Gene Therapies vs. RNA-Based Treatments for Neurological Disorders: A Comparative Analysis for Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on two revolutionary therapeutic classes for neurological disorders: gene therapies and RNA-based treatments.

Gene Therapies vs. RNA-Based Treatments for Neurological Disorders: A Comparative Analysis for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on two revolutionary therapeutic classes for neurological disorders: gene therapies and RNA-based treatments. It explores their foundational mechanisms, from gene replacement with viral vectors to precise RNA-level modulation using ASOs and siRNAs. The scope covers key methodological applications across neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative diseases, critically examines troubleshooting for central nervous system delivery and safety, and offers a direct validation of clinical efficacy, development timelines, and suitability for different genetic pathologies. The synthesis aims to inform strategic therapeutic development and clinical translation in the evolving landscape of neurological treatments.

Core Mechanisms: Defining Gene and RNA-Based Therapeutic Platforms

The advent of molecular therapies has ushered in a new era for treating neurological disorders of genetic origin. Within this therapeutic landscape, two distinct strategies have emerged: gene replacement therapy, which introduces a functional copy of a gene to compensate for a defective one, and transcript modulation therapy, which targets the RNA messengers to alter gene expression without changing the underlying DNA sequence. Gene replacement represents a permanent solution aimed at addressing the root cause of genetic disorders, particularly those involving loss-of-function mutations. In contrast, transcript modulation offers a reversible, tunable approach capable of targeting gain-of-function mutations and splicing defects that are inaccessible to traditional gene replacement. The selection between these paradigms depends on multiple factors including the nature of the genetic defect, target tissue accessibility, and desired duration of therapeutic effect. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of these foundational approaches, examining their mechanisms, applications, and experimental validation within neurological disease research.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies

Gene Replacement: Restoring Function through DNA-Based Approaches

Gene replacement therapy operates on a straightforward principle: delivering a functional copy of a gene to compensate for a mutated, non-functional version. This approach is particularly suited for recessive disorders caused by loss-of-function mutations where simply adding a correct gene copy can restore protein production [1]. The process involves packaging the therapeutic gene into a delivery vector, most commonly adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), which efficiently transport the genetic material to the nucleus of target cells where it remains as an episomal element without integrating into the host genome [2].

The pioneering success of this approach in neurological disorders is exemplified by voretigene neparvovec (Luxturna), an AAV2-mediated gene replacement therapy for Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) caused by biallelic mutations in RPE65 [2]. This treatment delivers the wild-type cDNA of the RPE65 gene, critical for the visual cycle, and has demonstrated significant improvement in visual function. Similarly, onasemnogene abeparvovec (Zolgensma) delivers a functional copy of the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene using AAV9 for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a devastating neuromuscular disease [2].

Despite its conceptual simplicity, gene replacement faces significant constraints. AAV vectors have a limited packaging capacity of approximately 4.8 kb, excluding larger genes such as ABC4A and MYO7A from this therapeutic approach [2]. Additionally, the need for specific promoters to direct expression to target cell types, potential immune responses against the viral capsid or transgene product, and the irreversibility of treatment present challenges for clinical application [1].

Transcript Modulation: Precision Manipulation at the RNA Level

Transcript modulation encompasses diverse strategies that target RNA molecules to alter gene expression, including antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), RNA interference (RNAi), and mRNA-based therapies. These approaches operate further downstream in the central dogma, providing nuanced control over gene expression without altering the foundational genetic code [1].

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are synthetic, short single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules that modulate RNA function through complementary base pairing [1] [2]. They can correct splicing defects, degrade mutant mRNA, or block translation. Their versatility is demonstrated in neurological disorders such as spinal muscular atrophy, where nusinersen (Spinraza), an ASO, modulates the splicing of SMN2 to increase production of functional SMN protein [3].

Therapeutic mRNA represents another transcript modulation strategy, introducing chemically modified mRNA encoding functional proteins into target cells [1]. This approach is particularly valuable for haploinsufficiency disorders, transiently expressing the needed protein without genomic integration. Modifications to the 5' cap, untranslated regions (UTRs), and poly(A) tail enhance mRNA stability and translatability, while incorporating modified nucleotides reduces immune recognition [1].

RNA interference utilizes small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) to selectively degrade complementary mRNA sequences, offering potent silencing of genes carrying toxic gain-of-function mutations [3]. This approach is especially relevant for dominantly inherited disorders where suppressing expression of the mutant allele is therapeutic.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Therapeutic Approaches

| Feature | Gene Replacement | Transcript Modulation |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Target | DNA | RNA |

| Therapeutic Scope | Primarily loss-of-function mutations | Loss-of-function, gain-of-function, and splicing defects |

| Duration of Effect | Long-lasting to permanent | Transient, requiring repeated administration |

| Delivery Vehicles | AAV, lentivirus | ASOs: chemical modifications; mRNA: LNPs, AAV |

| Packaging Constraints | Limited to ~4.8 kb for AAV | More flexible for large genes |

| Immunogenicity | Immune response against viral capsid | Immune response against nucleic acids |

| Regulatory Precedents | Luxturna, Zolgensma | Spinraza, Formivirsen, Mipomersen |

Experimental Data and Comparative Performance

Efficiency and Precision in Preclinical Models

Direct comparisons of gene editing platforms reveal distinct efficiency and precision profiles. CRISPR-Cas systems demonstrate significant advantages in simplicity and cost-effectiveness over traditional methods like ZFNs and TALENs, with CRISPR requiring only guide RNA redesign versus extensive protein engineering for ZFNs/TALENs [4]. However, quantitative analysis shows that traditional methods may offer superior specificity in certain contexts, with better validation reducing off-target risks [4].

In the realm of transcript modulation, ASOs have demonstrated remarkable precision in correcting splicing defects. For CEP290-associated LCA10, ASO treatment successfully restored normal splicing patterns in preclinical models, leading to functional protein expression [2]. Similarly, mRNA-based therapies have achieved therapeutic protein levels in vivo with reduced immunogenicity through nucleoside modifications, enabling repeated administration where necessary [1].

Delivery and Biodistribution Challenges

Both therapeutic paradigms face significant delivery challenges, particularly for neurological applications where the blood-brain barrier presents a formidable obstacle. Gene replacement therapies predominantly rely on viral vectors, with AAV serotypes selected for their tropism to specific neural cell types [2]. Direct intracranial injection often bypasses the blood-brain barrier, enabling precise targeting of affected brain regions while minimizing systemic exposure [3].

Transcript modulation therapies employ distinct delivery strategies. ASOs can be administered directly into the cerebrospinal fluid, allowing broad distribution throughout the central nervous system [3]. mRNA therapies require protective carriers such as lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) or viral vectors to preserve integrity during trafficking and enhance cellular uptake [1]. Chemical modifications to ASOs, including phosphorothioate backbones and 2'-sugar modifications, significantly improve their stability, pharmacokinetics, and tissue penetration [1].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Editing Platforms

| Feature | CRISPR | ZFNs | TALENs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Moderate to high; subject to off-target effects | High; better validation reduces risks | High; better validation reduces risks |

| Ease of Use | Simple gRNA design | Requires extensive protein engineering | Challenging to scale due to labor-intensive assembly |

| Cost | Low | High | High |

| Scalability | High; ideal for high-throughput experiments | Limited | Limited |

| Applications | Broad (therapeutics, agriculture, research) | Niche (e.g., stable cell line generation) | Niche (e.g., small-scale precision edits) |

| Delivery Methods | Compatible with viral vectors, nanoparticles | Primarily relies on plasmid vectors | Primarily relies on plasmid vectors |

Experimental Protocols for Therapeutic Validation

Protocol: Validating Gene Replacement Efficacy in vivo

Objective: To evaluate the functional recovery following gene replacement therapy in a murine model of RPE65-associated Leber congenital amaurosis.

Materials:

- RPE65-deficient mice

- AAV2 vectors containing human RPE65 cDNA under control of a specific promoter

- Control AAV2 vectors with scrambled sequence

- Electroretinography (ERG) equipment

- Immunohistochemistry supplies

Methodology:

- Vector Administration: Administer 1µL of AAV2-RPE65 (1×10¹² vg/mL) via subretinal injection to 6-week-old RPE65-/- mice under anesthesia. Control groups receive AAV2-scrambled or sham injection.

- Functional Assessment: At 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-injection, perform ERG under scotopic and photopic conditions to measure retinal function recovery.

- Tissue Analysis: Euthanize animals at 12 weeks, harvest retinal tissues, and process for immunohistochemistry using anti-RPE65 antibodies to confirm protein expression.

- Quantitative PCR: Isolve RNA from retinal tissues and perform qPCR with RPE65-specific primers to quantify transcript levels.

Validation Parameters: Significant improvement in ERG amplitudes in treated versus control groups, with correlation between RPE65 expression levels and functional recovery [2].

Protocol: Assessing Transcript Modulation Using ASOs

Objective: To determine the efficacy of ASOs in correcting splicing defects in CEP290-associated models.

Materials:

- Fibroblasts from patients with CEP290 splicing mutations

- Control fibroblasts from healthy donors

- CEP290-targeting ASOs with 2'-O-methoxyethyl modifications

- Scrambled control oligonucleotides

- RT-PCR reagents

- Western blot equipment

Methodology:

- Cell Culture: Maintain fibroblasts in DMEM with 10% FBS at 37°C in 5% CO₂.

- ASO Transfection: Transfect 100nM of CEP290 ASOs or scrambled controls using lipofectamine 3000 according to manufacturer's protocol.

- RNA Analysis: At 48 hours post-transfection, isolate total RNA and perform RT-PCR using CEP290-flanking primers to visualize splicing patterns.

- Protein Analysis: At 72 hours, lyse cells and perform western blotting with anti-CEP290 antibodies to quantify protein restoration.

- Functional Assay: Assess ciliogenesis and ciliary protein localization via immunofluorescence as CEP290 is essential for ciliary function.

Validation Parameters: Normalization of splicing patterns on gel electrophoresis, increased CEP290 protein expression, and restoration of normal ciliary morphology in ASO-treated versus control cells [2].

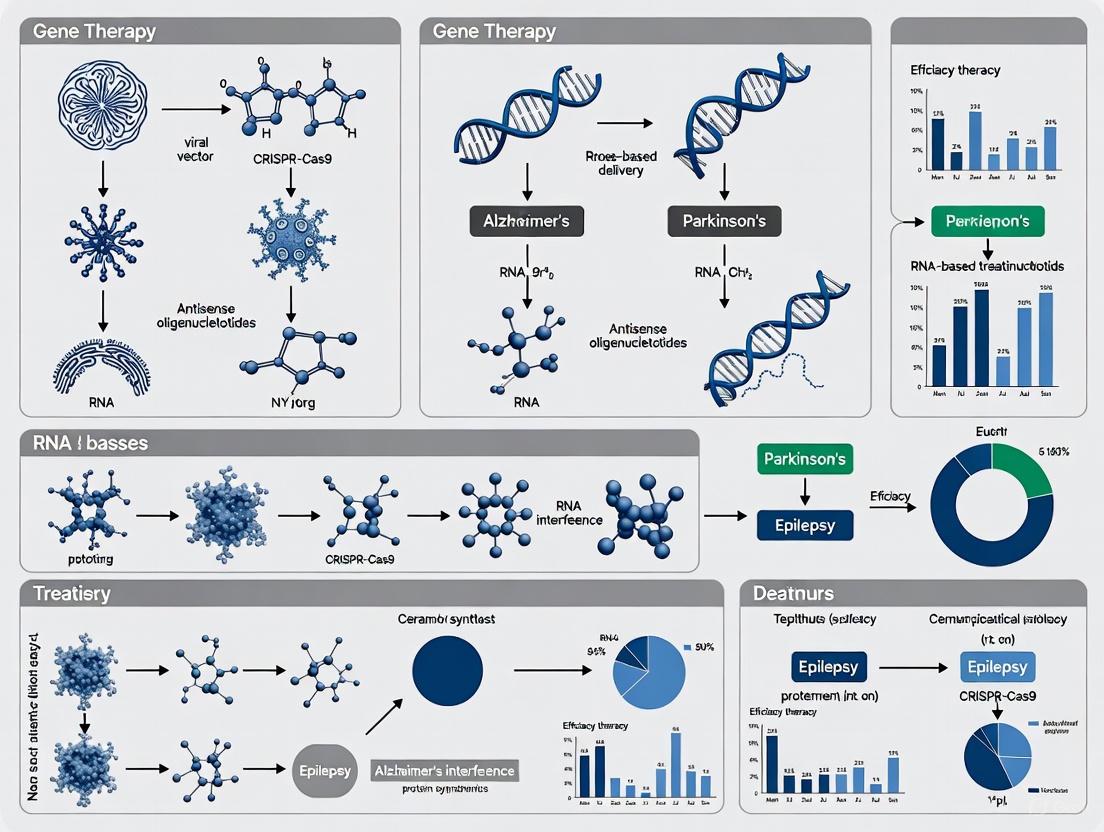

Visualization of Therapeutic Mechanisms

Gene Replacement Mechanism

Transcript Modulation Mechanisms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Gene Therapy Development

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, ZFNs, TALENs, Base Editors | Targeted genomic modifications for functional studies |

| Delivery Vectors | AAV serotypes (AAV2, AAV9), Lentivirus, Lipid Nanoparticles | Therapeutic nucleic acid delivery to target cells |

| Transcript Modulators | ASOs, siRNA, shRNA, mRNA | Targeted gene expression regulation without genomic alteration |

| Cell Culture Models | Patient-derived fibroblasts, iPSC-derived neurons, Organoids | Disease modeling and therapeutic screening |

| Analytical Tools | qPCR, Western Blot, RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, Immunofluorescence | Molecular and functional validation of therapeutic effects |

| Animal Models | Genetic knockout mice, Xenograft models, Disease-specific mutants | In vivo efficacy and safety assessment |

Gene replacement and transcript modulation represent complementary rather than competing strategies in the therapeutic landscape for neurological disorders. The choice between these approaches depends fundamentally on the specific genetic alteration, with gene replacement offering durable solutions for loss-of-function disorders and transcript modulation providing flexible targeting of splicing defects and gain-of-function mutations. Emerging technologies such as base editing and prime editing are blurring the historical boundaries between these categories, enabling ever more precise genetic interventions.

Future developments will likely focus on enhancing delivery efficiency, particularly across the blood-brain barrier, reducing immunogenicity concerns, and expanding the range of targetable disorders. The integration of machine learning approaches, as exemplified by foundation models like GET (General Expression Transformer), promises to accelerate therapeutic design by predicting gene expression outcomes from sequence and chromatin accessibility data [5]. As both paradigms continue to mature, combination approaches may offer synergistic benefits, potentially addressing the complex genetics underlying many neurological disorders through multi-faceted intervention strategies.

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) has solidified its position as the premier viral vector for in vivo gene delivery, particularly for challenging targets like the central nervous system (CNS). Its exceptional safety profile, long-term transgene expression, and ability to infect non-dividing cells make it a cornerstone of modern gene therapy. This guide objectively compares AAV against alternative viral vectors and RNA-based therapies, providing structured experimental data and methodologies to inform research and drug development strategies. The analysis is framed within the broader thesis of selecting the optimal gene delivery platform for neurological disorders, a field being reshaped by advanced genetic medicines [6] [7].

The development of viral vectors has been instrumental in translating gene therapy from concept to clinical reality. Among the available options, AAV has emerged as a leader for in vivo applications. AAV is a small, non-pathogenic virus with a single-stranded DNA genome of approximately 4.7 kb, which can be engineered to deliver therapeutic transgenes [8] [9]. Its reputation as a "gold standard" is built on a combination of favorable characteristics: low immunogenicity, long-lasting episomal persistence in non-dividing cells, and the absence of association with any known human disease [9] [7]. The successful approval of AAV-based therapies like Zolgensma (onasemnogene abeparvovec) for spinal muscular atrophy has clinically validated this platform, demonstrating its potential to address profound unmet medical needs in neurological and other rare diseases [6] [8].

Comparative Analysis of Viral Vector Platforms

Selecting the appropriate viral vector requires a careful balance of payload capacity, duration of expression, safety, and immunogenicity. The table below provides a direct comparison of AAV against other commonly used viral vectors.

Table 1: Quantitative and Qualitative Comparison of Major Viral Vector Platforms

| Feature | Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) | Lentivirus (LV) | Adenovirus (AdV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Type | Single-stranded DNA | Single-stranded RNA (reverse-transcribing) | Double-stranded DNA |

| Packaging Capacity | ~4.7 kb [8] | ~8 kb [9] | Large, up to ~36 kb [9] |

| Integration Profile | Predominantly episomal; low risk of integration [7] | Integrates into host genome [9] | Non-integrating [9] |

| Duration of Expression | Long-term (years in post-mitotic cells) [7] | Long-term (due to integration) [9] | Transient (weeks to months) [9] |

| Immunogenicity | Low to moderate (capsid and transgene-specific) [9] [7] | Moderate | High; strong innate and adaptive immune response [9] |

| Primary Applications | In vivo gene therapy (CNS, retina, muscle), gene replacement | Ex vivo cell engineering (e.g., CAR-T), hematopoietic stem cells | Vaccines, oncolytic therapy, transient high-level expression [9] |

| Key Safety Considerations | Risk of hepatotoxicity at high systemic doses; pre-existing immunity [7] | Risk of insertional mutagenesis [9] | Inflammatory responses; toxicity from immune activation [9] |

AAV vs. RNA-Based Therapies for Neurological Disorders

The therapeutic strategy for neurological disorders often narrows to a choice between gene therapy (using vectors like AAV) and RNA-based treatments (such as RNA interference, or RNAi). While both aim to correct disease pathology, their mechanisms, capabilities, and limitations differ significantly.

Table 2: Comparison of AAV-Based Gene Therapy and RNAi-Based Therapy

| Aspect | AAV-Based Gene Therapy | RNAi-Based Therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Delivery of a functional gene to enable long-term production of a therapeutic protein (gene augmentation) [6] | Silencing of target genes at the mRNA level by degrading complementary mRNA transcripts (gene knockdown) [10] |

| Therapeutic Effect | Permanent or long-lasting correction (DNA level) [11] | Transient and reversible (mRNA level) [10] |

| Genetic Target | Can address loss-of-function and some gain-of-function diseases [6] | Primarily addresses gain-of-function or overexpressed genes [10] |

| Typical Dosing Regimen | Single or infrequent administration potential [11] | Often requires repeated administrations [10] |

| Specificity & Off-Target Effects | High specificity; off-target effects are a function of promoter choice and delivery. | Historically prone to high off-target effects due to sequence-independent interferon responses and seed-based hybridization [10] |

| Delivery to CNS | Multiple validated routes (intraparenchymal, intrathecal, intravenous with BBB-crossing serotypes) [6] [8] | Requires efficient delivery systems to cross the blood-brain barrier; can be coupled with AAV for sustained expression. |

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental mechanistic differences between AAV gene augmentation, RNAi knockdown, and the more recent CRISPR-Cas knockout, which can also be delivered by AAV.

The Emergence of AAV-CRISPR Synergy

A powerful extension of AAV's utility is its role in delivering clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-based gene-editing machinery. This combination allows for permanent gene correction, regulation, or knockout at the DNA level, going beyond traditional gene replacement [7]. CRISPR knockouts are highly effective for complete loss-of-function studies and, unlike RNAi, are not confounded by residual low-level protein expression [10]. A key challenge is the large size of the Cas nuclease, which exceeds AAV's packaging capacity. This is being overcome by innovative dual-vector, intein-split systems, where two co-administered AAVs deliver split parts of the editor that reconstitute inside the target cell [7]. Recent optimized systems have achieved therapeutically relevant editing efficiencies of 42% in the mouse brain [7].

Experimental Protocols and Supporting Data

Key Experimental Workflow for AAV Preclinical Studies

A standard protocol for evaluating an AAV-based gene therapy in a large animal model, as derived from a long-term safety and durability study, involves several critical stages [11].

Detailed Methodology:

- Vector & Dose: The study used an AAV9 vector encoding the canine sulfamidase gene (AAV9-Sgsh) under the control of a CAG promoter. A single, clinically relevant dose of 2 × 10^13 vector genomes (vg) per dog was administered [11].

- Administration: The vector was delivered via intracisterna magna (ICM) injection, a form of intra-cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) delivery, to achieve widespread CNS distribution [11].

- Safety Monitoring: Animals were monitored for 7 years. Periodic analyses included:

- Clinical and neurological evaluations.

- CSF analysis: White blood cell (WBC) count and total protein (TP) levels to monitor for neuroinflammation.

- Blood tests and imaging (MRI and ultrasound) of target organs [11].

- Efficacy/Durability Assessment: Sulfamidase enzyme activity was measured in the CSF over time. Upon terminal sacrifice, brain, spinal cord, and peripheral tissues were analyzed for vector genome persistence, transgene expression, and enzymatic activity [11].

Key Experimental Data from AAV Studies

Table 3: Summary of Key Findings from Preclinical and Clinical AAV Studies

| Study Model / Therapy | Key Parameter | Result / Data Point |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy Beagle Dogs (7-yr study) [11] | CSF Sulfamidase Activity | Detected at therapeutic levels for 7 years post-single AAV9-ICM injection |

| Clinical Safety | No treatment-related adverse events over 7 years; CSF WBC and TP largely within normal ranges | |

| Luxturna (AAV2-RPE65) Phase 3 Trial [8] | Functional Vision Improvement | >100-fold improvement in multi-luminance mobility test (MLMT) at 1 year vs control (p<0.001) |

| SRSD107 (siRNA) Phase 1 Trial [12] | Factor XI Reduction | >93% peak reduction in FXI activity; sustained effect up to 6 months post-single dose |

| AAV-CRISPR Prime Editing (Mouse) [7] | In Vivo Editing Efficiency | Optimized "v3em PE-AAV" achieved 42% prime editing efficiency in the mouse brain |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AAV-Based Gene Therapy Research

| Reagent / Solution | Function & Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| AAV Serotypes | Determine tissue tropism and transduction efficiency. | AAV9: Crosses BBB, systemic/CNS delivery [6]. AAV2: Local delivery, high neuronal transduction [6]. AAV5: Broad spread within striatum [6]. |

| Promoters | Control cell-type specificity and expression level of the transgene. | Ubiquitous: CAG, CBh [6]. Neuron-specific: hSyn, CaMKIIα [6]. |

| Production Systems | Manufacture high-titer, high-purity AAV vectors for research and clinic. | Triple Transfection (HEK293 cells) [8]. Baculovirus/Sf9 System (insect cells) for scalable production [8]. |

| Genome Engineering Elements | Fine-tune expression and enhance safety. | miRNA Target Sites: Detarget transgene from off-target cells [6]. WPRE: Enhances RNA stability and expression [6]. |

| CRISPR Components | Enable gene editing within the AAV delivery framework. | Guide RNA (gRNA): Targets nuclease. Cas Nucleases: e.g., SpCas9, SaCas9 (smaller size). Intein Systems: For splitting large Cas proteins into two AAVs [7]. |

AAV's well-established safety profile, capacity for long-term gene expression, and versatility through serotype and genome engineering firmly support its status as the gold standard for in vivo gene delivery. While RNA-based therapies like siRNA offer a potent, often reversible means of gene knockdown, AAV-based strategies provide a more durable solution for gene replacement, as evidenced by long-term studies showing sustained transgene expression for over seven years [11]. The ongoing convergence of AAV with revolutionary technologies like CRISPR is further expanding its potential, moving beyond gene augmentation to precise gene editing. For researchers and drug developers targeting neurological disorders, the strategic choice between AAV, other viral vectors, and RNA-based platforms will continue to hinge on the specific genetic pathology, desired duration of effect, and the critical balance between therapeutic potency and safety.

RNA-based therapeutics have revolutionized modern medicine by offering versatile and precise modalities to modulate gene expression for a wide range of diseases, including neurological disorders, genetic conditions, and cancer [13]. This therapeutic class represents a paradigm shift from conventional approaches, moving beyond the limitation of targeting only approximately 0.05% of the human genome that is druggable by small molecules and antibodies [14]. By leveraging the fundamental principles of Watson-Crick base pairing, RNA therapeutics can theoretically target any gene of interest, thereby dramatically expanding the therapeutic landscape [14].

The field has evolved from foundational discoveries—such as the development of antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) in the late 1970s and the discovery of RNA interference (RNAi) in the 1990s—into a robust therapeutic platform with multiple approved drugs [13]. The successful global deployment of mRNA vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic further validated RNA as a scalable, adaptable modality capable of rapid response to public health crises [13] [15]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of major RNA therapeutic modalities—ASOs, siRNA, and mRNA vaccines—within the specific context of neurological disease research, examining their mechanisms, clinical applications, delivery challenges, and experimental considerations.

Comparative Analysis of RNA Therapeutic Modalities

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Major RNA Therapeutic Modalities

| Parameter | ASOs | siRNA | mRNA Therapeutics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | Single-stranded oligonucleotides (12-24 nt) [14] | Double-stranded RNA (20-25 bp) [16] [14] | Single-stranded coding RNA with 5' cap and poly-A tail [15] |

| Primary Mechanism | RNase H1-mediated degradation, splice switching, steric blockade [14] | RISC-mediated cleavage of complementary mRNA [15] [14] | Cellular production of encoded therapeutic proteins [15] |

| Cellular Target | Nucleus & cytoplasm [14] | Cytoplasm [14] | Cytoplasm (ribosomes) [15] |

| Therapeutic Effect | Reduction, restoration, or modification of protein expression [14] | Transient knockout of specific protein production [17] | Transient production of therapeutic proteins/antigens [15] |

| Duration of Effect | Weeks to months (requiring repeated administration) [16] | Several months (long-lasting silencing) [15] | Days (transient expression) [15] |

| Key Modifications | 2'-MOE, PMO, PS backbone, LNA [18] [14] | 2'-OMe, 2'-F modifications [13] | Pseudouridine, 5-methoxyuridine [13] |

| Delivery Platforms | Intrathecal injection, GalNAc conjugation [18] [16] | LNP, GalNAc conjugation [13] [15] | LNP, polymeric nanoparticles [13] [15] |

| Typical Dose Frequency | Quarterly to semi-annually after loading doses [18] | Quarterly to semi-annually [15] | Single or two-dose regimens (vaccines) [13] |

Table 2: Clinically Approved RNA Therapeutics for Neurological and Other Disorders

| Therapeutic (Brand Name) | Modality | Target/Indication | Year Approved | Key Clinical Trial Efficacy Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nusinersen (Spinraza) [18] | ASO (splice-switching) | SMN2 for spinal muscular atrophy | 2016 [18] | 51% of infants achieved motor milestone response vs. 0% sham-procedure (ENDEAR trial) [13] |

| Patisiran (Onpattro) [17] | siRNA (LNP) | Transthyretin (hATTR amyloidosis) | 2018 [13] [17] | Improved neuropathy scores (APOLLO trial) [13] |

| Eteplirsen (Exondys 51) [18] | ASO (exon skipping) | DMD exon 51 for Duchenne muscular dystrophy | 2016 [18] | Increased dystrophin expression to 0.93% of normal vs. 0.09% baseline (phase 2) [14] |

| Inclisiran (Leqvio) [13] | siRNA (GalNAc) | PCSK9 for hypercholesterolemia | 2021 [13] | LDL-C reduction sustained >18 months (ORION trials) [13] |

| mRNA-1345 [13] | mRNA vaccine (LNP) | RSV for older adults | 2024 (priority review) [13] | Phase III positive results (specific efficacy data pending) [13] |

| Tofersen (Qalsody) [19] | ASO | SOD1 for ALS | 2023 [19] [17] | Reduced SOD1 protein levels by 36% vs. placebo; slowed functional decline [17] |

Molecular Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

ASOs: Multimodal Mechanisms of Action

ASOs employ diverse mechanisms to modulate gene expression, broadly categorized into occupancy-mediated degradation and occupancy-only (steric blockade) mechanisms [14]. The degradation pathway involves RNase H1-mediated cleavage of the target RNA when bound to a complementary ASO, effectively reducing target protein levels [14]. In contrast, steric blockade mechanisms involve ASOs binding to pre-mRNA to modulate splicing patterns—either promoting exon inclusion (as with nusinersen in SMA) or exon skipping (as with eteplirsen in DMD) without degrading the target RNA [18] [14]. Additional steric blockade mechanisms include translational arrest, alteration of 5' capping or polyadenylation, and modulation of miRNA activity [14].

siRNA and RNA Interference Pathway

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) function through the conserved RNA interference (RNAi) pathway. The double-stranded siRNA is loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), where the passenger strand is cleaved by Argonaute 2 (AGO2) protein and discarded [14]. The guide strand then directs RISC to complementary mRNA sequences, leading to AGO2-mediated cleavage and degradation of the target transcript, effectively preventing translation of the encoded protein [15] [14]. This mechanism provides high specificity in gene silencing, making siRNA particularly valuable for targeting dominant gain-of-function mutations in neurological disorders [16].

mRNA Therapeutics: Protein Replacement Paradigm

mRNA therapeutics employ a fundamentally different approach—rather than inhibiting gene expression, they introduce mRNA encoding therapeutic proteins to achieve temporary protein production within host cells [15]. The synthetic mRNA, engineered with modified nucleosides and optimized codons, is translated by cellular ribosomes into functional proteins that can replace deficient enzymes, generate vaccine antigens, or provide therapeutic factors [13] [15]. This platform offers particular promise for monogenic disorders where supplementing a functional protein can ameliorate disease symptoms, though applications in neurological disorders require advanced delivery strategies to cross the blood-brain barrier [19].

Delivery Technologies for Neurological Applications

Effective delivery remains the most significant challenge for RNA therapeutics, particularly for neurological disorders where the blood-brain barrier (BBB) restricts access to the central nervous system [18] [19]. The BBB prevents passive diffusion of RNA molecules, necessitating specialized delivery approaches.

Table 3: Delivery Methods for RNA Therapeutics in Neurological Disorders

| Delivery Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Representative Therapeutics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrathecal Injection [18] | Direct administration into cerebrospinal fluid | Bypasses BBB, achieves high CNS concentrations | Invasive procedure, requires specialized medical care | Nusinersen [18], Tofersen [19] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNP) [13] | Encapsulation for cellular uptake and endosomal escape | Protects RNA, enhances bioavailability, tunable properties | Primarily hepatic tropism, potential immunogenicity | Patisiran [17], mRNA vaccines [13] |

| GalNAc Conjugation [13] | Targets asialoglycoprotein receptor on hepatocytes | Efficient liver delivery, reduced dosing frequency | Limited to hepatic applications | Givosiran, Inclisiran [13] |

| Viral Vectors (AAV) [16] | Viral-mediated gene transfer | Long-lasting expression, efficient transduction | Potential immunogenicity, limited DNA cargo capacity | Onasemnogene abeparvovec (Zolgensma) [16] |

| Peptide Conjugates [18] | Cell-penetrating peptides enhance cellular uptake | Improved tissue penetration, potential for CNS targeting | Optimization required for specificity | Research-stage pPMOs [18] |

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

Standard Protocol for In Vitro RNA Therapeutic Screening

Objective: Evaluate efficacy and specificity of candidate RNA therapeutics in neuronal cell cultures.

Methodology:

- Cell Culture: Maintain relevant neuronal cell lines (e.g., SH-SY5Y, PC12) or primary neurons in appropriate media [19].

- Therapeutic Transfection:

- Control Design:

- Efficacy Assessment (48-72 hours post-transfection):

- Specificity Validation:

In Vivo Protocol for Preclinical Assessment in Neurological Models

Objective: Determine therapeutic efficacy and biodistribution in animal models of neurological disease.

Methodology:

- Animal Models: Utilize established neurological disease models (e.g., SOD1G93A mice for ALS, SMA transgenic mice) [19] [16].

- Dosing Paradigm:

- Biodistribution Analysis:

- Efficacy Endpoints:

- Safety Evaluation:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for RNA Therapeutics Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Modification Kits [14] | 2'-MOE, 2'-O-Me, LNA, phosphorothioate | Enhance stability, reduce immunogenicity, improve binding affinity | Optimization required for each modality and target |

| Delivery Vehicles [19] | Cationic lipids, polymers, GalNAc conjugates | Enable cellular uptake and endosomal escape | Cell-type specific efficiency; potential cytotoxicity |

| Vector Systems [16] | AAV9, AAV-PHP.eB, lentiviral vectors | In vivo gene delivery with CNS tropism | Immunogenicity concerns; cargo size limitations |

| Analytical Tools [13] | HPLC, mass spectrometry, dynamic light scattering | Quality control of RNA and formulations | Critical for characterizing purity, size, stability |

| Cell-based Assays [14] | Luciferase reporter systems, splice-switching assays | High-throughput screening of candidate molecules | Requires careful design of relevant reporter constructs |

| Animal Models [16] | Transgenic, knock-in, patient-derived xenografts | Preclinical efficacy and safety evaluation | Species-specific differences in RNA processing and immunity |

Comparative Clinical Trial Design Considerations

Table 5: Key Considerations for Clinical Trial Design of RNA Therapeutics

| Trial Phase | Primary Objectives | Key Endpoints | Special Considerations for Neurological Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preclinical | Target engagement, biodistribution, safety profile | Biomarker modulation, tissue distribution, MTD | BBB penetration, neuronal uptake, long-term CNS effects |

| Phase I | Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics | Adverse events, dose-limiting toxicities, CSF levels | Route of administration (intrathecal vs. systemic), CSF pharmacokinetics |

| Phase II | Preliminary efficacy, dose optimization | Clinical outcome measures, biomarker correlation | Patient selection based on genetic markers, disease staging |

| Phase III | Confirmatory efficacy, risk-benefit assessment | Primary clinical endpoint, quality of life measures | Novel endpoints for neurodegenerative diseases, long-term follow-up |

The RNA therapeutics landscape represents a rapidly evolving field that has fundamentally expanded our approach to treating neurological diseases. ASOs offer remarkable precision for splice modulation and allele-specific targeting, siRNAs provide potent and durable gene silencing, while mRNA platforms enable protein replacement and vaccination strategies. Each modality presents distinct advantages and limitations that must be carefully considered in the context of specific disease mechanisms and target tissues.

Future developments in RNA therapeutics will likely focus on overcoming the persistent challenge of delivery, particularly to extrahepatic tissues like the CNS [13] [19]. Emerging technologies including circular RNA with enhanced stability, self-amplifying RNA for reduced dosing, and CRISPR-based RNA editing systems promise to further expand the therapeutic arsenal [13] [17]. Additionally, advances in chemical modifications, delivery platforms, and targeting ligands will continue to improve the efficacy, safety, and applicability of RNA medicines.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the current landscape offers unprecedented opportunities to develop treatments for previously undruggable targets. The continued refinement of these platforms, coupled with deeper understanding of disease biology, heralds a new era of precision medicine for neurological disorders and beyond.

The strategic choice between gene therapies and RNA-based treatments for neurological disorders hinges on accurately identifying the underlying molecular disease mechanism. Pathogenic variants can cause disease through two primary mechanisms: loss-of-function (LOF), where a mutation reduces or eliminates the biological activity of a protein, and gain-of-toxic-function (GOF), where a mutation confers new, often deleterious, properties to the protein [20] [21]. This distinction is therapeutically critical, as LOF diseases typically require functional restoration of the affected pathway, while GOF diseases necessitate suppression or neutralization of the toxic protein [20]. This guide provides a structured comparison of these pathological mechanisms and their implications for selecting appropriate therapeutic modalities, focusing on experimental approaches for mechanism identification and the corresponding reagent solutions that enable this research.

Comparative Analysis of Disease Mechanisms

Defining Characteristics and Therapeutic Implications

Table 1: Core Characteristics of LOF and GOF Pathologies

| Feature | Loss-of-Function (LOF) | Gain-of-Toxic-Function (GOF) |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Consequence | Reduced or abolished protein activity [20] | Ectopic or enhanced protein activity, often with dominant-negative effects [20] |

| Inheritance Pattern | Often recessive (requires both alleles) [21] | Often dominant (single mutant allele sufficient) [21] |

| Ideal Therapeutic Strategy | Gene replacement, protein upregulation [20] [22] | Gene silencing, protein inhibition [20] [22] |

| Exemplary Neurological Disorders | Dravet Syndrome (SCN1A), RPE65-associated retinal dystrophy, Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) [20] [21] [22] | Huntington's disease, some forms of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), Retinitis Pigmentosa (p.Pro23His in rhodopsin) [20] [21] |

Prevalence and Mechanistic Heterogeneity

Large-scale phenotypic analyses reveal the widespread nature of these mechanisms. A 2025 study analyzing 2,837 phenotypes across 1,979 Mendelian disease genes found that dominant-negative (DN) and gain-of-function mechanisms account for 48% of phenotypes in dominant genes [21]. Furthermore, the study identified widespread intragenic mechanistic heterogeneity, with 43% of dominant and 49% of mixed-inheritance genes harboring both LOF and non-LOF mechanisms for different phenotypes [21]. This complexity necessitates phenotype-level analysis rather than simple gene-level classification.

Table 2: Prevalence of Molecular Disease Mechanisms (2025 Data)

| Category | Prevalence of LOF | Prevalence of non-LOF (GOF/DN) |

|---|---|---|

| Phenotypes in Dominant Genes | 52% | 48% [21] |

| Genes with Multiple Phenotypes (showing mechanistic heterogeneity) | 43% (Dominant Genes), 49% (Mixed-Inheritance Genes) | [21] |

Experimental Protocols for Mechanism Identification

Structural Bioinformatic Prediction (in silico)

Objective: To predict the molecular mechanism (LOF vs. GOF) of a set of missense variants using protein structural features [21].

- Variant Set Curation: Compile pathogenic missense variants for a gene of interest, ideally associated with a single phenotype, from databases like ClinVar.

- Energetic Impact Calculation ((\Delta\Delta G{rank})): Use a protein stability prediction tool (e.g., FoldX) to compute the change in Gibbs free energy ((\Delta\Delta G)) for each variant. Normalize these values into a rank-based metric ((\Delta\Delta G{rank})) to facilitate cross-protein comparisons [21].

- Spatial Clustering Analysis (EDC): Calculate the Extent of Disease Clustering (EDC) metric. This quantifies the three-dimensional clustering of the submitted variants within the protein structure [21].

- mLOF Score Calculation: Input the (\Delta\Delta G_{rank}) and EDC values into an empirical distribution-based model (e.g., the published Google Colab notebook) to compute a missense LOF (mLOF) likelihood score [21].

- Mechanism Classification: Apply the optimal threshold (mLOF score = 0.508) to classify the variant set as likely LOF (score > 0.508) or non-LOF (score < 0.508), indicative of GOF/DN mechanisms [21].

Functional Validation in Cellular Models

Objective: To experimentally validate the predicted mechanism in a relevant cell model (e.g., iPSC-derived neurons).

- Model Generation: Introduce the patient-derived variant(s) into a control cell line (e.g., via CRISPR-Cas9) or use patient-derived iPSCs differentiated into relevant neuronal cell types [22].

- Gene Dosage Response (Haploinsufficiency Test):

- Transfert cells with a wild-type (WT) gene expression construct. If this rescues the cellular phenotype, it supports an LOF mechanism.

- Transfert cells with siRNA or ASOs targeting the endogenous mutant allele. If this exacerbates the phenotype, it supports an LOF mechanism; if it rescues the phenotype, it supports a GOF mechanism [22].

- Protein Activity Assay: Perform domain-specific functional assays tailored to the protein's known function (e.g., electrophysiology for ion channels, enzymatic assays for kinases, DNA-binding assays for transcription factors).

- Pathway Analysis: Use techniques like RNA sequencing or quantitative phospho-proteomics to assess downstream pathway activity. Widespread, distributed perturbations suggest LOF, while specific, clustered pathway activation suggests GOF [20].

Visualization of Therapeutic Strategies

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting a therapeutic modality based on the identified genetic pathology, integrating both established and emerging technologies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating Genetic Pathologies

| Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Application in LOF/GOF Research |

|---|---|---|

| FoldX | Protein stability prediction from structure [21] | Calculates (\Delta\Delta G) to quantify energetic impact of missense variants; high destabilization suggests LOF. |

| mLOF Score Colab Notebook | Integrates EDC and (\Delta\Delta G_{rank}) [21] | Computes a likelihood score for LOF mechanism from a set of variants; critical for in silico prediction. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Precise genome editing [23] | Introduces patient-specific variants into cell lines (for GOF studies) or corrects them (for LOF therapeutic modeling). |

| Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Vectors | In vitro and in vivo gene delivery [23] | Delivers functional gene copies for LOF rescue experiments or CRISPR components for mechanistic studies. |

| Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs) | Sequence-specific mRNA targeting [22] | Validates mechanism by knocking down mutant transcripts; potential therapeutic for GOF pathologies. |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Patient-derived cellular models [22] | Provides a physiologically relevant human neuronal context for functional validation of LOF/GOF hypotheses. |

The precise distinction between LOF and GOF mechanisms is a foundational step in the rational design of neurological therapies. While LOF pathologies generally call for strategies that restore function, such as gene addition or protein upregulation, GOF pathologies demand approaches that silence or inhibit the toxic gene product [20] [22]. The experimental framework and toolkit presented here provide a roadmap for researchers to characterize these mechanisms definitively. The growing observation of intragenic mechanistic heterogeneity further underscores the necessity of this precise classification, moving beyond gene-level to phenotype-level understanding to enable the development of safe and effective, mechanism-based treatments for genetic neurological disorders [21].

The field of neurogenetics is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the identification of over 1,700 genes in which pathogenic variants can cause neurogenetic disorders [24]. This expansive genetic landscape represents both a formidable challenge and an unprecedented therapeutic opportunity. Neurological disorders, affecting approximately 15% of the global population, stand as the leading cause of physical and cognitive disabilities worldwide [3]. The traditional classification of these disorders has evolved from purely clinical descriptions to a molecular understanding, distinguishing between monogenic forms with Mendelian inheritance patterns and complex polygenic disorders influenced by multiple genetic and environmental factors [25] [26].

The therapeutic paradigm is shifting accordingly, from symptomatic management to targeting fundamental disease mechanisms. Two leading technological platforms have emerged at the forefront of this revolution: gene therapies, which aim to deliver corrected genetic material, and RNA-based therapeutics, which modulate gene expression at the transcript level. The global rare disease therapeutics market, valued at $154.64 billion in 2024 and projected to reach $495.27 billion by 2033, reflects the massive investment and growth in these modalities, with gene therapy constituting the fastest-growing segment at $28 billion in 2024 [27]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of these platforms, examining their respective mechanisms, clinical applications, and experimental approaches for neurological disorders.

Comparative Analysis of Therapeutic Platforms

Gene Therapy Approaches

Gene therapy encompasses strategies designed to introduce, modify, or correct genetic material within a patient's cells to treat disease. The primary approaches include gene replacement for loss-of-function mutations and gene editing for precise DNA modification.

Table 1: Gene Therapy Platforms for Neurological Disorders

| Approach | Mechanism | Key Vectors | Representative Targets | Development Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Replacement | Delivers functional cDNA to compensate for defective genes | AAV, Lentivirus | Friedreich's ataxia (FXN), Parkinson's disease (GDNF), Rett syndrome | Clinical trials & approved therapies (e.g., Zolgensma for SMA) |

| Gene Editing | Uses engineered nucleases to modify DNA sequences | CRISPR-Cas9, Base Editors | ALS (C9orf72), Huntington's disease, Alzheimer's disease | Preclinical and early-phase clinical trials |

| Oncolytic Virotherapy | Uses engineered viruses to selectively replicate in and lyse cancer cells | Modified HSV, Adenovirus | Glioblastoma, other brain tumors | Approved (e.g., T-VEC) and clinical trials |

The adeno-associated virus (AAV) platform dominates neurological gene delivery, with 343 clinical trials ongoing as of January 2025, representing a 34% increase from mid-2022 [28]. These trials primarily target ocular (26%), central nervous system (21%), and liver (18%) tissues, with AAV2 (24%), AAV9 (16%), and AAV8 (13%) being the most frequently used capsids [28]. The field is increasingly adopting engineered capsids, with 39 trials now utilizing 15 unique novel capsids designed to overcome limitations of natural serotypes, such as pre-existing immunity and poor blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration [28].

Recent clinical milestones underscore the progress in this domain. In 2025, MeiraGTx's AAV gene therapy for Parkinson's disease received Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy (RMAT) designation from the FDA, while MavriX Bio gained clearance for a first-in-human Phase 1 study for Angelman syndrome [28]. AviadoBio also dosed the first patients in a gene therapy trial for frontotemporal dementia, representing a pioneering approach for dementia treatment [28].

RNA-Based Therapeutic Platforms

RNA therapeutics encompass a diverse range of modalities that function at the transcript level rather than modifying DNA. These approaches offer transient but tunable regulation of gene expression and can target previously "undruggable" pathways.

Table 2: RNA-Based Therapeutic Platforms for Neurological Disorders

| Modality | Mechanism | Key Delivery Systems | Representative Applications | Development Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASOs) | Single-stranded oligonucleotides that modulate RNA processing, splicing, or degradation | Chemical modifications, intrathecal delivery | Spinal Muscular Atrophy (Nusinersen), Huntington's disease, ALS | Multiple FDA approvals, expanding clinical applications |

| siRNA | Double-stranded RNA that guides sequence-specific mRNA degradation via RISC | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), GalNAc conjugates | Transthyretin amyloidosis (Patisiran), ongoing neurology trials | Approved therapies, expanding to neurological indications |

| mRNA Therapeutics | Encodes therapeutic proteins for in vivo production | LNPs, novel delivery systems | Protein replacement, vaccine applications, regenerative medicine | Approved vaccines, neurological applications in development |

RNA-based therapies have gained substantial validation through clinical successes, most notably the 2016 approval of nusinersen for spinal muscular atrophy and the global deployment of mRNA vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic [29]. These achievements demonstrated that RNA platforms could overcome historical challenges of instability, immunogenicity, and delivery. Technological innovations have been crucial to this progress, including nucleotide modifications that reduce immune activation and improve stability, and advanced delivery systems like lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) that protect RNA payloads and facilitate cellular uptake [29].

The clinical pipeline for RNA therapeutics continues to expand, with promising developments in 2025 including eplontersen for transthyretin amyloidosis and the approval of exa-cel, the first CRISPR-based RNA-guided editing therapy for sickle cell disease [29]. Emerging modalities such as self-amplifying RNAs, circular RNAs with enhanced stability, and RNA-targeting small molecules represent the next frontier of innovation [29].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

In Vivo Vector Evaluation Protocol

The assessment of gene therapy vectors in preclinical models follows a standardized workflow to establish safety, biodistribution, and efficacy profiles. The following protocol outlines key steps for evaluating AAV vectors for neurological applications:

Capsid Selection and Engineering: Choose natural serotypes (AAV9, AAVrh.10) with inherent CNS tropism or employ engineered capsids with enhanced BBB penetration capabilities. Engineering approaches include directed evolution based on novel BBB-transducing capsids or rational design incorporating targeting ligands [30] [28].

Vector Construction: Clone the therapeutic expression cassette (typically comprising a promoter, transgene, and polyA signal) into the AAV plasmid backbone. Optimize cassette elements for cell-type-specific expression and durable transgene expression. Self-complementary genomes may be utilized for more rapid onset of expression [28].

Vector Production and Purification: Produce recombinant AAV vectors using triple transfection of HEK293 cells or baculovirus/Sf9 system. Purify via iodixanol gradient ultracentrifugation or chromatography. Determine vector genome titer using digital droplet PCR and confirm purity/identity through SDS-PAGE, ELISA, and endotoxin testing [28].

In Vivo Administration: Administer vectors to appropriate animal models (murine, porcine, non-human primate) via route relevant to clinical translation (intrathecal, intracisternal magna, intraventricular, intra-parenchymal, or intravenous injection). Include vehicle-treated and/or sham surgery control groups [28] [24].

Biodistribution and Engraftment Analysis: At predetermined endpoints, quantify vector genome copies in target (CNS regions) and off-target (peripheral organs) tissues using qPCR. Assess transgene expression via immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization, and/or Western blot. Evaluate cellular tropism through co-localization studies with neuronal, glial, and other CNS cell markers [30] [28].

Efficacy Assessment: Employ disease-relevant functional and histopathological outcome measures. These may include motor performance (rotarod, gait analysis), cognitive testing (Morris water maze), electrophysiology, survival, and quantification of disease-specific biomarkers or pathological hallmarks [28] [24].

Safety Evaluation: Monitor for acute adverse events. Conduct detailed histopathological analysis of CNS and peripheral tissues. Assess immunogenicity (anti-AAV antibodies, T-cell responses). Evaluate potential germline transmission [28].

This protocol generates comprehensive data packages required for regulatory submissions and clinical trial design, with particular emphasis on establishing a favorable therapeutic index.

RNA Therapeutic Efficacy Assessment

The evaluation of RNA-based therapeutics employs distinct methodologies optimized for transcript-targeting modalities:

Oligonucleotide Design and Synthesis: Design ASO or siRNA sequences with complete complementarity to target RNA. Incorporate chemical modifications (2'-O-methyl, 2'-fluoro, phosphorothioate, morpholino) to enhance nuclease resistance, binding affinity, and pharmacokinetics. For mRNA therapeutics, optimize codon usage, 5' and 3' UTRs, and incorporate modified nucleosides (pseudouridine) to reduce immunogenicity and enhance translational efficiency [29].

Formulation Development: For systemic delivery beyond the liver, develop advanced delivery systems. These include lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) with ionizable lipids, polymer-based nanoparticles, or conjugate strategies (e.g., GalNAc for hepatocyte targeting, peptide conjugates for CNS delivery). Characterize particle size, encapsulation efficiency, and stability [29].

In Vitro Screening: Transfer candidate molecules into relevant cell models (primary neurons, glial cells, iPSC-derived neural cells). Assess mRNA knockdown (for siRNA/ASO) or protein expression (for mRNA) via qRT-PCR, Western blot, and/or immunofluorescence. Evaluate cell viability and innate immune activation (IFN response) [29].

In Vivo Administration in Disease Models: Administer to genetically accurate animal models via clinically relevant routes. For neurological applications, intrathecal or intracerebroventricular delivery is often employed to bypass the BBB. Include mismatch or scrambled sequence controls [29] [3].

Target Engagement and Biomarker Analysis: Quantify reduction of target RNA (siRNA/ASO) or production of encoded protein (mRNA). Measure downstream biomarkers, including disease-specific proteins, metabolites, or functional endpoints [29].

Phenotypic Rescue Assessment: Evaluate therapeutic effect using disease-specific behavioral tests (locomotor, cognitive), electrophysiological measures, survival, and histopathological analysis of disease hallmarks (protein aggregates, neuronal loss, neuroinflammation) [29] [3].

Toxicology and Pharmacokinetics: Assess plasma and tissue half-life. Evaluate potential organ toxicity (liver, kidney, CNS). Monitor for immune activation and off-target transcript effects via transcriptomic analysis [29].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for evaluating RNA-based therapeutics for neurological disorders, encompassing design, formulation, and comprehensive preclinical testing.

Technological Innovations and Research Reagents

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Advancing neurogenetic therapies requires specialized research tools and reagents designed to overcome the unique challenges of the nervous system. The following table details critical solutions for experimental neuroscience research:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Neurogenetic Therapy Development

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Next-Generation Sequencing | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS), Whole Exome Sequencing (WES), Long-Read Sequencing (PacBio, Nanopore) | Identifying disease-causing variants, detecting repeat expansions, transcriptome analysis | Long-read technologies resolve structurally complex regions; WES covers coding regions; WGS provides complete genomic picture [25] [26] |

| Advanced Delivery Vectors | Engineered AAV capsids, BBB-penetrant LNPs, Extracellular Vesicles | Overcoming biological barriers, achieving cell-type-specific delivery in CNS | Novel AAV capsids with enhanced tropism; LNPs optimized for extrahepatic delivery; EVs as natural delivery vehicles [30] [28] [24] |

| Disease Modeling Systems | Patient-derived iPSCs, Organoids, Genetically engineered animal models | Pathogenesis studies, target validation, therapeutic screening | Human iPSC-derived neurons recapitulate patient genetics; organoids model tissue complexity; animal models assess systemic effects [24] [26] |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, Base Editors, Prime Editors, Epigenetic Editors | Functional genomics, target validation, therapeutic genome modification | CRISPR enables gene knockout; base editors introduce precise point mutations; epigenetic editors modulate gene expression without DNA cleavage [28] [29] |

| Biodistribution & Expression Reporters | Bioluminescence Imaging, Fluorescent Reporters, bDNA Assays | Tracking vector distribution, quantifying transgene expression, measuring mRNA knockdown | Non-invasive imaging enables longitudinal tracking; sensitive assays quantify nucleic acids without amplification; fluorescent tags visualize expression patterns [28] |

Engineering Solutions for Neurological Delivery

The blood-brain barrier represents the most significant obstacle for delivering neurogenetic therapies. Innovative engineering approaches are being developed to overcome this challenge:

Figure 2: Engineering strategies to overcome the blood-brain barrier, including vector engineering and formulation innovations for enhanced CNS delivery.

For AAV vectors, capsid engineering approaches include directed evolution to select for variants with enhanced CNS tropism from random peptide libraries displayed on capsid surfaces, and rational design incorporating known BBB-targeting motifs [28]. The administration route is equally critical, with direct intrathecal or intracisternal magna delivery often providing superior CNS distribution compared to intravenous administration while reducing peripheral exposure and potential toxicity [28] [24].

For RNA therapeutics, formulation innovations focus on BBB-penetrant lipid nanoparticles with carefully engineered lipid compositions that facilitate transcytosis across brain endothelial cells. Alternative approaches include receptor-targeted conjugates that exploit endogenous transport systems, such as transferrin or insulin receptors, to mediate BBB passage [29]. Engineered extracellular vesicles derived from mesenchymal stem cells or other cellular sources represent an emerging biomimetic delivery platform with inherent biocompatibility and potential for CNS targeting [30].

The neurogenetic landscape, with over 1,700 potential target genes, presents both unprecedented challenges and opportunities. Gene therapies and RNA-based therapeutics offer complementary approaches—the former providing potential permanent correction, the latter enabling tunable and reversible modulation of gene expression. The clinical success of both modalities will depend on continued innovation in delivery technologies, particularly for overcoming the blood-brain barrier and achieving cell-type-specific targeting in the complex environment of the human brain.

Future progress will be accelerated by several converging technological trends. Long-read sequencing technologies are improving the detection of structural variants and repeat expansions in neurogenetic disorders [26]. Artificial intelligence is being leveraged to predict the pathogenicity of variants of uncertain significance and to optimize therapeutic design [29] [27]. Multimodal approaches that combine, for example, gene editing with RNA therapeutics may offer synergistic benefits for addressing complex genetic pathologies.

The translation of these technologies into clinical applications will require ongoing collaboration between academic researchers, industry partners, regulatory agencies, and patient advocacy groups. As the field advances, the development of robust biomarkers and innovative clinical trial designs will be essential for demonstrating efficacy in heterogeneous neurological disorders. With continued progress, gene-targeted therapies promise to transform the management of neurogenetic disorders from symptomatic care to definitive treatments that address underlying disease mechanisms.

Therapeutic Applications and Clinical Translation in Neurology

Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) represent a transformative class of RNA-targeted therapeutics that enable precise modulation of gene expression through complementary base pairing with target RNA sequences. The field has evolved significantly since its conceptualization in 1978 by Zamecnik and Stephenson, who first demonstrated that short oligonucleotides could inhibit Rous sarcoma virus replication [31]. Today, ASOs have emerged as promising therapeutic agents for a wide spectrum of monogenic disorders, particularly neurological and neuromuscular diseases, offering distinct advantages over traditional gene therapy approaches, especially for conditions where permanent genomic alteration may be undesirable [32].

The versatility of ASO mechanisms allows researchers to tailor therapeutic strategies to specific molecular pathologies. Current approaches encompass three primary modalities: splice-switching to correct aberrant pre-mRNA splicing, gene silencing to reduce expression of toxic proteins, and targeted upregulation to enhance expression of functional proteins [32]. This mechanistic diversity positions ASOs as a powerful platform for addressing the root causes of genetic disorders at the RNA level, providing a promising alternative to therapies targeting downstream pathological processes [31].

Within the context of neurological disorders, ASOs offer particular promise due to their ability to be delivered directly to the central nervous system via intrathecal administration, effectively bypassing the blood-brain barrier [31] [32]. This review systematically compares the three major ASO modalities, providing experimental data, detailed methodologies, and analytical frameworks to guide researchers in selecting and implementing appropriate ASO strategies for specific research and therapeutic applications.

Comparative Analysis of ASO Modalities

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major ASO Modalities

| Modality | Mechanism of Action | Chemical Design | Key Applications | FDA-Approved Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Splice-Switching | Steric blockade of splicing regulatory elements; redirects splicing outcomes | 2'-O-methyl (2'-O-Me), 2'-O-methoxyethyl (2'-MOE), phosphorodiamidate morpholino (PMO) | Duchenne muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy, ataxia-telangiectasia | Eteplirsen, golodirsen, nusinersen |

| Silencing (RNase H-dependent) | Activates RNase H-mediated degradation of target RNA | Gapmer design: central DNA flanked by modified nucleotides (e.g., 2'-MOE, LNA) | SOD1-ALS, Huntington's disease, hypercholesterolemia | Tofersen, mipomersen |

| Upregulation | Blocks regulatory elements that inhibit translation (uORFs, miRNA sites) | 2'-O-Me, 2'-MOE, constrained ethyl (cEt) modifications | Dravet syndrome (SCN1A restoration), translational enhancement | BIIB085 (clinical trials) |

Table 2: Experimental Parameters and Efficacy Metrics for ASO Modalities

| Modality | Cellular Localization | Optimal Length (nucleotides) | Key Efficacy Metrics | Therapeutic Index Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Splice-Switching | Nucleus | 18-25 | Exon skipping/inclusion efficiency, correction of reading frame, protein restoration | Off-target splicing effects, immune activation (e.g., TLR signaling) |

| Silencing | Nucleus/Cytoplasm | 16-20 | mRNA reduction (%), protein reduction (%), IC50 | Hepatotoxicity, thrombocytopenia, inflammatory responses |

| Upregulation | Cytoplasm | 18-22 | Protein level increase (fold-change), translational efficiency | Off-target protein expression, immune stimulation |

The comparative analysis reveals that each ASO modality possesses distinct mechanistic profiles and application-specific advantages. Splice-switching ASOs function primarily in the nucleus through steric blockade, making them ideal for correcting aberrant splicing patterns in diseases like Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) [33] [34]. The RNase H-dependent silencing approach employs a gapmer design that activates enzymatic degradation of complementary RNA sequences, providing potent reduction of toxic gene products in conditions like SOD1-associated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [31] [32]. Emerging upregulation strategies represent the most novel approach, utilizing ASOs to block inhibitory regulatory elements in untranslated regions, thereby enhancing translation of target proteins—a promising strategy for haploinsufficiency disorders [32].

Chemical modifications profoundly influence ASO performance across all modalities. First-generation phosphorothioate backbones improve nuclease resistance and protein binding but may increase nonspecific effects [31]. Second-generation modifications (2'-O-methyl, 2'-MOE) and third-generation designs (phosphorodiamidate morpholino, PMO; peptide-conjugated PMO, PPMO) further enhance binding affinity and safety profiles [33]. Recent advances in DMD therapeutics demonstrate how novel conjugations and chemical modifications significantly improve cellular uptake, endosomal escape, and nuclear import, leading to substantially enhanced exon-skipping efficacy compared to first-generation ASOs [33].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Splice-Switching ASO Protocol for Exon Skipping

Objective: To induce targeted exon skipping in the DMD gene for restoration of the reading frame and dystrophin expression.

Materials:

- Phosphorodiamidate morpholino (PMO) ASOs designed to target exon-intron boundaries of exon 51 in the DMD gene

- DMD patient-derived myoblasts or the hDMDdel52/mdx mouse model

- Delivery vehicle (e.g., electroporation for in vitro, intravenous injection for in vivo)

- RNA extraction kit and RT-PCR reagents

- Western blot system for dystrophin detection

- Immunofluorescence staining tools for dystrophin visualization

Procedure:

- ASO Design: Design 18-30 nucleotide PMO ASOs complementary to splice acceptor, donor sites, or exonic splicing enhancer regions of target exon [33].

- In Vitro Transfection: Deliver ASOs to patient-derived myoblasts using electroporation (500-750V/cm, 1-2 pulses, 20ms duration) at concentrations of 100-500nM [33].

- RNA Analysis: 48 hours post-transfection, extract total RNA and perform RT-PCR using primers flanking the target exon. Resolve products by agarose gel electrophoresis to visualize exon-skipped isoforms [33].

- Protein Analysis: 72-96 hours post-transfection, analyze dystrophin restoration by Western blot (4-12% Bis-Tris gel) and immunofluorescence using dystrophin-specific antibodies [33].

- In Vivo Validation: Administer ASOs (320 mg/kg weekly via tail-vein injection) to hDMDdel52/mdx mice for 12 weeks. Analyze muscle samples for dystrophin expression and functional improvement [33].

Troubleshooting: Low skipping efficiency may require optimization of ASO target sequence using bioinformatics tools (e.g., SpliceAI) or increased ASO concentration. Poor cellular uptake may be addressed by conjugation with cell-penetrating peptides [33].

RNase H-Mediated Silencing Protocol

Objective: To achieve allele-specific reduction of mutant huntingtin (HTT) protein in Huntington's disease models.

Materials:

- Gapmer ASOs with central DNA gap (8-10 nucleotides) flanked by 2'-MOE or LNA-modified wings

- Huntington's disease patient-derived fibroblasts or transgenic mouse models

- RNA extraction and qPCR reagents

- Western blot system for HTT detection

- Cell viability assay kits

Procedure:

- Allele-Specific Design: Design gapmers complementary to mutant HTT allele, incorporating mismatch for wild-type discrimination. Optimal length: 16-20 nucleotides with 5-10-5 gapmer design (5 modified nucleotides, 10 DNA nucleotides, 5 modified nucleotides) [31].

- In Vitro Transfection: Transfect patient-derived fibroblasts using lipid nanoparticles (0.1-100nM ASO concentration). Include mismatch control ASOs to assess specificity [31].

- mRNA Quantification: 24 hours post-transfection, extract RNA and perform RT-qPCR using allele-specific TaqMan assays to quantify mutant and wild-type HTT mRNA levels [31].

- Protein Analysis: 72 hours post-transfection, harvest cells for Western blot analysis using EM48 and 2B7 antibodies to detect mutant and total HTT protein, respectively [31].

- Toxicity Assessment: Perform MTT assay 96 hours post-transfection to assess cell viability. Monitor for activation of innate immune responses via cytokine profiling [31].

- In Vivo Validation: Administer ASOs intracerebroventricularly (100-500μg) to transgenic HD mice. Evaluate motor function improvements using rotarod and clasping tests over 4-12 weeks [31].

Troubleshooting: Inadequate allele specificity requires redesign of ASO sequence and positioning of mismatch. Immune activation may be mitigated by optimizing ASO length and chemical modification pattern [31].

Targeted Upregulation Protocol via uORF Blockade

Objective: To enhance translational efficiency of SCN1A mRNA for treatment of Dravet syndrome.

Materials:

- 2'-O-methoxyethyl (2'-MOE) ASOs targeting upstream open reading frames (uORFs) in SCN1A 5'UTR

- SCN1A haploinsufficiency mouse models

- Polysome profiling reagents

- RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) kit

- Western blot and immunohistochemistry materials

Procedure:

- uORF Mapping: Identify inhibitory uORFs in SCN1A 5'UTR through sequence analysis and functional reporter assays [32].

- ASO Design: Design 20-nucleotide 2'-MOE ASOs complementary to uORF start codons or regulatory regions to sterically block inhibitory elements [32].

- In Vitro Transfection: Transfert neuroblastoma cells or patient-derived neurons with ASOs (50-200nM) using lipid-based transfection.

- Translational Efficiency Assessment: Perform polysome profiling to measure SCN1A mRNA shift to translationally active fractions. Quantify nascent protein synthesis using puromycin incorporation assays [32].

- Protein Quantification: Measure NaV1.1 protein levels by Western blot (3-8% Tris-acetate gel) 72 hours post-transfection. Normalize to GAPDH and calculate fold-increase over controls [32].

- Functional Validation: In SCN1A haploinsufficiency mouse models, administer ASOs intracerebroventricularly (100μg). Monitor seizure frequency using EEG and video monitoring over 4 weeks [32].

Troubleshooting: Limited upregulation may require targeting multiple regulatory elements or optimizing ASO binding accessibility using structural prediction algorithms. Monitor for potential off-target effects on functionally related genes [32].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Diagram 1: Molecular Mechanisms of Major ASO Modalities. This pathway illustrates the three primary ASO mechanisms: splice-switching through steric blockade of splicing regulatory elements, gene silencing via RNase H-mediated degradation, and targeted upregulation through blockade of inhibitory elements in untranslated regions.

The molecular pathways governing ASO activity involve sophisticated interactions with cellular machinery that vary by modality. Splice-switching ASOs function through steric hindrance, binding pre-mRNA sequences to physically prevent the recognition of splicing regulatory elements by the spliceosome or splicing factors [34]. For example, in DMD, PMO ASOs targeting exon-intron junctions successfully redirect splicing machinery to exclude mutant exons, restoring the reading frame and enabling production of partially functional dystrophin proteins [33]. The therapeutic effect stems from altered splicing patterns rather than changes to the underlying genetic code, making this approach reversible and tunable.

RNase H-dependent silencing employs a fundamentally different mechanism utilizing a "gapmer" design where a central DNA segment activates RNase H cleavage of the target RNA, while flanking modified nucleotides enhance binding affinity and stability [31]. This approach demonstrates particular utility for dominant disorders where reducing expression of mutant proteins can ameliorate disease phenotypes, as demonstrated by tofersen for SOD1-ALS [35] [32]. The catalytic nature of this mechanism provides potent gene silencing effects, though it requires careful optimization to minimize off-target transcript degradation.

The most recently developed upregulation strategies represent a paradigm shift in ASO functionality, moving beyond suppression to enhancement of gene expression. These ASOs target regulatory elements in untranslated regions, such as upstream open reading frames (uORFs) or microRNA binding sites, that normally suppress translation [32]. By sterically blocking these inhibitory elements, ASOs can enhance translational efficiency without altering mRNA levels. This approach shows exceptional promise for haploinsufficiency disorders like Dravet syndrome, where increasing protein production from the single functional SCN1A allele can compensate for the loss-of-function mutation [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ASO Development and Validation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function in ASO Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Modification Tools | 2'-O-methyl (2'-O-Me), 2'-O-methoxyethyl (2'-MOE), phosphorodiamidate morpholino (PMO), locked nucleic acid (LNA) | Optimize stability, binding affinity, and cellular uptake | Enhance nuclease resistance, improve target engagement, reduce immunostimulation |

| Delivery Technologies | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), GalNAc conjugates, cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs), electroporation systems | Facilitate cellular internalization and subcellular localization | Overcome cellular barriers, enhance tissue-specific delivery, improve endosomal escape |

| Analytical Tools | RT-PCR/splicing assays, RNase H activity assays, polysome profiling, next-generation sequencing | Validate target engagement and mechanistic efficacy | Quantify splicing modifications, confirm RNA degradation, assess translational regulation |

| Cell-Based Models | Patient-derived fibroblasts, iPSC-derived neurons, immortalized cell lines, primary muscle cells | Preclinical efficacy and toxicity screening | Provide human disease-relevant context, assess allele-specific effects, evaluate functional rescue |

| Animal Models | hDMDdel52/mdx mice, SOD1G93A mice, Huntington's disease transgenic mice, non-human primates | In vivo efficacy, biodistribution, and toxicology studies | Evaluate physiological outcomes, determine therapeutic index, assess CNS penetration |

The development and optimization of ASO therapeutics requires specialized reagents and tools designed to address the unique challenges of oligonucleotide-based approaches. Chemical modification platforms form the foundation of ASO design, with each modification offering distinct advantages: 2'-O-methyl and 2'-MOE modifications provide enhanced nuclease resistance and binding affinity, while phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (PMOs) offer complete resistance to nucleases and reduced off-target effects [33] [31]. Recent advances include locked nucleic acid (LNA) modifications that dramatically increase binding affinity and peptide-conjugated PMOs (PPMOs) that significantly improve cellular uptake and biodistribution [33].