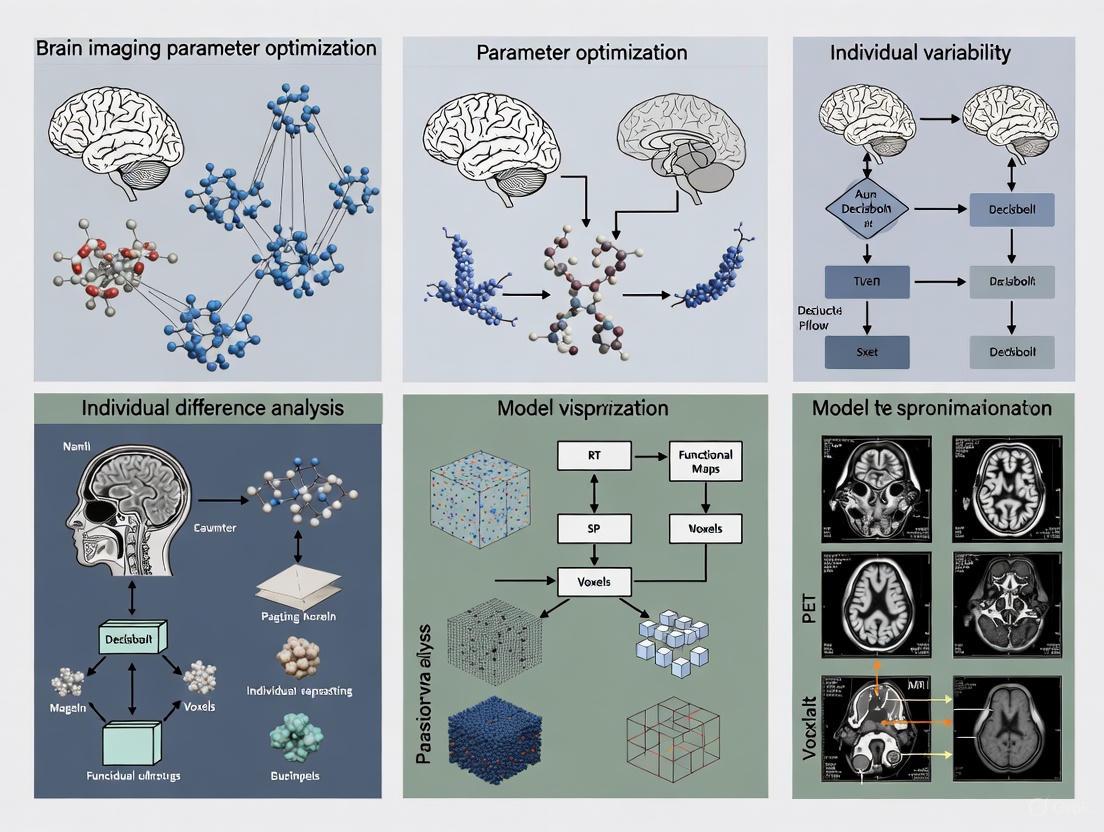

Optimizing Brain Imaging Parameters for Individual Differences: From Acquisition to Personalized Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive framework for optimizing brain imaging parameters to better capture and interpret individual differences in neuroscience research and clinical applications.

Optimizing Brain Imaging Parameters for Individual Differences: From Acquisition to Personalized Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for optimizing brain imaging parameters to better capture and interpret individual differences in neuroscience research and clinical applications. It explores the foundational need to move beyond group-level analyses, details methodological advances in fMRI and DTI that enhance effect sizes, and presents systematic strategies for optimizing preprocessing pipelines to improve reliability and statistical power. Furthermore, it evaluates validation frameworks and comparative performance of analytical models. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current best practices and emerging trends, including AI integration, to guide the development of more robust, reproducible, and individually sensitive neuroimaging protocols.

Why One-Size-Fits-All Fails: The Imperative for Individualized Neuroimaging

The Challenge of Effect Sizes and Reliability in Individual Differences Research

FAQs on Effect Shes and Reliability

What is the "reliability paradox" in individual differences research? The reliability paradox describes a common situation in cognitive sciences where measurement tools that robustly produce within-group effects (e.g., a task that consistently shows an effect in a group of participants) tend to have low test-retest reliability. This low reliability makes the same tools unsuitable for studying differences between individuals [1] [2]. At its core, this happens because creating a strong within-group effect often involves minimizing the natural variability between subjects, which is the very same variability that individual differences research seeks to measure reliably [2].

Does poor measurement reliability only affect individual differences studies? No, this is a common misconception. Poor measurement reliability attenuates (weakens) observed group differences as well [1] [2]. Some studies have erroneously suggested that reliability is only a concern for correlational studies of individuals, but both group and individual differences are affected because they both rely on the dimension of between-subject variability. When measurement reliability is low, the observed effect sizes in group comparisons (e.g., patient vs. control) are smaller than the true effect sizes in the population [2].

How does reliability affect the observed effect size in my experiments? Measurement reliability directly attenuates the observed effect size in your data. The following table summarizes how the true effect size is reduced to the observed effect size based on reliability [2].

| True Effect Size (d_true) | Reliability (ICC) | Observed Effect Size (d_obs) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.76 |

| 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.67 |

| 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.57 |

| 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.44 |

Formula: ( d_{obs} = d_{true} \times \sqrt{ICC} )

What are the implications for statistical power and sample size? Low reliability drastically increases the sample size required to achieve sufficient statistical power. As reliability decreases, the observed effect size becomes smaller, and you need a much larger sample to detect that smaller effect [2].

| Target Effect Size (d) | Reliability (ICC) | Observed Effect Size (d_obs) | Sample Size Needed for 80% Power |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.76 | 56 |

| 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.67 | 71 |

| 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.57 | 98 |

| 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.44 | 162 |

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Poor Reliability

This workflow provides a systematic approach for diagnosing and resolving reliability issues in your research data [3] [4].

Step 1: Identify the Problem Define the specific nature of the reliability issue. Is it low test-retest reliability (ICC) for a behavioral task, or high variability in neuroimaging parameters? Review your data to confirm the signal is much noisier than expected [3] [4].

Step 2: Repeat the Experiment Before making any changes, simply repeat the experiment if it's not cost or time-prohibitive. This helps determine if the problem was a one-time mistake (e.g., incorrect reagent volume, extra wash steps) or a consistent, systematic issue [3].

Step 3: Verify with Controls Ensure you have the appropriate positive and negative controls in place. For example, if a neural signal is dim, include a control that uses a protein known to be highly expressed in the tissue. If the control also fails, the problem likely lies with the protocol or equipment [3].

Step 4: Check Equipment & Materials Inspect all reagents, software, and hardware. Molecular biology reagents can be sensitive to improper storage (e.g., temperature). In neuroimaging, ensure all system parameters and analysis software versions are correct and compatible [3].

Step 5: Change One Variable at a Time Generate a list of variables that could be causing the low reliability (e.g., fixation time, antibody concentration, analysis parameters). Systematically change only one variable at a time to isolate the root cause [3] [4]. For parameter optimization in neural decoding, consider using an automated framework like NEDECO, which can efficiently search complex parameter spaces [5].

Step 6: Document Everything Keep detailed notes in your lab notebook of every change made and the corresponding outcome. This creates a valuable record for your future self and your colleagues [3] [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Category | Item | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Analysis | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) | Quantifies test-retest reliability of a measure by partitioning between-subject and error variance [2]. |

| Statistical Analysis | Cohen's d* | An effect size metric for group comparisons that does not assume equal variances between groups [2]. |

| Software & Tools | NEDECO (NEural DEcoding COnfiguration) | An automated parameter optimization framework for neural decoding systems that can improve accuracy and time-efficiency [5]. |

| Software & Tools | Data Color Picker / Viz Palette | Tools for selecting accessible color palettes for data visualization, crucial for highlighting results without distorting meaning [6]. |

| Methodological Framework | Brain Tissue Phantom with Engineered Cells | An in vitro assay for modeling in vivo optical conditions to optimize imaging parameters for deep-brain bioluminescence activity imaging before animal experiments [7]. |

| 3-hydroxy-2-(pyridin-4-yl)-1H-inden-1-one | 3-hydroxy-2-(pyridin-4-yl)-1H-inden-1-one|CAS 67592-40-9 | |

| Thallium(III) bromide | Thallium(III) Bromide | High Purity | For Research | High-purity Thallium(III) Bromide for materials science and chemical synthesis research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is my fMRI analysis producing unexpectedly high false positive rates?

A high false positive rate is often traced to the statistical method used for cluster-level inference [8]. A 2016 study found that one common method, when based on Gaussian random field theory, could yield false positive rates up to 70% instead of the assumed 5% [8]. This issue affected software packages including AFNI (which contained a bug, since fixed in 2015), FSL, and SPM [8].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Software Version: Confirm you are using an AFNI version updated after 2015 [8].

- Use Non-Parametric Methods: Switch to non-parametric inference methods, such as permutation testing, which were validated as a robust alternative in the Eklund et al. study [8].

- Check Your Data: Use the open data from the Eklund et al. paper to validate your analysis pipeline.

Q2: Our research focuses on individual differences, but we are struggling with low effect sizes. What strategies can we employ?

Optimizing effect sizes is crucial for robust individual differences research, potentially reducing the required sample size from thousands to hundreds [9]. The following table summarizes four core strategies.

Table: Strategies for Optimizing Effect Sizes in Individual Differences Neuroimaging Research

| Strategy | Core Principle | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Matching [9] | Maximize the association between the neuroimaging task and the behavioral construct. | Select a response inhibition task that is a strong phenotypic marker for the specific impulsivity trait you are studying. |

| Increase Measurement Reliability [9] | Improve the reliability of both neural and behavioral measures to reduce noise. | Use multiple runs of a task and aggregate data to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio for neural measurements [9]. |

| Individualization [9] | Tailor stimuli or analysis to individual participants' characteristics. | Adjust the difficulty of a cognitive task in real-time based on individual performance to ensure optimal engagement. |

| Multivariate Cross-Validation [9] | Use multivariate models with cross-validation instead of univariate mass-testing. | Employ a predictive model with cross-validation to assess how well a pattern of brain activity predicts a trait, rather than testing each voxel individually. |

Q3: How should we organize our neuroimaging dataset to ensure compatibility with modern analysis pipelines and promote reproducibility?

Adopt the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) standard [10]. BIDS provides a simple and human-readable way to organize data, which is critical for machine readability, pipeline interoperability, and reproducibility.

- Solution Steps:

- Follow the Structure: Organize your data with a main project directory and subdirectories for each participant (e.g.,

sub-control01). Within these, create modality-specific folders likeanat,func,dwi, andfmap[10]. - Use Standardized Naming: Name files consistently to include key entities like subject ID, session, task, and modality (e.g.,

sub-control01_task-nback_bold.nii.gz) [10]. - Include Sidecar Files: Provide accompanying

.jsonfiles for each data file to store critical metadata about acquisition parameters [10].

- Follow the Structure: Organize your data with a main project directory and subdirectories for each participant (e.g.,

Q4: What are the best practices for sharing data and analysis code to ensure the reproducibility of our findings?

The OHBM Committee on Best Practices (COBIDAS) provides detailed recommendations [11].

- Actionable Checklist:

- Share Multiple Data Forms: Where feasible, share data in multiple states – from raw (DICOM) to preprocessed, to enable different types of reanalysis [11].

- Report Transparently: Document and report all aspects of your study, including researcher degrees of freedom and analytical paths that were attempted but not successful [11].

- Share Analysis Code: Publish the exact code and parameters used for your analysis to enable "computational reproducibility," where others can re-run your analysis on the same data [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Software Tools for Neuroimaging Personalization Research

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Relevance to Personalization |

|---|---|---|

| Nibabel [10] | Reading/Writing Neuroimaging Data | Foundational library for data access; essential for all custom analysis pipelines. |

| Nilearn / BrainIAK [10] | Machine Learning for fMRI | Implements multivariate approaches and cross-validation, key for optimizing effect sizes [9]. |

| DIPY [10] | Diffusion MRI Analysis | Enables analysis of white matter microstructure and structural connectivity, a core component of individual differences. |

| Nipype [10] | Pipeline Integration | Allows creation of reproducible workflows that combine tools from different software packages (e.g., FSL, AFNI, FreeSurfer). |

| AFNI, FSL, SPM [12] | fMRI Data Analysis | Standard tools for univariate GLM analysis; require careful configuration to control false positives [8]. |

| BIDS Validator | Data Standardization | Ensures your dataset is compliant with the BIDS standard, facilitating data sharing and pipeline use [10]. |

| 1,5-Dimethyl-3-phenylpyrazole | 1,5-Dimethyl-3-phenylpyrazole, CAS:10250-60-9, MF:C11H12N2, MW:172.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2H-Azepin-2-one, hexahydro-1-(2-propenyl)- | 2H-Azepin-2-one, hexahydro-1-(2-propenyl)-, CAS:17356-28-4, MF:C9H15NO, MW:153.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Reproducible fMRI Analysis Pipeline with Nipype

This protocol outlines a robust workflow for task-based fMRI analysis, integrating quality control and best practices for statistical inference.

Protocol 2: Optimization of Effect Sizes for Individual Differences

This methodology details the steps for designing a study to maximize the detectability of brain-behavior relationships.

Linking Neural Circuit Variability to Behavior and Clinical Phenotypes

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: Addressing Key Methodological Hurdles

1. How can I distinguish true neural signal from noise when studying individual variability? Historically, neural variability was dismissed as noise, but it is now recognized as a meaningful biological signal. To distinguish signal from noise:

- Employ Precision Functional Mapping: Collect extensive data from individual participants (e.g., 10 hours per subject) to create reliable individual-specific brain maps, as this can reveal unique networks common across some, but not all, people [13].

- Leverage Task-Based Paradigms: Study variability within disorder-relevant tasks, as moment-to-moment neural fluctuations are a crucial substrate for cognition and can be a biomarker for psychiatric conditions [14].

- Utilize Longitudinal Designs: Track individuals over time to establish stable, trait-like neural patterns versus state-dependent variations [14].

2. What is the best approach for linking a specific neural circuit perturbation to a behavioral change? Establishing a causal relationship requires more than just observing correlation.

- Multi-Paradigm Validation: Avoid relying on a single behavioral test. Use additional paradigms or procedures to support your initial data interpretation. For example, if using an automated lever-press task, also record behavior with a webcam to qualitatively assess factors like motor behavior, arousal, or exploration that the automated system might miss [15].

- Precise Circuit Manipulation: Use interventional tools like optogenetics, chemogenetics, or deep brain stimulation (DBS) to change neural circuit dynamics and observe subsequent behavioral effects [16]. For DBS, develop algorithms to individually "tune" stimulation parameters (site, intensity, timing) for each patient's specific brain circuit response [13].

- Describe Behavior Precisely: Report observed behaviors in precise terms separate from speculation. Overgeneralization of conclusions is a common pitfall [15].

3. My brain imaging data shows inconsistent results across subjects. How can I account for high individual variability? Individual variability is a feature, not a bug, of brain organization.

- Shift from Group-Averages to Individual-Focus: Group-averaged data can mask important individual differences in brain structure and function. Use precision brain imaging to map structure, function, and connectivity in single individuals [13].

- Identify Individual Networks: Recognize that some functional brain networks are common across people, while others are unique to single individuals. These unique networks may underlie behavioral variability [13].

- Control Technical Factors: In MRI, technical factors like field-of-view (FOV) phase and phase oversampling significantly impact scan time and consistency. Optimizing these parameters is crucial for reproducible data [17].

4. How can I optimize brain imaging parameters to balance scan time, resolution, and patient comfort? Technical optimization is key for quality data.

- Adjust Specific MRI Parameters: Research shows that altering the FOV phase and phase oversampling can significantly reduce scan time without necessarily compromising spatial resolution. For example, one study reduced scan time from 3.47 minutes to 2.18 minutes by optimizing these parameters [17].

- Ensure Proper Patient Positioning: Use head holders and secure the patient's head with chin and head straps. Position the canthomeatal line (from the outer eye corner to the ear canal) vertically perpendicular to the imaging table to standardize orientation and reduce motion artifacts [18].

- Follow Radiopharmaceutical Protocols: For molecular brain imaging (SPECT/PET), strictly adhere to the injection and acquisition parameters in the package insert to ensure consistent and interpretable results [18].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Precision Functional Mapping for Individual Brain Network Identification

Objective: To create high-resolution maps of functional brain organization unique to individual participants [13].

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Acquire high-resolution functional MRI (fMRI) data from individual participants. A typical protocol involves collecting approximately 10 hours of scanning data per subject to achieve sufficient signal-to-noise [13].

- Preprocessing: Standard fMRI preprocessing steps (motion correction, normalization, etc.) should be applied.

- Individual Network Analysis: Analyze the fMRI time-series data to identify functional networks within each individual's brain without relying on group-averaged templates. This can reveal:

- Common Networks: Networks that appear across many individuals.

- Unique Networks: Networks that are specific to a single individual, which may explain unique behavioral traits [13].

- Validation: Correlate the identified individual-specific network configurations with behavioral measures.

Protocol 2: Linking Genetic Risk to Neural Circuitry and Behavior in Adolescents

Objective: To investigate how polygenic risk for behavioral traits (BIS/BAS) influences striatal structure and emotional symptoms [19].

Procedure:

- Participant Cohort: Utilize a large-scale dataset like the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study, which includes children around 9-11 years old [19].

- Genotyping & Polygenic Risk Score (PRS) Calculation:

- Perform genome-wide association studies (GWAS) on Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) and Behavioral Activation System (BAS) traits in a discovery sample.

- Calculate PRS for each participant in the target sample using the GWAS summary statistics, representing their genetic predisposition for these traits [19].

- Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI) Processing:

- Preprocess DWI data to correct for distortions, eddy currents, and head motion.

- Use probabilistic tractography (e.g., with FSL's

probtrackx2) to model the structural connectivity between the striatum and cortical regions [19].

- Striatal Structural Gradient (SSG) Analysis: Compute a low-dimensional representation (gradient) of the striatal connectivity matrix to summarize its macroscale anatomical organization [19].

- Statistical Modeling: Test the association between BIS/BAS PRS, the SSG, and symptoms of anxiety and depression using mediation analysis to see if striatal structure mediates the genetic effect on emotion [19].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of MRI Parameter Adjustments on Scan Time

This table summarizes quantitative findings from a study investigating how technical factors in MRI affect acquisition time, essential for designing efficient and comfortable imaging protocols [17].

| Technical Factor | Original Protocol Value | Optimized Protocol Value | Effect on Scan Time | Statistical Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field-of-View (FOV) | 230 mm | 217 mm | No direct significant effect | p = 0.716 |

| FOV Phase | 90% | 93.88% | Significant reduction | p < 0.001 |

| Phase Oversampling | 0% | 13.96% | Significant reduction | p < 0.001 |

| Cross-talk | Not specified | 38.79 (avg) | No significant effect | p = 0.215 |

| Total Scan Time | 3.47 minutes | 2.18 minutes | ~37% reduction | N/A |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Neural Circuit Analysis

This table lists key tools and reagents used in modern circuit mapping and manipulation, illustrating the interdisciplinary nature of the field [16] [20] [15].

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viral Tracers (e.g., AAVs, Lentiviruses) | Circuit Tracing | Identify efferent (anterograde) and afferent (retrograde) connections of specific neuronal populations [20]. | High selectivity; can be genetically targeted to cell types. |

| Conventional Tracers (e.g., CTB, Fluorogold) | Circuit Tracing | Map neural pathways via anterograde or retrograde axonal transport. Compatible with light microscopy [20]. | Well-established; less complex than viral tools but offer less genetic specificity. |

| Optogenetics Tools (e.g., Channelrhodopsin) | Circuit Manipulation | Precisely activate or inhibit specific neural populations with light to test causal roles in behavior [16] [15]. | Requires genetic access and light delivery; provides millisecond-scale temporal precision. |

| Chemogenetics Tools (e.g., DREADDs) | Circuit Manipulation | Remotely modulate neural activity in specific cells using administered designer drugs [16] [15]. | Less temporally precise than optogenetics but does not require implanted hardware. |

| Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) | Circuit Manipulation | Electrical stimulation of brain areas to modulate circuit function, often for therapeutic purposes [13]. | New algorithms can individualize stimulation parameters for better outcomes. |

Methodological Visualizations

Diagram 1: Neural Circuit Investigation Workflow

Diagram 2: Precision Imaging vs. Group-Average Paradigm

FAQs: Understanding Inter-Subject Variability

1. What is inter-subject variability in brain imaging and why should we treat it as data rather than noise? Inter-subject variability refers to the natural differences in brain anatomy and function between individuals. Rather than treating this variance as measurement noise, modern neuroscience recognizes it as scientifically and clinically valuable data. This variability is the natural output of a noisy, plastic system (the brain) where each subject embodies a particular parameterization of that system. Understanding this variability helps reveal different cognitive strategies, predict recovery capacity after brain damage, and explain wide differences in human abilities and disabilities [21].

2. What are the main anatomical sources of inter-subject variability? The main structural and physiological parameters that govern individual-specific brain parameterization include: grey matter density, cortical thickness, morphological anatomy, white matter circuitry (tracts and pathways), myelination, callosal topography, functional connectivity, brain oscillations and rhythms, metabolism, vasculature, and neurotransmitters [21].

3. Does functional variability increase further from primary sensory regions? Contrary to what might be expected, evidence suggests that inter-subject anatomical variability does not necessarily increase with distance from neural periphery. Studies of primary visual, somatosensory, motor cortices, and higher-order language areas have shown consistent anatomical variability across these regions [22].

4. How does cognitive strategy contribute to functional variability? Different subjects may employ different cognitive strategies to perform the same task, engaging distinct neural pathways. For example, in reading tasks, subjects may emphasize semantic versus nonsemantic reading strategies, activating different frontal cortex regions. This "degeneracy" (where the same task can be performed in multiple ways) is a dominant source of intersubject variability [21] [23].

5. What are the key methodological challenges in measuring individual differences? The main challenge involves distinguishing true between-subject differences from within-subject variation. The brain is a dynamic system, and any single measurement captures only a snapshot of brain function at a given moment. Sources of variation exist across multiple time scales - from moment-to-moment fluctuations to day-to-day changes in factors like attention, diurnal rhythms, and environmental influences [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Prediction Accuracy in Brain-Behavior Association Studies

Problem: Low prediction accuracy when associating brain measures with behavioral traits or clinical outcomes.

Solutions:

- Increase scan duration: For fMRI scans ≤20 minutes, prediction accuracy increases linearly with the logarithm of total scan duration (sample size × scan time). Aim for at least 20-30 minutes per subject, with 30 minutes being most cost-effective on average [25].

- Implement precision mapping: Collect extensive data per participant (e.g., >20-30 minutes of fMRI data) to improve reliability of individual-level estimates [26].

- Use individualized parcellations: Rather than assuming group-level correspondence, model individual-specific patterns of brain organization. Hyper-aligning fine-grained features of functional connectivity can markedly improve prediction of general intelligence compared to region-based approaches [26].

- Address measurement error in behavior: Extend cognitive task duration (e.g., from 5 minutes to 60 minutes) to improve precision of behavioral measures, as measurement error in behavioral variables attenuates prediction performance [26].

Issue 2: High Variability in Group-Level ICA Components

Problem: Group independent component analysis (ICA) fails to adequately capture inter-subject variability in spatial activation patterns.

Solutions:

- Assess spatial variability impact: When spatial activations moderately overlap across subjects, GICA captures spatial variability well. However, with minimal overlap, estimation of subject-specific spatial maps fails [27].

- Use joint amplitude estimation: When estimating component amplitude (level of activation) across subjects, use a joint estimator across both temporal and spatial domains, especially when spatial variability is present [27].

- Optimize model order: Consider ICA model order as a factor affecting ability to compare subject activations appropriately [27].

- Employ dual regression: Use dual regression approaches to estimate subject-specific spatial maps and time courses from group-level components [27].

Issue 3: Accounting for Different Cognitive Strategies in Task-Based fMRI

Problem: Unexplained variability in activation patterns may reflect subjects employing different cognitive strategies for the same task.

Solutions:

- Identify strategies post-hoc: Use data-driven approaches like Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) to identify subgroups of subjects with similar activation patterns, then determine if these correspond to different cognitive strategies [23].

- Design constrained tasks: For tasks where strategies are known a priori, use experimental manipulations to implicitly or explicitly push participants toward a particular strategy [21].

- Collect strategy reports: Include subjective reports and behavioral measures that might indicate strategy use [21].

- Analyze by subgroup: Rather than averaging across all subjects, analyze data separately for different strategy subgroups to avoid false negatives and false positives in group averages [21].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Precision Functional Mapping for Individual-Specific Brain Organization

Purpose: To map individual-specific functional organization of the brain, revealing networks that may be unique to individuals or common across participants.

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Acquire 10+ hours of individual fMRI data per participant across multiple sessions [13].

- Preprocessing: Standard preprocessing including slice timing correction, realignment, coregistration, normalization, spatial smoothing, and bandpass filtering.

- Individualized Analysis: Analyze data at the individual level rather than relying solely on group averages.

- Network Identification: Identify both common networks across individuals and unique, person-specific networks [13].

Applications: Revealing physically interwoven but functionally distinct networks (e.g., language and social thinking networks in the frontal lobe); identifying novel brain networks in individuals that may underlie behavioral variability [13].

Purpose: To identify distinct subgroups of subjects that explain the main sources of variability in neuronal activation for a specific task.

Methodology (as implemented for reading activation):

- Data Collection: Collect fMRI data from a large sample (n=76) with varied demographic characteristics performing the task of interest [23].

- Initial Analysis: Perform one-sample t-test on all subjects, treating intersubject variability as error variance.

- Dimension Reduction: Apply Principal Component Analysis to the error variance to capture main sources of variance.

- Subgroup Identification: Use Gaussian Mixture Modeling to probabilistically assign subjects to different subgroups.

- Characterization: Conduct post-hoc analyses to determine defining differences between identified groups (e.g., demographic factors, cognitive strategies) [23].

Key Findings from Reading Study: Age and reading strategy (semantic vs. nonsemantic) were the most prominent sources of variability, more significant than handedness, sex, or lateralization [23].

Table 1: Effect of Scan Duration and Sample Size on Prediction Accuracy in BWAS

| Total Scan Duration (min) | Prediction Accuracy (Pearson's r) | Interchangeability of Scan Time & Sample Size |

|---|---|---|

| Short (≤20 min) | Lower | Highly interchangeable; logarithmic increase with total duration |

| 20-30 min | Moderate | Sample size becomes progressively more important |

| ≥30 min | Higher | Diminishing returns for longer scans; 30 min most cost-effective |

Table 2: Primary Sources of Inter-Subject Variability and Assessment Methods

| Variability Source | Assessment Method | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Strategy | Gaussian Mixture Models [23] | Different strategies employ distinct neural pathways |

| Age Effects | Post-hoc grouping analysis [23] | Significant effect on reading activation patterns |

| Structural Parameters | Morphometric analysis [21] | Grey matter density, cortical thickness, white matter connectivity |

| Functional Connectivity | Inter-subject Functional Correlation [28] | Hierarchical organization of extrinsic/intrinsic systems |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Variability Research

| Tool/Technique | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Precision fMRI Mapping | Maps individual-specific functional organization | Identifying unique and common brain networks across individuals |

| Group ICA with Dual Regression | Captures inter-subject variability in spatial patterns | Analyzing multi-subject datasets while accounting for individual differences |

| Inter-Subject Functional Correlation (ISFC) | Measures stimulus-driven functional connectivity across subjects | Dissecting extrinsically- and intrinsically-driven processes during naturalistic stimulation |

| Gaussian Mixture Modeling (GMM) | Identifies subgroups explaining main variability sources | Data-driven approach to detect different cognitive strategies |

| Hyper-Alignment | Aligns fine-grained functional features across individuals | Improves prediction of behavioral traits from brain measures |

| diethyl 1H-indole-2,5-dicarboxylate | Diethyl 1H-indole-2,5-dicarboxylate|CAS 127221-02-7 | |

| 1-[(4-Methylphenyl)methyl]-1,4-diazepane | 1-[(4-Methylphenyl)methyl]-1,4-diazepane |

Research Workflow Diagrams

Precision Research Workflow for Individual Differences

Sources of Inter-Subject Variability

Advanced Acquisition and Analysis: Boosting Sensitivity to Individual Brains

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Which design should I choose for a pre-surgical mapping of language areas in a patient with a brain tumor? A: For clinical applications like pre-surgical mapping, where the goal is robust localization of function, evidence suggests that a rapid event-related design can provide comparable or even higher detection power than a blocked design, particularly in patients [29]. It can generate more sensitive language maps and is less sensitive to head motion, which is a common concern in patient populations [29].

Q2: I am concerned about participants predicting the order of stimuli in my experiment. How can I mitigate this? A: Stimulus-order predictability is a known confound in block designs. An event-related design, particularly one with a jittered inter-stimulus interval (ISI), randomizes the presentation of stimuli, which helps to minimize a subject's expectation effects and habituation [29] [30]. This is one of the key theoretical advantages of event-related fMRI.

Q3: My primary research goal is to study individual differences in brain function. What design considerations are most important? A: Standard task-fMRI analyses often suffer from limited reliability, which is a major hurdle for individual differences research. To enhance this, consider moving beyond simple activation comparisons. Recent approaches involve deriving neural signatures from large datasets that classify brain states related to task conditions (e.g., high vs. low working memory load). These signatures have been shown to be more reliable and have stronger associations with behavior and cognition than standard activation estimates [31]. Furthermore, ensure your paradigm has high test-retest reliability at the single-subject level, which is not a given for all cognitive tasks [32].

Q4: I've heard that software errors can affect fMRI results. What should I do? A: It is critical to use the latest versions of analysis software and to be aware that errors have been discovered in popular tools in the past [33]. If you have published work using a software version in which an error was later identified, the recommended practice is to re-run your analyses with the corrected version and, in consultation with the journal, consider a corrective communication if the results change substantially [33].

Q5: How can I improve the test-retest reliability of my fMRI activations? A: Reliability can be poor at the single-voxel level due to limited signal-to-noise ratio [32]. However, the reliability of hemispheric lateralization indices tends to be higher [32]. Focusing on network-level or multivariate measures (like neural signatures) rather than isolated voxel activations can also improve reliability for individual differences research [31].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Design Problems

| Problem | Symptoms | Possible Causes & Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Detection Power | Weak or non-existent activation in expected brain regions; low statistical values. | Cause: Design lacks efficiency for the psychological process of interest. Solution: For simple contrasts, use a blocked design for its high statistical power [29] [30]. For more complex cognitive tasks, a rapid event-related design can be equally effective and avoid predictability [29]. |

| Low Reliability for Individual Differences | Brain-behavior correlations are weak or unreplicable; activation patterns are unstable across sessions. | Cause: Standard activation measures have limited test-retest reliability [31] [32]. Solution: Use paradigms with proven single-subject reliability [32]. Employ machine learning-derived neural signatures trained to distinguish task conditions, which show higher reliability and stronger behavioral associations [31]. |

| Stimulus-Order Confounds | Activation may be influenced by participant anticipation or habituation rather than the cognitive process itself. | Cause: Predictable trial sequence in a blocked design [30]. Solution: Switch to a rapid event-related design with jittered ISI to randomize stimulus order and reduce expectation effects [29]. |

| Suboptimal Design for MVPA/BCI | Poor single-trial classification accuracy for Brain-Computer Interface or Multi-Voxel Pattern Analysis applications. | Cause: Pure block designs may induce participant strategies and adaptation; pure event-related designs lack rest periods for feedback processing. Solution: Consider a hybrid blocked fast-event-related design, which combines rest periods with randomly alternating trials and has shown promising decoding accuracy and stability [34]. |

Quantitative Data Comparison of fMRI Designs

Performance Metrics Across Design Types

Table 1: A comparison of key characteristics for blocked, event-related, and hybrid fMRI designs.

| Design Feature | Blocked Design | Event-Related (Rapid) | Hybrid Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical Power/Detection Sensitivity | High [29] [30] | Comparable to or can be higher than blocked in some contexts (e.g., patient presurgical mapping) [29] | High, close to block design performance [34] |

| Stimulus Order Predictability | High, a potential confound [30] | Low, due to randomization [29] [30] | Moderate, depends on implementation |

| Resistance to Head Motion | Less sensitive [29] | More sensitive [29] | Information missing from search results |

| Ability to Isolate Single Trials | No | Yes, allows for post-hoc sorting by behavior [30] | Yes |

| Suitability for BCI/MVPA | Considered safe but may induce strategies [34] | Allows random alternation but lacks rest for feedback [34] | High, a viable alternative [34] |

| Ease of Implementation | Simple [30] | More complicated; requires careful timing [30] | More complicated |

Experimental Protocols from Key Studies

Table 2: Detailed methodologies from cited experiments comparing fMRI designs.

| Study | Participants | Task | Design Comparisons Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Xuan et al., 2008 [29] | 6 healthy controls & 8 brain tumor patients | Vocalized antonym generation | Blocked: Alternating task/rest blocks. Event-Related: Rapid, jittered ISI (stochastic design). Imaging: 3.0T GE, TR=2000 ms. |

| Chee et al., 2003 [30] | 12 (Exp1), 8 (Exp2), & 12 (Exp3) healthy volunteers | Semantic associative judgment on word triplets (Word Frequency Effect) | Exp1 (Blocked): Alternating blocks of high/low-frequency words vs. size-judgment control. Exp2 (Blocked): Same task vs. fixation control. Exp3 (Event-Related): Rapid mixed design, randomized stimuli with variable fixation (4,6,8,10s). Imaging: 2.0T Bruker, TR=2000 ms. |

| Schuster et al., 2017 [32] | Study 1: 15; Study 2: 20 healthy volunteers | Visuospatial processing (Landmark task) | Paradigm Comparison (Study 1): Compared Landmark, "dots-in-space," and mental rotation tasks. Reliability (Study 2): Test-retest of Landmark task across two sessions (5-8 days apart). Focus on lateralization index (LI) reliability. |

| Gembris et al., (Preprint) [31] | 9,024 early adolescents | Emotional n-back fMRI task (working memory) | Neural Signature Approach: Derived a classifier distinguishing high vs. low working memory load from fMRI activation patterns to capture individual differences. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

fMRI Experimental Design Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key software tools and resources for fMRI experimental design and analysis.

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| GingerALE | Software | A meta-analysis tool for combining results from multiple fMRI studies [33]. | Ensure you are using the latest version to avoid known statistical correction errors found in past releases [33]. |

| Neural Signature Classifier | Analytical Method | A machine-learning model derived from fMRI data to distinguish between task conditions and capture individual differences [31]. | More reliable and sensitive to brain-behavior relationships than standard activation analysis; requires a substantial training dataset [31]. |

| Rapid Event-Related Design | Experimental Paradigm | Presents discrete, short-duration events in a randomized, jittered fashion to reduce predictability [29]. | Ideal for isolating single trials and reducing expectation confounds; requires careful optimization of timing (ISI/ITI) [29] [30]. |

| Hemispheric Lateralization Index (LI) | Analytical Metric | Quantifies the relative dominance of brain activation in one hemisphere over the other for a specific function [32]. | Can be a robust and reliable measure at the single-subject level, even when single-voxel activation maps are not [32]. |

| Hybrid Blocked/Event-Related Design | Experimental Paradigm | Combines the rest periods of a block design with the randomly alternating trials of a rapid event-related design [34]. | A promising alternative for BCI and MVPA studies where pure block designs are sub-optimal due to participant strategy and adaptation [34]. |

| N-(4-fluorophenyl)cyclohexanecarboxamide | N-(4-fluorophenyl)cyclohexanecarboxamide|High Purity | N-(4-fluorophenyl)cyclohexanecarboxamide is a chemical research reagent. It is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| DL-Theanine | DL-Theanine, CAS:34271-54-0, MF:C7H14N2O3, MW:174.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common sources of error in DTI data that affect microstructural analysis?

The primary sources of error in DTI data are random noise and systematic spatial errors. Random noise, which results in a low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), disrupts the accurate quantification of diffusion metrics and can obscure fine anatomical details, especially in small white matter tracts [35] [36]. Systematic errors are largely caused by spatial inhomogeneities of the magnetic field gradients. These imperfections cause the actual diffusion weighting (the b-matrix) to vary spatially, leading to inaccurate calculations of the diffusion tensor and biased DTI metrics, even if the SNR is high [35] [37]. Correcting for both types of error is crucial for obtaining accurate, reliable data for studying individual brain differences.

Q2: Which specific artifacts are exacerbated at high magnetic field strengths like 7 Tesla, and how can they be mitigated?

At ultra-high fields like 7 Tesla, DTI is particularly prone to N/2 ghosting artifacts and eddy current-induced image shifts and geometric distortions [38]. These artifacts are amplified due to increased B0 inhomogeneities and the stronger diffusion gradients often used. A novel method to mitigate these issues involves a two-pronged approach:

- Optimized Navigator Echo Placement: Using a navigator echo (Nav2) acquired after the diffusion gradients, rather than before them, more accurately captures the phase perturbations induced by the gradients, leading to superior ghosting artifact correction. One study demonstrated a 41% reduction in N/2 ghosting artifacts with this method [38].

- Dummy Diffusion Gradients: Incorporating dummy gradients with opposite polarity to the main diffusion gradients helps to pre-emphasize the gradient system and reduce eddy current-induced B0 shifts, thereby improving image stability and geometric accuracy [38].

Q3: How can we acquire reliable DTI data in the presence of metal implants, such as in post-operative spinal cord studies?

Metal implants cause severe magnetic field inhomogeneities, leading to profound geometric distortions that traditionally render DTI ineffective. An effective solution is the rFOV-PS-EPI (reduced Field-Of-View Phase-Segmented EPI) sequence [39]. This technique combines two strategies:

- Reduced FOV (rFOV): Uses a two-dimensional radiofrequency (2DRF) pulse to excite a smaller area, minimizing the region affected by susceptibility artifacts.

- Phase-Segmented EPI (PS-EPI): Acquires data over multiple shots, allowing for higher resolution and reduced distortion compared to single-shot EPI.

This combined approach has been shown to produce DTI images with significantly reduced geometric distortion and signal void near cervical spine implants, enabling post-surgical evaluation that was previously not feasible [39].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common DTI Artifacts

| Artifact/Symptom | Root Cause | Corrective Action | Key Experimental Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low SNR & Noisy Metrics | Insufficient signal averaging; high-resolution acquisition | Implement a denoising algorithm that leverages spatial similarity and diffusion redundancy [36]. | Pre-denoising with local kernel PCA; post-filtering with non-local mean [36]. |

| Spatially Inaccurate FA/MD Maps | Gradient field nonlinearities (systematic error) | Apply B-matrix Spatial Distribution (BSD) correction using a calibrated phantom [35] [37]. | Scanner-specific spherical harmonic functions or phantom-based b(r)-matrix mapping [37]. |

| Geometric Distortions & Ghosting | Eddy currents & phase inconsistencies (esp. at 7T) | Use optimized navigator echoes (Nav2) + dummy diffusion gradients [38]. | Navigator placed after diffusion gradients; dummy gradient momentum at 0.5x main gradient [38]. |

| Metal-Induced Severe Distortions | Magnetic field inhomogeneity from implants | Employ a rFOV-PS-EPI acquisition sequence [39]. | 2DRF pulse for FOV reduction; phase-encoding segmentation [39]. |

| Through-Plane Partial Volume Effects | Large voxel size in slice direction | Use 3D reduced-FOV multiplexed sensitivity encoding (3D-rFOV-MUSE) for high-resolution isotropic acquisition [40]. | Isotropic resolution (e.g., 1.0 mm³); cardiac triggering; navigator-based shot-to-shot phase correction [40]. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for DTI

| Item | Function in DTI Acquisition | Example Specification/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Isotropic Diffusion Phantom | Serves as a ground truth reference for validating DTI metrics and calibrating BSD correction for systematic errors [37]. | Phantom with known, spatially resolved diffusion tensor field (D(r)) for scanner-specific calibration [37]. |

| Anisotropic Diffusion Phantom | Provides a structured reference to evaluate the accuracy of fiber tracking and the correction of gradient nonlinearities [37]. | Phantom with defined anisotropic structures (e.g., synthetic fibers) to test tractography fidelity [37]. |

| Cervical Spine Phantom with Implant | Enables the development and testing of metal artifact reduction sequences in a controlled setting. | Custom-built model with titanium alloy implants and an asparagus stalk as a spinal cord surrogate [39]. |

| Cryogenic Radiofrequency Coils | Significantly boosts the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), which is critical for high-resolution DTI in small structures or rodent brains [41]. | Two-element transmit/receive ( ^1H ) cryogenic surface coil for rodent imaging at 11.7 T [41]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Combined Denoising and BSD Correction for Enhanced Metric Accuracy

This protocol details the steps to minimize both random noise and systematic spatial errors in a brain DTI study, which is vital for detecting subtle individual differences [35].

Workflow Overview

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Acquire multi-directional DWI data using a single-shot EPI sequence on a 3T or higher scanner. Include a sufficient number of diffusion directions and b-values (e.g., b=1000 s/mm²) for tensor fitting.

- Denoising: Process the magnitude DWI images using a denoising algorithm that exploits both spatial similarity (via patch-based non-local mean filtering) and diffusion redundancy (via local kernel principal component analysis) to improve SNR without blurring critical anatomical details [36].

- BSD Correction: Characterize the spatial distribution of the b-matrix, b(r), using a pre-calibrated isotropic or anisotropic phantom scanned with the same protocol. Apply this spatial correction to the in-vivo DWI data to account for gradient field nonlinearities [35] [37].

- Tensor Estimation and Analysis: Recompute the diffusion tensor and derive maps of FA, MD, AD, and RD. Subsequent analysis in structures like the corpus callosum and internal capsule will show significantly improved accuracy and reliability [35].

Protocol 2: High-Fidelity 3D DTI of the Cervical Spinal Cord

This protocol is designed for high-resolution, distortion-reduced imaging of the cervical spinal cord, addressing challenges like small tissue size and CSF pulsation [40].

Workflow Overview

Methodology:

- Sequence: Use a 3D reduced-FOV multiplexed sensitivity encoding (3D-rFOV-MUSE) sequence. This involves a sagittal thin-slab acquisition [40].

- Artifact Suppression:

- rFOV: A 2D RF pulse is applied to restrict the FOV in the phase-encode direction, minimizing distortions from off-resonance effects.

- Cardiac Triggering: Data acquisition is synchronized with the cardiac cycle to minimize pulsation artifacts from cerebrospinal fluid.

- Reconstruction: The MUSE algorithm integrates a self-referenced ghost correction and a 2D navigator-based inter-shot phase correction to simultaneously eliminate Nyquist ghosting and aliasing artifacts from the multi-shot acquisition [40].

- Outcome: This pipeline produces high-resolution (e.g., 1.0 mm isotropic) DTI data of the cervical cord with mitigated through-plane partial volume effects, enabling multi-planar reformation and more accurate quantification of biomarkers [40].

Leveraging Multivariate Pattern Analysis (MVPA) and Neural Signatures

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Data Acquisition & Preprocessing

Q: Our MVPA results are inconsistent across repeated scanning sessions. How can we improve reliability for individual differences research?

A: Inconsistent results often stem from insufficient attention to individual anatomical and functional variability.

- Solution: Move beyond simple volumetric registration to a common template (e.g., MNI152). Employ advanced, functionally-informed alignment techniques to ensure you are comparing functionally homologous regions across subjects [42].

- Multimodal Surface Matching (MSM): A framework that uses a combination of anatomical (cortical folding) and functional data (e.g., from movie-watching or resting-state) to achieve a better vertex-wise match across individuals [42].

- Hyperalignment: This technique projects individual brains into a common high-dimensional "representational space" based on the similarity of their neural response patterns, effectively aligning brains based on function rather than anatomy alone [42].

- Recommendation: For individual differences research, try multiple alignment approaches and report all results to build collective knowledge about best practices [42].

Q: How much data do I need to collect per subject to obtain reliable neural signatures for individual differences studies?

A: Reliability requires substantial data. While traditional group-level fMRI studies often use 15-30 participants, individual differences research demands much larger sample sizes and more data per subject [42].

- Within-Subject: For resting-state fMRI, at least 5 minutes of data are needed, though advanced analyses may require up to 100 minutes for best results [42].

- Between-Subject: Sample size is critical for brain-behavior correlations. One large-scale study (N=1,498) demonstrated that the effect size of brain-behavior correlations only stabilized and became reproducible with sample sizes greater than 500 participants [43]. For smaller studies, using cross-validation and reporting out-of-sample predictive value is essential [42].

MVPA Analysis & Classification

Q: My classifier performance is at chance level. What are the most common causes and fixes?

A: Poor classifier performance can originate from several points in the analysis pipeline.

- Troubleshooting Table:

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Feature Selection | Using too many voxels, including irrelevant ones, leading to the "curse of dimensionality." [44] | Employ feature selection (e.g., ANOVA, recursive feature elimination) or use a searchlight approach to focus on informative voxel clusters [44] [45]. |

| Model Complexity | Using a complex, non-linear classifier with limited data, causing overfitting. | Start with a simple linear classifier like Linear Support Vector Machine (SVM) or Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), which are robust and work well with high-dimensional fMRI data [44] [45]. |

| Cross-Validation | Data leakage between training and test sets, giving over-optimistic performance. | Use strict cross-validation (e.g., leave-one-run-out or leave-one-subject-out) and ensure all preprocessing steps are applied independently to training and test sets [44] [45]. |

| Experimental Design | The cognitive states of interest are not robustly distinguished by brain activity patterns. | Pilot your task behaviorally; ensure conditions are perceptually or cognitively distinct. |

Q: Should I use a univariate GLM or MVPA for my study?

A: The choice depends on your research question, as these methods are complementary [44] [45].

- Use Mass-Univariate GLM: When your goal is to localize which specific brain regions are significantly "activated" by a task or condition compared to a baseline. It answers "Where is the effect?" [44] [45].

- Use MVPA: When your goal is to test whether distributed patterns of brain activity, often across multiple voxels or regions, contain information that can discriminate between experimental conditions. It answers "What information is represented?" and is generally more sensitive to distributed representations [44] [45].

- Searchlight Analysis: This MVPA technique offers a middle ground, providing a good balance between sensitivity and spatial localizability by moving a small "searchlight" across the brain to perform multivariate classification at each location [45].

Neural Signatures & Individual Differences

Q: How can I create and validate a neural signature that predicts a behavioral trait?

A: Building a predictive neural signature involves a rigorous, multi-step process to ensure it is valid and generalizable.

- Step 1: Define the Signature. Use a multivariate model (e.g., SVM, LASSO regression) trained on brain activity patterns (features) to predict a behavioral measure (target). For example, a study predicted a target's self-reported emotional intent from an observer's distributed brain activity pattern [46].

- Step 2: Internal Validation. Always use cross-validation (e.g., leave-one-subject-out) to assess performance on held-out data from the same study sample. This controls for overfitting [46].

- Step 3: External Validation. Test the signature's predictive power on a completely new, independent dataset. This is the gold standard for establishing a signature's robustness and utility [42] [46].

- Critical Consideration: Be aware that individual differences can be confounded by anatomical misalignment or non-neural physiological factors (e.g., vascular health). Using functionally-informed alignment and collecting large samples are key to mitigating these issues [42].

Q: We found a brain region that shows a strong group-level effect, but it does not correlate with individual behavior. Why?

A: This is a common and important finding. A region's involvement in a cognitive function at the group level does not automatically mean that its inter-individual variability explains behavioral differences [43].

- Explanation: A large-scale study on episodic memory encoding found that while many regions (e.g., lateral occipital cortex) showed a classic "subsequent memory effect" at the group level, only a subset of these regions (e.g., hippocampus, orbitofrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex) had activity levels that accounted for individual variability in memory performance [43].

- Implication: The neural mechanisms supporting a function on average may differ from those that determine how well an individual performs that function. Always directly test brain-behavior correlations for inferences about individual differences [43].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Standard MVPA Analysis Workflow

This protocol outlines the core steps for a typical MVPA study, from data preparation to statistical inference [44] [45].

- Data Preparation & Preprocessing: Standard fMRI preprocessing (motion correction, slice-timing correction, normalization). Critically, spatial smoothing should be minimized or omitted, as it can blur the fine-grained spatial patterns that MVPA seeks to detect.

- Feature Construction/Selection: For each trial or time point, create a feature vector representing the brain activity pattern. This can be the activity of all voxels within a predefined region of interest (ROI) or across the whole brain. Feature selection can be applied to reduce dimensionality.

- Label Assignment: Assign a class label (e.g., "Face" or "House") to each feature vector based on the experimental condition.

- Classifier Training & Testing with Cross-Validation:

- Split the data into k-folds.

- For each fold, train a classifier (e.g., Linear SVM) on the data from k-1 folds.

- Test the trained classifier on the held-out fold to obtain a prediction.

- Repeat until all folds have been used as the test set.

- Performance Evaluation & Statistical Testing: Calculate the average classification accuracy across all folds. Compare this accuracy to chance level (e.g., 50% for two classes) using a binomial test or permutation testing to establish statistical significance.

MVPA Analysis Workflow

Protocol 2: Establishing a Neural Signature for Individual Differences

This protocol describes the steps for building a neural signature predictive of a continuous behavioral trait, a common goal in individual differences research [43] [46].

- Define Target Behavior: Precisely define and measure the behavioral variable of interest (e.g., empathic accuracy, memory performance).

- Acquire and Preprocess fMRI Data: Use a task that robustly engages the neural systems related to the behavior. Apply preprocessing with advanced inter-subject alignment (e.g., MSM, hyperalignment).

- Extract Neural Features: Create whole-brain maps of parameter estimates (e.g., contrast maps from a GLM) for each subject.

- Train a Predictive Model: Use a regression model with regularization (e.g., LASSO-PCR) to predict the behavioral score from the neural features. Employ leave-one-subject-out cross-validation to avoid overfitting.

- Validate the Signature: Critically, test the signature's predictive power on a completely independent, held-out sample of participants to demonstrate generalizability.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for MVPA and Neural Signature Research

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| MVPA Software Toolboxes | Provides high-level functions for classification, regression, cross-validation, and searchlight analysis. | MVPA-Light [45]: A self-contained, fast MATLAB toolbox with native implementations of classifiers. Other options: PyMVPA (Python), The Decoding Toolbox (TDD), LIBSVM/LIBLINEAR interfaces [44] [45]. |

| Advanced Alignment Tools | Improves functional correspondence across subjects for individual differences studies. | Multimodal Surface Matching (MSM) [42]: Aligns cortical surfaces using anatomical and functional data. Hyperalignment [42]: Projects brains into a common model-based representational space. |

| Linear Classifiers | The standard choice for many fMRI-MVPA studies due to their robustness in high-dimensional spaces. | Support Vector Machine (SVM) [44]: Maximizes the margin between classes. Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) [45]: Finds a linear combination of features that separates classes. |

| Cross-Validation Scheme | Provides a realistic estimate of model performance and controls for overfitting. | Leave-One-Subject-Out (LOSO): Essential for ensuring that the model generalizes to new individuals, a cornerstone of individual differences research [46]. |

| Standardized Localizer Tasks | Efficiently and reliably identifies subject-specific functional regions of interest. | Why/How Task: Localizes regions for mental state attribution (Theory of Mind) [47]. False-Belief Localizer: The standard for identifying the Theory of Mind network [47]. |

| (3-Chloro-quinoxalin-2-yl)-isopropyl-amine | (3-Chloro-quinoxalin-2-yl)-isopropyl-amine, CAS:1234370-93-4, MF:C11H12ClN3, MW:221.688 | Chemical Reagent |

| Isodiazinon | Isodiazinon|CAS 82463-42-1|For Research | Isodiazinon is a diazinon isomer for environmental fate and toxicity studies. For research use only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Neural Signature Validation Pipeline

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary limitation of conventional TMS targeting that precision neuromodulation aims to solve? Conventional TMS methods, such as the "5-cm rule" or motor hotspot localization, largely overlook inter-individual variations in brain structure and functional connectivity. This failure to account for individual differences in cortical morphology and brain network organization leads to considerable variability in treatment responses and limits overall clinical efficacy [48].

Q2: How do fMRI and DTI each contribute to personalized TMS targeting? fMRI and DTI provide complementary information for target identification:

- fMRI: Provides high spatial resolution for mapping individual functional brain networks and identifying pathological circuits. For example, in depression, the functional connectivity between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (sgACC) can predict TMS treatment response [48].

- DTI: Visualizes and quantifies the integrity and trajectories of white matter fibers, elucidating the structural underpinnings of functional connectivity and helping to optimize stimulation pathways [48].

Q3: What is a closed-loop TMS system and what advantage does it offer? A closed-loop TMS system continuously monitors a biomarker representing the brain's state (e.g., via EEG or real-time fMRI) and uses this feedback to dynamically adjust stimulation parameters in real-time. This approach aims to drive the brain from its current state toward a desired state, overcoming the limitations of static, open-loop paradigms and accounting for both inter- and intra-individual variability [49].

Q4: What are common technical challenges when integrating real-time fMRI with TMS? Key challenges include managing the timing between stimulation and data acquisition, selecting the appropriate fMRI context (task-based vs. resting-state), accounting for inherent brain oscillations, defining the dose-response function, and selecting the optimal algorithm for personalizing stimulation parameters based on the feedback signal [49].

Q5: Can you provide an example of a highly successful precision TMS protocol? Stanford Neuromodulation Therapy (SNT) is a pioneering protocol. It uses resting-state fMRI to identify the specific spot in a patient's DLPFC that shows the strongest negative functional correlation with the sgACC. It then applies an accelerated, high-dose intermittent TBS pattern. This individualized approach achieved a remission rate of nearly 80% in patients with treatment-resistant depression in a controlled trial [48].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Inter-Subject Variability in TMS Response

Symptoms: Significant differences in clinical or neurophysiological outcomes between subjects receiving identical TMS stimulation protocols.

Potential Causes & Solutions:

| Step | Problem Area | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Target Identification | Verify that fMRI-guided targeting (e.g., DLPFC-sgACC anticorrelation) was performed using a validated, standardized processing pipeline. | Implement an individualized targeting workflow using resting-state fMRI to define the stimulation target based on each subject's unique functional connectivity profile [48]. |

| 2 | Skull & Tissue Anatomy | Check if individual anatomical data (e.g., T1-weighted MRI) was used for electric field modeling. | Use finite element method (FEM) modeling based on the subject's own MRI to simulate and optimize the electric field distribution for their specific brain anatomy [48]. |

| 3 | Network State | Assess if the subject's brain state at the time of stimulation was accounted for, as it can dynamically influence response. | Move towards a closed-loop system that uses real-time neuroimaging (EEG/fMRI) to adjust stimulation parameters based on the instantaneous brain state [49]. |

Issue 2: Suboptimal Integration of Multimodal Imaging Data for Targeting

Symptoms: Inconsistent target locations when using different imaging modalities (e.g., fMRI vs. DTI); difficulty fusing data into a single neuronavigation platform.

Potential Causes & Solutions:

| Step | Problem Area | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Data Co-registration | Confirm the accuracy of co-registration between the subject's fMRI, DTI, and anatomical scans. | Ensure use of high-resolution anatomical scans as the registration baseline and validate alignment precision within the neuronavigation software. |

| 2 | Cross-Modal Fusion | Check if the functional target (fMRI) is structurally connected via the white matter pathways identified by DTI. | Adopt an integrative framework where fMRI identifies the pathological network node, and DTI ensures the stimulation site is optimally connected to that network [48]. |

| 3 | Model Generalizability | Evaluate if the AI/ML model used for target prediction was trained on a dataset with sufficient demographic and clinical diversity. | Utilize machine learning models that are robust to scanner and population differences, or fine-tune models with local data to improve generalizability [48]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Key Experimental Protocol: An Integrative Precision TMS Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a step-by-step framework for precision TMS, from diagnosis to closed-loop optimization [48].

Table 1: Clinical Efficacy of Conventional vs. Precision TMS Protocols for Depression

| Protocol | Targeting Method | Key Stimulation Parameters | Approximate Response Rate | Remission Rate | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional rTMS | Scalp-based "5-cm rule" | 10 Hz, 120% MT, ~3000 pulses/session, 6 weeks | ~50% | ~33% | [50] |

| Precision SNT | fMRI-guided (DLPFC-sgACC) | iTBS, 90% MT, ~1800 pulses/session, 10 sessions/day for 5 days | Not specified | ~80% | [48] |

Table 2: Technical Specifications for Imaging Modalities in Precision TMS

| Modality | Primary Role in TMS | Key Metric for Targeting | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fMRI | Functional target identification | Functional connectivity (e.g., DLPFC-sgACC anticorrelation) | High (mm) | Low (seconds) | Predicts therapeutic response; identifies pathological circuits [48] |

| DTI | Structural pathway optimization | Fractional Anisotropy (FA), Tractography | High (mm) | N/A | Guides modulation of structural pathways; informs electric field modeling [48] |

| EEG/MEG | Real-time state assessment | Brain oscillations (e.g., Alpha, Theta power) | Low (cm) | High (milliseconds) | Enables closed-loop control by providing real-time feedback on brain state [48] [49] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Resources for Precision TMS Research

| Item | Category | Function in Research | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3T MRI Scanner | Imaging Equipment | Acquires high-resolution structural (T1, T2), functional (fMRI), and diffusion (DTI) data. | Essential for obtaining individual-level data for target identification and electric field modeling. |

| Neuronavigation System | Software/Hardware | Co-registers individual MRI data with subject's head to guide precise TMS coil placement. | Ensures accurate targeting of the computationally derived brain location. |

| TMS Stimulator with cTBS/iTBS | Stimulation Equipment | Delivers patterned repetitive magnetic pulses to the targeted cortical area. | Protocols like iTBS allow for efficient, shortened treatment sessions [48]. |

| Computational Modeling Software | Software | Creates finite element models (FEM) from individual MRIs to simulate electric field distributions. | Optimizes stimulation dose by predicting current flow in the individual's brain anatomy [48]. |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Analytical Tool | Analyzes large-scale neuroimaging and clinical data to predict optimal stimulation targets and treatment response. | Includes support vector machines (SVM), random forests, and deep learning models [48]. |

| Real-time fMRI/EEG Setup | Feedback System | Measures instantaneous brain activity during stimulation for closed-loop control. | Allows for dynamic adjustment of stimulation parameters based on the detected brain state [49]. |

| 2-Amino-1-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)ethanone | 2-Amino-1-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)ethanone, CAS:499-61-6, MF:C8H9NO3, MW:167.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Lithium, (dimethylphenylsilyl)- | Lithium, (dimethylphenylsilyl)-, CAS:3839-31-4, MF:C8H11LiSi, MW:142.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Pipeline Precision: Systematic Optimization of Preprocessing and Computational Strategies

Troubleshooting Guides

Spatial Smoothing Implementation

Issue: Users expect fMRIPrep to perform spatial smoothing automatically, but outputs lack this step.

Explanation: fMRIPrep is designed as an analysis-agnostic tool that performs minimal preprocessing and intentionally omits spatial smoothing. This step is highly dependent on the specific statistical analysis and hypotheses of your study [51] [52]. Applying an inappropriate kernel size could reduce statistical power or introduce spurious results in downstream analysis.

Solution: Perform spatial smoothing as the first step of your first-level analysis using your preferred statistical package (SPM, FSL, AFNI). Alternatively, apply smoothing directly to the *space-MNI152NLin2009cAsym_desc-preproc_bold.nii.gz files output by fMRIPrep [51].

Exception: If using ICA-AROMA for automated noise removal, the *desc-smoothAROMAnonaggr_bold.nii.gz outputs have already undergone smoothing with the SUSAN filter and should not be smoothed again [51].

Temporal Filtering Configuration

Issue: Preprocessed BOLD time series contain unwanted low-frequency drift or high-frequency noise.

Explanation: fMRIPrep does not apply temporal filters to the main preprocessed BOLD outputs by default. The pipeline calculates noise components but leaves the application of temporal filters to the user's analysis stage [51] [53].

Solution:

- High-pass filtering: Implement during first-level model specification in your analysis software

- Band-pass filtering (for resting-state fMRI): Apply using specialized tools (e.g.,

fslmaths,3dTproject) - Confound regression: Use the comprehensive confounds tables generated by fMRIPrep (

*_desc-confounds_timeseries.tsv) alongside temporal filtering

Motion Correction Diagnostics

Issue: Suspicious motion parameters or poor correction in preprocessed data.

Explanation: fMRIPrep performs head-motion correction (HMC) using FSL's mcflirt and generates extensive motion-related diagnostics [53] [52]. The quality of correction depends on data quality and acquisition parameters.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check motion parameters: Review the

*_desc-confounds_timeseries.tsvfile for motion parameters (transx, transy, transz, rotx, roty, rotz) - Assess framewise displacement: Use the

framewise_displacementcolumn in confounds file to identify high-motion volumes - Inspect reports: Carefully examine the visual HTML reports for each subject to identify poor motion correction

- Consider data exclusion: For framewise displacement > 0.5mm, consider excluding volumes or the entire run if excessive motion is present

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does fMRIPrep not include spatial smoothing and temporal filtering by default?

A1: fMRIPrep follows a "glass box" philosophy and aims to be analysis-agnostic [52]. These steps are highly specific to your research question and analysis method. Leaving them to the user ensures flexibility and prevents inappropriate processing that could compromise different analysis approaches.

Q2: What motion-related outputs does fMRIPrep provide?

A2: fMRIPrep generates comprehensive motion-related data [53]:

- Motion parameters: 6 rigid-body parameters (3 translation, 3 rotation)

- Framewise displacement: A scalar measure of volume-to-volume motion [52]

- DVARS: Rate of change of BOLD signal across volumes

- Motion-corrected BOLD series: In native and standard spaces

- Transform files: For head-motion correction

Q3: How should I handle slice-timing correction in my workflow?

A3: Slice-timing correction is available in current fMRIPrep versions [51]. For older versions, you needed to perform slice-timing correction separately (using SPM, FSL, or AFNI) before running fMRIPrep. Check your fMRIPrep version documentation to confirm implementation.

Q4: What are the computational requirements for running fMRIPrep with these preprocessing steps?

A4: Table: Computational Requirements for fMRIPrep Processing

| Resource Type | Minimum Recommended | Optimal Performance |

|---|---|---|

| CPU Cores | 4 cores | 8-16 cores |

| Memory (RAM) | 8 GB | 16+ GB |

| Processing Time | ~2 hours/subject (with 4 cores) | ~1 hour/subject (with 16 cores) |

| Disk Space | 20-40 GB/subject | 40+ GB/subject (with full outputs) |

These requirements are for fMRIPrep itself; additional resources are needed for subsequent smoothing and filtering steps [54].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Validating Motion Correction

Purpose: To verify the quality of motion correction in fMRIPrep outputs.

Steps:

- Run fMRIPrep on your dataset with the

--output-spaces MNI152NLin2009cAsymflag - Extract mean framewise displacement (FD) values from confounds files

- Set exclusion criteria (e.g., mean FD > 0.2mm or >20% volumes with FD > 0.5mm)

- Inspect visual reports for alignment quality between BOLD reference and T1w images

- Correlate motion parameters with task design to identify task-related motion

Protocol for Spatial Smoothing Optimization

Purpose: To determine the optimal smoothing kernel for your analysis.

Steps:

- Extract preprocessed BOLD data from fMRIPrep outputs (

*_desc-preproc_bold.nii.gz) - Apply different smoothing kernels (e.g., 4mm, 6mm, 8mm FWHM) to separate copies

- Run identical first-level analyses on each smoothed dataset

- Compare signal-to-noise ratio and activation patterns

- Select kernel size that balances sensitivity and specificity for your study

Workflow Visualization

fMRIPrep Preprocessing and User-Defined Steps

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Software Tools for fMRI Preprocessing and Analysis

| Tool Name | Function in Preprocessing | Application in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| fMRIPrep | Robust, automated preprocessing pipeline; generates motion-corrected, normalized data | Provides analysis-ready BOLD data and confounds for statistical analysis [55] [52] |

| FSL | Motion correction (mcflirt), ICA-AROMA for noise removal |

Spatial smoothing (susann), temporal filtering, GLM analysis (FEAT) [52] |

| SPM | Slice-timing correction, spatial smoothing | First- and second-level GLM analysis, DCM for effective connectivity |

| AFNI | Slice-timing correction (3dTshift), spatial smoothing (3dBlurInMask) |

Generalized linear modeling (3dDeconvolve), cluster-based thresholding |

| ANTs | Spatial normalization to template space | Advanced registration, region-of-interest analysis |

| FreeSurfer | Cortical surface reconstruction, segmentation | Surface-based analysis, ROI definition from atlases |

| MRIQC | Quality assessment of raw and processed data | Identifying exclusion criteria, dataset quality control [56] [57] |

| 4-[3-(Benzyloxy)phenyl]phenylacetic acid | 4-[3-(Benzyloxy)phenyl]phenylacetic Acid | High-purity 4-[3-(Benzyloxy)phenyl]phenylacetic acid for research. Explore its potential as a synthetic intermediate. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Trihexyl phosphite | Trihexyl phosphite, CAS:6095-42-7, MF:C18H39O3P, MW:334.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Evaluating the Impact of Preprocessing Choices on Outcome Metrics and Statistical Power

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: How do preprocessing choices affect my study's statistical power?