Bridging Minds and Machines: How Deep Learning Neural Networks Are Revolutionizing Neuroscience Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of deep learning neural networks in modern neuroscience and drug development.

Bridging Minds and Machines: How Deep Learning Neural Networks Are Revolutionizing Neuroscience Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of deep learning neural networks in modern neuroscience and drug development. It explores the foundational principles that link artificial and biological neural computation, details cutting-edge methodological applications in neuroimaging and signal processing, and addresses critical challenges in model optimization and robustness. By synthesizing validation frameworks and comparative analyses of traditional machine learning versus deep learning approaches, this resource equips researchers and pharmaceutical professionals with the knowledge to leverage these tools for enhanced brain mapping, neurological disorder diagnosis, and accelerated therapeutic discovery.

From Biological Neurons to Artificial Networks: Core Principles for Neuroscience Research

The pursuit of artificial intelligence has increasingly turned to its most powerful natural exemplar: the human brain. The architectural and functional parallels between deep neural networks (DNNs) and biological neural systems represent a frontier of interdisciplinary research, promising advancements in both computational intelligence and neuroscience. This technical guide examines the current state of brain-inspired neural network architectures, with particular emphasis on methodologies for quantifying their alignment with biological intelligence and their transformative applications in scientific domains such as drug development.

Research reveals that while DNNs have achieved remarkable performance in specific domains, their alignment with human neural processing remains partial. A 2025 study analyzing the representational alignment between humans and DNNs found that although both systems process similar visual and semantic dimensions, DNNs exhibit a pronounced visual bias compared to the semantic dominance observed in human cognition [1]. This divergence underscores the need for more nuanced architectural bridging to achieve truly brain-like artificial intelligence.

Architectural Foundations: Brain and Deep Neural Networks

Comparative Architecture Analysis

Both biological brains and artificial neural networks are fundamentally information-processing systems built upon networked computational units. However, their structural implementations reflect different optimization pressures and physical constraints.

| Architectural Feature | Human Brain | Deep Neural Networks |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Unit | Neuron (~86 billion) | Node/Artificial Neuron (Network-dependent) |

| Connectivity | Sparse, recurrent, 3D spatial organization | Typically dense, layered, abstract spatial relationships |

| Processing Style | Massive parallel processing with inherent recurrence | Primarily forward-pass parallel with optional recurrence |

| Learning Mechanism | Synaptic plasticity (Hebbian learning) | Gradient descent & backpropagation |

| Power Consumption | ~20 watts | Extremely high for training (orders of magnitude greater) |

| Key Strength | Unsupervised learning, energy efficiency, creativity | Supervised learning, precision, scalability [2] |

The brain operates as a dynamic, sparsely connected network where learning occurs through the modification of synaptic strengths over time. In contrast, DNNs typically employ dense, layered connectivity where learning is encoded in weight adjustments via backpropagation. While the brain excels at low-data learning and generalizes from limited examples, DNNs typically require massive datasets but demonstrate superior performance in well-defined tasks like large-scale image classification [2] [1].

Emerging Brain-Inspired Architectures

Several advanced neural architectures have moved beyond standard feedforward models to better capture brain-like processing:

Reservoir Computing (RC): This approach utilizes a fixed, randomly connected recurrent network (the reservoir) with only the readout layer being trainable. This structure dramatically reduces computational complexity while capturing temporal dynamics. Recent innovations include deep Echo State Networks (ESNs) with multiple reservoir layers, each tuned to different temporal scales, enhancing their ability to model complex time-series data [3].

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): GNNs operate directly on graph-structured data, mimicking the brain's ability to process relational information. By propagating information between connected nodes, they capture complex dependencies in data structures such as molecular graphs, social networks, and knowledge graphs [4].

Quantifying the Bridge: Methodologies for Alignment Measurement

Representational Similarity Analysis Framework

A 2025 study established a rigorous framework for comparing human and DNN representations by identifying latent representational dimensions underlying the same behavioral tasks [1]. The experimental protocol proceeded as follows:

Behavioral Task Selection: Researchers employed a triplet odd-one-out similarity task where participants (both human and DNN) select the most dissimilar object from sets of three images. This task captures fundamental similarity judgments that approximate categorization behavior.

Data Collection:

- Human Data: ~4.7 million odd-one-out judgments across 1,854 diverse object images from the THINGS database.

- DNN Data: 20 million triplet judgments across 24,102 images using a VGG-16 model trained on ImageNet. DNN similarity was computed via dot products between penultimate layer activations.

Embedding Optimization: A variational embedding technique with sparsity and non-negativity constraints was applied to both human and DNN choice data to derive low-dimensional, interpretable representations.

Dimension Interpretation: Independent human raters labeled identified dimensions, allowing for qualitative assessment and comparison of the semantic and visual properties captured by each system.

Experimental Findings on Representational Alignment

The application of this framework yielded critical insights into the current state of brain-DNN alignment:

Quantitative Performance: The derived DNN embedding captured 84.03% of the total variance in image-to-image similarity, slightly exceeding the human embedding's 82.85% of total variance (91.20% of explainable variance given the empirical noise ceiling) [1].

Qualitative Divergence: Despite quantitative similarity, fundamental strategic differences emerged. Human representations were dominated by semantic properties (e.g., taxonomic categories), while DNN representations exhibited a striking visual bias (e.g., shape, color), indicating that similar behavioral outputs are driven by different internal representations [1].

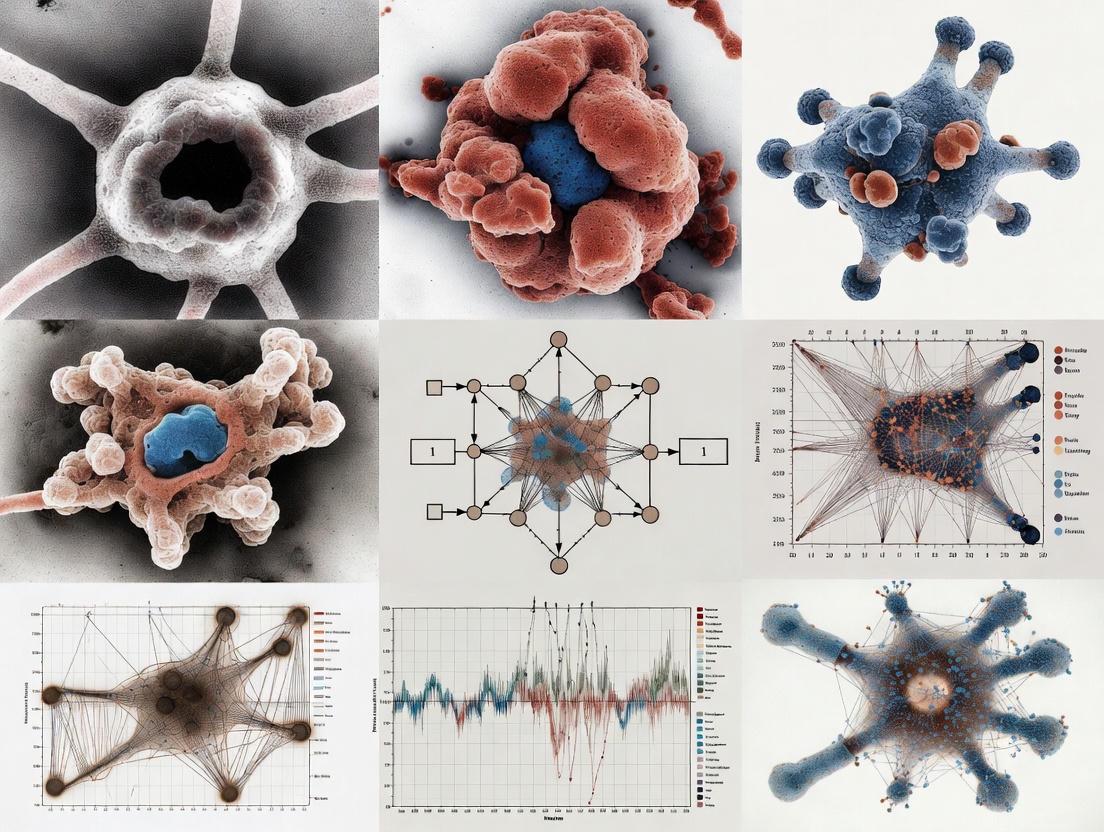

Visualizing the Representational Alignment Framework

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for comparing human and DNN representations, from data collection through to dimension analysis:

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for comparative representational analysis between humans and DNNs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Computational Materials

Implementing brain-inspired neural architectures requires specific computational frameworks and data resources. The following table details essential components for research in this domain.

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | THINGS database [1], ImageNet [1], DrugBank DDI datasets [5] | Provides standardized image and molecular data for training and evaluating model performance and representational alignment. |

| Network Architectures | VGG-16 [1], Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [5], Transformers [3], Deep Echo State Networks [3] | Serves as base models for testing architectural influences on brain-like emergent properties and task performance. |

| Analysis Frameworks | Representational Similarity Analysis (RSA) [1], Variational Embedding Techniques [1] | Enables quantitative measurement of the alignment between neural, human behavioral, and model representations. |

| Modeling & Simulation Tools | Neural Network Intelligence (NNI) [4], AutoML [4] | Automates the design and optimization of neural network architectures, mimicking evolutionary processes. |

| 3-Acetyl-6-bromoquinolin-4(1H)-one | 3-Acetyl-6-bromoquinolin-4(1H)-one | 3-Acetyl-6-bromoquinolin-4(1H)-one (CAS 99867-16-0). A brominated quinoline derivative for research use. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| N,N-Dimethyl-4-phenoxybutan-1-amine | N,N-Dimethyl-4-phenoxybutan-1-amine |

Application in Drug Development: Graph Neural Networks for Drug-Drug Interaction Prediction

The pharmaceutical domain offers a compelling case study for applying brain-inspired neural architectures to complex scientific problems. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as particularly transformative for predicting drug-drug interactions (DDIs), a critical challenge in patient safety and polypharmacy management [5] [4].

Methodological Protocol for DDI Prediction

The standard experimental protocol for GNN-based DDI prediction involves:

Graph Representation: Drugs are represented as nodes in a graph, with edges representing known or potential interactions. Node features are derived from molecular structures (e.g., SMILES strings) or biological properties [5].

Feature Propagation: Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) or Graph Attention Networks (GATs) propagate and transform node features across the graph structure, capturing the influence of neighboring nodes. Advanced implementations use skip connections and post-processing layers to enhance information flow and prediction accuracy [5].

Link Prediction: The model is trained to predict the existence or type of interaction (e.g., synergism vs. antagonism) between drug pairs, framing DDI prediction as a link prediction task on the drug graph [6].

Validation: Predictions are validated against known DDI databases (e.g., DrugBank), with experimental confirmation through in vitro or clinical studies serving as the gold standard [6].

Experimental Findings and Model Performance

Recent studies demonstrate the efficacy of brain-inspired architectures for DDI prediction:

Architectural Impact: Models such as GCN with skip connections and GraphSAGE with Neural Graph Networks (NGNN) have demonstrated competent accuracy, sometimes outperforming more complex architectures on benchmark DDI datasets [5].

Interpretability Advantage: Approaches like the Substructure-aware Tensor Neural Network (STNN-DDI) not only predict interactions but also identify critical substructure pairs responsible for these interactions, providing valuable insights for pharmaceutical chemists [5].

The following diagram visualizes the workflow for a GNN-based DDI prediction model, highlighting the key stages from data representation to prediction output:

Figure 2: Workflow for GNN-based Drug-Drug Interaction (DDI) prediction.

Quantitative Benchmarks: Performance of Brain-Inspired Models

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for different neural architectures discussed in this guide, highlighting their effectiveness in various tasks.

| Model Architecture | Primary Application | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| VGG-16 | Image Representation & Similarity | Captured 84.03% variance in image similarity judgments | [1] |

| GCN with Skip Connections | Drug-Drug Interaction Prediction | Competent accuracy on benchmark DDI datasets | [5] |

| GraphSAGE with NGNN | Drug-Drug Interaction Prediction | Competent accuracy on benchmark DDI datasets | [5] |

| Multi-Modal Transformers | Cross-Domain Reasoning | ~40% improved accuracy vs. single-modal models | [4] |

| Neural Architecture Search (NAS) | Automated Model Design | Up to 30% reduction in computational complexity | [4] |

| Hybrid AI Models | Integrated Reasoning | Up to 45% increase in interpretability | [4] |

The architectural bridge between deep neural networks and the human brain continues to be a rich source of innovation in artificial intelligence. While significant differences persist—particularly in learning efficiency, representational strategies, and energy consumption—the methodological frameworks for quantifying alignment have grown increasingly sophisticated. The application of brain-inspired principles, particularly through architectures like GNNs and Reservoir Computing, is already delivering tangible benefits in critical fields like drug development. Future research focused on integrating the brain's semantic dominance, unparalleled energy efficiency, and robust generalized learning capabilities will further strengthen this conceptual bridge, leading to more intelligent, adaptable, and trustworthy artificial systems.

Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) represent a paradigm shift in computational neuroscience, offering a biologically plausible model for simulating brain dynamics. Unlike traditional artificial neural networks (ANNs), SNNs process information through discrete, asynchronous spikes, closely mimicking the temporal coding and event-driven communication of the biological brain [7]. This in-depth technical guide explores the core principles, methodologies, and applications of SNNs, framing them within broader deep learning and neuroscience research. We provide a detailed analysis of their advantages in energy efficiency and spatio-temporal data processing, survey current experimental protocols and training methods, and discuss their transformative potential in neuroimaging and drug discovery. The document serves as a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to leverage brain-inspired computing models.

The pursuit of artificial intelligence has long been inspired by the human brain, yet most mainstream deep learning models diverge significantly from biological neural processes. Traditional ANNs, characterized by continuous-valued activations and synchronous operations, face substantial challenges in capturing the dynamic, temporal nature of brain activity [8] [7]. Their limited temporal memory and high computational demands render them suboptimal for processing the complex spatiotemporal patterns inherent in neuroimaging data and neural signaling [7].

Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) address this gap by incorporating key principles of biological computation. In SNNs, neurons communicate through discrete electrical impulses (spikes) across time, enabling event-driven, asynchronous processing [7]. This operational paradigm allows SNNs to leverage temporal information as a critical component of computation, making them exceptionally well-suited for modeling brain dynamics, processing real-time sensor data, and achieving unprecedented energy efficiency through sparse, event-driven activation [9]. Their biological plausibility extends beyond mere inspiration, offering a functional framework for simulating neurobiological processes and interpreting complex brain data.

SNN Fundamentals: Core Principles and Neural Dynamics

Biological Fidelity and Key Concepts

SNNs distinguish themselves from traditional ANNs through several core concepts that closely mirror neurobiology. Spiking neurons serve as the fundamental building blocks, communicating via discrete events called spikes, analogous to action potentials in biological neurons [7]. Information in SNNs is encoded not just in the rate of these spikes but also in their precise temporal timing and relative latencies, enabling a rich, time-based representation of data [8]. The network operates on an event-driven basis, where computations are triggered only upon the arrival of spikes, leading to significant energy savings [7]. This architecture is inherently biologically plausible, mimicking the brain's efficient, low-power communication mechanisms [10].

Neuron Models

The behavior of spiking neurons is mathematically captured by several models, balancing biological realism with computational tractability.

Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF): This is the most widely used model in applied SNN research. The neuron's membrane potential ( Vm ) integrates incoming postsynaptic potentials. It 'leaks' over time, described by a membrane time constant ( \taum ), mimicking the diffusion of ions across a biological membrane. When ( Vm ) reaches a specific threshold ( V{th} ), the neuron fires a spike and ( V_m ) is reset to a resting potential [7].

The membrane dynamics are governed by the differential equation:

( \taum \frac{dVm}{dt} = -(Vm - V{rest}) + R_m I(t) )

where ( R_m ) is the membrane resistance and ( I(t) ) is the input current.

Hodgkin-Huxley (H-H): This is a complex, biophysically detailed model that describes how action potentials in neurons are initiated and propagated through voltage-gated ion channels. While offering high biological fidelity, its computational complexity limits its use in large-scale network simulations [7].

The following diagram illustrates the dynamics and spike generation mechanism of a Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) neuron, which is central to SNN operation.

SNNs vs. Traditional Deep Learning: A Comparative Analysis

The differences between SNNs and traditional Deep Learning (DL) models are foundational, impacting their applicability, efficiency, and interpretability. The table below provides a structured comparison of the most relevant aspects.

Table 1: Conceptual Overview Comparing Deep Learning (DL) and Spiking Neural Networks (SNN). [8]

| Aspect | Deep Learning (DL) Models | Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) |

|---|---|---|

| Neuron Model | Continuous-valued activation functions (e.g., ReLU, Sigmoid) | Discrete, event-driven spiking neurons (e.g., LIF) |

| Information Encoding | Rate-based; information in numerical values | Temporal coding; information in spike timing and rates |

| Computation | Synchronous, layer-wise propagation | Asynchronous, event-driven processing |

| Temporal Dynamics | Limited (requires specific architectures like RNNs) | Native, inherent capability |

| Power Consumption | High, due to dense matrix multiplications | Low, potential for high energy efficiency on neuromorphic hardware |

| Biological Plausibility | Low | High |

| Data Type | Static, frame-based | Dynamic, spatiotemporal data streams |

Quantitative Performance and Applications

SNNs have demonstrated superior performance in tasks involving temporal data processing. Thematic analysis of recent research publications shows a significant surge in SNN applications, particularly in neuroimaging. One review of 21 selected publications highlights that SNNs outperform traditional DL approaches in classification, feature extraction, and prediction tasks, especially when combining multiple neuroimaging modalities [8].

Quantitative benchmarks on neuromorphic datasets reveal distinct advantages. For instance, experiments like Spike Timing Confusion and Temporal Information Elimination on the DVS-SLR dataset (a large-scale sign language action recognition dataset) substantiate that SNNs achieve higher accuracy and robustness on data with strong temporal correlations, a domain where traditional ANNs struggle [11]. The annual publication trend shows a notable surge, with five SNN studies in 2023, marking a significant shift toward practical implementation and reflecting growing confidence in the field [8].

Experimental Protocols and Training Methodologies

Implementing and training SNNs requires specialized approaches to handle their discrete, non-differentiable nature. Below is a summary of the primary methods used in the field.

Table 2: Primary Training Methods for Spiking Neural Networks.

| Method | Core Principle | Advantages | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANN-to-SNN Conversion [12] | Mapping a trained ANN to an equivalent SNN by substituting activation functions with spiking neurons. | Leverages mature ANN training techniques; achieves high accuracy on large-scale datasets. | Can result in high latency; limited ability to process continuous temporal inputs. |

| Surrogate Gradient Learning [11] | Using a continuous surrogate function during backpropagation to approximate the gradient of the non-differentiable spike function. | Enables direct, efficient training; can handle native temporal input streams. | Choice of surrogate function can impact performance and stability. |

| Bio-plasticity Rules (e.g., STDP) [12] | Employing local, unsupervised learning rules like Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity, which strengthens/weakens connections based on relative spike times. | High biological plausibility; potential for ultra-low-power on-chip learning. | Typically used for unsupervised tasks; scaling to deep, complex networks is difficult. |

Cross-Modality Fusion Experiment Protocol

A cutting-edge experimental protocol involves fusing multiple data modalities within an SNN framework. The following workflow, based on the Cross-Modality Attention (CMA) model, details this process for action recognition using event-based and frame-based video data [11].

- Data Preparation: The DVS-SLR dataset is used, containing event streams and synchronized color frame data for sign language actions. Events are formatted as spatio-temporal tensors (X, Y, T), while frames are standard RGB images [11].

- Encoding: Frame data is converted into spike trains using a rate-coding or direct input encoding method. The event stream is natively represented as spikes.

- Network Architecture: A hybrid SNN architecture is constructed with two input pathways for event and frame data. The core of the network is the Cross-Modality Attention (CMA) module.

- CMA Module Operation:

- Spatial-wise CMA: The spatial-wise spike rate of the frame features is computed. A learnable 2D nonlinear convolutional mapping produces spatial attention scores. These scores are cross-fused with the event features to enhance them spatially.

- Temporal-wise CMA: The temporal-wise spike rate of the event features is computed. A learnable 1D nonlinear mapping produces temporal attention scores. These scores are cross-fused with the frame features to enhance them temporally [11].

- Training & Evaluation: The network is trained end-to-end using a surrogate gradient method (e.g., Spatio-Temporal Backpropagation - STBP). Performance is evaluated based on action recognition accuracy and robustness under varying conditions (e.g., different lighting) [11].

The following diagram visualizes this Cross-Modality Attention (CMA) workflow for fusing event and frame data.

For researchers embarking on SNN projects, particularly in neuroimaging and computational neuroscience, the following tools and datasets are indispensable.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for SNN Development and Experimentation.

| Resource Category | Name / Example | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Software Frameworks | NeuCube [7] | A brain-inspired SNN architecture specifically designed for spatiotemporal brain data analysis, personalized modeling, and biomarker discovery. |

| SpikingJelly [12] | A comprehensive Python-based framework that provides a unified platform for SNN simulation, training, and deployment. | |

| Norse [12] | A library for deep learning with SNNs, built on PyTorch, focusing on gradient-based learning. | |

| Neuromorphic Datasets | DVS-SLR [11] | A large-scale, dual-modal dataset for sign language recognition, featuring high temporal correlation and synchronized event-frame data. |

| N-MNIST [11] | A neuromorphic version of the MNIST dataset, captured with an event-based camera. | |

| Hardware Platforms | SpiNNaker [10] | A massively parallel architecture designed to model large-scale spiking neural networks in biological real-time. |

| Neuromorphic Chips (e.g., Loihi, TrueNorth) | Specialized hardware that mimics the brain's architecture to run SNNs with extreme energy efficiency. |

Applications in Neuroscience and Drug Discovery

The unique properties of SNNs make them particularly valuable for applications in neuroscience and therapeutic development.

Multimodal Neuroimaging and Disease Diagnosis

SNNs excel at integrating and analyzing diverse neuroimaging data. The NeuCube framework, for example, uses a 3D brain-like structure to map and model neural activity from modalities like EEG, fMRI, and sMRI [7]. This allows for:

- Early Diagnosis: SNN models can identify complex, spatiotemporal patterns indicative of neurological disorders such as Alzheimer's disease, enabling early detection [8] [7].

- Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs): Their low power consumption and real-time processing capabilities make SNNs ideal for portable EEG systems and BCIs, facilitating direct communication between the brain and external devices [7].

- Biomarker Discovery: By processing large-scale datasets like ADNI (Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative), SNNs can help discover and quantify novel biomarkers for conditions like schizophrenia and epilepsy [8] [7].

Potential in Drug Discovery Programs

While the application of SNNs in drug discovery is nascent, their potential is significant. Traditional DNNs, such as Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs) and Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs), are already used to predict key ADME properties (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion) and biological activity (e.g., factor Xa inhibition) [13]. SNNs could extend these capabilities by:

- Modeling Dynamic Processes: Simulating the temporal dynamics of drug-receptor interactions or the propagation of neuronal signals in response to a compound.

- Enhancing Explainability: Their more biologically plausible structure may offer more interpretable insights into Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR), helping medicinal chemists understand a model's predictions [13].

- Efficient Large-Scale Screening: The energy efficiency of SNNs could enable the screening of massive virtual compound libraries against complex, dynamic biological targets at a fraction of the computational cost.

The field of SNN research is rapidly evolving, with several key directions shaping its future. Hybrid ANN-SNN models are gaining traction, combining the ease of training of ANNs with the energy-efficient execution of SNNs [7]. The development of specialized neuromorphic hardware (e.g., from Intel, IBM) is crucial for unlocking the full, low-power potential of SNNs for edge computing and real-time applications [9]. Furthermore, the emerging field of Spiking Neural Network Architecture Search (SNNaS) aims to automate the design of optimal SNN topologies, navigating the complex interplay between model architecture, learning rules, and hardware constraints [9].

In conclusion, Spiking Neural Networks represent a significant advancement toward biologically plausible and computationally efficient models of brain dynamics. Their inherent ability to process spatiotemporal information, combined with their low power profile, positions them as a transformative technology for neuroscience research and beyond. As software frameworks mature and neuromorphic hardware becomes more accessible, SNNs are poised to play a pivotal role in deciphering neural mechanisms, advancing personalized medicine, and accelerating the drug discovery process. For researchers and drug development professionals, embracing this brain-inspired paradigm offers a compelling path to more interpretable, efficient, and dynamic AI models.

Key Advantages of Deep Learning over Traditional Machine Learning in Neuroscience

The field of neuroscience is experiencing a fundamental transformation driven by the emergence of deep learning (DL) methodologies. While traditional machine learning (SML) approaches have contributed valuable insights, they often rely on manually engineered features and pre-specified relationships that limit their capacity to model the brain's complex, hierarchical organization. DL architectures, particularly deep neural networks, offer a radically different approach by automatically learning discriminative representations directly from raw or minimally processed neural data [14]. This capability is especially valuable in neuroscience, where the relationships between brain structure, neural activity, and behavior manifest across multiple scales of organization—from molecular and cellular circuits to whole-brain systems.

The exchange of ideas between neuroscience and artificial intelligence represents a bidirectional flow of inspiration. Historically, artificial neural networks were originally inspired by biological neural systems [15] [16]. Today, neuroscientists are increasingly adopting DL not merely as an analytical tool but as a framework for developing functional models of brain circuits and testing hypotheses about neural computation [17]. This whitepaper examines the key advantages of DL over SML in neuroscience research, with particular emphasis on representation learning, scalability, and biomarker discovery—critical considerations for researchers and drug development professionals working to advance our understanding of neural systems.

Theoretical Foundations: Core Computational Advantages

Representation Learning from Raw Data

The most significant advantage DL offers neuroscience is automated feature learning from complex, high-dimensional data. Unlike SML approaches that require manual feature engineering as a prerequisite step, DL models learn hierarchical representations directly from data, preserving spatial and temporal relationships that may be lost during manual feature extraction [14].

In practical neuroscience applications, this means DL models can process raw neuroimaging data such as structural MRI, fMRI, or microscopy images without relying on pre-defined regions of interest or hand-crafted features. For example, when applied to structural MRI data, 3D convolutional neural networks (CNNs) learn discriminative features directly from whole-brain gray matter maps, discovering patterns that might be overlooked in manual feature engineering processes [14]. This capability is particularly valuable for identifying novel biomarkers or detecting subtle patterns associated with neurological disorders that lack clearly established neural signatures.

Handling Nonlinear Neural Representations

Neural systems exhibit profoundly nonlinear dynamics that are difficult to capture with traditional linear models. DL architectures excel at modeling these complex relationships through multiple layers of nonlinear transformations [14]. The hierarchical organization of DL models mirrors the nested complexity of neural systems, enabling them to detect patterns that emerge from interactions across multiple spatial and temporal scales.

Evidence for these nonlinearities in neural data comes from systematic comparisons demonstrating that DL models significantly outperform linear methods on various neuroimaging tasks. For instance, in age and gender classification from structural MRI, DL models achieved 58.22% accuracy compared to 51.15% for the best-performing kernel-based SML method—a substantial improvement attributable to DL's capacity to exploit nonlinear patterns in the data [14].

Specialized Architectures for Neural Data

DL offers specialized architectures that can be customized for specific neuroscience applications:

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) excel at processing spatially structured neural data, including brain images from microscopy and MRI [18] [17]

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, effectively model temporal sequences in neural spike trains and electrophysiological recordings [18]

- Autoencoders enable dimensionality reduction and generative modeling of neural population activity [18]

- Neural Turing Machines and similar architectures provide models for memory processes that can be related to hippocampal and cortical memory systems [18]

These specialized architectures allow researchers to tailor their analytical approach to the specific properties of neural data, moving beyond the one-size-fits-all limitations of many SML methods.

Table 1: Performance Comparison Between DL and SML on Neuroimaging Tasks

| Method Category | Representative Models | Average Accuracy | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Machine Learning (SML) | Linear Discriminant Analysis, SVM with linear/RBF kernels | 44.07%-51.15% | Requires manual feature engineering, limited nonlinear modeling |

| Deep Learning (DL) | 3D CNN (AlexNet variants) | 58.19%-58.22% | High computational demands, requires large sample sizes |

| Performance Delta | - | +7.04-14.15% improvement | - |

Performance data from large-scale comparison on structural MRI data for 10-class age and gender classification task (n=10,000 samples) [14]

Empirical Validation: Quantitative Performance Advantages

Large-Scale Neuroimaging Studies

Comprehensive empirical comparisons demonstrate the performance advantages of DL approaches in neuroscience applications. In a systematic evaluation using structural MRI data from 12,314 subjects, DL models significantly outperformed SML approaches across multiple classification tasks [14]. The performance gap widened with increasing sample sizes, suggesting DL methods scale more effectively to large datasets—a crucial advantage in the era of big data in neuroscience.

Notably, this study found that linear SML methods (LDA, linear SVM) and nonlinear kernel methods (SVM with polynomial, RBF, and sigmoidal kernels) all performed substantially worse than DL models when evaluated in a standardized cross-validation framework. This performance advantage persisted across different feature reduction techniques (GRP, RFE, UFS), indicating that the limitation of SML approaches lies not in feature selection methods but in their fundamental inability to learn complex representations from high-dimensional neural data [14].

Scalability With Data Volume

A key advantage of DL methods is their ability to improve performance with increasing data volume, whereas SML methods typically plateau after reaching a certain sample size. In direct comparisons, DL models demonstrated continuous improvement as training samples increased from 1,000 to 10,000 subjects, while SML performance gains diminished much more rapidly [14]. This scalability makes DL particularly suited for large-scale neuroimaging initiatives such as the Human Connectome Project, UK Biobank, and ENIGMA consortium data.

Table 2: Scaling Properties of DL vs. SML Methods in Neuroimaging

| Training Sample Size | DL Accuracy | Best SML Accuracy | Performance Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | ~42% | ~38% | +4% |

| 5,000 | ~53% | ~47% | +6% |

| 10,000 | 58.22% | 51.15% | +7.07% |

Data adapted from large-scale structural MRI classification study showing DL's superior scaling with data volume [14]

Technical Implementation: Methodological Approaches

Experimental Protocols for DL in Neuroscience

Neuroimaging Analysis Pipeline

Implementing DL for neuroimaging requires specific methodological considerations:

Data Preprocessing: Minimal preprocessing is preferred to preserve information for representation learning. For structural MRI, this typically includes spatial normalization, tissue segmentation, and intensity normalization, but avoids strong spatial smoothing or feature selection [14].

Architecture Selection: 3D CNN architectures are typically employed for volumetric brain data. Common implementations adapt successful 2D architectures (e.g., AlexNet, ResNet) to 3D processing through volumetric convolutions [14].

Training Strategy: Due to limited labeled neuroimaging data, transfer learning approaches are often valuable, either from pre-trained models or through multi-task learning across related neurological conditions.

Regularization: Heavy regularization (dropout, weight decay, early stopping) is essential to prevent overfitting given the high dimensionality of neuroimaging data relative to typical sample sizes.

Validation: Nested cross-validation with strict separation of training, validation, and test sets is critical for unbiased performance estimation [14].

Microscopy Image Analysis Protocol

For analysis of neuronal microscopy images, DL implementations follow different considerations:

Image Segmentation: U-Net architectures or similar encoder-decoder structures are typically employed for segmenting neurons and subcellular structures [19].

Data Augmentation: Extensive augmentation (rotation, flipping, elastic deformations, intensity variations) is applied to increase effective training data size.

Multi-modal Integration: Combining different microscopy modalities (e.g., SIM, Airyscan, STED) often improves performance [19].

Transfer Learning: Models pre-trained on natural images are frequently fine-tuned on microscopy data to compensate for limited labeled examples.

Diagram: Comparative workflows for SML and DL approaches to neuroimaging analysis. The DL pathway integrates feature learning directly into the model, eliminating manual feature engineering.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for DL Applications in Neuroscience

| Tool/Category | Example Implementations | Neuroscience Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Probes | MemBright, GFP variants, Phalloidin | Plasma membrane and cytoskeletal labeling for neuronal segmentation [19] |

| Super-Resolution Microscopy | SIM, Airyscan, STED, STORM | Nanoscale imaging of synaptic components and dendritic spines [19] |

| DL Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow | Custom model development for neural data analysis [17] |

| Architecture Libraries | CNNs, RNNs, Autoencoders, Neural Turing Machines | Task-specific modeling of neural systems [18] [17] |

| Analysis Tools | Icy SODA plugin, Huygens software | Quantification of synaptic protein coupling and deconvolution [19] |

| 3-Bromo-2-oxocyclohexanecarboxamide | 3-Bromo-2-oxocyclohexanecarboxamide, CAS:80193-04-0, MF:C7H10BrNO2, MW:220.06 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3,6-Dibromophenanthrene-9,10-diol | 3,6-Dibromophenanthrene-9,10-diol|Research Chemical | 3,6-Dibromophenanthrene-9,10-diol is a key research intermediate for synthesizing advanced polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs). For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Domain-Specific Applications in Neuroscience Research

Neuroimaging and Biomarker Discovery

DL has revolutionized biomarker discovery from neuroimaging data. Unlike SML approaches that rely on predefined regions of interest, DL models can identify predictive patterns distributed across entire brain images, often revealing novel biomarkers that were not previously hypothesized [14]. For example, DL models trained to predict age from structural MRI data discover and leverage distributed morphological patterns that more accurately reflect brain aging than manually selected measurements.

Additionally, DL embeddings—the intermediate representations learned by neural networks—have been shown to encode biologically meaningful information about brain structure and function. These embeddings can be visualized and interpreted, providing insights into how the brain represents information across different domains [14]. The representations learned by DL models often correspond to neurobiologically plausible mechanisms, suggesting they capture genuine properties of neural organization rather than merely statistical artifacts.

Cellular Neuroscience and Drug Discovery

In cellular neuroscience, DL enables automated analysis of neuronal morphology and synaptic architecture. Super-resolution microscopy techniques combined with DL-based segmentation allow quantification of dendritic spines, synaptic proteins, and subcellular structures at nanometer resolution [19]. This capability is particularly valuable for studying neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative disorders, where subtle changes in synaptic architecture underlie functional deficits.

In drug discovery, DL approaches analyze complex biological data to predict drug-target interactions, drug sensitivity, and treatment response [20] [21]. The representation learning capability of DL models allows them to identify patterns in high-dimensional pharmacological data that escape traditional analysis methods, potentially accelerating the development of novel therapeutics for neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Diagram: DL workflow for synaptic analysis combining super-resolution microscopy with automated segmentation for quantifying neuronal structures.

Modeling Neural Computation

Beyond data analysis, DL serves as a theoretical framework for understanding neural computation. The hypothesis that biological neural systems optimize cost functions—similar to how DL models are trained—provides a unifying principle for relating neural activity to behavior [15] [16]. This perspective suggests that specialized brain systems may be optimized for specific computational problems, with cost functions that vary across brain regions and change throughout development [15].

Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) trained to perform cognitive tasks have been shown to develop neural dynamics that resemble activity patterns in the brain, providing insights into how neural circuits might implement cognitive functions [17]. This approach allows researchers to generate testable hypotheses about neural mechanisms that can be validated through experimental studies.

Future Directions and Implementation Challenges

Addressing Limitations and Ethical Considerations

Despite their advantages, DL approaches face several challenges in neuroscience applications:

Interpretability: The "black box" nature of DL models remains a concern, particularly for clinical applications [18]. Explainable AI (XAI) methods are being developed to address this limitation by making DL decisions more transparent and interpretable [21].

Data Requirements: DL models typically require large training datasets, which can be challenging for rare neurological conditions or expensive imaging modalities [18]. Transfer learning and data augmentation strategies are helping mitigate this constraint.

Computational Resources: Training complex DL models demands substantial computational resources, potentially limiting accessibility for some research groups. Cloud computing and optimized model architectures are gradually reducing these barriers.

Integration with Existing Knowledge: A key challenge is integrating DL models with established neurobiological knowledge. Approaches that incorporate anatomical constraints or prior biological knowledge represent a promising direction for future research.

Emerging Opportunities

The intersection of DL and neuroscience presents numerous opportunities for future advancement:

- Integration with other technologies: Combining DL with optogenetics, electrophysiology, and other neuroscience techniques promises more comprehensive understanding of brain function [18]

- Development of novel architectures: Graph neural networks and other specialized architectures may better model the complex network structure of the brain [18]

- Multi-modal data integration: DL approaches are particularly suited for integrating diverse data types (genomics, imaging, behavior) to develop more complete models of neural function

- Closed-loop systems: DL-powered brain-computer interfaces may enable new therapeutic approaches for neurological disorders [18]

Deep learning provides fundamental advantages over traditional machine learning for neuroscience research, primarily through its capacity for automated representation learning from complex neural data. The ability of DL models to discover patterns in high-dimensional neuroimaging data, identify distributed biomarkers, and model nonlinear neural dynamics represents a paradigm shift in how we analyze and interpret brain structure and function. As DL methodologies continue to evolve and integrate with established neuroscience techniques, they offer unprecedented opportunities to advance our understanding of neural systems and develop novel interventions for neurological and psychiatric disorders. For researchers and drug development professionals, embracing these approaches while addressing their limitations through appropriate validation and interpretation frameworks will be essential for translating these technical advantages into meaningful scientific and clinical advances.

The Critical Role of Large-Scale Neuroimaging Datasets (fMRI, sMRI, DTI, EEG) in Model Training

The integration of deep learning (DL) with neuroscience represents a paradigm shift in our ability to analyze brain structure and function. This synergy hinges critically on the availability of large-scale neuroimaging datasets that provide the foundational substrate for training complex computational models. Traditional machine learning approaches in neuroimaging have been largely constrained by assumptions of linearity and limited capacity to handle high-dimensional data [22]. Deep learning models, with their multi-layer architectures and capacity for hierarchical feature learning, overcome these limitations but require substantial amounts of data to realize their full potential [23]. The emergence of multimodal datasets that combine functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), structural MRI (sMRI), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), and electroencephalography (EEG) has created unprecedented opportunities for developing more comprehensive models of brain function and dysfunction [24] [8]. This technical guide examines the indispensable role of these datasets within the broader context of deep learning neuroscience research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with methodological frameworks and practical resources for leveraging these data resources.

The Expanding Landscape of Neuroimaging Datasets

The growth of large-scale, publicly available neuroimaging datasets has been exponential in recent years, directly paralleling the increased application of deep learning in neuroscience [25]. These datasets vary significantly in scale, modality, and specific application focus, but share the common characteristic of providing the necessary training data for data-hungry deep learning algorithms.

Table 1: Representative Large-Scale Neuroimaging Datasets for Deep Learning Applications

| Dataset Name | Modalities | Participants | Scan Sessions | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NOD (Natural Object Dataset) [24] | fMRI, MEG, EEG | 30 | Not specified | Object recognition in natural scenes |

| NATVIEW_EEGFMRI [26] | EEG, fMRI, Eye Tracking | Not specified | Not specified | Naturalistic viewing paradigm |

| SIMON MRI Dataset [27] | sMRI, rsfMRI, dMRI, ASL | 1 | 73 | Longitudinal multi-scanner reliability |

| MyConnectome [27] | sMRI, rsfMRI, task fMRI | 1 | 104 | Long-term neural phenotyping |

| HBN-SSI [27] | sMRI, rsfMRI, task fMRI, DKI | 13 | ~14 | Inter-individual differences |

| Kirby Weekly [27] | sMRI, rsfMRI | 1 | 158 | Resting-state fMRI reproducibility |

| Travelling Human Phantoms [27] | MRI, dMRI, rsfMRI | 4 | 3-9 across 5 scanners | Multi-center standardization |

| Decoded Neurofeedback Project [27] | MRI, rsfMRI | 9 | 12 sites | Cross-site harmonization |

The data presented in Table 1 illustrates several important trends in neuroimaging data collection. First, there is a strategic balance between large-N studies (dozens to hundreds of participants) that capture population diversity and deep-sampling studies (extensive repeated measurements of few individuals) that enable detailed longitudinal analysis [27]. Second, there is a clear movement toward multimodal integration, with datasets increasingly combining structural, functional, and diffusion imaging, often supplemented with electrophysiological data like EEG [24] [8].

The NOD dataset exemplifies this multimodal approach, specifically addressing the limitation that most existing large-scale neuroimaging datasets with naturalistic stimuli primarily relied on fMRI alone [24]. By incorporating MEG and EEG data from the same participants viewing the same naturalistic images, NOD enables examination of brain activity with both high spatial resolution (via fMRI) and high temporal resolution (via MEG/EEG) [24].

Bibliometric Trends in Deep Learning for Neuroscience

Quantitative analysis of publication trends confirms the growing importance of this interdisciplinary field. A comprehensive bibliometric analysis covering 2012-2023 identified exponential growth in deep learning applications in neuroscience, with annual publications increasing from fewer than 3 per year during 2012-2015 to approximately 100 annually by 2021-2023 [25] [28]. This represents a 30-fold increase in research output over the decade, indicating rapid maturation of the field from foundational exploration to specialized application.

Table 2: Evolution of Research Focus in Deep Learning for Neuroscience (2012-2023)

| Time Period | Phase Characterization | Key Research Foci | Dominant Methodologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012-2015 | Foundational Phase | Establishing core frameworks | Basic neural networks, foundational algorithms |

| 2016-2019 | Early Application | Neurological classification, basic feature extraction | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) |

| 2020-2023 | Specialization & Maturation | Multimodal integration, biological plausibility | Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs), advanced architectures |

The thematic evolution reveals a distinct shift from foundational methodologies toward more specialized approaches, with increasing focus on EEG analysis and convolutional neural networks, reflecting the growing importance of processing complex temporal and spatial patterns in neuroimaging data [25].

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Frameworks

The utility of large-scale neuroimaging datasets is fully realized only when paired with robust experimental protocols and processing pipelines. Standardized methodologies ensure reproducibility and enable meaningful comparisons across studies and datasets.

Multimodal Data Acquisition Protocols

The NATVIEW_EEGFMRI project provides a representative framework for simultaneous multimodal data collection [26]. Their protocol includes:

Simultaneous EEG-fMRI Acquisition: Data collection using integrated systems that capture electrophysiological and hemodynamic signals concurrently, requiring careful artifact removal and synchronization procedures.

Naturalistic Stimulus Presentation: Implementation of Psychtoolbox-3 for presenting video stimuli or flickering checkerboard tasks, with precise timing control and integration with eye tracking [26].

Complementary Data Streams: Collection of EyeLink eye tracking data and Biopac respiratory data to provide additional contextual information for interpreting primary neuroimaging signals [26].

BIDS Formatting: Organization of all data according to the Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) specification to ensure standardization and interoperability [26].

Preprocessing Pipelines for Multimodal Integration

Effective preprocessing is essential for preparing raw neuroimaging data for deep learning applications. The NATVIEW project provides open-source preprocessing scripts that exemplify current best practices:

EEG Preprocessing Pipeline [26]:

- Gradient artifact removal for data collected inside MRI scanners

- QRS detection and pulse artifact removal

- Multiple filtering steps for data cleaning

- Electrode montage configuration specific to cap design

Structural and Functional MRI Preprocessing:

- Standardized spatial normalization to template space

- Motion correction and slice timing correction (fMRI)

- Quality control metrics for data exclusion criteria

Eye Tracking Preprocessing [26]:

- Conversion from EyeLink EDF format to BIDS specification

- Blink detection algorithms with linear interpolation of missing data

- Calculation of percentage of samples missing and off-screen gaze

Deep Learning Approaches for Neuroimaging Data

The unique characteristics of neuroimaging data have driven the development and adaptation of specialized deep learning architectures that can leverage the spatial, temporal, and multimodal nature of these datasets.

Architectural Innovations for Neuroimaging Data

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have proven particularly effective for analyzing structural and functional MRI data, leveraging their ability to extract hierarchical spatial features [29] [23]. In neuroimaging contexts, CNNs combine local patterns of spatial activation to find progressively complex patterns with layer depth, effectively learning brain representations without manual feature engineering [29].

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), particularly Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, are well-suited for time-series neuroimaging data such as EEG and fMRI BOLD signals [29] [8]. These networks employ previous knowledge of function outputs toward future prediction, similar to how the brain uses stored knowledge to influence perception while also using perception to update stored knowledge [29].

Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) represent a more biologically plausible approach to processing neuroimaging data [8]. Unlike traditional deep learning models that use continuous mathematical functions, SNNs transmit information through discrete spike events over time, providing a temporal dimension that is absent in most deep learning models [8]. This makes SNNs particularly effective for capturing dynamic brain processes and offers potential for low-power neuromorphic hardware implementation [8].

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Deep Learning Architectures for Neuroimaging

| Architecture | Strengths | Limitations | Ideal Neuroimaging Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | Excellent spatial feature extraction, hierarchical representation learning | Limited temporal processing capability | sMRI classification, fMRI spatial pattern recognition |

| Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs/LSTMs) | Effective temporal sequence modeling, memory of previous states | Computationally intensive, gradient issues in very long sequences | EEG signal analysis, resting-state fMRI dynamics |

| Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) | Biological plausibility, energy efficiency, inherent temporal processing | Complex training procedures, limited tooling | Multimodal temporal integration, real-time BCI applications |

| Hybrid Architectures | Combines strengths of multiple approaches, flexible for multimodal data | Increased complexity, challenging optimization | Integrated EEG-fMRI analysis, cross-modal prediction |

Addressing Key Challenges in Neuroimaging DL

Several significant challenges persist in applying deep learning to neuroimaging data, each requiring specialized approaches:

High Dimensionality and Small Sample Sizes: Neuroimaging datasets often feature extremely high dimensionality (thousands to millions of features) with relatively small sample sizes (dozens to hundreds of participants). This "curse of dimensionality" creates significant overfitting risks [29]. Two emerging approaches show particular promise:

Transfer Learning: This method applies knowledge gained while solving one problem to a different but related problem [29]. In neuroimaging, this often involves using a pre-trained network as a feature extractor or fine-tuning a pretrained network on target domain data. Domain adaptation, a variant of transfer learning, is particularly valuable for addressing site-specific effects when combining datasets from multiple imaging centers [29].

Data Augmentation (via Mixup): This self-supervised learning technique creates "virtual" instances by combining existing data samples, effectively expanding training datasets and improving model generalization [29].

Model Interpretability ("Black Box" Problem): The complexity of deep learning models often makes it difficult to understand what features drive their decisions. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) methods address this by revealing what features (and combinations) deep learners use to make decisions [29]. These techniques are particularly important for clinical applications where understanding the biological basis of classifications is essential.

Successful implementation of deep learning approaches for neuroimaging requires familiarity with a suite of specialized tools and resources. The following table summarizes key components of the modern neuroimaging DL research toolkit.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function/Purpose | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Repositories | NOD [24], NATVIEW_EEGFMRI [26], OpenNeuro | Public data access, standardized formatting | Model training, benchmark development, transfer learning |

| Preprocessing Tools | EEGLAB + FMRIB Plugin [26], FSL, SPM, AFNI | Artifact removal, normalization, quality control | Data cleaning, feature extraction, modality synchronization |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Keras | Model implementation, training, evaluation | Architecture development, hyperparameter optimization |

| Specialized Architectures | Spiking Neural Network Libraries (e.g., Nengo, BindsNet) [8] | Biologically plausible processing | Temporal dynamics modeling, neuromorphic implementation |

| Analysis & Visualization | Bibliometrix [25], Connectome Workbench, Nilearn | Literature analysis, result interpretation, visualization | Trend analysis, feature visualization, connectivity mapping |

| Computational Resources | High-Performance Computing (HPC), GPU Clusters, Neuromorphic Hardware [8] | Processing large datasets, training complex models | Large-scale model training, hyperparameter search |

Large-scale neuroimaging datasets represent a foundational resource that enables the application of deep learning approaches to advance our understanding of brain function and dysfunction. The synergistic relationship between dataset availability and methodological innovation has created a virtuous cycle of progress in the field. As dataset scale and multimodality continue to increase, and as more biologically plausible architectures like SNNs mature, we can anticipate accelerated progress in both basic neuroscience and clinical applications. For drug development professionals, these advances offer promising pathways toward more precise biomarkers, better patient stratification, and more sensitive measures of treatment response. The continued strategic investment in both data resources and analytical methods will be essential for realizing the full potential of deep learning in neuroscience.

Advanced Architectures and Real-World Applications in Neuroimaging and Biomarker Discovery

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for Structural and Functional MRI Analysis

The integration of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) into neuroimaging represents a paradigm shift within deep learning neural network neuroscience research. These models provide powerful tools for analyzing the complex, high-dimensional data generated by structural and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (sMRI/fMRI). CNNs automatically learn hierarchical features from brain imaging data, enabling unprecedented accuracy in tasks ranging from disease classification to brain decoding. This technical guide examines core architectures, methodologies, and performance of CNNs applied to sMRI and fMRI, contextualized within the broader pursuit of understanding brain function and dysfunction through computational models.

CNN Architectures for Neuroimaging Data

Core Architectural Principles

CNNs leverage several core principles to effectively process neuroimaging data. Their architecture is fundamentally built on hierarchical feature learning, where early layers detect simple patterns (e.g., edges, textures) and deeper layers combine these into complex, abstract representations relevant to brain structure and function. The spatial invariance conferred by convolutional operations and pooling layers allows these models to recognize patterns regardless of their specific location in the brain, which is crucial for handling anatomical and functional variability across individuals. Furthermore, the parameter sharing characteristic of convolutional filters drastically reduces the number of learnable parameters compared to fully-connected networks, mitigating overfitting on typically limited neuroimaging datasets [23].

Specialized CNN Variants

Standard CNN architectures have been adapted and extended to address specific challenges in neuroimaging:

Graph CNNs (GCNs): These models operate on graph-structured data, where brain regions are represented as nodes and their structural or functional connections as edges. This framework naturally incorporates connectomic information, allowing the model to learn from both regional features and network topology. GCNs have shown particular promise in analyzing functional connectivity networks derived from fMRI [30].

Hybrid CNN-RNN Models: For fMRI data, which contains rich temporal dynamics, CNNs are often combined with Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks or Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs). In these architectures, CNNs extract spatial features from individual volumetric timepoints, while the RNN components model temporal dependencies across sequences, capturing the evolving patterns of brain activity [31].

3D Convolutional Networks: Unlike standard 2D CNNs designed for images, 3D CNNs utilize volumetric kernels that operate across the full three-dimensional extent of brain scans. This allows them to capture anatomical contextual information across all spatial dimensions simultaneously, making them particularly suited for sMRI analysis where the 3D structure is inherently meaningful [32].

CNN Applications in Structural MRI Analysis

Structural MRI provides detailed anatomical information about the brain's architecture. CNNs have demonstrated remarkable proficiency in analyzing these data for diagnostic and research purposes.

Disease Classification and Detection

CNNs achieve high performance in differentiating neurological and psychiatric conditions based on sMRI. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis quantified this performance across multiple diagnostic tasks, as summarized in Table 1 [32].

Table 1: Diagnostic Performance of CNN Models on Structural MRI Data

| Diagnostic Classification Task | Pooled Sensitivity | Pooled Specificity | Number of Studies | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's Disease (AD) vs. Normal Cognition (NC) | 0.92 | 0.91 | 21 | 16,139 |

| Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) vs. Normal Cognition (NC) | 0.74 | 0.79 | 21 | 16,139 |

| Alzheimer's Disease (AD) vs. Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) | 0.73 | 0.79 | 21 | 16,139 |

| Progressive MCI (pMCI) vs. Stable MCI (sMCI) | 0.69 | 0.81 | 21 | 16,139 |

The meta-analysis concluded that CNN algorithms demonstrated promising diagnostic performance, with the highest accuracy observed in distinguishing AD from NC. Performance was moderate for distinguishing MCI from NC and AD from MCI, and most challenging for predicting MCI progression (pMCI vs. sMCI), reflecting the subtle nature of early pathological changes [32].

Image Processing and Enhancement

Beyond classification, CNNs are extensively used to improve sMRI data quality and extract finer anatomical details:

Image Denoising and Super-resolution: CNN-based denoising autoencoders learn to map noisy MR inputs to clean outputs, improving signal-to-noise ratio. Similarly, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) can perform super-resolution, generating high-resolution images from low-resolution acquisitions, which can reduce scan times without sacrificing anatomical detail [33].

Brain Extraction and Segmentation: CNNs like FastSurfer provide rapid and accurate whole-brain segmentation into distinct anatomical regions. These models have demonstrated lower numerical uncertainty and higher agreement with manual segmentation compared to traditional pipelines like FreeSurfer, indicating superior reliability for morphometric analyses [34].

CNN Applications in Functional MRI Analysis

Functional MRI captures brain activity by measuring blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signals. CNNs analyze both the spatial patterns and temporal dynamics of these signals.

Modeling Brain Activity and Connectivity

CNNs decode cognitive states and map functional networks from fMRI data. Hybrid architectures that combine CNNs with RNNs or attention mechanisms are particularly effective. For instance, one proposed framework uses a CNN to extract spatial features from fMRI volumes and a GRU network to model temporal dynamics of functional connectivity. The integration of a Dynamic Cross-Modality Attention Module helps prioritize diagnostically relevant spatio-temporal features, achieving a reported classification accuracy of 96.79% on certain diagnostic tasks using the Human Connectome Project dataset [31].

Decoding MEG and EEG Signals

While not fMRI, the analysis of magnetoencephalography (MEG) and electroencephalography (EEG) signals presents similar challenges and solutions. A Graph-based LSTM-CNN (GLCNet) was developed to classify motor and cognitive imagery tasks from MEG data. This architecture integrates a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) to model functional topology, a spatial CNN to extract local features, and an LSTM to capture long-term temporal dependencies. This model achieved accuracies of 78.65% and 65.8% for two-class and four-class classifications, respectively, on an MEG-BCI dataset, outperforming several benchmark algorithms [30].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Implementing CNNs for neuroimaging analysis requires careful experimental design. Below is a generalized protocol for a CNN-based classification study using sMRI data.

Protocol: sMRI-based Disease Classification

Objective: To train and validate a CNN model for differentiating Alzheimer's Disease (AD) patients from cognitively normal (CN) controls using T1-weighted structural MRI scans.

1. Data Preprocessing

- Data Sourcing: Obtain T1-weighted MRI scans from public datasets like ADNI, OASIS, or the Southwest University Adult Lifespan Dataset (SALD) [35].

- Preprocessing Pipeline:

- Reorientation: Standardize image orientation to a common template (e.g., MNI).

- Bias Field Correction: Correct for intensity inhomogeneities using tools like N4ITK.

- Skull Stripping: Remove non-brain tissue using a model like FastSurfer [34].

- Registration: Non-linearly register all images to a standard space to ensure voxel-wise correspondence.

- Intensity Normalization: Scale voxel intensities to a standard range (e.g., 0-1).

2. Data Partitioning

- Split the dataset at the subject level into independent training (e.g., 70%), validation (e.g., 15%), and hold-out test (e.g., 15%) sets. Ensure no subject appears in more than one set.

3. Model Architecture & Training

- Architecture Selection: Implement a 3D CNN architecture (e.g., 3D-ResNet) to capture volumetric context.

- Optimization: Use the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 1e-4 and a binary cross-entropy loss function.

- Regularization: Apply heavy data augmentation (random flipping, rotation, elastic deformation) and use dropout (rate=0.5) and L2 weight decay to prevent overfitting.

- Training Loop: Train for a fixed number of epochs (e.g., 200), saving the model weights that achieve the highest accuracy on the validation set.

4. Model Evaluation

- Performance Metrics: Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set using sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC).

- Interpretability Analysis: Generate saliency maps (e.g., Grad-CAM) to visualize which brain regions most influenced the model's decision, linking findings to known neuropathology (e.g., medial temporal lobe atrophy in AD) [36].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this experimental pipeline:

Performance Benchmarking and Reliability

Understanding the performance and reliability of CNN models is crucial for their translation into research and clinical environments.

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks of CNN Models Across Neuroimaging Modalities

| Modality | Task | Model Architecture | Reported Performance | Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sMRI | AD vs NC Classification | 3D CNN | Sensitivity: 0.92, Specificity: 0.91 [32] | Multi-study Meta-analysis |

| sMRI | Whole-Brain Segmentation | FastSurfer (CNN) | Sørensen-Dice: 0.99 [34] | Internal Dataset (n=35) |

| fMRI/MEG | MI/CI Task Classification | GLCNet (GCN-LSTM-CNN) | Accuracy: 78.65% (2-class) [30] | MEG-BCI Dataset |

| Multimodal (sMRI+fMRI) | Brain Disorder Classification | Hybrid CNN-GRU-Attention | Accuracy: 96.79% [31] | Human Connectome Project |

Numerical Uncertainty and Reproducibility

The reliability of CNN-based neuroimaging tools is a critical concern. A study assessing the numerical uncertainty of CNNs for structural MRI analysis found that models like SynthMorph (for registration) and FastSurfer (for segmentation) produced substantially lower numerical uncertainty compared to traditional pipelines like FreeSurfer. For instance, in non-linear registration, the CNN model retained approximately 19 significant bits versus 13 for FreeSurfer, suggesting better reproducibility of CNN results across different computational environments [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of CNN projects in neuroimaging relies on a suite of software, data, and hardware resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CNN-based Neuroimaging

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Libraries | TensorFlow, PyTorch, FastSurfer, DeepLabCut [23] | Provides the foundational framework for developing, training, and deploying CNN models. |

| Neuroimaging Datasets | ADNI, OASIS, Human Connectome Project (HCP), SALD [35] [31] | Offers large-scale, well-characterized neuroimaging data for training and benchmarking models. |

| Data Preprocessing Tools | FSL, FreeSurfer, SPM, ANTs, PyDeface [35] | Standardizes raw MRI data through steps like normalization, skull-stripping, and registration. |

| Explainability Tools | Saliency Maps, Grad-CAM, Attention Mechanisms [36] [31] | Provides insight into model decisions, highlighting influential brain regions for interpretability. |

| Computational Hardware | High-End GPUs (NVIDIA), FPGA Accelerators [37] | Accelerates the computationally intensive training and inference processes for deep CNN models. |

| 4-(o-Methoxythiobenzoyl)morpholine | 4-(o-Methoxythiobenzoyl)morpholine | 4-(o-Methoxythiobenzoyl)morpholine for research. Explore the applications of this morpholine-based reagent in medicinal chemistry. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| N-2-adamantyl-3,5-dimethylbenzamide | N-2-adamantyl-3,5-dimethylbenzamide, MF:C19H25NO, MW:283.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrated Analysis and Future Directions

The integration of CNNs into computational neuroscience represents more than a technical advancement; it is a paradigm shift toward data-driven, model-based understanding of brain function and pathology. The high performance of CNNs in diagnostic classification tasks (Table 1) demonstrates their potential as supportive diagnostic tools. Furthermore, their superior numerical reliability over traditional methods suggests they could yield more reproducible findings in research settings [34]. The move towards multimodal integration—combining sMRI, fMRI, and other data types within hybrid CNN architectures—promises a more holistic view of brain structure and function [31].

A critical future direction is the development of explainable AI (XAI) for neuroimaging CNNs. Techniques like saliency maps and attention mechanisms are essential for translating a model's "black box" predictions into biologically interpretable insights, fostering trust and enabling the generation of novel, testable neuroscientific hypotheses [36]. As these models become more interpretable, efficient, and integrated, they will solidify their role as an indispensable component of modern neuroscience research, bridging the gap between complex data and actionable understanding of the brain.

Recurrent and Spiking Neural Networks for Temporal Brain Data (EEG, Time-Series fMRI)

The human brain is a dynamic system, where information is processed through intricate patterns of neural activity unfolding over time. Electroencephalography (EEG) and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) provide complementary windows into these temporal processes: EEG captures millisecond-range electrical fluctuations with high temporal resolution, while fMRI tracks slower hemodynamic changes related to neural activity with high spatial precision [38] [39]. Traditional artificial neural networks (ANNs) have demonstrated significant capabilities in analyzing neuroimaging data; however, they face fundamental limitations in capturing the rich temporal dynamics and event-driven characteristics inherent to brain function. Their continuous, rate-based operation and limited temporal memory struggle to model the precise spike-based communication observed in biological neural systems [8] [7].

Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) and specialized recurrent architectures represent a paradigm shift in temporal brain data analysis. As the third generation of neural networks, SNNs closely mimic the brain's operational mechanisms by processing information through discrete, event-driven spikes, enabling more biologically plausible and computationally efficient modeling of neural processes [38] [40]. The event-driven nature of SNNs allows for potentially lower power consumption and better alignment with the temporal characteristics of brain signals, making them particularly suitable for real-time applications such as brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) and neurofeedback systems [38]. For researchers and drug development professionals, these advanced neural networks offer new avenues for identifying subtle temporal biomarkers in neurological and psychiatric disorders, potentially accelerating therapeutic discovery and personalized treatment approaches.

Theoretical Foundations of SNNs and RSNNs

From Artificial to Spiking Neural Networks

Traditional artificial neural networks (ANNs) operate on continuous-valued activations, propagating information through layers via matrix multiplications and nonlinear transformations. While effective for many static pattern recognition tasks, this framework differs significantly from biological neural processing. In contrast, Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) incorporate temporal dynamics into their core computational model, where information is encoded in the timing and sequences of discrete spike events [38] [8]. This fundamental difference enables SNNs to process temporal information more efficiently and provides a more biologically realistic model of neural computation.

The leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) model serves as a fundamental building block for most SNN architectures. This neuron model mimics key properties of biological neurons through its membrane dynamics, which can be described by the following equation:

[ \taum \frac{dv}{dt} = a + RmI - v ]

where (\taum) represents the membrane time constant, (v) is the membrane potential, (a) is the resting potential, (Rm) is the membrane resistance, and (I) denotes the input current from presynaptic neurons [40]. When the membrane potential (v) crosses a specific threshold (v{\text{threshold}}), the neuron emits a spike and resets its potential to (v{\text{reset}}), entering a brief refractory period. This behavior allows SNNs to naturally encode temporal information in spike timing patterns, closely resembling the communication mechanisms observed in biological neural systems [38] [7].

Recurrent Spiking Neural Networks

Recurrent Spiking Neural Networks (RSNNs) incorporate feedback connections that enable temporal processing and memory retention across time steps. These networks typically consist of three main layers: (1) an input encoding layer that transforms raw data into spike trains, (2) a recurrent spiking layer with excitatory and inhibitory neurons distributed in biologically plausible ratios (often 4:1), and (3) an output decoding layer that interprets the spatiotemporal spike patterns for classification or regression tasks [40]. The recurrent connections allow for rich temporal dynamics and context-dependent processing, making RSNNs particularly suitable for modeling complex brain signals such as EEG and fMRI time series.

Table 1: Comparison of Neural Network Architectures for Temporal Brain Data

| Architecture | Temporal Processing | Biological Plausibility | Energy Efficiency | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional ANNs | Limited temporal memory, struggles with long sequences | Low, continuous activations | Moderate to high | Proven performance on static patterns |

| RNNs/LSTMs | Better sequential processing, but may suffer from vanishing gradients | Moderate, simplified neuron models | Moderate | Effective for short to medium sequences |