Beyond Accuracy: A Comprehensive Framework for Validating Brain-Computer Interface System Performance

This article provides a comprehensive guide to performance validation metrics for Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) systems, tailored for researchers and clinical professionals.

Beyond Accuracy: A Comprehensive Framework for Validating Brain-Computer Interface System Performance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to performance validation metrics for Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) systems, tailored for researchers and clinical professionals. It explores the foundational pillars of BCI evaluation, from established benchmarks like classification accuracy and information transfer rate to emerging considerations of temporal robustness and clinical relevance. The content details methodological approaches for signal processing and machine learning, addresses common performance challenges and calibration techniques, and introduces advanced validation frameworks for cross-session reliability and real-world readiness. By synthesizing these facets, the article aims to bridge the gap between laboratory research and robust, clinically deployable BCI technologies.

The Core Pillars of BCI Performance: Understanding Essential Metrics and Benchmarks

Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) have evolved from a scientific curiosity to transformative tools in neurorehabilitation, assistive technologies, and beyond. For researchers and drug development professionals, validating BCI system performance requires a nuanced understanding of the trade-offs between traditional laboratory metrics, like classification accuracy, and the practical demands of real-world utility, such as responsiveness and robustness. This guide provides a comparative analysis of BCI performance, detailing the experimental protocols and metrics essential for rigorous system evaluation.

A Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) establishes a direct communication pathway between the brain and an external device, transforming brain signals into commands [1]. The core components of a BCI system include signal acquisition, signal processing (encompassing feature extraction, classification, and translation), and the application interface [1]. While classification accuracy is the most reported metric in literature, it is insufficient alone. Real-world applicability depends on a balance of several factors, including the Information Transfer Rate (ITR), system responsiveness (latency), false positive rate, and power efficiency for implantable or portable systems [2] [3]. The transition from a controlled lab environment to real-world scenarios introduces challenges such as signal noise, user variability, and the critical need for swift, reliable operation, especially in clinical applications like post-stroke rehabilitation [3] [4].

Comparative Performance Analysis of BCI Systems

The performance of a BCI system is influenced by the chosen signal acquisition method, the processing algorithms, and the intended application. The tables below provide a comparative overview of these factors across different system types and algorithmic approaches.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of BCI Acquisition Modalities

| Feature | EEG (Non-Invasive) | ECoG (Semi-Invasive) | MEA (Fully-Invasive) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Low (cm) | High (mm) | Very High (μm) |

| Signal Quality | Susceptible to noise and artifacts | High signal-to-noise ratio | Excellent signal-to-noise ratio |

| Typical Applications | Neurorehabilitation, assistive tech, gaming [5] [4] | Epileptic seizure focus localization, cortical mapping | Restoration of motor control, neuronal spiking studies [2] |

| Key Performance Trade-offs | Safety & cost vs. lower resolution & robustness [1] | Better signal than EEG but requires surgery [2] | Highest quality signals vs. highest surgical risk & tissue response [2] |

Table 2: Performance of Common Signal Processing Pipelines (MOABB Benchmark Data adapted from [6])

| Algorithm Type | Representative Methods | Reported Accuracy (Motor Imagery) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Riemannian Geometry | CSP + Riemannian Classifier | Superior performance across multiple paradigms [6] | Robust to noise, requires fewer data than DL for good performance [6] |

| Deep Learning (DL) | CNNs, EEGNet | Competitive performance, but requires large data volumes [6] | High model complexity, potential for automatic feature extraction [6] |

| Classical Machine Learning | CSP + LDA | High accuracy reported (e.g., ~87% in stroke rehab) [4] | Computationally efficient, well-understood, good benchmark model [3] [4] |

Table 3: Impact of Time Window Duration on Real-Time BCI Performance (Data adapted from [3])

| Time Window Duration | Classification Accuracy | False Positive Rate | System Responsiveness | Real-World Usability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shorter (e.g., 0.5-1s) | Lower | Higher | High (Low latency) | Better for real-time control, but less reliable [3] |

| Longer (e.g., 2-4s) | Higher [3] | Lower [3] | Low (High latency) | More reliable commands, but delays >0.5s can disrupt user experience [3] |

| Optimal Range (1-2s) | Good | Good | Acceptable | Provides the best trade-off between accuracy and responsiveness for rehabilitation [3] |

Experimental Protocols for BCI Performance Validation

Robust validation is paramount. The following are detailed protocols for key experiments cited in this guide.

Protocol: Optimizing Temporal Parameters for Responsiveness

This protocol, based on the work by [3], investigates the trade-off between classification accuracy and system latency.

- Objective: To determine the optimal time window duration that balances high classification accuracy with acceptable responsiveness for real-time MI-BCI applications.

- Population: The study can involve post-stroke patients with motor deficits, as well as healthy subjects from external datasets (e.g., BCI Competition IV 2a) for reproducibility [3].

- Signal Acquisition: EEG signals are recorded from electrodes positioned over motor areas (e.g., FC3, FC4, C3, C4, CP3, CP4) using a standard system (e.g., Micromed SAM 32 FO) at a sampling rate of 256 Hz, bandpass filtered between 8-30 Hz [3].

- Paradigm: Participants perform a cue-based motor imagery task. Each trial consists of a rest period, a cue indicating which hand to imagine moving (e.g., left or right), and a 4-second motor imagery period [3].

- Data Processing:

- Feature Extraction: Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) is applied to the EEG signals to obtain features that maximize the variance between the two motor imagery classes [3].

- Classification: Features are fed into classifiers like Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), Support Vector Machine (SVM), or Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) [3].

- Variable Manipulation: The analysis is repeated using different time window durations (e.g., from 0.5s to 4s) for the EEG data following the cue.

- Outcome Measures: The primary measures are classification accuracy and false positive rate for each time window. System responsiveness is defined by the window duration itself. The optimal window is identified as the one offering a favorable compromise, typically found to be 1-2 seconds [3].

Protocol: Validating BCI for Stroke Rehabilitation Training

This protocol outlines a clinical validation study, as seen in [4], which achieved high classification accuracy in stroke patients.

- Objective: To assess the efficacy and classification accuracy of a MI-BCI system coupled with Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) for motor rehabilitation in stroke patients.

- Population: Chronic stroke patients (3+ months post-stroke) with upper limb deficits, excluding those with intense spasticity or cognitive disorders [4].

- System Setup: A high-density 64-channel EEG system with active electrodes is used. FES electrodes are placed on the forearm muscles to elicit hand opening upon stimulation [4].

- Paradigm & Feedback: Patients undergo multiple training sessions. In each trial, they imagine moving their affected hand. The decoded EEG signal provides two types of real-time, closed-loop feedback:

- Data Processing: EEG data is filtered (0.5-30 Hz), and the CSP algorithm is used for spatial filtering before classification with LDA [4].

- Outcome Measures: The primary performance metric is classification accuracy per session. Secondary measures include changes in motor function scales to track clinical improvement [4].

Visualizing BCI Workflows and Performance Trade-offs

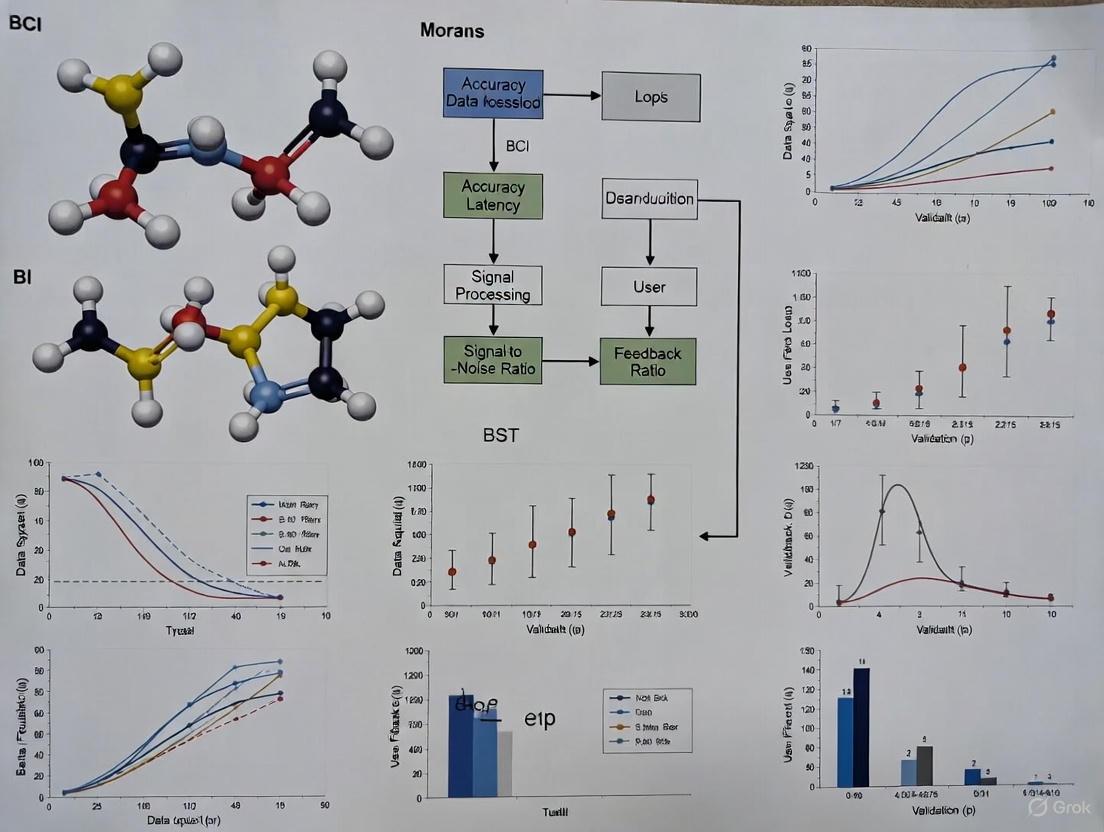

BCI Signal Processing and Classification Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard signal processing chain in a BCI system, from acquisition to application control.

The Performance Trade-Off Triangle in BCI Design

A fundamental challenge in BCI design is the interconnected trade-off between three key performance aspects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for BCI Research

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for BCI Experimentation

| Item | Function / Relevance |

|---|---|

| High-Density EEG System (e.g., 64-channel) | Gold-standard for non-invasive signal acquisition; provides sufficient spatial sampling for algorithms like CSP [4]. |

| Active EEG Electrodes | Improve signal-to-noise ratio by reducing interference, which is critical for detecting subtle ERD/ERS patterns [4]. |

| Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) Algorithm | A foundational spatial filtering technique that enhances the separability of motor imagery classes for feature extraction [3] [4]. |

| Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) | A robust, computationally efficient classifier often used as a benchmark in BCI studies due to its strong performance [3] [4]. |

| Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) Device | Provides contingent somatosensory feedback in closed-loop rehabilitation paradigms, reinforcing neural plasticity [4]. |

| MOABB (Mother of All BCI Benchmarks) | An open-source software framework for the reproducible benchmarking and comparison of BCI algorithms across numerous public datasets [6]. |

| 2-chloro-N-phenylaniline | 2-chloro-N-phenylaniline | High Purity | For Research Use |

| N-Trimethylsilyl-N,N'-diphenylurea | N-Trimethylsilyl-N,N'-diphenylurea|CAS 1154-84-3 |

Evaluating BCI performance requires moving beyond a single-metric focus. As the data shows, a system with 95% accuracy is impractical for real-world wheelchair control if its latency is 4 seconds or its false positive rate is high [3]. The future of BCI validation lies in multi-dimensional metrics that encompass algorithmic accuracy (e.g., from benchmarks like MOABB) [6], hardware efficiency (power-per-channel) [2], and user-centric performance (responsiveness, false positive rate) [3]. For researchers and clinicians, selecting a BCI system must be guided by the specific application, prioritizing a balance of these factors to ensure that laboratory successes translate into genuine real-world utility.

The performance of Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) systems is quantitatively assessed through a triad of interdependent metrics: classification accuracy, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and information transfer rate (ITR). These metrics collectively define the efficacy, efficiency, and practical viability of BCI technologies across diverse applications, from clinical rehabilitation to assistive communication devices. Classification accuracy measures the system's precision in correctly interpreting user intentions from neural signals, serving as the foundational indicator of decoding reliability [7]. Signal-to-noise ratio quantifies the purity of the recorded neural signal against background interference, directly influencing the achievable accuracy and stability of the system [8]. Information transfer rate represents the ultimate measure of practical utility, quantifying the speed of communication in bits per unit time by integrating both accuracy and the number of available choices [9] [10].

The relationship between these metrics forms the core of BCI performance optimization. High SNR enables higher classification accuracy, while both factors directly contribute to achieving superior ITR. However, this relationship often involves critical trade-offs, particularly in real-world applications where non-invasive systems face inherent limitations in signal quality and processing speed. Understanding these metrics and their interactions is essential for researchers and clinicians to evaluate technological advancements, select appropriate paradigms for specific applications, and drive the field toward more reliable and deployable neurotechnologies [11].

Metric Analysis and Comparative Performance

Classification Accuracy

Classification accuracy represents the percentage of correct classifications made by a BCI system when discerning user intents or commands. It is the most direct measure of a system's decoding reliability and is calculated as the ratio of correctly identified trials to the total number of trials. Accuracy is influenced by multiple factors, including signal quality, feature extraction efficacy, and the classification algorithm employed [7].

Different BCI paradigms and algorithmic approaches yield substantially different accuracy levels. Recent advances in deep learning have pushed accuracy boundaries, particularly for complex tasks. The table below summarizes typical accuracy ranges across various approaches:

Table 1: Classification Accuracy Across BCI Paradigms and Methods

| BCI Paradigm/Model | Classification Accuracy Range | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Motor Imagery (Traditional ML) | 80-90% (LDA) [9] | Lower computational demand, established methodology |

| Motor Imagery (Deep Learning) | 90-98% (CNN/Transformer) [9] [8] | Handles complex patterns, requires more data and computation |

| SSVEP (CBAM-CNN) | Up to 98.13% [12] | High-performance visual paradigm, uses attention mechanisms |

| P300 Speller | ~80% (with limited trials) [13] | Requires multiple trial averaging for higher accuracy |

| Auditory BCI | Varies with paradigm [10] | Lower accuracy than visual paradigms but more suitable for specific applications |

For motor imagery tasks, traditional machine learning algorithms like Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) typically achieve 80-90% accuracy, while modern deep learning approaches, including Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Transformer-based models, reach 90-98% accuracy [9]. These advanced architectures excel at capturing complex spatial-temporal patterns in EEG data, with CNN-Transformer hybrids showing particular promise by complementing spatial inductive biases with long-range temporal modeling capabilities [8].

Steady-State Visual Evoked Potential (SSVEP) systems achieve some of the highest accuracy levels, with the CBAM-CNN method reporting up to 98.13% accuracy by leveraging multi-subfrequency band analysis and convolutional block attention modules to enhance feature representation [12]. In contrast, P300-based systems face the challenge of low single-trial SNR, often requiring averaging across multiple trials to achieve acceptable accuracy, which consequently reduces communication speed [13].

Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR)

Signal-to-Noise Ratio quantifies the strength of the target neural signal relative to background noise and interference. In BCI contexts, SNR is particularly challenging due to the inherently weak nature of neural signals, especially in non-invasive approaches like EEG, where signals must pass through the skull and are contaminated by various biological and environmental artifacts [11].

SNR directly determines the feasibility of detecting specific neural patterns and correlates strongly with achievable classification accuracy. The table below compares SNR characteristics across recording modalities:

Table 2: SNR Characteristics Across BCI Recording Modalities

| Recording Modality | SNR Characteristics | Impact on BCI Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Invasive (ECoG/Intracortical) | Highest SNR [11] | Enables complex control (robotic arms, speech decoding) |

| Partially Invasive (Stentrode) | Moderate-High SNR [11] | Balance between signal quality and surgical risk |

| Non-Invasive (EEG) | Lowest SNR [11] | Limits classification accuracy and ITR |

| Functional Ultrasound (fUS) | Emerging modality [11] | Shows promise for chronic applications |

Advanced signal processing techniques are employed to enhance SNR, including spatial filtering methods like Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) and beamforming, which selectively filter out noise and artifacts [9]. Spectral analysis techniques such as Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and wavelet analysis help identify the most informative frequency bands, while artifact removal methods including Independent Component Analysis (ICA) and regression analysis further improve signal quality [9].

Recent transformer-based approaches have demonstrated capability in improving SNR through denoising applications. Diffusion-transformer hybrids show particularly strong performance in signal-level metrics, though the link to direct task benefit requires further standardization and validation [8].

Information Transfer Rate (ITR)

Information Transfer Rate represents the amount of information communicated per unit time, typically measured in bits per minute (bpm) or bits per second (bps). ITR represents the most comprehensive metric of BCI performance as it incorporates both classification accuracy and speed, calculated using the following formula that accounts for the number of possible classes and trial duration [9] [10].

ITR provides a standardized measure for comparing BCI systems across different paradigms and experimental configurations. Current ITR achievements vary significantly based on the recording technique and paradigm used:

Table 3: Information Transfer Rate Comparisons

| BCI Type/Paradigm | ITR Performance | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Invasive BCI | ~100 bpm [9] | Highest performance, requires surgical implantation |

| Non-Invasive SSVEP | Up to 503.87 bits/min [12] | High performance for visual paradigms |

| Non-Invasive MI | 10-50 bpm [9] | Moderate performance, requires user training |

| Auditory BCI (Traditional) | ~10 bits/min [10] | Lower performance but valuable for specific applications |

| Auditory BCI (Advanced) | >17 bits/min (avg), >33 bits/min (best subject) [10] | Improved paradigm with overlapping stimulus presentation |

Invasive BCI systems utilizing ECoG or intracortical recordings achieve the highest ITRs, reaching approximately 100 bpm, enabling complex control of robotic arms and communication devices [9]. Non-invasive systems typically achieve lower ITRs, with EEG-based motor imagery systems ranging from 10-50 bpm [9]. SSVEP paradigms currently lead in non-invasive ITR performance, with the CBAM-CNN method reaching a maximum of 503.87 bits/min by effectively leveraging short-time window signals and attention mechanisms [12].

Auditory BCIs have traditionally lagged behind visual paradigms due to the sequential nature of auditory stimulus presentation. However, recent innovations using overlapping stimulus presentation and auditory attention decoding have demonstrated significant improvements, with average ITRs exceeding 17 bits/min and the best subject surpassing 33 bits/min [10].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Evaluation Frameworks

Robust experimental protocols are essential for meaningful comparison of BCI metrics across studies. Standardized frameworks address critical methodological challenges including data preprocessing consistency, appropriate train-test splits, and computational efficiency reporting [8].

The BCIC IV 2a and 2b datasets have emerged as the most widely adopted benchmarks for motor imagery BCI research, enabling direct comparison across algorithms [8]. Consistent evaluation protocols should employ fixed train-test partitions, transparent preprocessing pipelines, and mandatory reporting of key parameters including FLOPs, per-trial latency, and acquisition-to-feedback delay to ensure real-time viability [8].

For SSVEP paradigms, the Tsinghua University and Inner Mongolia University of Technology datasets provide standardized evaluation platforms. Critical protocol parameters include stimulus presentation time, number of trials, and inter-stimulus intervals, which directly impact both accuracy and ITR measurements [12].

Deep Learning Architectures for Enhanced Performance

Recent advances in deep learning have introduced sophisticated architectures that simultaneously address multiple performance metrics. The following diagram illustrates a typical hybrid deep learning workflow for BCI signal processing:

BCI Deep Learning Pipeline

The CBAM-CNN architecture exemplifies modern BCI signal processing approaches, incorporating multi-subfrequency band analysis (7-16Hz, 15-31Hz, 23-46Hz, and 7-50Hz) to comprehensively capture harmonic components of SSVEP signals [12]. The Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) sequentially applies channel and spatial attention mechanisms to adaptively refine feature maps, enhancing SNR and discriminative power [12].

Transformer-based architectures have demonstrated significant improvements in motor imagery decoding by capturing long-range temporal dependencies through self-attention mechanisms. When combined with CNNs in hybrid architectures, transformers complement spatial inductive biases with global temporal context, achieving performance gains of approximately 5-10 percentage points over conventional approaches in controlled benchmarks [8].

Novel Paradigm Design

Innovative paradigm design has proven instrumental in overcoming inherent limitations of traditional BCI approaches. For SSVEP systems, frequency-modulated stimuli have successfully addressed the critical trade-off between user comfort and system performance. By utilizing a high-frequency carrier (e.g., 100Hz) modulated at a lower frequency (e.g., 80Hz), these paradigms elicit SSVEP responses at the difference frequency (20Hz) while significantly reducing visual fatigue and discomfort associated with traditional low-frequency flickering [14].

In auditory BCI, the traditional constraint of sequential stimulus presentation has been overcome through overlapping auditory streams with negative inter-stimulus intervals. This approach reduces presentation duration by 2.5x compared to conventional auditory paradigms while maintaining decodable neural responses, enabling significantly higher ITRs without compromising classification accuracy [10].

Research Reagents and Experimental Tools

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for BCI Experimentation

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| EEG Acquisition Systems | g.tec g.HIamp, Brain Products GmbH [10] [15] | High-quality neural signal recording with multiple channels |

| Stimulus Presentation | Custom LED arrays [14], Text-to-Speech APIs [10] | Precise control of visual/auditory stimuli timing and parameters |

| Standardized Datasets | BCIC IV 2a/2b [8], Tsinghua University SSVEP [12] | Benchmark comparison and algorithm validation |

| Signal Processing Toolboxes | EEGLAB, BCILAB, OpenVibe | Preprocessing, feature extraction, and visualization |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch | Implementing CNN, Transformer, and hybrid architectures |

| Spatial Filtering Algorithms | Common Spatial Patterns (CSP), Beamforming | Enhancing SNR through optimal spatial projections |

| Classification Algorithms | LDA, SVM, CNN, Transformer [9] [8] | Translating neural features into device commands |

| Performance Validation Tools | Custom ITR scripts, Statistical testing frameworks | Quantifying and comparing system performance |

The selection of appropriate research tools significantly influences the reliability and reproducibility of BCI studies. High-quality EEG acquisition systems with adequate channel counts and sampling rates form the foundation of reliable data collection [10]. Standardized datasets enable direct comparison across algorithms and institutions, with the BCIC IV 2a/2b datasets being particularly prevalent in motor imagery research [8].

Deep learning frameworks have become essential for implementing state-of-the-art architectures, with TensorFlow and PyTorch enabling the development of complex models including CNN-Transformer hybrids and attention mechanisms [8] [12]. Custom stimulus presentation systems, particularly for SSVEP research, allow precise temporal control of visual stimuli, which is critical for eliciting robust neural responses [14].

The three core metrics of classification accuracy, SNR, and ITR form an interconnected framework for evaluating BCI performance. Improvements in SNR directly enable higher classification accuracy, while both metrics contribute to enhanced ITR. However, practical system design often involves navigating trade-offs between these metrics, particularly when considering user comfort, clinical applicability, and real-world usability.

Future advancements in BCI technology will likely focus on several key areas: developing more robust signal processing algorithms that maintain performance across sessions and subjects; creating adaptive systems that continuously optimize parameters based on user state and performance; and establishing standardized evaluation protocols that enable meaningful comparison across studies [8]. The integration of multimodal approaches, combining complementary paradigms such as visual and auditory BCIs, may overcome limitations of individual systems and provide more flexible communication channels for diverse applications [10].

As BCI technology transitions from laboratory demonstrations to real-world applications, the comprehensive assessment of classification accuracy, SNR, and ITR will remain essential for driving meaningful progress. By understanding the relationships and trade-offs between these metrics, researchers can develop next-generation neurotechnologies that balance performance with practical constraints, ultimately expanding communication and control options for individuals with neurological disorders.

Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technologies represent a revolutionary advancement in neural engineering, creating direct communication pathways between the brain and external devices. These systems are broadly categorized into three distinct technological approaches: invasive (implanted directly into brain tissue), non-invasive (recording from the scalp surface), and partially invasive (implanted within the skull but not penetrating brain tissue). The choice between these technological pathways carries profound implications for system performance, clinical applicability, and user experience. Within research focused on BCI system performance validation metrics, a critical challenge persists: establishing standardized, comparable evaluation frameworks that can objectively benchmark these fundamentally different technological approaches. Performance assessment is further complicated by the fact that multiple incommensurable metrics are currently used across studies, hindering direct comparison and technological progress [16].

This comparison guide provides an objective analysis of performance characteristics across invasive, non-invasive, and partially invasive BCI technologies. By synthesizing current experimental data, detailing methodological protocols, and presenting standardized performance metrics, this work aims to establish a rigorous foundation for cross-technology benchmarking within BCI validation research.

Fundamental Technical Specifications

The core BCI technologies differ fundamentally in their signal acquisition methodologies, which directly determines their performance characteristics across multiple dimensions. Invasive systems record neural activity at the source, providing unparalleled signal resolution but requiring neurosurgical implantation. Non-invasive systems, primarily electroencephalography (EEG), measure electrical activity from the scalp surface, offering safety and accessibility but with reduced signal fidelity. Partially invasive approaches, including electrocorticography (ECoG), occupy an intermediate position, recording from the cortical surface with better resolution than non-invasive methods but less surgical risk than fully invasive implants [17].

Table 1: Fundamental Technical Specifications of BCI Modalities

| Performance Characteristic | Invasive BCI | Non-Invasive BCI | Partially Invasive BCI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Micrometer scale (single neurons) | Centimeter scale | Millimeter to centimeter scale |

| Temporal Resolution | Very High (<1 ms) | High (~1-5 ms) | Very High (<1 ms) |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | High | Low to Moderate | Moderate to High |

| Typical Signals Recorded | Action potentials, Local Field Potentials | EEG rhythms, ERPs, SSVEP | ECoG, Local Field Potentials |

| Risk Profile | High (surgical risk, tissue response) | Very Low | Moderate (surgical risk) |

| Primary Clinical Applications | Severe paralysis, neuroprosthetics | Neurorehabilitation, communication, epilepsy monitoring | Epilepsy focus localization, cortical mapping |

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

Experimental data from controlled studies and commercial systems reveals consistent performance patterns across BCI modalities. Classification accuracy and information transfer rate (ITR) serve as key metrics for comparing practical performance. For motor imagery paradigms, invasive systems typically achieve the highest performance levels, with non-invasive systems showing more variability across users and sessions [18] [19].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics Across BCI Modalities

| BCI Type | Paradigm/Application | Typical Accuracy Range | Information Transfer Rate (bits/min) | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive | Motor Imagery (Cursor Control) | 85-95%+ | ~100+ | Surgical risk, signal stability over time |

| Non-Invasive (EEG) | Motor Imagery (2-class) | 68.8-85.3% [18] [19] | ~20-40 | Cross-session variability, low signal-to-noise ratio |

| Non-Invasive (EEG) | P300 Speller | 70-90% | ~25-45 | Visual fatigue, requires attention |

| Partially Invasive (ECoG) | Motor Imagery | 80-95% | ~50-100 | Limited spatial coverage, surgical procedure required |

Cross-session performance variability presents a particular challenge for non-invasive systems. One comprehensive study of 25 subjects across 5 sessions demonstrated that within-session classification accuracy for motor imagery reached 68.8%, but this decreased to 53.7% in cross-session testing without adaptation techniques. With cross-session adaptation, performance recovered to 78.9%, highlighting both the challenge and potential solutions for non-invasive BCI reliability [18].

Experimental Protocols for BCI Performance Validation

Standardized Evaluation Methodologies

Robust performance validation requires standardized experimental protocols that account for the unique characteristics of each BCI modality. For non-invasive systems using motor imagery paradigms, a typical protocol involves cue-based trials with precise timing structures. In one representative study with 62 participants, each trial lasted 7.5 seconds, beginning with a 1.5-second cue presentation period followed by a 4-second motor imagery period and a 2-second rest period [19]. Participants performed multiple sessions across different days, with each session containing approximately 200 trials for two-class paradigms (left vs. right hand) [19].

Performance evaluation must distinguish between offline and online testing protocols. Offline analysis involves post-processing of recorded data to optimize signal processing pipelines and classification algorithms. However, online closed-loop testing represents the "gold standard" for practical performance assessment, as it evaluates system performance in real-time with user feedback, more accurately reflecting real-world usability [20]. Studies consistently show discrepancies between offline classification accuracy and online performance, emphasizing the necessity of online validation for meaningful performance metrics [20].

Performance Metrics and Reporting Standards

The BCI research community has identified critical limitations in current performance reporting practices. A review of 72 BCI studies revealed 12 different combinations of performance metrics, creating significant challenges for cross-study comparisons [16]. To address this, standardized metric frameworks have been proposed:

- Level 1 Metrics: Measure performance at the output of the BCI Control Module, which translates brain signals into logical control output. Recommended metrics include Mutual Information or Information Transfer Rate (ITR), which represent information throughput independent of interface design [16].

- Level 2 Metrics: Evaluate performance at the Selection Enhancement Module, which translates logical control to semantic meaning. The BCI-Utility metric is recommended as it accounts for performance enhancements like error correction and word prediction [16].

- Level 3 Metrics: Assess the impact of the BCI system on the user's quality of life, communication efficacy, and overall experience, though these are less standardized [16].

Reporting should include both Level 1 and Level 2 metrics, supplemented by interface-specific information to enable comprehensive comparison across different BCI technologies and system configurations [16].

Figure 1: Hierarchical Framework for BCI Performance Metrics

Critical Methodological Considerations in BCI Benchmarking

Cross-Validation and Temporal Dependencies

Performance validation in BCI research requires careful attention to methodological decisions, particularly in data splitting strategies for cross-validation. Recent research demonstrates that the choice of cross-validation scheme significantly impacts reported classification accuracy, potentially biasing conclusions about system performance. Studies across three independent EEG datasets showed that classification accuracies of Riemannian minimum distance classifiers varied by up to 12.7% with different cross-validation implementations, while Filter Bank Common Spatial Pattern based linear discriminant analysis varied by up to 30.4% [21].

The critical methodological distinction lies in whether cross-validation respects the block structure of data collection. When train and test subsets are split without regard to temporal structure, accuracy metrics can become artificially inflated due to temporal dependencies in the data rather than genuine class discrimination [21]. These dependencies arise from multiple sources including gradual changes in electrode impedance, participant fatigue, and physiological adaptations. Proper cross-validation must therefore maintain temporal separation between training and testing data, ideally testing on completely separate recording sessions to obtain realistic performance estimates [21].

Cross-Session and Cross-Subject Variability

A fundamental challenge in BCI performance validation is the significant variability in neural signals across sessions and between subjects. This variability is particularly pronounced in non-invasive systems, where performance degradation in cross-session testing can be substantial. One comprehensive study collecting data across 5 different days from 25 subjects found that while within-session classification accuracy reached 68.8%, this decreased to 53.7% in cross-session testing without adaptation [18]. This highlights the critical importance of multi-session experimental designs for obtaining realistic performance estimates.

The same study demonstrated that adaptation techniques can successfully address this challenge, with cross-session adaptation improving accuracy to 78.9% [18]. These findings emphasize that robust BCI benchmarking requires evaluation across multiple sessions rather than single-session performance reports. Similar considerations apply to cross-subject validation, where models trained on one group of users typically show reduced performance when applied to new users without calibration or adaptation.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Robust BCI Benchmarking

Public Datasets for Benchmarking

Several high-quality, publicly available datasets enable standardized benchmarking of BCI algorithms across different technology modalities. These resources are essential for reproducible research and comparative performance assessment:

- WBCIC-MI Dataset: Comprehensive MI dataset from 62 healthy participants across three recording sessions, including both two-class (left/right hand) and three-class (left/right hand, foot) paradigms. Provides high-quality EEG data with average classification accuracy of 85.32% for two-class tasks using EEGNet [19].

- Multi-day EEG Dataset: Contains data from 25 subjects across 5 different days (2-3 days apart), specifically designed to study cross-session variability. Each session includes 100 trials of left-hand and right-hand motor imagery [18].

- BCI Competition IV Datasets: Standardized benchmarks including Dataset 2a (22-electrode EEG motor imagery from 9 subjects, 4 classes) and Dataset 2b (3-electrode EEG motor imagery from 9 subjects, 2 classes) [22].

- High-Gamma Dataset: 128-electrode dataset from 14 subjects with approximately 1,000 four-second trials of executed movements across 4 classes [22].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for BCI Performance Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Data Acquisition Systems | Neuracle EEG Systems, OpenBCI Headsets, Brain Products ActiChamp | High-quality neural signal acquisition with precise synchronization |

| Electrode Technologies | Wet Ag/AgCl electrodes, Dry electrodes, Multielectrode arrays | Signal transduction with optimized contact impedance and stability |

| Signal Processing Tools | EEGLAB, BCILAB, MNE-Python, FieldTrip | Preprocessing, artifact removal, and feature extraction |

| Classification Algorithms | FBCSP, Riemannian Geometry, EEGNet, DeepConvNet | Intent decoding from neural features with cross-session robustness |

| Performance Metrics Packages | ITR calculators, BCI-Utility implementations | Standardized performance assessment and cross-study comparison |

| Stimulus Presentation Platforms | Psychtoolbox, OpenSesame, Presentation | Precise timing-controlled paradigm delivery |

The benchmarking of BCI technologies across invasive, non-invasive, and partially invasive approaches reveals distinct performance characteristics that must be weighed against practical considerations of risk, accessibility, and usability. Invasive systems provide superior signal quality and information throughput for severe disabilities where clinical justification warrants surgical intervention. Non-invasive systems offer broader accessibility with progressively improving performance through advanced signal processing and adaptation techniques. Partially invasive approaches represent a promising middle ground, though further development is needed to fully establish their risk-benefit profile.

Critical to future progress is the adoption of standardized performance validation methodologies that include structured cross-validation, multi-session testing, and comprehensive metric reporting across Levels 1, 2, and 3. The BCI research community must prioritize transparent reporting of experimental protocols, particularly regarding data splitting procedures and cross-validation schemes, to enable meaningful comparisons across studies and technology modalities. As the field progresses toward practical applications, these standardized benchmarking approaches will be essential for guiding technology development, informing clinical decisions, and ultimately realizing the transformative potential of brain-computer interfaces across medical, assistive, and consumer domains.

In the field of brain-computer interfaces (BCI), the evaluation paradigm is undergoing a critical shift. While classification accuracy and information transfer rate remain valuable technical benchmarks, a growing body of research emphasizes that these metrics alone are insufficient for evaluating systems designed for clinical and assistive applications. The ultimate measure of a BCI's success in these domains is its ability to produce meaningful, functional improvements in users' daily lives and rehabilitation outcomes. This comparison guide examines how different BCI approaches translate technical performance into functional gains, providing researchers and clinicians with evidence-based frameworks for evaluating these transformative technologies.

The limitation of accuracy-centric evaluation is particularly evident in motor rehabilitation, where even systems with moderate classification accuracy can produce significant functional improvements when properly integrated with assistive devices. As [23] demonstrates in their meta-analysis, BCI-controlled functional electrical stimulation (FES) training shows only moderate effect sizes for signal classification (SMD = 0.50) but generates clinically important improvements in upper limb function after stroke. This discrepancy between technical and functional outcomes underscores the necessity of a more nuanced evaluation framework that prioritizes real-world impact over pure algorithmic performance.

Comparative Analysis of BCI Approaches and Functional Outcomes

Different BCI paradigms offer distinct pathways to functional improvement, each with characteristic strengths and limitations for clinical implementation. The table below provides a systematic comparison of major BCI approaches based on their functional outcomes, technical requirements, and evidence levels.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of BCI Approaches for Clinical and Assistive Applications

| BCI Approach | Primary Clinical Application | Reported Functional Outcomes | Technical Accuracy Metrics | Evidence Level & Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor Imagery (MI) BCI with FES | Upper limb stroke rehabilitation | Significant improvement in FMA-UE (SMD=0.50) [23]; Effective in both subacute and chronic phases [23] | Moderate effect size (SMD=0.50); Improved with adjustable thresholds [23] | 10 RCTs, 290 patients; Strong evidence for stroke [23] |

| Steady-State Motion Visual Evoked Potential (SSMVEP) | Communication systems for severe disabilities | High accuracy with reduced fatigue; Enhanced user comfort [24] | 83.81% ± 6.52% accuracy with bimodal paradigm [24] | Laboratory studies with healthy and disabled populations [24] |

| Motor Attempt (MA) BCI with Neurofeedback | Motor neurorehabilitation | Statistically significant FMA improvements; Correlation with training dose [25] | Variable classification accuracy; Requires movement attempt [25] | 23 studies, primarily stroke; Emerging evidence [25] |

| Action Observation (AO) BCI | Stroke rehabilitation | Potentially superior to MI for upper limb function (SMD=0.73 vs 0.41) [23] | Requires different decoding approaches than MI [23] | Limited direct comparisons; Promising early results [23] |

Motor Imagery BCI with Functional Electrical Stimulation

The combination of motor imagery BCI with functional electrical stimulation represents one of the most thoroughly studied approaches for motor rehabilitation. This closed-loop system enables patients to initiate movement attempts through motor imagery, which then triggers FES to produce actual limb movement, creating a reinforced sensorimotor loop.

Functional Efficacy: The meta-analysis by [23] demonstrates that BCI-FES training produces statistically significant improvements in upper limb function as measured by the Fugl-Meyer Assessment for Upper Extremity (FMA-UE). The moderate effect size (SMD=0.50, 95% CI: 0.26–0.73) reflects consistent clinical benefits across multiple studies. Importantly, subgroup analyses revealed that these functional improvements occurred regardless of stroke chronicity, with similar effect sizes in both subacute (SMD=0.56) and chronic (SMD=0.42) populations.

Technical Considerations: A critical finding for researchers designing clinical BCI studies is that systems with adjustable thresholds before training significantly enhanced motor function compared to fixed-threshold systems (SMD=0.55 vs 0.43). This highlights the importance of personalized calibration protocols rather than one-size-fits-all technical approaches.

Steady-State Paradigms for Assistive Communication

For individuals with severe motor disabilities, SSVEP and SSMVEP paradigms offer alternative communication pathways that prioritize reliability and reduced fatigue over direct motor restoration.

Fatigue Reduction: Conventional SSVEP paradigms often cause significant visual fatigue due to intense flickering stimuli. The SSMVEP approach developed by [24] addresses this limitation by integrating motion and color stimuli, creating a more sustainable interface. Their bimodal motion-color paradigm achieved 83.81% classification accuracy while simultaneously reducing subjective fatigue reports and objective physiological markers of strain.

Implementation Considerations: This enhanced performance stemmed from activating both the dorsal stream (motion-sensitive M-pathway) and ventral stream (color-sensitive P-pathway) in the visual system. Researchers should note that the optimal area ratio between rings and background was 0.6, providing a specific parameter for future implementations.

Motor Attempt vs. Motor Imagery in Neurofeedback

The distinction between motor attempt (MA) and motor imagery (MI) represents a fundamental design choice with significant implications for functional outcomes in neurorehabilitation.

Physiological Plausibility: As [25] explains, motor attempt may produce more effective neuroplasticity because it "maximizes the similarities between the brain-state used to control the BCI and the functional task," potentially leading to more persistent therapeutic effects. This approach activates sensorimotor networks more comprehensively than imagery alone, though it requires some residual movement capability.

Evidence Base: While direct comparisons are limited, a review of 23 studies found that MA approaches showed a positive trend toward superior outcomes compared to MI (p=0.07). Additionally, FMA outcomes were positively correlated with training dose in MA paradigms, suggesting a dose-response relationship that reinforces their therapeutic validity.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

BCI-FES Protocol for Upper Limb Rehabilitation

The most consistent functional outcomes emerge from standardized protocols implemented in randomized controlled trials. The following methodology represents a consensus approach derived from multiple high-quality studies:

Participant Characteristics: Studies typically include adults with unilateral upper limb paresis following stroke, regardless of specific demographic factors. Research by [23] demonstrates efficacy across both subacute (<6 months) and chronic (>6 months) phases, supporting broad inclusion criteria.

EEG Acquisition Parameters:

- Electrode Placement: According to the international 10-20 system, with focus on C3, C4, Cz positions over sensorimotor cortex

- Signal Processing: Sampling rates typically 250-1000 Hz, bandpass filtering 0.1-40 Hz, notch filtering at 50/60 Hz

- Feature Extraction: Event-related desynchronization (ERD) in mu (8-13 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) rhythms during motor imagery/attempt

FES Integration Protocol:

- Stimulation Timing: FES triggered when ERD power decreases below individualized threshold

- Stimulation Parameters: Typically 20-40 mA amplitude, 20-50 Hz frequency, 200-400 μs pulse width

- Session Structure: 45-60 minute sessions, 3-5 times weekly for 4-8 weeks

Functional Assessment Schedule:

- Primary Outcome: Fugl-Meyer Assessment for Upper Extremity (FMA-UE)

- Secondary Outcomes: Action Research Arm Test (ARAT), Box and Block Test, grip strength

- Assessment Timing: Pre-intervention, post-intervention, and 3-month follow-up

Table 2: Key Reagents and Research Materials for BCI Rehabilitation Studies

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Acquisition | g.USBamp (g.tec), ActiveTwo (Biosemi), EEG headsets | Records neural activity with necessary resolution | Ensure compatibility with chosen paradigm (MI, SSVEP, etc.) [24] |

| Electrode Types | Ag/AgCl sintered electrodes, Gold-coated electrodes, Multichannel wet/dry electrodes | Captures brain signals with appropriate impedance | Balance signal quality with user comfort for extended sessions [25] |

| Stimulation Devices | Functional electrical stimulators, Neuromodulation equipment | Provides peripheral feedback to close sensorimotor loop | Synchronization with EEG system is critical [23] |

| Software Platforms | EEGNet, BCILAB, OpenVibe, Custom MATLAB/Python scripts | Signal processing, feature extraction, classification | Select based on paradigm compatibility and customization needs [24] |

| Assessment Tools | Fugl-Meyer Assessment, Action Research Arm Test | Quantifies functional outcomes | Standardized administration essential for valid comparisons [23] [25] |

SSMVEP Protocol for Assistive Communication

For communication-focused applications, SSMVEP protocols prioritize stability and user comfort over extended operation periods:

Visual Stimulation Design:

- Stimulus Type: Newton's rings with expanding/contracting motion

- Color Combination: Red and green with equal luminance to minimize flicker

- Frequency Range: 5-15 Hz for optimal balance between SNR and fatigue

- Display Considerations: AR glasses for immersive presentation

EEG Recording Setup:

- Electrode Positions: Po3, Poz, Po4, O1, Oz, O2 (occipital-parietal coverage)

- Reference Scheme: Linked ears or average reference

- Sampling Rate: 1200 Hz with online filtering

Signal Processing Pipeline:

- Preprocessing: 8th-order Butterworth bandpass filter (2-100 Hz), 4th-order notch filter (48-52 Hz)

- Feature Extraction: Fast Fourier Transform for frequency domain analysis

- Classification: EEGNet deep learning algorithm or canonical correlation analysis

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The functional efficacy of BCIs depends critically on their engagement with specific neural pathways. The diagram below illustrates the core signal processing workflow common to most clinical BCI systems, highlighting the transformation of neural signals into functional outcomes.

Pathway Engagement for Different Paradigms:

Motor Imagery/Attempt Systems: These primarily engage the sensorimotor network, including primary motor cortex (M1), supplementary motor area (SMA), and parietal regions. Effective systems produce event-related desynchronization (ERD) in mu (8-13 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) rhythms over contralateral sensorimotor areas during movement intention.

SSVEP/SSMVEP Systems: These paradigms activate the visual pathways from retina through lateral geniculate nucleus to visual cortex (V1, V2, V4, V5/MT). The bimodal motion-color approach described by [24] simultaneously engages both the dorsal stream (motion processing via V5/MT) and ventral stream (color processing via V4), creating stronger and more fatigue-resistant responses.

Neurofeedback Systems: These leverage the brain's inherent capacity for plasticity through operant conditioning. As [25] explains, successful neurofeedback enables users to "learn to reinforce the modulations that were deemed most successful" through continuous feedback loops, ultimately producing functional reorganization in targeted networks.

The evidence examined in this comparison guide supports a fundamental conclusion: comprehensive validation of clinical and assistive BCIs requires multidimensional assessment frameworks that give equal weight to functional outcomes and technical performance. Accuracy metrics remain necessary but insufficient indicators of real-world value.

Several key principles emerge for researchers designing future studies:

First, paradigm selection should align with specific clinical goals – motor restoration versus communication assistance – with recognition that different technical approaches produce distinct functional benefit profiles. The superior upper limb outcomes from BCI-FES for stroke rehabilitation (SMD=0.50) [23] demonstrate how biologically-plausible sensorimotor loop closure drives recovery.

Second, standardized functional assessment is imperative for cross-study comparisons. The consistent use of FMA-UE across 13 studies analyzed by [23] enabled meaningful meta-analysis, while varied assessment tools complicate evaluation of other paradigms.

Finally, user-centered design factors significantly influence functional efficacy. Reduced fatigue in SSMVEP paradigms [24] and the dose-response relationship in motor attempt training [25] highlight how human factors ultimately determine whether technically sophisticated systems deliver meaningful real-world benefits.

As BCI technologies continue their progression from laboratory demonstrations to clinical tools, embracing these comprehensive evaluation principles will ensure that functional outcomes for patients remain the primary metric of success.

From Signal to Command: Methodologies for Performance Enhancement and Real-World Application

The efficacy of any Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) system is fundamentally constrained by the quality of the neural data upon which it operates. High-quality signal acquisition and rigorous preprocessing form the essential foundation for reliable intent decoding, system validation, and ultimately, clinical translation [20]. Within the context of BCI system performance validation metrics research, data quality directly influences critical evaluation parameters such as information transfer rate (ITR), classification accuracy, and the emerging BCI-Utility metric—a user-centered measure that quantifies the average benefit of a BCI system over trials by considering both accuracy and speed [26]. The transition from analyzing offline data to constructing robust online BCI systems represents a qualitative leap that demands meticulous attention to signal quality at every processing stage [20]. This guide objectively compares techniques and technologies for ensuring neural data integrity, providing researchers with experimental data and methodologies to optimize their systems for practical applications.

Neural Signal Acquisition Modalities and Characteristics

Electroencephalography (EEG) stands as the most widely used non-invasive technique for BCI applications due to its excellent temporal resolution, portability, and relatively low cost [27] [28]. EEG signals represent the electrical activity of the brain measured using electrodes placed on the scalp, with amplitudes typically ranging from 10 to 100 microvolts (μV) and characteristic frequency bands associated with different brain states [27].

- Delta waves (0.5-4 Hz) are associated with deep sleep.

- Theta waves (4-8 Hz) are linked to drowsiness and memory recall.

- Alpha waves (8-13 Hz) dominate during relaxed wakefulness with closed eyes.

- Beta waves (13-30 Hz) relate to active thinking and attention.

- Gamma waves (30-100+ Hz) are involved in higher cognitive functions [27].

While EEG offers millisecond-scale temporal resolution ideal for capturing rapid neural dynamics, its spatial resolution remains limited compared to invasive techniques such as Electrocorticography (ECoG). ECoG, which records electrical activity directly from the cortical surface, provides superior spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio but requires intracranial implantation [29]. The "Podcast" ECoG dataset exemplifies how naturalistic stimuli combined with high-fidelity neural recordings enable sophisticated investigation of cognitive processes like language comprehension [29].

Table 1: Comparison of Neural Signal Acquisition Technologies

| Technology | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Invasiveness | Key Applications in BCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEG | Low (cm) | Excellent (ms) | Non-invasive | P300 spellers, MI-based BCIs, SSVEP systems [28] [27] |

| ECoG | High (mm) | Excellent (ms) | Invasive (intracranial) | High-performance communication, natural language processing studies [29] |

| Hybrid Clinical Grids | Very High (<1 mm) | Excellent (ms) | Invasive (intracranial) | Detailed mapping of neural activity in clinical/research settings [29] |

Systematic EEG Preprocessing Pipeline

Raw neural signals are invariably contaminated by various artifacts and noise sources that must be effectively mitigated before further analysis. The following workflow outlines a comprehensive preprocessing pipeline, with each stage detailed in subsequent sections.

EEG Preprocessing and Feature Extraction Pipeline

Data Acquisition and Initial Preprocessing

Proper acquisition is paramount for obtaining high-quality EEG data. This involves using Ag/AgCl electrodes positioned according to standardized systems (10-20, 10-10), proper skin preparation to reduce impedance, and appropriate amplifier settings [27]. Initial preprocessing typically includes:

- Filtering: Bandpass filters (e.g., 0.1-100 Hz) remove low-frequency drift and high-frequency noise, while notch filters (50/60 Hz) suppress power line interference [30] [27].

- Re-referencing: Techniques like common average referencing minimize the influence of reference electrode placement [27].

- Segmentation: Continuous data is divided into epochs or trials time-locked to specific events or stimuli for subsequent analysis [27].

Advanced Artifact Removal Techniques

EEG recordings are prone to physiological artifacts (eye blinks, muscle activity, cardiac signals) and non-physiological artifacts (electrode pops, environmental noise) [27]. Effective artifact removal is crucial for obtaining reliable data.

- Independent Component Analysis (ICA): A widely used blind source separation technique that identifies and removes artifact components while preserving brain activity [27].

- Regression-Based Methods: These subtract artifact templates (e.g., using EOG channels) from the EEG signal [27].

- Automatic Detection and Rejection: Algorithms identify contaminated segments based on signal properties like amplitude thresholds or statistical measures [27].

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Artifact Removal Methods

| Method | Primary Application | Advantages | Limitations | Effectiveness Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICA | Ocular, muscle, cardiac artifacts | Preserves neural activity, no reference channels needed | Computationally intensive, requires manual component inspection | Signal-to-noise ratio improvement, preservation of ERP components [27] |

| Regression-Based | Ocular artifacts | Simple implementation with reference channels | May over-correct and remove neural signals | Reduction in EOG correlation, preservation of task-related activity [27] |

| Automatic Rejection | High-amplitude transients | Simple, fast processing | Data loss, potentially discards usable data | Percentage of rejected trials, post-rejection accuracy [27] |

| Adaptive Filtering | All artifacts with reference signals | Effective with clean reference signals | Requires dedicated reference channels | Signal-to-noise ratio improvement, correlation with reference [27] |

Feature Extraction and Decoding Methodologies

Once cleaned, EEG signals undergo feature extraction to capture discriminative patterns for BCI tasks. Features can be extracted from multiple domains:

- Time-Domain Features: Include event-related potentials (ERPs) like the P300 component—a positive deflection peaking around 300ms after a rare target stimulus—and statistical measures like variance or peak-to-peak amplitude [26] [27].

- Frequency-Domain Features: Power spectral density (PSD) estimates power distribution across frequency bands (delta, theta, alpha, beta, gamma), providing insights into brain states during specific tasks [30] [27].

- Time-Frequency Features: Techniques like wavelet transforms reveal changes in EEG power over time and across frequency bands, highlighting transient brain events [30].

- Nonlinear Features: Measures like entropy, fractal dimension, and Lyapunov exponents quantify the complexity and chaotic properties of EEG signals [27].

Experimental Protocols and Performance Comparison

Protocol 1: SSVEP Classification with Hybrid Methods

Objective: To evaluate the performance of a combined traditional machine learning and deep learning framework for Steady-State Visually Evoked Potential (SSVEP) frequency recognition [31].

Methodology: The study proposed an eTRCA + sbCNN framework that integrates an ensemble Task-Related Component Analysis (eTRCA) algorithm with a sub-band Convolutional Neural Network (sbCNN). After data preprocessing and sub-band filtering, the eTRCA and sbCNN models were trained separately. For classification, their output score vectors were fused through addition, with the frequency corresponding to the maximal summed score selected as the final decision [31].

Results: The hybrid eTRCA + sbCNN framework significantly outperformed either method alone across two benchmark SSVEP datasets (105 total subjects). This demonstrates that combining traditional spatial filtering with deep learning feature learning effectively exploits their complementarity, enhancing classification performance for practical SSVEP-BCI applications [31].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of SSVEP Classification Algorithms

| Algorithm | Average Accuracy (%) | Information Transfer Rate (bits/min) | Key Strengths | Computational Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eTRCA + sbCNN (Hybrid) | Highest reported | Highest reported | Leverages advantages of both ML and DL | High (requires training two models) [31] |

| eTRCA (Traditional ML) | High | High | Strong spatial filtering, robust with limited data | Moderate [31] |

| sbCNN (Deep Learning) | High | High | Automatic feature learning from raw signals | High (requires large training data) [31] |

| CCA | Moderate | Moderate | Simple implementation, no training required | Low [31] |

Protocol 2: P300 Speller Evaluation with BCI-Utility Metric

Objective: To evaluate asynchronous P300 speller systems incorporating abstention and dynamic stopping features using the BCI-Utility metric, which considers both accuracy and efficiency [26].

Methodology: Unlike traditional metrics focusing solely on classification accuracy, the BCI-Utility metric incorporates:

- Probability of correct selection when intended

- Probability of making a selection when intended

- Probability of abstention when intended

- Average time required for selection with dynamic stopping

- Proportion of intended selections versus abstentions [26]

Results: Simulations and real-world data application demonstrated that the BCI-Utility metric increases with any accuracy component improvement and decreases with longer selection times. In many scenarios, shortening the expected time for an intended selection through accurate abstention and dynamic stopping was the most effective way to improve BCI-Utility, highlighting the importance of asynchronous features for practical BCI systems [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Materials and Tools for EEG Acquisition and Processing

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Ag/AgCl Electrodes | Signal acquisition from scalp | Low noise, stable performance; used with conductive gel [27] |

| EEG Amplifier Systems | Signal amplification and digitization | Bandpass filtering (0.16-250 Hz), sampling rates (250-2000 Hz) [29] |

| Electrode Caps/Nets | Standardized electrode placement | Follows 10-20 or 10-10 systems for consistent coverage [27] |

| Conductive Gel/Paste | Reducing skin-electrode impedance | Hypoallergenic formulations for prolonged recordings [27] |

| Forced Aligner Software | Temporal alignment of speech stimuli | Penn Phonetics Lab Forced Aligner for word-onset estimation [29] |

| Notch Filters | Power line interference removal | Digital filters at 50/60 Hz and harmonics [29] |

| ICA Algorithms | Blind source separation for artifact removal | Implementations in EEGLAB, MNE-Python [27] |

| Wavelet Transform Toolboxes | Time-frequency analysis | MATLAB Wavelet Toolbox, Python PyWavelets [30] |

| 3,5-Dibromobenzene-1,2-diamine | 3,5-Dibromobenzene-1,2-diamine | High-Purity Reagent | High-purity 3,5-Dibromobenzene-1,2-diamine for research applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Diiododifluoromethane | Diiododifluoromethane | High-Purity Reagent | RUO | Diiododifluoromethane is a key reagent for organic synthesis & fluorination. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The path from raw neural signals to reliable BCI control is paved with meticulous acquisition practices and sophisticated preprocessing techniques. As evidenced by the experimental data, the choice of processing algorithms—from artifact removal methods to classification approaches—significantly impacts ultimate system performance as measured by both traditional metrics and emerging frameworks like BCI-Utility. The integration of traditional signal processing techniques with modern deep learning methods, as demonstrated in SSVEP classification, shows particular promise for enhancing performance. Furthermore, the adoption of comprehensive evaluation metrics that consider real-world usage scenarios, including asynchronous operation, is crucial for advancing BCI technology from laboratory demonstrations to practical applications that provide genuine utility to end-users. Future developments in this field will continue to depend on rigorous attention to signal quality at every stage of the processing pipeline.

Within the framework of Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) system performance validation metrics research, the processes of feature extraction and selection represent critical determinants of overall system efficacy. These preprocessing stages directly influence classification accuracy, information transfer rate, and real-world applicability of BCI technologies [32] [1]. Feature extraction involves transforming raw, often noisy electrophysiological signals into discriminative representations, while feature selection aims to identify the most relevant characteristics that enhance model performance while reducing computational complexity [33] [32]. The challenging nature of EEG signals—characterized by non-stationarity, low signal-to-noise ratio, and significant inter-subject variability—makes robust feature engineering particularly essential for developing reliable BCI systems [34] [32]. This comprehensive analysis examines current methodologies, performance comparisons, and experimental protocols in feature extraction and selection, providing researchers with validated metrics for BCI system evaluation.

Theoretical Foundations of EEG Feature Extraction

Electroencephalography (EEG) signals contain distinctive patterns of neural activity that can be decoded to infer user intent in BCI systems [33] [1]. These signals are typically categorized by their frequency bands, each associated with different brain states: delta (0.5-4 Hz) in deep sleep, theta (4-8 Hz) in drowsiness, alpha (8-13 Hz) in relaxed wakefulness, mu (8-13 Hz) in motor rest, beta (13-30 Hz) in active concentration, and gamma (30-100 Hz) in higher cognitive processing [33]. Additionally, event-related potentials such as the P300 (a positive deflection occurring approximately 300ms after a stimulus) and steady-state visual evoked potentials (SSVEP) provide reliable neural markers for BCI control [33] [35].

The primary challenge in EEG feature extraction stems from the inherently complex properties of neural signals. EEG data is non-stationary, meaning statistical properties change over time; non-linear, as it arises from complex biological systems; non-Gaussian, failing to follow normal distribution patterns; and non-short form, requiring specialized analysis techniques [32]. These characteristics necessitate sophisticated signal processing approaches to extract meaningful features that accurately represent the underlying neural activity while minimizing the impact of artifacts and noise [32] [36].

Methodological Approaches to Feature Extraction

Domain-Specific Extraction Techniques

Feature extraction methods for EEG signals can be categorized according to the signal domain they operate upon, each offering distinct advantages for capturing relevant neural patterns [32].

Time Domain Features include amplitude-based measurements, morphological characteristics, and event-related potential components. The P300 wave, for instance, represents a positive deflection occurring approximately 300ms after stimulus presentation and is widely utilized in BCI spellers and control systems [33] [35]. Time-domain analysis also encompasses Hjorth parameters (activity, mobility, complexity) and statistical measures like variance, skewness, and kurtosis that describe signal distribution properties [32].

Frequency Domain Features involve transforming signals using methods such as Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to quantify power spectral density across different frequency bands [36]. This approach is particularly valuable for analyzing oscillatory activity in specific frequency ranges, such as sensorimotor rhythms (mu and beta bands) during motor imagery tasks [33] [34]. Power spectral features can capture event-related synchronization (ERS) and desynchronization (ERD), which correspond to the increase or decrease of specific frequency components during cognitive or motor tasks [33].

Time-Frequency Domain Features leverage techniques like Wavelet Transform (WT) and short-time Fourier Transform (STFT) to simultaneously capture temporal and spectral information [32] [36]. These methods are particularly effective for analyzing non-stationary signals where frequency components evolve over time, such as during transitions between mental states [32]. The continuous wavelet transform provides multi-resolution analysis, capturing both high-frequency components with good time resolution and low-frequency components with good frequency resolution [34].

Spatial Domain Features utilize the topographic distribution of electrodes to extract information about brain activity patterns. Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) and its variants represent the most widely used algorithm for spatial filtering in motor imagery BCIs, maximizing variance between classes while minimizing variance within classes [34] [37]. Laplacian spatial filtering enhances the contribution of local neural activity while suppressing broader background activity, improving the signal-to-noise ratio for specific electrode locations [32].

Modern Deep Learning Approaches

Recent advancements have introduced end-to-end deep learning architectures that automatically learn optimal feature representations from raw or minimally processed EEG signals [34] [38]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) extract spatially and temporally localized features through hierarchical learning, while Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Temporal Convolutional Networks (TCNs) capture long-range dependencies in sequential data [38]. The emergence of transformer-based architectures with self-attention mechanisms has further improved capability to model global dependencies in EEG signals [34] [38].

Multi-scale convolutional approaches address the challenge of inter-subject variability by extracting features at different temporal resolutions simultaneously [34]. For example, Multi-Scale Convolutional Transformer (MSCFormer) networks integrate multiple CNN branches with varying kernel sizes to capture diverse frequency information, followed by transformer encoders to model global dependencies [34]. Similarly, hybrid architectures like EEGEncoder combine TCNs with modified transformers to capture both local temporal patterns and global contextual information [38].

Feature Selection Methodologies

Following feature extraction, selection algorithms identify the most discriminative subset of features to improve model performance and reduce computational requirements [32]. These methods can be broadly categorized into filter, wrapper, embedded, and hybrid approaches.

Filter methods employ statistical measures such as mutual information, correlation coefficients, or F-scores to rank features according to their relevance to the target variable, independent of the classification algorithm [32]. Wrapper methods utilize the performance of a specific classifier to evaluate feature subsets, with common approaches including recursive feature elimination and genetic algorithms [33] [32]. Embedded methods perform feature selection during the model training process, with algorithms like LASSO regularization and decision trees inherently selecting relevant features [32]. Hybrid methods combine filter and wrapper techniques to leverage the computational efficiency of filters with the performance optimization of wrappers [32].

Channel selection represents a specialized form of feature selection in EEG systems, reducing setup time and computational complexity while minimizing overfitting from redundant electrodes [32]. Techniques include filtering methods based on evaluation criteria, wrapping methods using classification algorithms, embedded methods utilizing criteria generated during classifier learning, and hybrid approaches [32].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Comparison of Feature Extraction Methods

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Feature Extraction Methods Across BCI Paradigms

| Method Category | Specific Approach | BCI Paradigm | Dataset | Accuracy (%) | Information Transfer Rate (bits/min) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | CSP + LDA | Motor Imagery | BCI Competition IV-2a | 76.80 | ~12.5 | Computational efficiency, interpretability |

| Traditional | FBCSP + SVM | Motor Imagery | BCI Competition IV-2a | 79.10 | ~15.2 | Frequency-specific feature optimization |

| Deep Learning | EEGNet | Motor Imagery | BCI Competition IV-2a | 80.20 | ~16.8 | Cross-subject generalization, minimal preprocessing |

| Deep Learning | MSCFormer (Proposed) | Motor Imagery | BCI Competition IV-2a | 82.95 | ~18.5 | Multi-scale feature fusion, global dependency modeling |

| Deep Learning | EEGEncoder (Proposed) | Motor Imagery | BCI Competition IV-2a | 86.46 (subject-dependent) | ~20.3 | Temporal-spatial feature integration, transformer-TCN fusion |

| Hybrid | SSVEP + P300 (LED-based) | Hybrid SSVEP/P300 | Custom Dataset | 86.25 | 42.08 | High ITR, reduced false positives through dual verification |

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Different BCI Datasets

| Model | BCI IV-2a (Accuracy %) | BCI IV-2b (Accuracy %) | Cross-Subject Generalization | Training Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSCFormer | 82.95 | 88.00 | Moderate | Moderate |

| EEGEncoder | 86.46 (subject-dependent) | N/R | Limited (74.48% subject-independent) | Lower due to complex architecture |

| ShallowConvNet | 78.30 | 82.50 | Higher | Higher |

| EEGNet | 80.20 | 84.10 | Higher | Higher |

| FBCSP | 79.10 | 83.20 | Moderate | Higher |

Impact of Feature Selection on Performance

The implementation of feature selection techniques demonstrates significant impacts on BCI system performance. Studies indicate that effective feature selection can improve classification accuracy by 5-15% while reducing feature dimensionality by 30-70% [32]. Genetic algorithms have shown particular efficacy in identifying optimal feature subsets for motor imagery classification, enhancing accuracy while significantly reducing computational load [33]. Channel selection algorithms have demonstrated the ability to maintain classification performance while using only 40-60% of original channels, substantially reducing system setup time and computational requirements [32].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Motor Imagery Feature Extraction

Motor imagery (MI) paradigms involve mental simulation of specific movements without physical execution, eliciting characteristic patterns of sensorimotor rhythm modulation [34]. The standard experimental protocol comprises the following stages:

Participant Preparation: Apply EEG electrodes according to the international 10-20 system, focusing on sensorimotor areas (C3, Cz, C4). Maintain impedance below 5 kΩ throughout the experiment [34] [37].

Experimental Design: Present visual cues indicating imagined movements (left hand, right hand, feet, tongue) in randomized order. Each trial consists of a fixation period (2s), cue presentation (3-4s), and rest period (2-3s) [34].

Data Acquisition: Record EEG signals with sampling rates of 160-250 Hz, applying appropriate bandpass filtering (0.5-100 Hz) and notch filtering (50/60 Hz) to remove line noise [34] [38].

Preprocessing: Apply artifact removal techniques (ocular, muscular) and spatial filtering (Laplacian, CAR). Segment data into epochs time-locked to cue presentation [34].

Feature Extraction: Implement multi-scale temporal convolution with kernel sizes ranging from 1×45 to 1×85 samples to capture diverse frequency information [34]. Alternatively, apply CSP or FBCSP algorithms for spatial-frequency feature extraction [34].

Classification: Utilize linear discriminant analysis, support vector machines, or deep learning classifiers for intention decoding [34] [38].

Figure 1: Comprehensive Workflow for BCI Feature Extraction and Selection