Ensuring Reliability in Brain Imaging: From Scanner to Statistical Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive framework for assessing the reliability of brain imaging methodologies, crucial for researchers and drug development professionals.

Ensuring Reliability in Brain Imaging: From Scanner to Statistical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for assessing the reliability of brain imaging methodologies, crucial for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores foundational concepts of reliability and reproducibility in neuroimaging, examines both traditional and deep learning-based analytical methods, identifies key sources of error with optimization strategies, and presents comparative validation approaches for different tools and sequences. By synthesizing current evidence and best practices, this review aims to enhance the rigor and reproducibility of structural MRI analyses in both research and clinical trial contexts.

Understanding Brain Imaging Reliability: Core Concepts and Reproducibility Challenges

In the field of quantitative brain imaging, the derivation of robust and reproducible biomarkers is paramount for both research and clinical applications, such as tracking neurodegenerative disease progression or assessing treatment efficacy. The reliability of these measurements, whether obtained from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or other automated segmentation software, is fundamentally assessed through specific statistical metrics. This guide provides an objective comparison of two predominant reliability metrics—the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) and the Coefficient of Variation (CV)—framed within the context of brain imaging reliability assessment. Furthermore, it explores the concept of significant bits in the context of image standardization, which bridges the gap between metric evaluation and technical implementation. Supporting experimental data from published studies are synthesized to illustrate their application and performance.

Conceptual Foundations and Mathematical Definitions

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC)

The ICC is a measure of reliability that describes how strongly units in the same group resemble each other. In the context of reliability analysis, it is used to assess the consistency or reproducibility of quantitative measurements made by different observers or devices measuring the same quantity [1].

In a random effects model framework, the ICC is defined as the ratio of the between-subject variance to the total variance. The one-way random effects model is often expressed as: ( Y{ij} = \mu + \alphaj + \epsilon{ij} ) where ( Y{ij} ) is the i-th observation in the j-th subject, ( \mu ) is the overall mean, ( \alphaj ) are the random subject effects with variance ( \sigma{\alpha}^2 ), and ( \epsilon{ij} ) are the error terms with variance ( \sigma{\epsilon}^2 ). The population ICC is then [1]: ( \text{ICC} = \frac{\sigma{\alpha}^2}{\sigma{\alpha}^2 + \sigma_{\epsilon}^2} )

A critical consideration is that several forms of ICC exist. Shrout and Fleiss, for example, described multiple ICC forms applicable to different experimental designs [2]. The selection of the appropriate ICC form (e.g., based on "model," "type," and "definition") must be guided by the research design, specifically whether the same or different raters assess all subjects, and whether absolute agreement or consistency is of interest [3]. Koo and Li (2016) provide a widely cited guideline suggesting that ICC values less than 0.5 indicate poor reliability, values between 0.5 and 0.75 indicate moderate reliability, values between 0.75 and 0.9 indicate good reliability, and values greater than 0.90 indicate excellent reliability [3].

Coefficient of Variation (CV)

The Coefficient of Variation (CV) is a standardized measure of dispersion, defined as the ratio of the standard deviation ( \sigma ) to the mean ( \mu ), often expressed as a percentage [4]: ( \text{CV} = \frac{\sigma}{\mu} \times 100\% )

In reliability assessment, particularly for laboratory assays or measurement devices, the within-subject coefficient of variation (WSCV) is often more appropriate than the typical CV. The WSCV is defined as ( \theta = \sigmae / \mu ), where ( \sigmae ) is the within-subject standard deviation. This metric specifically determines the degree of closeness of repeated measurements taken on the same subject under the same conditions [5]. A key advantage of the CV is that it is a dimensionless number, allowing for comparison between data sets with different units or widely different means [4]. However, a notable disadvantage is that when the mean value is close to zero, the coefficient of variation can approach infinity and become highly sensitive to small changes in the mean [4].

Relationship to Significant Bits and Image Standardization

While "significant bits" is not a standard statistical metric like ICC or CV, the concept relates directly to image pre-processing and standardization, which underpins the reliability of any subsequent quantitative feature extraction. In MRI-based radiomics, the lack of standardized intensity values across machines and protocols is a major challenge [6]. The process of grey-level discretization, which clusters similar intensity levels into a fixed number of bins (bits), is a critical pre-processing step that influences the stability of second-order texture features [6]. Using a fixed bin number (e.g., 32 bins) is a form of relative discretization that helps manage the bit depth of the analyzed data, thereby contributing to more reliable and reproducible radiomics features by reducing the impact of noise and non-biological intensity variations.

Comparative Analysis of Reliability Metrics

Table 1: Comparison of Reliability Metrics in Brain Imaging

| Metric | Primary Use Case | Interpretation Range | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICC | Assessing reliability/agreement between raters or devices. | 0 to 1 (or -1 to 1 for some forms). Values >0.9 indicate excellent reliability [3]. | Accounts for both within- and between-subject variance; can handle multiple raters [1]. | Multiple forms exist, requiring careful selection [3]; can be influenced by population heterogeneity [5]. |

| CV / WSCV | Quantifying reproducibility of a single instrument or within-subject variability. | 0% to infinity. Smaller values indicate better reproducibility [5]. | Dimensionless, allows comparison across different measures [4]; intuitive interpretation. | Sensitive to small mean values [4]; does not directly assess agreement between raters. |

The choice between ICC and WSCV depends on the specific research question. The ICC is particularly useful when the goal is to differentiate among subjects, as a larger heterogeneity among subjects (with a constant or smaller random error) increases the ICC [5]. In contrast, the WSCV is a pure measure of reproducibility, determining the degree of closeness of repeated measurements on the same subject, irrespective of between-subject variation [5]. This makes the WSCV particularly valuable for assessing the intrinsic performance of a measurement device.

Experimental Protocols for Reliability Assessment

Test-Retest Dataset Acquisition for Brain MRI

A foundational step for assessing the reliability of brain imaging metrics is the creation of a robust test-retest dataset. A standard protocol involves acquiring multiple scans from the same subjects across different sessions.

Methodology from a Publicly Available Dataset [7]:

- Subjects: 3 healthy subjects.

- Scanning Sessions: 20 sessions per subject over 31 days.

- Scans per Session: 2 T1-weighted scans per session, with subject repositioning between scans.

- Scanner and Protocol: 3T GE MR750 scanner using the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) T1-weighted imaging protocol (accelerated sagittal 3D IR-SPGR).

- Data Processing: All 120 3D volumes were processed using FreeSurfer (v5.1) to obtain volumetric data for structures like the lateral ventricles, hippocampus, and amygdala.

This design allows for the separate calculation of intra-session (within the same day) and inter-session (between days) reliability, capturing variability from repositioning, noise, and potential day-to-day biological changes.

Protocol for Comparing Dependent Reliability Coefficients

When comparing the reproducibility of two different measurement devices or platforms used on the same set of subjects, the reliability coefficients (like the WSCV) are dependent. A specialized statistical approach is required for this comparison.

Methodology for Comparing Two Dependent WSCVs [5]:

- Model: A one-way random effects model is fitted for each instrument: ( x{ijl} = \mul + bi + e{ijl} ), where ( x{ijl} ) is the j-th measurement on the i-th subject by the l-th instrument, ( \mul ) is the mean for instrument ( l ), ( bi ) is the random subject effect, and ( e{ijl} ) is the random error.

- Parameter of Interest: The within-subject coefficient of variation for each instrument is ( \thetal = \sigmal / \mu_l ).

- Statistical Tests: The hypothesis of equality of two dependent WSCVs (( H0: \theta1 = \theta_2 )) can be tested using several methods:

This methodology was applied, for instance, to compare the reproducibility of gene expression measurements from Affymetrix and Amersham microarray platforms [5].

Standardization Pipeline for MRI-Based Radiomics

To ensure the reliability of radiomics features in brain MRI, a standardized pre-processing pipeline is critical to mitigate the impact of different scanners and protocols.

Methodology from a Multi-Scanner Radiomics Study [6]:

- Datasets: Two independent datasets, one including 20 patients with gliomas scanned on two different MR devices (1.5T and 3.0T).

- Pre-processing Steps:

- Intensity Normalization: Three methods were evaluated (Nyul, WhiteStripe, Z-Score). The Z-Score method (subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation of the image or ROI) was recommended for first-order features.

- Grey-Level Discretization: Two methods were evaluated (Fixed Bin Size, Fixed Bin Number). A Fixed Bin Number of 32 was recommended as a good compromise.

- Reliability Assessment: The robustness of first-order and second-order (textural) features across the two acquisitions was analyzed using the ICC and the Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC). A feature was considered robust if both ICC and CCC were greater than 0.80.

Table 2: Key Materials and Reagents for Reliability Experiments in Brain MRI

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| 3T MRI Scanner | High-field magnetic resonance imaging for structural brain data. | GE MR750 3T scanner [7]; Siemens MAGNETOM Trio [8]. |

| ADNI Phantom | Quality assurance phantom for scanner calibration and stability. | Used for regular quality assurance tests [7]. |

| T1-Weighted MPRAGE Sequence | High-resolution 3D structural imaging sequence. | ADNI-recommended protocol [7]; Slight parameter variations in multi-session studies [8]. |

| Automated Segmentation Software | Software for automated quantification of brain structure volumes. | FreeSurfer (v5.1) [7]. |

| Intensity Normalization Algorithm | Algorithm to standardize MRI intensities across different scans. | Z-Score, Nyul, WhiteStripe methods [6]. |

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Test-Retest Reliability of Brain Volume Measurements

Application of the test-retest protocol on 3 subjects (40 scans each) yielded the following coefficients of variation for various brain structures, demonstrating the range of reproducibility achievable with automated segmentation software [7]:

Table 3: Test-Retest Reliability of Brain Volume Measurements using FreeSurfer [7]

| Brain Structure | Coefficient of Variation (CV) - Pooled Average |

|---|---|

| Caudate | 1.6% |

| Putamen | 2.3% |

| Amygdala | 3.0% |

| Hippocampus | 3.3% |

| Pallidum | 3.6% |

| Lateral Ventricles | 5.0% |

| Thalamus | 6.1% |

The study also found that inter-session variability (CVt) significantly exceeded intra-session variability (CVs) for lateral ventricle volume (P<0.0001), indicating the presence of day-to-day biological variations in this structure [7].

Impact of Standardization on Feature Reliability

The radiomics standardization study provided quantitative data on how pre-processing impacts the robustness of imaging features [6]:

- First-Order Features: Without intensity normalization, no first-order features were robust (ICC/CCC > 0.8) across T1w-gd and T2w-flair sequences. After applying the Nyul normalization method, 16 out of 18 first-order features became robust for the T1w-gd sequence, and 8 out of 18 for the T2w-flair sequence.

- Classification Performance: For a tumour grade classification task using first-order features from T1w-gd images, intensity normalization significantly increased the mean balanced accuracy from 0.67 (no normalization) to 0.82 (using Z-Score or Nyul normalization).

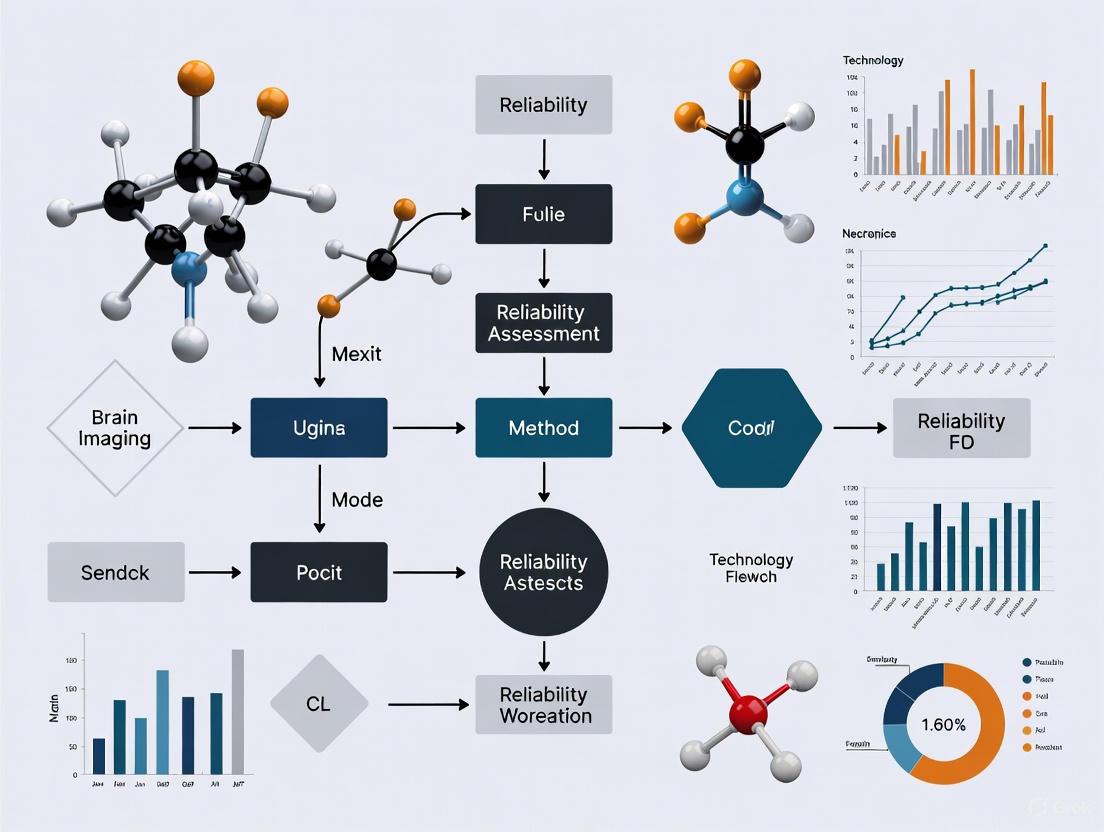

Workflow for Reliability Assessment

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for assessing the reliability of a brain imaging measurement, integrating the concepts of experimental design, metric selection, and standardization.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Assessing Reliability of Brain Imaging Measurements

The objective comparison of ICC and Coefficient of Variation reveals distinct and complementary roles for these metrics in brain imaging reliability assessment. The ICC is the measure of choice for evaluating agreement between different raters or scanners, while the WSCV is superior for quantifying the intrinsic reproducibility of a single measurement device. Experimental data from test-retest studies show that even with automated segmentation, the reliability of volumetric measurements varies substantially across different brain structures. Furthermore, the critical role of image standardization—conceptually related to managing significant bits through discretization—has been quantitatively demonstrated to significantly improve the robustness of derived image features. A rigorous approach to reliability assessment, incorporating appropriate experimental design, metric selection, and standardization protocols, is therefore foundational for generating trustworthy quantitative biomarkers in brain imaging research and drug development.

In the pursuit of establishing functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) as a reliable tool for clinical applications and longitudinal research, understanding and quantifying sources of variance is paramount. The reliability of fMRI measurements is fundamentally challenged by multiple factors that can be broadly categorized as scanner-related, session-related, and biological. These sources of variance collectively influence the reproducibility of findings and the ability to detect genuine neurological effects amid technical noise. This guide systematically compares how these factors impact fMRI reliability, supported by experimental data and methodologies from contemporary research. The broader thesis context emphasizes that without properly accounting for these variance components, the development of fMRI-based biomarkers for drug development and clinical diagnostics remains substantially hindered.

Quantifying Reliability in fMRI Research

Key Reliability Metrics

In fMRI research, reliability is quantified using several statistical metrics, each with distinct interpretations and applications. The most commonly used include:

- Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC): This metric reflects the strength of agreement between repeated measurements and is essential for assessing between-person differences. ICC values range from 0 (no reliability) to 1 (perfect reliability), with values below 0.4 considered poor, 0.4-0.59 fair, 0.60-0.74 good, and above 0.75 excellent [9]. ICC is particularly valuable in psychometrics for gauging individual differentiation.

- Coefficient of Variation (CV): Representing the ratio of variability to the mean measurement, CV expresses measurement precision normalized to the scale metric. In physics-oriented applications, lower CV values indicate greater precision in detecting a specific quantity [10].

- Overlap Metrics (Dice/Jaccard): These measure the spatial similarity of activation maps between sessions, reflecting reproducibility of spatial patterns in thresholded statistical maps [11].

These metrics offer complementary insights—ICC is preferred for individual differences research, while CV better reflects measurement precision in technical validation.

Advanced Reliability Assessment Frameworks

The Intra-Class Effect Decomposition (ICED) framework extends traditional reliability analysis by using structural equation modeling to decompose reliability into orthogonal error sources associated with different measurement characteristics (e.g., session, day, scanner) [10]. This approach enables researchers to quantify specific variance components, make inferences about error sources, and optimize future study designs. ICED is particularly valuable for complex longitudinal studies where multiple nested sources of variance exist.

Inter-Scanner Variability

Scanner-related factors introduce substantial variance in fMRI measurements, particularly in multi-center studies. Hardware differences (magnetic field homogeneity, gradient performance, RF coils), software variations (reconstruction algorithms), and acquisition parameter implementations all contribute to this variability.

Table 1: Inter-Scanner Reliability of Resting-State fMRI Metrics

| fMRI Metric | Intra-Scanner ICC | Inter-Scanner ICC | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude of Low Frequency Fluctuation (ALFF) | 0.48-0.72 | 0.31-0.65 | Greater sensitivity to BOLD signal intensity differences |

| Regional Homogeneity (ReHo) | 0.45-0.68 | 0.28-0.61 | Less dependent on signal intensity |

| Degree Centrality (DC) | 0.35-0.58 | 0.15-0.42 | Shows worst reliability both intra- and inter-scanner |

| Percent Amplitude of Fluctuation (PerAF) | 0.51-0.75 | 0.42-0.68 | Reduces BOLD intensity influence, improving inter-scanner reliability |

Data from [12] demonstrate that inter-scanner reliability is consistently worse than intra-scanner reliability across all voxel-wise whole-brain metrics. Degree centrality shows particularly poor reliability, while PerAF offers improved performance by correcting for BOLD signal intensity variations.

Scanner Type and Harmonization Approaches

Differences in scanner manufacturers and models significantly impact measurements. One study directly comparing GE MR750 and Siemens Prisma scanners found systematic differences in relative BOLD signal intensity attributable to magnetic field inhomogeneity variations [12]. These differences directly affect metrics like ALFF that depend on absolute signal intensity.

Harmonization techniques have been developed to mitigate scanner effects:

- NeuroCombat: A widely used method that applies Empirical Bayes approaches to remove additive and multiplicative scanner effects from neuroimaging data, originally adapted from genomics batch effect correction [13].

- LongCombat: An extension of NeuroCombat designed for longitudinal studies that accounts for within-subject correlations across timepoints [13].

Experimental data from diffusion MRI studies demonstrate that these harmonization methods can reduce both intra- and inter-scanner variability to levels comparable to scan-rescan variability within the same scanner [13].

Scan Length and Temporal Stability

Session-related factors encompass variations across different scanning sessions, including scan length, time between sessions, and physiological state changes. Research demonstrates that scan length significantly influences resting-state fMRI reliability.

Table 2: Impact of Scan Length on Resting-State fMRI Reliability

| Scan Duration (minutes) | Intrasession Reliability | Intersession Reliability | Practical Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-5 | 0.35-0.55 | 0.25-0.45 | Below optimal range for most applications |

| 9-12 | 0.65-0.78 | 0.60-0.72 | Recommended for intersession studies |

| 13-16 | 0.72-0.82 | 0.68-0.75 | Plateau for intrasession reliability |

| >27 | 0.75-0.85 | 0.70-0.78 | Diminishing returns for practical use |

Data from [14] indicate that increasing scan length from 5 to 13 minutes substantially improves both reliability and similarity metrics. Reliability gains follow a nonlinear pattern, with intersession improvements diminishing after 9-12 minutes and intrasession reliability plateauing around 12-16 minutes. This relationship is driven by both increased number of data points and longer temporal sampling.

Task and Experimental Design

The cognitive paradigm and experimental design significantly impact session-to-session reliability. Studies simultaneously comparing multiple tasks have found substantial variation in reliability across paradigms:

- Motor tasks generally show higher reliability (ICC: 0.60-0.75) due to reduced cognitive strategy variations [11].

- Complex cognitive tasks (e.g., working memory, emotion regulation) demonstrate moderate reliability (ICC: 0.40-0.65) due to variable cognitive strategies across sessions [15].

- Block designs typically yield higher reliability than event-related designs for basic sensory and motor tasks [15].

- Contrast type influences reliability, with task-versus-rest contrasts generally more reliable than subtle within-task comparisons [15].

One study directly comparing episodic recognition and working memory tasks found that the interaction between task and design significantly influenced reliability, emphasizing that no single combination optimizes reliability for all applications [15].

Physiological and State Factors

Biological variance encompasses both trait individual differences and state-dependent fluctuations that affect fMRI measurements:

- Head motion: Even when within acceptable thresholds (e.g., <2mm), subtle motion differences between sessions contribute significantly to reliability limitations, accounting for approximately 30-40% of single-session variance in thresholded t-maps [11].

- Cardiac and respiratory pulsations: These introduce cyclic noise that can be misattributed as neural activity, particularly in regions near major vessels [14].

- Cognitive/emotional state: Variations in attentional focus, anxiety, rumination, or mind-wandering between sessions affect BOLD activity patterns [9].

- Vasomotion: Spontaneous oscillations in blood vessel diameter introduce cyclicity in BOLD signals that can be misrepresented as functional connectivity [16].

The cyclic nature of biological signals introduces autocorrelation that violates independence assumptions in standard statistical tests, potentially increasing false positive rates in functional connectivity analyses [16].

Clinical Population Considerations

Biological variance manifests differently in clinical populations, potentially affecting reliability estimates. For example, patients with major depressive disorder may show different reliability patterns due to symptom fluctuation, medication effects, or disease-specific vascular differences [9]. Importantly, ICC values are proportional to between-subject variability, meaning that heterogeneous samples (including both patients and controls) can produce higher ICCs even with identical within-subject reliability [9].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Variance Components

Test-Retest fMRI Protocols

Robust assessment of variance components requires carefully designed test-retest experiments:

Participant Selection and Preparation

- Recruit subjects representative of the target population (e.g., patients for clinical applications) [9]

- Match groups for age, sex, and other relevant demographic factors

- Standardize instructions across sessions regarding eye status (open/closed), cognitive engagement, and alertness

Data Acquisition Parameters

- Use consistent scanning parameters across sessions: TR/TE, flip angle, voxel size, FOV [12]

- Implement physiological monitoring: cardiac, respiratory, and galvanic skin response where possible [14]

- Control for time-of-day effects when feasible [17]

Session Timing Considerations

- For intra-session reliability: 20-60 minute intervals between scans [15]

- For inter-session reliability: Days to weeks between scans, matching intended application intervals [9]

- For longitudinal studies: Months between scans to assess stability over clinically relevant intervals [9]

Processing Pipelines and Statistical Analysis

Preprocessing Steps

- Motion correction using Friston-24 parameter model [12]

- Physiological noise removal (RETROICOR for cardiac/respiratory effects) [14]

- Nuisance regression (white matter, CSF signals, motion parameters) [14]

- Spatial normalization to standard templates (e.g., MNI space) [12]

- Band-pass filtering (typically 0.01-0.1 Hz) with appropriate downsampling to avoid inflation of correlation estimates [16]

Analytical Approaches

- For ROI-based analyses: Extract mean time series from predefined regions

- For voxel-wise analyses: Compute metrics across whole brain

- For connectivity analyses: Apply Fisher's Z-transformation to correlation coefficients to improve normality [14]

- Implement surrogate data methods to account for autocorrelation effects [16]

Visualization of Variance Components in fMRI

This visualization illustrates the complex interplay between major variance sources in fMRI measurements, highlighting how scanner, session, and biological factors collectively influence measurement reliability. The color-coded framework helps researchers identify potential sources of variance in their specific experimental context.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Methods for Variance Control

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for fMRI Variance Assessment

| Tool/Method | Primary Function | Application Context | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| NeuroCombat/LongCombat | Harmonization of multi-scanner data | Multi-center studies, longitudinal designs | [13] |

| ICED Framework | Decomposition of variance components | Experimental design optimization | [10] |

| RETROICOR | Physiological noise correction | Cardiac/respiratory artifact removal | [14] |

| PerAF (Percent Amplitude of Fluctuation) | BOLD intensity normalization | Inter-scanner reliability improvement | [12] |

| Surrogate Data Methods | Autocorrelation-robust hypothesis testing | False positive control in connectivity | [16] |

| FIR/Gamma Variate Models | Flexible HRF modeling | Improved task reactivity estimation | [9] |

| Phantom QA Protocols | Scanner performance monitoring | Variance attribution analysis | [17] |

| 8-Bromo-7-methoxycoumarin | 8-Bromo-7-methoxycoumarin, CAS:172427-05-3, MF:C10H7BrO3, MW:255.06 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 2-(5-Bromothiophen-2-yl)quinoxaline | 2-(5-Bromothiophen-2-yl)quinoxaline|2-Thienylquinoxaline Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Understanding and mitigating sources of variance in fMRI is essential for advancing the technique's application in clinical trials and drug development. Scanner-related factors introduce systematic biases that can be addressed through harmonization techniques like NeuroCombat. Session-related factors, particularly scan length and task design, can be optimized based on the specific reliability requirements of a study. Biological factors present both challenges and opportunities, as they represent both noise and signals of interest in clinical applications. The future of fMRI reliability assessment lies in comprehensive approaches that simultaneously account for multiple variance sources through frameworks like ICED, improved experimental design, and advanced statistical methods that properly account for the complex nature of fMRI data. Researchers should select reliability optimization strategies based on their specific application, whether for individual differentiation, group comparisons, or longitudinal monitoring of treatment effects.

The Reproducibility Crisis in Neuroimaging and Numerical Uncertainty

Recent evidence has revealed a significant reproducibility crisis in neuroimaging, threatening the validity of findings and their application in areas like drug development. This crisis stems from multiple sources, but a critical and often underestimated factor is numerical uncertainty within analytical pipelines. When researchers analyze brain-imaging data, they employ complex processing pipelines to derive findings on brain function or pathologies. Recent work has demonstrated that seemingly minor analytical decisions, small amounts of numerical noise, or differences in computational environments can lead to substantial differences in the final results, thereby endangering the trust in scientific conclusions [18]. This variability is not merely a theoretical concern; studies like the Neuroimaging Analysis Replication and Prediction Study (NARPS) have shown that when 70 independent teams were tasked with testing the same hypotheses on the same dataset, their conclusions showed poor agreement, primarily due to methodological variability in their analysis pipelines [19]. The instability of results can range from perfectly stable to highly unstable, with some results having as few as zero to one significant digits, indicating a profound lack of reliability [18]. This article explores the roots of this crisis, quantifies the impact of numerical uncertainty, and compares solutions aimed at enhancing the reliability of neuroimaging research for scientists and drug development professionals.

Quantifying the Problem: Numerical Uncertainty and Its Impact

Experimental Evidence of Numerical Instability

Direct experimentation has illuminated how numerical uncertainty propagates through analytical pipelines. In one key study, researchers instrumented a structural connectome estimation pipeline with Monte Carlo Arithmetic to introduce random noise throughout the computation process. This method allowed them to evaluate the reliability of the resulting brain networks (connectomes) and the robustness of their features [18]. The findings were alarming: the stability of results ranged from perfectly stable (i.e., all digits of data significant) to highly unstable (i.e., zero to one significant digits) [18]. This variability directly impacts downstream analyses, such as the classification of individual differences, which is crucial for both basic cognitive neuroscience and clinical applications in drug development.

Key Metrics for Assessing Reliability

In neuroimaging, reliability is typically assessed using two primary metrics, which represent different but complementary conceptions of signal and noise. The table below summarizes these core metrics and findings from key studies.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Assessing Reliability and Experimental Findings

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation | Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | ( CVi = \frac{\sigmai}{mi} ) where (\sigmai) is within-object variability and (m_i) is the mean [10]. | Measures precision of measurement for a single object (e.g., a phantom or participant). A lower CV indicates higher precision [10]. | In simulation studies, CV can remain low (good precision) even when the Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC) is low, showing that a measure can be precise but poor for detecting between-person differences [10]. |

| Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC) | ( ICC = \frac{\sigmaB^2}{\sigmaW^2 + \sigmaB^2} ) where (\sigmaB^2) is between-person variance and (\sigma_W^2) is within-person variance [10]. | Measures consistency in assessing between-person differences. Ranges from 0-1; higher values indicate better reliability for group studies [10]. | A high ICC indicates that the measure reliably discriminates among individuals, which is fundamental for studies of individual differences in brain structure or function [10]. |

| Stability (Significant Digits) | The number of digits in a result that remain unchanged despite minor numerical perturbations [18]. | Direct measure of numerical robustness. More significant digits indicate greater stability and lower numerical uncertainty [18]. | Results from connectome pipelines showed variability from "perfectly stable" (all digits significant) to "highly unstable" (0-1 significant digits) [18]. |

The distinction between CV and ICC is critical. A physicist or engineer focused on measuring a phantom might prioritize a low CV, indicating high precision. In contrast, a psychologist or clinical researcher studying individual differences in a population requires a high ICC, which shows that the measurement can reliably distinguish one person from another. A measurement can be precise (low CV) but still be poor for detecting individual differences (low ICC) if the between-person variability is small relative to the within-person variability [10].

The Multifactorial Nature of the Reproducibility Crisis

The reproducibility crisis in neuroimaging is not due to a single cause but arises from a confluence of factors. Evidence for this crisis includes an absence of replication studies in published literature, the failure of large systematic projects to reproduce published results, a high prevalence of publication bias, the use of questionable research practices that inflate false positive rates, and a documented lack of transparency and completeness in reporting methods, data, and analyses [20]. Within this broader context, analytical variability is a major contributor.

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Reliability with ICED

To systematically assess reliability and decompose sources of error, researchers have developed methods like Intra-class Effect Decomposition (ICED). This protocol uses structural equation modeling of data from a repeated-measures design to break down reliability into orthogonal sources of measurement error associated with different characteristics of the measurements, such as session, day, or scanning site [10].

Protocol Steps:

- Study Design: Implement a repeated-measures design where each participant is scanned multiple times. The design should encompass the potential sources of variability of interest (e.g., different sessions on the same day, different days, different scanners in a multi-site study).

- Data Collection: Collect neuroimaging data according to the designed protocol. This could involve structural, functional, or diffusion-weighted MRI.

- Model Specification: Using a structural equation modeling framework, specify a path diagram that represents the different nested sources of variance (e.g., runs nested within sessions, sessions nested within days).

- Variance Decomposition: The ICED model estimates the magnitude of the variance components associated with each specified factor (e.g., day, session, participant).

- Reliability Estimation and Interpretation: The variance components are used to calculate ICC and understand the relative contribution of each factor to the total measurement error. This helps researchers identify the largest sources of unreliability and informs the planning of future studies [10].

Table 2: Decomposing Sources of Variability in Neuroimaging

| Source of Variability | Description | Impact on Reproducibility |

|---|---|---|

| Numerical Uncertainty | Instability in results due to computational environment, rounding errors, or algorithmic implementation [18]. | Leads to impactful variability in derived brain networks, with stability ranging from 0 to all digits being significant [18]. |

| Methodological Choices | Decisions in preprocessing and analysis pipelines (e.g., software tool, parameter settings) [19]. | The primary driver of divergent results in the NARPS study, where 70 teams analyzing the same data reached different conclusions [19]. |

| Data Acquisition | Variability across scanning sessions, days, sites, or scanners [10]. | A major source of measurement error that can be quantified using frameworks like ICED, affecting both CV and ICC [10]. |

| Insufficient Reporting | Lack of transparency and completeness in describing methods and analyses [20]. | Undermines the ability to replicate or reproduce findings, even when checklists like COBIDAS are used [19]. |

The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual relationship between different data and methodology choices and their impact on research conclusions, which was starkly revealed by studies like NARPS.

Figure 1: How One Dataset Can Lead to Many Conclusions. A single input dataset, when processed through different methodological choices and subjected to numerical uncertainty, can yield a wide range of results and divergent scientific conclusions.

Solutions and Comparative Analysis

Standardization and Open Science Practices

A multi-pronged approach is required to combat the reproducibility crisis, focusing on standardization, transparency, and the adoption of robust tools.

- Standardize Preprocessing with Tools like NiPreps: Initiatives such as the NeuroImaging PREProcessing toolS (NiPreps) provide standardized, automated preprocessing pipelines for various modalities (e.g., fMRIPrep for fMRI). These tools leverage the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) for input and output, ensuring consistency, reducing analytical variability, and improving the reliability of the resulting "scores" for subsequent analysis [19].

- Adopt the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS): BIDS provides a consistent framework for organizing neuroimaging data and metadata. This standardization is critical for implementing reproducible research, maximizing data shareability, and ensuring proper data archiving. It also enables the development of BIDS Apps—portable pipeline containers that operate consistently on any BIDS-formatted dataset [19].

- Share Research Plans, Code, and Data: Reproducible research practices advocate for three key steps: (1) sharing research plans via pre-registration; (2) organizing and sharing data in BIDS-formatted repositories like OpenNeuro; and (3) organizing and sharing code using version control (e.g., Git) and containerization (e.g., Docker, Singularity) to capture the exact computational environment [20] [21].

- Quantify and Report Reliability: Researchers should move beyond qualitative statements about reliability and routinely quantify it using appropriate metrics like ICC and CV for their specific context. Frameworks like ICED allow for a nuanced understanding of different error sources, which is invaluable for planning longitudinal studies or multi-site trials [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key tools and resources that form the foundation for reproducible and reliable neuroimaging research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Reproducible Neuroimaging

| Tool/Resource | Category | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| BIDS (Brain Imaging Data Structure) [19] | Data Standard | Provides a consistent framework for structuring data directories, naming conventions, and metadata specifications, enabling data shareability and pipeline interoperability. |

| NiPreps (e.g., fMRIPrep) [19] | Standardized Pipeline | Provides robust, standardized preprocessing workflows for different neuroimaging modalities, reducing analytical variability and improving reliability. |

| DataLad [21] [20] | Data Management | A free and open-source distributed data management system that keeps track of data, ensures reproducibility, and supports collaboration. |

| Docker/Singularity [21] [20] | Containerization | Creates portable and reproducible software environments, ensuring that analyses run identically across different computational systems. |

| Git/GitHub [20] | Version Control | Tracks changes in code and analysis scripts, facilitating collaboration and ensuring the provenance of analytical steps. |

| ICED Framework [10] | Reliability Assessment | Uses structural equation modeling to decompose reliability into specific sources of measurement error (e.g., session, site) for improved study design. |

| OpenNeuro [19] | Data Repository | A public repository for sharing BIDS-formatted neuroimaging data, promoting open data and facilitating re-analysis. |

| 4-Methoxy-6-nitroindole | 4-Methoxy-6-nitroindole|CAS 175913-41-4 | 4-Methoxy-6-nitroindole (CAS 175913-41-4) is a versatile nitro- and methoxy-substituted indole building block for pharmaceutical and agrochemical research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Cis-2-Amino-cyclohex-3-enecarboxylic acid | Cis-2-Amino-cyclohex-3-enecarboxylic Acid | RUO | High-purity Cis-2-Amino-cyclohex-3-enecarboxylic acid for peptide research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The workflow for implementing a reproducible neuroimaging study, integrating these various tools and practices, can be summarized as follows.

Figure 2: A Reproducible Neuroimaging Workflow. A sequential workflow integrating modern tools and practices to enhance the reproducibility and reliability of neuroimaging research from start to finish.

The reproducibility crisis in neuroimaging, significantly driven by numerical uncertainty and analytical variability, presents a formidable challenge to the field. However, it also affords an opportunity to increase the robustness of findings by adopting more rigorous methods. The experimental evidence is clear: numerical instability can lead to impactful variability in brain networks, and methodological choices can dramatically alter research conclusions. For researchers and drug development professionals, the path forward requires a cultural and technical shift towards standardization, transparency, and rigorous reliability assessment. By leveraging standardized pipelines like NiPreps, organizing data with BIDS, sharing code and data openly, and routinely quantifying reliability with frameworks like ICED, the neuroimaging community can build a more robust, reliable, and reproducible foundation for understanding the brain.

Multicenter studies are indispensable in brain imaging research for accelerating participant recruitment and enhancing the generalizability of findings. However, they introduce a complex interplay between statistical power and technical variance. This guide objectively compares the performance of different study designs and analytical tools in managing this balance. We present empirical data on variance components in functional MRI, evaluate the reliability of automated brain volumetry software, and analyze the statistical foundations of design effects. Framed within the broader thesis of brain imaging method reliability, this analysis provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with evidence-based recommendations for optimizing multicenter study design and execution.

In multicenter brain imaging studies, the total observed variance in neuroimaging metrics can be partitioned into several distinct components. Understanding these components is critical for designing powerful studies and interpreting their results accurately. A foundational study dissecting variance in a multicentre functional MRI study identified that in activated regions, the total variance partitions as follows: between-subject variance (23% of total), between-centre variance (2%), between-paradigm variance (4%), within-session occasion (paradigm repeat) variance (2%), and residual (measurement) error (69%) [22].

This variance partitioning reveals that measurement error constitutes the largest fraction, underscoring the significance of technical reliability. Furthermore, the surprisingly small between-centre contribution suggests that well-controlled multicentre studies can be conducted without major compensatory increases in sample size. A separate study on scan-rescan reliability further emphasizes that the choice of software has a stronger effect on volumetric measurements than the scanner itself, highlighting another critical dimension of technical variance [23].

Quantifying the Statistical Power of Multicenter Designs

The statistical power of a multicenter study is fundamentally influenced by its design, which dictates how the center effect is handled statistically. The core concept for quantifying this is the design effect (Deff), defined as the ratio of the variance of an estimator (e.g., a treatment effect) in the actual multicenter design to its variance under a simple random sample assumption [24].

The Design Effect Formula

For a multicenter study comparing two groups on a continuous outcome, the design effect can be approximated by the formula: Deff ≈ 1 + (S - 1)Ï

In this formula:

- Ï is the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), measuring the correlation between data from two subjects in the same center.

- S is a statistic that quantifies the heterogeneity of group distributions across centers (i.e., the association between the group variable and the center) [24].

The value of the Deff directly determines the gain or loss of power:

- Deff < 1: Indicates a gain in power. The multicenter design is more efficient than a simple random sample.

- Deff > 1: Indicates a loss in power. The sample size must be inflated to compensate for the clustering effect.

- Deff = 1: Indicates no net change in power.

Power Implications Across Study Designs

The application of the design effect formula to common research designs reveals how power is differentially affected.

Table 1: Design Effects and Power Implications in Different Multicenter Study Designs

| Study Design | Description | Design Effect (Deff) | Power Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stratified Individually Randomized Trial | Randomization is balanced and stratified per center; equal group sizes within centers. | Deff = 1 - Ï | Gain in Power |

| Multicenter Observational Study | Group distributions are identical across all centers (i.e., constant proportion in group 1). | Deff = 1 - Ï | Gain in Power |

| Cluster Randomized Trial | Entire centers (clusters) are randomized to a single treatment group. | Deff ≈ 1 + [(m - 1)Ï] | Loss of Power |

| Matched Pair Design | A special case of stratification with 1 subject per group in each "center" (e.g., a pair). | Deff = 1 - Ï | Gain in Power |

Key: Ï = Intraclass Correlation Coefficient; m = mean cluster size.

The key insight is that power loss is not an inevitable consequence of a multicenter design. A loss occurs primarily when the grouping variable is strongly associated with the center, as in cluster randomized trials. In contrast, when the group distribution is balanced across centers—through stratification or natural occurrence—the design effect shrinks, leading to a gain in power [24].

Technical Variance in Brain MRI Analysis: A Software Comparison

Technical variance, introduced by different imaging hardware and processing software, is a major threat to the reliability of multicenter brain imaging studies. A recent scan-rescan reliability assessment evaluated seven automated brain volumetry tools across six scanners in twelve subjects [23].

Experimental Protocol for Reliability Assessment

The methodology for assessing technical variance was as follows:

- Subjects: Twelve healthy volunteers.

- Scanning Protocol: Each subject was scanned on six different scanners twice within a 2-hour period on the same day (scan-rescan).

- Software Analysis: The T1-weighted structural images from all scanning sessions were processed through seven different volumetry tools: AssemblyNet, AIRAscore, FreeSurfer, FastSurfer, syngo.via, SPM12, and Vol2Brain.

- Outcome Measures: The primary outputs were gray matter volume, white matter volume, and total brain volume.

- Statistical Analysis: The study employed:

- Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE): To model the significant effects of software and scanner on volumetric measurements.

- Coefficient of Variation (CV): Calculated as a percentage to quantify scan-rescan reliability. A lower CV indicates higher reliability.

- Bland-Altman Analysis: To assess the limits of agreement between methods.

Comparative Reliability of Volumetry Software

The results provide a direct performance comparison of the different software solutions, which is critical for selecting tools in multicenter research.

Table 2: Scan-Rescan Reliability of Brain Volumetry Software Across Multiple Scanners

| Software Tool | Median CV for Gray Matter (%) | Median CV for White Matter (%) | Median CV for Total Brain Volume (%) | Relative Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AssemblyNet | < 0.2% | < 0.2% | 0.09% | High Reliability |

| AIRAscore | < 0.2% | < 0.2% | 0.09% | High Reliability |

| FreeSurfer | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | Lower Reliability |

| FastSurfer | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | Lower Reliability |

| syngo.via | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | Lower Reliability |

| SPM12 | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | Lower Reliability |

| Vol2Brain | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | > 0.2% | Lower Reliability |

The GEE models showed a statistically significant effect (p < 0.001) of both software and scanner on all volumetric measurements, with the software effect being stronger than the scanner effect [23]. This finding underscores that the choice of processing pipeline is a more critical decision than scanner model for minimizing technical variance. While Bland-Altman analysis showed no systematic bias, the limits of agreement varied significantly between methods, meaning that the degree of expected disagreement between measurements depends heavily on the software used.

The Researcher's Toolkit for Multicenter Studies

Success in multicenter brain imaging research relies on a suite of methodological, statistical, and computational tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Multicenter Brain Imaging

| Item / Solution | Category | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Stratified Randomization | Study Design | Balances group distributions across centers to minimize Deff and maximize statistical power [24]. |

| Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) | Statistical Metric | Quantifies the degree of correlation of data within centers; essential for power calculations [24]. |

| Design Effect (Deff) Formula | Statistical Tool | Predicts the impact of the multicenter design on statistical power and required sample size [24]. |

| High-Reliability Volumetry (e.g., AssemblyNet) | Software Tool | Provides consistent and reliable brain volume measurements across different scanning sessions and scanners, reducing technical variance [23]. |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | Software Tool | Offers lower numerical uncertainty in tasks like MRI registration and segmentation compared to traditional tools like FreeSurfer, enhancing reproducibility [25]. |

| Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) | Statistical Model | A robust method for analyzing clustered data (e.g., subjects within centers) that provides valid inferences even with misspecified correlation structures. |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | Metric | A standardized measure (percentage) of scan-rescan reliability used to compare the precision of different measurement tools [23]. |

| 4-Bromo-3-oxo-n-phenylbutanamide | 4-Bromo-3-oxo-N-phenylbutanamide | Research Chemical | 4-Bromo-3-oxo-N-phenylbutanamide for research use only (RUO). A versatile beta-keto amide building block for organic synthesis and medicinal chemistry. |

| Azobenzene, 4-(phenylazo)- | Azobenzene, 4-(phenylazo)-|High-Purity Azo Compound | High-purity Azobenzene, 4-(phenylazo)- for research applications in photopharmacology and smart materials. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Integrated Workflow: From Study Design to Result Interpretation

The relationship between key decisions in a multicenter study and their impact on the final results can be visualized as a workflow where managing statistical and technical variance is paramount. The following diagram synthesizes this process:

Diagram: Impact of Design and Tool Choices on Multicenter Study Outcomes. This workflow illustrates how initial choices in study design and software selection directly influence statistical power and technical variance, thereby determining the ultimate reliability of the study's findings.

The successful execution of a multicenter brain imaging study requires a deliberate and informed balance between statistical power and technical variance. Based on the empirical data and theoretical frameworks presented, the following conclusions and recommendations are offered:

- Prioritize Balanced Designs: To maximize statistical power, employ study designs that balance the group distribution across centers, such as stratified individually randomized trials. This approach transforms the center effect from a source of noise into a factor that increases efficiency, yielding a design effect below 1 [24].

- Select Software for Minimal Variance: The choice of analysis software has a demonstrably greater impact on measurement variance than the choice of scanner. To ensure reliable longitudinal and cross-sectional comparisons, commit to using the same high-reliability software tool (e.g., one with a CV < 0.2%) throughout a study [23].

- Quantify and Account for Variance: During the planning phase, use the design effect formula to perform accurate sample size calculations, incorporating realistic estimates of the ICC. Furthermore, the knowledge that measurement error is the largest component of total variance in fMRI [22] argues for protocols that include task repetition within sessions to improve signal-to-noise ratio.

- Embrace Methodological Consistency: The strongest guarantee of reliable results in multicenter research is the consistent application of the same scanner and software combination across all sites and sessions [23]. This practice minimizes technical variance, ensuring that observed changes in brain measures are more likely to reflect true biological effects rather than methodological inconsistencies.

By integrating these principles—leveraging balanced designs for power, selecting tools for minimal technical variance, and enforcing methodological consistency—researchers can harness the full potential of multicenter studies to generate robust, reproducible, and clinically meaningful findings in brain imaging research.

Impact of Hydration, Menstrual Cycle, and Daily Biological Fluctuations

The reliability of brain imaging measurements is fundamental to their application in both clinical diagnostics and neuroscience research. A significant challenge in achieving this reliability is accounting for inherent biological variability. Fluctuations in physiological states, driven by factors such as hydration status and the menstrual cycle, can alter brain measurements obtained through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetoencephalography (MEG), and functional MRI (fMRI). These fluctuations, if unaccounted for, can introduce confounding variability that mimics or obscures pathological changes, potentially compromising longitudinal study results and clinical trial outcomes. This guide systematically compares the effects of these biological factors on brain imaging metrics, providing researchers and drug development professionals with experimental data and methodologies to improve measurement accuracy.

The Menstrual Cycle: Hormonal Effects on Brain Structure and Function

Quantitative Fluctuations in Neural Oscillations

The menstrual cycle, characterized by rhythmic fluctuations of estradiol and progesterone, induces measurable changes in spontaneous neural activity. A 2021 MEG study quantitatively demonstrated cycle-dependent alterations in resting-state cortical activity [26].

Table 1: Menstrual Cycle Effects on Spectral MEG Parameters (MP vs. OP)

| Spectral Parameter | Change During Menstrual Period (MP) | Brain Regions Involved | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Frequency | Decreased | Global | Significant (p < 0.05) |

| Peak Alpha Frequency | Decreased | Global | Significant (p < 0.05) |

| Shannon Spectral Entropy | Increased | Global | Significant (p < 0.05) |

| Theta Oscillatory Intensity | Decreased | Right Temporal Cortex, Right Limbic System | Significant (p < 0.05) |

| High Gamma Oscillatory Intensity | Decreased | Left Parietal Cortex | Significant (p < 0.05) |

The study found that the median frequency and peak alpha frequency of the power spectrum were significantly lower during the menstrual period (MP), while Shannon spectral entropy was higher [26]. These parameters are established biomarkers for functional brain diseases, indicating that the menstrual cycle is a confounding factor that must be controlled for in clinical MEG interpretations.

Phase-Dependent Shifts in Brain Activation and Connectivity

Beyond spectral properties, the menstrual cycle modulates regional brain activation and large-scale network communication. A 2019 fMRI study investigating spatial navigation and verbal fluency found that, despite no significant performance differences, brain activation patterns shifted dramatically between cycle phases [27].

Table 2: Menstrual Cycle Phase Effects on Brain Activation and Connectivity

| Cycle Phase | Hormonal Profile | Neural Substrate Affected | Observed Effect on Brain Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-ovulatory (Follicular) | High Estradiol | Hippocampus | Boosts hippocampal activation [27] |

| Mid-Luteal | High Progesterone | Fronto-Striatal Circuitry | Boosts frontal & striatal activation; increased inter-hemispheric decoupling [27] |

| Luteal Phase | High Progesterone | Whole-Brain Turbulent Dynamics | Higher information transmission across spatial scales [28] |

The study demonstrated that estradiol and progesterone exert distinct, and often opposing, effects on brain networks. Estradiol enhances hippocampal activation, whereas progesterone boosts fronto-striatal activation and leads to inter-hemispheric decoupling, which may help down-regulate hippocampal influence [27]. Furthermore, a 2021 dense-sampling study using a turbulent dynamics framework showed that the luteal phase is characterized by significantly higher whole-brain information transmission across spatial scales compared to the follicular phase, affecting default mode, salience, somatomotor, and attention networks [28].

Experimental Protocol for Controlling Menstrual Cycle Effects

Study Design: To systematically investigate menstrual cycle effects, the protocol from Pritschet et al. (2019) is exemplary [27]. The study involved scanning participants multiple times across their naturally cycling menstrual cycle.

- Participants: 36 healthy, naturally cycling women with no history of psychological, endocrinological, or neurological illness.

- Cycle Phase Determination: Sessions were scheduled during:

- Menses (Days 2-6): Low estradiol and progesterone.

- Pre-ovulatory Phase (2-3 days before expected ovulation): High estradiol, low progesterone. Confirmed via commercial ovulation tests detecting the luteinizing hormone (LH) surge.

- Mid-Luteal Phase (3-10 days after ovulation): High progesterone, medium estradiol. Confirmed via ovulation tests and subsequent menstruation onset.

- Hormone Assay: Multiple saliva samples were collected per session via unstimulated passive drool, immediately frozen, and later analyzed for estradiol and progesterone concentrations after centrifugation to remove particulate matter.

- fMRI Acquisition: A 3T Siemens scanner was used. The protocol included a T2*-weighted multi-band EPI sequence for resting-state fMRI (TR=720 ms, TE=37 ms, voxel size=2mm³, multiband factor=8). A high-resolution T1-weighted MPRAGE structural scan was also acquired.

- Cognitive Tasks: Participants performed spatial navigation and verbal fluency tasks during scanning to probe brain activation underlying specific cognitive functions.

Hydration Status: Effects on Brain Physiology and Measurement

Cognitive and Mood Consequences of Dehydration

The brain is approximately 75% water, making it highly sensitive to changes in hydration status [29]. Even mild dehydration, defined as a 1-2% loss of body water content, can significantly impair cognitive function and mood.

Table 3: Cognitive and Mood Effects of Mild Dehydration (1-2% Body Water Loss)

| Domain Affected | Specific Impairment | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| General Cognition | Slower reaction times, reduced attention span, cognitive sluggishness | Journal of Nutrition (2011) [29] |

| Mood | Increased fatigue, headaches, concentration difficulties, heightened irritability | British Journal of Nutrition (2011) [29] |

| Memory & Learning | Impaired short-term memory and reduced ability to concentrate | Frontiers in Human Neuroscience (2013) [29] |

| Neural Efficiency | Increased neural activity required for the same cognitive tasks, leading to mental fatigue | The Journal of Neuroscience (2014) [29] |

Notably, studies suggest women may be more sensitive to dehydration-induced cognitive and mood changes than men, reporting more headaches, fatigue, and concentration difficulties under mild dehydration [30]. Furthermore, rehydration after a 24-hour fluid fast improved mood but did not fully restore vigor and fatigue levels, indicating that the effects of significant fluid deprivation can be prolonged [30].

Impact of Hydration on Brain Volume and Water Content Measurements

Despite the clear cognitive effects, the impact of hydration on structural MRI measures of brain volume is a point of methodological importance. A 2016 JMRI study specifically addressed whether physiological hydration changes affect brain total water content (TWC) and volume [31].

- Experimental Protocol: Twenty healthy volunteers were scanned four times on a 3T scanner:

- Day 1: Baseline scan.

- Day 2: Hydrated scan after consuming 3L of water over 12 hours.

- Day 3 (a): Dehydrated scan after a 9-hour overnight fast.

- Day 3 (b): Reproducibility scan one hour later.

- Measurements: Body weight and urine specific gravity were recorded. MRI sequences included T2 relaxation (for TWC), inversion recovery (for T1), and 3D T1-weighted (for brain volumes). TWC was calculated with corrections and normalized to ventricular CSF.

- Findings: Despite objective signs of dehydration (increased urine specific gravity, decreased body weight), the study found no measurable change in total brain water content within any of the 14 regions examined or in overall brain volume between the hydrated and dehydrated states [31].

This suggests that within a range commonly encountered in clinical settings (e.g., overnight fasting), brain TWC and volume as measured by standard MRI protocols are relatively stable. This is a critical insight for designing longitudinal neuroimaging studies.

Implications for Reliability Assessment in Brain Imaging Research

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials and Methods for Controlling Biological Variability

| Item / Solution | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Salivary Hormone Assay Kits | To non-invasively measure fluctuating levels of estradiol and progesterone for precise cycle phase confirmation. | Used to pool multiple saliva samples per session for accurate hormone level correlation with neural data [27]. |

| Urine Specific Gravity Refractometer | To provide an objective, immediate measure of hydration status at the time of scanning. | Served as a key biomarker (along with body weight) to confirm hydration state intervention in a dehydration-MRI study [31]. |

| Commercial Ovulation Test Kits (LH Surge Detection) | To objectively pinpoint the pre-ovulatory phase in naturally cycling women, moving beyond self-report. | Critical for scheduling the pre-ovulatory scan with high temporal precision in a multi-phase cycle study [27]. |

| Automated Segmentation Software (e.g., FreeSurfer) | To provide reliable, quantitative volumetric data for brain structures across multiple time points with minimal manual intervention. | Used to process 120 T1-weighted volumes for test-retest analysis of subcortical structure volume reliability [7]. |

| Standardized MRI Phantoms (e.g., ADNI Phantom) | To monitor scanner stability and performance over time, separating biological variability from instrumental drift. | Employed for regular quality assurance and scanner stability checks throughout a long-term test-retest study [7]. |

| 3-Hydroxy-4-methylpyridine | 3-Hydroxy-4-methylpyridine | Vitamin B6 Intermediate | High-purity 3-Hydroxy-4-methylpyridine for research. A key pyridoxine analog for studying enzyme cofactors & metabolism. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| (S)-4-Aminovaleric acid | (S)-4-Aminovaleric Acid | High-Purity GABA Analog | High-purity (S)-4-Aminovaleric Acid, a selective GABA receptor agonist. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Best Practices for Experimental Design

Integrating the findings on these biological fluctuations leads to several key recommendations for enhancing the reliability of brain imaging data:

- Control for the Menstrual Cycle: In studies involving premenopausal women, the cycle should be a controlled variable. For cross-sectional studies, participants should be scanned in a consistent phase (e.g., early follicular/menses). For longitudinal studies or clinical trials, repeated scans of the same individual should be scheduled in the same cycle phase to minimize hormone-driven variance [26] [27] [32].

- Standardize Hydration Protocols: While brain volume may be resilient to short-term fasting, the clear cognitive and mood effects of dehydration suggest that standardizing hydration instructions (e.g., avoiding significant dehydration) prior to scanning is prudent, especially for task-based fMRI, MEG, or EEG studies where cognitive performance is a metric [30] [29].

- Implement Rigorous Test-Retest Designs: As demonstrated in publicly available test-retest datasets [7] [8], estimating the intra- and inter-session variability of your chosen imaging metrics is crucial. This establishes a benchmark for determining whether observed longitudinal changes exceed normal physiological fluctuations.

- Report and Covary: Transparently report participant information including cycle phase and hydration instructions. Where full control is not feasible, measure and include these factors (e.g., hormone levels) as covariates in statistical models to account for their variance.

Hydration status and the menstrual cycle represent significant sources of biological variability that can impact functional brain measurements, including oscillatory activity, network activation, and cognitive performance. While structural brain volume appears robust to minor hydration shifts, the functional consequences are pronounced. The hormonal fluctuations of the menstrual cycle systematically alter both global spectral properties and region-specific brain activation, with estradiol and progesterone exerting distinct neuromodulatory effects. Acknowledging and controlling for these factors through careful experimental design, phase-specific scheduling, and the use of objective biomarkers is not merely a methodological refinement but a necessity for ensuring the reliability, reproducibility, and ultimate validity of brain imaging data in neuroscience research and drug development.

Analytical Approaches: From Traditional Pipelines to Deep Learning Solutions

In the fields of neuroscience and drug development, the ability to reliably quantify brain structure and function from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is paramount. Automated segmentation software provides essential tools for extracting meaningful biological information from raw MRI data, enabling researchers to track disease progression, evaluate treatment efficacy, and understand fundamental brain processes. The reliability of these tools directly impacts the validity of research findings and the success of clinical trials. Among the most established traditional software tools are Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) and FreeSurfer, which employ distinct processing philosophies and algorithms for brain image analysis [33] [34]. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance based on published experimental data, focusing on their application in reliability assessment research critical for researchers and drug development professionals.

FreeSurfer is a comprehensive open-source software suite developed at the Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Harvard-MGH. Its primary strength lies in cortical and subcortical analysis, utilizing surface-based models to measure cortical thickness, surface area, and curvature [34]. The software creates detailed models of the gray-white matter boundary and pial surface, enabling precise quantification of cortical architecture.

Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM), developed at University College London's Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, is a MATLAB-based software that employs a mass-univariate, voxel-based approach [34]. SPM's segmentation and normalization algorithms use a unified generative model that combines tissue classification, bias correction, and image registration within the same framework, making it particularly effective for voxel-based morphometry (VBM) studies [35].

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Experimental Data

Segmentation Accuracy and Volumetric Precision

Multiple independent studies have evaluated the performance of automated segmentation tools against ground truth data, using both simulated digital phantoms and real MRI datasets with expert manual segmentations.

Table 1: Segmentation Accuracy Compared to Ground Truth

| Software | Gray Matter Volume Deviation | White Matter Volume Deviation | Data Source | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPM5 | ~10% from reference [35] | ~10% from reference [35] | BrainWeb Digital Phantom | 3% noise, 0% intensity inhomogeneity |

| FreeSurfer | >10% from reference [35] | >10% from reference [35] | BrainWeb Digital Phantom | 3% noise, 0% intensity inhomogeneity |

| FSL | ~10% from reference [35] | ~10% from reference [35] | BrainWeb Digital Phantom | 3% noise, 0% intensity inhomogeneity |

| SPM | Highest accuracy [36] | N/A | IBSR Real MRI Data | Compared to expert segmentations |

| VBM8 | Very high accuracy [36] | N/A | IBSR Real MRI Data | Compared to expert segmentations |

| FreeSurfer | Lowest accuracy [36] | N/A | IBSR Real MRI Data | Compared to expert segmentations |

Reliability and Reproducibility Metrics

Test-retest reliability is crucial for longitudinal studies in drug development where tracking changes over time is essential. Different software packages demonstrate varying reliability performance.

Table 2: Reliability Performance Metrics

| Software | Within-Segmenter Reliability | Between-Segmenter Reliability | Test-Retest Consistency | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FreeSurfer | High reliability [36] | Discrepancies up to 24% [35] | High reliability [37] | Real T1 images from same subject scanned twice [36] |

| SPM | N/A | Discrepancies up to 24% [35] | N/A | Real T1 images from same subject scanned twice [36] |

| FSL | Poor reliability [36] | Discrepancies up to 24% [35] | N/A | Real T1 images from same subject scanned twice [36] |

| VBM8 | Very high reliability [36] | N/A | N/A | Real T1 images from same subject scanned twice [36] |

Performance in Clinical Populations

Studies evaluating software performance in specific patient populations reveal important considerations for clinical research and drug development applications.

Table 3: Performance in Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders

| Software | Alzheimer's Disease/MCI | ALS with Frontotemporal Dementia | General Notes on Clinical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| SPM | Recommended for limited image quality or elderly brains [38] | GM volume changes not significant in SPM [39] | Underestimates GM, overestimates WM with increasing noise [38] |

| FreeSurfer | Calculates largest GM, smallest WM volumes [38] | Similar pattern to FSL VBM results [39] | Calculates smaller brain volumes with increasing noise [38] |

| FSL | Calculates smallest GM volumes [38] | GM changes similar to FreeSurfer cortical measures [39] | Increased WM, decreased GM with image inhomogeneity [38] |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Reliability Assessment

Digital Phantom Validation Studies

The BrainWeb simulated brain database from the Montreal Neurological Institute provides a critical resource for validation studies, offering MRI datasets with varying image quality based on known "gold-standard" tissue segmentation masks [36] [35].

Protocol Summary:

- Data Source: Twenty simulated T1-weighted MRI images from BrainWeb with known ground truth segmentations [36]

- Image Quality Variations: Systematic manipulation of noise levels (0-9%) and intensity inhomogeneity (0-40%) [35]

- Processing Pipeline: Identical preprocessing applied across all software platforms

- Validation Metric: Dice similarity coefficient comparing automated segmentation with ground truth [36]

- Statistical Analysis: Quantitative comparison of volumetric deviations from reference values [35]

This approach allows researchers to assess both within-segmenter (same method, varying image quality) and between-segmenter (same data, different methods) comparability under controlled conditions.

Real MRI Data Validation with Expert Segmentations

Protocol Summary:

- Data Source: Internet Brain Segmentation Repository (IBSR) providing 18 real T1-weighted MR images with expert manual segmentations [36]

- Processing: Each software package processes images using default recommended parameters

- Validation Metric: Overlap measures (Dice coefficient) between automated and manual segmentations

- Additional Metrics: Volume difference ratios, false positive/negative rates [36]

- Statistical Analysis: Correlation coefficients, intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability assessment

Longitudinal Reliability Assessment

Protocol Summary:

- Data Acquisition: Repeated scanning of the same subject with minimal time interval (test-retest design)

- Processing: Identical processing pipelines applied to all scans

- Metrics: Coefficient of variation, intraclass correlation coefficients for volumetric measurements

- Analysis: Comparison of within-subject variability between software platforms [37]

Processing Streams: Architectural Workflows

The fundamental differences between FreeSurfer and SPM emerge from their distinct processing philosophies, which can be visualized through their workflow architectures.

The diagram above illustrates the fundamental architectural differences between FreeSurfer's surface-based stream and SPM's voxel-based stream. FreeSurfer emphasizes precise cortical surface modeling through a sequence of topological operations, while SPM focuses on voxel-wise statistical comparisons through spatial normalization and tissue classification.

Table 4: Essential Resources for Brain Imaging Reliability Research

| Resource | Type | Function in Research | Relevance to Software Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| BrainWeb Database | Simulated MRI Data | Provides digital brain phantoms with known ground truth for validation [36] | Enables controlled assessment of accuracy under varying image quality conditions [35] |

| IBSR Data | Real MRI with Expert Segmentations | Offers real clinical images with manual tracings for benchmarking [36] | Allows validation of automated methods against human expert performance |

| OASIS Database | Large-Scale Neuroimaging Database | Provides diverse dataset for testing generalizability [35] | Enables assessment of performance across different populations and scanners |

| UK Biobank Pipeline | Automated Processing Pipeline | Demonstrates large-scale application of processing methods [33] | Illustrates real-world implementation challenges and solutions |

| DARTEL | SPM Algorithm | Improved spatial normalization using diffeomorphic registration [39] | Enhances SPM's registration accuracy for longitudinal studies |

| Threshold Free Cluster Enhancement (TFCE) | FSL Statistical Method | Improves statistical inference in neuroimaging [39] | Highlights impact of statistical methods on final results |

The experimental data reveals that software selection involves significant trade-offs between accuracy, reliability, and methodological approach. FreeSurfer demonstrates advantages for cortical analysis and longitudinal reliability, while SPM shows strengths in statistical parametric mapping and handling of challenging image quality. For drug development professionals tracking subtle changes in clinical trials, FreeSurfer's test-retest reliability may be particularly valuable. For researchers investigating voxel-wise structural differences across populations, SPM's VBM approach may be preferable. Critically, studies consistently show that between-software differences can reach 20-24%, comparable to disease effects, necessitating consistent software use throughout a study [39] [35]. The emerging generation of deep-learning tools like FastSurfer offers promising directions for combining the accuracy of traditional methods with significantly improved processing speed [37].