Comparative Validation of Automated Perfusion Analysis Software in Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Clinicians

Automated perfusion analysis software has become pivotal for extending treatment windows in acute ischemic stroke, guiding life-saving decisions for endovascular therapy.

Comparative Validation of Automated Perfusion Analysis Software in Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Clinicians

Abstract

Automated perfusion analysis software has become pivotal for extending treatment windows in acute ischemic stroke, guiding life-saving decisions for endovascular therapy. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational principles of CT and MR perfusion imaging. It delves into the methodologies of established and emerging software platforms, examines common technical challenges and optimization strategies, and synthesizes evidence from recent comparative validation studies. By evaluating performance metrics, clinical decision concordance, and limitations across different software, this review aims to inform future development and clinical implementation of these critical neuroimaging tools.

The Evolving Role of Automated Perfusion Imaging in Acute Stroke Assessment

The management of acute ischemic stroke has been revolutionized by the ability of perfusion imaging to identify patients who can benefit from endovascular therapy (EVT) beyond the conventional time window [1] [2]. This paradigm shift, established by landmark trials such as DAWN and DEFUSE-3, relies on automated perfusion analysis software to provide rapid, accurate quantification of ischemic core and penumbral volumes [1]. These software platforms have become indispensable tools for translating imaging findings into clinical decisions, enabling personalized treatment approaches based on individual pathophysiology rather than rigid time metrics [1] [3].

As the clinical adoption of perfusion imaging grows, so does the number of available software platforms, each employing distinct algorithms and methodologies. This expansion has created an imperative for rigorous comparative validation to establish reliability and inform clinical choice [1] [3] [4]. This guide provides an objective comparison of current automated perfusion analysis platforms, synthesizing data from recent validation studies to support evidence-based selection for both clinical and research applications in stroke care.

Comparative Performance Data of Perfusion Software

Magnetic Resonance Perfusion-Weighted Imaging (PWI) Platforms

Table 1: Comparative Performance of MRI-Based Perfusion Software

| Software Platform | Ischemic Core Agreement (CCC/ICC) | Hypoperfused Volume Agreement (CCC/ICC) | EVT Eligibility Concordance (Cohen's κ) | Sample Size (Patients) | Reference Standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JLK PWI | CCC = 0.87 | CCC = 0.88 | DAWN: 0.80-0.90DEFUSE-3: 0.76 | 299 | RAPID |

| RAPID (Reference) | Reference standard | Reference standard | Reference standard | 299 | - |

Data synthesized from Kim et al. (2025) [1] [2]. CCC: Concordance Correlation Coefficient; ICC: Intraclass Correlation Coefficient.

A recent multicenter comparative study validated a newly developed PWI analysis platform (JLK PWI) against the established RAPID software [1] [2]. The investigation demonstrated excellent agreement for both ischemic core volume (CCC=0.87) and hypoperfused volume (CCC=0.88), supporting JLK PWI as a reliable alternative for MRI-based perfusion analysis in acute stroke care [1]. The study further revealed very high clinical concordance for endovascular therapy eligibility based on DAWN trial criteria (κ=0.80-0.90 across subgroups) and substantial agreement using DEFUSE-3 criteria (κ=0.76) [1] [2].

CT Perfusion (CTP) Platforms

Table 2: Comparative Performance of CT Perfusion Software

| Software Platform | Ischemic Core Agreement (ICC) | Penumbra Volume Agreement (ICC) | Final Infarct Volume Prediction (SCC) | Sample Size | Comparison Software |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UGuard | 0.92 | 0.80 | 0.72 (AUC) | 159 | RAPID |

| UKIT | 0.902 | 0.956 (Hypoperfusion) | 0.695 (with ground truth) | 278 | MIStar |

| Viz CTP | rₛ=0.844 (rCBF<30%) | rₛ=0.892 (Tmax>6s) | 0.601 | 242 | RAPID |

| e-Mismatch | rₛ=0.833 (rCBF<30%) | rₛ=0.752 (Tmax>6s) | 0.605 | 242 | RAPID |

| CTP+ | SCC=0.62 | - | - | 81 | RAPID, Sphere, Vitrea |

| Cercare Medical Neurosuite | Specificity: 98.3% | - | - | 58 | syngo.via |

Data synthesized from multiple validation studies [3] [5] [4]. ICC: Intraclass Correlation Coefficient; SCC: Spearman Correlation Coefficient; AUC: Area Under Curve.

Multiple CT perfusion platforms have demonstrated strong correlation with established reference standards. UGuard showed exceptional agreement with RAPID for ischemic core volume (ICC=0.92) and penumbra volume (ICC=0.80) [3]. Similarly, UKIT exhibited strong correlation with MIStar for both ischemic core (ICC=0.902) and hypoperfusion volumes (ICC=0.956) [5]. Viz CTP and e-Mismatch both demonstrated strong correlation with RAPID for key parameters (rCBF<30%: rₛ=0.844 and 0.833, respectively) [6].

Cercare Medical Neurosuite demonstrated exceptional specificity (98.3%) in excluding acute stroke, correctly identifying zero infarct volume in 57 of 58 patients with negative follow-up MRI, suggesting particular utility for reliably ruling out small lacunar infarcts [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Validation Framework

Recent comparative studies share common methodological frameworks to ensure robust validation:

Study Population Specifications: Validation studies typically enroll patients with confirmed acute ischemic stroke who underwent perfusion imaging within 24 hours of symptom onset [1] [3]. For example, the JLK PWI validation included 299 patients from multiple centers with a median NIHSS score of 11 and median time from last known well to PWI of 6.0 hours [1]. Studies typically exclude patients with inadequate image quality, severe motion artifacts, or abnormal arterial input function to maintain analytical integrity [1] [3].

Imaging Acquisition Protocols: Standardized imaging protocols are crucial for valid comparisons. MR perfusion studies typically utilize dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced imaging with gradient-echo echo-planar imaging sequences at either 1.5T or 3.0T field strengths [1]. CT perfusion protocols vary by institution but generally employ multi-detector scanners with contrast injection rates of 5-6 mL/s and scan durations of approximately 50-60 seconds [3] [7]. Tube voltages typically range from 70-80 kVp to optimize contrast resolution while managing radiation exposure [3] [7].

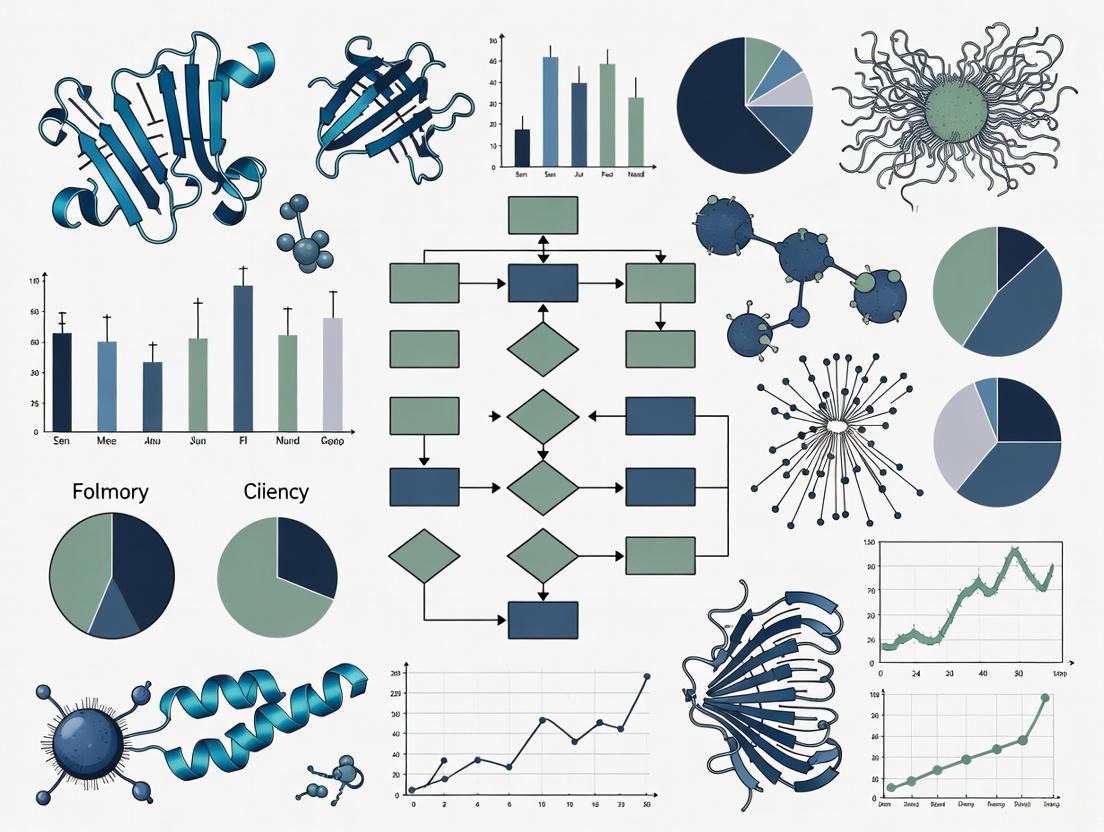

Analysis Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the standard processing pipeline shared across multiple perfusion analysis platforms:

Quantitative Analysis Methods: Validation studies employ standardized statistical approaches including concordance correlation coefficients, intraclass correlation coefficients, Bland-Altman plots, and Pearson or Spearman correlations for volumetric agreements [1] [3]. Clinical decision concordance is typically assessed using Cohen's kappa coefficient based on established trial criteria (DAWN, DEFUSE-3) [1]. Ischemic core estimation in MRI-based platforms often utilizes ADC thresholds (<620×10⁻⁶ mm²/s) or deep learning-based segmentation of DWI b1000 images [1] [2].

Specialized Validation Approaches

Final Infarct Volume Prediction: Several studies assess predictive accuracy by comparing software-estimated ischemic core volumes with final infarct volumes on follow-up imaging, typically 24-hour diffusion-weighted MRI [3] [7]. This approach requires patients with successful complete reperfusion (mTICI 2c-3) to ensure the initial ischemic core evolves into the final infarct without significant penumbral salvage [6] [7].

Specificity Assessment: Some investigations focus particularly on the ability of software to correctly exclude infarction, especially for lacunar strokes [4]. These studies enroll patients with suspected stroke but negative follow-up DWI-MRI, calculating specificity as the proportion of true negatives correctly identified by the software [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Perfusion Software Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Validation | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard Software | Benchmark for comparison | RAPID, MIStar [1] [5] |

| Ground Truth Imaging | Validation of predictive accuracy | 24-hour follow-up DWI [3] [7] |

| Clinical Trial Criteria | Standardized decision thresholds | DAWN, DEFUSE-3, EXTEND [1] [5] |

| Statistical Analysis Packages | Quantitative agreement assessment | R, SPSS, Bland-Altman methods [1] [3] |

| Multi-center Patient Cohorts | Enhanced generalizability | SNUBH (n=216), CNUH (n=102) [1] |

| Multi-vendor Imaging Data | Technical robustness testing | GE, Philips, Siemens scanners [1] |

The validation of perfusion analysis software requires carefully curated resources to ensure comprehensive assessment. Reference standard software such as RAPID provides the benchmark against which new platforms are compared [1] [3]. Ground truth imaging, typically 24-hour follow-up diffusion-weighted MRI, serves as the objective standard for evaluating the accuracy of ischemic core prediction [3] [7]. Validated clinical trial criteria (DAWN, DEFUSE-3) provide standardized thresholds for treatment decisions, enabling consistent assessment of clinical concordance across platforms [1] [5].

Diverse multi-center patient cohorts enhance the generalizability of validation studies, incorporating variations in patient factors, imaging protocols, and clinical workflows [1]. Similarly, multi-vendor imaging data ensures technical robustness across different scanner platforms and acquisition parameters [1]. Comprehensive statistical analysis packages implement specialized methods including concordance correlation coefficients, intraclass correlation coefficients, and Bland-Altman analyses to quantify agreement levels [1] [3].

Automated perfusion analysis software plays an indispensable role in extending treatment windows for acute ischemic stroke, enabling personalized therapeutic decisions based on individual pathophysiology. Current validation evidence demonstrates that multiple platforms, including JLK PWI, UGuard, UKIT, Viz CTP, and e-Mismatch, show strong agreement with established reference standards for both volumetric measurements and clinical decision-making [1] [3] [5].

The choice between platforms should consider specific clinical and research needs, including modality preference (CTP vs. PWI), institutional resources, and particular use cases such as excluding lacunar infarction where specificity becomes paramount [4]. As perfusion imaging continues to evolve, ongoing technical refinements and validation against emerging clinical trial criteria will further enhance the precision and utility of these critical decision-support tools.

In the landscape of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) management, the rapid and accurate assessment of brain perfusion is paramount for guiding treatment decisions, particularly for endovascular therapy (EVT). Computed Tomography Perfusion (CTP) and Perfusion-Weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging (PWI) are two pivotal modalities employed to delineate the ischemic core and the penumbra—the salvageable tissue at risk. The integration of automated perfusion analysis software has further revolutionized this field by providing quantitative, reproducible metrics for EVT eligibility. This guide objectively compares the technical capabilities, advantages, and limitations of CTP and PWI within automated analysis frameworks, drawing on recent comparative validation studies to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Technical Principles and Workflow Integration

Fundamental Technical Characteristics

CTP and PWI, while sharing the common goal of evaluating cerebral hemodynamics, are grounded in distinct physical principles and data acquisition methodologies.

CTP utilizes a series of rapid CT scans to track the first pass of an iodinated contrast bolus through the cerebral vasculature. The resulting time-density curves are processed using deconvolution algorithms, such as delay-insensitive block-circulant singular value decomposition (bSVD), to generate quantitative parameter maps, including Cerebral Blood Flow (CBF), Cerebral Blood Volume (CBV), Mean Transit Time (MTT), and Time-to-maximum (Tmax) [8] [9]. Its integration into the acute stroke workflow is often seamless, as it can be performed immediately after non-contrast CT and CT Angiography (CTA) on the same scanner, minimizing transfer times [10].

PWI, specifically Dynamic Susceptibility Contrast (DSC)-PWI, uses a T2*-weighted MRI sequence to track a gadolinium-based contrast agent. The signal change caused by the magnetic susceptibility of the contrast agent is used to calculate similar perfusion parameters [1]. A key advantage of the MR-based workflow is the routine combination with Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI), which provides a highly accurate delineation of the infarct core based on water diffusion restrictions, offering superior tissue specificity for core estimation [1].

Direct Technical Comparison

The table below summarizes the core technical differences between CTP and PWI as evidenced by recent literature.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of CTP and PWI in Acute Stroke Imaging

| Feature | Computed Tomography Perfusion (CTP) | Perfusion-Weighted MRI (PWI) |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Moderate; can be limited by coverage and noise [10]. | Superior spatial resolution, providing finer detail [1]. |

| Inherent Artifacts | Susceptible to beam-hardening artifacts, particularly in the posterior fossa [1]. | Free from beam-hardening artifacts [1]. |

| Contrast Timing Sensitivity | Sensitive to errors in contrast bolus timing and cardiac output [9]. | Less susceptible to contrast timing errors [1]. |

| Infarct Core Definition | Relies on probabilistic thresholds of CBF/CBV [8]. | Direct, definitive visualization with DWI, often considered the gold standard [1]. |

| Radiation Exposure | Involves ionizing radiation; dose can be significant without low-dose protocols [10]. | No ionizing radiation exposure [1]. |

| Acquisition Speed & Accessibility | Very fast acquisition; widely available in emergency settings [1] [11]. | Longer acquisition time; less readily available in all centers [12]. |

| Quantitative Reliability | Values can vary significantly between software due to differences in deconvolution algorithms [10]. | Provides robust quantification; less variability in core definition when combined with DWI [1]. |

Performance Analysis in Automated Software Platforms

Automated software platforms like RAPID, JLK PWI, and UGuard have standardized the post-processing of perfusion data. Recent studies directly comparing these platforms provide empirical data on the agreement of key volumetric parameters.

Volumetric Agreement in PWI Analysis

A 2025 multicenter, retrospective study by Kim et al. directly compared the novel JLK PWI software against the established RAPID platform in 299 patients. The study evaluated agreement for ischemic core volume, hypoperfused volume (Tmax >6s), and mismatch volume using Concordance Correlation Coefficients (CCC) and Bland-Altman analyses [1] [2].

Table 2: Volumetric Agreement Between JLK PWI and RAPID Software (n=299)

| Perfusion Parameter | Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) | Strength of Agreement | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic Core Volume | 0.87 | Excellent | < 0.001 |

| Hypoperfused Volume | 0.88 | Excellent | < 0.001 |

| Mismatch Volume | Data not fully available in results | - | - |

The study concluded that JLK PWI demonstrated high technical concordance with RAPID, supporting its viability as a reliable alternative for MRI-based perfusion analysis [1].

Volumetric Agreement in CTP Analysis

A parallel 2025 study by Wang et al. validated a novel CTP software, UGuard, against RAPID in a cohort of AIS patients receiving EVT. The agreement for Ischemic Core Volume (ICV) and Penumbra Volume (PV) was assessed using Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) [8].

Table 3: Volumetric Agreement Between UGuard and RAPID CTP Software

| Perfusion Parameter | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) | 95% Confidence Interval | Strength of Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic Core Volume (ICV) | 0.92 | 0.89 – 0.94 | Strong |

| Penumbra Volume (PV) | 0.80 | 0.73 – 0.85 | Good |

The study found that ICV measured by either UGuard or RAPID similarly predicted a favorable functional outcome (modified Rankin Scale 0-2), with UGuard showing higher specificity [8].

Impact on Clinical Decision-Making

The ultimate test of a perfusion modality and its associated software is its reliability in triaging patients for EVT based on clinical trial criteria.

The PWI validation study by Kim et al. evaluated the concordance in EVT eligibility classification between JLK PWI and RAPID using Cohen's kappa (κ) [1] [2].

Table 4: Agreement in Endovascular Therapy Eligibility Classification

| Clinical Trial Criteria | Cohen's Kappa (κ) | Strength of Agreement |

|---|---|---|

| DAWN Criteria | 0.80 - 0.90 (across subgroups) | Very High |

| DEFUSE-3 Criteria | 0.76 | Substantial |

This very high concordance indicates that despite differences in their underlying algorithms for infarct core segmentation (RAPID used ADC < 620×10⁻⁶ mm²/s, while JLK used a deep learning-based algorithm on DWI), the clinical decisions driven by the two platforms are highly consistent [1].

For CTP, a 2024 study by Volný et al. highlighted its clinical value beyond the extended window, demonstrating that a positive CTP result (core/penumbra on RAPID) had a 100% Positive Predictive Value (PPV) and specificity for a confirmed stroke diagnosis, thereby increasing physician confidence in initiating stroke management protocols [11].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

To ensure reproducibility and critical appraisal, the core methodologies from the cited comparative studies are outlined below.

Protocol for Validating PWI Software

Study Design: Multicenter, retrospective cohort [1] [2]. Population: 299 patients with AIS who underwent PWI within 24 hours of symptom onset. Image Acquisition: DSC-PWI was performed on 1.5T or 3.0T scanners (Philips, GE, Siemens) using a gradient-echo echo-planar imaging (GE-EPI) sequence. Software Comparison:

- RAPID: Used ADC < 620×10⁻⁶ mm²/s for DWI core lesion.

- JLK PWI: Used a deep learning-based infarct segmentation on b1000 DWI. Both platforms defined hypoperfused tissue as Tmax >6s. Statistical Analysis: Agreement was assessed with CCC, Bland-Altman plots, and Pearson correlation. Clinical concordance was evaluated with Cohen's kappa for DAWN/DEFUSE-3 criteria [1].

Protocol for Validating CTP Software

Study Design: Retrospective, multi-center cohort [8]. Population: Consecutive AIS patients with large vessel occlusion (LVO) receiving EVT. Image Acquisition: CTP was performed per local protocols on Siemens or GE scanners (e.g., 80 kV, 400 mAs, scan time ~60s). Software Comparison:

- RAPID (v7.0): Used relative CBF (rCBF) <30% for core and Tmax >6s for penumbra.

- UGuard (v1.6): Utilized deep convolutional networks for preprocessing and the same thresholds (rCBF <30%, Tmax >6s). Statistical Analysis: Agreement was assessed with ICC and Bland-Altman analysis. Predictive performance for 90-day functional outcome (mRS) was evaluated using ROC curves and logistic regression [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key software and analytical tools central to conducting and validating perfusion imaging research.

Table 5: Essential Research Tools for Automated Perfusion Analysis

| Research Tool | Primary Function | Application in Validation Studies |

|---|---|---|

| RAPID (iSchemaView) | Fully automated, FDA-cleared software for processing CTP and PWI. | Served as the reference standard for comparison against novel software JLK PWI [1] and UGuard [8]. |

| JLK PWI (JLK Inc.) | Automated PWI analysis platform with a deep learning-based DWI infarct segmentation algorithm. | Was validated against RAPID for volumetric and clinical decision agreement in a multicenter study [1]. |

| UGuard (Qianglianzhichuang Tech.) | Novel CTP post-processing software using machine learning for image preprocessing and perfusion parameter calculation. | Was validated against RAPID for core/penumbra volume estimation and outcome prediction [8]. |

| Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) | Statistical measure assessing both precision and accuracy relative to a line of perfect agreement. | Used to evaluate volumetric agreement between JLK PWI and RAPID [1]. |

| Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) | Statistical measure assessing reliability for quantitative measurements between tools/raters. | Used to evaluate volumetric agreement between UGuard and RAPID CTP measurements [8]. |

| Cohen's Kappa (κ) | Statistic measuring inter-rater agreement for categorical items, correcting for chance. | Used to quantify agreement in EVT eligibility (e.g., DAWN/DEFUSE-3 criteria) between software platforms [1]. |

Workflow and Algorithmic Diagrams

Automated Perfusion Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the generalized pipeline for automated perfusion analysis, common to both CTP and PWI software platforms, highlighting key steps where methodological differences may arise.

CTP vs. PWI Clinical Decision Pathway

This diagram contrasts the typical clinical imaging pathways for CTP and PWI, underscoring their integration into acute stroke workflows and key differentiators.

CTP and PWI, when coupled with their respective automated analysis platforms, are both highly effective in quantifying ischemic tissue and guiding EVT decisions in acute stroke. The choice between them often hinges on specific clinical and research priorities.

- CTP offers superior speed, accessibility, and seamless workflow integration, making it the dominant modality in most emergency settings. Its performance in automated software like RAPID and UGuard shows strong agreement in volumetric assessments and reliable outcome prediction [11] [8].

- PWI provides superior spatial resolution, definitive infarct core delineation with DWI, and the absence of ionizing radiation. The high concordance between platforms like JLK PWI and RAPID demonstrates that MRI-based perfusion analysis is a robust and clinically reliable alternative [1].

For researchers designing clinical trials, especially those focusing on refined biomarkers for medium vessel occlusion or patient stratification beyond simple volumetrics, the enhanced tissue specificity of PWI-DWI may offer significant advantages [1]. Conversely, for studies prioritizing broad recruitment, rapid imaging, and generalizability across diverse hospital settings, CTP-based workflows remain the pragmatic and validated standard.

The advent of automated perfusion imaging analysis has fundamentally transformed the triage and treatment of patients with acute ischemic stroke, enabling the extension of therapeutic windows for endovascular therapy [2] [1]. This software ecosystem is critical for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on precise, reproducible imaging biomarkers to evaluate therapeutic outcomes and advance clinical trials. The landscape comprises established commercial platforms, newly emerging alternatives, and open-source tools for preclinical research, each validated through specific experimental protocols and performance metrics. This guide provides an objective comparison of these platforms, detailing their operational workflows, quantitative performance data, and the essential reagents that constitute the researcher's toolkit in this field.

Commercial Clinical Platforms

Commercial platforms are predominantly validated for clinical decision-making in acute stroke, focusing on accurately identifying the ischemic core and penumbra to guide endovascular thrombectomy (EVT).

Established Leader: RAPID

- Overview: RAPID (iSchemaView Inc.) is the most established platform, with its utility validated in landmark stroke trials such as DAWN and DEFUSE 3 [13]. It is widely deployed in hospitals globally.

- Methodology: It employs a delay-insensitive deconvolution algorithm to calculate perfusion parameters. For MRI-based analysis, the ischemic core is typically defined by an ADC threshold of < 620 × 10⁻⁶ mm²/s, while hypoperfused tissue is defined by Tmax > 6 seconds [2] [1].

- Performance Note: Studies indicate RAPID has high specificity for core infarct identification, though one comparative analysis reported a moderate sensitivity of 40.5% for detecting any acute infarct, which improved to 73.7% for detecting large infarcts (≥70 mL) [13].

Emerging Commercial Platforms

Recent studies have focused on validating new software against the reference standard of RAPID.

Table 1: Comparison of Emerging Commercial Perfusion Software

| Software | Modality | Ischemic Core Metric | Hypoperfusion Metric | Key Performance Data vs. RAPID | EVT Decision Concordance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JLK-CTP [14] | CT | rCBF < 30% | Tmax > 6 s | Ischemic core CCC = 0.958; Hypoperfusion CCC = 0.835 [14] | Not Specified |

| JLK PWI [15] [2] | MRI (PWI-DWI) | Deep learning on b1000 DWI | Tmax > 6 s | Ischemic core CCC = 0.87; Hypoperfusion CCC = 0.88 [15] | DAWN κ = 0.80-0.90; DEFUSE-3 κ = 0.76 [2] |

| UKIT [5] | CT | Proprietary Algorithm | Proprietary Algorithm | Ischemic core ICC = 0.902; Hypoperfusion ICC = 0.956 [5] | EXTEND/DEFUSE-3 κ = 0.73 [5] |

| mRay-VEOcore [16] | CT & MRI | Automated Segmentation | Automated Segmentation | Fully automated analysis in < 3 minutes; Features automated quality control [16] | Visualizes DEFUSE-3 criteria [16] |

| Olea [13] | CT | rCBF < 30% or < 40% | Not Specified | Core volume correlation with DWI: rho = 0.42 (vs. RAPID's 0.64) [13] | Not Specified |

Open-Source and Preclinical Platforms

For research purposes, particularly in preclinical models, open-source tools offer flexibility and customization not always available in closed commercial systems.

Perfusion-NOBEL

- Overview: An open-source DSC-MRI quantification tool written in Python, designed specifically for preclinical research in rodent models of brain diseases such as stroke, glioblastoma, and chronic hypoperfusion [17].

- Methodology: The tool performs a semi-automated analysis requiring manual delineation of masks for the Arterial Input Function (AIF). It generates absolute quantitative maps for CBF, CBV, MTT, Signal Recovery (SR), and Percentage Signal Recovery (PSR) using tracer kinetic models and deconvolution methods [17].

- Validation: The software was validated on a dataset of 30 rat brain scans, and the resulting hemodynamic parameters for healthy, stroke, and glioblastoma models were consistent with values reported in the literature. Bland-Altman analysis showed higher agreement for CBV and MTT than for CBF [17].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

The comparative data presented in this guide are derived from standardized experimental protocols that can be categorized as follows.

Clinical Validation Study Design

Most software validation studies employ a retrospective, multicenter design using existing patient imaging data [15] [5] [14]. A typical protocol includes:

- Population: Patients with acute ischemic stroke who underwent perfusion imaging (CTP or PWI) within 24 hours of symptom onset.

- Inclusion/Exclusion: Patients are excluded for severe motion artifacts, poor contrast bolus, or software processing failures [13] [14].

- Ground Truth: For core infarct validation, a common ground truth is the infarct volume on follow-up diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) performed within 24-48 hours, often segmented using semi-automated or deep-learning methods [13] [14].

Statistical Analysis for Agreement

The key to these studies is quantifying the agreement between different software outputs and against the ground truth.

- Volumetric Agreement: Assessed using Concordance Correlation Coefficients (CCC) or Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC) and Bland-Altman plots for ischemic core, hypoperfused volume, and mismatch volume [15] [5] [14].

- Clinical Decision Agreement: Evaluated using Cohen's kappa (κ) statistic to measure concordance in EVT eligibility based on trial criteria like DAWN and DEFUSE-3 [15] [2] [5].

The experimental workflow for these validation studies is systematic, as shown in the diagram below.

Validation Workflow Diagram. This diagram outlines the standard protocol for comparative validation of perfusion analysis software, from patient selection to statistical comparison against a reference standard and ground truth.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and imaging "reagents" essential for conducting perfusion analysis research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Perfusion Analysis

| Item / Software | Function / Application | Context of Use |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning Segmentation [2] | Automated segmentation of infarct core on DWI (b1000 images). | Used by JLK PWI for precise core estimation, trained on large, manually segmented datasets. |

| Block-Circulant SVD [14] | Deconvolution algorithm for calculating perfusion parameters (CBF, MTT, Tmax). | Core mathematical method in JLK-CTP and other platforms for delay-insensitive analysis. |

| Arterial Input Function (AIF) [17] | Reference function representing the concentration of contrast agent arriving at brain tissue. | Critical for kinetic modeling; can be selected automatically or semi-manually from a major artery. |

| Python-based Processing [17] | Flexible, open-source programming environment for building custom perfusion analysis pipelines. | Foundation for tools like Perfusion-NOBEL, enabling customization and modular development. |

| Dynamic Susceptibility Contrast (DSC) [17] | MRI technique based on T2* signal changes during a gadolinium bolus passage. | The primary MRI perfusion method for quantifying CBF, CBV, and MTT in clinical and preclinical studies. |

Technical Workflows

Understanding the underlying technical workflow is crucial for interpreting results and selecting the appropriate platform for a research goal. The core process of generating perfusion maps from raw imaging data involves a multi-step pipeline, common across many platforms with variations in specific algorithms.

Perfusion Analysis Pipeline. This diagram illustrates the key technical steps involved in processing raw perfusion imaging data to generate quantitative maps and segment tissue status, from preprocessing and deconvolution to final classification.

The ecosystem of automated perfusion analysis software is dynamic, with robust validation studies demonstrating that emerging platforms like JLK-CTP, JLK PWI, and UKIT achieve excellent technical agreement with the established RAPID standard [15] [5] [14]. This concordance translates to substantial agreement in critical clinical decisions like EVT eligibility. For the research and drug development community, this expanding toolkit offers multiple validated options for clinical trial image analysis. Furthermore, the availability of open-source solutions like Perfusion-NOBEL provides essential tools for preclinical research, enabling mechanistic studies and algorithm development in a modular, customizable framework [17]. The choice of platform depends on the specific research context—whether it requires clinically validated endpoints, multi-modality support, or the flexibility to investigate novel perfusion biomarkers in exploratory models.

The management of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) underwent a revolutionary transformation with the publication of the DAWN and DEFUSE-3 clinical trials in 2018. These landmark studies demonstrated the efficacy of endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) in selected patients with large vessel occlusion (LVO) presenting between 6-24 hours after symptom onset, fundamentally shifting treatment paradigms from rigid time-based windows to tissue-status-based approaches [18] [19]. This paradigm shift created an urgent clinical need for rapid, accurate, and automated perfusion imaging analysis software capable of applying the specific volumetric criteria established by these trials. The DAWN trial utilized age- and NIHSS-dependent infarct core volume thresholds, while DEFUSE-3 employed fixed criteria of infarct core <70 mL, mismatch ratio ≥1.8, and penumbra volume ≥15 mL [18] [19]. This foundational framework directly catalyzed the development and validation of automated perfusion analysis platforms that could standardize the identification of EVT-eligible patients in the extended time window, leading to the comparative validation studies that are essential for establishing clinical reliability.

Experimental Protocols in Automated Perfusion Software Validation

Study Designs and Population Characteristics

Recent comparative validation studies have employed rigorous methodological approaches to evaluate automated perfusion software performance. Kim et al. (2025) conducted a retrospective multicenter study involving 299 patients with AIS who underwent perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI) within 24 hours of symptom onset [2] [15] [20]. Similarly, a large CT perfusion (CTP) analysis compared software performance across 327 patients within the same timeframe [14]. These studies employed prospectively collected data from tertiary hospital stroke registries, with comprehensive inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure data quality. Key demographic and clinical characteristics of the studied populations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Baseline Characteristics of Validation Study Populations

| Characteristic | MRI Perfusion Study (n=299) [2] | CT Perfusion Study (n=327) [14] |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (years) | 70.9 | 70.7 ± 13.0 |

| Male Sex | 55.9% | 58.1% |

| Median NIHSS | 11 (IQR 5-17) | Not specified |

| Median Time from LKW to Imaging | 6.0 hours | Within 24 hours |

| Imaging Modality | Magnetic Resonance PWI | Computed Tomography Perfusion |

| Software Compared | JLK PWI vs. RAPID | JLK-CTP vs. RAPID |

Image Acquisition and Analysis Protocols

Standardized imaging protocols were crucial for ensuring valid comparisons between software platforms. In the PWI validation study, imaging was performed on either 3.0T (62.3%) or 1.5T (37.7%) scanners from multiple vendors (GE, Philips, Siemens) equipped with 8-channel head coils [2]. Dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced perfusion imaging utilized gradient-echo echo-planar imaging sequences with specific parameters: TR = 1,000-2,500 ms; TE = 30-70 ms; FOV = 210×210 mm² or 230×230 mm²; and slice thickness of 5 mm with no interslice gap [2]. For CTP studies, scans were performed using a 256-slice CT scanner (Philips Brilliance iCT 256) with parameters: 80 kVp, 150 mAs, beam collimation 6×1.25 mm, rotation time 0.45 s [14]. A total of 50 mL of iodinated contrast agent was administered intravenously at 5 mL/s [14].

The image analysis workflow involved several critical steps that reflect the influence of DAWN/DEFUSE-3 criteria on software functionality. Both RAPID and JLK platforms performed automated preprocessing including motion correction, brain extraction, and arterial input function selection [2] [14]. For infarct core estimation, RAPID employed ADC < 620×10⁻⁶ mm²/s for MRI, while JLK PWI utilized a deep learning-based infarct segmentation algorithm on b1000 DWI images [2]. Hypoperfused regions were delineated using Tmax >6 s threshold in both platforms [2] [14]. All segmentations underwent visual inspection to ensure technical adequacy before analysis, maintaining rigorous quality control standards essential for clinical decision-making [2].

Statistical Methods for Agreement Assessment

Validation studies employed comprehensive statistical approaches to evaluate software agreement. Concordance correlation coefficients (CCC) were used to assess volumetric agreement for ischemic core, hypoperfused volume, and mismatch volume [2] [14]. Bland-Altman plots provided visualization of measurement differences between platforms, while Pearson correlation coefficients quantified linear relationships [2] [15]. For clinical decision concordance, Cohen's kappa coefficient was calculated based on DAWN and DEFUSE-3 eligibility criteria [2] [20]. The magnitude of agreement was classified using established benchmarks: poor (0.0-0.2), fair (0.21-0.40), moderate (0.41-0.60), substantial (0.61-0.80), and excellent (0.81-1.0) [2].

Comparative Performance Data of Automated Perfusion Software

Volumetric Agreement Between Platforms

Quantitative assessment of ischemic core and hypoperfusion volume measurements reveals remarkable concordance between established and emerging software platforms. The validation data demonstrate that newer software solutions achieve excellent technical agreement with the widely adopted RAPID platform, which gained prominence through its use in the seminal DAWN and DEFUSE-3 trials [18]. Table 2 summarizes the key volumetric agreement metrics from recent comparative studies.

Table 2: Volumetric Agreement Between Automated Perfusion Software Platforms

| Software Comparison | Imaging Modality | Ischemic Core Agreement (CCC) | Hypoperfused Volume Agreement (CCC) | Study Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JLK PWI vs. RAPID | MRI PWI | 0.87 (p<0.001) | 0.88 (p<0.001) | [2] [15] |

| JLK-CTP vs. RAPID | CT Perfusion | 0.958 (95% CI: 0.949-0.966) | 0.835 (95% CI: 0.806-0.863) | [14] |

| UKIT vs. MIStar | CT Perfusion | r=0.982 (ICC=0.902) | r=0.979 (ICC=0.956) | [5] |

| Viz.ai vs. RAPID | CT Perfusion | Mean difference: 8cc (p<0.001) | Mean difference: 18cc (p<0.001) | [21] |

The high concordance across multiple platforms and imaging modalities indicates successful standardization of the core analytical approaches initially validated in the DAWN and DEFUSE-3 trials. Notably, the strongest agreement was observed for ischemic core volume estimation, which represents the most critical parameter for EVT eligibility decisions according to DAWN/DEFUSE-3 criteria [2] [14] [5]. The slightly lower but still substantial agreement for hypoperfused volumes (Tmax >6s) reflects the greater complexity in calculating delayed time-to-maximum parameters, yet remains clinically robust [14].

Clinical Decision Concordance for EVT Eligibility

The ultimate test of perfusion software reliability lies in its consistency for determining EVT eligibility based on DAWN and DEFUSE-3 criteria. Recent validation studies have specifically evaluated this clinical endpoint, recognizing that even technically accurate software must produce consistent treatment decisions to be clinically viable. The JLK PWI software demonstrated very high concordance with RAPID for DAWN criteria across subgroups (κ=0.80-0.90) and substantial agreement for DEFUSE-3 criteria (κ=0.76) [2] [15]. Similarly, in CTP analysis, UKIT showed excellent agreement with MIStar for both EXTEND (κ=0.73) and DEFUSE-3 (κ=0.73) eligibility classifications [5].

A multicenter comparison of Viz.ai and RAPID.AI found that despite statistically significant differences in absolute volume estimates (8cc for core, 18cc for penumbra), these differences did not translate to significantly different DEFUSE-3 eligibility rates in primary analysis [21]. However, subgroup analysis revealed that scanner-specific variability could influence eligibility determinations at individual centers, highlighting the importance of local protocol optimization [21]. This finding underscores that software performance is modulated by scanning parameters and hardware, necessitating site-specific validation rather than assuming universal performance.

Visualization of Software Validation Workflow

Figure 1: Software Validation Workflow from Trial Criteria to Clinical Implementation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Perfusion Software Validation

| Item | Function/Role in Validation | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| CT Perfusion Scanners | Image acquisition across multiple vendors and models | Philips Brilliance iCT 256, Canon Aquilion One [14] [21] |

| MRI Systems | PWI and DWI data collection with varied field strengths | 3.0T and 1.5T systems (GE, Philips, Siemens) [2] |

| Contrast Agents | Bolus tracking for perfusion parameter calculation | Iomeprol 400 (CT), Gadolinium-based (MRI) [2] [14] |

| Reference Software | Established platform for comparison | RAPID (iSchemaView), MIStar [2] [5] |

| Test Software Platforms | New solutions under evaluation | JLK PWI, JLK-CTP, UKIT, Viz.ai [2] [14] [5] |

| Validation Datasets | Multicenter patient cohorts with imaging and outcomes | 299-327 patients with follow-up DWI [2] [14] |

| Statistical Packages | Agreement analysis and visualization | Stata V.17, R packages for CCC and Bland-Altman [22] |

Discussion and Future Directions

The comparative validation of automated perfusion analysis software represents a critical step in the translation of clinical trial evidence into routine practice. The high technical concordance between established platforms like RAPID and emerging solutions such as JLK and UKIT demonstrates successful implementation of the DAWN and DEFUSE-3 criteria foundations [2] [14] [5]. This standardization enables more widespread adoption of advanced imaging selection for EVT, particularly in centers where access to specific software platforms may be limited by cost or infrastructure.

Future developments in the field will likely focus on increasing spatial precision for medium vessel occlusions (MeVO), as recent trials have highlighted the need for more refined imaging biomarkers [2]. Additionally, the integration of collateral status assessment with traditional perfusion parameters may provide complementary selection criteria, particularly in centers where CTP is not readily available [22]. The observed scanner-specific variability in volume estimates and occasional eligibility discrepancies underscore the importance of local validation and protocol optimization between software vendors, scanner manufacturers, and clinical sites [21]. As artificial intelligence algorithms continue to evolve, we can anticipate further refinement of ischemic core and penumbra quantification, potentially incorporating non-contrast biomarkers and clinical variables to enhance prediction accuracy beyond the current DAWN and DEFUSE-3 frameworks.

Methodological Approaches and Clinical Implementation of Perfusion Software

Automated perfusion analysis software has become an indispensable tool in clinical neuroscience, particularly for acute ischemic stroke evaluation. These platforms rely on sophisticated algorithms to process complex magnetic resonance perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI) and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) data, transforming raw image data into quantifiable parameters that guide life-saving treatment decisions. The core algorithmic foundations underpinning these systems primarily involve deconvolution methods for hemodynamic parameter calculation and thresholding techniques for tissue classification. Deconvolution algorithms enable the precise calculation of cerebral blood flow by accounting for delay and dispersion effects in the contrast agent bolus, while thresholding approaches allow for the accurate segmentation of critically ischemic tissue from salvageable penumbra. Understanding these computational methodologies is essential for researchers and clinicians evaluating the growing landscape of automated perfusion solutions, as algorithmic differences directly impact volumetric measurements and subsequent treatment eligibility determinations.

The validation of new software platforms against established references represents a critical step in clinical translation. Recent comparative studies have systematically evaluated the performance of emerging tools against the commercially established RAPID platform, providing evidence-based insights into their reliability and clinical concordance. This guide objectively examines the algorithmic foundations, experimental validation data, and technical performance of currently available automated perfusion analysis solutions, with a specific focus on their application in acute stroke imaging and endovascular therapy selection.

Comparative Experimental Validation: JLK PWI vs. RAPID

Study Design and Methodology

A recent multicenter, retrospective validation study directly compared a newly developed perfusion analysis software (JLK PWI, JLK Inc., Republic of Korea) against the established RAPID platform (RAPID AI, CA, USA) [1] [2] [20]. The investigation involved 299 patients with acute ischemic stroke who underwent PWI within 24 hours of symptom onset at two tertiary hospitals in Korea. The study population had a mean age of 70.9 years, was 55.9% male, and presented with a median NIHSS score of 11 (IQR 5-17), representing a typical acute stroke cohort [1].

The experimental protocol employed standardized imaging acquisition across multiple scanner platforms (3.0T and 1.5T) from major vendors (GE, Philips, Siemens) [1] [2]. All perfusion MRI scans utilized dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced perfusion imaging with a gradient-echo echo-planar imaging (GE-EPI) sequence. To ensure methodological consistency, all datasets underwent standardized preprocessing and normalization prior to perfusion mapping, with comprehensive quality control excluding cases with abnormal arterial input function, severe motion artifacts, or inadequate images [2].

For infarct core estimation, each platform employed distinct but validated approaches. RAPID utilized the default apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) threshold of < 620 × 10⁻⁶ mm²/s, while JLK PWI implemented a deep learning-based infarct segmentation algorithm applied to the b1000 DWI images [1] [2]. Both systems calculated hypoperfused tissue volume using a Tmax > 6 seconds threshold and computed mismatch ratios between diffusion and perfusion lesions to identify patients who might benefit from endovascular therapy [2].

Table 1: Key Experimental Parameters in the Comparative Validation Study

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Study Population | 299 patients with acute ischemic stroke [1] |

| Study Design | Retrospective, multicenter [1] [2] |

| Median NIHSS | 11 (IQR 5-17) [1] |

| Median Time from Onset | 6.0 hours [1] [20] |

| Imaging Modality | Magnetic resonance perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI) [1] |

| Scanner Field Strengths | 3.0 T (62.3%) and 1.5 T (37.7%) [2] |

| Ischemic Core Definition | RAPID: ADC < 620 × 10⁻⁶ mm²/s; JLK: Deep learning segmentation [1] |

| Hypoperfusion Threshold | Tmax > 6 seconds for both platforms [1] [2] |

Statistical Analysis Framework

The comparative analysis employed multiple statistical approaches to evaluate agreement between the two platforms [1] [2]. Volumetric agreement for ischemic core, hypoperfused volume, and mismatch volume was assessed using concordance correlation coefficients (CCC), Pearson correlation coefficients, and Bland-Altman plots. The strength of agreement was classified using established benchmarks: poor (0.0-0.2), fair (0.21-0.40), moderate (0.41-0.60), substantial (0.61-0.80), and excellent (0.81-1.0) [2].

Clinical concordance in endovascular therapy (EVT) eligibility was evaluated using Cohen's kappa coefficient applied to classifications based on DAWN and DEFUSE-3 trial criteria [1] [20]. The DAWN classification stratified eligible infarct volume based on age and NIHSS into three prespecified categories, while DEFUSE-3 criteria utilized a mismatch ratio ≥ 1.8, infarct core volume < 70 mL, and absolute penumbra volume ≥ 15 mL [2]. Subgroup analyses were additionally performed for patients with anterior circulation large vessel occlusion to assess consistency across stroke subtypes.

Performance Results and Quantitative Comparisons

Volumetric Agreement Metrics

The comparative validation demonstrated excellent technical agreement between JLK PWI and RAPID across all key perfusion parameters [1] [2] [20]. For ischemic core volume estimation, the concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) reached 0.87 (p < 0.001), indicating highly consistent infarct identification despite different segmentation methodologies [1]. Similarly, hypoperfused volume assessment showed a CCC of 0.88 (p < 0.001), reflecting strong agreement in tissue-at-risk delineation [1]. These robust correlation metrics confirm that both platforms produce quantitatively similar volumetric assessments for critical decision-making parameters.

The high degree of technical concordance translated directly to clinical agreement. Bland-Altman analysis, which plots differences between measurements against their means, showed minimal systematic bias between the platforms across the spectrum of lesion volumes [1] [2]. This statistical approach provides greater insight into agreement patterns than correlation coefficients alone by revealing whether discrepancies are consistent across measurement ranges or exhibit proportional bias. The comprehensive volumetric agreement established through multiple statistical methods provides a solid foundation for considering these platforms interchangeable in clinical practice.

Table 2: Performance Agreement Between JLK PWI and RAPID Software

| Performance Metric | Ischemic Core Volume | Hypoperfused Volume | EVT Eligibility (DAWN) | EVT Eligibility (DEFUSE-3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concordance Correlation | CCC = 0.87 [1] | CCC = 0.88 [1] | κ = 0.80-0.90 [1] | κ = 0.76 [1] |

| Statistical Significance | p < 0.001 [1] | p < 0.001 [1] | Not specified | Not specified |

| Agreement Classification | Excellent [2] | Excellent [2] | Very High [1] | Substantial [1] |

Clinical Decision Concordance

The most clinically significant outcome of the comparative analysis was the high level of agreement in endovascular therapy eligibility classification [1] [20]. When applying DAWN trial criteria, which stratify patients based on age, NIHSS score, and infarct core volume, the agreement between JLK PWI and RAPID reached Cohen's kappa values of 0.80-0.90 across subgroups, representing very high concordance [1]. Similarly, assessment using DEFUSE-3 criteria demonstrated substantial agreement with a kappa of 0.76 [1]. These robust agreement metrics indicate that both platforms would recommend the same treatment approach for the vast majority of patients, supporting the clinical interchangeability of the software solutions.

For the small proportion of cases with discordant classifications, additional analysis revealed specific patterns. Most discrepancies occurred in patients with borderline imaging characteristics, particularly those with infarct volumes or mismatch ratios near inclusion thresholds [2]. These findings highlight the importance of understanding the subtle algorithmic differences between platforms when interpreting results for marginal cases. Nevertheless, the overall high clinical concordance supports JLK PWI as a reliable alternative to RAPID for MRI-based perfusion analysis in acute stroke care [1] [20].

Technical Foundations: Core Algorithms Explained

Deconvolution Methods in Perfusion Analysis

Deconvolution algorithms form the computational backbone of perfusion analysis, enabling the calculation of hemodynamic parameters from dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced MRI data [17]. The fundamental principle involves solving a tracer kinetic model that relates the observed concentration time curve in tissue to the arterial input function (AIF), which represents the contrast agent concentration arriving at the tissue vasculature [17]. The mathematical relationship is expressed through the convolution integral:

Cₘ(t) = k(t) * Cₐᵢ𝒻(t)

Where Cₘ(t) represents the measured tissue concentration curve, Cₐᵢ𝒻(t) is the arterial input function, k(t) is the ideal tissue response without delay or dispersion effects, and * denotes the convolution operation [17]. Deconvolution is the inverse process that extracts k(t) from the measured Cₘ(t) and Cₐᵢ𝒻(t), enabling calculation of critical perfusion parameters including cerebral blood flow (CBF), cerebral blood volume (CBV), and mean transit time (MTT) [17].

Practical implementation of deconvolution in clinical software typically employs block-circulant single value deconvolution approaches, which effectively handle delay and dispersion effects commonly encountered in pathological cerebrovascular conditions [1] [2]. The JLK PWI software follows this established methodology, incorporating automated arterial input function selection alongside deconvolution-based parameter calculation [1]. The resulting perfusion maps (CBF, CBV, MTT, Tmax) provide the foundation for subsequent tissue classification through thresholding techniques.

Thresholding Techniques for Tissue Classification

Thresholding represents the fundamental segmentation method for categorizing tissue viability based on quantitative perfusion parameters [23] [24]. In acute stroke imaging, thresholding algorithms convert continuous parameter maps into discrete tissue classes (e.g., ischemic core, penumbra) by applying specific cutoff values [23]. The JLK PWI and RAPID platforms both employ threshold-based approaches, though their implementation differs in specific methodology.

Global thresholding techniques apply fixed cutoff values across entire images, making them computationally efficient but potentially less adaptable to varying image quality or physiological conditions [23]. RAPID utilizes this approach with its established ADC threshold of < 620 × 10⁻⁶ mm²/s for ischemic core definition [2]. In contrast, JLK PWI implements a deep learning-based segmentation algorithm applied to b1000 DWI images, which can be considered an advanced, adaptive thresholding approach that learns optimal feature boundaries from training data [1] [2]. For hypoperfused tissue delineation, both platforms use a Tmax > 6 seconds threshold, reflecting the established literature linking this parameter to critically hypoperfused tissue [1].

The evolution of thresholding methodologies in medical imaging has progressed from simple global thresholds to more sophisticated adaptive and learning-based approaches [23] [24]. Modern implementations must balance computational efficiency with biological accuracy, particularly in heterogeneous conditions like acute stroke where tissue viability exists along a continuum rather than as discrete categories. The continued refinement of these classification algorithms represents an active area of research in medical image computing.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Perfusion Analysis Development

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Programming Frameworks | Python [17] | Flexible development environment for implementing deconvolution algorithms and thresholding methods |

| Image Processing Libraries | OpenCV [23] | Provides foundational algorithms for image thresholding, segmentation, and morphological operations |

| Deconvolution Algorithms | Block-circulant SVD [1] [17] | Enables calculation of perfusion parameters by solving the tracer kinetic model |

| Thresholding Methods | Global thresholding, Otsu's method [23] | Segments continuous parameter maps into discrete tissue classifications |

| Validation Methodologies | Concordance correlation, Bland-Altman, Cohen's kappa [1] [2] | Statistical frameworks for comparing software performance and clinical agreement |

| Reference Platforms | RAPID software [1] [2] [20] | Established commercial solution serving as benchmark for new development |

The comparative validation of automated perfusion analysis software demonstrates that both established and emerging platforms can achieve excellent technical and clinical agreement when built on robust algorithmic foundations. The strong concordance between JLK PWI and RAPID across both volumetric parameters (CCC 0.87-0.88) and treatment eligibility classifications (κ 0.76-0.90) provides empirical support for the reliability of well-implemented deconvolution and thresholding methods in acute stroke imaging [1] [20].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings highlight several important considerations. First, the methodological transparency in algorithm implementation facilitates appropriate tool selection for specific research contexts. Second, the validation frameworks established in these comparative studies provide templates for evaluating future software innovations. Finally, the growing availability of open-source perfusion analysis tools [17] creates opportunities for methodological advancement and standardization in the field. As perfusion imaging continues to evolve, particularly with emerging applications in medium vessel occlusion and personalized treatment approaches [1] [2], the algorithmic foundations of deconvolution and thresholding will remain essential components of accurate, reliable clinical decision support systems.

Accurate estimation of the ischemic core—the irreversibly infarcted brain tissue in acute ischemic stroke—is paramount for therapeutic decision-making and predicting patient outcomes. The quantification primarily relies on thresholds applied to perfusion and diffusion parameters derived from advanced neuroimaging, namely computed tomography perfusion (CTP) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This guide provides a comparative analysis of the key parameters: relative Cerebral Blood Flow (rCBF), Cerebral Blood Volume (CBV), and Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC). We objectively evaluate their performance, along with the automated software platforms that implement them, within the broader context of ongoing research into the comparative validation of automated perfusion analysis software.

Quantitative Threshold Comparison

The following table summarizes the key parameters and their established thresholds for ischemic core estimation across different imaging modalities and software platforms.

Table 1: Key Parameters and Thresholds for Ischemic Core Estimation

| Parameter | Full Name | Imaging Modality | Typical Ischemic Core Threshold | Primary Software/Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rCBF | Relative Cerebral Blood Flow | CT Perfusion (CTP) | < 30% of contralateral hemisphere [3] [25] | RAPID, UGuard, StrokeViewer |

| rCBF | Relative Cerebral Blood Flow | CT Perfusion (CTP) | < 22% (for immediate post-EVT DWI) [26] | Optimal threshold varies with timing [26] |

| CBV | Cerebral Blood Volume | CT Perfusion (CTP) | < 1.2 mL/100 mL [4] | syngo.via (Setting A) |

| ADC | Apparent Diffusion Coefficient | MRI - Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI) | < 620 × 10⁻⁶ mm²/s [2] [1] | RAPID, JLK PWI (for coregistration) |

Performance Data and Software Agreement

Validation of these thresholds is performed by comparing software-estimated core volumes against the follow-up infarct volume on Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI), which is often considered a reference standard [25]. The table below synthesizes performance metrics from recent comparative studies of automated software.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Automated Perfusion Analysis Software

| Software (Modality) | Compared Platform | Core Estimation Metric | Volumetric Agreement (with DWI or other platform) | Key Findings / Clinical Concordance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| StrokeViewer (CTP) [25] | Follow-up DWI | rCBF < 30% | ICC = 0.60 (Moderate) [25] | Dice = 0.20; severe overestimation (>50 mL) was uncommon (7%) [25] |

| UGuard (CTP) [3] | RAPID | rCBF < 30% | ICC = 0.92 (Strong) [3] | Predictive performance for clinical outcome comparable to RAPID, with higher specificity [3] |

| JLK PWI (MRI) [2] [1] | RAPID | Deep learning on DWI & Tmax > 6s for hypoperfusion | CCC = 0.87 (Excellent) for core [2] [1] | High EVT eligibility concordance (κ = 0.80-0.90 for DAWN criteria) [2] [15] |

| Cercare Medical Neurosuite (CTP) [4] | syngo.via | Model-based CBF quantification | Specificity: 98.3% (in excluding stroke) [4] | Superior specificity in ruling out lacunar infarcts compared to syngo.via settings [4] |

| syngo.via (CTP) [4] | Follow-up DWI | CBV < 1.2 mL/100 mL | Specificity: Lower than CMN [4] | Prone to false-positive core estimations [4] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validation of CTP rCBF Thresholds Against DWI

This protocol is central to studies like Kim et al. (2025) that seek to define optimal rCBF thresholds [26].

- Study Population: Acute ischemic stroke patients with large vessel occlusion (LVO) who achieved successful recanalization after endovascular therapy (EVT).

- Imaging Acquisition:

- Baseline CTP: Performed upon hospital arrival.

- Follow-up DWI: Acquired at two time points: immediately post-EVT (within 3 hours) and delayed (between 24-196 hours).

- Image Post-processing: CTP data is processed using automated software to calculate core volumes at a spectrum of rCBF thresholds (e.g., from 20% to 40%).

- Validation Analysis: The core volumes estimated from each rCBF threshold on CTP are statistically correlated (e.g., using Pearson correlation) with the final infarct volumes measured on both the immediate and delayed DWI scans. The threshold yielding the best correlation coefficient is identified as optimal [26].

- Key Variables: The time interval between CTP acquisition and successful recanalization is a critical covariate, as it is inversely correlated with the accuracy of core estimation [26].

Protocol 2: Multi-Center Software Comparison for EVT Triage

This protocol, used in studies such as the JLK PWI validation, assesses the clinical reliability of new software [2] [1].

- Study Design: Retrospective, multi-center analysis of patients with acute ischemic stroke.

- Imaging & Processing: Patients underwent perfusion-weighted MRI (PWI) within 24 hours of symptom onset. The same imaging datasets are processed independently by the new software (e.g., JLK PWI) and an established reference platform (e.g., RAPID).

- Outcome Measures:

- Technical Agreement: Concordance correlation coefficients (CCC) and Bland-Altman plots are used to compare the volumetric outputs (ischemic core, hypoperfused volume) from the two software platforms.

- Clinical Agreement: Cohen's kappa statistic is used to evaluate the concordance in EVT eligibility decisions based on clinical trial criteria (DAWN, DEFUSE-3) derived from each software's output [2] [1].

Visual Workflows

Threshold Application and Core Estimation Logic

Software Validation and Clinical Decision Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key software and analytical tools essential for conducting research in automated perfusion analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Perfusion Analysis

| Tool Name | Type / Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| RAPID | Automated Perfusion Software | FDA-approved reference platform for quantifying ischemic core (rCBF<30%) and penumbra (Tmax>6s); serves as a common benchmark in comparative studies [2] [3]. |

| Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM12) | Statistical Analysis Toolbox | Used for voxel-based statistical analysis of brain images, including registration, normalization, and comparison of perfusion SPECT or other functional images to healthy control databases [27]. |

| ITK-SNAP | Image Segmentation Software | Open-source application for semi-automated and manual segmentation of medical images; used for precise delineation of follow-up infarct volumes on DWI for validation purposes [25]. |

| FSL Maths | Neuroimaging Analysis Tool | Part of the FMRIB Software Library (FSL); used for mathematical operations on neuroimages, such as calculating spatial agreement metrics (e.g., Dice similarity coefficient) between different lesion maps [25]. |

| Elastix | Image Registration Toolbox | Open-source software for rigid and non-rigid registration of medical images; critical for co-registering follow-up DWI scans to baseline CTP/MRI to enable voxel-wise spatial agreement analysis [25]. |

| JLK PWI | Automated PWI/DWI Software | Emerging software for MRI-based perfusion analysis; utilizes deep learning for DWI infarct segmentation and provides core-penumbra mismatch using PWI (Tmax>6s) [2] [1]. |

| UGuard | Automated CTP Software | Novel AI-based CTP processing software that uses deep learning models for image preprocessing and vessel segmentation, claiming improved performance in core estimation [3]. |

In acute ischemic stroke, the accurate delineation of the ischemic penumbra—tissue that is functionally impaired but potentially salvageable with timely reperfusion—is paramount for guiding treatment decisions and improving patient outcomes [28]. Perfusion-weighted imaging (PWI), particularly through parameters such as Time-to-maximum (Tmax) and Mean Transit Time (MTT), serves as a critical tool for identifying this at-risk tissue [29]. The comparative performance of these parameters directly impacts the reliability of penumbral assessment in both clinical and research settings. This guide provides a systematic comparison of Tmax and MTT, synthesizing current validation evidence and experimental data to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in the field of cerebrovascular disease.

Parameter Fundamentals and Physiological Basis

Time-to-Maximum (Tmax)

Tmax is defined as the time at which the maximum value of the residue function occurs after deconvolution of the tissue concentration curve against an arterial input function (AIF) [30]. Deconvolution accounts for the specific shape of the arterial input, making Tmax a more direct measure of hemodynamic delay compared to non-deconvolved parameters. It represents the delay in bolus arrival between the tissue and the selected reference artery, expressed in seconds (s).

Mean Transit Time (MTT)

MTT represents the average time for blood to transit through the cerebral vasculature within a given volume of tissue. It is calculated from the ratio of Cerebral Blood Volume (CBV) to Cerebral Blood Flow (CBF) based on the Central Volume Principle (MTT = CBV / CBF) [30] [31]. In practice, MTT prolongation (MTTp) is often used, calculated as the difference between the MTT in the ischemic hemisphere and the median MTT in the contralateral hemisphere [30].

Table: Fundamental Characteristics of Tmax and MTT

| Feature | Tmax | MTT (MTTp) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Time to maximum of the deconvolved residue function | Average time for blood to pass through the tissue vasculature (CBV/CBF) |

| Physiological Basis | Measure of contrast arrival delay | Reflects the efficiency of capillary-level blood flow |

| Calculation Method | Deconvolution of tissue curve with Arterial Input Function (AIF) | Often derived from CBV/CBF ratio; MTTp is the asymmetry vs. contralateral hemisphere |

| Units | Seconds (s) | Seconds (s) |

| Key Advantage | Less sensitive to cardiac output and input function variations; validated against PET | Intuitive physiological basis; uniform across gray and white matter |

Performance Comparison: Predictive Value for Clinical and Tissue Outcomes

Direct comparative studies provide the most robust evidence for evaluating parameter performance. A pivotal study prospectively compared MTT, TTP, and Tmax in 50 acute ischemic stroke patients undergoing serial MRI, assessing their power to predict neurological improvement and tissue salvage following early reperfusion [30].

Predictive Power for Neurological Improvement

The study used linear regression to determine how well percent reperfusion (%Reperf), defined for each parameter and threshold, predicted neurological improvement (ΔNIHSS = admission NIHSS – 1-month NIHSS) [30].

- MTTp: Percent reperfusion significantly predicted neurological improvement at all tested thresholds (3s, 4s, 5s, and 6s). The strongest association was found for MTTp >3s (p=0.0002) [30].

- Tmax: Percent reperfusion predicted neurological improvement for the Tmax >6s (p<0.05) and Tmax >8s (p<0.05) thresholds, but not for the shorter thresholds of 2s and 4s [30].

- TTP: Percent reperfusion did not significantly predict neurological improvement for any of the tested thresholds [30].

Predictive Power for Tissue Salvage

The correlation between the volume of reperfused tissue and the volume of tissue salvaged (initial perfusion deficit volume – final infarct volume) was assessed [30].

- MTTp: Tissue salvage was significantly correlated with reperfusion volume for all MTTp thresholds (3s, 4s, 5s, and 6s). The strongest correlations were for MTTp >3s and >4s (P<0.0001) [30].

- Tmax: A significant correlation with tissue salvage was observed only for the Tmax >6s threshold [30].

- TTP: No significant correlation with tissue salvage was found for any TTP threshold [30].

Table: Comparative Performance of Tmax and MTT in Predicting Outcomes from Prospective Clinical Study [30]

| Parameter & Threshold | Predicts Neurological Improvement? | Predicts Tissue Salvage? | Strength of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| MTTp >3s | Yes (p=0.0002) | Yes (P<0.0001) | Strongest association for both outcomes |

| MTTp >4s | Yes | Yes (P<0.0001) | Strong association |

| MTTp >5s | Yes | Yes | Significant association |

| MTTp >6s | Yes | Yes | Significant association |

| Tmax >6s | Yes | Yes | Significant association for both outcomes |

| Tmax >8s | Yes | Not reported | Significant for clinical improvement |

| Tmax >2s / >4s | No | No | Not significant |

The study concluded that MTT-defined reperfusion was the best predictor of both neurological improvement and tissue salvage in hyperacute ischemic stroke among the parameters tested [30].

Validation Against Gold-Standard Penumbra Imaging

Validation against positron emission tomography (PET), considered the historical gold standard for penumbra detection, provides critical insights into parameter accuracy.

Tmax Validation with 15O-PET

A key study validated a wide range of PWI maps against full quantitative 15O-PET (measuring CBF, OEF, and CMRO2) in patients up to 48 hours after stroke onset [29].

- Performance: Among all PW maps tested, Tmax demonstrated the best performance in detecting penumbral tissue as defined by PET, with an area-under-the-curve (AUC) of 0.88 [29].

- Optimal Threshold: The study determined that the optimal Tmax threshold to discriminate penumbra from benign oligemia was >5.6 seconds, providing a sensitivity and specificity of >80% [29].

- Clinical Utility: This supports the reliability of Tmax >5.6s for guiding treatment decisions up to 48 hours after stroke onset [29].

MTT and the Pathophysiological Context

PET studies have helped define the penumbra in terms of absolute flow thresholds. The ischemic penumbra is typically identified as tissue with a CBF between ~12 and 22 mL/100g/min, while the core is defined as CBF < ~12 mL/100g/min [28]. MTT, as a derivative of CBV and CBF, becomes prolonged in both these states, which can challenge its ability to perfectly distinguish core from penumbra without additional contextual data from CBF or CBV maps.

Application in Automated Perfusion Analysis Software

The translation of perfusion parameters into clinical practice is largely mediated by automated software platforms, which standardize processing and threshold application.

Dominant Paradigm in Commercial Software

The prevailing approach in major clinical trials and commercial software has coalesced around Tmax for defining hypoperfusion.

- RAPID Software: The widely used RAPID platform (RAPID AI) employs Tmax >6.0 seconds to define the critically hypoperfused tissue volume (penumbra) [1] [32] [2]. The ischemic core is typically defined using a relative CBF threshold <30% [33].

- Validation of New Platforms: Newer automated PWI software, such as JLK PWI, demonstrate excellent agreement with RAPID by also using a Tmax >6s threshold for hypoperfusion. One study reported a concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) of 0.88 for hypoperfused volume between JLK PWI and RAPID [1] [2].

Threshold Calibration Between Platforms

A significant challenge is that perfusion thresholds can vary between software due to differences in deconvolution algorithms. A systematic calibration method using a digital perfusion phantom demonstrated that thresholds are not universally portable [33].

- Finding: The reference thresholds (CBF <30%, Tmax >6s) used in model-independent deconvolution (e.g., RAPID) required calibration to CBF <15% and Tmax >6s when used with specific model-based deconvolution algorithms to maintain concordance in mismatch profiles [33].

- Implication: This highlights that absolute threshold values are algorithm-specific, and direct comparison of volumes across different software requires calibration rather than applying identical numeric thresholds [33].

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Validation

For researchers designing validation studies, the following methodologies provide a framework.

Clinical Outcome Validation Protocol

The protocol from the prospective comparative study offers a template for validating parameters against clinical and radiological outcomes [30].

- Patient Population: Acute ischemic stroke patients (e.g., NIHSS ≥5, anterior circulation stroke) imaged within the therapeutic window (e.g., <4.5 hours).

- Imaging Acquisition: Serial MRI scans including DWI and dynamic susceptibility contrast PWI at baseline (tp1) and early follow-up (e.g., 6 hours, tp2). A final infarct volume assessment is done at 1 month.

- Image Post-Processing:

- Calculate MTT, TTP, and Tmax maps using a defined AIF selection from the contralateral hemisphere.

- Employ block-circulant singular value decomposition for deconvolution to minimize time-lag effects [30].

- Define perfusion deficits at multiple common thresholds (e.g., MTTp: 3,4,5,6s; Tmax: 2,4,6,8s).

- Co-register all images across time points.

- Outcome Measures:

- Percent Reperfusion: (%Reperf) = [Volume of voxels with deficit at tp1 but not tp2] / [tp1 perfusion deficit volume].

- Neurological Improvement: ΔNIHSS = (admission NIHSS – 1-month NIHSS).

- Tissue Salvage: = [tp1 perfusion deficit volume] – [final infarct volume].

- Statistical Analysis: Use linear regression to fit %Reperf for each parameter/threshold as a predictor of ΔNIHSS, adjusting for baseline variables. Correlate reperfusion volume with tissue salvage volume.

Gold-Standard Validation Protocol

The protocol for validating against 15O-PET provides the highest level of physiological validation [29].

- Patient Population: Patients with acute/subacute hemispheric ischemic stroke, imaged within a designated time window (e.g., 48 hours).

- Multimodal Imaging Acquisition: Consecutive MRI (DWI and PWI) and quantitative 15O-PET imaging in a single session for clinically stable patients.

- PET Penumbra Definition: Use the gold-standard definition based on CMRO2 and OEF (e.g., preserved CMRO2 with increased OEF indicating misery perfusion) [28].

- Voxel-based Analysis: Perform voxel-based receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) analysis to evaluate the performance of each PWI map (Tmax, MTT, etc.) in detecting the PET-defined penumbra.

- Output: Determine the area-under-the-curve (AUC) for each parameter and identify the optimal threshold that maximizes sensitivity and specificity for penumbra detection.

Gold-Standard Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Reagents and Materials for Perfusion Imaging Validation Research

| Item | Function / Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Gadolinium-Based Contrast | MR contrast agent for PWI. Injected intravenously to track cerebral perfusion. | e.g., Gadolinium-DTPA; power-injected at ~5 mL/s [30]. |

| 15O-Labeled PET Tracers | Gold-standard for quantifying CBF and metabolism. | 15O-H2O (CBF), 15O-O2 (OEF), 15O-CO (CBV) [29]. |

| Deconvolution Algorithm | Mathematical process to derive quantitative perfusion parameters from raw data. | Model-independent (e.g., Fourier Transform) vs. model-based (e.g., plug-flow) [33]. |

| Arterial Input Function (AIF) | Reference concentration curve from a major feeding artery. Critical for deconvolution. | Manually or automatically selected from contralateral MCA [30]. |

| Automated Perfusion Software | Standardizes processing, threshold application, and volume calculation. | Platforms: RAPID, JLK PWI, MIStar, UKIT [1] [5]. |

| Image Co-registration Tool | Aligns images from different modalities and time points for voxel-wise analysis. | e.g., FSL FLIRT for rigid registration [30]. |