algorithm models neural events as a binary-valued sequence (termed the "encoding") and treats them as observable, intermediate probabilistic representations of the system's state.

Core Architecture and Mathematical Formulation

The Bu13 algorithm models the measured BOLD signal, y, as a vector ỹ of length T, given by:

ỹ = z(Fh)

where F is a feature matrix of size T × K, h is the HRF kernel column-vector of length K, and z(·) is a normalization mapping [16]. The feature matrix F is a modified Toeplitz matrix structured as:

F(i,k) = {ẽ(i-k) for i-k > -K, 0 otherwise}

where ẽ is the encoding vector of length M + (K-1) with each element ẽ(t) ∈ (0,1) representing the magnitude of neural activity [16].

To achieve the desired range of ẽ(t), the algorithm assumes neural events are driven by an unobserved time-series of real-valued neural activations, a(t) ∈ ℝ, which are temporally independent and determine the neural event encoding via the logistic function:

ẽ(t) = 1 / (1 + exp(-β · a(t)))

where β = 1 in the canonical implementation [16]. Deconvolution proceeds by optimizing neural activations a to minimize the cost function:

J = ½(ỹ(1:M) - y)²

Enhancements and Variants