Deep Learning in EEG Analysis: A Comprehensive Review of Classification Methods and Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of deep learning methodologies for electroencephalography (EEG) signal classification, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Deep Learning in EEG Analysis: A Comprehensive Review of Classification Methods and Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of deep learning methodologies for electroencephalography (EEG) signal classification, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational concepts of EEG analysis, details key deep learning architectures like CNNs, RNNs, and Transformers, and examines their applications in seizure detection, mental task classification, and drug-effect prediction. The review also addresses critical challenges such as data scarcity and model interpretability, offers comparative performance analyses of different models, and discusses the future trajectory of deep learning for enhancing diagnostics and therapeutic development in clinical neuroscience.

Understanding EEG Signals and the Deep Learning Revolution in Neuroscience

Fundamental Principles of Electroencephalography (EEG)

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a non-invasive neurophysiological technique that records the brain's spontaneous electrical activity from the scalp [1]. These signals originate from the summed post-synaptic potentials of large, synchronously firing populations of cortical pyramidal neurons. When excitatory afferent fibers are stimulated, an influx of cations causes post-synaptic membrane depolarization, generating extracellular currents that are detected as voltage fluctuations by electrodes [2]. First recorded in humans by Hans Berger in 1924, EEG has evolved into an indispensable tool for investigating brain function, diagnosing neurological disorders, and advancing neurotechnology [1] [2].

The electrical signals measured by EEG are characterized by their oscillatory patterns, which are categorized into specific frequency bands, each associated with different brain states and functions [3]. The table below summarizes the standard EEG frequency bands and their clinical and functional correlates.

Table 1: Standard EEG Frequency Bands and Their Correlates

| Band | Frequency Range (Hz) | Primary Functional/Clinical Correlates |

|---|---|---|

| Delta (δ) | 0.5 - 4 | Deep sleep, infancy, organic brain disease [4] [3] |

| Theta (θ) | 4 - 8 | Drowsiness, childhood, emotional stress [4] [3] |

| Alpha (α) | 8 - 13 | Relaxed wakefulness, eyes closed, posterior dominant rhythm [1] [3] |

| Beta (β) | 13 - 30 | Active thinking, focus, alertness; can be increased by certain drugs [4] [3] |

| Gamma (γ) | 30 - 150 | High-level information processing, sensory binding [3] |

EEG Signal Acquisition and Preprocessing

The fidelity of an EEG recording is paramount for both clinical interpretation and advanced analytical models. The acquisition process involves several critical components and steps to ensure a high-quality, low-noise signal.

Acquisition Hardware and Electrodes

Modern EEG systems use multiple electrodes placed on the scalp according to standardized systems like the International 10-20 system, which specifies locations based on proportional distances between anatomical landmarks [2]. Electrodes can be invasive (surgically implanted) or, more commonly, non-invasive (placed on the scalp surface) [1].

Table 2: Key Materials and Equipment for EEG Acquisition

| Research Reagent / Equipment | Function and Specification |

|---|---|

| Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl) Cup Electrodes | High conductivity and low impedance; ideal for high-fidelity signal acquisition [5]. |

| Gold Cup Electrodes | Chemically inert, reducing skin reactions; suitable for long recordings [5]. |

| Conductive Electrolyte Gel/Paste | Establishes a stable, low-impedance electrical connection between the electrode and scalp [5]. |

| High-Impedance Amplifier | Critical for amplifying microvolt-level EEG signals (typically 2-100 µV) without distortion [6]. |

| Digitizer with Anti-aliasing Filter | Converts the analog signal to digital; a suitable filter band must be selected before digitization [5] [6]. |

A proper acquisition protocol requires careful skin preparation to achieve electrode-skin impedance values between 1 kΩ and 10 kΩ [5]. Patients must be instructed to remain still, as movements, blinking, and perspiration can introduce artifacts. Furthermore, the recording environment should be controlled to minimize electromagnetic interference (EMI) from sources like fluorescent lights and cell phones [5].

Preprocessing and Denoising Pipeline

Raw EEG signals are susceptible to various artifacts and noise, making preprocessing a crucial step before analysis or modeling. The primary goal is to isolate the neural signal of interest. The following workflow diagram outlines a standard EEG preprocessing pipeline.

Figure 1: Standard EEG signal preprocessing and denoising workflow.

From Features to Classification: Integration with Deep Learning

Moving from cleaned, preprocessed EEG data to a functional classification model involves feature extraction and the application of sophisticated learning algorithms. This process is central to modern EEG analysis, particularly for Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) and automated diagnosis.

Feature Extraction Methods

Feature extraction transforms the high-dimensional, raw EEG signal into a more manageable set of discriminative descriptors that are informative for the task at hand. The choice of feature is critical for model performance.

Table 3: Common Feature Extraction Methods for EEG Analysis

| Domain | Feature Extraction Method | Description | Suitability for Deep Learning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Power Spectral Density (PSD) | Distributes signal power over frequency, often computed via Welch's method [7] [3]. | Good input for fully connected networks. |

| Time-Frequency | Wavelet Transform | Resolves signal in both time and frequency, ideal for non-stationary signals [3]. | Excellent for 2D input to CNNs. |

| Spatial | Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) | Finds spatial filters that maximize variance for one class while minimizing for another [3]. | Preprocessing step for motor imagery tasks. |

| Nonlinear | Higher-Order Spectra, Entropy | Captures complex, dynamic interactions within the signal [1]. | Can be combined with other features. |

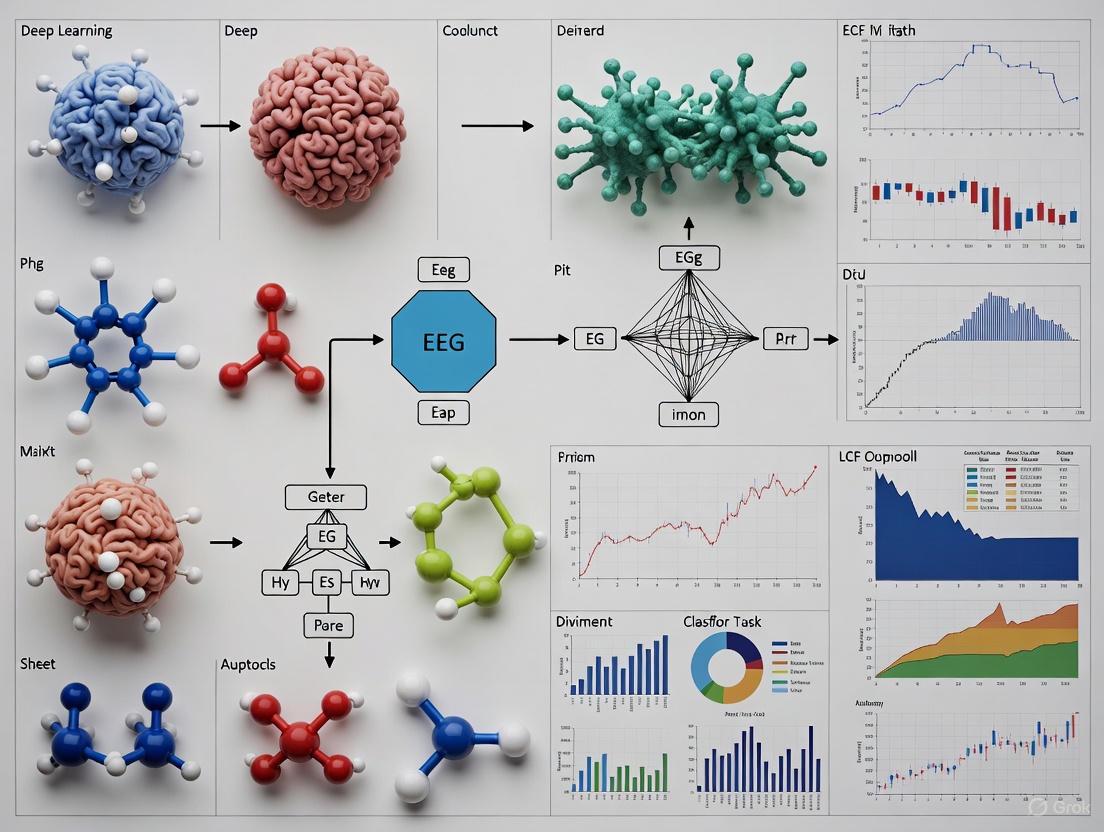

Deep Learning Architectures for EEG Classification

Deep learning models can automate feature extraction and classification, often learning complex patterns directly from raw or minimally processed data. The following diagram illustrates a typical deep learning pipeline for EEG classification, highlighting common architectural choices.

Figure 2: Deep learning pipeline for EEG classification tasks.

Different architectures excel in different contexts. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are highly effective at capturing spatial and temporal patterns [8] [9]. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, are well-suited for modeling long-range dependencies in time-series data [9]. More recently, Transformer models with customized, sparse attention mechanisms have been developed to process long EEG sequences efficiently while capturing complex temporal relationships [8].

For subject-independent tasks, which are crucial for real-world deployment, one proposed methodology involves using a Deep Neural Network (DNN) fed with precomputed features like Power Spectrum Density (PSD). Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is often applied first to reduce the dimensionality of the PSD features, and the model is trained on data from multiple subjects to learn generalizable patterns [7].

Clinical and Pharmaceutical Applications

EEG's high temporal resolution and non-invasive nature make it a powerful tool in clinical diagnostics and pharmaceutical development.

Disease Diagnosis and Monitoring

EEG is a cornerstone for diagnosing and monitoring a range of neurological and psychiatric conditions. Its applications include:

- Epilepsy: Identification of interictal epileptiform discharges and seizure classification are primary applications [1] [4].

- Sleep Disorders: Analysis of sleep stages and detection of disorders like sleep apnea [1] [8].

- Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Assisting in the diagnosis and study of conditions such as Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), schizophrenia, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [8]. Deep learning models have been developed to achieve high accuracy in detecting MDD from EEG signals [8].

Pharmaco-EEG in Drug Development

Pharmaco-electroencephalography (Pharmaco-EEG) is the quantitative analysis of EEG to assess the effects of drugs on the central nervous system (CNS) [4]. It plays a vital role in:

- Early Drug Screening: Identifying compounds with potential therapeutic effects by characterizing their impact on brain activity [8].

- Mechanism Insight: Different drug classes produce distinct, reproducible EEG "fingerprints". For instance, benzodiazepines typically increase beta activity, while many sedatives cause EEG slowing (increased delta/theta) [4] [2].

- Dose Optimization and Toxicity Monitoring: Pharmaco-EEG can help establish the therapeutic window and detect neurotoxic effects, such as excessive background slowing, associated with high drug concentrations [4] [2].

The table below summarizes the EEG responses to selected antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), illustrating how pharmaco-EEG can link drug mechanisms to measurable CNS effects.

Table 4: EEG Frequency Responses to Selected Antiepileptic Drugs (AEDs)

| Drug | Primary Mechanism | Typical EEG Frequency Effect | Clinical/Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethosuximide | Blocks T-type Calcium channels | Decrease in Delta, Increase in Alpha [4] | Used for absence seizures; effect on background rhythm. |

| Carbamazepine | Blocks Sodium channels | Increase in Delta and Theta [4] | Slowing can be observed. |

| Benzodiazepines | Potentiates GABA-A receptors | Pronounced increase in Beta activity [4] | Marker of drug engagement and sedative effect. |

| Phenytoin | Blocks Sodium channels | Increase in Beta; Slowing at toxic doses [4] | Can indicate toxicity. |

Electroencephalography (EEG) measures electrical brain activity with high temporal resolution, making it invaluable for neuroscience research and clinical diagnostics. However, its utility is challenged by several inherent signal characteristics. This application note details three fundamental properties of EEG signals—non-stationarity, low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and individual variability—that are critical for designing robust deep learning models for EEG classification. We frame these characteristics not merely as obstacles but as informative features that, when properly modeled, can enhance the performance and generalizability of analytical frameworks. The protocols and data summaries provided herein are tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in computational analysis of neural data.

Characteristic 1: Non-Stationarity

Definition & Quantitative Profile

Non-stationarity refers to the temporal evolution of the statistical properties (e.g., mean, variance, frequency content) of an EEG signal. Rather than being a continuous, stable process, the EEG is considered a piecewise stationary signal, composed of a sequence of quasi-stable patterns or "metastable" states [10]. The signal's properties can change due to shifts in cognitive task engagement, attention levels, fatigue, and underlying brain state dynamics [11].

Table 1: Quantitative Profile of EEG Non-Stationarity

| Metric | Typical Range/Value | Context & Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Stationary Segment Duration | 0.5 - 4 seconds [12] | Defines the window for reliable statistical estimation; shorter segments challenge traditional analysis. |

| Quasi-Stationary Segment Duration | ~0.25 seconds [11] | Relevant for Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) systems; defines the time scale of stable patterns in dynamic tasks. |

| Age-Related Change in Non-Stationarity | Number of states increases; segment duration decreases with age during adolescence [10] | Indicates brain maturation; analytical models must account for age-dependent dynamical properties. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Dynamical Non-Stationarity

This protocol outlines a method for quantifying dynamical non-stationarity in resting-state or task-based EEG data, suitable for investigating developmental trends or clinical group differences [10].

Workflow Overview:

Title: Dynamical Non-Stationarity Assessment Workflow

Step-by-Step Procedures:

Data Acquisition & Preprocessing:

- Acquire EEG data using a standard system (e.g., 128-channel Geodesic Sensor Net).

- Apply standard preprocessing: band-pass filtering (e.g., 0.5-70 Hz), re-referencing to average reference, and artifact correction for blinks and eye movements using Independent Component Analysis (ICA). Remove epochs with persistent artifacts [10].

Segmentation of Time Series:

- Divide the continuous, artifact-free EEG time series into short, possibly overlapping, segments.

- Recommended Segment Length: 0.5 to 2 seconds, based on the expected duration of quasi-stationary states [12].

Modeling and Feature Extraction:

- Fit a model (e.g., an Autoregressive (AR) model) to each segment to approximate the underlying dynamics.

- Extract features from the model (e.g., the coefficients of the AR model) that characterize the signal's properties within that segment [10].

Clustering of Segments:

- Apply a clustering algorithm (e.g., k-means) to the extracted features from all segments.

- Each resulting cluster represents a distinct "stationary state"—a type of brain dynamic that recurs over time.

Quantification of Non-Stationarity:

- Calculate the following key metrics from the clustering results:

- Number of States: The total number of distinct clusters identified. An increase signifies greater dynamical complexity.

- Mean Duration of Stationary Segments: The average time the signal remains in one state before transitioning. A decrease signifies faster switching and higher non-stationarity [10].

- Calculate the following key metrics from the clustering results:

Characteristic 2: Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio

Definition & Noise Source Profile

The EEG signal is notoriously weak, measured in microvolts (millionths of a volt), leading to a low SNR. "Noise" in EEG refers to any recorded signal not originating from the brain activity of interest, significantly complicating data interpretation [13].

Table 2: Profile of Primary Noise Sources in EEG Recordings

| Noise Category | Specific Sources | Characteristics & Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Physiological | Ocular signals (EOG), Cardiac signals (ECG), Muscle contractions (EMG), Swallowing, Irrelevant brain activity [14] | Signals are often 100 times larger than brain-generated EEG; create large-amplitude, stereotypical artifacts that can obscure neural signals [13]. |

| Environmental | AC power lines (50/60 Hz), Room lighting, Electronic equipment (computers, monitors) [14] | Emit electromagnetic fields that are easily detected by sensitive EEG sensors, introducing periodic noise. |

| Motion Artifacts | Unstable electrode-skin contact, Movement of electrode cables [14] | Causes large, low-frequency signal drifts or abrupt signal changes, potentially invalidating data segments. |

Experimental Protocol: Comprehensive SNR Optimization

This protocol provides a multi-stage approach to maximize SNR, encompassing procedures before, during, and after EEG recording.

Workflow Overview:

Title: End-to-End SNR Optimization Pipeline

Step-by-Step Procedures:

Phase 1: Before Recording (Preventive Measures)

- Experimental Design:

- For Event-Related Potential (ERP) studies, design a protocol with sufficient trial repetitions to leverage averaging, which cancels out random noise [13].

- Keep participants focused and comfortable to minimize internal noise and movement artifacts. Provide breaks to allow for blinking and readjustment [13].

- Environmental Control:

- Use a Faraday cage, if available, for electromagnetic isolation [14].

- Remove or turn off non-essential electronic equipment. Replace AC-powered devices with DC alternatives where possible.

- Participant Preparation:

- Ensure the participant is in a comfortable, resting position.

Phase 2: During Recording (Monitoring & Control)

- Electrode Management:

- Quality Control:

- Measure and verify electrode impedances before recording starts. Lower impedance values (typically < 50 kΩ) indicate better contact and signal quality [14].

Phase 3: After Recording (Mathematical Cleaning)

- Manual Inspection: Visually inspect the plotted data to identify obvious artifacts and assess overall data quality [14].

- Algorithmic Cleaning: Apply one or more advanced signal processing techniques:

- Independent Component Analysis (ICA): A blind source separation technique effective for isolating and removing stereotypical artifacts like eye blinks (EOG) and muscle activity (EMG) [14].

- Artifact Subspace Reconstruction (ASR): An online, component-based method for removing large-amplitude, transient artifacts by contrasting data segments to a calibration baseline [14].

- Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA): Separates signal from noise based on autocorrelation, often outperforming ICA in certain scenarios and usable in real-time [14].

- Sensor Noise Suppression (SNS): Improves SNR by projecting each channel's signal onto the subspace of its neighboring channels, effectively removing unique, non-brain noise [14].

Characteristic 3: Individual Variability

Definition & Quantitative Profile

EEG signals exhibit substantial differences between individuals. This variability is not merely noise but is driven by stable, subject-specific neurophysiological factors. Critically, this subject-driven variability can be more pronounced than the variability induced by task demands [15] [16].

Table 3: Profile of Individual Variability in EEG

| Aspect of Variability | Manifestation | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Across-Subject vs. Across-Block Variation | Across-subject variation in EEG variability and signal strength is much stronger than across-block (task) variation within subjects [15] [16]. | Deep learning models trained on pooled data are prone to learning subject-specific identifiers rather than task-general features, hindering generalization. |

| Relationship to Behavior | Individual differences in behavior (e.g., response times) are better reflected in individual differences in EEG variability, not signal strength [15] [16]. | Signal variability itself is a meaningful biomarker for individual cognitive performance and should be modeled as a feature. |

| Long-Term Stability | Key EEG features (e.g., absolute/relative power in alpha band) show high test-retest reliability over weeks and even years (correlation coefficients ~0.84 over 12-16 weeks) [17]. | Subject-specific signatures are stable over time, validating the use of individual baselines or subject-adaptive models. |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Subject-Driven Variability

This protocol is designed to systematically quantify and isolate subject-driven variability from task-driven changes in EEG data, which is essential for building generalizable classifiers.

Workflow Overview:

Title: Isolating Subject-Driven Variability Protocol

Step-by-Step Procedures:

Data Collection:

Calculation of Trial-Level Metrics:

- For each trial and participant, calculate two primary types of metrics in overlapping time windows:

Variance Partitioning:

- Perform a systematic analysis to determine the relative sensitivity of the calculated metrics to different sources of variation.

- Compare the magnitude of across-subject variation (differences between people within the same task block) to across-block variation (differences within the same person across different task blocks) [15] [16]. The finding that across-subject variation dominates confirms a strong subject-driven signal.

Linking EEG Metrics to Behavior:

- Correlate individual differences in the EEG metrics (both strength and variability) with individual differences in behavioral performance (e.g., average response time, accuracy).

- Determine which EEG metric (strength or variability) is a stronger predictor of behavior. Research indicates that EEG variability often reflects stable subject identity and is a superior correlate of behavior compared to signal strength [15] [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

| Tool/Solution | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density EEG System (e.g., 128+ channels) | Captures detailed spatial information of brain electrical activity. | Source localization; high-resolution spatial analysis; Sensor Noise Suppression (SNS). |

| Faraday Cage / Electromagnetically Shielded Room | Blocks environmental electromagnetic interference. | Critical for maximizing SNR in studies not involving movement, especially with sensitive equipment [14]. |

| Wet Electrodes with Conductive Gel | Ensures low impedance and stable electrical contact with the scalp. | The gold standard for high-quality, low-noise recordings; superior to most dry electrodes for SNR [14] [13]. |

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) | Blind source separation for isolating and removing biological artifacts. | Post-processing cleanup of ocular (EOG) and muscular (EMG) artifacts [14] [10]. |

| Artifact Subspace Reconstruction (ASR) | Statistical, component-based method for removing large, transient artifacts. | Online or offline data cleaning; particularly effective for handling large-amplitude, non-stereotypical noise [14]. |

| Covariate Shift Estimation (e.g., EWMA Model) | Detects changes in the input data distribution of streaming EEG features. | Active adaptation in non-stationary learning for BCIs; triggers model updates when a significant shift is detected [11]. |

| Adaptive Ensemble Learning | Maintains and updates a pool of classifiers to handle changing data distributions. | Used in conjunction with covariate shift detection in BCI systems to maintain performance over long sessions [11]. |

The analysis of Electroencephalography (EEG) signals has undergone a profound transformation, moving from traditional machine learning (ML) methods reliant on handcrafted features to deep learning (DL) approaches that automatically learn hierarchical representations from raw data. This paradigm shift addresses the inherent challenges of EEG signals: their non-stationary nature, low signal-to-noise ratio, and complex spatiotemporal dependencies [3]. Traditional ML pipelines required extensive domain expertise for feature extraction (e.g., using wavelet transform or Fourier analysis) before classification with models like Support Vector Machines (SVM) [18] [3]. In contrast, deep learning models, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), directly process raw or minimally preprocessed signals, learning both relevant features and classifiers in an end-to-end manner [18] [19]. This shift has significantly enhanced performance in critical applications ranging from epilepsy seizure detection and motor imagery classification to lie detection, thereby accelerating research in neuroscience, clinical diagnostics, and drug development.

Comparative Analysis: Quantitative Performance

The superiority of deep learning architectures is evidenced by their consistently higher performance metrics across diverse EEG classification tasks compared to traditional machine learning methods. The tables below summarize this performance leap.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of ML vs. DL Models on Specific EEG Tasks

| Task | Traditional ML Model | Accuracy | Deep Learning Model | Accuracy | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lie Detection | SVM | Information Missing | CNN | 99.96% | [20] |

| Lie Detection | Linear Discriminant Analysis | 91.67% | Deep Neural Network | Information Missing | [20] |

| Motor Imagery | Various Shallow Models | Information Missing | Fast BiGRU + CNN | 96.9% | [21] |

| Seizure Detection | Models with Handcrafted Features | ~90% (Est.) | CNN, RNN, Transformer | >90% (Common) | [22] |

Table 2: Strengths and Weaknesses of Model Archetypes in EEG Analysis

| Aspect | Traditional Machine Learning | Deep Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Feature Engineering | Manual, requires expert domain knowledge [18] [3] | Automatic, learned from data [18] |

| Computational Cost | Lower | Higher |

| Data Requirements | Lower | Large datasets required |

| Interpretability | Higher (transparent features) | Lower ("black-box" nature) |

| Handling Raw Data | Poor, requires pre-processing | Excellent, can use raw data |

| Spatiotemporal Feature Learning | Limited, often separate | Superior, integrated (e.g., CNN+RNN) [21] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: CNN for EEG-Based Lie Detection

This protocol outlines the methodology for achieving state-of-the-art lie detection using a Convolutional Neural Network, as detailed in recent research [20].

- Aim: To classify EEG signals into "truthful" and "deceptive" categories with high accuracy.

- Dataset: A novel dataset acquired from 10 participants using a 14-channel OpenBCI Ultracortex Mark IV EEG headset.

- Experimental Design: A video-based protocol using the Comparison Question Test (CQT) technique. Participants watched clips of a theft crime and were asked to answer questions truthfully in one session and deceptively in another.

- Data Acquisition: EEG signals were recorded from 14 electrodes (FP1, FP2, F4, F8, F7, C4, C3, T8, T7, P8, P4, P3, O1, O2) according to the international 10-20 system, with a sampling frequency of 125 Hz.

- Preprocessing: The raw signals were preprocessed to remove noise and artifacts.

- Model Architecture & Training:

- The preprocessed signals were fed into a CNN model.

- The CNN automatically learned discriminative spatial features from the multi-channel EEG inputs.

- Performance: The model achieved an accuracy of 99.96% on the custom dataset and 99.36% on a public benchmark (Dryad dataset), outperforming traditional ML models like SVM and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) tested in the same study [20].

Protocol 2: BiGRU-CNN for Motor Imagery Classification

This protocol describes a hybrid deep learning model that captures both spatial and temporal features for classifying imagined movements [21].

- Aim: To decode and classify motor imagery EEG signals into one of four classes: left hand, right hand, both feet, and tongue movement.

- Dataset: BCI Competition IV, Dataset 2a, containing recordings from 22 EEG electrodes.

- Preprocessing: Signals were normalized, and a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) was applied to obtain frequency components. The data was segmented into small, overlapping time windows.

- Model Architecture & Training:

- A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) processed the input to extract spatial features from the EEG channels, identifying local wave patterns.

- A Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (BiGRU) analyzed the sequence of features extracted by the CNN to capture long-range temporal dependencies and contextual information in the brain activity.

- The model was trained end-to-end to classify the four motor imagery tasks.

- Performance and Robustness:

- The baseline Fast BiGRU + CNN model achieved 96.9% accuracy.

- Ablation studies confirmed the contribution of both architectural components.

- Data augmentation techniques (Gaussian noise, channel dropout, mixup) were employed to test robustness, revealing that while accuracy on clean data was highest for the baseline, augmented models showed improved resistance to noise [21].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental shift in the EEG analysis pipeline from a traditional machine learning approach to a deep learning paradigm.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers embarking on EEG deep learning projects, the following tools and resources are essential.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for Deep Learning EEG Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| OpenBCI Ultracortex Mark IV | Hardware | A relatively low-cost, open-source EEG headset for data acquisition; used in lie detection studies with 14-16 channels [20]. |

| EEG-DL Library | Software | A dedicated TensorFlow-based deep learning library providing implementations of latest models (CNN, ResNet, LSTM, Transformer, GCN) for EEG signal classification [19]. |

| BCI Competition IV 2a | Data | A benchmark public dataset for motor imagery classification, containing 22-channel EEG data for 4 classes of movement imagination [21]. |

| Dryad Dataset | Data | A public dataset for lie detection research, employing a standard three-stimuli protocol with image-based stimuli [20]. |

| WebAIM Contrast Checker | Tool | Ensures accessibility and readability of visual results and interface elements in developed tools by verifying color contrast ratios against WCAG guidelines [23]. |

| Transformers & Attention Mechanisms | Algorithm | A class of models gaining attention for seizure detection and iEEG classification, excelling at modeling complex temporal dependencies [22]. |

Electroencephalogram (EEG) analysis plays an indispensable role across contemporary medical applications, encompassing diagnosis, monitoring, drug discovery, and therapeutic assessment [8]. The advent of deep learning has revolutionized EEG analysis by enabling end-to-end decoding directly from raw signals without hand-crafted features, achieving performance that matches or exceeds traditional methods [24]. Deep learning models automatically learn hierarchical representations that capture relevant spectral and spatial patterns in EEG data, making them particularly valuable for analyzing the high-dimensional, multivariate nature of neural signals [8]. This document presents application notes and experimental protocols for five major EEG classification tasks, framed within the context of advanced deep learning approaches for biomedical research and neuropharmacology.

Experimental Protocols & Performance Benchmarks

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks for Major EEG Classification Tasks

| Classification Task | Key Applications | Best-Performing Models | Reported Accuracy | Key EEG Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication Classification | Pharmaco-EEG, therapeutic monitoring | Deep CNN (DCNN), Kernel SVM [25] | 72.4-77.8% [25] | Spectral power across frequency bands |

| Motor Imagery | Brain-computer interfaces, neurorehabilitation | CSP with LDA, EEGNet, CTNet [26] [27] | Varies by dataset | Sensorimotor rhythms (mu/beta), ERD/ERS |

| Seizure Detection | Epilepsy monitoring, alert systems | Convolutional Sparse Transformer [8] | Superior to approaches [8] | Spike-wave complexes, rhythmic discharges |

| Sleep Stage Scoring | Sleep disorder diagnosis | Attention-based Deep Learning [26] | Varies by dataset | Delta waves, spindles, K-complexes |

| Pathology Detection | Clinical diagnosis, screening | EEG-CLIP, Deep4 Network [24] | Zero-shot capability [24] | Non-specific aberrant patterns |

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Medication Classification Protocol

Objective: To distinguish between patients taking anticonvulsant medications (Dilantin/phenytoin or Keppra/levetiracetam) versus no medications based solely on EEG signatures [25].

Dataset Preparation:

- Utilize Temple University Hospital EEG Corpus with physician report verification [25]

- Include balanced samples from patients taking Dilantin, Keppra, or no medications

- Preprocess data: bandpass filtering (0.5-70 Hz), artifact removal, segmentation into 5-second epochs

Experimental Procedure:

- Feature-Based Approach:

- Extract spectral features: power spectral density across delta, theta, alpha, beta, gamma bands

- Apply K-best feature selection or Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction

- Train Kernel SVM with RBF kernel (C=10-1000, γ=0.1) using 10-fold cross-validation [25]

- Deep Learning Approach:

- Implement Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN) with spatial-temporal layers

- Configure architecture: 4 convolutional blocks with batch normalization and dropout

- Train with Adam optimizer (learning rate=0.001) for 100 epochs with early stopping [25]

Validation:

- Perform 10-fold cross-validation with strict patient-wise splitting

- Compare results against random label baseline using Kruskal-Wallis tests

- Report accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and computational efficiency metrics

Motor Imagery Classification Protocol

Objective: To decode imagined movements from sensorimotor rhythms for brain-computer interface applications [27].

Experimental Setup:

- Electrode Selection: Focus on C3, C4, and Cz channels per international 10-20 system [27]

- Time Window: 3-second segments with 0.5-second offset [27]

- Task Paradigm: Randomly cued imagination of right hand vs. left hand movement

Signal Processing Pipeline:

- Preprocessing:

- Apply 8-30 Hz bandpass filter to enhance sensorimotor rhythms

- Perform Common Spatial Pattern (CSP) or Independent Component Analysis (ICA) for source separation [27]

Feature Extraction:

- Calculate log-variance of CSP components

- Extract Renyi entropy for non-linear characterization [27]

Classification:

Multimodal EEG-Text Embedding Protocol (EEG-CLIP)

Objective: To align EEG time-series data with clinical text descriptions in a shared embedding space for versatile zero-shot decoding [24].

Architecture Configuration:

- EEG Encoder: Deep4 CNN (4 convolution-max-pooling blocks with batch normalization) [24]

- Text Encoder: Pretrained BERT model for clinical report processing [24]

- Projection Heads: 3-layer MLP with ReLU activations projecting to 64-dimensional shared space [24]

Training Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Contrastive Learning:

- Implement symmetric contrastive loss using cosine similarity

- Train with Adam optimizer (learning rate=5×10⁻³, weight decay=5×10⁻⁴) for 20 epochs [24]

- Batch size: 64 with hard negative mining

Evaluation:

- Zero-shot classification using textual prompts for pathology, age, gender, medication

- Few-shot transfer learning on downstream tasks with limited labeled data

- t-SNE visualization of cross-modal embedding alignment

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

End-to-End EEG Deep Learning Pipeline

EEG-CLIP Multimodal Alignment Architecture

Convolutional Sparse Transformer for EEG Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for EEG Deep Learning

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| EEG Datasets | Temple University Hospital EEG Corpus [24] [25] | Large-scale clinical data with medical reports | Contains >25,000 recordings; includes medication metadata |

| Preprocessing Tools | MNE-Python, EEGLAB | Signal cleaning, filtering, artifact removal | Minimal preprocessing preferred for deep learning [28] |

| Deep Learning Architectures | EEGNet, Deep4, Convolutional Sparse Transformer [8] [26] | Task-specific model backbones | EEGNet: compact CNN; Transformer: long-range dependencies |

| Multimodal Frameworks | EEG-CLIP [24] | Contrastive EEG-text alignment | Enables zero-shot classification from textual prompts |

| Specialized Components | Spatial Channel Attention, Common Spatial Patterns | Enhancing spatial relationships in EEG | Critical for capturing brain region interactions [8] [27] |

| Evaluation Metrics | 10-fold cross-validation, Kruskal-Wallis tests | Statistical validation of model performance | Essential for pharmaco-EEG applications [25] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Pharmaco-EEG and Therapeutic Monitoring

The application of deep learning to Pharmaco-EEG represents a paradigm shift in drug development and therapeutic monitoring. The Convolutional Sparse Transformer framework demonstrates remarkable versatility across multiple medical tasks, including disease diagnosis, drug discovery, and treatment effect prediction [8]. By directly processing raw EEG waveforms, this approach captures intricate spatial-temporal patterns that serve as biomarkers for drug efficacy. For anticonvulsant medications, studies show that differential classification between Dilantin and Keppra is achievable with accuracies around 72-74% using Random Forest classifiers, while Deep CNN models achieve 77.8% accuracy when distinguishing medicated patients from controls [25].

Zero-Shot Learning and Cross-Modal Applications

The EEG-CLIP framework pioneers zero-shot classification capabilities by aligning EEG signals with natural language descriptions of clinical findings [24]. This approach enables researchers to query EEG data using textual prompts without task-specific training, opening new possibilities for exploratory analysis and hypothesis testing. The contrastive learning objective brings matching EEG-text pairs closer in the embedding space while pushing non-matching pairs apart, creating a semantically rich representation space that captures fundamental relationships between neural patterns and their clinical interpretations [24].

Methodological Considerations and Preprocessing Impact

Recent evidence suggests that extensive preprocessing pipelines may not always benefit deep learning models, with minimal preprocessing (excluding artifact handling methods) often yielding superior performance [28]. This counterintuitive finding emphasizes the importance of evaluating preprocessing strategies within the context of specific classification tasks and model architectures. Models trained on completely raw data consistently perform poorly, indicating that basic filtering and normalization remain essential, while sophisticated artifact removal algorithms may inadvertently remove task-relevant information [28].

Deep Learning Architectures and Their Transformative Applications in EEG Classification

Deep learning architectures have revolutionized electroencephalography (EEG) analysis by enabling automated feature extraction and enhanced classification of complex brain activity patterns. The selection of an appropriate model is critical for tasks such as motor imagery classification, seizure detection, and emotion recognition [29]. The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and typical applications of each major architecture in EEG research.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Deep Learning Architectures for EEG Classification

| Architecture | Core Mechanism | Key Advantages for EEG | Primary Limitations | Common EEG Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [30] | Convolutional and pooling layers for spatial feature extraction [30]. | Excels at identifying spatial patterns and hierarchies from multi-channel electrode data [29]. | Limited innate capacity for modeling temporal dependencies and long-range contexts [29]. | Motor Imagery classification, spatial feature extraction from scalp topographies [31] [32]. |

| RNN / LSTM [30] | Gated units (input, forget, output) to regulate information flow in sequences [30] [33]. | Effectively models temporal dynamics and dependencies in EEG time-series [29]. Handles vanishing gradient problem better than simple RNNs [33]. | Sequential processing limits training parallelization, making it computationally intensive [30] [34]. | Emotion recognition, seizure detection, and other tasks with strong temporal dependencies [29]. |

| Transformer [29] | Self-attention mechanism to weigh the importance of all time points in a sequence [29]. | Superior at capturing long-range dependencies in EEG signals. Enables full parallelization for faster training [29] [33]. | Requires very large datasets; computationally expensive and memory-intensive [30] [29]. | State-of-the-art performance in Motor Imagery, Emotion Recognition, and Seizure Detection [29]. |

Empirical studies demonstrate the performance of these architectures in specific EEG classification tasks. The following table consolidates quantitative results from recent research, providing a benchmark for model selection.

Table 2: Reported Performance of Different Architectures on EEG Classification Tasks

| Model Architecture | EEG Task / Dataset | Reported Performance | Key Experimental Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (Baseline) [32] | Motor Imagery / PhysioNet | 91.00% Accuracy | Traditional machine learning benchmark with handcrafted features [32]. |

| CNN [32] | Motor Imagery / PhysioNet | 88.18% Accuracy | Used for spatial feature extraction [32]. |

| LSTM [32] | Motor Imagery / PhysioNet | 16.13% Accuracy | Struggled with temporal modeling in this specific setup [32]. |

| CNN-LSTM (Hybrid) [32] | Motor Imagery / PhysioNet | 96.06% Accuracy | Combined spatial (CNN) and temporal (LSTM) feature learning [32]. |

| Proposed Multi-Stage Model [35] | Depression Classification / PRED+CT Dataset | 85.33% Accuracy | Integrated cortical source features, Graph CNN, and adversarial learning [35]. |

| Signal Prediction Method [36] | Motor Imagery / BCI Competition IV 2a | 78.16% Average Accuracy | Used elastic net regression to predict full-channel EEG from a few electrodes [36]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Architectures

Protocol: CNN-LSTM Hybrid Model for Motor Imagery Classification

This protocol outlines the procedure for implementing a high-performing hybrid CNN-LSTM model, which has demonstrated state-of-the-art accuracy of 96.06% in classifying Motor Imagery tasks [32].

Primary Objective: To accurately classify EEG signals into different motor imagery classes (e.g., left hand vs. right hand movement) by leveraging the spatial feature extraction capability of CNNs and the temporal modeling strength of LSTMs.

Materials and Dataset

- Dataset: PhysioNet EEG Motor Movement/Imagery Dataset [32].

- Software: Python with deep learning libraries (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch).

- Pre-processing Tools: Band-pass filters, Independent Component Analysis (ICA) for artifact removal, and normalization utilities.

Experimental Procedure

- Data Preprocessing:

- Apply a band-pass filter (e.g., 4-40 Hz) to isolate relevant frequency bands like Mu and Beta rhythms.

- Remove ocular and muscular artifacts using ICA.

- Segment the continuous EEG data into epochs time-locked to the motor imagery cue.

- Normalize the data per channel to have zero mean and unit variance.

- Model Architecture Configuration:

- CNN Component: Design convolutional layers to process the multi-channel EEG input. Use 2D convolutions to capture spatial patterns across electrodes or 1D convolutions for temporal patterns per channel.

- LSTM Component: Feed the feature sequences extracted by the CNN into an LSTM layer to model temporal dependencies.

- Classification Head: Attach a fully connected layer with a softmax activation function to output class probabilities.

- Model Training:

- Loss Function: Categorical cross-entropy.

- Optimizer: Adam.

- Training Regimen: Train for 30-50 epochs, which is sufficient for the model to converge to peak accuracy in this application [32].

- Performance Validation:

- Evaluate the model on a held-out test set using accuracy as the primary metric.

- Compare performance against traditional machine learning classifiers (e.g., Random Forest) and individual CNN/LSTM models.

- Data Preprocessing:

The workflow for this hybrid approach is summarized in the diagram below.

Protocol: Transformer-based Model for Multi-class EEG Analysis

This protocol describes the application of Transformer architectures, which are increasingly used for their superior ability to handle long-range dependencies in EEG sequences [29].

Primary Objective: To implement a Transformer model for EEG-based classification tasks such as motor imagery, emotion recognition, or seizure detection, leveraging self-attention to capture global context.

Materials and Dataset

- Dataset: Varies by task (e.g., BCI Competition IV 2a for Motor Imagery, DEAP for Emotion recognition) [29] [26].

- Software: Python with PyTorch/TensorFlow and Transformer model libraries.

- Feature Engineering Tools: Optional tools for generating input embeddings (e.g., spectral features, visibility graphs [31]).

Experimental Procedure

- Input Representation and Embedding:

- Represent the multi-channel EEG signal as a sequence of vectors. This can be raw data points, extracted features, or data from individual time points.

- Project the input into a higher-dimensional space using a linear embedding layer.

- Inject positional information into the embeddings using sinusoidal positional encoding, as Transformers themselves are permutation-invariant [29].

- Core Transformer Encoder Configuration:

- Multi-Head Self-Attention: Configure multiple attention heads to allow the model to focus on different aspects of the EEG sequence from different representation subspaces [29].

- Feed-Forward Network: Each encoder layer should contain a position-wise fully connected feed-forward network.

- Residual Connections & Layer Normalization: Employ these around both the self-attention and feed-forward sub-layers to stabilize training [29].

- Task-Specific Head and Training:

- Use the output corresponding to a special classification token ([CLS]) or the mean of the output sequence as a summary representation.

- Pass this representation through a linear classifier to obtain final class labels.

- Train the model with cross-entropy loss and an adaptive optimizer like AdamW.

- Input Representation and Embedding:

Protocol: Subject-Independent Semi-Supervised Learning with SSDA

This protocol addresses the critical challenge of inter-subject variability and limited labeled data by using a Semi-Supervised Deep Architecture (SSDA) [37].

Primary Objective: To train a robust motor imagery classification model that generalizes to new, unseen subjects with minimal labeled data.

Materials and Dataset

- Datasets: BCI Competition IV 2a or PhysioNet Motor Movement/Imagery Dataset [37].

- Software: Python with deep learning frameworks.

Experimental Procedure

- Data Preparation:

- Pool data from multiple subjects, keeping a subset of labels and treating the rest as unlabeled.

- Ensure the test set contains only subjects not present in the training set.

- SSDA Model Construction:

- Unsupervised Component (CST-AE): Build a Columnar Spatiotemporal Auto-Encoder (CST-AE) to learn latent feature representations from all training data (both labeled and unlabeled) by reconstructing the input [37].

- Supervised Component: Train a classifier on the latent features from the labeled data only.

- Joint Training with Center Loss:

- Train the entire network end-to-end, combining the reconstruction loss from the auto-encoder and the classification loss from the classifier.

- Incorporate a center loss term to minimize the distance between embedded features of the same class, enhancing intra-class compactity [37].

- Evaluation:

- Evaluate the final model on the held-out test subjects, reporting classification accuracy.

- Data Preparation:

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Deep Learning EEG Analysis

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Example / Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Public EEG Datasets | Provide standardized, annotated data for model training and benchmarking. | PhysioNet EEG Motor Movement/Imagery Dataset [32]; BCI Competition IV 2a [37]; PRED+CT (Depression) [35]. |

| Pre-processing Tools | Clean raw EEG signals by removing noise and artifacts to improve signal quality. | Band-pass & notch filtering; Independent Component Analysis (ICA); Common Average Reference (CAR). |

| Feature Extraction Methods | Transform raw EEG into discriminative features for model input. | Power Spectral Density (PSD) [31]; Wavelet Transform [32]; Visibility Graph (VG) [31]; Riemannian Geometry [32]. |

| Software & Codebases | Open-source implementations of standard and state-of-the-art models. | EEGNet (Keras/TensorFlow) [26]; Vision Transformer for EEG (PyTorch) [26]. |

| Domain Adaptation Techniques | Improve model generalization across subjects or sessions by mitigating data distribution shifts. | Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL) [35]; Focal Loss for class imbalance [35]. |

Electroencephalography (EEG) analysis has been revolutionized by deep learning (DL), which enables the extraction of complex patterns from neural data for tasks ranging from neurological disorder diagnosis to brain-computer interface development [38] [22]. The performance of these DL models is fundamentally dependent on the quality and formulation of input data. This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for EEG data preprocessing and the creation of effective input formulations specifically for deep learning-based classification research. Within the broader context of a thesis on deep learning EEG analysis, this guide serves as an essential methodological bridge between raw signal acquisition and model development, ensuring that researchers can transform noisy, raw EEG signals into structured inputs that maximize model performance and interpretability for applications in scientific research and drug development.

EEG Data Preprocessing Pipeline

Preprocessing is a critical first step that removes contaminants and enhances the signal-to-noise ratio, ensuring that subsequent analysis reflects neural activity rather than artifacts [39] [38]. The following section outlines a standardized, automated pipeline suitable for most research scenarios.

Core Preprocessing Steps

Table 1: Core EEG Preprocessing Steps and Methodologies

| Processing Step | Description | Common Techniques & Parameters | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filtering | Removes unwanted frequency components not relevant to the research question. | - High-pass filter: >0.1 Hz to remove slow drifts [40].- Low-pass filter: <40-80 Hz to suppress muscle noise [40].- Notch filter: 50/60 Hz to eliminate line interference [39]. | A signal focused on the frequency band of interest (e.g., 0.5-40 Hz). |

| Bad Channel Interpolation | Identifies and reconstructs malfunctioning or excessively noisy electrodes. | - Automatic detection: Based on abnormal variance, correlation, or kurtosis.- Interpolation: Using spherical splines or signal averaging from neighboring channels. | A complete channel set with minimal data loss. |

| Artifact Removal | Separates and removes non-neural signals (e.g., from eyes, heart, muscles). | - Independent Component Analysis (ICA): Fitted on filtered data (e.g., 1-40 Hz) to isolate and remove artifact-related components [40].- Automated algorithms: Such as ASR or ICLabel. | A "clean" EEG signal predominantly reflecting cortical origin activity. |

| Epoching | Segments the continuous data into trials time-locked to experimental events. | - Time window: e.g., -0.2 s to +0.8 s around stimulus onset.- Baseline correction: Removes mean DC offset using the pre-stimulus period. | A 3D matrix (epochs × channels × time points) ready for feature extraction. |

| Normalization | Scales the data to a standard range, improving model training stability. | - Z-scoring: Subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation per channel [38].- Robust Scaler: Uses median and interquartile range to mitigate outlier effects. | Data with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, or similar bounded range. |

Visualizing the Preprocessing Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential workflow of the standard EEG preprocessing pipeline.

Input Formulations for Deep Learning

Choosing how to represent EEG data is as crucial as the model architecture itself. Deep learning models can ingest EEG data in various formulations, each with distinct advantages for capturing different aspects of the signal.

Table 2: Comparison of Input Formulations for Deep Learning Models

| Input Formulation | Description | Strengths | Weaknesses | Best-Suited Model Architectures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Signals | The preprocessed but otherwise unmodified time-series voltage data. | - Preserves complete temporal information.- No feature engineering bias.- Suitable for end-to-end learning. | - High dimensionality.- Susceptible to high-frequency noise.- Requires large datasets. | 1D Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Transformers [22]. |

| Spectrograms | A time-frequency representation showing power spectral density (PSD) over time, with power encoded as color [41]. | - Provides a 2D image-like input.- Intuitive visualization of spectral evolution.- Effective for capturing oscillatory patterns. | - Loss of phase information.- Time-frequency resolution trade-off. | 2D Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [41]. |

| Time-Frequency Representations (TFRs) | A group of methods that capture both time and frequency details, such as those generated by wavelet transforms [39] [38]. | - Retains both amplitude and phase information.- Superior resolution for transient events compared to spectrograms. | - Computationally intensive.- Can be high-dimensional. | 2D CNNs, Hybrid CNN-RNNs. |

| Handcrafted Features | Engineered features extracted from the signal (e.g., band power, connectivity metrics, Hjorth parameters). | - Low dimensionality.- Incorporates domain knowledge.- Works with smaller datasets. | - Limited to known phenomena; may miss complex patterns.- Requires expert knowledge. | Support Vector Machines (SVM), k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), Fully Connected Neural Networks [39]. |

Generating a Spectrogram Input

Spectrograms are a central tool in quantitative EEG, transforming a 1D signal into a 2D map where time is on the x-axis, frequency on the y-axis, and signal power is represented by color intensity [41]. This makes them ideal for input into standard 2D CNNs.

Protocol 1: Creating an EEG Spectrogram

- Segment the Signal: Divide the continuous preprocessed EEG signal into overlapping time windows (e.g., 2-second segments with 50% overlap). The choice of window length represents a trade-off between temporal and frequency resolution.

- Apply Fourier Transform: For each time window, compute the Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT). This calculates the power spectral density (PSD) for the frequencies within that window.

- Compute Power: Calculate the magnitude squared of the STFT result to obtain the signal power for each frequency bin.

- Plot the Spectrogram: Display time on the x-axis, frequency on the y-axis, and power as a color gradient. Power is often displayed on a logarithmic scale (decibels) to better visualize both low and high-power components [41].

The diagram below illustrates this process and the resulting data structure.

Advanced Time-Frequency Analysis

For detecting transient events with distinct shapes, such as epileptic spikes, or for precisely localizing activity in both time and frequency, more advanced TFRs are required [39] [41]. The Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) is a powerful method for this purpose.

Protocol 2: Implementing Time-Frequency Analysis with Wavelet Transform

- Select a Mother Wavelet: Choose an appropriate wavelet function (e.g., Morlet wavelet) that matches the characteristics of the signal feature of interest.

- Convolve and Transform: Convolve the selected wavelet with the EEG signal at various scales (dilations and translations). Each scale corresponds to a specific frequency band.

- Generate Time-Frequency Map: The output of the CWT is a matrix representing the similarity (coefficient magnitude) between the signal and the wavelet at each time and scale (frequency). This creates a detailed time-frequency map.

- Model Input: The resulting 2D representation (Time × Frequency) of coefficients can be used as input for a 2D CNN, similar to a spectrogram, but often with richer detail for transient features.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Resources for EEG Deep Learning Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| MNE-Python | An open-source Python package for exploring, visualizing, and analyzing human neurophysiological data [42] [40]. | It provides end-to-end functionality, from data I/O and preprocessing (filtering, ICA, epoching) to source localization and statistical analysis. |

| eLORETA | A source localization algorithm used to estimate the cortical origins of scalp-recorded EEG signals [43]. | Estimating the neural sources of a cognitive task or pathological activity (e.g., epileptogenic zone) when individual structural MRIs are unavailable. |

| ICBM 2009c Template & CerebrA Atlas | Standardized anatomical brain templates and atlases [43]. | Used as a shared forward model in source localization pipelines for studies without subject-specific structural data. |

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) | A blind source separation technique used to isolate and remove artifacts like eye blinks and muscle activity from EEG data [40]. | Cleaning continuous EEG data by identifying and rejecting components correlated with artifacts, preserving neural signals. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | A classical machine learning algorithm effective for classification tasks with high-dimensional data [39]. | A strong baseline model for classifying EEG epochs or extracted features (e.g., PSD) into different cognitive states or conditions. |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | A class of deep neural networks most commonly applied to analyzing visual imagery, making it suitable for 2D EEG inputs like spectrograms and TFRs [22]. | Automating the detection of seizures from spectrograms or identifying event-related potentials (ERPs) from time-series data. |

| Transformer Architecture | A modern deep learning architecture that uses self-attention mechanisms to weigh the importance of different parts of the input sequence [22]. | Modeling long-range dependencies in raw or segmented EEG time-series for seizure prediction or cognitive state decoding. |

Experimental Protocol: A Sample Classification Workflow

This protocol provides a concrete example of applying the above methodologies to a typical EEG classification problem, such as distinguishing between different cognitive states.

Protocol 3: Experiment on Cognitive State Classification from EEG Spectrograms

- Objective: To classify epochs of EEG data into "Eyes Open" vs. "Eyes Closed" resting states using a 2D CNN.

- Dataset: A publicly available dataset containing resting-state EEG recordings with annotated "Eyes Open" and "Eyes Closed" conditions.

Procedure:

Data Preprocessing:

- Load the continuous EEG data.

- Apply a band-pass filter (e.g., 1-40 Hz) and a 50/60 Hz notch filter.

- Run ICA to remove eye-blink and other ocular artifacts.

- Epoch the data into 4-second segments from both conditions.

- Apply a baseline correction if necessary (though less critical for resting-state analysis compared to ERPs).

Input Formulation:

- For each 4-second epoch and for each EEG channel (or a subset of posterior channels like Pz, O1, Oz, O2), compute the spectrogram using STFT.

- Use a window size of 1 second with 90% overlap to balance resolution.

- Stack the spectrograms from individual channels to create a multi-channel image input (Channels × Frequency × Time). Alternatively, average spectrograms across a channel group.

Model Training & Evaluation:

- Model: Design a 2D CNN with layers for convolution, pooling, dropout (for regularization), and a final softmax output layer.

- Training: Split data into training, validation, and test sets. Train the CNN to minimize cross-entropy loss using an optimizer like Adam.

- Evaluation: Report standard performance metrics on the held-out test set, including accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F1-score.

This structured approach to preprocessing and input formulation provides a reproducible foundation for building robust and high-performing deep learning models in EEG research.

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder affecting approximately 65 million people worldwide, with about one-third of patients developing drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE) where anti-seizure medications provide inadequate seizure control [22] [44]. For these patients, surgical intervention remains a potentially curative option, with its success critically dependent on the accurate identification and complete resection of the epileptogenic zone (EZ)—the smallest cortical region whose removal results in seizure freedom [22]. Intracranial EEG (iEEG) monitoring is essential for EZ localization but generates massive datasets that are subject to significant inter-expert variability during visual analysis, creating substantial subjectivity in surgical planning [22] [45]. Deep learning has emerged as a transformative technology for automating seizure detection and EZ localization from iEEG recordings, offering the potential to reduce diagnostic subjectivity, enhance reproducibility, and ultimately improve surgical outcomes in epilepsy care [22] [46].

Key Electrophysiological Biomarkers

iEEG analysis for epilepsy surgery focuses on several key electrophysiological biomarkers that indicate epileptogenic tissue. High-frequency oscillations (HFOs), particularly in the 80-500 Hz range (categorized as ripples [80-250 Hz] and fast ripples [250-500 Hz]), have emerged as crucial biomarkers thought to represent synchronized neuronal firing within the EZ [22]. These oscillations can occur during both interictal and ictal periods, with HFO-rich regions showing significant overlap with the epileptogenic zone [22]. Other important biomarkers include interictal epileptiform discharges (IEDs) and the dynamic spectral changes, connectivity patterns, and temporal signatures that directly reflect seizure activity during ictal periods [22] [45]. Deep learning approaches are increasingly capable of detecting these traditional biomarkers while also identifying subtle, alternative biomarkers that may not be apparent through visual inspection alone [22].

Table 1: Key Electrophysiological Biomarkers in iEEG Analysis

| Biomarker | Frequency Range | Clinical Significance | Detection Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ripples | 80-250 Hz | Indicate epileptogenic tissue | Distinguishing pathological from physiological HFOs |

| Fast Ripples | 250-500 Hz | Strong correlation with seizure onset zone | Require high-sampling rate iEEG systems |

| Interictal Epileptiform Discharges (IEDs) | Transient spikes/sharp waves | Marker of irritative zone | Can occur independently from seizure onset zone |

| Ictal Patterns | Variable, patient-specific | Direct seizure manifestation | Significant heterogeneity across patients |

Deep Learning Architectures for iEEG Analysis

Various deep learning architectures have been successfully applied to iEEG analysis, each with distinct advantages for capturing spatial and temporal patterns in epileptic activity. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) excel at extracting spatial features from iEEG spectrograms or raw signal patterns [47] [48]. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), particularly those with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Bidirectional LSTM (BiLSTM) units, effectively model temporal dependencies in sequential iEEG data [22] [48]. More recently, transformer-based architectures with self-attention mechanisms have shown promise for capturing long-range dependencies in iEEG signals [22]. Hybrid models that combine CNNs with RNNs (e.g., CNN-BiLSTM) leverage both spatial feature extraction and temporal sequence modeling, often achieving state-of-the-art performance [47] [48].

Performance Comparison

Recent studies demonstrate the effectiveness of these architectures across various seizure analysis tasks. A hybrid CNN-BiLSTM approach applied to ultra-long-term subcutaneous EEG achieved an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.98 and area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC) of 0.50, corresponding to 94% sensitivity with only 1.11 false detections per day [48]. A semi-supervised temporal autoencoder method for iEEG classification achieved AUROC scores of 0.862 ± 0.037 for pathologic vs. normal classification and 0.879 ± 0.042 for artifact detection, demonstrating that semi-supervised approaches can provide acceptable results with minimal expert annotations [45]. Traditional CNN and RNN models frequently exceed 90% accuracy in detecting epileptiform activity, though performance varies significantly based on data quality and preprocessing techniques [22].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Deep Learning Architectures for Seizure Detection

| Architecture | Application | Key Performance Metrics | Data Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNN-BiLSTM [48] | Seizure detection | AUROC: 0.98, Sensitivity: 94%, False detections: 1.11/day | Subscalp EEG |

| Temporal Autoencoder [45] | iEEG classification | AUROC: 0.862 ± 0.037, AUPRC: 0.740 ± 0.740 | Intracranial EEG |

| 1D-CNN with BiLSTM [47] | Multi-class seizure classification | High precision, sensitivity, specificity, F1-score | Scalp EEG |

| Transformer-based [22] | Seizure detection | High accuracy for temporal dependencies | Intracranial EEG |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: CNN-BiLSTM for Seizure Detection

This protocol outlines the methodology for implementing a hybrid CNN-BiLSTM model for seizure detection in long-term EEG monitoring [48].

Data Acquisition & Preprocessing:

- Acquire iEEG data using standard clinical systems with sampling rates ≥ 2000 Hz.

- Apply band-pass filtering (0.5-70 Hz) and notch filtering (50/60 Hz) to remove noise and line interference.

- For subscalp EEG, use two-channel recordings with continuous monitoring over several weeks.

- Segment data into 5-minute epochs with 50% overlap for analysis.

Data Augmentation & Balancing:

- Address class imbalance using K-means Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (K-means SMOTE) [47].

- Augment training data with both scalp EEG and iEEG seizures to improve model generalizability [48].

Model Architecture & Training:

- Implement a 9-layer CNN-BiLSTM hybrid architecture.

- Use CNN layers for spatial feature extraction from channel spectrograms.

- Employ BiLSTM layers to capture bidirectional temporal dependencies.

- Train using Truncated Backpropagation Through Time (TBPTT) to reduce computational complexity [47].

- Utilize both softmax (multi-class) and sigmoid (binary) classifiers at the output layer.

Validation & Testing:

- Perform k-fold cross-validation (typically 10-fold) to assess model robustness.

- Benchmark against conventional spectral power classifier algorithms.

- Evaluate using area under ROC curve (AUROC), area under precision-recall curve (AUPRC), sensitivity, and false detection rate.

Protocol 2: Semi-Supervised iEEG Classification

This protocol describes a semi-supervised approach for iEEG classification using temporal autoencoders, ideal for scenarios with limited expert annotations [45].

Data Preparation:

- Collect iEEG recordings from multiple centers with different acquisition systems.

- Have domain experts annotate a small subset of data (≥100 samples per category) representing physiological activity, pathological activity (IEDs, HFOs), muscle artifacts, and power line noise.

- Segment iEEG signals into 3-second windows (15,000 samples at 5 kHz sampling rate).

Temporal Autoencoder Implementation:

- Utilize a temporal autoencoder with self-attention mechanism for dimensionality reduction.

- Train the autoencoder in unsupervised fashion on large-scale unlabeled iEEG datasets.

- Project time series data points into low-dimensional embedding space.

Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) Mapping:

- Apply KDE maps to the embedding space using the limited expert-provided labels.

- Implement an active learning approach where the model suggests samples for expert review to refine class boundaries.

Pseudo-Prospective Validation:

- Test the model on novel patients in a pseudo-prospective framework.

- Use 30-minute resting-state recordings for IED detection as per clinical HFO evaluation protocols.

- Evaluate performance using AUROC and AUPRC metrics on the natural prevalence of IEDs in continuous recordings.

Diagram 1: iEEG Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Software for iEEG Research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| iEEG Acquisition Systems | BrainScope, Neuralynx Cheetah | High-frequency recording (up to 25 kHz) with multi-channel capability |

| Signal Processing Platforms | EEGLAB, MNE-Python, SignalPlant | Preprocessing, filtering, artifact removal, and basic analysis |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Keras | Implementing CNN, RNN, transformer architectures for iEEG |

| Data Annotation Tools | SignalPlant, Custom MATLAB GUIs | Expert manual labeling of epileptiform events and artifacts |

| Public iEEG Datasets | FNUSA Dataset, Mayo Clinic Dataset | Benchmarking and validation of novel algorithms |

| Specialized Analysis Packages | Temporal Autoencoder implementations | Semi-supervised learning with limited labeled data |

Signaling Pathways and Computational Workflows

The computational framework for iEEG analysis transforms raw neural signals into clinically actionable insights through a multi-stage processing pipeline. The pathway begins with raw iEEG acquisition using stereotactic depth electrodes or subdural grids with sampling rates sufficient to capture HFOs (typically ≥2000 Hz) [45]. Signal preprocessing then removes artifacts and normalizes data, followed by feature extraction through deep learning architectures that automatically detect spatiotemporal patterns associated with epileptogenicity [22]. The model outputs are then translated into clinical决策支持 through epileptogenicity indices and EZ probability maps that inform surgical planning [22].

Diagram 2: Deep Learning Architecture

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, several challenges remain in the clinical implementation of deep learning for iEEG analysis. Data scarcity and heterogeneity in iEEG acquisition protocols across centers creates significant obstacles to model generalizability [22]. The "black box" nature of deep learning models raises concerns about interpretability in clinical settings where surgical decisions have profound consequences [22]. There is also a critical need for standardized validation frameworks and prospective clinical trials to establish the efficacy of these approaches in improving surgical outcomes [22] [49].

Future research directions include the development of explainable AI techniques to enhance model interpretability, transfer learning approaches to adapt models across different recording systems and patient populations, and neuromorphic computing implementations for real-time, low-power seizure detection in implantable devices [22] [49]. The integration of multimodal data (combining iEEG with structural/functional MRI and clinical metadata) represents another promising avenue for improving localization accuracy [22]. As these technologies mature, they hold significant potential to transform epilepsy surgery from a subjective art to a data-driven science, ultimately improving outcomes for patients with drug-resistant epilepsy.

Subject-Independent Mental Task Classification for Brain-Computer Interfaces

Subject-independent mental task classification represents a significant paradigm shift in brain-computer interface (BCI) research, addressing the critical challenge of variability in brain signals across different individuals. Traditional BCI systems require extensive calibration for each user, limiting their practical deployment and scalability. Subject-independent classification aims to create generalized models that perform effectively on new users without subject-specific training data, leveraging advanced deep learning architectures and transfer learning strategies to overcome individual neurophysiological differences [50] [51].

The fundamental challenge in subject-independent BCI systems stems from the substantial variability in electroencephalography (EEG) patterns across individuals. These differences arise from factors including skull thickness, brain anatomy, cognitive strategies, and mental states, creating what is known as the "cross-subject domain shift" problem [50]. This variability means that a model trained on one subject's data often performs poorly when applied to another subject, a phenomenon referred to as negative transfer [50]. Recent advancements in deep learning and transfer learning have enabled researchers to develop techniques that learn invariant features across subjects, paving the way for more robust and practical BCI systems.

Within the broader context of deep learning EEG analysis classification research, subject-independent classification represents a crucial step toward real-world BCI applications. By reducing or eliminating the need for individual calibration, these systems can significantly decrease setup time and cognitive fatigue for users while improving the overall usability of BCI technology [50]. This approach is particularly valuable for clinical applications, where patients with severe motor disabilities may struggle with lengthy calibration procedures.

Key Methodological Approaches

Transfer Learning and Domain Adaptation

Transfer learning has emerged as a powerful framework for addressing cross-subject variability in EEG classification. The core principle involves leveraging knowledge gained from multiple source subjects to improve performance on target subjects with limited or no training data. Two primary approaches have dominated this space: task adaptation, where a model is fine-tuned for specific tasks, and domain adaptation, where input data is adjusted to create more consistent representations across users [50].

Euclidean Alignment (EA) has gained significant traction as an effective domain adaptation technique due to its computational efficiency and compatibility with deep learning models. EA operates by reducing differences between the data distributions of different subjects through covariance-based transformations. Specifically, it adjusts the mean and covariance of each subject's EEG data to resemble a standard form, effectively aligning the statistical properties of EEG signals across individuals [50]. This alignment process enables deep learning models to learn more generalized features that transfer better to new subjects.

Experimental evaluations demonstrate that EA substantially improves subject-independent classification performance. When applied to shared models trained on data from multiple subjects, EA improved decoding accuracy for target subjects by 4.33% while reducing model convergence time by over 70% [50]. These improvements highlight the practical value of EA in developing efficient and accurate subject-independent BCI systems.

Advanced Deep Learning Architectures

Recent research has explored sophisticated deep learning architectures specifically designed for subject-independent EEG classification. The Composite Improved Attention Convolutional Network (CIACNet) represents one such advanced architecture that combines multiple complementary components for robust feature extraction [52]. CIACNet integrates a dual-branch convolutional neural network (CNN) to extract rich temporal features, an improved convolutional block attention module (CBAM) to enhance feature selection, a temporal convolutional network (TCN) to capture advanced temporal dependencies, and multi-level feature concatenation for comprehensive feature representation [52].

The attention mechanism within CIACNet plays a crucial role in subject-independent classification by dynamically weighting the importance of different EEG features. This allows the model to focus on neurophysiologically relevant patterns that generalize across subjects while ignoring subject-specific artifacts or noise [52]. Empirical results demonstrate CIACNet's strong performance on standard benchmark datasets, achieving accuracies of 85.15% on the BCI IV-2a dataset and 90.05% on the BCI IV-2b dataset [52].