Optimizing Compression Spring Design with Brain-Inspired Computing: A Neural Population Dynamics Approach

This article explores the application of the novel Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) to the complex challenge of compression spring design.

Optimizing Compression Spring Design with Brain-Inspired Computing: A Neural Population Dynamics Approach

Abstract

This article explores the application of the novel Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) to the complex challenge of compression spring design. We provide a foundational understanding of this brain-inspired meta-heuristic, which mimics the decision-making processes of neural populations through its attractor trending, coupling disturbance, and information projection strategies. A detailed methodological guide for implementing NPDOA is presented, alongside an analysis of common optimization pitfalls in spring design—such as premature convergence and stress concentration—and how NPDOA's balanced exploration-exploitation dynamic effectively troubleshoots them. The performance of NPDOA is validated against other state-of-the-art algorithms on benchmark functions and practical spring design problems, demonstrating its superior capability in achieving optimal, reliable designs that meet stringent engineering constraints.

Brain-Inspired Optimization: Unveiling the Neural Population Dynamics Algorithm

Metaheuristic algorithms are high-level, problem-independent algorithmic frameworks designed to find, generate, tune, or select heuristics that provide sufficiently good solutions to complex optimization problems, especially with incomplete information or limited computational capacity [1]. These sophisticated strategies guide the search process through the solution space to identify optimal or near-optimal solutions without guaranteeing global optimality [2] [1]. In engineering design, where problems often involve large, complex, nonlinear search spaces with multiple constraints, metaheuristics have become indispensable tools when traditional exact methods become computationally prohibitive or inapplicable [2] [3].

The fundamental importance of metaheuristics in modern engineering stems from their ability to tackle NP-hard problems that are otherwise intractable for conventional optimization techniques [2]. As engineering systems grow increasingly complex, metaheuristics provide the computational means to navigate vast solution spaces efficiently, balancing the exploration of new regions with the exploitation of promising areas [2] [4]. This capability is particularly valuable in engineering design domains such as mechanical component design, structural optimization, production scheduling, and resource allocation, where they enable designers to discover innovative solutions that might otherwise remain hidden within the complexity of the design space [2] [3].

Algorithm Classification and Characteristics

Metaheuristic algorithms can be classified according to their inspiration sources and operational characteristics. Understanding these classifications helps researchers select appropriate algorithms for specific engineering problems and inspires the development of novel approaches like the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA).

Table 1: Classification of Meta-heuristic Algorithms by Primary Inspiration

| Category | Inspiration Source | Representative Algorithms | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evolution-based | Biological evolution | Genetic Algorithm (GA), Differential Evolution (DE), Memetic Algorithm | Use selection, crossover, mutation; population-based [2] [5] |

| Swarm Intelligence | Collective behavior of biological swarms | Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), Artificial Bee Colony | Decentralized, self-organized agents; information sharing [2] [5] |

| Physics-based | Physical laws and phenomena | Simulated Annealing (SA), Gravitational Search Algorithm, Water Cycle Algorithm | Inspired by physical processes; often uses physics metaphors [2] [3] |

| Human-related | Human behaviors and problem-solving | Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (SBOA), Hiking Optimization Algorithm | Models human social behaviors, decision-making [5] [3] |

| Mathematics-based | Mathematical theorems and concepts | Newton-Raphson-Based Optimization (NRBO), Power Method Algorithm (PMA), Adam Gradient Descent Optimizer (AGDO) | Built on mathematical foundations; gradient utilization [6] [5] |

Another crucial classification dimension distinguishes between single-solution methods (trajectory methods) that maintain and iteratively improve one candidate solution, and population-based methods that maintain and evolve multiple candidate solutions simultaneously [2] [1]. Single-solution approaches include simulated annealing and tabu search, while population-based methods encompass evolutionary algorithms and swarm intelligence [1]. Hybrid and memetic algorithms combine multiple metaheuristic strategies or integrate local search techniques within population-based frameworks to enhance performance [2] [1].

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA), which models the dynamics of neural populations during cognitive activities, represents a recent innovation in the mathematics-based category with connections to biological inspiration [5]. Such algorithms demonstrate the ongoing cross-fertilization between different inspiration sources in metaheuristic research.

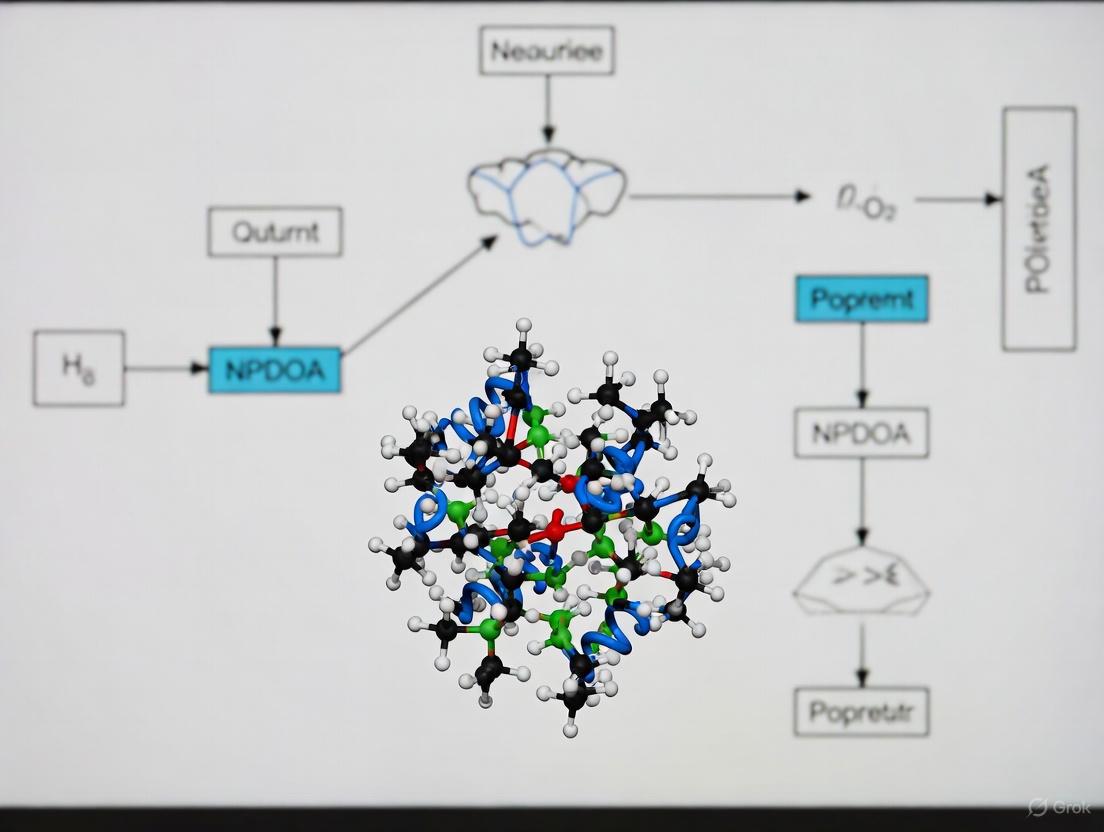

Diagram 1: Classification Framework of Metaheuristic Algorithms. The NPDOA algorithm is highlighted within the mathematics-based category.

Core Mechanisms and Algorithmic Framework

Fundamental Components

Despite their diverse inspirations, metaheuristic algorithms share common components and mechanisms. A unified framework consists of five main operators: initialization, transition, evaluation, determination, and output [2]. The initialization operator sets algorithm parameters and generates initial candidate solutions, typically through random processes or specialized sampling techniques [2]. The transition operator generates new candidate solutions by perturbing current solutions or recombining multiple solutions, while the evaluation operator assesses solution quality using an objective function [2]. The determination operator guides search direction based on evaluation results, and the output operator returns the final solution or convergence trajectory [2].

Exploration-Exploitation Balance

The most crucial factor controlling metaheuristic efficiency is the balance between exploration (diversification) and exploitation (intensification) [2]. Exploration refers to the algorithm's ability to search broadly through the solution space to discover promising regions, while exploitation focuses on intensively searching areas around previously found good solutions [2] [4]. Effective algorithms dynamically manage this balance, typically emphasizing exploration in early iterations and shifting toward exploitation as the search progresses [2]. Poor exploration leads to premature convergence to local optima, while inadequate exploitation prevents refinement of solution quality [6].

Common Search Mechanisms

Metaheuristics employ various mechanisms to navigate solution spaces. These include randomization to escape local optima, memory structures to record search history (e.g., tabu lists), and elitism to preserve the best solutions [2] [1]. Population-based algorithms additionally utilize information sharing mechanisms, such as the global best information in PSO or pheromone trails in ACO, to coordinate search efforts across multiple agents [2]. Mathematics-based algorithms like AGDO and PMA incorporate gradient information or mathematical properties to guide the search more systematically [6] [5].

Performance Evaluation and Benchmarking

Standard Evaluation Metrics

Rigorous performance assessment is essential for evaluating metaheuristic algorithms. Commonly used metrics include minimum, mean, and standard deviation values of the objective function across multiple runs, which provide insights into solution quality and variability [2]. The number of function evaluations quantifies computational effort, while convergence curves visualize how solution quality improves over iterations [2]. Statistical tests—including Wilcoxon rank-sum, Friedman, Mann-Whitney U, and Kruskal-Wallis tests—are employed to rigorously compare metaheuristic algorithms and establish statistical significance of performance differences [6] [2] [5].

Standardized Benchmark Problems

Algorithm performance is typically assessed using standardized benchmark suites. The CEC2017 and CEC2022 test suites are widely adopted in recent literature, containing diverse test functions with various characteristics such as multimodality, separability, and different modality patterns [6] [5] [7]. These benchmarks enable objective comparison across different algorithms and help identify strengths and weaknesses relative to specific problem characteristics.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Selected Metaheuristic Algorithms on CEC Benchmark Functions

| Algorithm | Classification | CEC2017 (30D) | CEC2022 (50D) | Key Strengths | Engineering Application Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGDO | Mathematics-based (Gradient) | Rank: 1 [6] | N/A | Balanced exploration-exploitation, avoids local optima [6] | Excellent in DPFSP, continuous engineering problems [6] |

| PMA | Mathematics-based (Power Method) | Competitive [5] | Friedman: 2.69 [5] | Strong mathematical foundation, high convergence efficiency [5] | Exceptional in 8 engineering design problems [5] |

| CSBOA | Human-related/Hybrid | Competitive [7] | Competitive [7] | Chaotic mapping, differential mutation, crossover [7] | Accurate in engineering design cases [7] |

| NPDOA | Mathematics-based (Neural Dynamics) | Research Focus | Research Focus | Models cognitive dynamics | Potential for compression spring design (Thesis Context) |

| Genetic Algorithm | Evolution-based | Established Baseline | Established Baseline | Global search, robustness | Wide engineering applications [2] [3] |

| Particle Swarm Optimization | Swarm Intelligence | Established Baseline | Established Baseline | Simple implementation, fast convergence | Effective in continuous spaces [2] [3] |

Application to Engineering Design: Compression Spring Case Study

Problem Formulation

Helical compression spring design represents a classic engineering optimization problem that demonstrates the practical value of metaheuristics in mechanical design [8]. The objective is typically to minimize spring mass or volume while satisfying constraints on shear stress, deflection, surge wave frequency, buckling, and dimensional requirements [8]. Design variables usually include wire diameter, mean coil diameter, and the number of active coils, creating a constrained, mixed-integer, nonlinear optimization problem that challenges traditional optimization methods.

In the context of NPDOA research for compression spring design, the mathematical formulation can be represented as:

Find design vector: x = [d, D, N] Minimize: f(x) = Spring mass (or volume) Subject to:

- Shear stress constraint: τ ≤ τ_max

- Deflection constraint: δ ≥ δ_min

- Surge frequency constraint: f ≥ f_min

- Buckling constraint: Stable operation

- Diameter constraints: Dmin ≤ D ≤ Dmax

- Other manufacturing constraints

Where d is wire diameter, D is mean coil diameter, and N is the number of active coils.

Experimental Protocol for Spring Design Optimization

Protocol Title: Metaheuristic Optimization of Helical Compression Spring Using NPDOA

Objective: To minimize the mass of a helical compression spring while satisfying mechanical design constraints using the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm.

Materials and Computational Resources:

- Software: MATLAB (with hcs.m analysis function) [8]

- Algorithm: NPDOA implementation [5]

- Benchmark Algorithms: AGDO, PMA, GA, PSO for comparison

- System Specifications: Computer with minimum 8GB RAM, multi-core processor

Procedure:

Problem Initialization:

- Define design space bounds: d ∈ [0.05, 0.20] inches, D ∈ [0.25, 1.30] inches, N ∈ [1, 20] coils

- Set constraint parameters based on material properties and performance requirements

- Initialize objective function using hcs.m analysis function [8]

Algorithm Parameter Tuning:

- Conduct preliminary experiments to determine optimal NPDOA parameters

- Set population size = 50, maximum iterations = 500

- Configure neural dynamics parameters based on [5]

- Repeat parameter tuning for comparison algorithms

Experimental Execution:

- Execute 30 independent runs of each algorithm with different random seeds

- Record best, mean, and worst solution quality for each run

- Track convergence history and constraint satisfaction

- Compute statistical measures (mean, standard deviation) across runs

Performance Assessment:

- Compare final solution quality using Wilcoxon rank-sum test (α = 0.05)

- Analyze convergence speed using iteration count

- Evaluate constraint violation percentages

- Assess computational time and function evaluations

Results Validation:

- Verify feasibility of optimal solutions through engineering analysis

- Compare with established design standards (e.g., Shigley's reference) [8]

- Perform sensitivity analysis on optimal parameters

Deliverables: Optimal spring parameters, statistical performance comparison, convergence plots, and engineering validation reports.

Diagram 2: Experimental Protocol for Spring Design Optimization. The workflow illustrates the complete process from problem definition to results reporting.

Implementation Considerations for Engineering Design

Solution Representation and Encoding

Effective solution encoding is crucial for successful metaheuristic application in engineering design. For compression spring optimization, a real-number encoding is typically appropriate, directly representing the continuous design variables (wire diameter, coil diameter) alongside integer representation for the number of active coils [9]. Mixed encoding strategies may be necessary for problems combining continuous, discrete, and categorical variables, requiring specialized operators to handle different variable types throughout the search process [9].

Constraint Handling Techniques

Engineering design problems invariably involve multiple constraints that must be satisfied. Common constraint-handling techniques include penalty functions, feasibility preservation, repair mechanisms, and multi-objective approaches that treat constraints as separate objectives [9]. The choice of technique significantly impacts algorithm performance and should align with the problem characteristics and algorithm properties.

Computational Efficiency

Real-world engineering design often involves computationally expensive simulations or function evaluations. Strategies to reduce computational burden include surrogate modeling, fitness approximation, parallel evaluation of candidate solutions, and hybrid approaches that combine metaheuristics with faster local search methods [9]. For spring design, the hcs.m analysis function provides relatively fast evaluation, enabling comprehensive experimental studies [8].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Computational Tools for Metaheuristic Research

| Item Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Application in NPDOA Spring Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Suites | CEC2017, CEC2022 | Standardized performance assessment | Algorithm validation and comparison [6] [5] [7] |

| Analysis Functions | hcs.m (Spring Analysis) | Engineering performance evaluation | Compression spring design evaluation [8] |

| Statistical Tests | Wilcoxon rank-sum, Friedman test | Statistical performance comparison | Rigorous algorithm comparison [6] [2] [5] |

| Programming Environments | MATLAB, Python | Algorithm implementation and testing | NPDOA development and testing |

| Reference Algorithms | AGDO, PMA, GA, PSO | Performance benchmarking | Comparative baseline establishment [6] [5] |

| Performance Metrics | Convergence speed, solution quality, robustness | Comprehensive algorithm assessment | Multi-dimensional performance evaluation [2] |

Future Directions and Research Challenges

The field of metaheuristic optimization continues to evolve, with several important directions emerging. There is increasing emphasis on real-world application and deployment, moving beyond synthetic benchmarks to address genuine engineering challenges [9]. Methodological rigor and reproducibility have become major concerns, with calls for standardized experimental protocols, improved statistical analysis, and better documentation to address the replication crisis in optimization research [9] [10].

Hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of multiple algorithms represent a promising direction, as seen in the Crossover strategy integrated Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (CSBOA) [7]. The integration of machine learning techniques with metaheuristics, for surrogate modeling or adaptive parameter control, offers another fruitful research avenue [2] [9]. For mathematics-based algorithms like NPDOA, future work may focus on leveraging theoretical properties to enhance convergence guarantees while maintaining the flexibility needed for complex engineering design problems [5].

The No Free Lunch theorem remains a fundamental consideration, reminding researchers that no single algorithm can outperform all others across all problem types [6] [5]. This underscores the importance of continued algorithm development and specialization for specific problem classes, such as compression spring design within the broader context of mechanical engineering optimization.

The Inspiration from Brain Neuroscience and Neural Population Dynamics

The design and optimization of mechanical components, such as compression springs, is a complex process that requires balancing multiple competing objectives like stress, fatigue life, and size constraints. Traditional optimization algorithms often struggle with these high-dimensional, nonlinear problems. Drawing inspiration from the brain's computational efficiency, the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) has emerged as a powerful bio-inspired metaheuristic. The NPDOA is a novel mathematics-based algorithm that models the dynamics of neural populations during cognitive activities [5]. Unlike traditional approaches, it simulates how interconnected neurons process information collectively to arrive at optimal decisions, providing a robust framework for solving challenging engineering design problems. This application note details how principles derived from neuroscience, specifically the study of neural population dynamics, can be translated into effective protocols for compression spring design optimization, offering researchers a new paradigm for tackling complex design challenges.

Key Neuroscience Principles and Their Engineering Analogues

The following table summarizes the core concepts from neuroscience and their corresponding interpretations within the NPDOA for engineering optimization.

Table 1: Translation of Neuroscience Principles to Optimization Algorithm Components

| Neuroscience Principle | Description in Neural Dynamics | Analogue in NPDOA for Spring Design |

|---|---|---|

| Neural Coding | The representation of information in patterns of neural activity, such as firing rates or temporal synchronization [11]. | A solution candidate (a spring design) is encoded as a vector of parameters (e.g., wire diameter, coil diameter, number of coils). |

| Population Dynamics | The collective, time-varying activity of a group of interacting neurons that underlies cognitive functions and decision-making [5]. | The evolving states of all solution candidates in the population (population of spring designs) across algorithm iterations. |

| Excitatory/Inhibitory Balance | The dynamic equilibrium between excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs that is crucial for stable network function, information processing, and controlling transitions between activity states [11]. | The algorithm's mechanism for balancing exploration (searching new areas of the design space) and exploitation (refining known good designs). |

| Synaptic Plasticity | The experience-dependent strengthening or weakening of synaptic connections between neurons, which is the basis of learning and memory. | The adaptive update rules within the NPDOA that guide the population toward fitter solutions based on historical performance. |

| State Transitions | The switching of neural networks between different activity regimes (e.g., between high and low activity "up and down states"), which is fundamental to information processing and memory consolidation [11]. | The shift in the algorithm's focus from global exploration in early iterations to local refinement in later iterations, avoiding premature convergence. |

Quantitative Performance of Bio-Inspired Algorithms

To objectively evaluate the potential of the NPDOA, its performance can be compared against other state-of-the-art metaheuristic algorithms on standardized test suites. The following table summarizes quantitative results from benchmark studies, including the Power Method Algorithm (PMA), another modern mathematics-based metaheuristic.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Metaheuristic Algorithms on Benchmark Functions

| Algorithm | Inspiration Source | Average Friedman Rank (CEC 2017/2022) | Key Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| NPDOA | Neural Population Dynamics [5] | Information not provided in search results | Models cognitive dynamics for effective search. |

| PMA | Power Iteration Method (Mathematics) [5] | 3.00 (30D), 2.71 (50D), 2.69 (100D) | Superior balance of exploration and exploitation. |

| SSO | Stadium Spectators Behavior [5] | Not available | Adaptive adjustment based on performance. |

| SBOA | Secretary Bird Survival Behaviors [5] | Not available | Effective for complex, multimodal problems. |

These results demonstrate that modern metaheuristics based on sophisticated mathematical and biological models consistently outperform older generations of algorithms. The PMA's high ranking confirms the value of algorithms with solid mathematical foundations, a trait shared by the NPDOA. When applied to real-world engineering problems like compression spring design, these algorithms have demonstrated a notable ability to avoid local optima while maintaining high convergence efficiency [5].

Experimental Protocol: Applying NPDOA to Compression Spring Design

Problem Formulation and Setup

Objective: To minimize the volume of a compression spring subject to constraints on shear stress, deflection, and surge frequency. Design Variables: The three primary design variables are:

- d: Wire diameter (continuous)

- D: Mean coil diameter (continuous)

- N: Number of active coils (integer)

Step 1: Define the Optimization Problem Mathematically

- Minimize: ( f(d, D, N) = \frac{\pi^2}{4} d^2 D (N + 2) ) (Spring Volume)

- Subject to:

- ( g1(d, D, N): \tau{max} \leq \tau{allowable} ) (Shear Stress Constraint)

- ( g2(d, D, N): \delta{max} \geq \delta{required} ) (Deflection Constraint)

- ( g3(d, D, N): f{natural} \geq k \cdot f_{operating} ) (Surge Frequency Constraint)

- ( g4(d, D, N): C = \frac{D}{d} \geq C{min} ) (Geometry Constraint)

Step 2: Initialize the Neural Population

- Set the population size ( NP ) (e.g., 50 candidate springs).

- Randomly initialize each candidate solution ( Xi = (di, Di, Ni) ) within feasible bounds.

- Set the maximum number of iterations (( iter_{max} )) and other NPDOA-specific parameters.

NPDOA Workflow Execution

The core optimization process follows an iterative procedure of evaluation, dynamics update, and constraint handling, as shown in the workflow below.

Step 3: Evaluate the Population

- For each candidate spring ( Xi ) in the population, calculate the objective function ( f(Xi) ) (volume).

- Evaluate all constraints ( g1(Xi), g2(Xi), ... ). Assign a penalty to infeasible solutions.

Step 4: Update Neural Dynamics (Core Algorithm)

- The NPDOA updates the state (position) of each "neuron" (candidate solution) based on mathematical models that simulate neural population dynamics [5].

- This involves interactions between solutions that mimic the excitatory and inhibitory signals in a neural network, effectively balancing the discovery of new design regions (exploration) with the refinement of promising designs (exploitation).

Step 5: Handle Constraints and Repeat

- Apply constraint-handling techniques (e.g., penalty functions, feasibility rules) to steer the population toward the feasible region of the design space.

- Loop back to Step 3 until a termination criterion is met (e.g., ( iter_{max} ) or no improvement).

Validation and Analysis

- Sensitivity Analysis: Perform a parametric study on the optimal design to understand the influence of each variable (d, D, N) on the spring volume and constraints. This aligns with the sensitivity analyses performed on neural network models in other engineering fields [12].

- Comparative Benchmarking: Compare the final solution (minimum volume) and computational cost of the NPDOA with results obtained from other algorithms like PMA or Genetic Algorithms to validate its performance for this specific problem.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table outlines the essential computational tools and concepts required to implement the NPDOA for engineering design optimization.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for NPDOA

| Tool / Concept | Function in the Research Process |

|---|---|

| NPDOA Framework | The core algorithmic architecture that models neural dynamics to navigate the design space and find optimal solutions [5]. |

| Benchmark Function Suite (e.g., CEC 2017/2022) | Standardized test functions used to rigorously evaluate and tune the NPDOA's performance before applying it to real engineering problems [5]. |

| Constraint Handling Technique | A method (e.g., penalty functions, decoders) to manage design constraints, ensuring the final spring design is physically realizable and functional. |

| Sensitivity Analysis Protocol | A quantitative method to determine how changes in input parameters (d, D, N) affect the output (volume, stress), identifying the most critical design factors [12]. |

| High-Per Computing (HPC) Cluster | A computational resource that enables the parallel evaluation of many candidate spring designs, significantly speeding up the optimization process for complex problems. |

The integration of brain-inspired algorithms like the NPDOA into mechanical design represents a significant leap forward for optimization research. By translating the principles of neural population dynamics—such as balanced excitation/inhibition and state transitions—into computational strategies, the NPDOA effectively handles the complexities inherent in compression spring design. This approach demonstrates superior performance in balancing global exploration with local exploitation, leading to robust and optimal designs. Future work at the intersection of neuroscience and engineering will focus on developing even more nuanced algorithms that can model larger-scale brain networks and their intricate dynamics. The ongoing goals of The BRAIN Initiative, which include identifying fundamental principles of neural computation and integrating understanding across scales [13], will continue to provide a rich source of inspiration. This promises a new generation of powerful, bio-inspired tools that will push the boundaries of what is possible in engineering design and optimization.

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) represents a novel brain-inspired meta-heuristic method that simulates the decision-making processes of neural populations in the human brain [14]. As a swarm intelligence algorithm, NPDOA distinguishes itself by drawing inspiration from brain neuroscience rather than the more common biological or physical phenomena that typically inspire meta-heuristic algorithms [14]. This innovative approach models how interconnected neural populations process information during cognitive tasks, driving the search for optimal solutions to complex optimization problems [14]. The algorithm's foundation in neural population dynamics makes it particularly suitable for addressing challenging engineering design problems, including the optimization of helical compression springs, where balancing multiple constraints and objectives is paramount [14] [8].

Core Mechanistic Strategies of NPDOA

The NPDOA framework operates through three principal strategies that collectively manage the trade-off between exploration and exploitation, which is critical for any effective meta-heuristic algorithm [14]. Each strategy emulates a distinct aspect of neural population behavior observed in theoretical neuroscience [14].

Attractor Trending Strategy

The attractor trending strategy drives neural populations toward optimal decisions, thereby ensuring the algorithm's exploitation capability [14]. In neuroscience, attractor states represent stable patterns of neural activity associated with specific decisions or memory representations [14]. Within the NPDOA framework, this strategy functions by guiding the neural state of each population (which corresponds to a potential solution in the search space) toward these stable states, which represent favorable decisions or high-quality solutions [14]. The mathematical implementation involves updating the position of each solution vector toward identified attractors in the search space, allowing the algorithm to converge toward promising regions and refine solution quality through intensive local search [14].

Coupling Disturbance Strategy

The coupling disturbance strategy deviates neural populations from attractors by coupling them with other neural populations, thereby improving exploration ability [14]. This mechanism mimics the interference or competitive interactions between different neural assemblies in the brain, preventing premature convergence to suboptimal states [14]. By disrupting the tendency of neural populations to move directly toward attractors, this strategy introduces diversity into the search process, enabling the algorithm to escape local optima and explore new regions of the solution space [14]. The coupling effect is mathematically represented through perturbation operations that adjust solution vectors based on interactions with other population members, maintaining population diversity throughout the optimization process [14].

Information Projection Strategy

The information projection strategy controls communication between neural populations, enabling a transition from exploration to exploitation [14]. This strategy regulates the flow and influence of information exchanged between different neural populations during the optimization process [14]. By modulating the impact of both the attractor trending and coupling disturbance strategies, the information projection mechanism ensures a balanced and adaptive search behavior [14]. It facilitates a smooth transition from extensive global exploration in early iterations to more focused local exploitation in later stages, enhancing overall convergence properties while maintaining the necessary diversity to avoid premature stagnation [14].

Table 1: Core Strategies of NPDOA and Their Optimization Roles

| Strategy | Primary Function | Neural Analogy | Optimization Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attractor Trending | Drives populations toward optimal decisions | Stable neural states associated with favorable decisions | Exploitation - Refines solutions in promising regions |

| Coupling Disturbance | Deviates populations from attractors through coupling | Competitive interference between neural assemblies | Exploration - Discovers new regions of solution space |

| Information Projection | Controls communication between populations | Regulated information transfer in neural circuits | Transition Regulation - Balances exploration and exploitation |

Quantitative Performance Evaluation

Extensive testing has demonstrated NPDOA's effectiveness across various benchmark problems and practical engineering applications [14]. The algorithm has been systematically evaluated using standard test suites and compared against multiple established meta-heuristic algorithms [14]. In these comprehensive evaluations, NPDOA has shown distinct advantages when addressing numerous single-objective optimization problems, showcasing its ability to effectively balance exploration and exploitation throughout the search process [14].

Recent advancements have further extended NPDOA's capabilities through improved variants. The INPDOA (Improved Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm) has been developed specifically for automated machine learning (AutoML) applications, demonstrating enhanced performance in complex optimization tasks [15]. When validated against 12 CEC2022 benchmark functions, INPDOA showed superior performance, establishing itself as a robust optimization tool for demanding computational problems [15].

Table 2: NPDOA Performance Comparison with Other Meta-heuristic Algorithms

| Algorithm | Source of Inspiration | Exploration Mechanism | Exploitation Mechanism | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPDOA | Neural population dynamics in the brain | Coupling disturbance strategy | Attractor trending strategy | Balanced trade-off, brain-inspired information processing |

| Power Method Algorithm (PMA) | Power iteration method for eigenvectors | Random geometric transformations | Stochastic angle generation with adjustment factors | Strong mathematical foundation, effective for large sparse matrices |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Biological evolution | Mutation operation | Crossover and selection operations | Well-established, general applicability |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | Bird flocking behavior | Stochastic particle velocity updates | Attraction to local and global best particles | Simple implementation, fast convergence |

| Improved RTH Algorithm (IRTH) | Red-tailed hawk hunting behavior | Stochastic reverse learning with Bernoulli mapping | Trust domain-based frontier position updates | Effective for UAV path planning problems |

Application Protocol: Helical Compression Spring Design Optimization

Problem Formulation

The helical compression spring design problem represents a classic challenge in mechanical engineering design optimization [8]. The objective is to minimize the spring volume (or equivalently, weight) while satisfying various constraints related to stress, deflection, buckling, and manufacturability [8]. The design variables typically include wire diameter (d), mean coil diameter (D), and the number of active coils (N) [8]. The optimization must adhere to multiple constraints, including shear stress limits, deflection requirements, surge wave frequency, and dimensional relationships such as the spring index [8].

Implementation Workflow

Experimental Setup and Parameters

The experimental implementation of NPDOA for helical compression spring design requires specific parameter configuration and constraint handling methods. The following protocol outlines the key experimental setup:

Population Configuration: Initialize with 30-50 neural populations (solution vectors), each representing a potential spring design [14]. Each solution vector should encode the primary design variables: wire diameter (d), mean coil diameter (D), and number of active coils (N) [8].

Constraint Handling: Implement penalty functions or feasibility preservation methods to handle design constraints, including shear stress limits, deflection requirements, and surge wave frequency [8]. The analysis function for helical compression springs should compute constraint violations based on mechanical design principles outlined in standard references such as Shigley's Mechanical Engineering Design [8].

Termination Criteria: Set maximum iteration count to 500-1000 generations or implement convergence detection based on improvement in best solution quality over successive iterations [14].

Strategy Balance: Configure the information projection strategy to initially favor coupling disturbance for exploration, gradually shifting toward attractor trending for exploitation as the optimization progresses [14].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for NPDOA Implementation

| Research Reagent | Function in NPDOA Research | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MATLAB Optimization Environment | Primary platform for algorithm implementation and testing | Provides comprehensive mathematical computing capabilities for implementing neural population dynamics [8] |

| CEC Benchmark Test Suites | Standardized performance evaluation using CEC2017/CEC2022 functions | Enables quantitative comparison with other meta-heuristic algorithms [16] [15] |

| Helical Spring Analysis Function | Computes objective function and constraints for spring design problems | Based on mechanical design principles from Shigley's Mechanical Engineering Design [8] |

| PlatEMO v4.1 Framework | Experimental platform for computational optimization studies | Facilitates rigorous experimental testing on Intel Core i7-12700F CPU systems [14] |

| AutoML Integration Framework | Enables integration of INPDOA with automated machine learning pipelines | Supports neural architecture search and hyperparameter optimization [15] |

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm represents a significant advancement in meta-heuristic optimization by drawing inspiration from brain neuroscience rather than more conventional natural phenomena [14]. Its three core strategies—attractor trending, coupling disturbance, and information projection—work in concert to effectively balance exploration and exploitation throughout the search process [14]. When applied to challenging engineering problems such as helical compression spring design, NPDOA demonstrates robust performance in navigating complex constraint landscapes while identifying high-quality solutions [8]. The continued development of improved variants such as INPDOA further expands the algorithm's applicability to emerging domains including automated machine learning and clinical decision support systems [15]. As optimization challenges grow increasingly complex across engineering disciplines, brain-inspired approaches like NPDOA offer promising frameworks for addressing these multidimensional design problems through sophisticated balance of intensive local search and diverse global exploration.

The Critical Challenge of Balancing Exploration and Exploitation in Spring Design

In the field of compression spring design optimization, engineers face a critical challenge: finding the optimal design parameters that minimize objectives like volume or weight while strictly adhering to complex physical and technical constraints. This process mirrors a fundamental challenge in optimization theory known as the exploration-exploitation dilemma. Exploration involves broadly searching the design space to identify promising regions, while exploitation focuses on intensively refining good solutions to find the optimal configuration [17]. Within the context of a Novel Product Design Optimization Approach (NPDOA), effectively managing this trade-off is paramount for developing superior spring designs with reduced computational effort and enhanced performance characteristics.

The mathematical models governing spring design are typically nonlinear and non-convex, making them resistant to traditional deterministic optimization methods [18]. Metaheuristic algorithms provide a powerful framework for tackling these problems, where the balance between their global search (exploration) and local refinement (exploitation) capabilities directly determines the quality and efficiency of the final spring design [19].

Theoretical Foundation: Exploration vs. Exploitation

Core Definitions and the Optimization Dilemma

In metaheuristic optimization, exploration refers to the algorithm's ability to investigate diverse regions of the search space, thereby avoiding premature convergence to local optima. Conversely, exploitation is the intensive search within the vicinity of known good solutions to refine their quality [19]. The central challenge lies in allocating computational resources between these competing objectives. Excessive exploration leads to inefficient random searching, while overemphasis on exploitation risks trapping the algorithm in suboptimal regions [17].

The No Free Lunch theorem formally establishes that no single metaheuristic algorithm can universally solve all optimization problems optimally [19]. This theoretical foundation justifies the continuous development and specialized application of optimization algorithms like those employed in spring design, where the problem-specific landscape demands tailored balancing strategies.

Manifestation in Spring Design Optimization

For compression spring design, the exploration-exploitation trade-off directly influences critical design parameters:

- Wire diameter (d)

- Mean coil diameter (D)

- Number of active coils (Nc)

These parameters must be optimized while satisfying physical constraints including shear stress limits, buckling conditions, surging frequency, and geometric boundaries dictated by installation space [18]. Effective algorithms must explore different combinations of these parameters globally while exploiting promising regions to achieve precise, manufacturable designs.

Quantitative Analysis of Algorithm Performance in Spring Design

Algorithm Comparison for Volume Minimization

Comprehensive studies have evaluated metaheuristic algorithms for minimizing helical spring volume. The following table summarizes performance metrics for various algorithms applied to this design problem:

Table 1: Performance comparison of metaheuristic algorithms for helical spring volume optimization

| Algorithm | Best Volume (mm³) | Performance vs. Benchmark | Key Strength | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vortex Search (VSA) | 38,918 | 0.54% reduction | Fastest processing time | [18] |

| Particle Swarm (PSO) | 39,021 | 0.30% reduction | Effective constraint handling | [18] |

| Genetic Algorithm (CGA) | 39,083 | 0.15% reduction | Robust exploration | [18] |

| Bees Algorithm (BA) | N/A (Energy Maximized) | Project target exceeded | Successful experimental validation | [20] |

Exploration-Exploitation Strategies in Applied Algorithms

Different algorithms implement distinct mechanisms for balancing the exploration-exploitation trade-off:

- Vortex Search Algorithm (VSA): Utilizes an adaptive Gaussian distribution to transition smoothly from exploration to exploitation, demonstrating superior convergence speed in spring volume minimization [18].

- Bees Algorithm (BA): Implements a population-based search where a subset of "elite sites" receives focused exploitation (recruited bees) while other sites maintain exploration (global scouts), successfully maximizing stored energy in foldable wing mechanisms [20].

- Improved Group Teaching Optimization: Employs specialized binary operators (BTPGG, BTPBG) and opposition-based learning to enhance population diversity and convergence rate simultaneously [21].

- Hybrid Weed-Gravitational (HWGEA): Unifies adaptive seed dispersal (exploration) with gravitational attraction dynamics (exploitation) in a single reproduction mechanism [22].

Experimental Protocols for Spring Design Optimization

General Workflow for Metaheuristic Spring Optimization

Diagram: Spring Design Optimization Workflow

Protocol 1: Volume Minimization of Helical Compression Springs

Objective: Minimize spring volume V = (π/2)²(Nc+2)Dd² subject to physical constraints [18].

Constraints:

- Shear Stress Constraint: g₁ = πd³S - 8CfFmaxD ≥ 0

- Free Length Constraint: g₂ = lmax - lf ≥ 0

- Surging Frequency Constraint: g₃ = f - fn ≥ 0

- Geometric Ratios: 4 ≤ C ≤ 12, where C = D/d

- Deflection Limit: g₄ = lf - δmin ≥ 0

Algorithm-Specific Parameters:

Table 2: Algorithm configuration parameters for spring design optimization

| Algorithm | Population Size | Key Control Parameters | Iterations | Constraint Handling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vortex Search (VSA) | 50 | Initial radius: 0.1, Decay: 0.99 | 1000 | Penalty function method |

| Particle Swarm (PSO) | 50 | w=0.7, c₁=1.5, c₂=1.5 | 1000 | Feasibility preservation |

| Genetic Algorithm (CGA) | 50 | Crossover: 0.8, Mutation: 0.1 | 1000 | Tournament selection |

| Bees Algorithm (BA) | 40 | Elite: 4, Patch: 10, Recruited: 15 | 500 | Direct constraint check |

Procedure:

- Problem Formulation: Define design variables (d, D, Nc), objective function, and constraints based on application requirements.

- Algorithm Initialization: Select appropriate metaheuristic and configure parameters according to Table 2.

- Solution Generation: Initialize population with random feasible designs within variable bounds.

- Iterative Optimization:

- Evaluate objective function and constraints for each candidate.

- Apply algorithm-specific update mechanisms to generate new solutions.

- Implement constraint handling through penalty functions or feasibility rules.

- Decay exploration parameters gradually to shift toward exploitation.

- Termination: Continue until maximum iterations reached or solution improvement stagnates.

- Validation: Verify optimal design using finite element analysis (e.g., Inventor Autodesk) [18].

Protocol 2: Energy Maximization for Mechanism Applications

Objective: Maximize stored energy SE = (d⁴Gxd²)/(16Dm³N) for compression springs [20].

Design Variables:

- Wire diameter (d)

- Mean coiling diameter (Dm)

- Number of coils (N)

- Deflection (xd)

Critical Constraints:

- Safety Factor: SFC = Ssy/Ts ≥ 1.2 (minimum safety margin)

- Geometric Compatibility: Dimensions must fit mechanism housing

- Stress Limits: Maximum allowable shear stress based on material properties

Procedure:

- Energy Objective Setup: Define energy maximization function based on spring geometry and material properties.

- Safety Validation: Calculate safety factors against yielding at solid length.

- Geometric Feasibility: Ensure dimensional compatibility with mechanism constraints.

- Algorithm Execution: Implement population-based optimizer (e.g., Bees Algorithm) with focused local search around high-energy configurations.

- Experimental Verification: Validate optimized design through computational dynamics (e.g., ADAMS program) and physical prototyping [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential resources for spring design optimization research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimization Algorithms | VSA, PSO, CGA, BA, SOA | Navigate complex design spaces to find optimal parameters | Volume minimization, energy maximization [18] [20] |

| Simulation Software | Inventor Autodesk, ABAQUS, ADAMS | Finite element analysis for stress, deformation validation | Verify optimization results physically [18] [20] |

| Material Libraries | Music wire ASTM A228, Composite materials | Define material properties (G, E, Ssy) for accurate modeling | Constraint calculation, performance prediction [20] |

| Benchmark Functions | CEC 2017, CEC 2019 test suites | Algorithm performance validation before application | Ensure optimizer reliability [19] |

| Constraint Handlers | Penalty functions, Feasibility rules | Manage physical limits (stress, geometry) during optimization | Maintain design practicality [18] |

Balancing exploration and exploitation remains a fundamental challenge in compression spring design optimization within the NPDOA framework. The quantitative evidence demonstrates that algorithm selection significantly impacts solution quality, with methods like VSA and BA providing distinct advantages for different design objectives. The experimental protocols outlined herein provide researchers with structured methodologies for implementing these optimization strategies, while the toolkit table offers essential resources for practical application. As metaheuristic algorithms continue to evolve, their ability to intelligently navigate the exploration-exploitation trade-off will increasingly determine success in developing optimal spring designs that meet demanding engineering requirements.

From Theory to Spring Design: Implementing NPDOA for Practical Optimization

Within the broader research on the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) for engineering design, the helical compression spring serves as a quintessential problem for validating metaheuristic approaches. Its design constitutes a well-defined, yet often constrained, nonlinear optimization problem commonly encountered in mechanical systems [5] [23]. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for formally defining the compression spring optimization problem, focusing on the standard design variables, constraints, and objective functions. A precise problem definition is the critical first step for any subsequent computational analysis, including the evaluation of novel algorithms such as the NPDOA [5]. The formulations herein are foundational for research aimed at advancing optimization methodologies in mechanical design.

Mathematical Framework

The optimization of a helical compression spring involves identifying the set of design parameters that extremize an objective function while satisfying a set of mechanical, geometric, and manufacturing constraints.

Standard Design Variables

The design vector, x, for a typical compression spring optimization problem is composed of three primary continuous design variables. These parameters directly define the spring's geometry and performance characteristics [8] [24].

Table 1: Primary Design Variables in Compression Spring Optimization

| Variable Symbol | Description | Typical Units | Design Influence |

|---|---|---|---|

| ( d ) | Wire diameter | mm (or in) | Directly affects stress, stiffness, and fatigue life. |

| ( D_m ) | Mean coil diameter | mm (or in) | Determines spring index (( C = D_m/d )) and space requirements. |

| ( N ) | Number of active coils | Dimensionless | Primarily controls the spring's stiffness and solid height. |

While these three are the most common, some problem formulations may include additional variables such as the free length of the spring (( Lf )) or the total number of coils (( Nt )) [23].

Core Constraints

The feasibility of a spring design is governed by a set of constraints derived from mechanical engineering principles, primarily based on standards and textbooks such as Shigley's Mechanical Engineering Design [8] [24]. These constraints ensure the spring functions safely and reliably within its intended application.

Table 2: Typical Constraints in Compression Spring Optimization

| Constraint Category | Constraint Function | Engineering Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Shear Stress | ( g1(x) = \tau{max} - \tau_{allowable} \leq 0 ) | Prevents yielding or fatigue failure under load. The maximum shear stress (( \tau_{max} )) is calculated considering the Wahl correction factor for curvature and direct shear [24]. |

| Buckling | ( g2(x) = \delta{working} - \delta_{buckling} \leq 0 ) | Ensures the spring does not buckle under compression, which is a function of the slenderness ratio and end conditions. |

| Surge Frequency | ( g3(x) = \omega{excitation} - k \cdot \omega_{natural} \leq 0 ) | Avoids resonance; the first natural frequency of the spring should be 5-10 times greater than the operating frequency of the system [24]. |

| Geometric Limits | ( g4(x) = D{min} - Dm \leq 0 )( g5(x) = Dm - D{max} \leq 0 )( g6(x) = Hs - H_{max} \leq 0 ) | Ensures the spring fits within the allotted space and does not become over-compacted. The solid height (( H_s )) is a critical limit [24]. |

| Manufacturing | ( g7(x) = C{min} - (Dm/d) \leq 0 )( g8(x) = (Dm/d) - C{max} \leq 0 ) | The spring index (( C )) is typically kept between 4 and 12 for manufacturability and to avoid excessive curvature effects [23]. |

The safety factor against yielding is a common way to express the stress constraint, defined as the ratio of the maximum allowable shear stress (( S{sy} )) to the stress at the solid length (( Ts )) [24]: [ SFC = \frac{S{sy}}{Ts} \geq SF{required} ] where ( Ts ) is calculated using the Bergstrasser factor (( K_B )) to account for curvature and direct shear stress [24].

Objective Functions and Optimization Problem Formulation

The objective function defines the goal of the optimization. Different applications necessitate different objectives, which can be single or multi-objective.

Common Objective Functions

Mass or Volume Minimization: A prevalent objective in weight-sensitive applications like aerospace and automotive engineering [23] [24]. Minimizing mass also often reduces material cost. [ \text{Minimize: } f1(x) = \rho \cdot \frac{\pi d^2}{4} \cdot (\pi Dm N_t) ]

Stored Energy Maximization: Critical for applications where the spring acts as an actuator, such as in foldable wing mechanisms or switches, where the goal is to maximize work output [24]. The energy stored in a compression spring is given by: [ \text{Maximize: } f2(x) = SEx = \frac{d^4 G xd^2}{16 Dm^3 N} ] where ( G ) is the shear modulus, and ( xd ) is the deflection.

Fatigue Life Maximization: For springs subjected to cyclic loading, the objective can be to maximize the fatigue life factor or to minimize the probability of failure over a target lifespan [23] [25].

Standardized Problem Statement

The general single-objective optimization problem for a compression spring can be formally stated as:

[ \begin{align} \text{Minimize } & f(x) \ \text{subject to } & g_j(x) \leq 0, \quad j = 1, 2, \dots, m \ & x^L \leq x \leq x^U \end{align} ]

where ( x = [d, Dm, N] ) is the design vector, ( f(x) ) is the objective function, ( gj(x) ) are the constraint functions, and ( x^L ), ( x^U ) are the lower and upper bounds of the design variables, respectively.

Experimental and Validation Protocols

Validating an optimized spring design requires a combination of computational analysis and physical testing. The following workflow outlines the key stages from problem definition to final validation.

Protocol 1: Computational Model Implementation

This protocol details the setup of the mathematical model used for optimization.

4.1.1 Materials/Reagents: Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Relevance |

|---|---|

| MATLAB Optimization Toolbox | Platform for implementing custom optimization algorithms and constraint functions. |

| hcs.m Function [8] | A pre-written MATLAB function for analyzing helical compression spring designs, calculating objectives and constraints based on Shigley's. |

| Finite Element Analysis (FEA) Software (e.g., ANSYS) | For detailed stress, strain, and modal analysis to verify simplified model results post-optimization [24]. |

| FKM Guideline "Analytic Strength Assessment for Springs" | A modern guideline for calculating permissible fatigue strength, used to create updated Goodman diagrams [25]. |

4.1.2 Methodology:

- Code the Analysis Function: Implement a function, such as the referenced

hcs.m[8], that takes the design vector ( x = [d, D_m, N] ) as input. - Define Inputs and Constants: Within the function, define fixed parameters: material properties (shear modulus ( G ), density ( \rho ), allowable stress ( S{sy} )), load requirements (working force ( F ), deflection ( xd )), and geometric limits (minimum/maximum coil diameter, maximum solid height).

- Calculate Intermediate Quantities: Compute the spring index ( C = Dm / d ), the Wahl factor ( Kw = (4C - 1)/(4C - 4) + 0.615/C ), and the shear stress ( \tau = Kw \cdot (8 F Dm)/(\pi d^3) ).

- Compute Objective Function: Calculate the primary objective (e.g., spring mass ( f1(x) ) or stored energy ( f2(x) )).

- Compute Constraint Violations: Evaluate all constraint functions ( g_j(x) ) listed in Table 2. The output should be a vector of constraint values, where a value ≤ 0 indicates the constraint is satisfied.

Protocol 2: Robustness and Industrial Validation

This protocol, inspired by industrial practices [23], assesses the reliability of the optimized design considering real-world uncertainties.

4.2.1 Materials:

- Monte Carlo Simulation Software: For probabilistic analysis.

- Characterized Spring Wire: Material from a single bobbin with reduced variability for small-scale production validation.

- Mass Production Wire: Standard wire with larger tolerances for mass production scenario testing.

4.2.2 Methodology:

- Identify Uncertainty Sources: List all parameters with inherent variability (e.g., wire diameter ( d ) (tolerance: ±0.01mm), mean coil diameter ( D_m ), shear modulus ( G )).

- Define Probability Distributions: Assign appropriate statistical distributions (e.g., Normal, Uniform) to each uncertain parameter based on manufacturing data or standards.

- Run Monte Carlo Simulations: Generate a large number (e.g., 10,000) of spring designs by randomly sampling from the defined distributions. Analyze each sample design using the computational model from Protocol 1.

- Calculate Success Probability: Estimate the probability of success (( pc )) as the fraction of sample designs that satisfy all constraints. An industrially robust design should have a ( pc ) very close to 100% [23].

- Compare with Industry Standard: Benchmark the performance (e.g., success probability, mass) of the optimized design against solutions generated by industry-standard software to demonstrate superiority [23].

Protocol 3: Experimental Fatigue Validation

This protocol validates the fatigue life of the optimized design, addressing a key functional requirement [25].

4.3.1 Materials:

- Spring Fatigue Testing Rig: A machine capable of applying cyclic compressive loads at a defined frequency and amplitude.

- Optimized Spring Prototypes: A batch of at least 30 springs fabricated according to the final optimized dimensions.

- Data Acquisition System: To record the number of cycles to failure for each test specimen.

4.2.2 Methodology:

- Define Test Profile: Based on the application, define the minimum and maximum load (or deflection) for the fatigue cycle, and the test frequency.

- Mount Specimen: Install a spring prototype into the testing rig.

- Apply Cyclic Loading: Start the test and apply the cyclic load until the spring fails (e.g., fracture) or reaches a predetermined run-out number of cycles (e.g., 10^7 cycles).

- Record Data: For each tested spring, record the number of cycles sustained before failure.

- Analyze Data: Plot an S-N curve (stress amplitude vs. cycles to failure) using the collected data. Compare the experimental data points with the predicted Goodman diagram based on the new FKM guideline for springs [25] to validate the analytical fatigue strength calculation method.

Integration with Advanced Optimization Algorithms

The defined problem serves as an excellent benchmark for metaheuristic algorithms like the NPDOA. The following diagram illustrates the logical interaction between a population-based algorithm and the spring problem definition.

The performance of novel algorithms like NPDOA can be quantitatively compared against other recently proposed metaheuristics, such as the Power Method Algorithm (PMA) [5] or the Crossover strategy integrated Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (CSBOA) [7], using the well-defined objectives and constraints of the spring problem. Success is measured by the algorithm's ability to consistently and efficiently locate the global optimum design that satisfies all constraints, demonstrating a superior balance of exploration and exploitation [5].

Within the framework of a broader thesis on a New Product Development and Optimization Approach (NPDOA) for compression spring design, the precise formulation of the objective function is a critical determinant of research outcomes. This function quantitatively defines the optimal compromise between two competing primary objectives: maximizing force output and minimizing mechanical stress [26] [27]. For researchers and scientists, particularly those applying rigorous design principles to domains like specialized medical device development, a meticulously crafted objective function ensures that final designs are not only high-performing but also reliable and safe. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols to guide this essential process, integrating mathematical modeling with practical validation protocols.

Theoretical Foundation and Key Parameters

Fundamental Force and Stress Relationships

The mechanical behavior of helical compression springs is governed by well-established physical laws and geometric relationships. The fundamental force-displacement relationship is described by Hooke's Law, which states that the force (F) exerted by a spring is directly proportional to its deflection (x) from its free length, with the spring rate (k) as the constant of proportionality: F = k * x [28] [27].

The spring rate (stiffness) itself is a function of the spring's geometry and material properties, calculated as:

k = (G * dwire⁴) / (8 * Dcoil³ * N_a) [26] [29]

Where:

- G = Shear modulus of the material (psi or Pa)

- d_wire = Wire diameter (in or m)

- D_coil = Mean coil diameter (in or m)

- N_a = Number of active coils

Concurrently, the shear stress incurred in the wire must be calculated. The primary stress arises from torsional loading, and the Wahl correction factor (Kw) is often applied to account for curvature and direct shear stress [26] [30]. The maximum shear stress (τmax) is given by:

τmax = Kw * (8 * F * Dcoil) / (π * dwire³) [26]

Quantitative Design Parameters and Constraints

The table below summarizes the key variables involved in formulating the objective function for compression spring design optimization.

Table 1: Key Variables in Spring Design Optimization

| Variable Name | Symbol | Description | Typical Constraints |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wire Diameter | d_wire |

Diameter of the spring wire [31] | Lower and upper manufacturing bounds [26] |

| Coil Diameter | D_coil |

Mean diameter of the spring coil [31] | D_coil / d_wire ≥ 4 and ≤ 16 (Spring Index) [26] [32] |

| Free Length | L_free |

Length of unloaded spring [31] | Must accommodate deflection [26] |

| Active Coils | N_a |

Number of coils contributing to deflection [31] | Impacts solid height and rate [26] |

| Solid Height | L_solid |

Length when coils are fully compressed [31] | L_def - L_solid > 0.05 (safety margin) [26] |

| Slenderness Ratio | λ |

L_free / D_coil [31] |

λ < 4 (to avoid buckling) [31] [32] |

| Force at Preload | F |

Output force at operating height [26] | Objective to maximize [26] |

| Shear Stress | τ |

Stress in the wire material [31] | τ < S_y / S_f (yield strength / safety factor) [26] |

Protocol 1: Formulating the Single and Multi-Objective Functions

Experimental Workflow for Objective Function Development

The following protocol outlines the systematic process for defining the objective function, from initial single-objective formulation to complex multi-objective optimization.

Figure 1: Workflow for formulating single and multi-objective optimization functions for compression spring design.

Procedure

- Define Design Variables and Parameters: Initiate the process by declaring the independent design variables, typically including wire diameter (

d_wire), coil diameter (D_coil), number of active coils (N_a), and free length (L_free) [26] [31]. These form the vector x over which the optimization is performed. - Establish Analysis Functions: Create mathematical functions that compute dependent quantities of interest. The two most critical are the force (

F) and the maximum shear stress (τ_max), as derived in Section 2.1 [26]. - Formulate a Single-Objective Function: For initial studies, a single-objective approach is practical. The goal is to maximize the force at the preload height (

h_0). This is framed as a minimization problem for solver compatibility: > Minimize:f(x) = -F(x)> Subject to:g_i(x) ≤ 0(e.g.,τ_max < S_y / S_f) [26] - Formulate a Multi-Objective Function: For a balanced NPDOA, a multi-objective function is essential. The weighted sum method is a robust starting point, combining the two competing objectives:

> Minimize:

f(x) = -W₁ * F(x) + W₂ * τ_max(x)> Subject to:g_i(x) ≤ 0Here,W₁andW₂are weighting coefficients that reflect the relative importance of force versus stress minimization in the specific application. Their sum is typically normalized to 1. - Define Constraints: Implement all relevant physical and manufacturing constraints as inequality constraints

g_i(x) ≤ 0. Key constraints from Table 1 must be included, such as stress limits, spring index bounds, slenderness ratio for buckling, and a safe margin between the deflected height and solid height [26] [31] [32].

Protocol 2: Computational Implementation and Solver Setup

Experimental Workflow for Computational Optimization

This protocol details the steps for implementing the formulated objective function within a computational environment and configuring the optimization solver.

Figure 2: Computational implementation and solver setup workflow for compression spring optimization.

Procedure

- Code the Model: Implement the objective and constraint functions from Protocol 1 in a computational environment (e.g., Python with GEKKO [26], MATLAB [8]). Ensure all intermediate calculations (spring rate

k, Wahl factorK_w, solid heightL_solid) are correctly coded. - Select an Optimization Algorithm:

- For smooth, continuous problems, gradient-based algorithms (e.g., SQP, interior-point) are efficient [26].

- For problems with discontinuous or noisy functions, or to better explore the global design space, metaheuristic algorithms are advantageous (e.g., Secretary Bird Optimization Algorithm (CSBOA) [7], Genetic Algorithms [7]).

- Configure the Solver: Set solver-specific parameters such as convergence tolerance, maximum number of iterations, and any algorithm-specific controls. For metaheuristics, parameters include population size and mutation rates [7].

- Run the Optimization: Execute the solver from multiple initial starting points within the design space to mitigate the risk of converging to a local, rather than global, optimum [26] [7].

- Validate and Analyze Results: Verify that the optimal solution satisfies all constraints. Identify "binding" constraints (those equal to zero at the optimum) as they govern the design limits. Analyze the sensitivity of the solution to changes in the weighting coefficients

W₁andW₂in the objective function.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table catalogues essential computational and mathematical "reagents" required for executing the described optimization protocols.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Spring Design Optimization

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Optimization Protocol | Exemplars & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization Solver Software | Core computational engine for minimizing the objective function subject to constraints. | GEKKO (Python) [citation:], MATLAB Optimization Toolbox [8], Open Design Optimization Platform (ODOP) [31]. |

| Metaheuristic Algorithms | Advanced solvers for global optimization, especially useful for complex, non-convex problems. | Secretary Bird Optimization (CSBOA) [7], Genetic Algorithms [7], Particle Swarm Optimization [7]. |

| Material Property Database | Provides essential input parameters (G, S_y, Q) for stress and force calculations. | Must include shear modulus (G), yield strength (S_y), and fatigue properties [26] [29]. |

| Geometric Constraint Library | Pre-defined functions for common design limits (spring index, slenderness). | Ensures manufacturability and prevents buckling [31] [32]. |

| Sensitivity Analysis Toolkit | Quantifies the impact of changes in design variables and weights on the objective function. | Used for robustness analysis and refining the NPDOA. |

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Results from Reference Model

The following table synthesizes key output metrics and optimal design variable values from a referenced spring design optimization model, providing a benchmark for expected results.

Table 3: Exemplar Optimization Results from a Force Maximization Problem

| Parameter Category | Variable Name | Exemplar Optimal Value | Status in Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Objective Function | Force (F) | Maximized Value | Primary Objective |

| Design Variables | Wire Diameter (d_wire) |

~0.072 inches | At or between bounds |

Coil Diameter (d_coil) |

~0.678 inches | Critical for force/stress balance | |

Number of Coils (n_coils) |

~7.59 | Impacts spring rate and solid height | |

Free Length (h_f) |

~1.37 inches | Determined by operational travel | |

| Key Constraints | Stress at Solid Height | τ_hs < S_y / S_f |

Binding/Limiting Constraint [26] |

Spring Index (D_coil/d_wire) |

Maintained between 4 and 16 | Active Constraint [26] | |

| Deflection to Solid Margin | h_def - h_s > 0.05 inches |

Safety Constraint [26] |

Visualization of the Optimization Logic Structure

The underlying logic of the objective function and its interaction with constraints can be visualized as a network of dependencies, which is crucial for debugging and understanding the design space.

Figure 3: Logical relationship between design variables, analysis functions, constraints, and the final objective function in a compression spring design optimization problem.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Encoding the Spring Problem for NPDOA

The compression spring design problem represents a classic challenge in engineering optimization, characterized by multiple nonlinear constraints and mixed-type variables. This Application Note provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for encoding this problem within the framework of the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA), a novel brain-inspired metaheuristic. NPDOA simulates the decision-making processes of neural populations in the brain through three core strategies: attractor trending for exploitation, coupling disturbance for exploration, and information projection to balance these phases [14]. Framed within broader thesis research on NPDOA for compression spring design, this guide enables researchers in computational intelligence and engineering design to effectively apply this advanced optimizer.

The Compression Spring Design Problem

The objective is to design a compression spring that minimizes its weight while satisfying performance constraints related to shear stress, deflection, and surge frequency [26]. The design must account for conflicting requirements: a smaller wire diameter reduces weight but may increase stress levels, while a larger coil diameter can improve performance but adds to the overall weight and size.

Mathematical Formulation

The standard formulation involves three primary design variables and several nonlinear constraints [26]:

Design Variables:

- Wire diameter ((d))

- Mean coil diameter ((D))

- Number of active coils ((N))

Objective Function:

- Minimize weight ( f(\mathbf{x}) = \frac{\pi^2 D d^2 (N+2)}{4} )

Key Constraints:

- Shear stress constraint: ( \tau \leq \tau_{\text{max}} )

- Deflection constraint: ( \delta \leq \delta_{\text{max}} )

- Surge frequency constraint: ( f \geq f_{\text{min}} )

- Diameter ratio constraint: ( \frac{D}{d} \geq C_{\text{min}} )

Table 1: Design Variables and Their Boundaries

| Variable | Symbol | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wire diameter (cm) | (d) | 0.05 | 1.0 |

| Mean coil diameter (cm) | (D) | 0.25 | 1.3 |

| Number of active coils | (N) | 2 | 15 |

Table 2: Constraint Definitions for the Spring Problem

| Constraint | Formula | Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| Shear stress | ( \tau = \frac{8PD}{\pi d^3} ) | ( \tau \leq \tau_{\text{max}} ) |

| Deflection | ( \delta = \frac{8PD^3N}{Gd^4} ) | ( \delta \leq \delta_{\text{max}} ) |

| Surge frequency | ( f = \frac{d}{2\pi D^2 N} \sqrt{\frac{G}{2\rho}} ) | ( f \geq f_{\text{min}} ) |

| Diameter ratio | ( C = \frac{D}{d} ) | ( C{\text{min}} \leq C \leq C{\text{max}} ) |

NPDOA Fundamentals for Spring Encoding

NPDOA treats each potential spring design as a neural population state, where design variables correspond to neuronal firing rates [14]. The algorithm's neurodynamic principles provide a robust search mechanism for the complex spring design space.

Neural Population Dynamics Framework

- Solution Representation: Each neural population ( \mathbf{X}i = (x{i1}, x{i2}, ..., x{iD}) ) encodes a spring design, where (D=3) represents the decision variables (d), (D), and (N) [14]

- Neural State Interpretation: The firing rate of each neuron corresponds to the normalized value of a design variable

- Population Doctrine: Multiple neural populations explore the design space concurrently, simulating parallel decision-making in brain circuits [14]

Core NPDOA Strategies

The algorithm employs three brain-inspired strategies that must be adapted for the spring problem:

- Attractor Trending Strategy: Drives neural populations toward locally optimal spring designs, ensuring exploitation [14]

- Coupling Disturbance Strategy: Introduces deviations from attractors through neural coupling, maintaining exploration [14]

- Information Projection Strategy: Controls communication between neural populations, regulating the transition between exploration and exploitation [14]

Encoding Protocol for Spring Design

Solution Representation and Initialization

Diagram 1: Solution encoding workflow

Step 1: Parameter Normalization

- Normalize each design variable to a [0,1] scale using: ( d{\text{norm}} = \frac{d - d{\min}}{d{\max} - d{\min}} )

- Repeat for (D) and (N) to create a normalized solution vector

Step 2: Neural Population Initialization

- Initialize (NP) neural populations using random sampling within bounds: ( \mathbf{X}_i = \mathbf{L} + \text{rand}(0,1) \cdot (\mathbf{U} - \mathbf{L}) ) where (\mathbf{L}) and (\mathbf{U}) are lower and upper bounds

Step 3: Fitness Evaluation

- Decode each neural population to physical parameters

- Calculate constraint violations using penalty approaches

- Compute fitness: ( F(\mathbf{X}i) = f(\mathbf{X}i) + \sum \lambdaj \cdot \max(0, gj(\mathbf{X}_i)) )

NPDOA-Specific Implementation

Diagram 2: NPDOA optimization cycle

Step 4: Attractor Trending Implementation

- Identify attractor states (local best positions) for each neural population

- Update neural states toward attractors: ( \mathbf{X}i^{\text{new}} = \mathbf{X}i + \alpha \cdot (\mathbf{A}i - \mathbf{X}i) ) where (\alpha) controls exploitation strength and (\mathbf{A}_i) is the attractor

Step 5: Coupling Disturbance Application

- Randomly select distinct neural populations (p) and (q)

- Apply disturbance: ( \mathbf{X}i^{\text{dist}} = \mathbf{X}i + \beta \cdot (\mathbf{X}p - \mathbf{X}q) ) where (\beta) controls exploration magnitude

Step 6: Information Projection Control

- Regulate strategy application based on iteration count: ( \gamma(t) = \gamma{\max} - (\gamma{\max} - \gamma{\min}) \cdot \frac{t}{T{\max}} ) where (\gamma) balances exploration-exploitation over iterations

Constraint Handling and Termination

Step 7: Feasibility-Based Selection

- Prioritize feasible solutions over infeasible ones

- Among infeasible solutions, select those with smaller constraint violations

- Use tournament selection with feasibility rules

Step 8: Termination Criteria

- Maximum iterations: (T_{\max} = 1000)

- Stall detection: No improvement for 100 iterations

- Tolerance achievement: ( |f{best}(t) - f{best}(t-10)| < 10^{-6} )

Experimental Protocol and Validation

Parameter Configuration

Table 3: NPDOA Parameters for Spring Design

| Parameter | Symbol | Recommended Value | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population size | (NP) | 50 | Number of neural populations |

| Attractor strength | (\alpha) | 0.5 | Controls exploitation intensity |

| Coupling factor | (\beta) | 0.3 | Regulates exploration magnitude |

| Information rate | (\gamma) | 0.8→0.2 | Balances exploration-exploitation transition |

| Maximum iterations | (T_{\max}) | 1000 | Termination criterion |

Performance Metrics

- Solution Quality: Best objective value obtained

- Convergence Rate: Iterations to reach within 1% of best-known solution