Optimizing EEG Montages: Strategies to Reduce Setup Time and Enhance Data Quality for Clinical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing optimal EEG electrode montages to significantly reduce setup time without compromising data quality.

Optimizing EEG Montages: Strategies to Reduce Setup Time and Enhance Data Quality for Clinical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing optimal EEG electrode montages to significantly reduce setup time without compromising data quality. It explores the foundational principles of electrode reduction, systematic methodologies for identifying key electrode subsets, and practical troubleshooting for real-world application. By synthesizing recent evidence from meta-analyses and validation studies, the content offers actionable strategies for deploying efficient EEG protocols in clinical trials and research settings, facilitating faster participant throughput and improved practicality while maintaining scientific rigor.

The Science and Necessity of EEG Montage Optimization

The Critical Burden of Traditional EEG Setup in Research

Traditional electroencephalography (EEG) setups present a significant bottleneck in neuroscience research, creating a critical burden through lengthy application times, technical complexity, and limited practicality for real-world applications. These challenges are particularly pronounced in studies requiring rapid prototyping, longitudinal monitoring, or diverse participant populations. The operational costs of maintaining traditional EEG infrastructure are substantial, with labor accounting for up to 98% of expenditures in dedicated 24-hour services [1]. Furthermore, patient discomfort and restricted mobility during monitoring compromise data quality and ecological validity [1].

Fortunately, emerging research on optimal electrode montages is paving the way for radical efficiency improvements. Systematic electrode reduction studies demonstrate that researchers can reduce channel counts by 50% or more without significant performance degradation in various applications [2]. This technical support center provides actionable methodologies and troubleshooting guides to help researchers implement these advances, reduce setup time, and maintain data quality through optimized experimental protocols.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How many electrodes can I safely eliminate from my EEG setup without compromising data integrity? The optimal number varies by application, but systematic reductions of 50-75% are often achievable. For neonatal sleep state classification, research shows that a single properly selected channel (C3) can achieve 80.75% accuracy compared to multi-channel setups [3] [4]. In speech imagery brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), 64 channels can be reduced by 50% without significant performance loss [2]. The key is methodical validation rather than arbitrary reduction.

Q2: Are there standardized "optimal" electrode positions for specific research applications? While certain regions show consistent importance (e.g., left hemisphere electrodes for neonatal sleep classification), optimal configurations are often subject-specific [2]. Research indicates that relevant areas are distributed across the cortex rather than limited to classically defined functional regions [2]. Population-based optimization approaches can approximate individualized optimization, but perfect consistency across datasets remains elusive [5].

Q3: What is the most effective method for selecting which electrodes to keep in a reduced montage? Wrapper methods systematically evaluate channel subsets based on classification accuracy and are recommended over filter or embedded methods due to superior performance [2]. These methods work by iteratively excluding electrodes while monitoring performance metrics, providing a data-driven approach to montage optimization [2].

Q4: How can I troubleshoot persistent reference/ground electrode issues during setup? Reference electrode problems often manifest as uniformly poor signal quality across channels. Troubleshooting should include: reapplying the ground electrode with proper skin preparation; testing alternative ground placements (hand, sternum); removing all metal accessories; and swapping reference and ground electrode placements [6]. If issues persist, systematically check each component in the signal chain from software to participant [6].

Common Technical Issues & Solutions

| Symptom | Potential Reasons | Troubleshooting Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Missing Channels [7] | Dry electrodes, loose connections, incorrect amplifier settings | Check electrode-skin impedance; verify all physical connections; ensure amplifiers aren't set to same channel [8] [7] |

| Noisy/Poor Recordings [7] | Poor ground, artifact contamination, equipment malfunction | Verify ground connection; use targeted artifact cleaning [9]; check for nearby electronic devices; restart amplifier/software [6] |

| Spotty/Intermittent Signal [7] | Drying electrolyte, unstable electrode contact, equipment issues | Reapply electrodes with fresh conductive paste; check electrode integrity; swap headbox if issue persists [6] [7] |

| Global Signal Quality Issues | Ground loop interference, reference oversaturation [6] | Use AC-coupled ground adapter [8]; test with ground placed further from reference; ensure single ground point [8] [6] |

Experimental Protocols for Electrode Optimization

Systematic Electrode Reduction Methodology

The following workflow provides a standardized approach for determining the minimal electrode set required for your specific research application:

Protocol Details:

- Initial Setup: Begin with your standard high-density montage (e.g., 64-channel) collecting data for your specific task [2].

- Preprocessing: Apply standardized preprocessing including artifact removal techniques such as targeted artifact reduction in components to minimize false positive effects [9].

- Feature Extraction: Extract comprehensive linear and nonlinear features in time and frequency domains. Consider incorporating features like Detrended Fluctuation Analysis (DFA), Lyapunov exponent, and multiscale fluctuation entropy, which have shown utility in reduced-montage applications [3] [4].

- Classification & Evaluation: Establish baseline performance metrics using your standard analysis pipeline.

- Systematic Reduction: Implement wrapper methods to iteratively remove electrodes based on their contribution to classification accuracy [2].

- Validation: Cross-validate optimal montage on separate datasets and participants to ensure generalizability.

Population-Based Montage Optimization

For studies without resources for subject-specific optimization, population-based approaches provide a practical alternative:

Key Findings from Population Optimization Research:

- Population-based electric field optimization demonstrates comparable focality and targeting accuracy to individualized analysis, with differences up to 17% [5].

- Age mismatch between population proxy and target individual reduces focality by up to 8.3% compared to age-matched optimization [5].

- Populations larger than 40 individuals provide consistent optimization results with negligible inconsistencies [5].

Quantitative Performance Data of Reduced Montages

Electrode Reduction Performance Across Applications

| Research Application | Original Channels | Reduced Channels | Performance Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal Sleep Staging [3] [4] | Multiple | Single (C3) | Classification Accuracy | 80.75% ± 0.82% |

| Neonatal Sleep Staging [3] [4] | Multiple | 4 Left-Side Electrodes | Classification Accuracy | 82.71% ± 0.88% |

| Speech Imagery BCI [2] | 64 | 32 (50% reduction) | Classification Accuracy | No Significant Loss |

| Imagined Speech Detection [2] | 14 | 6-8 | Classification Accuracy | Up to 90% |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Dry Electrode EEG Systems [1] | Enables rapid application without skin preparation; ideal for reduced montage setups | Ultra-high impedance amplifiers (>47 GOhms); handles contact impedances up to 1-2 MOhms |

| Targeted Artifact Cleaning [9] | Addresses artifact contamination in reduced montages where fewer channels are available | RELAX pipeline (EEGLAB plugin); targets artifact periods/frequencies rather than subtracting entire components |

| Wrapper Method Algorithms [2] | Systematically identifies optimal electrode subsets based on performance metrics | Iteratively excludes electrodes while monitoring classification accuracy |

| SMOTE Technique [3] [4] | Addresses class imbalance in datasets when working with reduced signal information | Synthetic minority over-sampling technique; improves classifier performance with limited channels |

| PCA for Feature Selection [3] [4] | Reduces feature dimensionality to complement electrode reduction | Prioritizes most significant features from time/frequency domain analysis |

Advanced Methodologies for Specific Research Domains

Domain-Specific Electrode Optimization Protocols

Neonatal Sleep State Classification Protocol:

- Collect EEG data from multiple channels including bilateral coverage.

- Extract 94 linear and nonlinear features in time and frequency domains.

- Apply SMOTE technique to address class imbalance.

- Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for feature prioritization.

- Test single-channel performance systematically across all electrodes.

- Validate findings showing left-side electrodes (particularly C3) provide superior accuracy (82.71%) compared to right-side electrodes (81.14%) [3] [4].

Speech Imagery BCI Optimization Protocol:

- Record EEG data from 64 electrodes during speech imagery tasks.

- Implement wrapper function with objectives of minimizing error rate and channel count.

- Use random forest classifier for channel subset evaluation.

- Identify subject-specific optimal configurations rather than assuming universal positions.

- Validate that relevant areas are distributed across cortex, not limited to left hemisphere [2].

Remote Troubleshooting Framework

For research teams managing multiple testing sites or remote data collection, systematic troubleshooting is essential:

Remote Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Electrode/Cap Connections: Verify proper connections; re-clean/re-apply electrodes; add conductive gel; swap questionable electrodes [6] [10].

- Software/Computer/Amplifier: Restart recording software; reboot computer and amplifier; verify cable connections [6].

- Headbox & Cables: Swap headbox if available; test different electrode connections; verify physical integrity of all cables [6].

- Participant-Specific Factors: Remove metal accessories; check for hairstyle/products interfering; test alternative ground placements; evaluate for potential oversaturation [6].

- Documentation: Record the issue and solution for team knowledge sharing and future troubleshooting efficiency [10].

By implementing these methodologies and troubleshooting approaches, researchers can significantly reduce the critical burden of traditional EEG setups while maintaining data quality and expanding research capabilities through optimized electrode montages.

Core Concepts: Standardized Systems and Montages

What is the International 10-20 System and why is it fundamental to EEG research?

The International 10-20 System is a standardized method for placing scalp electrodes to ensure consistent and replicable EEG recordings across different subjects and sessions. Developed by Herbert Jasper in 1957, it is based on the relationship between electrode location and the underlying cerebral cortex [11] [12]. The system's name comes from the fact that distances between adjacent electrodes are either 10% or 20% of the total front-to-back or right-to-left distance of the skull. Key anatomical landmarks used for measurement are the nasion (the depressed area between the eyes, just above the bridge of the nose), the inion (the crest point at the back of the skull), and the preauricular points (in front of each ear) [11].

Electrode Nomenclature:

- Letters indicate the brain region or lobe the electrode covers: Fp (pre-frontal or frontal pole), F (frontal), C (central), T (temporal), P (parietal), and O (occipital) [11] [12].

- Numbers indicate the distance from the midline. Even numbers are on the right hemisphere, odd numbers are on the left, and the 'z' (for zero) denotes electrodes placed on the midline sagittal plane (e.g., Fz, Cz, Pz) [11] [12].

What is an EEG montage and how does a differential amplifier work?

An EEG montage is a combination of derivations, which are specific pairs of electrodes assigned to an amplifier's inputs [13]. The core technology behind interpreting these derivations is the differential amplifier.

A differential amplifier takes two input signals (Input 1 and Input 2, often labeled active and reference) and amplifies the difference in voltage between them, while suppressing any voltage that is common to both. This process is called Common Mode Rejection (CMR) [13]. It is crucial for eliminating pervasive environmental artifacts, such as 50/60 Hz electrical mains interference, which are present equally in both inputs and are therefore subtracted out. This allows the "real" EEG activity, which typically has different voltages at the two electrode sites, to be visible [13].

What are the common types of EEG montages?

- Referential Montage: Each active electrode on the scalp is compared to a single, theoretically "neutral" reference electrode (e.g., on the ear or mastoid) [13].

- Bipolar Montage: A "daisy-chain" configuration where electrodes are linked in sequence (e.g., Fp1-F3, F3-C3, C3-P3). This is effective for localizing transient events like epileptiform activity [14].

What are the extended systems beyond the 10-20 system?

To achieve higher spatial resolution, extended systems like the 10-10 system (10% division) and the 10-5 system (5% division) were developed. These fill in intermediate sites between the original 10-20 electrodes, allowing for high-density EEG recordings with 64, 128, or more channels [11] [12]. The Modified Combinatorial Nomenclature (MCN) was introduced to name these new electrode sites using letter combinations like AF (between Fp and F), FC (between F and C), and CP (between C and P) [11].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section addresses common practical challenges in EEG research.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My EEG signal is noisy with 50/60 Hz "fuzzy" waves. What should I check? This is typically 50/60 Hz mains artifact. The differential amplifier's Common Mode Rejection is designed to eliminate this. If it persists, check:

- Electrode Impedance: Ensure all electrodes, including ground and reference, have low and stable impedance (typically < 5-10 kΩ). High impedance unbalances the amplifier and reduces CMR effectiveness [6] [14].

- Ground Connection: Verify the ground electrode is properly applied. A faulty ground can cause this artifact across all channels [6] [13].

- Cable Integrity: Check for damaged or loose cables that could break the signal balance [6].

Q2: One of my electrode impedance readings is persistently high (greyed out). How can I resolve this?

- Re-prep the site: Clean the scalp area again and re-apply conductive paste or gel to ensure good skin contact [6].

- Swap the electrode: Replace the problematic electrode with a new one to rule out a "dead" or faulty sensor [6].

- Check for bridging: Inspect if excess gel has created an electrical bridge between two adjacent electrodes, which can cause abnormal readings [6].

- Inspect the hardware: If the issue persists, check the cap connection and, as a last resort, try a different headbox or amplifier input to isolate a hardware fault [6].

Q3: How critical is precise electrode placement? What is the impact of a small misplacement? For most standard EEG analyses (e.g., spectral power, event-related potentials), minor placement errors have a relatively small impact. A simulation study using a realistic head model found that electrode displacements with a mean of 5 mm introduced a source localization error of only about 2 mm for normal, noisy EEG signals [15] [16]. This error is generally negligible compared to those caused by biological and environmental noise. However, for advanced applications like precise dipole source localization or TMS-EEG co-registration, highly accurate placement (aided by digitization) is recommended [15] [17].

Q4: For my study on neonatal sleep, which electrode montage would provide optimal results with minimal setup time? Research on neonatal sleep state classification suggests that a limited, optimized montage can be highly effective. A 2025 study found that a single C3 channel (left central) achieved an accuracy of 80.75% using an LSTM classifier. Furthermore, a configuration using four left-side electrodes (C3, F3, etc.) achieved a higher accuracy of 82.71% compared to four right-side electrodes (81.14%) [18]. This indicates that a minimal montage focused on the left hemisphere can reduce technical complexity and setup time while maintaining high performance for this specific application.

Systematic Troubleshooting Flowchart

Follow this logical pathway to diagnose common EEG hardware issues.

Experimental Protocols & Data

This section provides a summary of key experimental methodologies and quantitative findings from recent literature.

Experimental Protocol: Neonatal Sleep State Classification with Optimized Montage

Objective: To classify neonatal sleep states using an LSTM classifier and identify an optimal electrode setup to reduce complexity [18].

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: EEG data was collected from 64 infants (36-43 weeks age) at Fudan University Children's Hospital. A total of 16,803 30-second EEG segments were used [18].

- Feature Extraction: A comprehensive set of 94 linear and nonlinear features in time and frequency domains were extracted, including novel features like Detrended Fluctuation Analysis (DFA), Lyapunov exponent, and multiscale fluctuation entropy [18].

- Data Balancing: The SMOTE technique was used to address class imbalance [18].

- Feature Reduction: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied to identify and prioritize the most significant features [18].

- Classification & Electrode Optimization: An LSTM classifier was trained and tested using different electrode configurations (single channel, four left-side, four right-side) to compare performance [18].

Key Performance Data (Classification Accuracy):

| Electrode Configuration | Accuracy (%) | Kappa Value |

|---|---|---|

| Single C3 Channel | 80.75% ± 0.82 | 0.76 |

| Four Left-Side Electrodes | 82.71% ± 0.88 | 0.78 |

| Four Right-Side Electrodes | 81.14% ± 0.77 | 0.76 |

Source: Siddiqa et al., 2025, Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience [18].

Experimental Protocol: RBF Neural Network for EEG Dynamics Reconstruction

Objective: To reconstruct EEG dynamics and extract age-related neural characteristics using a Radial Basis Function (RBF) neural network optimized by Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [14].

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Resting-state EEG was recorded from 142 participants across multiple age groups using a 32-channel system following the 10-20 system [14].

- Preprocessing: Signals were bandpass filtered (1–35 Hz) and artifacts were removed using Independent Component Analysis (ICA). A longitudinal bipolar montage (e.g., Fp1-F3, F3-C3, C3-P3, P3-O1) was used for analysis [14].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was applied to reduce the 18-dimensional EEG signals to three-dimensional sequences [14].

- Model Training & Optimization: An RBF neural network was trained on the EEG time-series data, with Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) used to optimize model parameters and identify fixed points in the reconstructed neural system [14].

Key Performance Data (Model Accuracy):

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Normalized Root Mean Square Error (NRMSE) | 0.0671 ± 0.0074 |

| Pearson Correlation Coefficient | 0.892 ± 0.0678 |

Source: Front. Neurosci., 2025 [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Materials

A selection of key reagents, materials, and software used in modern EEG experiments.

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| SMOTE Technique | A data preprocessing technique used to solve class imbalance in datasets, crucial for building unbiased classifiers in tasks like sleep stage classification [18]. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | A statistical procedure for feature reduction; used to identify and prioritize the most significant features from a large set of extracted EEG features [18] [14]. |

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) | A computational method for separating multivariate signals into additive subcomponents, widely used for artifact removal (e.g., eye blinks, muscle activity) from EEG data [14]. |

| LSTM Network | A type of recurrent neural network (RNN) well-suited for classifying and predicting time-series data, such as EEG sequences for sleep staging or seizure detection [18]. |

| RBF Neural Network | A type of artificial neural network that uses radial basis functions as activation functions. Useful for reconstructing EEG dynamics and modeling non-linear systems [14]. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | A computational method for optimizing a problem by iteratively trying to improve a candidate solution. Used to optimize parameters of neural network models for EEG analysis [14]. |

| Sintered Ag/AgCl Electrodes | Electrodes made from sintered silver/silver-chloride, providing a low noise floor, stable half-cell potential, and resistance to polarization, ideal for high-fidelity recordings [17]. |

| Ultra-Flat (3 mm) Electrodes | Specially designed, low-profile electrodes that minimize the distance between the TMS coil and scalp, reducing artifacts and improving stimulation precision in combined TMS-EEG studies [17]. |

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a foundational tool in neuroscience and clinical research. However, a significant practical challenge persists: the trade-off between data richness and the time-consuming, complex setup of multi-electrode systems. This is especially critical in applications involving vulnerable populations, such as neonates, or in the development of wearable brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). This article examines the evidence for optimizing electrode count, providing technical support for researchers aiming to reduce setup time while preserving data integrity.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core trade-off between the number of electrodes and setup time? The primary trade-off lies between data comprehensiveness and practical feasibility. Multi-channel EEG systems (e.g., 32+ electrodes) provide high spatial resolution and detailed brain mapping but require lengthy setup times of 30 minutes or more. This can cause participant discomfort and reluctance, particularly in clinical or repeated-measurement settings [19]. Minimal-channel systems significantly reduce setup time and improve user comfort but require careful electrode placement to ensure the collected data is sufficient for the specific research or clinical question.

Q2: Can a single EEG channel provide reliable data for classification tasks? Yes, for specific, well-defined tasks. Research on neonatal sleep state classification demonstrated that a single channel (C3) could achieve an accuracy of 80.75% ± 0.82% in classifying five sleep stages [3]. This indicates that for certain applications, a single, optimally placed electrode can capture sufficient information, dramatically reducing technical complexity and the risk of skin irritation.

Q3: Where should minimal electrodes be placed for motor imagery tasks? For motor imagery (MI) tasks, such as imagining hand movements, the sensorimotor cortex is key. One study identified that a configuration of nine electrodes over the central scalp regions (F3, Fz, F4, C3, Cz, C4, P3, Pz, and P4) provided high classification accuracy with a moderate setup time, representing a minimal setup for a successful BCI application [19].

Q4: What is the "end of chain" phenomenon in bipolar montages? In bipolar montages, where electrodes are linked in a chain, the first and last electrodes in each chain lack a second point of comparison. This "end of chain" phenomenon means you only see half of any potential phase reversals at these electrodes (like Fp1, Fp2, O1, O2), which can hinder the localization of electrical activity. This can be mitigated by using alternative montages, such as a circumferential montage [20].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common EEG Setup Issues

Problem: Persistent high impedance or abnormal signal in one or multiple channels.

| Troubleshooting Step | Actions & Checks |

|---|---|

| 1. Check Electrode Connections | Ensure all electrodes are plugged in correctly. Re-clean and re-apply the problematic electrode(s) with appropriate conductive paste or gel. Swap the suspect electrode with a known good one to rule out a "dead" electrode [6]. |

| 2. Inspect Ground/Reference | The ground (GND) electrode can affect all channels. Reapply the GND, ensuring proper skin preparation. Try alternative GND placements (e.g., hand, sternum) to isolate the issue [6]. |

| 3. Verify Hardware Function | Restart the acquisition software, computer, and amplifier. If possible, test the setup with a different headbox or on a different acquisition system in another room to rule out hardware failure [6]. |

| 4. Check for Participant Factors | Ask the participant to remove all metal accessories. Consider if hairstyle, skin products, or unique skin properties (e.g., static electricity, moisture levels) might be causing bridging or signal oversaturation [6]. |

The logical workflow for systematic troubleshooting is outlined below:

Recent studies provide quantitative evidence for optimizing electrode count across different applications. The following table summarizes key findings from the literature.

Table 1: Evidence for Electrode Number Optimization in Different Applications

| Application | Optimal Electrode Configuration | Performance Metrics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal Sleep Staging [3] | Single channel: C3 | Accuracy: 80.75% ± 0.82%Kappa: 0.76 | A single, optimally placed electrode can provide high classification accuracy for sleep states, reducing setup complexity. |

| Neonatal Sleep Staging [3] | Multi-channel: Four left-side electrodes (F3, C3, T3, P3) | Accuracy: 82.71% ± 0.88%Kappa: 0.78 | A small, asymmetric cluster can outperform both single-channel and other multi-channel configurations (e.g., four right-side electrodes: 81.14% accuracy). |

| Hand Motor Imagery (BCI) [19] | 9 electrodes (F3, Fz, F4, C3, Cz, C4, P3, Pz, P4) | High classification accuracy | This configuration was selected as the minimal channel setup that provided high accuracy with a moderate, user-friendly setup time. |

The process of determining the minimal number of electrodes for a wearable BCI, as investigated in one study, involves a structured experimental and analytical workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Components for EEG-Based BCI Research

| Item / Technique | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| International 10-20 System | Standardized method for electrode placement on the scalp, ensuring consistency and reproducibility across studies [20] [21]. |

| Differential Amplifier | Amplifies the voltage difference between two electrodes, effectively cancelling out common noise (common mode rejection) to improve the signal-to-noise ratio [21]. |

| Filter Bank Feature Extraction | A signal processing technique that decomposes the EEG signal into multiple frequency bands, which is particularly useful for detecting event-related desynchronization/synchronization (ERD/ERS) in motor imagery tasks [19]. |

| Common Spatial Pattern (CSP) | A spatial filtering algorithm used to optimize the discrimination between two classes of EEG signals (e.g., left vs. right hand motor imagery) [19]. |

| SMOTE Technique | Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique. Used to address class imbalance in datasets by generating synthetic samples of the underrepresented classes, improving classifier performance [3]. |

| Spherical Spline Interpolation (SSI) | A mathematical method to estimate the signal of a faulty or missing electrode based on the signals from surrounding electrodes. Note: One study found it may not improve classification accuracy for minimal channels [19]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: How many electrodes can I realistically remove from a standard 64-channel system without significantly hurting my classification accuracy?

A systematic evaluation of electrode reduction for Speech Imagery Brain-Computer Interfaces (SI-BCIs) found that the original 64 channels could be reduced by 50% without a significant loss in classification accuracy [2]. This indicates that for many applications, a 32-channel setup may be sufficient, striking a balance between performance and practicality.

However, the optimal configuration is highly subject-specific. The same study could not identify a single, consistent set of optimal electrode positions across different datasets and individuals [2]. Therefore, while a 50% reduction is a good rule of thumb, the best approach is to individually tailor the electrode configuration for each user or research population.

FAQ 2: Are there specific brain regions where electrode placement is more critical for accurate classification?

The importance of electrode placement is task-dependent, and contrary to common assumptions, critical areas may not be limited to the classic brain regions associated with a task.

- For Neonatal Sleep Staging: Research suggests a hemispheric bias. One study found that classification accuracy for four left-side electrodes was higher (82.71% ± 0.88%) than for four right-side electrodes (81.14% ± 0.77%) [3]. Furthermore, a single C3 channel (over the left central cortex) achieved an accuracy of 80.75% ± 0.82%, which was superior to other single channels tested [3].

- For Speech Imagery (SI-BCIs): Relevant areas were not limited to the left hemisphere (traditionally responsible for speech) but were distributed across the cortex [2]. This suggests that a broad coverage, rather than a focused placement on classic language areas, might be necessary for optimal decoding of imagined speech.

FAQ 3: My classification performance drops when the EEG cap is repositioned or used on a new subject. How can I mitigate this electrode shift problem?

Electrode placement variability is a recognized challenge that reduces classification robustness. A recent solution is the Adaptive Channel Mixing Layer (ACML), a plug-and-play preprocessing module for deep learning models [22].

- How it works: The ACML applies a learnable transformation matrix to the input EEG signals, dynamically re-weighting channels based on their inter-correlations. This helps compensate for spatial misalignments caused by cap repositioning or anatomical differences between subjects [22].

- Performance: Experimental validation showed that integrating ACML improved classification accuracy (up to 1.4%) and kappa scores (up to 0.018) across subjects, enhancing resilience to electrode shifts [22].

FAQ 4: Does rigorous preprocessing for artifact removal always lead to better decoding performance?

Not necessarily. A systematic multiverse analysis of preprocessing choices revealed a counterintuitive finding: artifact correction steps often decrease decoding performance [23].

- Reason: Artifacts (like eye movements or muscle activity) can be systematically associated with the task or condition being decoded. For example, in a visual attention task (N2pc), eye movements are predictive of the target location. Removing these "artifacts" also removes the predictive signal, hurting performance [23].

- Recommendation: While removing artifacts is crucial for the interpretability of neural signals and model validity, researchers focused purely on maximizing decoding accuracy should carefully evaluate the impact of each artifact correction step. The study also found that using a higher high-pass filter cutoff consistently increased decoding performance [23].

FAQ 5: Can I use a population-optimized electrode montage instead of creating individualized setups for every subject?

Yes, population-optimized approaches are a viable and practical strategy. Research in transcranial temporal interference stimulation (tTIS) has demonstrated that montages optimized using group-level electric field analysis can achieve targeting effects comparable to individualized optimization, with a difference of up to 17% in focality [5].

- Key Factor - Population Size: The accuracy of this approach depends on the size of the representative population. Insufficient population size leads to inconsistencies, but these are negligible for populations larger than 40 individuals [5].

- Key Factor - Age Matching: Age mismatch between the population proxy and the target individual can reduce focality by up to 8.3%, so using an age-matched population proxy is recommended [5].

This approach eliminates the need for individual MRI scans, significantly enhancing the accessibility and practicality of optimized montages [5].

Performance Metrics for Electrode Montages

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Different Electrode Setups

| Application | Optimal Setup | Performance Metrics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal Sleep Staging [3] | Single C3 channel | Accuracy: 80.75% ± 0.82%Kappa: 0.76 | Single-channel performance can be high, reducing system complexity. |

| Four left-side electrodes | Accuracy: 82.71% ± 0.88%Kappa: 0.78 | Left-side electrodes showed a slight performance advantage over right-side. | |

| Speech Imagery BCI [2] | 50% reduced montage (32 channels) | No significant performance loss vs. 64-channel setup. | A 32-channel setup balances accuracy and practicality for SI-BCIs. |

| Motor Imagery BCI [22] | Standard setup + ACML | Accuracy: +1.4% improvementKappa: +0.018 improvement | The ACML module robustly improves performance against electrode shift. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Systematic Electrode Reduction for SI-BCIs [2]

- Data Acquisition: Collect EEG data from multiple subjects (e.g., 15+) using a 64-electrode system (10-20 placement).

- Preprocessing: Filter data to remove artifacts and limit the frequency spectrum to the relevant band.

- Feature Extraction & Classification: Apply standard feature extraction (e.g., band power) and classification (e.g., Random Forest) methods.

- Iterative Electrode Reduction: Use a wrapper method algorithm to systematically exclude electrodes one-by-one based on their impact on classification accuracy. The cycle of feature extraction and classification is repeated with the remaining electrodes until only one channel remains.

- Analysis: Identify the point at which classification performance begins to drop significantly and analyze the spatial distribution of the most relevant electrodes.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Population vs. Individual Montage Optimization [5]

- Head Model Creation: Develop personalized computational head models from structural MRIs of a large cohort (>40 individuals).

- Lead-Field Calculation: For each model, calculate the electric field (E-field) distribution for a range of possible electrode montages.

- Optimization:

- Individualized: Optimize the montage for each subject to maximize E-field intensity/focality in a target brain region.

- Population-based: Use a group-level algorithm to find a single montage that optimizes the E-field across the entire population cohort.

- Validation: Use leave-one-out cross-validation to compare the targeting accuracy (focality and intensity) of the population-optimized montage against the individualized montages.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for EEG Montage Optimization Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density EEG System | Provides the initial, high-resolution brain activity data required for systematic electrode reduction studies. | 64-channel systems with Brain Products LiveAmp hardware are commonly used [2]. |

| Dry Electrode Headsets | Enable practical, long-term monitoring with faster setup times, facilitating real-world data collection. | QUASAR sensors with ultra-high impedance amplifiers allow recording through hair without gel [1]. |

| Computational Head Models | Allow for in-silico testing and optimization of electrode montages without requiring physical experiments on subjects. | Created from structural MRIs using software like SimNibs [5] [24]. |

| Adaptive Preprocessing Algorithms | Mitigate performance degradation caused by real-world variability like electrode shift between sessions. | The Adaptive Channel Mixing Layer (ACML) is a plug-and-play deep learning module [22]. |

| Artifact Removal Tools | Clean non-neural noise from EEG data, though their use requires careful evaluation regarding decoding goals. | RELAX EEGLAB plugin; Independent Component Analysis (ICA) [9] [23]. |

Workflow for Electrode Montage Optimization

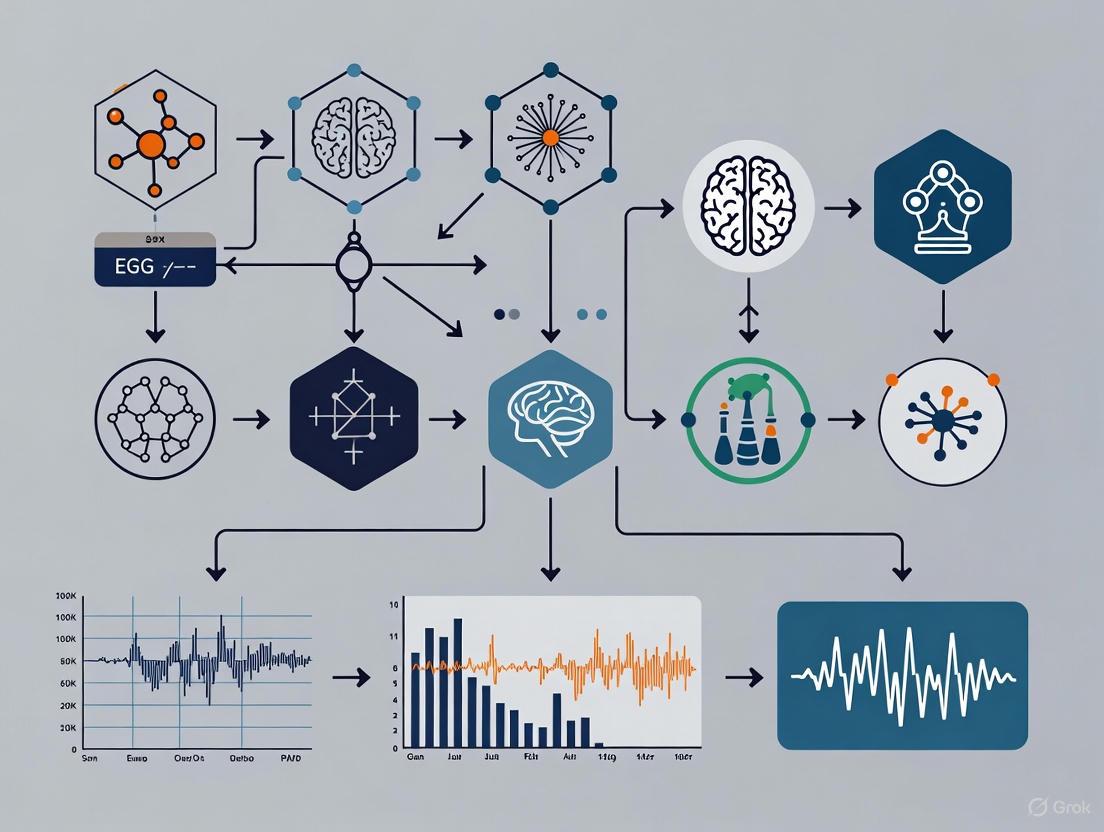

The diagram below outlines a systematic workflow for optimizing an electrode montage, integrating insights from the cited research.

Systematic Approaches for Identifying Optimal Electrode Subsets

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why should I use a Genetic Algorithm for EEG electrode selection instead of a simple filter method?

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) are a powerful choice for this optimization problem because they perform a global search and are less prone to getting stuck in local minima compared to simpler methods [25]. For EEG electrode selection, you are searching for the best combination of electrodes from a very large set of possibilities; GAs efficiently evolve a population of potential solutions (electrode subsets) over generations to find a high-performing, near-optimal configuration [26]. Unlike filter methods that rank electrodes individually, GAs can capture the complex interactions between different electrode sites, leading to a subset that works well collectively for your specific task, such as source localization or signal classification [27] [28].

FAQ 2: My wrapper method is taking too long to run. What can I do to reduce computation time?

The computational expense of wrapper methods is a common challenge [27] [28]. You can address this with several strategies:

- Pre-filtering: Use a fast filter method (e.g., based on mutual information or variance) to remove clearly irrelevant electrodes before applying the more computationally intensive wrapper method [27].

- Set a Feature Limit: Define a maximum number of features (electrodes) to select, which significantly shortens the search process in forward selection or recursive elimination [28].

- Use Cross-Validation Wisely: While cross-validation is essential to prevent overfitting, using a lower number of folds (e.g., 5-fold instead of 10-fold) can speed up the evaluation process [27].

- Leverage Hybrid Algorithms: For GAs, use techniques like "dominant block" mining or association rules to reduce problem complexity and increase solving speed [29].

FAQ 3: I've found an optimal electrode set in my offline analysis. How do I validate it for real-world use?

An optimal electrode set identified through offline analysis must be validated prospectively in an online experiment to confirm its viability [30]. This involves:

- Prospective Testing: Recruit a new cohort of subjects and conduct online sessions using only the reduced electrode configuration [30].

- Performance Comparison: Compare key performance metrics (e.g., classification accuracy, information transfer rate, source localization error) between the reduced set and the full, high-density electrode set [30] [2].

- Statistical Analysis: Perform statistical tests to confirm that there is no significant difference in performance between the full and reduced configurations. A successful validation shows that the reduced set does not degrade system performance while offering practical benefits [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Genetic Algorithm Converges Too Quickly to a Sub-Optimal Electrode Set

- Symptoms: The algorithm's performance plateaus early, and the resulting electrode subsets are inconsistent or perform poorly on new data.

- Causes: This is often caused by a loss of population diversity, leading to premature convergence [29].

- Solutions:

- Increase Mutation Rate: Slightly increase the probability of mutation to introduce new genetic material and explore new areas of the solution space [25].

- Implement Chaotic Search: Use an improved Tent map or other chaotic algorithms to enhance the quality and diversity of the initial population, preventing early convergence to local optima [29].

- Review Selection Pressure: Ensure your selection mechanism (e.g., tournament size) is not too strong, which can cause the population to be overrun by a few fit but sub-optimal individuals too early in the process.

Problem: Wrapper Method Leads to Overfitting

- Symptoms: The selected electrode subset performs exceptionally well on your training data but generalizes poorly to unseen test data or new subjects.

- Causes: The method has over-optimized for the specific nuances and noise in your training dataset [27] [28].

- Solutions:

- Strict Cross-Validation: Always use nested cross-validation for a more robust evaluation of the selected feature set. This means having an outer loop for estimating generalization performance and an inner loop for the feature selection process itself [27].

- Simplify the Model: Use a simpler classifier within the wrapper during the selection phase, or increase regularization parameters to make the model less prone to fitting noise.

- Combine with Filter Methods: As a pre-processing step, use a filter method to select a broader, relevant set of electrodes before applying the wrapper method, which reduces the chance of the wrapper finding spurious correlations in a vast search space [27].

Problem: Inconsistent Optimal Electrode Positions Across Subjects

- Symptoms: The algorithm identifies different "optimal" electrode subsets for each subject in your study, making it difficult to define a standard montage.

- Causes: This is a common and expected finding, as brain anatomy and functional topography vary between individuals [2].

- Solutions:

- Subject-Specific Configuration: Accept that optimal configurations are often subject-dependent. The methodology can be applied to find a personalized optimal set for each user, which is then used in all subsequent sessions [2].

- Population-Level Analysis: If a universal set is required, run the optimization algorithm on data from multiple subjects concurrently. Techniques like Gibbs sampling can be used to find a set of electrodes that provides good performance across the entire subject population, even if it is not the absolute best for any single individual [30].

Experimental Data and Protocols

Table 1: Performance of Optimized Low-Density EEG Electrode Sets

This table summarizes quantitative results from key studies that successfully employed algorithm-driven optimization to reduce electrode count.

| Study / Application | Full Montage (Number of Electrodes) | Optimized Montage (Number of Electrodes) | Key Performance Metric | Performance: Full vs. Optimized |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEG Source Localization [26] | 231 (HD-EEG) | 6 - 8 | Single-source localization error | Equal or better accuracy in >88% of cases (synthetic) and >63% of cases (real data) |

| P300 Speller [30] | 32 | 4 | Online classification accuracy | No significant difference in subject performance |

| Speech Imagery BCI [2] | 64 | 32 (50% reduction) | Classification accuracy | No significant performance loss |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Algorithm-Driven EEG Optimization

This table details essential computational tools and algorithms used in this field.

| Reagent / Solution | Type | Primary Function in Experiment | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-dominated Sorting GA II (NSGA-II) [26] | Multi-objective Genetic Algorithm | Finds optimal trade-off between minimizing electrode count and minimizing localization/classification error. | Automated selection of minimal electrode subsets for accurate EEG source estimation [26]. |

| Gibbs Sampling [30] | Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Method | Finds the optimal electrode configuration based on the joint probability of EEG data and known labels. | Optimizing EEG electrode number and placement for P300 speller systems across a subject population [30]. |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) [27] [2] | Wrapper Feature Selection Method | Recursively removes the least important electrodes (features) based on a model's weights or importance scores. | Systematic reduction of electrodes for Speech Imagery BCI; often used with linear models or SVMs [27] [2]. |

| Stepwise Linear Discriminant Analysis (SWLDA) [30] | Statistical Method / Wrapper | Automatically adds or removes features based on their statistical significance in classifying target vs. non-target stimuli. | A core component for feature selection and classification in P300 BCI systems [30]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: GA for Minimal Electrode Selection

The following workflow, based on the NSGA-II methodology, is used to find the minimal electrode subset for accurate EEG source localization [26]:

- Input Preparation: Gather the required inputs: the EEG/ERP signals, a validated head model for source reconstruction, and the ground-truth location of the source activity (if available).

- Population Initialization: Randomly generate an initial population of "chromosomes," where each chromosome is a binary vector representing a possible electrode subset (e.g., a value of '1' means the electrode is included).

- Fitness Calculation: For each chromosome (electrode subset) in the population:

- Reconstruct Sources: Solve the EEG inverse problem (e.g., using wMNE, sLORETA, or MSP) using only the selected electrodes.

- Calculate Localization Error: Compute the error between the estimated source location and the ground-truth location.

- Assign Fitness Scores: The two fitness scores for the multi-objective algorithm are: (1) the localization error (to be minimized), and (2) the number of selected electrodes (to be minimized).

- Evolutionary Loop: Create a new generation by applying:

- Selection: Preferentially select parent chromosomes with better (lower) fitness scores.

- Crossover: Combine pairs of parents to create "offspring" chromosomes, mixing their electrode subsets.

- Mutation: Randomly flip bits in the offspring chromosomes (add or remove electrodes) to maintain diversity.

- Termination and Output: Repeat the evolutionary loop until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., a fixed number of generations). The output is a set of non-dominated "Pareto-optimal" solutions, representing the best possible trade-offs between accuracy and electrode count.

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Diagrams

GA for Electrode Selection

Wrapper Method Logic

Population-Based vs. Subject-Specific Electrode Configurations

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the core difference between population-based and subject-specific electrode configurations? A population-based configuration is a single, fixed set of electrode locations determined to be optimal for a group of users or a specific task. In contrast, a subject-specific configuration is a unique set of electrodes tailored to an individual user, often identified through an initial calibration procedure using a full EEG cap [30] [2].

When should I use a population-based configuration? Population-based setups are ideal for:

- Rapid Deployment: Applications where speed and ease of setup are critical, and a slight reduction in performance is acceptable [30].

- Standardized Tasks: Well-established paradigms where neural signatures are consistently localized across individuals, such as the P300 speller, where a set of four posterior electrodes (PO7, PO8, POz, CPz) may suffice [30].

- Large-Scale Screening: Clinical trials or studies where minimizing setup time and technician burden is a primary concern [31].

When is a subject-specific configuration necessary? Subject-specific configurations are recommended for:

- Complex Cognitive Tasks: Paradigms like speech imagery, where relevant brain activity is distributed across the cortex and varies significantly between individuals [2].

- Maximizing Performance: Applications where achieving the highest possible classification accuracy or source localization precision is the main goal [26].

- Patient Populations: Scenarios involving users with specific neurological conditions or brain anatomy variations that may alter typical brain activation patterns [30].

Can I reduce the number of electrodes without losing significant data quality? Yes, multiple studies demonstrate that electrode counts can often be substantially reduced. Research on speech imagery BCIs showed that 64 channels could be reduced by 50% (to 32 channels) without a significant loss in classification accuracy [2]. Similarly, for certain EEG source localization tasks, optimal subsets as small as 6 to 8 electrodes can achieve accuracy equal to or better than high-density setups with over 200 channels [26].

Are there automated methods to find the optimal electrode set? Yes, several computational methods exist:

- Wrapper Methods: These algorithms (e.g., sequential backward elimination) systematically evaluate the performance of different electrode subsets by iteratively removing the least important channel and re-evaluating the classifier [2].

- Genetic Algorithms: Multi-objective optimization algorithms, like NSGA-II, can simultaneously minimize the number of electrodes and the localization error or maximize classification accuracy to find optimal configurations [26].

- Gibbs Sampling: A Markov chain Monte Carlo method that can be used to find the set of electrodes that optimizes the joint probability of the EEG data and known labels for a given population [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Classification Accuracy with a Population-Based Configuration

Problem: Your BCI system or neural biomarker analysis is performing poorly with a standard, fixed electrode montage.

Solution:

- Verify Signal Quality: First, confirm that the poor performance is not due to simple signal quality issues like high impedance or excessive noise from movement [32].

- Switch to a Subject-Specific Approach: For complex tasks like imagined speech, a universal configuration is often suboptimal. Implement a subject-specific channel selection protocol [2].

- Implement a Calibration Session:

- Record an initial session using a high-density EEG system (e.g., 64 electrodes).

- Use a wrapper method or genetic algorithm to identify the subset of electrodes that provides the best task classification accuracy for that specific individual.

- Use this personalized subset for all subsequent sessions [2] [26].

Issue 2: High Setup Time with a Full High-Density EEG System

Problem: The process of applying a full 64+ electrode cap is too time-consuming for your study protocol or clinical application.

Solution:

- Adopt a Pre-Defined Reduced Set: For standard tasks (e.g., P300), use a validated, population-based reduced set. For example, a 4-electrode setup (PO7, PO8, POz, CPz) has been shown to be effective for P300 spellers, drastically cutting setup time [30].

- Use Dry Electrode Systems: Consider using dry-electrode EEG headsets. Studies show they can reduce setup time by nearly 50% compared to standard wet EEG systems while maintaining adequate data quality for many applications like resting-state EEG and P300 measurements [31].

- Optimize for Your Population: If your study focuses on a specific population and task, use historical data to derive your own optimized, fixed montage, balancing channel count and performance for your specific needs [30] [26].

Issue 3: inconsistent or Noisy Signals from Specific Electrodes

Problem: Certain channels consistently show poor signal quality, complicating data analysis.

Solution:

- Systematic Troubleshooting: Follow a step-by-step approach to isolate the cause [6]:

- Check Electrodes/Cap: Ensure all connections are secure. Re-clean and re-apply problematic electrodes. Try swapping electrodes to rule out a "dead" sensor [6] [32].

- Check Software/Amplifier: Restart the acquisition software and amplifier. If possible, test the setup in a different room or with a different amplifier system to rule out hardware failure [6].

- Check the Headbox: Swap out the headbox to see if the issue persists [6].

- Check Participant-Specific Factors: Remove all metal accessories. Check for hair products or static that might cause "bridging" between electrodes. Try alternative ground electrode placements (e.g., hand, sternum) [6].

- Exclude and Compensate: If a hardware issue is ruled out and the signal cannot be cleaned, note that some electrode reduction algorithms are robust to the exclusion of a small number of noisy channels. Proceed with your analysis using the remaining good channels [2] [26].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Gibbs Sampling for Population-Based P300 Speller Configuration

This method finds an optimal electrode set for a group of users [30].

- Data Collection: Collect P300 speller data from a cohort of subjects (e.g., 15+) using a high-density system (e.g., 32 electrodes).

- Feature Extraction: For each stimulus, extract a feature vector from the 600ms of post-stimulus EEG data.

- Model Setup: Represent channel inclusion with a binary vector

c, wherec_j = 1if channeljis used. - Gibbs Sampling: Run a Gibbs sampling algorithm to explore the state space of possible electrode combinations. The algorithm iteratively selects and updates the state of each channel (

c_j) based on its probability given the states of all other channels (c_{-j}) and the known labels. - Validation: The resulting optimal set (e.g., 4 electrodes: PO7, PO8, POz, CPz) should be validated prospectively in a new group of subjects against the full electrode set to confirm non-inferior performance.

Protocol 2: Wrapper Method for Subject-Specific Configuration in Speech Imagery BCI

This protocol is ideal for tailoring a BCI to an individual user for a complex task [2].

- Full Cap Recording: Record EEG data (e.g., with a 64-electrode cap) while the participant performs the imagined speech task.

- Preprocessing: Apply standard preprocessing: bandpass filtering and artifact removal (e.g., using ICA).

- Initial Classification: Extract features (e.g., band power, Riemannian geometry features) and establish a baseline classification accuracy using a classifier (e.g., SVM, LDA) with all electrodes.

- Iterative Electrode Reduction:

- Use a wrapper method to rank the importance of each electrode.

- Remove the least important electrode.

- Retrain the classifier and re-evaluate the accuracy with the reduced set.

- Repeat this process until only one electrode remains.

- Select Optimal Subset: Plot classification accuracy against the number of electrodes. The optimal subject-specific set is the smallest number of electrodes before a significant drop in performance occurs. Research shows this can often be around 50% of the original channels for speech imagery [2].

Quantitative Data on Electrode Reduction

Table 1: Performance of Reduced Electrode Configurations Across Studies

| EEG Paradigm | Full Channel Count | Reduced Channel Count | Performance Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P300 Speller | 32 | 4 | No significant difference in online performance compared to full set. | [30] |

| Speech Imagery BCI | 64 | 32 (50% reduction) | No significant performance loss in classification accuracy. | [2] |

| EEG Source Localization (Single Source) | 231 (HD-EEG) | 6-8 | Equal or better localization accuracy in >88% (synthetic) and >63% (real) of cases. | [26] |

| EEG Source Localization (Three Sources) | 231 (HD-EEG) | 8, 12, 16 | Equal or better accuracy in 58%, 76%, and 82% of cases, respectively. | [26] |

Table 2: Practical Trade-offs: Setup Time & Comfort

| EEG System Type | Average Setup Time | Technician Ease of Setup (0-10) | Participant Comfort | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Wet EEG | Benchmark | 7 (Median) | Highest overall comfort | [31] |

| Dry-Electrode EEG | ~50% faster than standard | 9 (Median for fastest device) | Matched standard EEG at best, but varied | [31] |

Methodologies and Workflows

Electrode Reduction Workflow Using a Wrapper Method

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Item / Method | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm (NSGA-II) | A multi-objective optimization algorithm used to find electrode subsets that minimize channel count while minimizing source localization error. | Automated selection of minimal electrode sets for accurate EEG source estimation [26]. |

| Gibbs Sampling | A Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method for estimating high-dimensional distributions to find optimal electrode configurations across a population. | Identifying a population-based set of 4 posterior electrodes for a P300 speller [30]. |

| Wrapper Methods | Feature selection methods that "wrap" around a specific classification model, evaluating electrode subsets based on their actual predictive performance. | Iteratively reducing electrodes for subject-specific Speech Imagery BCIs without significant accuracy loss [2]. |

| Dry-Electrode EEG Systems | EEG headsets using dry contacts that do not require conductive gel, significantly reducing setup and clean-up time. | Reducing patient and site burden in clinical trials for resting-state and P300 measurements [31]. |

| High-Impedance Amplifiers | Amplifiers capable of handling very high electrode-skin contact impedances (>1 GOhm), crucial for obtaining good signals with dry electrodes. | Enabling stable recordings from dry-electrode systems like ear-EEG and headbands [1] [31]. |

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from studies evaluating reduced EEG montages for seizure detection.

| Study Population | Number of Electrodes in Reduced Montage | Sensitivity for Seizure Detection | Specificity for Seizure Detection | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatric (Epilepsy Monitoring Unit) [33] | 8 | 65.3% | 96.8% | Lower sensitivity for generalized (44%), central (43%), and parietal (71%) seizures. |

| Hospitalized Adults [34] | 7 | 70% | 96% | Poor sensitivity for generalized seizures (55%) and nonconvulsive status epilepticus (55%). |

| Critically Ill Adults [33] | 10 | 67% | Not Specified | Sensitivity is generally reduced compared to full montages. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Retrospective Digital Lead Reduction

This methodology is commonly used to simulate a reduced montage from existing full-montage EEG data [33] [34].

- Data Collection: Obtain full-montage EEG recordings (typically 21 electrodes) from a relevant patient population (e.g., an Epilepsy Monitoring Unit). Include both ictal (seizure) and non-ictal control sequences [33].

- Selection and Anonymization: Randomly select a set of EEG sequences containing a variety of seizure types (focal, generalized, status epilepticus) and control sequences. Anonymize all data [33].

- Digital Montage Reduction: Use EEG software to digitally resample the full montage down to the target reduced montage (e.g., 7 or 8 electrodes). Common electrodes for an 8-lead montage include FP1, FP2, C3, C4, T7, T8, O1, and O2 [33].

- Blinded Review: Have board-certified epileptologists or experienced reviewers evaluate the reduced-montage recordings. Reviewers must be blinded to the original clinical report, patient details, and video data [33] [34].

- Data Analysis: Compare the reviewers' findings from the reduced montage against the original, full-montage EEG report (the "gold standard"). Calculate sensitivity, specificity, and detection rates by seizure type and localization [33] [34].

Protocol 2: Evaluating the Impact of Seizure Localization

This analysis is integral to understanding the performance gaps of reduced montages.

- Categorization by Lobe: Using the gold-standard full-montage reports, categorize each seizure by its onset zone (e.g., frontal, temporal, central, parietal, occipital, generalized) [33].

- Calculate Detection Rates: For each localization category, calculate the proportion of seizures that were successfully identified by the reviewers using the reduced montage [33].

- Statistical Comparison: Use statistical tests, such as Fisher's exact test, to determine if the rate of missed seizures is significantly different across brain regions [33].

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: What is the primary trade-off when using a reduced EEG montage for seizure detection?

The primary trade-off is between setup efficiency and diagnostic sensitivity. While reduced montages (7-10 electrodes) significantly decrease application time and complexity, this comes at the cost of lowered sensitivity for detecting seizures, particularly those that are generalized or originate in brain regions not covered by the sparse electrode array [33] [34]. Specificity, however, remains high, meaning that if a seizure is identified on a reduced montage, it is very likely to be a true positive [33] [34].

Q2: For which type of seizures are reduced montages most likely to fail?

Reduced montages show the highest rates of missed detections for parietal lobe seizures (up to 71% missed) and generalized seizures (up to 44% missed) [33]. They also demonstrate poor sensitivity for nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) and generalized ictal patterns [34]. This is because the limited spatial coverage may not capture seizure activity originating in "silent" brain areas or diffuse activity that requires broader sampling for confident identification.

Q3: We are getting a poor signal from our reference (REF) electrode during setup. What are the systematic troubleshooting steps?

A faulty reference electrode can affect all EEG channels. Follow this systematic workflow to isolate the issue [6]:

Q4: When is it acceptable to proceed with data collection if signal quality issues cannot be fully resolved?

The decision depends on the primary outcome variable of your study [6]:

- If EEG is a secondary variable: In time-sensitive protocols where EEG is not the primary measure, it may be acceptable to proceed with data collection once all troubleshooting steps are exhausted. The signal may improve as electrodes settle [6].

- If EEG is the primary outcome: For studies where EEG data is the critical outcome (e.g., seizure detection studies), every effort must be made to get a clean signal. If unresolved, the session should be canceled and rescheduled to ensure data integrity [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials

The table below details key materials and their functions for setting up and validating reduced EEG montages.

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Ten20 Paste | Conductive paste used to secure cup electrodes and ensure a stable, low-impedance connection between the electrode and the scalp [35]. |

| Gold Cup Electrodes | Reusable electrodes for high-fidelity signal acquisition. Often color-coded for consistent setup (e.g., white for reference, black for bias/ground) [35]. |

| Medical Tape | Provides extra stability to electrodes, particularly those on curved surfaces or areas prone to movement (e.g., earlobes), preventing them from falling off during long recordings [35]. |

| Electrode Starter Kit | A kit typically containing electrodes of specific colors, wires, and paste, ensuring consistency with software color-coding protocols and standardizing the setup process [35]. |

| Digital EEG Software (e.g., EDFbrowser) | Free and open-source software used to review, annotate, and convert EEG files. Essential for the digital montage reduction process in retrospective studies [33]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Is a 4-electrode setup truly sufficient for accurate P300 spelling, and what performance level can I expect?

Yes, research demonstrates that a properly optimized set of four electrodes can perform statistically identically to a full 32-electrode setup in online prospective testing. One study found a specific four-electrode set (PO8, PO7, POz, CPZ) performed effectively, with no significant difference in performance compared to the full montage [36]. The average bit rates plateaued after four channels, with no significant gains from additional electrodes [36].

Q2: Which specific electrode locations form an optimal 4-electrode montage?

Evidence points to posterior electrode placements being critical. A Gibbs sampling method identified the combination PO8, PO7, POz, and CPZ as optimal across a subject population [36]. These locations cover the parietal-occipital regions where the P300 signal is strongest.

Q3: What is the primary methodological approach for selecting an optimal minimal electrode set?

A Gibbs sampling method can identify optimal electrode configurations across a subject population by evaluating the joint distribution of EEG signals and known labels [36]. This approach finds a single, effective configuration for an entire population, eliminating the need for individual calibration.

Q4: My system's performance dropped significantly after moving to a reduced montage. What should I check?

- Verify Electrode Positions: Confirm that the electrodes are placed precisely on PO8, PO7, POz, and CPZ according to the 10-10 international system.

- Check Signal Quality: Ensure impedance values are below 10 kΩ for all electrodes to guarantee good signal quality [37].

- Retrain the Classifier: Always retrain your classification algorithm (e.g., SWLDA, Naïve Bayes) on data collected from the new, reduced montage. Classifier performance is highly dependent on the specific channels used [38].

Q5: How does electrode reduction impact the practical setup and use of a P300 speller?

Reducing electrodes directly addresses major barriers to clinical adoption:

- Reduces system setup time and complexity [36].

- Lowers hardware costs due to fewer electrodes and simpler amplifiers [37] [36].

- Decreases computational requirements and signal bandwidth needs [36].

- Improves user comfort, enhancing prospects for long-term use [38].

Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Quality | Low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) | Verify electrode impedance (<10 kΩ); ensure proper scalp preparation [37]. |

| System Performance | Low classification accuracy with reduced montage | Retrain classifier with new montage data; confirm optimal electrode placement (PO8, PO7, POz, CPZ) [36] [38]. |

| Experimental Design | Inconsistent P300 elicitation | Standardize stimulus parameters (e.g., inter-stimulus interval ~200ms); ensure user focus on target [39]. |

| Data Processing | Inefficient channel selection | Implement Gibbs sampling or Jumpwise Regression for robust, computationally efficient selection [37] [36]. |

Performance Data for Electrode Configurations

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Different P300 Speller Electrode Montages

| Number of Electrodes | Specific Electrodes | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 32 (Full Montage) | Standard 10-10 system locations | Baseline performance | [36] |

| 8 (Common Reduced) | C3, Cz, C4, P3, Pz, P4, O1, O2 | Statistically significant P300 detection (p<0.01) with medium/large effect sizes [39] | [39] |

| 6 (Empirically Chosen) | Fz, Cz, Pz, Oz, P3, P4 | Common research configuration | [36] |

| 4 (Optimized) | PO8, PO7, POz, CPZ | No significant performance difference vs. full montage; performance plateau | [36] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics from P300 Studies with Electrode Reduction

| Study Focus | Optimal Channel Count | Accuracy | Information Transfer Rate (ITR) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wireless P300 System [39] | 8+ electrodes | 85% (40 trials) to 100% (100 trials) | Not Reported | System functionality confirmed with wireless stimulus presentation |

| Population Optimization [36] | 4 electrodes | Not significantly different from 32-channel | Plateau after 4 electrodes (26.4 bits/min with 3 electrodes) | Gibbs sampling identified population-optimal montage |

| Genetic Algorithm Optimization [26] | 6-8 electrodes (Source Localization) | Comparable to HD-EEG (>88% cases) | Not Applicable | Method identifies minimal electrode subsets for specific source activities |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Validating a 4-Electrode P300 Speller

Objective: To determine if an optimized 4-electrode montage (PO8, PO7, POz, CPZ) can achieve performance statistically equivalent to a full 32-electrode montage in online P300 speller operation [36].

Equipment and Setup:

- EEG amplifier system (e.g., g.tec amplifiers)

- Electrode cap with 32 channels in established configuration

- Active EEG electrodes

- Stimulus presentation computer running BCI2000 or similar software

- Display monitor for P300 speller grid

Participant Preparation:

- 15+ healthy subjects with normal or corrected-to-normal vision

- Apply electrode cap according to 10-10 international system

- Reduce impedance for all electrodes to <10 kΩ [37]

- Ground electrode on forehead, reference on right earlobe [40]

Data Collection Protocol:

- Calibration Phase: Present "PACK MY BOX WITH FIVE DOZEN LIQUOR JUGS" for subject to spell with full 32-electrode montage [40] [36].

- Stimulus Parameters: Use Row/Column paradigm (Farwell & Donchin, 1988) with 5-15 repetitions [40].

- Signal Processing: Bandpass filter EEG data to [0.5 Hz, 30 Hz] and digitize at 256 Hz [37].

- Classifier Training: Employ Naïve Bayes classifier or Stepwise Linear Discriminant Analysis (SWLDA) on calibration data [36] [41].

Experimental Conditions:

- Full Montage: Online testing with all 32 electrodes

- Reduced Montage: Online testing with only PO8, PO7, POz, CPZ electrodes

- Control Condition: Test with empirically chosen 6-electrode set (Fz, Cz, Pz, Oz, P3, P4) for comparison

Data Analysis:

- Perform repeated-measures ANOVA to compare bit rates between conditions

- Use paired t-tests for pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction

- Calculate information transfer rate (ITR) as primary performance metric [36]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for P300 Speller Studies

| Item | Specification/Example | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| EEG Amplifier | g.tec g.USBamp, OpenBCI board [37] [40] | Signal acquisition and digitization |

| Electrode Cap | 32-channel cap with 10-10 international system [36] | Standardized electrode placement |

| Active EEG Electrodes | Guger Technologies active electrodes [36] | Improved signal quality with pre-amplification |

| Electrode Gel | Electrolyte gel | Maintain conductivity and reduce impedance |

| BCI Software Suite | BCI2000, OpenViBE [37] [40] | Experiment control, data acquisition, and signal processing |

| Stimulus Presentation Monitor | Standard computer monitor | Visual presentation of P300 speller grid |

| Classifier Algorithms | Naïve Bayes, SWLDA [36] [41] | Translation of EEG features into character selection |

Methodology Visualization

Diagram 1: Electrode Optimization and Validation Workflow

Diagram 2: Optimal 4-Electrode Montage for P300 Speller

Implementing Dry Electrode and Wearable Systems for Rapid Deployment

Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses common technical challenges when using dry-electrode EEG systems for rapid deployment, helping researchers maintain data quality and experimental efficiency.

Table 1: Common Technical Issues and Solutions

| Problem Category | Specific Issue | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions & Verification Steps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Quality | Poor signal-to-noise ratio, high-frequency noise [31] | High electrode-skin impedance; Motion artifacts; Environmental electrical interference. | Ensure proper sensor-scalp contact via headset adjustment; Use systems with built-in common-mode follower circuitry and Faraday cages [42] [43]. |

| Signal Quality | Attenuated low-frequency (<6 Hz) or induced gamma (40-80 Hz) activity [31] | Hardware limitations of specific dry-electrode systems. | Benchmark device performance for target frequency band; Avoid these bands for analysis or select a system validated for them [31]. |

| Subject Comfort & Compliance | Discomfort during prolonged use, declining comfort over time [31] | Excessive pressure from rigid electrode structures; Improper headset fit. | Select systems with ergonomic designs and adjustable straps; Limit recording session length; Use soft foam padding [42]. |

| Operational Efficiency | Prolonged setup or cleaning | Complex montages; Lack of technician training. | Use pre-configured headbands; Implement standardized training protocols [44]. Opt for devices with easy cleaning (e.g., with 70% alcohol) [42]. |

| Data Integrity | Inconsistent performance in reduced-electrode montages [45] | Use of a generic, non-optimized electrode subset. | Employ systematic electrode reduction algorithms (e.g., wrapper methods) to identify subject-specific optimal channels [45]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does the signal quality of dry-electrode EEG compare to conventional wet EEG? High-quality dry-electrode systems can perform on par with wet EEG for many applications. Studies show over 90% correlation with wet system signals and adequate capture of resting-state EEG and P300 evoked potentials [42] [31]. However, some dry systems may face challenges with very low-frequency (<6 Hz) or induced gamma activity, so device selection should be matched to the research context [31].

Q2: To what extent can we reduce the number of electrodes without significant performance loss? Substantial reduction is often possible. Research on Speech Imagery BCIs found that 64 channels could be reduced by 50% without a significant loss in classification accuracy [45]. For P300 speller systems, a minimal set of just four optimized electrodes has been shown to perform statistically identically to a full 32-electrode montage [36]. The optimal configuration is often subject-specific [45].

Q3: What are the key factors in choosing a dry-electrode system for a clinical trial setting? Key factors include [31]:

- Data Quality for the Application: Ensure the system captures the neural signals of interest (e.g., P300, resting-state).

- Setup and Clean-up Speed: Dry systems can be up to twice as fast as wet EEG, reducing site burden.

- Participant Comfort: While a key advantage, comfort varies by device and can decline over time.

- Ease of Use: Technicians rate some dry systems as significantly easier to set up and clean.

Q4: How can I identify the optimal subset of electrodes for my specific BCI experiment? A systematic, data-driven approach is recommended. A wrapper method, which evaluates channel subsets based on classification accuracy, is an effective technique [45]. This involves iteratively reducing electrodes and re-evaluating performance to find the minimal set that maintains high accuracy for your task and subject pool.

Experimental Protocols for Electrode Optimization

This section provides a detailed methodology for conducting electrode reduction studies, a core research area for minimizing setup time.

Protocol 1: Systematic Electrode Reduction for a Specific BCI Paradigm

This protocol is based on research that successfully reduced channels for Speech Imagery and P300 speller BCIs [45] [36].

1. Objective: To determine the minimal number of EEG electrodes and their optimal positions for a specific BCI task (e.g., motor imagery, P300) without significantly compromising classification accuracy.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- EEG system with a high channel count (e.g., 64 electrodes).

- Standardized stimulus presentation software.

- Computing environment with machine learning libraries (e.g., Python scikit-learn, MATLAB).

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Data Collection. Record EEG data from multiple subjects using a full high-density montage (e.g., 64-channels based on the 10-20 system) while they perform the target BCI task.