Intrinsic Functional Network Neuroscience: Unlocking Individual Differences for Precision Medicine

This article synthesizes current research on Intrinsic Functional Network Neuroscience (ifNN) and its pivotal role in quantifying individual differences in brain organization.

Intrinsic Functional Network Neuroscience: Unlocking Individual Differences for Precision Medicine

Abstract

This article synthesizes current research on Intrinsic Functional Network Neuroscience (ifNN) and its pivotal role in quantifying individual differences in brain organization. We explore the foundational principles of brain network variability, methodological frameworks for reliable measurement, and optimization strategies for enhancing data quality. The content details how intrinsic connectivity networks serve as neural fingerprints, predicting individual traits in cognition, social behavior, and clinical susceptibility. For researchers and drug development professionals, we provide a critical analysis of validation approaches comparing task-evoked and resting-state architectures, concluding with translational implications for developing personalized biomarkers and targeted therapeutic interventions.

The Neural Fingerprint: How Intrinsic Brain Networks Reveal Fundamental Individual Differences

Defining Intrinsic Functional Network Neuroscience (ifNN) and Individual Variability

Intrinsic Functional Network Neuroscience (ifNN) is a multidisciplinary field that leverages network science and functional neuroimaging to model the brain as a graph comprising nodes (brain regions) and edges (their functional connections) derived from spontaneous brain activity [1]. This approach, central to human connectomics, provides a quantitative framework for investigating the system-level organization of intrinsic human brain function and its relationship to individual differences in cognition, behavior, and clinical conditions [1]. A core principle of ifNN is that the brain's functional architecture is highly individualized; the spontaneous, correlated fluctuations in brain activity observed at rest provide a neural fingerprint that is stable within an individual and can predict behavioral propensities and cognitive traits [2] [3] [4].

Methodological Foundations and Optimization for Individual Variability

The reliability of ifNN measurements is paramount for studying individual differences. Best practices have been systematically benchmarked using test-retest designs, such as those from the Human Connectome Project (HCP), to optimize the measurement reliability of individual differences in intrinsic brain networks [5] [1].

Core Methodological Principles for Reliable ifNN

Research has identified four essential principles to guide ifNN studies for high test-retest reliability [5] [1]:

- Whole-Brain Node Definition: Use a whole-brain parcellation to define network nodes, inclusive of subcortical and cerebellar regions.

- Multi-Band Edge Construction: Construct functional networks using spontaneous brain activity across multiple slow frequency bands.

- Topological Economy: Optimize the topological economy of networks at the individual level.

- Specific Network Metrics: Characterize information flow with specific metrics of integration and segregation.

ifNN Analysis Workflow

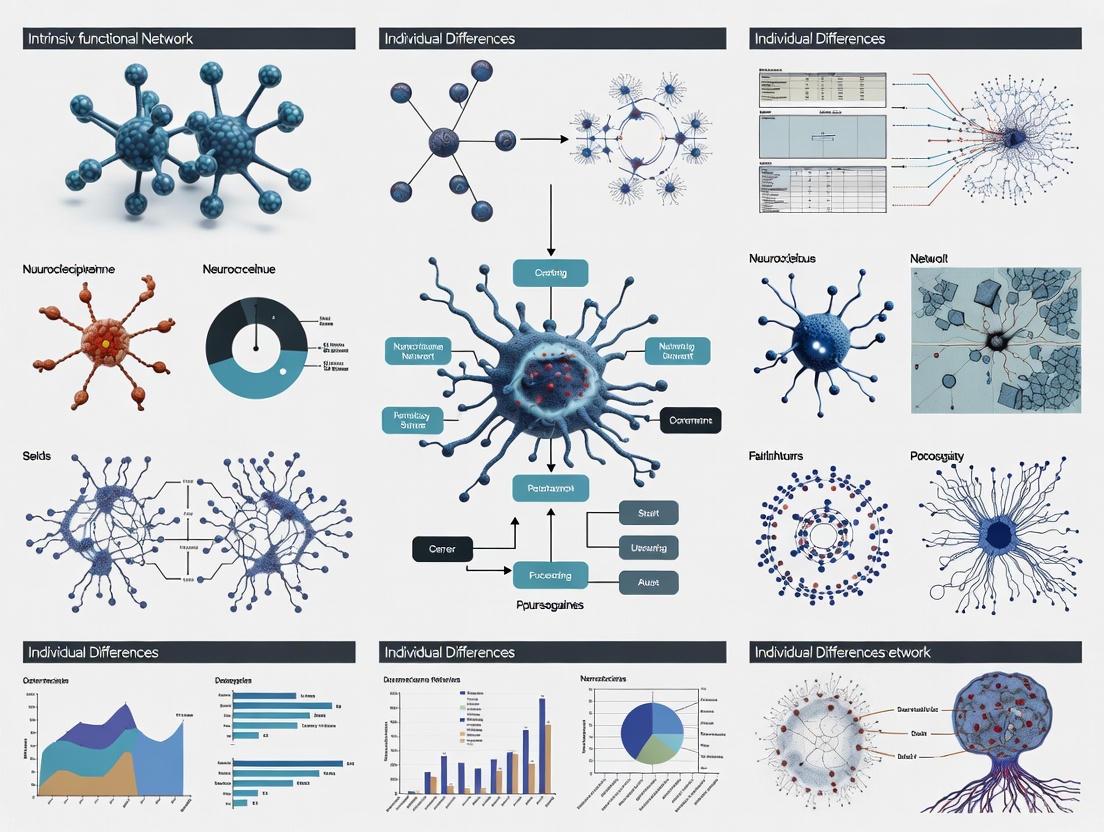

The following diagram illustrates the standard ifNN analytical pipeline, from data acquisition to the final assessment of individual differences.

Quantitative Reliability of Methodological Choices

The table below summarizes the impact of key analytical choices on the reliability of individual difference measurements, as identified in systematic evaluations.

Table 1: Impact of Analytical Choices on Measurement Reliability in ifNN

| Analytical Stage | High-Reliability Choice | Impact on Reliability | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Node Definition | Whole-brain parcellation including subcortical and cerebellar regions | Increases between-subject variability (ΔVb > 0) for better individual differentiation | [5] [1] |

| Edge Construction | Using multiple slow frequency bands (e.g., 0.01-0.1 Hz) | Captures more reliable, individualized network signatures | [5] [1] |

| Graph Filtering | Topology-based edge filtering methods | Optimizes network economy, reducing within-subject noise (ΔVw < 0) | [1] |

| Network Metrics | Multimodal metrics of integration and segregation | Provides highly reliable, individualized measurements | [5] [1] |

Experimental Protocols for ifNN Research

Protocol: Optimizing ifNN Pipelines for Test-Retest Reliability

This protocol is designed to systematically evaluate and optimize an ifNN analysis pipeline for measuring individual differences, based on the HCP test-retest design [5] [1].

1. Objective: To identify the combination of analytical decisions (parcellation, frequency band, filtering, graph metric) that produces the most reliable measurement of individual differences in intrinsic functional networks.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Imaging Data: Test-retest rfMRI datasets, such as from the Human Connectome Project (HCP).

- Parcellation Atlases: A variety of whole-brain atlases (e.g., Smith atlas, NeuroMark templates).

- Computing Software: Environments for network analysis (e.g., Python with NetworkX, MATLAB toolboxes).

- Quality Control Tools: Framewise displacement and registration quality metrics.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Data Preparation. Obtain minimally preprocessed rfMRI data from a test-retest cohort. Rigorous quality control is essential, excluding subjects with excessive head motion (e.g., mean framewise displacement > 0.25 mm) [6].

- Step 2: Node Definition. For each subject, extract BOLD time series using multiple different whole-brain parcellation atlases.

- Step 3: Edge Construction. For each parcellation, calculate a functional connectivity matrix (e.g., using Pearson correlation). Perform this step using different frequency filters (e.g., slow-4, slow-5 bands).

- Step 4: Graph Filtering. Apply different edge-weight filtering schemes (e.g., proportional, fixed-density, topology-based) to the connectivity matrices to create binary or weighted graphs.

- Step 5: Network Measurement. Calculate a suite of global and local graph theory metrics (e.g., efficiency, clustering, betweenness centrality) for each resulting graph.

- Step 6: Reliability Assessment. For each unique pipeline combination, calculate the test-retest reliability of each graph metric using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC). pipelines yielding the highest ICC values are considered optimal.

4. Analysis: The change in reliability is assessed by examining the between-subject variability (Vb) and within-subject variability (Vw). An optimal pipeline will simultaneously increase Vb and decrease Vw [1].

Protocol: Linking Intrinsic Connectivity to Behavior via Multivariate Prediction

This protocol details a framework for using intrinsic functional connectivity to predict individual differences in behavioral or cognitive phenotypes [3].

1. Objective: To determine if resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) within specific large-scale networks (e.g., Frontoparietal Network) can predict an individual's score on a continuous behavioral measure (e.g., propensity for third-party punishment).

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Behavioral Task: A validated paradigm to quantify the phenotype of interest (e.g., an economic game).

- Imaging Data: High-quality, single-session rfMRI data from participants.

- Analysis Software: Multivariate regression tools (e.g., linear support vector regression, ridge regression).

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Phenotype Measurement. Acquire behavioral data from all participants outside the scanner.

- Step 2: rs-fMRI Acquisition. Collect task-free rfMRI data from participants.

- Step 3: Network Definition. Define large-scale networks of interest (e.g., FPN, DMN, Salience Network) using a validated atlas or template.

- Step 4: Connectivity Feature Extraction. For each subject, calculate the mean RSFC within each network of interest (i.e., the average connectivity strength between all node pairs within the FPN).

- Step 5: Multivariate Prediction Model. Train a multivariate regression model using the within-network RSFC patterns from all networks as features to predict the continuous behavioral scores.

- Step 6: Model Validation. Validate the model using a cross-validation or hold-out validation approach to test its generalizability.

4. Analysis: The significance of the prediction is evaluated by testing if the correlation between the predicted and actual behavioral scores is significantly greater than zero. The specific weights of each network in the model reveal their relative contribution to the behavior [3].

Advanced Frameworks: Gradients and Fine-Grained Networks

Beyond discrete networks, the brain's intrinsic organization follows continuous functional gradients. A seminal study demonstrated that intrinsic functional connectivity is organized along three interdependent gradients forming a circumplex structure, indicating fluid transitions between network states rather than rigid modular boundaries [7]. These gradients correlate with functional features (e.g., external vs. internal information processing) and anatomical centrality, providing a more nuanced model for understanding individual variability [7].

Furthermore, very high-order analytic models are revealing the fine-grained architecture of intrinsic connectivity. Applying group-independent component analysis (ICA) to massive datasets (>100,000 subjects) can generate templates with 500 or more components, capturing distinct subnetworks within larger systems [6]. This enhanced granularity, particularly in cerebellar and paralimbic regions, improves the detection of subtle, individual-level differences associated with neuropsychiatric disorders [6].

Hierarchical and Gradient-Based Organization of ifNN

The following diagram illustrates the interdependent gradient-based model of intrinsic functional connectivity, which moves beyond discrete parcellations.

Table 2: Essential Resources for ifNN and Individual Differences Research

| Resource Category | Specific Example(s) | Function in ifNN Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Repositories | Human Connectome Project (HCP) [5] [2], Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE) [8] | Provide large-scale, high-quality test-retest and cohort datasets essential for reliability testing and individual difference modeling. |

| Parcellation Atlases | Whole-brain atlases (e.g., NeuroMark-fMRI-500 [6], Smith Atlas [8]) | Define the nodes (brain regions) of the functional network, with higher-order atlases providing finer granularity for detecting subtle individual differences. |

| Analysis Pipelines & Software | FSL, GCN-based graph learning tools [8], Brain Modulyzer [9] | Enable the processing of rfMRI data, construction of functional connectivity matrices, computation of graph metrics, and interactive visualization of network properties. |

| Multivariate Prediction Tools | Support Vector Regression, Ridge Regression, Custom MATLAB/Python scripts [3] | Allow researchers to build models that predict continuous individual traits from whole-brain or network-specific functional connectivity patterns. |

| Reliability Assessment Tools | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) scripts, Linear Mixed Model (LMM) packages [1] | Quantify the test-retest reliability of graph measurements, which is the foundation for any robust study of individual differences. |

Intrinsic functional network neuroscience (ifNN) leverages spontaneous, low-frequency fluctuations in the brain's resting-state activity to map the organization of large-scale functional networks and understand the biological basis of individual differences [1]. A core principle of this field is that this spontaneous activity, far from being neural "noise," is highly structured and exhibits spatiotemporal dynamics that provide a reliable window into stable, trait-like characteristics of an individual's brain [10] [11]. The quest for reliable biomarkers in psychiatry and neurology is driving the refinement of ifNN methodologies, with a premium placed on measurements that are reproducible and can effectively discriminate between individuals [1] [12]. This technical guide details the core principles, metrics, and experimental protocols that underpin the use of spontaneous brain activity for capturing stable brain traits, framed within the context of individual differences research.

Core Principles of Stable Trait Measurement from Spontaneous Activity

The following principles are critical for optimizing the measurement of stable, trait-like features from spontaneous brain activity, ensuring high reliability and discriminability between individuals.

Principle 1: Comprehensive Whole-Brain Parcellation for Node Definition Defining network nodes using a whole-brain parcellation that includes subcortical and cerebellar regions is essential for capturing the full repertoire of individual-specific brain organization. Studies have demonstrated that such comprehensive parcellations optimize the between-subject variability of network metrics, thereby enhancing their reliability and ability to differentiate individuals [1].

Principle 2: Multi-Band Functional Connectivity for Edge Construction Constructing functional networks (edges) using spontaneous brain activity across multiple slow frequency bands (e.g., both typical and high-frequency slow bands) increases the richness of the connectivity information captured. This multi-band approach has been shown to yield more reliable measurements of individual differences compared to using a single, standard frequency band [1].

Principle 3: Optimization of Topological Economy Employing network construction methods that optimize the topological economy at the individual level improves the quality of the derived graph metrics. These methods, which often involve topology-based filtering of edges, enhance the reliability of network measurements by increasing their between-subject variance while reducing within-subject noise [1].

Principle 4: Characterization of Information Flow Selecting graph metrics that specifically characterize information flow is crucial. Metrics quantifying integration (the ease of information transfer across the network) and segregation (the degree of specialized processing within clusters of regions) have been consistently identified as having high reliability for capturing individual differences [1].

Principle 5: Accounting for Non-Random Temporal Dynamics Spontaneous brain activity is not random in time. Characteristic patterns of functional connectivity transition in specific sequential orders [10]. The temporal organization of these transitions—such as the order in which the brain cycles through different network states—is itself a stable and conserved feature, offering another dimension for individual differentiation beyond static connectivity [10].

Key Metrics and Their Psychometric Properties

Research has identified several metrics derived from resting-state fMRI that exhibit good to excellent test-retest reliability, making them strong candidates for studying stable traits. The table below summarizes key metrics and their properties.

Table 1: Reliable Metrics for Capturing Individual Differences from Resting-State fMRI

| Metric | Description | Measured Property | Test-Retest Reliability | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude of Low-Frequency Fluctuations (ALFF) | The power of spontaneous BOLD signal oscillations within a typical low-frequency range (e.g., 0.01-0.1 Hz) [12]. | Spontaneous regional brain activity | Strong ICC in DMN, CEN, and SN at ultra-high-field [12] | Serves as an individual-specific "barcode" when combined with other dynamic features [11]. |

| Regional Homogeneity (ReHo) | Measures the similarity or synchronization between the time series of a given voxel and its nearest neighbors [12]. | Local functional connectivity | Strong ICC in major resting-state networks at ultra-high-field [12] | High reliability supports its use as a potential biomarker. |

| Degree Centrality (DC) | The sum of weights from all functional connections linked to a node, reflecting its importance for long-range connectivity [12]. | Global functional connectivity | Strong ICC in major resting-state networks at ultra-high-field [12] | A cornerstone of functional connectome "fingerprinting" [1]. |

| Fractional ALFF (fALFF) | The ratio of the power in the low-frequency range to the power in the entire frequency range detectable, thought to improve specificity [12]. | Spontaneous regional brain activity | Moderate ICC [12] | Useful but may be less stable than ALFF. |

| Internetwork Connectivity | The functional connectivity between major large-scale networks like the Default Mode (DMN), Central Executive (CEN), and Salience (SN) Networks [12]. | Between-network integration | Strong ICC for CEN/SN; Moderate for DMN/CEN and DMN/SN [12] | Altered internetwork connectivity is a transdiagnostic feature in psychopathology [13]. |

Experimental Protocol for Reliability Assessment

To establish the reliability of any metric for individual differences research, a test-retest design is mandatory. The following workflow, based on the Human Connectome Project, outlines a standard protocol:

Detailed Methodology:

- Participant Recruitment: Recruit a cohort of healthy participants. A larger sample size (e.g., N > 50) provides more stable reliability estimates [1].

- Scanning Sessions: Acquire resting-state fMRI data across at least two separate sessions. The HCP and other open datasets typically use intervals from weeks to months to assess stability over time [1]. Each session should include a sufficiently long scan duration (e.g., 12+ minutes) to achieve robust measurements [12].

- Data Preprocessing: Apply a standardized preprocessing pipeline. This typically includes slice-time correction, realignment, normalization to a standard space, and nuisance regression (to remove signals from head motion, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid). The use of ultra-high-field (7T) MRI can enhance spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio, improving reliability [12].

- Metric Extraction: Calculate the brain metrics of interest (e.g., ALFF, ReHo, DC) for each participant and each session.

- Reliability Analysis: Use a Linear Mixed Model (LMM) to partition the variance of the measurements into between-subject (Vb) and within-subject (Vw) components [1]. The formula for the model is:

ϕijk = γ000 + p0k + v0jk + eijkwhereγ000is the group mean,p0kis the subject effect (between-subject variance),v0jkis the visit effect, andeijkis the measurement residual (within-subject variance). - Reliability Evaluation: Calculate the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC). ICC is defined as the ratio of between-subject variance to the total variance (between-subject + within-subject). An ICC > 0.6 is generally considered moderate, and >0.75 is excellent for individual-level measurements [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table catalogs key resources and methodological choices critical for conducting robust ifNN research on individual differences.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Solutions for ifNN

| Item / Solution | Function / Role in ifNN Research |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Resting-State fMRI Data | The primary data source for estimating functional connectivity and computing regional metrics. Data from consortia like the Human Connectome Project (HCP) or UK Biobank are gold standards [1] [11]. |

| Whole-Brain Parcellation Atlas | A predefined map that divides the brain into discrete regions (nodes) for network construction. Essential for implementing Principle 1 (e.g., the HCP's MMP atlas) [1]. |

| Ultra-High-Field (7T) MRI Scanner | Provides increased spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio for fMRI data, which enhances the test-retest stability of derived metrics like ALFF, ReHo, and DC [12]. |

| Linear Mixed Models (LMM) | The statistical framework for decomposing measurement variance and calculating intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) to assess reliability [1]. |

| Graph Theory Software (e.g., igraph) | Software libraries used to calculate network-based metrics of integration and segregation (e.g., efficiency, centrality, clustering) from adjacency matrices [1] [14] [15]. |

| Mind Wandering Questionnaire (MWQ) | A self-report scale that quantifies dispositional MW as a trait-like measure of spontaneous cognition, allowing for the investigation of brain-behavior relationships [13]. |

From Dynamics to Behavior: A Workflow for Generalizable Associations

Recent advances focus on moving beyond static connectivity to capture intra-regional dynamics. The following workflow illustrates how to extract and link these dynamic features to behavior in a generalizable manner.

Detailed Methodology:

- Data Input: Begin with high-quality resting-state fMRI data from large, diverse cohorts (e.g., UK Biobank, Lifespan HCP) to ensure statistical power and generalizability [11].

- Feature Extraction: Move beyond simple functional connectivity. Extract a comprehensive set of features (e.g., nonlinear autocorrelations, measures of random walk dynamics, power spectral characteristics) from the haemodynamic time series of each brain region. This can yield thousands of potential features per region [11].

- Barcode Identification: Identify a reliable subset of these dynamic features that demonstrate high test-retest reliability and serve as an individual-specific signature or "barcode" [11]. This step is analogous to the reliability optimization described in Section 3.1.

- Multivariate Modeling: Use multivariate statistical models (e.g., canonical correlation analysis, machine learning) to link the reliable neural "barcode" to behavioral traits. For example, research has linked nonlinear autocorrelations in unimodal regions to substance use and random walk dynamics in higher-order networks to general cognitive ability [11].

- Cross-Validation: Validate the discovered brain-behavior associations across independent datasets and different life stages to ensure they are not specific to a single sample but are truly generalizable [11].

The core principles outlined in this guide—comprehensive node definition, multi-band connectivity, topological optimization, and a focus on reliable metrics of integration and segregation—provide a robust framework for using spontaneous brain activity to uncover stable brain traits. The rigorous application of test-retest reliability assessments and the emerging focus on intra-regional temporal dynamics are pushing the field toward the identification of generalizable, clinically viable biomarkers. As methodologies continue to mature and datasets grow larger, intrinsic functional network neuroscience is poised to make significant contributions to personalized medicine in neurology and psychiatry by providing a reliable window into the individual brain's functional architecture.

Intrinsic functional network neuroscience has redefined our understanding of human brain organization by revealing large-scale, domain-general networks that constitute the fundamental architecture of cognition. Among these, three canonical networks—the Default Mode Network (DMN), Frontoparietal Network (FPN), and Salience Network (SN)—serve as primary systems whose interactions form the core of human cognitive function and its individual variation [16]. Research has evolved from a modular perspective of brain function to a systemic network paradigm that recognizes the dynamic, hierarchical organization of interconnected neural systems [16]. The DMN, FPN, and SN operate in a tightly coordinated manner, with the SN potentially acting as a dynamic "switch" between the internally-focused DMN and externally-oriented FPN [16]. Understanding the individual differences in the organization and interaction of these networks provides crucial insights into both typical cognitive variability and the neurobiological mechanisms underlying psychiatric and neurological disorders. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these three core networks, their functional significance, methodological approaches for their investigation, and their implications for research in individual differences, with particular relevance for drug development and therapeutic innovation.

Network Anatomy and Functional Significance

Default Mode Network (DMN)

The Default Mode Network comprises a set of brain regions that demonstrate heightened activity during wakeful rest and internally-directed mental processes. Key anatomical nodes include the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), precuneus, medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and angular gyrus [17]. The DMN creates a coherent "internal narrative" central to the construction of a sense of self and is active during mind-wandering, thinking about others and oneself, remembering the past, and planning for the future [17].

Functionally, the DMN can be divided into subsystems with specialized roles:

- Dorsal medial subsystem: Involved in thinking about others, incorporating the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC), temporoparietal junction (TPJ), lateral temporal cortex, and anterior temporal pole [17].

- Medial temporal subsystem: Supports autobiographical memory and future simulations, involving the hippocampus, parahippocampus, retrosplenial cortex, and posterior inferior parietal lobe [17].

Individual differences in DMN connectivity have significant cognitive implications. Research demonstrates that within-DMN connectivity and efficiency show significantly weak positive correlations with trial-and-error learning performance but not with errorless learning, suggesting the network's particular relevance for learning methods that engage self-monitoring and evaluative processes [18]. In ADHD populations, reduced within-DMN connectivity differentiates combined-type (ADHD-C) from inattentive-type (ADHD-I) presentations and is negatively associated with hyperactivity-impulsivity symptoms [19].

Frontoparietal Network (FPN)

The Frontoparietal Network, also referred to as the Central Executive Network (CEN), serves as a primary system for goal-directed cognition and executive control. Its core structural components include the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and posterior parietal cortex (PPC) [16]. The FPN peaks in activation during tasks requiring cognitive effort and is essential for task selection, executive function, attentional control, working memory, and decision-making in the context of goal-directed behavior [16].

The functional architecture of the FPN supports its role in complex cognitive processes. Network neuroscience approaches reveal that the structural and functional topology of the FPN predicts individual differences in cognitive abilities, including musical perceptual abilities mediated by working memory processes [20]. The integration efficiency of key frontoparietal regions correlates positively with perceptual abilities, with functional networks influencing these abilities through working memory processes and structural networks affecting them through sensory integration [20].

Neuroplasticity within the FPN is evident in intervention studies. Brain Computer Interface (BCI) training conducted over five consecutive days enhanced functional connectivity within the FPN, specifically in the bilateral prefrontal cortices and right posterior parietal cortex, resulting in improved alerting and executive control network efficiencies [21].

Salience Network (SN)

The Salience Network plays a critical role in detecting behaviorally relevant stimuli and coordinating neural resources in response to salient events. Its principal hubs include the anterior insula (AI) and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) [22] [16]. Additional regions frequently associated with the SN include the amygdala, ventral striatum, thalamus, and inferior parietal lobule/temporoparietal junction [23]. The SN contains specialized von Economo neurons in the AI/dACC, which may support rapid information processing and network switching [16].

The SN serves as a dynamic switch between the DMN and FPN, facilitating transitions between self-focused introspection and externally-oriented attention in response to cognitive demand [16]. This "switching" function enables appropriate allocation of attentional resources to the most salient internal or external stimuli [16]. Beyond this coordinating role, the SN is integral to processing reward, motivation, emotion, pain, and interoceptive awareness [23] [16].

Individual differences in SN function have significant clinical implications. In Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), increased baseline resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) within the SN—particularly in the rostral anterior cingulate—predicts greater response to both placebo and antidepressant treatment [24]. The SN also plays a key role in substance use disorders (SUDs), where alterations in SN structure and function contribute to abnormal salience attribution to drug-related cues, impaired cognitive control, and compromised decision-making [23]. Similarly, both physical and socioemotional pain processing engage the SN, with AI activation integrating sensory and interoceptive inputs to form subjective pain perceptions, while ACC evaluates pain saliency to guide attention and action [23].

Table 1: Core Anatomical Components and Primary Functions of Canonical Brain Networks

| Network | Core Anatomical Hubs | Primary Cognitive Functions | Individual Differences Correlates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Default Mode Network (DMN) | Posterior cingulate cortex, Medial prefrontal cortex, Precuneus, Angular gyrus [17] | Self-referential thought, Autobiographical memory, Mental simulation, Social cognition [17] | Within-network connectivity correlates with trial-and-error learning [18]; Reduced connectivity in ADHD-C type [19] |

| Frontoparietal Network (FPN) | Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, Posterior parietal cortex [16] | Executive control, Working memory, Goal-directed attention, Cognitive flexibility [16] | Network integration efficiency predicts musical perceptual abilities [20]; Plasticity in response to BCI training [21] |

| Salience Network (SN) | Anterior insula, Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex [22] [16] | Salience detection, Interoception, Pain processing, Network switching [23] [16] | Connectivity predicts placebo response in MDD [24]; Altered connectivity in substance use disorders [23] |

Interactions and Dynamics Among Canonical Networks

The DMN, FPN, and SN do not operate in isolation but rather form a tightly integrated system that enables adaptive human cognition. The Triple Network Model proposes that the SN serves as a dynamic switch between the DMN and FPN, facilitating transitions between internally-focused and externally-directed cognition [16]. In this model, the right anterior insula acts as a key hub that influences both FPN and DMN, with stronger negative correlation between DMN and FPN associated with higher executive function efficiency [16].

This dynamic interaction framework has profound implications for understanding individual differences and psychopathology. Widespread disruption in predictive coding across multiple hierarchical levels has been associated with SN dysfunction across diverse clinical conditions including depression, chronic pain, anxiety, schizophrenia, and autism [16]. Hyperactivity of the SN is linked to affective disorders and high anxiety, while hypoactivity is observed in conditions such as autism and neurodegenerative diseases [16].

The intrinsic functional architecture of these networks provides the foundation for cognitive individual differences. Research demonstrates that the strength of within-network connectivity and between-network anti-correlations relates to learning capabilities, with DMN connectivity specifically associated with trial-and-error learning performance but not errorless learning [18]. This suggests that the DMN may support the evaluative and self-monitoring processes required for learning through failure and correction.

Table 2: Clinical Associations of Canonical Network Dysregulation

| Network | Hyperactivity/Hyperconnectivity | Hypoactivity/Hypoconnectivity | Treatment Prediction Potential |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMN | Excessive self-focus, Rumination in depression [24] | Reduced self-awareness, Atypical social cognition | Not specifically addressed in available literature |

| FPN | Not specifically addressed in available literature | Cognitive control deficits, Impaired working memory [24] | Not specifically addressed in available literature |

| SN | Anxiety, Neuroticism, Affective disorders [16] | Autism, Neurodegenerative diseases [16] | Predicts placebo and antidepressant response in MDD [24] |

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Resting-State Functional Connectivity (rsFC) Analysis

Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) has emerged as a primary methodology for investigating intrinsic brain network organization. The fundamental principle underlying rsFC analysis is that spontaneous, low-frequency fluctuations in the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal occurring at rest exhibit temporal coherence between brain regions that constitute functional networks [24].

Experimental Protocol: rsFC Acquisition and Analysis

- Data Acquisition: Participants undergo fMRI scanning while maintaining wakeful rest with eyes open or closed, focusing on a fixation cross. Typical parameters include TR=2000ms, TE=30ms, voxel size=3×3×3mm³, 5-8 minute acquisition duration [24].

- Preprocessing: Steps include slice-time correction, realignment, normalization to standard space (e.g., MNI), spatial smoothing (6mm FWHM), and band-pass filtering (0.01-0.1 Hz) to reduce physiological noise and low-frequency drift.

- Connectivity Analysis: Two primary approaches are employed:

- Seed-based correlation: Time series from seed regions (e.g., PCC for DMN) are extracted and correlated with all other voxels [17].

- Independent Component Analysis (ICA): A data-driven approach that identifies spatially independent components corresponding to intrinsic networks without a priori seed selection [24].

- Statistical Analysis: Group-level comparisons of connectivity strength using general linear models, correlation with behavioral measures, and machine learning approaches for individual prediction [24].

Graph Theoretical Analysis

Graph theory provides a mathematical framework for quantifying the topological organization of brain networks by modeling the brain as a complex graph comprising nodes (brain regions) and edges (structural or functional connections) [20].

Experimental Protocol: Graph-Based Network Construction and Analysis

- Network Construction:

- Node Definition: Parcellate the brain into distinct regions using anatomical (AAL) or functional parcellations.

- Edge Definition: For functional networks, calculate correlation matrices between regional time series; for structural networks, utilize diffusion tractography to quantify white matter connections [20].

- Graph Metric Calculation:

- Integration Metrics: Global efficiency, characteristic path length.

- Segregation Metrics: Clustering coefficient, modularity.

- Centrality Metrics: Betweenness centrality, eigenvector centrality.

- Statistical Analysis: Compare graph metrics between groups, correlate with behavioral measures, conduct network-based statistic (NBS) for edge-wise comparisons [19].

Task-Based fMRI for Network Dynamics

While rsFC examines intrinsic connectivity, task-based fMRI probes network dynamics during specific cognitive operations, revealing how network interactions support cognition.

Experimental Protocol: Color-Name Association Task for Learning Method Comparison

- Task Design: Participants perform a color-name association task under two learning conditions: errorless learning (prevention of errors during acquisition) and trial-and-error learning (normal learning with errors) [18].

- fMRI Acquisition: Scan during task performance with event-related or block design.

- Analysis Approach: Compare activation and connectivity patterns between learning conditions, examine correlation between individual learning benefits and intrinsic connectivity measures [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Methodologies and Analytical Tools for Intrinsic Network Research

| Method/Tool | Primary Function | Application in Individual Differences Research |

|---|---|---|

| Resting-State fMRI | Measures spontaneous BOLD fluctuations during wakeful rest | Quantifies intrinsic functional connectivity; identifies network biomarkers of cognitive traits and clinical conditions [24] |

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) | Data-driven approach to identify spatially independent network components | Extracts canonical networks without a priori seeds; enables comparison across individuals and groups [24] |

| Seed-Based Correlation Analysis | Examines temporal correlations between seed region and all other brain voxels | Tests specific hypotheses about network connectivity; assesses individual differences in network integrity [17] |

| Graph Theory Metrics | Quantifies network topology using mathematical graph measures | Characterizes individual differences in network efficiency, segregation, and integration [20] |

| Network-Based Statistics (NBS) | Non-parametric method for identifying significant connectivity differences | Identifies specific connectional differences between groups while controlling for multiple comparisons [19] |

| Diffusion MRI/Tractography | Maps white matter pathways and structural connectivity | Examines structural foundations of functional networks; correlates white matter integrity with network function [20] |

| Relevance Vector Regression (RVR) | Multivariate machine learning approach for prediction | Predicts individual treatment response or behavioral traits from network connectivity patterns [24] |

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutic Innovation

The individual differences approach to intrinsic network neuroscience offers transformative potential for drug development and therapeutic innovation. By identifying neurobiological subtypes based on network organization rather than symptomatic presentation, this approach enables more targeted interventions and personalized treatment strategies.

In Major Depressive Disorder, increased baseline resting-state functional connectivity within the salience network—particularly in the rostral anterior cingulate—predicts greater response to both placebo and antidepressant treatment [24]. This suggests that SN connectivity could serve as a biomarker for identifying patients who may respond to lower medication doses or non-pharmacological approaches, potentially reducing exposure to ineffective treatments and their associated side effects.

The emerging framework of precision neurodiversity represents a paradigm shift from pathological models to personalized frameworks that view neurological differences as adaptive variations [25]. This approach has identified distinct neurobiological subgroups in conditions such as ADHD that are not detectable by conventional diagnostic criteria but exhibit significant differences in functional network organization [25]. Such advances enable the development of more targeted interventions based on an individual's unique "neural fingerprint" rather than symptom clusters alone.

Network-based biomarkers also show promise for evaluating treatment efficacy. For instance, Brain Computer Interface training produces measurable changes in FPN connectivity that correlate with improved attentional network efficiency [21]. Similar approaches could be applied to assess the neural effects of pharmacological interventions, providing objective metrics of target engagement and treatment response beyond behavioral measures alone.

The investigation of individual differences in the Default Mode, Frontoparietal, and Salience Networks represents a paradigm shift in neuroscience with far-reaching implications for understanding human cognition, neurodiversity, and therapeutic development. The DMN, FPN, and SN form a core triple network system whose dynamic interactions support the flexible cognitive repertoire that defines human experience. Individual variations in the structural and functional organization of these networks—quantifiable through resting-state functional connectivity, graph theoretical analysis, and task-based fMRI—provide crucial insights into the neurobiological underpinnings of cognitive strengths, vulnerabilities, and clinical manifestations.

The precision neurodiversity framework marks a critical evolution from pathological models to personalized approaches that honor neurological differences as adaptive variations within the human spectrum [25]. This perspective, coupled with advances in network neuroscience methodologies, enables the identification of meaningful neurobiological subgroups that transcend conventional diagnostic boundaries and offer new pathways for targeted interventions. For drug development and therapeutic innovation, network-based biomarkers hold exceptional promise for predicting treatment response, personalizing interventions, and assessing target engagement, ultimately advancing toward truly individualized approaches to brain health and cognitive enhancement.

This whitepaper synthesizes current research on how individual differences in intrinsic brain network variability underlie core aspects of human cognition, including general intelligence and mentalizing capabilities. Evidence from functional neuroimaging indicates that the brain's frontoparietal networks, particularly those involved in higher-order cognitive integration, demonstrate systematic variability across individuals that correlates with cognitive performance. This variability follows a distinct spatial pattern across the cortex, is evolutionarily rooted, and provides a biological substrate for understanding individual cognitive differences in both healthy and clinical populations. The findings presented herein support a theoretical framework wherein individual cognitive differences emerge from characteristic patterns of functional network architecture and dynamics.

The paradigm in cognitive neuroscience has shifted from studying modular brain functions to understanding the brain as a complex system of intrinsically organized, large-scale networks. Research over the past two decades has established that the brain's spontaneous activity during rest is highly structured and organized into specific functional networks [26]. These resting-state networks (RSNs) include the default mode network (DMN), frontoparietal control networks, salience network, and sensory-motor networks, each supporting distinct cognitive functions.

Within this framework, the concept of individual differences in brain connectivity has emerged as a crucial area of study. The human brain exhibits striking inter-individual variability in neuroanatomy and function that is reflected in great individual differences in human cognition and behavior [27]. This variability represents the joint output of genetic and environmental influences that differentially impact various brain systems. A key finding is that neural systems subserving higher-order association and integration processes demonstrate greater variability than those implicated in unimodal processing [27].

This whitepaper examines how intrinsic functional network variability provides the neural basis for individual differences in two key cognitive domains: general intelligence and mentalizing capabilities (the capacity to understand others' mental states). We integrate evidence from multiple neuroimaging modalities, present quantitative comparisons, and provide methodological guidance for researchers investigating these relationships.

Theoretical Foundations and Neurobiological Basis

Defining Intelligence in Network Terms

Intelligence can be defined as a general mental ability for reasoning, problem solving, and learning. Due to its general nature, intelligence integrates cognitive functions such as perception, attention, memory, language, and planning [28]. Structural and functional neuroimaging studies have consistently identified a frontoparietal network as particularly relevant for intelligence. This same network also underlies cognitive functions related to perception, short-term memory storage, and language, supporting the integrative nature of intelligence [28].

The distributed nature of the frontoparietal network and its involvement in diverse cognitive functions aligns well with the integrative nature of intelligence. Current research is investigating how functional networks relate to structural networks, with particular emphasis on how distributed brain areas communicate with each other [28]. This communication efficiency between network nodes appears fundamental to intelligent behavior.

Spatial Distribution of Functional Connectivity Variability

Individual differences in functional connectivity are heterogeneously distributed across the cortex. Research demonstrates significantly higher variability in heteromodal association cortex (including lateral prefrontal cortex and temporal-parietal junction) and lower variability in unimodal cortices (primary sensory and motor regions) [27].

Table 1: Functional Connectivity Variability Across Brain Networks

| Brain Network | Relative Variability Level | Primary Cognitive Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Frontoparietal Control Network | High | Executive control, complex reasoning |

| Attentional Networks | High | Attention allocation, salience detection |

| Default Mode Network | Moderate | Self-referential thought, mentalizing |

| Sensory-Motor Networks | Low | Basic sensory processing, motor execution |

| Visual Networks | Low | Visual perception |

This variability distribution has significant implications for understanding which neural systems are most likely to relate to individual differences in complex cognition. Regions with higher functional connectivity variability appear more specialized for supporting individualized cognitive styles and capabilities.

Evolutionary and Developmental Perspectives

Functional connectivity variability shows a remarkable correlation with evolutionary cortical expansion. Comparative studies between macaque and human cortices reveal that regions with the highest functional variability in humans correspond to phylogenetically late-developing regions that are essential to human-specific cognitive functions like reasoning and language [27]. The correlation between functional variability and evolutionary cortical expansion is significant (r=0.52, p<0.0001) [27], suggesting an evolutionary root for functional variability in human cognition.

From a developmental perspective, structural variability of association cortex is less influenced by genetic factors, allowing greater impact from postnatal environmental factors that lead to diversity of neural connections beyond genetic determination [27]. This developmental plasticity in high-variability regions may support the adaptive nature of human cognition.

Quantitative Evidence: Network Variability and Cognitive Performance

Intelligence and Frontoparietal Network Organization

General mental ability (intelligence) reliably predicts broad social outcomes including educational achievement, job performance, health, and longevity [28]. The neurobiological basis for these relationships appears to reside in the efficiency of frontoparietal network functioning.

Research examining the neural correlates of intelligence has consistently identified the frontoparietal network as crucial. This network demonstrates several characteristics relevant to intelligence:

- Integrative Capacity: The frontoparietal network integrates information from multiple cognitive domains including perception, memory, and language [28]

- Flexible Hub Properties: This network can dynamically reconfigure based on task demands

- Individual Differences: The functional organization of this network varies substantially across individuals

A meta-analysis of studies investigating individual differences in cognitive domains revealed that approximately 73% of clusters identifying cognitive performance correlates are located in regions of high functional connectivity variability [27]. This strong overlap demonstrates that variable regions are disproportionately associated with individual cognitive differences.

Mentalizing and Default Mode Network Dynamics

Mentalizing (theory of mind) capabilities show distinct neural correlates, primarily within the default mode network (DMN) and related social cognitive networks. Research on mind wandering (a related phenomenon) provides insights into how network dynamics support internally-directed cognition.

Studies dividing subjects based on dispositional mind wandering tendencies (using the Mind Wandering Questionnaire) have found distinct patterns of functional connectivity in both the DMN and other networks [13]. Specifically:

- High mind wandering is associated with decreased synchronization within the DMN in lower frequencies (delta and theta bands) [13]

- High mind wandering is linked to strengthened connectivity within sensory-motor networks [13]

- High mind wandering correlates with increased connectivity in the cingulo-opercular network in the gamma frequency [13]

These findings suggest that individual differences in mentalizing and self-referential thought are reflected in characteristic patterns of within-network and between-network connectivity.

Table 2: Network Connectivity Patterns Associated with High Mentalizing/Mind Wandering

| Network | Frequency Band | Connectivity Change | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Default Mode Network | Delta/Theta | Decreased | Reduced low-frequency synchronization |

| Sensory-Motor Network | Multiple bands | Increased | Enhanced sensory processing |

| Cingulo-Opercular Network | Gamma | Increased | Enhanced cognitive control integration |

Stimulus-Driven Variability Reduction

A fundamental characteristic of flexible cognitive systems is their ability to reduce variability when processing relevant stimuli. Neural network modeling demonstrates how external stimulation stabilizes specific attractor states, reducing neural variability across trials [29].

In spontaneous activity, high neural variability arises from noise-driven excursions between multiple attractor states. When an external stimulus is applied, the network stabilizes into a specific attractor, suppressing transitions between states and reducing neural variability [29]. This variability reduction is associated with:

- Increased firing regularity as measured by the coefficient of variation of interspike intervals

- Stabilization of network dynamics around behaviorally-relevant states

- Enhanced information encoding through reduced noise

This mechanism provides a computational basis for understanding how brain networks support both stable cognitive representations and flexible responses to environmental demands.

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Assessing Functional Connectivity Variability

The gold standard for investigating network variability involves repeated-measurement resting-state functional MRI to quantify inter-subject variability in connectivity while controlling for measurement instability based on intra-subject variance [27]. The following protocol details this approach:

Experimental Protocol 1: Resting-State fMRI for Connectivity Variability

- Participant Requirements: 20+ participants, each scanned 3-5 times over several months to account for intra-subject variance

- Data Acquisition:

- MRI Parameters: T2*-sensitive EPI sequence for BOLD contrast

- Resting-State Duration: 8-10 minutes with eyes open or closed

- Spatial Resolution: 2-3mm isotropic voxels

- Temporal Resolution: TR=2-2.5 seconds

- Preprocessing Pipeline:

- Slice timing correction and head motion realignment

- Registration to structural images and standard space (MNI)

- Nuisance regression (white matter, CSF, global signal)

- Bandpass filtering (0.01-0.1 Hz)

- Scrubbing of motion-contaminated volumes

- Functional Connectivity Calculation:

- Parcellate cortex using standardized atlas (e.g., Yeo 7-network)

- Extract mean BOLD time series for each region

- Compute correlation matrices between all regions

- Apply Fisher's z-transform to correlation coefficients

- Variability Quantification:

- Calculate inter-subject variance at each connection

- Control for intra-subject variance using repeated measures

- Normalize variability measures for cross-region comparison

EEG Approaches to Network Organization

Electroencephalography (EEG) provides complementary information about network dynamics with high temporal resolution, particularly valuable for studying mentalizing-related phenomena.

Experimental Protocol 2: Source-Space EEG for Network Dynamics

- Participant Requirements: 40+ participants to ensure statistical power for group comparisons

- Data Acquisition:

- EEG System: 64+ channel systems recommended

- Sampling Rate: ≥500 Hz

- Impedance: Kept below 5 kΩ

- Resting-State Recording: 5 minutes eyes open, 5 minutes eyes closed

- Preprocessing:

- Filtering: 0.5-70 Hz bandpass, 50/60 Hz notch filter

- Bad channel identification and interpolation

- Independent Component Analysis for artifact removal

- Epoching into 2-second segments

- Source Reconstruction:

- Create head model using individual or template MRI

- Solve inverse problem using eLORETA or beamforming

- Extract time series from regions of interest

- Functional Connectivity Analysis:

- Calculate Phase Locking Value (PLV) between regions

- Analyze in standard frequency bands (delta, theta, alpha, beta, gamma)

- Compare connectivity matrices between groups

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for multimodal network variability research

Analytical Frameworks for Network Neuroscience

Independent Component Analysis (ICA) for Network Identification

Independent Component Analysis is a data-driven approach that decomposes fMRI signals into independent spatial components corresponding to functional networks [26]. This method is particularly valuable for identifying resting-state networks without a priori seed selection.

Key Considerations for ICA:

- Model Order Selection: Typically 20-30 components for standard fMRI data

- Network Identification: 8-13 components typically correspond to recognizable RSNs

- Artifact Separation: Non-neural components (motion, physiological noise) can be identified and removed

- Group Analysis: Dual regression approaches allow for group-level comparisons

ICA has been successfully applied to identify network alterations in neurodegenerative conditions and individual differences in cognitive performance [26].

Graph Theoretical Methods for Whole-Brain Characterization

Graph theory provides a quantitative framework for characterizing whole-brain functional connectivity as a complex network [26]. This approach represents brain regions as nodes and functional connections as edges, enabling computation of topological metrics.

Table 3: Key Graph Theory Metrics for Brain Network Analysis

| Metric | Description | Cognitive Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Global Efficiency | Average inverse shortest path length | Overall information integration capacity |

| Modularity | Degree of network subdivision into communities | Functional specialization and segregation |

| Clustering Coefficient | Density of local connections | Local information processing capacity |

| Betweenness Centrality | Fraction of shortest paths passing through a node | Hub status and integrative importance |

| Small-Worldness | Balance of local clustering and global integration | Optimal network organization |

These metrics provide quantitative descriptors of individual differences in brain network organization that correlate with cognitive abilities including intelligence and mentalizing.

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for Network Variability Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Platforms | 3T fMRI with multiband sequences, High-density EEG systems (64+ channels), fNIRS systems (NIRx) [30] | Data acquisition for functional connectivity |

| Analysis Software | FSL (FMRIB Software Library), FreeSurfer, EEGLAB, CONN toolbox, Brainstorm | Data preprocessing and connectivity analysis |

| Computational Modeling | The Virtual Brain, BRAPH, Brain Dynamics Toolbox | Simulation of network dynamics and variability |

| Cognitive Assessment | Mind Wandering Questionnaire (MWQ) [13], Raven's Progressive Matrices, Theory of Mind tasks | Quantification of individual differences in cognition |

| Data Management | BIDS (Brain Imaging Data Structure), COINS, XNAT | Standardization and sharing of neuroimaging data |

Diagram 2: Neural network model of stimulus-driven variability reduction

Implications for Drug Development and Therapeutic Innovation

Understanding individual differences in network variability has profound implications for pharmaceutical research and development. The framework presented herein offers:

- Novel Biomarkers: Individual patterns of network variability may serve as biomarkers for cognitive-enhancing compounds

- Target Identification: Network hubs with high variability represent potential targets for neurotherapeutics

- Personalized Medicine Approaches: Accounting for individual network architecture may optimize treatment outcomes

- Clinical Trial Design: Network-based stratification may enhance participant selection and endpoint measurement

Research examining network correlates of cognitive decline in neurodegenerative conditions has demonstrated the clinical relevance of these approaches [26]. Similar frameworks can be applied to development of compounds targeting cognitive enhancement in healthy populations or those with neuropsychiatric conditions.

The evidence synthesized in this whitepaper supports a network-based understanding of individual cognitive differences. Intelligence and mentalizing capabilities emerge from characteristic patterns of functional network variability, particularly in heteromodal association cortices that have undergone significant evolutionary expansion. The frontoparietal network supports general intelligence through its integrative capacity, while the default mode network and related systems underpin mentalizing capabilities.

Future research should prioritize:

- Longitudinal studies examining network development and cognitive trajectories

- Multi-modal integration of fMRI, EEG, and fNIRS approaches [30] [13]

- Computational modeling of network dynamics underlying cognitive performance

- Pharmacological manipulation of network variability and cognitive outcomes

This intrinsic functional network neuroscience framework provides a powerful approach for understanding the biological basis of individual cognitive differences, with significant implications for basic research and applied pharmaceutical development.

Connecting Network Architecture to Social and Emotional Functioning

The emerging field of network neuroscience provides a powerful framework for understanding the neurobiological underpinnings of individual differences in social, emotional, and cognitive functioning [31]. Rather than mapping psychological processes to isolated brain regions, this approach conceptualizes the brain as a complex system of interconnected neural networks. Research demonstrates that an individual's unique pattern of static and dynamic functional connectivity—the temporal synchronization of neuronal firing across distinct brain regions—significantly influences how they perceive, emotionally respond to, and navigate social situations [31]. This technical guide synthesizes current methodologies and findings, framing them within the broader thesis of intrinsic functional network neuroscience individual differences research, to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive toolkit for investigating these relationships.

Core Intrinsic Functional Network Architectures

Intrinsic functional networks are identified from brain activity measured during rest or task performance using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) [31]. These networks serve as the fundamental architectural units upon which cognitive, social, and emotional processes are built. Static functional connectivity analysis assumes a single, stable network configuration across an experimental session, while dynamic functional connectivity captures temporal fluctuations and reconfigurations in these networks [31]. The following table summarizes key intrinsic networks and their primary functional associations relevant to social and emotional functioning.

Table 1: Key Intrinsic Connectivity Networks and Their Functional Correlates

| Network Name | Core Brain Regions | Primary Functional Roles | Links to Social & Emotional Functioning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Default Mode Network (DMN) | Medial Prefrontal Cortex, Posterior Cingulate, Precuneus, Angular Gyrus | Self-referential thought, mentalizing, autobiographical memory | Understanding others' mental states, empathy, social reasoning [31] |

| Salience Network (SN) | Anterior Cingulate, Anterior Insula | Detecting behaviorally relevant stimuli, switching between networks | Interoceptive awareness, emotional sensitivity, guiding social behavior [6] |

| Central Executive Network (CEN) | Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex, Posterior Parietal Cortex | Goal-directed cognition, working memory, decision-making | Social working memory, regulating emotional responses [31] |

| Triple Network Model | DMN, SN, and CEN collectively | Integrative information processing across systems | Dysfunction implicated in psychiatric disorders; SN mediates DMN-CEN interaction [6] |

Advanced decomposition techniques like high-order independent component analysis (ICA) have enabled the identification of finer-grained subnetworks within these large-scale systems. For instance, applying group-level ICA with 500 components to over 100,000 subjects reveals highly specific subcomponents within cerebellar and paralimbic regions, offering enhanced granularity for detecting subtle, clinically relevant connectivity differences [6].

Quantitative Data on Network Connectivity and Individual Differences

The relationship between network properties and behavioral phenotypes can be quantified using various connectivity metrics. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings linking network characteristics to individual differences in social and emotional functioning.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics of Functional Connectivity and Associated Individual Differences

| Quantitative Metric | Experimental Paradigm | Key Findings | Implications for Social/Emotional Functioning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Within-Network Connectivity (WNC) | Resting-state fMRI, Voxel-based Global Brain Connectivity (GBC) | Both phonological and semantic networks show stronger intra-network connectivity than inter-network connectivity, indicating network encapsulation [32]. | Stronger integration within specific networks (e.g., SN) may predict more accurate emotion detection or social cue perception. |

| Between-Network Connectivity (BNC) | Resting-state fMRI, Functional Network Connectivity (FNC) | Dynamic analyses reveal distinct brain states: State 1 (overall positive connectivity), State 2 (weak connectivity), State 3 (positive intra-network/negative inter-network) [32]. | The flexibility of network segregation/integration over time influences executive function, attention, and emotional regulation [31]. |

| Hypo-/Hyper-connectivity | Case-Control Studies (e.g., Schizophrenia) | In schizophrenia: hypoconnectivity between cerebellar and subcortical domains; hyperconnectivity between cerebellar and sensorimotor/cognitive domains [6]. | Dysconnectivity patterns manifest as negative symptoms (social withdrawal) and disorganized social behavior. |

| Pairwise Connectivity Strength | Seed-based Correlation, Psychophysiological Interaction | Individual differences in emotion regulation correlate with amygdala-prefrontal cortex coupling; stronger negative coupling linked to better down-regulation of negative emotions [31]. | Provides a specific, quantifiable neural target for interventions aimed at improving emotional control. |

Experimental Protocols for Network Neuroscience Research

Reproducible experimental protocols are fundamental for advancing the field. This section outlines detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this guide.

Protocol: Static and Dynamic Functional Connectivity Analysis from Resting-State fMRI

This protocol details the process for identifying both static and dynamic intrinsic functional connectivity patterns, as applied in studies of language and cognitive networks [32].

- Objective: To identify the static and dynamic functional connectivity patterns of intrinsic brain networks (e.g., phonological and semantic networks) during the resting state.

- Materials and Equipment:

- MRI Scanner: A 3T (or higher) MRI system equipped with a standard head coil.

- Stimulus Presentation System: For task-based fMRI (if applicable); for resting-state, a fixation cross is typically displayed.

- Computational Hardware: High-performance computing cluster with sufficient RAM and CPU cores for large-scale data processing.

- Software: fMRI preprocessing software (e.g., SPM, FSL, AFNI); functional connectivity toolbox (e.g., CONN, DPABI); and custom scripts for dynamic analysis (e.g., in MATLAB or Python).

- Data Acquisition:

- Imaging Parameters: Acquire T2*-weighted echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequences. Key parameters: TR/TE = 2000/30 ms, flip angle = 90°, field of view = 220 mm, matrix size = 64×64, voxel size = 3.4×3.4×3.0 mm³, 120-140 time points (volumes).

- Subject Instruction: Instruct participants to lie still with their eyes open, focus on a fixation cross, and not think of anything in particular.

- Quality Control (QC): Ensure mean framewise displacement is < 0.25 mm, and head motion is limited to < 3° rotation and < 3 mm translation. Registration to an EPI template must be high-quality, with >80% spatial overlap with a group mask [6].

- Data Preprocessing Workflow:

- Discard Initial Volumes: Remove the first 4-10 volumes to allow for magnetic field stabilization.

- Slice Timing Correction: Correct for differences in acquisition time between slices.

- Realignment: Correct for head motion using a six-parameter rigid body transformation.

- Coregistration: Align the functional data with the participant's high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical image.

- Normalization: Spatially normalize the functional and anatomical images to a standard stereotaxic space (e.g., MNI152).

- Spatial Smoothing: Apply a Gaussian kernel (e.g., 6-8 mm FWHM) to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

- Functional Connectivity Analysis:

- Static Functional Connectivity (sFC):

- Define Networks: Extract time courses from pre-defined regions of interest (ROIs) or intrinsic connectivity networks (ICNs) derived from ICA.

- Compute Correlation Matrices: Calculate Pearson's correlation coefficients between the time courses of all network pairs to create a full correlation matrix.

- Within- vs. Between-Network Analysis: Use voxel-based global brain connectivity (GBC) to examine within-network connectivity (WNC) and between-network connectivity (BNC) with other language and non-language networks [32].

- Dynamic Functional Connectivity (dFC):

- Temporal Segmentation: Use a sliding window approach to calculate connectivity matrices over short, overlapping time segments throughout the scan session.

- Cluster Analysis: Apply clustering algorithms (e.g., k-means) to the resulting time-varying connectivity matrices to identify a finite set of reoccurring brain states [32].

- State Characterization: Quantify the properties of each state, such as frequency of occurrence, dwell time, and transition probabilities.

- Static Functional Connectivity (sFC):

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for intrinsic functional connectivity analysis.

Protocol: High-Order Independent Component Analysis (ICA) for Fine-Grained ICNs

This protocol describes the application of very high-order ICA to large-scale datasets to generate robust, fine-grained intrinsic connectivity network (ICN) templates, as used in the NeuroMark-fMRI-500 template [6].

- Objective: To derive a robust, fine-grained template of intrinsic connectivity networks (ICNs) from large-scale resting-state fMRI data using very high-order group independent component analysis (sgr-ICA).

- Materials and Equipment:

- Dataset: Resting-state fMRI data from a large cohort (e.g., n > 10,000 subjects from multiple sites to ensure robustness and generalizability).

- Computational Hardware: High-performance computing cluster with substantial memory and storage.

- Software: ICA software package (e.g., GIFT, MELODIC).

- Data Preparation:

- Data Aggregation and Harmonization: Collect rsfMRI datasets from multiple sources. Address inter-site variability through consistent preprocessing and quality control pipelines [6].

- Preprocessing: Apply standard preprocessing steps as in Protocol 4.1.

- Group-Level ICA Decomposition:

- Data Reduction: Perform principal component analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction at the subject and group levels.

- ICA Estimation: Apply the infomax algorithm for sgr-ICA at a very high model order (e.g., 500 components).

- Back-Reconstruction: Use the GICA method to reconstruct individual subject components from the group-level spatial maps.

- Component Identification and Labeling:

- Spatial Sorting: Correlate the resulting components with established functional atlases to identify known networks (e.g., DMN, SN, CEN) and their subcomponents.

- Reliability Assessment: Evaluate the reliability and replicability of the fine-grained ICNs across sub-samples or independent datasets.

- Template Creation: Organize and label the reliable ICNs to create a fine-grained functional atlas (e.g., NeuroMark-fMRI-500).

- Downstream Analysis:

- Functional Network Connectivity (FNC): Calculate the pairwise temporal correlations between the time courses of the identified ICNs.

- Group Comparison: Compare FNC matrices between clinical populations (e.g., schizophrenia) and typical controls to identify disease-related dysconnectivity patterns [6].

Figure 2: High-order ICA workflow for fine-grained network identification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

This section details essential computational tools, data resources, and analytical approaches that constitute the core "research reagent solutions" in network neuroscience individual differences research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Network Neuroscience

| Reagent/Material | Specifications / Version | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| High-Order ICA Templates | NeuroMark-fMRI-500 [6] | Provides a robust, pre-defined set of fine-grained intrinsic connectivity networks for use as functional regions of interest, enhancing consistency and granularity across studies. |

| Functional Connectivity Toolboxes | CONN, DPABI, GIFT | Integrated software suites for preprocessing fMRI data and calculating static and dynamic functional connectivity metrics. |

| Dynamic Connectivity Algorithms | Sliding Window, k-means Clustering | Custom scripts and algorithms to identify and characterize time-varying brain states from fMRI time series data [32]. |

| Large-Scale Neuroimaging Datasets | UK Biobank, ADHD-200, ABIDE | Publicly available datasets with resting-state fMRI and behavioral data from thousands of subjects, enabling highly powered analyses of individual differences. |

| Quality Control Metrics | Framewise Displacement (FD) < 0.25mm [6] | Quantitative criteria to exclude datasets with excessive motion, ensuring that observed connectivity effects are neural in origin and not motion artifacts. |

Diagram: The Triple Network Model in Social-Emotional Functioning

The Triple Network Model, comprising the Salience Network (SN), Central Executive Network (CEN), and Default Mode Network (DMN), offers a parsimonious framework for understanding higher-order cognition and its disruption in psychiatric conditions [6]. The following diagram illustrates the typical and dysregulated interactions between these networks.

Figure 3: Triple Network Model: Typical and Dysregulated States.

The Role of High-Level Association Areas in Generating Behavioral Uniqueness

High-level association areas of the cerebral cortex serve as the neural cornerstone for individual differences in complex behavior and cognition. This whitepaper elucidates how the parieto-occipitotemporal, prefrontal, and limbic association areas generate behavioral uniqueness through their specialized roles in sensory integration, executive planning, and emotional processing. Framed within intrinsic functional network neuroscience (ifNN), we present evidence that individual variability in behavior is predicated on stable, individualized patterns of resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) within and between large-scale brain networks. The synthesis of ifNN research, advanced analytical protocols, and cross-species findings provides a transformative framework for identifying novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets in neuropsychiatric drug development.

The cerebral cortex extends beyond primary motor and sensory regions to include high-level association areas that integrate information from multiple sensory modalities, memory stores, and internal states to generate coherent thought and behavior. These areas are termed "association areas" precisely because they receive and analyze signals simultaneously from multiple regions of both the motor and sensory cortices as well as from subcortical structures [33]. Modern ifNN research has demonstrated that these areas do not operate in isolation but are organized into intrinsically connected, large-scale networks that exhibit coherent, spontaneous activity even during rest. The organization of these intrinsic networks provides a neural fingerprint that accounts for inter-individual variability in behavioral propensities, from social decision-making to cognitive control [1] [3].

Functional Specialization of Major Association Areas

The association cortex is broadly categorized into three major regions, each with distinct functional specializations that collectively contribute to behavioral uniqueness.

Table 1: Functional Specialization of Major Association Areas

| Association Area | Key Subregions/Functions | Contribution to Behavioral Uniqueness |

|---|---|---|

| Parieto-occipitotemporal | Analysis of spatial coordinates; Language comprehension (Wernicke's area); Initial processing of visual language; Naming objects [33] | Enables unique cognitive strengths in spatial reasoning, linguistic ability, and conceptual integration. |

| Prefrontal | Planning complex motor patterns; Executive function & working memory; Broca's area (word formation) [33] | Underlies individual differences in planning, decision-making, cognitive control, and linguistic expression. |

| Limbic | Behavior, emotions, and motivation [33]; Face recognition [33] | Generates uniqueness in emotional responsiveness, social motivation, and interpersonal recognition. |

Parieto-occipitotemporal Association Area

This area provides a high level of interpretative meaning for signals from all surrounding sensory areas. Its key sub-functions include:

- Analysis of Spatial Coordinates: An area beginning in the posterior parietal cortex provides continuous analysis of the spatial coordinates of all parts of the body and its surroundings [33].

- Language Comprehension: Wernicke's area, located in the posterior superior temporal gyrus, is the most important region for language comprehension and higher intellectual function [33].

- Face Recognition: Damage to the medioventral surfaces of the occipital and temporal lobes can cause prosopagnosia, suggesting this region is specialized for the socially critical task of face recognition [33].

Prefrontal Association Area

The prefrontal association area functions in close association with the motor cortex to plan complex patterns and sequences of motor movements. It is essential for carrying out "thought" processes and is frequently described as important for the elaboration of thoughts, storing "working memories" on a short-term basis [33]. A special region, Broca's area, provides the neural circuitry for word formation [33].

Limbic Association Area

Found in the anterior pole of the temporal lobe and the cingulate gyrus, this area is concerned primarily with behavior, emotions, and motivation [33]. It provides most of the emotional drives for activating other areas of the brain and provides motivational drive for the process of learning.

ifNN and Individual Differences: Linking Intrinsic Networks to Behavior