Evaluating Neurotechnology Safety and Efficacy: A Comprehensive Framework for Researchers and Developers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the safety and efficacy evaluation of neurotechnologies, from foundational concepts to advanced validation strategies.

Evaluating Neurotechnology Safety and Efficacy: A Comprehensive Framework for Researchers and Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the safety and efficacy evaluation of neurotechnologies, from foundational concepts to advanced validation strategies. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the current regulatory landscape, innovative testing methodologies like sandbox environments, and comparative analyses of electrical stimulation and pharmacological agents. The content addresses critical challenges in the field, including navigating regulatory pathways for direct-to-consumer devices and implantable systems, and offers insights into optimizing clinical trial design and post-market surveillance to ensure the reliable and ethical translation of neurotechnologies into clinical practice.

Neurotechnology Fundamentals: Core Principles and the Regulatory Landscape

The field of neurotechnology is undergoing a rapid transformation, evolving from a specialized research discipline into a burgeoning industry poised to revolutionize medicine and human-machine interaction. At its core, neurotechnology encompasses a spectrum of tools designed to monitor, analyze, and modulate neural activity. This spectrum ranges from non-invasive systems that record brain activity through the skull to fully implanted devices that interface directly with neural tissue. Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) form a critical segment of this spectrum, operating as systems that measure central nervous system activity and convert it into artificial outputs that replace, restore, enhance, supplement, or improve natural neural outputs [1]. These systems create a real-time bidirectional information gateway between the brain and external devices, offering unprecedented potential for restoring function in patients with neurological disorders and injuries [2].

Understanding the technical capabilities, applications, and limitations of each category within the neurotechnology spectrum is essential for researchers, clinicians, and developers aiming to advance the field or apply these tools in therapeutic contexts. The choice between non-invasive, semi-invasive, and invasive technologies involves careful trade-offs between signal fidelity, risk tolerance, and intended application. This guide provides a structured comparison of these modalities, supported by current experimental data and methodological protocols, to inform evidence-based evaluation of their safety and efficacy.

Categorizing the Neurotechnology Spectrum

Neurotechnologies are fundamentally categorized based on their physical relationship to neural tissue, which directly determines their signal quality, surgical risk, and suitable applications. The three primary categories are:

Non-invasive BCIs: Placed on the scalp or skin surface external to the skull. These systems record large-scale brain activity (e.g., via EEG, fMRI, fNIRS) without penetrating the body, minimizing surgical risks and ethical concerns but suffering from lower signal quality due to skull interference and susceptibility to external noise [3].

Semi-invasive BCIs: Positioned on the brain surface beneath the skull (epidural or subdural). This approach offers better signal quality than non-invasive methods by detecting local field potentials without piercing brain tissue, but still requires craniotomy for electrode placement [3].

Invasive BCIs: Implanted directly into brain tissue, penetrating the cortex. These systems provide the highest signal quality by recording single neuron activity (action potentials) with precise spatial resolution, but require complex brain surgery that carries risks of infection, tissue damage, and scar formation [2] [3].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of BCI Approaches

| Characteristic | Non-invasive BCI | Semi-invasive BCI | Invasive BCI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Low (scales to centimeters) | Moderate (millimeter scale) | High (micron scale for single neurons) |

| Temporal Resolution | Moderate (milliseconds) | High (milliseconds) | Very High (sub-millisecond) |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Lowest | Moderate | Highest |

| Surgical Risk | None | Moderate (craniotomy required) | High (brain penetration) |

| Long-term Stability | Highest | Moderate | Limited (scarring, signal degradation) |

| Information Transfer Rate | Lowest (~5-25 bits/minute) | Moderate (~40-60 bits/minute) | Highest (~100-200 bits/minute) |

| Primary Signal Types | EEG, MEG, fNIRS, fMRI | ECoG, sEEG | Single/Multi-unit spikes, Local Field Potentials |

Technical Performance and Market Landscape

Performance Benchmarks and Clinical Applications

The technical performance differences between BCI categories translate directly into their clinical applications and efficacy. Non-invasive systems have found significant utility in stroke rehabilitation, where a 2025 umbrella review of systematic analyses demonstrated that BCI-combined treatment can improve upper limb motor function and quality of daily life for stroke patients, particularly those in the subacute phase, with good safety profiles [4]. However, these systems face challenges including signal interference from noise, "BCI illiteracy" where a significant proportion of users struggle to achieve effective control, and substantial variation in therapeutic efficacy across patients [5].

Invasive BCIs have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in restoring communication for severely paralyzed individuals. Recent research presented at Neuroscience 2025 documented a paralyzed man with ALS who used a chronic intracortical BCI independently at home for over two years, controlling his home computer, working full-time, and communicating more than 237,000 sentences with up to 99% word output accuracy at approximately 56 words per minute [6]. This exemplifies the high-performance potential of invasive approaches for severe disabilities.

Semi-invasive approaches offer a middle ground, with technologies like Precision Neuroscience's "Layer 7" ultra-thin electrode array designed to slip between the skull and brain with minimal invasiveness. This approach aims to capture high-resolution signals without piercing brain tissue, and in April 2025 received FDA 510(k) clearance for commercial use with implantation durations of up to 30 days, initially focused on enabling communication for patients with ALS [1].

Table 2: Current Market Leaders and Their Technological Approaches

| Company/Institution | Technology Type | Key Technology | Primary Application Focus | Development Status (2025) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuralink | Invasive | Ultra-high-bandwidth implantable chip with thousands of micro-electrodes | Severe paralysis, communication | Human trials with 5 participants [1] |

| Synchron | Semi-invasive | Stentrode (endovascular, delivered via blood vessels) | Paralysis, computer control | Clinical trials, partnership with Apple and NVIDIA [1] |

| Blackrock Neurotech | Invasive | Neuralace (flexible lattice electrode), Utah array | Paralysis, communication | Expanding trials, including in-home tests [1] |

| Precision Neuroscience | Semi-invasive | Layer 7 (ultra-thin electrode array on brain surface) | Communication for ALS | FDA 510(k) cleared for up to 30 days implantation [1] |

| Paradromics | Invasive | Connexus BCI (modular array with 421 electrodes) | Speech restoration | First-in-human recording, planning clinical trial [1] |

| Johns Hopkins APL | Non-invasive | Digital holographic imaging (records neural tissue deformations) | Fundamental research, future BCI applications | Preclinical validation [7] |

Market Outlook and Adoption Trends

The neurotechnology market is experiencing significant growth, driven by increasing investment and technological advancement. According to industry analysis, the global BCI market is forecast to grow to over US$1.6 billion by 2045, representing a compound annual growth rate of 8.4% since 2025 [8]. The addressable market in healthcare alone is substantial, with an estimated 5.4 million people in the United States living with paralysis that impairs their ability to use computers or communicate [1]. Initial market growth is driven primarily by applications in paralysis, rehabilitation, and prosthetics.

Private investment in neurotechnology has surged, with Neuralink reportedly raising over $650 million to date, and Paradromics securing more than $105 million in venture funding plus $18 million from NIH and DARPA grants as of February 2025 [1]. This funding landscape reflects strong confidence in the commercial potential of advanced BCI technologies, particularly invasive and semi-invasive approaches aimed at addressing severe neurological disabilities.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Non-Invasive Brain-Spine Interface for Motor Rehabilitation

Recent research has demonstrated innovative approaches to combining non-invasive technologies for rehabilitation. A 2025 study published in the Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation developed and evaluated a non-invasive brain-spine interface (BSI) using EEG and transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation (tSCS) for motor rehabilitation [9].

Objective: To detect movement intention from EEG correlates and use this to trigger spinal cord stimulation timed with voluntary effort, creating a closed-loop rehabilitation system.

Participant Recruitment: 17 unimpaired participants (10 male, 7 female, average age 25.8 ± 3.9 years) with no acute or chronic pain conditions, neurological diseases, or implanted metal [9].

Experimental Setup:

- EEG data recorded at 500 Hz using a wireless 32-channel headset positioned over central-medial areas according to the 10-10 system.

- Electromyography (EMG) signals recorded at 1482 Hz using wireless surface electrodes placed bilaterally on lower limb muscles.

- Participants performed cued right knee extensions, imagined movements, and uncued movements.

Signal Processing and Decoding:

- Initiation of knee extension was associated with event-related desynchronization in central-medial cortical regions at frequency bands between 4-44 Hz.

- A linear discriminant analysis (LDA) decoder using μ (8-12 Hz), low β (16-20 Hz), and high β (24-28 Hz) frequency bands was implemented.

- The decoder achieved an average area under the curve (AUC) of 0.83 ± 0.06 during cued movement tasks offline.

Closed-Loop Implementation:

- With real-time decoder-modulated tSCS, the neural decoder performed with an average AUC of 0.81 ± 0.05 on cued movement and 0.68 ± 0.12 on uncued movement.

- The system successfully provided closed-loop control of tSCS timed with movement intention [9].

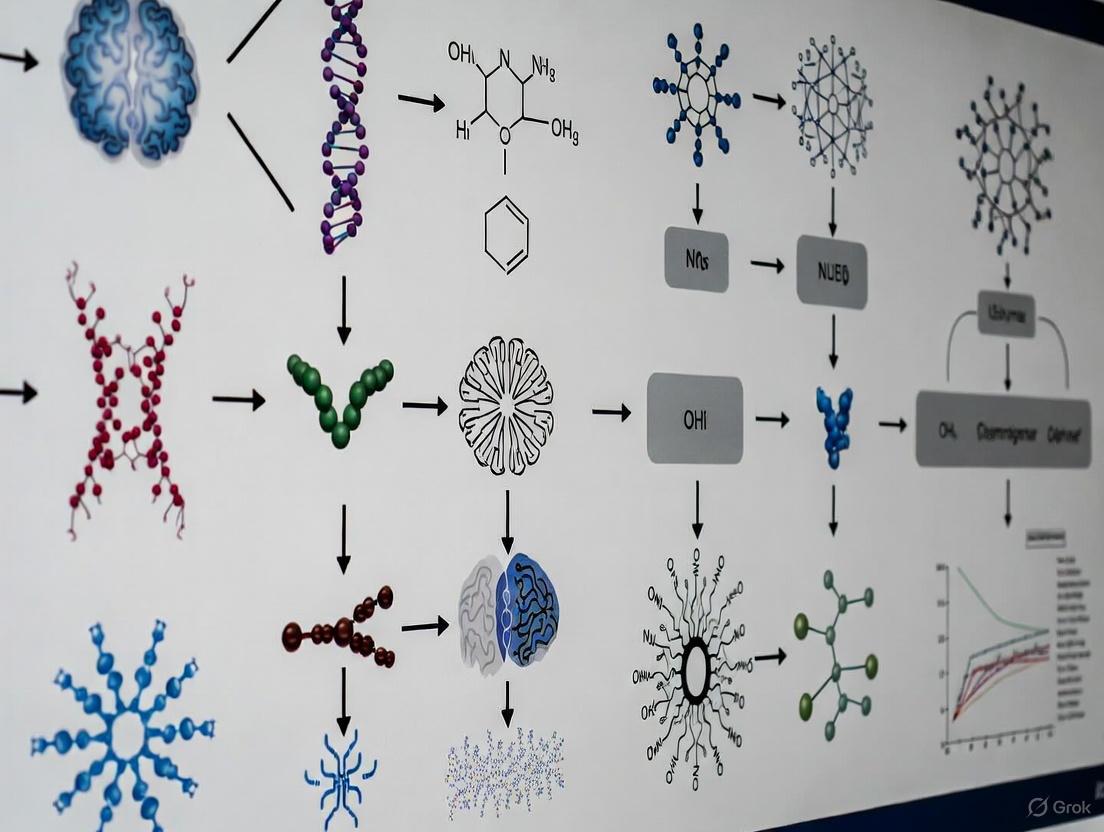

The following workflow diagram illustrates the experimental setup and closed-loop control system:

Diagram 1: Workflow of non-invasive brain-spine interface experimental protocol for motor rehabilitation.

Protocol: Intracortical Microstimulation for Somatosensory Restoration

For invasive approaches, intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) has emerged as a promising technique for restoring tactile sensations. A foundational study presented at Neuroscience 2025 provided crucial long-term safety and efficacy data [6].

Objective: To evaluate the safety and stability of ICMS via microelectrode interfaces in the somatosensory cortex over extended periods.

Participant Profile: Five participants implanted with microelectrode arrays in the somatosensory cortex, receiving millions of electrical stimulation pulses over a combined 24 years.

Methodology:

- Microelectrode arrays were chronically implanted in the somatosensory cortex.

- Electrical stimulation parameters were carefully controlled to evoke tactile sensations without causing tissue damage.

- Subjective reports of sensation quality and location were collected.

- Neural interface stability and electrode functionality were monitored regularly.

Results:

- ICMS evoked high-quality, stable tactile sensations in the hand without serious adverse effects.

- More than half of the electrodes continued to function reliably after 10 years in one participant.

- This study represents the most extensive evaluation of ICMS in humans and establishes that ICMS is safe over long periods [6].

The signaling pathway for this invasive approach can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 2: Bidirectional signaling pathway for invasive intracortical microstimulation and recording.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for BCI Development and Evaluation

| Category | Specific Tool/Reagent | Research Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Acquisition | gNautilus 32-channel EEG headset (gTec) | Records cortical activity from scalp surface | Non-invasive BCI for motor intention detection [9] |

| Microelectrode arrays (Utah array, Neuropixels) | Records single-neuron activity in cortex | High-fidelity neural decoding for speech and movement [1] [6] | |

| Trigno Avanti wireless EMG sensors (Delsys) | Records muscle activity for validation | Correlating neural decoding with actual movement [9] | |

| Signal Processing | BCI2000 software platform | General-purpose BCI research platform | Real-time signal processing and experiment control [9] |

| Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) decoder | Classifies neural signals into intended commands | Detecting movement onset from sensorimotor rhythms [9] | |

| Kalman filter, Bayesian decoders | Estimates continuous movement parameters | Predicting movement trajectory from motor cortex activity [2] | |

| Neuromodulation | DS8R constant current stimulator (Digitimer) | Precisely controls electrical stimulation amplitude | Transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation [9] |

| Intracortical microstimulation arrays | Provides focal electrical stimulation to neural tissue | Restoring artificial touch sensations [6] | |

| Experimental Control | NI-DAQ digital input/output board (National Instruments) | Synchronizes multiple data acquisition systems | Temporal alignment of EEG, EMG, and stimulus markers [9] |

| Digital pulse train generator (DG2A, Digitimer) | Precisely times stimulation delivery | Ensuring accurate closed-loop stimulation timing [9] | |

| 3-(Pyridin-3-yl)prop-2-enamide | 3-(Pyridin-3-yl)prop-2-enamide | RUO | Supplier | 3-(Pyridin-3-yl)prop-2-enamide for research. Explore its applications in kinase & cancer studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| (4-Nitro-benzyl)-phosphonic acid | (4-Nitro-benzyl)-phosphonic Acid | High Purity | (4-Nitro-benzyl)-phosphonic acid for RUO. A phosphatase & kinase research tool. High-purity, for biochemical studies only. Not for human, veterinary, or household use. | Bench Chemicals |

Safety and Efficacy Evaluation Framework

Risk-Benefit Analysis Across the Spectrum

Each category within the neurotechnology spectrum presents distinct safety considerations that must be balanced against potential efficacy. Non-invasive systems demonstrate favorable safety profiles, with a 2025 umbrella review of BCI for stroke rehabilitation confirming good safety, particularly for subacute stroke patients [4]. The primary limitations relate to efficacy rather than safety, including signal quality issues and variable patient responsiveness.

Semi-invasive approaches moderate risk while improving signal quality. The Stentrode by Synchron, which is delivered via blood vessels, reported no serious adverse events or blood vessel blockages in a four-patient trial after 12 months, with the device staying in place [1]. This suggests acceptable safety for carefully selected patients.

Invasive technologies carry the highest risks but offer superior performance. The most extensive safety evaluation of intracortical microstimulation in humans demonstrated maintained safety over a combined 24 years across five participants, with more than half of electrodes continuing to function reliably after 10 years in one participant [6]. However, invasive implants always carry risks of infection, hemorrhage, and neurological deficits, with tissue scarring potentially limiting long-term stability [3].

Emerging Innovations and Future Directions

The neurotechnology field continues to evolve with innovations addressing current limitations. Johns Hopkins APL researchers have demonstrated a breakthrough in non-invasive, high-resolution recording using digital holographic imaging to detect neural tissue deformations at nanometer scale, potentially enabling future non-invasive BCIs with improved signal quality [7]. Similarly, magnetomicrometry—implanting small magnets in muscle tissue tracked by external magnetic field sensors—has shown potential for more intuitive prosthetic control than traditional neural approaches [6].

The BRAIN Initiative has outlined a comprehensive vision spanning from 2016-2026, focusing initially on technology development and shifting toward integrating technologies to make fundamental discoveries about brain function [10]. This coordinated effort continues to drive innovation across the neurotechnology spectrum.

The neurotechnology spectrum encompasses complementary toolsets with distinct risk-benefit profiles suited to different applications and patient populations. Non-invasive systems offer safety and accessibility for rehabilitation and basic research, while invasive approaches provide unprecedented fidelity for severe disabilities. Semi-invasive technologies represent a promising middle ground, with recent regulatory approvals signaling their growing clinical viability. As the field advances, ethical considerations around neural enhancement, data privacy, and appropriate use of brain data will require ongoing attention from the research community [10]. The continued convergence of engineering, neuroscience, and clinical medicine across this spectrum promises to transform our approach to neurological disorders and human-machine interaction in the coming decades.

The Imperative of Rigorous Safety and Efficacy Evaluation

The rapid emergence of neurotechnology represents a paradigm shift in neurology and psychiatry, offering unprecedented potential for treating debilitating conditions. By 2026, the neurotechnology market is estimated to be worth £14 billion, reflecting substantial investment and innovation in this sector [11]. These technologies, defined by their direct connection with the nervous system, interface with the most complex and least understood organ in the human body [12]. The powerful capabilities of neurotechnology—to both read from and write into the brain—create an ethical and clinical imperative for rigorous safety and efficacy evaluation before these interventions can be responsibly integrated into clinical practice [12]. This evaluation framework must balance the promise of life-changing therapeutic benefits with meticulous assessment of risks, from physical safety to profound ethical considerations surrounding mental privacy and personal identity [12] [13].

The Expanding Neurotechnology Landscape

Neurotechnology encompasses a diverse range of invasive and non-invasive approaches, from well-established deep brain stimulation (DBS) to emerging closed-loop systems and brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). A recent horizon scan identified 81 unique neurotechnologies in development, with 23 targeting mental health conditions, 31 focused on healthy aging, and 42 addressing physical disability [11]. This scan revealed that the majority (79%) of these technologies do not yet have FDA approval, and most (77.4%) remain in earlier stages of development (pilot/feasibility studies), with only 22.6% at pivotal or post-market stages [11].

The table below illustrates the current development landscape across key application areas:

Table 1: Neurotechnology Development Pipeline by Therapeutic Area

| Therapeutic Area | Technologies in Development | FDA Approval Status | Development Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health | 23 | 21% approved | Mostly early-stage |

| Healthy Aging | 31 | Limited approval | Mixed stages |

| Physical Disability | 42 | Emerging approvals | Later-stage focus |

Data synthesized from horizon scan of 81 neurotechnologies [11]

Digital elements are common features across these technologies, including software, apps, and connectivity to other devices. Interestingly, despite the prominence of AI in discussions of neurotechnology, only three of the 81 identified technologies had an identifiable AI component [11]. This disconnect between technological hype and current capabilities underscores the need for realistic evaluation frameworks.

Comparative Efficacy Analysis: Methodologies and Metrics

Endovascular Treatments for Intracranial Stenosis

Symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis (sICAS) is a common cause of ischemic stroke, particularly among Asian, Black, and Hispanic populations [14]. A recent single-center study compared the safety and efficacy of different endovascular treatments in 154 patients with sICAS, providing robust comparative data on bare metal stents (BMS), drug-coated balloons (DCB), and drug-eluting stents (DES) [14].

Experimental Protocol: The study involved patients with ≥70% stenosis of major intracranial arteries who experienced TIA or stroke despite maximal medical therapy. Patients were assigned to BMS, DCB, or DES groups based on lesion characteristics and operator experience. All patients received pre-procedural aggressive medical therapy including antiplatelet agents and statins. Technical success was defined as residual stenosis ≤30% after angioplasty. Primary endpoints included incidence of in-stent restenosis (ISR) at 6 months, periprocedural complications, stroke recurrence rates, and modified Rankin scores (mRS) at multiple timepoints [14].

Table 2: Comparative Outcomes for Different Endovascular Treatments

| Treatment Modality | Periprocedural Complications | 6-Month Restenosis Rate | Stroke Recurrence During Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bare Metal Stent (BMS) | 11.3% | 35.2% | 7.0% (5/71 patients) |

| Drug-Coated Balloon (DCB) | 8.0% | 6.0% | 2.0% (1/50 patients) |

| Drug-Eluting Stent (DES) | 6.1% | 9.1% | 3.0% (1/33 patients) |

Data from study of 154 patients with symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis [14]

Multivariate logistic regression analysis identified both endovascular treatment strategy and vessel distribution as significant independent risk factors for ISR within 6 months, with DES and DCB demonstrating superior performance compared to BMS [14].

Gene Therapy for Spinal Muscular Atrophy

The Phase III STEER trial investigated intrathecal onasemnogene abeparvovec (OAV101 IT), an investigational gene replacement therapy for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), providing a robust example of rigorous efficacy evaluation in neuromodulation [15].

Experimental Protocol: This registrational study employed a sham-controlled design in treatment-naïve patients with SMA Type 2, aged 2 to <18 years, who could sit but had never walked independently. A total of 126 patients were randomized to receive either OAV101 IT (n=75) or a sham procedure (n=51). The primary endpoint was change from baseline to 52 weeks in Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale Expanded (HFMSE) score, a gold standard for SMA-specific assessment of motor function. At the end of the 52-week period, all eligible patients crossed over to receive the active treatment [15].

Key Efficacy Results: The trial met its primary endpoint, with OAV101 IT demonstrating a statistically significant 2.39-point improvement on the HFMSE compared to 0.51 points in the sham group (overall difference: 1.88 points; P=0.0074). All secondary endpoints consistently favored OAV101 IT, though they did not achieve statistical significance due to the pre-planned multiple testing procedure [15].

A companion Phase IIIb STRENGTH study evaluated OAV101 IT in patients who had discontinued previous SMA treatments (nusinersen or risdiplam), demonstrating stabilization of motor function over 52 weeks of follow-up, with an increase from baseline in HFMSE least squares total score of 1.05 [15].

Safety Assessment Frameworks Across Modalities

Long-Term Safety Profiling

Comprehensive safety evaluation requires extended follow-up periods to identify potential long-term risks. The five-year safety and efficacy outcomes of ofatumumab in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis exemplify this approach [16].

Experimental Protocol: Safety was analyzed in 1,969 participants who received at least one dose of ofatumumab across multiple trial phases (ASCLEPIOS I/II, APLIOS, APOLITOS, or ALITHIOS). Researchers tracked exposure-adjusted incidence rates of adverse events, serious adverse events, serious infections, and malignancies over the five-year period [16].

Safety Outcomes: The analysis revealed consistent exposure-adjusted incidence rates per 100 patient-years for adverse events (124.65), serious adverse events (4.68), serious infections (1.63), and malignancies (0.32) through five years of follow-up, with no new safety signals identified. With ofatumumab treatment up to five years, over 80% of patients remained free of 6-month confirmed disability worsening [16].

Ethical Dimensions of Safety in Closed-Loop Systems

Closed-loop (CL) neurotechnology, which dynamically adapts to patients' neural states in real-time, introduces unique safety considerations that extend beyond conventional physical risks. A scoping review of 66 clinical studies involving CL systems revealed significant gaps in how ethical dimensions of safety are addressed [13].

Methodological Framework: The review analyzed peer-reviewed research on human participants to evaluate both the presence and depth of ethical engagement. The analysis employed thematic coding to identify key ethical themes, including beneficence (maximizing benefits while minimizing risks) and nonmaleficence (avoiding harm) [13].

Findings on Safety Reporting: Among the 66 reviewed studies, 56 addressed adverse effects, ranging from minor discomfort to severe complications requiring device removal. However, ethical considerations were typically addressed only implicitly, folded into technical or procedural discussions without structured analysis. Only one study included a dedicated assessment of ethical considerations, suggesting that ethics is not currently a central focus in most ongoing clinical trials of CL systems [13].

The review identified a concerning gap between regulatory compliance and meaningful ethical reflection, particularly regarding psychological safety, personal identity, and mental privacy. This highlights the need for safety evaluation frameworks that address both physical and ethical dimensions of risk [13].

Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Rigorous evaluation of neurotechnologies requires specialized research reagents and methodologies tailored to assess both functional outcomes and safety parameters across diverse neurological conditions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies for Neurotechnology Evaluation

| Research Tool | Application | Function in Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale Expanded (HFMSE) | Spinal Muscular Atrophy | Gold standard assessment of motor function and disease progression [15] |

| Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) | Stroke and Intracranial Stenosis | Evaluates disability levels and functional independence in daily activities [14] |

| Responsive Neurostimulation (RNS) System | Epilepsy | Closed-loop system detecting epileptiform activity and delivering targeted stimulation [13] |

| Digital Subtraction Angiography (DSA) | Intracranial Stenosis | Visualizes blood vessels to quantify stenosis degree and guide interventions [14] |

| Quality of Life in Epilepsy (QOLIE) Inventory | Epilepsy and Neurostimulation | Assesses quality of life impact beyond seizure frequency reduction [13] |

| Local Field Potentials (LFPs) | Adaptive Deep Brain Stimulation | Neural signals used as biomarkers for real-time adjustment of stimulation parameters [13] |

The selection of appropriate assessment tools must align with the specific neurotechnology and condition being studied. For motor function evaluation in SMA, the HFMSE provides validated, disease-specific metrics [15]. For vascular interventions, DSA offers precise anatomical visualization, while the mRS captures functional outcomes relevant to patients' daily lives [14]. In closed-loop systems, LFPs serve as critical biomarkers enabling real-time adaptation of therapeutic parameters [13].

The imperative for rigorous safety and efficacy evaluation in neurotechnology stems from both the profound potential benefits and significant risks associated with interfacing directly with the human nervous system. As the field expands rapidly—with dozens of technologies in development across mental health, healthy aging, and physical disability—robust evaluation frameworks must evolve in parallel [11]. The comparative data presented in this analysis demonstrate that methodological rigor, including controlled trial designs, standardized outcome measures, long-term safety monitoring, and comprehensive ethical oversight, is essential for responsible innovation [15] [14] [13]. Future development must bridge the identified gap between regulatory compliance and meaningful ethical reflection, particularly as technologies advance toward more sophisticated closed-loop systems and brain-computer interfaces [12] [13]. Only through such comprehensive evaluation can we ensure that neurotechnologies deliver on their promise to transform treatment for neurological and psychiatric disorders while safeguarding the fundamental aspects of human identity and autonomy.

The rapid advancement of neurotechnologies presents unprecedented opportunities for treating neurological disorders and restoring human function, while simultaneously creating complex regulatory challenges across international jurisdictions. Devices that interface directly with the central or peripheral nervous system can decode mental activity, with recent studies demonstrating astonishing capabilities—from decoding attempted speech in paralyzed patients with 97.5% accuracy to reconstructing visual imagery directly from brain scans [17]. These technological breakthroughs operate within a divergent global regulatory landscape, where the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Union Medical Device Regulation (MDR) represent two dominant but significantly different frameworks for ensuring safety and efficacy [18] [19]. Simultaneously, the emergence of "neuro-rights" as a legal concept reflects growing international concern about protecting mental privacy and neural data integrity [20] [17]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in neurotechnology, navigating these parallel pathways of device regulation and data protection requires careful strategic planning from the earliest stages of development through post-market surveillance.

Comparative Analysis: FDA vs. MDR Regulatory Frameworks

Fundamental Structural Differences

The FDA and EU MDR employ fundamentally different regulatory architectures, though both utilize risk-based classification systems. The FDA operates a centralized review process where the agency itself makes all approval decisions, while the MDR relies on a decentralized system where independent Notified Bodies conduct conformity assessments [21]. This structural difference creates varying timelines and consistency in review, as different Notified Bodies may interpret requirements slightly differently [21].

Philosophically, the frameworks also diverge in their core approaches. The FDA focuses primarily on whether a device is safe and effective for its intended use, often relying on substantial equivalence to existing predicates [21]. In contrast, the MDR takes a more performance-based approach, emphasizing clinical evaluation, post-market surveillance, and lifecycle safety even for moderate-risk devices [21].

Classification Systems Compared

Although both systems are risk-based, their classification structures differ significantly, leading to potential mismatches for specific neurotechnology devices:

Table 1: FDA vs. MDR Device Classification and Regulatory Pathways

| Aspect | US FDA | EU MDR |

|---|---|---|

| Risk Classes | Class I, II, III [18] | Class I, IIa, IIb, III [18] |

| Classification Basis | Intended use and product code [18] | 22 classification rules in Annex VIII [18] |

| Class I Devices | Most exempt from 510(k) but subject to General Controls [18] | Only standard Class I can be self-certified; sterile/measuring/reusable require Notified Body [18] |

| Class II/IIa Devices | Typically requires 510(k) demonstrating substantial equivalence [21] | Requires Notified Body assessment with clinical evidence [21] |

| Class III Devices | Premarket Approval (PMA) with clinical evidence [18] | Extensive clinical evaluation and Notified Body review [19] |

| Software Classification | Standalone software may be Class I [18] | Software typically Class IIa or higher [18] |

| Review Body | FDA directly reviews all submissions [19] | Notified Bodies conduct conformity assessments [19] |

Clinical Evidence Requirements

Clinical evidence requirements represent another significant divergence between the two frameworks. Under the MDR, clinical evaluation is an ongoing process throughout the device lifecycle, with particular emphasis on real-world clinical data and post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF) [19]. The FDA, in contrast, places greater emphasis on pre-market clinical trials, particularly for high-risk devices under the PMA pathway [19].

For neurotechnology devices specifically, the MDR typically requires Clinical Evaluation Reports (CER) for all Class III and some Class IIb devices, whereas the FDA does not require CER for most devices qualifying for 510(k) submission [19]. This discrepancy can significantly impact development timelines and resource allocation for neurotechnology companies planning regulatory strategy.

Emerging Neuro-Rights and Neural Data Protection Frameworks

The Expanding Definition of Neural Data

The regulatory landscape for neurotechnologies extends beyond device safety and efficacy to encompass emerging concerns about mental privacy and neural data protection. Neural data is uniquely sensitive because it can reveal intimate thoughts, memories, mental states, emotions, and health conditions—sometimes forecasting future behavior or health risks without conscious recognition by the individual [17]. The definition of neural data continues to evolve, generally encompassing information generated by measuring activity in both the central and peripheral nervous systems, whether obtained electrically, chemically, or via other means [17].

Internationally, prominent examples of neuro-rights legislation include Chile's pioneering 2021 constitutional amendment that protects "cerebral activity and the information drawn from it" as a constitutional right, which led to a 2023 Supreme Court ruling ordering a company to delete a consumer's neural data [17]. At the United Nations, a 2025 report by the Special Rapporteur on the right to privacy called for the development of a model law on neurotechnologies and neurodata processing to protect fundamental human rights [20].

United States Regulatory Landscape for Neural Data

The United States currently lacks comprehensive federal neural data protection legislation, but several important developments are shaping this emerging landscape:

Table 2: US Neural Data Privacy Legislation Overview

| Jurisdiction | Status | Key Provisions | Definition of Neural Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Federal (MIND Act) | Proposed (Oct 2025) [22] | Directs FTC to study neural data processing, identify regulatory gaps, and make recommendations [22] | Information obtained by measuring activity of central or peripheral nervous system [22] |

| Colorado | Enacted [23] | Includes neural data in "sensitive data" requiring opt-in consent for collection/processing [23] | Information generated by measuring nervous system activity that can be processed with device assistance [23] |

| California | Enacted [23] | Includes neural data in "sensitive personal information" with limited opt-out rights [23] | Excludes data inferred from non-neural information [23] |

| Other States | Proposed (CT, IL, MA, MN, MT, VT) [23] | Varying approaches from opt-in consent to processing restrictions [23] | Definitions vary, with some including and excluding peripheral data [22] |

The proposed federal Management of Individuals' Neural Data Act of 2025 (MIND Act) would direct the Federal Trade Commission to study the collection, use, storage, transfer, and other processing of neural data, which "can reveal thoughts, emotions, or decision-making patterns" [22]. The Act would not immediately create new regulations but would establish a framework for future oversight, recognizing both the risks and beneficial uses of neurotechnology in medical, scientific, and assistive applications [22].

Ethical Implementation and Compliance Strategies

For researchers and developers, compliance with emerging neuro-rights frameworks requires implementing robust data governance protocols that align with both existing regulations and anticipated legislation. Key considerations include:

- Data Minimization: Collect only neural data strictly necessary for the intended medical or research purpose [23]

- Informed Consent: Develop transparent consent processes that explain neural data collection, use, and storage in comprehensible language [20]

- Security Safeguards: Implement enhanced cybersecurity protections for neural data storage and transfer [22]

- Purpose Limitation: Use neural data only for the purpose for which it was originally collected [23]

A 2024 analysis of thirty direct-to-consumer neurotechnology companies revealed significant privacy practice gaps, with all companies taking possession of users' neural data, most retaining unfettered access rights, and many permitting broad sharing with third parties [17]. These findings highlight the urgent need for standardized ethical practices across the industry.

Safety and Efficacy Evaluation Methodologies for Neurotechnology

Multidimensional Assessment Framework

Evaluating the safety and efficacy of neurotechnologies requires multifaceted considerations at cellular, circuit, and system levels, including neuroinflammation, cell-type specificity, neural circuitry adaptation, systemic functional effects, electrode material safety, and electrical field distribution [24]. Given the complexity of the nervous system, comprehensive assessment requires innovative methodologies across the preclinical-to-clinical continuum.

Table 3: Neurotechnology Safety and Efficacy Assessment Methods

| Method Type | Key Applications | Typical Metrics | Considerations for Neurotechnology |

|---|---|---|---|

| In silico Modeling | Electrical field prediction, parameter optimization [24] | Field distribution, current density, thermal effects | Limited by biological complexity; requires validation |

| In vitro Systems | Electrode material degradation, cytotoxicity [24] | Cell viability, material integrity, inflammatory markers | May not recapitulate neural tissue complexity |

| In vivo Animal Models | Tissue response, functional outcomes, behavioral effects [24] | Histopathology, neural signals, behavioral tasks | Species differences may limit translatability |

| Clinical Trials | Human safety and efficacy [25] | Adverse events, performance metrics, patient-reported outcomes | Limited parameter exploration; focused on benefit-risk |

Recent advances in electrical stimulation safety assessment have revealed the importance of considering bidirectional interactions—how neural tissue changes impact stimulation effectiveness, how electrical parameters affect electrode integrity, and how electrode degradation alters electrical field distribution [24]. These complex interactions necessitate sophisticated testing protocols that extend beyond traditional characterization methods.

Representative Experimental Protocol: Flow Diverter Evaluation

A May 2025 prospective multicenter observational study of a mechanical balloon-based flow diverter for intracranial aneurysms demonstrates a comprehensive approach to neurotechnology evaluation [25]. The study enrolled 128 patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysms between September 2019 and November 2021, employing the following methodology:

Primary Efficacy Endpoints:

- Immediate implantation success rate

- Successful aneurysm occlusion rate (Raymond I-II or OKM C-D) at 12-month follow-up

- Complete occlusion rate (Raymond I or OKM D) at 12-month follow-up

- Parent artery stenosis rate (>50%) at follow-up

Primary Safety Endpoints:

- All-cause mortality

- Adverse events (AEs) and neurological AEs

- Serious adverse events (SAEs)

- Incidence of cerebral hemorrhage

The study reported a 100% deployment success rate, with 91.4% of patients achieving successful occlusion and 85.9% achieving complete occlusion at 12 months, while safety outcomes included no mortalities or cerebral hemorrhage, with 4.69% neurological adverse events and 3.1% serious adverse events [25]. This comprehensive endpoint structure exemplifies the dual focus on both technical performance and patient safety required for neurotechnology evaluation.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Neurotechnology safety and efficacy research requires specialized reagents and materials for comprehensive evaluation:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Neurotechnology Evaluation

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function in Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Neuronal Cultures | In vitro safety testing [24] | Assess cytotoxicity and neuronal response to stimulation |

| Multi-electrode Arrays | In vitro and in vivo electrophysiology [24] | Record neural activity and network responses |

| Immunohistochemistry Kits | Tissue analysis [24] | Evaluate neuroinflammation and tissue damage markers |

| Electrode Materials | Device development [24] | Test biocompatibility and electrical properties |

| Conducting Polymers | Electrode coating [24] | Improve interface properties and reduce impedance |

| fMRI Contrast Agents | Large animal and human studies [17] | Visualize neural activity and connectivity changes |

| EEG/ERP Systems | Non-invasive assessment [17] | Measure brain activity patterns and responses |

| Biomechanical Testers | Material durability [24] | Evaluate device integrity under physiological conditions |

| Cytokine Assays | Inflammation monitoring [24] | Quantify neuroinflammatory responses to implantation |

| AI-Decoding Algorithms | Neural signal interpretation [17] | Translate neural data to intended outputs or commands |

Integrated Regulatory Strategy for Global Neurotechnology Development

For neurotechnology developers targeting global markets, an integrated regulatory strategy that addresses both device approval and data protection requirements is essential. Key strategic considerations include:

- Early Classification Analysis: Conduct parallel FDA and MDR classification assessments during initial design phases, paying particular attention to software components and invasive/non-invasive distinctions [18] [19]

- Clinical Evidence Planning: Develop clinical evaluation strategies that satisfy both FDA pre-market trial requirements and MDR's ongoing post-market clinical follow-up expectations [19]

- Neural Data Protections: Implement privacy-by-design principles that comply with both existing frameworks (like Colorado and California laws) and anticipated federal guidance [23]

- Quality Management Integration: Transition to Quality Management System Regulation (QMSR) aligning with ISO 13485:2016 to streamline compliance with both FDA and MDR requirements [26]

- Post-Market Surveillance: Establish robust systems that address both EU requirements for Periodic Safety Update Reports (PSUR) and FDA adverse event reporting [18]

The regulatory pathway selection should consider not only time-to-market but also long-term compliance requirements. While FDA approval may offer faster entry for some moderate-risk devices through 510(k) pathways, the comprehensive clinical evidence required under MDR, though more resource-intensive initially, may provide competitive advantages in global markets [21].

Navigating the complex interplay between FDA device regulations, MDR requirements, and emerging neuro-rights frameworks presents significant challenges for neurotechnology researchers and developers. The divergent classification systems, clinical evidence expectations, and review processes between major markets necessitate early strategic planning and ongoing compliance vigilance. Simultaneously, the rapidly evolving landscape of neural data protection requires proactive implementation of ethical data practices that respect mental privacy while enabling beneficial medical applications. By adopting integrated development approaches that address safety, efficacy, and data protection in parallel—rather than sequentially—neurotechnology innovators can position themselves for sustainable success across global markets while maintaining public trust in these transformative technologies.

The rapid advancement of neurotechnology presents a dual frontier of therapeutic promise and significant safety challenges. As implantable devices such as deep brain stimulation (DBS) systems and closed-loop neurotechnologies become increasingly sophisticated, a comprehensive understanding of their risk profiles becomes essential for researchers, clinicians, and developers. The integration of artificial intelligence and adaptive algorithms in these systems introduces novel safety considerations that extend beyond traditional surgical risks to encompass psychological, identity, and data privacy dimensions [27] [28]. This analysis systematically compares safety risks across multiple neurotechnologies, providing structured experimental data and methodologies to inform safety efficacy evaluation in neurotechnology research.

Comparative Safety Risk Profiles of Major Neurotechnologies

Table 1: Quantitative Safety Data for Implantable Neurotechnologies

| Device Type | Most Common Surgical Complications | Most Common Device-Related Issues | Reported Psychological Effects | Frequency of Serious Adverse Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) | Infections (1-8%), lead misplacement [29] | High impedance, battery problems, unintended stimulation changes [29] | Worsening anxiety/depression, manic symptoms (in rare cases) [29] | 27% of high-risk devices recalled; serious psychological events in subset of patients [29] |

| Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) | Surgical complications, infection [29] | High impedance, incorrect frequency delivery, battery issues [29] | Voice alteration, laryngeal adverse effects (187 reports out of 12,725 issues) [29] | 449 death reports among 5,888 complications (2011-2021); causality not always established [29] |

| Spinal Cord/Dorsal Root Ganglion Stimulation | Lead migration, pocket pain, muscle spasms [29] | Device-related complications (almost 50% of reports) [29] | Not prominently reported | Surgical revision required in majority of complications; serious events like epidural hematomas (<0.2%) [29] |

| Responsive Neurostimulation (RNS) | Surgical site infections, implantation complications [28] | System removal required in some cases [28] | Not systematically assessed in most studies | 8 of 66 reviewed studies reported system removal [28] |

Table 2: Psychological and Identity-Related Safety Concerns

| Psychological Risk Domain | Reported Prevalence | Contextual Factors | Assessment Methodologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personality Changes | Limited evidence for widespread negative changes; some reports of positive restorative effects [30] | Often related to adjustment to symptom relief rather than direct device effects [30] | Qualitative interviews, standardized personality inventories [30] |

| Impact on Identity/Authenticity | Majority report unchanged or restored pre-disorder identity; rare cases of alienation [30] | Mediated by thorough pre-surgical evaluation and post-operative care [30] | Prospective studies with pre/post assessment; feelings of autonomy and control measures [30] |

| Autonomy & Agency Concerns | Increased feelings of control and self-regulation reported in many patients post-DBS [30] | Related to regaining functional capabilities rather than loss of agency [30] | Neuroethics scales, patient-reported outcomes, authenticity measures [30] |

Experimental Protocols for Safety Assessment

MAUDE Database Analysis Methodology

The FDA's Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database provides critical post-market surveillance data for neurotechnology safety assessment. A standardized protocol for analyzing this data involves:

Data Extraction: Collect all reports for specific device codes over defined time periods (typically 5-10 years for sufficient power) [29].

Categorization Framework: Classify adverse events into:

- Device malfunctions (hardware/software failures)

- Procedural complications (surgical and implantation-related)

- Clinical adverse events (psychological, neurological, systemic)

- Patient complaints (subjective experiences) [29]

Causality Assessment: Differentiate between device-related events and those with unclear relationship to the device.

Statistical Analysis: Calculate frequencies, proportions, and trends over time while acknowledging limitations of voluntary reporting systems.

This methodology was applied in a VNS analysis spanning 2011-2021 that identified 5,888 complications, enabling quantification of laryngeal adverse effects as the eighth most common vagus nerve problem [29].

Long-Term Safety Monitoring Protocol

The BrainGate clinical trial exemplifies rigorous long-term safety assessment for implanted brain-computer interfaces:

Duration: Implants maintained for extended periods (average over 2 years in BrainGate) to identify delayed complications [29].

Safety Endpoints: Monitor for:

- Device explantation requirements

- Death or permanently increased disability

- Infection rates (particularly intracranial)

- Unanticipated adverse device events [29]

Systematic Documentation: Use standardized reporting forms for all adverse events regardless of perceived relationship to device.

Independent Adjudication: Utilize data safety monitoring boards to evaluate event causality.

This protocol established the safety of the BrainGate system with no explantation-requiring events, no intracranial infections, and no device-related deaths or permanent disabilities among 14 participants over a 17-year period [29].

Sandbox Testing for Predictive Safety Validation

Researchers have proposed "sandbox" environments for predictive safety testing of neurotechnologies before human implantation:

Figure 1: Sandbox testing workflow for neurotechnology safety validation.

The experimental workflow involves:

Model Development: Create computational simulations of neural circuitry and tissue-electrode interfaces based on biophysical principles [27].

Device Integration: Interface actual device hardware or software with simulated biological environments.

Scenario Testing: Expose the device to simulated edge cases, rare neural states, and failure modes that would be unethical or impractical to test in humans [27].

Iterative Refinement: Use results to modify device parameters and algorithms to minimize identified risks.

This approach enables identification of latent failure modes and optimization of safety measures while reducing dependency on animal and early human trials [27].

Research Reagent Solutions for Neurotechnology Safety Research

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Safety Assessment

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Application in Safety Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Adverse Event Databases | FDA MAUDE database, Medical Device Recalls database [29] | Post-market surveillance; identification of rare complications; trend analysis across device types and time periods |

| Standardized Assessment Scales | QOLIE-31, QOLIE-89 (Quality of Life in Epilepsy), neuroethics scales [28] [13] | Quantifying impact on quality of life; standardizing psychological and identity-related outcome measures across studies |

| Computational Modeling Platforms | Virtual patient avatars, in silico neural networks, digital twins [27] | Simulating device-tissue interactions; predicting long-term effects; testing safety parameters in simulated environments |

| Clinical Trial Safety Endpoints | Procedure-related complications, system removal rates, serious adverse event frequency [28] [29] | Standardized safety monitoring in clinical studies; comparison across device platforms and patient populations |

Emerging Safety Paradigms and Research Gaps

The evolution of closed-loop neurotechnologies introduces unique safety challenges that conventional frameworks inadequately address. Current clinical studies demonstrate significant gaps in systematic ethical and safety assessment, with only 1 of 66 reviewed studies including dedicated ethical evaluation [28] [13]. Most ethical considerations remain implicit in technical discussions rather than receiving structured analysis.

The emerging "sandbox" approach represents a paradigm shift toward proactive safety engineering for neurotechnologies. By creating isolated testing environments where devices can be rigorously evaluated against simulated biological variability and edge cases, developers can identify and mitigate risks before human trials [27]. This methodology is particularly valuable for adaptive systems incorporating machine learning, whose behavior may evolve in unpredictable ways post-deployment.

Future safety research must address critical gaps including:

- Long-term effects of continuous neural monitoring and stimulation

- Standardized assessment of identity and agency impacts

- Cybersecurity vulnerabilities in connected neurodevices

- Equity in safety profiles across diverse patient populations [28] [12]

Comprehensive safety efficacy evaluation requires integration of quantitative device performance data, systematic psychological assessment, and robust post-market surveillance to balance therapeutic innovation with responsible development.

The direct-to-consumer (DTC) neurotechnology market represents a rapidly expanding sector at the intersection of neuroscience, consumer electronics, and digital health. These products, which interface with the nervous system to monitor, stimulate, or modulate neural activity, are increasingly marketed directly to consumers without requiring physician intermediaries [31] [32]. The global neurotechnology market is projected to reach significant value, with some estimates exceeding $50 billion by 2034, fueled by advances in neuroscience, materials science, and artificial intelligence [33] [32]. This growth reflects increasing consumer interest in technologies that promise cognitive enhancement, mental wellness monitoring, and alternative therapeutic interventions.

Unlike medically approved neurotechnologies that undergo rigorous clinical validation and regulatory scrutiny, most DTC products occupy a regulatory gray zone [34]. Manufacturers often market these devices as "wellness" products rather than medical devices, thereby bypassing the stringent premarket approval processes required for medical claims [31] [34]. This regulatory positioning creates significant challenges for evaluating product efficacy and safety, leaving consumers with limited protection against unsubstantiated claims and potential harms [34] [32]. The situation parallels historical challenges with dietary supplements, where limited premarket oversight has resulted in markets flooded with products of dubious effectiveness [31].

Efficacy Assessment: Methodological Frameworks and Comparative Performance

Evaluating DTC neurotechnology efficacy requires understanding both the scientific foundations of these technologies and the methodological limitations of consumer-grade implementations. The translation from laboratory research to consumer products often involves significant compromises in design, application, and validation that undermine efficacy claims.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Major DTC Neurotechnology Categories

Table 1: Efficacy Evidence and Limitations Across DTC Neurotechnology Categories

| Product Category | Stated Claims & Applications | Evidence Base | Key Efficacy Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer EEG Devices (e.g., NeuroSky) | Mental state monitoring (focus, stress, meditation) [31] | Laboratory EEG research; limited independent validation of consumer devices [31] | Different electrode configurations and placement by users vs. research-grade systems; classification algorithms often proprietary and unvalidated; potential for erroneous feedback causing psychological harm [31] |

| Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) | Cognitive enhancement, mood improvement [31] | Mixed results in controlled studies; debate about cognitive effects [35] | Questionable applicability of laboratory findings to consumer devices; variability in electrode placement; small effect sizes in meta-analyses; skin burns reported [31] |

| Cognitive Training Applications (e.g., Lumosity) | Improved memory, attention, generalizable cognitive benefits [31] | Some task-specific improvements; limited transfer to untrained cognitive domains [31] | Narrow training effects that often fail to generalize to real-world cognitive tasks; questionable practical significance of statistically significant improvements [31] |

| Mental Health Apps (e.g., meditation, mood tracking) | Stress reduction, mental health management [31] | Variable study quality; potential placebo effects [31] | Lack of professional support structures; uncertain efficacy compared to standard care; privacy concerns with sensitive data [31] [34] |

Experimental Protocols for Efficacy Evaluation

Rigorous assessment of DTC neurotechnology efficacy requires standardized methodologies that can validate manufacturer claims and identify potential limitations. The following experimental frameworks represent best practices for evaluating these technologies.

Protocol for Neurofeedback and EEG Device Validation

Objective: To evaluate the classification accuracy and signal reliability of consumer EEG devices in detecting claimed mental states (e.g., focus, stress, meditation) compared to research-grade systems [31].

Methodology:

- Participant Recruitment: N=40 healthy adults (balanced gender, 18-65 years)

- Equipment Setup: Simultaneous recording with consumer device (test unit) and research-grade EEG system (reference standard)

- Task Protocol:

- Resting State Baseline: 5 minutes eyes open, 5 minutes eyes closed

- Focused Attention: 20-minute continuous performance task with varying difficulty levels

- Stress Induction: 15-minute timed arithmetic task with social evaluation component

- Meditation: 15-minute guided mindfulness practice

- Data Analysis:

- Correlation of band power (alpha, beta, theta, gamma) between systems across conditions

- Comparison of mental state classification accuracy using manufacturer algorithms vs. research-grade feature extraction

- Test-retest reliability assessment across two sessions separated by 7 days

Validation Metrics: Inter-device correlation coefficients (>0.8 target), classification accuracy (>80% target), within-subject consistency (intraclass correlation coefficient >0.7) [31].

Protocol for Neurostimulation Cognitive Effects

Objective: To assess the impact of consumer tDCS devices on cognitive performance in domains matching marketing claims (e.g., working memory, attention) [31] [35].

Methodology:

- Study Design: Randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled trial with crossover design

- Participants: N=60 healthy adults (stratified by age and baseline cognitive performance)

- Intervention:

- Active Stimulation: Manufacturer-recommended parameters (e.g., 2mA for 20 minutes, electrode placement Fp3/Fp4)

- Sham Stimulation: Identical setup with 30-second ramp-up/down and no sustained stimulation

- Outcome Measures (assessed pre-, immediately post-, and 24 hours post-stimulation):

- Working Memory: N-back task (2-back, 3-back)

- Attention: Continuous performance task (reaction time, variability, commission errors)

- Executive Function: Task-switching paradigm (mixing costs, switch costs)

- Safety Monitoring: Skin assessment, adverse effect questionnaire, dropout rates

Statistical Analysis: Mixed-effects models accounting for period, sequence, and treatment effects; minimal clinically important difference thresholds established a priori [35].

Regulatory Landscape: Current Frameworks and Identified Gaps

The regulatory environment for DTC neurotechnologies remains fragmented, with significant variations in oversight approaches across jurisdictions and product categories. This regulatory patchwork creates challenges for consistent consumer protection and reliable product evaluation.

Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Approaches

Table 2: Regulatory Frameworks and Limitations for DTC Neurotechnologies

| Regulatory Mechanism | Scope & Authority | Key Strengths | Identified Insufficiencies |

|---|---|---|---|

| FDA Medical Device Regulation | Products making medical claims (disease treatment/diagnosis) [31] | Rigorous premarket review for safety and effectiveness; established classification system (I, II, III) based on risk [31] | "Wellness" products can bypass regulation by limiting claims; 2019 guidance clarified non-enforcement for low-risk wellness products [31] [34] |

| Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Oversight | Deceptive advertising practices [31] | Can take action against false marketing claims; has pursued cases against brain training companies [31] | Reactive rather than proactive approach; requires demonstrated deception; limited resources to monitor thousands of products [31] [34] |

| EU Medical Device Regulation (MDR) | Medical devices and certain non-medical devices per Annex XVI [32] | Broader scope than FDA in some areas; includes some non-medical brain stimulation equipment [32] | Still evolving implementation; distinction between medical and wellness uses creates potential gaps [32] |

| Self-Regulation & Working Groups | Industry standards and independent evaluations [31] | Flexibility to adapt to rapidly changing technologies; can provide consumer education [31] | Limited enforcement power; potential conflicts of interest; variable adoption [31] |

Regulatory Pathways and Decision Framework

The following diagram illustrates the complex regulatory pathways and decision points that determine the oversight level for neurotechnologies, highlighting where regulatory gaps emerge:

Regulatory Pathway Decision Flow

This diagram illustrates how most DTC neurotechnologies bypass rigorous FDA oversight by making only wellness claims, falling into a regulatory gap with primarily reactive FTC protection against deceptive marketing [31] [34].

Research Toolkit: Essential Methodologies and Reagents

Comprehensive evaluation of DTC neurotechnologies requires specialized research tools and methodologies to assess both their technical performance and biological effects.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for DTC Neurotechnology Evaluation

| Research Tool Category | Specific Examples & Applications | Function in Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard Recording Systems | Research-grade EEG (e.g., 256-channel systems), fMRI, MEG [31] [12] | Provide gold-standard measurement of neural activity for validating consumer device signal accuracy [31] |

| Behavioral Task Platforms | Cognitive test batteries (CANTAB, NIH Toolbox), specialized paradigms (N-back, flanker, Stroop) [31] | Objective assessment of cognitive claims (memory, attention) under controlled conditions [31] |

| Biomarker Assays | Plasma pTau-181, pTau-217, GFAP, neurofilament light chain (NfL) [36] | Assessment of potential neurobiological effects in clinical populations; used in recent Alzheimer's device trials [36] |

| Signal Processing Tools | Open-source algorithms (EEGLAB, FieldTrip), custom classification pipelines [31] | Independent analysis of neural data quality and feature extraction validity [31] |

| Safety Assessment Materials | Skin impedance measurement tools, adverse effect structured interviews, thermal cameras [31] [35] | Objective evaluation of physical safety parameters and side effect profiles [31] |

| (R)-2-Phenylpropylamide | (R)-2-Phenylpropylamide | High-Purity Chiral Reagent | High-purity (R)-2-Phenylpropylamide for research. A key chiral building block for asymmetric synthesis & medicinal chemistry. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Benzamide, N,N,4-trimethyl- | Benzamide, N,N,4-trimethyl-, CAS:14062-78-3, MF:C10H13NO, MW:163.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive Device Evaluation

The following diagram outlines a systematic approach for evaluating DTC neurotechnologies, incorporating both technical validation and assessment of functional claims:

Comprehensive Device Evaluation Workflow

This workflow emphasizes the multi-phase approach necessary to thoroughly evaluate DTC neurotechnologies, from technical validation through functional assessment and safety profiling [31] [35] [36].

The DTC neurotechnology market presents significant challenges regarding efficacy validation and regulatory oversight. Current evidence suggests substantial gaps between marketing claims and scientifically demonstrated effects across multiple product categories [31]. These efficacy concerns are exacerbated by a regulatory framework that permits many products to reach consumers without rigorous premarket evaluation [31] [34].

Addressing these challenges requires a multi-faceted approach including enhanced regulatory clarity, independent evaluation mechanisms, and standardized methodological frameworks for device assessment [31] [32]. The development of an independent working group to evaluate DTC neurotechnologies—similar to models proposed in the literature—could provide much-needed objective assessment while balancing innovation promotion and consumer protection [31]. Furthermore, increased funding for research specifically examining the safety and efficacy of consumer neurotechnologies would help address current evidence gaps and inform both regulatory policy and consumer decision-making [31].

As the neurotechnology landscape continues to evolve at a rapid pace, establishing robust, scientifically-grounded evaluation frameworks becomes increasingly urgent to ensure that consumer products deliver meaningful benefits while minimizing potential harms.

Advanced Methodologies for Testing and Clinical Translation

The evaluation of safety and efficacy represents a critical foundation in the development of neurotechnologies and therapeutic agents. Traditional preclinical approaches have historically relied on a sequential pipeline progressing from in vitro (in glass) studies to in vivo (in living organism) animal testing. However, the landscape of biomedical research is undergoing a profound transformation driven by technological innovation. The emergence of sophisticated in silico (computational) modeling and advanced, human-relevant in vitro systems is rewriting the rules of preclinical research [37]. These innovative models offer unprecedented opportunities to understand complex biological mechanisms, enhance predictive accuracy, and adhere to ethical principles, thereby accelerating the translation of novel neurotechnologies from bench to bedside. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these three pillars—in silico, in vitro, and in vivo—within the context of neurotechnology safety and efficacy evaluation, supporting a broader thesis that integrated, human-relevant approaches are essential for future progress.

Model Definitions and Core Characteristics

The modern preclinical toolkit encompasses three distinct but complementary methodologies. In silico models use computer simulations to model biological systems, from molecular drug-target interactions to whole-organ physiology [38] [37]. In vitro models involve studying biological components, such as cells or tissues, in a controlled laboratory environment outside their native context [39]. In vivo models involve studying biological processes within a living organism, typically an animal model, to assess integrated system-level responses [40] [39].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Preclinical Models

| Feature | In Silico Models | In Vitro Models | In Vivo Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Computer-based simulations of biological processes [38] [37] | Cells or tissues studied in an artificial, non-living environment [39] | Studies conducted within a living organism [40] |

| Typical Applications | Target-drug dynamics, disease progression modeling, toxicity prediction, pharmacokinetics [38] [37] | Drug screening, molecular pathway analysis, basic cell behavior, co-culture studies [40] [41] | System-level efficacy, toxicity, pharmacokinetics, behavioral studies, complex disease phenotypes [40] |

| Fundamental Principle | Computational abstraction and simulation of biology | Isolation and control of biological variables | Preservation of full biological complexity |

| Key Strength | High-throughput, mechanistic insight, can simulate unobservable processes [38] | High control over variables, amenable to human-derived cells, often high-throughput [39] | Provides full physiological context; historical gold standard for system-level prediction [40] [39] |

| Inherent Limitation | Dependent on quality of input data and model assumptions; can be a "black box" [38] [37] | Simplified environment; lacks systemic interactions [41] [39] | Species differences; ethical concerns; high cost and low throughput [40] [37] [39] |

Comparative Analysis in Neurotechnology and Drug Development

Each model class offers a unique set of advantages and limitations, making them suited for different stages of the research and development pipeline.

In Silico Approaches

In silico modeling has shifted from a complementary tool to a critical component in early-stage development pipelines [38]. In neurotechnology, these models are used to simulate the safety and efficacy of electrical stimulation devices by modeling neuronal and non-neuronal responses at cellular, circuit, and system levels [24]. For drug development, target-drug dynamic simulations use molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and AI-augmented models to predict how a therapeutic agent interacts with its biological target [38].

Key Advantages:

- Mechanistic Insight: Techniques like molecular dynamics simulations can reveal interaction patterns (e.g., hydrogen bonds, binding site flexibility) that static experiments cannot capture, allowing for early refinement of drug leads [38].

- Speed and Cost-Efficiency: Virtual screening of large compound libraries can drastically reduce the number of molecules that require synthesis and wet-lab testing, accelerating lead prioritization [38].

- Predictive ADMET: AI models are increasingly effective at predicting a compound's absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profiles, helping to weed out problematic candidates early [38].

- Scalability and Ethics: Computational models can evaluate millions of compounds and reduce reliance on animal testing, aligning with the 3R (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) principles [38] [37].

Key Limitations:

- Model Accuracy: Predictions are highly dependent on the quality of input data. Many targets lack high-resolution structures, and using homology models can lead to inaccurate results [38].

- Computational Cost: While molecular docking is relatively cheap, accurate molecular dynamics or free energy calculations require substantial computational resources [38].

- Data Bias: AI/machine learning models can be biased if trained on limited or non-representative datasets, particularly for under-studied targets, leading to over-optimistic predictions [38].

- Regulatory Hurdles: Regulatory agencies often require reproducible experimental data, and the acceptance of in silico data as primary evidence is still evolving, though this is changing rapidly [38] [37].

In Vitro Approaches

In vitro models range from simple two-dimensional (2D) monolayer cell cultures to advanced three-dimensional (3D) systems like spheroids, organoids, and organ-on-a-chip devices [40] [41] [39]. In neurotechnology, these models are crucial for testing the biocompatibility of implant materials and understanding cellular responses to electrical stimulation [24] [41].

Key Advantages:

- High Control and Throughput: Researchers maintain precise control over the cellular environment (nutrients, temperature, etc.), making these systems ideal for high-throughput drug screening and mechanistic studies [40] [39].

- Use of Human Cells: Advanced models like Organ-Chips can be constructed with human cells, circumventing the issue of species translatability that plagues animal models [39].

- Bridging the Gap: Advanced 3D in vitro models, such as organoids and Organ-Chips, expose cells to biomechanical forces, fluid flow, and heterogeneous cell populations, encouraging more in vivo-like behavior and improving translational value [41] [39].

Key Limitations:

- Simplified Environment: Even advanced 3D models cannot fully recapitulate the systemic complexity of a living organism, including integrated immune, endocrine, and neural networks [40] [41].

- Artificial Mutations: Immortalized cell lines, commonly used in 2D culture, may develop mutations that cause them to behave abnormally, reducing their predictive power [39].

In Vivo Approaches

In vivo models, typically in animals, remain the gold standard for assessing complex outcomes like behavior, systemic toxicity, and therapeutic efficacy in an intact organism [40] [39]. They are essential for studying phenomena such as neuroinflammation, circuit-level neural adaptation, and systemic functional effects of neuromodulation [24].

Key Advantages:

- Full Physiological Context: Provides the most accurate representation of how cells and tissues function within a complete, living system, accounting for metabolism, immune responses, and organ-organ interactions [39].

- Complex Phenotypes: Ideal for studying complex disease processes, such as tumor heterogeneity and metastasis, which are difficult to model in vitro [40].

Key Limitations:

- Species Differences: Genetic and physiological differences between animals and humans can erode the predictive accuracy of these models, particularly in preclinical drug safety testing [37] [39].

- Ethical and Regulatory Concerns: The use of animals in research is fraught with ethical considerations and is subject to increasingly stringent regulatory requirements [40] [37].

- High Cost and Low Throughput: Animal studies are expensive, labor-intensive, and low-throughput, making them unsuitable for large-scale screening [40].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Model Performance and Utility

| Criterion | In Silico Models | Simple 2D In Vitro | Advanced 3D In Vitro | In Vivo Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Cost | Low (after development) | Low [39] | Moderate [41] | Very High [40] [37] |

| Throughput | Very High (can screen millions) [38] | High [39] | Moderate [41] | Low |

| Human Relevance | Variable (depends on data and model) | Low to Moderate [39] | High (if using human cells) [41] [39] | Low to Moderate (due to species differences) [39] |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Growing (e.g., FDA Modernization Act 2.0) [37] | Established for specific endpoints | Emerging | Established gold standard [40] |

| Data Output | Predictive simulations & KPIs | Cellular viability, toxicity, pathway data | Complex cell-cell interactions, tissue-level responses | Systemic efficacy, toxicity, behavioral data [40] |

| Example Neurotech Application | Simulating electrical field distribution & neural activation [24] | Testing electrode material cytotoxicity on neuronal cell lines [24] [41] | 3D co-culture of neurons/glia to model implant-associated infection [41] | Evaluating seizure reduction or motor function recovery post-stimulation |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for In Silico Target-Drug Dynamics

This protocol outlines the steps for simulating drug binding to a biological target, a key application in central nervous system (CNS) drug discovery [38].

- Target Preparation: Obtain a high-resolution 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., a neuronal receptor) from a protein data bank. If an experimental structure is unavailable, create a homology model using a related template, and verify the model against known ligands [38].