Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation for Cognitive Enhancement: Mechanisms, Applications, and Future Directions in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) as a tool for cognitive enhancement, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation for Cognitive Enhancement: Mechanisms, Applications, and Future Directions in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) as a tool for cognitive enhancement, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational neuroplasticity mechanisms of techniques like tDCS and rTMS and their application in enhancing working memory, attention, and learning in both healthy and clinical populations. The scope extends to methodological considerations for optimizing stimulation parameters, troubleshooting efficacy and safety concerns, including individual variability and placebo effects, and a critical validation of outcomes through meta-analyses and comparisons with pharmacological enhancers. The article synthesizes current evidence, identifies research gaps, and discusses the implications for developing targeted, effective neuromodulation-based cognitive interventions.

The Neuroscience of Cognitive Enhancement: Unlocking Neuroplasticity with Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation

In the evolving landscape of cognitive neuroscience and therapeutic development, non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) techniques, particularly transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), have emerged as powerful tools for modulating cortical activity and promoting neuroplasticity. These techniques enable researchers and clinicians to directly influence brain function without surgical intervention, opening new avenues for cognitive enhancement and neurological rehabilitation. The core therapeutic potential of these interventions lies in their ability to induce lasting neuroplastic changes that persist beyond the stimulation period itself, essentially recalibrating neural circuits through mechanisms similar to those underlying learning and memory [1] [2]. For drug development professionals and researchers, understanding the precise physiological mechanisms of tDCS and rTMS is crucial for designing targeted interventions, predicting treatment outcomes, and developing complementary pharmacological approaches.

This technical guide examines the fundamental principles through which tDCS and rTMS modulate cortical excitability and induce neuroplasticity, with particular relevance to cognitive enhancement research. We will explore the distinct yet complementary mechanisms of action, summarize key experimental findings in a structured format, detail essential research methodologies, and visualize the core signaling pathways involved in these processes.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Action

tDCS and rTMS employ fundamentally different physical principles to achieve neural modulation, yet both ultimately converge on mechanisms of neuroplasticity. Their distinct approaches offer complementary advantages for research and therapeutic applications.

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS)

tDCS applies a weak, constant electrical current (typically 1-2 mA) to the scalp via surface electrodes, creating an electric field that modulates the resting membrane potential of neurons in targeted cortical regions [3]. This polarization effect is * polarity-dependent: anodal stimulation increases neuronal excitability by depolarizing membrane potentials, while cathodal stimulation decreases excitability through hyperpolarization [1]. The primary mechanism during stimulation is *subthreshold modulation, meaning tDCS does not directly trigger action potentials but rather alters the likelihood of spontaneous neuronal firing [2].

The lasting effects of tDCS emerge when stimulation is maintained for sufficient duration (typically several minutes), inducing neuroplastic changes that persist after stimulation ceases. These after-effects are mediated by N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity, similar to long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) mechanisms [4]. Research indicates that anodal tDCS particularly enhances cortical excitability in a manner dependent on NMDA receptor activation, while NMDA receptor blockade abolishes these after-effects [2].

Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS)

rTMS utilizes a rapidly changing magnetic field to induce focused electrical currents in cortical tissue, capable of directly triggering action potentials in targeted neurons [3]. Unlike the subthreshold modulation of tDCS, rTMS can produce immediate and powerful neural activation. The effects of rTMS are strongly frequency-dependent: higher frequencies (≥5 Hz) generally increase cortical excitability, while lower frequencies (≤1 Hz) typically suppress it [3].

The neuroplastic effects of rTMS emerge from its ability to induce rhythmic, synchronized neural firing that modifies synaptic strength according to spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) principles [2]. Repeated sessions can lead to long-term reorganization of cortical networks, making it particularly valuable for therapeutic applications. The mechanisms involve complex interactions between glutamatergic transmission, GABAergic inhibition, and potentially other neurotransmitter systems [5].

Table 1: Comparative Mechanisms of tDCS and rTMS

| Parameter | tDCS | rTMS |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Principle | Constant electrical current | Pulsed magnetic field |

| Neural Effect (During Stimulation) | Subthreshold polarization | Suprathreshold activation |

| Primary Immediate Effect | Modulates neuronal excitability | Elicits action potentials |

| Polarity/Frequency Dependence | Anodal (excitatory) vs. Cathodal (inhibitory) | High-frequency (excitatory) vs. Low-frequency (inhibitory) |

| Plasticity Mechanisms | NMDA receptor-dependent LTP/LTD | Spike-timing-dependent plasticity |

| Spatial Resolution | Moderate (diffuse) | High (focal) |

| Depth of Penetration | Superficial cortical layers | Several centimeters into cortex |

Neurophysiological Biomarkers and Experimental Outcomes

Quantifiable neurophysiological biomarkers provide critical insights into the mechanisms and efficacy of tDCS and rTMS interventions. These measures allow researchers to objectively assess cortical excitability and neuroplasticity in both basic research and clinical applications.

Key Neurophysiological Indicators

Motor Evoked Potentials (MEPs) represent a primary outcome measure in NIBS research, particularly for assessing motor cortex excitability. MEPs are recorded from target muscles following stimulation of the corresponding motor cortex and provide a quantitative measure of corticospinal tract integrity and excitability. Research has consistently demonstrated that anodal tDCS and high-frequency rTMS increase MEP amplitudes, reflecting enhanced cortical excitability [4]. For example, a recent study on fibromyalgia patients demonstrated that a single session of anodal tDCS significantly increased MEP amplitude compared to sham stimulation (Wald χ² = 8.37, df = 1, p < 0.01; effect size d = 0.48) [4].

Intracortical Inhibition and Facilitation mechanisms can be assessed through paired-pulse TMS paradigms. Short-interval intracortical inhibition (SICI) measures GABAergic inhibition, while intracortical facilitation (ICF) reflects glutamatergic excitatory processes. Studies indicate that effective NIBS interventions often reduce SICI, suggesting disinhibition as a mechanism for enhancing plasticity [5]. For instance, in hemiparetic children undergoing intensive therapy combined with rTMS, decreased SICI from the contralesional motor cortex correlated with improved hand function [5].

Cortical Silent Period (CSP) represents another GABAergic biomarker, reflecting inhibitory neurotransmission within the motor cortex. Research has shown that tDCS can modulate CSP in a brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)-dependent manner, linking neurotrophic signaling with cortical inhibition mechanisms [4].

Quantitative Outcomes in Clinical Populations

Table 2: Experimentally Measured Effects of tDCS and rTMS on Cognitive and Motor Functions

| Condition | Stimulation Technique | Key Outcome Measures | Reported Effect Sizes | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease Memory Deficits | tDCS (temporal regions) | Standardized mean difference (SMD) in memory performance | SMD=0.32, p=0.04 [3] | Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials |

| Alzheimer's Disease Memory Deficits | rTMS (frontal regions) | Standardized mean difference (SMD) in memory performance | SMD=0.61, p<0.001 [3] | Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials |

| Fibromyalgia Pain | tDCS (M1 stimulation) | Numerical Pain Scale (0-10) reduction | d=0.55, 95% CI 0.08-0.92 [4] | Double-blind, sham-controlled RCT |

| Fibromyalgia Pain | tDCS (M1 stimulation) | Motor Evoked Potential amplitude increase | d=0.48, 95% CI 0.07-0.89 [4] | Double-blind, sham-controlled RCT |

| Post-Stroke Aphasia | cTBS (theta burst stimulation) | Language recovery correlated with BDNF genotype | Significant interaction effects (p<0.05) [6] | Genetic and neurophysiological biomarker study |

Molecular Pathways of Neuroplasticity

The neuroplastic effects of tDCS and rTMS engage sophisticated molecular signaling pathways that translate external stimulation into lasting neural changes. Understanding these pathways is essential for optimizing interventions and identifying potential pharmacological adjuvants.

Glutamatergic Signaling and NMDA Receptor Activation

Both tDCS and rTMS primarily influence glutamatergic neurotransmission, particularly through NMDA receptor activation. During tDCS, the sustained membrane depolarization relieves the magnesium block of NMDA receptors, permitting calcium influx that triggers downstream signaling cascades leading to LTP [2]. Similarly, rTMS-induced synchronized firing activates NMDA receptors through precise pre- and postsynaptic timing, engaging STDP mechanisms [2]. These processes initiate intracellular signaling cascades involving calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), protein kinase A (PKA), and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) that ultimately lead to gene expression changes and structural modifications at synapses.

BDNF and Neurotrophic Signaling

The brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) plays a crucial role in mediating the neuroplastic effects of both tDCS and rTMS. BDNF promotes synaptic strengthening, neuronal growth, and survival through its tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB) receptor. Research has identified a common BDNF polymorphism (Val66Met) that influences responses to NIBS, with Val66Val carriers typically showing better outcomes than Met carriers [6]. For example, in post-stroke aphasia recovery, Val66Val carriers showed expected effects of age on aphasia severity and positive associations between severity and both cortical excitability and stimulation-induced neuroplasticity, whereas Val66Met carriers showed opposite patterns [6].

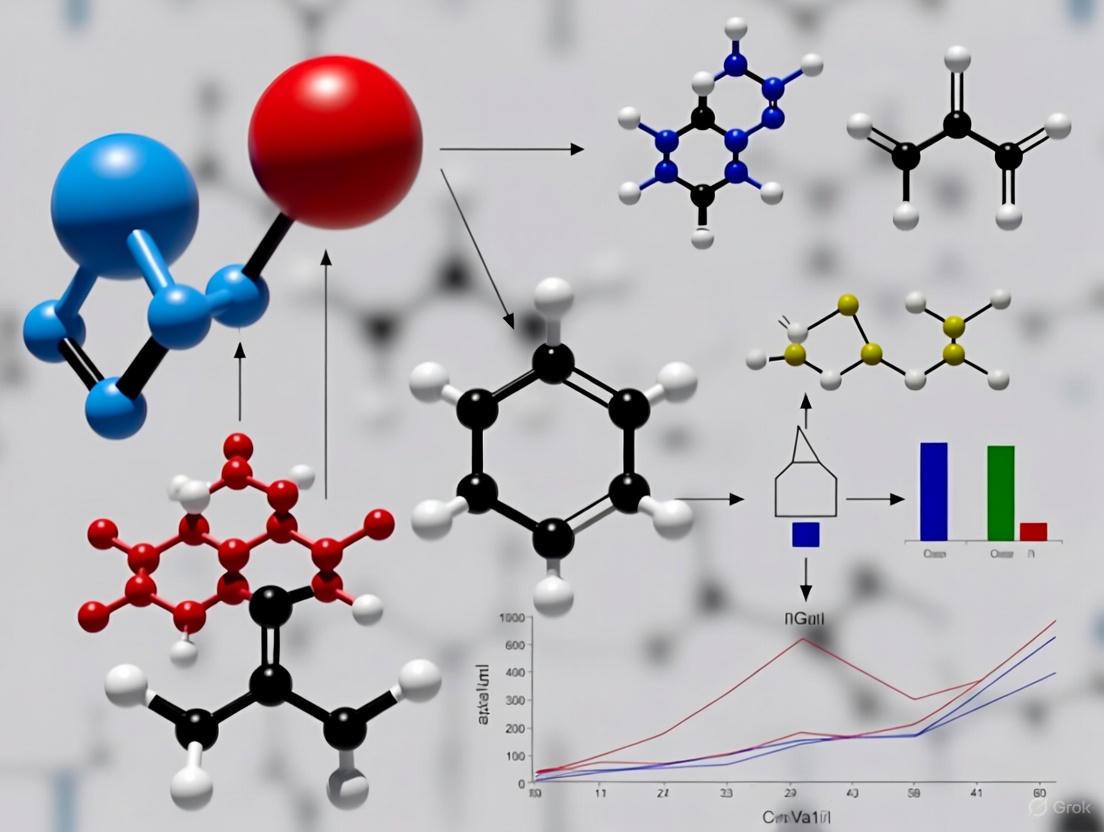

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular pathways through which tDCS and rTMS induce neuroplasticity:

Diagram 1: Molecular Pathways of tDCS and rTMS-Induced Neuroplasticity. Both techniques converge on NMDA receptor activation and calcium-dependent signaling pathways that ultimately drive gene expression changes and structural plasticity. BDNF signaling serves as a critical amplifier and modulator of these effects.

Research Methods and Experimental Protocols

Robust experimental design is essential for investigating the effects of tDCS and rTMS on cortical excitability and neuroplasticity. Below we detail key methodological considerations and provide a specific protocol exemplifying high-quality research in this field.

Standard Experimental Workflow

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive research workflow for studying tDCS and rTMS effects:

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for tDCS/rTMS Research. A typical study involves comprehensive baseline assessment, randomized assignment to active or control conditions, potentially combined with behavioral training, and multiple post-intervention assessment timepoints to capture immediate and lasting effects.

Example Research Protocol: Motor Cortex Stimulation

A rigorously controlled tDCS study investigating fibromyalgia pain mechanisms provides an exemplary protocol [4]:

Study Design: Double-blind, sham-controlled, randomized clinical trial with parallel groups.

Participants: 92 female fibromyalgia patients randomized to one of four conditions: (1) anodal tDCS over primary motor cortex (M1), (2) anodal tDCS over cerebellum (CB), (3) combined M1+CB stimulation, or (4) sham stimulation.

Stimulation Parameters:

- Device: Conventional tDCS stimulator

- Current Intensity: 2 mA

- Electrode Size: 35 cm²

- Stimulation Duration: 20 minutes

- Electrode Placement: According to international 10-20 EEG system for M1 (C3/C4) and cerebellar positioning

- Sham Protocol: Ramped up/down with no sustained stimulation

Primary Outcomes:

- Pain Intensity: Numerical Pain Scale (0-10) scores

- Corticospinal Excitability: Motor Evoked Potential (MEP) amplitude measured via TMS

Secondary Outcomes:

- Multidimensional Pain Interference: Brief Pain Inventory (BPI)

- Intracortical Inhibition: Cortical Silent Period (CSP) and Short-Interval Intracortical Inhibition (SICI)

- Neuroplasticity Biomarker: Serum BDNF levels

Assessment Timeline: Baseline, immediately post-stimulation, and at 2-week follow-up.

This protocol exemplifies key methodological rigor through its double-blind design, appropriate sham control, multiple assessment timepoints, and integration of neurophysiological with clinical measures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for tDCS and rTMS Studies

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulation Devices | tDCS stimulator, TMS/rTMS machine with figure-8 or H-coil | Delivery of controlled stimulation | Output accuracy, safety features, programmability |

| Electrodes/Coils | Conductive rubber electrodes (tDCS), Cooled coils (rTMS) | Interface between device and subject | Size, shape, positioning, cooling capacity |

| Electrode Preparation | Electrode gels, saline solutions, conductive pastes | Maintain conductivity and reduce impedance | pH buffering, skin compatibility |

| Neurophysiology Recording | EMG system, EEG equipment, TMS-compatible amplifiers | Measure neurophysiological outcomes | Signal-to-noise ratio, TMS artifact rejection |

| Neuronavigation | MRI-based frameless stereotaxy, Polaris tracking systems | Precise coil/electrode positioning | Individualized targeting, reproducibility |

| Biomarker Assays | ELISA kits for BDNF, Genetic testing for BDNF Val66Met | Assess molecular mechanisms | Sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility |

| Computational Modeling | SIMNIBS, ROAST, BrainStorm | Electric field estimation and dose planning | Individualized head models, accuracy of predictions |

| N4-Cyclopentylpyridine-3,4-diamine | N4-Cyclopentylpyridine-3,4-diamine | High-purity N4-Cyclopentylpyridine-3,4-diamine for pharmaceutical and organic synthesis research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 3-chloro-2-phenylprop-2-enamide | 3-Chloro-2-phenylprop-2-enamide|Research Chemical | High-quality 3-chloro-2-phenylprop-2-enamide for research applications. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and is not intended for diagnostic or personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

tDCS and rTMS represent distinct yet complementary approaches to modulating cortical excitability and inducing neuroplasticity through well-defined physiological mechanisms. While tDCS operates through subthreshold polarization of neuronal membranes in a polarity-dependent manner, rTMS employs electromagnetic induction to directly trigger action potentials in a frequency-dependent fashion. Both techniques ultimately engage activity-dependent synaptic plasticity mechanisms, primarily through glutamatergic signaling and NMDA receptor activation, leading to lasting functional and structural changes in neural circuits.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these techniques offer powerful tools for both basic neuroscience investigation and therapeutic development. The ability to non-invasively target specific cortical regions and modulate their excitability creates opportunities to explore brain-function relationships, enhance cognitive processes, and develop novel treatment approaches for neurological and psychiatric conditions. Future research directions should focus on optimizing stimulation parameters through computational modeling, identifying biomarkers that predict individual response variability, and developing protocols that selectively target specific neural populations and plasticity mechanisms.

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) stands as a critical hub within the brain's cognitive control network, orchestrating higher-order executive functions essential for goal-directed behavior. This region is fundamentally involved in processes such as working memory, cognitive flexibility, and the complex task of emotion regulation [7]. Within the framework of non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) research, the DLPFC has emerged as a primary target for interventions aimed at cognitive enhancement. The overarching goal of this research is to precisely modulate neural activity to improve cognitive outcomes and treat neuropsychiatric conditions. This whitepaper provides an in-depth examination of the DLPFC's role, its functional interactions with other key brain regions, and the experimental evidence from cutting-edge NIBS studies that solidify its status as a premier target for cognitive enhancement. It further details specific stimulation protocols and provides a toolkit for researchers working at the intersection of cognitive neuroscience and neuromodulation.

Anatomical and Functional Profile of the DLPFC

The DLPFC is not a monolithic structure; it is a key node within a broader prefrontal network. Its primary function is the implementation of cognitive control—a set of processes that allows for the resolution of conflict between task-relevant and task-irrelevant information to enable purposeful behavior [8]. Recent theoretical frameworks, such as the cognitive space theory, posit that the DLPFC organizes diverse types of cognitive conflicts along a continuous, low-dimensional representational space [8]. This organization allows a limited set of cognitive control processes to efficiently handle a wide array of challenges by representing conflicts based on their similarity.

Furthermore, the DLPFC employs sophisticated temporal coding strategies. Research involving intracranial recordings in neurosurgical patients has revealed that, beyond simple firing rate changes, the DLPFC utilizes oscillatory activity and spike-field coherence (SFC), particularly in the theta (~4-8 Hz) and beta (~16-24 Hz) frequency ranges, to coordinate neural populations during conflict processing [9]. This temporal coding is crucial for the cross-areal coordination necessary for complex cognitive control.

Table 1: Key Functional Roles of the DLPFC

| Function | Description | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Conflict Resolution | Resolves competition between sensory, internal, and motor information to guide goal-directed actions. | Represents different conflicts in a cognitive space based on similarity [8]. |

| Cognitive Control | Monitors ongoing tasks, maintains goals in working memory, and implements top-down biases. | Critical for tasks requiring adjustment of behavior after conflict, like the Stroop-Simon task [8]. |

| Emotion Regulation | Supports cognitive reappraisal by maintaining regulatory goals and manipulating emotional content in working memory. | Inhibition via TMS impairs reappraisal efficacy, reducing modulation of neural markers like the LPP [7]. |

| Temporal Coordination | Coordinates neural computation through oscillatory activity and spike-phase coupling. | Conflict modulates spike-field coherence in theta and beta frequencies [9]. |

The DLPFC in Network Interactions

The DLPFC does not operate in isolation. Its efficacy as a cognitive hub is derived from its dynamic interactions with other prefrontal and subcortical regions. Two of the most critical network interactions for cognitive and emotional function are with the Ventrolateral Prefrontal Cortex (VLPFC) and the Dorsal Anterior Cingulate Cortex (dACC).

DLPFC and VLPFC Collaboration in Emotion Regulation

The DLPFC and VLPFC work in concert to enable cognitive reappraisal. The DLPFC is thought to handle the maintenance and manipulation of reappraisal goals in working memory, while the VLPFC may be more involved in the selection and application of specific semantic reinterpretations [10]. A seminal 2025 study provided causal evidence for this collaboration by using theta-band transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) to modulate the synchrony between these two regions [10]. The findings demonstrated that in-phase tACS, which enhances synchrony, significantly improved reappraisal performance, reduced subjective regulation difficulty, and decreased the amplitude of the late positive potential (LPP)—a neural marker of emotional arousal. In contrast, anti-phase stimulation disrupted this process. This study underscores that the functional integration between DLPFC and VLPFC, facilitated by neural synchrony, is a key mechanism for effective emotion regulation.

DLPFC and dACC Dynamics in Cognitive Control

The dACC is frequently cast as a conflict monitor that signals the need for increased cognitive control, which is then implemented by the DLPFC [9]. Intracranial recordings reveal that while the dACC shows a robust phase code for decision conflict (i.e., the timing of spikes relative to the local field potential oscillation changes with conflict), the DLPFC exhibits stronger conflict-related changes in spike-field coherence [9]. This suggests a mechanism where the dACC monitors for conflict and influences the DLPFC, which in turn enhances the coordination of its local neural populations to implement top-down control.

The following diagram illustrates this coordinated network:

Diagram 1: DLPFC Cognitive Control Network

Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation Techniques and Targets

Non-invasive brain stimulation techniques offer powerful tools for causally investigating and modulating these cognitive hubs. The following table summarizes the primary NIBS modalities and their application to the DLPFC and related networks.

Table 2: Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation Modalities for Cognitive Hubs

| Technique | Mechanism | Key Target(s) | Research & Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMS/TBS | Uses magnetic fields to induce electrical currents in cortical neurons. Can be excitatory or inhibitory. | DLPFC, VLPFC | Inhibitory cTBS of right DLPFC impairs reappraisal [7]. Excitatory rTMS improves reappraisal [7]. FDA-approved for depression [11]. |

| tDCS | Applies a weak constant current to modulate neuronal membrane excitability. | DLPFC, Orbitofrontal Cortex (OFC) | Anodal (excitatory) tDCS of right DLPFC can decrease emotional arousal [7]. Bilateral tDCS of OFC curbs impulsivity [12]. |

| tACS | Applies a sinusoidal current to entrain or synchronize neural oscillations at a specific frequency. | DLPFC-VLPFC network | In-phase theta tACS enhances synchrony and improves reappraisal performance [10]. |

| tSMS | Applies static magnetic fields to suppress cortical excitability. | Right Frontopolar Cortex | Reduces self-focused attention in social anxiety [12]. |

| Focused Ultrasound | Uses focused sound waves to modulate deep brain structures with high precision. | Subcortical circuits | Potential for treating epilepsy and Parkinson's; can be combined with nanocarriers for targeted drug delivery [11]. |

Experimental Protocols and Quantitative Outcomes

This section details the methodologies and results from key experiments that establish the causal role of the DLPFC and its networks.

Protocol 1: Theta tACS for Enhancing DLPFC-VLPFC Synchrony

- Objective: To causally test the role of DLPFC-VLPFC theta-band synchrony in cognitive reappraisal [10].

- Subjects: 43 healthy participants in Experiment 1; 43 in Experiment 2.

- Stimulation Protocol: Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS) at theta frequency (e.g., 6 Hz). Three conditions were compared: in-phase (synchronizing), anti-phase (desynchronizing), and sham (placebo) stimulation applied over the DLPFC and VLPFC.

- Task: Participants performed a cognitive reappraisal task, viewing negative images and either passively watching them or reinterpreting them to reduce negative emotion.

- Outcome Measures: Self-reported negative emotion, regulation difficulty, and electroencephalography (EEG) measurement of the Late Positive Potential (LPP).

- Results: In-phase tACS specifically enhanced reappraisal success, as shown by reduced negative emotion, lower difficulty ratings, and a smaller LPP amplitude. Experiment 2 confirmed that in-phase tACS selectively enhanced theta-band phase-locking values between the two regions and had no effect on a different regulation strategy (distraction), demonstrating specificity.

Protocol 2: cTBS for Inhibiting the DLPFC

- Objective: To verify the causal role of the bilateral DLPFC in emotion regulation using an inhibitory stimulation protocol [7].

- Subjects: 26 healthy participants.

- Stimulation Protocol: Continuous Theta Burst Stimulation (cTBS), an inhibitory form of repetitive TMS, was applied on separate days over the left DLPFC, right DLPFC, and an active control site (the vertex).

- Task: After stimulation, participants completed a reappraisal task with neutral, negative-watch, and negative-reappraise conditions.

- Outcome Measures: The Late Positive Potential (LPP) was measured via EEG in early (350-750 ms) and late (750-1500 ms) time windows. Subjective emotional ratings were also collected.

- Results: Inhibitory stimulation of the right DLPFC significantly impaired reappraisal efficacy compared to the vertex control, reflected in a reduced LPP modulation effect in both early and late time windows. Inhibition of the left DLPFC showed no significant effect, highlighting the lateralized role of the right DLPFC in this specific regulatory process.

Table 3: Summary of Key Experimental Outcomes from DLPFC-Targeted NIBS Studies

| Study Protocol | Target Region | Stimulation Parameters | Key Behavioral/Subjective Outcome | Key Neural Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tACS (In-phase) [10] | DLPFC-VLPFC Network | Theta-band (e.g., 6 Hz), In-phase | Enhanced reappraisal success; Reduced regulation difficulty. | Increased theta phase-locking; Reduced LPP amplitude. |

| cTBS (Inhibitory) [7] | Right DLPFC | cTBS (inhibitory TMS) | No significant change in self-report. | Impaired LPP modulation during reappraisal. |

| rTMS (Excitatory) [7] | Right DLPFC / VLPFC | 10 Hz rTMS (excitatory TMS) | Improved reappraisal efficacy. | Increased LPP modulation (inferred). |

| tDCS (Anodal) [7] | Right DLPFC | 2 mA anodal tDCS (excitatory) | Decreased emotional arousal ratings. | Decreased skin-conductance response. |

The following diagram outlines a generalized workflow for designing a NIBS experiment targeting the DLPFC:

Diagram 2: NIBS Experiment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers aiming to replicate or build upon the studies cited, the following table catalogues essential "research reagents"—the key materials, tools, and methods required for this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for DLPFC-Targeted NIBS Studies

| Tool / Material | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Neuromodulation Device | TMS (e.g., Magstim), tDCS/tACS (e.g., Neuroelectrics) | The primary instrument for non-invasively delivering controlled stimulation to target brain regions. |

| Neuronavigation System | MRI-guided system (e.g., Brainsight) | Precisely localizes the DLPFC or other targets on an individual's scalp using their structural MRI, ensuring targeting accuracy. |

| Electroencephalography (EEG) | High-density EEG system (e.g., 64+ channels) | Measures millisecond-level neural activity in response to stimulation; critical for assessing LPP and oscillatory dynamics. |

| Cognitive Task Paradigm | Cognitive Reappraisal Task; Multi-Source Interference Task (MSIT) [9]; Stroop-Simon Task [8] | Provides a behavioral framework to elicit and measure the cognitive functions (e.g., control, emotion regulation) under investigation. |

| Computational Modeling Software | Electric field modeling (e.g., SIMNIBS) | Models the electric field distribution in the brain for a given tES montage, helping to optimize and interpret stimulation protocols. |

| Physiological Measure | Skin Conductance Response (SCR) | Provides an objective, peripheral measure of emotional arousal that can complement neural and self-report data. |

| Bis(2,4-dinitrophenyl)-L-histidine | Bis(2,4-dinitrophenyl)-L-histidine, MF:C18H13N7O10, MW:487.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Methoxymethanesulfonyl chloride | Methoxymethanesulfonyl Chloride|Research Chemical | Methoxymethanesulfonyl chloride is a sulfonyl chloride research intermediate. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. |

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is unequivocally established as a central cognitive hub, whose function is critically dependent on its dynamic interactions with a network of regions including the VLPFC and dACC. Research utilizing non-invasive brain stimulation techniques has moved beyond correlation to provide compelling causal evidence for the DLPFC's role in cognitive control and emotion regulation. The emergence of specific protocols, such as theta-band tACS to modulate inter-regional synchrony and inhibitory TMS to disrupt function, provides a powerful toolkit for both basic research and therapeutic development. Future research directions will likely focus on personalizing stimulation targets and parameters using individual neural and behavioral markers [12] [11], combining NIBS with other modalities like neurofeedback or pharmacology, and leveraging advanced techniques like focused ultrasound to target deeper nodes within the cognitive control network. As these technologies and our understanding of brain networks continue to evolve, the precise enhancement of cognitive function through non-invasive means becomes an increasingly tangible goal.

Non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) represents a transformative approach in cognitive neuroscience, offering the potential to modulate neural circuitry underlying core cognitive domains such as memory, attention, and executive function. These techniques, primarily transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), leverage our growing understanding of neurophysiological processes to induce targeted neuroplastic changes. As research advances, the transition from fundamental mechanistic studies to clinically applicable protocols has accelerated, providing new avenues for therapeutic intervention in various neurological and psychiatric conditions characterized by cognitive deficits. This technical guide synthesizes current evidence and methodologies, framing them within the broader context of NIBS-based cognitive enhancement research, to provide researchers and clinicians with a comprehensive resource for understanding and applying these innovative approaches.

Neurophysiological Foundations of Cognitive Domains

Memory Systems and Their Substrates

Memory function relies on a distributed network centered on the medial temporal lobe system, particularly the hippocampus and surrounding entorhinal cortex, which coordinate with prefrontal regions for memory encoding, consolidation, and retrieval. The neurophysiological basis of memory involves long-term potentiation (LTP), a persistent strengthening of synapses based on recent patterns of activity, and theta-gamma cross-frequency coupling, which facilitates communication between brain regions during memory processes [13]. Research indicates that memory consolidation occurs preferentially during slow-wave sleep, characterized by synchronized neural oscillations and sleep spindles that facilitate the transfer of information from hippocampal to neocortical storage sites [13].

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) plays a crucial role in working memory maintenance and manipulation, with persistent neural activity in the gamma frequency band (30-100 Hz) supporting the active retention of information [14]. Different NIBS approaches target specific aspects of this complex memory network: high-frequency repetitive TMS (HF-rTMS) can enhance cortical excitability in targeted regions, while transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) applied during sleep can modulate oscillatory activity to improve memory consolidation [13].

Attentional Networks and Mechanisms

Attention involves multiple distinct networks, including the dorsal attention network for top-down orienting and the ventral attention network for bottom-up stimulus detection. Key nodes include the frontal eye fields, intraparietal sulcus, and temporoparietal junction, with the right hemisphere playing a dominant role, particularly in sustained attention tasks. Neurophysiologically, attention modulates neural activity in the alpha (8-12 Hz) and gamma bands, with increased gamma synchronization in task-relevant regions and alpha suppression in distracting regions.

The cingulo-fronto-parietal (CFP) network serves as the central executive system for attention, with the anterior cingulate cortex monitoring conflict and the DLPFC implementing control [15]. Studies applying 10 Hz rTMS to frontal and parietal targets within this network have demonstrated activation in brain regions related to cognition, highlighting the potential for targeted stimulation to enhance attentional function [15].

Executive Function and Prefrontal Control

Executive function encompasses higher-order cognitive processes including planning, cognitive flexibility, inhibition, and problem-solving, primarily mediated by the prefrontal cortex and its connections with subcortical structures. The DLPFC is particularly crucial for working memory and complex reasoning, while the ventromedial PFC contributes to decision-making and emotional regulation. From a neurophysiological perspective, executive functions rely on precisely coordinated neural activity across multiple frequency bands, with theta oscillations (4-8 Hz) in the anterior cingulate cortex signaling the need for cognitive control and gamma oscillations facilitating information transfer between regions.

The left DLPFC has been identified as a promising stimulation target for enhancing global cognitive performance, with a surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) value of 89.1% for improving global cognitive function after stroke [14]. Network meta-analyses indicate that HF-rTMS over the left DLPFC appears to be the most promising NIBS therapeutic option for improving global cognitive performance [14].

NIBS Modalities and Their Mechanisms of Action

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS)

TMS operates on the principle of electromagnetic induction, where a time-varying magnetic field generated by a coil placed on the scalp induces electrical currents in the underlying cortical tissue, depolarizing neurons and modulating cortical excitability [14]. The effects of TMS depend on stimulation parameters, particularly frequency:

- High-frequency rTMS (>1 Hz): Promotes increased cortical excitability through mechanisms resembling long-term potentiation (LTP) [14]

- Low-frequency rTMS (≤1 Hz): Decreases cortical excitability through mechanisms similar to long-term depression (LTD) [14]

- Theta-burst stimulation (TBS): A patterned form of rTMS consisting of triplets of 50 Hz pulses delivered at 5 Hz [14]

- Intermittent TBS (iTBS): Increases cortical excitability

- Continuous TBS (cTBS): Decreases cortical excitability

Table 1: TMS Protocols for Cognitive Enhancement

| Protocol | Frequency Pattern | Primary Effect | Key Cognitive Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| HF-rTMS | >1 Hz, regular intervals | ↑ Cortical excitability | Global cognition, attention [14] |

| LF-rTMS | ≤1 Hz, regular intervals | ↓ Cortical excitability | - |

| iTBS | 50 Hz triplets at 5 Hz, intermittent | ↑ Cortical excitability | Working memory, cognitive control [14] |

| cTBS | 50 Hz triplets at 5 Hz, continuous | ↓ Cortical excitability | - |

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS)

tDCS applies a weak, constant direct current (typically 1-2 mA) through scalp electrodes to modulate neuronal membrane potentials [14]. Unlike TMS, tDCS does not induce neuronal firing but rather alters the likelihood of spontaneous neuronal discharge:

- Anodal tDCS: Increases cortical excitability by depolarizing neuronal membranes [15]

- Cathodal tDCS: Decreases cortical excitability by hyperpolarizing neuronal membranes [15]

- Dual-tDCS: Simultaneous application of anodal and cathodal stimulation to differentially modulate two brain regions [14]

tDCS effects are believed to involve changes in NMDA receptor efficacy and alterations in synaptic plasticity, with aftereffects persisting beyond the stimulation period due to these neuroplastic mechanisms [15]. Research has demonstrated that dual-tDCS over bilateral DLPFC may be particularly advantageous for patients with post-stroke memory impairment [14].

Emerging NIBS Approaches

Recent technological advances have led to the development of more sophisticated stimulation paradigms:

- High-definition tDCS (HD-tDCS): Uses multiple smaller electrodes to provide more focal stimulation than conventional tDCS [13]

- Transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS): Applies oscillatory currents to entrain endogenous brain rhythms and modulate inter-regional communication [13]

- Multi-site NIBS (MS-NIBS): Simultaneously or sequentially targets multiple brain regions to modulate network dynamics rather than isolated areas [15]

Table 2: Comparative Mechanisms of NIBS Techniques

| Technique | Primary Mechanism | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMS/rTMS | Electromagnetic induction | Moderate (focal to 1-2 cm) | Excellent (milliseconds) | Strong evidence base; clear frequency-dependent effects [14] |

| tDCS | Modulation of membrane potentials | Low (diffuse) | Limited (minutes to hours) | Portable; low-cost; suitable for combined use during tasks [14] [15] |

| tACS | Entrainment of neural oscillations | Low (diffuse) | Good (cycle-specific) | Ability to target specific oscillatory frequencies [13] |

| MS-NIBS | Network modulation | High (multiple targeted regions) | Variable | Addresses distributed nature of cognitive networks [15] |

Quantitative Evidence for Cognitive Enhancement

Effects on Global Cognitive Function

Network meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrate that specific NIBS protocols significantly enhance global cognitive performance, particularly in neurological populations. HF-rTMS has shown substantial benefits for global cognitive function compared to sham stimulation (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 1.95; 95% CI: 0.47-3.43) [14]. Multi-site NIBS approaches appear superior to single-site stimulation, with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) scores significantly higher in the MS-NIBS group compared to SS-NIBS (mean difference [MD] = 1.84, 95% CI = 1.21-2.48, p < 0.00001) [15].

Subgroup analyses reveal that multi-site TMS (MS-TMS) (MD = 2.1, 95% CI = 1.38-2.81, p < 0.00001) and combined TMS+tDCS protocols (MD = 1.91, 95% CI = 0.81-3.01, p = 0.0007) exhibit superior efficacy compared to single-site NIBS [15]. The left DLPFC has been identified as the most effective stimulation site for enhancing global cognitive function (SUCRA = 89.1%) [14].

Domain-Specific Cognitive Effects

Table 3: Domain-Specific Effects of NIBS on Cognitive Functions

| Cognitive Domain | Most Effective Protocol | Effect Size (vs. Sham) | Key Brain Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Memory | Dual-tDCS over bilateral DLPFC | SMD = 6.38; 95% CI: 3.51-9.25 [14] | Bilateral DLPFC (SUCRA = 99.9%) [14] |

| Executive Function | rTMS | SMD = 1.64; 95% CI: 0.18-0.83 [16] | Left DLPFC, anterior cingulate |

| Language | rTMS | SMD = 1.64; 95% CI: 1.22-2.06 [16] | Left perisylvian regions |

| Visuospatial Ability | MS-NIBS | CDT: MD = 1.65, 95% CI = 0.77-2.53 [15] | Right parietal cortex |

| Attention/Processing Speed | MS-NIBS (Trail Making) | TMT: MD = 4.2, 95% CI = 2.71-5.69 [15] | Cingulo-fronto-parietal network |

For memory enhancement specifically, dual-tDCS over the bilateral DLPFC demonstrates particularly strong effects (SMD = 6.38; 95% CI: 3.51-9.25), significantly outperforming other protocols [14]. Bilateral DLPFC stimulation has the highest ranking for memory enhancement (SUCRA = 99.9%) [14]. tDCS has also shown significant effects on memory in patients with Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment (SMD = 0.60; 95% CI: 0.32-0.89) [16].

Emerging approaches include closed-loop systems that monitor neural activity and provide precisely timed stimulation, with one study demonstrating a 40% improvement in vocabulary learning compared to sham conditions [13]. Similarly, targeted memory reactivation during sleep, which uses sensory cues to strengthen specific memories during slow-wave sleep, has shown 35% improvement in retention of cued information [13].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized TMS Protocols for Cognitive Enhancement

HF-rTMS Protocol for Global Cognitive Enhancement:

- Target: Left DLPFC (localized using EEG 10-20 system at F3 or neuronavigation)

- Parameters: Frequency 10 Hz, 60 trains of 4.9s duration, 25.2s intertrain interval, 1500 pulses/session [14]

- Intensity: 90-110% of resting motor threshold

- Course: 10-20 sessions over 2-4 weeks

- Cognitive Assessment: MoCA, MMSE pre-, post-, and at follow-up (1-3 months)

iTBS Protocol for Working Memory:

- Target: Bilateral DLPFC (sequential stimulation)

- Parameters: 50 Hz triplets repeated at 5 Hz, 2s stimulation, 8s rest, 600 pulses/session

- Intensity: 80% of active motor threshold

- Course: 15-30 sessions over 3-6 weeks

- Cognitive Assessment: Digit Span, N-back, Working Memory Tasks

tDCS Protocols for Memory Enhancement

Dual-tDCS Protocol for Memory:

- Electrode Placement: Anode over left DLPFC (F3), cathode over right DLPFC (F4)

- Parameters: 1.5-2 mA current intensity, 20-30 minute duration

- Schedule: Daily sessions for 2-4 weeks

- Concurrent Activity: Often paired with cognitive training during stimulation

- Cognitive Assessment: Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test [14]

High-Definition tDCS Protocol:

- Electrode Configuration: 4x1 ring configuration with center electrode at F3

- Parameters: 1.5-2 mA, 20 minutes

- Advantage: Improved focality compared to conventional tDCS [13]

Multi-Site NIBS Approaches

MS-NIBS represents a paradigm shift from single-target to network-based stimulation [15]. Several strategic approaches have been developed:

- Sequential single-modality stimulation: Such as cerebellar-cerebral tDCS where stimulation is applied sequentially to different nodes of a network [15]

- Synchronous single-modality stimulation: Using multiple electrodes in network tDCS electrode combinations to simultaneously target several regions [15]

- Simultaneous dual-modality stimulation: Applying different NIBS techniques concurrently (e.g., 10 Hz rTMS to iM1 and cathodal tDCS to cM1) [15]

- Oscillatory stimulation strategy: Using dual-site tACS to regulate inter-regional phase synchronization [15]

- Cortico-cortical paired associative stimulation (cc-PAS): Paired-pulse approach to modulate cortical excitability and behavior [15]

Closed-Loop and Personalized Approaches

Recent advances in 2025 have focused on personalized, closed-loop systems that adapt stimulation parameters in real-time based on neural activity:

Closed-Loop tACS System:

- Monitoring: Continuous EEG to detect brain states conducive to learning

- Stimulation Trigger: Theta phase or slow oscillation up-states

- Parameters: Individualized frequency based on endogenous rhythms

- Outcome: 40% improvement in vocabulary learning compared to sham [13]

Sleep-Targeted Memory Enhancement:

- Method: Targeted memory reactivation during slow-wave sleep

- Implementation: Consumer-grade EEG headband with smartphone app

- Procedure: Auditory cues associated with learned material during slow-wave sleep

- Outcome: 35% improvement in retention of cued information [13]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for NIBS Cognitive Studies

| Category | Specific Tools/Assessments | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuro-navigation Systems | MRI-guided navigation, Brainsight, Localite | Precise targeting of stimulation sites | Improves reproducibility and targeting accuracy |

| Cognitive Assessment Batteries | MoCA, MMSE, Digit Span, Trail Making Test, N-back | Quantifying cognitive outcomes | Domain-specific tests sensitive to change |

| Neurophysiological Monitoring | EEG, fNIRS-EEG dual-modality systems, EMG | Assessing neural mechanisms and safety | fNIRS-EEG provides complementary hemodynamic and electrophysiological data [17] |

| Safety Monitoring | Seizure questionnaire, adverse event reporting | Ensuring participant safety | Standardized protocols for different risk profiles |

| Sham/Control Conditions | Sham coils, placebo electrodes with brief stimulation | Controlling for non-specific effects | Effective blinding is critical for validity |

| Data Analysis Platforms | MATLAB with EEGLAB, FMRIB Software Library, R | Processing neuroimaging and behavioral data | Standardized pipelines for reproducibility |

| 3,7-Dimethyl-1-octyl propionate | 3,7-Dimethyl-1-octyl propionate, CAS:93804-81-0, MF:C13H26O2, MW:214.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Dimethiodal | Dimethiodal, CAS:76-07-3, MF:CH2I2O3S, MW:347.90 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Integration Systems

The integration of fNIRS and EEG in dual-modality systems represents a significant advancement in monitoring NIBS effects, providing complementary information about electrophysiological activity and hemodynamic responses [17]. These systems typically include:

- EEG electrodes and fNIRS probes integrated into a shared helmet design [17]

- Lower computer microcontroller generating drive signals and amplifying intensity signals [17]

- Upper computer software for preprocessing, fusion analysis, and mathematical modeling [17]

- Customized helmet solutions using 3D printing or thermoplastic materials for optimal probe placement [17]

The field of NIBS for cognitive enhancement has progressed substantially from basic mechanistic studies to clinically applicable protocols, with robust evidence supporting the efficacy of specific approaches for memory, executive function, and global cognition. The neurophysiological basis for these effects involves the modulation of synaptic plasticity, neural oscillations, and network connectivity, translating into measurable cognitive improvements. Future research directions should focus on optimizing personalization through genetic profiling, baseline cognitive assessment, and real-time neural monitoring; developing more sophisticated multi-site and closed-loop approaches that dynamically adapt to brain states; and establishing standardized protocols for specific patient populations and cognitive domains. As these technologies continue to evolve, the translation from bench to bedside will increasingly enable targeted, effective cognitive enhancement strategies for both clinical populations and cognitive health maintenance.

Non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) has traditionally been conceptualized as a tool for modulating localized cortical activity. The prevailing historical focus on regional excitability, particularly within the motor cortex, has provided foundational insights but fails to capture the full scope of NIBS mechanisms. A paradigm shift is now underway, recognizing that NIBS effects are fundamentally mediated through distributed brain networks rather than isolated brain regions. This transition from a localized to a network-level understanding represents a critical evolution in cognitive enhancement research, reframing NIBS as a tool for manipulating information flow across large-scale neural circuits that support complex cognitive functions.

The state-dependent nature of neural responses to external stimulation underscores that NIBS outcomes depend profoundly on the underlying state of activated brain regions and their integrated networks [18] [19]. This principle forms the cornerstone of modern network-targeted NIBS approaches, suggesting that stimulation is most effective when it synergistically engages the same neural circuits activated by concurrent cognitive tasks or behavioral interventions. As research progresses, the combination of NIBS with neuroimaging techniques has enabled unprecedented insights into global brain network dynamics and organization, moving beyond local excitability changes to understand how stimulation propagates through and reorganizes distributed cognitive circuits [19].

Theoretical Foundations: From Localized Stimulation to Network Engagement

State-Dependency and Circuit Engagement

The fundamental principle of state-dependent stimulation reveals that NIBS does not produce uniform effects but rather interacts dynamically with ongoing neural activity. Research demonstrates that "stimulation outcomes depend upon the state of neural activity in the targeted cortical region" [18]. This interaction has sparked interest in functional targeting approaches that combine NIBS with cognitive tasks engaging the same circuits being stimulated, creating synergistic effects that enhance specific cognitive processes [18]. For instance, the probability of phosphene perception induced by near-threshold TMS of the occipital cortex depends on the phase of ongoing alpha oscillations, illustrating how endogenous brain states gate stimulation effects [19].

Mechanism of Network-Level Effects

At the physiological level, NIBS techniques induce network-level effects through several interconnected mechanisms:

- Trans-synaptic activation: TMS pulses preferentially affect axons with the highest density of ion channels, potentially activating both inhibitory and excitatory neurons across connected networks [19].

- Hebbian plasticity: Protocols like cortico-cortical paired associative stimulation (ccPAS) leverage spike-timing-dependent plasticity to strengthen or weaken connectivity between distinct cortical areas through carefully timed paired pulses [20].

- Network resonance: Rhythmic TMS protocols can entrain native brain oscillations, influencing bidirectional information flow between connected regions [20].

- Stabilization of neural networks: Repeated stimulation sessions across successive days promote synaptic recruitment and shaping/stabilization of new neural networks, particularly with repetitive TMS (rTMS) protocols [20].

The effects of NIBS propagate beyond directly stimulated regions through anatomical and functional connections, reorganizing network dynamics across the brain. This understanding has given rise to the concept of "functional targeting," where NIBS is combined with behavioral tasks that engage specific circuits to maximize relevance and efficacy [18].

Quantitative Evidence: Network-Level Effects of NIBS Across Cognitive Domains

Table 1: Network-Level Effects of NIBS on Cognitive Functions

| Cognitive Domain | Stimulation Protocol | Targeted Network | Effect Size | Key Network Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major Depressive Disorder | rTMS/iTBS | Prefronto-limbic circuits | Remission rates: 30-40% (standard), ~80% (SAINT protocol) [21] [22] | Normalization of fronto-limbic connectivity; Reduced hyperconnectivity in default mode network |

| DEACMP Cognitive Deficits | tDCS/rTMS | Prefronto-parietal-hippocampal | SMD = 1.03 for cognitive function [23] | Improved network efficiency in cognitive control networks; Enhanced functional connectivity |

| Alzheimer's Disease | rTMS/tDCS | Default mode network, fronto-parietal | Variable (low-moderate) | Partial restoration of DMN integrity; Enhanced cross-network coupling |

| Cognitive Enhancement (Healthy) | tDCS/iTBS | Multiple demand network | Small-moderate effects | Increased network integration; Enhanced global efficiency |

Table 2: Moderating Factors in Network-Level NIBS Effects

| Factor | Impact on Network Effects | Evidence Source |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Greater cognitive improvements in patients ≤50 years with DEACMP; ADL improvements more pronounced in >50 years [23] | Systematic review & meta-analysis [23] |

| Stimulation Site | Bilateral stimulation (yin-yang poles) showed superior effects compared to unilateral DLPFC stimulation [23] | DEACMP studies [23] |

| Intervention Duration | ≤20 days showed greater cognitive improvements in DEACMP compared to longer durations [23] | Subgroup analysis [23] |

| Brain State During Stimulation | Phase of ongoing oscillations influences effects; simultaneous cognitive task engagement enhances specificity [18] [19] | State-dependency research [18] [19] |

| Combination with Behavioral Therapy | CBT+NIBS combinations show synergistic effects when engaging common neural circuits [18] | Clinical trials principles [18] |

Methodological Framework: Experimental Protocols for Network-Targeted NIBS

Neuroimaging-Guided Network Targeting

The integration of NIBS with neuroimaging has revolutionized our ability to target and assess network-level effects. The Constrained Network-Based Statistic (cNBS) represents a significant methodological advancement, providing a new level of inference for neuroimaging that pools information within predefined large-scale networks [24]. This approach enhances sensitivity to effect sizes below medium, which accounts for the majority of ground truth effects in neuroimaging studies [24]. The cNBS method addresses the limitation of existing network-based statistics that overlooked "shared membership in large-scale brain networks," enabling more accurate detection of network-level changes following NIBS [24].

Experimental workflow for neuroimaging-guided network targeting:

- Baseline network characterization: Resting-state fMRI and task-based fMRI to identify individual network architecture and target engagement

- Network fingerprinting: Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) to map structural connectivity underlying functional networks

- Target identification: Define stimulation targets based on network nodes or hubs with maximal connectivity to pathological circuits

- Closed-loop stimulation: Real-time fMRI or EEG to guide stimulation timing based on dynamic brain states

- Network outcome assessment: Pre-post stimulation connectivity analysis using cNBS for enhanced statistical inference

Advanced Stimulation Protocols for Network Modulation

Table 3: Advanced NIBS Protocols for Network Modulation

| Protocol | Parameters | Network Effects | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theta-Burst Stimulation (TBS) | Continuous TBS (cTBS): 40s of 50Hz triplets at 5Hz intervals; Intermittent TBS (iTBS): 2s trains every 10s for 190s [20] | cTBS induces LTD-like effects; iTBS induces LTP-like effects [20] | Depression, cognitive enhancement, neurorehabilitation |

| Cortico-cortical Paired Associative Stimulation (ccPAS) | Paired TMS pulses to distinct cortical areas with specific interstimulus intervals [20] | Induces Hebbian plasticity to strengthen or weaken connectivity between targeted regions [20] | Motor learning, cognitive training, network reorganization |

| EEG-guided TMS | TMS pulses triggered by specific oscillatory phases detected via real-time EEG [18] | Enhanced precision through state-dependent stimulation; targets pathological oscillations [18] | Epilepsy, cognitive enhancement, depression |

| Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS) | Sinusoidal currents at specific frequencies (e.g., alpha: 8-12Hz, gamma: 30-50Hz) | Entrainment of native oscillations; modulation of cross-frequency coupling [20] | Memory, attention, cognitive enhancement |

Combined NIBS and Cognitive Training Protocols

The combination of NIBS with cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT) represents a powerful approach for enhancing network-specific effects. Successful implementation requires "synergistic activation of neural circuits" where NIBS and cognitive tasks engage complementary mechanisms within targeted networks [18]. Key methodological considerations include:

- Circuit matchmaking: Pairing specific NIBS protocols with cognitive tasks that engage overlapping neural circuits [18]

- Temporal alignment: Delivering stimulation during specific components of cognitive tasks when target circuits are maximally engaged

- Dynamic adaptation: Adjusting stimulation parameters based on individual network architecture and responsivity

- Homework integration: Addressing the challenge that "the change agent of CBT often occurs outside the CBT session" by developing strategies to impact skills practice between sessions [18]

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for network-level NIBS research

Table 4: Essential Research Toolkit for Network-Level NIBS Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in Network NIBS Research |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulation Equipment | TMS with neuromavigation; tES with high-definition electrodes; Combined TMS-EEG systems | Precise targeting of network nodes; Monitoring immediate network effects; Closed-loop stimulation |

| Neuroimaging Modalities | Resting-state fMRI; Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI); Functional MEG/EEG | Mapping functional and structural connectivity; Identifying individual network nodes; Real-time network monitoring |

| Statistical Analysis Tools | Constrained Network-Based Statistic (cNBS); Graph theory analysis; Dynamic causal modeling | Enhanced inference for network effects; Quantifying global and local network properties; Modeling effective connectivity |

| Cognitive Task Software | Customizable cognitive paradigms (E-Prime, Psychtoolbox); Eye-tracking integration; Physiological monitoring | Engaging specific neural circuits during stimulation; Measuring cognitive network engagement; Monitoring arousal and attention |

| Computational Modeling | Finite element models; Network spreading models; Dose-response estimation | Predicting current flow through brain networks; Simulating network effects of stimulation; Optimizing stimulation parameters |

Visualization of Network Targeting Principles

Diagram 2: Network-level effects of prefrontal stimulation

Future Directions and Clinical Translation

The future of network-level NIBS research lies in advancing personalized, circuit-based interventions. Promising directions include:

- Closed-loop stimulation systems that adapt to real-time brain states using EEG or other biomarkers to optimize timing and parameters [18] [22]

- Multimodal integration of TMS, tES, and focused ultrasound to target different network properties and overcome depth-focality tradeoffs [22]

- Network-based patient stratification using individual connectome fingerprints to predict treatment response and optimize targets [24]

- Multiscale computational models that bridge cellular mechanisms to network-level effects for precise outcome prediction

Clinical translation requires addressing several methodological challenges, including individual variability in network architecture, the dynamic nature of network states, and the complex relationship between network modulation and cognitive outcomes. The emergence of accelerated protocols like SAINT for depression demonstrates the substantial potential of network-targeted approaches, achieving remarkable remission rates of nearly 80% in treatment-resistant patients by optimizing stimulation patterns based on circuit-level understanding [22].

As the field progresses, network-level NIBS approaches offer unprecedented opportunities for developing cognitive enhancement interventions grounded in systems neuroscience principles. By targeting distributed cognitive circuits rather than isolated regions, researchers can develop more effective, personalized interventions that align with the intrinsic network organization of the human brain.

Protocols in Practice: Methodological Strategies and Translational Applications of NIBS

Within the expanding frontier of non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) for cognitive enhancement, two techniques have generated substantial evidence for modulating neural circuits: high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and anodal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). The therapeutic rationale for these modalities is grounded in their capacity to induce neuroplasticity and modulate the oscillatory activity that underpins cognitive processes. In Alzheimer's disease (AD), for instance, pathological hallmarks like amyloid plaques and tau tangles disrupt synaptic function and neural oscillations, leading to network dysfunction and memory impairments [25]. Targeting these dysregulated oscillations has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy, with both rTMS and tDCS demonstrating efficacy in restoring oscillatory balance and enhancing cognitive outcomes [25]. This guide details the established protocols for these techniques, framing them within the broader thesis that targeted neuromodulation represents a potent tool for probing and enhancing specific cognitive domains in both pathological and healthy populations.

High-Frequency Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS)

Mechanism of Action: rTMS utilizes electromagnetic induction to generate a focused, time-varying magnetic field that passes painlessly through the scalp and skull. This magnetic field induces a secondary electrical current in the underlying cortical tissue, which is sufficient to depolarize neurons [3]. When applied in repetitive trains (rTMS), it can modulate cortical excitability beyond the stimulation period. The frequency of stimulation is a critical determinant of its neurophysiological effect: high-frequency rTMS (typically defined as ≥ 5 Hz) produces a sustained increase in cortical excitability within the targeted region [3] [26]. This excitatory effect is believed to result from long-term potentiation (LTP)-like mechanisms, synaptogenesis, and the modulation of functional brain networks [25].

Anodal Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS)

Mechanism of Action: tDCS involves the application of a weak, constant direct current (typically 1-2 mA) to the scalp via two or more electrodes. The primary mechanism is sub-threshold, meaning it does not directly trigger action potentials. Instead, the current flow alters the resting membrane potential of neurons: anodal tDCS typically depolarizes and increases the likelihood of neuronal firing, thereby enhancing cortical excitability [3] [26]. The after-effects of tDCS are thought to involve N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity [25]. Unlike rTMS, tDCS does not induce a magnetic field and is considered a neuromodulator rather than a direct stimulator.

Table 1: Fundamental Mechanisms of High-Frequency rTMS and Anodal tDCS

| Feature | High-Frequency rTMS | Anodal tDCS |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Physical Agent | Time-varying magnetic field | Constant direct current |

| Direct Neural Effect | Induces action potentials | Modulates resting membrane potential |

| Net Effect on Excitability | Increase | Increase |

| Proposed Plasticity Mechanism | LTP-like | NMDA receptor-dependent |

| Spatial Focality | High (focused on a cortical target) | Moderate (broader field under electrode) |

| Temporal Resolution | High (can be time-locked to tasks) | Low (general background modulation) |

Established Protocols for Cognitive Enhancement

The efficacy of both rTMS and tDCS is highly dependent on specific stimulation parameters. The following protocols are synthesized from recent meta-analyses and clinical studies.

Protocol Specifications for rTMS

High-frequency rTMS protocols for cognitive enhancement, particularly in memory domains, often target hubs within the frontal-parietal network or the default mode network (DMN) [25]. A recent meta-analysis confirmed the efficacy of rTMS for memory deficits in Alzheimer's disease, with a standardized mean difference (SMD) of 0.44 (p = 0.001) compared to sham stimulation [3]. Subgroup analysis revealed that stimulation of the frontal regions (e.g., dorsolateral prefrontal cortex - DLPFC) was particularly effective, yielding an SMD of 0.61 (p < 0.001) [3].

Table 2: Established High-Frequency rTMS Protocol for Cognitive Enhancement

| Parameter | Established Protocol | Variations & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Target Frequency | ≥ 5 Hz (often 10-20 Hz) [3] | 10 Hz is among the most common and studied frequencies. |

| Stimulation Target | Frontal regions (e.g., left DLPFC) [3] | Targeting is often guided by neuronavigation systems based on individual MRI. |

| Intensity | 100%-120% of resting motor threshold (rMT) | rMT is determined by single-pulse TMS over the primary motor cortex. |

| Pulses per Train | 20-50 pulses | Dependent on frequency and train duration. |

| Inter-Train Interval (ITI) | 20-30 seconds | Allows the neural tissue to recover and prevents seizure risk. |

| Sessions per Day | 1 | Multiple daily sessions (e.g., SAINT protocol for depression) are being explored. |

| Total Sessions | 10-20+ sessions over 2-4 weeks | Longer treatment durations are associated with more sustained effects. |

| Concurrent Activity | Often paired with cognitive training [3] | The stimulation is intended to prime the brain for enhanced learning. |

Protocol Specifications for Anodal tDCS

For anodal tDCS, the meta-analysis by Fernandes et al. reported a significant, though smaller, positive effect on memory in AD patients (SMD=0.20, p=0.04) [3]. The optimal site for tDCS was distinct from rTMS, with the temporal regions (e.g., temporal cortex) showing the greatest efficacy (SMD=0.32, p=0.04) [3]. A broader trans-diagnostic meta-analysis also found that tDCS produced a small but significant effect on working memory (ES=0.17, p=0.021) and attention/vigilance (ES=0.20, p=0.020) across various brain disorders [27].

Table 3: Established Anodal tDCS Protocol for Cognitive Enhancement

| Parameter | Established Protocol | Variations & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Current Intensity | 1-2 mA [3] | 2 mA is common in recent studies for stronger modulation. |

| Electrode Montage | Anode over target (e.g., temporal cortex); cathode over contralateral supraorbital area or another extra-cephalic/inactive site. | Bilateral montages (e.g., anodal-left/cathodal-right DLPFC) are also used for other domains [12]. |

| Electrode Size | 25-35 cm² | Larger sizes reduce current density and improve comfort. |

| Stimulation Duration | 20-30 minutes per session | Longer durations can induce longer-lasting plasticity. |

| Sessions per Day | 1 | |

| Total Sessions | 10-20+ sessions over 2-4 weeks | Multiple sessions are typically required for lasting effects. |

| Ramp Up/Down | 30-60 seconds at beginning and end | Minimizes cutaneous sensations. |

| Concurrent Activity | Frequently paired with cognitive training or rehabilitation exercises [3] | The stimulation creates a permissive state for neuroplasticity during task performance. |

Quantitative Data Synthesis and Cognitive Outcomes

The effects of these protocols have been quantified across multiple cognitive domains and patient populations. The tables below summarize key quantitative findings from meta-analyses and studies.

Table 4: Quantitative Efficacy of rTMS and tDCS on Cognitive Domains (Meta-Analysis Data)

| Cognitive Domain | Technique | Effect Size (Hedges' g/SMD) | P-value | Population | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memory | rTMS | SMD = 0.44 | 0.001 | Alzheimer's Disease | [3] |

| Memory (Frontal Target) | rTMS | SMD = 0.61 | < 0.001 | Alzheimer's Disease | [3] |

| Memory | tDCS | SMD = 0.20 | 0.04 | Alzheimer's Disease | [3] |

| Memory (Temporal Target) | tDCS | SMD = 0.32 | 0.04 | Alzheimer's Disease | [3] |

| Working Memory | TMS | ES = 0.17 | 0.015 | Trans-diagnostic (Brain Disorders) | [27] |

| Working Memory | tDCS | ES = 0.17 | 0.021 | Trans-diagnostic (Brain Disorders) | [27] |

| Attention/Vigilance | tDCS | ES = 0.20 | 0.020 | Trans-diagnostic (Brain Disorders) | [27] |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

A standard experimental workflow for a clinical trial or research study employing these techniques involves several key stages, from screening to outcome assessment. The process integrates neurophysiological principles with practical experimental design.

The biological pathway through which high-frequency rTMS and anodal tDCS exert their effects involves the induction of neuroplasticity and the modulation of network activity. This pathway is foundational to the cognitive enhancements observed.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of the protocols described requires a suite of specialized equipment and methodological tools. The following table details the key components of a research-grade NIBS setup for cognitive studies.

Table 5: Essential Research Materials and Equipment for rTMS/tDCS Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| MRI-Guided Neuronavigation System | Tracks head and coil/electrode position in real-time, co-registering them to the participant's structural MRI to ensure precise and consistent targeting across sessions. | Critical for accurately targeting the DLPFC in rTMS studies or the temporal cortex in tDCS studies. |

| rTMS Device with Cooled Coil | Generates the high-intensity, rapidly changing magnetic pulses. A cooled coil (e.g., figure-of-eight) allows for high-frequency protocols without overheating. | Used to deliver the 10-20 Hz stimulation trains at 100-120% rMT to the frontal cortex. |

| tDCS Device & Electrodes | Generates a constant, low-current flow. Includes saline-soaked sponge electrodes or conductive rubber electrodes with appropriate interfaces. | Used to deliver 1-2 mA anodal stimulation for 20-30 minutes via the specified electrode montage. |

| Sham Stimulation Equipment | For blinding. For rTMS, this may be a sham coil that mimics sound and sensation without delivering significant magnetic energy. For tDCS, a brief ramp-up/ramp-down current is often used. | Essential for designing a double-blind, sham-controlled RCT, the gold standard in the field. |

| Electroencephalography (EEG) | Measures millisecond-scale electrical brain activity. Used to understand how TMS/tDCS alters brain rhythms (oscillations) and connectivity. | Paired with TMS to get a direct window into how treatment alters brain activity [11]. |

| Cognitive Task Software | Presents standardized or custom-designed cognitive tasks (e.g., n-back, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test) to assess specific cognitive domains before and after stimulation. | Used during baseline, post-stimulation, and follow-up assessments to quantitatively measure changes in memory, attention, etc. [3]. |

| Resting Motor Threshold (rMT) Kit | For rTMS, this involves EMG equipment to measure motor evoked potentials (MEPs) from a hand muscle to determine the minimal TMS intensity required to elicit a response, used for calibrating stimulus intensity. | Used at the beginning of an rTMS study to individualize the stimulation intensity (e.g., 120% of rMT). |

| 5-Methoxypyrimidine-4,6-diamine | 5-Methoxypyrimidine-4,6-diamine | 5-Methoxypyrimidine-4,6-diamine (C5H8N4O) is a chemical compound for research use only (RUO). It is not for human or veterinary use. |

| 2-Pentylquinoline-4-carbothioamide | 2-Pentylquinoline-4-carbothioamide | High-purity 2-Pentylquinoline-4-carbothioamide for research applications. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) has emerged as a promising therapeutic modality for cognitive enhancement in various neurological conditions. This technical guide synthesizes current evidence on the clinical application of NIBS techniques—primarily repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS)—for cognitive deficits in Alzheimer's disease (AD), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and post-stroke cognitive impairment (PSCI). As pharmacological interventions for these conditions demonstrate limited efficacy, NIBS offers a novel approach to modulating neural plasticity and network connectivity to improve cognitive function. This review examines efficacy data, detailed methodologies, and emerging protocols to guide researchers and clinical translation efforts.

Quantitative Efficacy Data

Cognitive Outcomes in Alzheimer's Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment

Table 1: Effects of NIBS on Cognitive Domains in AD/MCI (Umbrella Review Data)

| Cognitive Domain | NIBS Technique | Standardized Mean Difference (SMD) | 95% Confidence Interval | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Cognition (Short-term) | rTMS | 0.44 | 0.02 - 0.86 | p < 0.05 |

| Global Cognition (Long-term) | rTMS | 0.29 | 0.07 - 0.50 | p < 0.05 |

| Language | rTMS | 1.64 | 1.22 - 2.06 | p < 0.001 |

| Executive Function | rTMS | 1.64 | 0.18 - 0.83 | p < 0.05 |

| Executive Function | tDCS | 0.39 | 0.08 - 0.71 | p < 0.05 |

| Memory | tDCS | 0.60 | 0.32 - 0.89 | p < 0.001 |

Source: J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2025;22(1):22 [16]

Table 2: Effects of NIBS Combined with Cognitive Training in AD/MCI

| Intervention | Population | Cognitive Domain | SMD | 95% CI | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIBS + CT | AD/MCI | Global Cognition | 0.52 | 0.18 - 0.87 | p = 0.003 |

| rTMS + CT | AD/MCI | Global Cognition | 0.46 | 0.14 - 0.78 | p = 0.005 |

| NIBS + CT | AD | Global Cognition | 0.77 | 0.19 - 1.35 | p = 0.01 |

| tDCS + CT | AD/MCI | Language | 0.29 | 0.03 - 0.55 | p = 0.03 |

| rTMS + CT (Follow-up) | AD/MCI | Global Cognition | 0.55 | 0.09 - 1.02 | p = 0.02 |

Source: Alzheimers Res Ther. 2024;16:140 [28]

Cognitive Outcomes in Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment

Table 3: Multi-Site NIBS Efficacy in Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment

| Outcome Measure | Mean Difference | 95% CI | Statistical Significance | Heterogeneity (I²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) | 1.84 | 1.21 - 2.48 | p < 0.00001 | 36% |

| Clock Drawing Test (CDT) | 1.65 | 0.77 - 2.53 | p = 0.0003 | 54% |

| Trail Making Test (TMT) | 4.20 | 2.71 - 5.69 | p < 0.00001 | 14% |

| Digit Span Test Forward | 0.94 | -1.11 - 2.98 | p = 0.37 | 97% |

| Digit Span Test Backward | 0.03 | -0.24 - 0.29 | p = 0.85 | 0% |

| Modified Barthel Index | 3.71 | -4.77 - 12.20 | p = 0.39 | 75% |

Source: Front Hum Neurosci. 2025;19:1583566 [15] [29]

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard rTMS Protocol for Alzheimer's Disease

Stimulation Parameters:

- Target Area: Left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) localized using EEG 10-20 system (F3 position) or neuronavigation

- Frequency: 10-20 Hz for excitatory stimulation

- Intensity: 80-120% of resting motor threshold (RMT)

- Pulses per Session: 1000-3000 pulses

- Session Duration: 20-30 minutes

- Treatment Course: 5 sessions per week for 4-6 weeks

- Coil Type: Figure-of-eight coil for focused stimulation

Cognitive Training Integration:

- CT begins concurrently with rTMS application

- Tasks target multiple domains: memory, executive function, language

- Computerized cognitive platforms allow standardized administration

- Difficulty adapts to patient performance level

tDCS Protocol for Mild Cognitive Impairment

Stimulation Parameters:

- Electrode Placement: Anodal over left DLPFC (F3), cathodal over right supraorbital region

- Current Intensity: 1-2 mA

- Session Duration: 20-30 minutes

- Ramp-up/Ramp-down: 30-60 seconds

- Treatment Course: 5 sessions weekly for 3-6 weeks

- Electrode Size: 25-35 cm² for balanced current density

Cognitive Training Synergy:

- CT administered during tDCS stimulation to leverage enhanced plasticity

- Focus on domain-specific deficits identified through baseline assessment

- Incorporates real-life functional tasks for ecological validity

Multi-Site NIBS Protocol for Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment

Network-Targeted Approach:

- Rationale: Engage multiple nodes of cognitive networks simultaneously