Ensuring Reliability in Neuroimaging Pipelines: A Framework for Reproducible Research and Drug Development

This article addresses the critical challenge of reliability and reproducibility in neuroimaging pipelines, a central concern for researchers and drug development professionals.

Ensuring Reliability in Neuroimaging Pipelines: A Framework for Reproducible Research and Drug Development

Abstract

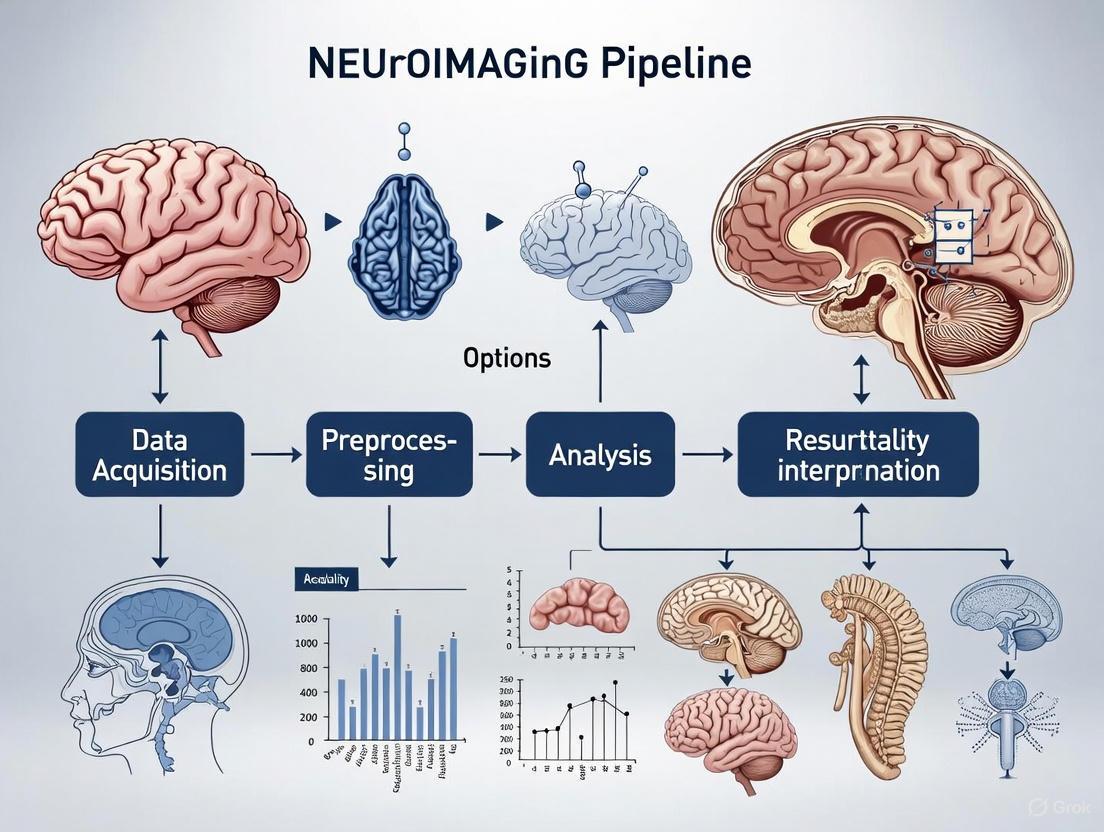

This article addresses the critical challenge of reliability and reproducibility in neuroimaging pipelines, a central concern for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational sources of methodological variability introduced by software, parcellation, and quality control choices, demonstrating their significant impact on both group-level inference and individual prediction tasks. The content evaluates next-generation, deep learning-based pipelines that offer substantial acceleration and enhanced robustness for large-scale datasets and clinical applications. Furthermore, it provides a rigorous framework for reliability assessment and validation, covering standardized metrics, comparative performance evaluation, and optimization strategies for troubleshooting pipeline failures. By synthesizing evidence from recent large-scale comparative studies and emerging technologies, this guide aims to equip scientists with practical knowledge to design robust, efficient, and reliable neuroimaging workflows for both research and clinical trial contexts.

The Reproducibility Crisis: Understanding Sources of Variability in Neuroimaging Analysis

FAQs: Core Concepts for Pipeline Reliability

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between replicability and generalizability in a neuroimaging context?

Replicability refers to obtaining consistent results when repeating an experiment or analysis under the same or very similar conditions (e.g., the same lab, scanner, and participant population). Generalizability, or external validity, refers to the ability of a result to apply to a different but related context, such as a novel sample from a different population, a different data acquisition site, or a different scanner model [1].

Q2: Why are large sample sizes increasingly emphasized for population neuroscience studies?

Brain-behavior associations, particularly in psychiatry, typically have very small effect sizes (e.g., maximum correlations of ~0.10 between brain connectivity and mental health symptoms) [2]. Small samples (e.g., tens to hundreds of participants) exhibit high sampling variability, leading to inflated effect sizes, false positives, and ultimately, replication failures. Samples in the thousands are required to achieve the statistical power necessary for replicable and accurate effect size estimation [2] [3].

Q3: How can my pipeline be replicable but not generalizable?

A pipeline can produce highly consistent results within a specific, controlled dataset but fail when applied elsewhere. This often occurs due to "shortcut learning," where a machine learning model learns an association between the brain and an unmeasured, dataset-specific construct (the "shortcut") rather than the intended target of mental health [2] [3]. For example, a model might leverage site-specific scanner artifacts for prediction, which do not transfer to other sites.

Q4: What technological solutions can enhance the trustworthiness of my pipeline's output?

Cyberinfrastructure solutions like the Open Science Chain (OSC) can be integrated. The OSC uses consortium blockchain to maintain immutable, timestamped, and verifiable integrity and provenance metadata for published datasets and workflow artifacts. Storing cryptographic hashes of data and metadata in this "append-only" ledger allows for independent verification, fostering trust and promoting reuse [4].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Pipeline Issues and Solutions

Issue: Inconsistent Functional Connectomics Results Across Research Groups

- Problem: Different groups analyzing the same data obtain different conclusions about brain network organization.

- Diagnosis: This is a classic problem of combinatorial pipeline variability. A single choice in node definition, edge weighting, or global signal processing can drastically alter results [5].

- Solution:

- Systematic Evaluation: Systematically evaluate your pipeline choices against multiple criteria. Do not optimize for a single metric.

- Adopt Verified Pipelines: Use pipelines that have been validated against key criteria. A systematic evaluation of 768 pipelines identified optimal ones that minimize motion confounds and spurious test-retest discrepancies while remaining sensitive to inter-subject differences and experimental effects [5]. Key performance criteria are summarized in Table 1 below.

- Be Transparent: Fully report all pipeline choices, including parcellation, connectivity metric, and global signal regression usage.

Issue: fMRIPrep Crashes with 'Operation not permitted' Error on a Compute Cluster

- Problem: fMRIPrep runs successfully manually but crashes with

shutil.Errorand[Errno 1] Operation not permittedwhen executed through a cluster management system, specifically when copying the 'fsaverage' files [6]. - Diagnosis: This is likely a file permissions incompatibility arising from the interaction between the Singularity container, the cluster's architecture, and how the pipeline is invoked. The system may be setting up data with a user ID that is not compatible with the container's operations.

- Solution:

- Investigate the

-uUID Option: Although you may not be using it, the underlying issue is related to user ID mapping. Deliberately using the-uoption with Singularity to set a specific user ID (e.g.,-u 0for root) may resolve the permission conflict [6]. - Pre-copy fsaverage: As a workaround, try copying the

fsaveragedirectory from inside the container to your target output directory before running fMRIPrep, ensuring it has full read/write permissions.

- Investigate the

Quantitative Data on Pipeline Performance

Table 1: Performance Criteria for Evaluating fMRI Processing Pipelines for Functional Connectomics [5]

| Criterion | Description | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Test-Retest Reliability | Minimizes spurious differences in network topology from repeated scans of the same individual. | Fundamental for studying individual differences. Unreliable pipelines produce misleading associations with traits or clinical outcomes. |

| Motion Robustness | Minimizes the confounding influence of head motion on network topology. | Prevents false findings driven by motion artifacts rather than neural signals. |

| Sensitivity to Individual Differences | Able to detect consistent, unique network features that distinguish one individual from another. | Essential for personalized medicine or biomarker discovery. |

| Sensitivity to Experimental Effects | Able to detect changes in network topology due to a controlled intervention (e.g., pharmacological challenge). | Ensures the pipeline can capture biologically relevant, stimulus-driven changes in brain function. |

| Generalizability | Performs consistently well across multiple independent datasets with different acquisition parameters and preprocessing methods. | Protects against overfitting to a specific dataset's properties and ensures broader scientific utility. |

Table 2: Benchmark Effect Sizes in Population Psychiatric Neuroimaging [2]

| Brain-Behavior Relationship | Dataset | Sample Size (N) | Observed Maximum Correlation (r) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resting-State Functional Connectivity (RSFC) vs. Fluid Intelligence | Human Connectome Project (HCP) | 900 | ~0.21 |

| RSFC vs. Fluid Intelligence | Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study | 3,928 | ~0.12 |

| RSFC vs. Fluid Intelligence | UK Biobank (UKB) | 32,725 | ~0.07 |

| Brain Measures vs. Mental Health Symptoms | ABCD Study | 3,928 | ~0.10 |

Experimental Protocols for Reliability Assessment

This protocol outlines a two-step process for translating a neuroimaging finding from the lab toward clinical application.

Replication Experiments:

- Objective: To measure the precision of a finding when the experiment is repeated as precisely as possible.

- Method: Perform test-retest measurements on the same or a highly matched population, using the same data acquisition instruments (e.g., the same scanner and sequence) and the same computational pipeline.

- Outcome Measurement: Quantify the intra-class correlation (ICC) or other reliability metrics for the key output measures (e.g., fractional anisotropy, network metric).

Generalization Experiments:

- Objective: To test the extent of applicability of the replicated finding.

- Method: Conduct experiments that share the same core design but systematically vary one or more parameters:

- Population: Test on participants from different geographic locales, age groups, or clinical backgrounds.

- Data Acquisition: Use different scanner models, manufacturers, or pulse sequences.

- Computational Methods: Apply different preprocessing software or algorithmic parameters.

- Outcome Measurement: Assess how the key output measure and its reliability change across these varying conditions.

This protocol describes a comprehensive method for identifying optimal pipelines for functional connectomics.

Define the Pipeline Variable Space: Systematically combine choices across key steps:

- Global Signal Regression: With or without.

- Brain Parcellation: Use 4 different types (anatomical, functional, etc.) at 3 different resolutions (~100, 200, 300-400 nodes).

- Edge Definition: Use Pearson correlation or mutual information.

- Edge Filtering: Apply 8 different methods (e.g., density-based thresholding, data-driven methods).

- Network Type: Binary or weighted.

- This creates 768 unique, end-to-end pipelines for evaluation.

Evaluate on Multiple Independent Datasets: Run the evaluation on at least two independent test-retest datasets, spanning different time delays (e.g., minutes, weeks, months).

Apply Multi-Criteria Assessment: Evaluate each pipeline against the criteria listed in Table 1, using a robust metric like Portrait Divergence (PDiv) that compares whole-network topology.

Identify Optimal Pipelines: Select pipelines that satisfy all criteria (high test-retest reliability, motion robustness, and sensitivity to effects of interest) across all datasets.

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Diagrams

Diagram: Two-Step Framework for Reliability Assessment

Diagram: Combinatorial Explosion in fMRI Pipeline Construction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Resources for Neuroimaging Pipeline Research

| Resource / Reagent | Type | Primary Function / Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Open Science Chain (OSC) [4] | Cyberinfrastructure Platform | Provides a blockchain-based platform to immutably store cryptographic hashes of data and metadata, ensuring integrity and enabling independent verification of research artifacts. |

| fMRIPrep [6] | Software Pipeline | A robust, standardized tool for preprocessing of fMRI data, helping to mitigate variability introduced at the initial data cleaning stages. |

| Human Connectome Project (HCP) Data [2] [5] | Reference Dataset | A high-quality, publicly available dataset acquired with advanced protocols, often used as a benchmark for testing pipeline performance and generalizability. |

| Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study Data [2] | Reference Dataset | A large-scale, longitudinal dataset with thousands of participants, essential for benchmarking effect sizes and testing pipelines on large, diverse samples. |

| UK Biobank (UKB) Data [2] | Reference Dataset | A very large-scale dataset from a general population, crucial for obtaining accurate estimates of small effect sizes and stress-testing pipeline generalizability. |

| Portrait Divergence (PDiv) [5] | Analysis Metric | An information-theoretic measure for quantifying the dissimilarity between whole-network topologies, used for evaluating test-retest reliability and sensitivity. |

| 3-(4-Tert-butylphenyl)-2-methyl-1-propene | 3-(4-Tert-butylphenyl)-2-methyl-1-propene, CAS:73566-44-6, MF:C14H20, MW:188.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3,5-Dimethoxy-3'-iodobenzophenone | 3,5-Dimethoxy-3'-iodobenzophenone, CAS:951892-16-3, MF:C15H13IO3, MW:368.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Software and Pipeline Selection

Q: What are the most common sources of analytical variability in fMRI studies? A: The primary sources include: 1) Choice of software package (SPM, FSL, AFNI); 2) Processing parameters such as spatial smoothing kernel size; 3) Modeling choices like HRF modeling and motion regressor inclusion; 4) Brain parcellation schemes for defining network nodes; and 5) Quality control procedures. One study found that across 70 teams analyzing the same data, results varied significantly due to these analytical choices [7] [8].

Q: Which fMRI meta-analysis software packages are most widely used? A: A 2025 survey of 820 papers found the following usage prevalence [9]:

Table: fMRI Meta-Analysis Software Usage (2019-2024)

| Software Package | Number of Papers | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| GingerALE | 407 | 49.6% |

| SDM-PSI | 225 | 27.4% |

| Neurosynth | 90 | 11.0% |

| Other | 131 | 16.0% |

Q: How does parcellation choice affect network analysis results? A: Parcellation selection significantly impacts derived network topology. Systematic evaluations reveal that the definition of network nodes (from discrete anatomically-defined regions to continuous, overlapping maps) creates vast variability in network organization and subsequent conclusions about brain function. Inappropriate parcellation choices can produce misleading results that are systematically biased rather than randomly distributed [5].

Quality Control and Error Management

Q: What are the best practices for quality control of automated brain parcellations? A: EAGLE-I (ENIGMA's Advanced Guide for Parcellation Error Identification) provides a systematic framework for visual QC. It classifies errors by: 1) Type (unconnected vs. connected); 2) Size (minor, intermediate, major); and 3) Directionality (overestimation vs. underestimation). Manual QC remains the gold standard, though automated alternatives using Euler numbers or MRIQC scores provide time-efficient alternatives [10] [11].

Q: How prevalent are parcellation errors in neuroimaging studies? A: Parcellation errors are common even in high-quality images without pathology. In clinical populations with conditions like traumatic brain injury, these errors are exacerbated by focal pathology affecting cortical regions. Despite this, many published studies using automated parcellation tools do not specify whether quality control was performed [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Pipeline Inconsistencies

Problem: Inconsistent results across research groups using the same dataset. Solution:

- Systematic pipeline documentation: Use standardized descriptors for pipelines (e.g., "software-FWHM-number of motion regressors-presence of HRF derivatives") [7]

- Containerization: Implement Docker/NeuroDocker images to fix software versions and environments [7] [8]

- Multi-pipeline evaluation: Test analysis robustness across multiple pipeline permutations rather than relying on a single pipeline

- Provenance tracking: Use platforms like NeuroAnalyst to maintain complete records of data transformations [12]

Parcellation Errors

Problem: Automated parcellation tools (FreeSurfer, FastSurfer) produce errors in brain region boundaries. Troubleshooting Steps:

- Systematic visual inspection: Load parcellation images and inspect each region sequentially [10]

- Error classification: Categorize errors by type, size, and directionality using standardized criteria

- Threshold determination: Establish clear thresholds for when errors warrant exclusion

- Use EAGLE-I error tracker: Utilize the standardized spreadsheet for consistent error recording [10]

Functional Connectivity Variability

Problem: Inconsistent functional network topologies from the same resting-state fMRI data. Solution Protocol:

- Systematic pipeline evaluation: Test combinations of parcellation, connectivity definition, and global signal processing [5]

- Multi-criterion validation: Assess pipelines based on motion robustness, test-retest reliability, and biological sensitivity

- Topological consistency: Use portrait divergence (PDiv) to measure network dissimilarity across all organizational scales

- Optimal pipeline selection: Identify pipelines satisfying reliability criteria across multiple datasets and time intervals

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Pipeline fMRI Analysis

Objective: To quantify analytical variability across different processing pipelines [7]

Materials:

- Raw fMRI data (e.g., HCP Young Adult dataset)

- Multiple software packages (SPM, FSL)

- High-performance computing environment

- Containerization platform (Docker/NeuroDocker)

Methodology:

- Select varying parameters:

- Software package (SPM12, FSL 6.0.3)

- Spatial smoothing (FWHM: 5mm, 8mm)

- Motion regressors (0, 6, or 24 parameters)

- HRF modeling (with/without derivatives)

Implement pipelines using workflow tools (Nipype 1.6.0)

Process all subjects through each pipeline permutation (e.g., 24 pipelines)

Extract statistical maps for individual and group-level analyses

Compare results across pipelines using spatial similarity metrics

Protocol 2: Analytical Flexibility Assessment

Objective: To evaluate how analytical choices affect research conclusions [13]

Materials:

- Standardized dataset (e.g., FRESH fNIRS data, NARPS fMRI data)

- Multiple research teams (30+ groups)

- Hypothesis testing framework

- Results collation system

Methodology:

- Provide identical datasets to multiple analysis teams

Define specific hypotheses with varying literature support

Allow independent analysis using teams' preferred pipelines

Collect results using standardized reporting forms

Quantify agreement across teams for each hypothesis

Identify pipeline features associated with divergent conclusions

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools for Neuroimaging Reliability Research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis Software | SPM12, FSL 6.0.3, AFNI | Statistical analysis of neuroimaging data |

| Meta-Analysis Tools | GingerALE 2.3.6+, SDM-PSI 6.22, NiMARE | Coordinate-based and image-based meta-analysis |

| Pipelines & Workflows | HCP Multi-Pipeline, NARPS pipelines | Standardized processing streams for reproducibility |

| Containerization | NeuroDocker, Neurodesk | Environment consistency across computational platforms |

| Quality Control | EAGLE-I, MRIQC, Qoala-T | Identification and classification of processing errors |

| Data Provenance | NeuroAnalyst, OpenNeuro | Tracking data transformations and ensuring reproducibility |

| Parcellation Tools | FreeSurfer 6.0, FastSurfer | Automated brain segmentation and region definition |

The Impact of Preprocessing Choices on Cortical Thickness Measures and Group Differences

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why do my cortical thickness results change drastically when I use different software tools?

Software tools (e.g., FreeSurfer, ANTS, CIVET) employ different algorithms for image normalization, registration, and segmentation, leading to systematic variability in cortical thickness measurements. Studies show software selection significantly affects both group-level neurobiological inference and individual-level prediction tasks. For instance, even different versions of the same software (FreeSurfer 5.1, 5.3, 6.0) can produce varying results due to algorithmic improvements and parameter changes [14].

Q2: Should I use cortical thickness or volume-based measures for Alzheimer's disease research?

Cortical thickness measures are generally recommended over volume-based measures for studying age-related changes or sex effects across large age ranges. While both perform similarly for diagnostic separation, volume-based measures are highly correlated with head size (a nuisance covariate), while thickness-based measures generally are not. Volume-based measures require statistical correction for head size, and the approach to this correction varies across studies, potentially introducing inconsistencies [15].

Q3: What are the most common errors in automated cortical parcellation, and how can I identify them?

Common parcellation errors include unconnected errors (affecting a single ROI) and connected errors (affecting multiple ROIs), which can be further classified by size (minor, intermediate, major) and directionality (overestimation or underestimation). These errors are particularly prevalent in clinical populations with pathological features. Use systematic QC protocols like EAGLE-I that provide clear visual examples and classification criteria to identify errors by type, size, and direction [10].

Q4: How does quality control procedure selection impact my cortical thickness analysis results?

Quality control procedures significantly affect task-driven neurobiological inference and individual-centric prediction tasks. The stringency of QC (e.g., no QC, lenient manual, stringent manual, automatic outlier detection) directly influences which subjects are included in analysis, potentially altering study conclusions. Inconsistent QC application across studies contributes to difficulties in replicating findings [14].

Q5: My FreeSurfer recon-all finished without errors, but the surfaces look wrong. What should I do?

Recon-all completion doesn't guarantee anatomical accuracy. Common issues include skull strip errors, segmentation errors, intensity normalization errors, pial surface misplacement, and topological defects. Use FreeView to visually inspect whether surfaces follow gray matter/white matter borders and whether subcortical segmentation follows intensity boundaries. Manual editing may be required to correct these issues [16].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Problem: Inaccurate Pial Surface Placement Symptoms: Red pial surfaces in FreeView appearing too deep or superficial relative to actual gray matter/CSF boundary. Solution: Edit the brainmask.mgz volume using FreeView to erase, fill, or clone voxels, then regenerate surfaces [16].

Problem: White Matter Segmentation Errors Symptoms: Holes in the wm.mgz volume visible in FreeView, often corresponding to surface dimples or inaccuracies. Solution: Manually edit the wm.mgz volume to fill segmentation gaps, ensuring continuous white matter representation [16].

Problem: Topological Defects Symptoms: Small surface tears or inaccuracies, particularly in posterior brain regions, often visible only upon close inspection. Solution: Use FreeSurfer's topological defect correction tools to identify and repair surface inaccuracies [16].

Problem: Skull Stripping Failures Symptoms: Brainmask.mgz includes non-brain tissue or excludes parts of cortex/cerebellum when compared to original T1.mgz. Solution: Manually edit brainmask.mgz to include excluded brain tissue or remove non-brain tissue, then reprocess [16].

Table 1: Impact of Preprocessing Choices on Cortical Thickness Analysis

| Preprocessing Factor | Impact Level | Specific Effects | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Tool [14] | High | • Significant effect on group-level and individual-level analyses• Different versions (FS 5.1, 5.3, 6.0) yield different results | • Consistent version use within study• Cross-software validation for critical findings |

| Parcellation Atlas [14] | Medium-High | • DKT, Destrieux, Glasser atlases produce varying thickness measures• Different anatomical boundaries and region definitions | • Atlas selection based on research question• Consistency across study participants |

| Quality Control [14] | High | • QC stringency affects sample size and results• Manual vs. automatic QC yield different subject inclusions | • Pre-specify QC protocol• Report QC criteria and exclusion rates |

| Global Signal Regression [5] | Context-Dependent | • Controversial preprocessing step for functional data• Systematically alters network topology | • Pipeline-specific recommendations• Consistent application across dataset |

| Metric | Diagnostic Separation | Head Size Correlation | Test-Retest Reliability | Clinical Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Thickness | Comparable to volume measures | Generally not correlated | Lower than volume measures | Correlates with Braak NFT stage |

| Volume Measures | Comparable to thickness measures | Highly correlated | Higher than thickness measures | Correlates with Braak NFT stage |

Experimental Protocols

Objective: Evaluate the impact of preprocessing pipelines on cortical thickness measures using open structural MRI datasets.

Materials:

- ABIDE dataset (573 controls, 539 ASD individuals from 16 international sites)

- Human Connectome Project validation data

- Processing tools: ANTS, CIVET, FreeSurfer (versions 5.1, 5.3, 6.0)

- Parcellations: Desikan-Killiany-Tourville, Destrieux, Glasser

- Quality control procedures: No QC, manual lenient, manual stringent, automatic low/high-dimensional

Methodology:

- Process structural MRI data through multiple pipeline combinations (5 software × 3 parcellations × 5 QC)

- Extract cortical thickness measures for each pipeline variation

- Perform statistical analyses divided by method type (task-free vs. task-driven) and inference objective (neurobiological group differences vs. individual prediction)

- Compare effect sizes and significance levels across pipelines

- Validate findings on independent HCP dataset

Objective: Systematically evaluate test-retest reliability and predictive validity of cortical thickness measures.

Materials:

- Multiple public datasets with repeated scans

- PhiPipe multimodal processing pipeline

- Comparison pipelines: DPARSF, PANDA

Methodology:

- Process T1-weighted images through multiple pipelines

- Calculate intra-class correlations (ICC) for test-retest reliability across four datasets

- Assess predictive validity by computing correlation between brain features and chronological age in three adult lifespan datasets

- Evaluate multivariate reliability and predictive validity

- Compare pipeline performance using standardized metrics

Workflow Diagrams

Cortical Thickness Pipeline Variability

Quality Control Decision Framework

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Cortical Thickness Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| FreeSurfer [14] [16] | Software Package | Automated cortical surface reconstruction and thickness measurement | Multiple versions (5.1, 5.3, 6.0) yield different results; recon-all requires visual QC |

| ANTS [14] [15] | Software Package | Advanced normalization tools for image registration | Recommended for AD signature measures with SPM12 segmentations |

| CIVET [14] | Software Package | Automated processing pipeline for structural MRI | Alternative to FreeSurfer with different algorithmic approaches |

| EAGLE-I [10] | QC Protocol | Standardized parcellation error identification and classification | Reduces inter-rater variability; provides clear error size thresholds |

| PhiPipe [17] | Multimodal Pipeline | Processing for T1-weighted, resting-state BOLD, and DWI MRI | Generates atlas-based brain features with reliability/validity metrics |

| fMRIPrep [18] [19] | Preprocessing Tool | Robust fMRI preprocessing pipeline | Requires quality control of input images; sensitive to memory issues |

| BIDS Standard [19] | Data Structure | Consistent organization of neuroimaging data and metadata | Facilitates reproducibility and pipeline standardization across studies |

The reliability of neuroimaging findings in Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) research is fundamentally tied to the data processing pipelines selected by investigators. This technical support center document examines how pipeline selection influences findings derived from the Autism Brain Imaging Data Exchange (ABIDE) dataset, a large-scale multi-site repository containing over 1,000 resting-state fMRI datasets from individuals with ASD and typical controls [20]. We provide troubleshooting guidance, methodological protocols, and analytical frameworks to help researchers navigate pipeline-related challenges and enhance the reproducibility of their neuroimaging findings.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent Classification Accuracy Across Sites

Issue: Machine learning models show significantly reduced accuracy when applied across different imaging sites compared to within-site performance.

Background: Multi-site data aggregation increases sample size but introduces scanner-induced technical variability that can mask true neural effects [21]. One study reported classification accuracy dropped substantially in leave-site-out validation compared to within-site performance [21].

Solutions:

- Implement Data Harmonization: Use ComBat harmonization to remove site-specific effects while preserving biological signals [21]. This technique employs empirical Bayes formulation to adjust for inter-site differences in data distributions.

- Cross-Validation Strategy: Adopt leave-site-out cross-validation where models are trained on data from all but one site and tested on the held-out site [21].

- Site Covariates: Include site as a covariate in statistical models when harmonization isn't feasible.

Problem 2: Head Motion Artifacts

Issue: Head movement during scanning introduces spurious correlations in functional connectivity measures.

Background: Even small head movements (mean framewise displacement >0.2mm) can significantly impact functional connectivity estimates [22].

Solutions:

- Apply Motion Filtering: Implement rigorous motion filtering (e.g., excluding volumes with FD >0.2mm) [22]. One study demonstrated this increased classification accuracy from 91% to 98.2% [22].

- Include Motion Parameters: Regress out 24 motion parameters obtained during realignment in preprocessing [23].

- Motion as Covariate: Include mean framewise displacement as a nuisance covariate in group-level analyses.

Problem 3: Low Classification Accuracy with Structural MRI

Issue: Structural T1-weighted images yield poor classification accuracy (~60%) for ASD identification.

Background: Early studies using volumetric features achieved limited success, potentially due to focusing on scalar estimates rather than shape information [24].

Solutions:

- Leverage Surface-Based Morphometry: Implement surface-based features that capture intrinsic geometry, such as multivariate morphometry statistics combining radial distance and tensor-based morphometry [24].

- Apply Sparse Coding: Use patch-based surface sparse coding and dictionary learning to reduce high-dimensional shape descriptors [24]. This approach achieved >80% accuracy using hippocampal surface features.

- Max-Pooling: Incorporate max-pooling operations after sparse coding to summarize feature representations [24].

Problem 4: Non-Reproducible Biomarkers

Issue: Identified neural biomarkers fail to replicate across studies or datasets.

Background: Small sample sizes, cohort heterogeneity, and pipeline variability contribute to non-reproducible associations [25].

Solutions:

- Prioritize Reproducibility in Model Selection: Use criteria that quantify association reproducibility alongside predictive performance during model selection [25].

- Regularized Linear Models: Employ regularized generalized linear models with reproducibility-focused validation rather than models selected purely for predictive accuracy [25].

- Independent Validation: Always validate biomarkers on held-out datasets not used during model development [23].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Which machine learning approach yields the highest ASD classification accuracy on ABIDE data?

A: Current evidence suggests deep learning approaches with proper preprocessing achieve the highest performance. One study using a Stacked Sparse Autoencoder with functional connectivity data and rigorous motion filtering (FD >0.2mm) reached 98.2% accuracy [22]. However, reproducibility should be prioritized over maximal accuracy for biomarker discovery [25].

Q: What is the recommended sample size for achieving reproducible ASD biomarkers?

A: While no definitive minimum exists, studies achieving reproducible associations typically use hundreds of participants. The ABIDE dataset provides 1,112 datasets across 17 sites [20], and studies leveraging this resource with appropriate harmonization have found more consistent results [21] [23].

Q: How can I determine whether my pipeline is capturing neural signals versus dataset-specific artifacts?

A: Implement the Remove And Retrain (ROAR) framework to benchmark interpretability methods [22]. Cross-validate findings across multiple preprocessing pipelines and validate against independent neuroscientific literature from genetic, neuroanatomical, and functional studies [22].

Q: Which functional connectivity measure is most sensitive to ASD differences?

A: Multiple measures contribute unique information. Whole-brain intrinsic functional connectivity, particularly interhemispheric and cortico-cortical connections, shows consistent group differences [20]. Additionally, regional metrics like degree centrality and fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations may reveal localized dysfunction [20].

Q: How does pipeline selection specifically impact the direction of findings (e.g., hyper- vs. hypoconnectivity)?

A: Pipeline choices significantly impact connectivity direction findings. One ABIDE analysis found that while both hyper- and hypoconnectivity were present, hypoconnectivity dominated particularly for cortico-cortical and interhemispheric connections [20]. The choice of noise regression strategies, motion correction, and global signal removal can flip the apparent direction of effects.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Deep Learning Classification with Functional Connectivity

Table 1: Key Parameters for Deep Learning Classification

| Component | Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Dataset | ABIDE I (408 ASD, 476 controls after FD filtering) | Large, multi-site sample [22] |

| Preprocessing | Mean FD filtering (>0.2 mm), bandpass filtering (0.01-0.1 Hz) | Reduces motion artifacts, isolates low-frequency fluctuations [22] |

| Model Architecture | Stacked Sparse Autoencoder + Softmax classifier | Captures hierarchical features of functional connectivity [22] |

| Interpretability Method | Integrated Gradients (validated via ROAR) | Provides reliable feature importance attribution [22] |

| Validation | Cross-validation across 3 preprocessing pipelines | Ensures findings not pipeline-specific [22] |

Protocol 2: Surface-Based Morphometry Classification

Table 2: Surface-Based Morphometry Pipeline

| Step | Method | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Feature Generation | Multivariate Morphometry Statistics (MMS) | Combines radial distance and tensor-based morphometry [24] |

| Dimension Reduction | Patch-based sparse coding & dictionary learning | Addresses high dimension, small sample size problem [24] |

| Feature Summarization | Max-pooling | Summarizes sparse codes across regions [24] |

| Classification | Ensemble classifiers with adaptive optimizers | Improves generalization performance [24] |

| Validation | Leave-site-out cross-validation | Tests generalizability across scanners [24] |

Protocol 3: Data Harmonization for Multi-Site Studies

Table 3: ComBat Harmonization Protocol

| Stage | Procedure | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Data Preparation | Extract connectivity matrices from all sites | Uniform input format |

| Parameter Estimation | Estimate site-specific parameters using empirical Bayes | Quantifies site effects |

| Harmonization | Adjust data using ComBat model | Removes site effects, preserves biological signals |

| Quality Control | Verify removal of site differences using visualization | Ensures successful harmonization |

| Downstream Analysis | Apply machine learning to harmonized data | Improved cross-site classification [21] |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Explainable AI Pipeline for ASD Classification

Diagram 2: Multi-Site Data Harmonization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Tools for ABIDE Data Analysis

| Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ComBat Harmonization | Removes site effects while preserving biological signals | Multi-site studies [21] |

| Stacked Sparse Autoencoder | Deep learning for functional connectivity feature extraction | High-accuracy classification [22] |

| Integrated Gradients | Explainable AI method for feature importance | Interpreting model decisions [22] |

| Multivariate Morphometry Statistics | Surface-based shape descriptors | Structural classification [24] |

| Remove And Retrain (ROAR) | Benchmarking framework for interpretability methods | Evaluating feature importance reliability [22] |

| Dual Regression ICA | Data-driven functional network identification | Resting-state network analysis [26] |

| PhiPipe | Multi-modal MRI processing pipeline | Integrated T1, fMRI, and DWI processing [17] |

| 4-(1-Bromoethyl)-1,1-dimethylcyclohexane | 4-(1-Bromoethyl)-1,1-dimethylcyclohexane|CAS 1541820-82-9 | 4-(1-Bromoethyl)-1,1-dimethylcyclohexane CAS 1541820-82-9. This brominated cycloalkane is for research use only. It is not for human or veterinary use. |

| 1-(Chloromethyl)naphthalene-2-carbonitrile | 1-(Chloromethyl)naphthalene-2-carbonitrile, CAS:1261626-83-8, MF:C12H8ClN, MW:201.65 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides

The Neuroimaging Analysis Replication and Prediction Study (NARPS) revealed that when 70 independent teams analyzed the same fMRI dataset, they reported strikingly different conclusions for 5 out of 9 pre-defined hypotheses about brain activity. This variability stemmed from "researcher degrees of freedom"—the many analytical choices researchers make throughout the processing pipeline [27] [28] [29].

Table: Key Factors Contributing to Analytical Variability in NARPS

| Factor | Impact on Results | Example from NARPS |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Smoothing | Strongest factor affecting outcomes; higher smoothness associated with greater likelihood of significant findings [28] | Smoothness of statistical maps varied widely (FWHM range: 2.50 - 21.28 mm) [28] |

| Software Package | Significant effect on reported results; FSL associated with higher likelihood of significant results vs. SPM [28] | Teams used different software: 23 SPM, 21 FSL, 7 AFNI, 13 Other [28] |

| Multiple Test Correction | Parametric methods led to higher detection rates than nonparametric methods [28] | 48 teams used parametric correction, 14 used nonparametric [28] |

| Model Specification | Critical for accurate interpretation; some teams mis-specified models leading to anticorrelated results [28] | For Hypotheses #1 & #3, 7 teams had results anticorrelated with the main cluster due to model issues [28] |

| Preprocessing Pipeline | No significant effect found from using standardized vs. custom preprocessing [28] | 48% of teams used fMRIprep preprocessed data, others used custom pipelines [28] |

Solution: A Framework for Robust Neuroimaging Analysis

To address the variability uncovered by NARPS, researchers should adopt a multi-framework approach that systematically accounts for analytical flexibility. The goal is not to eliminate all variability, but to understand and manage it to produce more generalizable findings [30].

Table: Solution Framework for Reliable Neuroimaging Analysis

| Strategy | Implementation | Expected Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Preregistration | Define analysis method before data collection [29] | Reduces "fishing" for significant results; increases methodological rigor |

| Multiverse Analysis | Systematically test multiple plausible analysis pipelines [30] | Maps the space of possible results; identifies robust findings |

| Pipeline Validation | Use reliability (ICC) and predictive validity (age correlation) metrics [17] | Ensures pipelines produce biologically meaningful and consistent results |

| Results Highlighting | Present all results while emphasizing key findings, instead of hiding subthreshold data [31] | Reduces selection bias; provides more complete information for meta-analyses |

| Multi-team Collaboration | Independent analysis by multiple teams with cross-evaluation [29] | Provides built-in replication; identifies methodological inconsistencies |

Experimental Protocols

Original NARPS Experimental Design

The NARPS project collected fMRI data from 108 participants during two versions of the mixed gambles task, which is used to study decision-making under risk [27].

Methodology Details:

- Participants: 108 healthy participants (equal indifference condition: n=54, 30 females, mean age=26.06±3.02 years; equal range condition: n=54, 30 females, mean age=25.04±3.99 years) [27]

- Task Design: Mixed gambles task with 50/50 chance of gaining or losing money [27]

- Imaging Parameters: 4 runs of fMRI, 453 volumes per run, TR=1 second [27]

- Behavioral Measures: Participants responded with "strongly accept," "weakly accept," "weakly reject," or "strongly reject" for each gamble [27]

- Incentive Structure: Real monetary consequences based on randomly selected trial [27]

Systematic Pipeline Evaluation Protocol

Recent advances recommend systematic evaluation of analysis pipelines using multiple criteria beyond simple test-retest reliability [5].

Validation Methodology:

- Reliability Assessment: Calculate Intraclass Correlation (ICC) between repeated scans [17]

- Predictive Validity: Measure correlation between brain features and chronological age [17]

- Multi-criteria Evaluation: Assess sensitivity to individual differences, clinical contrasts, and experimental manipulations [5]

- Portrait Divergence (PDiv): Information-theoretic measure of dissimilarity between network topologies that considers all scales of organization [5]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools for Reliable Neuroimaging Analysis

| Tool/Category | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| fMRIPrep | Standardized fMRI data preprocessing | Data preprocessing; used by 48% of NARPS teams [28] |

| PhiPipe | Multi-modal MRI processing pipeline | Generates brain features with assessed reliability and validity [17] |

| FSL, SPM, AFNI | Statistical analysis packages | Main software alternatives with different detection rates [28] |

| Krippendorff's α | Reliability analysis metric | Quantifies robustness of data across pipelines [32] |

| Portrait Divergence | Network topology comparison | Measures dissimilarity between functional connectomes [5] |

| FastSurfer | Deep learning-based segmentation | Automated processing of structural MRI; alternative to FreeSurfer [33] |

| DPARSF/PANDA | Single-modal processing pipelines | Comparison benchmarks for pipeline validation [17] |

| Ethyl 2-(benzylamino)-5-bromonicotinate | Ethyl 2-(benzylamino)-5-bromonicotinate|C15H15BrN2O2 | |

| 5-Bromo-4-isopropylthiazol-2-amine | 5-Bromo-4-isopropylthiazol-2-amine, CAS:1025700-49-5, MF:C6H9BrN2S, MW:221.12 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What was the most surprising finding from the NARPS project?

The most striking finding was that even when teams produced highly correlated statistical maps at intermediate analysis stages, they often reached different final conclusions about hypothesis support. This suggests that thresholding and region-of-interest specification decisions play a crucial role in creating variability [28].

Q: Should we always use standardized preprocessing pipelines like fMRIPrep?

Interestingly, NARPS found no significant effect on outcomes whether teams used standardized preprocessed data (fMRIPrep) versus custom preprocessing pipelines. This suggests that variability arises more from statistical modeling decisions than from preprocessing choices [28].

Q: How can we implement multiverse analysis in our lab without excessive computational cost?

Start by identifying the 3-5 analytical decisions most likely to impact your specific research question. Systematically vary these while holding other factors constant. This targeted approach makes multiverse analysis manageable while still capturing the most important sources of variability [30].

Q: What concrete steps can we take to improve the reliability of our findings?

Based on NARPS and subsequent research: (1) Preregister your analysis plan, (2) Use pipeline validation metrics (reliability and predictive validity), (3) Adopt a "highlighting" approach to results presentation instead of hiding subthreshold findings, and (4) Consider collaborative multi-team analysis for critical findings [31] [29] [30].

Q: Are some brain regions or hypotheses more susceptible to analytical variability?

Yes, NARPS found substantial variation across hypotheses. Only one hypothesis showed high consensus (84.3% significant findings), while three others showed consistent non-significant findings. The remaining five hypotheses showed substantial variability, with 21.4-37.1% of teams reporting significant results [28].

Next-Generation Neuroimaging Pipelines: Deep Learning and Standardization for Scalable Analysis

Troubleshooting Guides

System Requirements and Installation Issues

Q1: What are the minimum system requirements for running DeepPrep, and why is my GPU not being detected?

A: DeepPrep leverages deep learning models for acceleration, making appropriate hardware crucial. The following table summarizes the key requirements:

Table: DeepPrep System Requirements and GPU Troubleshooting

| Component | Minimum Requirement | Recommended Requirement | Troubleshooting Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPU | NVIDIA GPU with Compute Capability ≥ 3.5 | NVIDIA GPU with ≥ 8GB VRAM | Use --device auto to auto-detect or --device 0 to specify the first GPU. For CPU-only mode, use --device cpu. [34] |

| CPU | Multi-core processor | 10+ CPUs | Specify with --cpus 10. [34] |

| Memory | 8 GB RAM | 20 GB RAM | Specify with --memory 20. [34] |

| Software | Docker or Singularity | Latest Docker/Singularity | Ensure --gpus all is passed in Docker or --nv in Singularity. [34] |

| License | - | Valid FreeSurfer license | Pass the license file via -v <fs_license_file>:/fs_license.txt. [34] |

A common issue is incorrect GPU pass-through in containers. For a Docker installation, the correct command must include --gpus all [34]. For Singularity, the --nv flag is required to enable GPU support [34].

Q2: FastSurfer fails during the surface reconstruction phase (recon-surf). What could be the cause?

A: The recon-surf pipeline has specific dependencies on the output of the segmentation step. The issue often lies in the input data or intermediate files.

- Incorrect Input Image Resolution: FastSurfer expects isotropic voxels between 0.7mm and 1.0mm. Verify your input data conforms to this requirement. You can use the

--vox_sizeflag to specify high-resolution behavior. [35] - Failed Volumetric Segmentation: The surface pipeline relies on the high-quality brain segmentation generated by

FastSurferCNN. First, check thesegoutput for obvious errors. Run with--seg_onlyto isolate the segmentation step and visually QC theaparc.DKTatlas+aseg.mgzfile. [35] - Missing FreeSurfer Environment for Downstream Modules: Some downstream analyses, like hippocampal subfield segmentation, require a working installation of FreeSurfer 7.3.2. While FastSurfer creates compatible files, you must source FreeSurfer to run these additional modules. [35]

Runtime Errors and Performance

Q3: The pipeline is running slower than advertised. How can I optimize its performance?

A: Performance depends heavily on your computational resources and data size. The quantitative benchmarks below can help you set realistic expectations.

Table: Performance Benchmarks for DeepPrep and FastSurfer

| Pipeline / Module | Runtime (CPU/GPU) | Speed-up vs. Traditional | Validation Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepPrep (End-to-End) | ~31.6 ± 2.4 min (GPU) | 10.1x faster than fMRIPrep | Processing a single subject from the UK Biobank dataset. [36] |

| DeepPrep (Batch) | ~8.8 min/subject (GPU) | 10.4x more efficient than fMRIPrep | Processing 1,146 subjects per week. [36] |

| FastSurferCNN (Segmentation) | < 1 min (GPU) | Drastic speed-up over FreeSurfer | Whole-brain segmentation into 95 classes. [37] [38] |

| FastSurfer (recon-surf) | ~60 min (CPU) | Significant speed-up over FreeSurfer | Cortical surface reconstruction and thickness analysis. [35] [38] |

| FastCSR (in DeepPrep) | < 5 min | ~47x faster than FreeSurfer | Cortical surface reconstruction from T1-weighted images. [39] |

To optimize performance:

- For DeepPrep: Use the

--cpusand--memoryflags to allocate sufficient resources. For large datasets, leverage its batch-processing capability, which is optimized by the Nextflow workflow manager. [36] [34] - For FastSurfer: Ensure you are using a GPU for the

FastSurferCNNsegmentation step. Therecon-surfpart runs on CPU, and its speed is dependent on single-core performance. [35]

Q4: The pipeline failed when processing a clinical subject with a brain lesion. How can I improve robustness?

A: This is a critical test of pipeline robustness. Deep learning-based pipelines like DeepPrep and FastSurfer have demonstrated superior performance in such scenarios.

- DeepPrep's Robustness: In a test of 53 challenging clinical samples (e.g., with tumors or strokes), DeepPrep achieved a 100% completion rate, with 58.5% being accurately preprocessed. This was significantly higher than fMRIPrep's 69.8% completion and 30.2% accuracy rates. [36] The deep learning modules (FastSurferCNN, FastCSR) are more resilient to anatomical distortions that cause conventional algorithms to fail in skull stripping, surface reconstruction, or registration. [36]

- FastCSR Performance: The FastCSR model, used within DeepPrep, has been successfully applied to reconstruct cortical surfaces for stroke patients with severe cerebral hemorrhage and resulting brain distortion. [39]

- Recommendation: Always perform visual quality checks on the outputs, especially for clinical data. While these pipelines are robust, no automated tool is infallible. [35]

Output and Quality Control

Q5: How can I validate the accuracy of the volumetric segmentations produced by FastSurfer?

A: In the context of reliability assessment, it is essential to verify that the accelerated pipelines do not compromise accuracy. The following experimental protocol can be used for validation.

Validation Protocol: Segmentation Accuracy

- Data Preparation: Utilize a publicly available dataset with manual annotations, such as the Mindboggle-101 dataset [36]. Alternatively, use test-retest data like the OASIS dataset to assess reliability. [38]

- Metric Calculation:

- Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC): Measures the spatial overlap between the automated segmentation and the manual ground truth. A value of 1 indicates perfect overlap. FastSurferCNN has been shown to outperform other deep learning architectures significantly on this metric. [38]

- Hausdorff Distance: Measures the largest distance between the boundaries of two segmentations, indicating the worst-case error. [38]

- Comparison: Compare the results against traditional pipelines (FreeSurfer) and other deep learning methods. Studies show FastSurfer provides high accuracy that closely mimics FreeSurfer's anatomical segmentation and even outperforms it in some comparisons to manual labels. [37] [38]

Q6: The cortical surface parcellation looks misaligned. Is this a surface reconstruction or registration error?

A: This could be related to either step. The following workflow diagram illustrates the sequence of steps in these pipelines, helping to isolate the problem.

Diagram: Simplified Neuroimaging Pipeline Workflow

- Surface Reconstruction (FastCSR): This step creates the white and pial surface meshes. If the underlying segmentation is incorrect, the surface will be generated in the wrong location. Check the intermediate surfaces for topological correctness. [39]

- Surface Registration (SUGAR): This step maps a standard atlas (e.g., the DKT atlas) from a template sphere to the individual subject's sphere. Misalignment here is a registration error. DeepPrep uses the Spherical Ultrafast Graph Attention Registration (SUGAR) framework for this step, which is a deep-learning-based method designed to be fast and accurate. [36] [40] Ensure that this module completed successfully by checking the pipeline logs.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Can these pipelines be used for high-resolution (e.g., 7T) MRI data?

A: Support is evolving. FastSurfer is "transitioning to sub-millimeter resolution support," and its core segmentation module, FastSurferVINN, supports images up to 0.7mm, with experimental support beyond that. [35] DeepPrep lists support for high-resolution 7T images as an "upcoming improvement" on its development roadmap. [40]

Q: What output formats can I expect from DeepPrep?

A: DeepPrep is a BIDS-App and produces standardized outputs. For functional MRI, it can generate outputs in NIFTI format for volumetric data and CIFTI format for surface-based data (using the --bold_cifti flag). It also supports output in standard surface spaces like fsaverage and fsnative. [34]

Q: Are these pipelines suitable for drug development research?

A: Yes, their speed, scalability, and demonstrated sensitivity to group differences make them highly suitable. FastSurfer has been validated to sensitively detect known cortical thickness and subcortical volume differences between dementia and control groups, which is directly relevant to clinical trials in neurodegenerative disease. [38] The ability to rapidly process large cohorts is essential for biomarker discovery and treatment effect monitoring.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This table details the key computational "reagents" and their functions in the DeepPrep and FastSurfer ecosystems.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Accelerated Neuroimaging

| Tool / Module | Function | Replaces Traditional Step | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| FastSurferCNN [35] [38] | Whole-brain segmentation into 95 classes. | FreeSurfer's recon-all volumetric stream (hours). |

GPU-based, <1 min runtime. Uses multi-view 2D CNNs with competition. |

| recon-surf [35] [38] | Cortical surface reconstruction, mapping of labels, thickness analysis. | FreeSurfer's recon-all surface stream (hours). |

~1 hour runtime. Uses spectral spherical embedding. |

| FastCSR [36] [39] | Cortical surface reconstruction using implicit level-set representations. | FreeSurfer's surface reconstruction. | <5 min runtime. Robust to image artifacts. |

| SUGAR [36] | Spherical registration of cortical surfaces. | FreeSurfer's spherical registration (e.g., sphere.reg). |

Deep-learning-based graph attention framework. |

| SynthMorph [36] | Volumetric spatial normalization (image registration). | ANTs or FSL registration. | Label-free learning, robust to contrast changes. |

| Nextflow [40] [36] | Workflow manager for scalable, portable, and reproducible data processing. | Manual scripting or linear processing. | Manages complex dependencies and parallelization on HPC/cloud. |

| 6-Chloro-N-isopropyl-2-pyridinamine | 6-Chloro-N-isopropyl-2-pyridinamine, CAS:1220034-36-5, MF:C8H11ClN2, MW:170.64 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 3-(Perfluoro-n-octyl)propenoxide | 3-(Perfluoro-n-octyl)propenoxide, CAS:38565-53-6, MF:C11H5F17O, MW:476.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

FAQs: Computational Efficiency and Neuroimaging Pipelines

1. What are the most common computational bottlenecks when working with large-scale neuroimaging datasets like the UK Biobank? Common bottlenecks include extensive processing times for pipeline steps, high computational resource demands (memory/CPU), and inefficient scaling with sample size. Benchmarking studies show that different machine learning algorithms have vastly different computational requirements, and some implementations become impracticable at very large sample sizes [41]. Managing these resources efficiently is critical for timely analysis.

2. How does the choice of a neuroimaging data-processing pipeline affect the reliability and efficiency of my results? The choice of pipeline systematically impacts both your results and computational load. Evaluations of fMRI data-processing pipelines reveal "vast and systematic variability" in their outcomes and suitability. An inappropriate pipeline can produce misleading, yet systematically replicable, results. Optimal pipelines, however, consistently minimize spurious test-retest discrepancies while remaining sensitive to biological effects, and do so efficiently across different datasets [5].

3. My processing pipeline is taking too long. What are the first steps I should take to troubleshoot this? Begin by isolating the issue. Identify which specific pipeline step is consuming the most time and resources. Check your computational environment: ensure you are leveraging available high-performance computing or cloud resources like the UK Biobank Research Analysis Platform (UKB-RAP), which provides scalable cloud computing [42]. Furthermore, consult benchmarking resources to see if a more efficient algorithm or model is available for your specific data properties [41].

4. What metrics should I use to evaluate the computational efficiency of a pipeline beyond pure processing time? A comprehensive evaluation should consider several factors: total wall-clock time, CPU hours, memory usage, and how these scale with increasing sample size (e.g., from n=5,000 to n=250,000). It's also crucial to balance efficiency with performance, ensuring that speed gains do not come at the cost of discriminatory power or reliability [41] [5].

5. Are complex models like Deep Learning always better for large-scale datasets like UK Biobank? Not always. Benchmarking on UK Biobank data shows that while complex frameworks can be favored with large numbers of observations and simple predictor matrices, (penalised) COX Proportional Hazards models demonstrate very robust discriminative performance and are a highly effective, scalable platform for risk modeling. The optimal model choice depends on sample size, endpoint frequency, and predictor matrix properties [41].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Extended Processing Times

Problem: Your neuroimaging pipeline is running significantly longer than expected.

Solution: Follow a systematic approach to isolate and address the bottleneck.

- Profile Your Pipeline: Instrument your code to log the time and resource consumption of each major processing step (e.g., T1-weighted segmentation, functional connectivity matrix calculation). This will pinpoint the slowest module.

- Check Resource Allocation: Verify that your job is efficiently using the available CPUs and memory. Under-provisioning can cause queuing and slow performance. On cloud platforms like the UKB-RAP, ensure you have selected an appropriate instance type [42].

- Consult Benchmarks: Refer to existing benchmarking studies. For example, research on the UK Biobank identifies specific scenarios where simpler linear models scale more effectively than complex ones without a significant loss in discriminative performance, offering a potential path to acceleration [41].

- Optimize or Replace the Bottleneck:

- If the bottleneck is a specific atomic software (e.g., a particular segmentation algorithm), investigate if there are faster, validated alternatives.

- Consider if the step can be parallelized across multiple cores or nodes.

- For machine learning models, evaluate if a less computationally intensive model is suitable for your data [41].

Guide 2: Addressing Poor Pipeline Reliability

Problem: Your pipeline yields inconsistent results when run on the same subject at different times (low test-retest reliability).

Solution: A lack of reliability can stem from the pipeline's construction itself.

- Validate Pipeline Components: Systematically evaluate the test-retest reliability of the brain features generated by your pipeline. Use metrics like Intra-class Correlation (ICC) across repeated scans, as demonstrated in pipeline validation studies [17].

- Re-evaluate Pipeline Choices: The specific combination of parcellation, connectivity definition, and global signal regression (GSR) can dramatically impact reliability. Systematic evaluations of fMRI pipelines have identified specific combinations that consistently minimize spurious test-retest discrepancies [5].

- Check for Motion Confounds: Ensure your preprocessing adequately addresses head motion, a major source of spurious variance. The reliability of a pipeline is often judged by its ability to minimize motion confounds [5].

- Adopt a Pre-validated Optimal Pipeline: Instead of building a custom pipeline from scratch, consider adopting a pipeline that has been systematically validated for reliability and predictive validity across multiple datasets [17] [5].

Quantitative Benchmarking Data

Table 1: Benchmarking of Machine Learning Algorithms on UK Biobank-Scale Data

Findings from a comprehensive benchmarking study of risk prediction models, highlighting the trade-off between performance and computational efficiency [41].

| Model / Algorithm Type | Key Performance Findings | Computational & Scaling Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| (Penalised) COX Proportional Hazards | "Very robust performance" across heterogeneous endpoints and predictor matrices. | Highly effective and scalable; observed as a computationally efficient platform for large-scale modeling. |

| Deep Learning (DL) Models | Can be favored in scenarios with large observations and relatively simple predictor matrices. | "Vastly different" and often impracticable requirements; scaling is highly dependent on implementation. |

| Non-linear Machine Learning Models | Performance is highly dependent on endpoint frequency and predictor matrix properties. | Generally less scalable than linear models; computational requirements can be a limiting factor. |

Table 2: Evaluation Criteria for fMRI Network Construction Pipelines

Summary of the multi-criteria framework used to systematically evaluate 768 fMRI processing pipelines, underscoring that efficiency is not just about speed but also outcome quality [5].

| Criterion | Description | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Test-Retest Reliability | Minimizes spurious discrepancies in network topology from repeated scans of the same individual. | Fundamental for trusting that results reflect true biology rather than noise. |

| Sensitivity to Individual Differences | Ability to detect meaningful inter-subject variability in brain network organization. | Crucial for studies linking brain function to behavior, traits, or genetics. |

| Sensitivity to Experimental Effects | Ability to detect changes in brain networks due to clinical conditions or interventions (e.g., anesthesia). | Essential for making valid inferences in experimental or clinical studies. |

| Generalizability | Consistent performance across different datasets, scanning parameters, and preprocessing methods. | Ensures that findings and pipelines are robust and not specific to a single dataset. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Computational Efficiency of Survival Models

This protocol is derived from the large-scale benchmarking study performed on the UK Biobank [41].

Objective: To compare the discriminative performance and computational requirements of eight distinct survival task implementations on large-scale datasets.

Methodology:

- Data Source: Utilize a large-scale prospective cohort study (e.g., UK Biobank).

- Algorithms: Select a diverse set of machine learning algorithms, ranging from linear models (e.g., penalized COX Proportional Hazards) to deep learning models.

- Experimental Design:

- Scaling Analysis: Systematically vary the sample size (e.g., from n=5,000 to n=250,000 individuals) to assess how processing time and memory usage scale.

- Performance Assessment: Evaluate models based on discrimination metrics (e.g., C-index) across endpoints with different frequencies.

- Resource Tracking: Record wall-clock time, CPU hours, and memory consumption for each model and sample size.

- Analysis: Identify scenarios (defined by sample size, endpoint frequency, and predictor matrix) that favor specific model types. Report on implementations that are impracticable at scale and provide alternative solutions.

Protocol 2: Systematic Evaluation of fMRI Processing Pipelines

This protocol is based on the multi-dataset evaluation of 768 pipelines for functional connectomics [5].

Objective: To identify fMRI data-processing pipelines that yield reliable, biologically relevant brain network topologies while being computationally efficient.

Methodology:

- Pipeline Construction: Systematically combine different options at key analysis steps:

- Global Signal Regression: With vs. without GSR.

- Brain Parcellation: Use different atlases (anatomical, functional, multimodal) with varying numbers of nodes (e.g., 100, 200, 300-400).

- Edge Definition: Pearson correlation vs. mutual information.

- Edge Filtering: Apply different methods (e.g., proportional thresholding, minimum weight, data-driven methods) to produce binary or weighted networks.

- Evaluation Criteria: Assess each pipeline on:

- Reliability: Use Portrait Divergence (PDiv) to quantify test-retest topological dissimilarity within the same individual across short- and long-term intervals.

- Biological Sensitivity: Assess sensitivity to individual differences and experimental effects (e.g., pharmacological intervention).

- Confound Resistance: Evaluate the minimization of motion-related confounds.

- Validation: Require that optimal pipelines satisfy all criteria across multiple independent datasets to ensure generalizability.

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

DOT Script for Neuroimaging Pipeline Evaluation

DOT Script for Computational Benchmarking Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| UK Biobank Research Analysis Platform (UKB-RAP) | A secure, cloud-based platform providing centralized access to UK Biobank data and integrated tools (JupyterLab, RStudio, Apache Spark) for efficient, scalable analysis without local data transfer [42]. |

| PhiPipe | A multi-modal MRI processing pipeline for T1-weighted, resting-state BOLD, and diffusion-weighted data. It generates standard brain features and has published reliability and predictive validity metrics [17]. |

| Linear Survival Models (e.g., COX-PH) | A highly effective and scalable modeling platform for risk prediction on large datasets, often providing robust performance comparable to more complex models [41]. |

| Portrait Divergence (PDiv) | An information-theoretic measure used to quantify the dissimilarity between entire network topologies, crucial for evaluating pipeline test-retest reliability beyond single metrics [5]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) / Cloud Credits | Financial support, such as AWS credits offered via UKB-RAP, to offset the costs of large-scale computational power and storage required for processing massive datasets [42]. |

| O,O,O-Triphenyl phosphorothioate | O,O,O-Triphenyl phosphorothioate, CAS:597-82-0, MF:C18H15O3PS, MW:342.3 g/mol |

| 3-[(Dimethylamino)methyl]phenol | 3-[(Dimethylamino)methyl]phenol, CAS:60760-04-5, MF:C9H13NO, MW:151.21 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Segmentation Accuracy on Clinical MRI Data

Problem: The model trained on public datasets (e.g., ISLES, BraTS) shows poor performance (low Dice score) when applied to hospital data.

Solution: Implement transfer learning and multimodal fusion.

- Root Cause: Scanner variability, different imaging protocols, and population differences between public and private hospital datasets can degrade performance [43].

- Steps for Resolution:

- Utilize Transfer Learning: Initialize your model with weights pre-trained on a larger, diverse neuroimaging dataset before fine-tuning on your target data. For instance, pre-training on the BraTS (brain tumor) dataset has been shown to improve performance on ischemic stroke segmentation tasks [43].

- Adopt a Robust Baseline: Use a framework like nnU-Net, which automatically configures itself based on dataset properties and is known for its robustness in medical image segmentation challenges [43].

- Employ Multimodal Fusion: Leverage multiple MRI sequences. Two effective methods are:

- Joint Training: Train a single model on multiple modalities (e.g., DWI and ADC) simultaneously, then perform inference using the most reliable single modality (e.g., DWI only) [43].

- Channel-wise Training: Concatenate different modalities (e.g., DWI and ADC) as multi-channel inputs to the model [43].

- Ensemble Models: Combine the predictions from different multimodal approaches (e.g., joint training and channel-wise training) to improve generalization and robustness [43].

Handling Small and Imbalanced Neuroimaging Cohorts

Problem: Machine learning models perform poorly or overfit when trained on a small number of subjects, which is common in studies of rare neurological diseases.

Solution: Optimize the ML pipeline and focus on data-centric strategies.

- Root Cause: Limited data fails to capture the full heterogeneity of a disease, making it difficult for models to learn generalizable patterns [44].

- Steps for Resolution:

- Apply Subject-wise Normalization: Normalize features per subject to reduce inter-subject variability, which has been shown to improve classification outcomes in small-cohort studies [44].

- Re-evaluate Pipeline Complexity: Be cautious with aggressive feature selection and dimensionality reduction, as these can provide limited utility or even remove important biomarkers when data is scarce [44].

- Manage Hyperparameter Tuning Expectations: Understand that hyperparameter optimization may yield only marginal gains. Focus effort on other strategies [44].

- Prioritize Data Enrichment: The most effective strategy is often to progressively expand the cohort size, integrate additional imaging modalities, or maximize information extraction from existing datasets [44].

Inadequate Evaluation Beyond Voxel-Wise Metrics

Problem: A model achieves a high Dice score but fails to accurately identify individual lesion burdens, which is critical for assessing disease severity.

Solution: Supplement voxel-wise metrics with lesion-wise evaluation metrics.

- Root Cause: The Dice coefficient measures overall voxel overlap but can be misleading. A model can score highly by correctly segmenting one large lesion while missing several smaller ones [43].

- Steps for Resolution:

- Track Lesion-wise F1 Score: This metric evaluates the accuracy of detecting individual lesion instances, which is more clinically relevant for assessing disease burden [43].

- Monitor Lesion Count Difference: Calculate the absolute difference between the number of true lesions and the number of predicted lesions [43].

- Report Volume Difference: Quantify the difference in the total volume of segmented lesions versus the ground truth [43].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my model's performance excellent on public challenge data but poor on our internal hospital data? A1: This is typically due to the generalization gap. Public datasets are often pre-processed (e.g., skull-stripped, registered to a template) and acquired under specific protocols. Internal clinical data contains more variability. To bridge this gap, use transfer learning from public data, ensure your training incorporates data augmentation, and employ multimodal approaches that enhance robustness [43].

Q2: For ischemic stroke segmentation, which MRI modalities are most crucial? A2: Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI) and the Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) map are among the most important. DWI is highly sensitive for detecting acute ischemia, while ADC provides quantitative information that can be more robust to observer variability. Using both in a multimodal framework has been shown to significantly improve segmentation performance [43].

Q3: What is a practical baseline model for a new medical image segmentation task? A3: The nnU-Net framework is highly recommended as a robust baseline. It automatically handles key design choices like patch size, data normalization, and augmentation based on your dataset properties, and it has been a top performer in numerous medical segmentation challenges, including ISLES [43].

Q4: How can I improve model performance when I cannot collect more patient data? A4: Focus on pipeline optimization and data enrichment:

- Use transfer learning from a related task (e.g., brain tumor to stroke) [43].

- Integrate all available multimodal data (e.g., T1, T2, FLAIR, DWI) rather than relying on a single modality [44].

- Apply subject-wise feature normalization [44].

- Be strategic with data augmentation to artificially increase dataset size and variability.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Multimodal Ensemble for Stroke Segmentation

This protocol is adapted from state-of-the-art methods that ranked highly in the ISLES'22 challenge [43].

Data Preprocessing:

- Use clinical-grade T1-weighted, T2-weighted, FLAIR, DWI, and ADC maps if available.

- For DWI, generate the corresponding ADC map.

- Perform coregistration of all modalities if they are not natively aligned.

- Consider skull-stripping for public data, but note that for clinical application, models should be robust to its absence.

Transfer Learning:

- Obtain a model pre-trained on a large, annotated neuroimaging dataset such as BraTS'21 (for brain tumors).

- This pre-trained model serves as a feature extractor, providing a better initialization than random weights.

Multimodal Model Training:

- Path A (Joint Training): Train a single model (e.g., nnU-Net) on both DWI and ADC modalities. For inference, use only the DWI modality.

- Path B (Channel-wise Training): Train a model using concatenated DWI and ADC images as a two-channel input.

- Use a 5-fold cross-validation strategy on your training data to ensure model stability.

Inference and Ensembling:

- Run inference using both trained models (Path A and Path B) on the test data.

- Combine the segmentation masks from both models via a simple averaging or majority voting scheme to produce the final ensemble prediction.

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes the performance of a robust ensemble method across multiple datasets, demonstrating its generalizability [43].

Table 1: Segmentation Performance Across Multi-Center Datasets

| Dataset | Description | Sample Size | Dice Coefficient (%) | Lesion-wise F1 Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISLES'22 | Public challenge dataset (multi-center) | 150 test scans | 78.69 | 82.46 |

| AMC I | External hospital dataset I | Not Specified | 60.35 | 68.30 |

| AMC II | External hospital dataset II | Not Specified | 74.12 | 67.53 |

Note: The AMC I and II datasets represent realistic clinical settings, often without extensive pre-processing like brain extraction, leading to a more challenging environment and lower metrics than the public challenge data.

Table 2: WCAG Color Contrast Ratios for Data Visualization

| Element Type | Minimum Ratio (AA) | Enhanced Ratio (AAA) | Example Use in Diagrams |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Body Text | 4.5 : 1 | 7 : 1 | Node text, diagram labels |

| Large Scale Text | 3 : 1 | 4.5 : 1 | Section headers, titles |

| UI Components / Graphics | 3 : 1 | Not Defined | Arrows, diagram symbols |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: Neuroimaging Analysis Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for a Robust Neuroimaging Pipeline

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| nnU-Net Framework | A self-configuring deep learning framework that serves as a powerful and robust baseline for medical image segmentation tasks, automatically adapting to dataset properties [43]. |