Neuroimaging Data Sharing Platforms: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive guide to neuroimaging data sharing platforms, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals.

Neuroimaging Data Sharing Platforms: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to neuroimaging data sharing platforms, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles and major repositories that form the backbone of open neuroscience. The guide details practical methodologies for data submission, standardization, and application in drug development pipelines, including the use of AI and machine learning. It also tackles significant troubleshooting challenges, such as navigating data privacy regulations like GDPR and HIPAA, mitigating re-identification risks, and ensuring ethical data use. Finally, it offers a framework for the validation and comparative analysis of different platforms and data sources, emphasizing the importance of representativeness and bias mitigation to ensure robust and generalizable research outcomes.

The Landscape of Neuroimaging Repositories: Principles, Platforms, and Drivers

The Scientific and Ethical Imperative for Data Sharing

Neuroimaging data are crucial for studying brain structure and function and their relationship to human behaviour, but acquiring high-quality data is costly and demands specialized expertise [1]. To address these challenges and enable the pooling of datasets for larger, more comprehensive studies, the field has increasingly embraced open science practices, including the sharing of publicly available datasets [1]. Data sharing accelerates scientific advancement, enables the verification and replication of findings, and allows more efficient use of public investment and research resources [2]. It is not only a scientific imperative but also an ethical duty to honor the contributions of research participants and maximize the benefits of their efforts [2]. However, sharing human neuroimaging data raises critical ethical and legal issues, particularly concerning data privacy, while researchers also face significant technical challenges in accessing and preparing such datasets [1] [2]. This article examines the current landscape of neuroimaging data sharing, focusing on the platforms, protocols, and ethical frameworks that support this scientific imperative.

The Quantitative Landscape of Neuroimaging Data Sharing

The volume of shared neuroimaging data has greatly increased during the last few decades, with numerous data sharing initiatives and platforms established to promote research [2]. The following table summarizes key characteristics of major neuroimaging data repositories and initiatives.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Neuroimaging Data Repositories and Initiatives

| Repository/Initiative | Primary Focus | Data Types | Sample Characteristics | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK Biobank (UKB) [1] [3] | Large-scale biomedical database | sMRI, DWI, fMRI, genetics, health factors | ~500,000 adult participants | Population-based, extensive phenotyping |

| Human Connectome Project (HCP) [1] [3] | Mapping human brain connectivity | sMRI, fMRI, DWI, MEG | 1,200 healthy adults | High-resolution data, advanced acquisition protocols |

| Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) [3] [4] | Alzheimer's disease progression | MRI, PET, genetics, cognitive measures | Patients with Alzheimer's, MCI, and healthy controls | Longitudinal design, focused on disease biomarkers |

| OpenNeuro [1] | General-purpose neuroimaging archive | BIDS-formatted MRI, EEG, MEG, iEEG | Diverse datasets from multiple studies | BIDS compliance, open access |

| Dyslexia Data Consortium (DDC) [4] | Reading development and disability | MRI, behavioral, demographic data | Participants with dyslexia and typical readers | Specialized focus, emphasis on data harmonization |

These repositories illustrate different models for data sharing, from broad population-based studies like UK Biobank to specialized collections like the Dyslexia Data Consortium. The trend is toward increasingly large sample sizes and multimodal data integration, combining imaging with genetic, behavioral, and clinical information [3].

Ethical and Regulatory Framework

Neuroimaging data sharing operates within a complex ethical and regulatory landscape designed to balance scientific progress with participant protection.

Core Ethical Principles

The foundation for ethical data sharing rests on three core principles from the Belmont Report [2]:

- Respect for Persons: This requires informed consent from participants. In open data sharing, where future analyses cannot be fully specified, this often necessitates broad consent that allows a range of possible secondary analyses [2].

- Beneficence: Researchers must minimize risks of harm and maximize potential benefits. This requires careful consideration of both the probability and magnitude of potential harm from data sharing [2].

- Justice: This principle emphasizes the fair distribution of benefits and burdens of research, promoting equitable access to research participation and outcomes [2].

Regulatory Considerations and Privacy Risks

Data sharing must comply with regulations such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) in the USA and the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the EU [1]. A significant challenge arises from advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning, which pose heightened risks to data privacy through techniques like facial reconstruction from structural MRI data, potentially invalidating conventional de-identification methods such as defacing [2].

Table 2: Ethical Considerations and Mitigation Strategies in Neuroimaging Data Sharing

| Ethical Concern | Current Mitigation Strategies | Emerging Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Informed Consent | Broad consent forms; Dynamic consent approaches; Sample templates (Open Brain Consent) [1] [2] | Obtaining meaningful consent for unforeseen future uses of data |

| Privacy & Confidentiality | Removal of direct identifiers; Defacing structural images; Data use agreements [2] | Re-identification risks from AI/ML techniques; Cross-border data governance |

| Motivational Barriers | Grace periods before data release; Data papers and citation mechanisms; Academic credit for data sharing [2] | Integration of data sharing into academic promotion criteria |

| Data Security | Secure data governance techniques; Authentication systems; Federated data analysis models [1] [4] | Balancing security with accessibility and collaborative potential |

Platforms and Technical Infrastructure for Data Sharing

Several platforms have been developed to address the technical and infrastructural challenges of neuroimaging data sharing.

The Neurodesk Platform

Neurodesk is an open-source, community-driven platform that provides a containerized data analysis environment to facilitate reproducible analysis of neuroimaging data [1]. It supports the entire open data lifecycle—from preprocessing to data wrangling to publishing—and ensures interoperability with different open data repositories using standardized tools [1]. Neurodesk's flexible infrastructure supports both centralized and decentralized collaboration models, enabling compliance with varied data privacy policies [1].

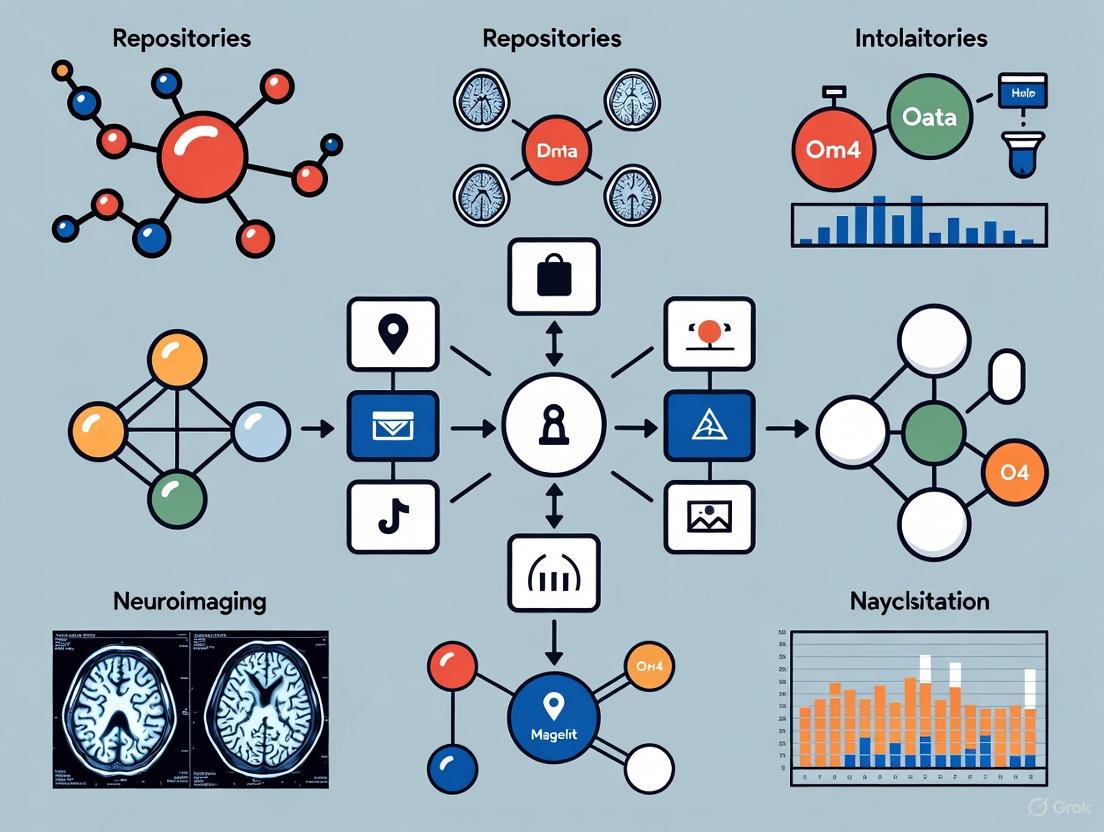

Neurodesk Data Sharing Workflow

Specialized Repositories: Dyslexia Data Consortium

The Dyslexia Data Consortium (DDC) addresses a critical need by providing a specialized platform for sharing data from neuroimaging studies on reading development and disability [4]. The platform's system architecture supports four main functionalities [4]:

- Data Sharing: A multi-service pipeline for data upload, validation, and standardization.

- Data Download: Secure access to standardized datasets.

- Data Metrics: Tools for assessing data quality and characteristics.

- Data Quality & Privacy: Implementation of privacy safeguards and quality checks.

The DDC is built on the foundational principle of adhering to the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) standard, which offers a standardized directory structure and file-naming convention for organizing neuroimaging and related behavioral data [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Standardization and BIDS Conversion Protocol

Standardizing data into BIDS format is a critical first step for ensuring interoperability and reproducibility across studies.

Table 3: BIDS Conversion Tools Available in Neurodesk

| Tool | Primary Features | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| BIDScoin [1] | Interactive GUI; User-friendly conversion | Researchers preferring point-and-click interface without coding |

| heudiconv [1] | Highly flexible; Python scripting interface | Complex conversion workflows requiring custom customization |

| dcm2niix [1] | Efficient DICOM to NIfTI conversion; JSON sidecar generation | Foundation for BIDS conversion; rapid image conversion |

| sovabids [1] | EEG data focus; Python-based | Studies involving electrophysiological data |

Protocol: BIDS Conversion Using Neurodesk

- Data Organization: Begin with raw DICOM files organized by subject and session.

- Tool Selection: Choose an appropriate BIDS conversion tool based on data complexity and user expertise:

- Conversion Execution: Run the selected conversion tool to generate NIfTI images with JSON sidecar files containing metadata.

- Validation: Use the BIDS validator to ensure compliance with standards before sharing or analysis.

Data Processing and Analysis Protocols

Neurodesk provides containerized versions of major processing pipelines to ensure reproducibility:

Protocol: Structural MRI Processing for Voxel-Based Morphometry

- Data Input: BIDS-formatted structural T1-weighted images.

- Processing Pipeline: Utilize the CAT12 toolbox available within Neurodesk for:

- Tissue segmentation into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid

- Spatial normalization to standard stereotactic space

- Modulation to preserve tissue volume information

- Smoothing to improve signal-to-noise ratio [1]

- Quality Control: Review processed images for segmentation and normalization accuracy.

- Statistical Analysis: Conduct voxel-wise statistical tests using Python-based tools or SPM.

Protocol: Functional MRI Preprocessing

- Data Input: BIDS-formatted functional and structural images.

- Processing Pipeline: Execute fMRIPrep for robust and standardized preprocessing:

- Head-motion correction

- Slice-timing correction

- Spatial normalization to standard space

- Artefact detection [1]

- Quality Assessment: Review fMRIPrep-generated HTML reports for data quality.

- First-Level Analysis: Model BOLD response to experimental conditions.

Data De-identification and Sharing Protocol

Protocol: Preparing Data for Public Sharing

- De-identification:

- Repository Selection: Choose an appropriate repository based on data type and sharing requirements:

- Data Upload: Use integrated tools like DataLad for efficient version-controlled data transfer to repositories [1].

- Documentation: Provide comprehensive metadata and documentation describing dataset contents and collection procedures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Tools for Neuroimaging Data Sharing and Analysis

| Tool/Category | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Containerization Platforms | Creates reproducible software environments; eliminates dependency conflicts | Neurodesk [1] |

| Data Standardization Tools | Converts diverse data formats to standardized structures (BIDS) | BIDScoin, heudiconv, dcm2niix [1] |

| Processing Pipelines | Provides standardized, reproducible analysis workflows | fMRIPrep, CAT12, QSMxT [1] |

| Data Transfer Tools | Manages version-controlled data sharing between repositories and local systems | DataLad [1] |

| De-identification Software | Protects participant privacy by removing identifiable features | pydeface [1] |

| Computational Environments | Provides scalable computing resources for large dataset analysis | JupyterHub, PyTorch, HPC clusters [4] |

| Quality Control Frameworks | Assesses data quality and processing outcomes | MRIQC [1], Deep learning models for skull-stripping detection [4] |

Research Workflow with Essential Tools

The scientific and ethical imperative for neuroimaging data sharing is clear: it accelerates discovery, enhances reproducibility, and maximizes the value of research participants' contributions and public investment. Platforms like Neurodesk and specialized repositories like the Dyslexia Data Consortium are addressing the technical challenges through containerized environments, standardized data structures, and flexible collaboration models that can accommodate varied data privacy policies [1] [4]. However, ethical challenges remain, particularly regarding privacy risks from advancing re-identification technologies and the need for international consensus on data governance [2]. The future of neuroimaging data sharing lies in continued development of secure, scalable infrastructure that balances openness with responsibility, supported by ethical frameworks that promote equity and trust in the scientific process. As these platforms and protocols evolve, they will further democratize access to neuroimaging data, enabling more inclusive and impactful brain research.

Modern neuroscience research, particularly in the domains of neurodegenerative disease and brain aging, is increasingly powered by large-scale, open-access neuroimaging data repositories. These repositories have become indispensable resources for developing and validating machine learning models, identifying early disease biomarkers, and facilitating reproducible research across institutions. The UK Biobank (UKBB), Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), and OpenNeuro represent three cornerstone repositories that serve complementary roles in the global research ecosystem. Each platform addresses specific research needs, from population-scale biobanking to focused clinical cohort studies and general-purpose data sharing, collectively enabling breakthroughs in our understanding of brain structure and function. The emergence of platforms like Neurodesk further enhances the utility of these repositories by providing containerized analysis environments that standardize processing workflows across diverse datasets [1]. This protocol outlines the practical application of these repositories in contemporary neuroimaging research, with specific methodological details for conducting cross-repository validation studies.

Repository Characteristics and Access Protocols

The major neuroimaging repositories differ significantly in their data composition, access procedures, and primary research applications. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for researchers selecting appropriate datasets for their specific study questions. The table below provides a systematic comparison of key repository characteristics:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Neuroimaging Data Repositories

| Repository | Primary Focus | Data Types | Access Process | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK Biobank [5] [6] | Large-scale population study | Multimodal imaging (T1-weighted MRI, dMRI, fMRI), genetics, lifestyle factors, health outcomes | Registration and approval required; data access agreement | Unprecedented scale (imaging data for 100,000 participants), extensive phenotyping, longitudinal health data |

| ADNI [7] [8] [9] | Alzheimer's disease and cognitive aging | Longitudinal clinical, imaging, genetic, biomarker data | Online application with review process (~2 weeks); Data Use Agreement required | Deep phenotyping for Alzheimer's, standardized longitudinal protocols, biomarker data (amyloid, tau) |

| OpenNeuro [10] [11] | General-purpose neuroimaging archive | Raw brain imaging data (fMRI, MRI, EEG, MEG) in BIDS format | Immediate public access for open datasets; no approval required | Open licensing (CC0), BIDS standardization, supports dataset versioning and embargoes |

| Neurodesk [1] | Analysis platform and tool ecosystem | Containerized neuroimaging software, processing pipelines | Open-source platform; downloadable or cloud-based access | Reproducible processing environments, tool interoperability, flexible deployment (local/HPC/cloud) |

Experimental Protocols for Cross-Repository Validation Studies

Protocol 1: Brain Age Prediction with UK Biobank and External Validation

Recent research demonstrates that brain age models trained on UK Biobank data can effectively generalize to external clinical datasets when proper methodological approaches are employed [12]. The following protocol outlines the key steps for developing and validating such models:

Data Processing and Feature Extraction: Process T1-weighted MRI scans through the FastSurfer pipeline to transform images into a conformed space for deep learning approaches. Alternatively, extract image-derived phenotypes (IDPs) for traditional machine learning methods [12].

Model Training and Selection: Implement a comprehensive pipeline to train and compare a broad spectrum of machine learning and deep learning architectures. Studies indicate that penalized linear models adjusted with Zhang's methodology often achieve optimal performance, with mean absolute errors under 1 year in external validation [12].

Cross-Repository Validation: Validate trained models on external datasets such as ADNI and NACC (National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center). Evaluate performance metrics including mean absolute error (MAE) for age prediction and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) for disease classification [12].

Handling Demographic Biases: Apply resampling strategies for underrepresented age groups to reduce prediction errors across all age brackets. Assess model robustness across cohort variability factors including ethnicity and MRI machine manufacturer [12].

Biomarker Application: Apply the validated brain age gap (difference between predicted and chronological age) as a biomarker for neurodegenerative conditions. High-performing models can achieve AUROC > 0.90 in distinguishing healthy individuals from those with dementia [12].

Protocol 2: Identifying Pre-Diagnostic Alzheimer's Disease Across Cohorts

The following protocol outlines a methodology for identifying individuals with pre-diagnostic Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging phenotypes across different datasets:

Model Development in Research Cohorts: Train a Bayesian machine learning neural network model to generate an AD neuroimaging phenotype using structural MRI data from the ADNI cohort. Optimize model parameters to achieve high classification accuracy (e.g., AUC 0.92, PPV 0.90, NPV 0.93) using a defined probability cut-off (e.g., 0.5) [13].

Real-World Validation: Validate the trained model in an independent, heterogeneous real-world dataset such as NACC, which includes a broader range of cognitive disorders and imaging quality. Expect moderate performance degradation (e.g., AUC 0.74) reflective of clinical reality [13].

Application to Asymptomatic Populations: Apply the validated model to a healthy population (e.g., UK Biobank) to identify individuals with AD-like neuroimaging phenotypes despite no clinical diagnosis. Correlate the AD-score with cognitive performance measures to establish functional significance [13].

Risk Factor Analysis: Investigate modifiable risk factors (e.g., hypertension, smoking) in the identified at-risk cohort to identify potential intervention targets [13].

The workflow for this cross-repository analysis can be visualized as follows:

The Neurodesk Platform: Enabling Reproducible Cross-Repository Analysis

Neurodesk addresses a critical challenge in cross-repository research: maintaining consistent processing environments across different datasets [1]. The platform provides:

Containerized Analysis Environment: A modular, scalable platform built on software containers that enables on-demand access to a comprehensive suite of neuroimaging tools [1].

Data Standardization Support: Integrated tools for BIDS conversion (dcm2niix, heudiconv, bidscoin) to ensure data compatibility across repositories [1].

Flexible Collaboration Models: Support for both centralized (shared cloud instance) and decentralized (local processing with shared derivatives) collaboration models to accommodate varied data privacy policies [1].

Repository Interoperability: Simplified data transfer to and from public repositories (OpenNeuro, OSF) through integrated tools like DataLad, as well as support for various cloud storage solutions [1].

The data collaboration models supported by Neurodesk can be visualized as follows:

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Neuroimaging Analysis

Table 2: Essential Software Tools for Cross-Repository Neuroimaging Analysis

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Format Standardization | dcm2niix, Heudiconv, BIDScoin, sovabids [1] | DICOM to BIDS conversion; data organization | Ensuring compatibility across repositories; preparing data for sharing |

| Structural MRI Processing | FastSurfer, CAT12, FreeSurfer [12] [1] | Volumetric segmentation; cortical surface reconstruction | Feature extraction for machine learning; brain age prediction |

| fMRI Preprocessing | fMRIPrep, MRIQC [1] | Automated preprocessing of functional MRI data | Standardizing functional connectivity analyses |

| Containerization Platforms | Neurodesk, Docker [1] | Reproducible analysis environments | Maintaining consistent tool versions across studies |

| Data Transfer and Versioning | DataLad, Git [1] [11] | Dataset versioning; efficient data transfer | Managing large datasets; collaborating across institutions |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | PyTorch, scikit-learn [12] [1] | Developing predictive models | Brain age prediction; disease classification |

The synergistic use of global neuroimaging repositories—UK Biobank, ADNI, and OpenNeuro—represents a paradigm shift in neuroscience research methodology. Through standardized protocols for cross-repository validation and platforms like Neurodesk that ensure analytical reproducibility, researchers can develop more generalizable and clinically relevant biomarkers. The methodologies outlined in this application note provide a framework for leveraging these complementary resources to advance our understanding of brain aging and neurodegenerative disease, ultimately accelerating the development of early intervention strategies.

The field of human neuroimaging has evolved into a data-intensive science, where the ability to share data accelerates scientific discovery, reinforces open scientific inquiry, and maximizes the return on public research investment [2]. The movement towards Open Science necessitates robust infrastructure and community-agreed standards to overcome challenges in data collection, management, and large-scale analysis [14]. This Application Note details the critical infrastructure and standards that underpin modern neuroinformatics, focusing on the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) for data organization, cloud computing platforms for scalable analysis, and the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles as a framework for data stewardship. Adherence to these protocols is essential for building reproducible, collaborative, and ethically conducted neuroimaging research that can translate into clinical applications and drug development.

The Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS): A Community Standard

BIDS Specifications and Impact

The Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) is a simple and intuitive standard for organizing and describing complex neuroimaging data [15]. Since its initial release in 2016, BIDS has revolutionized neuroimaging research by creating a common language that enables researchers to organize data in a consistent manner, thereby facilitating sharing and reducing the cognitive overhead associated with using diverse datasets [16]. The standard is maintained by a global open community and is supported by organizations like the International Neuroinformatics Coordinating Facility (INCF) [16].

The core BIDS specification provides a definitive guide for file naming, directory structure, and the required metadata for a variety of brain imaging modalities [15]. The ecosystem has expanded to include over 40 domain-specific technical specifications and is supported by more than 200 open datasets on repositories like OpenNeuro [16]. The community actively consults the specifications, with the BIDS website receiving approximately 30,000 annual visits from a large community of neuroscience researchers [16].

Table 1: Core Components of the BIDS Ecosystem

| Component | Description | Example Tools/Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Core Specification | Defines file organization, naming, and metadata for modalities like MRI, MEG, and EEG. | BIDS Specification on ReadTheDocs [15] |

| Extension Specifications | Community-developed extensions for new modalities (e.g., PET, microscopy) and data types. | Over 40 technical specifications [16] |

| Validator Tool | A software tool to verify that a dataset is compliant with the BIDS standard. | bids-validator [16] |

| Sample Datasets | Example BIDS-formatted datasets for testing and reference. | 100+ sample data models in bids-examples [16] |

| Conversion Tools | Software to convert raw data (e.g., DICOM) into a BIDS-structured dataset. | dcm2bids, heudiconv [16] |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing BIDS in a Research Laboratory

Implementing BIDS at the level of the individual research laboratory is the foundational step towards FAIR data. The following protocol outlines the process for converting raw neuroimaging data into a BIDS-compliant dataset.

Protocol 1: BIDS Conversion and Validation

Objective: To convert raw magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data from a scanner output (e.g., DICOM) into a validated BIDS-structured dataset.

Materials and Reagents:

- Raw Imaging Data: DICOM files from an MRI, PET, or other neuroimaging session.

- Computing Environment: A computer with a Unix-based (Linux/macOS) or Windows operating system and Node.js installed.

- Conversion Software: A BIDS conversion tool such as

dcm2bidsorheudiconv. - Validation Tool: The

bids-validator(can be run via command line or online). - Metadata Source: The study protocol document detailing scan parameters.

Procedure:

- Data Export: Transfer DICOM files from the scanner to a secure data management system. Organize files by subject and session if applicable.

- Software Configuration: Install the chosen conversion tool (e.g.,

dcm2bids). Forheudiconv, create a custom heuristic file that maps DICOM series descriptions to BIDS filenames and entities (e.g.,sub-01_ses-01_T1w.nii.gz). - Dataset Structure: Create the root directory for your BIDS dataset. Within it, create the mandatory subdirectories for each subject (e.g.,

sub-01,sub-02) and, for each subject, ases-<label>directory if multiple sessions exist. - Data Conversion: Run the conversion tool. For example, using

dcm2bids: This command will convert the DICOMs for participantsub-01based on the mappings defined inconfig.jsonand output the data into the BIDS directory structure. - Metadata Fulfillment: Populate the dataset-level description files. The

dataset_description.jsonfile is mandatory. Add all required and recommended metadata fields as per the BIDS specification. - Sidecar JSON Files: For each neuroimaging data file (e.g.,

.nii.gz), ensure a corresponding JSON file contains the necessary metadata (e.g.,RepetitionTime,EchoTimefor MRI). - Data Validation: Run the BIDS-validator from the root of the dataset to check for compliance:

- Iteration: Address all errors and warnings reported by the validator. This may involve correcting file names, adding missing metadata, or fixing directory structure issues. Repeat the validation until the dataset passes without errors.

Cloud Computing Platforms for Integrated Neuroimaging

Cloud Platforms and Features

Cloud computing platforms provide a full-stack solution to the challenges of large-scale neuroimaging data management and analysis, offering centralized data storage, high-performance computing, and integrated analysis pipelines [14]. Systems like the Integrated Neuroimaging Cloud (INCloud) seamlessly connect data acquisition from the scanner to data analysis and clinical application, allowing users to manage and analyze data without downloading them to local devices [14]. This is particularly valuable for "mega-analyses" that require pooling data from multiple sites.

A key innovation in platforms like INCloud is the implementation of a brain feature library, which shifts the unit of data management from the raw image to derived image features, such as hippocampal volume or cortical thickness [14]. This allows researchers to efficiently query, manage, and analyze specific biomarkers across large cohorts, accelerating the translation of research findings into clinical tools like computer-aided diagnosis systems (CADS) [14].

Table 2: Comparison of Neuroimaging Data Platforms and Repositories

| Platform | Primary Function | Key Features | Connection to Scanner |

|---|---|---|---|

| INCloud [14] | Full-stack cloud solution for data collection, management, and analysis. | Brain feature library, automatic processing pipelines, connection to CADS. | Yes |

| XNAT [14] | Extensible neuroimaging archive toolkit for data management & sharing. | Flexible data model, supports many image formats, plugin architecture. | Yes |

| OpenNeuro [14] [17] | Public data repository for sharing BIDS-formatted data. | BIDS validation, data versioning, integration with analysis platforms (e.g., Brainlife). | No |

| LONI IDA [14] | Image and data archive for storing, sharing, and processing data. | Supports multi-site studies, data sharing, and pipelines. | No |

| COINS [14] | Collaborative informatics and neuroimaging suite. | Web-based, integrates assessment, imaging, and genetic data. | No |

| NITRC-IR [14] | Neuroimaging informatics tools and resources clearinghouse image repository. | Cloud storage for data and computing resources. | No |

Experimental Protocol: Conducting a Mega-Analysis on a Cloud Platform

This protocol describes the workflow for a researcher to perform a multi-site mega-analysis of a specific brain feature (e.g., hippocampal volume) using a cloud platform with a pre-existing feature library.

Protocol 2: Cloud-Based Feature Mega-Analysis

Objective: To query a cloud-based brain feature library and perform a statistical analysis comparing hippocampal volume across diagnostic groups.

Materials and Reagents:

- Access Credentials: Login credentials for the cloud platform (e.g., INCloud).

- Web Browser: A modern web browser to access the platform's interface.

- Analysis Plan: A predefined statistical model (e.g., ANOVA to test for group differences in hippocampal volume, co-varying for age, sex, and intracranial volume).

Procedure:

- Platform Login & Navigation: Access the cloud platform via a web browser or Secure Shell (SSH) terminal. Navigate to the brain feature library query interface [14].

- Cohort Definition: Use the query tools to define your analysis cohort. Select criteria such as:

- Diagnostic groups (e.g., Healthy Control, Mild Cognitive Impairment, Alzheimer's Disease).

- Demographic ranges (e.g., age 60-85).

- Scanning site/scanner type to manage heterogeneity.

- Feature Selection: Select the brain feature of interest from the library (e.g.,

left_hippocampus_volumeandright_hippocampus_volume). - Data Export Request: Submit a query to export the selected features and associated clinical/demographic covariates (e.g., age, sex, diagnosis, intracranial volume) for the defined cohort. The platform will generate a flat file (e.g., CSV format).

- Statistical Analysis: Transfer the downloaded data file to the platform's cloud computing environment. Execute the pre-planned statistical model using available software (e.g., R, Python). An example R command for a linear model might be:

- Result Interpretation: Review the output of the statistical analysis (e.g., p-values, effect sizes) to interpret the relationship between diagnosis and hippocampal volume after accounting for covariates.

- Computer-Aided Diagnosis (Optional): If the platform is connected to a CADS, the derived model or findings can be fed back to improve the accuracy of objective diagnosis for mental disorders [14].

The FAIR Principles as a Framework for Data Stewardship

FAIR Principles and Implementation

The FAIR principles provide a robust framework for making data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable [17]. These principles are a cornerstone of modern neuroscience data management, designed to meet the needs of both human researchers and computational agents [18]. The implementation of FAIR is a partnership between multiple stakeholders, including laboratories, repositories, and community organizations [17].

Table 3: Implementing FAIR Principles in a Neuroscience Laboratory

| FAIR Principle | Laboratory Practice | Example Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Findable | Use globally unique and persistent identifiers. | Create a central lab registry with unique IDs for subjects, experiments, and reagents [17]. |

| Use rich metadata. | Accompany all data with detailed metadata (e.g., experimenter, date, subject species/strain) [17]. | |

| Accessible | Ensure controlled data access. | Create a centralized, accessible store for data and code under a lab-wide account, not personal drives [17]. |

| Interoperable | Use FAIR vocabularies and community standards. | Adopt Common Data Elements and ontologies. Create a lab-wide data dictionary [17]. Use BIDS and NWB formats [17]. |

| Reusable | Provide comprehensive documentation. | Create a "Read me" file for each dataset with notes for reuse [17]. |

| Document provenance. | Version datasets and document experimental protocols using tools like protocols.io [17]. | |

| Apply clear licenses. | Ensure data sharing agreements are in place and that clinical consents permit sharing of de-identified data [17]. |

Ethical Considerations and the CARE Principles

The drive for open data must be balanced with critical ethical and legal considerations, particularly concerning data privacy and equitable representation. The sharing of human neuroimaging data raises risks to subject privacy, which are heightened by advanced artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques that can potentially re-identify previously de-identified data [2]. Furthermore, global neuroimaging data repositories are often disproportionately funded by and composed of data from high-income countries, leading to significant underrepresentation of certain populations [19]. This imbalance risks hardwiring biases into AI models, which can then exacerbate existing healthcare disparities [19].

While not explicitly detailed in the search results, the CARE Principles (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, and Ethics) for Indigenous Data Governance complement FAIR by emphasizing people and purpose, ensuring that data sharing benefits all communities and respects data sovereignty. This is highly relevant to the ethical challenges identified in neuroimaging [19]. Researchers must navigate a complex regulatory landscape (e.g., GDPR in Europe, HIPAA in the US) and should consider solutions like broad consent and legal prohibitions against the malicious use of data to mitigate privacy risks while promoting data sharing [2].

Integrated Workflow and Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the synergistic relationship between BIDS, Cloud Computing, and the FAIR principles in a streamlined neuroimaging research workflow, from data acquisition to discovery.

Integrated Neuroimaging Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| BIDS Validator | A software tool to verify that a dataset complies with the BIDS standard, ensuring interoperability and reusability [16]. |

| dcm2bids / Heudiconv | Software tools that convert raw DICOM files from the scanner into a BIDS-formatted dataset, standardizing the initial data organization step [16]. |

| Cloud Computing Credits | Allocation of computational resources on platforms like INCloud or other cloud services, enabling access to high-performance computing without local infrastructure [14]. |

| Brain Feature Library | A cloud database of pre-computed imaging-derived features (e.g., volumetric measures); allows for efficient querying and mega-analysis without reprocessing raw data [14]. |

| INCF Standards Portfolio | A curated collection of INCF-endorsed standards and best practices (including BIDS) to guide researchers in making data FAIR [17]. |

| Data Usage Agreement (DUA) | A legal document outlining the terms and conditions for accessing and using a shared dataset, crucial for protecting participant privacy and defining acceptable use [2]. |

| FAIR Data Management Plan | A living document, often required by funders, that describes the life cycle of data throughout a project, ensuring compliance with FAIR principles from the start [17]. |

The transition to open science in neuroimaging presents a complex challenge: balancing the undeniable benefits of data sharing with the legitimate career concerns of individual researchers. While funder mandates and policy pressures provide a strong external push for data sharing, they often fail to address fundamental issues of motivation, recognition, and protection against academic 'scooping' [20] [21]. This creates a compliance gap where researchers may share data minimally without ensuring their reusability, ultimately undermining the scientific value of sharing initiatives [20]. Effective data sharing requires understanding academia as a reputation economy where researchers strategically invest time in activities that advance their careers [21]. This application note synthesizes current evidence and provides structured protocols to align data sharing practices with academic incentive structures, addressing key barriers through practical solutions that transform data sharing from an obligation into a recognized scholarly contribution.

Understanding the current state of data sharing requires examining both the scale of existing resources and the attitudes that drive participation. The following metrics illuminate the infrastructure capacity and sociological factors influencing neuroimaging data sharing.

Table 1: Quantitative Overview of Neuroimaging Data Sharing Landscape

| Category | Metric | Value | Source/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platform Capacity | Public data available on Pennsieve | 35 TB | [22] |

| Total data stored on Pennsieve | 125 TB+ | [22] | |

| Number of datasets on Pennsieve | 350+ | [22] | |

| Researcher Attitudes | Researchers acknowledging data sharing benefits | 83% | Survey of 1,564 academics [21] |

| Researchers who have shared their own data | 13% | Same survey [21] | |

| Main concern: being scooped | 80% | Same survey [21] | |

| Data Reuse Impact | Citation advantage for open data | Up to 50% | Analysis of published studies [23] |

Addressing Key Challenges: Protocols and Solutions

Protocol: Mitigating Scooping Concerns Through Embargoed Data Release

Objective: Establish a structured timeline for data release that protects researchers' primary publication rights while fulfilling sharing obligations.

Background: The fear that other researchers will publish findings from shared data before the original collectors constitutes the most significant barrier to data sharing, cited by 80% of researchers [21]. This protocol creates a managed transition from proprietary to shared status.

Materials:

- Data management platform with access control (e.g., Pennsieve, Neurodesk)

- Digital Object Identifier (DOI) minting service

- Project management tool for timeline tracking

Procedure:

- Pre-registration and DOI Allocation (Month 0-3):

- Register the dataset in a repository immediately upon data collection completion

- Mint a DOI to establish precedence and citability

- Set initial access controls to "private" or "restricted"

Primary Analysis Period (Months 4-24):

- Maintain restricted access while original research team conducts planned analyses

- Prepare comprehensive documentation, codebooks, and metadata

- Develop data use agreements for limited pre-publication sharing

Staged Release Implementation (Months 25-30):

- Release data supporting published manuscripts immediately upon publication

- Gradually expand access to remaining data according to a pre-defined schedule

- Update metadata to reflect publications and proper citation formats

Full Open Access (Month 31+):

- Transition dataset to fully open access

- Maintain curation and respond to user inquiries

- Track citations and reuse metrics for recognition

Validation: Successful implementation results in primary publications from the collecting team before significant third-party use, with proper attribution in subsequent reuse publications [20].

Protocol: Implementing FAIR Data Principles for Maximum Reusability

Objective: Transform raw research data into Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) resources that maintain long-term value.

Background: FAIR principles provide a framework for enhancing data reusability, but implementation requires systematic effort [23]. This protocol operationalizes FAIR principles specifically for neuroimaging data.

Materials:

- BIDS (Brain Imaging Data Structure) validator

- Data dictionary templates

- Metadata standards (e.g., NDA Data Dictionary)

- Data de-identification tools (e.g., pydeface)

Procedure:

- Findability Enhancement:

- Create rich metadata using domain-specific ontologies

- Register datasets in discipline-specific repositories (e.g., OpenNeuro)

- Obtain persistent identifiers (DOIs) through repositories

- Use the Rabin-Karp string-matching algorithm to suggest variable mappings during data harmonization [24]

Accessibility Assurance:

- Implement authentication and authorization where necessary

- Provide clear data access statements in publications

- Use standard communication protocols (API interfaces)

- Offer both web download and programmatic access options

Interoperability Optimization:

Reusability Maximization:

- Provide detailed data provenance documenting processing steps

- Include codebooks with variable definitions and measurement details

- Share analysis code and processing scripts alongside data

- Document data quality metrics and any known limitations

Validation: FAIR compliance can be measured through automated assessment tools and demonstrated by successful reuse in independent studies [22].

Objective: Establish data sharing as a recognized scholarly contribution that advances academic careers through formal credit mechanisms.

Background: In the academic reputation economy, data sharing sees limited adoption because it "receives almost no recognition" compared to traditional publications [21]. This protocol creates a pathway for formal academic recognition of shared data resources.

Materials:

- Data repositories with citation tracking (e.g., Pennsieve, OpenNeuro)

- ORCID researcher profiles

- Academic CV templates

- Promotion and tenure documentation guidelines

Procedure:

- Data Publication Strategy:

- Publish data in repositories that provide citation metrics and download statistics

- Consider data papers in specialized journals (e.g., Scientific Data, Open Health Data)

- Include datasets in publication references using standard citation formats

Academic Portfolio Integration:

- List datasets alongside publications in CVs with clear designation

- Include data citation metrics in promotion and tenure packages

- Document data reuse impact statements noting how shared data enabled other research

Recognition System Advocacy:

- Encourage funding agencies to consider data sharing track records in review

- Advocate for institutional recognition of data publications

- Support "best dataset" awards within research communities

- Implement co-authorship policies for substantial data reuse

Impact Documentation:

- Monitor and document publications arising from shared data

- Track citations of data papers and dataset DOIs

- Collect testimonials from data reusers

- Calculate and report economic value of data reuse where possible

Validation: Success is indicated when data sharing contributions are formally evaluated in hiring, promotion, and funding decisions alongside traditional publications [21].

Visualization of Data Sharing Workflows and Relationships

Data Sharing Implementation Workflow

Stakeholder Motivation Relationships

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Data Sharing

Table 2: Essential Tools for Neuroimaging Data Sharing

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Function | Implementation Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Platforms | Pennsieve, Neurodesk, OpenNeuro | Cloud-based data management, curation, and sharing | Pennsieve supports FAIR data and has stored 125+ TB [22]; Neurodesk enables reproducible analysis via containers [25] |

| Standardization Tools | BIDS validator, dcm2niix, heudiconv | Convert and organize data into BIDS format | Critical for interoperability; OpenNeuro requires BIDS format [22] [25] |

| De-identification | pydeface, MRIQC | Remove personal identifiers from neuroimaging data | Essential for compliance with GDPR/HIPAA; Open Brain Consent provides templates [25] |

| Provenance Tracking | DataLad, version control (Git) | Track data processing steps and changes | Enables reproducibility and documents data history |

| Metadata Management | NDA Data Dictionary, openMINDS | Standardize variable names and descriptions | Required for integration with national databases like NDA [26] |

| Documentation | CSV with data dictionaries, REDCap | Create comprehensive data documentation | Data dictionaries make variables interpretable for reusers [26] |

Transforming neuroimaging data sharing from a mandated obligation to a recognized scholarly contribution requires addressing the fundamental incentive structures of academic research. The protocols and solutions presented here provide a comprehensive framework for researchers, institutions, and funders to align data sharing practices with career advancement goals while maximizing the scientific value of shared data. By implementing managed release schedules, rigorous FAIR principles implementation, and formal academic credit mechanisms, the research community can overcome the central barriers of scooping concerns and lack of recognition. This approach fosters a collaborative ecosystem where data sharing becomes an integral part of the research lifecycle rather than an administrative burden, ultimately accelerating discovery in neuroimaging and beyond.

From Data to Discovery: Practical Workflows and Applications in Research & Development

Neuroimaging data is crucial for studying brain structure and function, but acquiring high-quality data is costly and demands specialized expertise [1]. Data sharing accelerates scientific advancement by enabling the pooling of datasets for larger, more comprehensive studies, verifying findings, and increasing the return on public research investment [2]. The neuroimaging community has increasingly embraced open science, leading to the establishment of numerous data-sharing platforms and repositories [27].

However, sharing human subject data raises critical ethical and legal concerns, primarily regarding participant privacy and confidentiality [2]. The emergence of sophisticated artificial intelligence and facial reconstruction techniques poses heightened risks, potentially undermining conventional de-identification methods [2]. Consequently, researchers must navigate a complex landscape of technical requirements and regulatory frameworks, such as the GDPR in the European Union and HIPAA in the United States [1].

This guide provides a standardized protocol for the secure and ethical sharing of neuroimaging data, covering de-identification, repository submission, and ongoing account management, framed within the broader context of neuroimaging data sharing platforms and repositories research.

Data De-identification: Protocols and Procedures

De-identification is the process of removing or obscuring personal identifiers from data to minimize the risk of participant re-identification. It is a fundamental ethical obligation under the Belmont Report's principle of beneficence, which requires researchers to minimize risks of harm to subjects [2].

Table 1: Common De-identification and Data Standardization Tools

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| pydeface [1] | Defacing of structural MRI | Removes facial features from structural images to protect privacy | Standard practice for structural scans; may not be sufficient alone |

| BIDScoin [1] | BIDS conversion | Interactive GUI for converting DICOMs to BIDS format | Intuitive for users less comfortable with scripting |

| heudiconv [1] | BIDS conversion | Highly flexible DICOM to BIDS converter | Requires Python scripting to run a conversion |

| dcm2niix [1] | DICOM to NIfTI conversion | Converts DICOMs into NIFTIs with JSON sidecar files | Requires additional steps for arranging data in a BIDS structure |

| DataLad [1] | Data management & versioning | Manages data distribution and version control; facilitates upload to repositories | Integrates with data analysis workflows |

Step-by-Step De-identification Protocol

Experimental Protocol 1: Comprehensive Data De-identification

- Objective: To render neuroimaging data non-identifiable while preserving its scientific utility.

- Materials: Raw DICOM or NIfTI neuroimaging data, associated behavioral/clinical data files, de-identification software (e.g., pydeface), BIDS conversion tool (e.g., BIDScoin, heudiconv).

- Procedure:

- Remove Direct Identifiers from Metadata: Scrub all header fields in image files (DICOM or NIfTI) containing direct identifiers such as name, address, medical record number, and date of birth [2]. Use specialized scripts or tool features designed for this purpose.

- Deface Structural Images: Run a defacing tool like pydeface on T1-weighted and other high-resolution structural scans [1]. This algorithmically removes facial features, making the participant unrecognizable while preserving brain anatomy for analysis.

- Anonymize Behavioral and Phenotypic Data: In accompanying spreadsheets or data files, remove any columns with direct identifiers. Replace participant identifiers with a consistent, anonymized code. For dates, consider shifting all dates by a consistent number of days for each participant to preserve temporal relationships without revealing absolute dates.

- Validate De-identification: Perform a quality check by visually inspecting defaced images to ensure no facial tissue remains and that brain tissue is intact. Re-check a sample of file headers and data tables to confirm the removal of all identifiers.

- Regulatory Compliance: This process aligns with data protection regulations like GDPR and HIPAA, which provide safe harbors for de-identified data [1] [2]. Ensure the process complies with the specific approvals granted by your Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the consent provided by participants.

Data Submission to Repositories

Submitting data to a public repository ensures it is findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR) [27]. The Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) has emerged as the community standard for organizing neuroimaging data [1] [27].

Table 2: Selected Neuroimaging Data Repositories

| Repository Name | Data Type / Focus | Key Features | Access Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| OpenNeuro [1] | General purpose neuroimaging | BIDS-validator; integrated with analysis tools; uses DataLad | Open Access |

| Dyslexia Data Consortium (DDC) [4] | Specialized (Reading disability) | Emphasis on data harmonization; integrated processing resources | Controlled Access |

| OSF (Open Science Framework) [1] | General purpose research data | Flexible storage; does not enforce strict data formats | Open & Controlled |

| BrainLife [1] | Neuroimaging data & processing | Offers visualization and processing tools in addition to storage | Open Access |

| ABCD & UK Biobank [4] | Large-scale prospective studies | Rich phenotypic and genetic data alongside neuroimaging | Controlled Access |

Step-by-Step Submission Protocol

Experimental Protocol 2: Data Standardization and Repository Submission

- Objective: To prepare a de-identified dataset for sharing by standardizing its structure and submitting it to a chosen repository.

- Materials: De-identified neuroimaging data, de-identified behavioral data, BIDS validation tool, computing environment with internet access.

- Procedure:

- Organize Data into BIDS Format: Convert your dataset to follow the BIDS specification [1]. This involves:

- Placing NIfTI files in a structured directory hierarchy (e.g.,

sub-01/ses-01/anat/,sub-01/ses-01/func/). - Creating accompanying JSON files for sidecar metadata.

- Generating a dataset description file (

dataset_description.json). - Use tools like BIDScoin, heudiconv, or sovabids to automate this process [1].

- Placing NIfTI files in a structured directory hierarchy (e.g.,

- Validate BIDS Structure: Run the official BIDS-validator (available online or as a command-line tool) on your dataset directory. This checks for compliance with the BIDS standard and identifies any formatting errors that must be corrected before submission.

- Select an Appropriate Repository: Choose a repository based on your data's nature, the repository's focus, its access policies, and its persistence. General-purpose repositories like OpenNeuro are suitable for most data, while specialized repositories like the Dyslexia Data Consortium (DDC) may offer better integration for specific research communities [4].

- Upload Data: Follow the repository's specific upload instructions. This may involve:

- Complete Submission Metadata: Provide rich metadata for your dataset, including title, authors, description, keywords, and funding information. This is critical for making your dataset findable and citable.

- Organize Data into BIDS Format: Convert your dataset to follow the BIDS specification [1]. This involves:

Account and Data Management

Effective management of your repository account and shared data ensures long-term impact and compliance.

Collaboration and Access Models

Repositories typically support different collaboration models to accommodate varied data privacy policies [1]:

- Centralized Collaboration: A Neurodesk-managed cloud instance allows collaborators to access a shared storage environment, avoiding the need for each user to download and manage datasets individually. This is efficient for teams with shared computational resources [1].

- Decentralized Collaboration: Researchers process data locally using a shared, containerized environment (like Neurodesk) and then combine the results. This model is ideal for complying with data privacy policies that prohibit centralizing raw data [1].

Step-by-Step Account and Data Management Protocol

Experimental Protocol 3: Sustained Repository Management

- Objective: To manage user accounts, control data access, and maintain shared datasets over time.

- Materials: Computer with internet access, repository login credentials.

- Procedure:

- Manage User Access and Permissions:

- For datasets with controlled access, you will act as a data steward.

- Use the repository's dashboard to review and approve/deny data access requests from other researchers.

- Ensure applicants have provided the necessary documentation, such as data use agreements (DUAs) or evidence of ethics training [2] [4].

- Handle Data Use Agreements (DUAs): Be familiar with the DUA required by your institution and the repository. For access-controlled data, you may need to ensure that potential users agree to the terms, which often prohibit attempts to re-identify participants and define acceptable uses [2].

- Track Dataset Impact: Use the analytics tools provided by the repository (e.g., view counts, download statistics) to monitor the reach and impact of your shared dataset.

- Version Control: If you need to update or correct your dataset after publication, follow the repository's protocol for creating a new version. This ensures the integrity of the original dataset while allowing for necessary updates. Tools like DataLad are particularly well-suited for version control of large datasets [1].

- Citation and Attribution: Ensure your dataset has a persistent digital object identifier (DOI). Cite this DOI in your publications and encourage others to do the same when using your data. This practice acknowledges your contribution and is a key incentive for data sharing [27].

- Manage User Access and Permissions:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Neuroimaging Data Sharing

| Tool / Resource | Category | Function in Data Sharing |

|---|---|---|

| BIDS Standard [1] [27] | Data Standardization | A community-driven standard for organizing and describing neuroimaging data, enabling interoperability and automated processing. |

| Neurodesk [1] | Containerized Environment | Provides a reproducible, portable analysis environment with a comprehensive suite of pre-installed neuroimaging tools, overcoming dependency issues. |

| DataLad [1] | Data Management | A version control system for data that manages distribution and storage, facilitating upload to and download from repositories like OpenNeuro. |

| fMRIPrep / QSMxT [1] | Processing Pipeline | BIDS-compatible, robust preprocessing pipelines that ensure consistent and reproducible data processing before analysis. |

| Open Brain Consent [1] | Ethical/Legal | Provides community-developed templates for consent forms and data user agreements tailored to comply with regulations like GDPR and HIPAA. |

| BIDS-validator | Validation Tool | A crucial quality-check tool that ensures a dataset is compliant with the BIDS specification before repository submission. |

| Python & R | Programming Languages | Essential for scripting data conversion (e.g., with heudiconv), analysis, and generating reproducible workflows. |

Leveraging Containerized Platforms like Neurodesk for Reproducible Analysis

Neurodesk is an open-source platform that addresses critical challenges in reproducible neuroimaging analysis by harnessing a comprehensive suite of software containers called Neurocontainers [28]. This containerized approach provides an isolated, consistent environment that encapsulates specific versions of neuroimaging software along with all necessary dependencies, effectively eliminating the variation in results across different computing environments that has long plagued neuroimaging research [29] [28]. The platform operates through multiple interfaces including a browser-accessible virtual desktop (Neurodesktop), command-line interface (Neurocommand), and computational notebook compatibility, making advanced neuroimaging analyses accessible to researchers across various technical backgrounds [30] [28].

The fundamental value proposition of Neurodesk lies in its ability to make reproducible analysis practical and achievable. By providing a consistent software environment that can be deployed across personal computers, high-performance computing (HPC) clusters, and cloud infrastructure, Neurodesk ensures that analyses produce identical results regardless of the underlying computing environment [31] [29]. This reproducibility is further enhanced through the platform's integration with data standardization frameworks like the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS), enabling seamless processing with BIDS-compatible tools such as fMRIPrep, QSMxT, and MRIQC [1].

Platform Architecture and Access Modalities

Core Architectural Components

Neurodesk's architecture centers around several interconnected components that work together to deliver a reproducible analysis environment. At its foundation are the Neurocontainers - software containers that package specific versions of neuroimaging tools with all their dependencies [28]. These containers are built using continuous integration systems based on recipes created with the open-source Neurodocker project, then distributed through a container registry [29]. The platform employs the CernVM File System (CVMFS) to create an accessibility layer that allows users to access terabytes of software without downloading or storing it locally, with only actively used portions of containers being transmitted over the network and cached on the user's local machine [29].

The Neurodesktop component provides a browser-accessible virtual desktop environment that can launch any containerized tool from an application menu, creating an experience that mimics working on a local computer [29] [28]. For advanced users and HPC environments, Neurocommand enables command-line interaction with Neurocontainers [29]. Additionally, the platform includes Neurodesk Play, a completely cloud-based solution that requires no local installation, making it ideal for teaching, demonstrations, and researchers with limited computational resources [31] [29].

Access Methods and Deployment Options

Table 1: Neurodesk Access Methods and Specifications

| Access Method | Target Users | Installation Requirements | Computing Resources | Use Case Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurodesktop (GUI) | Beginners, researchers preferring graphical interfaces | Container engine download (~1GB) | Local computer resources | Interactive data analysis, method development, educational workshops |

| Neurocommand (CLI) | Advanced users, HPC workflows | Container engine installation | HPC clusters, cloud computing | Large-scale batch processing, automated pipelines |

| Neurodesk Play (Cloud) | Anyone needing immediate access | None (browser-only) | Cloud resources | Teaching, demonstrations, initial evaluation, limited local resources |

Application Protocols for Reproducible Analysis

Protocol 1: Implementing a Reproducible VBM Analysis

Objective: To demonstrate a complete voxel-based morphometry (VBM) analysis using Neurodesk's containerized tools, ensuring identical results across computing environments.

Materials and Software:

- Structural MRI data in BIDS format

- Neurodesk platform with CAT12 container for VBM analysis

- BIDS validation tool (bids-validator)

- DataLad for data management (optional)

Methodology:

- Data Standardization: Convert raw DICOM images to BIDS format using tools available in Neurodesk (BIDScoin, dcm2niix, or heudiconv). Validate BIDS compliance using the integrated bids-validator [1].

- Container Selection: Launch the specific version of CAT12 used in the original study design through Neurodesk's application menu. Neurodesk maintains multiple versions of CAT12, allowing exact replication of previous analyses [1] [28].

- Analysis Configuration: Configure processing parameters within the CAT12 interface. These settings are automatically recorded for reproducibility.

- Execution: Run the VBM pipeline. The containerized environment ensures identical execution regardless of host operating system or computing environment [29] [28].

- Result Documentation: Use integrated tools to generate analysis reports and export processing logs. The complete environment can be shared alongside results.

Troubleshooting Notes: If encountering performance issues, consider switching from local execution to HPC or cloud deployment through Neurodesk's portable interface. For storage constraints, utilize the CVMFS layer to minimize local software footprint [29].

Protocol 2: Cross-Institutional Collaborative Analysis with Federated Data

Objective: To enable collaborative analysis across multiple institutions with differing data privacy policies using Neurodesk's decentralized model.

Materials and Software:

- Local datasets at each institution

- Neurodesk instances at each site

- Standardized analysis container shared between collaborators

- DataLad for sharing processed derivatives

Methodology:

- Container Development: Collaborators jointly develop an analysis pipeline using Neurodesk tools, then package it as a shared Neurocontainer [1].

- Local Execution: Each institution runs the shared container on their local data within their Neurodesk environment, avoiding the need to share raw data [1].

- Derivative Sharing: Processed data and results are shared using DataLad or similar tools integrated with Neurodesk [1].

- Result Integration: Combined analysis is performed on the shared derivatives to generate final project outcomes.

This approach is particularly valuable for studies involving data subject to privacy regulations (e.g., GDPR, HIPAA) where raw data cannot be shared between institutions [1].

Quantitative Platform Performance and Capacity

Table 2: Neurodesk Performance Metrics and Capabilities

| Metric Category | Specifications | Performance Notes | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Availability | 100+ neuroimaging applications [29] | Comprehensive coverage across neuroimaging modalities | Eliminates installation conflicts; multiple versions available simultaneously |

| Storage Efficiency | CVMFS access to TBs of software [29] | ~1GB initial download for Neurodesktop; on-demand caching | Dramatically reduces local storage requirements compared to traditional installations |

| Portability | Consistent environment across Windows, macOS, Linux [28] | Identical results across platforms [29] [28] | Addresses reproducibility challenges from OS-level variations |

| Deployment Flexibility | Local machines, HPC, cloud [30] [28] | Seamless transition between computing environments | Optimizes resource allocation without workflow modifications |

Visualization of Neurodesk Workflows

Reproducible Analysis Ecosystem

Figure 1: Neurodesk reproducible analysis workflow. The platform creates a consistent environment across different computing infrastructures, ensuring identical results regardless of where the analysis is executed.

Data Collaboration Models

Figure 2: Neurodesk collaboration models supporting varied data privacy requirements. The centralized model shares data through a cloud instance, while the decentralized model shares only analysis containers and result derivatives.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Neurodesk

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Function in Analysis Workflow | Implementation in Neurodesk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Conversion | dcm2niix, heudiconv, BIDScoin | Convert DICOM to BIDS format; standardize data organization | Pre-containerized tools with consistent execution across platforms [1] |

| Structural MRI | CAT12, FreeSurfer, FSL | Voxel-based morphometry, cortical thickness, tissue segmentation | Version-controlled containers ensuring measurement consistency [1] [28] |

| Functional MRI | fMRIPrep, SPM, FSL | Preprocessing, statistical analysis, connectivity | Reproducible preprocessing pipelines eliminating software version variability [1] |

| Diffusion MRI | MRtrix, FDT, DSI Studio | Tractography, connectivity mapping, microstructure | Containerized environments preventing library conflict issues [28] |

| Data Management | DataLad, Git | Version control, data distribution, sharing analysis pipelines | Integrated tools for managing both code and data throughout research lifecycle [1] |

| Quality Control | MRIQC | Automated quality assessment of structural and functional MRI | Standardized quality metrics across studies and sites [1] |

Implementation Case Studies

Case Study: Multi-site Dyslexia Research

The Dyslexia Data Consortium (DDC) exemplifies how containerized platforms enable large-scale collaborative research. The DDC repository addresses the challenge of integrating neuroimaging data from diverse sources by providing a specialized platform for sharing data from dyslexia studies [24]. When combined with Neurodesk's analytical capabilities, researchers can:

- Access standardized data through the DDC repository, which maintains all datasets in BIDS format [24]

- Execute harmonized analyses using Neurodesk containers, ensuring consistent processing across retrospective datasets [24]

- Overcome technical barriers through the web-based interface and containerized tools, making advanced analyses accessible to researchers with varying computational resources [24]

This approach is particularly valuable for dyslexia research where sufficient statistical power requires large, well-characterized participant groups accounting for age, language background, and cognitive profiles [24].

Case Study: Educational Workshop Implementation

Neurodesk significantly reduces the logistical overhead of organizing neuroimaging educational workshops. Traditional workshop setups require participants to individually download and configure each tool and its dependencies, consuming considerable time and storage space [1]. With Neurodesk:

- Participants access pre-configured environments through local installation or cloud instances

- Instructional consistency is maintained as all participants use identical software versions

- Technical troubleshooting is minimized allowing focus on conceptual understanding and practical application [1]

The containerized approach eliminates dependency management challenges and ensures all participants can replicate demonstrated analyses exactly [1].

Neurodesk represents a paradigm shift in neuroimaging analysis by making reproducible research practically achievable through its comprehensive containerized environment. By addressing the fundamental challenges of software installation, version conflicts, and cross-platform variability, the platform enables researchers to focus on scientific questions rather than technical infrastructure. The integration with data standardization frameworks like BIDS and support for multiple collaboration models further enhances its utility across diverse research scenarios.

Future developments in containerized platforms like Neurodesk will likely focus on scanner-integrated data processing, enhanced federated learning capabilities for privacy-preserving collaboration, and tightened integration with public data repositories [1]. As the neuroimaging field continues to evolve toward more open and collaborative science, containerized solutions provide the necessary foundation for ensuring that today's analyses remain reproducible and accessible tomorrow.

The evolution of neuroimaging data sharing platforms has transformed their role from simple archives to critical infrastructures that accelerate therapeutic development. These platforms address fundamental challenges in neurological and psychiatric drug development, where high failure rates often stem from poor target validation, inadequate dose selection, and heterogeneous patient populations. By providing standardized, large-scale datasets, platforms like Pennsieve, OpenNeuro, and the Dyslexia Data Consortium enable more robust assessment of target engagement, quantitative dose-response relationships, and biologically-defined patient stratification [22] [24]. This application note details specific protocols leveraging these resources across key drug development milestones, with structured tables and workflows to facilitate implementation by research teams.

Target Engagement: Verifying Mechanism of Action

Quantitative Framework for Target Engagement Assessment

Target engagement represents the foundational proof that a drug interacts with its intended biological target. Neuroimaging platforms provide multimodal data essential for correlating drug exposure with target modulation and downstream pharmacological effects across different spatial and temporal scales.

Table 1: Neuroimaging Biomarkers for Target Engagement Assessment

| Biological Target | Imaging Modality | Engagement Biomarker | Platforms with Relevant Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine D2/3 Receptors | PET with [11C]raclopride | Receptor occupancy (%) | EBRAINS, LONI IDA |

| Serotonin Transporters | PET with [11C]DASB | Binding potential reduction | Pennsieve, OpenNeuro |

| Amyloid Plaques | PET with [11C]PIB | Standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) | ADNI, Pennsieve |

| Synaptic Density | PET with [11C]UCB-J | SV2A binding levels | EBRAINS |

| Neural Circuit Activation | fMRI (BOLD signal) | Task-evoked activation change | OpenNeuro, brainlife.io |

| Functional Connectivity | resting-state fMRI | Network connectivity modulation | DABI, DANDI, Dyslexia Data Consortium |

Experimental Protocol: Establishing Target Engagement with fMRI

Objective: To demonstrate drug-induced modulation of target neural circuitry using task-based functional MRI.

Materials:

- Neuroimaging Platform: Pennsieve or OpenNeuro for accessing standardized task-fMRI paradigms [22] [25]

- Computational Environment: Neurodesk containerized analysis platform [25]

- Data Standardization: Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) validator [25]

- Processing Tools: fMRIPrep for standardized preprocessing [25]

- Statistical Analysis: FSL, SPM, or AFNI implemented in Jupyter Notebooks [24]

Methodology:

- Preclinical Rationale: Establish dose-dependent target modulation in animal models using orthogonal techniques (e.g., electrophysiology, microdialysis)

- Task Selection: Identify cognitive paradigms probing target neural circuits (e.g., fear extinction for amygdala engagement, working memory for prefrontal engagement)

- Imaging Parameters: Acquire BOLD fMRI at 3T or higher with standardized sequences; optimize for signal-to-noise in target regions

- Experimental Design: Implement randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover design with imaging at predicted Tmax

- Data Processing: Utilize fMRIPrep pipeline through Neurodesk for reproducible preprocessing [25]

- Statistical Modeling: Apply general linear models (GLM) with drug condition as factor, controlling for nuisance variables

- Dose-Response Modeling: Fit Emax models to relate plasma concentrations to neural response magnitudes

Interpretation: Significant dose-dependent modulation of target circuitry activity, coupled with appropriate plasma exposure, confirms engagement. This approach is particularly valuable for CNS targets where direct tissue sampling is impossible, including receptors, transporters, and intracellular signaling pathways.

Dose Selection: Optimizing Therapeutic Window

Model-Informed Paradigm for Dose Optimization

Traditional maximum tolerated dose (MTD) approaches often select inappropriately high doses for targeted therapies, increasing toxicity without added benefit [32]. Neuroimaging platforms enable model-informed drug development (MIDD) approaches that integrate exposure-response data from preclinical models and early-phase human studies.

Table 2: Model-Informed Dose Selection Framework

| Data Source | Data Type | Analysis Approach | Utility in Dose Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonclinical Data | Target occupancy EC50 | Population PK/PD modeling | Predict human doses for target engagement |

| Phase 1 Imaging | fMRI, PET, EEG | Exposure-response modeling | Quantify central pharmacodynamic effects |

| Early Clinical Data | Efficacy biomarkers | Logistic regression | Model probability of efficacy vs. dose |

| Safety Data | Adverse event incidence | Longitudinal modeling | Model probability of toxicity vs. dose |

| Integrated Analysis | All available data | Clinical utility index | Optimize benefit-risk across doses |

Experimental Protocol: Model-Informed Dose Optimization

Objective: To determine the optimal dose for Phase 3 trials by integrating neuroimaging biomarkers with pharmacokinetic and clinical data.

Materials:

- Data Integration Platform: Pennsieve for aggregating multimodal data [22]

- Modeling Software: R, Python, or specialized PK/PD platforms (e.g., NONMEM, Monolix)

- Computational Resources: High-performance computing clusters (e.g., Palmetto HPC) [24]

- Visualization Tools: Jupyter Notebooks with plotting libraries [24]

Methodology:

- Population PK Modeling: Characterize drug disposition and sources of variability using Phase 1 data

- Exposure-Imaging Response: Relate drug concentrations to target engagement biomarkers (e.g., receptor occupancy, circuit modulation)