Non-Invasive Brain-Computer Interfaces: A Comprehensive 2025 Review of Technologies, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a systematic review of the rapidly evolving field of non-invasive Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Non-Invasive Brain-Computer Interfaces: A Comprehensive 2025 Review of Technologies, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a systematic review of the rapidly evolving field of non-invasive Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the fundamental principles of major non-invasive technologies including EEG, fNIRS, and emerging methods like wearable MEG and digital holographic imaging. The review analyzes current methodological approaches and their applications in neurological disorders, spinal cord injury rehabilitation, and cognitive enhancement. It addresses critical technical challenges such as signal quality optimization and presents evidence-based performance comparisons. By synthesizing the latest research trends, clinical validation studies, and technological innovations, this article serves as a comprehensive reference for professionals navigating the transition of non-invasive BCIs from laboratory research to clinical practice and commercial applications.

Principles and Evolution of Non-Invasive Neural Signal Acquisition

Historical Context and Fundamental Principles of Non-Invasive BCI

A Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) establishes a direct communication pathway between the brain and an external device, bypassing the body's normal neuromuscular output channels [1]. This technology has evolved from a scientific curiosity to a robust field with significant applications in medical rehabilitation, assistive technology, and human-computer interaction. Non-invasive BCIs, which record brain activity from the scalp without surgical implantation, represent a particularly accessible and safe category of these interfaces [2] [3]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of non-invasive BCI, detailing its historical development, fundamental principles, and the core methodologies that underpin its operation, framed within the context of a broader review and comparison of non-invasive BCI technologies.

Historical Context

The foundations of non-invasive BCI are inextricably linked to the discovery and development of methods to record the brain's electrical activity.

- 19th Century Foundations: The earliest roots of BCI trace back to 1875 when English physicist Richard Caton first recorded electrical signals from the brains of animals [4].

- Birth of Human EEG (1924): The pivotal moment for non-invasive interfacing came in 1924 when German psychiatrist Hans Berger made the first recording of electrical brain activity from a human scalp, a technique he named the electroencephalogram (EEG). His 1930 publication, "Über das Elektrenkephalogramm des Menschen," detailed the identification of alpha and beta waves, laying the groundwork for all subsequent EEG-based BCI research [4].

- First Human BCI (1973): The first successful demonstration of a BCI in a human occurred at the University of California, Los Angeles. Participants in this study, supported by DARPA and the National Science Foundation, learned to control a cursor on a computer screen using their mental activity derived from EEG signals, specifically visual evoked potentials [5] [6].

- Modern Evolution: Over recent decades, the field has rapidly advanced from simple cursor control to the complex operation of robotic devices, exoskeletons, and communication systems, driven by improvements in signal processing, machine learning, and sensor technology [3] [2].

Fundamental Principles and Components

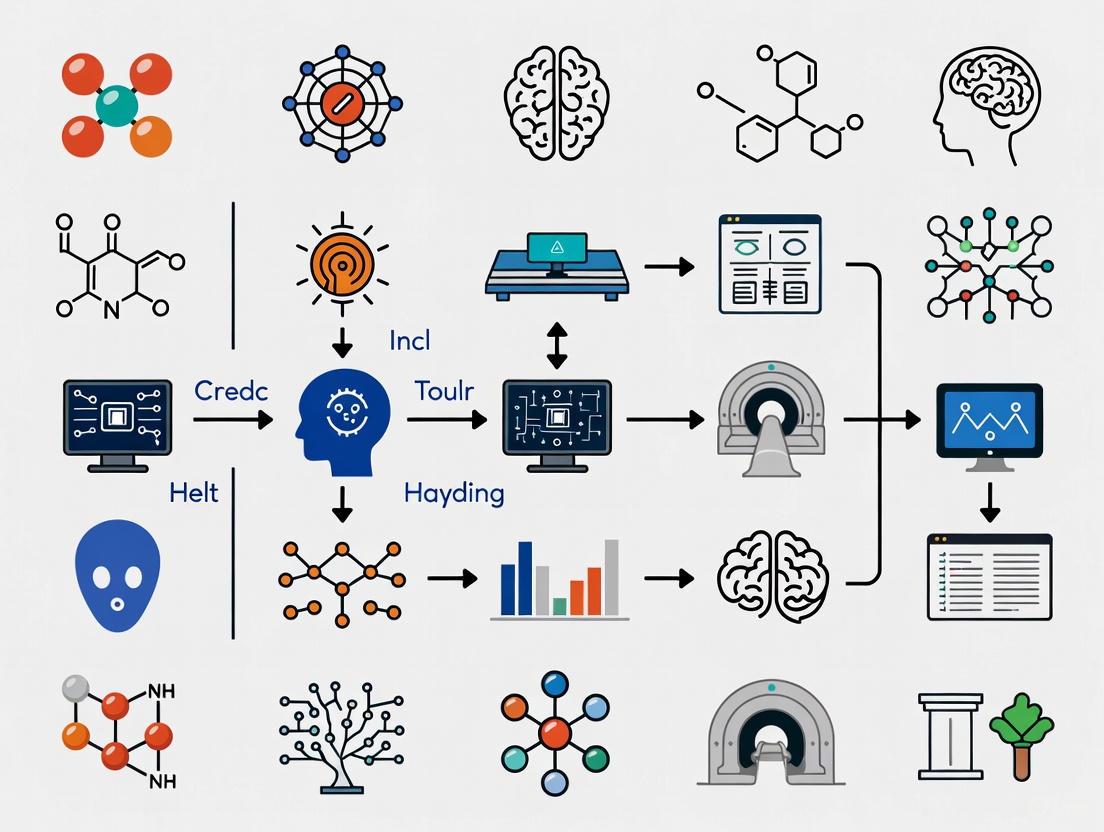

At its core, a BCI is a closed-loop system that translates specific patterns of brain activity into commands for an external device. The system operates through a sequence of four standardized stages, as illustrated in the workflow below.

Figure 1: The standardized workflow of a non-invasive Brain-Computer Interface system, illustrating the sequential stages from signal acquisition to device control and user feedback.

Core BCI Components

- Signal Acquisition: This initial stage involves measuring brain activity. Non-invasive BCIs primarily use Electroencephalography (EEG), which records voltage fluctuations resulting from ionic current flows within the brain's neurons through electrodes placed on the scalp [2] [7]. Other modalities include Magnetoencephalography (MEG), which detects the magnetic fields induced by neuronal electrical currents, and functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS), which measures hemodynamic activity correlated with neural firing via light absorption [3] [8].

- Preprocessing: The acquired neural signals are characteristically weak and contaminated with noise from both physiological (e.g., eye blinks, muscle movement, heart rate) and external sources (e.g., line interference) [5]. Preprocessing applies techniques such as filtering (to remove irrelevant frequency bands), artifact removal, and signal averaging to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) [1] [5].

- Feature Extraction: In this stage, the preprocessed signal is analyzed to identify discriminative patterns or features that correspond to the user's intent. These features can be extracted in the time-domain (e.g., event-related potentials like the P300), frequency-domain (e.g., power in specific frequency bands like Mu or Beta rhythms), or spatial-domain (e.g., patterns across different electrode locations) [5] [1].

- Feature Classification and Translation: The extracted features are fed into a translation algorithm or classifier—often employing machine learning techniques such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) or Neural Networks—which maps the feature vector to a specific output command [1] [5]. This command is then executed by an external device, such as a robotic arm, wheelchair, or speller application [3].

A critical element for effective BCI operation is neuroplasticity, the brain's inherent ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections. This allows users to learn, through feedback and training, how to modulate their brain activity to improve BCI control over time [1].

Technical Comparison of Non-Invasive Modalities

The performance of a non-invasive BCI is governed by the inherent properties of its signal acquisition modality. The table below summarizes the key technical benchmarks for the primary non-invasive methods.

Table 1: Technical comparison of major non-invasive brain activity recording modalities used in BCI research.

| Modality | Primary Signal | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Portability & Cost | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEG | Electrical potentials | ~1 cm | Excellent (ms) | High portability, Low cost [2] | High temporal resolution, low cost, safe, easy to use [2] [4] | Signal degraded by skull/scalp [2] |

| MEG | Magnetic fields | ~2-3 mm | Excellent (ms) | Low portability, Very High cost | Excellent spatiotemporal resolution | Requires shielded room [8] |

| fNIRS | Hemodynamic (blood flow) | ~1 cm | Poor (seconds) | Moderate portability, Moderate cost | Less sensitive to movement artifacts | Low temporal resolution [8] |

| DHI* | Tissue deformation (nanometer) | High (µm-mm) | Good (ms) | Under development | Novel, high-resolution optical signal | Early research stage [9] |

DHI: Digital Holographic Imaging, an emerging technique included for completeness [9].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To illustrate the practical application of these principles, below are detailed methodologies for two key BCI paradigms: one for motor rehabilitation and another for cognitive intervention.

Protocol 1: Motor Function Rehabilitation for Spinal Cord Injury

A 2025 meta-analysis established a protocol for applying non-invasive BCI to improve motor and sensory function in patients with Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) [10].

- Objective: To quantitatively assess the effects of non-invasive BCI intervention on motor function, sensory function, and the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) in SCI patients.

- Study Design: Randomized controlled trial (RCT) or self-controlled trial.

- Participants: Patients with spinal cord injury (AIS grades A-D). The meta-analysis included 109 patients across 9 studies [10].

- Intervention:

- BCI Setup: A non-invasive BCI system, typically using an EEG cap, is configured.

- Paradigm: Patients engage in motor imagery (MI), mentally rehearsing movements (e.g., grasping, walking) without physical execution. The BCI decodes the associated sensorimotor rhythms (EEG power changes in Mu/Beta bands) [10] [5].

- Feedback & Actuation: The decoded motor intention is used to trigger a functional electrical stimulation (FES) device attached to the patient's paralyzed limb or to control a robotic exoskeleton. This creates a closed-loop system where the brain's intention is directly linked to the resulting movement, reinforcing neural pathways [10].

- Outcome Measures:

- Motor Function: ASIA motor score, Lower Extremity Motor Score (LEMS).

- Sensory Function: ASIA sensory scores.

- Activities of Daily Living (ADL): Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM), Barthel Index (BI) [10].

- Key Findings: The meta-analysis concluded that BCI intervention had a statistically significant, medium-effect-size impact on motor function (SMD=0.72) and a large-effect-size impact on sensory function (SMD=0.95) and ADL (SMD=0.85) [10].

Protocol 2: Cognitive-Social Intervention for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Non-invasive BCI systems integrated with Virtual Reality (VR) have been developed as intervention tools for school-aged individuals with ASD [7].

- Objective: To improve social and cognitive skills, such as joint attention and emotional recognition, in individuals with ASD.

- Study Design: Controlled intervention study.

- Participants: School-aged children and adolescents diagnosed with ASD.

- Intervention:

- BCI-VR Setup: The user wears a non-invasive EEG headset and a VR headset, creating an immersive and controlled environment.

- Paradigm: The user is presented with social scenarios or cognitive tasks within the VR environment (e.g., recognizing emotions on a virtual character's face, or following a gaze cue).

- Neurofeedback: The BCI system monitors the user's brain states in real-time, such as levels of attention or engagement. Positive performance in the task, or successful self-regulation of the target brain state, is rewarded with success in the VR narrative (e.g., the virtual character smiles), creating a direct feedback loop [7].

- Outcome Measures: Pre- and post-intervention assessments using standardized scales for social responsiveness, cognitive tasks, and analysis of EEG patterns.

- Key Findings: A systematic review of nine such protocols concluded that BCI-VR interventions are safe, with no reported side effects, and show promise for improving core social and cognitive deficits in ASD by leveraging neuroplasticity within a structured and engaging environment [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key materials and software tools essential for non-invasive BCI research and experimentation.

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application in BCI Research |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Acquisition Hardware | EEG systems (e.g., with wet or dry electrodes), fNIRS systems, MEG systems [8] | Measures and digitizes the raw physiological signal from the brain. Dry electrodes are an innovation improving ease of use [8]. |

| Electrodes & Sensors | Ag/AgCl wet electrodes, Gold-plated dry EEG electrodes, fNIRS optodes (light sources & detectors) [8] | The physical interface with the subject; transduces biophysical signals (electrical, optical) into electrical signals. |

| Electrode Gel | Electrolytic gel (for wet EEG systems) | Ensures stable electrical conductivity and reduces impedance between the scalp and electrode. |

| Software Development Kits (SDKs) & Toolboxes | OpenBCI, BCI2000, EEGLAB, FieldTrip [3] | Provides open-source platforms for data acquisition, signal processing, stimulus presentation, and system control, accelerating development. |

| Machine Learning Libraries | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Used to build and train custom feature classification and translation algorithms for decoding user intent. |

| Stimulation & Feedback Devices | Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) systems, robotic exoskeletons, VR headsets [10] [7] | Acts as the effector, converting BCI output commands into functional outcomes for rehabilitation or interaction. |

Non-invasive BCIs represent a dynamic and rapidly advancing frontier in neurotechnology. From their origins in the first EEG recordings to the current development of sophisticated, AI-powered systems for rehabilitation and human-computer interaction, the field has consistently grown in capability and impact. The fundamental principles of signal acquisition, processing, and translation provide a stable framework upon which innovation is built. While challenges remain—particularly in improving signal quality and robustness outside laboratory settings—ongoing research in novel sensors like Digital Holographic Imaging, advanced machine learning algorithms, and user-centered training protocols continues to push the boundaries of what is possible [2] [3] [9]. As these technologies mature, they hold immense potential not only to restore lost function but also to augment human capabilities in the years to come.

Core Neurophysiological Signals and Their Biophysical Origins

Understanding the biophysical origins of neurophysiological signals is foundational to the development and refinement of non-invasive Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technologies. These signals, which reflect the brain's electrical and hemodynamic activity, provide the primary data source for decoding human intention and cognitive state [2]. The relationship between underlying neural activity and the signals measured by non-invasive techniques is complex, governed by the principles of electromagnetic biophysics and neurovascular coupling [11] [12]. This guide details the core signals leveraged in non-invasive BCIs, specifically examining the physiological processes that generate them and the methodologies required for their experimental investigation. Framed within a broader review of non-invasive BCIs, this resource is intended for researchers and scientists engaged in developing novel diagnostics, neurotherapeutics, and human-machine interaction paradigms.

Core Neurophysiological Signals and Their Measurement

Non-invasive BCIs primarily interface with the brain through two classes of signals: electrophysiological signals, which measure the brain's electrical activity directly, and hemodynamic signals, which measure metabolic changes coupled to neural activity. The following sections and accompanying tables provide a detailed comparison of these signal modalities.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Electrophysiological Signals in Non-Invasive BCI

| Signal Type | Biophysical Origin | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Primary Measurement Modality | Key BCI Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local Field Potentials (LFPs) | Synaptic and dendritic currents from populations of neurons; believed to correlate with BOLD fMRI signals [11]. | ~0.5 - 1 mm (invasively) | Milliseconds | Invasive recordings (ECoG, Utah Array); inferred non-invasively via modeling [12]. | Fundamental research on neural circuit dynamics; reference for HNN modeling of EEG/MEG [12]. |

| Electroencephalography (EEG) | Superficial cortical synaptic activity; summation of synchronized postsynaptic potentials in pyramidal neurons [2] [12]. | Centimeters | ~1-100 milliseconds [13] | Scalp electrodes (10-20 system); wearable wireless sensors [14] [15]. | Motor imagery, P300 speller, cognitive monitoring, neurorehabilitation [13] [16]. |

| Magnetoencephalography (MEG) | Intracellular currents in pyramidal neurons, which generate magnetic fields perpendicular to the electric field measured by EEG [12]. | ~5-10 mm | ~1-100 milliseconds | Superconducting Quantum Interference Devices (SQUIDs) in magnetically shielded rooms [8]. | Mapping sensory and cognitive processing, clinical epilepsy focus localization. |

Table 2: Comparison of Core Hemodynamic Signals in Non-Invasive BCI

| Signal Type | Biophysical Origin | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Primary Measurement Modality | Key BCI Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) fMRI | Changes in local deoxyhemoglobin concentration driven by neurovascular coupling; a mismatch between cerebral blood flow (CBF) and cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) [11]. | ~1-3 mm | ~1-6 seconds [13] | Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) scanners. | Brain mapping, connectivity studies, and as a benchmark for other hemodynamic modalities. |

| Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) | Hemodynamic response; changes in concentration of oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) in cortical blood vessels [13]. | ~1-3 cm | ~1-5 seconds [13] | Wearable headgear with near-infrared light sources and detectors. | Stroke rehabilitation monitoring, motor imagery, passive BCI for cognitive state assessment [13] [17]. |

Quantitative Signal Characteristics

For researchers designing BCI experiments, understanding the quantifiable features of these signals is critical. The table below summarizes key analytical parameters, with a focus on EEG which offers high temporal resolution for dynamic brain monitoring.

Table 3: Quantitative EEG (qEEG) Parameters for BCI Application

| qEEG Parameter | Frequency Range / Calculation | Physiological Correlation & BCI Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Delta Waves | 0.5 - 4.0 Hz | Associated with deep sleep; increased focal power can indicate cortical dysfunction or lesion; useful for monitoring states of impaired consciousness [13]. |

| Theta Waves | 4 - 7 Hz | Linked to memory and emotional processing; can indicate cognitive load or pathology when prominent in awake adults [13]. |

| Alpha Waves | 8 - 12 Hz | Dominant rhythm in relaxed wakefulness with eyes closed; suppression (desynchronization) indicates cortical activation; power <10% may predict poor functional outcome post-stroke [13]. |

| Beta Waves | 13 - 30 Hz | Associated with active concentration and sensorimotor processing; ERD during motor planning/execution is a common BCI input [13]. |

| Gamma Waves | 30 - 150 Hz | Arises from coordinated neuronal firing during demanding cognitive and motor tasks [13]. |

| Power Ratio Index (PRI) | (Delta + Theta Power) / (Alpha + Beta Power) | An increased PRI is associated with recent stroke and poor functional outcomes, serving as a prognostic biomarker in neurorehabilitation [13]. |

| Brain Symmetry Index (BSI) | Mean absolute difference in hemispheric power spectra (1-25 Hz) [13]. | Quantifies interhemispheric asymmetry; values closer to 0 indicate symmetry (healthy), while higher values indicate stroke-related asymmetry; correlates with NIHSS and motor function scores [13]. |

Experimental Methodologies for Signal Acquisition and Analysis

This section provides detailed protocols for acquiring and analyzing the core neurophysiological signals discussed, ensuring methodological rigor and reproducibility.

Protocol for Multimodal EEG-fNIRS Experimentation

This protocol is adapted from studies investigating motor imagery for post-stroke recovery, allowing for the simultaneous capture of electrophysiological and hemodynamic responses [13] [17].

Participant Preparation and Setup:

- EEG Setup: Position an electrode cap according the international 10-20 system. For extended monitoring, use wireless, wearable EEG sensors to improve comfort and compliance [14]. Ensure electrode impedances are maintained below 5 kΩ for optimal signal quality [15].

- fNIRS Setup: Position fNIRS optodes over the motor cortical areas (e.g., C3 and C4 positions of the 10-20 system). Ensure good scalp contact to maximize signal-to-noise ratio.

- Synchronization: Use a hardware or software trigger to synchronize the clocks of the EEG and fNIRS acquisition systems at the start of the experiment [17] [15].

Experimental Paradigm:

- Resting-State Baseline: Record 5 minutes of data while the participant remains at rest with eyes open, followed by 5 minutes with eyes closed. This provides a baseline for both EEG power spectra and hemoglobin concentrations.

- Task Paradigm: Implement a block or event-related design. For motor imagery, instruct the participant to imagine moving their right hand (e.g., for 10 seconds) without performing any actual movement, followed by a rest period (e.g., 20 seconds). Repeat this for multiple trials (e.g., 30-40 trials) and for other limbs (e.g., left hand, feet) as required.

Signal Pre-processing:

- EEG Pre-processing: Apply a band-pass filter (e.g., 0.5-45 Hz). Remove artifacts using automated algorithms (e.g., for ocular, cardiac, and muscle artifacts) or manual inspection. For qEEG analysis, segment data into epochs and transform into the frequency domain using a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to calculate Power Spectral Density (PSD) [13] [15].

- fNIRS Pre-processing: Convert raw light intensity signals to optical density, then to concentrations of oxygenated (HbO) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) using the modified Beer-Lambert law. Apply a band-pass filter to remove physiological noise (e.g., cardiac pulsation ~1 Hz and respiratory cycles ~0.3 Hz) and slow drifts.

Feature Extraction and Multimodal Analysis:

- Unimodal Features: From EEG, extract features such as band power (Alpha, Beta), PRI, and BSI. From fNIRS, extract features like the mean, slope, and peak of the HbO and HbR responses during tasks [13].

- Multilayer Network Analysis: Construct functional brain networks from both EEG and fNIRS data separately. Then, integrate these networks into a multilayer network model to investigate the complementary information between fast electrophysiological and slow hemodynamic connectivity [17].

Protocol for Computational Modeling of EEG/MEG Generators

The Human Neocortical Neurosolver (HNN) provides a method to infer the cellular and network origins of macroscale EEG/MEG signals [12].

Tool Installation and Data Preparation:

- Install HNN software from the public website (https://hnn.brown.edu).

- Prepare the empirical EEG/MEG data. This should be source-localized data representing the current dipole moment over time in ampere-meters (Am) for a specific cortical area.

Forward Model Simulation:

- Input the empirical data into HNN's graphical interface.

- The software's forward model, based on a canonical neocortical circuit, will simulate the primary currents (Jp) generated by intracellular current flow in the dendrites of pyramidal neurons. These currents are the elementary generators of the EEG/MEG signal [12].

Hypothesis Testing and Parameter Manipulation:

- Manipulate model parameters to test hypotheses about the neural circuit dynamics underlying the observed signal. Parameters can include the timing and strength of layer-specific inputs (e.g., thalamocortical inputs), synaptic conductances, and cellular properties.

- Compare the simulated net current dipole output from the model directly with the source-localized empirical data.

Microscale Interpretation:

- Use the model's visualization of microscale features—such as layer-specific local field potentials, individual cell spiking, and somatic voltages—to interpret the circuit-level activity (e.g., the balance of excitation and inhibition) that likely generated the macroscopic signal [12].

Diagram 1: Multimodal EEG-fNIRS experimental workflow for motor imagery tasks, showing parallel processing of electrophysiological and hemodynamic signals.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table catalogues critical hardware, software, and analytical tools required for experimental research in non-invasive BCI.

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Non-Invasive BCI Development

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| EEG Recording System | Acquisition of electrophysiological signals from the scalp. | Includes amplifier (e.g., 32-256 channel), electrode cap (10-20 system), and conductive gel. Systems from companies like TMSI or Brain Products [15]. |

| Wireless/Wearable EEG Sensors | Enables extended-duration, ambulatory EEG monitoring in real-world environments. | Miniaturized, dry-electrode sensors (e.g., REMI sensor), offering high patient acceptance and comfort for long-term use [14]. |

| fNIRS System | Acquisition of hemodynamic signals by measuring cortical oxygenation. | Wearable headgear containing near-infrared light sources and detectors. Offers portability and resistance to motion artifacts compared to fMRI [13]. |

| Multimodal Data Acquisition Software | Synchronized recording from multiple physiological modalities (EEG, fNIRS, ECG, GSR). | Software suites like Neurolab (Bitbrain) enable hardware synchronization for temporal alignment of different data streams [15]. |

| Human Neocortical Neurosolver (HNN) | Open-source software for interpreting the cellular and network origin of human EEG/MEG data. | Uses a biophysical model of a canonical neocortical circuit to simulate current dipoles; allows hypothesis testing without coding [12]. |

| Quantitative EEG (qEEG) Parameters | Analytical metrics for assessing brain state and pathology. | Power Spectral Density (PSD), Power Ratio Index (PRI), Brain Symmetry Index (BSI). Critical for prognostication in stroke and neurorehabilitation [13]. |

Diagram 2: Signaling pathway of the hemodynamic response measured by BOLD-fMRI and fNIRS, showing the relationship between neural activity, neurovascular coupling, and the resulting metabolic changes.

Electroencephalography (EEG), marking its centenary in 2024, remains a fundamental tool for studying human neurophysiology and cognition due to its direct measurement of neuronal activity at millisecond resolution, comparably low cost, and ease of access for multi-site studies [18]. In the specific context of clinical trials for drug development, minimizing patient and clinical site burden is paramount, as lengthy, strenuous site visits can lead to inferior data quality and patient drop-out [18]. Traditional wet-electrode EEG, while considered the gold standard, adds to this burden: electrodes require careful placement with conductive paste, followed by time-consuming cleanup for both patients and staff [18] [19]. These limitations have catalyzed the development and adoption of dry-electrode EEG systems, which operate without conductive gel or complex skin preparation [19]. This transition is a critical component within the broader review of non-invasive Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technologies, balancing the imperative for high-quality data with the practical needs of modern clinical and research environments. The goal is to provide a comprehensive, technical guide to these innovations, focusing on their performance, applications, and implementation protocols for research scientists and drug development professionals.

Technical Comparison of Electrode Technologies

The core of EEG innovation lies in electrode technology, which acts as the transducer converting the body's ionic currents into electronically processable signals. The choice between wet, dry, and emerging soft electrodes involves a careful trade-off between signal quality, patient comfort, and operational efficiency.

Table 1: Qualitative Comparison of EEG Electrode Types

| Feature | Wet Electrodes | Dry Electrodes | Soft Electrodes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Quality | Strong signal, reliable benchmark [20] | Good, but lower signal correlation possible; susceptible to motion artifacts [20] | Varies with material and manufacturing; stable contact can improve quality [20] |

| Setup Time | Lengthy (requires gel application) [20] | Rapid [18] [20] | Moderate to Rapid [20] |

| Patient Comfort | Discomfort from gel, scalp irritation, messy cleanup [20] | No gel discomfort; can be uncomfortable for long periods [18] [20] | High comfort for extended use, biocompatible [20] |

| Long-Term Recording | Poor (gel dries, altering impedance) [20] | Good (no gel to dry) [21] | Excellent (flexible, conforms to skin) [20] |

| Key Advantage | Established, reliable technology [20] | Speed and ease of use [18] | Biocompatibility and comfort for wearables [20] |

| Primary Limitation | Gel drying affects signal stability; messy [20] | Higher impedance; performance affected by hair and motion [20] | High cost; experimental, limited validation [20] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Benchmark from a Clinical Trial Context (2025) [18]

| Device Type | Median Set-up Time (mins) | Median Clean-up Time (mins) | Technician Ease of Set-up (0-10, 10=best) | Technician Ease of Clean-up (0-10, 10=best) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Wet EEG | ~20 | ~10 | 7 | 5 |

| Dry-EEG (DSI-24) | ~10 | ~2 | 9 | 9 |

| Dry-EEG (Quick-20r) | ~15 | ~2 | 7 | 9 |

| Dry-EEG (zEEG) | ~15 | ~2 | 7 | 9 |

Dry Electrode Structural Classifications

Dry electrodes can be further categorized based on their structural design and operating principle, which directly impact their performance and suitability for different applications [19]:

- MEMS Dry Electrodes: Utilize micro-needle arrays to gently penetrate the outermost skin layer (stratum corneum) to reduce contact impedance. Materials include silicon (brittle, being phased out), metals, and polymers like PDMS or SU-8 coated with conductive metals (e.g., Gold, Silver) for flexibility and biocompatibility [19].

- Dry Contact Electrodes: Maintain direct contact with the scalp without penetration. They rely on structural designs (e.g., spring-loaded, finger-like) to maintain stable contact, often through hair. Their performance is highly dependent on achieving and maintaining low impedance [19].

- Dry Non-Contact Electrodes: Operate without direct galvanic contact with the skin, measuring capacitive coupling. This eliminates friction and pressure, enhancing comfort, but the signal is more susceptible to environmental noise and motion artifacts [19].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies for Validation

Rigorous, clinical trial-oriented benchmarking is essential for validating dry-electrode EEG systems. The following methodology, drawn from a recent 2025 study, provides a template for robust comparison [18].

Study Design and Participant Profile

- Objective: To comprehensively compare state-of-the-art dry-electrode EEG devices against a standard wet EEG in a setting that emulates clinical trials as closely as possible.

- Participants: A cohort of n=32 healthy participants is typical for such studies, completing multiple recording days to account for intra- and inter-subject variability.

- Setting: Experiments are performed at a clinical testing site routinely used for early drug development (e.g., Phase 1 & 2 trials) by trained personnel experienced with EEG and clinical trials.

Devices and Montage

- Benchmark Device: A standard wet-EEG system (e.g., QuikCap Neo Net with a Grael amplifier) serving as the gold standard. The montage may include the international 10-20 system plus additional electrodes for comprehensive analysis.

- Dry-Electrode Devices: Three commercially available dry-EEG devices (e.g., DSI-24 from Wearable Sensing, Quick-20R from CGX, zEEG from Zeto) are evaluated. These typically cover the standard 10-20 montage. To ensure a fair comparison, the wet-EEG data can be synthetically subsampled to the 10-20 locations matching the dry devices before preprocessing.

Experimental Tasks and Data Acquisition

The EEG recordings should focus on tasks with biomarker relevance for early clinical trials, including:

- Resting-State Recordings: Eyes-open and eyes-closed conditions to capture baseline brain activity.

- Event-Related Potentials (ERPs): Such as the P300 evoked potential, often used in cognitive assessment.

- Other Task-Related Activity: Auditory and visually driven paradigms to assess various cognitive domains.

Quantitative and Qualitative Metrics

Data collection should encompass both operational and subjective metrics:

- Operational Burden:

- Set-up Time: Measured from start of preparation to start of EEG recording.

- Clean-up Time: Measured from end of recording to a fully cleaned set-up.

- Technician Feedback: Structured questionnaires rating ease of set-up and clean-up on a scale (e.g., 0-10).

- Participant Feedback: Repeated ratings of perceived comfort during the recording to track temporal evolution.

- Signal Quality: Quantitative analysis of the EEG data, including:

- Resting-state quantitative EEG (qEEG)

- ERP amplitude and latency (e.g., P300)

- Power spectral density across frequency bands (e.g., low frequency <6 Hz, induced gamma 40-80 Hz)

Performance Analysis and Application-Specific Utility

The validation of dry-electrode EEG reveals a nuanced performance profile, where utility is highly dependent on the specific application and signal type.

Key Findings from Clinical Benchmarking

The 2025 benchmarking study yielded several critical insights [18]:

- Operational Efficiency: Dry-electrode EEG significantly speeds up experiments. All tested dry devices were faster to set up and clean up than the standard wet EEG, with the fastest device (DSI-24) cutting set-up time by half. Technicians also found dry electrodes easier to work with [18].

- Participant Comfort: Standard wet EEG emerged as the overall most comfortable option, a level that dry-electrode EEG could only match at best. Comfort scores for all devices showed a declining trend over time [18].

- Variable Signal Performance: The quantitative performance of dry-electrode EEG varied strongly across applications. Key findings included:

- Adequate Performance: Quantitative resting-state EEG and P300 evoked activity were adequately captured by dry-electrode EEG, making them suitable for trials where these are primary biomarkers.

- Notable Challenges: Certain signal aspects, such as low-frequency activity (<6 Hz) and induced gamma activity (40–80 Hz), presented significant challenges for the tested dry-electrode systems.

Application in BCI and Neurotechnology

Beyond clinical trials, dry-electrode EEG is a cornerstone of non-invasive BCIs. Its utility spans several domains, bolstered by advances in artificial intelligence for signal processing [19]:

- Emotion Recognition: Using algorithms to classify brainwave patterns associated with different affective states.

- Fatigue and Drowsiness Detection: Monitoring shifts in brain activity indicative of reduced alertness.

- Motor Imagery: Decoding the intention to move a limb, which can be used for prosthetic control or rehabilitation.

- Steady-State Visual Evoked Potentials (SSVEPs): Detecting responses to visual stimuli at specific frequencies, often used for high-speed spelling applications.

Table 3: Dry-Electrode EEG Performance in Key BCI Applications [19]

| BCI Application | Typical Paradigm | Key Signal Features | Dry-EEG Suitability & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion Recognition | Presentation of affective stimuli | Changes in frontal alpha/beta asymmetry; spectral power | Suitable; relies heavily on AI/ML for pattern classification from often noisy signals. |

| Fatigue Detection | Prolonged, monotonous tasks | Increase in theta power, decrease in alpha power | Suitable for longitudinal monitoring; a key advantage of dry systems is long-term wearability. |

| Motor Imagery (MI) | Imagination of limb movement | Event-Related Desynchronization (ERD) in mu/beta rhythms | Moderately suitable; ERD can be obscured by noise, requiring robust preprocessing. |

| P300 ERP | Oddball paradigm | Positive deflection ~300ms post-stimulus | Highly Suitable; consistently shown to be adequately captured by dry EEG systems [18]. |

| SSVEP | Flickering visual stimuli | Oscillatory EEG response at stimulus frequency | Suitable; strong, frequency-specific signals can be reliably detected with dry systems. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers designing experiments involving dry-electrode EEG, a set of key materials and technologies is essential.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Dry-EEG Research

| Item Category | Specific Examples / Models | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Dry-EEG Systems | DSI-24 (Wearable Sensing), Quick-20r (CGX), zEEG (Zeto [18] | Primary Data Acquisition: Commercially available systems validated for research and clinical trials. Offer a balance of channel count, portability, and software support. |

| Benchmark Wet-EEG | QuikCap Neo Net with Grael amplifier (Compumedics) [18] | Gold Standard Control: Essential for validating the signal quality and performance of any dry-electrode system in a comparative study. |

| Electrode Materials | Gold (Au), Silver (Ag), Silver/Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl), Conductive Polymers [20] [19] | Signal Transduction: Material choice impacts impedance, biocompatibility, and long-term stability. Ag/AgCl is a common wet reference; Au and polymers are common for dry. |

| Flexible Substrates | Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), Polyimide, Graphene [20] [19] | Conformability & Comfort: Used in "soft" and MEMS electrodes to create flexible, comfortable interfaces that maintain good contact with the scalp. |

| Data Processing Tools | Machine Learning (ML) & Deep Learning (DL) Algorithms (e.g., for classification, regression) [19] | Signal Enhancement & Decoding: Critical for improving the signal-to-noise ratio of dry-EEG and translating brain signals into actionable commands for BCI. |

| Validation Tasks | P300 Oddball, Resting State, Motor Imagery, SSVEP Paradigms [18] [19] | Functional Benchmarking: Standardized experimental protocols to objectively test and compare the performance of different EEG systems. |

The transition from wet to dry electrodes in EEG represents a significant advancement in neurotechnology, particularly for applications demanding low burden and high usability, such as clinical trials and non-invasive BCIs. Evidence from rigorous, clinically-oriented studies demonstrates that dry-electrode EEG can substantially reduce operational time and technician effort while maintaining adequate data quality for a range of applications, including resting-state qEEG and P300 evoked potentials [18]. However, the technology is not a panacea; challenges remain with specific signal types like low-frequency and gamma activity, and patient comfort can be variable [18]. The future of dry-EEG development lies in the coordinated optimization of hardware—through novel materials like graphene and advanced polymer-based MEMS—and sophisticated AI-driven algorithms that can mitigate signal quality issues [19]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the key takeaway is that dry-electrode EEG is a viable and powerful tool, but its successful deployment requires careful matching of the device's capabilities to the specific context of use.

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) and Hemodynamic Monitoring

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) is a non-invasive optical neuroimaging technique that enables continuous monitoring of brain function by measuring hemodynamic changes associated with neuronal activity [22]. As a brain-computer interface (BCI) technology, fNIRS offers a unique combination of portability, safety, and moderate spatiotemporal resolution, making it particularly valuable for both clinical and research applications [23] [24]. The core principle of fNIRS relies on tracking neurovascular coupling—the rapid delivery of blood to active neuronal tissue—through quantifying relative concentration changes in oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin [25]. This technical guide examines the fundamental mechanisms, methodological approaches, and implementation protocols of fNIRS-based hemodynamic monitoring within the broader context of non-invasive BCI technologies.

Fundamental Principles of fNIRS

Physiological Basis: Neurovascular Coupling

The foundation of fNIRS rests on neurovascular coupling, the physiological process linking neuronal activation to cerebral hemodynamic changes [24]. When a specific brain region becomes active, the increased neuronal firing rate elevates metabolic demands for oxygen and glucose [24]. This triggers a complex cerebrovascular response:

- Initial oxygen consumption: The sudden increase in neuronal activity causes a brief rise in oxygen utilization, leading to a slight initial increase in deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) [26].

- Hemodynamic response: Within 2-5 seconds, cerebral autoregulatory mechanisms trigger localized vasodilation, significantly increasing cerebral blood flow (CBF) to the active region [24].

- Blood oxygenation changes: This increased blood flow delivers oxygen in excess of metabolic demand, resulting in a characteristic increase in oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) and a concurrent decrease in deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) in the venous capillaries [22] [24].

- Return to baseline: After stimulus cessation, hemodynamic parameters gradually return to baseline over 10-15 seconds [26].

This hemodynamic response forms the basis for fNIRS signal detection, with HbO typically demonstrating more pronounced concentration changes than HbR during neuronal activation [23].

Optical Principles and the Modified Beer-Lambert Law

fNIRS utilizes near-infrared light (650-1000 nm wavelength) because biological tissues (skin, skull, dura) demonstrate relatively high transparency in this spectral window, while hemoglobin compounds show distinct absorption characteristics [22] [27]. Within this range, light absorption by water is minimal, while HbO and HbR serve as the primary chromophores (light-absorbing molecules) [24].

The relationship between light attenuation and chromophore concentration is governed by the Modified Beer-Lambert Law [22] [27]:

[ OD = \log\left(\frac{I_0}{I}\right) = \varepsilon \cdot c \cdot d \cdot DPF + G ]

Where:

- (OD) = Optical density

- (I_0) = Incident light intensity

- (I) = Detected light intensity

- (\varepsilon) = Extinction coefficient of chromophore

- (c) = Chromophore concentration

- (d) = Distance between source and detector

- (DPF) = Differential pathlength factor

- (G) = Geometry-dependent factor

By emitting light at multiple wavelengths and measuring attenuation, fNIRS calculates relative concentration changes of HbO and HbR based on their distinct absorption spectra [27]. Below 800 nm, HbR has a higher absorption coefficient, while above 800 nm, HbO is more strongly absorbed [24].

Figure 1: Neurovascular Coupling Pathway. This diagram illustrates the physiological sequence from neuronal activation to detectable fNIRS signals.

fNIRS Instrumentation and Technology

System Components and Configuration

A typical fNIRS system consists of several integrated components that work in concert to generate, transmit, detect, and process near-infrared light [27]:

Light Sources generate near-infrared light at specific wavelengths, typically between 650-1000 nm [22]. Two primary technologies are employed:

- Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs): Offer advantages in portability, power efficiency, and cost-effectiveness, suitable for most applications with penetration depths up to 2 cm [27].

- Laser Diodes: Provide higher intensity, monochromaticity, and directionality, enabling deeper penetration (up to 3 cm) but often requiring optical fibers and more complex instrumentation [27].

Detectors capture photons that have traversed brain tissue. Common detector types include:

- Pin Photodetectors (PDs): Simple, portable, and low-power but lack internal gain mechanisms [27].

- Avalanche Photodiodes (APDs): Feature internal gain (10 to few 100×), higher sensitivity, and faster response than PDs [27].

- Photomultiplier Tubes (PMTs): Offer extremely high gain (up to 10⁷) and sensitivity but require high voltage supplies and cooling systems, limiting portability [27].

Optical Probes arrange sources and detectors in specific geometries on the scalp. The distance between sources and detectors (typically 3-5 cm) determines penetration depth and spatial resolution [22] [24]. Flexible caps, headbands, or rigid grids maintain proper optode positioning and skin contact.

Data Acquisition System controls light source modulation, synchronizes detection, amplifies signals, and converts analog measurements to digital format for analysis [27].

fNIRS System Types

Three primary fNIRS system architectures have been developed, each with distinct operational principles and applications [24]:

Table 1: fNIRS System Types and Characteristics

| System Type | Operating Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Wave (CW) | Measures light intensity attenuation | Simple, portable, cost-effective, most common | Cannot measure absolute pathlength or concentration | Most BCI and clinical applications [24] |

| Frequency Domain (FD) | Modulates light intensity at radio frequencies; measures amplitude decay and phase shift | Can resolve absorption and scattering coefficients; provides pathlength measurement | More complex and expensive than CW systems | Tissue oxygenation monitoring, quantitative studies [24] |

| Time Domain (TD) | Uses short light pulses; measures temporal point spread function | Highest information content; separates absorption and scattering | Most complex, expensive, and bulky | Research requiring depth resolution [24] |

fNIRS Signal Processing and Analysis

Standard Processing Pipeline

fNIRS data processing follows a structured pipeline to extract meaningful hemodynamic information from raw light intensity measurements [22] [23]:

Figure 2: fNIRS-BCI Signal Processing Workflow. This diagram outlines the standard sequence from raw signal acquisition to interpretable output.

Preprocessing Methods

Preprocessing aims to remove artifacts and enhance signal quality through several approaches:

- Band-pass filtering: Removes physiological noise (cardiac ~1 Hz, respiratory ~0.3 Hz) and very low-frequency drift [23].

- Adaptive filtering: Effectively separates cerebral signals from systemic physiological interference [23].

- Independent Component Analysis (ICA): Identifies and removes artifacts based on statistical independence [23].

- Motion artifact correction: Algorithms specifically designed to identify and compensate for movement-induced signal distortions [25].

Feature Extraction and Classification

For BCI applications, processed hemodynamic signals are converted into discriminative features for classification:

Common Feature Types [23]:

- Mean, peak value, variance of HbO/HbR responses

- Signal slope during initial rise/fall phases

- Higher-order statistics (skewness, kurtosis)

- Waveform morphology parameters

Classification Algorithms [23]:

- Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA): Simple, computationally efficient, provides good performance for many fNIRS-BCI tasks

- Support Vector Machines (SVM): Effective for non-linear classification problems

- Hidden Markov Models (HMM): Captures temporal dynamics of hemodynamic responses

- Artificial Neural Networks: Powerful for complex pattern recognition with sufficient training data

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol Design Considerations

Well-designed experimental protocols are essential for obtaining reliable fNIRS data. Key considerations include:

Paradigm Selection:

- Block design: Alternating periods of task and rest (typically 20-30s each); provides robust signals suitable for initial studies [26].

- Event-related design: Brief, randomized stimuli; allows examination of hemodynamic response shape and timing [26].

- Mixed designs: Combine elements of both block and event-related approaches.

Task Selection Based on Target Brain Regions:

- Prefrontal cortex: Mental arithmetic, working memory tasks, emotional induction, music imagery [23].

- Motor cortex: Motor execution or imagery of limb movements, finger tapping sequences [23].

- Visual cortex: Pattern recognition, visual stimulation tasks.

Standardized Experimental Procedure

A typical fNIRS experiment follows this sequence:

Participant Preparation (10-15 minutes):

- Explain procedure and obtain informed consent

- Measure head circumference and mark fiducial points (nasion, inion, pre-auricular points)

- Position fNIRS cap or probe set according to international 10-20 system or specific cortical landmarks

- Verify signal quality at all channels

Baseline Recording (5-10 minutes):

- Record resting-state activity with eyes open or closed

- Establish individual hemodynamic baseline values

Task Execution (variable, typically 30-60 minutes total):

- Present task instructions and practice trials

- Conduct experimental runs with appropriate rest periods between blocks

- Monitor signal quality throughout session

- Record behavioral performance data synchronized with fNIRS acquisition

Post-experiment Procedures (5 minutes):

- Document probe locations with digital photography or 3D digitization

- Remove equipment and debrief participant

Quality Control Measures

- Signal Quality Assessment: Verify adequate signal-to-noise ratio (>10 dB typically acceptable) [27]

- Motion Artifact Identification: Visual inspection and algorithmic detection of movement-related signal distortions [25]

- Physiological Monitoring: Simultaneous recording of heart rate and respiration can aid artifact rejection [23]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials and Equipment for fNIRS Research

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| fNIRS Instrumentation | Continuous Wave systems (e.g., Hitachi ETG series, NIRx NIRScout) | Generate and detect NIR light; core measurement platform | Channel count, sampling rate, portability, compatibility with auxiliary systems [22] |

| Optical Components | LED/laser sources (690nm, 830nm typical), silicon photodiodes/APDs, fiber optic bundles | Light generation, transmission, and detection | Wavelength options, source intensity, detector sensitivity, fiber flexibility [27] |

| Probe Design Materials | Flexible silicone optode holders, spring-loaded probes, 3D-printed mounts | Maintain optode-scalp contact and positioning geometry | Probe density, customization capability, stability during movement [22] |

| Auxiliary Monitoring | ECG electrodes, respiratory belt, motion capture systems | Record physiological signals for noise regression and artifact correction | Synchronization capability, sampling rate, compatibility with fNIRS system [23] |

| Data Analysis Software | Homer2, NIRS-KIT, MNE-NIRS, custom MATLAB/Python scripts | Signal processing, statistical analysis, visualization | Processing pipeline flexibility, supported algorithms, visualization capabilities [23] |

| Head Localization | 3D digitizers (Polhemus), photogrammetry systems | Precisely document optode positions relative to head landmarks | Accuracy, measurement time, integration with analysis software [23] |

Comparative Analysis with Other Non-Invasive BCIs

Technical Benchmarking

fNIRS occupies a distinct position in the landscape of non-invasive neural monitoring technologies, offering complementary advantages and limitations compared to other modalities:

Table 3: Comparison of Non-Invasive Brain Monitoring Technologies for BCI Applications

| Parameter | fNIRS | EEG | fMRI | MEG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | 1-3 cm (moderate) [24] | 1-10 cm (poor) [2] | 1-5 mm (high) [24] | 3-10 mm (high) [8] |

| Temporal Resolution | 0.1-1 second (moderate) [24] | <100 ms (excellent) [2] | 1-3 seconds (poor) [24] | <10 ms (excellent) [8] |

| Penetration Depth | Cortical surface (2-3 cm) [27] | Cortical surface | Whole brain | Cortical surface |

| Portability | High [24] [25] | Moderate to high [2] | None (fixed system) | Limited (shielded room) [8] |

| Tolerance to Movement | Moderate [25] | Low (highly motion-sensitive) | Very low | Very low |

| Signal Origin | Hemodynamic (metabolic) | Electrical (neuronal) | Hemodynamic (metabolic) | Magnetic (neuronal) |

| Primary Artifacts | Physiological noise, motion | Ocular/muscular, line noise, motion | Motion, physiological noise | Environmental magnetic fields |

| Cost | Moderate [25] | Low to moderate | Very high | Very high |

Hybrid Approaches: fNIRS-EEG Integration

Combining fNIRS with EEG creates a powerful multimodal platform that captures both hemodynamic and electrophysiological aspects of brain activity simultaneously [23] [27]. This integration offers several advantages:

- Complementary Information: fNIRS provides better spatial localization of cortical activation, while EEG offers superior temporal resolution of neural dynamics [23].

- Artifact Reduction: fNIRS signals can help identify and remove physiological artifacts in EEG data [23].

- Enhanced Classification Accuracy: Combined features often improve BCI performance over either modality alone [23].

- Comprehensive Neurovascular Assessment: Enables investigation of relationships between electrical brain activity and hemodynamic responses [26].

Technical implementation requires careful synchronization of acquisition systems, compatible probe designs that accommodate both modalities, and integrated data analysis approaches [23].

Applications in Clinical and Research Settings

Neurological Rehabilitation

fNIRS has demonstrated significant utility in monitoring and guiding neurorehabilitation:

- Stroke Recovery: Tracking cortical reorganization during motor and cognitive rehabilitation; identifying compensatory activation patterns in ipsilateral hemispheres [24].

- Spinal Cord Injury: Providing alternative control pathways through BCI-based neurofeedback training; showing potential to improve motor function, sensory function, and activities of daily living [10].

- Cognitive Training: Real-time monitoring of prefrontal cortex activity during working memory and executive function tasks [25].

BCI Communication and Control

fNIRS-BCIs offer communication pathways for severely paralyzed patients:

- Binary Communication: Using mental arithmetic, motor imagery, or other cognitive tasks to encode "yes/no" responses [23].

- Advanced Control: Operating assistive devices, wheelchairs, or neuroprostheses through pattern classification of hemodynamic responses [22] [10].

- Commercial Integration: Recent developments enable direct BCI control of consumer devices (e.g., Apple's BCI Human Interface Device profile) [28].

Current Limitations and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, fNIRS technology faces several challenges that guide ongoing research and development:

Technical Limitations

- Depth Sensitivity: Limited to cortical surfaces (typically <3 cm), unable to access subcortical structures [22].

- Spatial Resolution: Inferior to fMRI due to photon scattering in biological tissues [24].

- Physiological Contamination: Systemic physiological changes (blood pressure, heart rate, respiration) can confound cerebral signals [23].

- Individual Anatomical Variability: Skull thickness, cerebrospinal fluid distribution, and other anatomical factors affect light propagation [22].

Emerging Innovations

- High-Density Arrays: Denser optode arrangements enabling tomographic reconstruction and improved spatial resolution [22].

- Wearable Platforms: Fully portable, wireless systems for naturalistic monitoring outside laboratory environments [25].

- Advanced Analysis Methods: Machine learning and deep learning approaches for improved pattern recognition and classification [27].

- Miniaturized Hardware: Integration with wearable electronics and consumer-grade head-mounted devices [28] [8].

- Hybrid Neuroimaging: Continued development of integrated fNIRS-EEG and fNIRS-fMRI platforms for comprehensive brain monitoring [23] [27].

The future trajectory of fNIRS points toward more accessible, robust, and clinically integrated systems that leverage technological advancements in photonics, materials science, and artificial intelligence to expand our understanding of brain function and enhance BCI applications across diverse settings.

Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technology is undergoing a significant transformation, driven by the demand for high-performance non-invasive systems. While established methods like electroencephalography (EEG) are widely used, their applications are often limited by spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio [29]. Emerging modalities are challenging these limitations, offering new pathways to decode neural activity without surgical implants. Two technologies at the forefront of this innovation are wearable Magnetoencephalography (MEG) and Digital Holographic Imaging (DHI). Wearable MEG, leveraging quantum-derived optical pumping, enables unshielded neural recording, while DHI detects nanoscale neural tissue deformations, representing a novel signal class for BCI [9] [30]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of these two modalities, detailing their operating principles, experimental protocols, and comparative standing within the non-invasive BCI landscape, serving as a resource for researchers and drug development professionals.

Wearable Magnetoencephalography (MEG)

Traditional MEG systems are cryogenically cooled and require bulky magnetic shielding, confining their use to controlled laboratory settings [30]. Wearable MEG systems overcome these limitations through Optically Pumped Magnetometers (OPMs). OPMs are compact, highly sensitive magnetic field sensors that operate at room temperature. Their principle is grounded in atomic physics: a vapor cell containing alkali atoms (e.g., Rubidium) is optically pumped with a laser to polarize the atomic spins. When the weak magnetic fields produced by neuronal currents in the brain interact with this polarized ensemble, they cause a measurable change in the atoms' quantum spin state, which is probed by a second laser [30]. This allows for direct detection of neuromagnetic signals with a sensitivity comparable to traditional MEG but with a form factor that enables sensor placement directly on the scalp in a wearable helmet or headset.

Digital Holographic Imaging (DHI)

In contrast to measuring magnetic fields or electrical potentials, DHI detects a fundamentally different physiological correlate of neural activity: nanoscale mechanical deformations of neural tissue that occur during neuronal firing. Researchers at Johns Hopkins APL have developed a DHI system that functions as a remote sensing tool for the brain [9] [31]. The system actively illuminates neural tissue with a laser and records the scattered light on a specialized camera to form a complex image. By analyzing the phase information of this light with nanometer-scale sensitivity, the system can spatially resolve minute changes in brain tissue velocity correlated with action potentials [9]. This approach treats the brain as a complex, cluttered environment where the target signal—neural tissue deformation—must be isolated from physiological noise such as blood flow and respiration.

Quantitative Data and Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for emerging non-invasive BCI modalities alongside established technologies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Non-Invasive BCI Modalities

| Technology | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Penetration Depth | Key Measured Signal | Form Factor & Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wearable MEG (OPM-based) | High (Sub-centimeter) [30] | High (Milliseconds) [30] | Whole Cortex [30] | Magnetic fields from neuronal currents [30] | Wearable helmet; Unshielded operation [30] |

| Digital Holographic Imaging (DHI) | High (Potential for micron-scale) [9] | High (Milliseconds) [9] | Superficial cortical layers (initially) [9] | Nanoscale tissue deformation from neural activity [9] | Bench-top system; Novel signal source & measures intracranial pressure [9] [31] |

| EEG | Low (Several centimeters) [29] | High (Milliseconds) [29] | Whole Cortex [29] | Scalp electrical potentials [29] | Wearable cap; Established & portable [29] |

| fNIRS | Low (1-2 cm) [30] | Low (Seconds) [30] | Superficial cortical layers [30] | Hemodynamic response (blood oxygenation) [30] | Wearable headband; Tracks hemodynamics [30] |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Emerging BCI Modalities

| Item | Function in Research | Specific Example / Technology |

|---|---|---|

| Alkali Vapor Cell | Core sensing element of an OPM; its quantum spin state is altered by neuromagnetic fields. | Rubidium-87 vapor cell in wearable MEG systems [30]. |

| Narrow-Linewidth Laser Diode | Used for optical pumping and probing of the atomic spins in OPMs. | Tuneable laser source for OPM-MEG [30]. |

| Digital Holographic Camera | Records complex wavefront (amplitude and phase) of laser light scattered from neural tissue. | Specialized camera used in Johns Hopkins APL DHI system [9]. |

| Low-Coherence Laser Illuminator | Provides the coherent light source required for holographic interferometry in DHI. | Laser illuminator in the DHI system [9]. |

| Real-Time Signal Processing Unit | Hardware/Software for filtering physiological clutter and extracting neural signals. | Custom software for separating neural tissue velocity from heart rate and blood flow [9] [31]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Wearable MEG with OPMs

This protocol outlines the procedure for conducting a motor imagery task using a wearable MEG system.

A. Materials and Setup

- OPM Sensor Array: A helmet or headset integrated with multiple OPM sensors (e.g., based on Rubidium vapor cells).

- Biomagnetic Shielding: While OPMs enable operation in less shielded environments, a compact, active magnetic shielding system is often used for improved signal quality.

- Data Acquisition (DAQ) System: A multi-channel system synchronized to the OPM controls.

- Stimulus Presentation Interface: A monitor or set of headphones to deliver cues to the participant.

- Participant Preparation: The participant dons the wearable MEG helmet. No skin preparation or conductive gel is required. Sensor positions are co-registered with the participant's head anatomy using a digitizer or built-in cameras.

B. Procedure

- System Calibration: The OPM sensors are activated and calibrated. This involves tuning the laser frequencies and magnetic fields to the operating point of the vapor cells for maximum sensitivity.

- Baseline Recording (5 minutes): The participant is instructed to relax with their eyes open, followed by eyes closed, to record a baseline of brain activity and environmental noise.

- Task Execution:

- The participant is seated comfortably and presented with a visual cue (e.g., an arrow pointing left or right) on the stimulus interface.

- Upon seeing the cue, the participant is instructed to imagine moving the corresponding hand (e.g., clenching their left or right fist) without performing any actual movement. Each imagery trial lasts for 4 seconds, followed by a rest period.

- A block of 60-100 trials (30-50 per hand) is performed.

- Data Acquisition: Throughout the task, the DAQ system continuously records the magnetic field data from all OPM channels, time-locked to the task cues.

C. Data Analysis

- Pre-processing: Data is filtered (e.g., 1-40 Hz bandpass) to remove low-frequency drift and high-frequency noise. Artifact rejection algorithms are applied to remove contamination from eye blinks and muscle movement.

- Source Modeling: The cleaned sensor-level data is projected onto a cortical source model derived from an MRI of the participant's brain. This reconstructs the originating neural currents.

- Feature Extraction & Classification: Event-Related Desynchronization (ERD) in the mu (8-12 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) frequency bands over the motor cortex is extracted for each trial. A machine learning classifier (e.g., Support Vector Machine) is trained to distinguish between left- and right-hand motor imagery based on these features.

Wearable MEG Experimental Workflow

Protocol for Validating DHI Neural Signals

This protocol describes the core experimental methodology, initially validated in animal models, to confirm that DHI signals are correlated with neural activity.

A. Materials and Setup

- Digital Holographic Imaging System: Comprising a low-coherence laser illuminator, a high-speed camera capable of recording phase information, and a computer for hologram reconstruction.

- In Vivo Cranial Window Preparation: A surgically implanted transparent window into the skull of an anesthetized animal model (e.g., mouse) to provide optical access to the cortex.

- Electrophysiology Setup: A multi-electrode array (MEA) or patch-clamp electrode for simultaneous electrical recording of neural activity (the "gold standard").

- Stimulus Delivery System: Equipment for controlled sensory or electrical stimulation (e.g., a current stimulator for the whisker pad or a foot shock).

B. Procedure

- Surgical Preparation: An animal model is anesthetized, and a cranial window is surgically prepared over the target brain region (e.g., somatosensory cortex).

- System Alignment: The DHI system is aligned to illuminate the cortical tissue through the cranial window. The electrophysiology electrode is positioned to record from the same region.

- Co-registered Recording:

- A controlled stimulus (e.g., a mild electrical pulse to the whisker pad) is administered.

- Simultaneously, the DHI system records a high-speed video sequence of the laser light scattered from the brain tissue.

- The MEA records the resulting electrical neural activity (action potentials and local field potentials).

- Data Collection: This co-registered recording is repeated over hundreds of trials to build a robust dataset for correlation analysis.

C. Data Analysis

- Hologram Processing: The recorded holographic video is processed to reconstruct complex wavefronts, from which nanometer-scale displacements of the tissue over time are calculated, producing a "tissue velocity" map.

- Signal Correlation:

- The timing of the DHI-derived tissue deformation signal is precisely aligned with the electrophysiology recording.

- Cross-correlation analysis is performed between the tissue velocity and the multi-unit activity or local field potential from the MEA.

- A strong, consistent temporal correlation between the electrical spiking and the tissue deformation validates the DHI signal as a proxy for neural activity [9].

DHI Signal Validation Workflow

Current Research Status and Future Trajectory

Wearable MEG

Wearable MEG is transitioning from proof-of-concept demonstrations to application in basic neuroscience and clinical research. The current focus is on improving sensor miniaturization, robustness against environmental interference, and developing algorithms for motion correction and source localization in a dynamic, wearable setting [30]. The modality's ability to provide high-fidelity neural data in unshielded environments positions it as a strong candidate for studying brain network dynamics in naturalistic postures and for long-term monitoring of neurological conditions.

Digital Holographic Imaging

DHI is at an earlier stage of development, with the foundational research successfully demonstrating the detection of a novel neural signal in animal models [9]. The immediate research priority, as stated by the Johns Hopkins APL team, is to demonstrate the potential for basic and clinical neuroscience applications in humans [9] [31]. Key challenges include scaling the technology for human use, improving the penetration depth to access deeper brain structures, and further refining signal processing techniques to isolate neural signals from the complex physiological background in a clinical setting. The serendipitous discovery of its ability to non-invasively measure intracranial pressure suggests a near-term clinical application that could run in parallel to BCI development [31].

Wearable MEG and Digital Holographic Imaging represent two pioneering frontiers in non-invasive BCI. Wearable MEG enhances an established neuroimaging technique with unprecedented flexibility, while DHI introduces a completely new biophysical signal for decoding brain activity. Both modalities offer high spatial and temporal resolution, addressing critical limitations of current non-invasive technologies. For researchers and pharmaceutical developers, these tools promise not only future BCI applications but also new avenues for understanding neural circuitry, evaluating neuro-therapeutics, and monitoring brain health in real-time. The ongoing maturation of these technologies will be critical in shaping a future where high-fidelity, non-invasive brain-computer interfacing is a practical reality.

In non-invasive brain-computer interface (BCI) research, the interplay between spatial and temporal resolution represents a fundamental determinant of system capability and application suitability. Neural signals captured through the skull and scalp present researchers with an inherent technological trade-off: no single non-invasive modality currently provides both high spatial fidelity and high temporal precision. This whitepaper provides a technical analysis of this resolution trade-off across major non-invasive BCI technologies, examining how these characteristics influence experimental design, data interpretation, and practical application in clinical and research settings. The convergence of improved sensor hardware with advanced machine learning algorithms is gradually mitigating these limitations, yet the underlying physical and physiological constraints continue to define the boundaries of what is achievable in non-invasive neural interfacing [32] [2].

Fundamental Concepts in BCI Signal Acquisition

Defining Resolution Metrics

In BCI research, temporal resolution refers to the precision with which a system can measure changes in neural activity over time, typically quantified in milliseconds. This metric determines a system's ability to track rapid neural dynamics such as action potentials and oscillatory activity. Spatial resolution, conversely, describes the smallest distinguishable spatial detail in neural activation patterns, typically measured in millimeters, determining how precisely a system can localize brain activity to specific cortical regions [2].

The inverse problem in neuroimaging stems from the mathematical challenge of inferring precise locations of neural activity within the brain from measurements taken at the scalp surface. This problem is inherently ill-posed, as infinite configurations of neural sources can produce identical surface potential patterns, creating fundamental limitations for spatial localization in non-invasive systems [32].

Physiological Basis of Neural Signals

Non-invasive BCIs primarily measure two types of neural correlates: electromagnetic fields generated by postsynaptic potentials and hemodynamic responses related to metabolic demands. Electromagnetic fields propagate nearly instantaneously but diffuse through resistive tissues, while hemodynamic responses reflect metabolic changes with inherent latency of 1-5 seconds, creating the fundamental dichotomy between fast but blurry signals and slow but localized measurements [2] [33].

Comparative Analysis of Non-Invasive BCI Modalities

Quantitative Resolution Characteristics

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Major Non-Invasive BCI Modalities

| Modality | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Penetration Depth | Primary Signal Origin | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEG | ~1-3 cm (Low) | <1 ms (Very High) | Superficial cortical layers | Post-synaptic potentials | Skull blurring, poor deep source localization, low signal-to-noise ratio [32] [2] |

| fNIRS | ~1-2 cm (Medium) | 1-5 seconds (Low) | Superficial cortical layers | Hemodynamic response (blood oxygenation) | Slow hemodynamic response, sensitivity to scalp blood flow [32] [34] |

| MEG | ~3-5 mm (High) | <1 ms (Very High) | Entire cortex | Magnetic fields from postsynaptic currents | Bulky equipment, magnetic shielding requirements, high cost [32] [8] |

| fMRI | 1-3 mm (Very High) | 1-5 seconds (Low) | Whole brain | Hemodynamic response (BOLD effect) | Poor temporal resolution, expensive, immobile [33] |

| fUS | ~0.3-0.5 mm (Ultra-High) | ~1-2 seconds (Medium) | Several centimeters | Cerebral blood volume | Requires acoustic window, emerging technology [32] |

Technical Trade-offs and Performance Envelopes

Table 2: Performance Characteristics and Application Suitability

| Modality | Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Portability | Setup Complexity | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEG | Low to Medium | High | Low | Real-time communication, seizure detection, sleep monitoring, cognitive state assessment [2] [8] |

| fNIRS | Medium | Medium | Medium | Neurofeedback, clinical monitoring, brain activation mapping [32] [34] |

| MEG | High | Low | Very High | Basic cognitive neuroscience, epilepsy focus localization, network connectivity [32] [8] |

| fMRI | High | Low | Very High | Precise functional localization, surgical planning, connectomics [33] |

| fUS | Very High (preclinical) | Medium (potential) | High | High-resolution functional imaging, small animal research [32] |

The relationship between spatial and temporal resolution across modalities reveals a fundamental technology frontier where improvements in one dimension typically come at the expense of the other. This trade-off landscape creates distinct application niches for each modality and drives research into multimodal approaches that combine complementary strengths [32].

Experimental Methodologies for Resolution Assessment

Standard Protocols for Characterizing BCI Performance

Temporal Resolution Validation employs repetitive sensory stimulation (visual, auditory, or somatosensory) with inter-stimulus intervals progressively decreased until the system can no longer resolve individual responses. For EEG, this involves presenting stimuli at frequencies from 0.5 Hz to 30+ Hz while measuring the accuracy of response detection and latency measurements. The steady-state visual evoked potential (SSVEP) paradigm represents a standardized approach where subjects view stimuli flickering at specific frequencies while researchers quantify the signal-to-noise ratio of the elicited responses at each frequency [35].

Spatial Resolution Assessment utilizes focal activation paradigms with known neuroanatomical correlates. The finger-tapping motor task reliably activates the hand knob region of the contralateral motor cortex, allowing researchers to quantify the spatial spread of detected activation. For high-density EEG systems, this involves measuring the topographic distribution of sensorimotor rhythm desynchronization during motor imagery and comparing it to the expected focal pattern [33].

Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) Quantification follows standardized metrics such as the wide-band SNR for SSVEP-based BCIs, which calculates the ratio of signal power at stimulation frequencies to the average power in adjacent non-stimulation frequency bins. This approach enables objective comparison across systems and subjects, with higher SNR values indicating better signal quality and potentially higher information transfer rates [35].

Multimodal Integration Protocols

Simultaneous EEG-fMRI recording requires careful artifact mitigation, particularly the removal of ballistocardiographic artifacts in EEG data caused by cardiac-induced head movement in the magnetic field. This approach leverages fMRI's high spatial resolution to constrain the source localization of EEG signals, effectively creating a hybrid modality with both high temporal and spatial resolution [33].

EEG-fNIRS co-registration provides complementary measures of electrical and hemodynamic activity with relatively straightforward technical implementation. Experimental protocols typically synchronize data acquisition systems and use common triggers, with fNIRS optodes placed within the EEG electrode array based on the international 10-20 system. The combined system can track both immediate neural responses (via EEG) and subsequent metabolic changes (via fNIRS) to the same stimuli [32] [2].

Advanced Technical Approaches

Resolution Enhancement Strategies