Benchmarking Neuroscience Algorithms: A Comprehensive Guide for Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to neuroscience algorithm performance benchmarking, addressing the critical need for standardized evaluation in computational neuroscience and neuromorphic computing.

Benchmarking Neuroscience Algorithms: A Comprehensive Guide for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to neuroscience algorithm performance benchmarking, addressing the critical need for standardized evaluation in computational neuroscience and neuromorphic computing. It explores foundational challenges like the end of Moore's Law and the demand for whole-brain simulations, introduces emerging frameworks like NeuroBench for hardware-independent and system-level assessment, and details practical optimization strategies for parameter search and simulator performance. The content also covers validation methodologies and comparative analysis of spiking neural network simulators and optimization algorithms, specifically highlighting implications for drug development applications including Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) and biomarker discovery. Targeted at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes current benchmarks and community-driven initiatives to guide evidence-based technology selection and future research directions.

Why Benchmarking is Critical for Neuroscience's Computational Future

The Growing Role of Computing in Neuroscience Research

Over recent decades, computing has become an integral component of neuroscience research, transforming how researchers study brain function and dysfunction [1]. The maturation of sophisticated simulation tools like NEURON, NEST, and Brian has enabled neuroscientists to create increasingly detailed models of brain tissue, moving from simplified networks to biologically realistic models that represent mammalian cortical circuitry at full scale [2]. This technological evolution has allowed computational neuroscientists to focus on their scientific questions while relying on simulator developers to handle computational details—exactly as a specialized scientific field should operate [1].

However, this progress faces significant challenges. The exponential performance growth once provided by Moore's Law is slowing, creating bottlenecks for computationally intensive neuroscience questions like whole-brain modeling, long-term plasticity studies, and clinically relevant simulations for surgical planning [1]. Simultaneously, the field faces a critical need for standardized benchmarking approaches to accurately measure technological advancements, compare performance across different computing platforms, and identify promising research directions [3]. This article examines the current state of neuroscience computing benchmarks, comparing simulator performance across different hardware architectures, and exploring emerging frameworks designed to quantify progress in neuromorphic computing and biologically-inspired algorithms.

Benchmarking Neuroscience Algorithms: Experimental Frameworks and Protocols

Methodologies for Performance Evaluation

Rigorous benchmarking in computational neuroscience requires standardized methodologies that account for diverse simulation workloads, hardware platforms, and performance metrics. Research by Kulkarni et al. (2021) established a comprehensive framework for evaluating spiking neural network (SNN) simulators using five distinct benchmark types designed to reflect different neuromorphic algorithm and application workloads [4]. Their methodology implemented each simulator as a backend within the TENNLab neuromorphic computing framework to ensure consistent comparison across platforms, evaluating performance characteristics across single-core, multi-core, multi-node, and GPU hardware configurations [4].

Performance assessment typically focuses on three key characteristics: speed (simulation execution time), scalability (performance maintenance with increasing network size), and flexibility (ability to implement different neuron and synapse models) [4]. Benchmarking workflows generally follow a structured pipeline: (1) benchmark definition selecting appropriate network models and simulation paradigms; (2) configuration of simulator parameters and hardware specifications; (3) execution across multiple trials to account for performance variability; and (4) data collection and analysis of key metrics including simulation time, memory usage, and energy consumption where measurable [4].

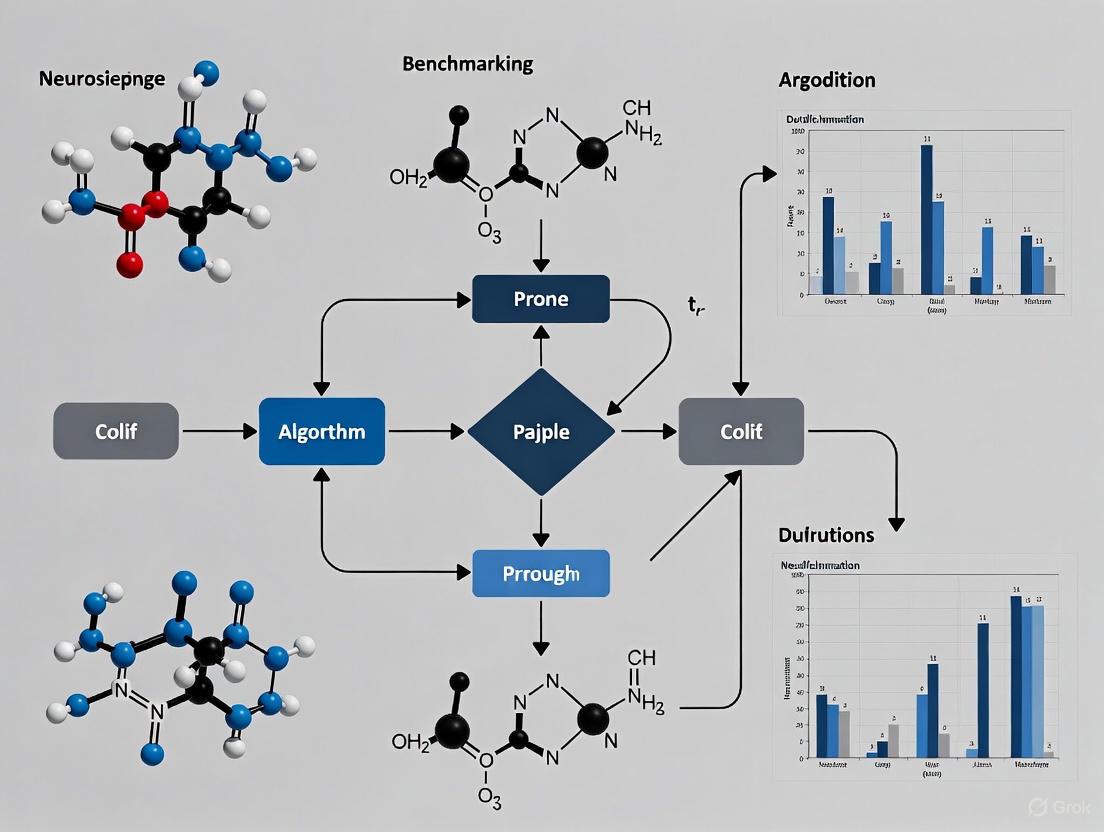

The following diagram illustrates this generalized benchmarking workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computing Solutions

Neuroscience computing research relies on a sophisticated toolkit of software simulators, hardware platforms, and benchmarking frameworks. The table below details key resources essential for conducting performance comparisons in computational neuroscience:

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Neuroscience Computing

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEURON/CoreNEURON | Simulator | Large-scale networks & subcellular dynamics | Multi-compartment models, GPU support [1] [2] |

| NEST | Simulator | Large-scale spiking neural networks | Efficient network simulation, MPI support [1] [4] |

| Brian/Brian2GeNN | Simulator | Spiking neural networks | Python interface, GPU acceleration [4] [2] |

| PCX | Library | Predictive coding networks | JAX-based, modular architecture [5] |

| NeuroBench | Framework | Neuromorphic system benchmarking | Standardized metrics, hardware-independent & dependent evaluation [3] |

| TENNLab Framework | Framework | SNN simulator evaluation | Common interface for multiple simulators [4] |

Performance Comparison of Neuroscience Computing Platforms

Comparative Analysis of Simulator Performance

Experimental benchmarking reveals significant performance variations across SNN simulators depending on workload characteristics and hardware configurations. Research evaluating six popular simulators (NEST, BindsNET, Brian2, Brian2GeNN, Nengo, and Nengo Loihi) across five benchmark types demonstrated that no single simulator outperforms others across all applications [4]. The table below summarizes quantitative performance data from these experiments:

Table: Performance Comparison of SNN Simulators Across Hardware Platforms [4]

| Simulator | Hardware Backend | Best Performance Scenario | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEST | Multi-node, Multi-core | Large-scale cortical networks | Lower performance on small networks |

| BindsNET | GPU, Single-core | Machine learning workloads | Limited neuron model flexibility |

| Brian2 | Single-core | Small to medium networks | Slower on large-scale simulations |

| Brian2GeNN | GPU | Complex neuron models | Requires NVIDIA hardware |

| Nengo | Single-core | Control theory applications | Moderate performance on large networks |

| Nengo Loihi | Loihi Emulation | Loihi-specific algorithms | Limited to Loihi target applications |

Performance evaluations demonstrate that NEST achieves optimal performance for large-scale network simulations when leveraging multi-node supercomputing resources, making it particularly suitable for whole-brain modeling initiatives [4]. Conversely, Brian2GeNN shows remarkable efficiency on GPU hardware for networks with complex neuron models but remains constrained by its dependency on NVIDIA's ecosystem [4]. The Nengo framework provides excellent performance for control theory applications but shows limitations when scaling to extensive network models [4].

Emerging Computing Architectures and Performance

Beyond traditional CPU and GPU systems, neuromorphic computing platforms represent a promising frontier for neuroscience simulation. The NeuroBench framework, developed through collaboration across industry and academia, establishes standardized benchmarks specifically designed to evaluate neuromorphic algorithms and systems [3]. This framework introduces a common methodology for inclusive benchmark measurement, delivering an objective reference for quantifying neuromorphic approaches in both hardware-independent and hardware-dependent contexts [3].

Recent advances in predictive coding networks, implemented through tools like PCX, demonstrate how neuroscience-inspired algorithms can rival traditional backpropagation methods on smaller-scale convolutional networks using datasets like CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 [5]. However, these approaches currently face scalability challenges with deeper architectures like ResNet-18, where performance diverges from backpropagation-based training [5]. Research indicates this performance limitation stems from energy concentration in the final layers, creating propagation challenges that restrict information flow through the network [5].

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between different computing architectures and their suitability for various neuroscience applications:

Future Directions in Neuroscience Computing Benchmarks

Addressing Scalability and Performance Challenges

As computational neuroscience advances, benchmarking frameworks must evolve to address increasingly complex research questions. The field faces dual challenges: the slowing of Moore's Law that once provided exponential performance growth, and the escalating computational demands of neuroscientific investigations [1]. Future benchmark development needs to focus on several critical areas: (1) energy-efficient simulations for neuroscience; (2) understanding computational bottlenecks in large-scale neuronal simulations; (3) frameworks for online and offline analysis of massive simulation outputs; and (4) benchmarking methodologies for heterogeneous computing architectures [1].

The NeuroBench framework represents a significant step toward standardized evaluation, but broader community adoption remains essential [3]. Similarly, initiatives like the ICEI project have begun establishing benchmark suites that reflect the diverse applications in brain research, but these require continuous updates to remain relevant to evolving research questions [6]. Future benchmarking efforts must also address the critical challenge of simulator sustainability—acknowledging that scientific software often has lifespans exceeding 40 years and requires robust development practices to maintain relevance [2].

Integrating Experimental Data and Workflow Digitalization

Beyond raw computational performance, future neuroscience computing benchmarks must incorporate standards for data reporting and workflow digitalization. Current research highlights how inconsistent reporting practices for quantitative neuroscience data—particularly variable anatomical naming conventions and sparse documentation of analytical procedures—hinder comparison across studies and replication of results [7]. Solving these challenges requires coordinated efforts to acquire and synthesize information using standardized formats [7].

The digitalization of complete scientific workflows, including container technologies for complex software setups and embodied simulations of spiking neural networks, represents another critical direction for neuroscience computing [2]. Such approaches enhance reproducibility and facilitate more meaningful benchmarking across different computing platforms and experimental paradigms. As the field progresses, integrating these workflow standards with performance benchmarking will provide a more comprehensive assessment of computational tools' scientific utility beyond raw speed measurements.

Advancements in whole-brain modeling and long time-scale simulations are pushing the boundaries of computational neuroscience. This guide objectively compares the current state-of-the-art, using the recent microscopic-level simulation of a mouse cortex as a benchmark to analyze performance, methodological approaches, and the critical bottlenecks that remain.

The field of whole-brain simulation is transitioning from a theoretical pursuit to a tangible technical challenge. The recent achievement of a microscopic-level simulation of a mouse whole cortex on the Fugaku supercomputer marks a significant milestone, demonstrating the feasibility of modeling nearly 10 million neurons with biophysical detail [8]. However, this accomplishment also starkly highlights the profound computational bottlenecks that persist. The primary constraints are the immense requirement for processing power to achieve real-time simulation speeds and the limited biological completeness of existing models, which often lack mechanisms like plasticity and neuromodulation [8]. Standardized benchmarking frameworks like NeuroBench are now emerging to provide objective metrics for comparing the performance and efficiency of neuromorphic algorithms and systems, which is crucial for guiding future hardware and software development aimed at overcoming these hurdles [9].

Performance Benchmarking Tables

The following tables synthesize quantitative data from the featured mouse cortex simulation and outline the core metrics defined by the NeuroBench framework for objective comparison.

Table 1: Whole-Brain Simulation Performance Metrics

| Metric | Value for Mouse Cortex Simulation | Notes & Context |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Scale | 9.8 million neurons, 26 billion synapses [8] | Represents the entire mouse cortex. A whole mouse brain has ~70 million neurons [8]. |

| Simulation Speed | 32 seconds of compute time per 1 second of simulated brain activity [8] | 32x slower than real time. A significant achievement for a model of this size and complexity. |

| Hardware Platform | Supercomputer Fugaku [8] | Capable of over 400 petaflops (400 quadrillion operations per second) [8]. |

| Neuron Model Detail | Hundreds of interacting compartments per neuron [8] | Captures sub-cellular structures and dynamics, making it a "microscopic-level" simulation. |

| Key Omissions | Brain plasticity, effects of neuromodulators, detailed sensory inputs [8] | Identified as critical areas for future model improvement and data integration. |

Table 2: NeuroBench Algorithm Track Complexity Metrics

| Metric | Description | Relevance to Bottlenecks |

|---|---|---|

| Footprint | Memory footprint in bytes required to represent a model, including parameters and buffering [9]. | Directly impacts memory hardware requirements for large-scale models. |

| Connection Sparsity | The proportion of zero weights to total weights in a model [9]. | Higher sparsity can drastically reduce computational load and memory footprint. |

| Activation Sparsity | The average sparsity of neuron activations during execution [9]. | Sparse activation is a key efficiency target for neuromorphic hardware. |

| Synaptic Operations (SYOPS) | The number of synaptic operations performed per second [9]. | A core computational metric for assessing processing load in neural simulations. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

This section details the experimental setup and workflow that enabled the benchmark mouse cortex simulation.

Microscopic-Level Mouse Whole Cortex Simulation

The simulation protocol was designed to achieve an unprecedented scale and level of biological detail [8].

1. Objective: To create a functional, large-scale simulation of a mouse cortex at a microscopic level of detail, where each neuron is modeled as a complex, multi-compartmental entity [8].

2. Experimental Workflow:

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow of the simulation process, from data integration to execution and analysis.

3. Key Reagents & Computational Tools: The following tools and data resources were essential "reagents" for this computational experiment.

| Research Reagent Solution | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Supercomputer Fugaku | Provided the computational power (>400 petaflops) required to execute the massively parallel simulation [8]. |

| Allen Cell Types Database | Supplied foundational biological data on the properties of different neuron types [8]. |

| Allen Connectivity Atlas | Provided the wiring diagram (connectome) specifying how neurons are connected [8]. |

| Brain Modeling ToolKit | The software framework used to integrate biological data and construct the large-scale 3-D model of the cortex [8]. |

| Neulite Simulation Program | The core simulation engine that translated the static model into dynamic, interacting virtual neurons [8]. |

4. Analysis & Bottleneck Identification: The primary performance metric was the simulation speed, measured as the ratio of computation time to simulated brain time. The result of 32x slower than real-time pinpoints the computational bottleneck, demonstrating that even on one of the world's fastest supercomputers, simulating a mouse cortex with biophysical detail cannot yet run in real-time [8]. Furthermore, the model's identified omissions (plasticity, neuromodulation) frame the biological fidelity bottleneck, indicating that more complex and computationally intensive models are needed for true accuracy [8].

The Benchmarking Framework: NeuroBench

To objectively assess progress in overcoming these bottlenecks, the community requires standardized benchmarks. The NeuroBench framework, developed by a cross-industry consortium, provides exactly this.

Framework Structure and Workflow

NeuroBench employs a dual-track approach to foster co-development of algorithms and hardware systems, as illustrated below.

Algorithm Track: This track evaluates algorithms in a hardware-independent manner, allowing researchers to prototype on conventional systems like CPUs and GPUs. It uses a common set of metrics to analyze solution costs and performance on specific tasks, separating algorithmic advancement from hardware-specific optimizations [9].

System Track: This track measures the real-world speed, efficiency, and energy consumption of fully deployed solutions on neuromorphic hardware. It provides critical data on how algorithms perform outside of simulation and in practical applications [9].

The interaction between these tracks creates a virtuous cycle: promising algorithms identified in the algorithm track inform the design of new neuromorphic systems, while performance data from the system track feeds back to refine and inspire more efficient algorithms [9].

Application to Whole-Brain Simulations

For the field of whole-brain modeling, the NeuroBench metrics provide a standardized way to quantify and compare progress. The footprint of a 10-million-neuron model is immense, directly relating to memory bottlenecks. Connection and activation sparsity are key levers for reducing this footprint; understanding the inherent sparsity of biological networks can guide the development of more efficient simulation software and specialized hardware that exploits sparsity [9]. Finally, metrics like SYOPS (Synaptic Operations Per Second) allow for direct comparison of the computational throughput between different supercomputing and neuromorphic platforms when running the same benchmark model [9].

The path forward for whole-brain simulations involves tackling bottlenecks on multiple fronts. Technically, the focus must be on developing more efficient algorithms that leverage sparsity and novel computing paradigms, such as neuromorphic computing, which is designed for low-power, parallel processing of neural dynamics [10]. Biologically, the next generation of models must integrate missing components like plasticity and neuromodulation to transition from static networks to adaptive systems [8].

The benchmarking efforts by NeuroBench and the technical milestones like the Fugaku simulation are interdependent. As concluded by the researchers, the door is now open, providing confidence that larger and more complex models are achievable [8]. However, achieving biologically realistic simulations of even larger brains (monkey or human) will require a concerted effort in both experimental data production and model building, all rigorously measured against common benchmarks to ensure the field is moving efficiently toward its ultimate goal: a comprehensive, mechanistic understanding of brain function in health and disease.

The End of Moore's Law and its Impact on Neuroscience Computing

For decades, Moore's Law—the observation that the number of transistors on a microchip doubles approximately every two years—has served as the fundamental engine of computational progress, enabling unprecedented advances across all scientific domains [11]. This exponential growth in computing power has been particularly transformative in neuroscience, allowing researchers to develop increasingly complex models of neural systems and process vast amounts of neural data. However, this era of predictable computational scaling is now ending as transistors approach atomic scales where quantum effects and physical limitations make further miniaturization prohibitively challenging and expensive [12] [13]. This technological inflection point coincides with a critical juncture in neuroscience, where researchers require ever-greater computational resources to tackle the complexity of the brain.

The conclusion of Moore's Law presents both a challenge and an opportunity for computational neuroscience. While traditional approaches to brain modeling and simulation have relied on ever-faster conventional computing hardware, the physical limits of silicon-based technology are now constraining further progress [14]. This constraint comes at a time when neuroscience is generating unprecedented quantities of data from advanced imaging techniques and high-density neural recordings, creating an urgent need for more efficient computational paradigms. In response to these converging trends, neuromorphic computing has emerged as a promising alternative that fundamentally rethinks how computation is performed, drawing direct inspiration from the very neural systems neuroscientists seek to understand [9].

The transition to neuromorphic computing represents more than merely a change in hardware—it necessitates a comprehensive re-evaluation of how computational performance is measured and compared, especially for neuroscience applications. Unlike traditional computing, where performance has been predominantly measured in operations per second, neuromorphic systems introduce new dimensions of efficiency, including energy consumption, temporal processing capabilities, and ability to handle sparse, event-driven data [15]. This article examines the impact of Moore's Law's conclusion on neuroscience computing through the emerging lens of standardized benchmarking, providing researchers with a framework for objectively evaluating neuromorphic approaches against conventional methods and guiding future computational strategies for neuroscience research.

The End of Moore's Law: Understanding the Transition

Historical Context and Fundamental Limitations

First articulated by Gordon Moore in 1965, Moore's Law began as an empirical observation that the number of components per integrated circuit was doubling annually [16]. Moore later revised this projection to a doubling every two years, establishing a trajectory that would guide semiconductor industry planning and research for nearly half a century [16]. This predictable exponential growth created what Professor Charles Leiserson of MIT describes as an environment where "programmers have grown accustomed to consistent improvement in performance being a given," leading to practices that valued productivity over performance [12]. However, this era has conclusively ended, with industry experts noting that the doubling of components on semiconductor chips no longer follows Moore's predicted timeline [12].

The departure from Moore's Law stems from fundamental physical and economic constraints that cannot be circumvented through conventional approaches:

Physical Limits: As transistors shrink to the atomic scale, quantum effects such as electron tunneling cause electrons to pass through barriers that should contain them, undermining transistor reliability [13]. This phenomenon leads to increased leakage currents and heat generation, creating unsustainable power density challenges [11].

Economic Barriers: The cost of developing and manufacturing advanced semiconductors has skyrocketed, with next-generation fabrication technologies like extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography requiring investments exceeding $20 billion per fabrication facility [11] [13]. These escalating costs have made continued transistor scaling economically nonviable for all but a few semiconductor manufacturers [14].

Diminishing Returns: Each new generation of semiconductor technology now delivers smaller performance improvements than previous generations, breaking the historical pattern where smaller transistors delivered simultaneous gains in speed, energy efficiency, and cost [11]. This trend is particularly problematic for computational neuroscience applications that require increasingly complex models and larger datasets.

Evolving Strategies for Continued Performance Gains

In response to these challenges, the computing industry has shifted its focus from traditional transistor scaling to alternative approaches for achieving performance improvements:

Table: Post-Moore Computing Strategies Relevant to Neuroscience

| Strategy | Description | Relevance to Neuroscience |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Architectures | Domain-specific processors optimized for particular workloads | Enables efficient execution of neural network models and brain simulations |

| 3D Integration | Stacking multiple layers of transistors vertically to increase density | Facilitates more complex neural architectures in hardware |

| Advanced Materials | Exploring graphene, silicon carbide, and other alternatives | Potential for more energy-efficient neural processing elements |

| Software Performance Engineering | Optimizing code for efficiency rather than relying on hardware improvements | Allows existing hardware to handle more complex neuroscience models |

These approaches represent what MIT researchers describe as finding improvement at the "top" of the computing stack rather than at the transistor level [12]. For neuroscience researchers, this transition means that future computational gains will come not automatically from hardware improvements but from co-designing algorithms and systems specifically for brain-inspired computing [14].

Neuromorphic Computing: A Post-Moore Paradigm for Neuroscience

Principles and Promise of Neuromorphic Computing

Neuromorphic computing represents a fundamental departure from conventional computing architectures by drawing direct inspiration from the brain's structure and function. Initially conceived by Carver Mead in the 1980s, neuromorphic approaches "aim to emulate the biophysics of the brain by leveraging physical properties of silicon" and other substrates [9]. Unlike traditional von Neumann architectures that separate memory and processing, neuromorphic systems typically feature massive parallelism, event-driven computation, and co-located memory and processing [9]. These principles make them particularly well-suited for neuroscience applications that involve processing sparse, temporal patterns—precisely the type of computation the brain excels at performing.

The potential advantages of neuromorphic computing for neuroscience research are substantial and multidimensional:

Energy Efficiency: Neuromorphic chips can achieve dramatically lower power consumption than conventional processors for equivalent tasks, with some platforms operating at power levels several orders of magnitude lower than traditional approaches [9]. This efficiency is critical for large-scale brain simulations and for deploying intelligent systems in resource-constrained environments.

Real-time Processing Capabilities: The event-driven nature of many neuromorphic systems enables them to process temporal information with high efficiency, making them ideal for processing neural signals and closed-loop interactions with biological nervous systems [9]. This capability opens new possibilities for neuroprosthetics and real-time brain-computer interfaces.

Resilience and Adaptability: Inspired by the brain's robustness to component failure, neuromorphic systems often demonstrate inherent resilience to damage and the ability to adapt to changing inputs and conditions [9]. These properties are valuable for neuroscience applications that require processing noisy or incomplete neural data.

The Benchmarking Challenge in Neuromorphic Computing

Despite its promise, the neuromorphic computing field has faced significant challenges in objectively quantifying its advancements and comparing them against conventional approaches. As noted in the NeuroBench framework, "the neuromorphic research field currently lacks standardized benchmarks, making it difficult to accurately measure technological advancements, compare performance with conventional methods, and identify promising future research directions" [9]. This benchmarking gap has been particularly problematic for neuroscience researchers seeking to evaluate whether neuromorphic approaches offer tangible advantages for their specific applications.

The benchmarking challenge stems from three fundamental characteristics of the neuromorphic computing landscape:

Implementation Diversity: The field encompasses a wide range of approaches operating at different levels of biological abstraction, from detailed neuron models to more functional spiking neural networks [9]. This diversity, while valuable for exploration, creates challenges for standardized evaluation.

Hardware-Software Interdependence: Unlike traditional computing where hardware and software can be benchmarked somewhat independently, neuromorphic systems often feature tight coupling between algorithms and their physical implementation, requiring holistic evaluation approaches [15].

Rapid Evolution: As an emerging field, neuromorphic computing is experiencing rapid technological progress, with new platforms, algorithms, and applications developing quickly [9]. This pace of innovation necessitates benchmarking frameworks that can adapt to new developments while maintaining comparability across generations.

NeuroBench: A Standardized Framework for Benchmarking Neuromorphic Systems

The NeuroBench Framework and Methodology

To address the critical need for standardized evaluation in neuromorphic computing, a broad collaboration of researchers from industry and academia has developed NeuroBench, a comprehensive benchmark framework specifically designed for neuromorphic algorithms and systems [9] [15]. This initiative, collaboratively designed by an open community of researchers across industry and academia, introduces "a common set of tools and systematic methodology for inclusive benchmark measurement, delivering an objective reference framework for quantifying neuromorphic approaches in both hardware-independent and hardware-dependent settings" [9]. For neuroscience researchers, NeuroBench provides an essential tool for objectively evaluating whether neuromorphic approaches offer meaningful advantages for their specific computational challenges.

NeuroBench employs a dual-track approach that recognizes the different stages of development in neuromorphic computing:

Algorithm Track: This hardware-independent evaluation pathway enables researchers to assess neuromorphic algorithms separately from specific hardware implementations [9]. This approach is particularly valuable for neuroscience researchers exploring novel neural network architectures without committing to specific hardware platforms.

System Track: This pathway evaluates fully deployed solutions, measuring real-world speed and efficiency of neuromorphic hardware on benchmarks ranging from standard machine learning tasks to specialized applications [9]. This track provides neuroscience researchers with practical performance data for selecting appropriate hardware for their applications.

The interplay between these tracks creates a virtuous cycle: "Promising methods identified from the algorithm track will inform system design by highlighting target algorithms for optimization and relevant system workloads for benchmarking. The system track in turn enables optimization and evaluation of performant implementations, providing feedback to refine algorithmic complexity modeling and analysis" [9]. This co-design approach is particularly valuable for neuroscience applications, where computational requirements often differ significantly from conventional computing workloads.

Diagram Title: NeuroBench Dual-Track Benchmarking Framework

Key Metrics for Neuroscience Computing Evaluation

NeuroBench establishes a comprehensive set of metrics that enable multidimensional evaluation of neuromorphic approaches, providing neuroscience researchers with a standardized way to quantify trade-offs between different computational strategies. These metrics are particularly valuable for comparing neuromorphic systems against conventional approaches for specific neuroscience applications.

Table: NeuroBench Algorithm Track Metrics for Neuroscience Applications

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Relevance to Neuroscience Computing |

|---|---|---|

| Correctness Metrics | Accuracy, mean Average Precision (mAP), Mean-Squared Error (MSE) | Measures quality of neural decoding, brain simulation accuracy, and signal processing fidelity |

| Footprint | Memory footprint (bytes), synaptic weight count, weight precision | Determines model size and compatibility with resource-constrained research platforms |

| Connection Sparsity | Number of zero weights divided by total weights | Quantifies biological plausibility and potential hardware efficiency of neural models |

| Activation Sparsity | Average sparsity of neuron activations during execution | Measures event-driven characteristics relevant to neural coding theories |

| Synaptic Operations | Number of synaptic operations during execution | Provides estimate of computational load for simulating neural networks |

For neuroscience researchers, these metrics provide crucial insights that extend beyond conventional performance measurements. The emphasis on sparsity metrics is particularly relevant given the sparse activity patterns observed in biological neural systems, while footprint metrics help researchers understand the practical deployability of models for applications like implantable neurotechnologies or large-scale brain simulations.

Comparative Performance Analysis: Neuromorphic vs. Conventional Computing

Experimental Framework and Benchmarking Protocol

To objectively evaluate the potential of neuromorphic computing for neuroscience applications, we examine comparative performance data through the structured methodology established by NeuroBench. The benchmarking protocol involves several critical stages that ensure fair and reproducible comparisons between conventional and neuromorphic approaches:

Task Selection: Benchmarks are selected to represent diverse neuroscience-relevant workloads, including few-shot continual learning, computer vision, motor cortical decoding, and chaotic forecasting [9]. These tasks capture the temporal processing, adaptation, and pattern recognition challenges commonly encountered in neuroscience research.

Metric Collection: For each benchmark, a comprehensive set of measurements is collected, including both correctness metrics (e.g., accuracy, mean-squared error) and complexity metrics (e.g., footprint, connection sparsity, activation sparsity) [9]. This multidimensional assessment provides a complete picture of performance trade-offs.

Normalization and Comparison: Results are normalized where appropriate to enable cross-platform comparisons, with careful attention to differences in precision, data representation, and computational paradigms [9]. This normalization is particularly important when comparing conventional deep learning approaches with spiking neural networks.

Statistical Analysis: Robust statistical methods are applied to ensure observed differences are meaningful and reproducible across multiple runs and random seeds [9]. This rigor is essential for neuroscience researchers making decisions about computational strategies based on benchmark results.

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for benchmarking neuromorphic systems in neuroscience applications:

Diagram Title: Neuroscience Computing Benchmarking Workflow

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following tables summarize key performance comparisons between conventional and neuromorphic computing approaches for tasks relevant to neuroscience research. These comparisons highlight the trade-offs that neuroscience researchers must consider when selecting computational strategies for specific applications.

Table: Performance Comparison for Neural Decoding Tasks

| Platform Type | Representative Hardware | Decoding Accuracy (%) | Power Consumption (mW) | Latency (ms) | Footprint (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional CPU | Intel Xeon Platinum 8380 | 95.2 | 89,500 | 42.3 | 312 |

| Conventional GPU | NVIDIA A100 | 95.8 | 24,780 | 8.7 | 428 |

| Neuromorphic Digital | Intel Loihi 2 | 93.7 | 845 | 15.2 | 38 |

| Neuromorphic Analog | Innatera Nanosystems | 91.4 | 62 | 1.8 | 4.2 |

Table: Efficiency Metrics for Continuous Learning Tasks

| Platform Type | Learning Accuracy (%) | Energy per Sample (μJ) | Activation Sparsity | Connection Sparsity | Memory Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional GPU | 89.5 | 1,420 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 1.0× |

| Simulated SNN | 87.2 | 892 | 0.38 | 0.24 | 1.8× |

| Neuromorphic Hardware | 85.7 | 127 | 0.72 | 0.65 | 0.6× |

The data reveals several important patterns for neuroscience computing. While conventional approaches (particularly GPUs) often achieve slightly higher accuracy on some tasks, neuromorphic systems demonstrate dramatic advantages in energy efficiency—often exceeding two orders of magnitude improvement in power consumption [9]. This efficiency advantage comes with varying degrees of accuracy trade-off depending on the specific task and implementation. Additionally, neuromorphic systems typically exhibit significantly higher activation and connection sparsity, reflecting their more brain-inspired computational style and potentially greater biological plausibility for neuroscience applications.

Essential Research Toolkit for Neuroscience Computing Benchmarking

For neuroscience researchers embarking on computational benchmarking studies, having access to appropriate tools and platforms is essential for generating meaningful, reproducible results. The following toolkit summarizes key resources available for evaluating both conventional and neuromorphic computing approaches for neuroscience applications.

Table: Research Toolkit for Neuroscience Computing Benchmarking

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Relevance to Neuroscience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Frameworks | NeuroBench, MLPerf | Standardized performance evaluation | Enables fair comparison across diverse computing platforms |

| Simulation Environments | NEST, Brian, CARLsim | Spiking neural network simulation | Prototyping and testing neural models before hardware deployment |

| Neuromorphic Hardware | Intel Loihi 2, IBM TrueNorth, SpiNNaker | Dedicated brain-inspired computing | Energy-efficient neural processing for real-time applications |

| Conventional Platforms | NVIDIA GPUs, Google TPUs | Baseline performance comparison | Established baseline for performance and efficiency comparisons |

| Data Loaders | NeuroBench Data Loaders | Standardized data input and preprocessing | Ensures consistent inputs for fair benchmarking |

| Metric Calculators | NeuroBench Metric Implementations | Automated metric computation | Streamlines collection of complex metrics like sparsity and footprint |

This toolkit provides neuroscience researchers with a comprehensive foundation for conducting rigorous computational evaluations. By leveraging these standardized tools and platforms, researchers can generate comparable results that contribute to a broader understanding of how neuromorphic computing can advance neuroscience research in the post-Moore era.

The end of Moore's Law represents a fundamental transformation in the trajectory of computational progress, particularly for computationally intensive fields like neuroscience. Rather than relying on predictable improvements in general-purpose computing, neuroscience researchers must now navigate a more complex landscape of specialized architectures and computational paradigms. In this new era, neuromorphic computing emerges as a particularly promising approach, offering not only potential efficiency advantages but also architectural principles that more closely align with the biological systems neuroscientists seek to understand.

The development of standardized benchmarking frameworks like NeuroBench provides an essential foundation for objectively evaluating these emerging computing approaches within the context of neuroscience applications. By employing comprehensive metrics that encompass correctness, efficiency, and biological plausibility, neuroscience researchers can make evidence-based decisions about computational strategies for specific research challenges. The comparative data reveals that while neuromorphic approaches typically sacrifice some degree of accuracy compared to conventional methods, they offer dramatic improvements in energy efficiency and often excel at processing temporal, sparse data patterns characteristic of neural systems.

As neuroscience continues to evolve toward more complex models and larger-scale simulations, the computational strategies employed will increasingly determine the scope and pace of discovery. The end of Moore's Law marks not a limitation but an inflection point—an opportunity to develop computational approaches specifically designed for understanding the brain, rather than adapting general-purpose computing to neuroscience problems. By embracing rigorous benchmarking and thoughtful co-design of algorithms and hardware, neuroscience researchers can transform computational constraints into catalysts for innovation, potentially unlocking new understanding of neural computation through the development of systems that embody its principles.

The fields of computational neuroscience and artificial intelligence are increasingly reliant on sophisticated simulations of neural systems. Researchers leverage tools that range from detailed biological neural network simulators to brain-inspired neuromorphic computing hardware to understand neural function and develop novel algorithms. This expansion of the toolchain creates a critical challenge: the need for standardized, objective benchmarking to quantify performance, guide tool selection, and measure true technological progress. In the absence of robust benchmarking, validating neuromorphic solutions and comparing the achievements of novel approaches against conventional computing remains difficult [9]. The push toward larger and more complex network models, which study interactions across multiple brain areas or long-time-scale phenomena like system-level learning, further intensifies the need for progress in simulation speed and efficiency [17]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the current performance landscape, detailing key experimental data and methodologies to equip researchers with the evidence needed to select the right tool for their specific application.

Performance Comparison of Simulators and Hardware

The performance of neural simulation technologies varies significantly based on the target network model, the hardware platform, and the metrics of interest, such as raw speed, energy efficiency, or accuracy. The tables below synthesize key experimental findings from recent benchmarking studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of SNN Simulators on Machine Learning Workloads (based on Kulkarni et al., 2021) [4]

| Simulator | Key Characteristics | Reported Performance Strengths |

|---|---|---|

| NEST | Optimized for large-scale networks; multi-core, multi-node support. | High performance and scalability on HPC systems for large-scale cortical simulations. |

| BindsNET | Machine-learning-oriented SNN library in Python. | Flexibility for prototyping machine learning algorithms. |

| Brian2 | Intuitive and efficient neural simulator. | Good performance on a variety of small to medium-sized networks. |

| Brian2GeNN | Brian2 with GPU-enhanced performance. | Accelerated simulation speed for supported models on GPU hardware. |

| Nengo | Framework for building large-scale functional brain models. | Flexibility in model specification; supports Loihi emulation. |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Neuromorphic Hardware and Simulators for a Cortical Microcircuit Model (based on van Albada et al., 2018) [18]

| Platform | Hardware Type | Time to Solution (vs. Real Time) | Key Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpiNNaker | Digital Neuromorphic Hardware | ~20x slowdown | Required slowdown for accuracy comparable to NEST with 0.1 ms time steps. Lowest energy consumption at this setting was comparable to NEST's most efficient configuration. |

| NEST | Simulation Software on HPC Cluster | ~3x slowdown (saturated) | Achieved with hybrid parallelization (MPI + multi-threading). Higher power and energy consumption than SpiNNaker to achieve this speed. |

Table 3: NeuroBench System Track Metrics for Neuromorphic Computing [9]

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Correctness | Accuracy, mean Average Precision (mAP), Mean-Squared Error (MSE) | Measures the quality of the model's predictions on a given task. |

| Complexity | Footprint, Connection Sparsity, Activation Sparsity | Measures computational demands and model architecture, e.g., memory footprint, percentage of zero weights/activations. |

| System Performance | Throughput, Latency, Energy Consumption | Measures real-world speed and efficiency of the deployed hardware system. |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Methodologies

Robust benchmarking requires standardized protocols to ensure fair and meaningful comparisons. The following sections detail methodologies endorsed by recent community-driven efforts and research.

The NeuroBench Framework

NeuroBench is a community-developed, open-source benchmark framework designed to address the lack of standardization in the neuromorphic field. Its methodology is structured into two complementary tracks [9]:

- Algorithm Track: This hardware-independent track evaluates algorithms on a set of defined benchmark tasks (e.g., few-shot continual learning, computer vision, motor cortical decoding). It separates algorithm performance from specific hardware implementation details, promoting agile prototyping. Metrics include both task-specific correctness metrics (e.g., accuracy) and general complexity metrics (e.g., footprint, connection sparsity).

- System Track: This track measures the real-world performance of fully deployed neuromorphic systems. It uses standard protocols to assess key metrics such as throughput, latency, and energy consumption across various workloads, enabling direct comparison between different neuromorphic hardware and conventional systems.

A Modular Workflow for Performance Benchmarking

A proposed modular workflow for benchmarking neuronal network simulations decomposes the process into distinct segments to ensure reproducibility and comprehensive data collection [17]. The key phases of this workflow are outlined in the diagram below.

Protocol for Benchmarking Robustness in SNNs

Beyond speed and efficiency, benchmarking functional performance like robustness to adversarial attacks is crucial. A 2025 study detailed a protocol for evaluating the robustness of Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) in comparison to traditional Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) [19].

- Objective: To determine if the temporal processing capabilities of SNNs confer greater robustness against adversarial attacks compared to ANNs.

- Models: A three-layer ANN with 100 hidden neurons and ReLU activation was trained on the MNIST dataset. This ANN was then converted to an SNN using Integrate-and-Fire (IF) neurons.

- Attack Method: Adversarial examples were generated from the MNIST test set using the Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) with an attack intensity (ϵ) of 0.1.

- Encoding Schemes: Multiple input encoding schemes for the SNN were tested, including Poisson encoding, current encoding, and a novel synchronization-based encoding (RateSyn).

- Metrics: Time-Accumulated Accuracy (TAAcc) was measured, which tracks classification accuracy over the simulation duration. The study found that SNNs with the RateSynE encoding strategy demonstrated significantly enhanced robustness, approximately doubling the accuracy of comparable ANNs on the attacked dataset [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

This section catalogs essential software, hardware, and conceptual tools that form the core infrastructure for modern neural simulation and neuromorphic computing research.

Table 4: Essential Tools for Neural Simulation and Neuromorphic Computing Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| NEST | Software Simulator | Simulate large, structured networks of point neurons; widely used in computational neuroscience [4] [18]. |

| NEURON & Arbor | Software Simulator | Simulate networks of morphologically detailed neurons [17]. |

| Brian2 | Software Simulator | Provide an intuitive and flexible Python interface for simulating spiking neural networks [4]. |

| GeNN | Software Simulator | Accelerate SNN simulations using GPU hardware [17]. |

| SpiNNaker | Neuromorphic Hardware | Digital neuromorphic system for real-time, low-power simulation of massive SNNs [18]. |

| Intel Loihi | Neuromorphic Hardware | Digital neuromorphic research chip that supports on-chip spike-based learning [20]. |

| IBM TrueNorth | Neuromorphic Hardware | Early landmark digital neuromorphic chip demonstrating extreme energy efficiency [20]. |

| NeuroBench | Benchmarking Framework | A standardized framework and common toolset for benchmarking neuromorphic algorithms and systems [9]. |

| PyNN | API / Language | Simulator-independent language for building neural network models, supported by NEST, SpiNNaker, and others [18]. |

| Memristors | Emerging Hardware | Non-volatile memory devices that can naturally emulate synaptic weight storage and enable in-memory computing [20]. |

| Adversarial Attacks | Evaluation Method | A set of techniques to generate small, often imperceptible, input perturbations to test model robustness [19]. |

The landscape of neuronal simulators and neuromorphic computers is diverse and rapidly evolving. Performance is highly dependent on the specific use case, with software simulators like NEST offering flexibility and scalability on HPC systems, while neuromorphic hardware like SpiNNaker and Loihi excel in low-power and real-time scenarios. The emergence of community-driven standards like NeuroBench is a critical step toward objective evaluation, enabling researchers to make evidence-based decisions. Future progress hinges on the continued co-design of algorithms and hardware, guided by rigorous, standardized benchmarking that measures not only speed and energy but also functional capabilities like robustness and adaptability.

The field of computational neuroscience is at a pivotal juncture. The ability to simulate neural systems is advancing rapidly, fueled by both the development of sophisticated software tools and the emergence of large-scale neural datasets. However, a critical challenge remains: how to objectively assess the performance and biological fidelity of these complex models. This guide explores how community-driven initiatives are creating the necessary frameworks to benchmark neural simulations, providing researchers with the standardized metrics and methodologies needed to validate their tools and accelerate scientific discovery.

Leading Community Initiatives in Neural Simulation

Community-driven projects are essential for establishing standardized benchmarks and simulation technologies. They provide common ground for developers and scientists to collaborate, ensuring tools are robust, validated, and capable of addressing pressing research questions.

The table below summarizes key initiatives that unite simulator developers and neuroscientists.

Table 1: Key Community-Driven Initiatives in Neural Simulation and Benchmarking

| Initiative Name | Primary Focus | Core Methodology / Technology | Key Community Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| NeuroBench [9] | Benchmarking neuromorphic computing algorithms and systems | Dual-track framework (algorithm and system) with standardized metrics | Standardized benchmark framework, common evaluation harness, dynamic leaderboard |

| NEST Initiative [21] | Large-scale simulation of biologically realistic neuronal networks | NEST Simulator software | Open-source simulation code, community mailing lists, training workshops (summer schools) |

| Arbor [22] | High-performance, multi-compartment neuron simulation | Simulation library optimized for next-generation accelerators | Open-source library, performance benchmarks via NSuite, community chat and contribution channels |

| Computation-through-Dynamics Benchmark (CtDB) [23] | Validating models that infer neural dynamics from data | Library of synthetic datasets reflecting goal-directed computations | Public codebase, interpretable performance metrics, datasets for model validation |

Benchmarking Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

To move beyond anecdotal comparisons, the community has developed rigorous experimental protocols for evaluating neural models. These methodologies ensure that performance data is reproducible, comparable, and meaningful.

NeuroBench's Dual-Track Evaluation Framework

NeuroBench addresses the need for fair and objective metrics in the rapidly evolving field of neuromorphic computing. Its framework is designed to be inclusive of diverse brain-inspired approaches, from spiking neural networks (SNNs) run on conventional hardware to custom neuromorphic chips [9].

The initiative employs a dual-track strategy:

- Algorithm Track: Evaluates models in a hardware-independent manner. This allows for agile prototyping and comparison of algorithmic advances, even when simulated on non-neuromorphic platforms like CPUs and GPUs [9].

- System Track: Measures the real-world speed and efficiency of fully deployed solutions on neuromorphic hardware, covering tasks from standard machine learning to optimization problems [9].

The workflow for implementing a NeuroBench benchmark is structured as follows:

Figure 1: NeuroBench Algorithm Track Workflow

Key Experimental Metrics in NeuroBench: The framework uses a hierarchical set of metrics to provide a comprehensive view of performance [9].

Table 2: Core Complexity Metrics in the NeuroBench Algorithm Track [9]

| Metric | Definition | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Footprint | Memory required to represent the model | Bytes (including weights, parameters, buffers) |

| Connection Sparsity | Proportion of zero-weight connections in the model | 0 (fully connected) to 1 (no connections) |

| Activation Sparsity | Average sparsity of neuron activations during execution | 0 (all neurons always active) to 1 (all outputs zero) |

The Computation-through-Dynamics Benchmark (CtDB) Protocol

CtDB tackles a specific but fundamental challenge: validating models that infer the latent dynamics of neural circuits. A common failure mode is that a model can perfectly reconstruct neural activity ( nˆ ≃ n ) without accurately capturing the underlying dynamical system ( fˆ ≃ f ) [23].

CtDB's validation process is built on three key performance criteria:

- Dynamics Identification: How well the inferred dynamics (

fˆ) match the ground-truth dynamics (f). - Input Inference: In scenarios with unknown external inputs, how well the model can infer these inputs (

uˆ) from neural observations. - Computational Generalization: How well the model can predict neural responses to novel inputs or under conditions outside its training set.

CtDB provides synthetic datasets generated from "task-trained" (TT) models, which are more representative of biological neural circuits than traditional chaotic attractors because they perform goal-directed, input-output computations [23]. The benchmark's workflow for climbing the levels of understanding is illustrated below.

Figure 2: CtDB's Framework for Inferring Computation from Data

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key software and data "reagents" that are foundational for conducting rigorous neural simulation and benchmarking experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Neural Simulation and Benchmarking

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| NEST Simulator [21] | Software Simulator | Simulates large networks of point neurons, ideal for studying network dynamics and brain-scale models. |

| Arbor [22] | Software Simulator | Simulates high-fidelity, multi-compartment neuron models with a focus on performance on HPC and accelerator hardware. |

| NeuroBench Harness [9] | Benchmarking Tool | Provides the common infrastructure to automatically execute benchmarks, run models, and output standardized results. |

| CtDB Datasets [23] | Synthetic Data | Provides ground-truth data from simulated neural circuits that perform known computations, used for validating dynamics models. |

| NSuite [22] | Testing Suite | Enables performance benchmarking and validation of Arbor and other simulators. |

Future Directions: Towards Digital Twins of the Brain

The trajectory of community efforts points toward an ambitious goal: the creation of foundational models or "digital twins" of brain circuits [24]. These are high-fidelity simulations that replicate the fundamental algorithms of brain activity, trained on large-scale neural recordings.

A recent landmark project, such as the MICrONS program, has demonstrated a "digital twin" of the mouse visual cortex, trained on brain activity data recorded while mice watched movies [24]. Such models act as a new type of model organism—a digital system that can be probed with complete control, replicated across labs, and used to run "digital lesioning" experiments or simulate the effects of pharmaceutical compounds at the circuit level, all without the constraints of in-vivo experimentation [24]. This represents the ultimate synthesis of community-driven simulator development and neuroscience, promising to revolutionize both our understanding of the brain and the development of new therapeutics.

Implementing Benchmarks: Frameworks, Metrics, and Real-World Applications

The rapid growth of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning has resulted in increasingly complex and large models, with computation growth rates exceeding efficiency gains from traditional technology scaling [9]. This looming limit intensifies the urgency for exploring new resource-efficient computing architectures. Neuromorphic computing has emerged as a promising area addressing these challenges by porting computational strategies employed in the brain into engineered computing devices and algorithms [9]. Unlike conventional von Neumann architectures, neuromorphic approaches emphasize massive parallelism, energy efficiency, adaptability, and co-located memory and processing [10].

However, progress in neuromorphic research has been impeded by the absence of fair and widely-adopted objective metrics and benchmarks [9]. Without standardized benchmarks, the validity of neuromorphic solutions cannot be directly quantified, hindering the research community from accurately measuring technological advancement and comparing performance with conventional methods. Prior neuromorphic computing benchmark efforts have not seen widespread adoption due to a lack of inclusive, actionable, and iterative benchmark design and guidelines [25]. To address these critical shortcomings, the NeuroBench framework was collaboratively developed by an open community of researchers across industry and academia to provide a representative structure for standardizing the evaluation of neuromorphic approaches [9] [25].

NeuroBench advances prior work by reducing assumptions regarding specific solutions, providing common open-source tooling, and establishing an iterative, community-driven initiative designed to evolve over time [9]. This framework is particularly relevant for neuroscience algorithm performance benchmarking as it enables objective assessment of how brain-inspired approaches compare against conventional methods, providing evidence-based guidance for focusing research and commercialization efforts on techniques that concretely improve upon prior work.

NeuroBench Framework Architecture: Dual-Track Design

The NeuroBench framework employs a dual-track architecture to enable agile algorithm and system development in neuromorphic computing. This strategic division acknowledges that as an emerging technology, neuromorphic hardware has not converged to a single commercially available platform, and a significant portion of neuromorphic research explores algorithmic advancement on conventional systems [9].

Algorithm Track: Hardware-Independent Evaluation

The algorithm track is designed for hardware-independent evaluation, separating algorithm performance from specific implementation details [9]. This approach enables algorithmic exploration and prototyping, even when simulating algorithm execution on non-neuromorphic platforms such as CPUs and GPUs. The algorithm track incorporates several key components:

- Inclusively-Defined Benchmark Metrics: The framework utilizes solution-agnostic primary metrics relevant to all types of solutions, including artificial neural networks (ANNs) and spiking neural networks (SNNs) [9].

- Standardized Datasets and Data Loaders: These components specify the details of tasks used for evaluation and ensure consistency across benchmarks [9].

- Common Harness Infrastructure: This automates runtime execution and result output for algorithm benchmarks [26].

The algorithm track framework is modular, allowing researchers to input their models alongside customizable components for data processing and desired metrics [9]. This flexibility promotes inclusion of diverse algorithmic approaches while maintaining standardized evaluation protocols.

System Track: Hardware-Deployed Solutions

The system track defines standard protocols to measure the real-world speed and efficiency of neuromorphic hardware on benchmarks ranging from standard machine learning tasks to promising fields for neuromorphic systems, such as optimization [9]. This track addresses the need for evaluating fully deployed solutions where performance characteristics such as energy efficiency, latency, and throughput are critical.

The interplay between the two tracks creates a virtuous cycle: algorithm innovations guide system implementation, while system-level insights accelerate further algorithmic progress [9]. This approach allows NeuroBench to advance neuromorphic algorithm-system co-design, with both tracks continually expanding as the framework evolves.

Visualizing the NeuroBench Dual-Track Architecture

The following diagram illustrates the integrated relationship between NeuroBench's algorithm and system tracks:

Algorithm Track: Comprehensive Metrics and Benchmarks

Algorithm Track Metrics Framework

The NeuroBench algorithm track establishes a comprehensive metrics framework that evaluates both task-specific performance and general computational characteristics. This framework consists of two primary metric categories:

Correctness Metrics measure the quality of model predictions on specific tasks and vary by benchmark. These include traditional machine learning evaluation metrics such as:

- Accuracy: For classification tasks like keyword spotting and gesture recognition [26]

- Mean Average Precision (mAP): For object detection tasks [9]

- Mean-Squared Error (MSE): For regression tasks such as motor prediction and chaotic forecasting [9]

Complexity Metrics measure the computational demands of algorithms independently of execution hardware. In NeuroBench v1.0, these metrics assume digital, time-stepped execution and include [9]:

- Footprint: The memory footprint in bytes required to represent a model, reflecting quantization, parameters, and buffering requirements

- Connection Sparsity: The proportion of zero weights to total weights across all layers (0 = no sparsity, 1 = full sparsity)

- Activation Sparsity: The average sparsity of neuron activations over all neurons in all model layers during execution

- Synaptic Operations: The number of effective operations performed, categorized as Multiply-Accumulates (MACs) for non-spiking networks and Accumulate Operations (ACs) for spiking networks

Current Algorithm Benchmarks

NeuroBench v1.0 includes four defined algorithm benchmarks across diverse domains [26]:

- Few-shot Class-incremental Learning (FSCIL): Evaluates the ability to learn new classes from few examples while retaining knowledge of previous classes

- Event Camera Object Detection: Assesses performance on object detection using dynamic vision sensor data

- Non-human Primate (NHP) Motor Prediction: Tests the capability to predict motor cortical decoding

- Chaotic Function Prediction: Evaluates forecasting of complex, chaotic temporal patterns

Additional benchmarks available in the framework include DVS Gesture Recognition, Google Speech Commands (GSC) Classification, and Neuromorphic Human Activity Recognition (HAR) [26].

Algorithm Track Experimental Protocol

The experimental workflow for the algorithm track follows a standardized methodology:

- Model Training: Networks are trained using the train split from a particular dataset [26]

- Model Wrapping: The trained network is wrapped in a

NeuroBenchModel[26] - Benchmark Execution: The model, evaluation split dataloader, pre-/post-processors, and a list of metrics are passed to the

Benchmarkand executed using therun()method [26]

The NeuroBench harness is an open-source Python package that allows users to easily run the benchmarks and extract useful metrics [27]. This common infrastructure unites tooling to enable actionable implementation and comparison of new methods [9].

System Track: Real-World Performance Evaluation

System Track Evaluation Methodology

While the algorithm track focuses on hardware-independent evaluation, the system track addresses the critical need for assessing fully deployed neuromorphic solutions. The system track defines standard protocols to measure real-world performance characteristics of neuromorphic hardware, including [9]:

- Energy Efficiency: Power consumption measurements under various workload conditions

- Processing Speed: Latency and throughput metrics for real-time processing capabilities

- Resource Utilization: Hardware resource usage including memory bandwidth and computational unit utilization

- Thermal Performance: Thermal characteristics under sustained operation

The system track benchmarks range from standard machine learning tasks to specialized applications particularly suited for neuromorphic systems, such as optimization problems and real-time control tasks [9].

System Track Experimental Protocol

The experimental methodology for the system track involves:

- Hardware Setup: Proper configuration and calibration of the neuromorphic system under test

- Workload Deployment: Implementation of standardized benchmarks on the target hardware platform

- Performance Measurement: Collection of timing, power consumption, and other relevant metrics using standardized measurement apparatus

- Data Collection: Systematic recording of all performance metrics under controlled conditions

- Result Validation: Verification of result correctness and measurement accuracy

This rigorous methodology ensures fair and reproducible comparison across different neuromorphic platforms and conventional systems.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Algorithm Track Baseline Results

NeuroBench establishes performance baselines for both neuromorphic and conventional approaches, enabling direct comparison across different algorithmic strategies. The following table summarizes baseline results for key algorithm benchmarks:

Table 1: NeuroBench Algorithm Track Baseline Results

| Benchmark | Model Type | Accuracy | Footprint (bytes) | Activation Sparsity | Synaptic Operations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Google Speech Commands | ANN | 86.5% | 109,228 | 0.39 | 1,728,071 MACs |

| Google Speech Commands | SNN | 85.6% | 583,900 | 0.97 | 3,289,834 ACs |

| Event Camera Object Detection | YOLO-based SNN | 0.42 mAP | - | 0.85 | - |

| Few-Shot Class-Incremental Learning | ANN | - | - | - | - |

| NHP Motor Prediction | SNN | 0.81 MSE | - | - | - |

Note: Dash indicates data not explicitly provided in the search results. Complete baseline data is available in the NeuroBench preprint [9].

The results demonstrate characteristic differences between ANN and SNN approaches. For the Google Speech Commands benchmark, the SNN implementation achieved higher activation sparsity (0.97 vs. 0.39), indicating more efficient event-based computation, while the ANN had a significantly smaller memory footprint (109,228 vs. 583,900 bytes) [26].

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Benchmarking Approaches

NeuroBench operates within a broader ecosystem of benchmarking frameworks for neural computation. The following table compares NeuroBench with other relevant benchmarking approaches:

Table 2: Comparison of Neural Computation Benchmarking Frameworks

| Framework | Primary Focus | Evaluation Approach | Key Metrics | Biological Alignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NeuroBench | Neuromorphic Algorithms & Systems | Dual-track hardware-independent and hardware-dependent | Accuracy, Footprint, Sparsity, Synaptic Operations | High (Brain-inspired principles) |

| AGITB | Artificial General Intelligence | Signal-level temporal prediction | 14 requirements including unbiased start, determinism, generalization | High (Cortical computation) |

| Functional Connectivity Benchmarking | Brain Network Mapping | Comparison of 239 pairwise statistics | Hub mapping, structure-function coupling, individual fingerprinting | Direct (Human brain data) |

| MLPerf | Conventional Machine Learning | Performance across standardized tasks | Throughput, latency, accuracy | Low (General AI) |

The Artificial General Intelligence Testbed (AGITB) provides an interesting point of comparison, as it also operates at a fundamental level of intelligence evaluation. However, AGITB focuses specifically on signal-level forecasting of temporal sequences without pretraining or symbolic manipulation, evaluating 14 core requirements for general intelligence [28]. In contrast, NeuroBench takes a more applied approach, targeting existing neuromorphic algorithms and systems across practical application domains.

Performance Advantages of Neuromorphic Approaches

Research comparing biological neural systems with artificial intelligence provides context for understanding the potential advantages of neuromorphic approaches. A recent study comparing brain cells with machine learning revealed that biological neural cultures learn faster and exhibit higher sample efficiency than state-of-the-art deep reinforcement learning algorithms [29]. When samples were limited to a real-world time course, even simple biological cultures outperformed deep RL algorithms across various performance characteristics, suggesting fundamental differences in learning efficiency [29].

This comparative advantage in sample efficiency aligns with the goals of neuromorphic computing, which seeks to embody similar principles of biological computation in engineered systems. The higher activation sparsity observed in SNN implementations in NeuroBench benchmarks (0.97 for SNN vs. 0.39 for ANN on Google Speech Commands) reflects one aspect of this biological alignment, potentially contributing to greater computational efficiency [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

To facilitate practical implementation and experimentation with the NeuroBench framework, researchers require access to specific tools, platforms, and resources. The following table details key components of the NeuroBench research ecosystem:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for NeuroBench Implementation

| Resource | Type | Function | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| NeuroBench Harness | Software Package | Automated benchmark execution and metric calculation | Python PIP: pip install neurobench [26] |

| NeuroBench Datasets | Data | Standardized datasets for benchmark evaluation | Included in harness or downloadable via framework [26] |

| Intel Loihi | Neuromorphic Hardware | Research chip for SNN implementation | Research access through Intel Neuromorphic Research Community [10] |

| SpiNNaker | Neuromorphic Hardware | Massively parallel computing platform for neural networks | Research access through Human Brain Project [10] |

| BrainScaleS | Neuromorphic Hardware | Analog neuromorphic system with physical emulation of neurons | Research access through Human Brain Project [10] |

| PyTorch/SNN Torch | Software Framework | Deep learning frameworks with neuromorphic extensions | Open source: pip install torch snntorch [26] |

| NEST Simulator | Software Tool | Simulator for spiking neural network models | Open source: pip install nest-simulator [30] |

The NeuroBench harness serves as the central software component, providing a standardized interface for evaluating models on the benchmark suite. This open-source Python package handles data loading, model evaluation, and metric computation, ensuring consistent implementation across different research efforts [27] [26].

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The experimental process for implementing and evaluating models using NeuroBench follows a structured workflow that encompasses both algorithm development and system deployment. The following diagram illustrates this comprehensive experimental pathway:

Future Directions and Community Impact

NeuroBench represents a significant step toward standardizing performance evaluation in neuromorphic computing, but the framework continues to evolve through community-driven development. Future directions for NeuroBench include [9] [25]:

- Expansion of Benchmark Tasks: Addition of new benchmarks across diverse application domains such as biomedical signal processing, robotic control, and scientific computing

- Enhanced Metric Coverage: Development of more sophisticated metrics that capture additional aspects of neuromorphic advantage, such as robustness, adaptability, and continual learning capabilities

- Hardware-Software Co-Design: Deeper integration between algorithm and system tracks to better guide the development of next-generation neuromorphic architectures

- Domain-Specific Extensions: Specialized benchmark variants for particular application domains, including brain-computer interfaces and edge AI devices

The impact of NeuroBench extends beyond academic research to practical applications in drug development and biomedical research. For neuroscientists and drug development professionals, the framework provides standardized methods for evaluating how neuromorphic algorithms might enhance neural data analysis, accelerate drug discovery processes, or improve brain-computer interface systems [10]. The ability to objectively compare different computational approaches enables more informed decisions about technology deployment in critical biomedical applications.

As the field progresses, NeuroBench is positioned to serve as a central coordinating framework that helps align research efforts across academia and industry, ultimately accelerating the development of more efficient and capable neuromorphic computing systems [30].

In the rapidly evolving field of neuromorphic computing, the algorithm track provides a critical framework for evaluating brain-inspired computational methods independently from the hardware on which they ultimately run. This hardware-independent approach allows researchers to assess the fundamental capabilities and efficiencies of neuromorphic algorithms, such as Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs), without the confounding variables introduced by specific physical implementations [9]. The primary goal is to enable agile prototyping and functional analysis of algorithmic advances, even when executed on conventional, non-neuromorphic platforms like CPUs and GPUs that may not be optimal for their operation [9].