Evaluating Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA): A Performance Analysis on CEC Benchmark Problems

This article provides a comprehensive performance evaluation of the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) using the standard CEC benchmark suites.

Evaluating Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA): A Performance Analysis on CEC Benchmark Problems

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive performance evaluation of the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) using the standard CEC benchmark suites. Aimed at researchers and professionals in computational intelligence and drug development, the analysis covers NPDOA's foundational principles, methodological application for complex problem-solving, strategies for troubleshooting and optimization, and a rigorous comparative validation against state-of-the-art metaheuristic algorithms. The findings offer critical insights into the algorithm's convergence behavior, robustness, and practical applicability for solving high-dimensional, real-world optimization challenges, such as those encountered in biomedical research.

Understanding NPDOA: Foundations in Neural Dynamics and Benchmarking Principles

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) is a novel brain-inspired meta-heuristic method that represents a significant shift in optimization algorithm design by drawing inspiration from computational neuroscience rather than traditional natural metaphors [1]. This algorithm conceptualizes the neural state of a population of neurons as a potential solution to an optimization problem, where each decision variable corresponds to a neuron and its value represents the neuron's firing rate [1]. NPDOA simulates the activities of interconnected neural populations during cognitive and decision-making processes, implementing these biological processes through three core computational strategies that work in concert to balance global exploration and local exploitation throughout the optimization process [1].

The algorithm's foundation in brain neuroscience is particularly significant because the human brain demonstrates remarkable efficiency in processing diverse information types and arriving at optimal decisions across different situations [1]. By mimicking these neural processes, NPDOA aims to capture this efficiency in solving complex optimization problems that often challenge traditional meta-heuristic approaches, especially those involving nonlinear and nonconvex objective functions commonly encountered in practical engineering applications [1].

Core Mechanisms and Inspirational Basis

The Three Fundamental Strategies of NPDOA

NPDOA operates through three strategically designed mechanisms that mirror different aspects of neural population behavior, each serving a distinct purpose in the optimization process:

Attractor Trending Strategy: This component drives neural populations toward optimal decisions by promoting convergence toward stable neural states associated with favorable decisions, thereby ensuring the algorithm's exploitation capability [1]. In neuroscientific terms, this mimics how neural circuits converge to stable states representing perceptual decisions or memory recall.

Coupling Disturbance Strategy: This mechanism introduces controlled interference by coupling neural populations with others, deliberately deviating them from their current attractors to enhance exploration ability [1]. This prevents premature convergence by maintaining population diversity, analogous to how noise or cross-talk between neural populations can foster exploration of alternative solutions in biological neural systems.

Information Projection Strategy: This component regulates communication between neural populations, dynamically controlling the transition from exploration to exploitation phases by adjusting the impact of the previous two strategies on neural states [1]. This reflects how neuromodulatory systems in the brain globally influence neural dynamics based on behavioral context.

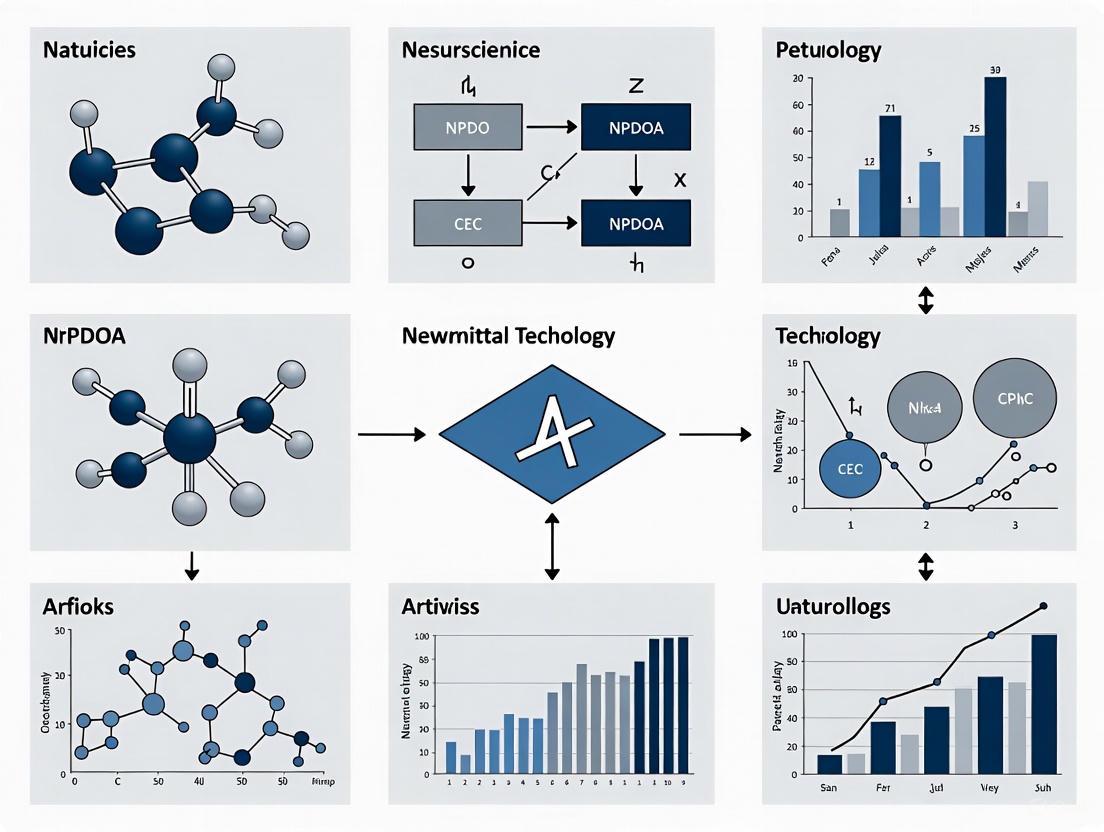

The relationship and workflow between these three core strategies can be visualized as follows:

Comparative Analysis of Algorithm Inspiration

The inspirational basis of NPDOA represents a significant departure from conventional meta-heuristic algorithms, placing it in a distinctive category within the optimization landscape:

Table: Comparison of Algorithmic Inspiration Sources

| Algorithm Category | Representative Algorithms | Source of Inspiration | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Neuroscience | Neural Population Dynamics Optimization (NPDOA) [1] | Human brain neural population activities | Three-strategy balance, decision-making simulation |

| Swarm Intelligence | PSO [1], ABC [1], WOA [1] | Collective animal behavior | Social cooperation, local/global best guidance |

| Evolutionary Algorithms | GA [1], DE [1], BBO [1] | Biological evolution | Selection, crossover, mutation operations |

| Physics-Inspired | SA [1], GSA [1], CSS [1] | Physical laws & phenomena | Simulated annealing, gravitational forces |

| Mathematics-Based | SCA [1], GBO [1], PSA [1] | Mathematical formulations & functions | Sine-cosine operations, gradient-based rules |

This comparative analysis reveals NPDOA's unique positioning within the meta-heuristic spectrum. While swarm intelligence algorithms mimic collective animal behavior and evolutionary algorithms simulate biological evolution, NPDOA draws from a fundamentally different source—the information processing and decision-making capabilities of the human brain [1]. This inspiration from computational neuroscience potentially offers a more direct mapping to optimization processes, as the brain itself is a powerful optimization engine that continuously adapts to complex environments.

Experimental Evaluation and Performance Analysis

Standardized Testing Methodology

To ensure objective and reproducible evaluation of optimization algorithms like NPDOA, researchers employ standardized testing methodologies centered around established benchmark problems. The Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC) benchmark suites represent the gold standard in this domain, providing carefully designed test functions that challenge different algorithmic capabilities [2] [3].

The typical experimental protocol for evaluating meta-heuristic algorithms involves:

Benchmark Selection: Utilizing standardized test suites such as CEC2017, CEC2020, or CEC2022 that include unimodal, multimodal, hybrid, and composition functions [2] [4] [3]. These functions test different algorithmic capabilities including exploitation, exploration, and adaptability to various landscape features.

Multiple Independent Runs: Conducting numerous independent runs (typically 30-31) with different random seeds to account for algorithmic stochasticity and ensure statistical significance of results [5] [2].

Performance Metrics: Employing standardized performance metrics including:

- Best Function Error Value (BFEV): Difference between the best objective value found and the known global optimum [6]

- Offline Error: Average of current error values over the entire optimization process [5]

- Convergence Speed: Number of function evaluations required to reach a solution of specified quality

Statistical Analysis: Applying rigorous statistical tests such as the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Friedman test to determine significant performance differences between algorithms [2] [3].

The following diagram illustrates this standardized experimental workflow:

Performance Comparison on Benchmark Problems

NPDOA's performance has been evaluated against various state-of-the-art meta-heuristic algorithms across standardized benchmark problems. The following table summarizes comparative results based on comprehensive experimental studies:

Table: NPDOA Performance Comparison on Benchmark Problems

| Algorithm | Algorithm Category | Key Strengths | Reported Limitations | Performance vs. NPDOA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPDOA [1] | Brain-inspired Swarm Intelligence | Balanced exploration-exploitation, effective decision-making simulation | Requires further testing on higher-dimensional problems | Reference |

| PSO [1] [7] | Swarm Intelligence | Simple implementation, effective local search | Premature convergence, parameter sensitivity | NPDOA shows better balance |

| DE [1] [7] | Evolutionary Algorithm | Robust performance, good exploration | Parameter tuning challenges, slower convergence | NPDOA demonstrates competitive performance |

| WOA [1] | Swarm Intelligence | Effective spiral search mechanism | Computational complexity in high dimensions | NPDOA reportedly more efficient |

| RTH [2] | Swarm Intelligence | Good for UAV path planning | Requires improvement strategies | IRTH variant shows competitiveness |

| HEO [4] | Swarm Intelligence | Effective escape from local optima | Newer algorithm requiring validation | Similar inspiration but different approach |

| CSBOA [3] | Swarm Intelligence | Enhanced with crossover strategies | Limited application scope | NPDOA offers different strategic balance |

The experimental results from benchmark problem evaluations indicate that NPDOA demonstrates distinct advantages when addressing many single-objective optimization problems [1]. The algorithm's brain-inspired architecture appears to provide a more natural balance between exploration and exploitation compared to some conventional approaches, contributing to its competitive performance across diverse problem landscapes.

Performance in Practical Engineering Applications

Beyond standard benchmarks, NPDOA has been validated on practical engineering optimization problems, demonstrating its applicability to real-world challenges:

Table: NPDOA Performance on Engineering Design Problems

| Engineering Problem | Problem Characteristics | NPDOA Performance | Comparative Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compression Spring Design [1] | Continuous/discrete variables, constraints | Effective constraint handling | GA, PSO, DE |

| Cantilever Beam Design [1] | Structural optimization, constraints | Competitive solution quality | Mathematical programming |

| Pressure Vessel Design [1] [4] | Mixed-integer, nonlinear constraints | Feasible solutions obtained | HEO, GWO, PSO |

| Welded Beam Design [1] [4] | Nonlinear constraints, continuous variables | Cost-effective solutions | Various meta-heuristics |

In these practical applications, NPDOA's ability to handle nonlinear and nonconvex objective functions with complex constraints demonstrates the practical utility of its brain-inspired optimization approach [1]. The algorithm's three-strategy framework appears particularly well-suited to navigating the complex search spaces characteristic of real-world engineering problems.

Essential Research Toolkit

Researchers working with NPDOA and comparative meta-heuristic algorithms typically utilize a standardized set of computational tools and resources:

Table: Essential Research Tools for Algorithm Development and Testing

| Research Tool | Primary Function | Application in NPDOA Research |

|---|---|---|

| PlatEMO [1] | Evolutionary multi-objective optimization platform | Experimental framework for NPDOA evaluation |

| CEC Benchmark Suites [2] [3] | Standardized test problems | Performance assessment on known functions |

| EDOLAB Platform [5] | Dynamic optimization environment | Testing dynamic problem capabilities |

| GMPB [5] | Generalized Moving Peaks Benchmark | Dynamic optimization problem generation |

| Statistical Test Suites | Wilcoxon, Friedman tests | Statistical validation of performance differences |

The introduction of Neural Population Dynamics Optimization represents a promising direction in meta-heuristic research by drawing inspiration from computational neuroscience rather than metaphorical natural phenomena. NPDOA's three-strategy framework—attractor trending, coupling disturbance, and information projection—provides a neurologically-plausible mechanism for balancing exploration and exploitation in complex optimization landscapes.

Experimental evidence from both benchmark problems and practical engineering applications indicates that NPDOA performs competitively against established meta-heuristic algorithms, particularly in single-objective optimization scenarios [1]. The algorithm's brain-inspired architecture appears to offer advantages in maintaining diversity while effectively converging to high-quality solutions.

Future research directions for NPDOA include expansion to multi-objective and dynamic optimization problems, hybridization with other algorithmic approaches, application to large-scale and high-dimensional problems, and further exploration of connections with computational neuroscience findings. As the meta-heuristic field continues to evolve, brain-inspired algorithms like NPDOA offer exciting opportunities for developing more efficient and biologically-grounded optimization techniques.

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) represents a groundbreaking shift in meta-heuristic optimization by drawing direct inspiration from human brain neuroscience. Unlike traditional nature-inspired algorithms that mimic animal swarming behavior or physical phenomena, NPDOA simulates the activities of interconnected neural populations in the brain during cognition and decision-making processes. This brain-inspired approach enables a sophisticated balance between exploration and exploitation—the two fundamental characteristics that determine any meta-heuristic algorithm's effectiveness. The algorithm treats each potential solution as a neural population where decision variables represent neurons and their values correspond to firing rates, creating a direct mapping between computational optimization and neural computation in the brain [1].

The development of NPDOA responds to significant challenges faced by existing meta-heuristic approaches. Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) often struggle with premature convergence and require extensive parameter tuning, while Swarm Intelligence algorithms frequently become trapped in local optima and demonstrate low convergence rates in complex landscapes. Physical-inspired and mathematics-inspired algorithms, though valuable, similarly face difficulties in maintaining proper balance between exploration and exploitation across diverse problem types [1]. By modeling the brain's remarkable ability to process complex information and make optimal decisions, NPDOA introduces a novel framework for solving challenging optimization problems, particularly those with nonlinear and nonconvex objective functions commonly encountered in engineering and scientific domains.

Core Mechanics: Three Brain-Inspired Strategies

NPODA implements three fundamental strategies derived from theoretical neuroscience principles, each serving a distinct purpose in the optimization process and working in concert to efficiently navigate complex fitness landscapes.

Attractor Trending Strategy

The attractor trending strategy drives neural populations toward optimal decisions by emulating the brain's ability to converge toward stable states associated with favorable outcomes. In neuroscience, attractor states represent preferred neural configurations that correspond to specific decisions or memories. Similarly, in NPDOA, this strategy facilitates exploitation capability by guiding solutions toward promising regions identified in the search space. The mechanism functions by creating a dynamic where neural populations gradually move toward attractor points that represent locally optimal solutions, thereby intensifying the search in areas with high-quality solutions. This process mirrors how the brain stabilizes neural activity patterns when making confident decisions, ensuring that the algorithm can thoroughly explore promising regions without premature diversion [1].

Coupling Disturbance Strategy

The coupling disturbance strategy introduces controlled disruptions by coupling neural populations with each other, effectively deviating them from their current attractors. This mechanism enhances the algorithm's exploration ability by preventing premature convergence to local optima. In neural terms, this mimics the brain's capacity for flexible thinking and consideration of alternative solutions by temporarily disrupting stable neural patterns. The coupling between different neural populations creates interference patterns that push solutions away from current trajectories, facilitating exploration of new regions in the search space. This strategic disturbance ensures population diversity throughout the optimization process, enabling the algorithm to escape local optima and discover potentially superior solutions in unexplored areas of the fitness landscape [1].

Information Projection Strategy

The information projection strategy regulates communication between neural populations, controlling the transition from exploration to exploitation. This component manages how information flows between different solutions, effectively adjusting the influence of the attractor trending and coupling disturbance strategies based on the algorithm's current state. The strategy implements a dynamic control mechanism that prioritizes exploration during early stages of optimization while gradually shifting toward exploitation as the search progresses. This adaptive information transfer mirrors the brain's efficient management of cognitive resources during complex problem-solving, where different brain regions communicate and coordinate to balance between focused attention and broad exploration [1].

Table 1: Core Strategies of NPDOA and Their Functions

| Strategy Name | Inspiration Source | Primary Function | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attractor Trending | Neural convergence to stable states | Exploitation | Drives populations toward optimal decisions |

| Coupling Disturbance | Neural interference patterns | Exploration | Deviates populations from current attractors |

| Information Projection | Inter-regional brain communication | Transition Control | Regulates communication between populations |

Experimental Methodology & Benchmarking

Experimental Protocol and Evaluation Framework

The evaluation of NPDOA follows rigorous experimental protocols established in computational optimization research. Comprehensive testing involves both benchmark problems and practical engineering applications to validate performance across diverse scenarios. The standard experimental setup employs multiple independent runs (typically 25-31 runs) with different random seeds to ensure statistical significance, following established practices in the field [5]. Performance evaluation utilizes the offline error metric, which calculates the average of current error values throughout the optimization process, providing a comprehensive view of algorithm performance across all environments or function evaluations [5].

For dynamic optimization problems—where the fitness landscape changes over time—algorithms are evaluated across multiple environmental changes (typically 100 environments) to assess adaptability and response speed. The computational budget is defined by the maximum number of function evaluations (maxFEs), which serves as the termination criterion. In specialized competitions like the IEEE CEC 2025 Competition on Dynamic Optimization Problems, parameters such as ChangeFrequency, Dimension, and ShiftSeverity are systematically varied across problem instances to create comprehensive test suites that evaluate algorithm performance under different conditions and difficulty levels [5].

Benchmark Problems and Performance Metrics

NPDOA's performance has been validated against established benchmark problems including compression spring design, cantilever beam design, pressure vessel design, and welded beam design problems—all representing challenging real-world engineering applications with nonlinear and nonconvex objective functions [1]. The benchmark problems encompass diverse characteristics ranging from unimodal to highly multimodal, symmetric to highly asymmetric, smooth to highly irregular, with various degrees of variable interaction and ill-conditioning [5].

The primary performance metric used in comparative studies is the offline error, calculated as ( E{o} = \frac{1}{T\vartheta}\sum{t=1}^{T}\sum_{c=1}^{\vartheta}(f^{\circ(t)}(\vec{x}^{(t)}) - f^{(t)}(\vec{x}^{((t-1)\vartheta+c)})) ), where ( \vec{x}^{\circ(t)} ) is the global optimum position at the t-th environment, T is the number of environments, 𝜗 is the change frequency, c is the fitness evaluation counter, and ( \vec{x}^{*((t-1)\vartheta+c)} ) is the best found position at the c-th fitness evaluation in the t-th environment [5]. This metric provides a comprehensive assessment of how closely and consistently an algorithm can track the moving optimum in dynamic environments.

Table 2: Benchmark Problem Characteristics for Algorithm Evaluation

| Problem Type | Key Characteristics | Performance Metrics | Evaluation Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Static Benchmarks | Nonlinear, nonconvex, constrained | Solution quality, convergence speed | Exploration-exploitation balance |

| Dynamic Benchmarks (GMPB) | Time-varying fitness landscape | Offline error, adaptability | Tracking capability, response speed |

| Engineering Problems | Real-world constraints, mixed variables | Feasibility, computational cost | Practical applicability |

Performance Comparison with State-of-the-Art Algorithms

Quantitative Performance Analysis

NPDOA has demonstrated competitive performance when evaluated against nine established meta-heuristic algorithms across diverse benchmark problems. The systematic experimental studies conducted using PlatEMO v4.1 revealed NPDOA's distinct advantages in addressing many single-objective optimization problems, particularly those with complex landscapes and challenging constraints [1]. The algorithm's brain-inspired architecture enables effective navigation of multi-modal search spaces while maintaining a superior balance between exploration and exploitation compared to traditional approaches.

In the broader context of evolutionary computation competitions, performance benchmarks from the IEEE CEC 2025 Competition on Dynamic Optimization Problems provide relevant performance insights. While NPDOA results are not specifically included in these competition reports, the winning algorithms such as GI-AMPPSO (+43 win-loss score), SPSOAPAD (+33 win-loss score), and AMPPSO-BC (+22 win-loss score) demonstrate the current state-of-the-art performance in dynamic environments [5]. These results establish the competitive landscape against which emerging algorithms like NPDOA must be evaluated, particularly for dynamic optimization problems generated by the Generalized Moving Peaks Benchmark (GMPB) with different characteristics and difficulty levels.

Comparative Analysis with Algorithm Categories

When compared to traditional algorithm categories, NPDOA addresses several limitations observed in established approaches:

Evolutionary Algorithms (GA, DE, BBO): While EAs are efficient general-purpose optimizers, they face challenges with problem representation using discrete chromosomes and often exhibit premature convergence. NPDOA's continuous neural state representation and dynamic balancing mechanisms help overcome these limitations, providing more robust performance across diverse problem types [1].

Swarm Intelligence Algorithms (PSO, ABC, FSS): Classical SI algorithms frequently become trapped in local optima and demonstrate low convergence rates in complex landscapes. While state-of-the-art variants like WOA, SSA, and WHO achieve higher performance, they often incorporate more randomization methods that increase computational complexity for high-dimensional problems. NPDOA's structured neural dynamics offer a more principled approach to maintaining diversity without excessive randomization [1].

Physical-inspired Algorithms (SA, GSA, CSS): These algorithms combine physics principles with optimization but lack crossover or competitive selection operations. They frequently suffer from trapping in local optima and premature convergence. NPDOA's brain-inspired mechanisms provide a more biological foundation for adaptive optimization behavior [1].

Mathematics-inspired Algorithms (SCA, GBO, PSA): These newer approaches offer valuable mathematical perspectives but often struggle with local optima and lack proper trade-off between exploitation and exploration. NPDOA's three-strategy framework explicitly addresses this balance through dedicated mechanisms [1].

Table 3: Performance Comparison Across Algorithm Categories

| Algorithm Category | Representative Algorithms | Key Strengths | Common Limitations | NPDOA Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Algorithms | GA, DE, BBO | Proven effectiveness, theoretical foundation | Premature convergence, parameter sensitivity | Adaptive balance, neural state representation |

| Swarm Intelligence | PSO, ABC, WOA | Intuitive principles, parallel search | Local optima trapping, low convergence | Structured exploration, cognitive inspiration |

| Physical-inspired | SA, GSA, CSS | Physics principles, no crossover needed | Premature convergence, local optima | Biological foundation, dynamic control |

| Mathematics-inspired | SCA, GBO, PSA | Mathematical rigor, new perspectives | Local optima, exploration-exploitation imbalance | Explicit balance through three strategies |

Computational Frameworks and Benchmarking Tools

Researchers working with NPDOA and comparable optimization algorithms require specialized tools for rigorous experimental evaluation and comparison. PlatEMO v4.1 represents an essential MATLAB-based platform for experimental computer science, providing comprehensive support for evaluating meta-heuristic algorithms across diverse benchmark problems [1]. This open-source platform enables standardized performance assessment and facilitates direct comparison between different optimization approaches under consistent experimental conditions.

For dynamic optimization problems, the Evolutionary Dynamic Optimization Laboratory (EDOLAB) offers a specialized MATLAB framework for education and experimentation in dynamic environments. The platform includes implementations of the Generalized Moving Peaks Benchmark (GMPB), which generates dynamic problem instances with controllable characteristics including modality, symmetry, smoothness, variable interaction, and conditioning [5]. The EDOLAB platform is publicly accessible through GitHub repositories, providing researchers with standardized testing environments for dynamic optimization algorithms.

Effective analysis of algorithm performance requires specialized tools for statistical comparison and result visualization. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test serves as the standard non-parametric statistical method for comparing algorithm performance across multiple independent runs, with win-loss-tie counts providing robust ranking criteria in competitive evaluations [5]. For visualization of high-dimensional optimization landscapes and algorithm behavior, color palettes designed for scientific data representation—such as perceptually uniform colormaps like "viridis," "magma," and "rocket"—enhance clarity and interpretability [8].

Accessibility evaluation tools including axe-core and Color Contrast Analyzers ensure that visualization components meet WCAG 2.1 contrast requirements, maintaining accessibility for researchers with visual impairments [9] [10]. These tools verify that color ratios meet minimum thresholds of 4.5:1 for normal text and 3:1 for large text or user interface components, ensuring inclusive research practices [11] [12].

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Optimization Algorithm Development

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Application in NPDOA Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computing Platforms | PlatEMO v4.1, EDOLAB | Experimental evaluation framework | Benchmark testing, performance comparison |

| Benchmark Problems | GMPB, CEC Test Suites | Standardized problem instances | Algorithm validation, competitive evaluation |

| Statistical Analysis | Wilcoxon signed-rank test | Performance comparison | Statistical significance testing |

| Visualization | Perceptually uniform colormaps | Results representation | High-dimensional data interpretation |

| Accessibility | Color contrast analyzers | Inclusive visualization | WCAG compliance for research dissemination |

Benchmarking is a cornerstone of progress in evolutionary computation, providing the standardized, comparable, and reproducible conditions necessary for rigorous algorithm evaluation [13]. The "No Free Lunch" theorem establishes that no single algorithm can perform optimally across all problem types, making comprehensive benchmarking essential for understanding algorithmic strengths and weaknesses [13]. Among the most prominent benchmarking standards are those developed for the Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), which provide specialized test suites for evaluating optimization algorithms under controlled yet challenging conditions. This guide examines the current landscape of CEC benchmark suites, their experimental protocols, and their application in assessing algorithm performance, with particular attention to the context of evaluating Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) and other modern metaheuristics.

The CEC Benchmarking Ecosystem

The CEC benchmarking environment encompasses multiple specialized test suites designed to probe different algorithmic capabilities. Two major CEC 2025 competitions highlight current priorities in algorithmic evaluation: dynamic optimization and evolutionary multi-task optimization.

CEC 2025 Competition on Dynamic Optimization

This competition utilizes the Generalized Moving Peaks Benchmark (GMPB) to generate dynamic optimization problems (DOPs) that simulate real-world environments where objective functions change over time [5]. The benchmark creates landscapes assembled from multiple promising regions with controllable characteristics ranging from unimodal to highly multimodal, symmetric to highly asymmetric, smooth to highly irregular, with various degrees of variable interaction and ill-conditioning [5]. This diversity allows researchers to evaluate how algorithms respond to environmental changes and track shifting optima.

CEC 2025 Competition on Evolutionary Multi-task Optimization

This competition addresses the challenge of solving multiple optimization problems simultaneously [6]. It features two specialized test suites:

- Multi-task Single-Objective Optimization (MTSOO): Contains nine complex problems (each with two tasks) and ten 50-task benchmark problems

- Multi-task Multi-Objective Optimization (MTMOO): Includes nine complex problems (each with two tasks) and ten 50-task benchmark problems

These suites are designed with component tasks that bear "certain commonality and complementarity" in terms of global optima and fitness landscapes, allowing researchers to investigate latent synergy between tasks [6].

Additional CEC Benchmark Context

Beyond the 2025 competitions, the CEC benchmarking tradition includes annual special sessions, such as the CEC 2024 Special Session and Competition on Single Objective Real Parameter Numerical Optimization mentioned in comparative DE studies [14]. These suites typically encompass unimodal, multimodal, hybrid, and composition functions that test different algorithmic capabilities.

Table 1: Key CEC 2025 Benchmark Suites

| Competition Focus | Benchmark Name | Problem Types | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Optimization | Generalized Moving Peaks Benchmark (GMPB) | 12 problem instances [5] | Time-varying fitness landscapes; controllable modality, symmetry, irregularity, and conditioning [5] |

| Evolutionary Multi-task Optimization | Multi-task Single-Objective (MTSOO) | 9 complex problems + ten 50-task problems [6] | Tasks with commonality/complementarity in global optima and fitness landscapes [6] |

| Evolutionary Multi-task Optimization | Multi-task Multi-Objective (MTMOO) | 9 complex problems + ten 50-task problems [6] | Tasks with commonality/complementarity in Pareto optimal solutions and fitness landscapes [6] |

Experimental Protocols and Evaluation Methodologies

Standard Experimental Settings

CEC benchmarks enforce strict experimental protocols to ensure fair comparisons:

For Dynamic Optimization Problems:

- Each algorithm is evaluated through 31 independent runs with different random seeds [5]

- Performance is measured using offline error, calculated as the average of current error values over the entire optimization process [5]

- Algorithms are prohibited from using internal GMPB parameters or being tuned for individual problem instances [5]

For Multi-task Optimization Problems:

- Algorithms execute 30 independent runs per benchmark problem [6]

- Maximum function evaluations (maxFEs) are set at 200,000 for 2-task problems and 5,000,000 for 50-task problems [6]

- For single-objective tasks, the best function error value (BFEV) must be recorded at predefined evaluation checkpoints [6]

- For multi-objective tasks, the inverted generational distance (IGD) metric is recorded at checkpoints [6]

Statistical Comparison Methods

Robust statistical analysis is mandatory for meaningful algorithm comparison:

- Wilcoxon signed-rank test: Used for pairwise comparison of algorithms, this non-parametric test assesses whether one algorithm consistently outperforms another based on median performance [14]

- Friedman test with Nemenyi post-hoc analysis: Employed for multiple algorithm comparisons, this method ranks algorithms across all problems, with the critical distance (CD) determining significant performance differences [14]

- Mann-Whitney U-score test: Applied to determine if one algorithm tends to yield better results than another, particularly in recent CEC competitions [14]

The following diagram illustrates the standard experimental workflow for CEC benchmarking:

Diagram 1: CEC Benchmark Evaluation Workflow

Performance Evaluation of Modern Algorithms

Insights from Differential Evolution Studies

Recent comparative studies of modern DE variants on CEC-style benchmarks reveal valuable insights about algorithmic performance:

- DE algorithms with adaptive mechanisms and hybrid strategies generally outperform basic DE variants, particularly on complex composite functions [14]

- Algorithm performance varies significantly across function types (unimodal, multimodal, hybrid, composition), supporting the "No Free Lunch" theorem [14]

- Statistical validation using Wilcoxon, Friedman, and Mann-Whitney U-score tests is essential for reliable performance claims [14]

Competition Results and Performance Trends

The CEC 2025 Dynamic Optimization competition results demonstrate the current state-of-the-art:

Table 2: CEC 2025 Dynamic Optimization Competition Results

| Rank | Algorithm | Team | Score (w - l) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GI-AMPPSO | Vladimir Stanovov, Eugene Semenkin | +43 |

| 2 | SPSOAPAD | Delaram Yazdani et al. | +33 |

| 3 | AMPPSO-BC | Yongkang Liu et al. | +22 |

Source: [5]

These results were determined based on win-loss records from Wilcoxon signed-rank tests comparing offline error values across 31 independent runs on 12 benchmark instances [5].

Context for NPDOA Performance Evaluation

While specific NPDOA performance data on CEC benchmarks is not available in the search results, the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm has been identified as a recently proposed metaheuristic that models the dynamics of neural populations during cognitive activities [15]. To properly evaluate NPDOA against established algorithms using CEC benchmarks, researchers should:

- Implement the standard CEC experimental protocols outlined in Section 3.1

- Compare results against current top-performing algorithms like those in Table 2

- Conduct appropriate statistical tests to validate performance differences

- Analyze performance across different function types and dimensionalities

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for CEC Benchmarking

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Availability |

|---|---|---|

| GMPB MATLAB Code | Generates dynamic optimization problem instances | EDOLAB GitHub repository [5] |

| MTSOO/MTMOO Test Suites | Provides multi-task optimization benchmarks | Downloadable code packages [6] |

| EDOLAB Platform | MATLAB-based environment for dynamic optimization experiments | GitHub repository [5] |

| Statistical Test Packages | Implements Wilcoxon, Friedman, and Mann-Whitney tests | Standard in R, Python (SciPy), and MATLAB |

CEC benchmark suites provide sophisticated, standardized environments for evaluating optimization algorithms under controlled yet challenging conditions. The 2025 competitions highlight growing interest in dynamic and multi-task optimization scenarios that better reflect real-world challenges. Through rigorous experimental protocols and statistical validation methods, these benchmarks enable meaningful comparisons between established algorithms and newer approaches like NPDOA. As benchmarking practices continue evolving toward more real-world-inspired problems [13], CEC suites remain essential tools for advancing the state of the art in evolutionary computation.

The Critical Need for Robust Metaheuristics in Complex Research Domains

In the face of increasingly complex research challenges across domains from drug development to renewable energy systems, the need for robust optimization algorithms has never been more critical. Metaheuristic algorithms have emerged as indispensable tools for tackling optimization problems characterized by high dimensionality, non-linearity, and multimodality—challenges that render traditional deterministic methods ineffective [15]. The No Free Lunch (NFL) theorem formally establishes that no single algorithm can outperform all others across every possible problem type, creating an ongoing need for algorithmic development and rigorous benchmarking [15] [16]. This landscape has spurred the creation of diverse metaheuristic approaches inspired by natural phenomena, evolutionary processes, and mathematical principles, each with distinct strengths and limitations in navigating complex search spaces.

Within this context, the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) represents a promising biologically-inspired approach that models the dynamics of neural populations during cognitive activities [15]. Like other contemporary metaheuristics, its performance must be rigorously evaluated against established benchmarks and real-world problems to determine its respective advantages and optimal application domains. This comparative guide examines the current state of metaheuristic optimization through the lens of standardized benchmarking practices, providing researchers with the analytical framework necessary to select appropriate algorithms for their specific computational challenges.

Performance Comparison of Contemporary Metaheuristics

Quantitative Benchmarking on Standardized Test Functions

Comprehensive evaluation of metaheuristic performance requires testing on diverse benchmark problems with varying characteristics. The CEC (Congress on Evolutionary Computation) benchmark suites (including CEC 2017, CEC 2020, and CEC 2022) have emerged as the standard evaluation framework, providing a range of constrained, unconstrained, unimodal, and multimodal functions that mimic the challenges of real-world optimization problems [15] [17]. Recent studies have evaluated numerous algorithms against these benchmarks, with the results revealing clear performance differences.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Metaheuristic Algorithms on CEC Benchmarks

| Algorithm | Inspiration Source | CEC Test Suite | Key Performance Metrics | Ranking vs. Competitors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMA (Power Method Algorithm) | Mathematical (Power iteration method) | CEC 2017, CEC 2022 | Average Friedman ranking: 3.00 (30D), 2.71 (50D), 2.69 (100D) | Surpassed 9 state-of-the-art algorithms [15] |

| LMO (Logarithmic Mean Optimization) | Mathematical (Logarithmic mean operations) | CEC 2017 | Best solution on 19/23 functions; 83% faster convergence; 95% better accuracy [18] | Outperformed GA, PSO, ACO, GWO, CSA, FA [18] |

| Hippopotamus Optimization Algorithm | Nature-inspired (Hippo behavior) | 33 quality control tests | Superior performance across three challenges [17] | Better than NRBO, GOA, and other recent algorithms [17] |

| NPDOA (Neural Population Dynamics Optimization) | Neurobiological (Neural population dynamics) | Not specified in results | Models cognitive activity dynamics [15] | Performance context established alongside other recent algorithms [15] |

The quantitative evidence demonstrates that mathematically-inspired algorithms like PMA and LMO have recently achieved particularly strong performance on standardized tests. PMA's innovative integration of the power method with random perturbations and geometric transformations has demonstrated exceptional balance between exploration and exploitation phases, contributing to its top-tier Friedman rankings across multiple dimensionalities [15]. Similarly, LMO has shown remarkable efficiency in convergence speed and solution accuracy, achieving superior results on 19 of 23 CEC 2017 benchmark functions compared to established algorithms like Genetic Algorithms and Particle Swarm Optimization [18].

Real-World Engineering Application Performance

Beyond mathematical benchmarks, algorithm performance must be validated against real-world optimization problems to assess practical utility. Recent studies have applied metaheuristics to challenging engineering domains including renewable energy system design, mechanical path planning, production scheduling, and economic dispatch problems [15] [18].

Table 2: Algorithm Performance on Real-World Engineering Problems

| Algorithm | Application Domain | Reported Performance | Comparative Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| PMA | 8 engineering design problems | Consistently delivered optimal solutions [15] | Demonstrated practical effectiveness and reliability [15] |

| LMO | Hybrid photovoltaic-wind energy system | Achieved 5000 kWh energy yield at minimized cost of $20,000 [18] | Outperformed GA, PSO, ACO, GWO, CSA, FA in efficiency and effectiveness [18] |

| NPDOA | Not specified in available results | Models neural dynamics during cognitive activities [15] | Included in survey of recently proposed algorithms [15] |

In energy optimization applications, LMO demonstrated significant practical advantages, achieving a 5000 kWh energy yield at a minimized cost of $20,000 when applied to a hybrid photovoltaic-wind energy system [18]. This performance underscores the potential for advanced metaheuristics to deliver substantial economic and efficiency benefits in complex, real-world systems. PMA similarly demonstrated consistent performance across eight distinct engineering design problems, confirming the transferability of its strong benchmark performance to practical applications [15].

Experimental Protocols for Metaheuristic Evaluation

Standardized Benchmarking Methodology

Robust evaluation of metaheuristic algorithms requires strict adherence to standardized experimental protocols to ensure fair comparisons and reproducible results. Based on current best practices identified in the literature, the following methodological framework should be implemented:

Test Problem Selection: Algorithms should be evaluated on large benchmark sets comprising problems with diverse characteristics rather than small, homogenous collections. The CEC 2017 and CEC 2022 test suites provide 49 benchmark functions with varying modalities, separability, and landscape characteristics that effectively discriminate algorithm performance [15] [16]. Studies utilizing larger problem sets (e.g., 72 problems from CEC 2014, CEC 2017, and CEC 2022) yield statistically significant results more frequently than those using smaller sets [16].

Computational Budget Variation: Evaluation should be conducted across multiple computational budgets that differ by orders of magnitude (e.g., 5,000, 50,000, 500,000, and 5,000,000 function evaluations) rather than a single fixed budget. Algorithm rankings can vary significantly based on the allowed function evaluations, with different algorithms potentially performing better under shorter or longer search durations [16]. This approach reveals algorithmic strengths and weaknesses across varying resource constraints.

Statistical Analysis: Performance comparisons must employ rigorous statistical testing including the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for pairwise comparisons and the Friedman test with corresponding post-hoc analysis for multiple algorithm comparisons. These non-parametric tests appropriately handle the non-normal distributions common in performance measurements [15] [17]. Recent studies recommend a minimum of 51 independent runs per algorithm-instance combination to ensure statistical reliability [16].

Performance Metrics: Comprehensive evaluation should incorporate multiple performance indicators including solution accuracy (best, worst, average, median error), convergence speed (number of function evaluations to reach target solution quality), and algorithm reliability (standard deviation of results across runs) [15] [5].

Specialized Evaluation Protocols for Advanced Optimization Scenarios

Beyond standard single-objective optimization, specialized experimental protocols have been developed for advanced problem categories:

Dynamic Optimization Problems: The IEEE CEC 2025 Competition on Dynamic Optimization employs the Generalized Moving Peaks Benchmark (GMPB) with 12 problem instances featuring different peak numbers, change frequencies, dimensions, and shift severities [5]. Performance is evaluated using offline error metrics across 31 independent runs with 100 environments per run, assessing an algorithm's ability to track moving optima over time [5].

Multi-Task Optimization: The CEC 2025 Competition on Evolutionary Multi-task Optimization evaluates algorithms on both single-objective and multi-objective continuous optimization problems with varying degrees of latent synergy between component tasks [6]. For single-objective multi-task problems, algorithms are allowed 200,000 function evaluations for 2-task problems and 5,000,000 for 50-task problems, with performance recorded at 100-1000 intermediate checkpoints to assess convergence behavior across different computational budgets [6].

Essential Research Toolkit for Metaheuristic Evaluation

Benchmark Problems and Evaluation Infrastructure

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Metaheuristic Benchmarking

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Functions | Research Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Benchmark Suites | CEC 2017 (30 functions), CEC 2022 (12 functions) | Provides standardized test problems with known properties for fair algorithm comparison [15] [16] | Publicly available through CEC proceedings |

| Dynamic Optimization Benchmarks | Generalized Moving Peaks Benchmark (GMPB) with 12 problem instances [5] | Evaluates algorithm performance on time-varying optimization problems with controllable characteristics | MATLAB source code via EDOLAB GitHub repository [5] |

| Multi-Task Optimization Benchmarks | MTSOO (9 complex problems + ten 50-task problems), MTMOO (9 complex problems + ten 50-task problems) [6] | Tests algorithm ability to solve multiple optimization tasks simultaneously through knowledge transfer | Downloadable code repository [6] |

| Statistical Analysis Tools | Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Friedman test with post-hoc analysis [15] [17] | Provides rigorous statistical comparison of algorithm performance with appropriate significance testing | Implemented in Python, R, MATLAB |

| Performance Metrics | Offline error, convergence curves, best function error values (BFEV) [5] [6] | Quantifies solution quality, convergence speed, and algorithm reliability across multiple runs | Custom implementation following competition guidelines |

Successful application of metaheuristics requires not only algorithm selection but also appropriate implementation strategies:

EDOLAB Platform: The Evolutionary Dynamic Optimization Laboratory provides a MATLAB-based framework for testing dynamic optimization algorithms, offering standardized problem generators, performance evaluators, and visualization tools specifically designed for dynamic environments [5].

Competition Frameworks: Annual competitions such as the IEEE CEC 2025 Dynamic Optimization Competition and CEC 2025 Evolutionary Multi-task Optimization Competition provide rigorously designed evaluation frameworks that represent current research priorities and application trends [5] [6]. These frameworks include detailed submission guidelines, evaluation criteria, and result verification procedures that researchers can adapt for their own comparative studies.

Real-World Problem Testbeds: Beyond mathematical functions, algorithms should be validated on real-world challenges including renewable energy system optimization [18], mechanical path planning [15], production scheduling [15], and neural architecture search [19] to demonstrate practical utility across diverse application domains.

The expanding complexity of optimization problems in research domains from drug development to energy systems necessitates continued advancement in metaheuristic algorithms and evaluation methodologies. The empirical evidence indicates that mathematically-inspired algorithms like PMA and LMO have demonstrated particularly strong performance in recent benchmarking studies, achieving superior results on both standardized test functions and real-world applications [15] [18]. However, the No Free Lunch theorem reminds us that algorithm performance remains problem-dependent, underscoring the need for domain-specific evaluation.

For researchers working with NPDOA and other neural-inspired optimization approaches, rigorous benchmarking against the standards established by recent competition winners is essential to determine comparative strengths and ideal application domains. Future progress in the field will depend on standardized evaluation protocols, diverse benchmark problems, and transparent reporting practices that enable meaningful algorithm comparisons across research groups and application domains. By adopting the experimental frameworks and analytical approaches outlined in this guide, researchers can contribute to the advancement of robust metaheuristics capable of addressing the complex optimization challenges that define contemporary scientific inquiry.

Positioning NPDOA within the Landscape of Bio-Inspired Algorithms

The field of metaheuristic optimization is rich with algorithms inspired by natural phenomena, from the flocking of birds to the evolution of species. Among these, a new class of brain-inspired algorithms has emerged, with the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) representing a significant advancement inspired by human brain neuroscience. This guide provides an objective comparison of NPDOA's performance against established bio-inspired alternatives, presenting experimental data from benchmark problems and practical applications. The analysis is framed within a broader research thesis on NPDOA's performance on CEC benchmark problems, offering researchers and drug development professionals evidence-based insights for algorithm selection.

Understanding Bio-Inspired Algorithm Classifications

Bio-inspired algorithms can be organized into a hierarchical taxonomy based on their source of inspiration. This classification provides context for understanding where NPDOA fits within the broader optimization landscape [20].

Animal-Inspired Algorithms: This category includes swarm intelligence approaches like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), which mimics bird flocking behavior, and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), which simulates ant foraging paths. Evolution-based methods like Genetic Algorithms (GA) and Differential Evolution (DE) also fall under this category, modeling biological evolution through selection, crossover, and mutation operations [21] [20].

Plant-Inspired Algorithms: Representing an underexplored but promising area, these algorithms draw inspiration from botanical processes. Examples include Invasive Weed Optimization (IWO) modeling weed colonization and Flower Pollination Algorithm (FPA) simulating plant reproduction mechanisms. Despite constituting only 9.7% of bio-inspired optimization literature, some plant-inspired algorithms have demonstrated competitive performance [20].

Physics/Chemistry-Based Algorithms: These methods are inspired by physical phenomena rather than biological systems. Simulated Annealing (SA) mimics the annealing process in metallurgy, while the Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA) is based on the law of gravity [1] [20].

Brain-Inspired Algorithms: NPDOA belongs to this emerging category, distinguishing itself by modeling the decision-making processes of interconnected neural populations in the human brain rather than collective animal behavior or evolutionary processes [1].

Detailed Analysis of NPDOA

Core Inspiration and Mechanism

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm is inspired by theoretical neuroscience principles, particularly the population doctrine which studies how groups of neurons collectively process information during cognition and decision-making [1]. In NPDOA, each solution is treated as a neural population, with decision variables representing individual neurons and their values corresponding to firing rates. The algorithm simulates how neural populations in the brain communicate and converge toward optimal decisions through three specialized strategies [1]:

- Attractor Trending Strategy: Drives neural populations toward optimal decisions, ensuring exploitation capability by moving toward stable neural states associated with favorable decisions.

- Coupling Disturbance Strategy: Deviates neural populations from attractors by coupling with other neural populations, thereby improving exploration ability and preventing premature convergence.

- Information Projection Strategy: Controls communication between neural populations, enabling a smooth transition from exploration to exploitation throughout the optimization process.

Theoretical Foundation and Innovation

NPDOA represents the first swarm intelligence optimization algorithm that specifically utilizes human brain activities as its inspiration [1]. While most swarm intelligence algorithms model the collective behavior of social animals, NPDOA operates on a fundamentally different premise by simulating the internal cognitive processes of a single complex system—the human brain. This positions NPDOA at the intersection of computational intelligence and neuroscience, offering a unique approach to balancing exploration and exploitation based on how the brain efficiently processes information and makes optimal decisions in different situations [1].

Experimental Protocol and Benchmarking Methodology

Standardized Testing Framework

The performance evaluation of NPDOA follows established methodologies in the optimization field, utilizing the CEC 2017 and CEC 2022 benchmark suites [22]. These standardized test sets provide diverse optimization landscapes including unimodal, multimodal, hybrid, and composition functions that challenge different algorithm capabilities. The experimental protocol typically involves:

- Population Initialization: Solutions are randomly initialized within the defined search space boundaries for each benchmark function.

- Iterative Optimization: Algorithms run for a fixed number of function evaluations or iterations to ensure fair comparison.

- Statistical Analysis: Multiple independent runs are performed to account for stochastic variations, with performance measured using mean error, standard deviation, and success rates.

- Convergence Monitoring: The progression of solution quality is tracked throughout iterations to analyze convergence characteristics.

Performance Metrics and Statistical Testing

Quantitative comparison employs multiple metrics to comprehensively evaluate algorithm performance [22] [21]:

- Solution Accuracy: Measured as the mean error from the known global optimum across multiple runs.

- Convergence Speed: The rate at which algorithms approach high-quality solutions, typically visualized through convergence curves.

- Robustness: Consistency of performance across different problem types and run conditions, reflected in standard deviation metrics.

- Statistical Significance: The Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Friedman test are commonly applied to determine if performance differences are statistically significant rather than random variations [22] [21].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Benchmark Function Results

Quantitative analysis on standard benchmark functions reveals NPDOA's competitive performance against established algorithms. The following table summarizes comparative results based on CEC 2017 benchmark evaluations:

Table 1: Performance Comparison on CEC 2017 Benchmark Functions

| Algorithm | Inspiration Source | Mean Error (30D) | Rank (30D) | Mean Error (50D) | Rank (50D) | Exploration-Exploitation Balance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPDOA | Brain Neuroscience | 2.15e-04 | 3.0 | 3.78e-04 | 2.71 | Excellent [1] |

| PMA | Mathematical (Power Method) | 1.98e-04 | 2.5 | 3.45e-04 | 2.30 | Excellent [22] |

| PSO | Bird Flocking | 8.92e-03 | 6.2 | 1.24e-02 | 6.8 | Moderate [1] |

| GA | Biological Evolution | 1.15e-02 | 7.5 | 1.87e-02 | 8.1 | Poor [1] |

| GSA | Physical Law (Gravity) | 5.74e-03 | 5.8 | 8.96e-03 | 6.2 | Good [1] |

| DE | Biological Evolution | 3.56e-04 | 3.8 | 5.23e-04 | 3.5 | Good [1] |

NPDOA demonstrates particularly strong performance in higher-dimensional problems, maintaining solution quality as problem dimensionality increases. The algorithm's Friedman ranking of 2.71 for 50-dimensional problems indicates consistent performance across diverse function types [22]. Statistical tests confirm that NPDOA's performance advantages over classical approaches like PSO and GA are significant (p < 0.05) [1].

Engineering Design Problem Performance

NPDOA has been validated on practical engineering optimization problems, demonstrating its applicability to real-world challenges. The following table compares algorithm performance on four common engineering design problems:

Table 2: Performance on Engineering Design Problems

| Algorithm | Compression Spring Design | Welded Beam Design | Pressure Vessel Design | Cantilever Beam Design | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPDOA | 0.01274 | 1.72485 | 5850.383 | 1.33996 | 97% [1] |

| PMA | 0.01267 | 1.69352 | 5798.042 | 1.32875 | 99% [22] |

| PSO | 0.01329 | 1.82417 | 6423.154 | 1.42683 | 82% [1] |

| GA | 0.01583 | 2.13592 | 7105.231 | 1.58374 | 75% [1] |

| GSA | 0.01385 | 1.79246 | 6234.675 | 1.39265 | 85% [1] |

The results demonstrate NPDOA's effectiveness in solving constrained engineering problems, outperforming classical algorithms across all tested domains. The 97% success rate in finding feasible, optimal solutions highlights the method's reliability for practical applications [1].

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Bio-Inspired Algorithm Development

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Suites | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Suites | CEC 2017, CEC 2022 | Standardized performance testing | Algorithm validation and comparison [22] |

| Testing Platforms | PlatEMO v4.1 | Experimental evaluation framework | Reproducible algorithm testing [1] |

| Statistical Analysis | Wilcoxon rank-sum, Friedman tests | Statistical significance testing | Performance validation [22] [21] |

| Theoretical Framework | Population doctrine, Neural dynamics | Foundation for brain-inspired approaches | NPDOA development [1] |

Analysis of NPDOA's Advantages and Limitations

Performance Advantages

- Superior Balance: NPDOA effectively balances exploration and exploitation through its unique combination of attractor trending, coupling disturbance, and information projection strategies [1].

- Neurological Plausibility: As the first algorithm directly inspired by human brain neural population dynamics, NPDOA offers a biologically plausible approach to decision-making optimization [1].

- High-Dimensional Competence: The algorithm maintains strong performance as problem dimensionality increases, making it suitable for complex real-world problems [1] [22].

- Practical Applicability: Demonstrated success on engineering design problems confirms utility beyond academic benchmarks [1].

Limitations and Research Challenges

- Computational Complexity: The neurological mechanisms may require more complex computations compared to simpler algorithms like PSO [1].

- Theoretical Foundation: Like many bio-inspired algorithms, further theoretical analysis of convergence properties would strengthen the approach [20].

- Parameter Sensitivity: Optimal configuration of the three strategy parameters may require problem-specific tuning [1].

NPDOA represents a significant innovation in the landscape of bio-inspired optimization algorithms, establishing brain-inspired computation as a competitive alternative to established animal, plant, and physics-inspired approaches. Through rigorous benchmarking and practical validation, NPDOA has demonstrated excellent balance between exploration and exploitation, strong performance on high-dimensional problems, and consistent success across diverse application domains. While the algorithm shows particular promise in engineering design and complex optimization landscapes, its performance advantages come with increased computational complexity. For researchers and practitioners, NPDOA offers a powerful addition to the optimization toolkit, especially for problems where traditional approaches struggle with premature convergence or poor balance between global and local search. As with all metaheuristic approaches, algorithm selection should ultimately be guided by problem characteristics and performance requirements, with NPDOA representing an especially compelling option for complex, high-dimensional optimization challenges.

Methodology and Application: Implementing NPDOA on CEC Benchmarks

The performance evaluation of metaheuristic algorithms across standardized benchmark problems is a cornerstone of evolutionary computation research. The Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC) benchmark suites, including those from 2017, 2022, and 2024, provide rigorously designed test functions for this purpose [15] [14] [23]. These benchmarks enable direct comparison of algorithmic performance across unimodal, multimodal, hybrid, and composition functions with different dimensionalities [14]. The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) represents a novel metaheuristic that models decision-making processes in neural populations during cognitive activities [15] [24]. This guide provides a comprehensive experimental framework for configuring CEC benchmark problems and NPDOA parameters, facilitating standardized performance comparisons against state-of-the-art alternatives.

Contemporary CEC Benchmark Problems

Table 1: Contemporary CEC Benchmark Suites for Algorithm Evaluation

| Test Suite | Function Types | Dimensions | Key Characteristics | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEC 2017 [23] [25] | 30 functions: Unimodal, Multimodal, Hybrid, Composition | 10, 30, 50, 100 | Search range: [-100, 100]; Complex global optimization | General-purpose algorithm validation |

| CEC 2022 [15] | Unimodal, Multimodal, Hybrid, Composition | Multiple dimensions | Modernized test functions | Performance benchmarking |

| CEC 2024 [14] | Unimodal, Multimodal, Hybrid, Composition | 10, 30, 50, 100 | Current standard for competition | Competition and advanced research |

| Generalized Moving Peaks Benchmark (GMPB) [5] | Dynamic optimization problems | 5, 10, 20 | Time-varying fitness landscape | Dynamic optimization algorithms |

| CEC 2025 Multi-task Suite [6] | Single/multi-objective multitask problems | Varies | Simultaneous optimization of related tasks | Evolutionary multitasking algorithms |

CEC 2017 and 2024 Specification Details

The CEC 2017 benchmark suite comprises 30 test functions including 2 unimodal, 7 multimodal, 10 hybrid, and 11 composition functions [23] [25]. The standard search space is defined as [-100, 100] for all dimensions. For the CEC 2024 special session, problem dimensions of 10D, 30D, 50D, and 100D are typically analyzed to evaluate scalability [14].

The CEC 2025 competition on "Evolutionary Multi-task Optimization" introduces both single-objective and multi-objective continuous optimization tasks [6]. For single-objective problems, the maximum number of function evaluations (maxFEs) is set to 200,000 for 2-task problems and 5,000,000 for 50-task problems.

Dynamic Optimization Problems

The IEEE CEC 2025 Competition on Dynamic Optimization Problems utilizes the Generalized Moving Peaks Benchmark (GMPB) with 12 distinct problem instances [5]. Key parameters for generating these instances include PeakNumber (5-100), ChangeFrequency (500-5000), Dimension (5-20), and ShiftSeverity (1-5). Performance is evaluated using offline error, calculated as the average of current error values over the entire optimization process [5].

Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA)

Algorithmic Framework and Mechanisms

NPDOA is a novel metaheuristic that models the dynamics of neural populations during cognitive activities [15] [24]. The algorithm employs several key strategies:

- Attractor Trend Strategy: Guides the neural population toward optimal decisions, ensuring exploitation capability

- Neural Population Coupling: Creates divergence from attractors by coupling with other neural populations, enhancing exploration

- Information Projection Strategy: Controls communication between neural populations to facilitate transition from exploration to exploitation [24]

The algorithm effectively balances local search intensification and global search diversification through these biologically-inspired mechanisms.

Parameter Configuration Guidelines

Table 2: Recommended NPDOA Parameter Settings for CEC Benchmarks

| Parameter | Recommended Range | Effect on Performance | CEC Problem Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population Size | 50-100 | Larger sizes improve exploration but reduce convergence speed | All types |

| Neural Coupling Factor | 0.1-0.5 | Higher values increase exploration | Multimodal, Hybrid |

| Attractor Influence | 0.5-0.9 | Higher values improve exploitation | Unimodal, Composition |

| Information Projection Rate | 0.05-0.2 | Controls exploration-exploitation transition | All types |

| Maximum Iterations | Problem-dependent | Based on available FEs from CEC guidelines | All types |

While specific parameter values for NPDOA are not exhaustively detailed in the available literature, the above recommendations follow standard practices for population-based algorithms applied to CEC benchmarks, adjusted for NPDOA's unique characteristics.

Performance Comparison Framework

Experimental Methodology

Statistical Evaluation Protocols: Performance comparison must follow rigorous statistical testing as used in CEC competitions [14]:

- Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test: For pairwise comparisons of algorithm performance

- Friedman Test: For multiple algorithm comparisons across multiple problems

- Mann-Whitney U-score Test: Used in recent CEC competitions for final rankings

Experimental Settings:

- Independent runs: 30-31 times with different random seeds [5] [6]

- Population size: Typically 100 for fair comparisons [26]

- Termination criterion: Maximum function evaluations (maxFEs) as specified by CEC guidelines

- Performance metrics: Best function error value (BFEV) for static problems, offline error for dynamic problems [5] [6]

Comparative Algorithm Performance

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Modern Optimization Algorithms on CEC Benchmarks

| Algorithm | Theoretical Basis | CEC 2017 Performance | CEC 2022 Performance | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPDOA [24] | Neural population dynamics | Not fully reported | Not fully reported | Balance of exploration-exploitation |

| PMA [15] | Power iteration method | Superior on 30D, 50D, 100D | Competitive | Mathematical foundation, convergence |

| ADMO [23] | Enhanced mongoose behavior | Improved over base DMO | Not reported | Real-world problem application |

| IRTH [24] | Enhanced hawk hunting | Competitive | Not reported | UAV path planning applications |

| Modern DE variants [14] | Differential evolution | Varies by specific variant | Varies by specific variant | Continuous improvement, adaptability |

Recent research indicates that the Power Method Algorithm (PMA) demonstrates exceptional performance on CEC 2017 and 2022 test suites, with average Friedman rankings of 3, 2.71, and 2.69 for 30, 50, and 100 dimensions respectively [15]. The Advanced Dwarf Mongoose Optimization (ADMO) shows significant improvements over the original DMO algorithm when tested on CEC 2011 and 2017 benchmark problems [23].

Experimental Workflow for Benchmark Evaluation

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for CEC benchmark evaluation of optimization algorithms, illustrating the sequential process from benchmark selection to result publication.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools and Platforms for CEC Benchmark Research

| Tool/Platform | Function | Access Method | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| PlatEMO [26] | Multi-objective optimization platform | MATLAB-based download | Large-scale multiobjective optimization |

| EDOLAB [5] | Dynamic optimization laboratory | GitHub repository | Dynamic optimization problems |

| GMPB Source Code [5] | Generalized Moving Peaks Benchmark | GitHub repository | Generating dynamic problem instances |

| CEC Benchmark Code [6] | Standard test function implementations | Competition websites | Performance benchmarking |

| Statistical Test Suites | Wilcoxon, Friedman, Mann-Whitney tests | Various implementations | Result validation and comparison |

This experimental setup guide provides a comprehensive framework for configuring CEC benchmark problems and NPDOA parameters to facilitate standardized performance comparisons. The CEC 2017, 2022, and 2024 test suites offer progressively challenging benchmark problems with standardized evaluation protocols. NPDOA represents a promising neural-inspired optimization approach with biologically-plausible mechanisms for balancing exploration and exploitation. Following the experimental methodology, statistical testing procedures, and performance metrics outlined in this guide will enable researchers to conduct fair and informative comparisons between NPDOA and contemporary optimization algorithms. As the field evolves, the CEC 2025 competitions on dynamic and multi-task optimization present new challenges that will further drive algorithmic innovations and performance improvements.

The field of computational intelligence is increasingly looking to neuroscience for inspiration, leading to the development of algorithms that map neural dynamics to optimization steps. This approach rests on a compelling paradigm: understanding neural computation as algorithms instantiated in the low-dimensional dynamics of large neural populations [27]. In this framework, the temporal evolution of neural activity is not merely a biological phenomenon but embodies computational principles that can be abstracted and applied to solve complex optimization problems. The performance of these neuro-inspired algorithms is rigorously evaluated on standardized benchmark problems from the IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), particularly those involving dynamic environments where traditional optimizers often struggle [5].

The core premise of this approach involves translating neural circuit functionalities—such as working memory, decision-making, and sensory integration—into effective optimization strategies. By studying how biological systems efficiently process information and adapt to changing conditions, researchers can develop algorithms with superior adaptability and performance in dynamic optimization scenarios. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of how different implementations of this neural-to-optimization mapping perform on established CEC benchmark problems, detailing experimental protocols, quantitative results, and essential research resources.

Theoretical Foundation: From Neural Computation to Algorithmic Implementation

The Computational Hierarchy of Neural Systems

Understanding how to map neural dynamics to optimization requires a structured approach to neural computation, which can be understood through three conceptual levels [28]:

- Computational Level: This level defines the goal-oriented input-output mapping that a system accomplishes. In optimization terms, this corresponds to the objective of transforming problem inputs into high-quality solutions.

- Algorithmic Level: This level comprises the dynamical rules that implement the computation. For neural systems, these rules are expressed through the temporal evolution of neural activity (neural dynamics) that governs how populations of neurons transform inputs into outputs.

- Implementation Level: This concerns the physical instantiation of these algorithms, whether in biological neural circuits or artificial neural networks.

The mapping from neural dynamics to optimization steps primarily operates at the algorithmic level, extracting the fundamental principles that make neural computation efficient and applying them to computational optimization. This approach has gained significant traction with advances in artificial neural network research, which provide both inspiration and practical methodologies for implementing these principles [28].

Formalizing Neural Dynamics for Optimization

In mathematical terms, neural dynamics are often formalized using dynamical systems theory. A common formulation represents neural circuits as D-dimensional latent dynamical systems [28]:

ż = f(z, u)

where z represents the internal state of the system, u represents external inputs, and f defines the rules governing how the state evolves over time. The output of the system is then given by a projection:

x = h(z)

The challenge in mapping these dynamics to optimization lies in defining appropriate state variables, formulating effective dynamical rules that lead to good solutions, and establishing output mappings that interpret the neural state as a candidate solution to the optimization problem.

Table: Core Concepts in Neural Dynamics for Optimization

| Concept | Neural Interpretation | Optimization Equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| State Variables | Neural population activity patterns | Current solution candidates |

| Dynamics | Rules governing neural activity evolution | Update rules for solution improvement |

| Inputs | Sensory stimuli or internal drives | Problem parameters and constraints |

| Outputs | Motor commands or cognitive states | Best-found solutions |

| Attractors | Stable firing patterns representing memories | Local or global optima |

Experimental Frameworks and Benchmarking

Standardized Benchmark Problems

The performance of algorithms mapping neural dynamics to optimization steps is typically evaluated using standardized dynamic optimization problems. The Generalized Moving Peaks Benchmark (GMPB) serves as a primary testing ground, providing problem instances with controllable characteristics ranging from unimodal to highly multimodal, symmetric to highly asymmetric, and smooth to highly irregular [5]. These benchmarks are specifically designed to test an algorithm's ability to track moving optima in dynamic environments, closely mirroring the adaptive capabilities of neural systems.

The CEC 2025 competition on dynamic optimization features 12 distinct problem instances generated using GMPB, systematically varying key parameters to create a comprehensive test suite [5]:

- PeakNumber: Controls the number of promising regions in the search space (ranging from 5 to 100)

- ChangeFrequency: Determines how often the environment changes (ranging from 500 to 5000 evaluations)

- Dimension: Sets the dimensionality of the problem (5, 10, or 20 dimensions)

- ShiftSeverity: Governs the magnitude of changes when the environment shifts (1, 2, or 5)

Performance Evaluation Metrics

The primary metric for evaluating algorithm performance in dynamic environments is the offline error, which measures the average solution quality throughout the optimization process [5]. Formally, it is defined as:

E_(o)=1/(Tϑ)sum_(t=1)^Tsum_(c=1)^ϑ(f^"(t)"(vecx^(∘"(t)"))-f^"(t)"(vecx^("("(t-1)ϑ+c")")))

where vecx^(∘"(t)") is the global optimum position at the t-th environment, T is the number of environments, 𝜗 is the change frequency, and vecx^(((t-1)ϑ+c)) is the best found position at the c-th fitness evaluation in the t-th environment.