Invasive vs. Non-Invasive Neural Interfaces: A 2025 Technical and Clinical Analysis for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of invasive and non-invasive neural interfaces, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Invasive vs. Non-Invasive Neural Interfaces: A 2025 Technical and Clinical Analysis for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of invasive and non-invasive neural interfaces, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles, from the biophysics of signal acquisition to the latest material and algorithmic innovations. The content details current methodologies and applications in clinical trials and therapeutic development, examines persistent technical challenges and optimization strategies, and offers a critical, evidence-based comparison of interface modalities. The goal is to equip scientific audiences with the insights needed to select appropriate technologies, navigate the development landscape, and contribute to the future of neurotechnology.

Core Principles and Neurotechnology Foundations: From Biophysics to Modern Systems

Neural interfaces, often termed brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) or brain-machine interfaces (BMIs), represent a revolutionary class of technologies that enable direct communication between the brain and external devices. These systems can translate neural activity into commands for controlling computers, prosthetic limbs, or other machines, bypassing traditional neuromuscular pathways [1] [2]. The fundamental value of these interfaces lies in their potential to restore function for individuals with disabilities—such as allowing paralyzed persons to control robotic arms or communicate through synthesized speech—and in their capacity to provide new tools for neuroscience research and therapeutic interventions [3] [4].

The field categorizes neural interfaces primarily by their level of invasiveness, which directly correlates with their signal quality, spatial resolution, and associated risks. Invasive interfaces are surgically implanted and directly interface with brain tissue, offering high-fidelity signals but carrying greater medical risks. Partially-invasive (or minimally-invasive) interfaces are located inside the skull but not within brain tissue, representing a middle ground. Non-invasive interfaces record from outside the skull, avoiding surgical risks entirely but obtaining lower-resolution signals [5] [6]. This spectrum of approaches enables researchers and clinicians to select appropriate technologies based on specific application requirements, balancing signal quality with safety considerations. The subsequent sections provide a detailed comparative analysis of these paradigms, supported by experimental data and methodological descriptions to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Neural Interface Technologies

Performance and Signal Characteristics

The performance characteristics of neural interfaces vary significantly across the invasiveness spectrum, influencing their suitability for different applications. The table below summarizes key quantitative metrics and attributes for the three primary paradigms.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Neural Interface Paradigms

| Parameter | Invasive Interfaces | Partially-Invasive Interfaces | Non-Invasive Interfaces |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Micrometer scale (single neurons) [6] | Millimeter scale (neural populations) [5] | Centimeter scale (broad regions) [6] |

| Temporal Resolution | Millisecond precision (kHz range) [6] | Millisecond precision [5] | Tens of milliseconds (100 Hz typical for dry EEG) [6] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | High [6] | Moderate to High [5] | Low to Moderate [5] [6] |

| Information Transfer Rate | High (e.g., speech decoding at 62 WPM) [1] | Moderate to High [5] | Low to Moderate (e.g., 20.9 WPM for sEMG handwriting) [7] |

| Key Signals Recorded | Action Potentials (APs), Local Field Potentials (LFPs) [6] | Electrocorticography (ECoG) [5] | EEG, MEG, fNIRS, sEMG [7] [5] |

| Primary Applications | Restoring motor function, speech decoding, complex device control [3] [4] | Motor restoration, epilepsy monitoring, research [5] | Basic device control, neurostimulation, research, wellness [7] [5] |

| Surgical Risk Profile | High (requires brain implantation) [4] | Moderate (requires craniotomy but not brain penetration) [5] | None [5] |

Signal Source and Technical Characteristics

Understanding the biological sources and technical aspects of the signals each interface type captures is crucial for appropriate selection in research and clinical settings.

Table 2: Signal Sources and Technical Specifications

| Interface Type | Biological Signal Sources | Recording Techniques | Penetration Depth | Typical Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive | Extracellular action potentials, local field potentials from cortical layers [6] | Utah arrays, intracortical electrodes, Neuropixels [5] [4] | Direct brain tissue contact [6] | Focal, limited to implant location [6] |

| Partially-Invasive | Cortical surface potentials, electrocorticography (ECoG) [5] | ECoG grids, WIMAGINE implant, Stentrode [5] | Brain surface (epidural or subdural) [5] | Regional, covers implanted grid area [5] |

| Non-Invasive | Post-synaptic currents (EEG), magnetic fields (MEG), hemodynamic responses (fNIRS), muscle potentials (sEMG) [7] [5] [6] | EEG caps, MEG systems, fNIRS headbands, sEMG wristbands [7] [5] | Superficial (through skull and scalp) [6] | Whole-brain or broad regions [6] |

Invasive interfaces provide access to the richest neural signals, including action potentials from individual neurons and local field potentials that reflect the integrated activity of local neuronal populations [6]. Partially-invasive techniques like ECoG capture signals from the cortical surface, offering a balance between signal quality and reduced invasiveness [5]. Non-invasive methods face the fundamental challenge of signal attenuation and spatial blurring as neural signals pass through the meninges, cerebrospinal fluid, skull, and scalp [6]. For instance, EEG primarily detects synchronized post-synaptic potentials from pyramidal neurons, but the skull acts as a strong low-pass filter, attenuating high-frequency components and reducing spatial resolution [6].

Recent advancements in non-invasive approaches include surface electromyography (sEMG) interfaces that decode neuromuscular signals at the wrist. One study demonstrated a generic non-invasive neuromotor interface using an sEMG wristband that achieved handwriting transcription at 20.9 words per minute and gesture decoding with greater than 90% accuracy across participants without person-specific training [7]. This represents a significant advancement in non-invasive interface performance, though still below the bandwidth of invasive systems capable of decoding speech at up to 62 words per minute [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Invasive Intracortical Recording

The following methodology outlines a standard approach for obtaining high-resolution neural signals using invasive intracortical interfaces, based on established practices in the field [5] [6]:

Surgical Implantation: Under sterile conditions and general anesthesia, perform a craniotomy to expose the dura mater over the target brain region. For motor control applications, the primary motor cortex is typically targeted. Implant multi-electrode arrays (such as Utah arrays or custom flexible arrays) using pneumatic insertion or controlled mechanical insertion to a depth of approximately 1-1.5mm to access cortical layers containing pyramidal neurons [6]. Secure the array to the skull using medical-grade titanium plates and cement.

Neural Signal Acquisition: Connect the implanted array to a percutaneous connector or wireless transmitter. For acute experiments, use wired connections to high-channel-count acquisition systems (e.g., Blackrock Neurotech systems). For chronic implants, utilize fully implanted wireless systems. Set sampling rates to 30 kHz per channel to adequately capture action potentials (300-5000 Hz band) and local field potentials (0.5-300 Hz band) [6]. Apply appropriate referencing schemes to minimize common-mode noise.

Signal Processing and Decoding: Implement a real-time processing pipeline beginning with bandpass filtering (300-5000 Hz for spikes, 0.5-300 Hz for LFPs). For spike detection, apply amplitude thresholding based on the root-mean-square of the signal. Perform spike sorting using principal component analysis or template matching algorithms to isolate single-unit activity [6]. Decode movement intentions using population vector algorithms or neural network models trained on the relationship between neural firing patterns and movement parameters [5] [6].

Closed-Loop Control Implementation: Establish a real-time control loop with update rates of 10-100 Hz. Map decoded movement intentions to prosthetic device commands using kinematic models. Provide visual feedback to users to facilitate neuroplasticity and improve control proficiency over time [6].

Protocol for Non-Invasive sEMG Interface

This protocol details the methodology for implementing a non-invasive surface electromyography (sEMG) interface for gesture decoding and computer control, based on recent research [7]:

Hardware Setup and Data Collection: Utilize a dry-electrode, multichannel sEMG wristband (sEMG-RD) with a high sample rate (2 kHz) and low-noise design (2.46 μVrms). Ensure proper sizing for participant wrist circumference with electrode spacing approaching the spatial bandwidth of EMG signals (5-10 mm) [7]. Position the electrode gap to align with the ulna bone where muscle density is reduced. Collect training data by prompting participants to perform specific gestures, wrist control tasks, and handwriting while recording sEMG activity and corresponding labels.

Signal Preprocessing and Time Alignment: Process raw sEMG signals using a real-time processing engine to reduce online-offline shift. Apply a time-alignment algorithm to precisely align prompter labels with actual gesture onset times, accounting for participant reaction time and compliance variations [7]. Filter signals to remove motion artifacts and power line interference.

Model Training and Validation: Train neural network models on data collected from a diverse participant population (hundreds to thousands of participants). Use the collected sEMG data as input and the aligned behavioral labels as supervision. Implement data augmentation techniques to improve model robustness across anatomical variations and sensor placements [7]. Validate model performance on held-out participants to assess cross-user generalization.

Closed-Loop Performance Evaluation: Evaluate the system in closed-loop tasks including continuous navigation (measuring target acquisitions per second), discrete gesture detection (gesture detections per second), and handwriting transcription (words per minute) [7]. For handwriting, prompt participants to hold their fingers together as if holding a writing implement and "write" prompted text while the system decodes the sEMG signals into text.

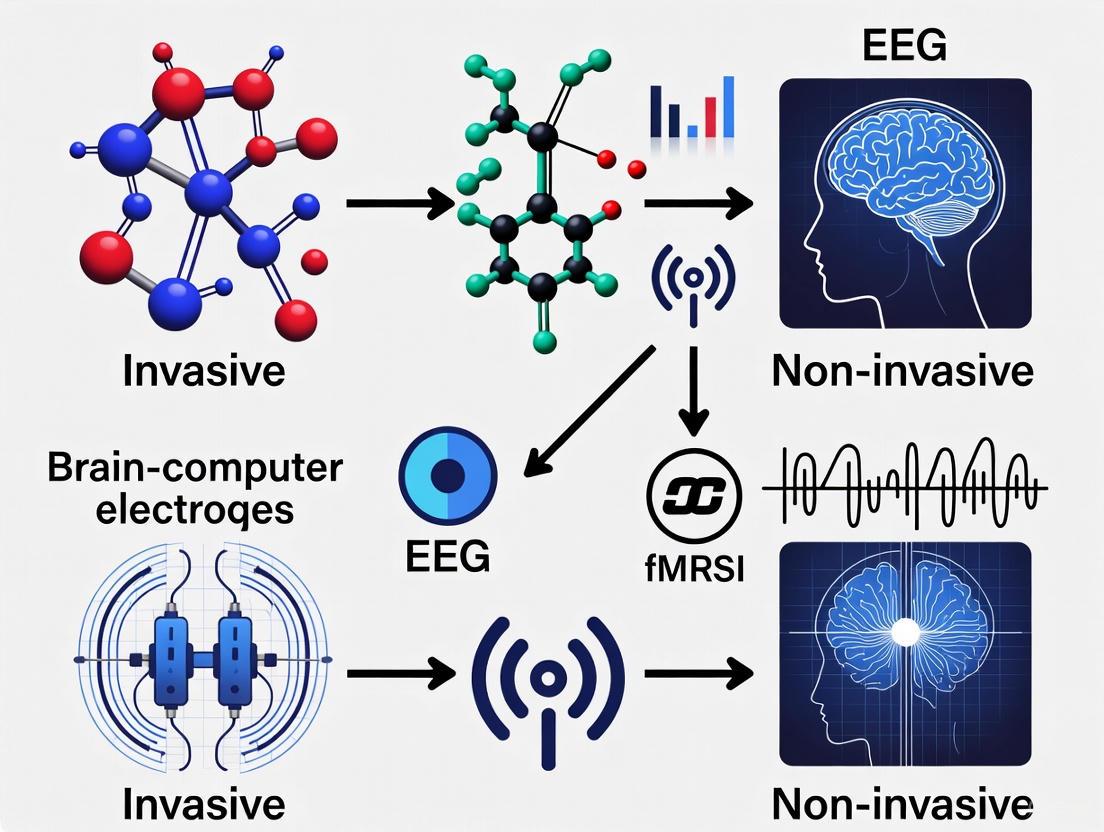

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate key experimental workflows and signal pathways for different neural interface paradigms.

Diagram 1: Invasive interface workflow with closed-loop feedback

Diagram 2: Non-invasive sEMG interface workflow for computer control

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details essential materials, reagents, and tools used in neural interface research, providing investigators with a practical resource for experimental planning.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Neural Interface Development

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Research Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode Materials | Platinum-iridium alloys, Graphene, Conductive polymers [3] | Neural signal transduction with biocompatibility | Chronic implants, ECoG grids, stent electrodes [3] [5] |

| Signal Acquisition Systems | Blackrock Neurotech systems, OpenBCI, Ripple Neuro systems [8] [9] | Multi-channel neural data acquisition with precise temporal resolution | Preclinical research, human clinical trials [5] [9] |

| Decoding Algorithms | Spike sorting algorithms, Deep learning networks (CNN, RNN), Transfer learning methods [5] | Translating neural signals to intended commands | Real-time prosthetic control, speech decoding [5] [1] |

| Surgical Implantation Tools | Stereotactic frames, Pneumatic inserters, MRI/CT guidance systems [3] | Precise electrode placement with minimal tissue damage | Utah array implantation, depth electrode placement [3] [6] |

| Calibration & Testing Protocols | Behavioral prompting systems, Time-alignment algorithms, Cross-validation methods [7] | System performance evaluation and optimization | Gesture decoding validation, handwriting recognition tests [7] |

The selection of appropriate materials and tools significantly impacts neural interface performance and longevity. For invasive interfaces, electrode materials must balance electrical properties with biocompatibility to minimize immune response and signal degradation over time [3]. Platinum-iridium alloys offer excellent corrosion resistance, while graphene and conductive polymers provide flexibility that reduces mechanical mismatch with neural tissue [3]. For signal acquisition, commercial systems like those from Blackrock Neurotech support high-channel-count recordings essential for decoding complex intentions from neural populations [9].

In decoding algorithms, recent advances in deep learning have improved the performance of both invasive and non-invasive systems. Convolutional neural networks can extract spatial patterns from multi-electrode arrays, while recurrent neural networks model temporal dependencies in neural signals [5]. Transfer learning techniques are particularly valuable for non-invasive systems, enabling models trained on large participant populations to generalize to new users with minimal calibration [7] [5]. For non-invasive sEMG interfaces, the development of time-alignment algorithms has been crucial for precisely matching prompts with actual muscle activity during training data collection [7].

The neural interface spectrum encompasses technologies with complementary strengths tailored to different applications. Invasive systems provide unparalleled signal resolution for restoring complex functions like movement and communication in severe paralysis, while partially-invasive approaches offer a favorable risk-benefit profile for specific clinical applications. Non-invasive interfaces present the safest option for basic control applications, wellness monitoring, and research involving healthy participants.

Future progress will likely focus on improving the performance and accessibility of all interface types. For invasive approaches, developments in biocompatible materials and wireless technology may reduce risks and extend functional lifespan [3] [4]. Partially-invasive techniques like the Stentrode and high-density ECoG continue to narrow the performance gap with fully invasive approaches [5]. Non-invasive methods are benefiting from advanced signal processing and large-scale data collection to improve cross-user generalization [7]. Additionally, optical neural interfaces represent an emerging alternative that may offer high spatial resolution with decreased invasiveness, though this technology remains primarily in preclinical development [10].

The optimal neural interface paradigm depends critically on the specific application requirements and risk-benefit considerations. This comparison provides researchers and clinicians with evidence-based guidance for selecting appropriate technologies and methodologies to advance both fundamental neuroscience and clinical applications.

The field of neural interfaces research is fundamentally divided by the biophysical properties of the signals that these tools acquire. Understanding the origin, characteristics, and limitations of electrophysiological and hemodynamic signals is crucial for selecting the appropriate technology for specific scientific or clinical applications, from basic neuroscience to drug development. This guide provides a structured comparison of four core signal acquisition modalities—EEG, ECoG, intracortical, and fNIRS—framed within the critical context of the invasive versus non-invasive trade-off. We dissect their underlying biophysical principles, summarize their performance metrics in comparative tables, and detail experimental protocols that leverage their complementary strengths.

Biophysical Origins and Signal Characteristics

Neural signals can be broadly categorized into those measuring electrical activity directly and those measuring the metabolic consequences of that activity.

Electrophysiological Signals (EEG, ECoG, Intracortical)

Electrophysiological signals originate from the transient flow of ions across neuronal membranes. Action Potentials are all-or-nothing, millisecond-duration signals that propagate along a neuron's axon, representing the primary unit of neuronal communication [11]. Field Potentials, in contrast, are slower, graded signals resulting from the summation of postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs and IPSPs) from thousands to millions of synchronously active neurons [11] [12]. The spatial scale of recording determines the signal type accessible to a given modality.

- Intracortical Signals: Recorded via microelectrodes implanted directly into the brain tissue, these signals provide the highest resolution. They can capture single-unit activity (SUA), representing action potentials from individual neurons, and multi-unit activity (MUA), alongside local field potentials (LFPs), which are low-frequency components (<300 Hz) reflecting summed synaptic activity [11] [13].

- ECoG Signals: Electrocorticography (ECoG) electrodes are placed on the surface of the brain, beneath the skull. They primarily capture LFPs from a larger population of neurons than intracortical electrodes, with a spatial resolution of 1-10 mm [13]. ECoG offers a balance, providing signals with higher spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio than non-invasive methods but without penetrating the brain tissue [5].

- EEG Signals: Electroencephalography (EEG) is recorded from electrodes on the scalp. The electrical signals generated by cortical pyramidal neurons must propagate through the meninges, skull, and scalp, which act as resistive and capacitive layers that severely blur the signal. Consequently, EEG reflects the synchronized activity of millions of neurons, providing excellent temporal resolution (milliseconds) but poor spatial resolution (several centimeters) [12].

The following diagram illustrates the pathway of electrical signal generation and acquisition for these modalities.

Diagram 1: Pathway from neuronal activity to acquired electrophysiological signals.

Hemodynamic Signals (fNIRS)

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) measures an indirect correlate of neural activity based on neurovascular coupling—the mechanism by which neural activity triggers a localized hemodynamic response [14] [12]. When a brain region becomes active, it consumes oxygen, leading to a complex cascade that increases cerebral blood flow to deliver oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO). fNIRS uses near-infrared light (600-1000 nm) shined through the scalp to measure concentration changes of HbO and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) in the cortical capillaries [14] [12]. This hemodynamic response is slower than electrical signals, unfolding over seconds, which limits fNIRS's temporal resolution but provides good spatial resolution for a non-invasive technique.

Comparative Performance Data

The biophysical origins of these signals directly translate into their performance characteristics, as summarized in the tables below.

Table 1: Technical specifications and performance metrics of neural signal acquisition modalities.

| Metric | EEG | ECoG | Intracortical | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | ~1-3 cm [12] | 1-10 mm [13] | 50-500 μm [11] [13] | ~1-2 cm [15] |

| Temporal Resolution | ~1-100 ms [12] | ~1-10 ms [5] | <1 ms [11] | ~0.1-1 s [15] [12] |

| Invasiveness | Non-invasive | Invasive (subdural) | Invasive (intraparenchymal) | Non-invasive |

| Primary Signal | Scalp potentials | Cortical surface potentials | Action potentials & LFPs | HbO/HbR concentration |

| Signal Origin | Summed postsynaptic potentials [12] | Summed postsynaptic potentials | Single-unit & multi-unit activity [11] | Hemodynamic response [14] |

| Typical Bandwidth | 0.1-100 Hz [16] | 0-500 Hz [13] | 0.1-7,000 Hz (SUA: 300-7,000 Hz) [13] | ~0.01-0.3 Hz [14] |

Table 2: Suitability for applications and practical considerations in research and clinical settings.

| Consideration | EEG | ECoG | Intracortical | fNIRS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key Clinical Applications | Epilepsy monitoring, sleep disorders, brain injury [16] [9] | Epilepsy focus mapping, surgical planning [17] | Motor prosthetics for paralysis [5] [17] | Cognitive neuroscience, neurodevelopment [14] |

| Key Research Applications | Cognitive neuroscience, brain-state monitoring [12] | Motor control BCIs, basic communication [13] | Fine motor control, complex language decoding [13] | Neurovascular coupling, bedside monitoring [18] |

| Signal Stability | Moderate (prone to artifacts) | High | Degrades over time (glial scarring) [13] | High |

| Relative Cost | Low | High | Very High | Moderate [12] |

| Portability | High (wearable systems) | Low | Very Low | High [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Multimodal Integration

No single modality provides a complete picture of brain function. The following protocols illustrate how combining these tools can yield synergistic insights.

Protocol: Investigating Cognitive Load in Dynamic Environments

This protocol, adapted from a Frontiers study, uses a dual-task paradigm to study cognitive load and stress [14].

- Objective: To investigate the effects of complex, dynamically changing environments on cognitive load, affective state, and performance.

- Subjects: 30 healthy human participants.

- Task: Participants play three versions of Tetris (Easy constant, Hard constant, Ramp difficulty) while simultaneously performing an Auditory Reaction Task (ART) [14].

- Signal Acquisition:

- fNIRS: Measures HbO and HbR concentration changes in the prefrontal cortex to index cognitive load via hemodynamic response [14].

- EEG: Recorded from scalp electrodes to track mental fatigue through power band shifts (e.g., increased Delta power) and provide millisecond-resolution brain dynamics [14].

- ECG/EDA: Recorded to assess physiological stress response.

- Performance Metrics: Tetris score and ART reaction time/accuracy.

- Subjective Reports: Self-reports of valence, enjoyment, and perceived workload.

- Analysis:

- fNIRS: General linear model analysis to compare HbO/HbR changes between task conditions.

- EEG: Time-frequency analysis to quantify band power changes (Delta, Theta, Alpha, Beta).

- Correlation: Perform multimodal correlation between fNIRS activation, EEG spectral features, and performance metrics.

This protocol leverages fNIRS's spatial localization of cortical load and EEG's sensitivity to rapid state changes like fatigue, providing a comprehensive assessment unavailable to either modality alone [14].

Protocol: Concurrent fNIRS-EEG for Motor Imagery BCI

This protocol outlines a standard pipeline for developing a more robust Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) [12] [18].

- Objective: To improve the classification accuracy of motor imagery (e.g., imagining hand movement) for BCI control by integrating electrical and hemodynamic data.

- Signal Acquisition:

- A custom-built helmet or cap with co-registered EEG electrodes and fNIRS optodes over the motor cortex [18].

- EEG is recorded continuously.

- fNIRS records changes in HbO and HbR from channels covering the same cortical area.

- Experimental Paradigm:

- A cue-based block design where participants perform cued motor imagery (e.g., left hand vs. right hand) interspersed with rest periods.

- Data Processing & Fusion:

- Preprocessing: Independent Component Analysis (ICA) for EEG artifact removal [16] and Modified Beer-Lambert Law for fNIRS to convert light intensity to HbO/HbR concentration [12].

- Feature Extraction:

- EEG: Extract event-related desynchronization/synchronization (ERD/ERS) in the Mu (8-12 Hz) and Beta (13-30 Hz) rhythms.

- fNIRS: Extract the mean HbO concentration during the task blocks.

- Data Fusion: A common approach is feature-level fusion, where the extracted EEG and fNIRS features are concatenated into a single feature vector for classification [12].

- Classification: The fused feature vector is fed into a classifier (e.g., Support Vector Machine - SVM or Linear Discriminant Analysis - LDA) to discriminate between the different motor imagery tasks.

The fusion of EEG's rapid onset and fNIRS's spatially specific response has been shown to improve classification accuracy and reduce BCI calibration time compared to unimodal systems [12] [18].

The following workflow diagram visualizes the stages of this multimodal experimental protocol.

Diagram 2: Workflow for a concurrent fNIRS-EEG Brain-Computer Interface experiment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key materials and equipment for setting up experiments with the featured modalities.

| Item | Function/Description | Exemplary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Integrated fNIRS-EEG Cap | A flexible cap with co-registered EEG electrodes and fNIRS optode holders for simultaneous data acquisition [18]. | Concurrent fNIRS-EEG studies (Section 4.2). |

| 3D-Printed Custom Helmet | A rigid, subject-specific helmet for precise and stable positioning of EEG and fNIRS components, improving data quality [18]. | Studies requiring high spatial accuracy and minimal motion artifact. |

| ECoG Grid (e.g., WIMAGINE) | An implantable ECoG grid system designed for chronic, stable recording from the cortical surface [5]. | Long-term BCI studies for restoring motor function. |

| Intracortical Array (e.g., Utah Array) | A microelectrode array implanted into the brain tissue to record single- and multi-unit activity [5]. | High-precision motor control studies for advanced neuroprosthetics. |

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) | A computational algorithm for separating artifacts (e.g., eye blinks, muscle activity) from neural signals in EEG data [16]. | Standard preprocessing step for EEG analysis. |

| Modified Beer-Lambert Law (MBLL) | The fundamental algorithm used in fNIRS to convert measured light attenuation into changes in HbO and HbR concentration [12]. | Essential for all fNIRS data analysis. |

The evolution of Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) hinges on overcoming fundamental engineering and biological constraints embodied by three critical performance benchmarks: spatial resolution, temporal resolution, and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). These parameters form a delicate triage that defines a neural interface's capability to accurately interpret brain activity, and they are directly influenced by the choice between invasive and non-invasive approaches. Spatial resolution refers to the smallest distinguishable distance between two neural activity sources, determining whether an interface can differentiate individual neuron firing or broader regional activation. Temporal resolution represents the smallest measurable time interval between neural events, dictating how precisely an interface can track the rapid dynamics of brain signaling. Signal-to-noise ratio quantifies the strength of relevant neural signals against background interference, ultimately determining decoding accuracy and reliability [19] [20].

The central thesis in BCI research posits that invasiveness level dictates performance characteristics across these three benchmarks. Invasive interfaces, by physically penetrating the skull and often contacting neural tissue directly, achieve superior performance across all three parameters but introduce surgical risks, potential for tissue response, and long-term stability challenges. Non-invasive interfaces, operating outside the skull, offer greater safety and accessibility but face fundamental physical limitations in signal acquisition that constrain their ultimate performance ceiling [8] [17] [1]. This comparison guide provides an objective analysis of how current neural interface technologies perform across these key benchmarks, supported by experimental data and methodological details to inform research and development decisions.

Performance Benchmark Comparison of Neural Interface Technologies

The table below provides a quantitative comparison of key performance characteristics across major neural interface technologies, highlighting the clear trade-offs between invasive and non-invasive approaches.

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Neural Interface Technologies

| Technology | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intracortical Electrodes | Single neuron (~0.05 mm) [21] | Excellent (<1 ms) [21] | Very High (direct neural contact) [1] | Motor prosthetics, speech decoding [22] [1] |

| ECoG | Mesoscale (1-10 mm) [8] | Excellent (<1 ms) [8] | High (subdural placement) [8] | Epilepsy monitoring, motor BCIs [17] |

| EEG | Low (10-20 mm) [8] [1] | Good (~10-100 ms) [17] | Low (signal attenuation through skull) [1] [7] | Brain monitoring, basic BCIs, research [8] [17] |

| fNIRS | Low (10-20 mm) [8] | Poor (seconds) [8] | Low (hemodynamic response lag) [8] | Brain monitoring, neurofeedback [8] [17] |

| fMRI | High (1-3 mm) [23] [20] | Poor (1-3 seconds) [23] | Variable (BOLD sensitivity) [23] [20] | Research, surgical planning [23] |

| sEMG | Muscle group level [7] | Excellent (<1 ms) [7] | High (amplified neural signals in muscle) [7] | Neuromotor interfaces, prosthesis control [7] |

Table 2: Market Forecast and Application Focus (2025-2045) [8]

| Segment | Forecasted CAGR | Primary Drivers | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Invasive (Medical) | 8.4% (overall market) | Assistive technology, neurological disorder management | Signal quality, spatial resolution limitations |

| Non-Invasive (Consumer) | 8.4% (overall market) | AR/VR headsets, wellness monitoring | Performance vs. accessibility trade-offs |

| Invasive (Assistive) | 8.4% (overall market) | Severe paralysis, communication restoration | Surgical risks, long-term stability, biocompatibility |

| Invasive (Research) | 8.4% (overall market) | Neuroscience understanding, algorithm development | Regulatory hurdles, tissue response |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Deep Neural Network Decoding for Intracortical Interfaces

Objective: To develop a BCI decoding framework that maintains high accuracy without daily recalibration, addressing stability challenges in invasive interfaces [22].

Methodology:

- Participant: 27-year-old male with C5 AIS A tetraplegia implanted with a 96-channel microelectrode array in the hand and arm area of left primary motor cortex [22].

- Task Design: Participant performed a four-movement imagination task (index extension, index flexion, wrist extension, wrist flexion) in response to visual cues across 80 sessions over 865 days [22].

- Neural Features: Mean wavelet power (MWP) values calculated from raw voltage for each of the 96 channels over 100-ms bins [22].

- Decoder Architecture: Deep neural network (NN) with three configurations:

- Fixed NN (fNN): Initial model calibrated using 40 sessions without updating

- Supervised NN (sNN): Updated daily with explicit training labels

- Unsupervised NN (uNN): Updated daily without explicit labels using inferred movement timing [22]

- Comparison Models: Support vector machine (SVM), linear discriminant analysis (LDA), and naive Bayes decoders retrained daily [22].

Key Results: The supervised NN (sNN) demonstrated significantly higher accuracy than daily-retrained SVM (mean difference 6.35±2.47%, p=3.69×10⁻⁸), with 37/40 sessions achieving >90% accuracy. The unsupervised NN (uNN) maintained performance for over a year without supervised recalibration, outperforming the daily-retrained SVM by 6.12±2.68% [22].

High-Resolution fMRI for BCI Applications

Objective: To investigate the effects of spatial and temporal resolution on fMRI sensitivity and its implications for fMRI-based BCIs [23].

Methodology:

- Imaging Parameters: 7T fMRI during ankle-tapping task across range of spatial (1.5×1.5×1.5mm³ to standard resolutions) and temporal resolutions (500ms to standard TR) [23].

- Metrics: Temporal signal-to-noise ratio (tSNR), observed percent signal change (%∆S), volumes of significant activation, Z-scores, and decoding performance of linear classifiers [23].

- Analysis: Compared BOLD sensitivity measures across resolution combinations to determine optimal parameters for functional network imaging [23].

Key Results: At highest spatial resolution (1.5×1.5×1.5mm³), increasing temporal resolution yielded 22% increase in %∆S (p=0.006) and 9% improvement in decoding performance (p=0.015) despite 29% decrease in tSNR (p<0.001). This demonstrates BOLD sensitivity can be significantly improved with temporal resolution when spatial resolution is sufficiently high [23].

Non-Invasive Surface EMG Neuromotor Interface

Objective: To develop a generic non-invasive neuromotor interface with high performance and cross-user generalization [7].

Methodology:

- Platform: Dry-electrode, multichannel sEMG wristband with high sample rate (2 kHz) and low noise (2.46 μVrms), manufactured in four sizes for anatomical variation [7].

- Participants: 162-6,627 participants across tasks (wrist control, discrete-gesture detection, handwriting) for training generic models [7].

- Data Collection: Supervised training with sEMG activity and prompt timestamps, with post-hoc time-alignment algorithm to account for reaction time variations [7].

- Tasks: Continuous navigation (wrist control), discrete gesture detection (9 distinct gestures), and handwriting (20.9 words per minute) [7].

Key Results: The generic sEMG decoding models achieved cross-user generalization with 0.66 target acquisitions per second in continuous navigation, 0.88 gesture detections per second in discrete tasks, and handwriting at 20.9 words per minute without person-specific training [7].

Technical Foundations: Resolution and SNR Relationships

Spatial Resolution Fundamentals

In MRI and related imaging modalities, spatial resolution is determined by the relationship between k-space coverage and image properties. The nominal spatial resolution (Δx, Δy) is inversely related to the overall extent of k-space coverage (Wx, Wy):

Δx = 1/Wx, Δy = 1/Wy [19]

Where k-space represents the spatial frequency domain of the image, with the central region containing low spatial frequency information (overall contrast) and peripheral regions containing high spatial frequency information (fine details and edges) [19] [24]. The fundamental limitation emerges from k-space truncation, where finite sampling necessarily loses high spatial frequency information, leading to Gibbs ringing artifacts and reduced image sharpness [19] [24]. This physical constraint manifests differently across BCI modalities: invasive interfaces minimize truncation effects by closer proximity to neural sources, while non-invasive approaches suffer from inherent spatial low-pass filtering by biological tissues [8] [1].

Temporal Resolution and SNR Trade-Offs

The relationship between temporal resolution, spatial resolution, and SNR presents a fundamental challenge across neural interface technologies. In fMRI, increasing temporal resolution (shorter TR) typically decreases tSNR due to T1-relaxation effects, while increasing spatial resolution decreases net magnetization per voxel [23]. However, research demonstrates that at sufficiently high spatial resolution, increasing temporal resolution can improve overall BOLD sensitivity despite tSNR reductions, indicating complex interactions between these parameters [23].

In electrophysiological methods including EEG and intracortical recording, temporal resolution is generally superior but faces different SNR challenges. The table below summarizes key relationships and optimization strategies across interface types.

Table 3: Resolution and SNR Optimization Strategies

| Technology | Primary SNR Limitations | Optimization Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Intracortical Electrodes | Tissue response, glial scarring, electrode degradation [21] [1] | Flexible substrates, biocompatible materials, adaptive algorithms [8] [22] |

| EEG | Skull attenuation, distance from sources, environmental noise [8] [1] | Dry electrodes, sensor arrays, advanced signal processing, reference schemes [8] |

| fMRI | Physiological noise, thermal noise, BOLD sensitivity [23] [20] | Higher field strengths, array coils, parallel imaging, optimized sequences [23] |

| sEMG | Electrode-skin interface, motion artifacts, cross-talk [7] | High-density arrays, anatomical conformity, adaptive fitting [7] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Neural Interface Development

| Item | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Microelectrode Arrays | Record action potentials from neuronal populations | Intracortical BCIs, motor decoding studies [21] [22] |

| Dry Electrodes | Enable convenient EEG acquisition without conductive gel | Consumer neurotechnology, wearable BCIs [8] |

| fNIRS Systems | Measure blood oxygenation changes using near-infrared light | Brain monitoring, neurofeedback training [8] [17] |

| High-Density sEMG Arrays | Record myoelectric potentials from multiple muscle regions | Neuromotor interfaces, gesture decoding [7] |

| Deep Neural Network Frameworks | Decode neural signals with high accuracy and adaptability | Motor intention decoding, speech reconstruction [22] |

| Biocompatible Substrates | Improve long-term stability of implanted interfaces | Chronic neural implants, reducing tissue response [8] [1] |

| Quantum Sensors | Enable wearable MEG with improved sensitivity | Next-generation non-invasive BCIs [8] |

The future of neural interface technology lies in breaking the current resolution-SNR-invasiveness trade-offs through multidisciplinary innovation. Promising directions include the development of miniaturized, biocompatible invasive interfaces that reduce tissue response while maintaining high signal quality, and next-generation non-invasive technologies like quantum-enabled sensors (OPM-MEG) that approach invasive-level performance without surgical risks [8] [1]. Advanced decoding algorithms, particularly deep learning approaches that can extract more information from limited signals, will further bridge the performance gap between modalities [22] [7].

The clinical translation pathway will likely see invasive interfaces addressing severe neurological conditions where benefits justify surgical risks, while non-invasive technologies expand into broader consumer and therapeutic applications [8] [17] [1]. As both trajectories advance, the fundamental benchmarks of spatial resolution, temporal resolution, and signal-to-noise ratio will remain the critical metrics driving progress in this rapidly evolving field.

For over two decades, the Utah Array has served as the gold standard for invasive cortical recording and stimulation, underpinning critical advances in brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) and neuroscience research [25] [26]. With its high-channel count and superior signal-to-noise ratio, it has empowered researchers to perform intricate studies of neural networks at an unprecedented level of detail [25]. However, the relentless pursuit of understanding the brain's complex circuitry has fueled a strong drive toward developing modern high-channel-count neuroelectronic interfaces [27]. This evolution is marked by a transition from passive electrode arrays to systems incorporating novel materials and active transduction mechanisms, enabling recordings from thousands of channels simultaneously [27]. This guide objectively compares the performance of the established Utah Array against the capabilities of emerging high-density systems, framing the discussion within the broader scientific debate on invasive versus non-invasive neural interfaces.

Performance Comparison: Utah Array vs. Modern High-Channel-Count Systems

The following tables summarize key quantitative metrics and functional characteristics, providing a direct comparison between the traditional Utah Array and modern high-channel-count technologies.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance and Physical Specifications

| Parameter | Utah Array | Modern High-Channel-Count Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Channel Count (per device) | 96 - 128 electrodes per array; up to 1024 channels per system [25] [26] | Thousands of channels [27] |

| Electrode Pitch | 400 µm [25] | Significantly reduced (enabled by novel materials and active electronics) [27] |

| Standard Electrode Lengths | 0.5 - 1.5 mm (Research); 1.0 - 1.5 mm (Clinical) [25] | Customizable for specific targets |

| Impedance Range | Platinum: 20-800 kΩ; SIROF/IrOx: 1-80 kΩ [25] | Optimized for high-density, addressable arrays [27] |

| Typical Recorded Signals | Action Potentials (spikes), Local Field Potentials (LFPs) [25] [6] | Action Potentials, Local Field Potentials, with higher spatial resolution [27] |

| Long-Term Human Implantation | Over 8 years and counting (documented) [28] [26] | Primarily in research and development stages [27] |

Table 2: Functional Characteristics and Applications

| Characteristic | Utah Array | Modern High-Channel-Count Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Key Advantage | Longevity and Safety: Extensive safety profile with decades of human use; FDA-cleared for short-term monitoring [26] | Spatio-temporal Resolution: High-density design allows for recording from vast neuronal populations [27] |

| Primary Limitation | Channel Count Cap: Practical limit for chronic stability in humans; higher counts risk tissue damage [26] | Clinical Translation: Long-term stability and biocompatibility in humans still under investigation [27] |

| Material Failure Mode | Metal corrosion (Pt, IrOx); insulation cracking/delamination of Parylene-C [28] | Under evaluation; focus on novel, robust biomaterials [27] |

| Biological Failure Mode | Meningeal encapsulation; glial sheath formation; neuronal loss [28] | Tissue reaction to higher density implants is a critical research area [27] |

| Ideal Application | Chronic human BCI for neuroprosthetics, communication [25] [26] [29] | Fundamental neuroscience research, high-fidelity sensory mapping [27] |

The Invasive vs. Non-Invasive Neural Interface Context

The evolution toward higher channel counts in invasive interfaces must be understood within the broader dichotomy of invasive versus non-invasive BMI strategies. Invasive BCIs, like the Utah Array and its successors, record signals directly from the cortical surface or within the brain tissue, capturing signals such as action potentials and local field potentials (LFPs) with high spatial and temporal resolution [6] [30]. In contrast, non-invasive techniques, such as electroencephalography (EEG), record from the scalp and are limited to measuring aggregated, low-frequency neuronal activity that has been attenuated by the skull and scalp [6].

Table 3: Invasive vs. Non-Invasive Signal Characteristics

| Feature | Invasive (e.g., Utah Array & Modern Systems) | Non-Invasive (e.g., EEG) |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | High (microns to millimeters) [30] | Low (centimeters) [6] |

| Temporal Resolution | High (capable of detecting single-neuron spikes) [30] | Lower (skull acts as a low-pass filter) [6] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | High, robust against artifacts [30] | Lower, susceptible to noise [6] |

| Signal Source | Input, local processing, and output of cortical areas [6] | Primarily post-synaptic currents from pyramidal neurons [6] |

| Information Transfer Rate | Inherently higher [6] | Lower [6] |

| Clinical Risk | Requires surgery; higher initial risk [30] | Risk-free [6] |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental anatomical and signal resolution relationships that define this technological landscape.

Anatomical and Signal Relationship of Neural Interfaces

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Neural Interface Performance

Evaluating the performance and longevity of invasive microelectrode arrays involves standardized experimental protocols, both in preclinical and clinical settings. The methodologies below are critical for generating the comparative data presented in this guide.

Chronic Electrophysiological Recording in Human BCI Trials

Objective: To assess the long-term stability and quality of neural signal recording from implanted arrays in human participants for brain-computer interface control [28].

Methodology:

- Implantation: Utah Arrays are surgically implanted into the target brain region (e.g., motor cortex) under an Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) from the FDA and with local IRB approval [28].

- Signal Acquisition: Neural data (action potentials and LFPs) are recorded daily or weekly using a dedicated neural signal processing system (e.g., from Blackrock Neurotech). The system amplifies, filters, and digitizes the signals from each electrode [25].

- Performance Metrics:

- Signal Amplitude: The peak-to-peak voltage of recorded action potentials is tracked over time. An initial increase is often observed post-implantation, followed by a gradual decline in the following months and years [28].

- Impedance Measurement: Electrode impedance is monitored regularly, as it can indicate tissue encapsulation or material degradation [28].

- BCI Control Tasks: Participants perform tasks such as controlling a cursor on a screen or a robotic arm. Decoding algorithms (e.g., Kalman filters, population vector algorithms) translate neural activity into control commands. Performance is measured by metrics like success rate, information transfer rate, and task completion time [30].

- Data Analysis: Recording quality is correlated with the duration of implantation and post-explant findings related to tissue reaction and material integrity [28].

Post-Explant Material and Histological Analysis

Objective: To characterize the material degradation of explanted electrode arrays and the biological tissue response, and to correlate these findings with recorded electrophysiological performance [28].

Methodology:

- Explantation: Arrays are surgically removed from human or animal subjects after a predetermined implantation period.

- Tissue Encapsulation Analysis:

- Optical Microscopy: Provides an initial assessment of the extent of fibrous tissue growth on the array substrate and around electrode shanks [28].

- Two-Photon Microscopy (TPM): Allows for high-resolution, three-dimensional imaging of the tissue sheath surrounding individual electrodes, revealing its thickness and density [28].

- Material Degradation Analysis:

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): Used to examine the physical integrity of electrode tips and insulation at high magnification, revealing cracks, delamination, or corrosion [28].

- Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS): Performed in conjunction with SEM to determine the elemental composition of electrode materials, identifying loss of conductive coating (e.g., iridium from IrOx tips) or contamination [28].

- Correlation with Performance: Findings from explant analysis are directly compared with the chronic recording data from the same array to identify factors influencing signal decline [28].

The workflow for this comprehensive analysis is depicted below.

Post-Explant Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

This table details essential materials and solutions used in experiments featuring the Utah Array and high-channel-count systems, which are crucial for replicating studies and understanding the underlying technology.

Table 4: Essential Research Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Utah Electrode Array (UEA) | A 10x10 grid of silicon microelectrodes; the gold-standard device for chronic cortical recording and stimulation [25] [26]. | Fundamental platform for intracortical BCI research in humans and animal models [25] [29]. |

| Platinum (Pt) Electrode Tips | A stable, biocompatible metal for recording; standard option for the UEA with higher impedance [25] [28]. | Chronic recording of neural signals without the intent for aggressive stimulation [28]. |

| Sputtered Iridium Oxide (SIROF or IrOx) Electrode Tips | A coating with lower impedance and higher charge injection capacity, ideal for both recording and electrical stimulation [25] [28]. | Arrays intended for bidirectional BCIs, providing both control and sensory feedback via intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) [28]. |

| Parylene-C | A biocompatible polymer used as insulation for the electrode shanks and wires, preventing current leakage and signal crosstalk [25] [28]. | Standard insulation material for chronic neural implants; integrity is critical for long-term function [28]. |

| Neural Signal Processor | A specialized hardware system for amplifying, filtering, and digitizing signals from hundreds of electrode channels in real-time [25]. | Acquiring raw neural data for BCI control and scientific analysis [25] [30]. |

| Decoding Algorithms (e.g., Kalman Filter) | Computational methods that translate recorded neural population activity into predicted movement intentions or device commands [30]. | Enabling real-time, closed-loop control of external devices such as computer cursors and robotic limbs [30]. |

The journey from the Utah Array to modern high-channel-count systems represents a pivotal evolution in neurotechnology. The Utah Array established a robust, clinically viable platform, demonstrating that long-term, high-fidelity interfacing with the human brain is possible. Its documented safety and efficacy profile remains its most significant advantage for therapeutic applications [26]. In contrast, emerging high-density technologies promise unparalleled resolution for mapping neural circuits, a drive fueled by the demands of basic science rather than immediate clinical application [27]. The choice between these invasive technologies, and indeed the broader choice between invasive and non-invasive approaches, is not a matter of superiority but of alignment with research goals. The future lies not in one technology prevailing over another, but in the continued, parallel development of both—refining the proven clinical workhorse while pioneering the next-generation tools needed to unravel the brain's deepest mysteries.

The field of neural interfaces is undergoing a profound transformation, moving from simple read-out devices to sophisticated bidirectional systems that blur the line between biology and technology. This evolution is characterized by three interconnected macro-trends: the development of closed-loop systems that enable real-time bidirectional communication, the emergence of neuroadaptive technologies that dynamically respond to cognitive states, and the creation of biohybrid interfaces that improve biological integration through cellular and tissue engineering. These trends are reshaping the fundamental paradigm of human-machine interaction, offering new pathways to treat neurological disorders, restore lost function, and potentially enhance human capabilities.

The trajectory of neural interface development is fundamentally framed by the trade-offs between invasive and non-invasive approaches. Invasive systems (implanted inside the skull) provide unparalleled signal resolution and precision, enabling control of complex prosthetics and communication at near-conversational speeds for paralyzed individuals [1]. Non-invasive systems (worn on the scalp or skin) offer greater safety and accessibility, dominating current market applications, but are limited by lower signal fidelity due to signal attenuation through the skull and other tissues [31] [32]. The emerging macro-trends discussed in this guide are advancing both pathways, each with distinct advantages, challenges, and appropriate applications for researchers and drug development professionals to consider.

Closed-Loop Systems: Bidirectional Neural Communication

Core Concept and Comparative Advantage

Closed-loop brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) represent a significant leap beyond first-generation systems. Unlike open-loop interfaces that only record neural signals (output) or only stimulate the brain (input), closed-loop systems create a dynamic feedback cycle where neural activity is continuously decoded, and the system responds with tailored stimulation or other feedback in real time [1]. This self-adjusting loop mirrors the brain's own operational principles, leading to more stable and effective interventions.

The fundamental value proposition for researchers is the system's ability to detect and respond to physiological states as they occur. For instance, in managing epilepsy, a closed-loop system can detect the onset of a seizure from neural signatures and deliver immediate electrical stimulation to abort it, a stark contrast to continuous, non-contingent stimulation [33]. This responsive approach is not only more therapeutically efficient but also reduces the cumulative exposure to electrical stimulation, potentially minimizing side effects and extending device battery life.

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

A primary application of closed-loop systems is in adaptive neurostimulation for movement disorders. A typical experimental protocol for Parkinson's disease involves:

- Signal Acquisition: Implanted depth electrodes (e.g., in the subthalamic nucleus) continuously record local field potentials (LFPs).

- Biomarker Identification: Specific oscillatory patterns in the beta band (13-30 Hz) are established as biomarkers for hypokinetic motor states (bradykinesia and rigidity).

- Real-Time Processing: The embedded processor runs a decoding algorithm that quantifies the power of this beta-band activity.

- Adaptive Stimulation: When the beta power exceeds a predefined threshold, the system automatically triggers high-frequency deep brain stimulation (DBS). The stimulation amplitude may be titrated proportionally to the biomarker's intensity.

- Feedback Loop: As beta power normalizes, stimulation is reduced or ceased, preventing over-stimulation and allowing for natural neural activity [33].

The performance of this approach is superior to traditional open-loop DBS. The table below summarizes key comparative metrics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison: Open-Loop vs. Closed-Loop Deep Brain Stimulation

| Performance Metric | Open-Loop DBS | Closed-Loop aDBS |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulation Duty Cycle | Continuous (100%) | Intermittent (~30-60%) |

| Therapeutic Efficacy | Effective, but can fluctuate | More consistent symptom suppression |

| Side Effect Profile | Higher risk of speech/balance impairment | Reduced side effects due to targeted stimulation |

| Energy Consumption | Higher | Significantly lower, extends battery life |

| Adaptability to State | None; static parameters | Dynamic adjustment to patient's real-time need |

Another critical protocol involves motor rehabilitation after spinal cord injury or stroke. Here, the closed loop decodes motor intention from the cortical signals, drives a prosthetic limb or functional electrical stimulation (FES) of paralyzed muscles, and provides somatosensory feedback through cortical stimulation, creating a bridge that promotes neuroplasticity and recovery [33] [34].

System Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the core operational workflow of a closed-loop neural interface, showing the continuous cycle of signal processing, decoding, and adaptive response that defines this technology.

Closed-Loop Neural Interface Workflow

Neuroadaptive Technologies: AI Systems that Respond to Cognitive State

Core Concept and Comparative Advantage

Neuroadaptive technology represents a paradigm shift in human-computer interaction (HCI). These systems use passive BCIs to monitor a user's cognitive and emotional states in real-time—such as attention, cognitive load, and fatigue—and allow the AI system to dynamically adapt its behavior accordingly [35]. While closed-loop systems often focus on direct neurological intervention, neuroadaptive tech aims for seamless, context-aware collaboration between human and machine.

The strategic advantage for applied research lies in moving beyond explicit commands to implicit, context-driven interaction. For example, in a drug development setting, a neuroadaptive system could monitor researchers' focus levels during long data analysis sessions and automatically adjust interface complexity or trigger breaks to reduce error rates. This technology is particularly relevant for addressing the "AI alignment problem," where AI systems can be designed to optimize for not just task completion but also for human well-being and ethical values by responding to affective states [35].

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

A common protocol for developing a neuroadaptive system involves enhancing sustained attention in critical tasks:

- Signal Acquisition: A non-invasive EEG headset (e.g., a dry-electrode system) records brain activity, focusing on metrics like the theta/beta ratio and P300 event-related potentials, which are correlated with attention and workload.

- Baseline Calibration: The user's individual EEG signatures for states of "high focus" and "distraction" are established during a calibration task.

- Real-Time Classification: Machine learning models (e.g., Support Vector Machines or deep learning networks) classify the user's cognitive state on a second-by-second basis.

- System Adaptation: The connected software adapts based on the decoded state. For instance, if "high cognitive load" is detected, the system might simplify its display. If "drowsiness" is detected in a driver monitoring system, it could trigger an alert [31] [35].

The performance of these systems is gauged by improvements in human performance and reduction in error, rather than pure bit-rate communication.

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Neuroadaptive vs. Static Systems

| Performance Metric | Static System | Neuroadaptive System |

|---|---|---|

| User Error Rate | Baseline | Reduced by 15-30% in high-load tasks |

| Task Completion Time | Baseline | Improved efficiency in complex tasks |

| User Experience | Passive interaction | More intuitive, less frustrating |

| Bandwidth for Control | High (irrelevant) | Low (but highly relevant information) |

| Safety in Monitoring | N/A | Can predict lapses in attention ~ |

The trade-off is clear: while invasive interfaces like Neuralink aim for high-bandwidth data transfer, neuroadaptive systems prioritize the relevance of information over its volume, capturing critical condensed decisions related to values and moral reasoning that occur at much lower bit rates [35].

Biohybrid Interfaces: Enhancing Integration with Biology

Core Concept and Comparative Advantage

Biohybrid neural interfaces represent the cutting edge of biomimetic design, aiming to overcome the most significant barrier to chronic implant stability: the foreign body reaction (FBR). These interfaces incorporate living biological components—such as cells, tissues, or bioactive molecules—into the device structure to create a more seamless and functional integration with host neural tissue [33] [36].

The core value for long-term translational research is the potential for dramatically improved biocompatibility and long-term signal stability. Traditional rigid implants (e.g., silicon, platinum) trigger a chronic inflammatory response, leading to glial scar formation that insulates the electrode and degrades signal quality over weeks or months [36]. Biohybrid approaches seek to trick the body into accepting the device as a more natural part of its environment, thereby mitigating the FBR and preserving the viability of surrounding neurons.

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

Research in biohybrid interfaces spans multiple innovative strategies. A prominent protocol involves creating a "living electrode":

- Scaffold Fabrication: A soft, porous conductive scaffold is fabricated using materials like conductive hydrogels (e.g., PEDOT:PSS), soft elastomers (e.g., PDMS), or flexible meshes.

- Functionalization: The scaffold is coated with bioactive cues, such as cell-adhesion peptides (e.g., RGD, laminin) or anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., dexamethasone).

- Cell Seeding: The scaffold is seeded with neural progenitor cells or supportive cells like astrocytes. These cells proliferate and form a living layer on the electrode.

- Implantation: The biohybrid construct is implanted into the target neural tissue.

- Integration: The living layer on the device promotes integration with the host tissue, encouraging neuronal ingrowth and reducing the activation of microglia and astrocytes that lead to scarring [33] [36].

Performance data from animal models is promising. The table below contrasts traditional implants with advanced biohybrid designs.

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Traditional vs. Biohybrid Neural Implants

| Performance Metric | Traditional Rigid Implant | Biohybrid / Biomimetic Implant |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic Signal Amplitude | Degrades by ~40-70% over 6 months | Maintains >80% amplitude over 6 months |

| Electrode Impedance | Increases significantly over time | Remains more stable |

| Neuronal Density at Interface | Reduced by ~40% | Near-normal density preserved |

| Glial Scar Thickness | Significant (tens of micrometers) | Greatly reduced or minimal |

| Long-term Biocompatibility | Poor | Excellent |

Other protocols include the development of "regenerative electrodes" that release neurotrophic factors like BDNF to promote neuron survival and the use of stent-like electrodes (e.g., Stentrode) that are implanted via blood vessels, avoiding direct brain tissue penetration altogether [33] [37].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The development of biohybrid interfaces relies on a specialized toolkit of materials and biological factors.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Biohybrid Interface Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Polymers | PEDOT:PSS, Polypyrrole (PPy) | Form soft, electroactive coatings and scaffolds to reduce impedance and improve signal transduction. |

| Biomaterial Scaffolds | Polyimide, PDMS, SU-8, Hydrogels (e.g., GelMA) | Provide flexible, biocompatible substrates and encapsulation for electrodes. |

| Bioactive Coatings | Laminin, RGD peptides, L1 neural adhesion protein | Promote neuron adhesion and neurite outgrowth directly on the implant surface. |

| Controlled Release Systems | Dexamethasone-loaded hydrogels, BDNF-eluting coatings | Deliver anti-inflammatories or neurotrophic factors locally to suppress FBR and support neurons. |

| Cell Sources | Neural progenitor cells, Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC)-derived neurons/glia | Create living, biologically active layers on devices to facilitate host integration. |

Integrated Discussion and Future Outlook

The convergence of closed-loop, neuroadaptive, and biohybrid technologies points toward a future of increasingly sophisticated and symbiotic neural interfaces. The most advanced systems on the horizon will likely be closed-loop, biohybrid implants that not only read and write neural information with high fidelity but are also fully integrated into the biological fabric of the brain, operating stably for decades. Meanwhile, non-invasive neuroadaptive technology will become woven into the fabric of everyday life, creating computing environments that are responsive to our cognitive and emotional needs.

The strategic choice between invasive and non-invasive approaches remains, and will continue to be, dictated by the risk-benefit calculus of the application. Invasive systems, propelled by advances in biohybrid design, will dominate in restoring function for severe neurological injuries and disorders [1] [37]. Non-invasive systems, enhanced by more powerful AI decoding, will expand in consumer wellness, mental health, and human-computer interaction [7] [32]. As these macro-trends evolve, they will not only provide researchers with powerful new tools but also necessitate proactive engagement with the profound ethical and regulatory questions they raise concerning data privacy, identity, and equity.

Research and Clinical Translation: Methodologies and Therapeutic Applications

Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) represent a revolutionary technology that enables direct communication between the brain and external devices, bypassing traditional neuromuscular pathways. Within the broader thesis of neural interface research, the fundamental distinction between invasive and non-invasive approaches revolves around the critical trade-off between signal fidelity and clinical risk. Invasive BCIs, which involve surgically implanted electrodes that directly interface with brain tissue, offer unparalleled access to high-resolution neural signals but require neurosurgical intervention. In contrast, non-invasive approaches, such as electroencephalography (EEG), provide safer and more accessible platforms but contend with significant signal attenuation caused by the skull and scalp [38] [6].

This comparison guide objectively analyzes the performance of invasive BCIs against non-invasive alternatives, focusing specifically on their application in restoring motor function and communication for individuals with paralysis. The assessment is grounded in experimental data and clinical outcomes, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a clear evidence-based framework for evaluating these technologies. The core performance differentiator lies in the fundamental electrophysiology: invasive interfaces record detailed neural signals such as action potentials (APs) and local field potentials (LFPs), while non-invasive systems like EEG capture a spatially blurred and low-pass-filtered version of this activity, primarily from pyramidal neurons [6]. This biological reality creates an inherent performance gap that next-generation technologies are striving to narrow.

Performance Comparison: Invasive vs. Non-Invasive BCIs

The following tables synthesize quantitative data from clinical studies and commercial systems to compare the performance of invasive and non-invasive BCIs across key metrics and application-specific outcomes.

Table 1: Fundamental Signal and Performance Characteristics

| Performance Metric | Invasive BCI | Non-Invasive BCI |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Single neuron level (micrometers) [6] | Centimetre-scale resolution [38] |

| Temporal Resolution | Very High (up to several kHz) [6] | Lower (limited to <~90 Hz for EEG) [6] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | High [38] | Low to Moderate, susceptible to EMG noise [38] |

| Information Transfer Rate | High (~100-200 bits/min) [38] | Low (~5-25 bits/min) [38] |

| Typical Control Latency | Low (enables real-time control) [39] | Higher due to signal processing demands [39] |

| Key Signal Types | Action Potentials (APs), Local Field Potentials (LFPs) [6] | EEG, MEG, fNIRS [8] [39] |

Table 2: Application-Specific Outcomes in Paralysis

| Application & Outcome | Invasive BCI Performance | Non-Invasive BCI Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Prosthetic/Arm Control | Multi-fingered robotic arm control for grasping and manipulation [1] [40] | Limited to simple, discrete commands for device control [39] |

| Communication Speed | Speech decoding up to 62 words per minute [1]; 97% accuracy [41] | P300-based spelling devices with slower rates (~5-10 words/min) [42] [39] |

| Somatosensory Feedback | Bidirectional systems enabling sensation restoration via cortical microstimulation [6] | Largely unidirectional; feedback is typically visual or auditory [6] |

| Clinical Target Population | Severe paralysis (e.g., Locked-In Syndrome, tetraplegia) [38] [40] | Moderate to severe paralysis, rehabilitation [38] [43] |

| Motor Function Recovery | Enables control of complex exoskeletons [44] | BCI-guided therapy shows 30-50% motor improvement in stroke rehab [43] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

A critical evaluation of BCI performance requires an understanding of the underlying experimental methods. The following section details the protocols for key experiments that have established benchmarks for invasive BCI applications.

Protocol 1: Speech Decoding for Communication Restoration

Objective: To restore fluent communication in patients with paralysis or locked-in syndrome by decoding neural signals directly related to speech motor intention into text or synthetic speech [1] [41].

- Neural Signal Acquisition: A high-density electrode array (e.g., Utah Array or similar implant) is surgically placed over the cortical region responsible for speech motor control. This array records action potentials and local field potentials from populations of neurons [41] [6].

- Data Collection & Training: The patient is asked to attempt to speak or imagine speaking words and sentences. During this process, high-resolution neural data is recorded simultaneously with the intended speech output (or the text the patient intends to generate). This creates a large, labelled dataset mapping neural patterns to specific phonemes, words, or articulatory gestures [1].

- Decoder Training: Machine learning models (e.g., recurrent neural networks or linear decoders) are trained on the collected dataset. The model learns to map the complex neural activity patterns to the intended speech elements [1] [41].

- Real-Time Decoding: For communication, the trained decoder translates newly recorded neural signals into text or drives a speech synthesizer in real-time, allowing the patient to communicate at near-conversational speeds. Performance is validated by measuring output accuracy (e.g., word error rate) and information transfer rate (words per minute) [41].

Protocol 2: Robotic Arm Control for Motor Restoration

Objective: To enable individuals with tetraplegia to control a multi-degree-of-freedom robotic arm or prosthetic limb for performing activities of daily living [40] [6].

- Surgical Implantation: A microelectrode array (e.g., Utah Array) is implanted into the hand and arm area of the patient's primary motor cortex. This allows for recording from individual neurons tuned to specific movement directions, forces, and grips [40] [6].

- Neural Tuning Characterization: The patient observes or imagines performing various arm and hand movements. The firing rates of recorded neurons are analyzed to create a "tuning model" that correlates neural activity with specific movement parameters (e.g., velocity, position, grip type) [6].

- Closed-Loop System Calibration: The patient engages in closed-loop calibration, using their neural activity to control a cursor on a screen. This process allows the decoder algorithm to refine its parameters and for the patient's brain to adapt to the interface, a phenomenon known as neuroplasticity [6].

- Task Performance & Validation: The patient progresses to controlling a robotic arm to perform functional tasks, such as reaching for and grasping objects. Performance is quantitatively assessed using metrics like success rate, task completion time, and the number of degrees of freedom successfully controlled. The ultimate validation is the restoration of independent action, such as self-feeding [40].

BCI Closed-Loop Workflow: This diagram illustrates the core operational loop of an invasive BCI system for restoring function, highlighting the integration of neural signal decoding and sensory feedback.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Successful development and experimentation in invasive BCI research rely on a suite of specialized materials and technological components. The table below details these essential tools and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Invasive BCI Development

| Tool / Material | Function in Research & Development |

|---|---|

| Microelectrode Arrays (e.g., Utah Array, Neuropixels) | The primary physical interface with the brain; designed to record extracellular action potentials and local field potentials from populations of neurons with high fidelity [8] [6]. |

| Hermetic Encapsulation | Provides a biocompatible, protective barrier around the implant electronics, shielding them from the corrosive biological environment and preventing moisture ingress to ensure long-term stability [41]. |

| Neural Signal Acquisition ASIC | An Application-Specific Integrated Circuit (e.g., 128-channel acquisition chip) that performs front-end amplification, filtering, and analog-to-digital conversion of weak neural signals directly at the source, minimizing noise [41]. |

| Biocompatible Substrates (e.g., Polyimide, SU-8, Graphene) | Flexible and durable materials used for thin-film electrodes and implant substrates to minimize tissue damage, scarring, and the chronic immune response, thereby improving signal longevity [41] [40]. |

| Cortical Microstimulation Circuitry | Enables bidirectional functionality by delivering precise, low-current electrical pulses to neural tissue, thereby restoring sensory feedback (artificial sensation) or modulating neural circuits for therapeutic purposes [6]. |

| Decoder Algorithms (e.g., Kalman Filters, RNNs) | Machine learning models that translate raw, high-dimensional neural data into intended movement kinematics (velocity, grip force) or discrete commands (phonemes, letters) in real-time [1] [6]. |

BCI Technology Trade-offs: A logical breakdown of the core advantages, constraints, and resultant application profiles that distinguish invasive and non-invasive BCI approaches.

The objective comparison of performance data solidifies the position of invasive BCIs as the superior solution for restoring complex motor functions and high-bandwidth communication in cases of severe paralysis. Their ability to decode single-neuron activity and deliver bidirectional communication via cortical stimulation provides a level of control and feedback that non-invasive systems cannot currently match, as evidenced by achievements in robotic arm control and rapid speech decoding [1] [40] [6]. The primary trade-off remains the requirement for neurosurgery and the associated risks, which are diminishing with improved surgical techniques and more biocompatible materials [6].

The future of neural interfaces will likely not be a victory for one modality over the other, but a coexistence shaped by application-specific needs. Invasive interfaces are poised to address the most severe neurological disorders and serve as a platform for foundational neuroscience discovery. Concurrently, advances in non-invasive technologies like high-density EEG and wearable magnetoencephalography (MEG) are expected to expand their utility in rehabilitation, consumer applications, and as a screening tool for potential invasive implant candidates [8] [39]. For researchers and clinicians, this evolving landscape underscores the importance of a nuanced understanding of both invasive and non-invasive paradigms to effectively develop and deploy these transformative technologies.

The field of neural interfaces is undergoing a transformative shift from invasive to non-invasive approaches, driven by advancements in technology and a growing understanding of neural mechanisms. While invasive neural interfaces provide high spatial resolution and signal quality, they require surgical implantation, carrying risks of infection, tissue damage, and other complications [17]. In contrast, non-invasive interfaces offer safer, more accessible alternatives for clinical monitoring and therapeutic intervention, though they have historically faced challenges with signal quality and spatial resolution [17]. This evolution is particularly evident in three key clinical areas: epilepsy monitoring, stroke rehabilitation, and neurostimulation therapy.

The fundamental distinction between these approaches lies in their method of interaction with the nervous system. Invasive interfaces, such as stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG) and subdural electrodes (SDE), require surgical placement directly in or on brain tissue [45]. These methods provide superior signal quality for localizing seizure origins but are associated with higher infection rates (1.8% for SDE versus 0.3% for SEEG) and other surgical risks [45]. Non-invasive modalities leverage external sensors or stimulators to record or modulate brain activity through the scalp, making them suitable for long-term monitoring and broader patient populations [17].