From Neural Circuits to Algorithms: How the Population Doctrine is Revolutionizing Optimization

This article explores the transformative intersection of theoretical neuroscience and optimization, focusing on the emerging 'population doctrine.' This paradigm shift identifies neural populations, not single neurons, as the brain's fundamental...

From Neural Circuits to Algorithms: How the Population Doctrine is Revolutionizing Optimization

Abstract

This article explores the transformative intersection of theoretical neuroscience and optimization, focusing on the emerging 'population doctrine.' This paradigm shift identifies neural populations, not single neurons, as the brain's fundamental computational units. We examine the core principles of this doctrine—state spaces, manifolds, and dynamics—and detail how they inspire novel, brain-inspired meta-heuristic algorithms. The discussion extends to practical applications, including adaptive experimental design and clinical neuromodulation, while addressing implementation challenges and validation strategies. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this synthesis highlights how understanding collective neural computation can lead to more robust, efficient, and adaptive optimization techniques for complex scientific and biomedical problems.

The Paradigm Shift: Understanding the Neural Population Doctrine

The field of neuroscience is undergoing a profound conceptual transformation, moving from a focus on individual neurons to understanding how populations of neurons collectively generate brain function. This shift represents a historic transition from the long-dominant Neuron Doctrine to an emerging Population Doctrine. The Neuron Doctrine, firmly established by the seminal work of Santiago Ramón y Cajal and formally articulated by von Waldeyer-Hartz in 1891, posits that the nervous system is composed of discrete individual cells (neurons) that serve as the fundamental structural and functional units of the nervous system [1] [2]. This doctrine provided a powerful analytical framework for over a century, enabling neuroscientists to deconstruct neural circuits into their basic components. However, technological advances in large-scale neural recording and computational modeling have revealed that complex cognitive functions emerge not from individual neurons but from collective activity patterns across neural populations [3]. This population doctrine is now drawing level with single-neuron approaches, particularly in motor neuroscience, and holds great promise for resolving open questions in cognition, including attention, working memory, decision-making, and executive function [3].

This shift carries particular significance for optimization research, where neural population dynamics offer novel inspiration for algorithm development. The brain's remarkable ability to process diverse information types and efficiently reach optimal decisions provides a powerful model for creating more effective computational methods [4]. Understanding population-level coding principles may enable researchers to develop brain-inspired optimization algorithms that better balance exploration and exploitation—a fundamental challenge in computational intelligence.

Historical Foundation: The Neuron Doctrine

Core Principles and Historical Context

The Neuron Doctrine emerged in the late 19th century from crucial anatomical work, most notably by Santiago Ramón y Cajal, whose meticulous observations using Camillo Golgi's silver staining technique provided compelling evidence that nervous systems are composed of discrete cellular units [1]. Before this doctrine gained acceptance, the prevailing reticular theory proposed that nervous systems constituted a continuous network rather than separate cells [2]. The controversy between these views persisted for decades, with Golgi himself maintaining his reticular perspective even when accepting the Nobel Prize alongside Cajal in 1906 [1].

The table below summarizes the core elements of the established Neuron Doctrine:

Table 1: Core Elements of the Neuron Doctrine

| Element | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Neural Units | The brain comprises individual units with specialized features (dendrites, cell body, axon) | Provided basic structural framework for neural anatomy |

| Neurons as Cells | These individual units are cells consistent with those in other tissues | Integrated neuroscience with general cell theory |

| Specialization | Units differ in size, shape, and structure based on location/function | Explained functional diversity within nervous systems |

| Nucleus as Key | The nucleus serves as the trophic center for the cell | Established fundamental cellular maintenance principles |

| Nerve Fibers as Processes | Nerve fibers are outgrowths of nerve cells | Clarified anatomical relationships within neural circuits |

| Cell Division | Nerve cells generate through cell division | Established developmental principles |

| Contact | Nerve cells connect via sites of contact (not cytoplasmic continuity) | Provided basis for synaptic communication theory |

| Law of Dynamic Polarization | Preferred direction for transmission (dendrites/cell body → axon) | Established information flow principles within circuits |

| Synapse | Barrier to transmission exists at contact sites between neurons | Explained directional communication and modulation |

| Unity of Transmission | Contacts between specific neurons are consistently excitatory or inhibitory | Simplified functional classification of connections |

The Neuron Doctrine served as an exceptionally powerful analytical tool, enabling neuroscientists to parse the complexity of nervous systems into manageable units [2]. For decades, it guided research into neural pathways, synaptic transmission, and functional localization. However, this reductionist approach inevitably faced limitations in explaining system-level behaviors and population dynamics.

Limitations and the Need for a New Framework

While the Neuron Doctrine successfully explained many aspects of neural organization, contemporary research has revealed notable exceptions and limitations. Electrical synapses are more common in the central nervous system than previously recognized, creating direct cytoplasm-to-cytoplasm connections through gap junctions that form syncytia [1]. The phenomenon of cotransmission, where multiple neurotransmitters are released from a single presynaptic terminal, contradicts the strict interpretation of Dale's Law [1]. Additionally, in what is now considered a "post-neuronist era," we recognize that nerve cells can form cell-to-cell fusions and do not always function as strictly independent units [2].

Most significantly, the Neuron Doctrine has proven inadequate for explaining how cognitive functions and behaviors emerge from neural activity. Individual neurons typically exhibit complex, mixed selectivity to task variables rather than encoding single parameters, making it difficult to read out information from single cells [3]. This fundamental limitation has driven the field toward population-level approaches that can capture emergent computational properties.

The Emerging Population Doctrine: Core Concepts and Framework

Theoretical Foundation

The Population Doctrine represents a paradigm shift that complements rather than completely replaces the Neuron Doctrine. While still recognizing neurons as fundamental cellular units, this new framework emphasizes that information processing and neural computation primarily occur through collective interactions in neural populations [3]. This perspective has gained momentum with the development of technologies enabling simultaneous recording from hundreds to thousands of neurons, revealing population-level dynamics that are invisible when monitoring single units.

The Population Doctrine is particularly valuable for cognitive neuroscience, where it offers new approaches to investigating attention, working memory, decision-making, executive function, learning, and reward processing [3]. In these domains, population-level analyses have provided insights that single-unit approaches failed to deliver, explaining how neural circuits perform complex computations through distributed representations.

Five Core Concepts of Population-Level Thinking

The Population Doctrine can be organized around five fundamental concepts that provide a foundation for population-level analysis [3]:

Table 2: Five Core Concepts of the Population Doctrine

| Concept | Description | Research Utility |

|---|---|---|

| State Spaces | A multidimensional space where each axis represents a neuron's firing rate and each point represents the population's activity pattern | Provides complete representation of population activity states |

| Manifolds | Lower-dimensional surfaces within the state space where neural activity is constrained, often reflecting task variables | Reveals underlying structure in population activity and computational constraints |

| Coding Dimensions | Specific directions in the state space that correspond to behaviorally relevant variables or computational processes | Identifies how information is represented within population activity |

| Subspaces | Independent neural dimensions that can be selectively manipulated without affecting other encoded variables | Enables dissection of parallel processing in neural populations |

| Dynamics | How population activity evolves over time according to rules that can be linear or nonlinear | Characterizes computational processes implemented by neural circuits |

These concepts provide researchers with a conceptual toolkit for analyzing high-dimensional neural data and understanding how neural populations implement computations. Rather than examining neurons in isolation, this framework focuses on the collective properties and emergent dynamics of neural ensembles.

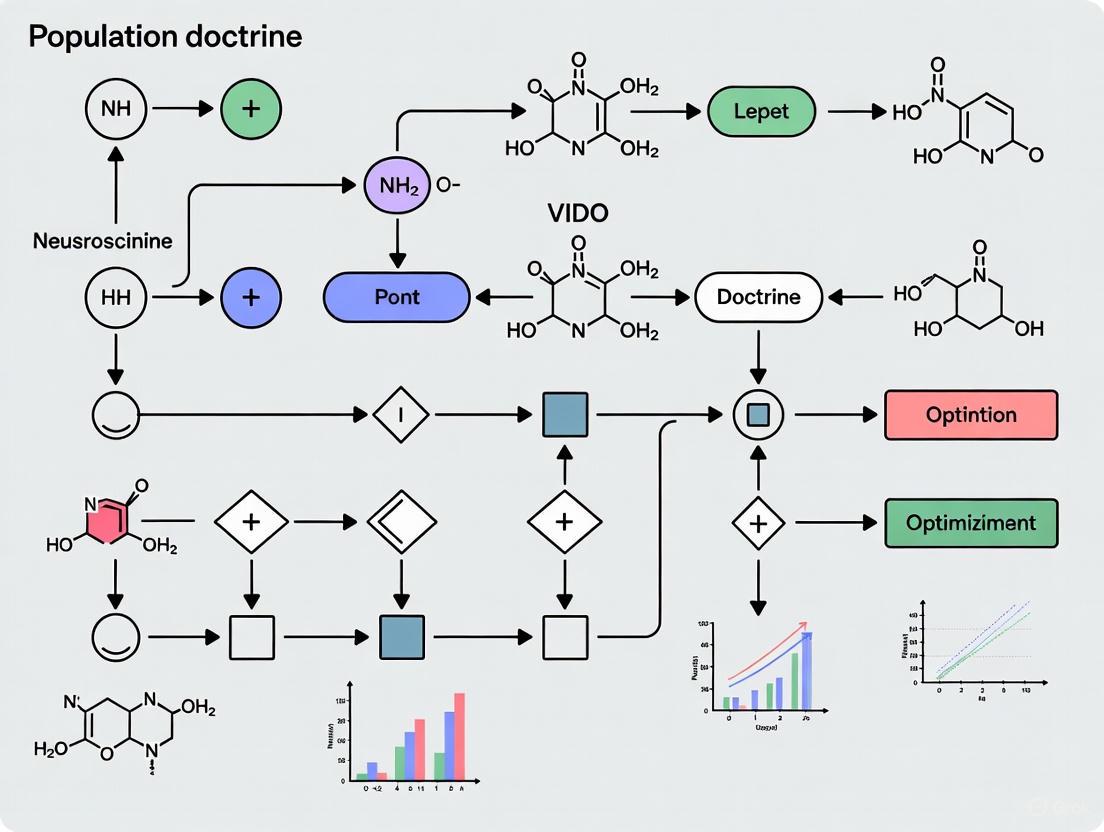

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationships and analytical workflow within the Population Doctrine framework:

Experimental Methodologies for Population-Level Neuroscience

Data Collection Technologies

Advances in neural recording technologies have been the primary enabler of population-level neuroscience. The following experimental approaches are essential for capturing population activity:

Table 3: Key Methodologies for Neural Population Research

| Methodology | Description | Key Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large-scale electrophysiology | Simultaneous recording from hundreds of neurons using multi-electrode arrays | Characterizing population dynamics across brain regions | High temporal resolution but limited spatial coverage |

| Two-photon calcium imaging | Optical recording of neural activity using fluorescent calcium indicators | Monitoring population activity in superficial brain structures | Excellent spatial resolution with good temporal resolution |

| Neuropixels probes | High-density silicon probes enabling thousands of simultaneous recording sites | Large-scale monitoring of neural populations across depths | Revolutionary density but requiring specialized infrastructure |

| Wide-field calcium imaging | Large-scale optical recording of cortical activity patterns | Mesoscale population dynamics across cortical areas | Broad coverage with limited cellular resolution |

| fMRI multivariate pattern analysis | Decoding information from distributed patterns of BOLD activity | Human population coding noninvasively | Indirect measure of neural activity with poor temporal resolution |

Quantitative Analysis Framework

Analyzing population-level neural data requires specialized quantitative approaches that differ significantly from single-unit analysis methods. The workflow typically involves:

Data Preprocessing and Dimensionality Reduction: Raw neural data (spike times, calcium fluorescence) is converted into a population activity matrix (neurons × time). Dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or factor analysis are then applied to identify dominant patterns of co-variation across the neural population [3]. This step is crucial for visualizing and interpreting high-dimensional data.

State Space Analysis: The reduced-dimensional representation creates a neural state space where each point represents the instantaneous population activity. Trajectories in this space reveal how neural populations evolve during behavior, with different cognitive states occupying distinct regions [3]. This approach has been particularly fruitful for studying sequential dynamics in working memory and decision-making tasks.

Demixed Principal Component Analysis (dPCA): This specialized technique identifies neural dimensions that specifically encode task variables (e.g., stimulus identity, decision, motor output) by demixing their contributions to population variance [3]. Unlike standard PCA, which finds dimensions of maximum variance regardless of task relevance, dPCA explicitly separates task-relevant signals.

Population Dynamics Modeling: Neural population dynamics are typically modeled using linear dynamical systems, where activity evolves according to:

where x(t) is the neural state vector, A defines the dynamics, B maps inputs u(t) to the state, and ε represents noise. Recent work has extended this to nonlinear dynamics to capture more complex computational operations.

The following diagram illustrates the typical experimental workflow in population-level neuroscience:

Visualization Approaches for High-Dimensional Neural Data

Effective visualization is particularly challenging for high-dimensional neural population data. Traditional approaches like connectograms and connectivity matrices provide limited anatomical context, while 3D brain renderings suffer from occlusion issues with complex datasets [5]. Recent advances include:

Spatial-Data-Driven Layouts: These novel approaches arrange 2D node-link diagrams of brain networks while preserving their spatial organization, providing anatomical context without manual node positioning [5]. These methods generate consistent, perspective-dependent arrangements applicable across species (mouse, human, Drosophila), enabling clearer visualization of network relationships.

Population Activity Visualizations: Techniques such as tiled activity maps, trajectory plots, and dimensionality-reduced views help researchers identify patterns in population recordings. These visualizations must balance completeness with interpretability, often requiring careful design choices to avoid misleading representations [6].

Applications in Optimization Research: The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm

Brain-Inspired Meta-Heuristic Algorithm

The principles of neural population dynamics have recently inspired a novel meta-heuristic optimization approach called the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) [4]. This algorithm translates neuroscientific principles of population coding into an effective optimization method, demonstrating the practical utility of the Population Doctrine for computational intelligence.

NPDOA simulates the activities of interconnected neural populations during cognitive processing and decision-making. In this framework, each potential solution is treated as a "neural state" of a population, with decision variables representing neurons and their values corresponding to firing rates [4]. The algorithm implements three core strategies derived from neural population principles:

Table 4: Core Strategies in NPDOA

| Strategy | Neural Inspiration | Computational Function | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attractor Trending | Neural populations converging toward stable states representing decisions | Drives exploitation by moving solutions toward local optima | Guides population toward best-known solutions |

| Coupling Disturbance | Interference between neural populations disrupting attractor states | Enhances exploration by pushing solutions from local optima | Introduces perturbations through population coupling |

| Information Projection | Regulated communication between neural populations | Balances exploration-exploitation tradeoff | Controls influence of other strategies on solution updates |

Performance and Advantages

NPDOA has demonstrated superior performance on benchmark problems and practical engineering applications compared to established meta-heuristic algorithms, including Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Genetic Algorithms (GA), and Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) [4]. The algorithm's brain-inspired architecture provides several advantages:

- Improved Balance: Better equilibrium between exploration and exploitation phases

- Reduced Premature Convergence: Enhanced ability to escape local optima

- Computational Efficiency: Effective performance on high-dimensional problems

This successful translation of neural population principles to optimization algorithms validates the practical utility of the Population Doctrine and suggests fertile ground for further cross-disciplinary innovation.

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Population Neuroscience

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Large-Scale Recording Systems | Neuropixels probes, two-photon microscopes, multi-electrode arrays | Simultaneous monitoring of hundreds to thousands of neurons |

| Genetic Tools | Calcium indicators (GCaMP), optogenetic actuators (Channelrhodopsin), viral tracers | Monitoring and manipulating specific neural populations |

| Data Analysis Platforms | Python (NumPy, SciPy, scikit-learn), MATLAB, Julia | Processing high-dimensional neural data and implementing dimensionality reduction |

| Visualization Tools | Spatial-data-driven layout algorithms, connectome visualization software | Representing complex population data in interpretable formats |

| Computational Modeling Frameworks | Neural network simulators (NEURON, NEST), dynamical systems modeling | Testing hypotheses about population coding principles |

The transition from Neuron Doctrine to Population Doctrine represents a fundamental evolution in how neuroscientists conceptualize and investigate neural computation. This shift recognizes that while neurons are the structural units of nervous systems, neural populations serve as the functional computational units underlying cognition and behavior. The Population Doctrine provides a powerful conceptual framework organized around state spaces, manifolds, coding dimensions, subspaces, and dynamics [3].

This paradigm shift extends beyond basic neuroscience to inspire innovation in computational fields, particularly optimization research, where brain-inspired algorithms like NPDOA demonstrate the practical utility of population-level principles [4]. As recording technologies continue to advance, enabling even larger-scale monitoring of neural activity, and analytical methods become increasingly sophisticated, the Population Doctrine promises to deliver deeper insights into the organizational principles of neural computation.

The ongoing integration of population-level approaches with molecular, genetic, and clinical neuroscience heralds a more comprehensive understanding of brain function in health and disease. This historic shift from single neurons to neural populations represents not an abandonment of cellular neuroscience but rather its natural evolution toward a more complete, systems-level understanding of how brains work.

For decades, the single-neuron doctrine has dominated neuroscience, operating on the assumption that the neuron serves as the fundamental computational unit of the brain. However, a major shift is now underway within neurophysiology: a population doctrine is drawing level with this traditional view [3] [7]. This emerging paradigm posits that the fundamental computational unit of the brain is not the individual neuron, but the population [7]. The core of this doctrine rests on the understanding that behavior relies on the distributed and coordinated activity of neural populations, and that information about behaviorally important variables is carried by population activity patterns rather than by single cells in isolation [8] [9].

This shift has been catalyzed by both technological and conceptual advances. The development and spread of new technologies for recording from large groups of neurons simultaneously has enabled researchers to move beyond studying neurons in isolation [8] [7]. Alongside new hardware, an explosion of new concepts and analyses have come to define the modern, population-level approach to neurophysiology [7]. What truly defines this field is its object of study: the neural population itself. To a population neurophysiologist, neural recordings are not random samples of isolated units, but instead low-dimensional projections of the entire manifold of neural activity [7].

Theoretical Foundations of Population Coding

Core Concepts of Population-Level Analysis

The population doctrine framework is organized around several foundational concepts that provide a foundation for population-level thinking [3] [7]:

State Spaces: The canonical analysis for population neurophysiology is the neural population's state space diagram. Instead of plotting the firing rate of one neuron against time, the state space represents the activity of each neuron as a dimension in a high-dimensional space. At every moment, the population occupies a specific neural state—a point in this neuron-dimensional space, equivalently described as a vector of firing rates across all recorded neurons [7].

Manifolds: Neural population activity often occupies a low-dimensional manifold embedded within the high-dimensional state space. This manifold represents the structured patterns of coordinated neural activity that underlie computation and behavior [3].

Coding Dimensions: Populations encode information along specific dimensions in the state space. These dimensions may correspond to relevant task variables (e.g., sensory features, decision variables, motor outputs) or to more abstract computational quantities [3].

Subspaces: Neural populations can implement multiple computations in parallel by organizing activity into independent subspaces within the overall state space. This allows the same population to participate in multiple functions without interference [3].

Dynamics: Time links sequences of neural states together, creating trajectories through the state space. The dynamics of these trajectories—how the population state evolves over time—reveals the computational processes being implemented [3] [7].

Key Advantages of Population Coding

Information Capacity and Robustness

Population coding provides significant advantages over single-neuron coding in terms of information capacity and robustness. The ability of a heterogeneous population to discriminate among stimuli generally increases with population size, as neurons with diverse stimulus preferences carry complementary information [8]. This diversity means that individual neurons may add unique information due to differences in stimulus preference, tuning width, or response timing [8].

Table 1: Advantages of Population Coding over Single-Neuron Coding

| Aspect | Single-Neuron Coding | Population Coding |

|---|---|---|

| Information Capacity | Limited by individual neuron's firing rate and dynamic range | Increases with population size through complementary information [8] |

| Robustness to Noise | Vulnerable to variability in individual neurons | Redundant coding and averaging across neurons enhances reliability [9] |

| Dimensionality | Limited to encoding one or few variables | High-dimensional representations through mixed selectivity [8] |

| Fault Tolerance | Failure of single neuron disrupts coding | Distributed representations tolerate loss of individual units [8] |

| Computational Power | Limited nonlinear operations | Rich computational capabilities through population dynamics [3] [7] |

Temporal and Mixed Selectivity

Population coding leverages both temporal patterns and mixed selectivity to enhance computational power:

Temporal Coding: In a population, informative response patterns can include the relative timing between neurons. Precise spike timing carries information that is complementary to that contained in firing rates and cannot be replaced by coarse-scale firing rates of other neurons in the population [8]. This temporal dimension remains crucial even at the population level [8] [10].

Mixed Selectivity: In higher association regions, neurons often exhibit nonlinear mixed selectivity—complex patterns of selectivity to multiple sensory and task-related variables combined in nonlinear ways [8]. This mixed selectivity creates a high-dimensional population representation that has higher dimensionality than its linear counterpart and can be more easily decoded by downstream areas using simple linear operations [8]. This combination of sparseness and high-dimensional mixed selectivity achieves an optimal trade-off for efficient computation [8].

Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Quantitative Evidence for Population Coding

Multiple lines of experimental evidence support the population doctrine across different brain regions and functions:

Table 2: Key Experimental Evidence Supporting Population Coding

| Brain Region/Function | Experimental Finding | Implication for Population Coding |

|---|---|---|

| Inferotemporal Cortex | State vector direction encodes object identity; magnitude predicts memory retention [7] | Population pattern, not individual neurons, carries behaviorally relevant information |

| Prefrontal Cortex | Heterogeneous nonlinear mixed selectivity for task variables [8] | Enables high-dimensional representations that facilitate linear decoding |

| Auditory System | Precise spike patterns carry information complementary to firing rates [8] | Temporal coordination across population adds information capacity |

| Motor Cortex | Population vectors accurately predict movement direction [9] | Motor parameters are encoded distributedly across populations |

| Working Memory | Memory items represented as trajectories in state space [3] [7] | Population dynamics implement memory maintenance and manipulation |

Measuring Population Codes: Experimental Protocols

State Space Analysis Protocol

Objective: To characterize population activity patterns and their relationship to behavior.

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Simultaneously record activity from dozens to hundreds of neurons using multi-electrode arrays, two-photon calcium imaging, or neuropixels probes [8] [7].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply dimensionality reduction techniques (PCA, t-SNE, UMAP) to project high-dimensional neural data into lower-dimensional state spaces for visualization and analysis [3] [7].

- Trajectory Analysis: Track the evolution of population activity over time as trajectories through the state space, identifying attractors, cycles, and other dynamic features [3] [7].

- Distance Metrics: Quantify distances between neural states using Euclidean distance, angular separation, or Mahalanobis distance (which accounts for the covariance structure between neurons) [7].

Interpretation: Neural state distances can reveal cognitive or behavioral discontinuities—sudden changes in beliefs or policies—that may reflect hierarchical inference processes [7].

Information Decoding Protocol

Objective: To quantify how much information neural populations carry about specific stimuli or behaviors.

Methodology:

- Response Characterization: Measure neural responses to repeated presentations of stimuli or performance of behaviors to characterize tuning properties and variability [8] [9].

- Decoder Construction: Train linear (linear discriminant analysis, support vector machines) or nonlinear (neural networks) decoders to extract stimulus or behavior information from population activity patterns [8] [9].

- Information Quantification: Use Shannon or Fisher information measures to quantify how much information populations carry about relevant variables, comparing to the information available from single neurons [8] [9].

- Correlation Analysis: Measure noise correlations between neurons and assess their impact on information encoding and decoding [9].

Interpretation: Even small correlations between neurons can have large effects on population coding capacity, and these effects cannot be extrapolated from pair-wise measurements alone [9].

Table 3: Essential Tools and Methods for Population Neuroscience Research

| Tool/Method | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-electrode Arrays | Simultaneously record dozens to hundreds of neurons | Measuring coordinated activity patterns across neural populations [8] [7] |

| Two-Photon Calcium Imaging | Optical recording of neural populations with single-cell resolution | Tracking population dynamics in specific cell types during behavior [8] |

| Dimensionality Reduction Algorithms | Project high-dimensional neural data to low-dimensional manifolds | Identifying state spaces and neural trajectories [3] [7] |

| Population Decoding Models | Extract information from population activity patterns | Quantifying information about stimuli, decisions, or actions [8] [9] |

| Dynamic Network Models | Model population activity as evolving dynamical systems | Understanding how neural dynamics implement computations [3] [7] |

Visualization of Population Coding Concepts

State Space and Neural Trajectories Diagram

This diagram illustrates the core concept of neural state spaces. Each point represents a population state defined by the firing rates of all recorded neurons at a given time. The trajectories show how these states evolve during different cognitive processes or behaviors. The direction of the state vector reflects the specific pattern of activity across neurons, while the magnitude represents the overall activity level. Distances between states may correspond to cognitive discontinuities or changes in behavioral policy [7].

Population Coding Advantages Diagram

This diagram contrasts single neuron coding with population coding, highlighting key advantages of the population approach. Population coding leverages heterogeneous response properties across neurons—including differences in tuning width, mixed selectivity, and temporal response properties—to create high-dimensional representations that enable better stimulus discrimination and more flexible computations [8]. The diversity of neural response properties allows the population to encode more information than any single neuron could alone.

Implications for Research and Therapeutics

Methodological Implications for Neuroscience Research

The population doctrine necessitates significant shifts in experimental design and data analysis:

Beyond Single-Unit Focus: Studies focusing on single neurons in isolation may miss fundamental aspects of neural computation, as the information present in neural responses cannot be fully estimated by single neuron recordings [9].

Correlation Structure Matters: The correlation structure between neurons significantly impacts population coding, and these effects can be large at the population level even when small at the level of pairs [9]. Understanding neural computation therefore requires measuring and modeling these correlations.

Dynamics Over Static Responses: The temporal evolution of population activity—neural trajectories through state space—provides insights into neural computation that static response profiles cannot reveal [3] [7].

Implications for Neurological and Psychiatric Therapeutics

Understanding population coding has significant implications for developing treatments for brain disorders:

Network-Level Dysfunction: Neurological and psychiatric disorders may arise from disruptions in population-level dynamics rather than from dysfunction of specific neuron types. Therapeutic approaches may need to target the restoration of normal population dynamics.

Brain-Computer Interfaces: BCIs that decode population activity patterns typically outperform those based on single units. Understanding population coding principles can significantly improve BCI performance and robustness [9].

Computational Psychiatry: The population framework provides a bridge between neural circuit dysfunction and computational models of cognitive processes, offering new approaches for classifying and treating mental disorders [11].

The evidence from multiple brain regions and experimental approaches consistently supports the population doctrine—the view that neural populations, not individual neurons, serve as the fundamental computational units of the brain. This perspective represents more than just a methodological shift; it constitutes a conceptual revolution in how we understand neural computation. The population approach reveals how collective dynamics, structured variability, and coordinated activity patterns enable the rich computational capabilities of neural circuits.

Moving forward, advancing our understanding of brain function and dysfunction will require embracing population-level approaches. This means developing new experimental techniques for large-scale neural recording, creating analytical tools for characterizing population dynamics, and building theoretical frameworks that explain how population codes implement specific computations. For optimization research in particular, understanding the principles of population coding may inspire new algorithms for distributed information processing and collective computation. The population doctrine thus offers not just a more accurate model of neural computation, but a fertile source of insights for advancing both neuroscience and computational intelligence.

A major shift is underway in neurophysiology: the population doctrine is drawing level with the single-neuron doctrine that has long dominated the field [7]. This paradigm posits that the fundamental computational unit of the brain is the population of neurons, not the individual neuron [7] [4]. While population-level ideas have had significant impact in motor neuroscience, they hold immense promise for resolving open questions in cognition and offer a powerful framework for inspiring novel optimization algorithms in other fields, including computational intelligence [7] [4]. This whitepaper codifies the population doctrine by exploring its five core conceptual pillars, which provide a foundation for population-level thinking and analysis.

The Conceptual Pillars of Population Analysis

State Spaces

For a single-unit neurophysiologist, the canonical analysis is the peristimulus time histogram (PSTH). For a population neurophysiologist, it is the neural population's state space diagram [7]. The state space is a fundamental construct where each axis represents the firing rate of one recorded neuron. At any moment, the population's activity is represented as a single point—a neural state—in this high-dimensional space [7]. Time connects these states into trajectories through the state space, providing a spatial view of neural activity evolution [7].

Key Insights and Applications:

- State Vector Properties: Neural state vectors possess both direction and magnitude. The direction relates to the activity pattern across neurons (e.g., encoding object identity in inferotemporal cortex), while the magnitude (the sum of activity across all neurons) predicts behavioral outcomes like memory fidelity [7].

- Distance Metrics: The state space framework enables measuring distances between neural states using Euclidean distance, the angle between vectors, or Mahalanobis distance (which accounts for neuronal covariance) [7]. Sudden jumps in neural state distances may reflect cognitive discontinuities, such as abrupt changes in beliefs or policies, challenging models of purely gradual decision-making [7].

Table 1: Key Distance Metrics in Neural State Space Analysis

| Metric | Calculation | Key Property | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Euclidean Distance | Straight-line distance between two state vectors | Sensitive to both pattern and overall activity level | General proximity assessment |

| Angular Distance | Cosine of the angle between two state vectors | Pure measure of pattern similarity, insensitive to magnitude | Identifying similar activation patterns despite different firing rates |

| Mahalanobis Distance | Distance accounting for covariance structure between neurons | Measures distance in terms of population's inherent variability | Statistical assessment of whether two states are significantly different |

Manifolds

Neural population activity is typically not scattered randomly throughout the state space but is constrained to a lower-dimensional structure known as a manifold [7]. A manifold can be envisioned as a curved sheet embedded within the high-dimensional state space, capturing the essential degrees of freedom that govern population activity [12]. Recent studies demonstrate that these manifold structures can be remarkably consistent across different individuals and motivational states, suggesting a core computational architecture [12].

Key Insights and Applications:

- Dimensionality Reduction: Manifolds explain how complex computations can arise from relatively simple low-dimensional dynamics, making them vital for understanding brain function and for designing efficient algorithms [12].

- Stereotyped Dynamics: In the insular cortex, for example, activity dynamics within the neuronal manifold are highly stereotyped during rewarded trials, enabling robust prediction of single-trial outcomes across different mice and motivational states [12]. This stereotypy reflects task-dependent, goal-directed anticipation rather than mere motor output or sensory experience [12].

Coding Dimensions

Coding dimensions are the specific directions within the state space or manifold that are relevant for encoding particular task parameters or variables [13]. The brain does not use all possible dimensions of the population activity equally; instead, it selectively utilizes specific subspaces for specific functions [7] [13].

Key Insights and Applications:

- Regression Subspace Analysis: A variant of state-space analysis identifies temporal structures of neural modulations related to continuous (e.g., stimulus value) or categorical (e.g., stimulus identity) task parameters [13]. This approach bridges conventional rate-coding models (which analyze firing rate modulations) and dynamic systems models [13].

- Straight Geometries: For both continuous and categorical parameters, the extracted geometries in the low-dimensional neural modulation space often form straight lines. This suggests their functional relevance is characterized as a unidimensional feature in neural modulation dynamics, simplifying their interpretation and potential application in engineered systems [13].

Table 2: Comparison of Task Parameter Encoding in Neural Populations

| Parameter Type | Definition | Example | Typical Neural Geometry | Analysis Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous | Parameter with a continuous range of values | Stimulus value, movement direction | Straight-line trajectory | Linear regression, Targeted Dimensionality Reduction (TDR) |

| Categorical | Parameter with discrete, distinct values | Stimulus identity, binary choice | Straight-line geometry | demixed Principal Component Analysis (dPCA), ANOVA-based methods |

Subspaces

The concept of subspaces extends the idea of coding dimensions. It refers to the organized partitioning of the full neural activity space into separate, often orthogonal, subspaces that can support independent computations or representations [7]. This allows the same population of neurons to participate in multiple functions without interference.

Key Insights and Applications:

- Computation and Communication: Subspaces can be dedicated to specific functions, such as one subspace for executing a computation (e.g., decision-making) and another for communicating its result to other brain areas [7].

- Dynamic Gating: The ability to create and maintain independent subspaces enables the brain to flexibly gate information flow, allowing for complex, parallel processing within a single network [7].

Dynamics

Dynamics refer to the rules that govern how the neural state evolves over time, forming trajectories through the state space or manifold [7] [13]. These dynamics are the physical implementation of the brain's computations, transforming input representations into output commands [7].

Key Insights and Applications:

- Trajectories as Computation: The path of the neural state trajectory—its geometry and speed—encodes the transformation from sensory evidence to motor commands or cognitive states. Different stimuli or decisions can lead to distinct, reproducible trajectories [13].

- Stable Dynamics Across Conditions: Studies show that neural population dynamics related to specific task parameters can be stable and stereotyped, even across different subjects and motivational states. This stability enables reliable decoding of cognitive processes like reward anticipation [12].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

State-Space Analysis in the Regression Subspace

This protocol bridges conventional rate-coding models and dynamic systems approaches [13].

Procedure:

- Neural Data Collection: Record simultaneous activity from a population of neurons (e.g., via neuropixels or tetrodes) while a subject performs a task involving continuous or categorical parameters.

- Regression Coefficient Estimation: For each neuron and each time point relative to a task event (e.g., stimulus onset), compute the regression coefficients that describe how the firing rate is modulated by the task parameters. This creates a regression matrix,

B(time, neuron). - Dimensionality Reduction: Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to the regression matrix

Bto identify the dominant patterns of neural modulation shared across the population. This reveals the low-dimensional regression subspace. - Trajectory Visualization: Project the population activity onto the principal components of the regression subspace to visualize the temporal evolution of neural states—the neural dynamics—as trajectories. These trajectories describe how task-relevant information is processed over time [13].

Identifying Stereotyped Manifold Dynamics

This protocol uses unsupervised machine learning to identify consistent population-level dynamics [12].

Procedure:

- Population Recording: Use in vivo calcium imaging or high-density electrophysiology to record from hundreds of neurons in a defined brain region (e.g., insular cortex) during goal-directed behavior.

- Manifold Discovery: Apply non-linear dimensionality reduction techniques (e.g., UMAP, t-SNE, or LFADS) to the neural population activity to identify the underlying low-dimensional manifold.

- Cross-Condition Alignment: Assess whether the discovered manifold structure is consistent across different animals and under different experimental conditions (e.g., hunger vs. thirst).

- Dynamics Analysis: Analyze the activity dynamics within the manifold. Look for stereotyped sequences of neural states that are reliably reproduced on single trials and are predictive of behavioral outcomes (e.g., reward consumption).

- Control Analyses: Verify that the observed dynamics are specific to the cognitive process of interest (e.g., goal-directed anticipation) and not confounded by motor outputs (e.g., licking) or simple sensory variables (e.g., taste) [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Population-Level Neuroscience Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density Neural Probes (e.g., Neuropixels) | Records action potentials from hundreds to thousands of neurons simultaneously. | Provides the foundational data—large-scale parallel neural recordings—necessary for population analysis [13]. |

| Genetically Encoded Calcium Indicators (e.g., GCaMP) | Optical recording of calcium influx, a proxy for neural activity, in large populations. | Enables longitudinal imaging of identified neuronal populations in behaving animals [12]. |

| Dimensionality Reduction Algorithms (e.g., PCA, UMAP) | Projects high-dimensional neural data into a lower-dimensional space for visualization and analysis. | Crucial for identifying state spaces, manifolds, and the dominant coding dimensions [13] [12]. |

| Demixed Principal Component Analysis (dPCA) | Decomposes neural population data into components related to specific task parameters (e.g., stimulus, choice). | Isolates the contributions of different task variables to the overall population activity, clarifying coding dimensions [13]. |

| Targeted Dimensionality Reduction (TDR) | Incorporates linear regression into neural population dynamics to identify encoding axes for task parameters. | Links task parameters directly to specific directions in the neural state space [13]. |

| Dynamic Models (e.g., LFADS) | Reconstructs latent neural dynamics from noisy spike train data. | Infers the underlying, denoised trajectories that the neural population follows during computation [7]. |

Implications for Optimization Research

The principles of population-level brain computation have directly inspired novel meta-heuristic optimization algorithms. The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) is a prime example, treating potential solutions as neural states within a population [4].

Core Bio-Inspired Strategies in NPDOA:

- Attractor Trending Strategy: Drives solution candidates (neural states) towards optimal decisions, ensuring exploitation capability. This mirrors the brain's dynamics converging to a stable state representing a decision [4].

- Coupling Disturbance Strategy: Deviates solution candidates from their current trajectories by coupling with other candidates, improving exploration ability. This mimics disruptive interactions between neural populations that prevent premature convergence [4].

- Information Projection Strategy: Controls communication between different solution candidates, enabling a dynamic transition from exploration to exploitation. This reflects the brain's gating of information flow between different neural circuits [4].

This bio-inspired approach demonstrates how the population doctrine—specifically the interplay between state spaces, dynamics, and subspaces—can provide a powerful framework for solving complex, non-linear optimization problems outside neuroscience [4].

Contemporary neuroscience is undergoing a paradigm shift from a single-neuron doctrine to a population doctrine, which posits that the fundamental computational unit of the brain is the population of neurons, not the individual cell [3] [7]. This shift is driven by technologies enabling simultaneous recording from large neural groups and theoretical frameworks for analyzing collective dynamics. This whitepaper examines a core mechanism of population coding: how behaviorally specific patterns of correlated activity between neurons enhance information transmission beyond what is available from individual neuron firing rates alone [14]. We detail experimental evidence from prefrontal cortex studies, provide a methodological guide for analyzing correlated codes, and discuss implications for understanding cognitive processes and their disruption in neurodevelopmental disorders. Framing this within the population doctrine's core concepts reveals how network structures optimize information processing, offering novel perspectives for therapeutic intervention.

The population doctrine represents a major theoretical shift in neurophysiology, drawing level with the long-dominant single-neuron doctrine [7]. This view holds that neural populations, not individual neurons, serve as the brain's fundamental computational unit. While population-level ideas have roots in classic concepts like Hebb's cell assemblies, recent advances in high-yield neural recording technologies have catalyzed their resurgence [7]. The population approach treats neural recordings not as random samples of isolated units but as low-dimensional projections of entire neural manifolds, enabling new insights into attention, decision-making, working memory, and executive function [3] [7].

This whitepaper explores a specific population coding mechanism: how correlated activity patterns enhance information transmission. We focus on a pivotal study of mouse prefrontal cortex during social behavior, which demonstrates that correlations between neurons carry additional information about socialization not reflected in individual activity levels [14]. This "synergy" in neural ensembles is diminished in a mouse model of autism, illustrating its clinical relevance. The following sections codify this within the population doctrine's framework, detailing core concepts, experimental evidence, analytical methods, and practical research tools.

Core Concepts of Population Analysis

Population-level analysis introduces a specialized conceptual framework for understanding neural computation [7]. The following core concepts provide a foundation for this perspective:

- State Spaces: The canonical analysis for population neurophysiology, a state space diagram plots the activity of each neuron in a recorded population against one or more other neurons. At each moment, the population occupies a specific neural state—a point in N-dimensional space (where N is the number of neurons), equivalent to a vector of firing rates. This spatial representation reveals patterns and relationships invisible in individual neuron histograms [7].

- Manifolds: Neural populations often exhibit activity patterns that occupy a low-dimensional, structured subspace within the high-dimensional state space. This neural manifold constrains the population's possible activity patterns, reflecting the network's underlying circuitry and computational principles [7].

- Coding Dimensions: Within a state space or manifold, specific dimensions may align with particular task variables, stimuli, or behaviors. Identifying these coding dimensions helps researchers understand how the population collectively represents information [7].

- Subspaces: Populations can multiplex information by encoding different variables in independent neural subspaces. This allows the same population to simultaneously represent multiple types of information without interference [7].

- Dynamics: As a behavior or cognitive process unfolds over time, the neural state traverses the manifold, forming a neural trajectory. These dynamics reveal how neural populations transform sensory inputs into motor outputs or support internal cognitive processes [7].

Information Encoding via Correlated Neural Activity

Empirical Evidence from Prefrontal Cortex

A critical study investigating population coding in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) of mice during social behavior provides direct evidence for the role of correlated activity in information enhancement [14]. Researchers used microendoscopic GCaMP calcium imaging to measure activity in large prefrontal ensembles while mice alternated between periods of solitude and social interaction.

Notably, the study developed an analytical approach using a neural network classifier and surrogate (shuffled) datasets to determine whether information was encoded in mean activity levels or in patterns of coactivity [14]. The key finding was that surrogate datasets preserving behaviorally specific patterns of correlated activity outperformed those preserving only behaviorally driven changes in activity levels but not correlations [14]. This demonstrates that social behavior elicits increases in correlated activity that are not explainable by the activity levels of the underlying neurons alone. Prefrontal neurons thus act collectively to transmit additional information about socialization via these correlations.

Disruption in Disease States

The functional significance of this correlated coding mechanism is underscored by its disruption in disease models. In mice lacking the autism-associated gene Shank3, individual prefrontal neurons continued to encode social information through their activity levels [14]. However, the additional information carried by patterns of correlated activity was lost [14]. This illustrates a crucial distinction: the ability of neuronal ensembles to collectively encode information can be selectively impaired even when single-neuron responses remain intact, revealing a specific mechanistic disruption potentially underlying behavioral deficits.

Methodological Framework for Analyzing Population Codes

Experimental Protocol for Detecting Correlated Codes

The following methodology, adapted from the cited prefrontal cortex study, provides a framework for investigating how correlated activity enhances population information [14]:

- Step 1: Neural Ensemble Recording: Use microendoscopic calcium imaging (e.g., GCaMP6f) or high-density electrophysiology to record activity from hundreds of neurons simultaneously in freely behaving animals. Ensure precise temporal alignment of neural data with behavioral annotations.

- Step 2: Behavioral Paradigm: Design a task alternating between the behavioral state of interest (e.g., social interaction) and a control state (e.g., solitary exploration). The protocol should include multiple trials and epochs to ensure statistical robustness.

- Step 3: Data Preprocessing: Extract calcium transients or spike times from raw signals. Convert fluorescence traces to binary event rasters, with most neurons typically active in less than 5% of frames [14]. Minimize neuropil influence by subtracting the mean signal from a surrounding annulus from each neuronal region of interest.

- Step 4: Surrogate Dataset Generation: Create two types of shuffled datasets: (1) preserves both firing rate changes and correlated activity patterns, (2) preserves firing rate changes but disrupts trial-by-trial coactivity patterns by shuffling timestamps across trials.

- Step 5: Neural Network Classification: Train a classifier (e.g., a neural network with a single linear hidden layer) to discriminate between behavioral states using population activity patterns. Unlike optimal linear classifiers, this architecture can detect states differing solely in coactivity patterns, not individual activity levels [14].

- Step 6: Information Comparison: Compare classifier performance between the two surrogate types. If classifiers trained on correlation-preserving surrogates significantly outperform those trained on rate-only surrogates, this indicates that correlated activity enhances transmitted information.

Quantitative Analysis of Population Codes

The experimental approach reveals specific quantitative signatures of correlated coding. The table below summarizes key metrics and findings from the prefrontal cortex study [14].

Table 1: Quantitative Signatures of Correlated Information Encoding in Neural Populations

| Metric | Description | Experimental Finding | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classifier Performance Differential | Difference in decoding accuracy between correlation-preserving vs. rate-only surrogate datasets. | Correlation-preserving surrogates showed statistically significant superior performance. | Correlations carry additional information about behavioral state beyond firing rates. |

| Ensemble Synergy | Information gain when decoding from neuron groups versus single neurons summed together. | Significant synergy detected during social interaction epochs. | Neurons transmit information collectively, not independently. |

| Correlation-Behavior Specificity | Magnitude of correlated activity changes between distinct behavioral states. | Social interaction specifically increased correlated activity within prefrontal ensembles. | Correlations are dynamically modulated by behavior, not a static network property. |

| State-Space Trajectory Geometry | Patterns of neural population activity in high-dimensional space. | Distinct trajectories emerged for different behavioral states based on coactivity patterns. | Collective neural dynamics encode behavioral information. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Research into population coding requires specialized tools and reagents. The following table details essential materials and their functions for conducting experiments in this domain.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Neural Population Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| GCaMP Calcium Indicators | Genetically encoded calcium sensors (e.g., GCaMP6f) for visualizing neural activity in vivo; expressed under cell-specific promoters (e.g., human synapsin). |

| Microendoscope Systems | Miniaturized microscopes (e.g., nVoke) for calcium imaging in freely behaving animals, enabling neural ensemble recording during natural behaviors. |

| Surrogate Dataset Algorithms | Computational methods for generating shuffled datasets that selectively preserve or disrupt specific signal aspects (firing rates vs. correlations). |

| Neural Network Classifiers | Machine learning models (particularly with linear hidden layers) capable of detecting information in coactivity patterns independent of firing rate changes. |

| Shank3 KO Mouse Model | Genetic model of autism spectrum disorder used to investigate disruption of synergistic information coding in neural populations. |

| Dimensionality Reduction Tools | Algorithms (PCA/ICA) for identifying active neurons from calcium imaging data and projecting high-dimensional neural data into lower-dimensional state spaces. |

Visualizing Population Coding Mechanisms

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate key concepts and experimental workflows in population coding research. The color palette adheres to the specified guidelines, ensuring proper contrast and accessibility.

Diagram 1: Information Flow in Population Coding. Population activity vectors form neural states decoded by classifiers to extract behavior information from both raw activity and correlation patterns.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Detecting Correlated Codes. Process for testing whether correlations enhance information using surrogate datasets and classifier comparisons.

The evidence demonstrates conclusively that correlated activity patterns between neurons within a population serve as a crucial coding dimension, transmitting additional information about behavior that is not accessible through individual neuron activity levels alone [14]. This mechanism, framed within the population doctrine, reveals that the brain's computational power emerges from collective, network-level phenomena [3] [7]. The disruption of this synergistic information in disease models like Shank3 KO mice provides a compelling paradigm for investigating neurodevelopmental disorders, suggesting that therapeutic strategies might target the restoration of collective neural dynamics rather than solely focusing on single-neuron function. As population-level analyses become increasingly sophisticated, they promise to unlock deeper insights into cognition's fundamental mechanisms and their pathological alterations.

This technical guide examines the population doctrine in theoretical neuroscience, which posits that the fundamental computational unit of the brain is the population of neurons, not the single cell [7]. We detail how dynamics within low-dimensional neural manifolds support core cognitive functions. The document provides a framework for leveraging these principles in optimization research, particularly for informing therapeutic development, by summarizing key quantitative data, experimental protocols, and essential research tools.

A major shift is occurring in neurophysiology, with the population doctrine drawing level with the long-dominant single-neuron doctrine [7]. This view asserts that computation emerges from the collective activity of neural populations, offering a more coherent explanation for complex cognitive phenomena than single-unit analyses can provide [15]. This perspective is crucial for optimization research as it provides a more accurate model of the brain's computational substrate, thereby offering better targets for cognitive therapeutics.

Core Concepts of Population Dynamics

The population-level analysis of neural data is built upon several key concepts that provide a foundation for understanding how cognitive functions are implemented.

State Spaces and Manifolds

The primary analytical framework shifts from the peristimulus time histogram (PSTH) to the neural state space [7]. In this framework:

- Neural State: The instantaneous pattern of activity across a recorded population of N neurons is represented as a single point in an N-dimensional state space.

- Neural Trajectory: The evolution of this population activity over time forms a trajectory through the state space, representing the dynamic computation underlying cognitive processes [7].

- Manifolds: The full, high-dimensional neural activity is often constrained to flow along a lower-dimensional neural manifold—a structured subspace that captures the essential features of the computation while ignoring noise and irrelevant dimensions [7].

Coding Dimensions and Subspaces

Neural populations encode multiple, sometimes independent, pieces of information simultaneously.

- Coding Dimensions: Specific directions in the state space that correspond to particular task variables (e.g., the value of a choice, the content of a memory).

- Subspaces: Independent neural dimensions allow the brain to process information in parallel. For instance, one subspace might encode a sensory stimulus, while another, orthogonal subspace prepares a motor response, preventing interference [7].

Dynamics

The time evolution of the neural state—the trajectory—is central to understanding cognition. Neural dynamics describe how the population activity evolves according to internal rules, transforming sensory inputs into motor outputs and supporting internal cognitive processes like deliberation and memory maintenance [7] [15]. Sudden jumps in these trajectories may correspond to cognitive discontinuities, such as a sudden change in decision or belief [7].

Quantitative Data on Population Coding in Cognition

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings linking population dynamics to specific cognitive functions.

Table 1: Population Coding Metrics and Their Cognitive Correlates

| Metric | Definition | Relevant Cognitive Function | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| State Vector Magnitude | Sum of activity across all neurons in a population [7]. | Working Memory | In inferotemporal cortex (IT), magnitude predicts how well an object will be remembered later [7]. |

| State Vector Direction | Pattern of activity across neurons, independent of overall magnitude [7]. | Object Recognition | In IT, the direction of the state vector encodes object identity [7]. |

| Inter-state Distance | Measure of dissimilarity between two neural states (e.g., Euclidean, angle, Mahalanobis) [7]. | Decision-Making, Learning | Sudden jumps in neural state across trials may reflect abrupt changes in policy or belief, aligning with hierarchical models of decision-making [7]. |

| Attractor Basin Depth | Stability of a neural state, determined by connection strength and experience [15]. | Semantic Memory | Deeper basins correspond to more typical or frequently encountered concepts (e.g., "dog" vs. "platypus"). Brain damage shallowes basins, leading to errors [15]. |

Table 2: Summary of Contrast Requirements for Data Visualization (WCAG)

| Content Type | Minimum Ratio (Level AA) | Enhanced Ratio (Level AAA) |

|---|---|---|

| Body Text | 4.5:1 [16] [17] | 7:1 [16] [17] |

| Large-Scale Text (≥18pt or ≥14pt bold) | 3:1 [16] [17] | 4.5:1 [16] [17] |

| User Interface Components & Graphical Objects | 3:1 [16] [17] | Not Defined |

Experimental Protocols for Probing Population Dynamics

This section details methodologies for recording and analyzing population-level neural activity to investigate cognition.

High-Yield Neural Recording

- Objective: To simultaneously record the activity of hundreds to thousands of neurons from relevant brain regions during cognitive tasks.

- Protocol:

- Subject Preparation: Implant high-density electrode arrays (e.g., Neuropixels) or perform large-scale calcium imaging (e.g., via two-photon microscopy) in the brain region of interest (e.g., prefrontal cortex, hippocampus).

- Task Design: Subjects perform a cognitive task (e.g., a delayed match-to-sample task for working memory, a two-alternative forced choice for decision-making).

- Data Acquisition: Simultaneously record spike times or fluorescence signals from the neuronal population, synchronized with precise task event timestamps.

Dimensionality Reduction and Manifold Identification

- Objective: To project high-dimensional neural data into a lower-dimensional space to reveal underlying structure.

- Protocol:

- Preprocessing: Bin neural data into time bins (e.g., 10-50ms) to create a data matrix of firing rates (neurons x time).

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify the dominant dimensions of population variance.

- Visualization & Analysis: Plot the neural trajectories in the state space defined by the top 2-3 principal components. Analyze how trajectories separate for different cognitive conditions or task variables.

Decoding Cognitive Variables

- Objective: To quantify how much information a neural population carries about a specific cognitive variable.

- Protocol:

- Labeling: Assign a cognitive variable (e.g., decision, value, memorized location) to each time point or trial.

- Model Training: Train a linear decoder (e.g., linear regression, support vector machine) to predict the cognitive variable from the population activity pattern.

- Validation: Use cross-validation to assess decoding accuracy. High accuracy indicates the variable is robustly encoded in the population code.

Visualization of Population Dynamics and Workflows

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz using the specified color palette and contrast rules, illustrate core concepts and experimental processes.

From Single Neurons to Population State Space

Cognitive Process as a Neural Trajectory

Experimental Workflow for Population Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and tools essential for research in neural population dynamics.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| High-Density Electrode Arrays (e.g., Neuropixels) | Enable simultaneous recording of hundreds to thousands of single neurons across multiple brain regions, providing the raw data for population analysis [7]. |

| Calcium Indicators (e.g., GCaMP) | Genetically encoded sensors that fluoresce in response to neuronal calcium influx, allowing optical measurement of neural activity in large populations, often via two-photon microscopy. |

| Viral Vectors (e.g., AAVs) | Used for targeted delivery of genetic material, such as calcium indicators or optogenetic actuators, to specific cell types and brain regions. |

| Optogenetic Actuators (e.g., Channelrhodopsin) | Light-sensitive proteins that allow precise manipulation of specific neural populations to test causal relationships between population activity and cognitive function. |

| Dimensionality Reduction Software (e.g., PCA, t-SNE) | Computational tools to project high-dimensional neural data into lower-dimensional state spaces for visualization and analysis of manifolds and trajectories [7]. |

| Linear Decoders (e.g., Wiener Filter, Linear Regression) | Computational models used to "decode" cognitive variables (e.g., attention, decision) from population activity, quantifying the information content of the neural code. |

| Theoretical Network Models (e.g., Pattern Associators) | Computational simulations (e.g., connectionist models) that embody population-level principles to test hypotheses and account for behavioral phenomena [15]. |

Bridging Theory and Practice: Population-Inspired Optimization Frameworks

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) represents a novel class of swarm intelligence meta-heuristic algorithms directly inspired by the population doctrine in theoretical neuroscience [18] [4]. It simulates the activities of interconnected neural populations in the brain during cognitive and decision-making processes, translating these dynamics into an effective optimization framework [4]. Unlike metaphor-based algorithms that mimic superficial animal behaviors, NPDOA is grounded in the computational principles of brain function, where neural populations process information and converge on optimal decisions through well-defined dynamical systems [4] [19].

In theoretical neuroscience, the population doctrine posits that cognitive functions emerge from the collective activity of neural populations rather than individual neurons [4]. The NPDOA operationalizes this doctrine by treating each potential solution to an optimization problem as a distinct neural population. Within each population, every decision variable corresponds to a neuron, and its numerical value represents that neuron's firing rate [4]. The algorithm simulates how the neural state (the solution) of each population evolves over time according to neural population dynamics, driving the collective system toward optimal states [4]. This bio-inspired approach provides a principled method for balancing the exploration of new solution areas and the exploitation of known promising regions, a central challenge in optimization research [4].

Core Algorithmic Mechanics

The NPDOA framework is built upon three foundational strategies derived from neural computation.

Attractor Trending Strategy

This strategy is responsible for the algorithm's exploitation capability. In neural dynamics, an attractor is a stable state toward which a neural network evolves. Similarly, in NPDOA, the attractor trending strategy drives neural populations (solutions) toward optimal decisions (attractors) [18] [4]. This process ensures that once promising regions of the search space are identified, the algorithm can thoroughly search these areas by guiding solutions toward local or global attractors, analogous to how neural circuits converge to stable states representing decisions or memories [4].

Coupling Disturbance Strategy

This mechanism provides the algorithm's exploration ability. Neural populations in the brain exhibit complex coupling interactions that can disrupt stable states. In NPDOA, the coupling disturbance strategy deliberately deviates neural populations from their current attractors by simulating interactions with other neural populations [18] [4]. This disturbance prevents premature convergence to local optima by maintaining population diversity and enabling the exploration of new regions in the solution space, mirroring how neural coupling can push brain networks away from stable states to explore alternative processing pathways [4].

Information Projection Strategy

This strategy regulates the transition between exploration and exploitation. In neural systems, information projection between different brain regions controls which neural pathways dominate processing. Similarly, in NPDOA, the information projection strategy modulates communication between neural populations, thereby controlling the relative influence of the attractor trending and coupling disturbance strategies [18] [4]. This dynamic regulation allows the algorithm to shift emphasis from broad exploration early in the search process to focused exploitation as it converges toward optimal solutions [4].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow and core components of the NPDOA:

Experimental Validation & Performance Analysis

Benchmark Function Evaluation

The NPDOA has been rigorously evaluated against standard benchmark functions and practical engineering problems. Quantitative results demonstrate its competitive performance compared to established meta-heuristic algorithms [4]. The following table summarizes key quantitative results from benchmark evaluations:

Table 1: NPDOA Performance on Benchmark Functions

| Metric | Performance | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Convergence Accuracy | High precision on CEC benchmarks | Outperformed 9 state-of-the-art metaheuristic algorithms [4] |

| Balance of Exploration/Exploitation | Effective balance through three core strategies | Superior to classical algorithms (PSO, GA) and recent algorithms (WOA, SSA) [4] |

| Computational Efficiency | Polynomial time complexity: O(NP² · D) [4] | Competitive with other population-based algorithms [4] |

| Practical Application | Verified on engineering design problems [4] | Effective on compression spring, cantilever beam, pressure vessel, and welded beam designs [4] |

Enhanced Variant: INPDOA for Medical Prognostics

The algorithm's effectiveness has been further demonstrated through an Improved NPDOA (INPDOA) variant developed for automated machine learning (AutoML) in medical prognostics [19] [20]. This enhanced version was applied to predict outcomes in autologous costal cartilage rhinoplasty (ACCR) using a retrospective cohort of 447 patients [19] [20].

Table 2: INPDOA Performance in Medical Application (ACCR Prognosis)

| Performance Metric | Result | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1-Month Complication Prediction (AUC) | 0.867 [19] [20] | Superior to traditional models (LR, SVM) and ensemble learners (XGBoost, LightGBM) [19] |

| 1-Year ROE Score Prediction (R²) | 0.862 [19] [20] | High explanatory power for long-term aesthetic outcomes [19] |

| Key Predictors Identified | Nasal collision, smoking, preoperative ROE scores [19] [20] | Clinically interpretable feature importance [19] |

| Clinical Impact | Net benefit improvement over conventional methods [19] [20] | Validated utility in real-world medical decision-making [19] |

The INPDOA framework for this medical application employed a sophisticated encoding scheme where solution vectors integrated model type selection, feature selection, and hyperparameter optimization into a unified representation [19] [20]. The fitness function balanced predictive accuracy, feature sparsity, and computational efficiency through dynamically adapted weights [19] [20].

The following diagram illustrates the INPDOA-enhanced AutoML framework for medical prognostics:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Components for NPDOA Implementation

| Component | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Suites | Algorithm validation and comparison | CEC 2017, CEC 2022 test functions [21] |

| Computational Framework | Experimental platform and evaluation | PlatEMO v4.1 [4] |

| Performance Metrics | Quantitative algorithm assessment | Friedman ranking, Wilcoxon rank-sum test [21] |

| Engineering Problem Set | Real-world validation | Compression spring, cantilever beam, pressure vessel, welded beam designs [4] |

| Medical Validation Framework | Clinical application verification | ACCR patient cohort (n=447) with 20+ clinical parameters [19] [20] |

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm represents a significant advancement in bio-inspired optimization by directly leveraging principles from theoretical neuroscience rather than superficial metaphors. Its three core strategies—attractor trending, coupling disturbance, and information projection—provide an effective mechanism for balancing exploration and exploitation in complex search spaces [18] [4]. Experimental results across benchmark functions and practical applications, including medical prognostics, demonstrate that NPDOA and its variants consistently achieve competitive performance against state-of-the-art optimization methods [4] [19] [20].

The algorithm's foundation in population doctrine from neuroscience offers a principled approach to optimization that aligns with how biological neural systems efficiently process information and converge on optimal decisions [4]. This direct bio-inspired methodology opens promising directions for future optimization research, particularly in domains requiring robust performance across diverse problem structures and in applications where interpretability and biological plausibility are valued alongside raw performance.

The population doctrine represents a paradigm shift in theoretical neuroscience, positing that the fundamental computational unit of the brain is not the individual neuron, but the neural population [7]. This perspective reframes neural activity as a dynamic system operating in a high-dimensional state space, where the collective behavior of neuronal ensembles gives rise to cognition and decision-making [7]. In this framework, the pattern of activity across all neurons at a given moment forms a neural state vector that evolves along trajectories through state space, encoding information not just in the firing rates of individual cells, but in the holistic configuration of the population [7].