Deep Brain Stimulation Parameter Optimization: From Foundational Principles to AI-Driven Future

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of deep brain stimulation (DBS) parameter settings, addressing the critical needs of researchers and clinical scientists.

Deep Brain Stimulation Parameter Optimization: From Foundational Principles to AI-Driven Future

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of deep brain stimulation (DBS) parameter settings, addressing the critical needs of researchers and clinical scientists. It explores the foundational principles of neural circuit engagement and ethical considerations in trial design. The content details cutting-edge methodological advances, including geometry-based algorithms, MRI-guided programming, and adaptive closed-loop systems. It further examines troubleshooting paradigms for suboptimal outcomes and comparative validation of novel approaches against standard care. By synthesizing evidence across neurological and psychiatric indications, this review aims to bridge computational innovation with clinically viable optimization strategies for personalized neuromodulation.

The Fundamentals of DBS: Targeting Circuit Dysfunction and Establishing Ethical Frameworks

The efficacy of neuromodulation therapies, such as deep brain stimulation (DBS), hinges on a multi-scale understanding of neural mechanisms. These mechanisms range from the modulation of single ion channels to the emergent dynamics of entire neural networks [1] [2]. In the context of DBS, precise parameter settings are critical for maximizing therapeutic benefit while minimizing side-effects. However, the optimization of these parameters remains a significant clinical challenge due to the vast possible combination of settings and the dynamic, patient-specific nature of neural tissue [3]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols, framed within DBS research, to guide the investigation of these neural mechanisms. It is intended for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to bridge foundational neurobiology with clinical application, and includes structured data, methodologies, and visualization tools to support this work.

Core Neurobiological Mechanisms

Ion Channel Modulation in the Axon

The axon is a critical locus for neuromodulation, where G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) activate intracellular signaling cascades that directly modify ion channel properties [1]. This modulation profoundly impacts action potential (AP) initiation, propagation, and, ultimately, neurotransmitter release.

Key Modulatory Mechanisms include:

- Dopaminergic Modulation: Dopamine, acting through D3 receptors, hyperpolarizes the voltage-dependent steady-state inactivation of CaV3.2 channels in the axon initial segment (AIS). This reduces the availability of these calcium channels, which typically contribute to subthreshold depolarization and high-frequency AP bursts, thereby decreasing neuronal burstiness [1].

- Cholinergic Modulation: In contrast, acetylcholine hyperpolarizes the voltage-dependent activation of AIS-localized CaV3.2 channels. This increases basal calcium levels at the AIS, which in turn reduces calcium-sensitive KV7 potassium current. The net effect is a lower threshold for AP initiation [1].

- Serotonergic Modulation: Serotonin, via 5-HT1A receptors, can suppress HCN channels in the AIS through Gi/o-mediated inhibition of cyclic AMP. This leads to a hyperpolarization of the resting membrane potential and the AP threshold. Serotonin can also inhibit sodium channel current density, preferentially affecting NaV1.2 subtypes in the cortex [1].

The following table summarizes the effects of different neuromodulators on axonal ion channels:

Table 1: Neuromodulator Effects on Axonal Ion Channels

| Neuromodulator | Receptor | Primary Ion Channel Target | Biophysical Effect | Net Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | D3 | CaV3.2 | Hyperpolarizes steady-state inactivation | Reduced burst firing [1] |

| Acetylcholine | Not Specified | CaV3.2 | Hyperpolarizes voltage-dependent activation | Lowered AP initiation threshold [1] |

| Serotonin | 5-HT1A | HCN | Suppresses channel function via ↓cAMP | Hyperpolarized RMP and AP threshold [1] |

| Serotonin | 5-HT1A | NaV1.2 | Reduces sodium current density | Reduced excitability [1] |

Network-Level Dynamics: Attractor Landscapes in Decision and Memory

Cognitive functions like decision-making (DM) and working memory (WM) are supported by the dynamics of attractor networks in areas such as the prefrontal and parietal cortices [4]. In this framework, stable patterns of neural activity (attractors) represent distinct decisions or memory items.

Circuit Architecture and Cognitive Function:

- Selective Inhibition: Recent evidence indicates that inhibitory neurons form functional subnetworks that are selective to specific stimuli, similar to excitatory populations. Circuits with this selective inhibition architecture exhibit stronger resting states, which improves the accuracy of DM by reducing spontaneous transitions between attractor states [4].

- Robustness-Flexibility Trade-off: While selective inhibition improves DM accuracy, it can result in weaker decision states, making WM representations more vulnerable to distracting stimuli. This highlights a fundamental trade-off between the robustness of WM and the flexibility/accuracy of DM [4].

- Temporal Gating via Non-Selective Input: Presenting a ramping, non-selective input during the delay period of a DM task can act as a temporal gating mechanism. This input stabilizes the active WM representation against distractors with a minimal increase in total thermodynamic cost compared to a constant non-selective input [4].

The diagram below illustrates the core concepts of the attractor network model for decision-making and working memory.

Network Architecture for Decision-Making

Application Notes: Quantifying Neuromodulation for DBS

Quantitative Assessment of DBS Parameter Efficacy

Optimizing DBS parameters is a central challenge in neuromodulation. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research on stimulation parameters for different targets, illustrating the effect of parameter selection on therapeutic outcomes.

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes of Deep Brain Stimulation Parameters

| DBS Target | Stimulation Parameters | Key Efficacy Metric | Reported Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior Thalamic Nuclei (ANT) for Epilepsy | iHFS: 145 Hz, 90 μs, 1 min on/5 min off (SANTE protocol) | Median Seizure Frequency Reduction | 33% reduction (IQR = 0-65) [5] | |

| Anterior Thalamic Nuclei (ANT) for Epilepsy | cLFS: 7 Hz, 200 μs, continuous | Median Seizure Frequency Reduction | 73% reduction (IQR = 30-79) [5] | |

| Subthalamic Nucleus (STN) for Parkinson's | Automated programming based on electrode location | Change in Clinical Outcome | Non-inferior to expert programming in blinded trial [3] | |

| General DBS Targets | Local Field Potential (LFP) beta power (13-35 Hz) | Correlation with Motor Impairment | Used as biomarker for adaptive and automated DBS [3] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

This section lists key tools and reagents for investigating neural mechanisms and developing neuromodulation therapies.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Neuromodulation Studies

| Item/Category | Function/Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sharp Microelectrodes | Intracellular recording of membrane potential and AP dynamics in single neurons. | 3 M KCl-filled electrodes for recording spontaneous tonic spiking [6]. |

| CW-NIR Laser System | Non-invasive optical stimulation to modulate neuronal excitability and study thermal effects on ion channels. | Diode laser, 830 nm wavelength, 90 mW output power; used for sustained and activity-dependent stimulation [6]. |

| Programmable DBS Systems | Precisely control electrical stimulation parameters in clinical or pre-clinical research. | Systems with independent current control for high-resolution DBS [3]. |

| Local Field Potential (LFP) Recording | Capture aggregate neural population activity to identify biomarkers for disease state and stimulation efficacy. | Beta band (13-35 Hz) power in subthalamic nucleus correlates with Parkinsonian motor symptoms [3]. |

| Computational Modeling Software | Simulate neural dynamics from ion channels to network attractors; test algorithms for automated DBS. | Used for mean-field models of attractor networks and biophysical models of neuronal polarization [4] [2]. |

| Wearable Kinematic Sensors | Objective, continuous measurement of motor symptoms (tremor, bradykinesia) for outcome assessment. | Accelerometer-based wristwatches; used to automate DBS programming [3]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Intracellular Recording During Optical Neuromodulation

This protocol details the methodology for quantifying the effects of continuous-wave near-infrared (CW-NIR) laser illumination on single neuron dynamics [6].

1. Preparation and Setup

- Animal Model: Use the isolated central nervous system of Lymnaea stagnalis. Select the Right Parietal Ganglion (RPG) for its large, spontaneously active neurons.

- Solution: Prepare saline solution (in mM: 51.3 NaCl, 1.7 KCl, 1.5 MgCl₂·6H₂O, 4.1 CaCl₂·2H₂O, 5 HEPES, pH 7.8 with NaOH).

- Dissection: Isolate the neural system and remove the sheath above the ganglia using protease (Sigma type XIV) to facilitate electrode access.

2. Instrumentation and Calibration

- Recording: Use sharp electrodes filled with 3 M KCl. Acquire membrane potential recordings at 10 kHz using a DC amplifier and an A/D board.

- Temperature Calibration: Employ the open-pipette method. Calibrate the relationship between electrode resistance and temperature in the solution using a thermistor to estimate laser-induced temperature changes.

3. Stimulation Paradigms

- Sustained Stimulation: Deliver CW-NIR laser illumination (830 nm wavelength, ~90 mW, power density ~146 W/cm²) for periods exceeding 1 minute.

- Activity-Dependent (Closed-Loop) Stimulation: Use open-source RTXI software to trigger transient laser illumination (e.g., 500 ms duration) based on real-time detection of specific neural events, such as action potentials.

4. Data Analysis

- Spike Waveform Characterization: For each detected action potential, calculate the following metrics:

- Duration (at half-width)

- Amplitude (min to max voltage)

- Depolarization slope (1 ms around half-width point pre-peak)

- Repolarization slope (1 ms around half-width point post-peak)

- Statistical Comparison: Compare the distributions of these metrics during pre-stimulation, stimulation, and post-stimulation periods to quantify CW-NIR effects.

The workflow for this protocol is visualized below.

Optical Neuromodulation Experimental Workflow

Protocol: Two-Choice Operant Assay for Social vs. Nonsocial Reward

This behavioral protocol is used to investigate the neural circuits underlying reward-seeking behavior and can be adapted to study the effects of neuromodulation on decision-making [7].

1. Apparatus Assembly

- Chamber: Construct an acrylic chamber with two reward access zones on opposite sides.

- Choice Ports: Drill two 1-inch circular holes on one wall for nose-poke ports. Install infrared sensors to detect entries.

- Reward Ports:

- Sucrose Reward: Drill a 1-inch circle on an adjacent wall for a sucrose delivery port.

- Social Reward: On the opposite wall, cut a 2" x 2" square for social target access. Cover this with an automated gate (e.g., an aluminum sheet attached to a motorized camera slider or linear actuator controlled by an Arduino Uno).

2. Behavioral Training

- Habituation: Acclimate mice to the operant chamber.

- Shaping: Train mice to perform a nosepoke response to earn rewards.

- Sucrose Reward: Deliver a liquid sucrose solution.

- Social Reward: Open the social gate to provide temporary access to a conspecific mouse upon a correct nosepoke.

- Two-Choice Task: Present both reward options concurrently. The mouse's choice (nosepoke in the corresponding port) determines the reward delivered.

3. Combining with Neural Manipulations

- Neural Recording: Implant electrodes or optical fibers to record/manipulate activity in target brain regions (e.g., Medial Amygdala, Ventral Tegmental Area) during the task.

- Data Correlation: Analyze neural activity patterns during the choice phase, reward anticipation, and reward consumption for social versus nonsocial rewards.

Visualization of Neuromodulatory Pathways

The following diagram summarizes the GPCR-mediated signaling pathways that modulate ion channels in the axon initial segment, as described in Section 2.1.

GPCR Modulation of Axonal Ion Channels

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) has evolved from an empirical treatment to a network-level therapy grounded in circuit-based targeting. This approach recognizes that neurological and neuropsychiatric diseases arise from distributed network dysfunction rather than isolated pathology in single brain regions [8]. The fundamental principle of circuit-based targeting is that specific symptoms and disease manifestations map onto distinct, though often overlapping, neural circuits. By identifying and modulating critical nodes within these pathological networks, DBS can restore more normal neural dynamics and alleviate symptoms [8] [9]. This paradigm shift has been driven by growing understanding of brain network organization and the recognition that traditional single-target approaches may be insufficient for diseases with distributed circuitry.

The transition to circuit-based frameworks represents a significant advancement in neuromodulation, enabling more precise targeting of the neural substrates underlying specific pathological states. This approach requires integration of neuroimaging, electrophysiology, and clinical data to identify optimal stimulation targets for each patient's symptom profile. The following sections detail the specific circuit-pathology relationships, quantitative evidence, methodological protocols, and technical tools that form the foundation of modern circuit-based DBS.

Disease-Specific Circuit Pathologies and Target Relationships

Table 1: Circuit-Based Targets for Specific Pathologies and Symptoms

| Disease | Primary Symptoms/Circuits | Established DBS Targets | Emerging/Multi-Target Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parkinson's Disease | Akinesia, rigidity, tremor [9] | STN, GPi [9] | Dual-target (STN+GPi) for gait [8] |

| Dystonia | Abnormal postures, sustained muscle contractions [9] | GPi [9] | STN for cervical dystonia [9] |

| Essential Tremor | Action tremor [9] | Vim [9] | Posterior subthalamic area [9] |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | Compulsions, anxiety [8] | ALIC, VC/VS [10] [11] | BNST, STN, individualized targets [11] |

| Treatment-Resistant Depression | Anhedonia, depressed mood [8] [11] | SCC, SLF-MFB [11] | Individualized circuits based on biomarkers [11] [12] |

| Chronic Pain | Nociceptive, neuropathic pain [8] [12] | VC/VS, SCC [8] | Personalized cortico-striatal-thalamocortical targets [12] |

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes for Circuit-Based DBS Approaches

| Disease | Intervention | Clinical Outcome Measure | Improvement | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parkinson's Disease | STN-DBS | UPDRS-III motor score | 50.5% reduction [9] | Meta-analysis |

| Parkinson's Disease | GPi-DBS | UPDRS-III motor score | 29.8% reduction [9] | Meta-analysis |

| Dystonia | GPi-DBS | Burke-Fahn-Marsden Motor Score | 60.6% improvement [9] | Meta-analysis |

| Essential Tremor | Unilateral Vim-DBS | Tremor rating scales | 53-63% reduction [9] | Systematic review |

| Essential Tremor | Bilateral Vim-DBS | Tremor rating scales | 66-78% reduction [9] | Systematic review |

| Essential Tremor | PSA-DBS | Tremor rating scales | 64-89% reduction [9] | Clinical trial |

| OCD | ALIC-DBS with optimized targeting | Yale-Brown OCD Scale | Correlation with evoked potential amplitude [13] | Clinical study |

Experimental Protocols for Circuit-Based Target Engagement

Protocol: Intraoperative Evoked Potential Mapping for Target Optimization

Application: Refining DBS lead placement in the anterior limb of the internal capsule (ALIC) for obsessive-compulsive disorder [13].

Materials and Equipment:

- DBS macroelectrode (e.g., Medtronic 3387/3389, Abbott 6172)

- Electroencephalography system with forehead electrodes

- Neurophysiological recording system

- Stereotactic surgical frame

- Probabilistic tractography data from preoperative diffusion MRI

Procedure:

- After initial DBS lead placement using standard stereotactic coordinates, deliver monopolar stimulation through each electrode contact at 2Hz with predefined current amplitude.

- Record EEG evoked potentials (EPs) from forehead electrodes with sampling rate ≥1000Hz.

- Average EEG responses across 50-100 stimulation pulses to improve signal-to-noise ratio.

- Analyze EP waveforms for consistent oscillatory peaks at ~35ms, ~75ms, and ~120ms latencies.

- Calculate EP amplitude for each stimulation contact and correlate with tractography-defined target engagement.

- Verify that contacts producing highest EP amplitudes align with maximal white matter connectivity to ventromedial prefrontal cortex/orbitofrontal cortex.

- Finalize lead position to optimize EP characteristics before securing the electrode.

Validation: Treatment nonresponders exhibit less consistent EP waveforms across contacts, supporting the predictive validity of this biomarker [13].

Protocol: Personalized Biomarker Identification for Closed-Loop DBS

Application: Developing patient-specific biomarkers for adaptive DBS in chronic pain and neuropsychiatric disorders [12].

Materials and Equipment:

- Implantable DBS system with sensing capability (e.g., Medtronic Percept, Summit RC+S)

- Ambulatory symptom logging device (smartphone app or dedicated device)

- Signal processing software (MATLAB, Python with MNE, FieldTrip)

- Machine learning frameworks (scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch)

Procedure:

- Inpatient Brain Mapping Phase: Conduct intensive monitoring over 5-10 days with simultaneous intracranial EEG recording and patient-reported symptom metrics.

- Feature Extraction: Calculate spectral power features (beta, gamma, theta bands) from local field potentials across multiple brain regions.

- Biomarker Discovery: Apply machine learning algorithms (e.g., support vector machines, random forests) to identify neural features that correlate with symptom severity states.

- Model Validation: Use cross-validation to test generalizability of biomarker-symptom relationships across different time periods and conditions.

- Algorithm Development: Program closed-loop DBS system to respond to identified biomarker thresholds with appropriate stimulation parameter adjustments.

- Ambulatory Validation: Test biomarker performance in home environment with continuous neural recording and ecological momentary assessments.

- Iterative Refinement: Adjust biomarker detection parameters based on real-world performance and side effect profiles.

Implementation: For chronic pain, this approach has successfully identified personalized biomarkers in cortico-striatal-thalamocortical pathways that predict pain states and enable effective closed-loop stimulation [12].

Protocol: Geometry-Based DBS Programming Optimization

Application: Data-efficient optimization of DBS parameters for Parkinson's disease using anatomical imaging [14].

Materials and Equipment:

- Preoperative and postoperative MRI scans (T1-weighted, T2-weighted)

- Lead reconstruction software (Lead-DBS)

- Electric field simulation platform (OSS-DBS)

- Clinical evaluation records of initial stimulation testing

Procedure:

- Image Processing: Coregister preoperative and postoperative MRI scans using SPM or ANTs algorithms in Lead-DBS toolbox.

- Electrode Reconstruction: Manually reconstruct DBS electrode trajectory and contact positions in normalized space.

- Target Definition: Identify motor subregion of STN using DISTAL atlas or manual segmentation.

- Contact Selection: Calculate geometry score for each contact based on:

- Euclidean distance to motor STN centroid

- Rotation angle between contact and centroid relative to electrode axis

- Rank and combine these metrics to identify optimal contacts

- Current Selection: Simulate Volume of Tissue Activated (VTA) for candidate contacts using OSS-DBS with varying current amplitudes.

- Optimization: Select stimulation parameters that maximize VTA overlap with target structure while minimizing leakage to adjacent regions.

- Clinical Integration: Optionally incorporate existing clinical review data to fine-tune selection and avoid contacts associated with side effects.

Validation: This approach demonstrates significantly better target coverage (p < 5e-13) and reduced electric field leakage (p < 2e-10) compared to expert manual programming [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Circuit-Based DBS Investigations

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| DBS Platforms with Sensing | Medtronic Percept PC, Abbott Infinity, Summit RC+S [15] [12] | Chronic neural recording & adaptive stimulation | Simultaneous stimulation and local field potential recording |

| Computational Modeling | Lead-DBS, OSS-DBS, StimVision [14] | Electrode reconstruction & VTA modeling | Predicting stimulation field spread and target engagement |

| Neuroimaging | Diffusion MRI tractography, fMRI, 3T/1.5T MRI [13] [14] | Target identification & connectivity analysis | Visualizing structural and functional connectivity of targets |

| Electrophysiology Analysis | Local field potential biomarkers, beta power, evoked potentials [13] [15] | Biomarker discovery & closed-loop control | Providing feedback signals for adaptive stimulation |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Support vector machines, random forests, deep learning [12] | Personalized biomarker identification | Identifying patient-specific neural signatures of symptoms |

| Clinical Assessment Tools | Ecological momentary assessments, UPDRS, Y-BOCS [15] [12] | Symptom monitoring & outcome measurement | Quantifying treatment efficacy in real-world settings |

Emerging Frontiers in Circuit-Based Targeting

Multi-Target Stimulation Approaches

Network-level dysfunctions in neurological and psychiatric disorders often require simultaneous modulation of multiple nodes within affected circuits. Multi-target DBS represents an advanced approach where two or more distinct anatomical structures are stimulated concurrently to address complex symptom profiles [8]. This strategy is particularly relevant for conditions like Parkinson's disease with treatment-resistant symptoms such as gait impairment and speech difficulties, where single-target stimulation may be insufficient. Clinical studies have explored combinations such as GPi+Vim for mixed tremor syndromes, with one study demonstrating 90.6% tremor reduction with dual-target stimulation compared to 21.8% with GPi stimulation alone [8].

The implementation of multi-target approaches requires careful consideration of the risk-benefit ratio, as implanting additional electrodes increases surgical complexity. However, technological advances including directional electrodes, current steering, and multi-independent current control systems are making multi-target strategies more feasible [8]. Future developments in system-on-chip micro-stimulators and closed-loop control systems capable of coordinating stimulation across multiple targets will further enhance the clinical utility of this approach.

Adaptive Closed-Loop DBS Systems

Adaptive DBS represents a paradigm shift from continuous, open-loop stimulation to dynamic, feedback-controlled therapy. These systems automatically adjust stimulation parameters based on detected neural biomarkers, creating a personalized neuromodulation approach that responds to the patient's fluctuating symptoms and brain states [15]. Commercial aDBS systems now available for Parkinson's disease utilize subthalamic beta power as a control signal, with stimulation amplitude dynamically adjusted between predefined upper and lower limits based on real-time biomarker levels [15].

Clinical implementation of aDBS requires a structured programming approach addressing three key challenges: (1) biomarker selection and validation, (2) threshold definition, and (3) stimulation limit optimization [15]. Programming protocols must account for individual variations in biomarker expression and modulation, with specific strategies needed for cases with absent or double beta peaks. Ecological momentary assessment data from recent studies indicates that aDBS can significantly improve overall well-being (p=0.007) and general movement (p=0.058) compared to continuous DBS, with six of eight patients choosing to remain on adaptive therapy long-term [15].

Personalized Target Identification Methodologies

The future of circuit-based targeting lies in fully personalized approaches that identify optimal stimulation sites based on individual brain network architecture and symptom expression. The PRESIDIO trial for depression exemplifies this approach, using individualized targeting based on functional neuroimaging and intracranial EEG mapping to identify patient-specific nodes within the depression network [11]. Similarly, recent work in chronic pain has demonstrated that individualized targets within cortico-striatal-thalamocortical pathways can be identified through intensive brain mapping and subsequently used for effective closed-loop stimulation [12].

These personalized methodologies typically involve extended inpatient monitoring with simultaneous symptom tracking and neural recording across multiple candidate regions. Machine learning algorithms then identify the neural features and locations that most strongly correlate with symptom expression in each individual. This patient-specific circuit mapping enables precise targeting of stimulation to modulate the pathological networks most relevant to each person's clinical presentation, potentially improving outcomes in heterogeneous disorders where one-size-fits-all approaches have shown limited success.

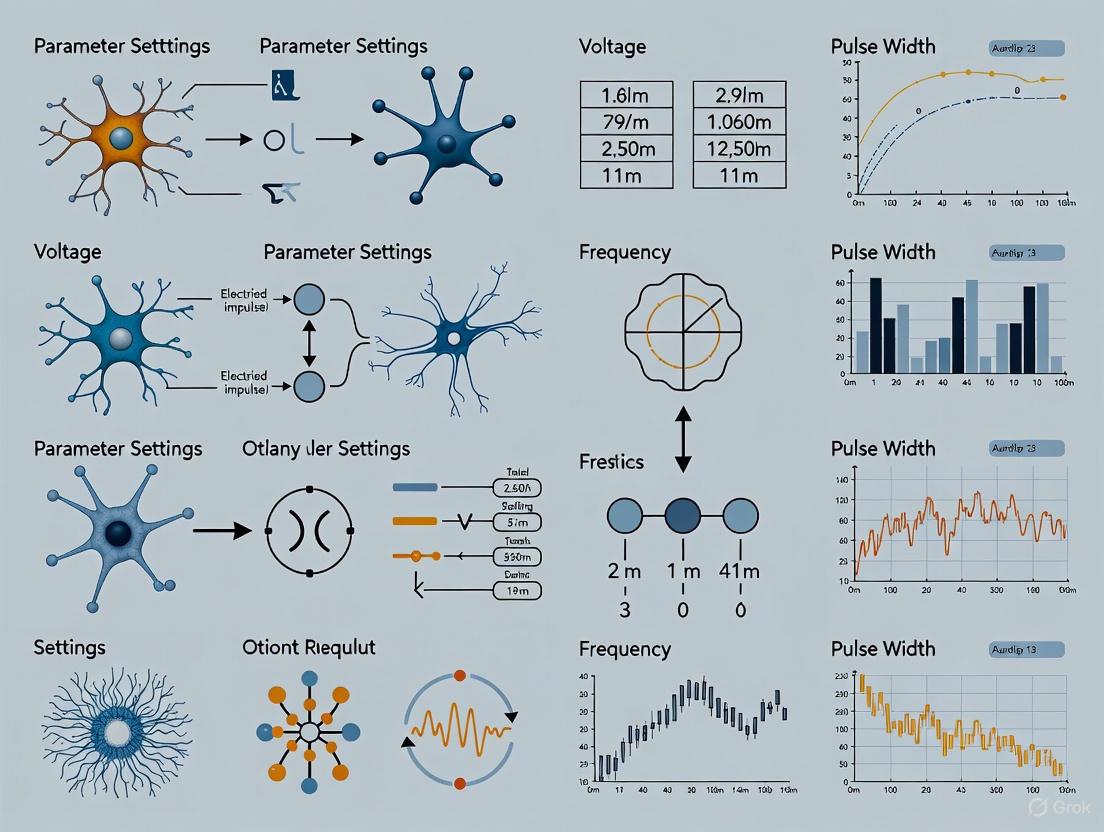

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) represents a cornerstone therapy for managing symptoms of neurological disorders such as Parkinson's disease (PD) and epilepsy. While the surgical implantation of electrodes is critical, the therapeutic efficacy of DBS is predominantly governed by the precise configuration of its core stimulation parameters: frequency, pulse width, amplitude, and spatial configuration. The optimization of these parameters is a complex process that must be tailored to both the anatomical target and the individual patient's clinical presentation. Current research is moving beyond standardized settings to explore a wider parameter space, including non-conventional combinations and adaptive systems that respond to neural biomarkers. This document synthesizes recent clinical evidence and provides detailed protocols to guide researchers in the systematic investigation of DBS parameter settings.

Quantitative Data Synthesis of Stimulation Parameters

Table 1: Clinical Outcomes of Alternative DBS Frequencies Across Disorders

| Disorder & Target | Stimulation Frequency | Pulse Width | Key Clinical Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epilepsy (ANT) | 145 Hz (iHFS) | 90 μs | 33% median seizure reduction [5] [16] | |

| Epilepsy (ANT) | 7 Hz (cLFS) | 200 μs | 73% median seizure reduction [5] [16] | |

| PD (STN) - Gait | 130 Hz (Conventional) | 60 μs | Reference for gait comparison [17] | |

| PD (STN) - Gait | 80 Hz (Low Frequency) | 60 μs | Improved gait speed in cognitive dual-task [17] | |

| PD (STN) - Gait | 130 Hz | 30 μs (Short Pulse Width) | Improved single and double support phases [17] | |

| PD (STN) - Cognition | ~130 Hz | Not Specified | Decreased decision thresholds (less response caution) [18] | |

| PD (STN) - Cognition | 4 Hz | Not Specified | Increased decision thresholds (more response caution) [18] | |

| PD (Dual-Target) | 125 Hz | Not Specified | Best reduction of bradykinesia [19] | |

| PD (Dual-Target) | 50 Hz | Not Specified | Effective at reducing bradykinesia [19] |

Table 2: Amplitude Modulation in Adaptive DBS for Parkinson's Disease

| Programming Aspect | Continuous DBS (cDBS) | Adaptive DBS (aDBS) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude Characteristics | Fixed amplitude (mean 2.04 mA) | Dynamic range (mean lower limit: 1.71 mA; mean upper limit: 2.28 mA) [15] | |

| Clinical Outcome (Group Level) | Baseline | Improved overall well-being (p=0.007); trend for enhanced general movement (p=0.058) [15] | |

| Patient Preference | N/A | 6 out of 8 patients chose to remain on aDBS long-term [15] |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Investigation

Protocol: Randomized Crossover Trial for ANT-DBS in Epilepsy

This protocol outlines a methodology for comparing radically different parameter sets for anterior thalamic nucleus (ANT) deep brain stimulation in drug-resistant epilepsy [5] [16].

- Objective: To prospectively compare the efficacy and safety of continuous low-frequency stimulation (cLFS) against intermittent high-frequency stimulation (iHFS) for ANT-DBS.

- Patient Population: Individuals with focal drug-resistant epilepsy. A sample size of 16 patients was used in the referenced study.

- Stimulation Arms:

- iHFS Arm: Parameters modeled on the SANTE trial (145 Hz, 90 μs pulse width, cycling 1 minute on/5 minutes off).

- cLFS Arm: Alternative parameters (7 Hz, 200 μs pulse width, continuous stimulation).

- Study Design:

- Randomization: Patients are randomly assigned to one of the two stimulation parameter sets.

- Initial Phase: Patients remain on the first assigned settings for a 3-month period.

- Crossover: Unless the patient is seizure-free, they are switched to the alternative parameter set for a second 3-month period.

- Final Assessment: At the end of the second 3-month period, trial completion is marked. Patients then choose to remain on their current settings or revert to the previous one.

- Primary Outcome Measure: Median percentage reduction in seizure frequency from baseline.

- Key Statistical Considerations: Use non-parametric tests like the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired comparisons of seizure frequency reduction. A p-value of <0.05 is typically considered statistically significant.

Protocol: At-Home Assessment of Adaptive DBS in Parkinson's Disease

This protocol describes a framework for evaluating adaptive DBS (aDBS) using ecological momentary assessments (EMA) in a home-setting [15].

- Objective: To compare the effects of chronic aDBS versus conventional continuous DBS (cDBS) on patient-reported symptoms in Parkinson's disease.

- Patient Population: PD patients implanted with a sensing-capable DBS system. The referenced study included 8 patients.

- Stimulation Modes:

- Continuous DBS (cDBS): Conventional, fixed-amplitude stimulation.

- Adaptive DBS (aDBS): Dual-threshold aDBS system where stimulation amplitude is dynamically adjusted based on real-time subthalamic beta power.

- Programming of aDBS:

- Signal Quality Check: Verify the presence of a robust beta peak in the local field potential (LFP), preferably in the OFF-medication state.

- Threshold Definition: Set the upper and lower LFP thresholds to the 75th and 25th percentiles of daytime beta power, respectively. These thresholds exhibit strong inter-individual variance and require review over several days.

- Amplitude Limit Setting: Define the upper and lower stimulation amplitude limits. The lower limit should be evaluated in the OFF-medication state to prevent undertreatment.

- Optimization Visits: Refine LFP thresholds and amplitude limits based on patient reports and data logs to address under-stimulation, over-stimulation, or maladaptation.

- Outcome Measurement - Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA):

- Patients receive repeated electronic questionnaires on a smartphone or device during their daily lives.

- Questions assess overall well-being, general movement, dyskinesia severity, and tremor on Likert-like scales.

- The study aimed for multiple assessments per day over two-week periods for each stimulation mode.

- Analysis: Compare mean scores for each EMA item between the cDBS and aDBS conditions using linear mixed-effects models to account for repeated measures.

Protocol: LFP-Guided Contact Selection for STN-DBS in Parkinson's Disease

This protocol utilizes local field potentials (LFP) to predict the optimal stimulation contact, potentially streamlining the clinical programming process [20].

- Objective: To validate LFP recordings for predicting the clinically chosen optimal monopolar stimulation contact.

- Patient Population: PD patients with implanted DBS systems capable of chronic LFP recording. The method was validated across 121 STN hemispheres.

- LFP Data Acquisition:

- Record bipolar LFP surveys (e.g., BrainSense Survey) from all possible electrode contact pairs.

- Perform recordings in the OFF-medication state (overnight suspension of dopaminergic drugs) to enhance beta-band visibility.

- Feature Extraction:

- For each bipolar recording channel, calculate the power spectral density.

- Identify the patient-specific beta peak frequency (typically 13-35 Hz).

- Extract features from the beta band. The "Max" feature (maximum beta power relative to the 1/f background) is most feasible for in-clinic use.

- Prediction Algorithm ("Decision Tree" Method):

- Rank Channels: Rank all bipolar recording channels based on the amplitude of the selected beta feature ("Max").

- Selection Tree: The top-ranked bipolar channel indicates that the contact situated between the two recording contacts is a candidate for the optimal stimulation contact.

- Elimination Tree: If the beta feature is flat across channels, the algorithm can also eliminate contacts with low predictive value.

- Validation: The predicted top two contact-levels achieved an accuracy of 86.5% compared to the clinician's choice based on monopolar review.

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for DBS Parameter Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sensing Neurostimulator | Enables recording of local field potentials (LFPs) and adaptive stimulation. | Medtronic Percept PC, Boston Scientific Vercise Genus [15] [20]. |

| Local Field Potential (LFP) Biomarkers | Serves as a physiological feedback signal for symptom state and target engagement. | Subthalamic beta power (13-35 Hz) for Parkinson's bradykinesia/rigidity [15] [20]. |

| Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) | Captures real-world, patient-reported outcomes in daily life. | Smartphone-based questionnaires on well-being, movement, and side-effects [15]. |

| Computational Decision Models | Quantifies latent cognitive processes affected by stimulation parameters. | Diffusion decision modeling to analyze decision thresholds in cognitive tasks [18]. |

| LFP-Guided Prediction Algorithms | Automates and objectifies the initial selection of optimal stimulation contacts. | "Decision tree" method using beta power features to rank contacts [20]. |

| Biophysical Models | Tests hypotheses and predicts outcomes of novel stimulation paradigms in silico. | Used to explore low-frequency dual-target DBS with intrahemispheric pulse delays [19]. |

Within deep brain stimulation (DBS) research, the optimization of stimulation parameters represents a rapidly advancing frontier. This progress, however, occurs within a complex ethical framework governing clinical trials, particularly concerning two pillars: the equitable selection of patient participants and the scientifically necessary yet ethically challenging use of sham-controlled procedures. These considerations are not mere regulatory hurdles but foundational to conducting research that is both scientifically valid and morally defensible. This application note examines these intertwined ethical dimensions, providing structured data and protocols to guide researchers in navigating this critical aspect of DBS parameter settings research.

Ethical Framework for Sham-Controlled Trials

Justifications and Controversies of Sham Procedures

Sham-controlled trials are a subject of intense ethical debate, characterized by a balance of compelling justifications and significant concerns. The core ethical arguments are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Ethical Arguments For and Against Sham Procedures in Clinical Trials

| Supporting Arguments | Opposing Arguments |

|---|---|

| ↑ Scientific Validity: Enables blinding to prevent performance and ascertainment bias; isolates specific treatment effects from placebo effects. [21] [22] | Risk-Harm Balance: Exposes participants to risks without prospect of direct therapeutic benefit, violating the principle of non-maleficence. [23] [21] |

| Societal Benefit: Generates reliable knowledge about true efficacy, protecting future patients from ineffective treatments. [21] | Clinical Misconception: Blurs the line between clinical care and research; clinicians may engage in deliberate deception. [23] |

| Informed Consent: Legitimized by prior authorization and full disclosure that a sham procedure may be administered. [23] | Necessity Questioned: A sham control is not always necessary; comparison to an established effective treatment may be sufficient. [21] |

The placebo effect is a particularly critical factor in trials with subjective patient-reported outcomes like pain or quality of life. This effect is a complex psychobiological phenomenon influenced by patient preconceptions, expectations, and the therapeutic context itself. [22] For instance, the act of undergoing an invasive procedure, regardless of its actual therapeutic component, can generate significant symptom relief. Without a sham control, this effect can be misattributed to the intervention under investigation, leading to false positive conclusions and the adoption of ineffective treatments. [22]

Distinction from Clinical Practice

A key ethical concept is that the morality of a sham procedure in a research context is fundamentally different from its use in clinical practice. Performing a fake procedure on a patient in a clinical setting would be considered fraudulent. In contrast, within a clinical trial, it is a methodologically necessary research intervention. [23] This distinction hinges on the prior informed consent of the research subject, which transforms the act from a deceptive fraud into a legitimate, consented element of an experiment. [23] Researcher integrity is maintained by recognizing that their primary role has shifted from clinician to scientist, with a balanced commitment to rigorous science, the advancement of care, and subject protection. [23]

Ethical Patient Selection for DBS Trials

Ethical patient selection requires a multi-faceted approach that balances scientific needs with patient safety and justice.

Table 2: Key Considerations for Ethical Patient Selection in DBS Trials

| Consideration | Ethical Principle | Application in DBS Parameter Trials |

|---|---|---|

| Medical Refractoriness | Beneficence / Non-maleficence | Select patients with symptoms refractory to conventional pharmacological therapy who thus have a potential for net benefit. [24] [9] |

| Realistic Potential for Benefit | Justice | Preference for patients with established DBS indications (e.g., Parkinson's disease, essential tremor) when testing new parameters or programming methods. [3] [15] |

| Ability to Provide Informed Consent | Autonomy | Ensure patients have the cognitive capacity and are free from coercion; assess understanding of risks, including the possibility of sham assignment. [23] [21] |

| Appropriate Disease Stage | Scientific Validity | Selection depends on the research question: advanced stages for refractory symptoms vs. earlier stages for disease-modification studies. [9] |

| Absence of Absolute Contraindications | Non-maleficence | Exclude patients with significant comorbidities, high surgical risk, or contraindications to implanted hardware. [24] |

The following diagram illustrates the key ethical relationships and decision points in designing a DBS trial:

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for a Sham-Controlled DBS Parameter Trial

This protocol outlines a methodology for a double-blind, sham-controlled RCT investigating a novel adaptive DBS algorithm versus standard continuous DBS.

1. Ethics and Regulatory Preparation

- Submit the full protocol, including justification for the sham control and the complete informed consent document, to an independent Research Ethics Committee (REC) or Institutional Review Board (IRB). [23] [21]

- Obtain regulatory agency approval as required by national law.

2. Patient Selection and Screening

- Inclusion Criteria: (a) Diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease; (b) Documented motor fluctuations despite optimized medication; (c) Successful bilateral STN-DBS implantation at least 3 months prior; (d) Age 18-75; (e) Capacity to provide informed consent.

- Exclusion Criteria: (a) Significant cognitive impairment (MMSE <26); (b) Major active psychiatric comorbidity; (c) Contraindications to MRI; (d) Other serious medical illness limiting life expectancy or study participation.

3. Randomization and Blinding

- Use a central web-based randomization system to assign participants to either

Active aDBSorSham cDBSgroup. [22] - The sham intervention involves programming the DBS device to the patient's established effective cDBS parameters. The novel aDBS algorithm is installed on the device but is functionally disabled, with the device interface displaying simulated "adaptive" activity.

- Both the patient and the outcome assessors are blinded to the group assignment. The programming clinician is unblinded but does not participate in outcome assessments.

4. Informed Consent Process

- The consent form must explicitly state: "You will be randomly assigned to one of two groups. One group will receive the new adaptive stimulation, and the other will continue with your standard stimulation. Efforts will be made to make these two treatments indistinguishable to you and the evaluating doctor." [23]

- Clearly detail all foreseeable risks, including those related to the surgical implantation (already past) and those related to the stimulation paradigms and study visits.

- Emphasize the right to withdraw at any time without penalty to their clinical care.

5. Intervention and Follow-up

- The intervention period is 8 weeks.

- Participants have their devices programmed according to their randomization.

- Schedule follow-up assessments at 2, 4, and 8 weeks.

6. Outcome Assessment

- Primary Outcome: Change in blinded video-rated UPDRS-III motor score in the OFF-medication state from baseline to 8 weeks.

- Secondary Outcomes: Patient-reported quality of life (PDQ-39); daily motor symptom diary; device-specific data loggers for energy use.

7. Data Monitoring

- An independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) reviews unblinded interim data for patient safety and trial integrity.

Protocol for Computational DBS Parameter Optimization

This protocol describes a patient-specific, imaging-based method for optimizing DBS settings, which can reduce the burden of empirical programming and serves as a non-invasive research tool. [14] [25]

1. MRI Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Acquire pre-operative T1-weighted and T2-weighted MRI scans.

- Acquire a post-operative CT scan to visualize the implanted electrode.

- Co-register the pre- and post-operative images using rigid body transformation in a toolbox like Lead-DBS. [14] [25]

2. Electrode Localization and Target Identification

- Manually or automatically reconstruct the position of the DBS lead(s) within the native brain space. [25]

- Normalize the patient's brain images to a standard template (e.g., MNI space).

- Identify the target structure (e.g., the motor subregion of the STN) using an integrated atlas (e.g., DISTAL Atlas). [14]

3. Volume of Tissue Activated (VTA) Modeling

- Create a patient-specific computational model of the electric field using software such as OSS-DBS. [14] [25] This model incorporates the electrode location, tissue dielectric properties, and stimulation parameters (contact, amplitude, pulse width).

- Simulate the VTA for different stimulation configurations.

4. Optimization of Stimulation Parameters

- The optimal contact is selected based on a geometry score that ranks contacts by their Euclidean distance to the centroid of the target structure and, for directional leads, their angular orientation. [14]

- The stimulation amplitude is iteratively adjusted in the model until the simulated VTA achieves maximal overlap with the target structure and minimal leakage into adjacent regions associated with side-effects. [14] [25]

5. Clinical Validation

- The model-suggested parameters are applied to the patient's device.

- Clinical efficacy and side-effect thresholds are assessed through standard clinical examination and patient feedback in a supervised clinical setting.

The workflow for this computational protocol is as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for DBS Trials

| Item / Tool | Function in Research | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Lead-DBS Toolbox | Open-source software for pre/post-op image processing, lead localization, and VTA modeling. [14] [25] | Core platform for computational DBS research; enables atlas-based targeting and data aggregation across centers. |

| OSS-DBS | Open-source simulator for calculating the VTA based on patient-specific imaging and stimulation parameters. [14] [25] | Used to predict neural activation and optimize settings in silico before clinical testing. |

| Directional DBS Leads | Electrodes with segmented contacts allowing current steering. | A key technological advance; enables more precise targeting, reducing side-effects and informing parameter optimization algorithms. [3] |

| Local Field Potential (LFP) Sensing | Capability of implanted pulse generators to record neural signals. | Enables biomarker discovery (e.g., beta oscillations in PD) and is the foundation for adaptive DBS. [3] [15] |

| Adaptive DBS (aDBS) Systems | Next-generation devices that adjust stimulation in response to neural feedback. | Used in trials to test closed-loop therapy against conventional open-loop stimulation; requires specialized programming protocols. [15] |

| Wearable Sensors | Accelerometers, gyroscopes, etc., to objectively quantify motor symptoms. | Provide continuous, real-world outcome measures for assessing DBS efficacy, supplementing clinical rating scales. [3] |

Multidisciplinary Team Requirements for Safe DBS Research and Implementation

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) represents a significant advancement in the treatment of neurological and psychiatric disorders, yet its successful implementation hinges on a comprehensive multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach. The complexity of DBS interventions, which integrate advanced neurosurgical techniques with personalized neuromodulation, demands collaboration across diverse specialties to ensure patient safety, optimize clinical outcomes, and maintain ethical integrity throughout the research and clinical care continuum. This framework delineates the core composition, responsibilities, and protocols essential for MDTs engaged in DBS research and implementation, with particular emphasis on the context of investigating DBS parameter settings.

Core Multidisciplinary Team Composition

The effective functioning of a DBS program relies on a well-defined MDT with complementary expertise. The core team should include, but not be limited to, the following members and their primary responsibilities:

Table 1: Core Multidisciplinary Team Members and Responsibilities

| Team Member | Essential Roles and Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Functional Neurosurgeon | Performs stereotactic lead implantation; manages surgical risks and intraoperative complications; collaborates on target selection. |

| Movement Disorder Neurologist / Psychiatrist | Leads patient selection and diagnostic confirmation; manages medical therapy; directs postoperative DBS programming and parameter optimization. |

| Neuropsychologist | Conducts pre- and post-operative cognitive and psychological assessments; evaluates decision-making capacity. |

| DBS Nurse Coordinator | Serves as the central point of contact for patients and families; coordinates care across the MDT; provides patient education. |

| Bioethicist | Guides ethical review of protocols, especially for vulnerable populations; ensures adherence to principles of respect, beneficence, and justice [11]. |

| Social Worker | Assesses psychosocial support systems and caregiver burden; connects patients with community resources [26]. |

| Neuroradiologist | Performs pre-operative structural and functional imaging for targeting; conducts post-operative imaging to verify lead placement. |

This team composition is fundamental to conducting a thorough risk-benefit analysis, establishing appropriate goals, and providing comprehensive patient education [26]. For research involving vulnerable populations, such as those with neuropsychiatric disorders or profound cognitive impairments, the inclusion of a bioethicist and meticulous attention to informed consent processes are particularly critical [11] [27].

Pre-Implementation Phase: Protocols for Patient Selection and Assessment

Patient Selection Criteria

A rigorous, protocol-driven patient selection process is the cornerstone of successful DBS outcomes. The interdisciplinary evaluation aims to identify candidates for whom the potential benefits of surgery significantly outweigh the associated risks [26]. General inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized below.

Table 2: General DBS Candidate Selection Criteria Framework

| Domain | Typical Considerations |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Idiopathic Parkinson's disease, medically refractory epilepsy, essential tremor, dystonia, or investigationally, OCD, MDD, or PTSD [11] [28]. |

| Disease Severity & Chronicity | Advanced disease with significant impairment despite optimal medical therapy. For PD, criteria may include significant motor fluctuations or troublesome dyskinesias [26]. |

| Treatment Refractoriness | Inadequate response or intolerance to multiple standard-of-care treatments (e.g., pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy) [29] [28]. |

| Levodopa Responsiveness (for PD) | Generally, a significant positive response to levodopa predicts better DBS outcomes for certain symptoms, though DBS can be effective for medication-resistant tremor [26]. |

| Psychological & Cognitive Status | Absence of untreated major psychiatric comorbidity or significant cognitive impairment that would impede cooperation or consent. |

| Social Support | Availability of a reliable care partner to assist with post-operative care and follow-up [26]. |

| Realistic Expectations | Patient and family understanding of the procedure's goals, potential benefits, risks, and limitations [26]. |

Comprehensive Pre-operative Assessment Protocol

The pre-operative assessment is a multi-session process involving all MDT members.

- Neurological/Psychiatric Evaluation: A comprehensive review of diagnosis, symptom profile, medication history, and confirmation of treatment refractoriness.

- Levodopa Challenge Test (for PD): Administration of a supra-threshold dose of levodopa after a 12-hour medication-free period. A >30% improvement in the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) motor score is often used as a benchmark, though its predictive value for long-term outcomes is variable [26].

- Neuropsychological Assessment: A detailed battery evaluating executive function, memory, attention, and mood to establish a cognitive baseline and identify contraindications.

- High-Resolution Neuroimaging: Pre-operative MRI (and sometimes CT) for surgical planning and target identification (e.g., STN, GPi, fornix, NBM) [27] [30].

- Psychosocial and Ethical Review: Assessment of social support structures, caregiver burden, and patient capacity for informed consent, particularly crucial in research contexts for disorders like schizophrenia or severe Alzheimer's disease [11] [27] [29].

Figure 1: Pre-operative Patient Assessment Workflow

Implementation Phase: Surgical and Initial Programming Protocols

Surgical Procedure and Lead Verification

The surgical protocol involves stereotactic implantation of DBS leads into the pre-defined target. Key steps include:

- Frame-Based or Frameless Stereotaxy: Using a stereotactic head frame or fiducial markers for coordinate determination.

- Intraoperative Microelectrode Recording (MER): Used in some centers to physiologically confirm the target location by recording characteristic neuronal activity.

- Intraoperative Clinical Testing: Application of temporary stimulation to assess therapeutic benefits and screen for adverse effects (e.g., motor contractions, paresthesia).

- Post-operative Imaging: A post-operative CT or MRI is coregistered with the pre-operative plan to anatomically verify lead placement prior to initiating chronic stimulation [30].

Initial DBS Programming Protocol

DBS programming is a systematic, iterative process to identify optimal stimulation parameters. Programming is typically initiated 2-4 weeks post-surgery to allow the resolution of microlesion effects and tissue edema [30].

Table 3: DBS Programming Parameters and Considerations

| Parameter | Function | Typical Ranges (Disease-Dependent) |

|---|---|---|

| Amplitude | Controls the intensity of stimulation (field size). | Voltage (V) or current (mA); titrated from low to high. |

| Pulse Width | Duration of each electrical pulse. | 60-120 microseconds (μs). |

| Frequency | Rate of pulse delivery. | High-frequency (e.g., 130-180 Hz) for PD; lower frequencies may be used for gait [31]. |

| Electrode Configuration | Selection of active cathode(s) and anode(s). | Monopolar or bipolar review; directional steering with segmented leads. |

A standard initial programming methodology, such as a monopolar review, is employed [30]:

- System Integrity Check: Verify lead impedance to rule out short or open circuits.

- Monopolar Review: Each electrode contact is tested sequentially as the cathode (negative) with the neurostimulator case as the anode (positive).

- Threshold Determination: For each contact, the amplitude is gradually increased to determine:

- Therapeutic Window: The range between the amplitude that first produces a clinical benefit and the amplitude that first elicits a persistent adverse effect.

- Contact Selection: The contact with the widest therapeutic window is typically selected for chronic stimulation.

Post-Implementation Phase: Long-Term Management and Research-Specific Protocols

Long-Term Clinical Management

The MDT's role continues long after surgery. The neurologist/psychiatrist manages stimulation parameters and medications, the neurosurgeon addresses any hardware-related issues, and the neuropsychologist and social worker monitor and support the patient's psychological and social well-being. Long-term follow-up is essential to manage disease progression and adjust therapy accordingly.

Research-Specific Protocols for Parameter Optimization

Research into DBS parameter settings employs advanced protocols to move beyond empiric programming. Key experimental methodologies include:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for DBS Parameter Investigation

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function in DBS Research |

|---|---|

| Bidirectional Neural Implants (e.g., RC+S) | Allows simultaneous delivery of stimulation and chronic recording of local field potentials (LFPs) to identify symptom-linked neural biomarkers [31]. |

| Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) | Provides objective, high-fidelity kinematic data (e.g., stride velocity, arm swing) for quantitative assessment of motor symptoms [31]. |

| Bayesian Optimization Models | Data-driven models that efficiently navigate the vast parameter space to predict personalized optimal DBS settings with limited trials [31]. |

| Standardized Behavioral Tasks | Used to evoke and measure specific symptoms (e.g., fear conditioning/extinction in PTSD) and correlate them with neural activity [28]. |

An example experimental workflow for gait optimization in Parkinson's disease is detailed below, integrating several of these tools [31].

Figure 2: Research Protocol for Gait Optimization

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Gait Optimization [31]:

- Baseline Data Acquisition: Patients equipped with IMUs and a bidirectional implant perform overground walking. Baseline local field potentials (LFPs) from targets like the globus pallidus and motor cortex are recorded synchronously with full-body kinematics.

- Systematic Parameter Variation: DBS parameters (amplitude, frequency, pulse width) are varied within a safe range across multiple sessions. A wide spectrum is tested (e.g., 60 Hz to higher frequencies).

- Multi-Metric Outcome Assessment: A composite Walking Performance Index (WPI) is calculated from key gait metrics: stride velocity, arm swing amplitude, and variability in step length and step time.

- Data Modeling and Analysis: A machine learning model (e.g., Gaussian Process Regressor) is trained on the collected data to predict the WPI based on DBS settings. Neural data is analyzed to identify spectral biomarkers (e.g., reduced pallidal beta power) correlated with improved gait.

- Validation: The model-predicted optimal settings are tested in the patient to confirm improvement in the WPI and the associated normalization of neural biomarkers.

The safe and effective research and implementation of Deep Brain Stimulation is fundamentally dependent on a robust, well-integrated multidisciplinary team. This framework has outlined the essential composition of the MDT, detailed the critical protocols spanning pre-operative assessment to long-term management, and provided examples of advanced research methodologies for parameter optimization. Adherence to this structured, collaborative approach ensures that DBS advances not only as a powerful therapeutic tool but also as a rigorously investigated and ethically conducted field of scientific inquiry.

Advanced Programming Methodologies: From Computational Modeling to Adaptive Systems

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) is an established treatment for advanced Parkinson's disease (PD), but achieving optimal therapy requires meticulous programming of stimulation parameters—a process that remains largely manual, time-consuming, and dependent on clinician expertise [3]. Modern approaches seeking to overcome these limitations have increasingly turned toward data-intensive machine learning methods, which can sometimes function as "black boxes" with limited explainability in clinical settings [14] [25].

Geometry-based optimization represents a promising alternative by leveraging patient-specific anatomical data and electrode location to guide programming. This approach utilizes the spatial relationship between the implanted lead and target structures to recommend optimal stimulation contacts and parameters, offering a more interpretable and clinically integrable solution [14]. This Application Note details the protocols and methodologies for implementing geometry-based DBS optimization, providing researchers with a framework for enhancing programming precision and efficiency.

Core Principles and Quantitative Evidence

Geometry-based optimization operates on the principle that the physical position of DBS electrode contacts relative to the anatomical target structure is a primary determinant of therapeutic efficacy. The method uses preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and postoperative lead localization to calculate a geometry score for each contact, prioritizing those closest to the target centroid and optimally oriented toward it [14] [25].

Key Performance Data

Recent clinical evidence demonstrates the effectiveness of this approach. A retrospective study of 174 implanted electrodes from 87 PD patients yielded the following results compared to expert manual programming [14] [25]:

Table 1: Performance of Geometry-Based Optimization vs. Expert Programming

| Performance Metric | Statistical Significance (p-value) | Effect Size (Hedges' g) |

|---|---|---|

| Target Structure Coverage | p < 5 x 10⁻¹³ | g > 0.94 |

| Electric Field Leakage Minimization | p < 2 x 10⁻¹⁰ | g > 0.46 |

| Predicted Motor Outcome | p = 0.09 - 1.0 | g = 0.05 - 0.08 |

These findings indicate that algorithmically selected contacts can achieve superior anatomical precision and potentially equivalent clinical outcomes to manual selections, without the need for protracted iterative testing [14] [25].

The Impact of Electrode Geometry on Stimulation

Beyond lead placement, the physical design of the electrode itself influences stimulation efficiency. Computational modeling reveals that sharper, smaller electrodes enhance stimulation efficiency, while bipolar configurations with separation distances of less than 1 mm can provide higher efficiency and focality compared to traditional monopolar configurations [32]. Furthermore, designs that increase electrode perimeter, such as serpentine variations, create greater variation in current density, which enhances the activating function—a key determinant of neural excitation—and improves stimulation efficiency [33].

Experimental Protocols

Core Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end pipeline for geometry-based DBS optimization, from data acquisition to parameter suggestion.

Figure 1: Geometry-Based DBS Optimization Workflow. The pipeline integrates imaging data and computational modeling to suggest optimal stimulation parameters. STN: Subthalamic Nucleus; VTA: Volume of Tissue Activated.

Protocol 1: Image Processing and Lead Reconstruction

Objective: To accurately localize the implanted DBS lead and identify the target structure within the patient's native brain space.

Materials:

- Preoperative T1-weighted and T2-weighted MRI scans (3D volumes recommended)

- Postoperative CT or MRI scan for electrode visualization

- Lead-DBS software toolbox (https://www.lead-dbs.org/)

- Standard computational environment (MATLAB or Python)

Methodology:

- Image Co-registration: Co-register pre- and postoperative images using the SPM algorithm within Lead-DBS to account for potential brain shift [14] [25].

- Spatial Normalization: Normalize images into standard space (e.g., MNI ICBM 2009b NLIN asymmetric space) using the ANTs algorithm (Advanced Normalization Tools) with SyN nonlinear transformation [14].

- Brain Shift Correction: Apply subcortical brainshift correction algorithms to improve anatomical accuracy in the region of the implanted lead [14].

- Electrode Reconstruction: Manually reconstruct the DBS electrode trajectory and contact positions. For research purposes, this can be performed using the "Manual Reconstruction" module in Lead-DBS. The final reconstruction should be validated by an expert neurologist [14] [25].

- Target Identification: Segment the target structure, typically the motor subregion of the Subthalamic Nucleus (STN), using appropriate atlas definitions (e.g., DISTAL Atlas) within Lead-DBS [14] [34].

- Native Space Conversion: Convert all reconstructions and segmentations back to the patient's native pre-operative space for all subsequent calculations to preserve individual anatomical specificity [14] [34].

Protocol 2: Geometry-Based Contact Selection

Objective: To computationally identify the electrode contact with the most favorable geometric positioning relative to the target.

Materials:

- Native space lead reconstruction data

- Native space target segmentation (motor STN centroid coordinates)

- Custom Python scripts for geometric calculations

Methodology:

- Centroid Calculation: Compute the center of mass (centroid) of the segmented motor STN.

- Distance Metric: For each electrode contact, calculate the Euclidean distance to the motor STN centroid.

- Angular Metric (for directional contacts): For directional contacts, calculate the rotation angle between the contact's center and the STN centroid, relative to the electrode axis.

- Ranking and Scoring: Independently rank all contacts from lowest to highest for both distance and angle. Sum the ranks for each contact to generate a final geometry score (

s_geometry,C). A lower score indicates a more optimal position [14] [25]. - Contact Selection: Select the contact with the lowest aggregate geometry score as the candidate for stimulation.

Protocol 3: VTA-Based Current Optimization

Objective: To determine the stimulation amplitude that optimally covers the target structure while minimizing leakage to adjacent regions.

Materials:

- OSS-DBS simulation software (https://oss-dbs.github.io/)

- Selected optimal contact from Protocol 2

- Tissue conductivity parameters (default: 0.2 S/m for gray matter)

Methodology:

- VTA Simulation: Use OSS-DBS to simulate the Volume of Tissue Activated (VTA) for the selected contact across a range of stimulation currents (e.g., 0.5 mA to 4.0 mA in 0.5 mA steps) [14].

- Overlap Analysis: For each simulated VTA, calculate the percentage overlap with the target structure (motor STN) and with adjacent non-target regions.

- Current Selection: Identify the stimulation current that achieves one of the following:

- Maximal Target Coverage: The current that yields the highest overlap with the target structure.

- Efficiency Optimization: The lowest current that achieves a predefined target coverage threshold (e.g., >80%), thereby maximizing battery life.

- Side-effect Avoidance: Ensure the selected current does not produce a VTA that significantly overlaps with known side-effect zones (e.g., the corticospinal tract) [34].

Advanced Protocol: Integration of Clinical Review Data

Objective: To refine the geometry-based model by incorporating initial clinical testing observations.

Methodology:

- Clinical Data Collection: During the initial programming session, test predefined contact groups (e.g., 4 groups per hemisphere) at incremental current levels. Record therapeutic efficacy (e.g., rigidity reduction) and side-effect thresholds for each configuration [14].

- Scoring: Generate a clinical review score (

s_clinical,C) based on the recorded therapeutic and side-effect observations for each contact group. - Data Fusion: Combine the geometry score (

s_geometry,C) and the clinical review score (s_clinical,C) into a weighted composite score to determine the final optimal contact [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Software for Geometry-Based DBS Optimization

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Lead-DBS Toolbox | Open-source software for image co-registration, normalization, and DBS electrode reconstruction. Essential for processing MRI/CT data. | https://www.lead-dbs.org/ [14] |

| OSS-DBS | Open-source simulation tool for calculating the Volume of Tissue Activated (VTA). Used for predicting neural activation. | https://oss-dbs.github.io/ [14] |

| Clinical Evaluation Data | Structured records of patient's response to intraoperative or initial clinical test stimulation. Used for model fine-tuning. | e.g., Rigidity, akinesia, tremor scores [14] |

| Pre-op & Post-op MRI | High-resolution anatomical images. Pre-op MRI defines anatomy; post-op MRI/CT verifies lead location. | 3T MRI recommended [14] [25] |

| Normative Brain Atlas | Digital atlas providing standardized definitions of subcortical structures like the STN and its functional subregions. | e.g., DISTAL Atlas, CIT168 [34] |

Validation and Refinement Workflow

After implementing the core optimization protocol, validation is a critical final step. The following diagram outlines the process for correlating model predictions with clinical and electrophysiological outcomes.

Figure 2: Model Validation and Refinement Loop. Predictions are validated against electrophysiological and clinical measures to iteratively improve model accuracy. VTA: Volume of Tissue Activated; DF: Driving Force.

Validation Methodologies:

- Cortical Evoked Potentials (cEPs): Use short-latency cEPs as a direct measure of pathway activation (e.g., hyperdirect pathway or corticospinal tract activation) to validate model predictions. The Driving Force (DF) model in native space has been shown to be the most accurate for quantitatively predicting experimental subcortical pathway activations [34].

- Local Field Potentials (LFPs): Record LFPs from the implanted DBS lead to identify biomarkers of effective stimulation (e.g., reduced beta power) and correlate these with VTA models [31].

- Wearable Sensors: Use inertial measurement units (IMUs) to quantify motor outcomes (e.g., stride length, tremor power) objectively, providing a continuous measure for correlating with simulated VTAs [35] [31].

Geometry-based optimization represents a significant advancement in DBS programming, moving from a purely empirical trial-and-error process to a principled, data-driven approach. By leveraging routinely collected MRI data and established computational tools, this method provides a patient-specific, interpretable, and efficient path to optimal stimulation settings. The protocols outlined herein provide a foundation for researchers to implement, validate, and refine these techniques, ultimately contributing to more standardized, effective, and accessible DBS therapies. Future developments will likely focus on tighter integration with real-time electrophysiological biomarkers and closed-loop adaptive systems, further personalizing treatment for neurological disorders.

MRI and Lead-DBS Integration for Patient-Specific VTA Modeling

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) is an established therapy for movement disorders such as Parkinson's disease (PD) and essential tremor, yet optimizing stimulation parameters for individual patients remains challenging [14]. The integration of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with computational modeling through the Lead-DBS toolbox represents a transformative approach for personalizing DBS therapies. This methodology enables researchers and clinicians to visualize electrode placement and predict the Volume of Tissue Activated (VTA) by electrical stimulation, creating patient-specific models that can enhance therapeutic outcomes while minimizing side effects [14]. The following application notes and protocols detail the implementation of this technology for research applications, framed within a broader thesis on advancing DBS parameter optimization through computational modeling.

Background and Significance

Traditional DBS programming relies on empirical, clinical observations during iterative parameter adjustments, a process that is time-intensive and often requires multiple clinical visits [14]. Patient-specific VTA modeling addresses this limitation by leveraging anatomical data to predict neural activation patterns, potentially streamlining the optimization process. Recent advances have demonstrated that algorithmic approaches to contact selection and current amplitude setting can outperform manual expert selections in covering target structures while minimizing electric field leakage to adjacent regions [14]. Furthermore, the integration of clinical review data with computational models enables fine-tuning of stimulation parameters to avoid adverse effects while maintaining therapeutic efficacy.

Core Methodologies for VTA Computation

VTA Computation Methods

Computational models for predicting DBS effects employ various methodologies to calculate the VTA, each with distinct advantages and limitations [36]. The table below summarizes the primary approaches:

Table 1: Comparison of VTA Computation Methodologies

| Method | Description | Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Axon Model Method | Simulates effects of extracellular potentials on mammalian motor axons; traditional standard [36] | Gold standard validation; fundamental research | Computationally intensive; requires significant technical expertise |

| Activating Function (AF) Methods | Calculates second spatial derivative of extracellular voltage along axons [36] | Rapid VTA estimation; clinical applications | Sensitivity to axon orientation relative to stimulation source |

| Electric Field Norm Method | Uses norm of electric field for VTA estimation [36] | Monopolar stimulation with cylindrical leads; clinical tools like Lead-DBS | Limited validation for complex electrode configurations |

Technical Considerations for VTA Modeling

The computational efficiency of VTA modeling must be balanced against biological accuracy. The axon model method, while considered a standard, is computationally demanding and requires specialized expertise [36]. Alternative approaches based on the activating function provide faster computation while maintaining reasonable accuracy:

- AF-Tan: Calculates activating function at each grid point in the tangential direction [36]

- AF-3D: Computes activating function in the maximally activating direction at each grid point, free from axon orientation bias [36]

- AF-Max: Determines maximum activating function along the entire length of a tangential fiber, accounting for virtual cathode effects [36]

For monopolar stimulation, all methods produce highly similar volumes, while for bipolar configurations, only the AF-Max method reliably reproduces VTAs generated by direct axon modeling [36].

Experimental Protocols

MRI Data Acquisition and Processing Protocol

Table 2: MRI Acquisition Parameters for DBS Modeling

| Parameter | Pre-operative | Post-operative |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Field Strength | 3T | 1.5T |

| Image Type | T1-weighted, T2-weighted | CT or MRI |

| Spatial Resolution | ≤1mm isotropic | ≤1mm isotropic |

| Coregistration | ANTs method with SyN nonlinear transform [14] | SPM method [14] |

| Special Processing | - | Subcortical brainshift correction [14] |

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Pre-operative Imaging: Acquire high-resolution T1-weighted and T2-weighted MRI scans at 3T field strength [14]

- Post-operative Verification: Obtain post-implantation CT or MRI scans to visualize electrode placement

- Data Import: Transfer images in NIfTI format to Lead-DBS toolbox [14]

- Spatial Normalization: Coregister pre-operative and post-operative images using ANTs method with SyN nonlinear transformation and mutual information metric [14]

- Brainshift Correction: Apply specialized algorithms to correct for post-operative anatomical shifts [14]

- Electrode Reconstruction: Manually reconstruct electrode trajectories and contact locations within Lead-DBS interface [14]

- Atlas Co-registration: Normalize patient anatomy to standard stereotactic space (e.g., MNI space) for target identification [14]

VTA Simulation and Optimization Protocol

Materials:

- Processed Lead-DBS reconstruction data

- OSS-DBS software for finite element method (FEM) modeling [14]

- Computational resources for electric field simulations

Procedure:

FEM Model Setup:

- Create individual FEM meshes of DBS lead designs embedded in brain tissue models [36]

- Incorporate tissue conductivity parameters appropriate for gray matter, white matter, and encapsulation layers

Electric Field Calculation:

Contact Selection:

Current Amplitude Optimization:

Diagram Title: MRI-Lead-DBS VTA Modeling Workflow

Integration of Clinical Data for Parameter Refinement

For enhanced personalization, clinical evaluations can be incorporated into the optimization pipeline:

Clinical Testing:

Data Integration:

- Combine clinical scores with geometry-based rankings [14]

- Weight clinical outcomes appropriately in final parameter selection

- Prioritize contacts with optimal therapeutic window (separation between efficacy and side effects)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for MRI-Guided DBS Research

| Resource | Type | Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lead-DBS | Software Toolbox | Electrode reconstruction, atlas co-registration, VTA visualization [14] | www.lead-dbs.org |

| OSS-DBS | Computational Tool | Finite element method modeling, electric field calculation [14] | Butenko et al. 2020 |