EEG vs. ECoG for BCI: A Comprehensive Analysis of Signal Quality, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of Electroencephalography (EEG) and Electrocorticography (ECoG) for Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) applications, tailored for researchers and biomedical professionals.

EEG vs. ECoG for BCI: A Comprehensive Analysis of Signal Quality, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of Electroencephalography (EEG) and Electrocorticography (ECoG) for Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) applications, tailored for researchers and biomedical professionals. We explore the foundational principles governing the signal quality of these non-invasive and semi-invasive modalities, examining their inherent trade-offs in spatial resolution, signal-to-noise ratio, and invasiveness. The scope extends to methodological advancements and specific applications in rehabilitation, communication, and neurosurgery, addressing critical troubleshooting aspects such as signal stability and computational optimization. Finally, we present a rigorous validation and comparative framework, synthesizing performance metrics and emerging trends to inform future development in neurotechnology and clinical practice.

Fundamental Principles: Unpacking the Core Technologies of EEG and ECoG

Electroencephalography (EEG) and electrocorticography (ECoG) represent two fundamental approaches to measuring electrical activity generated by the human brain, each occupying a distinct position on the spectrum of invasiveness and signal fidelity. As core technologies for brain-computer interface (BCI) development, these modalities enable direct communication pathways between the brain and external devices by translating neural signals into executable commands [1]. The divergence in their technical implementation—with EEG employing scalp-mounted electrodes and ECoG utilizing electrodes placed directly on the cortical surface—creates a significant trade-off between practical accessibility and signal quality that researchers must carefully navigate [2] [3].

EEG's non-invasive nature makes it widely accessible for both research and clinical applications, while ECoG's semi-invasive approach provides superior signal characteristics at the cost of requiring surgical implantation [4]. This technical dichotomy positions these modalities for different applications within neuroscience research and clinical BCI implementation. Understanding their fundamental operational principles, technical capabilities, and inherent limitations is essential for selecting the appropriate tool for specific research questions or BCI applications, particularly as the field advances toward more sophisticated neural decoding and real-time interaction paradigms [1] [3].

Technical Specifications and Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Physical and Electrical Characteristics

The operational principles of EEG and ECoG stem from their distinct physical relationships with neural tissue, resulting in markedly different signal characteristics. EEG records the cumulative electrical activity of large neuronal populations through electrodes placed on the scalp surface, with signals attenuated and spatially smeared by intervening tissues including the skull, cerebrospinal fluid, and various meningeal layers [2] [3]. This biological filtering effect significantly reduces signal amplitude and spatial resolution, with EEG typically capturing signals in the microvolt range (5-100 μV) that represent activity from cortical areas spanning several square centimeters [1] [3].

In contrast, ECoG electrodes are surgically implanted beneath the skull and placed directly on the pial surface of the brain, either through subdural grid placement or via depth electrodes targeting specific structures [5] [4]. This direct physical contact eliminates the signal-degrading effects of intermediary tissues, resulting in substantially higher signal-to-noise ratios (typically 5-10 times greater than EEG) and microvolt-level signals that more accurately reflect local neural dynamics [3]. The spatial resolution of ECoG is consequently superior to EEG, with the ability to resolve neural activity at the millimeter scale compared to EEG's centimeter-level resolution [4] [6].

Table 1: Physical and Signal Characteristics Comparison

| Characteristic | EEG (Non-invasive) | ECoG (Semi-invasive) |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Amplitude | 5-100 μV [3] | 50-500 μV [3] |

| Spatial Resolution | 2-3 cm [3] | 1-4 mm [6] [3] |

| Temporal Resolution | Millisecond-level [1] | Sub-millisecond [5] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Low (susceptible to artifacts) [3] | High (5-10x EEG) [3] |

| Primary Noise Sources | EMG, EOG, environmental interference [1] [3] | Cardiac, respiratory pulsation [3] |

Signal Stability and Practical Implementation Factors

Long-term signal stability represents a critical differentiator between EEG and ECoG, particularly for extended research protocols and chronic BCI applications. EEG signal quality demonstrates high variability across sessions due to inconsistent electrode placement, impedance fluctuations from skin-electrode interface changes, and susceptibility to environmental factors [3]. This variability necessitates frequent recalibration and signal processing adaptations to maintain performance, creating challenges for longitudinal studies and out-of-laboratory deployment [3].

ECoG exhibits superior session-to-session stability due to fixed electrode positions relative to cortical tissue, though long-term implantation presents unique challenges including tissue encapsulation around electrodes, potential material degradation, and chronic immune responses that can gradually degrade signal quality over months or years [3]. From a practical implementation perspective, EEG systems offer clear advantages in cost, accessibility, and setup simplicity, with research-grade systems typically costing $10,000-$50,000 and consumer-grade options available for $200-$2,000 [3]. ECoG systems command premium pricing between $50,000-$200,000 due to specialized electrode arrays, surgical implantation requirements, and custom amplification systems [3].

Table 2: Stability and Practical Implementation Comparison

| Factor | EEG | ECoG |

|---|---|---|

| Session-to-Session Stability | Highly variable [3] | High stability [3] |

| Long-Term Stability (Months) | Not applicable for chronic use | Signal deterioration possible [3] |

| System Cost | $10,000-$50,000 (research); $200-$2,000 (consumer) [3] | $50,000-$200,000 [3] |

| Implementation Requirements | Minimal training, portable systems [1] | Surgical team, hospital setting [5] [4] |

| Typical Application Environments | Research labs, clinics, home use [1] | Epilepsy monitoring units, operating rooms [5] [4] |

Experimental Methodologies and Applications

ECoG Experimental Protocols and Applications

ECoG research protocols typically leverage unique clinical opportunities, most commonly involving patients with drug-resistant epilepsy undergoing invasive monitoring for seizure focus localization [5] [4]. The standard implantation procedure involves surgical placement of electrode grids (typically 8×8 configurations with 4mm diameter electrodes and 1cm spacing) or strips directly on the cortical surface through a craniotomy, with precise positioning determined by clinical requirements [5]. During the subsequent 5-12 day monitoring period, researchers can conduct experiments during seizure-free intervals, with signals typically acquired at 1200Hz or higher sampling rates to accurately capture high-frequency neural activity [5].

Functionally, ECoG's high spatial and temporal resolution makes it particularly valuable for mapping fine-grained neural representations and decoding complex motor commands. The high gamma range activity (around 70-110 Hz) has proven especially informative as a robust indicator of local cortical function during motor execution, auditory processing, and visual-spatial attention tasks [5]. Real-time functional mapping techniques like SIGFRIED (SIGnal modeling For Realtime Identification and Event Detection) can identify task-responsive cortical areas by detecting significant ECoG activation changes, providing valuable information that complements traditional electrocortical stimulation mapping [5]. These capabilities enable sophisticated BCI applications including individual finger movement decoding [7], with ECoG providing the signal fidelity necessary for dexterous robotic control at the level of individual digits.

EEG Experimental Protocols and Applications

EEG experimental methodologies emphasize accessibility and non-invasiveness, employing standardized electrode placement systems (typically the 10-20 system or high-density variants) to ensure consistent positioning across subjects and sessions [8]. Signal acquisition is preceded by careful scalp preparation and electrode impedance checking to maximize signal quality, with data typically sampled at 256-512Hz for most BCI applications [1]. The preprocessing pipeline is particularly crucial for EEG, incorporating downsampling, artifact removal (for ocular, cardiac, and muscular contaminants), and feature scaling to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio despite substantial environmental and physiological interference [1].

Modern EEG-BCI research has demonstrated increasingly sophisticated capabilities, particularly with advances in deep learning decoding approaches. A notable 2025 study achieved real-time robotic hand control at the individual finger level using EEG signals associated with movement execution and motor imagery [7] [9]. This system utilized the EEGNet convolutional neural network architecture with fine-tuning mechanisms to decode intended finger movements, achieving binary classification accuracy of 80.56% for two-finger motor imagery tasks and 60.61% for three-finger tasks across 21 experienced BCI users [7] [9]. Such performance highlights the potential for non-invasive systems to support relatively dexterous control paradigms, though still lagging behind ECoG in precision and reliability. EEG-BCI applications span medical rehabilitation (stroke recovery, communication aids for ALS patients), cognitive monitoring, and increasingly, consumer domains including gaming and wellness applications [1] [3].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Methodologies and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Equipment

| Item | Function | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| ECoG Electrode Grids | Direct cortical signal acquisition | 8×8 configuration, 4mm diameter electrodes, 1cm spacing, platinum-iridium [5] |

| EEG Electrode Systems | Scalp-based signal acquisition | 10-20 system placement, Ag/AgCl electrodes, gel/water-based conduction [8] |

| g.USBamp Amplifiers | Signal amplification for ECoG | Safety-rated for invasive recordings, low noise-floor in high-frequency range [5] |

| BCI2000 Software Platform | Data acquisition and real-time analysis | General-purpose biosignal processing, supports ECoG and EEG [5] |

| EEGNet Architecture | Deep learning-based signal decoding | Convolutional neural network optimized for EEG-based BCIs [7] [9] |

| CURRY Software Package | Electrode localization and 3D modeling | Co-registers pre-operative MRI with post-implantation CT [5] |

Methodological Selection Framework

Choosing between EEG and ECoG methodologies requires careful consideration of research objectives, subject population, and practical constraints. ECoG is methodologically indicated when research demands high spatial resolution (<1cm) and signal-to-noise ratio, particularly for investigating high-frequency neural dynamics (gamma band activity), mapping functional organization at fine spatial scales, or developing BCIs requiring precise multi-dimensional control [5] [4] [6]. This approach is ethically and practically feasible primarily in clinical populations already undergoing invasive monitoring for medical reasons, most commonly patients with drug-resistant epilepsy requiring seizure focus localization [5] [4].

EEG represents the preferable methodology for studies prioritizing non-invasiveness, larger subject cohorts, repeated measurements over time, or ecological validity in naturalistic settings [1] [8]. Its applicability to both healthy and clinical populations, lower regulatory barriers, and recent performance improvements through advanced signal processing make it suitable for exploratory investigations, proof-of-concept BCI development, and applications where signal quality can be compensated for through trial averaging or population-level analyses [7] [1]. Hybrid approaches are increasingly valuable, using ECoG to establish ground truth neural signatures and developing analogous EEG markers that can be more readily measured in broader populations [6].

EEG and ECoG represent complementary rather than competing modalities in the neuroscience research arsenal, each offering distinct advantages constrained by their inherent limitations. ECoG provides unparalleled signal quality and spatial specificity for investigating fine-grained neural processes and developing high-performance BCIs, but its application is restricted to specific clinical contexts and requires substantial technical and surgical resources [5] [4] [3]. EEG offers broad accessibility and non-invasive operation at the cost of reduced signal fidelity, yet continues to demonstrate expanding capabilities through computational advances such as deep learning architectures [7] [9].

The future trajectory of both modalities points toward increasing integration rather than displacement, with ECoG establishing neural decoding benchmarks and EEG advancing toward more practical implementations. Technical innovations in electrode design, signal processing algorithms, and hybrid system integration will continue to push both modalities toward enhanced performance and expanded applications [3]. For researchers navigating this landscape, methodological selection must be guided by specific scientific questions, practical constraints, and the fundamental trade-off between signal quality and accessibility that continues to define the division between these foundational neural recording approaches.

The efficacy of any Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) system is fundamentally constrained by the quality of the neural signals it acquires. These signals originate from complex electrochemical processes within the brain and must be captured through various interfacing technologies, each with distinct trade-offs between signal fidelity, invasiveness, and practical implementation [10]. Understanding the physiological origins of these signals and the technical challenges in their acquisition is paramount for advancing BCI technologies for both clinical and research applications.

Electroencephalography (EEG) represents the most accessible non-invasive method, recording electrical activity from the scalp surface [11]. In contrast, electrocorticography (ECoG) involves surgical placement of electrodes directly on the cortical surface, providing superior signal quality but requiring invasive procedures [12] [5]. This technical guide examines the physiological basis of these signals, their acquisition methodologies, and the experimental protocols that enable researchers to quantify and compare their performance within BCI systems.

Physiological Origins of Brain Signals

Cellular Foundations and Neural Ensemble Activity

The electrical signals captured by both EEG and ECoG originate primarily from the summed postsynaptic potentials of cortical pyramidal cells [11]. When neurotransmitters bind to receptors on these neurons, ion channels open, creating transient current flows that generate electrical dipoles. While individual neuronal contributions are minuscule, the synchronous activity of thousands to millions of pyramidal cells aligned in parallel creates electrical fields potent enough to be detected externally [13].

These neural ensembles oscillate at characteristic frequencies that correlate with different brain states:

- Delta waves (1-4 Hz): Prominent during deep sleep

- Theta waves (4-8 Hz): Associated with drowsiness and meditation

- Alpha waves (8-13 Hz): Present during relaxed wakefulness, especially over occipital regions

- Beta waves (14-30 Hz): Related to active thinking, focus, and motor activity

- Gamma waves (30+ Hz): Involved in higher cognitive processing and sensory integration [11] [14]

The amplitude of these oscillations varies dramatically by recording method, with scalp EEG typically capturing signals in the microvolt (10⁻⁶ V) range, while ECoG can detect millisecond-scale temporal dynamics with much higher signal-to-noise ratios [5].

Signal Pathways From Cortex to Sensors

Table 1: Signal Attenuation Factors by Tissue Type

| Tissue Layer | Relative Conductivity | Impact on Signal Quality | Effect on Spatial Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cerebrospinal fluid | High | Minimal attenuation | Lowers spatial specificity |

| Skull | Very low | Significant attenuation (~90%) | Strong blurring effect |

| Scalp | Moderate | Additional attenuation | Further reduces resolution |

| Dura mater | Low | Moderate attenuation | Minor blurring effect |

As neural signals propagate from their cortical origins to external sensors, they traverse multiple tissue layers with different electrical properties [13]. The skull presents particularly high electrical resistance, acting as a strong low-pass filter that attenuates high-frequency components and spatially blurs the underlying cortical activity [12]. This fundamental biological constraint explains why non-invasive EEG struggles to capture high-frequency brain activity (>30 Hz) with precise spatial localization.

In contrast, ECoG electrodes positioned beneath the skull and dura mater avoid this significant signal degradation, enabling recording of rich high-gamma activity (70-110 Hz) that provides a robust indicator of local cortical function with exceptional spatial and temporal precision [5].

Signal Acquisition Technologies

Non-Invasive Electroencephalography (EEG)

EEG employs electrodes placed on the scalp according to standardized systems (10-20, 10-10, or 10-5 layouts) to record electrical potentials arising from cortical activity [15]. Modern EEG systems typically utilize 16 to 256 electrodes, with higher densities providing improved spatial sampling but requiring more complex setup and processing [11].

The acquisition hardware includes:

- Electrodes: Silver/silver-chloride (Ag/AgCl) discs with conductive electrolyte gels

- Amplifiers: Differential amplifiers with high common-mode rejection ratios (CMRR >100 dB)

- Filters: Hardware-based bandpass filtering (typically 0.1-100 Hz)

- Analog-to-digital converters: 16-24 bit resolution at sampling rates of 250-2000 Hz [15]

Despite advantages in cost, portability, and safety, EEG signals suffer from inherent limitations including low spatial resolution (approximately 3-10 cm² of cortical surface per electrode), vulnerability to various artifacts (ocular, muscular, cardiac, and environmental), and attenuation of high-frequency neural activity [12].

Invasive Electrocorticography (ECoG)

ECoG involves surgical implantation of electrode grids or strips directly on the cortical surface, typically during monitoring for epilepsy surgery [5]. Standard configurations include:

- Grid electrodes: 8×8 platinum-iridium electrodes with 4mm diameter (2.3mm exposed surface) embedded in silicon with 1cm inter-electrode distance

- Strip electrodes: Linear arrays of 4-6 electrodes

- High-density grids: Smaller electrodes with reduced spacing (3-5mm) for improved spatial resolution [5]

EcoG provides exceptional signal quality with:

- Higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) than EEG

- Broader frequency response (0-200+ Hz)

- Superior spatial resolution (approximately 0.5-1 cm)

- Reduced vulnerability to non-neural artifacts [12] [5]

The primary disadvantages include the requirement for craniotomy, limited recording duration (typically 5-12 days), infection risks, and restricted coverage to clinically indicated regions [10] [5].

Quantitative Signal Comparisons

Table 2: EEG vs. ECoG Signal Characteristics Comparison

| Parameter | Scalp EEG | ECoG |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Amplitude | 10-100 µV | 50-500 µV |

| Spatial Resolution | 3-10 cm² | 0.5-1 cm² |

| Temporal Resolution | ~10 ms | <1 ms |

| Frequency Range | 0.1-80 Hz | 0-200+ Hz |

| Artifact Susceptibility | High | Moderate |

| Primary Artifacts | Ocular, muscular, environmental | Blinks, saccades, line noise |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Low | High |

| High-Gamma Sensitivity | Limited | Excellent |

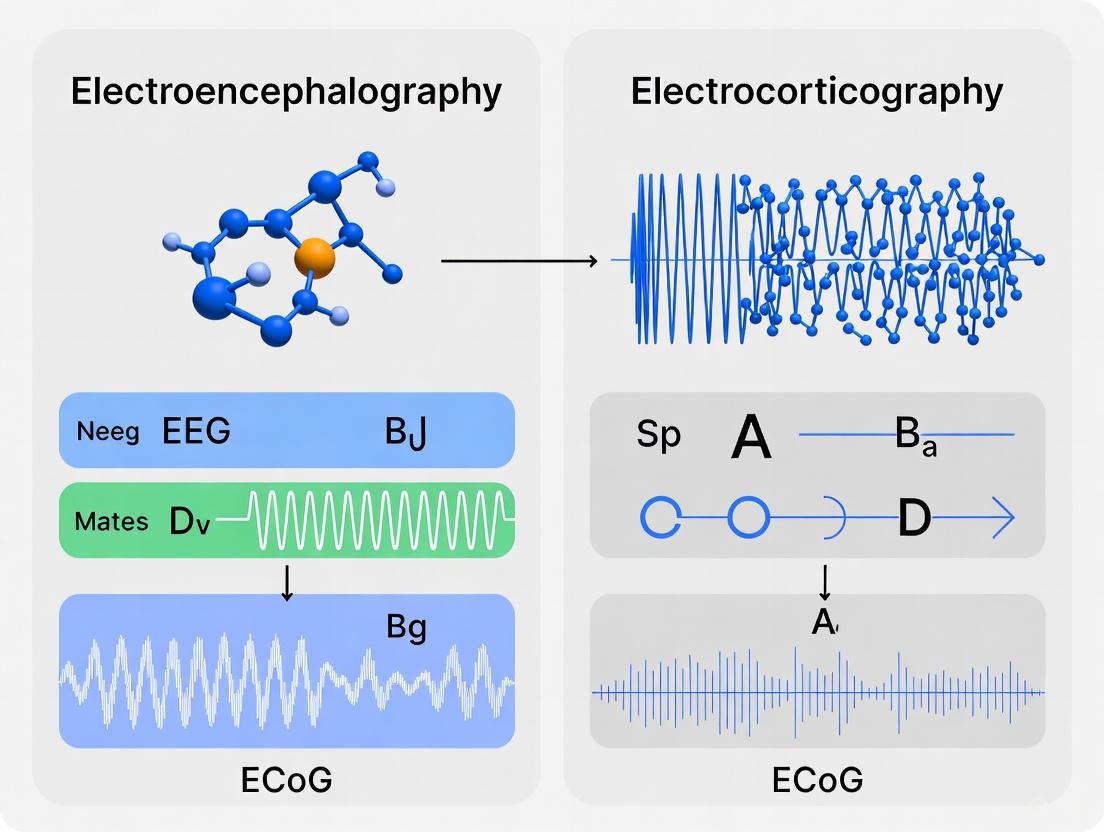

Figure 1: Signal Pathways from Neural Origins to Acquisition

Experimental Protocols for Signal Quality Assessment

Simultaneous EEG-ECoG Recording Methodology

Rigorous comparison of EEG and ECoG signal quality requires simultaneous recording during identical task conditions. The protocol established by [12] demonstrates this approach:

Patient Selection and Electrode Placement:

- Participants: Patients undergoing invasive monitoring for epilepsy surgery (typically n=4-8)

- ECoG electrodes: Subdural grid and strip electrodes placed based on clinical requirements

- EEG electrodes: Standard scalp electrodes following 10-20 system placement

- Ground/reference selection: Distant from epileptic foci and cortical areas of interest [5]

Experimental Paradigm:

- Blink and Saccade Tasks: Patients perform timed eye blinks (5-10/second) and horizontal/vertical saccades

- Motor Tasks: Simple motor execution or imagery (hand clenching, finger tapping)

- Sensory Tasks: Auditory tones or visual stimuli at controlled intervals

- Cognitive Tasks: Working memory or attention tasks with precise timing [12]

Data Acquisition Parameters:

- Sampling rate: ≥1200 Hz to capture high-frequency components

- Filter settings: 0.1-500 Hz bandpass with notch filter at line frequency

- Synchronization: Common trigger signals mark task events across both systems

- Video monitoring: Concurrent recording at 25 Hz to identify artifacts [12] [5]

Signal Quality Metrics and Analysis

Quantitative assessment employs multiple complementary metrics:

Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) Calculation:

- Task-related potentials: Compare peak amplitude during events to baseline periods

- Frequency-domain analysis: Compute power ratios in relevant bands (e.g., high-gamma)

- Trial-to-trial consistency: Measure cross-trial correlation coefficients [12]

Artifact Contamination Assessment:

- Ocular artifacts: Quantified using signal-to-interference ratio (SIR)

- Muscle artifacts: EMG power estimation in high-frequency ranges (>80 Hz)

- Line noise: Power measurement at 50/60 Hz and harmonics [12]

Spatial Specificity Evaluation:

- Topographic mapping: Compare spatial extent of task-activated regions

- Volume conduction effects: Measure signal fall-off with distance from source

- Functional localization: Contrast with electrical cortical stimulation results [5]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for EEG/ECoG Research

| Item | Function/Purpose | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| g.USBamp Amplifiers | Research-grade signal acquisition for ECoG | 16-channel units, FDA-approved for invasive recordings, 1200 Hz sampling rate, low noise-floor in high-frequency range [5] |

| Emotiv EPOC+ | Portable EEG acquisition | 14 channels, saline-based electrodes, research SDK available [15] |

| Platinum-Iridium Electrodes | ECoG grid and strip electrodes | 4mm diameter with 2.3mm exposed surface, 1cm inter-electrode distance, embedded in silicon [5] |

| Electrode Gel/Paste | Scalp interface for EEG | High-chloride electrolyte gels, abrasive pastes for skin preparation [15] |

| BCI2000 Software Platform | General-purpose BCI research platform | Modular architecture for data acquisition, stimulus presentation, and real-time analysis [5] |

| CURRY Software Package | Electrode localization and 3D brain modeling | Co-registration of pre-operative MRI with post-implantation CT [5] |

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) | Artifact removal from EEG | Separate neural signals from ocular, cardiac, and muscle artifacts [14] |

| Wavelet Transform Toolboxes | Time-frequency analysis | MATLAB toolboxes for decomposing non-stationary neural signals [14] |

| EEGNet | Deep learning classification | Convolutional neural network optimized for EEG-based BCIs [9] |

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Signal Quality Assessment

Implications for BCI Applications and Future Directions

The choice between EEG and ECoG signal acquisition involves fundamental trade-offs that must be aligned with application requirements. Non-invasive EEG remains the preferred modality for applications where safety, cost, and accessibility are prioritized over signal fidelity, such as neurofeedback, basic communication systems, and preliminary brain function assessment [11] [14].

ECoG provides a superior signal platform for advanced BCI applications requiring precise control, such as individual finger manipulation of robotic hands [9] and sophisticated communication systems. Recent demonstrations of real-time robotic hand control at individual finger level using ECoG-derived signals highlight the potential of invasive approaches for restoring complex motor functions [9].

Future developments focus on bridging this fidelity-accessibility gap through:

- High-density EEG systems: Increasing electrode density (256+) with advanced source localization algorithms

- Minimally invasive technologies: Endovascular stents containing electrode arrays, reducing surgical risk

- Hardware advancements: Miniaturized, wireless amplifiers with improved noise characteristics

- Algorithmic innovations: Deep learning approaches that extract more information from noisier signals [13] [9]

The physiological origins of brain signals fundamentally constrain what can be recorded at scalp versus cortical surfaces. While ECoG provides direct access to neural electrical activity with minimal degradation, EEG must contend with the signal-attenuating effects of intervening tissues. This neuroanatomical reality creates an inescapable trade-off between signal quality and practical accessibility that continues to shape BCI research and development. Understanding these fundamental relationships enables researchers to select appropriate acquisition methods and develop increasingly sophisticated approaches to overcome these biological constraints.

The pursuit of optimal brain-computer interface (BCI) systems necessitates a deep understanding of the fundamental properties of the neural signals that drive them. Electroencephalography (EEG) and Electrocorticography (ECoG) represent two primary approaches for measuring brain electrophysiological activity, each with a distinct profile of advantages and limitations. Their comparative signal properties—specifically spatial resolution, temporal resolution, and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR)—are critical determinants for their application in both basic neuroscience research and clinical BCI development. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of these core properties, framing them within the context of BCI signal quality research. We summarize quantitative data, detail experimental methodologies for their characterization, and visualize the underlying signaling pathways and workflows to equip researchers and drug development professionals with a clear framework for technology selection.

Core Signal Properties: A Quantitative Comparison

The choice between EEG and ECoG involves a fundamental trade-off between invasiveness and signal fidelity. The table below provides a consolidated quantitative comparison of their core signal properties.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of EEG and ECoG Signal Properties

| Property | EEG (Non-Invasive) | ECoG (Invasive) | Technical Implications for BCI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | ~1-2 cm (Low) [16] [17] | 1 mm - 1 cm (High) [5] [16] | ECoG enables localization of neural activity to specific gyri and functional areas, while EEG measures blurred activity from larger cortical regions. |

| Temporal Resolution | ~1-5 ms (High) [18] | <1-5 ms (Very High) [16] | Both modalities capture rapid neural dynamics. ECoG's higher SNR allows for more reliable tracking of high-frequency oscillations. |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Low [12] [17] | High [5] [12] | ECoG's proximity to the source and lack of skull attenuation yield stronger signals with less contamination from non-neural artifacts. |

| Frequency Range | Effectively up to ~40-80 Hz [18] [17] | Up to 200-500 Hz (High Gamma) [5] [17] | ECoG provides access to the high-gamma band (70-110 Hz), a robust indicator of local cortical function and task-related activity. |

| Primary Signal Source | Synchronized postsynaptic potentials from large neuronal populations, filtered and attenuated by skull, CSF, and other tissues. [16] [17] | Synchronized postsynaptic potentials (local field potentials) recorded directly from the cortical surface. [16] [17] | ECoG signals are a more direct measure of cortical activity, while EEG signals are a heavily spatially filtered and attenuated derivative. |

Experimental Protocols for Signal Property Characterization

Rigorous experimental protocols are essential for empirically validating the theoretical signal properties of EEG and ECoG. The following methodologies are commonly employed in the field.

Protocol for Assessing SNR and Artifact Susceptibility

Objective: To quantitatively compare the susceptibility of simultaneously recorded EEG and ECoG signals to artifacts from eye blinks and saccades [12].

Methodology:

- Participant & Setup: Data are acquired from patients undergoing pre-surgical monitoring for epilepsy with subdural ECoG electrode grids. Scalp EEG electrodes are simultaneously placed over approximately homologous regions, particularly the prefrontal cortex [12].

- Task & Recording: Participants are instructed to perform spontaneous eye blinks and saccades (e.g., following a visual cue). A high-speed digital video camera (e.g., 25 Hz) is synchronized with the neural data acquisition to mark the exact onset of ocular events [12].

- Data Analysis:

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio Calculation: The SNR for blink-related potentials is quantified. The signal power (S) is defined as the mean amplitude in a post-blink time window (e.g., 200-400 ms). The noise power (N) is defined as the standard deviation of the amplitude in a pre-blink baseline period (e.g., -200 to 0 ms). SNR is calculated as S/N [12].

- Topographic Mapping: The spatial distribution of blink-related potential changes is analyzed across both ECoG and EEG electrode arrays.

Expected Outcome: This protocol typically reveals that while ECoG exhibits a much higher SNR overall, electrodes at the anterior edge of the ECoG grid (closest to the eyes) can still record blink-related artifacts. However, the artifact contamination in ECoG is far more localized and of smaller magnitude relative to the neural signal compared to the widespread and dominant artifacts in EEG [12].

Protocol for Evaluating Spatial Resolution via Multivariate Pattern Analysis

Objective: To compare the sensitivity of EEG and ECoG to fine-grained, population-level neural codes representing different visual object categories [18].

Methodology:

- Stimuli: Participants view images from different object categories (e.g., animals, chairs, faces) under varying viewing conditions (size, orientation) [18].

- Data Acquisition: EEG and ECoG data are recorded from different cohorts (healthy participants and epilepsy patients, respectively) using the same stimulus set. ECoG is typically recorded from the temporal and occipital cortex [18].

- Multivariate Analysis: A multivariate pattern analysis (MVPA) or decoding algorithm (e.g., a support vector machine) is trained to distinguish between neural activity patterns associated with different object categories.

- Features: For ECoG, features can include spectral power in various frequency bands, phase, or temporal correlations between electrodes [19].

- Classification: The classifier is trained and tested using cross-validation to estimate decoding accuracy. The time course of decoding accuracy is analyzed using a sliding time window approach [18] [19].

Expected Outcome: This protocol demonstrates that ECoG provides superior spatial information. Decoding of object categories from ECoG signals achieves higher accuracy and can begin to rise earlier after stimulus onset compared to EEG. Furthermore, analyses using temporal correlations between ECoG electrodes have been shown to carry additional category information beyond spectral power alone, highlighting the advantage of ECoG's dense spatial sampling [19].

Visualization of Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Neural signal pathways for ECoG and EEG.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for signal comparison.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and software solutions used in comparative EEG/ECoG research, as cited in the literature.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Experimental Materials

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subdural Grid/Strip Electrodes [5] [16] | Hardware | To record electrical potentials directly from the cortical surface. Typically made of platinum-iridium, with 4-256 contacts and 1 cm spacing. | Placed subdurally during epilepsy monitoring to localize epileptic foci and, concurrently, for ECoG research data collection. [5] |

| g.USBamp Amplifier [5] | Hardware | A safety-rated, FDA-approved biosignal amplifier for high-quality data acquisition. Chosen for its low noise-floor in high-frequency ranges critical for ECoG. | Used in research settings to capture ECoG signals at a high sampling rate (e.g., 1200 Hz) to accurately resolve high-gamma activity. [5] |

| BCI2000 Software Platform [5] [20] | Software | A general-purpose, open-source software system for real-time biosignal data acquisition, stimulus presentation, and brain-state translation. | Serves as the core software for running BCI paradigms, providing real-time feedback, and implementing functional mapping techniques like SIGFRIED. [5] |

| SIGFRIED (SIGnal Modeling For Realtime Identification and Event Detection) [5] | Software / Method | A real-time functional mapping method that detects significant task-related ECoG activity (e.g., in high-gamma band) without electrical stimulation. | Used for passive functional mapping of eloquent cortex (e.g., motor, language areas) as a preliminary to or replacement for cortical stimulation. [5] |

| CURRY Software Package [5] | Software | A neuroimaging software used for co-registration of pre-operative MRI with post-implantation CT scans. | Creates 3D cortical models with precise electrode localization, which is essential for correlating neural signals with anatomical structures. [5] |

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) [18] [14] | Algorithm | A blind source separation method used to decompose multichannel EEG/ECoG data into independent components, often for artifact removal. | Applied during preprocessing to identify and remove components corresponding to eye blinks, muscle activity, or line noise from the data. [18] |

The comparative analysis of EEG and ECoG reveals a clear trade-off. ECoG provides superior signal quality characterized by high spatial resolution, a broad frequency range inclusive of functionally critical high-gamma activity, and a high SNR. These properties make it an exceptional tool for researching fine-grained neural population codes and developing high-performance BCIs. However, its requirement for invasive surgery limits its use to specific clinical populations. In contrast, EEG is non-invasive, safe, and highly accessible, but its utility is constrained by lower spatial resolution and SNR. The future of BCI research lies not only in the independent refinement of each technology but also in the development of hybrid systems that leverage their complementary strengths and in the advancement of signal processing techniques that can extract maximal information from these critical windows into brain function.

Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technology establishes a direct communication pathway between the brain and external devices, offering transformative potential for diagnosing and treating neurological disorders [10]. The efficacy of any BCI system is fundamentally constrained by a critical engineering trade-off: the balance between the quality of acquired neural signals and the medical risks associated with the interface's invasiveness [10] [13]. On one end of the spectrum, non-invasive techniques like electroencephalography (EEG) offer minimal risk but provide signals with limited spatial resolution and fidelity. On the other, invasive methods like electrocorticography (ECoG) capture high-fidelity neural activity but require surgical implantation, introducing risks such as infection and tissue response [14]. This whitepaper provides a technical analysis of this trade-off, framed within the context of EEG versus ECoG for BCI signal quality research. We synthesize current data, detail experimental methodologies, and outline the material toolkit essential for advancing research in this field, aiming to guide researchers and drug development professionals in making informed decisions for clinical translation and innovation.

Neural Signal Acquisition: A Dimensional Framework

At its core, BCI technology involves measuring brain activity and converting it into functionally useful outputs in real time [21]. The initial stage of this pipeline—signal acquisition—is paramount, as the quality of the raw data dictates the performance ceiling of the entire system [13]. BCI signal acquisition technologies can be categorized along a primary axis of invasiveness, which is directly correlated with both signal fidelity and surgical risk.

Table 1: Classification of Primary BCI Signal Acquisition Modalities

| Modality | Invasiveness | Signal Fidelity & Spatial Resolution | Key Advantages | Primary Clinical Risks & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scalp EEG | Non-invasive | Low spatial resolution, susceptible to noise [22] [10]. | Cost-effective, portable, high temporal resolution, minimal risk [10] [14]. | Low signal-to-noise ratio for deep sources, limited to cortical activity [10]. |

| fNIRS | Non-invasive | Indirect measure of neural activity, limited penetration depth [10]. | Less affected by electrical artifacts than EEG [10]. | Low temporal resolution, primarily measures cortical hemodynamics [10]. |

| MEG | Non-invasive | High spatiotemporal resolution [10]. | Excellent for imaging cortical activity [10]. | Very expensive, requires specialized shielding, ineffective for deep brain signals [10]. |

| ECoG | Semi-invasive (subdural) | Higher spatial resolution and signal clarity than EEG [10] [14]. | Superior signal quality without penetrating brain tissue [10]. | Requires craniotomy, risk of infection, signal stability can be affected by scarring over time [14]. |

| Intracortical Microelectrodes | Invasive | Very high spatial resolution for single-neuron or local field potential recording [21]. | Ultimate signal fidelity and bandwidth for motor control and complex tasks [21]. | Highest risk profile (surgical injury, infection, glial scarring), potential for performance deterioration [21] [14]. |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental trade-off relationship between signal fidelity and invasiveness that underpins BCI design choices.

Quantitative Comparison: EEG vs. ECoG Signal Parameters

The choice between EEG and ECoG is a central decision point in BCI research, balancing acceptable risk against required data quality. The following table summarizes key quantitative and qualitative differences between these two primary modalities.

Table 2: Quantitative and Qualitative Comparison of EEG and ECoG for BCI

| Parameter | Scalp EEG | ECoG / sEEG |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Low (cm-range) [10] | High (mm-range) [10] |

| Temporal Resolution | High (millisecond-level) [14] | High (millisecond-level) [10] |

| Signal Amplitude | Microvolt range (µV) | Millivolt range (mV), significantly larger [10] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Low; susceptible to EMG, EOG, and environmental noise [14] | High; minimal attenuation from skull and scalp [10] |

| Spectral Bandwidth | Effectively up to ~80 Hz (Gamma) | Broadband, including high-frequency activity (HFA) up to 200+ Hz [10] |

| Primary Clinical Risks | Minimal (skin irritation) [14] | Surgical risks (hemorrhage, infection), long-term biocompatibility (scarring) [10] [14] |

| Typical Use Case | Brain state monitoring, neurofeedback, basic communication [22] [14] | Presurgical epilepsy mapping, high-performance communication, complex motor prosthesis control [23] [10] |

| Biocompatibility Challenge | Non-biofouling electrode gels/materials | Chronic tissue response: gliosis, encapsulation, signal degradation [14] |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating the Trade-off

Rigorous experimental protocols are required to quantitatively assess the performance and limitations of EEG and ECoG systems. The following section details methodologies cited in recent literature.

Protocol for Assessing Non-Invasive EEG Decoding Performance

This protocol, based on studies decoding visual features from scalp EEG, evaluates the upper limits of information that can be extracted from non-invasive signals [24].

- Objective: To determine the feasibility of decoding parametric visual features (e.g., color, orientation) from multi-item displays using scalp EEG.

- Participant Preparation: Recruit healthy adults with normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Apply a high-density EEG cap (e.g., 64+ channels). Impedance at each electrode should be maintained below 10 kΩ. Use a chin rest to stabilize head position and minimize movement artifacts.

- Stimuli and Task: Present participants with bilateral visual stimuli (e.g., Gabor gratings) for a short duration (e.g., 300 ms). Each stimulus should possess a unique, parametrically varied feature (e.g., 48 possible colors/orientations). The task should require attentive viewing, such as a subsequent memory test, to ensure controlled cognitive engagement.

- Data Acquisition: Record continuous EEG data with a sampling rate ≥ 500 Hz. Trigger codes should mark stimulus onset with high temporal precision, correcting for any known display lag.

- Preprocessing:

- Downsampling: Reduce sampling rate to decrease computational load.

- Filtering: Apply band-pass (e.g., 0.1-100 Hz) and notch (50/60 Hz) filters.

- Artifact Removal: Employ advanced algorithms like Independent Component Analysis (ICA) or Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) to remove ocular and muscular artifacts [14].

- Epoching: Segment data into epochs time-locked to stimulus onset.

- Feature Extraction & Classification: Use multivariate pattern analysis (MVPA). For each time point, train a Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) classifier on the spatial pattern of EEG activity across all electrodes to discriminate between feature values (e.g., different colors) [24]. Assess decoding accuracy and its time course relative to stimulus onset.

- Key Outcome Measures: Peak decoding accuracy, time to peak decoding, and the topographic distribution of informative electrodes (e.g., contralateral to the stimulus).

Protocol for Validating ECoG as a Predictor for Implantable BCI Performance

This protocol uses scalp EEG to predict whether a patient is a suitable candidate for an invasive ECoG-based BCI, minimizing unnecessary surgery [23].

- Objective: To assess if non-invasive scalp EEG can detect sensorimotor rhythm modulations that predict successful control of an implanted ECoG-BCI.

- Participant Cohorts: Include both healthy control participants and target patient populations (e.g., individuals with Locked-In Syndrome (LIS) due to ALS) [23].

- Experimental Paradigm: Participants perform a movement task involving actual (healthy controls) or attempted (LIS patients) hand movements, alternating with a rest task. Sufficient trials must be collected to ensure statistical power.

- Data Acquisition: Record high-density scalp EEG during task performance. For patient cohorts, ensure the experimental setup is adaptable to their physical limitations.

- Signal Processing and Analysis:

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) Calculation: Calculate the SNR of the resting-state EEG to ensure signal quality is sufficient for analysis [23].

- Spectral Analysis: For the movement task, compute the event-related synchronization/desynchronization (ERS/ERD) in key frequency bands. Focus on the beta band (13-30 Hz) over sensorimotor electrodes.

- Performance Prediction Metric: The key predictive metric is the presence and magnitude of movement-related beta band suppression. A strong and consistent suppression is indicative of a viable candidate for an ECoG-BCI that relies on motor imagery [23].

- Key Outcome Measures: Resting-state SNR, magnitude and consistency of movement-related beta power suppression in sensorimotor areas.

The workflow for this predictive validation protocol is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Advancing research on the invasiveness trade-off requires a suite of specialized materials and technologies. The following table details key components of the research toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Technologies for BCI Development

| Item | Function & Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density EEG Systems | Acquire non-invasive neural data with improved spatial sampling for basic research and pre-surgical screening [23]. | 64-channel to 256-channel systems; often integrated with active electrodes for noise reduction. |

| ECoG Grid/Strip Electrodes | Record cortical surface signals with high fidelity in intraoperative or mid-term implantable settings [10]. | Flexible grids with high-density electrode arrays (e.g., 256 contacts); often used in epilepsy monitoring. |

| Intracortical Microelectrode Arrays | Investigate the ultimate limits of signal fidelity by recording single-neuron or local field potential activity [21]. | Utah Array (Blackrock Neurotech), Neuralace (Blackrock's new flexible lattice), Neuralink's N1 implant. |

| Flexible & Biocompatible Polymers | Serve as substrates for next-generation electrodes to mitigate the foreign body response and improve chronic signal stability [22] [13]. | Materials like polyimide, parylene-C, and hydrogels. "Brain film" from Precision Neuroscience [21]. |

| 3D Printing / Additive Manufacturing | Enable personalization of device form factor, particularly for hearables and custom-fit electrode mounts, enhancing comfort and signal quality [22]. | Used to create patient-specific earpieces for "hearable" BCIs that conform to the unique anatomy of the ear canal [22]. |

| Advanced Artifact Removal Algorithms | Critical software tools for improving the effective SNR of non-invasive EEG by isolating and removing biological and environmental noise [14]. | Independent Component Analysis (ICA), Wavelet Transform (WT), Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) [14]. |

| Machine Learning/Deep Learning Platforms | Decode complex neural patterns in real-time for high-performance BCI control and signal classification [10] [14]. | Used for tasks like speech decoding from ECoG and movement intention detection from EEG. |

The trade-off between signal fidelity and invasiveness remains a foundational challenge in BCI research. Non-invasive EEG offers safety and practicality, making it suitable for widespread monitoring and basic intervention, while invasive and semi-invasive methods like ECoG provide the signal quality necessary for high-stakes communication and control. The future of the field lies in developing technologies that flatten this trade-off curve. This will be achieved through innovations in flexible and biocompatible materials that reduce the foreign body response [22] [21], personalized manufacturing for optimal fit and signal acquisition [22], sophisticated signal processing powered by artificial intelligence that extracts more information from noisier signals [10] [14], and the emergence of minimally invasive endovascular approaches [21]. For researchers and clinicians, the decision matrix must carefully weigh the required performance against patient risk, a calculation that will continue to evolve as these technological frontiers advance.

Electroencephalography (EEG) and electrocorticography (ECoG) are prominent neuroimaging techniques pivotal to brain-computer interface (BCI) research and development. The quest for superior signal quality drives the comparison between these modalities. EEG, as a non-invasive method, measures electrical activity from the scalp, but its signals are fundamentally altered by volume conduction, where currents diffuse through the cerebrospinal fluid, skull, and scalp [25] [26]. In contrast, ECoG involves the invasive placement of electrodes directly on the cortical surface, bypassing the skull but inciting a biological tissue response that can chronically degrade signal fidelity [27] [28]. This technical guide delineates these core inherent limitations—volume conduction in EEG and the foreign body response in ECoG—situating them within a broader thesis on BCI signal quality. We synthesize current empirical data, detail experimental methodologies for their quantification, and provide visual frameworks to aid researchers in navigating these challenges.

Volume Conduction in EEG: Signal Blurring and Its Consequences

Volume conduction refers to the propagation of electrical currents from neural sources through the various resistive tissues of the head before being recorded at the scalp surface by EEG electrodes. This process significantly compromises the spatial resolution of EEG signals.

The Biophysical Basis of Volume Conduction

The head is a complex, multi-layered volume conductor comprising brain tissue, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), skull, and scalp, each with distinct electrical conductivity properties. Currents originating from postsynaptic potentials in cortical pyramidal cells must traverse these layers. The skull, in particular, acts as a significant low-pass filter, severely attenuating high-frequency components and spatially smearing the electrical field [26]. Empirical validation studies using stereotactic EEG (sEEG) during electrical stimulation mapping have demonstrated a persistent mismatch between measured potentials and those simulated with even the most sophisticated finite element method (FEM) head models. This mismatch, which can be up to 40 µV (a 10% relative error) in 80% of stimulation-recording pairs, is modulated by the distance between the stimulating and recording electrodes [26].

Functional Impact on BCI Applications and Neural Interpretation

The blurring effect of volume conduction presents a fundamental constraint on the information density of non-invasive BCIs. A recent breakthrough study demonstrated real-time, non-invasive robotic hand control at the individual finger level using EEG [9]. This achievement was possible despite the "substantial overlap in neural responses associated with individual fingers" [9] and the significant attenuation of spatial resolution due to volume conduction. The system leveraged a deep neural network (EEGNet) to decode intentions from highly overlapping signals, achieving accuracies of 80.56% for two-finger and 60.61% for three-finger motor imagery tasks [9]. This success underscores that while volume conduction blurs cortical representations, advanced computational methods can partially overcome this limitation for specific BCI tasks.

Furthermore, volume conduction is not merely a technical nuisance; it may also have a functional role in neural communication. A recent discovery identified "volume current coupling" (VcC), a direct electrical coupling between distant neural populations mediated by these leakage currents [25]. This mechanism is distinct from synaptic communication and is proposed to generate cognitive and behavioral biases, suggesting that the brain's inherent electrical crosstalk, evident in EEG, may be a feature of its computational architecture [25].

Quantitative Signal Attenuation Across Tissue Layers

The following table summarizes empirical data on how different tissue layers impact key signal quality metrics, derived from a sheep model study comparing sub-scalp EEG configurations [28].

Table 1: Signal Quality Metrics Across Different Electrode Depths

| Electrode Location | Relative VEP SNR (vs. ECoG) | Maximum Bandwidth (High Gamma, Hz) | Invasiveness & Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECoG (Subdural) | 1.0 (Reference) | 180 | Highly invasive; requires craniotomy, risk of tissue response & scarring [28]. |

| Peg (Skull-Embedded) | Approaches ECoG | 120-180 | Minimally invasive; requires burr hole, high signal quality [28]. |

| Skull Surface | Lower than Peg | <120 | Minimally invasive; signal attenuated by skull & periosteum [28]. |

| Periosteum | Lower than Skull Surface | <120 | Minimally invasive; significant signal attenuation from multiple layers [28]. |

| Endovascular | Comparable to Periosteum | ~120 | Minimally invasive; limited spatial coverage, cannot be removed [28]. |

| Scalp EEG | Lowest | ~80 (Severely attenuated) | Non-invasive; severe attenuation & blurring from all tissue layers [28] [26]. |

Tissue Response in ECoG: The Foreign Body Reaction

While ECoG bypasses the skull to provide signals with higher spatial resolution and bandwidth than EEG, its invasive nature triggers a cascade of biological events known as the foreign body response, which chronically compromises signal quality.

Biological Mechanisms and Chronology

The implantation of an ECoG array immediately causes local tissue disruption, bleeding, and an acute inflammatory response. This is followed by a chronic phase where the immune system attempts to isolate the foreign object. Key processes include:

- Microglial Activation and Astrocytic Scarring: Immune cells in the brain (microglia) activate and recruit astrocytes to the implant site. These cells proliferate and form a dense, glial scar around the electrodes [27] [28].

- Neuroinflammation: Persistent inflammation in the local tissue environment can lead to neuronal dysfunction and death in the vicinity of the electrodes [28].

- Neuronal Loss and Axonal Degradation: The encapsulation of electrodes by the glial scar physically and chemically separates them from the target neurons, increasing the distance between neural sources and the recording contacts and leading to signal attenuation over time [28].

Impact on ECoG Signal Fidelity and Biomarker Utility

The tissue response directly degrades the electrophysiological signals that ECoG aims to capture.

- Signal Attenuation: The glial scar acts as an insulating layer, attenuating the amplitude of recorded neural signals [28].

- Reduced High-Frequency Activity (HFA): HFA, including high-gamma oscillations (>80 Hz) and high-frequency oscillations (HFOs), are crucial biomarkers for epileptogenic zone localization and BCI control. These high-frequency components are particularly susceptible to degradation by the increasing distance and impedance caused by the scar tissue [27].

- Biomarker Instability: The dynamic nature of the tissue response means that the amplitude and spectral properties of recorded signals are not stable over long periods, complicating the use of chronic BCIs and requiring repeated calibration [28].

Quantitative analysis of ECoG biomarkers must account for this inherent variability. For instance, the statistical deviation of the modulation index (MI, a measure of phase-amplitude coupling) from a normative atlas—quantified as a z-score—has been shown to improve the sensitivity/specificity for classifying surgical outcomes in epilepsy from 0.86/0.48 to 0.86/0.76, indicating that controlling for anatomical and pathological variability enhances clinical utility [27].

Experimental Protocols for Quantification and Validation

To systematically study these limitations, standardized experimental protocols are essential.

Protocol for Validating Volume Conduction Models

This protocol, adapted from empirical validation studies, uses stereotactic EEG (sEEG) to ground-truth head models [26].

- Objective: To quantify the accuracy of FEM head models by comparing simulated electrical potentials to empirically measured ones.

- Subjects: Epilepsy patients undergoing pre-surgical evaluation with implanted sEEG electrodes.

- Stimulation & Recording: Apply biphasic electrical stimulation to a pair of adjacent sEEG contacts. Simultaneously record the resulting volume-conducted artifact potential across all other sEEG contacts.

- Imaging & Modeling: Acquire pre-implantation MRI and post-implantation CT scans. Construct multiple patient-specific FEM head models with increasing levels of detail (e.g., 4-shell vs. 6-shell conductivity profiles).

- Simulation & Comparison: For each model, simulate the potential distribution from the stimulation pair. Calculate the relative error between the simulated and measured potentials at all recording contacts. Analyze error as a function of distance from the stimulation source.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for validating volume conduction models using sEEG.

Protocol for Quantifying Chronic Tissue Response

This protocol assesses the foreign body reaction to implanted ECoG arrays and its impact on signal quality [27] [28].

- Objective: To histologically and electrophysiologically characterize the tissue response to chronic ECoG implants and correlate it with signal quality decay.

- Animal Model: Sheep or non-human primates implanted with ECoG arrays for a predefined period (e.g., 3-12 months).

- Chronic Electrophysiology: Periodically record resting-state ECoG and evoked potentials (e.g., VEPs). Quantify metrics like signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), power spectral density, and high-gamma power.

- Terminal Histology: Perfuse and extract the implanted cortex. Section the tissue and stain for markers of glial activation (e.g., GFAP for astrocytes, IBA1 for microglia) and neuronal nuclei (NeuN).

- Quantitative Analysis: Correlate the thickness of the glial scar and the density of neurons near the electrode interface with the degree of signal attenuation measured over time.

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for correlating chronic tissue response with ECoG signal decay.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Advancing research in this field requires a specific set of tools, from computational resources to biological assays.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Specification / Example |

|---|---|---|

| FEM Software (e.g., SimNIBS, ROAST) | To build realistic head models and simulate volume conduction of neural signals. | Supports multi-compartment head models with isotropic/anisotropic conductivity profiles [26]. |

| sEEG Electrodes & Stimulator | For empirical validation of volume conduction models via cortical stimulation mapping. | Provides ground-truth intracranial potential measurements [26]. |

| High-Density ECoG Arrays | For high-resolution cortical signal acquisition in both acute and chronic settings. | High channel count (e.g., 64-128 channels), flexible material (e.g., platinum-iridium) [27]. |

| Immunohistochemistry Antibodies | To visualize and quantify the tissue response to implanted electrodes. | Anti-GFAP (astrocytes), Anti-IBA1 (microglia), Anti-NeuN (neurons) [28]. |

| Deep Learning Decoders (e.g., EEGNet) | To decode neural intent from volume-conducted EEG signals. | Compact convolutional neural networks for EEG classification; enables fine-tuning for subject-specific adaptation [9]. |

| Signal Quality Metrics Toolbox | To quantitatively assess the impact of limitations on recorded signals. | Algorithms for calculating SNR, maximum bandwidth, and feature discriminativity [29]. |

The development of next-generation BCIs is intrinsically linked to a deeper understanding of their inherent technical constraints. For EEG, the primary challenge is the physical volume conduction of signals through the head, which blurs spatial information and complicates source localization. For ECoG, the principal limitation is the biological tissue response, which chronically degrades signal fidelity and threatens long-term stability. Navigating the trade-off between the non-invasiveness of EEG and the high signal quality of ECoG defines the current frontier of BCI research. Emerging minimally invasive technologies, such as sub-scalp EEG, offer a promising compromise [28]. Future progress hinges on the interdisciplinary integration of advanced biophysical modeling, novel electrode materials that mitigate the foreign body response, and robust machine learning algorithms capable of decoding intention from compromised signals. Acknowledging and systematically addressing these core limitations is essential for translating BCI technology from the laboratory to reliable clinical and consumer applications.

From Theory to Practice: BCI Applications and Signal Processing Methodologies

The evolution of Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technology has created new frontiers in neurotechnology, with electroencephalography (EEG) and electrocorticography (ECoG) emerging as prominent signal acquisition methods. Understanding the comparative advantages and limitations of these technologies is crucial for matching them to appropriate applications. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of EEG and ECoG performance across three dominant BCI application fields: rehabilitation, assistive communication, and neurosurgical mapping. Framed within a broader thesis on BCI signal quality research, this review synthesizes current technical specifications, experimental protocols, and performance benchmarks to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their technology selection process.

Technical Comparison of EEG and ECoG Modalities

Fundamental Signal Characteristics

EEG and ECoG represent distinct points on the neural signal acquisition spectrum, with fundamental differences in signal properties and implementation requirements.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of EEG and ECoG

| Parameter | EEG (Non-invasive) | ECoG (Semi-invasive) |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | 2-3 cm [3] | 1-4 mm [3] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Low (microvolt-level) [3] | High (5-10x EEG) [3] |

| Temporal Resolution | Millisecond range | Millisecond range |

| Invasiveness | Non-invasive | Surgical implantation required [30] |

| Temporal Stability | Variable between sessions [3] | Superior session-to-session [3] |

| Primary Signal Content | Summed postsynaptic potentials | Local field potentials [30] |

| Artifact Vulnerability | High (EMG, ocular, environmental) [3] | Low external artifacts, but susceptible to cardiac/respiratory interference [3] |

| Coverage Area | Whole scalp | Limited to implantation area [30] |

| Clinical Risk Profile | Minimal | Surgical risks (infection, tissue reaction) [3] |

Performance Benchmarks Across Applications

Direct performance comparisons between EEG and ECoG highlight critical trade-offs between invasiveness and capability across different application domains.

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Key BCI Applications

| Application Domain | EEG Performance Metrics | ECoG Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Speech Decoding | Limited vocabulary, multi-second delays [30] | 78 words/minute, 1,024-word vocabulary, 25% error rate, multi-second latency [30] |

| Motor Control | 80.56% accuracy (2-finger MI), 60.61% (3-finger) [9] | Hand gesture decoding: 69.7%-85.7% accuracy [30] |

| Surgical Mapping | Limited by spatial resolution | Clinical standard for functional mapping [30] |

| Visual Rehabilitation | Applied in non-invasive paradigms [31] | Used for mapping residual visual function [31] |

| Information Transfer Rate | Lower due to noise and limited bandwidth | Higher but constrained compared to intracortical methods [30] |

| Decoding Delay | Varies, can be significant in complex tasks | Multi-second delays common [30] |

| Long-term Stability | Requires recalibration; susceptible to environmental factors | Superior but faces tissue encapsulation challenges [3] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

EEG Protocol for Robotic Hand Control

Recent advances in EEG-based robotic control have demonstrated unprecedented individual finger-level control capabilities [9]. The following protocol details the methodology for achieving real-time robotic hand control:

Participant Preparation and Setup:

- Recruit experienced BCI users (able-bodied or motor-impaired populations)

- Apply high-density EEG cap (64+ channels) following standard 10-20 system

- Ensure electrode impedances are maintained below 5 kΩ

- Position robotic hand system within participant's field of view

- Calibration should establish baseline for 5-10 minutes with eyes open/closed

Task Paradigm Design:

- Implement both Movement Execution (ME) and Motor Imagery (MI) conditions

- Design binary (thumb-pinky) and ternary (thumb-index-pinky) classification tasks

- Structure trials with: (1) 2s rest period, (2) visual cue indicating target finger (1s), (3) movement execution/imagery period (4s), (4) feedback period (variable)

- Include 16 runs of each paradigm type per session with adequate rest periods

Signal Acquisition Parameters:

- Sampling rate: ≥256 Hz

- Bandpass filtering: 0.5-60 Hz

- Notch filter: 50/60 Hz line noise removal

- Record continuous EEG with event markers synchronized to task structure

Real-time Processing Pipeline:

- Preprocessing: Common average reference or Laplacian spatial filtering

- Feature extraction: Time-domain amplitude or deep learning embeddings

- Classification: Implement EEGNet architecture with fine-tuning mechanism

- Output: Continuous decoding results converted to robotic control commands

Validation Metrics:

- Calculate majority voting accuracy across trial segments

- Compute precision and recall for each finger class

- Perform repeated measures ANOVA to assess session-to-session improvement

- Document training time required to achieve proficiency

This protocol has demonstrated 80.56% accuracy for two-finger MI tasks and 60.61% for three-finger tasks in able-bodied participants [9].

ECoG Protocol for Speech Decoding

ECoG-based speech decoding requires specialized surgical placement and sophisticated analytical approaches. The following protocol outlines the methodology for optimal speech decoding:

Participant Selection and Surgical Planning:

- Identify candidates with clinical need for ECoG monitoring (e.g., epilepsy surgery evaluation)

- Plan electrode placement to cover key speech areas (inferior frontal, superior temporal, sensorimotor regions)

- Utilize high-density electrode grids (≥64 contacts) with 4-10 mm spacing

- Confirm coverage using neuronavigation with preoperative MRI

Data Acquisition Parameters:

- Sampling rate: 1000-2000 Hz to capture broad frequency spectrum

- Record referenced to common contact with minimal artifact

- Synchronize audio recording with neural data acquisition (<1ms precision)

- Monitor impedance throughout recording session

Speech Task Design:

- Include overt speech production of phonemes, words, and sentences

- Incorporate listening conditions to assess auditory processing

- Implement repetition tasks to control for acoustic variability

- Balance stimulus types across phonetic features and articulatory properties

Advanced Signal Processing:

- Apply common average reference or bipolar montage

- Extract frequency-specific power features (high-gamma, 70-150 Hz, most informative)

- Implement artifact rejection algorithms for movement, line noise, and amplifier saturations

- For continuous speech, apply masked mutual information analysis to improve temporal precision [32]

Decoding Model Implementation:

- Train subject-specific models using cross-validation approaches

- Utilize neural network architectures for sequence-to-sequence mapping

- Incorporate language models to constrain decoding output

- Validate performance on held-out data with appropriate metrics (word error rate, phoneme accuracy)

Spatiotemporal Mapping:

- Apply statistical mapping (cross-correlation, mutual information) between speech features and neural signals

- Generate activation maps for different articulatory features

- Account for multiple comparisons using cluster-based correction

This protocol has enabled speech decoding at approximately 78 words per minute with 1,024-word vocabulary using ECoG [30].

Signaling Pathways and System Workflows

EEG vs. ECoG Signal Acquisition Pathway

Diagram 1: Signal Acquisition Pathways

BCI Experimental Implementation Workflow

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Equipment

| Research Reagent/Equipment | Function/Purpose | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density EEG Systems | Non-invasive neural signal acquisition | 64-256 channels, impedance monitoring, dry/wet electrodes [9] |

| ECoG Grid Electrodes | Semi-invasive cortical surface recording | 32-128 contacts, 4-10 mm spacing, clinical grade [30] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | Neural decoding implementation | EEGNet architecture, fine-tuning capability [9] |

| Robotic Manipulators | Physical feedback and assistance | Multi-fingered robotic hands, exoskeletons [9] |

| Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation | Neuromodulation for signal enhancement | Figure-8 coils, neuronavigation integration [33] |

| Mutual Information Analysis Tools | Nonlinear signal analysis for ECoG | Masked analysis for silence removal [32] |

| Neuronavigation Systems | Precise spatial localization | MRI integration, real-time tracking [33] |

| Biocompatible Materials | Chronic implantation compatibility | Medical-grade silicone, platinum-iridium electrodes [3] |

| Signal Processing Toolboxes | Preprocessing and feature extraction | Custom MATLAB/Python implementations [32] [9] |

| Quantitative EEG Software | Clinical biomarker identification | Spectral power analysis, coherence metrics [34] |

Discussion and Future Directions

The comparative analysis of EEG and ECoG across rehabilitation, assistive communication, and neurosurgical mapping reveals a consistent trade-off between signal quality and invasiveness. EEG's non-invasive nature makes it suitable for widespread rehabilitation applications and iterative experimental paradigms, while ECoG's superior signal quality justifies its use in surgical mapping and high-performance communication applications where surgical intervention is already clinically indicated.

Future development trajectories will likely focus on hybrid approaches that combine multiple signal types, advanced signal processing algorithms to overcome inherent limitations of each modality, and novel electrode materials and designs that enhance long-term stability [3]. The emergence of deep learning applications in BCI has particularly boosted EEG decoding performance by automatically learning hierarchical and dynamic representations from raw signals, narrowing the performance gap with invasive methods [9].

For researchers and drug development professionals, selection between EEG and ECoG should be guided by application-specific requirements for spatial-temporal resolution, clinical risk tolerance, and practical implementation constraints. As both technologies continue to evolve, their complementary strengths will enable increasingly sophisticated BCI applications across the neurological sciences.

Electroencephalography (EEG) stands as a cornerstone non-invasive method for measuring neuronal activity in brain-computer interface (BCI) systems, offering exceptional temporal resolution and practical utility for real-time applications [35] [36]. While electrocorticography (ECoG) provides higher spatial resolution by recording signals directly from the cerebral cortex, it requires surgical implantation and presents greater risks [37] [38]. This technical guide examines two prominent EEG-based BCI paradigms—motor imagery (MI) for robotic control and P300 spellers for communication—focusing on their operational principles, performance metrics, and implementation methodologies within the broader context of BCI signal quality research.

The fundamental components of any BCI system include signal acquisition, signal processing (encompassing feature extraction, classification, and translation), and application interfaces [36]. EEG-based systems face inherent challenges due to the low signal-to-noise ratio and non-stationary nature of brain signals recorded through the skull and scalp [39] [40]. Despite these limitations, algorithmic advances and innovative paradigm designs have enabled increasingly robust applications, particularly in assistive technologies for individuals with severe neurological diseases or motor impairments [41] [42].

Motor Imagery for Robotic Control

Core Principles and Neural Mechanisms

Motor imagery (MI) involves the mental rehearsal of physical movements without actual motor execution. During MI tasks, event-related desynchronization (ERD) and event-related synchronization (ERS) occur in sensorimotor regions of the brain, providing detectable patterns in EEG signals [39]. These phenomena manifest as power decreases in mu (8-12 Hz) and beta (12-30 Hz) rhythms during movement planning and execution (ERD), followed by power increases above baseline during post-movement periods (ERS) [43].

The intuitive mapping between MI tasks and control commands makes this approach particularly suitable for robotic device control. Unlike evoked potential-based systems, MI-BCIs operate without requiring external stimulation, allowing users to generate control signals voluntarily through mental imagery alone [39]. This capability is especially valuable for individuals with severe motor disabilities, as it provides a non-muscular channel for environmental interaction and communication.

Signal Processing and Feature Extraction

Spatial filtering algorithms play a crucial role in MI-based BCI systems for feature extraction and dimensionality reduction. The Common Spatial Pattern (CSP) algorithm and its variants have demonstrated particular effectiveness by maximizing variance between different motor imagery classes [39]. Recent advances have focused on enhancing the robustness of temporal features through optimization techniques that minimize instability in the temporal domain.

Wei et al. (2025) proposed a Temporal Stability Learning Method (TSLM) that utilizes Jensen-Shannon divergence to quantify temporal instability and integrates decision variables to construct an objective function that minimizes this instability [39]. This approach enhances the stability of variance and mean values in extracted features, improving the identification of discriminative patterns while reducing the effects of signal non-stationarity.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of MI-BCI Classification Algorithms

| Method | Dataset | Accuracy (%) | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| TSLM [39] | BCI Competition III IVa | 92.43 | Temporal stability optimization |

| TSLM [39] | BCI Competition IV 2a | 84.45 | Temporal stability optimization |

| TSLM [39] | Self-collected dataset | 73.18 | Temporal stability optimization |

| SMI [43] | Three-class (14 subjects) | 68.88 | Somatosensory-motor integration |

| Conventional MI [43] | Three-class (14 subjects) | 62.29 | Standard motor imagery |

Enhancing Performance Through Hybrid Approaches

A significant challenge in MI-BCI systems is the phenomenon of "BCI inefficiency," where 15-30% of users cannot generate discriminative brain rhythms even after training [43]. To address this limitation, researchers have developed hybrid approaches that combine MI with complementary modalities.

Somatosensory-Motor Imagery (SMI) represents an innovative hybrid method that integrates motor execution and somatosensory sensation from tangible objects. In experiments controlling a remote robot at a three-way intersection, SMI achieved an average classification performance of 68.88% across all participants—6.59% higher than conventional MI approaches [43]. The improvement was particularly pronounced in poor performers, who showed a 10.73% performance increase with SMI compared to MI alone (62.18% vs. 51.45%).

Experimental Protocol: Somatosensory-Motor Imagery

Objective: To improve MI-BCI performance, particularly for poor performers, through hybrid somatosensory-motor imagery training [43].

Participants:

- 14 healthy, right-handed participants (7 female, mean age 27.21±3.88 years)

- All participants had prior MI experience