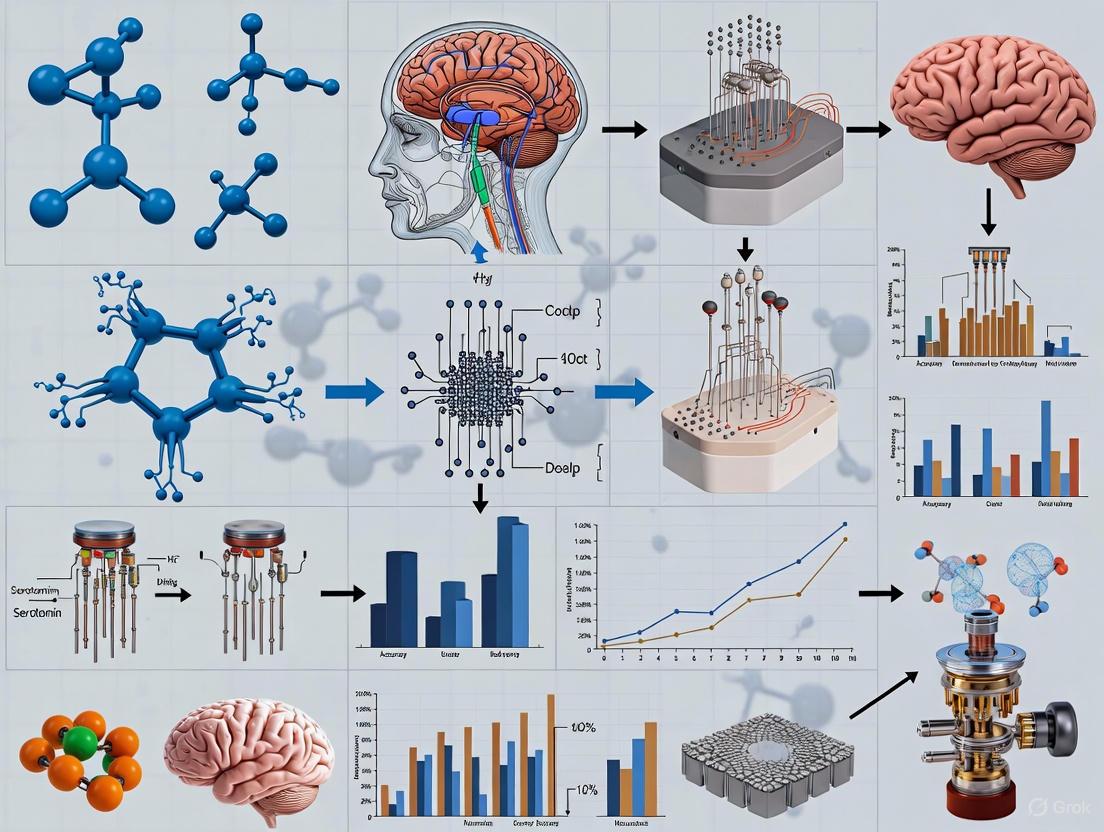

Enhancing Brain-Computer Interface Accuracy: A Research-Focused Guide to Methodologies, Optimization, and Validation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of modern strategies for enhancing the accuracy of Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Enhancing Brain-Computer Interface Accuracy: A Research-Focused Guide to Methodologies, Optimization, and Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of modern strategies for enhancing the accuracy of Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational challenges of BCI signal acquisition, examines cutting-edge methodological advances in stimulation paradigms and deep learning, details systematic troubleshooting for low performance, and establishes robust frameworks for the validation and comparative analysis of BCI systems. The scope spans both non-invasive and invasive technologies, with a focus on applications in clinical diagnostics, neurorehabilitation, and assistive devices, offering a roadmap for developing more reliable and effective neural interfaces.

Understanding the Core Challenges and Principles of BCI Accuracy

For researchers and scientists dedicated to brain-computer interface advancement, precisely defining and measuring "accuracy" presents a complex, multidimensional challenge. In the context of ongoing accuracy enhancement research, performance transcends simple classification percentages; it encompasses the information transfer rate (ITR), latency, and system adaptability that collectively determine real-world usability [1] [2]. The establishment of rigorous, standardized benchmarks, such as the recently introduced SONIC (Standard for Optimizing Neural Interface Capacity), represents a pivotal shift from application-specific demonstrations to fundamental, application-agnostic performance metrics [1]. This technical resource frames key performance concepts within the researcher's workflow, providing actionable guidance for evaluating and troubleshooting BCI system accuracy against the latest 2025 benchmarks.

The global BCI research landscape is experiencing accelerated growth, with the market projected to expand at a CAGR of 15.13% from 2025 to 2033, driven by intensive R&D investments [3]. China has demonstrated exponential growth in BCI publications since 2019, now leading the United States in publication volume, signaling the technology's strategic importance [4]. This growth necessitates clear, standardized performance metrics to enable meaningful cross-study comparisons and accelerate collective progress in accuracy enhancement.

Table: Core BCI Performance Metrics and Target Values for High-Accuracy Systems

| Metric | Description | Representative High Performance | Relevance to Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information Transfer Rate (ITR) | The speed of information conveyance (bits/second) [1] | >200 bps (Paradromics Connexus BCI) [1] | Measures useful output, combining speed and classification correctness |

| Classification Accuracy | Percentage of correct intent classifications [5] | 97.24% (Motor Imagery with advanced DL) [5] | Raw decoding capability of the algorithm |

| Latency | Delay between brain signal and system output (milliseconds) [1] | 11ms for >100 bps (Paradromics Connexus BCI) [1] | Critical for real-time, closed-loop applications |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Quality of neural signal against background noise [2] | Varies by modality (Invasive > Non-invasive) | Foundation for reliable feature extraction |

Core Performance Metrics and Benchmarks

Information Transfer Rate: The Gold Standard for Communication Speed

The Information Transfer Rate has emerged as a crucial benchmark for evaluating the practical speed of a BCI system, particularly for communication applications. It comprehensively reflects the combination of classification accuracy and the number of available choices in a single metric, measured in bits per second (bps) [1]. Recent benchmarking demonstrates the performance frontier: the Paradromics Connexus BCI has achieved over 200 bps with 56ms latency, a rate that exceeds the information density of transcribed human speech (~40 bps) [1]. This provides high confidence for restoring rapid communication.

For context, other contemporary systems operate at different performance tiers. Initial results from intracortical systems like Neuralink and BrainGate have demonstrated ITRs approximately 10-20 times lower than the 200 bps benchmark, while endovascular approaches like Synchron's Stentrode report rates 100-200 times slower [1]. When troubleshooting slow communication rates, researchers should first verify ITR calculations, which account for both speed and accuracy, rather than relying solely on words-per-minute metrics that can obscure underlying limitations.

Classification Accuracy and Error Handling

Raw classification accuracy remains a fundamental metric, especially for discrete control tasks. State-of-the-art deep learning approaches now achieve remarkable performance on specific paradigms; for instance, hierarchical attention-enhanced convolutional-recurrent networks have reached 97.24% accuracy on four-class motor imagery tasks [5]. However, high accuracy in controlled laboratory settings does not always translate to robust real-world performance.

Table: Troubleshooting Guide for Poor Classification Accuracy

| Symptom | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Steps | Possible Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| High variability between subjects | Non-stationary EEG signals [2], Inter-subject physiological differences [6] | Analyze performance per subject; Check for consistent signal patterns | Implement subject-specific calibration [2]; Use transfer learning approaches [5] |

| Accuracy degradation over time | Electrode drift [7], Skin impedance changes [6], User fatigue | Monitor signal quality metrics (SNR, impedance); Track performance over sessions | Implement adaptive classifiers [2]; Schedule shorter sessions; Use online re-calibration |

| Consistently low accuracy across all conditions | Poor feature selection [7], Inappropriate classifier choice, Excessive noise | Review feature importance; Analyze noise sources in data acquisition | Optimize feature extraction (CSP, FBCSP) [5]; Try ensemble methods [5]; Enhance preprocessing |

| Good offline but poor online accuracy | Lack of real-time adaptation, Feedback latency issues [1] | Compare offline vs. online performance; Measure system latency | Implement closed-loop feedback; Optimize for real-time processing [2] |

The Critical Role of Latency in Real-Time Systems

Latency represents the total delay between neural signal generation and system output, a metric increasingly recognized as equally important as throughput for interactive applications [1]. As demonstrated through intuitive benchmarks like the Super Mario Bros. Wonder gameplay test, system responsiveness dramatically affects usability: at 200ms delay, control becomes clumsy, and at 500ms, the game becomes unplayable [1]. High-performance systems now achieve remarkable latencies, with the Paradromics Connexus BCI demonstrating 11ms total system latency while maintaining over 100 bps [1].

When troubleshooting latency issues, researchers should profile each component of the BCI pipeline: signal acquisition, preprocessing, feature extraction, classification, and device output. Some decoding methods that analyze long blocks of data retrospectively can achieve high ITRs but introduce prohibitive delays for conversational applications [1]. The SONIC benchmark specifically addresses this by measuring ITR and latency concurrently, preventing systems from gaming one metric at the expense of the other [1].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking BCI Accuracy

Establishing a Standardized Motor Imagery Paradigm

For motor imagery-based BCIs, standardized experimental protocols enable meaningful cross-study comparisons and facilitate accuracy enhancement. A robust MI-BCI pipeline encompasses several critical stages, each contributing to overall system performance [6]:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Begin with proper electrode placement according to the international 10-20 system, focusing on C3, Cz, and C4 positions for hand motor imagery [6]. For non-invasive systems, ensure proper skin preparation and electrode contact to maximize SNR. Apply bandpass filtering (e.g., 8-30 Hz to capture mu and beta rhythms) and artifact removal techniques (ocular, muscular, line noise) [5] [6].

Feature Extraction and Selection: Extract discriminative features that capture event-related desynchronization/synchronization (ERD/ERS) patterns. Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) and Filter Bank CSP (FBCSP) remain widely used, though deep learning approaches can automatically learn optimal features [5]. Implement feature selection algorithms to reduce dimensionality and mitigate the curse of dimensionality, particularly critical for high-channel-count systems [6].

Implementing the SONIC Benchmarking Protocol

The SONIC benchmarking paradigm introduced by Paradromics provides a rigorous framework for evaluating BCI performance through application-agnostic metrics [1]. This approach addresses a critical need in accuracy enhancement research by enabling objective comparisons across different neural interface technologies.

Stimulus Presentation and Neural Recording: Present controlled sequences of sensory stimuli (e.g., distinct sound patterns representing characters) while recording neural activity from appropriate cortical regions (e.g., auditory cortex for sound stimuli). Maintain precise timing synchronization between stimulus presentation and neural data acquisition [1].

Neural Decoding and Information Calculation: Employ decoding algorithms to predict presented stimuli based solely on recorded neural activity. Calculate the mutual information between presented and predicted stimuli sequences to derive the true information transfer rate, measured in bits per second [1].

Latency Measurement: Simultaneously measure the total system latency from stimulus onset to decoded output, ensuring both high information throughput and minimal delay. This prevents the trade-off of one metric for the other, which can occur in systems that use long data blocks for decoding [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for BCI Accuracy Enhancement

| Reagent/Solution Category | Specific Examples | Function in BCI Research | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced Classification Algorithms | Hierarchical Attention CNNs [5], CNN-LSTM Hybrid Models [5], Transfer Learning Approaches [2] | Improve decoding accuracy of neural signals; Handle temporal dynamics of EEG | Reduces need for per-subject calibration; Manages non-stationary EEG signals [2] |

| Signal Processing Tools | Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) [5], Filter Bank CSP (FBCSP) [5], Artifact Removal Algorithms | Extract discriminative features from noisy signals; Separate neural activity from artifacts | Critical for improving SNR in non-invasive systems [6] |

| Neural Recording Technologies | High-Density Utah Arrays [8], Endovascular Stentrodes [8], Flexible ECoG Grids [8] | Acquire neural signals with varying trade-offs of invasiveness and signal quality | Choice depends on target application and risk-benefit considerations [4] |

| Benchmarking Frameworks | SONIC Protocol [1], BCI Competitions Datasets, Standardized Performance Metrics | Enable objective comparison across systems and laboratories | Facilitates reproducibility and accelerates field-wide progress [1] |

| Real-Time Processing Platforms | Low-Latency Signal Processing Pipelines [1], Adaptive Classification Systems [2] | Minimize delay between neural activity and system output | Essential for closed-loop applications and natural user interaction [1] |

FAQs: Troubleshooting Common BCI Accuracy Challenges

Q1: Our BCI system achieves high offline classification accuracy (>95%) but performs poorly in online tests. What could explain this discrepancy?

A: This common challenge often stems from inadequate real-time processing or insufficient system adaptability. Offline analysis typically uses cleaned, segmented data, while online operation must handle continuous, noisy signals with strict timing constraints [2]. First, verify your system's latency meets real-time requirements (<100ms for responsive control) [1]. Second, implement adaptive algorithms that can adjust to non-stationary EEG signals and changing user states [2]. Finally, ensure your feature extraction methods are robust enough for real-time operation without excessive computational demands.

Q2: How can we improve low signal-to-noise ratio in our non-invasive EEG-based BCI?

A: Improving SNR requires a multi-pronged approach. Technically, ensure proper electrode-skin contact and consider dry electrode technologies that balance convenience with signal quality [9]. Algorithmically, implement advanced artifact removal techniques and spatial filtering methods like Common Spatial Patterns [5]. For motor imagery paradigms, frequency-domain analysis focusing on mu (8-12 Hz) and beta (13-25 Hz) rhythms can help isolate task-relevant signals from background noise [6]. Recent deep learning approaches that automatically learn noise-resistant features have shown particular promise, achieving up to 97.24% accuracy on motor imagery tasks despite EEG's inherent noise [5].

Q3: What are the current benchmark values for high-performance BCI systems that we should target in our research?

A: Current performance frontiers vary by technology approach. For invasive intracortical systems, the benchmark to target is >200 bps ITR with <60ms latency, as demonstrated by the Paradromics Connexus BCI [1]. For non-invasive motor imagery systems, state-of-the-art classification accuracy reaches 97.24% on four-class problems using advanced deep learning architectures [5]. When evaluating your system, use comprehensive metrics that include ITR, latency, and accuracy rather than any single measure, as this prevents optimizing one parameter at the expense of others [1].

Q4: How significant is inter-subject variability in BCI performance, and what strategies can address it?

A: Inter-subject variability represents a major challenge in BCI research, with performance differences of 20-30% accuracy points between users being common [2]. This stems from anatomical differences, cognitive strategies, and neurophysiological factors. Effective solutions include: (1) Transfer learning approaches that leverage data from multiple subjects to initialize models for new users [5]; (2) Subject-specific calibration protocols that adapt to individual signal characteristics [2]; and (3) Hybrid model architectures that combine population-level priors with subject-specific fine-tuning. These approaches can significantly reduce calibration time while maintaining high accuracy across diverse users.

Q5: What are the emerging trends in BCI accuracy enhancement that we should monitor?

A: Key emerging trends include: (1) Hybrid AI models that combine different neural network architectures to capture both spatial and temporal features in neural data [10]; (2) Explainable AI frameworks that provide interpretable insights into decoding decisions, moving beyond "black box" models [10]; (3) Multimodal fusion approaches that integrate EEG with other signals (fNIRS, MEG) to overcome limitations of individual modalities [10]; and (4) Standardized benchmarking initiatives like SONIC that establish rigorous, transparent performance metrics for the entire field [1]. The integration of real-time processing capabilities with these advanced algorithms represents the next frontier in making high-accuracy BCIs practically deployable outside controlled laboratory settings [2].

Fundamental Concepts: Neural Variability and Noise

What are the core components of neural signal variability?

Neural signal variability is not merely noise; it is a fundamental property of the nervous system with distinct components that impact Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) performance. Research on sensory-motor latency in pursuit eye movements reveals that trial-by-trial variation comprises two primary components [11]:

- Shared Variability: This component is correlated across neurons and originates from common inputs to neural populations. It propagates through sensory-motor circuits and directly creates movement-by-movement variation in behavior [11].

- Independent Variability: This component is local to each neuron. Surprisingly, analysis shows it arises heavily from fluctuations in the underlying probability of spiking (synaptic inputs) rather than from the stochastic nature of spiking itself [11].

Furthermore, the relationship between neural latency and behavioral latency strengthens at successive stages of motor processing. The sensitivity of neural latency to behavioral latency increases from approximately 0.18 in area MT to about 1.0 in the final brainstem motor pathways [11].

Should neural variability always be minimized?

Traditionally viewed as a barrier, neural variability is increasingly recognized as a critical element for brain function. A paradigm shift is occurring toward harnessing neural variability to enhance adaptability and robustness in neural systems, rather than seeking to eliminate it entirely [12]. The goal for BCI research is to leverage this understanding to develop more precise and effective protocols [12].

Practical Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Common Issues

Why is my BCI accuracy low or seemingly random?

Low BCI accuracy can stem from various problems in the user, hardware, or software components of the system. The following table summarizes common error sources and their solutions [13].

| Error Category | Specific Issue | Symptoms | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| User-Related | Inherent Physiology | Different signal quality across users due to head shape, cortical folding. | Little can be done if signal is degraded by volume conduction; consider alternative technologies [13]. |

| Skill/Motivation/State | User tired, poorly instructed, using wrong mental strategy. | Ensure user is motivated, well-tutored, and well-rested. Provide engaging feedback and extended training [13]. | |

| Acquisition-Related | Electrode Conductivity | Flatlined channels, excessive noise, unrealistic signal amplitudes [14]. | Check impedance values; ensure they are low. Verify signal quality by checking for expected artifacts (blinks) and alpha waves with eyes closed [13]. |

| Electrode Positioning | Poor feature detection. | Verify electrode placement matches the requirements of the BCI paradigm (e.g., motor imagery requires coverage over motor cortex) [13]. | |

| Electrical Interference | 50/60 Hz power line noise in the signal. | Use a software notch filter. Keep electrode cables away from power transformers and other interference sources [13]. | |

| Amplifier Issues | Consistent, unexplained noise or signal distortion. | Test with a known-good amplifier or a signal generator. For high-end devices, contact the manufacturer for testing [13]. | |

| Software/DSP-Related | Unoptimal Parameters | Suboptimal performance for a specific user. | Re-tune parameters (e.g., filters, classifier) for each user and session to account for non-stationarity [13]. |

| Timing Issues (e.g., P300) | Misalignment of event markers and data. | Disable background tasks on the acquisition computer. Set CPU to "Performance" mode to prevent timing jitter [13]. |

How can I systematically diagnose a flatlined or noisy EEG channel?

Flatlined channels (showing no signal) typically indicate a break in the signal path, while channels with unrealistically high amplitude (e.g., ~200,000 µV) suggest severe noise or a poor connection [14].

- Visual Inspection: Use your acquisition software's live view to inspect the raw signal.

- Impedance Check: Use the software's impedance-checking feature (if available) to verify each electrode's connection. Values should be low and stable [13].

- Continuity Test: With the system off, use a digital multimeter to check the electrical continuity from the amplifier pin to the electrode, wiggling wires and connectors to find intermittent faults [14].

- Component Swap: If possible, swap the suspect electrode cable with a known-good one to isolate the faulty component.

- Gain Verification: If signals appear saturated or "railed," ensure the amplifier gain is set appropriately. This can often be configured via software commands to the board [14].

Advanced Experimental Protocols for Minimizing Variability

What is a proven method to minimize EEG variability for BCI applications?

A key challenge in EEG-based BCIs is significant intra-subject signal variability. A robust procedure focuses on selecting optimal bipolar electrode pairs and signal transformations to enhance stability [15].

Experimental Protocol: Minimizing EEG Variability via Channel and Feature Selection [15]

- Objective: To find subject-specific pairs of electrodes and signal transformations that yield the lowest inter-trial variability for a given task (e.g., motor imagery).

- Hypothesis: Lower variability is associated with more stable movement-related information, leading to higher classification accuracy.

- Materials: EEG system with a cap following the 10-20 system; recording software.

- Procedure:

- Data Collection: Record EEG data while the subject performs multiple trials of the target task (e.g., imagined hand movement).

- Channel Pair Generation: Consider all possible bipolar pairs from the recorded electrodes, not just the original reference.

- Signal Transformation: For each bipolar channel, compute various signal transformations (e.g., energy in specific frequency bands like delta (0-4 Hz) for movement-related CNV/RP, or alpha/beta for ERD).

- Variability Assessment: Calculate the inter-trial variability for each channel-feature combination using a metric like the Pearson correlation coefficient.

- Selection: Identify the combinations (channel pair and transformation) that show the lowest variability across trials.

- Validation: Test the selected configurations in a pseudo-online classification algorithm to validate improved detection accuracy.

This method directly addresses the active reference electrode problem and volume conduction without introducing the mathematical uncertainties of spatial filters like Laplacian or Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) [15]. Results from applying this protocol showed an average classification accuracy of 95% across 15 subjects, with the delta band energy and electrodes along the CCP line often associated with the lowest variability [15].

Workflow Diagram: Variability Minimization Protocol

Technical Solutions and Research Reagents

What are the key signal processing challenges and solutions for BCIs?

The signal processing pipeline is the most vital component for a successful BCI. Critical issues and promising approaches include [16]:

- Signal Non-Stationarity: Neural signals change over time due to learning, fatigue, and other factors. Unsupervised adaptation of features and classifiers is crucial to cope with these changes [16].

- Time-Embedded Representations: Standard power spectral densities (PSDs) have a limited ability to capture temporal information. Time-embedding techniques and neural networks can better model the temporal dynamics of neural signals [16].

- Utilizing Phase Information: The phase of oscillatory signals contains valuable information that is underutilized in many current BCI systems [16].

- EEG vs. ECoG Signal Scale: EEG records from a large pooling area (~4-5 cm diameter), which can average away fine-scale, asynchronous activity. ECoG records from a much smaller area (~0.9 mm), allowing it to capture focal, high-frequency broadband changes that are highly correlated with local neural activity and firing rates. This is a fundamental reason for ECoG's superior spatial resolution [16].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and their functions in advanced neural interface research.

| Item | Function & Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Implantable Neural Electrodes (Michigan/Utan arrays) | Record and modulate neural activities with high spatial and temporal resolution for invasive BCIs [17]. | Biocompatibility is critical; mechanical mismatch with soft brain tissue can induce immune response and scar formation, degrading long-term performance [17]. |

| Flexible Neural Interfaces | Reduce foreign body response and improve long-term signal stability in implantable BCIs [18]. | Made from polymers with Young's modulus closer to neural tissue (1-10 kPa) to minimize micromotion damage [17]. |

| Conducting Polymers (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) | Coat electrodes to improve electrical properties (impedance, charge injection) at the neural tissue-electrode interface [17]. | Enhishes signal-to-noise ratio and transduction of electrical signals [17]. |

| Closed-Loop Neurostimulation Systems | Deliver targeted, adaptive stimulation in response to real-time neural signals (e.g., to prevent epileptic seizures) [18] [19]. | Integrates neural signal recording with on-demand stimulation, often using AI for detection and control [19]. |

| AI/Deep Learning Models (CNNs, RNNs, LSTMs) | Decode complex neural activity patterns for prosthetic control and communication [19]. | Capable of learning hierarchical spatiotemporal representations from raw neural data, improving decoding precision [19]. |

Signaling Pathway Diagram: From Neural Source to BCI Command

The Impact of User Physiology and State on Signal Quality

FAQs: User Physiology and Signal Quality

FAQ 1: How do fluctuating attention levels impact the performance of my motor imagery BCI?

Fluctuating attention is a primary cause of performance variation in BCIs. During a target detection task, attention levels are significantly higher during the task compared to rest periods, but they also exhibit a decay over time [20]. This decay directly affects the signal quality and separability of EEG patterns. Furthermore, task engagement and attentional processes significantly impact the performance of P300 and motor imagery paradigms [20]. To mitigate this, implement a passive BCI system in parallel to monitor the user's attentional state in real-time using EEG power band analysis, allowing the system to adapt or prompt the user [20].

FAQ 2: What is the observable effect of mental fatigue on my EEG signals, and how can it be quantified?

Mental fatigue produced by prolonged cognitive tasks increases the power of theta (4-7 Hz) and alpha (8-12 Hz) oscillations in the brain, which leads to a decrease in the separability of EEG signals and a corresponding drop in BCI classification accuracy [20]. In experiments, fatigue levels have been shown to increase gradually and then plateau during extended sessions [20]. You can quantify fatigue by calculating the power spectral density of these frequency bands from electrodes in the parietal and occipital lobes over time. Setting a threshold for normalized theta/beta power ratio can serve as a trigger for initiating countermeasures or recalibration [20].

FAQ 3: Can a user's stress level interfere with the signal acquisition process?

Yes, stress is a key factor that affects the signal-to-noise ratio and overall BCI performance [20]. Research shows that stress levels, similar to attention, decrease as an experiment proceeds [20]. Stress responses and negative emotions are associated with negative frontal alpha asymmetry scores, which are calculated by subtracting the natural log-transformed left hemisphere alpha power from the right (F4-F3) [20]. Monitoring this metric in real-time can provide an indicator of a user's stress state.

FAQ 4: Are there long-term physiological changes I should anticipate with implanted microelectrode arrays?

Intracortical microelectrode arrays can provide stable signals for extended periods. Safety data for intracortical microstimulation (ICMS) in the somatosensory cortex shows that it can remain safe and effective in human subjects over many years, with one participant showing reliable electrode function after a decade [21]. Furthermore, a recent clinical case demonstrated that a paralyzed individual used a chronic intracortical BCI independently at home for over two years without daily recalibration, maintaining high performance in speech decoding [21]. However, it is known that brain electrodes can degrade over time, and some signal instability should be anticipated [21].

FAQ 5: How does the choice of signal type (e.g., spikes vs. ECoG) relate to the stability and longevity of my BCI recordings?

The choice of input signal involves a fundamental trade-off between information content, longevity, and stability. Intracortical single-unit activity (SUA or "spikes") has high movement-related information but may face challenges with long-term stability due to tissue response and electrode degradation [22]. In contrast, subdural electrocorticography (ECoG) and epidural signals, which record field potentials from the cortical surface, generally offer superior long-term signal stability [22]. The largest proportion of motor-related information in ECoG is contained in the high-gamma band, making it a robust signal for sustained BCI operation [22].

Quantitative Data on Physiological States and Signal Metrics

Table 1: Correlations Between Physiological States and EEG Spectral Features

| Physiological State | EEG Spectral Correlates | Observed Impact on BCI Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Attention | Decreased frontal alpha power [20] | Significantly higher during tasks vs. rest; decay over time reduces P300 and MI classification [20] |

| Mental Fatigue | Increased theta and alpha power, especially in parietal/occipital lobes [20] | Decreased signal separability and classification accuracy; plateau effect over time [20] |

| Stress | Negative frontal alpha asymmetry (F4-F3) [20] | Decreased signal-to-noise ratio (SNR); inverted-U relationship with performance [20] |

| Motor Imagery | Event-related desynchronization (ERD) in mu/beta rhythms over sensorimotor cortex [5] | Deep learning models can achieve high classification accuracy (>97%) with clean data [5] |

Table 2: Longevity and Stability Profiles of Invasive BCI Input Signals

| Signal Type | Longevity & Stability Profile | Key Physiological Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Intracortical Spikes (SUA) | High information content, but potential long-term stability challenges [22] | Originates from single neurons; gold standard for movement-related information [22] |

| Local Field Potentials (LFP) | More stable for long-term recordings compared to spikes [22] | Hypothesized to be produced by summation of local postsynaptic potentials [22] |

| Electrocorticography (ECoG) | High long-term stability; suitable for chronic clinical use [22] [21] | Movement information concentrated in high-gamma band; good spatial and spectral resolution [22] |

| Intracortical Microstimulation (ICMS) | Safe and effective over years (up to 10 years demonstrated) [21] | Evokes tactile sensations; over half of electrodes remain functional long-term [21] |

Experimental Protocols for Physiology and Signal Quality

Protocol 1: Real-Time Monitoring of Attention and Fatigue During BCI Operation

Objective: To quantify the decay of attention and the rise of mental fatigue during a prolonged BCI session and assess their impact on task performance.

Methodology:

- Setup: Use a standard EEG cap with at least 14 channels. Focus electrode placement on frontal (for attention, F3, F4, Fz) and parietal/occipital sites (for fatigue, Pz, O1, O2) [20].

- Task Design: Administer a target detection task, such as a modified cognitive attention network test (ANT), in blocks interspersed with rest periods [20].

- Signal Acquisition: Record EEG continuously throughout the session.

- Online Processing:

- Attention Parameter: In real-time, calculate the average power in the alpha band (8-12 Hz) from frontal electrodes. A rising alpha power indicates decreasing attention [20].

- Fatigue Parameter: Calculate the theta (4-7 Hz) and alpha (8-12 Hz) power from parietal/occipital electrodes. An increase in the normalized ratio of (theta+alpha)/beta indicates increasing fatigue [20].

- Correlation with Performance: Log the user's task accuracy and reaction time. Statistically correlate these performance metrics with the computed attention and fatigue parameters across the session timeline [20].

Protocol 2: Assessing the Impact of Stress via Frontal Alpha Asymmetry

Objective: To evaluate user stress levels during BCI operation and determine their correlation with signal quality.

Methodology:

- Baseline Recording: Before the BCI task, record a 5-minute resting-state EEG with eyes open.

- Asymmetry Calculation: For the baseline and throughout the subsequent BCI task, compute the Frontal Alpha Asymmetry index. Extract alpha power from F3 and F4. The formula is:

Asymmetry = ln(Right_Alpha_Power) - ln(Left_Alpha_Power)[20]. - Task Administration: Conduct a BCI task known to induce mild cognitive load (e.g., a difficult P300 spelling task or a multi-class motor imagery task).

- Data Analysis: Calculate the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the event-related potentials (ERPs) or the feature separability for motor imagery trials.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform a regression analysis to determine if the Frontal Alpha Asymmetry index (as an indicator of stress) is a significant predictor of the trial-by-trial SNR [20].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Physiology Impact on BCI Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Analytical Tools for BCI Physiology Research

| Research 'Reagent' / Tool | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| High-Density EEG Systems | Provides the raw electrophysiological data. Essential for calculating power spectra in specific frequency bands (theta, alpha, beta, gamma) linked to physiological states [20]. |

| Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) | A signal processing algorithm used to find spatial filters that maximize the variance of one class while minimizing the variance of another. Crucial for feature extraction in motor imagery BCIs before classification [5]. |

| Frontal Alpha Asymmetry Index | A calculated metric (ln(F4alpha) - ln(F3alpha)) that serves as a biomarker for affective state and stress. A negative value is associated with stress responses and negative emotions [20]. |

| Passive BCI Framework | A software framework (e.g., BCI-HIL) that runs in parallel to an active BCI. It passively monitors the user's cognitive state (attention, fatigue, stress) to provide real-time context and enable system adaptation [20] [23]. |

| Deep Learning Architectures (CNN-LSTM with Attention) | A class of machine learning models. CNNs extract spatial features from EEG channels, LSTMs model temporal dynamics, and attention mechanisms weight the most salient features in time and space, leading to high classification accuracy (>97%) in MI-BCIs [5]. |

Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technology represents a direct communication pathway between the brain and an external device. For researchers working to enhance BCI accuracy, the fundamental decision revolves around choosing between invasive and non-invasive approaches, each presenting a distinct trade-off between signal fidelity and safety/practicality. Invasive BCIs, which involve surgical implantation of electrodes, provide high-resolution signals from specific neural populations but carry surgical risks and long-term biocompatibility challenges [24] [4]. Non-invasive BCIs, primarily using technologies like electroencephalography (EEG), are safer and more accessible but suffer from attenuated signals and limited spatial resolution due to the skull's filtering effect [24] [25]. This technical support document provides a structured analysis of this trade-off, offering troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols to assist researchers in optimizing BCI systems for accuracy enhancement within their specific research constraints.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Invasive vs. Non-Invasive BCI Technologies

| Feature | Invasive BCI (e.g., ECoG, Intracortical) | Non-Invasive BCI (e.g., EEG) |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Very High (Micrometer to millimeter scale) [4] | Low (Centimeter scale) [24] |

| Temporal Resolution | Very High (Milliseconds) [4] | High (Milliseconds) [24] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | High [4] | Low, requires significant amplification [24] [4] |

| Typical Signal Types | Action Potentials, Local Field Potentials (LFP) [4] | EEG, Sensorimotor Rhythms, Event-Related Potentials [24] [25] |

| Risk Level | High (Surgery, infection, tissue scarring) [24] [8] | Very Low/None [24] |

| Long-Term Stability | Challenges with biocompatibility and signal drift over time [8] | Generally stable, but susceptible to varying artifacts [24] |

| Primary Applications | Restoring speech [26], dexterous prosthetic control [21] | Rehabilitation [27], basic assistive control, neurofeedback [25] |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Recent clinical trials and meta-analyses provide concrete data on the performance capabilities of both invasive and non-invasive BCI paradigms. The following table summarizes key quantitative benchmarks essential for researchers designing accuracy-enhancement experiments.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks for Key BCI Applications

| Application | BCI Type | Reported Performance Metric | Key Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speech Decoding | Invasive (Intracortical) | Up to 99% word accuracy, ~56 words/minute [26] [21] | Chronic, at-home use in ALS patients [26] |

| Robotic Hand Control (Individual Fingers) | Non-Invasive (EEG) | 80.56% accuracy (2-finger), 60.61% accuracy (3-finger) [25] | Real-time control using motor imagery in able-bodied subjects [25] |

| Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation | Non-Invasive (EEG) | Significant improvement in motor (SMD=0.72) & sensory (SMD=0.95) function [27] | Meta-analysis of 109 patients; medium level of evidence [27] |

| Somatosensory Touch Restoration | Invasive (Intracortical Microstimulation) | Safe and effective over 10+ years in human subjects [21] | Long-term safety profile established over 24 combined patient-years [21] |

Experimental Protocols for BCI Accuracy Enhancement

Protocol: Real-Time Non-Invasive Robotic Finger Control via EEG

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 study, details a methodology for achieving individual finger-level control using EEG, a significant challenge in non-invasive BCI research [25].

- Objective: To enable real-time control of a robotic hand at the individual finger level using movement execution (ME) and motor imagery (MI) of individual fingers, decoded from scalp EEG signals.

- Subject Preparation: Recruit subjects with previous BCI experience to reduce training time. Apply a high-density EEG cap according to the 10-20 system. Ensure proper electrode-skin contact impedance is below 10 kΩ.

- Task Paradigm: Subjects perform executed or imagined movements of individual fingers (e.g., thumb, index, pinky) on their dominant hand in response to visual cues. Each trial consists of a rest period, a cue indicating the target finger, and the movement period.

- Signal Acquisition & Processing: Record continuous EEG data. Implement a deep learning decoder, specifically a variant of EEGNet (a compact convolutional neural network), for real-time classification [25].

- Model Training & Fine-Tuning:

- Base Model Training: Train an initial subject-specific model using data from an offline session.

- Online Fine-Tuning: During subsequent online sessions, use data from the first half of the session to fine-tune the base model. This adapts to inter-session variability and significantly enhances performance.

- Feedback & Control: Convert the decoder's output in real-time into two forms of feedback:

- Visual Feedback: On a screen, the target finger changes color (green/red) to indicate decoding correctness.

- Physical Feedback: A robotic hand physically moves the finger corresponding to the decoded class.

- Performance Validation: Evaluate performance using majority voting accuracy across trials for binary (e.g., thumb vs. pinky) and ternary (e.g., thumb vs. index vs. pinky) classification tasks.

Protocol: Chronic Intracortical BCI for High-Accuracy Speech Decoding

This protocol outlines the methodology behind award-winning research that achieved high-accuracy speech restoration, representing the state-of-the-art in invasive BCI [26] [21].

- Objective: To decode attempted speech from intracortical brain signals in individuals with severe paralysis (e.g., from ALS) and translate it into text or synthetic speech with high accuracy and speed.

- Surgical Implantation: Implant multiple microelectrode arrays (e.g., 4 arrays with 256 electrodes total) into the ventral precentral gyrus, a key speech-related area of the motor cortex, via the BrainGate2 or similar clinical trial platform [26] [21].

- Signal Acquisition: Record neural activity from hundreds of channels simultaneously. The high signal-to-noise ratio of intracortical signals is critical for decoding complex articulatory movements.

- Neural Decoder Setup: Employ advanced machine learning algorithms to map neural firing patterns to intended phonemes, words, or articulatory features. The decoder must be calibrated to the individual's unique neural patterns.

- Long-Term Stability Measures:

- Decoder Stability: Implement a calibration protocol that does not require daily recalibration. The system should maintain performance over years of continuous, at-home use [21].

- Hardware Biocompatibility: Monitor for tissue response and electrode degradation over time. Recent data shows some arrays can remain functional for over a decade [21].

- Outcome Metrics: Measure accuracy as the percentage of correctly outputted words in controlled tests. Also measure communication rate in words-per-minute and assess qualitative outcomes like independent computer use for work and social communication [26] [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for BCI Research

| Item | Function in BCI Research |

|---|---|

| High-Density EEG Cap with Ag/AgCl Electrodes | The standard sensor for non-invasive signal acquisition. High density improves spatial resolution for tasks like finger decoding [25]. |

| Microelectrode Arrays (e.g., Utah Array) | Implantable cortical sensors for invasive BCI. Provide high-fidelity recordings of single-unit and multi-unit activity [8]. |

| Deep Learning Software Stack (e.g., EEGNet, CNNs) | For feature extraction and classification of neural signals. Critical for decoding complex patterns from noisy EEG data [25]. |

| Robotic Hand or Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) System | Acts as the effector, providing physical feedback and restoring function. Essential for closed-loop motor rehabilitation studies [27] [25]. |

| Intracortical Microstimulation (ICMS) System | Provides artificial sensory feedback by stimulating the somatosensory cortex, creating a bidirectional BCI and improving prosthetic control dexterity [21]. |

| Magnetomicrometry Sensors | A less invasive method for measuring real-time muscle mechanics by tracking implanted magnets, offering an alternative control signal for neuroprosthetics [21]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: How can we mitigate the low spatial resolution of non-invasive EEG for decoding fine motor tasks like individual finger movements?

- Answer: The overlapping neural representations of individual fingers make this a significant challenge. The most effective solution involves combining advanced signal processing with modern machine learning.

- Use High-Density EEG Arrays: Increasing the number of electrodes (e.g., 64 or 128 channels) provides better spatial sampling of the neural signals originating from the densely packed hand area of the motor cortex.

- Implement Deep Learning Decoders: Replace traditional feature extraction and classification methods (e.g., common spatial patterns with linear discriminant analysis) with convolutional neural networks like EEGNet. These networks can automatically learn hierarchical and dynamic representations from raw or pre-processed EEG signals, capturing subtle, non-linear patterns that distinguish one finger's activity from another [25].

- Employ Real-Time Model Fine-Tuning: To combat inter-session variability, do not rely on a static decoder. Use data from the beginning of each experimental session to fine-tune the pre-trained model. This hybrid approach, combining general feature learning with session-specific adaptation, has been shown to significantly boost online performance [25].

FAQ 2: What are the primary causes of signal degradation in chronic invasive BCI implants, and how can we address them?

- Answer: Long-term signal degradation is a major hurdle for the clinical viability of invasive BCIs. The causes are multifaceted, but research has identified key factors and potential solutions.

- Cause 1: Biological Encapsulation. The body's immune response leads to glial scarring (gliosis) around the implant, insulating the electrodes and attenuating the recorded neural signals [8].

- Mitigation Strategy: Investigate new biomaterials and electrode designs that minimize the immune response. Neuralace (Blackrock Neurotech), a flexible lattice array, and Layer 7 (Precision Neuroscience), an ultra-thin surface array, are examples of next-generation devices designed to be more biocompatible and cause less tissue damage than rigid, penetrating arrays [8].

- Cause 2: Electrode Failure or Material Degradation. Physical damage to the electrodes or their insulating layers can occur over time.

- Mitigation Strategy: Rigorous in-vivo and accelerated lifetime testing of materials. Improve packaging and interconnection technology to ensure long-term stability. Recent data on intracortical microstimulation for sensory feedback shows that more than half of electrodes can remain functional for up to 10 years, proving long-term viability is achievable [21].

- Cause 1: Biological Encapsulation. The body's immune response leads to glial scarring (gliosis) around the implant, insulating the electrodes and attenuating the recorded neural signals [8].

FAQ 3: Our non-invasive BCI system is highly susceptible to artifacts from muscle movement (EMG) and eye blinks (EOG). What are the best practices for artifact removal?

- Answer: Artifact contamination is a fundamental limitation of non-invasive BCIs. A multi-layered approach is necessary.

- Experimental Design: Instruct participants to minimize head and body movements during trials. Use a chin rest if possible. For eye blinks, schedule short breaks to avoid buildup of ocular artifacts.

- Hardware and Pre-processing:

- Use high-quality amplifiers with appropriate hardware filters.

- Employ Independent Component Analysis (ICA), a blind source separation technique, to identify and remove components of the EEG signal that correlate strongly with artifact sources (e.g., EOG and EMG channels). This is a standard and effective method for cleaning EEG data.

- Leverage Robust Decoders: Choose machine learning models that are less sensitive to artifacts. Deep learning architectures, with their multiple layers of non-linear processing, can sometimes learn to ignore non-stationary artifacts if trained on a sufficiently large and varied dataset that includes such artifacts [25].

FAQ 4: How can we achieve a stable, high-performance BCI system that does not require daily recalibration, especially for invasive systems?

- Answer: The need for frequent recalibration is a major usability bottleneck. Stability is being addressed at both the hardware and algorithm levels.

- Algorithmic Stability: Develop adaptive decoders that can track slow, non-stationary changes in neural signals without full recalibration. Research has demonstrated that implanted speech BCIs can maintain over 99% accuracy over two years of at-home use without needing daily recalibration, showing this is feasible [21]. This involves creating algorithms that can distinguish between true neural signal drift and short-term variability.

- Neural Stability: Focus on recording from stable neural sources. For speech BCIs, the ventral precentral gyrus has been shown to produce highly stable command signals for articulation over years, even in progressive diseases like ALS [21]. Choosing the correct neural population to decode from is as important as the decoder itself.

BCI Signaling Pathway & Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core, closed-loop workflow common to both invasive and non-invasive BCI systems, highlighting the stages where key trade-offs and troubleshooting points occur.

Diagram 1: Core BCI Closed-Loop Workflow and Key Decision Points. This flowchart outlines the universal stages of a BCI system, with the first step (Signal Acquisition) highlighting the fundamental trade-off between the high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of invasive approaches and the safety of non-invasive methods. The feedback loop is critical for user adaptation and system accuracy.

The Role of the Visual System and Neural Pathways in Evoked Potentials

FAQs: Visual Evoked Potentials (VEPs) and Neural Pathways

Q1: What is a Visual Evoked Potential (VEP) and what does it measure? A: A Visual Evoked Potential (VEP) is an electrical signal generated by the visual cortex in response to visual stimulation [28]. It represents the expression of the electrical activity of the entire visual pathway, from the optic nerve to the calcarine cortex [29]. This signal provides a non-invasive method to explore the functionality of the human visual system, detecting neuronal pool activity independently of the patient's state of consciousness or attention [29] [28].

Q2: What is the primary clinical application of VEPs in neurological disorders? A: The most common clinical application of VEPs is in the diagnosis and monitoring of multiple sclerosis (MS) [29] [28]. In demyelinating conditions like MS, which often affects the optic nerve (optic neuritis), the VEP test shows a characteristic delay in the latency of the P100 waveform, even after the full recovery of visual acuity [29] [28]. VEPs are also used for other optic neuropathies, compressive pathway issues, and to rule out malingering [29] [30].

Q3: What are the main types of VEP stimuli used? A: The three main types, as standardized by the International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV), are [30]:

- Pattern Reversal VEP: The most common type for studying neurological pathologies, using a reversing checkerboard pattern with constant average luminance [29] [30].

- Pattern Onset/Offset VEP: A checkerboard pattern appears and disappears on a diffuse gray background [30].

- Flash VEP: Uses a diffuse flash stimulus, though it is less sensitive and more variable than pattern VEPs for assessing visual pathway integrity [29] [30].

Q4: How are VEPs used in the context of Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) research? A: While VEPs are a clinical diagnostic tool, the broader field of evoked potentials is fundamental to BCI research. BCIs can use visual evoked potentials as a reliable brain signal to control external devices [26]. Furthermore, advances in signal processing techniques, such as Cross-Frequency Coupling (CFC) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) for feature extraction and channel selection, are directly transferable from motor imagery-based BCIs to improve the accuracy and robustness of all brain-signal classification systems, including those that might use VEPs [31].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common VEP Experimental Challenges

Table: Common VEP Issues and Solutions

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution / Verification Step |

|---|---|---|

| Poor waveform reproducibility | Uncorrected refractive error, poor patient focus/fixation, improper electrode contact. | Ensure patient's refractive error is corrected for the testing distance; check electrode impedance; encourage patient to focus on the fixation target [28] [30]. |

| Abnormally prolonged P100 latency | Demyelination of the optic nerve (e.g., Multiple Sclerosis, Optic Neuritis) [29] [28]. | Confirm patient history and clinical presentation; compare results to lab-specific normative data; consider neurological consultation. |

| Reduced P100 amplitude with normal latency | Axonal damage or compression of the visual pathway, ischemic optic neuropathy [29] [28]. | Investigate for potential compressive lesions or other causes of axonal loss; ensure proper stimulus contrast and luminance. |

| Asymmetric responses from occipital electrodes (O1, Oz, O2) | Retrochiasmal pathway dysfunction (e.g., post-chiasmal lesions) [30]. | Utilize multi-channel recording protocols; a crossed asymmetry suggests chiasmal disorder, while an uncrossed asymmetry suggests retrochiasmal dysfunction [30]. |

| Unusually noisy or flat signal | High electrode impedance, muscle artifact, patient blinking. | Reapply electrodes to ensure impedance is below 5 kΩ; instruct the patient to relax and blink less; use an artifact rejection algorithm in the acquisition software. |

Experimental Protocols for Key VEP Assessments

Standardized Pattern Reversal VEP Protocol

This is the primary methodology for assessing the anterior visual pathway (pre-chiasmatic) [30].

- Patient Preparation: Pupils should be undilated, and any significant refractive error must be corrected for the testing distance. Testing is performed on one eye at a time (uniocular) with the other eye patched [30].

- Electrode Placement: As per the international 10-20 system [29] [30].

- Active Electrode: Placed at the midline occipital position (Oz).

- Reference Electrode: Placed on the forehead (Fz).

- Ground Electrode: Placed on the earlobe, vertex, or mastoid.

- Stimulus Parameters:

- Type: Pattern reversal (checkerboard).

- Check Sizes: Both large (1 degree) and small (0.25 degree) checks should be used [30].

- Field Size: Should subtend at least 20 degrees of the visual field.

- Contrast: Typically high contrast (>80%).

- Luminance: Constant average luminance.

- Temporal Frequency: ~2 reversals per second (rps) for a "transient" VEP response [30].

- Waveform Analysis: The characteristic waveform consists of N75, P100, and N135 peaks. The P100 latency and amplitude (from N75 peak to P100 peak) are the most critical and stable parameters for clinical interpretation [29] [30].

Multi-Channel VEP Protocol for Chiasmal and Retrochiasmal Assessment

This extended protocol is used to evaluate lesions beyond the optic chiasm [30].

- Patient & Stimulus Preparation: Follows the same standards as the standard pattern reversal VEP.

- Electrode Placement:

- Multiple Active Electrodes: Placed at Oz, O1 (left occipital), O2 (right occipital), and optionally at PO7 and PO8.

- Reference Electrode: Remains on the forehead (Fz).

- Data Interpretation: The analysis focuses on the distribution of the VEP response across the occipital scalp.

- Chiasmal Lesions (e.g., pituitary adenoma) cause a crossed asymmetry.

- Retrochiasmal Lesions (e.g., optic tract damage) cause an uncrossed asymmetry [30].

Visualizing the VEP Pathway and Experimental Workflow

VEP Neural Signaling Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the anatomical pathway of the visual signal from the eye to the visual cortex, which is measured by the VEP.

VEP Experimental Workflow

This diagram outlines the standard workflow for conducting a VEP experiment, from patient preparation to data interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for VEP Experiments

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| EEG Recording System with Ag/AgCl Electrodes | Essential for high-fidelity recording of scalp electrical potentials. Ag/AgCl electrodes are non-polarizable and provide stable signals [29] [28]. |

| Electrode Gel & Skin Abrasion Prep | Reduces skin-electrode impedance, which is critical for obtaining a clean signal with minimal noise. |

| Pattern Stimulator (Monitor/Goggles) | Provides the standardized visual stimulus (e.g., reversing checkerboard). Must control for check size, luminance, contrast, and reversal rate [29] [30]. |

| Signal Averaging Software | The VEP signal is embedded within the background EEG noise. Averaging multiple responses to repeated stimuli enhances the signal-to-noise ratio, allowing the VEP waveform to emerge [28]. |

| Multi-Channel Capability | For assessments beyond the anterior visual pathway (chiasmal/post-chiasmal), the ability to record from multiple occipital sites (O1, Oz, O2, PO7, PO8) is mandatory [30]. |

Advanced Methods and Algorithms for Improving BCI Performance

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using a bimodal motion-color SSMVEP paradigm over traditional SSVEP? Bimodal motion-color SSMVEP paradigms significantly enhance performance and user comfort compared to traditional flicker-based SSVEP. The key advantages are a substantial increase in classification accuracy and a stronger, more reliable brain response. Research shows the bimodal paradigm achieved the highest accuracy of 83.81% ± 6.52%, outperforming single-mode motion or color paradigms [32]. Furthermore, it provides an enhanced signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and reduces visual fatigue, as confirmed by both objective EEG measures and subjective user reports [32].

Q2: How does the bimodal stimulation enhance brain response intensity? Bimodal stimulation engages multiple specialized pathways in the human visual system simultaneously. The dorsal stream (M-pathway), specialized for motion detection, is activated by the expanding/contracting rings. Concurrently, the ventral stream (P-pathway), responsible for color and object identification, is activated by the color contrast [32]. This simultaneous activation of distinct neural populations results in a more robust cortical response and higher SNR than stimulating a single pathway alone [32].

Q3: What is the role of "equal luminance" in the color stimuli, and how is it achieved?

Maintaining equal luminance between the alternating colors (e.g., red and green) is critical to minimize flicker perception and the resulting visual fatigue. Flicker sensitivity in the eyes is diminished when visual stimuli use two colors with equal brightness [32]. The perceived luminance is calculated and balanced using a standard formula: L(r,g,b) = C1(0.2126R + 0.7152G + 0.0722B), where C1 is a device-specific constant, and R, G, B are the color values. This ensures the color transitions are smooth and do not introduce intensity-based flicker [32].

Q4: My setup is yielding low classification accuracy. What are the key parameters I should optimize? Low accuracy can often be traced to suboptimal stimulation parameters. You should systematically investigate the following key variables, which were optimized in the referenced study [32]:

- Color-Brightness Combination: Test different combinations (e.g., Red-Green).

- Brightness Level: Experiment with low (L), medium (M), and high (H) settings.

- Area Ratio (C): Adjust the area ratio between the rings and the background, with 0.6 being a high-performing value.

- Stimulus Frequency: Ensure the motion and color reversal frequencies are set to your target (e.g., 12 Hz).

Q5: Participants report high visual fatigue during my SSMVEP experiment. How can I mitigate this?

The bimodal motion-color paradigm was explicitly designed to reduce fatigue. To mitigate fatigue, ensure you are using an equal-luminance color contrast to avoid flicker. Additionally, employ a smooth, sinusoidal color transition (as defined by the R(t) = Rmax(1-cos(2πft)) function) instead of abrupt on/off flickering [32]. The expanding/contracting motion of Newton's rings is inherently less fatiguing than traditional flicker, and combining it with smooth color changes further enhances comfort [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Classification Accuracy or Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR)

A weak SSMVEP response makes it difficult for classification algorithms to distinguish between targets.

- Potential Cause: Suboptimal stimulation parameters.

- Solution: Refer to Table 1 and adjust your stimulus properties based on the published optimal configurations. Re-calibrate your setup to use the medium brightness (M) and an area ratio (C) of 0.6 [32].

- Potential Cause: Inefficient EEG processing pipeline.

- Solution: Implement advanced signal processing techniques. Consider using a cyclostationary (CS) analysis to first identify the frequency bands that contain the stimulus-related VEP components, as this technique does not require signals to be phase-locked [33]. Follow this with artifact reduction methods like a genetic algorithm combined with Independent Component Analysis (G-ICA) to separate noise from the neural signal [33].

- Potential Cause: Using a unimodal paradigm when a bimodal one is feasible.

- Solution: Transition from a single-motion or single-color SSVEP paradigm to a bimodal motion-color SSMVEP paradigm to leverage the synergistic effect on response intensity [32].

Issue 2: High User-reported Visual Fatigue and Discomfort

Participants find the visual stimulation unpleasant, leading to difficulty in sustaining the experiment.

- Potential Cause: Luminance imbalance in color stimuli causing perceived flicker.

- Solution: Rigorously calibrate your display device to ensure the alternating colors (e.g., red and green) have equal perceived luminance using the formula

L(r,g,b) = C1(0.2126R + 0.7152G + 0.0722B)[32].

- Solution: Rigorously calibrate your display device to ensure the alternating colors (e.g., red and green) have equal perceived luminance using the formula

- Potential Cause: Abrupt stimulus transitions.

- Solution: Implement a smooth, sinusoidal modulation for color changes as defined in the stimulation design, rather than using square-wave onsets and offsets [32].

- Potential Cause: Overly intense brightness or contrast settings.

- Solution: Optimize brightness levels. The research found that a medium brightness level was part of the optimal configuration that balanced high accuracy with user comfort [32].

The following workflow details the core methodology for establishing a bimodal SSMVEP-BCI experiment as described in the research [32].

Detailed Methodology

1. Stimulus Design & Presentation

- Visual Paradigm: The stimulus consists of multiple "Newton's rings" that undergo simultaneous motion and color changes.

- Motion Component: The rings expand outward and contract inward rhythmically at a steady-state frequency (e.g., 12 Hz) [32].

- Bimodal Component: While moving, the rings smoothly alternate between two colors (e.g., red and green) at the same frequency. The color transition is governed by a sine wave:

R(t) = Rmax(1-cos(2πft))to ensure smoothness [32]. - Key Parameters:

2. EEG Data Acquisition

- Participants: Recruit subjects with normal or corrected-to-normal vision.

- Electrode Placement: Record from six electrodes over the parietal and occipital lobes: Po3, Poz, Po4, O1, Oz, O2, according to the international 10-20 system [32].

- Equipment & Settings: Use a biosignal amplifier (e.g., g.USBamp) with a sampling rate of 1200 Hz. Reference to one earlobe and ground at Fpz. Keep electrode impedances below 5 kΩ [32].

3. Signal Processing

- Filtering: Apply an 8th-order Butterworth band-pass filter (2-100 Hz) and a 4th-order notch filter (48-52 Hz) to remove line noise [32].

- Analysis: Use Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to analyze response intensity and SNR in the frequency domain. For classification, employ a deep learning model such as EEGNet [32].

Table 1: Optimal Stimulation Parameters for Bimodal SSMVEP

This table consolidates the key parameters that were experimentally determined to yield the highest performance [32].

| Parameter | Description | Optimal Value(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Paradigm Type | Integration of motion and color stimuli | Bimodal (Motion + Color) |

| Accuracy | Highest reported classification accuracy | 83.81% ± 6.52% |

| Brightness Level | Luminance intensity of the stimulus | Medium (M) |

| Area Ratio (C) | Ratio of ring area to background area | 0.6 |

| Color Combination | Pair of alternating colors with equal luminance | Red-Green |

| Color Transition | Function governing color change over time | Sine Wave R(t) = Rmax(1-cos(2πft)) |

| Primary Benefit | Key advantage over traditional SSVEP | Enhanced SNR & Reduced Visual Fatigue |

Table 2: Core Neurophysiological Pathways in Bimodal SSMVEP

This table outlines the neural pathways targeted by the bimodal paradigm, explaining the physiological basis for its enhanced performance [32].

| Visual Pathway | Alternative Name | Primary Function | Stimulus Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dorsal Stream | M-pathway | Motion detection, spatial analysis, velocity/direction | Expanding/Contracting Rings |

| Ventral Stream | P-pathway | Color vision, object identification, luminance | Red-Green Color Alternation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Experimental Setup

This table lists the key hardware, software, and analytical tools required to replicate the bimodal SSMVEP-BCI setup.

| Item | Function / Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| AR Glasses or LCD Monitor | Presents the visual stimulus to the user. Must support the required refresh rate (e.g., 60 Hz) and precise color control [32] [34]. |

| Biosignal Amplifier (e.g., g.USBamp, g.HIamp) | Acquires raw EEG signals from the scalp at a high sampling rate (≥256 Hz) and high resolution [32] [34]. |

| EEG Electrodes & Cap | Records brain activity from the occipital and parietal regions. A 6-channel setup (Po3, Poz, Po4, O1, Oz, O2) is typical [32]. |

| Newton's Rings Stimulus Software | Custom software to generate the bimodal paradigm: concentric rings with simultaneous motion and smooth color alternation [32]. |

| Signal Processing Toolkit (MATLAB, Python) | Environment for implementing pre-processing filters (Butterworth band-pass/notch), FFT analysis, and classification algorithms like EEGNet [32] [33]. |

| Cyclostationary Analysis & G-ICA | Advanced algorithms for identifying stimulus-related frequency bands and removing artifacts to enhance SNR, useful for troubleshooting low accuracy [33]. |

Signaling Pathways in Bimodal Visual Evoked Potentials

The enhanced performance of the bimodal paradigm is grounded in its simultaneous engagement of two major visual processing pathways, as illustrated below.

Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technology has ushered in a new era of human-technology interaction by establishing a direct communication pathway between the human brain and external devices [35] [36]. Within this domain, motor imagery electroencephalography (MI-EEG) signals are particularly valuable for inferring users' intentions during mental rehearsal of movements without physical execution [35]. The accurate classification of these signals is paramount for applications ranging from rehabilitation training and prosthetic control to device control and communication systems for paralyzed individuals [35] [26]. Despite significant potential, BCI systems face substantial challenges in accurately interpreting users' intentions due to the non-stationary nature of EEG signals, inter-subject variability, and susceptibility to artifacts [35] [36].

Recent advancements in deep learning have dramatically improved the decoding capabilities of EEG-based systems [37]. Unlike traditional machine learning approaches that require handcrafted feature extraction, deep learning models can automatically learn relevant features from raw data, offering strong nonlinear fitting capabilities that effectively handle the complex characteristics of EEG signals [35] [38]. However, the transition from laboratory settings to real-world clinical and consumer applications depends heavily on enhancing both the accuracy and interpretability of these models [37] [39]. This technical support center document addresses these critical needs by providing detailed troubleshooting guidance, architectural insights, and experimental protocols for implementing state-of-the-art deep learning architectures in EEG classification, with a specific focus on enhancing BCI accuracy for research applications.

Key Deep Learning Architectures for EEG Classification

EEGNet is a compact convolutional neural network architecture specifically designed for EEG data classification across various BCI paradigms [35] [40]. Its lightweight design employs temporal convolutional filters, depthwise spatial filters, and separable convolutional blocks, making it particularly suitable for EEG analysis with a relatively small parameter footprint [40]. The architecture incorporates weight constraints, batch normalization, and dropout to improve training stability and model generalization [40]. EEGNet has demonstrated strong performance in multiple EEG classification tasks, achieving approximately 0.82 accuracy on the PhysioNet EEG Motor Movement/Imagery dataset [38].

CIACNet (Composite Improved Attention Convolutional Network) represents a more recent advancement for MI-EEG signal classification [35] [36]. This architecture utilizes a dual-branch convolutional neural network (CNN) to extract rich temporal features, an improved convolutional block attention module (CBAM) to enhance feature extraction, and a temporal convolutional network (TCN) to capture advanced temporal features [35]. The model employs multi-level feature concatenation for more comprehensive feature representation and has demonstrated strong classification capabilities with relatively low time cost [35] [36]. Experimental results show that CIACNet achieves accuracies of 85.15% and 90.05% on the BCI IV-2a and BCI IV-2b datasets, respectively, with a kappa score of 0.80 on both datasets [35] [36].

Hybrid Architectures have also emerged as powerful approaches for EEG decoding. The EEGNet-LSTM model combines convolutional layers from EEGNet with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) recurrent networks, achieving approximately 23% better performance than competition-winning decoders on Dataset 2a from BCI Competition IV [38]. Similarly, ATCNet integrates multi-head self-attention (MSA), TCN, and CNN to decode MI-EEG signals, while MSATNet combines a dual-branch CNN and Transformer architecture [35].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Architectures on Standard EEG Datasets

| Architecture | BCI IV-2a Accuracy | BCI IV-2b Accuracy | PhysioNet Accuracy | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEGNet | - | - | 0.82 [38] | Compact CNN, temporal & spatial filters, separable convolutions [40] |

| CIACNet | 85.15% [35] [36] | 90.05% [35] [36] | - | Dual-branch CNN, improved CBAM, TCN, multi-level feature concatenation [35] |

| EEGNet-LSTM | ~23% improvement over winning BCI Competition IV entry [38] | - | 0.85 [38] | Combination of EEGNet convolutional layers with LSTM recurrent layers [38] |

| TCNet-Fusion | - | - | - | Enhanced EEG-TCNet through feature concatenation [35] |

| EEG-ITNet | - | - | - | Tri-branch structure combining CNN and TCN [35] |

Table 2: Architectural Components and Their Contributions to Model Performance

| Architectural Component | Function | Impact on Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN) | Captures advanced temporal features using causal and dilated convolutions [35] | Enhances sequence modeling and temporal dependencies [35] |

| Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) | Dynamically emphasizes important features across both channel and spatial domains [35] | Improves feature discrimination and model focus [35] |

| Dual/Tri-Branch Architecture | Extracts complementary features through multiple pathways [35] | Provides more comprehensive feature representation [35] |

| Multi-level Feature Concatenation | Combines features from different network depths [35] | Preserves both low-level and high-level features [35] |

| Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) Blocks | Models channel-wise relationships [35] | Enhances informative feature channels [35] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Experimental Pipeline for EEG Classification

Detailed Implementation Protocols

Data Preprocessing Pipeline: EEG data must undergo comprehensive preprocessing before model training to remove noise and artifacts. The standard protocol includes: (1) Filtering using notch filters (e.g., 50/60 Hz for power line interference) and bandpass filters appropriate for the task (e.g., 8-30 Hz for motor imagery); (2) Artifact rejection to remove contamination from eye blinks, eye movements, muscle activity, and other external factors using automated detection methods or visual inspection; (3) Referencing to a common average or specific electrodes to minimize spatial biases; and (4) Epoching to extract segments time-locked to specific events or stimuli [41].

Feature Extraction Methodologies: While deep learning models can automatically learn features, understanding traditional approaches provides valuable insights: (1) Power Spectral Density (PSD) estimates power distribution across frequency bands (delta, theta, alpha, beta, gamma) using Fourier transforms; (2) Time-frequency analysis using wavelet transforms reveals changes in EEG power over time and across frequency bands; (3) Event-Related Potentials (ERPs) are extracted by averaging EEG epochs time-locked to specific stimuli; and (4) Spatial filtering techniques like Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) enhance discriminability between classes [41].

Model Training and Validation: Robust training strategies are critical for success: (1) Implement subject-specific, cross-subject, or subject-independent training paradigms based on research goals; (2) Apply appropriate data augmentation techniques such as sliding window cropping, adding Gaussian noise, or magnitude warping; (3) Utilize stratified k-fold cross-validation to ensure representative distribution of classes across splits; (4) Employ early stopping with patience based on validation performance to prevent overfitting; and (5) Conduct statistical significance testing (e.g., Wilcoxon signed-rank test) to validate performance differences between models [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Tools and Datasets for EEG Classification Research

| Resource | Type | Purpose/Function | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCI Competition IV Dataset 2a | Benchmark Dataset | 4-class motor imagery data from 9 subjects, 22 channels [35] [38] | Publicly Available |

| BCI Competition IV Dataset 2b | Benchmark Dataset | 2-class motor imagery data from 9 subjects, 3 channels [35] [36] | Publicly Available |

| PhysioNet Motor Movement/Imagery Dataset | Benchmark Dataset | 109 subjects, 64-channel EEG during motor tasks [38] | Publicly Available |

| Mass General Hospital ICU EEG Dataset | Clinical Dataset | 50,697 EEG samples with expert annotations for harmful brain activities [39] | Restricted Access |

| Neuroelectrics Enobio | Hardware | Wireless EEG system for data acquisition [41] | Commercial |

| EEGNet Implementation | Software | Compact CNN architecture for EEG classification [40] | Open Source |

| DeepLift | Software | Explainability method for interpreting model decisions [37] | Open Source |

| ProtoPMed-EEG | Software | Interpretable deep learning model for EEG pattern classification [39] | Research Implementation |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Performance and Optimization Issues

Q: My model achieves high training accuracy but poor test performance. What could be the cause? A: This typically indicates overfitting. Solutions include: (1) Increasing dropout rates (EEGNet typically uses 0.25-0.5 dropout [40]); (2) Applying stronger data augmentation techniques such as sliding window cropping or adding Gaussian noise; (3) Implementing L2 weight regularization with values between 0.0001-0.01; (4) Reducing model complexity if working with limited data; (5) Ensuring proper cross-validation procedures where data from the same subject isn't split across training and test sets [38].

Q: How can I improve classification accuracy for motor imagery tasks? A: Based on recent research: (1) Implement multi-branch architectures like CIACNet that capture complementary temporal and spatial features [35]; (2) Incorporate attention mechanisms (CBAM, SE) to help the model focus on relevant features [35]; (3) Utilize temporal convolutional networks (TCN) for better sequence modeling [35]; (4) Experiment with multi-level feature concatenation to preserve both low-level and high-level information [35]; (5) Ensure optimal hyperparameter tuning through systematic search of learning rates (0.0001-0.001), batch sizes (64-256), and filter sizes [40].