Brain-Computer Interface Fundamentals: A Technical Deep Dive into Working Principles and Signal Acquisition

This article provides a comprehensive technical overview of Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technology, with a focused examination of its core working principles and signal acquisition methodologies.

Brain-Computer Interface Fundamentals: A Technical Deep Dive into Working Principles and Signal Acquisition

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive technical overview of Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technology, with a focused examination of its core working principles and signal acquisition methodologies. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content explores the foundational neuroscience behind BCIs, details the latest non-invasive, minimally invasive, and invasive signal acquisition technologies, and analyzes their respective performance benchmarks. It further addresses critical challenges in signal quality and system optimization, and offers a comparative validation of emerging technologies and their trajectories. The goal is to equip a technical audience with a clear understanding of the current state and future potential of BCI systems in biomedical research and clinical applications.

The Neuroscience and Core Architecture of Brain-Computer Interfaces

A Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) is a system that establishes a direct communication pathway between the human brain and an external device, translating thought into action independent of the brain's normal output pathways of peripheral nerves and muscles [1] [2]. This technology, which has evolved from a laboratory curiosity to a burgeoning neurotechnology industry as of 2025, enables users to control computers, robotic limbs, or communication aids through the decoding of their brain signals alone [1]. The core principle of any BCI is to acquire brain activity, decode the user's intent from this activity, and translate it into commands for an external device, creating a closed-loop system that can restore, replace, enhance, supplement, or improve natural central nervous system output [1] [3]. This in-depth technical guide outlines the fundamental working principles and signal acquisition research that underpin modern BCI systems, providing researchers and scientists with a foundational understanding of this transformative field.

Historical Context and Evolution

The conceptual and practical foundations of BCI technology were laid through pivotal milestones over the past century. The journey began in 1924 when Hans Berger recorded the first human electroencephalogram (EEG) from a young patient with cranial defects, using clay electrodes, thereby marking the inception of a scientific method for monitoring human brain activity [4]. Decades later, the term "brain-computer interface" was first formally articulated by Jacques Vidal in 1973, whose work is widely recognized as the foundational definition of a BCI as a device utilizing EEG signals for communication [4] [2]. At the inaugural international BCI conference in 1999, the technology was formally delineated as “a communication system that does not rely on the brain's normal output pathways of peripheral nerves and muscles” [4]. This definition was refined in 2012 to describe BCI as a “new non-muscular channel” for interaction, and again in 2021 with the introduction of the concept of a generalized BCI, characterized as “any system with direct interaction between a brain and an external device” [4].

Pioneering work has been instrumental in transitioning BCIs from concept to reality. In a notable 2014 self-experiment, neurologist Dr. Phil Kennedy paid to have electrodes implanted in his own brain after U.S. regulators halted his research. Despite post-operative complications that left him temporarily mute, his experiments proved that imagined speech could be captured and decoded from neural signals, providing a crucial proof of concept for giving voice to the voiceless [1]. As of mid-2025, BCI technology is in a phase of rapid translation from laboratory experiments to clinical trials, driven by numerous neurotech startups and research groups, standing roughly where gene therapies were in the 2010s—on the cusp of graduating from experimental status to regulated clinical use [1].

Core Working Principles of BCI Systems

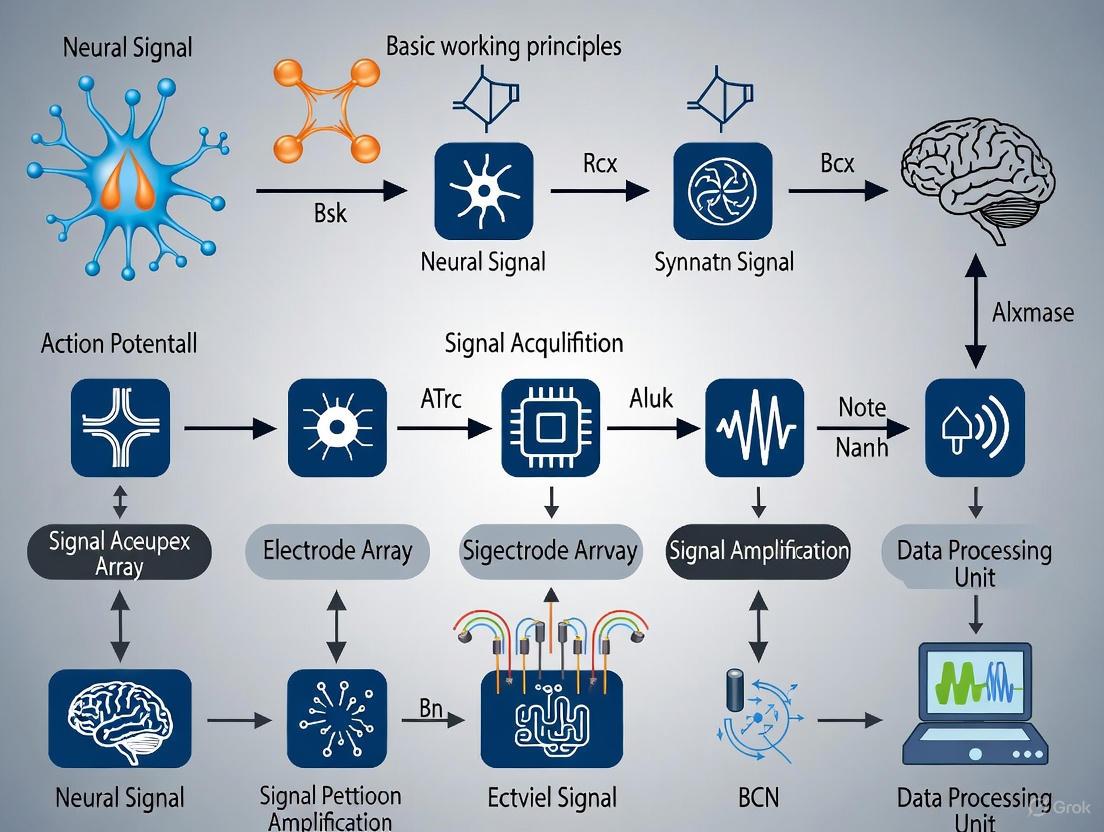

The efficacy of a BCI system hinges on a structured, closed-loop pipeline that converts brain activity into functional outputs. This process involves four fundamental components that work in sequence: signal acquisition, processing (which includes decoding and translation), output, and feedback [1] [4] [2]. The following diagram illustrates this core BCI workflow and the interdependence of its components.

Diagram 1: The core closed-loop workflow of a BCI system.

Signal Acquisition

The process begins with signal acquisition, where electrodes or sensors pick up electrophysiological signals representing the brain's neurophysiological states [2]. The specific technologies and methodologies for acquisition are diverse and are discussed in detail in Section 4.

Processing and Decoding

The acquired raw signals are typically weak and contaminated with noise from various sources, including other biological signals (e.g., eye blinks, muscle activity) and environmental interference. Therefore, the processing stage involves multiple sub-stages [2] [5]:

- Preprocessing: The raw signals are filtered to remove artifacts, noise, and unwanted interferences, and are often amplified and digitized. This is a crucial step to ensure the data is clean and suitable for subsequent analysis [5].

- Feature Extraction: Critical electrophysiological features that define brain activities and encode the user's intent are extracted from the preprocessed signals. These features can be in the time-domain (e.g., amplitude or latency of event-related potentials like the P300) or frequency-domain (e.g., power spectra of sensorimotor rhythms) [2].

- Feature Classification and Translation: Using machine learning and classification methods (e.g., Support Vector Machines, Deep Learning), the system recognizes patterns in the extracted features that correspond to desired actions [4] [2]. The classified patterns are then translated into actual commands to operate an external device [2].

Output and Feedback

The translated commands are sent to an output device or application, which executes the user's intended action. This effector can be a robotic arm, a wheelchair, a computer cursor for letter selection, or a text-to-speech synthesizer [2] [3]. Finally, the feedback loop is critical for learning and accuracy. The user sees or hears the result of the action (e.g., a cursor moving or a letter being selected), which allows them to adjust their mental strategy accordingly, creating a closed-loop system that fosters adaptive learning and improved control [1] [4].

Signal Acquisition Technologies: A Dimensional Framework

The signal acquisition module bears the critical responsibility for the detection and recording of cerebral signals and is thus the most determinant component of BCI system performance [4]. A comprehensive understanding requires a dual-perspective analysis. A 2025 review by Sun et al. proposes a two-dimensional framework that synthesizes clinical (surgical) and engineering (detection) viewpoints, offering a holistic classification of BCI signal acquisition techniques [4] [6].

The Surgery Dimension: Invasiveness of Procedures

This dimension, classified from a clinician's perspective, refers to the invasiveness of the surgical procedure and its associated anatomical trauma [4]. The following table summarizes the three levels of this dimension.

Table 1: The Surgery Dimension of BCI Signal Acquisition

| Category | Definition | Surgical Trauma & Ethical Considerations | Clinical Oversight Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Invasive | Surgical actions for signal procurement do not induce anatomically discernible trauma [4]. | Minimal to none; lowest ethical intensity [4]. | Typically obviates the need for continuous clinical oversight [4]. |

| Minimally Invasive | Incurs anatomical trauma, but spares the brain tissue from impact [4]. | Moderate trauma; heightened ethical considerations compared to non-invasive [4]. | Necessitates the engagement of neurology or neurosurgery experts [4]. |

| Invasive | Causes anatomically discernible trauma at the micron scale or larger, specifically affecting the brain tissue [4]. | Highest degree of trauma; most intense ethical considerations [4]. | Virtually all methodologies require the direct involvement of experienced neurosurgeons [4]. |

The Detection Dimension: Operating Location of Sensors

This dimension, approached from an engineering perspective, is defined by the sensor's operating location and is directly linked to the theoretical upper limit of signal quality and biocompatibility risk [4]. The following table outlines the three levels of this dimension.

Table 2: The Detection Dimension of BCI Signal Acquisition

| Category | Definition & Sensor Location | Theoretical Signal Quality | Example Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Implantation | Signal is acquired through a sensor on the surface of the body [4]. | Lowest quality; akin to "listening to a chorus from outside the building" [4]. | Electroencephalography (EEG), Magnetoencephalography (MEG), functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) [3]. |

| Intervention | Sensor leverages naturally existing cavities (e.g., blood vessels) without harming original tissue integrity [4]. | Intermediate quality; a balance between signal fidelity and invasiveness [4]. | Stentrode (Synchron) [1]. |

| Implantation | Signal is collected from a sensor implanted within human tissue [4]. | Highest theoretical signal quality due to proximity to neural signal source [4]. | Microelectrode Arrays (e.g., Utah Array, Neuralink), Electrocorticography (ECoG) grids [1] [2]. |

The interplay between these two dimensions creates a comprehensive framework for classifying any BCI signal acquisition technology. The following diagram visualizes this two-dimensional framework, placing key technologies within the landscape defined by the surgery and detection dimensions.

Diagram 2: A two-dimensional framework for BCI signal acquisition technologies.

Modern BCI Platforms and Experimental Protocols

The theoretical principles of BCI are materializing through advanced platforms developed by both commercial entities and research institutions. These platforms serve as practical testbeds for the signal acquisition frameworks described above and provide tangible protocols for research and development.

Key Commercial and Research Platforms

As of 2025, several key players are leading the transition of BCI technology from lab to clinic through human trials [1]:

- Neuralink: Perhaps the most publicized BCI company, Neuralink is developing an ultra-high-bandwidth implantable chip with thousands of micro-electrodes threaded into the cortex by a robotic surgeon. The coin-sized implant aims to record from more neurons than any prior device. As of June 2025, the company reported that five individuals with severe paralysis are using Neuralink to control digital and physical devices with their thoughts [1].

- Synchron: In contrast to Neuralink’s open-brain surgery, Synchron’s Stentrode uses a minimally invasive, endovascular approach. The device is delivered via blood vessels (the jugular vein) and lodged in the motor cortex's draining vein, where it records brain signals through the vessel wall. Human trials have allowed participants with paralysis to control a computer for texting using thought alone [1].

- Precision Neuroscience: Co-founded by a Neuralink alumnus, Precision is developing an ultra-thin electrode array (Layer 7) designed to be placed on the cortical surface through a minimally invasive approach. Their "brain film" conforms to the brain's surface without piercing neural tissue, representing a compromise between non-invasive ease and invasive signal quality. In April 2025, Precision’s device received FDA 510(k) clearance for commercial use with implantation durations of up to 30 days [1].

- Paradromics: This company specializes in high-channel-count implants for ultra-fast data transmission. Its Connexus BCI uses a modular array with 421 electrodes and an integrated wireless transmitter. In June 2025, a University of Michigan team partnered with Paradromics to perform the first-in-human recording with the device during an epilepsy surgery. A full clinical trial focused on restoring speech is planned for late 2025 [1].

- Blackrock Neurotech: A long-time supplier of neural electrode arrays for academic research (notably the Utah array), Blackrock is now developing new electrode technology like Neuralace, a flexible lattice designed for less invasive cortical coverage and reduced scarring over time [1].

A Generalized Experimental Protocol for BCI Research

For researchers aiming to conduct BCI experiments, particularly in neurorehabilitation or communication, the following protocol outlines a generalized methodology derived from current practices and challenges [3] [5].

Participant Selection and Preparation:

- Cohort: Recruit participants based on the target application (e.g., patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), spinal cord injury, or stroke for assistive technology; healthy controls for fundamental studies). Be mindful of the phenomenon of "BCI inefficiency," where 10-30% of users struggle to achieve control, often linked to individual variations in motor imagery capability [3].

- Ethical and Clinical Safeguards: For any protocol involving invasive or minimally invasive technologies, secure full regulatory (e.g., FDA) and institutional review board (IRB) approvals. Ensure the direct involvement of experienced neurosurgeons for invasive procedures [1] [4].

- Task Instruction: Train participants on the required mental strategy. This is typically either motor imagery (kinesthetic, focusing on the feeling of movement, is more effective than visual) or actual movement attempts. The quality of mental imagery significantly impacts the detectability of neural signals [3].

Signal Acquisition Setup:

- Technology Selection: Choose the acquisition technology based on the trade-off between required signal fidelity and acceptable invasiveness (see Section 4). Non-invasive EEG is common for initial studies, while invasive microelectrode arrays are used for high-bandwidth applications like speech decoding [1] [4].

- Calibration: Fit the sensor (e.g., EEG cap, implant) according to the manufacturer's and safety protocols. Record a baseline of brain activity.

Data Acquisition and Real-Time Processing:

- Paradigm Presentation: Present the user with a cue to perform the mental task (e.g., imagine moving their right hand). The timing and nature of these cues define the BCI paradigm (e.g., P300, Steady-State Visually Evoked Potential (SSVEP), sensorimotor rhythms) [7].

- Closed-Loop Operation: Run the core BCI workflow in real-time:

Output and Feedback Delivery:

- Effector Activation: Execute the command on the output device (e.g., move a robotic arm, select a letter on a screen, trigger functional electrical stimulation (FES) to move a paralyzed limb) [3].

- Feedback to User: Provide immediate, intuitive feedback (visual, auditory, or tactile) to the user about the system's action. This feedback is critical for the user to learn and adapt their mental strategy to improve control, thereby closing the loop [1] [3].

Post-Hoc Analysis and Validation:

- Performance Metrics: Quantify BCI performance using metrics such as information transfer rate (ITR), classification accuracy, and latency [2].

- Clinical Outcomes: For neurorehabilitation studies, assess functional improvements using standardized clinical scales for motor or communication function [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for BCI Research

| Item | Function in BCI Research |

|---|---|

| Electrodes (Ag/AgCl, Gold, Microelectrodes) | Sensors for acquiring electrophysiological signals. Material and design (e.g., scalp, stent, cortical array) vary with the acquisition technology [1] [4]. |

| Electrolyte Gel | Ensures stable electrical conductivity and reduces impedance between the scalp and electrodes in non-invasive EEG systems [3]. |

| Signal Amplifier and Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC) | Amplifies microvolt-level brain signals and converts them from analog to digital form for subsequent processing by a computer [2]. |

| Preprocessing Software (e.g., for ICA, Filtering) | Software tools for performing critical preprocessing steps like Independent Component Analysis (ICA) to remove ocular or muscular artifacts, and band-pass filtering to isolate relevant frequency bands [4] [3]. |

| Machine Learning Libraries (e.g., Scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch) | Libraries containing algorithms for feature extraction, classification, and translation, which are central to the decoding of the user's intent from brain signals [4] [2]. |

| Robotic Arm / Computer Cursor / FES Device | Common effector devices that serve as the output of the BCI system, providing tangible feedback and functional utility [2] [3]. |

The field of brain-computer interfaces has evolved from a foundational concept into a dynamic, interdisciplinary domain poised to revolutionize human-machine interaction, particularly in healthcare. The core working principle of a BCI rests on a closed-loop pipeline of signal acquisition, processing, output, and feedback. Modern research is increasingly guided by sophisticated frameworks that balance the critical trade-offs between signal fidelity and surgical invasiveness, as exemplified by the two-dimensional model of surgery and detection dimensions. As of 2025, the technology is in a pivotal translational phase, with numerous companies conducting human trials aimed at restoring motor and communication capabilities for people with severe paralysis. For researchers, the path forward involves not only refining signal acquisition and decoding algorithms for greater speed and accuracy but also rigorously addressing the accompanying ethical, clinical, and usability challenges to ensure these powerful technologies can be safely and effectively integrated into real-world applications.

Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technology establishes a direct communication pathway between the human brain and external devices, bypassing conventional neuromuscular routes [8] [9]. This revolutionary technology translates raw neurophysiological data into actionable commands, enabling individuals to control computers, prosthetic limbs, and other devices through thought alone [10]. The fundamental signal flow within a BCI system follows a structured sequence: acquisition of brain signals, preprocessing to enhance quality, feature extraction and translation into commands, and finally, execution of those commands through an output device, often incorporating real-time feedback to create a closed-loop system [11]. This whitepaper provides a detailed, technical breakdown of this communication pathway, contextualized within contemporary research and advanced signal acquisition methodologies.

The Core BCI Signal Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the standardized, sequential flow of information in a closed-loop BCI system, from initial signal acquisition to the final device output and feedback.

Stage 1: Signal Acquisition

The first critical stage involves capturing electrical or metabolic signals generated by neural activity. The methodologies vary significantly in their invasiveness and signal resolution.

Table 1: Neural Signal Acquisition Methods in BCI Research

| Method | Principle | Interface Type | Key Applications | Signal Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electroencephalography (EEG) [8] [12] | Measures electrical activity from the scalp surface. | Non-invasive | SSVEP paradigms [13], neurorehabilitation [11], cognitive monitoring. | Low signal-to-noise ratio, poor spatial resolution, high temporal resolution. |

| Electrocorticography (ECoG) [8] | Records electrical activity from the cortical surface. | Semi-invasive | Motor imagery, seizure focus localization, advanced communication. | Higher spatial and temporal resolution than EEG. |

| Intracortical Microelectrode Arrays [8] [12] | Records single-neuron or multi-unit activity from within brain tissue. | Invasive | High-performance prosthetics [10], complex device control. | Very high spatial and temporal resolution. |

| Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) [8] | Measures hemodynamic responses (blood oxygenation). | Non-invasive | Cognitive state monitoring, stroke rehabilitation. | Lower temporal resolution, good for sustained states. |

Stage 2: Signal Preprocessing

Raw neural signals are inherently noisy and contaminated by artifacts (e.g., eye blinks, muscle movement, line noise) [11]. Preprocessing is essential to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Common techniques include:

- Filtering: Applying band-pass filters to isolate frequency bands of interest (e.g., Mu rhythm 8-12 Hz for motor imagery) and notch filters to remove power line interference [13].

- Artifact Removal: Utilizing algorithms like Independent Component Analysis (ICA) to identify and remove components of the signal not originating from brain activity [11].

Stage 3: Feature Extraction and Translation

This stage converts the preprocessed signals into meaningful control commands, heavily relying on advanced algorithms.

Feature Extraction

Distinctive patterns in the neural signals are identified. For EEG-based systems, this can include:

- Spectral Power: Quantifying power in specific frequency bands [11].

- Event-Related Potentials (ERPs): Detecting voltage fluctuations in response to specific stimuli, such as the P300 wave [13].

- Signal Complexity: Measuring features like spectral arc length for assessing movement smoothness [14].

Translation Algorithms

These algorithms map the extracted features to device commands. Machine Learning (ML) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) are central to modern BCI systems [11].

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): Effective for spatial and temporal pattern recognition in EEG data [13] [11].

- Support Vector Machines (SVMs): Used for classifying different mental states or movement intentions [11].

- Transfer Learning (TL): Reduces calibration time by adapting a pre-trained model to a new user, addressing the challenge of high inter-subject variability [11].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of AI/ML Algorithms in BCI Systems

| Algorithm | Primary Function | Reported Performance | Key Advantage | Associated Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [13] [11] | SSVEP & Motor Imagery Classification | High accuracy in SSVEP signal recognition [13]. | Automatic feature learning from raw/poor signals. | Computationally intensive, requires large datasets. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) [11] | Mental State Classification | Used in cognitive assessment and AD/ADRD monitoring [11]. | Effective in high-dimensional spaces. | Performance depends on kernel selection. |

| Transfer Learning (TL) [11] | Cross-Subject/Cross-Session Adaptation | Reduced training time from weeks to under 4 hours with 95% accuracy [10]. | Mitigates calibration burden for new users. | Risk of negative transfer if data domains differ greatly. |

| Filter Bank CCA [13] | SSVEP Frequency Recognition | Enabled high ITRs for continuous control tasks like drone flight [14]. | Robustness against background EEG noise. | Specific to SSVEP paradigms. |

Experimental Protocol: SSVEP for Continuous Device Control

To illustrate the application of this pathway, the following workflow details a representative experiment for non-invasive, continuous control of a drone using Steady-State Visual Evoked Potentials (SSVEP) [14].

Detailed Methodology:

- Stimulus Presentation: The user is presented with visual stimuli flickering at distinct frequencies (e.g., 8.5 Hz, 10 Hz, 11.5 Hz) [13] [14]. In advanced setups, the drone's live video feed is embedded within these stimuli to provide a first-person perspective [14].

- Signal Acquisition & Preprocessing: EEG data is collected using a multi-channel headset. The raw data is band-pass filtered (e.g., 5-40 Hz) to isolate the frequencies relevant to the SSVEP response.

- Feature Extraction & Translation: The Filter Bank Canonical Correlation Analysis (FBCCA) algorithm is employed to identify the dominant SSVEP frequency in the user's EEG, which corresponds to the attended stimulus [14].

- Command Mapping & Output: The decoded frequency is mapped to a discrete command (e.g., "move forward," "turn left"). A novel control strategy then translates these discrete commands into smooth, continuous motions for the drone, enabling real-time navigation [14].

- Performance Metrics: The system's efficacy is evaluated using:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Technologies for Advanced BCI Research

| Item / Technology | Function / Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| High-Channel Count Acquisition Chip (e.g., SX-R128S4) [12] | High-throughput neural signal acquisition; enables recording from 128+ channels for high-resolution data. | Invasive BCI research for capturing detailed neural population activity. |

| Programmable Metasurface (STC) [13] | Provides visual stimulation for SSVEP and manipulates electromagnetic waves for secure wireless communication. | Used in secure BCI systems for harmonic-encrypted beamforming at the physical layer. |

| Utah Array / Intracortical Microelectrodes [10] [15] | Invasive neural interface for recording single-unit or multi-unit activity; provides the highest signal quality. | Foundation for high-fidelity BCI systems in clinical trials (e.g., BrainGate, Neuralink). |

| Dry EEG Electrodes [8] | Simplifies set-up for non-invasive BCIs by eliminating the need for conductive gel. | Consumer-grade and rapid-deployment BCI systems for usability outside the lab. |

| AI/ML Models (CNNs, TL) [13] [11] | Core software component for decoding neural signals and translating them into device commands. | Applied across all BCI types to improve accuracy, speed, and adaptability of systems. |

| Stentrode (Endovascular BCI) [10] [15] | Minimally invasive electrode array delivered via blood vessels; balances signal quality and safety. | Focus of clinical trials (e.g., by Synchron) for motor restoration without open-brain surgery. |

The BCI communication pathway is a sophisticated, multi-stage process that transforms neural signatures into functional control. Current research is focused on enhancing every stage of this pathway: developing higher-fidelity and less invasive acquisition hardware [12], creating more robust and adaptive AI-driven translation algorithms [11], and engineering closed-loop systems that provide meaningful feedback to the user [16]. The integration of advanced materials science, semiconductor technology, and artificial intelligence is pushing BCI technology from a primarily medical tool toward a future that may include seamless human-machine interaction across a wide spectrum of applications.

The human brain's operational currency is a complex symphony of bioelectrical signals, spanning multiple spatial and temporal scales. At the most fundamental level lies the action potential, a discrete all-or-nothing event facilitating long-distance communication along neuronal axons [17]. The coordinated synaptic and intrinsic transmembrane currents from neuronal populations collectively generate macroscopic field potentials, which include the local field potential (LFP), electrocorticogram (ECoG), and electroencephalogram (EEG) [18]. For brain-computer interface (BCI) technology, understanding this continuum from single-neuron spikes to population-level fields is paramount, as different BCI modalities tap into different levels of this signaling hierarchy. The efficacy of BCI systems is fundamentally contingent upon the precise acquisition and interpretation of these neural signals, which reflect the brain's intricate computational processes and provide the raw data for decoding intentional commands [6] [4].

Fundamental Mechanisms of Neural Signaling

Action Potentials: The Unit of Neural Communication

The action potential is a regenerative, self-propagating wave of electrical activity that travels along the axonal membrane of neurons [17]. According to the classical Hodgkin-Huxley model, this phenomenon arises from voltage- and time-dependent changes in the membrane's permeability to sodium (Na⁺) and potassium (K⁺) ions, leading to a characteristic waveform featuring a rapid depolarization followed by repolarization and a brief hyperpolarization [17]. This electrical impulse serves as a binary digital code for transmitting information over long distances within the nervous system with high fidelity, and its initiation in the axon initial segment follows an all-or-nothing principle [17].

Recent theoretical work suggests that action potential propagation may involve additional biophysical mechanisms beyond purely ionic conductance. Some models propose that the ion flow through Naᵥ channels generates a near-field quasi-static electric field (ephaptic field) in the extracellular space, which may facilitate excitation of nearby passive axons and enable zig-zag propagation patterns within axon bundles, potentially explaining the rapid transmission velocities observed in myelinated axons [19].

Table: Key Characteristics of Neural Action Potentials

| Property | Description | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| All-or-None Principle | Once initiation threshold is reached, a full-amplitude spike occurs regardless of stimulus strength [17]. | Ensures faithful, high-fidelity transmission of information along axons. |

| Refractory Period | Brief period post-firing when neuron is resistant to generating another action potential [17]. | Enforces unidirectional propagation and limits maximum firing rate. |

| Ionic Basis | Primarily involves voltage-gated Na⁺ influx (depolarization) followed by K⁺ efflux (repolarization) [17]. | Generates characteristic spike waveform and enables regenerative propagation. |

| Propagation Velocity | Ranges from <1 m/s to >100 m/s; influenced by axon diameter and myelination [19]. | Determines timing and synchrony of information arrival in neural circuits. |

From Unitary Currents to Macroscopic Field Potentials

When action potentials reach presynaptic terminals, they trigger neurotransmitter release, which in turn generates postsynaptic potentials in target neurons. These transmembrane currents, along with other intrinsic membrane potential fluctuations, constitute the primary generators of the extracellular field potential [18]. The superposition of all ionic processes—from fast action potentials to slow synaptic and intrinsic currents—within a volume of brain tissue generates a measurable extracellular potential (Vₑ) at any given location [18].

The characteristics of the local field potential (LFP) waveform, including its amplitude and frequency content, depend on several factors: the magnitude and sign of individual current sources, their spatial density, the temporal coordination (synchrony) of these sources, and the passive electrical properties of the extracellular medium [18]. Synaptic activity is often the dominant contributor to LFP under physiological conditions, particularly excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) mediated by AMPA and NMDA receptors [18]. The influx of cations at the synapse creates an extracellular sink, which is electrically balanced by a distributed return current (source) along the neuronal membrane, forming a current dipole [18].

Table: Primary Contributors to Extracellular Field Potentials

| Source Type | Temporal Characteristics | Relative Contribution to LFP |

|---|---|---|

| Synaptic Currents | Relatively slow (milliseconds); excitatory and inhibitory [18]. | Often the most significant contributor in physiological conditions [18]. |

| Fast Na⁺ Action Potentials | Very fast (sub-millisecond) [18]. | Generates large-amplitude Vₑ deflections near soma; contributes to high-frequency components [18]. |

| Ca²⁺ Spikes | Slower than Na⁺ spikes [18]. | Can substantially shape extracellular field [18]. |

| Intrinsic Membrane Oscillations | Rhythmic, frequency-dependent [18]. | Contributes to specific frequency bands in the field potential [18]. |

| GABAₐ Receptor-Mediated Currents | Fast to medium kinetics [18]. | Can generate substantial transmembrane currents in depolarized neurons [18]. |

Signal Acquisition Methodologies in BCI Research

A Dimensional Framework for Neural Signal Acquisition

BCI signal acquisition technologies can be classified along two primary dimensions: the surgical invasiveness of the procedure and the operating location of the sensors [4]. This two-dimensional framework helps reconcile clinical considerations with engineering requirements, balancing signal fidelity against surgical risk and biocompatibility concerns [4].

The surgery dimension encompasses three categories of increasing invasiveness:

- Non-invasive: Procedures that cause no anatomically discernible trauma (e.g., EEG) [4].

- Minimal-invasive: Procedures causing anatomical trauma that spares brain tissue (e.g., endovascular stents) [4].

- Invasive: Procedures causing anatomically discernible trauma at the micron scale or larger to brain tissue (e.g., intracortical microelectrodes) [4].

The detection dimension classifies sensors based on their operational location:

- Non-implantation: Signals acquired through sensors on the body surface (e.g., scalp EEG) [4].

- Intervention: Sensors leveraging naturally existing cavities (e.g., blood vessels) without damaging tissue integrity [4].

- Implantation: Sensors placed within human tissue (e.g., intracortical arrays) [4].

BCI Signal Acquisition Framework Diagram

Comparative Analysis of BCI Recording Modalities

Different BCI recording modalities access neural signals at various spatial and temporal scales, creating a trade-off between signal resolution and invasiveness [18] [4].

Table: Comparison of BCI Signal Acquisition Technologies

| Modality | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Primary Signals Captured | Key Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEG (Electroencephalography) [18] | Low (integrated over ~10 cm² or more) | High (milliseconds) | Scalp-recorded macroscopic fields | Non-invasive, portable, low cost | Skull attenuates and spatially blurs signals, low signal-to-noise ratio [11] |

| ECoG (Electrocorticography) [18] | Intermediate (<5 mm² with grid electrodes) | High (milliseconds) | Cortical surface field potentials | Bypasses signal-distorting skull, higher spatial resolution than EEG | Requires craniotomy, limited to superficial cortical areas [18] |

| LFP (Local Field Potential) [18] | High (microns to millimeters) | High (milliseconds) | Local population activity near microelectrode | Direct brain access, records from deep structures, high information content | Invasive, risk of tissue damage, signal locality [18] |

| MEG (Magnetoencephalography) [18] | Intermediate (2-3 mm in principle) | High (milliseconds) | Magnetic fields from intracellular currents | Less dependent on conductivity of extracellular space than EEG | Expensive equipment, limited availability [18] |

| Intracortical Microelectrodes [4] | Very high (single neuron) | Very high (sub-millisecond) | Single/multi-unit activity & LFP | Gold standard for resolution, direct neural spiking | Highly invasive, biocompatibility challenges, signal stability [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Neural Signal Investigation

Protocol for Investigating Hierarchical Predictive Coding Signals

Predictive coding theory posits that the brain continuously generates prediction signals and prediction-error signals through hierarchical cortical interactions [20]. The following protocol outlines a method to disentangle these signals using EEG during an auditory local-global paradigm [20].

Objective: To identify hierarchical prediction and prediction-error signals and their spatio-spectral-temporal signatures in human EEG [20].

Experimental Design:

- Participants: 30 healthy adults with normal hearing [20].

- Stimuli: Three stimulus items: standard tone (x), deviant tone (y), and omission (o, no tone). Sequences consist of 2 or 3 items with three temporal structures: (xx/xxx), (xy/xxy), or (xo/xxo) [20].

- Block Design: 8 blocks of 144 trials each, with distinct configurations of sequence length and trial numbers to manipulate transition probabilities (TPx, TPy, TPo) and sequence probabilities (SPxx, SPxy, SPxo) [20].

- Counterbalancing: Each block delivered twice with reversed tone assignments (tone A as x/B as y, then B as x/A as y) to eliminate tone-specific effects [20].

Procedure:

- Participants listen to tone sequences while maintaining visual fixation and attention to sounds [20].

- EEG recorded using 64-channel system with appropriate sampling rate (≥1000 Hz) [20].

- Vigilance monitored throughout task [20].

Data Analysis:

- Preprocessing: Standard EEG preprocessing including filtering, artifact removal, and epoching [20].

- Tensor Decomposition: Use tensor-based decomposition method to extract prediction and prediction-error components from EEG responses [20].

- Model Fitting: Fit hierarchical predictive coding model to EEG data to quantitatively separate prediction and prediction-error signals [20].

- Spatio-Spectral-Temporal Analysis: Identify neural signatures in specific frequency bands (e.g., low beta, high beta, gamma) associated with prediction and prediction-error signals at different hierarchical levels [20].

Expected Outcomes: Identification of low-level prediction signals in high beta band representing tone-to-tone transitions, high-level prediction signals in low beta band representing sequence structure, and prediction-error signals in gamma band dependent on prior predictions [20].

Predictive Coding EEG Experiment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Neural Signal Investigation

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density EEG System (64+ channels) | Recording macroscopic field potentials from scalp surface [18] [20]. | Enables source localization; requires conductive gel/paste; appropriate sampling rate ≥1000 Hz [20]. |

| Silicon-Based Polytrodes | High-density recording of LFP and single-unit activity in brain tissue [18]. | Multiple closely-spaced recording sites; minimal tissue damage; high spatial resolution [18]. |

| Voltage-Sensitive Dyes | Optical detection of membrane voltage changes in neuronal populations [18]. | Directly measures transmembrane voltage; limited by phototoxicity and signal-to-noise ratio [18]. |

| Flexible Subdural Grid Electrodes | ECoG recording directly from cortical surface [18]. | Platinum-iridium or stainless steel; spatial resolution <5 mm²; bypasses signal-distorting skull [18]. |

| Computational Modeling Software | Simulating neural dynamics and field potential generation [18]. | Implement Hodgkin-Huxley or predictive coding models; requires precise biophysical parameters [18] [20]. |

| Tensor Decomposition Algorithms | Separating interdependent neural signals (e.g., prediction vs. prediction-error) [20]. | Enables disentangling causally entangled signals in EEG/ECoG data [20]. |

The pathway from unitary action potentials to macroscopic field potentials represents a hierarchical cascade of neural information processing that forms the biological foundation for brain-computer interfaces. The biophysical principles governing action potential generation and propagation—including ionic conductance dynamics and potentially ephaptic coupling mechanisms—directly shape the extracellular signals that BCIs aim to capture and decode [18] [17] [19]. Understanding these fundamental mechanisms enables more sophisticated signal acquisition strategies that balance the trade-offs between invasiveness and resolution [4].

Future directions in BCI research will likely focus on closing the loop between neural signal decoding and adaptive stimulation, leveraging advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning to enhance signal classification and interpretation [11]. The integration of multi-scale recording approaches—combining information from single units, LFPs, and macroscopic fields—holds particular promise for developing more robust and naturalistic BCIs. As these technologies evolve, they will continue to be guided by our deepening understanding of how micro-scale neural events give rise to macro-scale field potentials that reflect the brain's computational states and intentional commands.

Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technology establishes a direct communication pathway between the human brain and external devices, bypassing the body's normal neuromuscular output channels [21] [22]. The efficacy of any BCI system hinges on the effective implementation of its core neurophysiological paradigms—the specific mental tasks or stimulus presentation protocols designed to elicit distinguishable brain activity patterns [21]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of three foundational BCI paradigms: Motor Imagery (MI), P300, and Steady-State Visual Evoked Potentials (SSVEP). Framed within the broader context of BCI basic working principles and signal acquisition research, this guide details the neural mechanisms, experimental protocols, and clinical applications of each paradigm, providing researchers with the essential knowledge for system design and implementation.

BCI Working Principles and Signal Acquisition Framework

A typical BCI system operates through a coordinated sequence of four stages: Signal Acquisition, Processing, Output, and Feedback, forming a closed-loop system [4] [23]. The initial acquisition stage is paramount, as it determines the quality and nature of the neural signals available for all subsequent decoding and control operations [4].

Signal acquisition technologies can be classified along two primary dimensions: the surgical invasiveness of the procedure and the operational location of the sensors [4]. The surgery dimension encompasses non-invasive (no anatomical trauma), minimally-invasive (trauma that spares brain tissue), and invasive (trauma affecting brain tissue) procedures. The detection dimension classifies technologies based on whether sensors operate via non-implantation (on the body surface), intervention (within natural body cavities like blood vessels), or implantation (within human tissue) [4]. As one progresses from non-invasive to invasive methods, the theoretical upper limit of signal quality increases, but this comes with heightened surgical risk, ethical considerations, and implementation complexity [4].

Table: Classification of BCI Signal Acquisition Technologies

| Surgery Dimension | Detection Dimension | Example Technologies | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Invasive | Non-Implantation | EEG, MEG, fMRI [21] [22] | Safe, low cost; lower spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio |

| Minimally-Invasive | Intervention | Endovascular Stent Electrodes [4] | Moderate signal quality; requires clinical specialists |

| Invasive | Implantation | Microelectrode Arrays, ECoG [21] [22] [4] | High signal fidelity; requires involvement of neurosurgeons |

The selection of an appropriate paradigm is deeply interdependent with the choice of signal acquisition method. Well-designed paradigms enhance the detectability and separability of brain signals within the constraints of the chosen acquisition technology [21] [23].

Motor Imagery (MI) Paradigm

Neural Basis and Principles

The Motor Imagery (MI) paradigm is based on the mental rehearsal of a motor act without any overt physical movement or external stimulus [23]. Kinesthetic imagination (feeling the movement) activates neural circuits in the primary motor cortex (M1), premotor cortex, and supplementary motor area that substantially overlap with those involved in actual motor execution [24] [23]. This mental process induces oscillatory changes in sensorimotor rhythms, specifically the mu (8-13 Hz) and beta (18-26 Hz) frequency bands [24]. The key phenomenon is Event-Related Desynchronization (ERD), a power decrease in these rhythms contralateral to the imagined limb, reflecting cortical activation [24]. Sometimes, an Event-Related Synchronization (ERS), a power increase, can be observed in ipsilateral regions [23].

Experimental Protocol and Design

A typical MI-BCI protocol for upper limb rehabilitation involves several key stages [24]:

- Participant Preparation and Setup: Participants sit comfortably in a chair, minimizing eye blinks and body movements. EEG is recorded using systems like the BioSemi ActiveTwo with 64 electrodes arranged in the international 10-20 montage [25]. Signals are referenced to the right mastoid and grounded to the left, sampled at 2048 Hz, and then down-sampled to 256 Hz for analysis. Artifact removal is performed using an infinite impulse response filter and wavelet-based neural networks [25].

- Task Design and Cue Presentation: The paradigm consists of multiple trials. Each trial begins with a fixation cross displayed on the screen for 2 seconds. A visual cue (e.g., an arrow or picture of a hand/foot) then instructs the participant to perform kinesthetic imagery of a specific movement (e.g., left hand, right hand, or foot) for a duration of 3-5 seconds [25] [24].

- Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: EEG data is recorded during the task performance. Standard preprocessing includes band-pass filtering (e.g., 1-50 Hz), common average re-referencing, and artifact removal for ocular, muscular, or other noise sources [25].

- Feature Extraction and Classification: Features are extracted from the mu and beta bands, often focusing on ERD/ERS patterns. Common spatial patterns (CSP) is a widely used algorithm for feature extraction. These features are then fed into classifiers like Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) or Support Vector Machines (SVM) to decode the intended movement [25].

- Feedback and Reinforcement: In closed-loop rehabilitation systems, the classifier's output is translated into a control signal for an external device, such as a functional electrical stimulation (FES) system or a robotic arm, providing the user with real-time feedback on their mental task performance [24].

Enhancements and Clinical Applications

A significant challenge in MI-BCI is "BCI inefficiency," where a portion of users cannot generate classifiable signals [25]. To address this, hybrid training approaches have been developed. For example, Somatosensory-Motor Imagery (SMI) combines MI with somatosensory attentional orientation (SAO) using tangible objects (e.g., a hard ball). This method has been shown to improve classification performance, particularly in poor performers, by engaging both motor and somatosensory cortices [25].

Another innovative approach is task-to-task transfer learning, which leverages the shared neural mechanisms between Motor Execution (ME), Motor Observation (MO), and MI. Training a classification model on the easier ME or MO tasks and then applying it to MI data can achieve similar accuracy while reducing user fatigue and calibration time, making the system more user-friendly [26].

In clinical practice, MI-BCI has shown significant promise in stroke rehabilitation. A randomized controlled trial demonstrated that stroke patients who received MI-BCI therapy combined with conventional rehabilitation showed greater improvement in upper extremity function (measured by Fugl-Meyer Assessment) and exhibited significant changes in cortical activation patterns on fMRI, compared to a control group receiving only conventional therapy [24]. The therapy induces beneficial functional activity-dependent plasticity, promoting motor recovery [24].

Table: Key Research Reagents and Materials for MI-BCI Research

| Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| EEG Acquisition System | BioSemi ActiveTwo, g.USBamp [25] [27] | Records scalp electrical activity with high temporal resolution. |

| EEG Electrodes/Cap | 64-channel Electro-Cap [25]; g.SAHARA dry electrodes [27] | Interfaces with the scalp for signal recording; dry electrodes offer easier setup. |

| Electrode Gel | Electrolytic gel | Ensures good electrical conductivity for wet electrode systems. |

| Stimulus Presentation Software | Unity, BCI2000 [28] [27] | Presents visual cues and controls experimental timing. |

| Feedback Devices | Robotic Arm, Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) system [24] | Provides real-time, tangible feedback to user, reinforcing neural plasticity. |

| fMRI Scanner | 3T MRI Scanner [24] | Validates neural correlates of MI and measures therapy-induced plasticity. |

| Data Analysis Tools | MATLAB, EEGLAB, BCILAB | For signal preprocessing, feature extraction (CSP), and classification (LDA, SVM). |

P300 Paradigm

Neural Basis and Principles

The P300 is an event-related potential (ERP) component observed in the EEG approximately 250-500 ms after the presentation of a rare, task-relevant, or surprising stimulus [28]. Its amplitude is inversely related to the probability of the target stimulus, and it is considered a neural correlate of context updating or attention allocation [28]. In BCI systems, the P300 speller paradigm, first described by Farwell and Donchin, presents a matrix of characters to the user. The user focuses attention on a desired character (the target) while rows and columns of the matrix flash in a random sequence. Each time the row or column containing the target character flashes, it elicits a P300 response, allowing the system to identify the intended character [28].

Experimental Protocol and Design

The standard P300 speller experiment involves the following steps [28]:

- Stimulus Presentation: A 6x6 or similar matrix of characters is displayed. The stimulus presentation is characterized by the flash rate, which is the frequency at which the rows/columns intensify. Studies have shown that lower flash rates (e.g., 8-16 Hz) generally produce higher P300 amplitudes and better classification accuracy, though the optimal rate for information transfer rate may vary by user [28].

- Data Acquisition: EEG is typically recorded from 16 scalp electrodes (e.g., Fz, Cz, Pz, Oz). The signals are amplified, digitized (e.g., at 512 Hz), and band-pass filtered (e.g., 0.5-30 Hz) [28].

- Signal Processing and Classification: Epochs of EEG data (e.g., 0-800 ms post-stimulus) are extracted for each flash. A stepwise linear discriminant analysis (SWLDA) is commonly used for classification, where the system learns to distinguish between target flashes (which elicit a P300) and non-target flashes [28]. The character that receives the highest discriminant score when its corresponding row and column flash is selected as the output.

Table: Impact of Stimulus Parameters on P300 BCI Performance

| Parameter | Effect on P300 & Performance | Optimal Range / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Flash Rate | Lower rates increase P300 amplitude but may slow communication speed [28]. | 8-16 Hz (user-dependent); optimal for characters/min varies. |

| Inter-Stimulus Interval (ISI) | Longer ISI (time between flash onsets) produces larger P300 and late negative slow wave amplitudes [28]. | 125-250 ms (for 4-8 Hz rates). |

| Number of Flash Repetitions | More repetitions increase classification accuracy but reduce selection speed. | Typically 10-15 repetitions per character selection. |

| Stimulus Type | Intensification of rows/columns is standard; other modalities (e.g., auditory) are also used. | Visual intensification is most common and effective. |

Steady-State Visual Evoked Potential (SSVEP) Paradigm

Neural Basis and Principles

The Steady-State Visual Evoked Potential (SSVEP) is an oscillatory brain response elicited in the visual cortex when a user gazes at a visual stimulus flickering at a constant frequency, typically between 3.5-75 Hz [29]. The resulting EEG signal shows peaks of activity at the fundamental frequency of the stimulus and its harmonics, effectively "entraining" the brain's rhythmic activity to the external stimulus [27] [29]. SSVEPs have a high signal-to-noise ratio and require minimal user training, making them suitable for high-information-transfer-rate BCIs [27].

Experimental Protocol and Design

A standard SSVEP-BCI setup involves [27]:

- Stimulus Design: Multiple visual targets are presented on a screen, each flickering at a distinct frequency. Frequencies are often chosen from prime numbers in the highly responsive range (e.g., 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23 Hz) to minimize interference from harmonics [27].

- Stimulation Methods:

- Single-Frequency Flicker: Each target flickers at a single frequency [27].

- Multi-Frequency Coding (Dual/Tri-Frequency): To increase the number of possible commands without requiring more frequencies, each stimulus can be coded with a unique combination of multiple frequencies (e.g., two or three). Methods for combining frequencies include frequency superposition (OR, ADD logic) and checkerboard patterns [27].

- Data Acquisition: EEG is recorded from occipital and parieto-occipital channels (e.g., PO3, POz, PO4, O1, Oz, O2) using a sampling rate of 512 Hz or higher. A 50 Hz/60 Hz notch filter is applied to remove line noise [27].

- Signal Processing and Classification: The canonical correlation analysis (CCA) method is a standard and efficient algorithm for detecting SSVEPs. CCA finds the linear correlation between the multi-channel EEG data and a set of reference signals at the stimulus frequencies and their harmonics, identifying the target frequency that maximizes the correlation [27].

Table: SSVEP Stimulation Paradigms and Their Characteristics

| Paradigm | Stimulation Method | Mechanism | Advantages & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Frequency | Simple flickering of a field or object [27]. | u = ½ sgn(sin(2πft)) + ½ | Simple to implement; suitable for systems with few commands. |

| Dual-Frequency (Superposition OR) | Two square waves superimposed with OR logic: S_OR,2 = u1 ∨ u2 [27]. | Stimulus is ON if either frequency signal is ON. | Increases the number of unique targets without increasing the base frequency pool. |

| Dual-Frequency (Superposition ADD) | Two square waves superimposed with ADD logic: S_ADD,2 = ½ u1 + ½ u2 [27]. | Brightness from two frequencies is summed. | Increases the number of unique targets without increasing the base frequency pool. |

| Checkerboard | Two frequencies delivered separately in alternating squares of an 8x8 checkerboard [27]. | Delivers two frequencies spatially separated within one stimulus. | Reduces perceptual interference between frequencies. |

The three core BCI paradigms each possess distinct characteristics that make them suitable for different applications and user groups.

Table: Comparative Summary of Key BCI Paradigms

| Feature | Motor Imagery (MI) | P300 | Steady-State VEP (SSVEP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Basis | Endogenous ERD/ERS of sensorimotor rhythms [23]. | Exogenous P300 event-related potential [28]. | Exogenous entrainment of visual cortex oscillations [29]. |

| Key Signal Features | Power decrease/increase in Mu/Beta bands (8-30 Hz) [24]. | Positive peak ~300-500 ms post-stimulus [28]. | Peaks at stimulus frequency and harmonics [27]. |

| User Task | Imagine body movement without executing it [23]. | Attend to rare target stimuli among frequent non-targets [28]. | Gaze at a flickering visual stimulus [27]. |

| Typical Accuracy | Varies widely; can be >80% in good performers, but ~50-70% in poor performers [25]. | Generally high (>90% with sufficient repetitions) [28]. | Generally high (>90%) [27]. |

| Information Transfer Rate | Low to Moderate | Moderate | High |

| User Training Required | Extensive training often needed [25] [26]. | Minimal training required [28]. | Minimal training required [27]. |

| Primary Clinical Application | Neurorehabilitation (e.g., stroke) [24]. | Communication for severely paralyzed (e.g., ALS) [28]. | Communication and environmental control. |

In summary, MI, P300, and SSVEP represent three pillars of non-invasive BCI technology. The choice of paradigm is a fundamental decision that directly impacts system performance, user experience, and clinical applicability. MI offers an intuitive, endogenous control strategy highly suited for motor rehabilitation. The P300 provides a reliable communication channel with minimal user training. SSVEP enables high-speed communication through exogenous visual entrainment. Future developments will likely focus on user-centered design, hybrid paradigms that combine the strengths of multiple approaches, and the integration of advanced AI to improve decoding performance, ultimately making BCI technology more robust and accessible for a wider range of applications [21].

The closed-loop brain-computer interface (BCI) represents a paradigm shift in human-computer interaction, establishing a direct bidirectional communication pathway between the brain and external devices. This integrated system architecture significantly enhances the efficacy, adaptability, and user-specificity of neurotechnology applications across medical, rehabilitative, and augmentative domains. By dynamically processing acquired neural signals and providing targeted feedback, closed-loop BCIs create an adaptive interaction cycle that enables real-time modulation of brain activity. This technical review comprehensively examines the core components, operational principles, and experimental methodologies underlying closed-loop BCI systems, with particular emphasis on their working principles and signal acquisition foundations. The synthesis of these elements creates a robust framework for developing next-generation neurotechnologies capable of restoring, replacing, and enhancing human cognitive and motor functions.

Brain-computer interface (BCI) technology has evolved from a scientific concept to a transformative tool that establishes a direct communication channel between the brain and external devices, bypassing conventional neuromuscular pathways [30]. A closed-loop BCI system represents the most advanced implementation of this technology, characterized by its bidirectional flow of information—reading neural signals and writing feedback stimuli in a continuous, adaptive cycle [30]. This self-regulating architecture stands in stark contrast to open-loop systems, which operate without incorporating user feedback to adjust their output [30].

The fundamental operational principle of closed-loop BCI relies on its four integrated components: signal acquisition, processing, output, and feedback [4]. These components work in concert to form a continuous loop that enables the system to dynamically adapt to the user's changing neural states and intentions. The system's ability to sense the user's physiological composition and deliver stimulation only when required represents a significant advancement in treatment modalities for neurological disorders, potentially reducing side effects and conserving power [30]. This integrated approach has profound implications for clinical applications, particularly for patients with complex nervous system diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's disease, dementia, and depression [30].

Core Components of a Closed-Loop BCI System

Signal Acquisition: The Input Gateway

Signal acquisition forms the critical first stage of any BCI system, responsible for detecting and recording cerebral signals with sufficient fidelity for subsequent processing and decoding [4]. The efficacy of the entire BCI system is predominantly contingent upon its signal acquisition module, which bears the fundamental responsibility for capturing neural activity [4]. Acquisition technologies can be classified through a two-dimensional framework encompassing both surgical invasiveness and sensor operating location [4].

Table 1: Classification of BCI Signal Acquisition Technologies

| Surgical Dimension | Detection Dimension | Example Technologies | Signal Quality | Clinical Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-invasive | Non-implantation | EEG, fNIRS, MEG [30] [8] | Low to Moderate | Minimal |

| Minimal-invasive | Intervention | Endovascular stents [4] | Moderate to High | Moderate |

| Invasive | Implantation | ECoG, Intracortical microelectrodes [30] [4] | High | Significant |

Electroencephalography (EEG) remains the most prevalent non-invasive acquisition method due to its portability, affordability, and temporal resolution [30]. EEG-based systems can be further categorized according to the nature of the recorded brain activity: "evoked" potentials (such as P300 and steady-state visually evoked potential - SSVEP) generated in response to external stimuli, and "spontaneous" activity (such as motor imagery - MI) generated volitionally by the user [30]. Invasive techniques, including electrocorticography (ECoG) and intracortical microelectrode arrays, capture signals directly from the brain's surface or cortical layers, providing superior spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio at the cost of requiring surgical implantation and associated clinical risks [30] [4].

Signal Processing: From Raw Data to Decoded Intent

The processing component transforms raw, often noisy neural signals into interpretable commands through a multi-stage algorithmic pipeline [31] [4]. This transformation involves preprocessing to enhance signal quality, feature extraction to identify discriminative neural patterns, and classification to decode the user's intended action [31].

Preprocessing techniques typically include filtering to isolate frequency bands of interest and artifact rejection methods to remove contamination from ocular, muscular, or environmental sources [31]. Subsequent feature extraction identifies salient characteristics in the neural signals, which may include time-domain amplitudes, frequency power distributions, or spatial activation patterns [31]. Finally, decoding algorithms translate these features into control commands using machine learning approaches such as linear discriminant analysis, support vector machines, or deep neural networks [31] [4].

The transition from offline analysis of recorded data to online, real-time processing represents a critical qualitative leap in BCI development [31]. While offline evaluation helps identify promising algorithms, online closed-loop testing remains the gold standard for validating BCI performance, as it accounts for the dynamic interaction between the user and the system [31].

Output Generation: Executing Commands

The output component translates the decoded neural commands into concrete actions executed through external devices [4]. This component serves as the effector mechanism of the BCI system, bridging the decoded neural intent with tangible outcomes in the user's environment.

Output devices span a diverse spectrum of applications, including:

- Neuroprosthetics: Robotic arms, grasping devices, and exoskeletons that restore motor function [30] [8]

- Communication aids: Spelling systems and speech synthesizers that enable expression for non-verbal individuals [8]

- Environmental controllers: Wheelchair navigation systems and smart home interfaces that increase autonomy [30]

- Functional stimulation systems: Devices that activate paralyzed muscles to restore movement [30]

The effectiveness of the output component depends critically on its precise synchronization with the decoded neural commands and its reliability in executing intended actions consistently across diverse usage contexts.

Feedback: Closing the Loop

Feedback constitutes the defining element of closed-loop BCI systems, completing the communication cycle by informing the user about the system's interpretation of their neural activity and the resulting outcome [30] [4]. This component enables real-time adjustment and learning by both the user and the system, creating a dynamic adaptive process that is fundamental to closed-loop operation.

Feedback can be provided through various sensory modalities:

- Visual feedback: Computer cursors, virtual avatars, or graphical representations [31]

- Auditory feedback: Tones, speech, or spatial sounds that convey information about performance [4]

- Tactile feedback: Vibrotactile or electrotactile stimulation that provides somatosensory information [8]

- Direct neural stimulation: Electrical, magnetic, or optogenetic stimulation that directly modulates neural pathways [30]

The feedback mechanism enables the crucial process of neuroplasticity, where both the user's brain and the BCI system adapt to each other over time, leading to improved performance and more efficient interaction [30]. This bidirectional adaptation represents the cornerstone of advanced closed-loop BCI systems, particularly those designed for therapeutic applications where the goal is to induce lasting neural changes [30].

Figure 1: Closed-Loop BCI System Architecture. This diagram illustrates the bidirectional information flow in a closed-loop BCI system, highlighting the continuous cycle between user neural activity and system feedback.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Evaluating Closed-Loop BCI Performance

Comprehensive evaluation of closed-loop BCI systems requires a multifaceted approach that assesses both technical performance and user experience metrics [31]. The following protocol outlines a standardized methodology for system validation:

1. Participant Preparation and Calibration

- Recruit participants representing the target user population (e.g., patients with specific neurological conditions or healthy controls)

- Apply signal acquisition devices according to established safety protocols

- Conduct an initial calibration session to personalize signal processing parameters

- Record 5-10 minutes of baseline neural activity for subsequent normalization

2. System Configuration

- Set sampling rates appropriate for the acquisition technology (e.g., 250-1000 Hz for EEG, 2000 Hz for ECoG)

- Configure filter settings: bandpass 0.5-40 Hz for movement-related potentials, 70-200 Hz for high-frequency activity

- Initialize decoding algorithm with pre-trained or participant-specific model

- Set feedback parameters (type, intensity, timing) based on experimental conditions

3. Experimental Tasks

- Implement standardized BCI paradigms:

- Motor imagery: Hand, foot, or tongue movement imagination

- Visual evoked potentials: P300 speller or SSVEP paradigms

- Cognitive tasks: Mental calculation, spatial navigation, or working memory

- Include resting periods between trials to prevent fatigue

- Counterbalance task conditions to control for order effects

4. Data Collection and Metrics

- Record continuous neural data throughout the session

- Log system outputs and timing with millisecond precision

- Collect subjective user feedback through standardized questionnaires

- Monitor for artifacts and system malfunctions

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for Closed-Loop BCI Evaluation

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Target Values | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information Transfer | Classification Accuracy, Bit Rate [31] | >70% accuracy, >30 bits/min | Online performance during closed-loop operation |

| System Responsiveness | Signal Delay, Feedback Latency [31] | <300 ms total latency | Timing synchronization across components |

| User Experience | Usability Score, Workload Index [31] | Subjectively reported | Standardized questionnaires (e.g., SUS, NASA-TLX) |

| Long-Term Stability | Performance Consistency, Signal Quality [31] | <15% performance degradation | Repeated measures across sessions |

5. Data Analysis

- Preprocess data with standardized pipelines

- Extract relevant features from neural signals

- Compute performance metrics for each experimental condition

- Conduct statistical tests to evaluate significance of findings

- Correlate neural measures with behavioral outcomes

This protocol emphasizes the gold standard of online evaluation, where system performance is assessed during real-time, closed-loop operation rather than through offline analysis alone [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Closed-Loop BCI Development

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Acquisition | EEG caps with Ag/AgCl electrodes, ECoG grid electrodes, Intracortical microelectrode arrays [30] [4] | Capture neural signals with appropriate spatial and temporal resolution for the research objectives |

| Signal Processing | MATLAB with EEGLAB, BCILAB, Python with MNE, Scikit-learn, TensorFlow [31] | Preprocess, feature extract, and classify neural signals in real-time with established algorithmic approaches |

| Stimulation Devices | Transcranial electrical stimulators (tDCS, tACS), Transcranial magnetic stimulators (TMS), Optogenetic laser systems [30] | Provide targeted neural modulation for closed-loop feedback interventions |

| Output Interfaces | Robotic arms (e.g., Baxter, KUKA), Functional electrical stimulators, Text speller interfaces [30] [8] | Translate decoded neural commands into functional actions in the physical or virtual environment |

| Experimental Control | Presentation software, Psychtoolbox, Unity3D, LabVIEW [31] | Precisely control task paradigms, timing, and data synchronization across system components |

| Biocompatible Materials | Polyimide-based substrates, Platinum-iridium electrodes, Conductive hydrogels [4] | Ensure long-term stability and safety for invasive or semi-invasive neural interfaces |

Advanced Implementation: A Two-Dimensional Framework for Signal Acquisition

Recent advances in BCI technology have necessitated more sophisticated frameworks for understanding signal acquisition. A two-dimensional perspective that simultaneously considers surgical invasiveness and sensor operating location provides valuable guidance for both clinical implementation and engineering design [4].

The surgical dimension classifies procedures based on their level of invasiveness: non-invasive (no anatomical trauma), minimal-invasive (trauma that spares brain tissue), and invasive (trauma affecting brain tissue at micron scale or larger) [4]. Parallel to this, the detection dimension categorizes sensors based on their operating location: non-implantation (on body surface), intervention (within natural body cavities), and implantation (within human tissue) [4].

This framework reveals critical trade-offs in BCI design. As systems move toward more invasive surgical procedures and deeper sensor implantation, signal quality theoretically improves due to proximity to neural sources and reduced interference from biological layers [4]. However, this comes with increased clinical risk, ethical considerations, and implementation challenges [4].

Figure 2: Two-Dimensional BCI Signal Acquisition Framework. This classification system simultaneously considers surgical procedures and sensor operating locations to guide BCI design and implementation decisions.

The closed-loop BCI system represents a sophisticated integration of four functionally distinct yet interdependent components: acquisition, processing, output, and feedback. The critical advantage of this architecture lies in its capacity for bidirectional adaptation, where both the user's brain and the system algorithms co-adapt to optimize performance over time. This dynamic interaction enables the system to function not merely as a passive communication channel, but as an active participant in a learning cycle that can induce neuroplasticity and enhance functional outcomes.

Future developments in closed-loop BCI technology will likely focus on improving the seamlessness of integration across these four components, enhancing the temporal precision of feedback delivery, and developing more sophisticated adaptive algorithms that can anticipate user intentions. Additionally, the growing emphasis on user-centered design principles necessitates comprehensive evaluation methods that assess not only technical performance metrics but also usability, user satisfaction, and quality of life impacts [31]. As these systems continue to evolve, they hold tremendous potential to transform approaches to neurological rehabilitation, cognitive augmentation, and human-computer interaction.

Signal Acquisition Technologies: From Scalp to Cortex

Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technology facilitates direct communication between the brain and external devices, creating a non-muscular channel for interaction [6] [4]. The efficacy of any BCI system is fundamentally contingent upon its signal acquisition module, which bears the critical responsibility for detecting and recording cerebral signals [4]. A typical BCI system comprises four integral components: (1) signal acquisition, responsible for detecting and recording brain activity; (2) processing, which analyzes and decodes the recorded signals using specialized algorithms; (3) output, which executes the decoded intent through external devices; and (4) feedback, which closes the loop by informing the user of the system's interpretation and execution results [4].

The development of BCI systems is inherently interdisciplinary, necessitating collaboration between clinicians focused on surgical safety and engineers focused on signal performance [4]. This article elucidates a comprehensive two-dimensional framework for classifying BCI signal acquisition technologies, synthesizing surgical and engineering perspectives to provide researchers and developers with a structured understanding of current capabilities and trade-offs.

The Two-Dimensional Classification Framework

The proposed framework evaluates BCI signal acquisition techniques along two primary dimensions: the Surgery Dimension, which addresses the invasiveness of the procedure from a clinical perspective, and the Detection Dimension, which concerns the operational location of sensors from an engineering perspective [4]. This dual-axis approach enables a more nuanced analysis than unidimensional classifications.

Surgery Dimension: Invasiveness of Procedures

The surgery dimension categorizes techniques based on the anatomical trauma incurred during signal acquisition [4]. This classification directly impacts ethical considerations, implementation feasibility, and required clinical oversight.

Table 1: Classification Levels in the Surgery Dimension

| Classification Level | Anatomical Trauma Description | Clinical Requirements | Ethical & Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Invasive | No anatomically discernible trauma to the subject [4]. | Typically obviates continuous clinical oversight [4]. | Lower risk profile, suitable for wider populations; generally lower signal fidelity [4] [32]. |

| Minimally Invasive | Causes anatomically discernible trauma that spares brain tissue [4]. | Involvement of neurology/neurosurgery experts often required [4]. | Balanced trade-off; access to better signals than non-invasive without full craniotomy [4]. |

| Invasive | Causes anatomically discernible trauma at the micron scale or larger to brain tissue [4]. | Direct involvement of experienced neurosurgeons mandatory [4]. | Highest signal quality [33]; weighed against surgical risks and permanent implantation concerns [33] [4]. |

Detection Dimension: Operating Location of Sensors

The detection dimension classifies technologies based on the sensor's location during operation, which determines the theoretical upper limit of signal quality and influences biocompatibility risks [4].

Table 2: Classification Levels in the Detection Dimension

| Classification Level | Sensor Location & Operational Principle | Theoretical Signal Quality & Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Implantation | Sensor operates on the surface of the body without entering natural cavities [4]. | Lower theoretical upper limit; analogous to "listening to a chorus from outside the building" where only large-scale neuronal sums are detectable amid noise [4]. |

| Intervention | Sensor leverages naturally existing cavities (e.g., blood vessels) without harming tissue integrity [4]. | Intermediate signal quality; sensors are closer to neural sources than non-implantation, but not embedded within tissue. |

| Implantation | Sensor is implanted within human tissue [4]. | Highest signal quality; minimal distance to signal source and fewest signal-degrading barriers [4]. Prone to tissue integration over time, complicating removal [4]. |

Figure 1: Two-Dimensional BCI Classification Framework. This diagram illustrates the core structure of the classification system, combining the Surgery and Detection dimensions.

Technical Analysis of BCI Modalities

Signal Characteristics Across the Framework