From Signal to Synapse: Advanced EEG Processing for Next-Generation Brain-Computer Interfaces

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest methodologies and advancements in electroencephalogram (EEG) signal processing for brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), tailored for researchers and biomedical professionals.

From Signal to Synapse: Advanced EEG Processing for Next-Generation Brain-Computer Interfaces

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the latest methodologies and advancements in electroencephalogram (EEG) signal processing for brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), tailored for researchers and biomedical professionals. It explores the foundational principles of EEG-based BCIs, delves into cutting-edge AI-driven processing techniques and their clinical applications, addresses critical challenges in signal optimization and hardware integration, and evaluates performance through rigorous validation and comparative analysis of emerging technologies. By synthesizing information from recent studies and market analyses, this review serves as a strategic resource for driving innovation in neurotechnology and clinical translation.

Fundamentals of EEG-BCI: From Neural Signals to System Architecture

A Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) establishes a direct communication pathway between the brain's electrical activity and an external device, bypassing conventional neuromuscular channels [1]. Electroencephalography (EEG)-based BCIs, which record neural signals from the scalp, represent the most widely used non-invasive approach due to their high temporal resolution, portability, and relative low cost [2] [3]. The foundational discovery of EEG by Hans Berger in 1924, who first recorded human brain electrical activity, paved the way for this technology [4] [1]. The term "brain-computer interface" was formally coined by Jacques Vidal in 1973, whose pioneering work demonstrated the first application of EEG signals for external control [4] [1]. Subsequent decades saw critical paradigm developments, including the P300 speller (1988), the first EEG-controlled robot (1988), and the refinement of sensorimotor rhythm-based and motor imagery-based BCIs [4]. Modern definitions characterize BCI as a "non-muscular channel" for interaction, reflecting its growing importance in assistive technology, neurorehabilitation, and human-computer interaction [4].

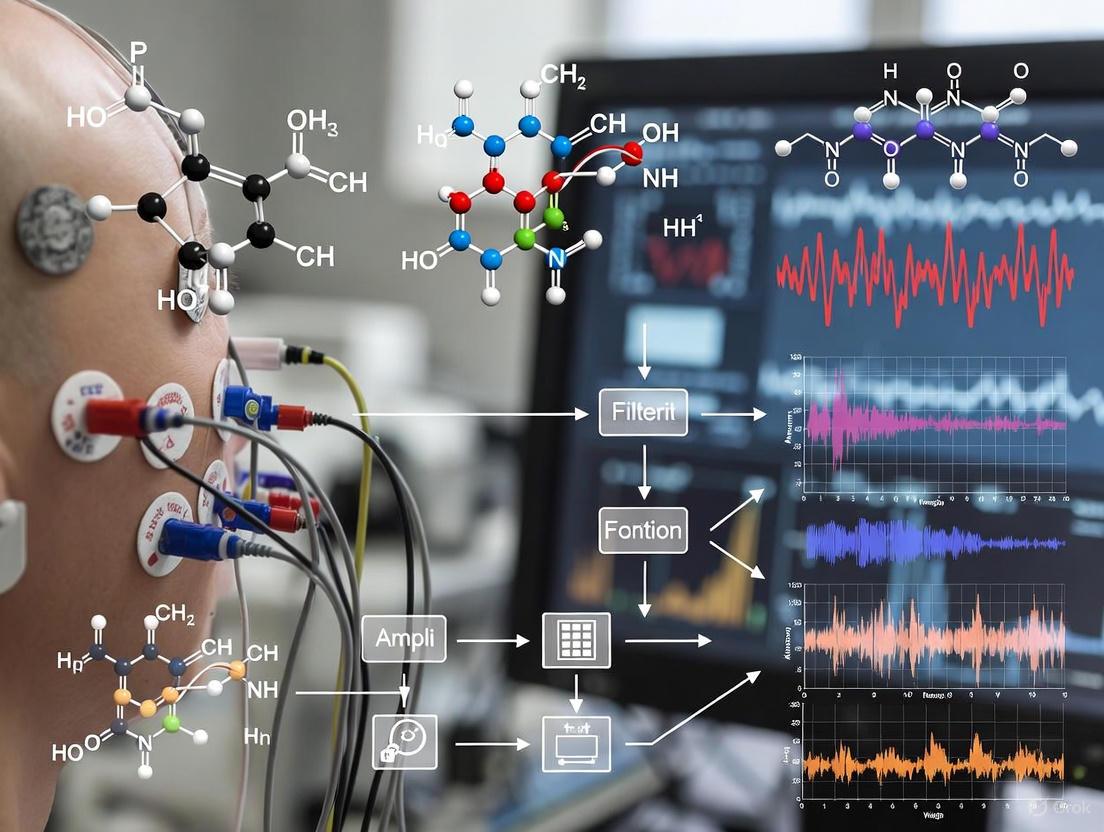

Core Principles of EEG-BCI Systems

A typical EEG-BCI system operates through a structured pipeline consisting of four consecutive stages: signal acquisition, processing (preprocessing and feature extraction), classification, and output with feedback [4] [2]. The system's effectiveness hinges on the interdependent relationship between sophisticated signal acquisition techniques and well-designed BCI paradigms that encode user intentions into distinguishable brain signal patterns [4].

Table 1: Core Components of an EEG-BCI System

| System Component | Primary Function | Key Technologies/Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Acquisition | Records electrical brain activity from the scalp. | EEG electrodes (e.g., Ag-AgCl), amplifiers, Analog-to-Digital Converters (ADC), international 10-20 placement system [3]. |

| Preprocessing | Enhances signal quality by removing noise and artifacts. | Band-pass filtering, Independent Component Analysis (ICA), Wavelet Transform (WT), Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) [2] [3]. |

| Feature Extraction | Identifies and isolates discriminative patterns in the EEG signal. | Power Spectral Density (PSD), Common Spatial Patterns (CSP), Riemannian Geometry, Wavelet Transform [5] [2]. |

| Classification | Translates extracted features into device control commands. | Machine Learning (SVM, Random Forest), Deep Learning (CNN, LSTM, Hybrid CNN-LSTM) [5] [6]. |

| Output & Feedback | Executes the command and provides sensory feedback to the user. | Robotic arms, spellers, visual/auditory/haptic feedback displays [4] [7]. |

The following diagram illustrates the sequential workflow and data flow in a standard closed-loop BCI system:

Origins and Types of EEG Signals in BCI

EEG signals originate from the post-synaptic potentials of cortical neurons [3]. When large populations of neurons fire synchronously, the resulting electrical currents can be detected on the scalp. These signals are inherently weak, typically in the microvolt (µV) range, and have limited spatial resolution due to the blurring effect of the skull and other tissues [4] [3]. EEG signals for BCI applications can be broadly categorized into two types:

- Natural (Spontaneous) Signals: These are ongoing, self-regulated brain oscillations not directly triggered by an external stimulus. They are modulated by changes in cognitive or mental state [3].

- Event-Related Potentials (ERPs): These are brain responses that are time-locked to specific sensory, cognitive, or motor events. They are typically embedded within the ongoing EEG activity [3].

Table 2: Primary EEG Rhythms and BCI-Relevant Signals

| Signal Type | Frequency Band | Neurophysiological Origin & Role in BCI |

|---|---|---|

| Delta (δ) | 0.5 - 4 Hz | Associated with deep sleep; less common in active BCI paradigms [3]. |

| Theta (θ) | 4 - 8 Hz | Linked to drowsiness, meditation, and memory processing [3]. |

| Alpha (α) | 8 - 13 Hz | Originates from the occipital lobe during relaxed wakefulness with eyes closed; used in neurofeedback [4] [3]. |

| Beta (β) | 13 - 30 Hz | Associated with active, alert thinking and motor cortex activity; suppressed during motor imagery (Event-Related Desynchronization) [4] [3]. |

| Gamma (γ) | >30 Hz | Involved in higher cognitive processing and sensory integration [3]. |

| Motor Imagery (MI) | Mu (~8-12 Hz) & Beta Rhythms | Induces Event-Related Desynchronization/Synchronization (ERD/ERS) in the sensorimotor cortex during imagined movement without execution [4] [5]. |

| P300 Potential | — | A positive deflection in EEG ~300ms after a rare, task-relevant stimulus; used in evoked potential spellers [4]. |

| Steady-State Visual Evoked Potential (SSVEP) | — | A stable periodic response in the visual cortex elicited by a repetitive visual stimulus (e.g., a flickering light) [8]. |

Major BCI Paradigms and Experimental Protocols

BCI paradigms are theoretical frameworks that define the specific mental tasks or external stimuli used to elicit distinguishable brain signal patterns [4]. Well-designed paradigms are crucial for enhancing the strength and detectability of the user's intention.

Motor Imagery (MI) Paradigm

Motor Imagery involves the mental simulation of a motor action without any physical execution [4] [5] [6]. This mental rehearsal activates neural pathways in the primary motor cortex, premotor cortex, and supplementary motor area, similar to those involved in actual movement, leading to characteristic changes in mu (8-12 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) rhythms known as Event-Related Desynchronization (ERD) and Synchronization (ERS) [4]. For example, imagining left-hand movement typically causes ERD in the right motor cortex, and vice versa [4].

Detailed Experimental Protocol (MI):

- Participants: Recruit healthy, right-handed subjects with no history of neurological disorders. Informed consent is mandatory [9] [7].

- Setup & Equipment: Use a multi-channel EEG system (e.g., 64-channel cap following the international 10-20 system) [9]. Ensure proper electrode-scalp contact with conductive gel.

- Paradigm Design: A single trial typically lasts 7-8 seconds [9] [7]:

- Fixation Period (1-2 s): A cross is displayed to focus the subject's attention.

- Cue Presentation (1-1.5 s): A visual or auditory cue indicates the specific MI task (e.g., left hand, right hand, foot) [9].

- Motor Imagery Period (4 s): The subject performs the cued MI task without moving.

- Rest Period (2 s): A blank screen allows the subject to relax before the next trial [9].

- Data Collection: Multiple sessions over different days are recommended to account for inter-session variability. Each session should contain multiple blocks (e.g., 5 blocks) with a sufficient number of trials per class (e.g., 40 trials per block for a 2-class paradigm) [9] [7].

P300 Paradigm

The P300 is an event-related potential characterized by a positive peak in the EEG signal approximately 300 milliseconds after an infrequent or significant stimulus is presented amidst a stream of standard stimuli [4]. This "oddball" paradigm is most famously implemented in the P300 speller, where the user focuses attention on a target character within a matrix of flashing characters. The P300 response is elicited when the desired character flashes, allowing the system to identify the user's choice [4].

Steady-State Visual Evoked Potential (SSVEP) Paradigm

SSVEPs are stable, periodic neural oscillations elicited in the visual cortex when a user gazes at a visual stimulus flickering at a fixed frequency (typically between 6-60 Hz) [8]. The resulting EEG signals show a strong peak at the fundamental frequency of the stimulus (and its harmonics). In an SSVEP-based BCI, users select commands by gazing at different flickering targets, each associated with a unique frequency. This paradigm is known for its high signal-to-noise ratio and high information transfer rate [8].

Detailed Experimental Protocol (SSVEP):

- Stimulus Design: Implement a multi-target visual speller (e.g., a 40-target QWERTY keyboard layout) using a sampled sinusoidal stimulation method on a standard computer monitor with a 60 Hz refresh rate [8].

- Procedure: Instruct participants to focus their gaze on a single target cued at the beginning of each trial. The trial length can vary but is often set to 5 seconds for offline calibration [8].

- Data Recording: Record EEG data from occipital and parietal sites (e.g., O1, O2, Oz, Pz) where SSVEP responses are strongest.

Signal Processing and Classification Methodologies

The raw EEG signal is contaminated with noise and artifacts, making advanced processing essential for reliable BCI operation.

Preprocessing and Feature Extraction

- Preprocessing: The primary goal is to enhance the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR). Standard techniques include:

- Filtering: Applying band-pass filters (e.g., 8-30 Hz for MI) to isolate frequency bands of interest [2] [3].

- Artifact Removal: Using algorithms like Independent Component Analysis (ICA) to separate and remove artifacts from eye blinks, muscle movement, and cardiac activity [2] [3].

- Other Techniques: Downsampling to reduce computational load and normalization [2].

- Feature Extraction: This step transforms the preprocessed signal into discriminative features for classification.

Classification Algorithms

Classification algorithms map the extracted features to specific user intention classes.

Table 3: Classification Algorithms in EEG-BCI

| Algorithm Category | Specific Methods | Reported Performance | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Machine Learning | Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | RF achieved 91% accuracy on a PhysioNet MI dataset [5]. | Robust for smaller datasets; widely used for MI and P300. |

| Deep Learning | Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) | CNN: 88.18% accuracy; LSTM: 16.13% accuracy on same dataset [5]. | Automates feature extraction; requires large datasets. |

| Hybrid Deep Learning | CNN-LSTM | 96.06% accuracy, surpassing individual models [5]. | Captures both spatial (CNN) and temporal (LSTM) features in EEG. |

The following diagram visualizes the complete signal processing and classification pipeline:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details essential materials, datasets, and software tools crucial for conducting EEG-BCI research.

Table 4: Essential Resources for EEG-BCI Research

| Resource Category | Specific Item/Name | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Public Datasets | "PhysioNet EEG Motor Movement/Imagery Dataset" [5] | A benchmark dataset for developing and validating MI-BCI classification algorithms. |

| "BETA" (Benchmark database Towards BCI Application) [8] | A large-scale SSVEP database with 70 subjects and 40 targets, designed for real-world application testing. | |

| "WBCIC-MI" (World Robot Conference Contest) [9] | A high-quality, multi-day MI dataset from 62 subjects, ideal for studying cross-session variability. | |

| Hardware & Acquisition | "Neuracle" EEG System [9] | Example of a modern, portable wireless EEG system with high signal stability. |

| Ag-AgCl (Silver/Silver Chloride) Electrodes [3] | The most commonly used electrode type for high-fidelity EEG signal acquisition. | |

| Software & Algorithms | "EEGNet", "DeepConvNet" [9] | Established deep learning architectures for EEG decoding, often used as benchmarks. |

| Riemannian Geometry Toolboxes [7] | Software packages for classifying EEG covariance matrices on a Riemannian manifold, offering high accuracy. | |

| Experimental Aids | International 10-20 System [3] | A standardized method for placing EEG electrodes on the scalp to ensure consistency across studies. |

| Sampled Sinusoidal Stimulation Method [8] | A technique for generating precise visual flickers for SSVEP paradigms on standard monitors. | |

| Bis(cyclopentadienyl)vanadium chloride | Bis(cyclopentadienyl)vanadium Chloride | Cp2VCl2 | RUO | Bis(cyclopentadienyl)vanadium chloride (Cp2VCl2) is a key organovanadium catalyst and precursor. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 2-(Hydroxy-phenyl-methyl)-cyclohexanone | 2-(Hydroxy-phenyl-methyl)-cyclohexanone, CAS:13161-18-7, MF:C13H16O2, MW:204.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, EEG-BCI technology faces several challenges. Variability in EEG signals across sessions and individuals remains a major obstacle to robust performance [9]. The lack of standardization in protocols, including user training and interface design, hinders reproducibility and comparison between studies [10] [6]. Furthermore, the translation of laboratory prototypes into clinically viable and user-friendly systems requires the development of portable, low-power devices with fewer EEG channels [6].

Future research is increasingly focused on leveraging Artificial Intelligence (AI) to create more adaptive and accurate systems [5] [6]. There is a growing emphasis on multimodal fusion, combining EEG with other signals like fNIRS or EOG to improve robustness [6]. A critical frontier is the development of effective user training protocols, including novel feedback visualization methods that help users learn to modulate their brain activity more effectively [10] [7]. Finally, coordinated efforts to create large, standardized, open-access datasets are essential for accelerating innovation and clinical translation [6] [9].

Comparative Analysis of Invasive vs. Non-Invasive BCI Modalities

Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) represent a revolutionary technology that enables direct communication between the brain and external devices, bypassing conventional neuromuscular pathways [2]. This field has evolved from basic neuroscience research into a rapidly advancing neurotechnology with profound implications for restoring function in patients with neurological deficits and enhancing human-computer interaction [11]. BCIs are broadly categorized into two distinct modalities based on their proximity to neural tissue: invasive systems requiring surgical implantation and non-invasive systems that measure brain activity externally [12] [13].

The fundamental distinction between these modalities lies in their signal acquisition methodologies, which directly determine their spatial resolution, temporal resolution, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and potential clinical applications [11] [12]. Invasive BCIs interface directly with cortical tissue or are placed on the cortical surface, capturing high-fidelity neural signals including single-unit activity and local field potentials [14] [12]. Non-invasive approaches, particularly electroencephalography (EEG), measure electrical potentials through the skull and scalp, providing a safer and more accessible alternative albeit with reduced signal resolution [2] [3].

Understanding the technical capabilities, limitations, and appropriate applications of each modality is crucial for researchers, clinicians, and technology developers working in neural engineering. This review provides a comprehensive technical comparison of invasive and non-invasive BCI modalities, with particular emphasis on signal processing pipelines, experimental methodologies, and emerging innovations that are shaping the future of brain-computer interfacing.

Fundamental Technical Specifications

The performance characteristics of invasive and non-invasive BCIs differ significantly across multiple parameters, influencing their suitability for specific applications and research contexts.

Table 1: Comparative Technical Specifications of BCI Modalities

| Parameter | Invasive BCI | Non-Invasive BCI (EEG) |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Micrometer to millimeter scale [12] | Centimeter scale [2] |

| Temporal Resolution | Millisecond (~1 ms) [12] | Millisecond-level [2] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | High [12] | Low to moderate [2] |

| Signal Types Obtained | Action potentials (spikes), Local Field Potentials (LFP) [12] | EEG rhythms (δ, θ, α, β, γ), Event-Related Potentials (ERPs) [3] |

| Typical Electrode Count | 64-1000+ channels [15] | 32-256 channels [3] |

| Key Advantages | High-fidelity signals, precise spatial localization [12] | Safety, accessibility, no surgical risk [2] [13] |

| Primary Limitations | Surgical risk, long-term stability, biocompatibility [2] [12] | Low spatial resolution, vulnerability to artifacts [2] [3] |

| Target Applications | High-precision control, speech decoding, complex device control [11] [14] | Basic communication, neurofeedback, rehabilitation, cognitive monitoring [2] [16] |

Table 2: Signal Acquisition Technologies in BCI Research

| Technology | Interface Type | Recorded Signals | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microelectrode Arrays (MEA) | Invasive (intracortical) | Single/multi-unit activity, LFP [12] | Single neuron level [12] | ~1 ms [12] |

| Electrocorticography (ECoG) | Invasive (subdural/epi-dural) | Local field potentials [12] | Millimeter [11] | Millisecond [11] |

| Stereoelectroencephalography (sEEG) | Invasive (depth electrodes) | Local field potentials from deep structures [14] | Millimeter [14] | Millisecond [14] |

| Electroencephalography (EEG) | Non-invasive | Scalp potentials [2] | Centimeter [2] | Millisecond [2] |

| Functional Ultrasound (fUS) | Minimally invasive | Hemodynamic response [11] | ~100 micrometers [11] | ~2-10 Hz [11] |

| Digital Holographic Imaging | Non-invasive | Neural tissue deformation [17] | High (theoretical) [17] | Unknown [17] |

BCI Signal Processing Framework

The core functionality of any BCI system relies on a multi-stage processing pipeline that transforms raw neural signals into actionable commands. While the fundamental stages are similar across modalities, the specific techniques and challenges differ significantly between invasive and non-invasive approaches.

Signal Acquisition and Preprocessing

Invasive BCI Signal Acquisition involves direct measurement of neural activity from cortical tissue or surface. Microelectrode Arrays (MEAs), such as the Utah array, penetrate the cortex to record action potentials from individual neurons or small neuronal populations [12]. Electrocorticography (ECoG) electrodes are placed on the cortical surface (subdural or epidural) to measure local field potentials with higher spatial resolution and broader coverage than MEAs [11]. Stereoelectroencephalography (sEEG) utilizes depth electrodes inserted into deep brain structures to record from specific subcortical regions [14].

Non-Invasive BCI Signal Acquisition primarily utilizes electroencephalography (EEG) with electrodes placed on the scalp according to standardized systems like the 10-20 placement system [3]. EEG records electrical potentials generated by synchronized postsynaptic activity in cortical neurons, attenuated by passage through cerebrospinal fluid, skull, and scalp [2]. Emerging non-invasive technologies include digital holographic imaging, which detects nanometer-scale tissue deformations associated with neural activity [17].

Preprocessing Challenges and Techniques differ significantly between modalities:

Invasive BCI Preprocessing: Focuses on spike sorting to identify activity from individual neurons, common average referencing to reduce common noise, and filtering to isolate specific frequency bands in local field potentials [12]. The primary challenges include signal drift over time and tissue response to implanted electrodes [2].

Non-Invasive BCI Preprocessing: Requires extensive artifact removal to mitigate contamination from ocular movements, muscle activity, cardiac signals, and environmental noise [2] [3]. Standard techniques include:

- Filtering: Digital filters (FIR, IIR) to extract specific frequency bands [2]

- Independent Component Analysis (ICA): Separates mixed signals into statistically independent components for artifact identification [2]

- Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA): Removes electromyographic interference [2]

- Wavelet Transform: Simultaneously analyzes signals in time and frequency domains for noise identification [2]

Feature Extraction and Decoding Algorithms

Feature Extraction Methods transform preprocessed neural signals into meaningful representations for classification:

Invasive BCI Features: Include firing rates of individual neurons, temporal patterns of spike trains, spectral power in local field potential bands, and cross-channel correlations [12]. These features capture detailed information about movement intention, kinematic parameters, and cognitive states.

Non-Invasive BCI Features: Focus on rhythmic activity in specific frequency bands (delta, theta, alpha, beta, gamma), event-related potentials (P300, N200), and signal complexity measures [3]. Extraction methods include:

- Fast Fourier Transform (FFT): Computes power spectral density but assumes signal stationarity [3]

- Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT): Provides time-frequency representation with fixed resolution [3]

- Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT): Offers multi-resolution analysis suitable for non-stationary EEG signals [3]

Decoding Algorithms map extracted features to output commands:

Invasive BCI Decoders: Employ population vector algorithms, optimal linear estimators, Kalman filters, and Bayesian decoders to reconstruct continuous movement parameters with high precision [12]. Recent approaches utilize deep learning models for speech decoding from cortical activity [14].

Non-Invasive BCI Decoders: Use machine learning classifiers including Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) for discrimination between mental states [2] [16]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have shown promising results for EEG-based classification tasks [16].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Invasive BCI Motor Control Experiments

Motor control experiments using invasive BCIs typically involve participants with tetraplegia due to spinal cord injury or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [14]. The experimental protocol follows a structured approach:

Surgical Implantation: Participants undergo craniotomy for placement of microelectrode arrays (e.g., Utah array) in hand/arm areas of primary motor cortex or ECoG grids over sensorimotor regions [14] [12]. The implantation target is determined through pre-surgical functional mapping.

Signal Acquisition Setup: Neural signals are amplified, digitized (typically at 30 kHz for spikes and 1-2 kHz for LFPs), and transmitted via percutaneous connectors or wireless systems [12].

Calibration Phase: Participants observe or imagine performing specific movements while neural activity is recorded to establish initial decoding parameters [12]. This phase typically lasts 20-30 minutes.

Closed-Loop Control Training: Participants practice controlling external devices (computer cursors, robotic arms) with real-time visual feedback. Decoder parameters are refined through adaptive algorithms during these sessions [12].

Performance Metrics: Success is evaluated using metrics such as target acquisition time, path efficiency, information transfer rate (bits/min), and completion rates for functional tasks [14].

Recent studies have demonstrated that individuals with paralysis can achieve multidimensional control of robotic arms and computer interfaces with performance approaching able-bodied function [14] [12].

Protocol for Non-Invasive BCI Communication Experiments

Non-invasive BCI communication systems typically utilize EEG-based paradigms with healthy participants or individuals with neuromuscular disorders:

EEG Setup: Electrodes are positioned according to the international 10-20 system, with specific focus on regions relevant to the experimental paradigm (e.g., motor imagery: C3, C4, Cz; P300: Pz, Cz, Fz) [3]. Impedance is kept below 5 kΩ to ensure signal quality.

Experimental Paradigms:

- Motor Imagery (MI): Participants imagine limb movements without physical execution, generating sensorimotor rhythms (mu/beta rhythms) that are classified for device control [16]. Trials typically last 4-8 seconds with rest periods between trials.

- P300 Speller: Rare target stimuli interspersed with frequent non-target stimuli elicit a P300 event-related potential, allowing selection of characters from a matrix [3]. The inter-stimulus interval is typically 125-250 ms.

- Steady-State Visually Evoked Potentials (SSVEP): Visual stimuli flickering at specific frequencies elicit oscillations in visual cortex that can be used for control [2].

Signal Processing Pipeline: Data is filtered (e.g., 8-30 Hz for MI, 0.1-20 Hz for P300), segmented into epochs, and processed with artifact removal algorithms before feature extraction and classification [3].

Validation: Performance is assessed through accuracy, information transfer rate, and bit rate. Cross-validation is employed to ensure generalizability of results [16].

Table 3: Standard Experimental Parameters for BCI Paradigms

| Parameter | Invasive Motor Control | Non-Invasive Motor Imagery | P300 Speller |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | Patients with tetraplegia (SCI, ALS) [14] | Healthy volunteers or patients [16] | Healthy volunteers or patients [3] |

| Session Duration | 2-4 hours [14] | 1-2 hours [16] | 1-2 hours [3] |

| Trial Structure | Continuous operation with periodic rest | 4-8 second trials with inter-trial rest [16] | Rapid serial visual presentation [3] |

| Feedback Type | Visual (cursor/robot movement) [12] | Visual (cursor movement, bar graph) [16] | Visual (selected character highlight) [3] |

| Typical Channels | 96-256 recording sites [14] | 16-64 electrodes [16] | 8-32 electrodes [3] |

| Data Sampling Rate | 30 kHz (spikes), 2 kHz (LFP) [12] | 250-1000 Hz [3] | 250-500 Hz [3] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for BCI Experimentation

| Category | Item | Specification/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Electrodes & Implants | Utah Array | 96-100 microelectrodes for intracortical recording [15] |

| ECoG Grids | Subdural grid electrodes with 32-256 contacts [12] | |

| sEEG Electrodes | Depth electrodes with 8-16 contacts for deep brain recording [14] | |

| Ag/AgCl EEG Electrodes | Scalp electrodes with chloride coating for stable potential [3] | |

| Signal Acquisition | Neural Signal Amplifier | High-input impedance, low-noise amplification [3] |

| Analog-to-Digital Converter | 16-24 bit resolution, sampling rates to 30 kHz [3] | |

| Reference & Ground Electrodes | Essential for common-mode noise rejection [3] | |

| Software & Algorithms | EEGLAB/FieldTrip | MATLAB toolboxes for EEG analysis [11] |

| BCI2000/OpenVibe | General-purpose BCI software platforms [11] | |

| Kalman Filter Decoder | Standard for continuous trajectory decoding in invasive BCIs [12] | |

| Common Spatial Patterns | Feature extraction for motor imagery EEG [16] | |

| Experimental Materials | International 10-20 System Cap | Standardized electrode placement [3] |

| Electrolyte Gel | Reduces impedance at scalp-electrode interface [3] | |

| Visual Stimulation Display | Presents paradigms for P300, SSVEP, neurofeedback [3] | |

| Dysprosium telluride | Dysprosium Telluride (Dy₂Te₃) for Advanced Research | High-purity Dysprosium Telluride for energy storage and electrocatalysis research. For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or personal use. |

| (E)-1-Phenyl-1-butene | (E)-1-Phenyl-1-butene, CAS:1005-64-7, MF:C10H12, MW:132.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

Innovations in Invasive BCI Technologies

The invasive BCI landscape is rapidly evolving with multiple companies and research institutions developing next-generation interfaces:

Neuralink is developing an ultra-high-bandwidth implantable chip with thousands of micro-electrodes threaded into the cortex by a robotic surgeon [15]. The coin-sized implant, sealed in the skull, aims to record from more neurons than prior devices. As of 2025, the company reported five individuals with severe paralysis using Neuralink to control digital and physical devices with their thoughts [15].

Synchron employs an endovascular approach with the Stentrode device delivered via blood vessels and lodged in the motor cortex's draining vein [15]. This method avoids craniotomy entirely and has enabled patients with paralysis to control computers for texting and communication [15].

Precision Neuroscience is developing an ultra-thin electrode array designed to be placed between the skull and brain with minimal invasion [15]. Their flexible "brain film" conforms to the cortical surface without penetrating brain tissue, potentially offering high-resolution signals with reduced risk [15].

Paradromics specializes in high-channel-count implants (421 electrodes) with integrated wireless transmission, focusing initially on speech restoration for people who cannot talk [15].

Advances in Non-Invasive BCI Technologies

Non-invasive BCI research is addressing fundamental limitations through novel signal detection approaches and enhanced processing algorithms:

Digital Holographic Imaging developed by Johns Hopkins APL represents a breakthrough in non-invasive, high-resolution recording of neural activity [17]. This technique detects nanometer-scale tissue deformations that occur during neural activity, potentially providing a novel signal source that bypasses the limitations of electrical recording through the skull.

Hybrid BCI Systems combine EEG with other modalities such as fNIRS (functional near-infrared spectroscopy) or eye tracking to improve accuracy and robustness [11]. These systems leverage complementary information from different signal types to enhance classification performance.

Advanced Signal Processing utilizing deep learning approaches is increasingly applied to non-invasive BCI data. Convolutional Neural Networks with attention mechanisms (FCNNA) have shown promising results for optimal channel selection and multiclass motor imagery classification [16]. Transfer learning techniques are being developed to address the challenge of inter-subject variability in EEG patterns.

The comparative analysis of invasive and non-invasive BCI modalities reveals a clear trade-off between signal fidelity and practical accessibility. Invasive BCIs provide unparalleled spatial and temporal resolution, enabling complex tasks such as robotic arm control and speech decoding, but require substantial surgical intervention and carry associated risks [14] [12]. Non-invasive approaches, particularly EEG-based systems, offer safety and immediate applicability but face fundamental limitations in signal quality that restrict their precision and range of applications [2] [3].

The future trajectory of BCI technology points toward two parallel development paths: refinement of minimally invasive approaches that balance risk and capability, and fundamental innovations in non-invasive signal detection that may overcome current physical limitations [15] [17]. For researchers and clinicians, selection between modalities must consider the specific application requirements, user population, and practical constraints. As both approaches continue to advance, the gap between invasive and non-invasive performance may narrow, potentially expanding the impact of BCI technologies across medical, communicative, and assistive domains.

A Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) establishes a direct communication pathway between the human brain and an external device [18]. The core of this technology is a processing pipeline that translates raw neural signals into actionable commands. This pipeline is universally comprised of three critical stages: signal acquisition, where brain activity is measured; preprocessing, where the raw signals are cleaned and prepared; and classification, where the cleaned signals are decoded into user intent [18]. As of 2025, BCI technology is transitioning from laboratory research to real-world applications, driven by advancements in non-invasive wearables and sophisticated machine learning [15] [18]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these core components, framed within contemporary EEG signal processing research for an audience of scientists and drug development professionals.

Signal Acquisition

The acquisition phase is the foundational first step, responsible for capturing electrical brain activity. The choice of acquisition modality determines the fidelity, spatial resolution, and overall capability of the BCI system.

Acquisition Modalities

Brain signals can be acquired using either invasive or non-invasive techniques. Electroencephalography (EEG), a non-invasive method, is the most prevalent modality due to its safety, portability, and cost-effectiveness [3] [18]. EEG records voltage fluctuations on the scalp resulting from neuronal activity, typically in the microvolt range (µV) [3]. While its temporal resolution is high, its spatial resolution is limited because the signals are attenuated by the skull and scalp [3]. In contrast, invasive techniques such as Electrocorticography (ECoG), which involves placing electrodes directly on the surface of the brain, provide a vastly superior signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and spatial resolution [15] [3]. Companies like Neuralink, Paradromics, and Precision Neuroscience are pioneering ultra-high-bandwidth implantable devices that record from thousands of neurons to restore function for patients with severe paralysis [15] [19].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary BCI Acquisition Modalities

| Modality | Invasiveness | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Applications/Players |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEG | Non-invasive | Low (cm) | High (ms) | Motor Imagery, P300 spellers, cognitive monitoring |

| ECoG | Invasive (surface) | High (mm) | High (ms) | Epilepsy focus mapping, high-fidelity control [3] |

| Microelectrode Arrays | Invasive (penetrating) | Very High (µm) | High (ms) | Neuralink, Paradromics, Blackrock Neurotech [15] |

| Endovascular (Stentrode) | Minimally Invasive | Moderate | High | Synchron [15] |

Acquisition Hardware and Standards

In EEG-based systems, the electrical signals are captured via electrodes placed on the scalp according to standardized systems like the international 10–20 placement system to ensure consistency across individuals and sessions [3]. Modern electrodes are typically composed of Ag-AgCl (Silver/Silver Chloride) and can be wet, dry, or foam-based [3]. The weak analog signals (µV) are then passed to an amplifier, which boosts them to a usable level while maintaining signal integrity through high input impedance and low-noise characteristics [3]. Finally, an Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC) samples the continuous signal at a specific frequency (e.g., 250, 500, or 1000 Hz), quantizes it (e.g., with 16-bit resolution), and encodes it into a digital format for subsequent processing [3].

For research and development, integrated software platforms are essential. Lab Streaming Layer (LSL) has emerged as a critical open-source tool for synchronously recording EEG and other data streams (e.g., event markers, other biosignals) into a unified data file (XDF format) [20]. This is vital for building temporally aligned datasets for model training. Furthermore, toolkits like BCI2000 and its VisualizeBCI2000 extension provide modular frameworks for real-time data acquisition, stimulus presentation, and powerful 3D visualization of brain signals, facilitating both basic research and clinical application development [21].

Signal Preprocessing

Raw EEG signals are notoriously noisy and non-stationary. The preprocessing stage is therefore critical for enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and extracting clean neural data for robust classification.

The Preprocessing Workflow

This stage involves a series of steps designed to remove artifacts and prepare the data for feature extraction. A systematic workflow is essential for reproducible results.

Diagram 1: Core BCI preprocessing workflow.

Detailed Preprocessing Techniques

- Filtering: This is a fundamental step to isolate frequencies of interest. A band-pass filter (e.g., 0.5-40 Hz) is typically applied. A high-pass filter removes low-frequency drifts, while a low-pass filter eliminates high-frequency noise like muscle activity. Research from 2025 shows that higher high-pass filter cutoffs (e.g., 1 Hz over 0.1 Hz) can consistently increase decoding performance, though this must be balanced against potential signal distortion [22].

- Re-referencing: The original EEG signal is measured relative to a single reference electrode (often Cz). Re-referencing transforms the data to a common average or mastoid reference to reduce the bias introduced by the original reference site [22].

- Artifact Removal: This step targets noise from non-brain sources.

- Ocular artifacts (from eye blinks and movements) and muscle artifacts (from jaw clenching) are often an order of magnitude stronger than neural signals [3] [18].

- Independent Component Analysis (ICA) is a widely used method to identify and remove these artifacts [22]. However, a 2025 multiverse analysis cautions that while artifact correction is crucial for interpretability, it can reduce decoding performance if the artifacts are systematically correlated with the task, as the classifier may be inadvertently leveraging the structured noise to make decisions [22].

- Sub-band Extraction: Neural information is encoded in specific frequency bands. Extracting these sub-bands is a key feature engineering step. Common methods include:

- Finite Impulse Response (FIR) / Infinite Impulse Response (IIR) Filters: Offer precise control and are computationally efficient, making them suitable for real-time BCI [3].

- Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT): Provides an optimal balance between time and frequency resolution for non-stationary signals like EEG and is highly effective for capturing transient features [3] [5].

Table 2: Impact of Preprocessing Choices on Decoding Performance (2025 Study)

| Preprocessing Step | Choice A | Choice B | Impact on Decoding Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Pass Filter (HPF) | 0.1 Hz Cutoff | 1.0 Hz Cutoff | Higher cutoff increased performance [22] |

| Artifact Correction | ICA & Autoreject | No Correction | Correction generally decreased performance* [22] |

| Baseline Correction | Long Interval | Short/No Interval | Longer interval increased performance (EEGNet) [22] |

| Detrending | Linear Detrending | No Detrending | Increased performance (Time-resolved decoding) [22] |

Note: While artifact correction can lower performance metrics, it is critical for model validity and interpretability, as it prevents the classifier from learning from structured noise rather than the neural signal [22].

Signal Classification

The final stage involves using machine learning models to map the preprocessed EEG signals to specific user intents or commands, such as "move left" or "select letter A."

Traditional and Deep Learning Models

The choice of classifier depends on the BCI paradigm and the nature of the extracted features.

- Traditional Machine Learning (ML) Models: For well-defined features, models like Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) are commonly used due to their simplicity and computational efficiency [5] [23]. In a 2025 study on motor imagery classification, Random Forest achieved a high accuracy of 91% using traditional feature extraction [5].

- Deep Learning (DL) Models: Deep learning models can automatically learn relevant features from raw or minimally processed data, reducing the need for manual feature engineering.

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are adept at extracting spatial features from EEG data arranged in a channel-topography grid [5].

- Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks excel at modeling the temporal dependencies in time-series EEG data [5].

- Hybrid Models (CNN-LSTM): A 2025 study demonstrated that a hybrid CNN-LSTM model, which leverages the spatial feature extraction of CNNs and the temporal modeling of LSTMs, significantly outperformed individual models, achieving a state-of-the-art accuracy of 96.06% for motor imagery classification [5].

An Advanced Hybrid Classification Pipeline

To achieve the highest accuracy, modern research employs complex pipelines that integrate advanced feature extraction with sophisticated models.

Diagram 2: Advanced hybrid classification pipeline.

This pipeline incorporates several cutting-edge techniques highlighted in 2025 research:

- Advanced Feature Extraction: Beyond simple band power, methods like Wavelet Transform and Riemannian Geometry on covariance matrices are used to capture complex time-frequency and manifold features of brain activity [5].

- Data Augmentation with GANs: To address the challenge of small, high-dimensional EEG datasets, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are employed to generate realistic synthetic EEG data. This balances datasets and improves model generalization [5] [23].

- Hybrid Model Training: The model is first pre-trained on the synthetic data and then fine-tuned on a smaller set of real-world recordings. This hybrid training approach has been shown to improve accuracy and robustness compared to training on real data alone [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers developing BCI pipelines, a suite of software tools and data resources is indispensable.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for BCI Development

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to BCI Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lab Streaming Layer (LSL) | Software Framework | Synchronized data acquisition from multiple hardware sources [20] | Foundation for building temporally aligned, multi-modal BCI datasets. |

| MNE-Python | Software Library | EEG/MEG data preprocessing, visualization, and analysis [22] | Industry-standard for implementing and testing preprocessing pipelines. |

| BCI2000 / VisualizeBCI2000 | Software Platform | A general-purpose research platform for BCI data acquisition, stimulus presentation, and online analysis [21] | Provides a modular environment for prototyping and real-time system testing. |

| EEGNet | Deep Learning Model | A compact convolutional neural network for EEG-based BCIs [22] | A standard baseline model for comparing classification performance across studies. |

| PhysioNet EEG Dataset | Data Resource | A publicly available dataset containing EEG recordings for motor movement/imagery tasks [5] | A benchmark dataset for training and validating new classification algorithms. |

| GANs for EEG | Methodology | Generation of synthetic EEG data for augmenting training sets [5] [23] | Critical for overcoming the data scarcity problem in deep learning for BCIs. |

| Ethyl 2-[4-(chloromethyl)phenyl]propanoate | Ethyl 2-[4-(chloromethyl)phenyl]propanoate, CAS:43153-03-3, MF:C12H15ClO2, MW:226.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 5-(Bromomethyl)thiophene-2-carbonitrile | 5-(Bromomethyl)thiophene-2-carbonitrile, CAS:134135-41-4, MF:C6H4BrNS, MW:202.07 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The BCI pipeline—comprising acquisition, preprocessing, and classification—forms the technical backbone of modern brain-computer communication. As of 2025, the field is characterized by a convergence of safer, higher-fidelity acquisition hardware and increasingly intelligent, data-driven software algorithms. Key trends shaping current research include the systematic optimization of preprocessing steps for decoding performance, the dominance of hybrid deep learning models like CNN-LSTM for state-of-the-art accuracy, and the use of synthetic data generated by GANs to overcome dataset limitations. For researchers and scientists, mastering the intricate relationships between these components—such as how a preprocessing choice can inadvertently aid or hamper a classifier—is paramount. The ongoing translation of BCIs from controlled labs to real-world clinical and consumer applications will continue to depend on rigorous, reproducible, and innovative advancements across all stages of this critical pipeline.

Electroencephalography (EEG)-based Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) establish a direct communication pathway between the human brain and external devices, translating brain activity into commands without using peripheral nerves or muscles [24]. These systems acquire brain signals, analyze them to extract meaningful features, and translate these features into outputs that accomplish the user's intent. The three most established paradigms in EEG-based BCI research are the P300 event-related potential, Steady-State Visual Evoked Potential (SSVEP), and Motor Imagery (MI) rhythms [25]. Each paradigm leverages distinct neural mechanisms and offers unique advantages and challenges, making them suitable for different applications ranging from communication and control to neurorehabilitation.

EEG signals are characterized by their non-stationary and noisy nature, often with low amplitude, necessitating sophisticated signal processing and pattern recognition techniques for reliable interpretation [24] [6]. The P300, SSVEP, and MI paradigms form the cornerstone of modern BCI research, driving innovations in assistive technologies for individuals with severe motor disabilities and exploring new frontiers in human-computer interaction [26] [24]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of these three major EEG paradigms, detailing their underlying neurophysiological principles, standard experimental protocols, signal processing methodologies, and performance metrics, framed within the broader context of BCI signal processing research.

Core Neurophysiological Principles and Signatures

P300 Event-Related Potential

The P300 is an endogenous event-related potential (ERP) component, meaning its occurrence is tied to cognitive processes rather than the physical attributes of a stimulus. It manifests as a positive deflection in the EEG signal approximately 250 to 400 milliseconds after an infrequent or psychologically significant stimulus is presented [27] [28]. Its amplitude is maximal at parietal–central electrode sites (e.g., Cz, Pz) [27]. The P300 is considered a neural signature of attention and decision-making; its amplitude reflects the allocation of attentional resources, while its latency corresponds to the speed of stimulus evaluation and classification [27]. In high-workload situations, P300 amplitude typically decreases, indicating a reallocation of cognitive resources toward primary task demands [27].

Steady-State Visual Evoked Potential (SSVEP)

SSVEPs are neural responses elicited by a visual stimulus flickering at a constant frequency. When a user focuses attention on such a stimulus, the visual cortex produces oscillatory EEG activity that is phase-locked to the stimulus frequency, often including harmonic components [29] [26]. This response is typically recorded from electrodes over the occipital lobe (O1, O2, Oz). A key advantage of SSVEPs is their high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Recent research explores stimulation in the beta frequency range (14–22 Hz) to minimize visual fatigue, a common issue with SSVEP paradigms that use lower frequencies [29].

Motor Imagery (MI) Rhythms

Motor Imagery involves the mental simulation of a movement without any physical execution. This cognitive process activates sensorimotor cortices, modulating specific brain rhythms [30] [6]. The key rhythms are the mu rhythm (8–12 Hz) and the beta rhythm (18–30 Hz). The event-related desynchronization (ERD) is a decrease in the power of these rhythms during motor imagery, associated with cortical activation. Conversely, event-related synchronization (ERS) is a power increase following the imagery [24]. These patterns are central to MI-based BCI control, allowing users to manipulate external devices through imagined movements.

Comparative Analysis of BCI Paradigms

Table 1: Comparative overview of the three major EEG-BCI paradigms.

| Paradigm | Neural Signature & Origin | Primary Electrode Locations | Key Applications | Major Advantages | Major Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P300 | Positive ERP ~300ms post-stimulus; Endogenous (cognitive) [27] [28]. | Cz, Pz (Parietal-Central) [27] [28]. | Spellers, clinical diagnostics, cognitive workload monitoring [27] [24]. | Minimal user training required [25]. | Requires averaging multiple trials, leading to slower communication speeds; Sensitive to noise and baseline EEG stability [28] [25]. |

| SSVEP | Oscillatory activity at stimulus frequency and harmonics; Exogenous/Endogenous (visual attention) [29] [26]. | O1, Oz, O2 (Occipital) [29] [26]. | High-speed spellers, mind-controlled robots, device control [29] [26]. | High SNR and Information Transfer Rate (ITR); Little training needed [29] [24]. | Can cause visual fatigue; Requires gaze control (for most systems); Risk of seizures in susceptible individuals [29] [25]. |

| Motor Imagery (MI) | ERD/ERS of mu/beta rhythms over sensorimotor cortex; Endogenous (kinesthetic imagination) [30] [24]. | C3, Cz, C4 (Sensorimotor) [30]. | Neurorehabilitation, robotic arm/device control, motor recovery therapy [30] [6]. | Does not require external stimuli; More natural, "self-paced" control [24]. | Requires significant user training; Subject to "BCI illiteracy" (15-30% of users) [30] [25]. |

Table 2: Typical performance metrics for the three paradigms.

| Paradigm | Typical Accuracy (%) | Typical Speed (Information Transfer Rate, ITR) | Number of Commands (Classes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| P300 | ~91.3% (with 5 repetitions) [26] | ~18.8 bits/min [26] | Can be high (e.g., 36 in a speller) [25] |

| SSVEP | Up to 96.7% (with machine learning) [31] | Up to 24.7 bits/min [26] | Can be high (e.g., 40-class systems) [29] |

| Motor Imagery (MI) | Up to 89.82% (with advanced methods) [32] | Varies widely with user proficiency | Typically low (2-4 classes) [6] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

P300 Speller Protocol

The classic P300 speller, developed by Farwell and Donchin, uses a 6x6 matrix of characters [24]. The user focuses on a target character while rows and columns of the matrix flash in a random sequence. Each flash of the row or column containing the target character serves as a rare, task-relevant stimulus, theoretically eliciting a P300. EEG epochs from -200 ms to 600-800 ms relative to each flash are extracted. Multiple epochs (e.g., 5-15 repetitions) are averaged to enhance the SNR before classification. A critical methodological consideration is baseline correction. Research shows that for rapid, continuous stimuli (e.g., 400 ms intervals), conventional baseline corrections (e.g., using a single time point) may be unstable. Time-range-averaged (e.g., 0-200 ms pre-stimulus) or multi-time-point baseline corrections are more effective for accurate P300 detection [28].

Figure 1: P300 experimental and processing workflow.

SSVEP Speller Protocol

In a typical SSVEP experiment, subjects view multiple visual stimuli (e.g., a 5x8 matrix of flickering boxes), each oscillating at a distinct frequency (e.g., from 14.0 Hz to 21.8 Hz in the beta range) [29]. The experiment is structured in blocks and trials. Each trial begins with a visual cue indicating the target, followed by a sustained flickering period (e.g., 5 seconds). The user must maintain gaze on the target during the flickering. The central challenge is accurately identifying the target frequency from the EEG. While canonical correlation analysis (CCA) is a standard zero-training method, machine learning approaches using features from wavelet decomposition (e.g., Db4) have achieved high accuracy (>96%) even with a single Oz channel [31].

Motor Imagery Classification Protocol

MI experiments involve cue-based trials where users imagine specific movements (e.g., left hand, right hand, feet) for a set duration (e.g., 4-5 seconds) [32] [30]. A major research focus is optimizing feature extraction and classification. The Common Spatial Pattern (CSP) algorithm is a gold-standard technique that maximizes the variance of one class while minimizing it for the other, leading to highly discriminative features [30]. Recent advanced methods involve synergistic preprocessing like the Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT) for non-stationary signals, followed by feature extraction using methods like Permutation Conditional Mutual Information Common Space Pattern (PCMICSP), and classification with classifiers like Back Propagation Neural Network (BPNN) optimized with bio-inspired algorithms like the Honey Badger Algorithm (HBA), achieving up to 89.82% accuracy [32]. Another significant challenge is reducing the number of electrodes required. Signal prediction methods using Elastic Net regression can estimate full-channel EEG from a few central channels, achieving ~78% accuracy with only 8 channels, which enhances practicality [30].

Figure 2: Motor imagery experimental and processing workflow.

Computational Approaches and Hybrid Systems

Signal Processing and AI Classification

The integration of artificial intelligence is pivotal for advancing all BCI paradigms.

- Motor Imagery: Deep learning models like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks are increasingly used for end-to-end classification from raw or preprocessed EEG [6]. A recent review found that 85% of studies on lower-limb MI used machine or deep learning classifiers like SVM, CNN, and LSTM [6].

- P300: Traditional methods rely on averaging and linear discriminant analysis, but newer approaches employ CNNs that can learn from single-trial data, reducing the need for extensive averaging and speeding up communication rates [28].

- SSVEP: Beyond CCA, machine learning classifiers such as Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) applied to extracted frequency features have demonstrated accuracies exceeding 96% [31].

Hybrid BCI Paradigms

Hybrid BCIs combine two or more paradigms to overcome the limitations of a single approach. A common combination is P300 and SSVEP [25]. For instance, a hybrid speller might use flickering stimuli that simultaneously evoke both SSVEP (due to the flicker) and P300 (due to an occasional shape or color change of the target). This dual elicitation can improve classification accuracy and robustness compared to either paradigm alone. One study demonstrated that a hybrid "Shape Changing and Flickering" paradigm achieved a higher SSVEP classification accuracy (90.63%) and a comparable P300 accuracy to a traditional "Flash and Flickering" hybrid paradigm, while being less annoying [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential tools and reagents for EEG-BCI research.

| Item | Function & Application | Technical Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| EEG Amplifier & Acquisition System | Records electrical potentials from the scalp. Fundamental for all EEG research. | Systems from Biosemi, g.tec, etc. Sampling rate ≥ 1024 Hz; 16-bit resolution or higher; Impedance checking capability [29] [24]. |

| Active Electrodes (Wet/Dry) | Sensors that make electrical contact with the scalp to measure brain signals. | Wet Ag/AgCl electrodes (gold standard). Dry electrodes (e.g., g.SAHARA, QUASAR) for faster setup, though may compromise signal quality in some setups [24]. |

| Electrode Caps/Gels | Holds electrodes in standard positions (10-20 system). Gel ensures stable, low-impedance connection. | Caps must accommodate varying head sizes/shapes. Electrode-skin impedance should be kept below 5-10 kΩ for optimal signal quality [30] [24]. |

| Visual Stimulation Display | Presents flickering (SSVEP) or flashing (P300) stimuli to the user. | High refresh rate monitors (≥120 Hz) critical for precise SSVEP frequency control [29]. |

| Stimulus Presentation Software | Controls the timing and sequence of visual/auditory stimuli. | Software like Psychophysics Toolbox (PTB-3) in MATLAB for millisecond-precise control [29]. |

| Signal Processing & BCI Software Platform | Provides environment for real-time data processing, feature extraction, and model training/classification. | Platforms like OpenViBE, BCILAB, or custom scripts in MATLAB/Python [26] [25]. |

| Validation Datasets | Standardized public datasets for developing and benchmarking new algorithms. | e.g., EEGMMIDB (for MI), CHB-MIT (for epilepsy), BCI Competition datasets, and 40-class SSVEP datasets [32] [29] [31]. |

| Methyl 4-chloroquinoline-7-carboxylate | Methyl 4-chloroquinoline-7-carboxylate, CAS:178984-69-5, MF:C11H8ClNO2, MW:221.64 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2,3-Dichloro-4,5-difluorobenzonitrile | 2,3-Dichloro-4,5-difluorobenzonitrile|CAS 112062-59-6 | 2,3-Dichloro-4,5-difluorobenzonitrile (CAS 112062-59-6) is a key fluorinated nitrile building block for medicinal chemistry research. This product is for Research Use Only. Not for human or animal use. |

Global Market Trends and Growth Projections in BCI Technology

The global Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) market is experiencing transformative growth, propelled by advancements in neurotechnology and artificial intelligence. Valued at approximately USD 2.40 billion in 2025, the market is projected to reach USD 6.16 billion by 2032, expanding at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 14.4% [33]. This growth is primarily driven by the rising prevalence of neurological disorders, expanding applications beyond healthcare, and a significant trend toward non-invasive solutions. North America currently dominates the market, while the Asia-Pacific region is emerging as the most lucrative growth area [33]. Concurrently, research is yielding remarkable technical breakthroughs, such as hybrid deep learning models achieving over 96% accuracy in EEG signal classification and the demonstration of real-time, non-invasive robotic hand control at the individual finger level [5] [34]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of these market dynamics and the underlying experimental protocols powering the next generation of BCI technology.

Global Market Size and Projections

The global BCI market demonstrates robust growth across multiple independent analyses, reflecting strong sector-wide confidence.

Table 1: Global BCI Market Size Projections

| Source/Base Year | Market Size (Base Year) | Projected Market Size | Forecast Period | CAGR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coherent Market Insights [33] | USD 2.40 Bn (2025) | USD 6.16 Bn | 2025-2032 | 14.4% |

| Straits Research [35] | USD 2.09 Bn (2024) | USD 8.73 Bn | 2025-2033 | 15.13% |

| Renub Research [36] | USD 158.33 Bn (2024) | USD 181.52 Bn | 2025-2033 | 1.53% |

Note: The significant variance in the Renub Research data suggests a potential difference in market definition or methodology, but the consistent upward trajectory across all reports confirms positive market growth.

Regional Market Analysis

North America, particularly the United States, holds a dominant position in the global BCI landscape, accounting for over 39% of the global market share [33] [35]. The U.S. market alone is projected to grow from USD 617.60 million in 2025 to approximately USD 2,716.30 million by 2034, at a impressive CAGR of 17.90% [37]. This leadership is attributed to advanced healthcare infrastructure, substantial R&D investments, and the presence of key industry players like Neuralink and Synchron [37] [35]. Meanwhile, the Asia-Pacific region is poised to register the fastest growth rate, driven by growing investments in healthcare, a large patient population, and supportive government policies [33] [35].

Market Segmentation and Key Drivers

Table 2: BCI Market Segmentation and Key Characteristics

| Segment | Dominant Sub-category | Market Share & Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|

| Product Type | Non-Invasive BCI | Held the largest market share (60.7% in 2025) due to lower risk, greater comfort, and user accessibility [33]. |

| Application | Healthcare & Rehabilitation | Rehabilitation and restoration segment holds a prominent share; driven by rising neurological disorders [33] [2]. |

| End User | Hospitals | Likely to remain the leading end user of BCI products [33]. |

| Component | Software & Algorithms | Crucial for processing large amounts of neural data, extracting features, and enabling device integration [37]. |

Primary Market Drivers:

- Rising Neurological Disorders: The increasing incidence of conditions like Alzheimer's, epilepsy, and Parkinson's disease (projected to affect 25.2 million people globally by 2050) is a major growth driver [33] [37].

- Technological Advancements: Progress in neuroscience, AI, and signal processing is enhancing BCI capabilities and commercial viability [33] [36].

- Expanding Non-Medical Applications: Growing adoption in gaming, smart home control, and defense sectors is broadening the market base [33] [35] [36].

Technical Foundations and Experimental Protocols

The remarkable market growth is underpinned by significant advancements in EEG signal processing and classification methodologies. The following sections detail core experimental protocols that are pushing the boundaries of BCI performance.

Protocol: Enhanced EEG Classification Using a Hybrid Deep Learning Model

This experiment aimed to enhance Motor Imagery (MI) classification within BCI systems by leveraging a novel hybrid deep learning model [5].

Methodology

- Dataset: The "PhysioNet EEG Motor Movement/Imagery Dataset" was used, which encompasses EEG data from various motor tasks [5].

- Preprocessing & Feature Extraction: A comprehensive pipeline was employed, including normalization, band-pass filtering, and artifact removal. Advanced feature extraction techniques such as Wavelet Transform and Riemannian Geometry were applied to capture critical time-frequency and geometric features [5].

- Data Augmentation: Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) were introduced to generate synthetic EEG data, helping to balance the dataset and improve model generalization [5].

- Model Architecture: A hybrid CNN-LSTM model was proposed. The Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) component excels at extracting spatial features from EEG data, while the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) component captures temporal dependencies [5].

- Comparison Models: Performance was compared against five traditional machine learning classifiers: K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Support Vector Classifier (SVC), Logistic Regression (LR), Random Forest (RF), and Naive Bayes (NB), as well as standalone CNN and LSTM models [5].

- Training: The training process was optimized, with each epoch limited to 5 seconds, reaching peak accuracy within 30-50 epochs [5].

The hybrid CNN-LSTM model significantly outperformed all other approaches, achieving an exceptional classification accuracy of 96.06% [5]. Among the traditional classifiers, Random Forest achieved the highest accuracy of 91%, while standalone CNN and LSTM models achieved 88.18% and 16.13%, respectively [5]. This demonstrates the potent synergy of spatial and temporal feature learning for complex EEG signal classification.

Diagram 1: Hybrid CNN-LSTM Model Workflow

Protocol: Real-Time Robotic Hand Control via EEG

This study presented a breakthrough in noninvasive BCI by enabling real-time control of a robotic hand at the individual finger level using Motor Execution (ME) and Motor Imagery (MI) [34].

Methodology

- Participants: 21 able-bodied human participants with previous BCI experience [34].

- Experimental Design: Participants underwent one offline session (for model training and task familiarization) and two online sessions for finger ME and MI tasks. The tasks involved movement or imagination of movements of the thumb, index finger, and pinky of the dominant hand [34].

- Signal Acquisition: EEG signals were recorded using standard scalp EEG.

- Decoding Model: EEGNet-8,2, a compact convolutional neural network optimized for EEG-based BCIs, was implemented for real-time decoding of individual finger movements [34].

- Fine-Tuning: To address inter-session variability, a fine-tuning mechanism was used. A base model trained on offline data was further calibrated using data from the first half of each online session, creating a session-specific model for the second half [34].

- Feedback: Participants received two forms of real-time feedback: visual (on-screen color indication of decoding correctness) and physical (corresponding finger movement on a robotic hand) [34].

- Online Smoothing: A smoothing algorithm was applied to the decoder's continuous outputs to stabilize the control commands sent to the robotic hand [34].

The system demonstrated the feasibility of naturalistic, noninvasive robotic finger control. After training and model fine-tuning, the real-time decoding accuracies achieved were 80.56% for two-finger (binary) MI tasks and 60.61% for three-finger (ternary) MI tasks [34]. Performance significantly improved across online sessions, and fine-tuning was shown to enhance BCI performance by adapting to individual session-specific neural patterns [34].

Diagram 2: Real-Time BCI Control Loop

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for BCI Experimentation

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| EEG Acquisition System | Records electrical brain activity from the scalp. | Includes Ag-AgCl electrodes, amplifiers, Analog-to-Digital Converters (ADC). Sampling rates: 250 Hz, 500 Hz, 1000 Hz [3]. |

| Standardized EEG Datasets | Provides benchmark data for training and validating algorithms. | "PhysioNet EEG Motor Movement/Imagery Dataset" for motor tasks [5]. |

| Preprocessing Algorithms | Removes noise and artifacts to enhance signal quality. | Independent Component Analysis (ICA), Wavelet Transform (WT), Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA), Band-pass filtering [2] [3]. |

| Feature Extraction Tools | Transforms raw EEG signals into meaningful features for classification. | Wavelet Transform, Riemannian Geometry, Power Spectral Density (PSD), Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) [5] [2]. |

| Deep Learning Models | Serves as the core classification/decoding engine. | EEGNet (for general EEG decoding) [34], Hybrid CNN-LSTM (for spatio-temporal feature learning) [5]. |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Generates synthetic EEG data to augment training datasets and address overfitting. | Used to balance datasets and improve model generalization [5]. |

| Robotic Actuator/Hand | Provides physical embodiment for BCI output and user feedback. | Used in real-time control experiments to demonstrate dexterous application [34]. |

| N-(4-cyanophenyl)-4-methoxybenzamide | N-(4-Cyanophenyl)-4-methoxybenzamide|CAS 149505-74-8 | N-(4-Cyanophenyl)-4-methoxybenzamide (CAS 149505-74-8), a research chemical for organic synthesis. Product for Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Boc-Lys(Boc)-OSu | Boc-Lys(Boc)-OSu, CAS:30189-36-7, MF:C20H33N3O8, MW:443.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The global BCI technology market is on a trajectory of explosive growth, fueled by clinical needs and technological convergence. The shift toward non-invasive solutions and the expansion into consumer and industrial applications are defining trends. Critically, this market progress is inextricably linked to foundational research advances in EEG signal processing. The development of sophisticated AI models, such as hybrid deep learning architectures and specialized networks like EEGNet, coupled with robust experimental protocols for real-time system control, are overcoming historical challenges of accuracy and dexterity. As these technologies mature and address persistent constraints such as high costs and ethical considerations, BCI is poised to transition from a specialized assistive tool to a mainstream technology with profound implications for human-computer interaction.

AI-Driven Processing and Clinical Translation of EEG Signals

Electroencephalogram (EEG) is a non-invasive, cost-effective method for recording electrical brain activity with high temporal resolution, making it a cornerstone technology for brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), cognitive monitoring, and neurological disorder diagnosis [38] [39]. However, EEG signals are inherently dynamic, non-linear, non-stationary, and exhibit low spatial resolution and amplitude, posing significant challenges for traditional signal processing and machine learning techniques [38] [40] [6]. The advent of deep learning has revolutionized EEG analysis, with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, and Transformer architectures emerging as particularly powerful tools for decoding complex neural patterns [38] [41]. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of these three foundational deep learning architectures within the context of BCI signal processing research, offering researchers and scientists a comprehensive framework for architectural selection, implementation, and optimization.

Core Architectural Foundations and Comparative Analysis

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for EEG Analysis

CNNs excel at identifying spatially local patterns through their hierarchical structure of convolutional layers, making them particularly well-suited for extracting discriminative features from EEG signals represented as topological maps or time-frequency images [40] [41]. Unlike traditional machine learning approaches that require manual feature engineering, CNNs can automatically learn relevant features directly from raw or minimally processed EEG data [40].

Key Architectural Variations:

- Standard CNNs: Apply single or multiple convolutional layers followed by pooling and fully connected layers for end-to-end EEG classification [40].

- Recurrent Convolutional Neural Networks (R-CNNs): Integrate recurrent connections within convolutional layers to better model temporal dependencies [40].

- Decoder Architectures: Utilize encoder-decoder structures for tasks requiring reconstruction or sequence generation [40].

- Cascade Architectures: Employ multiple specialized CNN modules in sequence for complex feature extraction pipelines [40].

CNNs automatically learn and extract complex features from raw input data, overcoming limitations of predefined band-pass filters that can only capture simple frequency patterns [40]. Their ability to model non-linear relationships makes them particularly valuable for EEG analysis where linear models often fail to capture the complex dynamics of brain activity [40].

Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks

LSTMs address the vanishing gradient problem of traditional RNNs through gating mechanisms, enabling them to capture long-range temporal dependencies in sequential data like EEG signals [42] [43]. This architecture is particularly valuable for EEG applications where contextual information across extended time periods is crucial for accurate classification.

Core Mechanism: The LSTM unit incorporates three gates (input, forget, output) and a cell state that regulates information flow over time [43]. The input gate controls new information entry into the cell state, the forget gate determines what information to discard, and the output gate regulates the information passed to the next time step [43]. This gated structure enables the network to maintain relevant information over long sequences while discarding irrelevant data.

Bidirectional LSTM (BLSTM) variants process sequences in both forward and backward directions, capturing both past and future context for each time point [43]. Studies have demonstrated BLSTM's effectiveness in cognitive age prediction from EEG, achieving 86% accuracy when distinguishing between young children and adolescents [43].

Transformer Architectures

Transformers utilize self-attention mechanisms to model global dependencies in sequential data without the recurrence constraints of RNNs [38] [44]. The core innovation lies in their ability to compute pairwise relationships between all elements in a sequence simultaneously, enabling parallel processing and capturing long-range contextual information more effectively than recurrent architectures [38].

Key Components:

- Self-Attention Mechanism: Computes attention weights for each token in the sequence based on queries, keys, and values, allowing the model to focus on relevant elements [38].

- Multi-Head Attention: Applies multiple attention mechanisms in parallel to capture different contextual relationships [38].

- Positional Encoding: Injects information about token order using sine and cosine functions since transformers lack inherent recurrence [38].

Vision Transformer (ViT) adaptations have been successfully applied to EEG analysis by treating signal segments as patches, while specialized variants like the Lightweight Convolutional Transformer Neural Network (LCTNN) integrate convolutional layers for local feature extraction alongside attention mechanisms for global dependency modeling [38] [44].

Performance Comparison Across Architectures

Table 1: Comparative performance of deep learning architectures on representative EEG tasks

| Architecture | Application | Dataset | Key Performance Metric | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid CNN-LSTM | Motor Imagery Classification | PhysioNet EEG Motor Movement/Imagery Dataset | 96.06% Accuracy | [5] |

| Random Forest (Traditional ML) | Motor Imagery Classification | PhysioNet EEG Motor Movement/Imagery Dataset | 91.00% Accuracy | [5] |

| CNN Only | Motor Imagery Classification | PhysioNet EEG Motor Movement/Imagery Dataset | 88.18% Accuracy | [5] |

| LSTM Only | Motor Imagery Classification | PhysioNet EEG Motor Movement/Imagery Dataset | 16.13% Accuracy | [5] |

| LSTM | Seizure Prediction | NeuroVista intracranial EEG | Significant improvement over random prediction | [42] |

| BLSTM | Cognitive Age Prediction | Hospital EEG Dataset | 86.0% Accuracy (2-class) | [43] |

| BLSTM | Cognitive Age Prediction | Hospital EEG Dataset | 69.3% Accuracy (3-class) | [43] |

| LCTNN (CNN-Transformer) | Depression Recognition | EEG Depression Datasets | State-of-the-art on most metrics | [44] |

Table 2: Strengths and limitations of each architecture for EEG processing

| Architecture | Strengths | Limitations | Ideal EEG Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | Automatic spatial feature extraction, translation invariance, parameter efficiency | Limited temporal context capture, fixed receptive field | Topographic map classification, spatial pattern recognition, spectral analysis |

| LSTM | Long-term temporal dependency modeling, sequential processing, handles variable-length inputs | Sequential processing limits parallelism, vanishing gradients in very long sequences, computationally intensive | Seizure prediction, cognitive state monitoring, sleep stage scoring |

| Transformer | Global context modeling, parallel processing, superior long-range dependency capture | High computational complexity O(L²), requires large datasets, lacks inherent positional awareness | Multichannel EEG analysis, complex pattern recognition across time and space |

Architectural Implementation and Experimental Protocols

EEG-Specific Data Preparation Pipeline

Effective implementation of deep learning architectures for EEG requires specialized data preparation. The following protocol outlines critical steps for ensuring model performance and generalizability:

Signal Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Data Acquisition: Collect EEG signals according to international 10-20 system placement with appropriate sampling rates (typically 200-1000 Hz) [43].

- Filtering: Apply band-pass filters (e.g., 0.5-40 Hz) to remove high-frequency noise and slow drifts while preserving neural signals of interest [5] [42].

- Artifact Removal: Implement techniques like Independent Component Analysis (ICA) to remove ocular, cardiac, and muscle artifacts [5] [39].

- Normalization: Apply amplitude normalization using z-score or min-max scaling to ensure stable training [42].