AI-Powered Brain Tumor Segmentation from MRI: A Comprehensive Review for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of artificial intelligence (AI) applications for automated brain tumor segmentation in Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

AI-Powered Brain Tumor Segmentation from MRI: A Comprehensive Review for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of artificial intelligence (AI) applications for automated brain tumor segmentation in Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational need for these tools in overcoming the limitations of manual segmentation and the challenges posed by tumor heterogeneity. The review systematically covers the evolution of methodological approaches, from traditional machine learning to advanced deep learning architectures like U-Net and transformers, and their specific applications in clinical research and therapy planning. It further investigates the critical challenges and optimization techniques, including handling small metastases, data imbalance, and model generalizability. Finally, the article synthesizes validation frameworks, performance metrics, and comparative analyses of state-of-the-art models, offering a validated perspective on the current landscape and future trajectories of AI in accelerating neuro-oncology research and therapeutic development.

The Critical Need for AI in Brain Tumor Segmentation: Foundations and Clinical Imperatives

The Clinical Burden of Brain Tumors and the Pitfalls of Manual Segmentation

Brain tumors represent a significant and growing challenge to global healthcare systems, characterized by high morbidity and mortality rates. Epidemiological data indicates that brain tumors account for 1.5% of all cancer incidences, yet they cause a disproportionately high mortality rate of 3% [1]. With approximately 67,900 new primary CNS tumors diagnosed annually in the United States alone, and gliomas constituting 80% of all malignant primary brain tumors, the need for accurate diagnosis and treatment planning is paramount [2]. The current standard of care for aggressive forms like glioblastoma involves maximum safe surgical resection followed by radiotherapy and chemotherapy, yet this regimen affords only a median survival of 14-16 months, with fewer than 10% of patients surviving beyond 5 years [2].

Neuroimaging remains the cornerstone for diagnosis, treatment planning, and monitoring of brain tumors. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) specifically has emerged as the preferred modality due to its superior soft tissue contrast and high-resolution anatomical details without exposing patients to ionizing radiation [3] [1]. The accurate segmentation of brain tumors from MRI scans is critical for determining tumor location, size, shape, and extent, directly influencing surgical planning, radiation therapy targeting, and treatment response assessment [3] [4]. However, the traditional method of manual segmentation presents significant challenges that compromise both efficiency and diagnostic accuracy in clinical practice.

The Pitfalls of Manual Segmentation in Clinical Practice

Manual segmentation of brain tumors by radiologists represents a tedious, time-consuming task with considerable variability among raters [5] [4]. This process requires expert radiological knowledge and can require hours of expert work for a single case [6]. The inherent complexity of brain tumors, including variations in size, shape, location, and intensity heterogeneity across different MRI modalities, exacerbates these challenges [3].

The subjective nature of manual segmentation introduces significant inter-observer and intra-observer variability, potentially impacting diagnostic consistency and treatment outcomes [3] [7]. This variability becomes particularly problematic in multicenter clinical trials, where standardized and reproducible measurements are essential for validating therapeutic efficacy [2]. Furthermore, the labor-intensive nature of manual segmentation makes large-scale population studies or the analysis of extensive retrospective datasets impractical within clinical workflow constraints [6].

Table 1: Key Limitations of Manual Brain Tumor Segmentation

| Limitation | Clinical Impact | Quantitative Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Time-Intensive Process | Delays diagnosis and treatment planning; increases healthcare costs | Requires "hours of expert work" per case [6] |

| Inter-Observer Variability | Compromises diagnostic consistency and reliability in clinical trials | "Prone to inter- and intra-observer variability" [7] [5] |

| Subjective Interpretation | Potential for misdiagnosis or incomplete tumor margin delineation | "Strong subjective nature" makes adaptation to efficiency requirements difficult [1] |

| Workload Burden | Contributes to radiologist fatigue and healthcare system inefficiencies | Creates a "tedious task" for specialists [5] [4] |

Advanced MRI and Standardized Protocols in Neuro-Oncology

The Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) working group has established criteria for tumor response evaluation, highlighting the critical role of standardized imaging [2]. A standardized Brain Tumor Imaging Protocol (BTIP) has been developed through consensus among experts, clinical scientists, imaging specialists, and regulatory bodies to address variability in multicenter studies [2].

The minimum recommended sequences in BTIP include:

- Parameter-matched precontrast and postcontrast inversion recovery-prepared, isotropic 3D T1-weighted gradient-recalled echo

- Axial 2D T2-weighted turbo spin-echo acquired after contrast injection

- Precontrast, axial 2D T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR)

- Precontrast, axial 2D, 3-directional diffusion-weighted images [2]

These protocols balance feasibility with image quality, acknowledging the technical constraints of various clinical settings while ensuring sufficient data quality for accurate assessment. The initiative draws inspiration from standardizing efforts in other neurological fields, particularly the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), which established vendor-neutral, standardized protocols for volumetric analysis [2].

AI-Driven Segmentation: Methodological Advances and Quantitative Performance

Deep learning-based automated segmentation methods have demonstrated remarkable performance in brain tumor segmentation by learning complex hierarchical features from MRI data [7]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) have shown substantial improvements over traditional techniques, with several architectures emerging as particularly effective.

Evolution of Segmentation Architectures

The U-Net architecture, with its encoder-decoder structure and skip connections, has become a foundational model in medical image segmentation [3] [1]. Subsequent innovations have focused on enhancing this baseline architecture:

- Attention U-Net incorporates attention gates to suppress irrelevant regions and highlight salient features [3].

- nnU-Net (no-new-Net) represents a breakthrough with its self-configuring approach that adapts to any new dataset without manual intervention [6].

- Multi-Modal Multi-Scale Contextual Aggregation with Attention Fusion (MM-MSCA-AF) leverages multi-modal MRI inputs and employs gated attention fusion to selectively enhance tumor-specific features, achieving Dice scores of 0.8158 for necrotic regions and 0.8589 overall on the BRATS 2020 dataset [3].

Performance Comparison of Segmentation Models

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of AI Segmentation Models on Benchmark Datasets

| Model Architecture | Reported Dice Score | Key Innovations | Clinical Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| MM-MSCA-AF [3] | 0.8589 (total)0.8158 (necrotic) | Multi-scale contextual aggregation, gated attention fusion | Handles complex tumor shapes; suppresses background noise |

| ARU-Net [7] | 0.981 (DSC)0.963 (IoU) | Residual connections, Adaptive Channel Attention, Dimensional-space Triplet Attention | Captures heterogeneous structures; preserves fine details |

| TotalSegmentator MRI [6] | Strong accuracy across 80 structures | Sequence-agnostic design; trained on diverse MRI and CT data | Robust across scan types; minimal user intervention required |

| Improved YOLOv5s [1] | 93.5% precision85.3% recall | Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling, attention mechanisms | Balanced lightweight design with segmentation accuracy |

The BraTS (Brain Tumor Segmentation) challenge has been instrumental in advancing the field, providing a diverse multi-institutional dataset and establishing benchmarks for algorithm performance [5]. The most recent iterations have addressed critical clinical challenges, including handling missing MRI sequences through image synthesis approaches [5].

Experimental Protocols for AI Model Validation

Standardized Training and Evaluation Framework

To ensure reproducible and clinically relevant results, researchers should adhere to a standardized experimental protocol when developing and validating segmentation models:

Dataset Preparation and Preprocessing:

- Utilize established public datasets (e.g., BraTS, BTMRII) with expert-annotated ground truth [3] [7] [5].

- Implement standardized preprocessing including co-registration to a common anatomical template, resampling to uniform isotropic resolution (typically 1mm³), and skull-stripping [5].

- Employ data augmentation techniques (rotation, flipping, intensity variations) to improve model generalization.

Model Training Protocol:

- Implement k-fold cross-validation (typically 5-fold) to ensure robust performance estimation [3].

- Use appropriate loss functions for medical segmentation (Dice loss, categorical cross-entropy, or combinations) [7].

- Optimize with adaptive algorithms (Adam optimizer) with learning rate scheduling [7].

- Train for sufficient epochs (100-200) with early stopping to prevent overfitting [1].

Performance Evaluation Metrics:

- Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC/Dice Score): Measures spatial overlap between prediction and ground truth [3] [7].

- Intersection over Union (IoU): Assesses segmentation accuracy based on area of overlap [7].

- Precision and Recall: Quantifies the model's ability to correctly identify tumor pixels while minimizing false positives and negatives [1].

- Structural Similarity Index Measure (SSIM): Evaluates synthesized image quality in cases of missing modalities [5].

Addressing Missing Modalities in Clinical Practice

A common challenge in clinical environments is incomplete MRI protocols due to time constraints or artifacts. The BraSyn benchmark provides a protocol for handling such scenarios:

- Image Synthesis Evaluation: When one modality is missing, algorithms must synthesize plausible replacements using available sequences [5].

- Dual-Metric Assessment: Evaluate synthesized images using both SSIM for image quality and downstream Dice scores for segmentation utility [5].

- Clinical Validation: Assess whether synthesized images maintain diagnostic value comparable to acquired images through radiologist review.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Brain Tumor Segmentation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Datasets | Function and Application | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Datasets | BraTS [3] [5], BTMRII [7] | Benchmarking and training models; provides multi-modal MRI with expert annotations | Publicly available through respective challenge platforms |

| Segmentation Models | nnU-Net [6] [5], TotalSegmentator MRI [6] | State-of-the-art automated segmentation; adaptable to various imaging protocols | Open-source implementations available |

| Preprocessing Tools | CaPTk [5], FeTS tool [5] | Standardized preprocessing including co-registration, skull-stripping, resolution normalization | Publicly available toolkits |

| Evaluation Metrics | Dice Score, IoU, Precision/Recall [7] [1] | Quantitative performance assessment of segmentation accuracy | Standard implementations in machine learning libraries |

| Federated Learning | Federated learning frameworks [4] | Enables multi-institutional collaboration while preserving data privacy | Emerging methodology with various implementations |

The integration of AI-driven segmentation into neuro-oncology represents a paradigm shift in addressing the clinical burden of brain tumors. These methodologies directly mitigate the pitfalls of manual segmentation by providing rapid, reproducible, and quantitative analysis of tumor volumes and subregions. The demonstrated performance of contemporary models on benchmark datasets confirms their readiness for broader clinical validation and implementation.

Future research directions should focus on enhancing model interpretability, developing robust federated learning approaches to enable multi-institutional collaboration without data sharing [4], and improving sequence-agnostic segmentation to handle the variability of real-world clinical imaging protocols [6] [5]. As these technologies mature, they hold significant potential to transform neuro-oncological care by enabling more personalized treatment approaches and accelerating therapeutic development through more reliable quantitative endpoints in clinical trials.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) has established itself as the cornerstone of neuroimaging, providing unparalleled soft tissue contrast essential for diagnosing and managing brain tumors. Its value is significantly amplified when integrated with artificial intelligence (AI), particularly for automated tumor segmentation. This synergy enables precise, reproducible, and high-throughput analysis of brain tumors, which is critical for advancing research and drug development. The non-invasive nature of MRI, combined with its ability to reveal structural and functional information, makes it an indispensable tool in both clinical and research settings [8] [9]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the specific MRI sequences and their underlying biological correlates is fundamental to developing robust AI models and interpreting their output accurately. This document details the key MRI sequences, their experimental protocols, and their biological significance within the context of AI-driven brain tumor analysis.

Key MRI Sequences and Their Biological Correlates

Different MRI sequences are sensitive to distinct tissue properties, providing complementary information about the tumor microenvironment. The following table summarizes the primary sequences used in brain tumor imaging and their biological significance.

Table 1: Key MRI Sequences for Brain Tumor Analysis and Their Biological Correlates

| Sequence Name | Key Contrast Mechanisms | Biological Correlates in Brain Tumors | Primary Application in AI Segmentation |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1-weighted (T1w) | Longitudinal (T1) relaxation time | Anatomy of gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [9] | Spatial registration and anatomical reference [9] |

| T1-weighted Contrast-Enhanced (T1CE) | T1 relaxation, Gadolinium contrast agent leakage | Blood-brain barrier (BBB) disruption; active, high-grade tumor regions [10] [9] | Delineation of enhancing tumor core [11] [9] |

| T2-weighted (T2w) | Transverse (T2) relaxation time | Vasogenic edema and increased free water content [9] | Delineation of peritumoral edematous region [11] |

| Fluid-Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR) | T2 relaxation with CSF signal suppression | Vasogenic edema and non-enhancing tumor infiltration [9] | Delineation of the whole tumor region, including infiltrated tissue [11] |

The combination of these sequences is crucial for a comprehensive analysis. For instance, T1CE is excellent for highlighting the metabolically active core of high-grade gliomas where the blood-brain barrier is compromised, while FLAIR is more sensitive to the surrounding invasive tumor and edema, which is a critical target for therapy and resection planning [9]. AI models, particularly those based on U-Net architectures and its variants, are trained on these multi-modal inputs to automatically segment different tumor sub-regions with high accuracy, as demonstrated in benchmarks like the BraTS challenge [11] [9].

Experimental Protocols for Preclinical fMRI

Preclinical functional MRI (fMRI) is a powerful tool for investigating brain function and the effects of interventions in animal models. The following protocol outlines key considerations for conducting robust preclinical fMRI studies, which can be adapted to study tumor models and their functional impact.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Equipment for Preclinical fMRI

| Category | Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Animal Handling | Dedicated MRI cradle with head fixation (tooth/ear bars) [12] | Reduces motion artifacts, ensures reproducible positioning [12] |

| Anesthesia & Monitoring | Volatile (e.g., isoflurane) or injectable (e.g., medetomidine) anesthetics [12] | Maintains animal immobility and well-being; choice can affect hemodynamic response [12] |

| Physiological monitoring (respiratory rate, body temperature) [12] | Maintains physiological stability and animal welfare during scanning [12] | |

| Hardware | Ultrahigh-field MRI system (e.g., 7T to 18T) [12] | Increases functional contrast-to-noise ratio (fCNR) for BOLD fMRI [12] |

| High-performance gradients (400-1000 mT/m) [12] | Enables high spatial and temporal resolution for EPI sequences [12] | |

| Cryogenic radiofrequency (RF) coils [12] | Boosts signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) by reducing electronic noise [12] |

Protocol: Preclinical BOLD fMRI Acquisition

1. Animal Preparation and Anesthesia:

- Induce anesthesia in the animal (e.g., with 4% isoflurane in O₂) and secure it in a dedicated, stereotaxic MRI cradle using a tooth bar and ear bars to minimize head motion [12].

- Maintain anesthesia at a lower level (e.g., 1-2% isoflurane) and continuously monitor physiological parameters such as respiratory rate and body temperature throughout the experiment. Use a feedback-controlled heating system to maintain core body temperature at ~37°C [12].

2. Hardware Setup:

- Utilize an ultrahigh-field MRI system (≥ 7 Tesla) to maximize the blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) contrast and functional contrast-to-noise ratio (fCNR) [12].

- Employ a high-sensitivity radiofrequency (RF) coil, such as a cryogenically cooled array coil or an implantable coil, positioned as close as possible to the animal's head to optimize the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) [12].

- Ensure the gradient system is capable of high performance (strength > 400 mT/m, slew rate > 1000 T/m/s) to support the high-resolution Echo Planar Imaging (EPI) sequences used in fMRI [12].

3. fMRI Sequence Acquisition:

- Use a T2*-weighted Gradient Echo (GE) Echo Planar Imaging (EPI) sequence for BOLD signal detection. This sequence provides the necessary sub-second temporal resolution to track the hemodynamic response [12].

- Optimize EPI parameters based on the specific research question [12]:

- Spatial Resolution: Isotropic voxels of 100-300 μm are typical for rodents to precisely map functional responses.

- Temporal Resolution: A repetition time (TR) of 1-2 seconds is often used to accurately sample the hemodynamic response function.

- Other Parameters: Adjust the echo time (TE) to be close to the T2* of the tissue at the given magnetic field strength to maximize BOLD contrast.

- For stimulus-evoked fMRI, synchronize the presentation of the stimulus (sensory, optogenetic, etc.) with the start of the image acquisition.

AI-Driven Segmentation and Analysis

The core of automated brain tumor analysis lies in segmenting the tumor into its constituent parts. The following workflow details a standard methodology for developing and applying an AI segmentation model, using datasets from public challenges like BraTS (Brain Tumor Segmentation).

Protocol: AI Model Training for Volumetric Segmentation

1. Data Curation and Preprocessing:

- Dataset: Utilize a public dataset such as the BraTS (Brain Tumor Segmentation) challenge dataset, which provides multi-modal MRI scans (T1, T1CE, T2, FLAIR) with expert-annotated ground truth labels for various tumor sub-regions [11] [9].

- Preprocessing Steps: Implement a standardized pipeline including:

- Coregistration: Align all MRI sequences (T1, T1CE, T2, FLAIR) to a common space to ensure voxel-wise correspondence [13].

- Skull-stripping: Remove non-brain tissues using a tool like the Brain Extraction Tool (BET) from FSL [13].

- Intensity Normalization: Normalize the intensity values across all scans to improve model training stability and performance [11] [9].

- Data Augmentation: Apply affine transformations (rotations, scaling, etc.) to artificially expand the training dataset and improve model generalizability [11].

2. Model Architecture and Training:

- Architecture Selection: Implement a 3D U-Net architecture, which has been a foundational and winning model in segmentation challenges [9]. The U-Net's encoder-decoder structure with skip connections effectively captures context and preserves spatial information.

- Loss Function: Use a loss function suitable for class imbalance, such as the Dice Loss or a combination of Dice and Cross-Entropy Loss. The Dice Loss directly optimizes for the overlap between the prediction and ground truth, which is ideal for segmentation tasks where the target region is small relative to the background [9].

- Training: Train the model on the preprocessed multi-modal inputs (T1, T1CE, T2, FLAIR) to predict the voxel-wise labels for different tumor regions (e.g., necrotic core, enhancing tumor, peritumoral edema).

3. Validation and Performance Metrics:

- Primary Metric: Use the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) to evaluate model performance. The DSC measures the spatial overlap between the automated segmentation and the ground truth manual segmentation. A DSC of 0.70-0.75 is often considered competitive, with state-of-the-art models achieving scores above 0.85-0.90 for certain tumor sub-regions [10] [9].

- Additional Metrics: Report complementary metrics such as the Hausdorff Distance (HD) to capture the largest segmentation error, and Sensitivity/Specificity to assess classification accuracy [8].

Table 3: Quantitative Performance of AI Segmentation Models

| Model / Study | Task | Key Architecture | Performance (Dice Score) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI for Vestibular Schwannomas [10] | 3D Volumetric Segmentation of VS | Proprietary AI/ML algorithms | Final Mean Dice: 0.88 (Range: 0.74-0.93) |

| Glioma Grade Classification [11] | Glioma Segmentation & HGG/LGG Classification | U-Net + VGG | Segmentation Dice: Enhancing Tumor: 0.82, Whole Tumor: 0.91, Tumor Core: 0.72 |

| BraTS Challenge Top Performers [9] | Glioma Segmentation | Variants of U-Net (e.g., with residual blocks) | State-of-the-art Dice scores consistently >0.85 for whole tumor and tumor core regions |

The integration of these advanced AI methodologies with standardized MRI protocols provides a powerful framework for objective and quantitative analysis of brain tumors, facilitating more precise drug development and personalized treatment strategies.

Automated brain tumor segmentation from Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is a critical task in medical image analysis, facilitating early diagnosis, treatment planning, and disease monitoring for researchers, clinicians, and drug development professionals [3]. The process involves delineating different tumor subregions from multi-modal MRI scans, which is challenging due to the inherent complexity of brain tumors, including variations in size, shape, and location across different MRI modalities [3]. Traditional manual segmentation by radiologists is time-intensive, subjective, and prone to inter-observer variability, creating a pressing need for robust automated artificial intelligence (AI) solutions [14] [3].

This document outlines the fundamental task of segmenting a brain tumor from its entirety down to its enhancing core, detailing the defining characteristics of each subregion, the AI methodologies employed, and the experimental protocols for developing and validating such models. The focus extends from whole tumor identification to the precise delineation of the enhancing tumor core, a critical region for therapeutic targeting and treatment response assessment [15].

Defining the Tumor Subregions

In brain tumor analysis, particularly for gliomas, the tumor is not a homogeneous entity but is comprised of several distinct subregions, each with unique radiological and clinical significance. The segmentation task is hierarchically defined by these subregions [3].

Table 1: Brain Tumor Subregions in Glioma Segmentation

| Tumor Subregion | Description | Clinical & Research Significance | Best Visualized on MRI Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Tumor (WT) | The complete abnormal area, encompassing the core and the surrounding edema. | Crucial for initial diagnosis, assessing mass effect, and overall tumor burden. | FLAIR (suppresses CSF signal, making edema appear bright) [3] [15] |

| Tumor Core (TC) | Comprises the necrotic core, enhancing tumor, and any non-enhancing solid tumor. | Important for determining tumor grade and aggressive potential. | T1-weighted Contrast-Enhanced (T1-CE) [3] [15] |

| Enhancing Tumor (ET) | The portion of the tumor that shows uptake of contrast agent, indicating a leaky blood-brain barrier. | A key biomarker for tumor activity, treatment planning, and monitoring response to therapy. | T1-weighted Contrast-Enhanced (T1-CE) [3] [15] |

The foundational step involves identifying the Whole Tumor (WT), which includes the core tumor mass and the surrounding peritumoral edema (swelling) [3]. The Tumor Core (TC) is then isolated from the whole tumor, which involves separating the solid tumor mass from the surrounding edema. Within the tumor core, the Enhancing Tumor (ET) is the most active and vital region to segment for many clinical decisions [15].

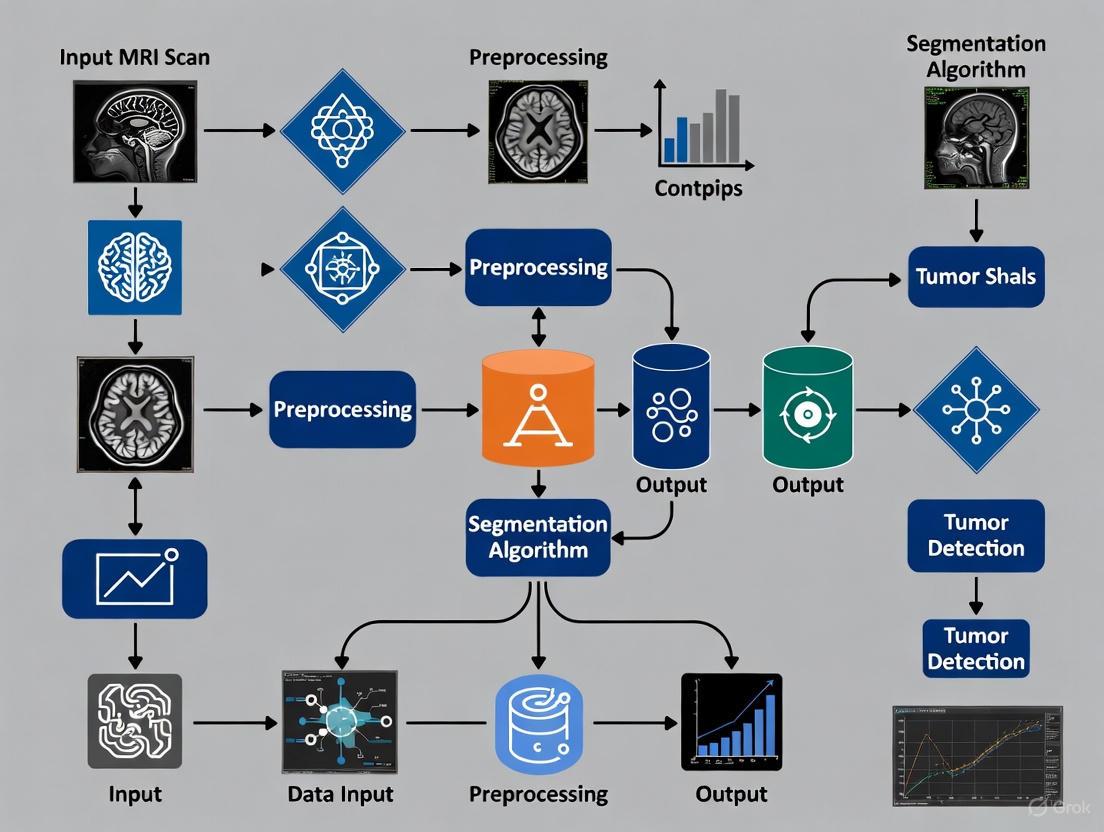

Diagram 1: Hierarchical segmentation workflow from whole tumor to enhancing core.

AI Architectures for Tumor Segmentation

From Traditional ML to Deep Learning

Early automated segmentation methods relied on traditional machine learning (ML) techniques such as Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Logistic Regression (LR). These models often required extensive feature engineering (e.g., texture, shape descriptors) and dimensionality reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to handle the high-dimensional MRI data [14] [3]. While effective, their performance was limited by their dependence on hand-crafted features and their inability to capture the complex, hierarchical spatial dependencies in MRI data [3].

The field has been revolutionized by Deep Learning (DL), particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), which automatically learn relevant features directly from the image data in an end-to-end manner [3] [16]. Architectures like U-Net and its 3D variant have become the standard baselines and workhorses for this task [17] [15]. The U-Net's encoder-decoder structure with skip connections allows it to effectively capture both context and precise localization, which is essential for accurate segmentation [15].

Advanced and Specialized Architectures

Research has progressed to more sophisticated architectures designed to address specific challenges in brain tumor segmentation:

- Multi-Modal Multi-Scale Models: Frameworks like MM-MSCA-AF leverage multiple MRI sequences (T1, T1-CE, T2, FLAIR) and employ multi-scale contextual aggregation to capture both global and fine-grained spatial features. They use gated attention fusion to selectively refine tumor-specific features and suppress irrelevant noise, thereby improving segmentation accuracy for complex tumor shapes [3].

- Lightweight and Efficient Models: For deployment in resource-constrained settings, lightweight models such as optimized 3D U-Net are developed to run efficiently on standard CPUs, balancing computational cost with segmentation accuracy [17].

- Architectures for Reduced Data Input: Studies have systematically evaluated the minimal set of MRI sequences required for accurate segmentation. Evidence suggests that a model trained on just T1C and FLAIR can achieve performance comparable to one using all four standard sequences, particularly for the enhancing tumor and tumor core, which can simplify clinical deployment [15].

- One-Stage Detection Models: Algorithms from the YOLO (You Only Look Once) family, known for their speed in object detection, have been adapted and improved for segmentation tasks. Enhancements like the incorporation of Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) and attention mechanisms (CBAM, CA) help these models capture multi-scale context and focus on relevant tumor regions [1].

Table 2: Comparison of AI Models for Brain Tumor Segmentation

| Model Architecture | Key Features & Mechanics | Reported Performance (Dice Score) | Computational Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| SVM with RBF Kernel | Traditional ML; requires manual feature extraction and PCA. | Testing Accuracy: 81.88% [14] | Lower computational cost but limited by feature engineering. |

| 3D U-Net | 3D volumetric processing; encoder-decoder with skip connections. | ET: 0.867, TC: 0.926 (on T1C+FLAIR) [15] | Standard for volumetric data; can be optimized for CPUs [17]. |

| MM-MSCA-AF | Multi-modal input; multi-scale contextual aggregation; gated attention fusion. | Overall Dice: 0.8589; Necrotic: 0.8158 [3] | Higher complexity but robust for heterogeneous tumors. |

| Improved YOLOv5s | One-stage detection; incorporates ASPP and attention modules (CBAM, CA). | Precision: 93.5%; Recall: 85.3% [1] | Designed for speed and efficiency; lightweight version available. |

| Lightweight 3D U-Net | Simplified architecture optimized for low-resource systems. | Dice: 0.67 on validation data [17] | Designed for CPU-based training and inference. |

Experimental Protocols & Application Notes

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for training and validating a deep learning model for brain tumor segmentation, synthesizing methodologies from cited research.

Phase 1: Data Collection, Preparation, and Preprocessing

Objective: To curate and prepare a multi-modal MRI dataset for model training.

- Dataset Acquisition:

- Source a publicly available, annotated dataset such as the BraTS (Brain Tumor Segmentation) challenge dataset [3] [17] [15]. The BraTS 2020 dataset, for example, includes multi-institutional MRI scans with ground truth annotations for tumor subregions [3].

- Ensure the dataset includes the four standard MRI sequences for each patient: Native T1 (T1), Post-contrast T1-weighted (T1-CE), T2-weighted (T2), and T2-FLAIR (FLAIR) [3] [15].

- Data Preprocessing:

- Skull-Stripping: Remove non-brain tissue from the images using validated tools or pre-processed data provided with the dataset [15].

- Spatial Normalization: Interpolate all scans to a uniform isotropic resolution (e.g., 1mm³) [15].

- Intensity Normalization: Apply Z-score normalization to each MRI sequence independently to achieve a zero mean and unit variance, mitigating scanner and protocol variations [15].

- Data Augmentation: Artificially expand the training dataset using real-time transformations during training to improve model generalizability. Standard techniques include:

- Random rotations (±5°)

- Random translations

- Horizontal and vertical flipping

- Elastic deformations

- Intensity scaling and shifts [15].

Phase 2: Model Building and Training

Objective: To implement, configure, and train a segmentation model.

- Model Selection and Implementation:

- Select a model architecture based on the project's goals (e.g., accuracy vs. speed vs. computational resources). A 3D U-Net is a strong baseline choice [15].

- Implement the model in a deep learning framework like PyTorch or TensorFlow. For a lightweight 3D U-Net, initialize the network with a standard depth of 4 contraction/expansion layers and an initial filter size of 32, which doubles at each downsampling step [17] [15].

- Training Configuration:

- Data Splitting: Split the dataset into training (e.g., 80%), validation (e.g., 10%), and a held-out test set (e.g., 10%). Use cross-validation if the dataset is limited [14] [15].

- Loss Function: Use a combination of Dice loss and cross-entropy loss to handle class imbalance between tumor and non-tumor voxels.

- Optimizer: Use the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1e-4 and a batch size tailored to available GPU memory (e.g., 1 or 2 for 3D models).

- Training Loop: Train the model for a fixed number of epochs (e.g., 100-300), using the validation Dice score to select the best model and to trigger early stopping if the performance plateaus.

Diagram 2: End-to-end model training and validation protocol.

Phase 3: Model Evaluation and Validation

Objective: To quantitatively and qualitatively assess the trained model's performance.

- Quantitative Metrics:

- Dice Similarity Coefficient (Dice Score): The primary metric for segmentation overlap. Calculate separately for the Whole Tumor (WT), Tumor Core (TC), and Enhancing Tumor (ET) [3] [15].

- Hausdorff Distance: Measures the largest distance between the predicted and ground truth segmentation boundaries, assessing the accuracy of the outer margins [15].

- Sensitivity and Specificity: Evaluate the model's ability to identify true positives and true negatives [15].

- Qualitative Analysis:

- Visually inspect the model's segmentation outputs against the ground truth by generating overlay images.

- Perform error analysis to identify common failure modes, such as misclassification due to structural similarities between tumor types or confusion with healthy tissues [14].

Phase 4: Deployment Considerations

Objective: To outline steps for model deployment in real-world scenarios.

- Model Optimization: Convert the trained model to an efficient inference format (e.g., ONNX, TensorRT) to reduce latency.

- Integration: Package the model within a user-friendly application programming interface (API) or software plugin that can interface with clinical Picture Archiving and Communication Systems (PACS).

- Continuous Validation: Establish a pipeline for monitoring model performance on prospective data to detect and correct for data drift over time.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Resources for Brain Tumor Segmentation Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Role in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Public Datasets | BraTS (Brain Tumor Segmentation Challenge), TCIA (The Cancer Imaging Archive) [14] [3] | Provides standardized, multi-modal MRI data with expert annotations for training and benchmarking models. |

| Computing Hardware | GPU (NVIDIA series) or CPU (Intel Core i5/i7 with ≥8GB RAM) [17] | Accelerates model training and inference. CPU-based protocols enable research in resource-constrained settings [17]. |

| Software & Libraries | Python, PyTorch/TensorFlow, MONAI, Visual Studio Code [17] | Core programming languages and specialized libraries for developing, training, and testing deep learning models. |

| Evaluation Metrics | Dice Score, Hausdorff Distance, Sensitivity, Specificity [3] [15] | Standardized quantitative measures to objectively evaluate and compare the performance of different segmentation models. |

| Model Architectures | 3D U-Net, nnU-Net, MM-MSCA-AF, Improved YOLO [3] [17] [1] | Pre-defined neural network blueprints that form the foundation for solving the segmentation task. |

The Evolution from Traditional Image Processing to AI-Driven Solutions

The analysis of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans represents a cornerstone of modern neuro-oncology, providing critical insights for the diagnosis, treatment planning, and monitoring of brain tumors. The journey from traditional image processing techniques to contemporary artificial intelligence (AI)-driven solutions marks a revolutionary shift in how medical professionals extract information from complex imaging data [18]. This evolution has fundamentally transformed the landscape of brain tumor segmentation, moving from time-consuming, operator-dependent methods toward automated, precise, and reproducible analytical frameworks [19] [8].

Initially, the segmentation of brain tumors relied heavily on manual delineation by expert radiologists, a process requiring years of specialized training yet remaining susceptible to inter-observer variability and fatigue [19]. The subsequent development of traditional automated methods offered initial improvements but struggled with the inherent complexity and heterogeneity of brain tumor manifestations across different MRI sequences and patient populations [3]. The advent of machine learning, and particularly deep learning, has addressed many of these limitations, enabling the development of systems that not only match but in some cases surpass human-level performance in specific detection and segmentation tasks [20] [9].

This application note delineates this technological evolution, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a structured overview of the quantitative benchmarks, experimental protocols, and essential research tools that underpin modern AI-driven solutions for brain tumor analysis in MRI.

Quantitative Evolution of Segmentation Performance

The performance of brain tumor segmentation methodologies has advanced significantly across technological generations. The transition from manual approaches to deep learning-based systems is quantifiably demonstrated through standardized metrics such as the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC), which measures spatial overlap between segmented and ground truth regions.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Segmentation Approaches on the BRATS Dataset

| Method Category | Representative Model | Whole Tumor DSC | Tumor Core DSC | Enhancing Tumor DSC | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional ML | SVM / Random Forests | ~0.75-0.82 | ~0.65-0.75 | ~0.60-0.72 | [3] [9] |

| Basic Deep Learning | Standard U-Net | ~0.84 | ~0.77 | ~0.73 | [3] [21] |

| Advanced Deep Learning | nnU-Net | ~0.90 | ~0.85 | ~0.82 | [9] [21] |

| Hybrid Architectures | MM-MSCA-AF (2025) | 0.8589 | 0.8158 (Necrotic) | N/A | [3] |

The quantitative leap is most evident in the segmentation of complex sub-regions like the enhancing tumor, which is critical for assessing tumor activity and treatment response. Early machine learning models, dependent on handcrafted features (e.g., texture, shape), achieved limited success with DSCs often below 0.75 for these structures [3]. The introduction of deep learning architectures, notably the U-Net and its variants, marked a significant improvement, leveraging end-to-end learning from raw image data [9] [21]. Contemporary hybrid models, such as the Multi-Modal Multi-Scale Contextual Aggregation with Attention Fusion (MM-MSCA-AF), further push performance boundaries by selectively refining feature representations and discarding noise, achieving a Dice value of 0.8158 for the challenging necrotic tumor core [3].

Beyond segmentation accuracy, AI-driven solutions demonstrate profound operational impacts. One study evaluating an AI tool for detecting critical findings using abbreviated MRI protocols reported a sensitivity of 94% for brain infarcts, 82% for hemorrhages, and 74% for tumors, performance comparable to consultant neuroradiologists and superior to MR technologists [20]. This capability is a prerequisite for emerging AI-driven workflows that can dynamically select additional imaging sequences based on real-time findings, potentially revolutionizing MRI acquisition protocols [20] [22].

Experimental Protocols for AI Model Evaluation

The rigorous evaluation of novel AI-based segmentation models requires standardized protocols to ensure comparability and clinical relevance. The following section details a core experimental workflow, drawing from established methodologies used in benchmark challenges like the Multimodal Brain Tumor Segmentation (BraTS) [9] [21].

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Against Public Datasets

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the performance of a new segmentation model against state-of-the-art methods using a publicly available benchmark dataset.

Materials:

- Dataset: BraTS 2020 dataset, containing multi-institutional pre-operative multi-modal MRI scans (T1, T1-CE, T2, T2-FLAIR) of glioblastoma (GBM/HGG) and lower-grade glioma (LGG) with pixel-wise expert annotations [3] [9].

- Validation Split: The provided training set is typically split 80:20 for training and validation, while the ground truth for the official test set is held private by challenge organizers.

- Computing Environment: High-performance computing node with GPU acceleration (e.g., NVIDIA A100 with 40GB+ VRAM).

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Implement a standard preprocessing pipeline. This includes co-registration of all modalities to the same anatomical template, interpolation to a uniform isotropic resolution (e.g., 1mm³), and intensity normalization (e.g., z-score normalization per sequence across the entire dataset) [3] [21].

- Data Augmentation: Apply on-the-fly data augmentation during training to improve model generalization. Standard operations include random rotation (±15°), flipping (axial plane), scaling (±10%), and intensity shifts (±20% gamma) [21].

- Model Training: Configure the proposed model (e.g., MM-MSCA-AF) with published hyperparameters. A typical setup uses the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1e-4 and a combined loss function (e.g., Dice Loss + Cross-Entropy Loss) to handle class imbalance. Training proceeds for a fixed number of epochs (e.g., 1000) with early stopping if validation performance plateaus [3].

- Inference and Evaluation: Apply the trained model to the validation or test set. Generate segmentation masks and compute key metrics via the official BraTS evaluation platform. Primary metrics include Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) for overlap and Hausdorff Distance (HD95) for boundary accuracy, reported separately for the whole tumor, tumor core, and enhancing tumor [3] [21].

Protocol 2: Clinical Workflow Integration for Abbreviated MRI

Objective: To validate the performance of an AI model in a simulated clinical workflow using abbreviated MRI scan protocols, assessing its potential for real-time, AI-driven scan adaptation.

Materials:

- Cohort: A retrospective, consecutively enriched cohort of routine adult brain MRI scans from multiple clinical sites (e.g., n=414 patients) [20].

- Imaging Protocols: An abbreviated MRI protocol (e.g., 3-sequence: DWI, SWI/T2*-GRE, T2-FLAIR) and a standard 4-sequence protocol (adding T1W) for comparison [20].

- Reference Standard: Ground truth established from original radiological reports corroborated by independent image review by expert neuroradiologists.

Methodology:

- AI and Human Reader Setup: The AI tool and a panel of readers (e.g., consultant neuroradiologists, radiology residents, MR technologists) are provided with the abbreviated protocol images only [20].

- Blinded Assessment: Both AI and human readers independently analyze the scans to detect and localize critical findings: brain infarcts, intracranial hemorrhages, and tumors.

- Performance Analysis: Calculate sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy for the AI and each group of human readers against the reference standard. Compare the AI's performance directly against that of the human experts using statistical tests for proportions (e.g., McNemar's test) [20].

- Assisted Performance Evaluation: In a subsequent round, human readers re-evaluate the cases with access to the AI's predictions, allowing assessment of how AI assistance impacts human sensitivity and specificity.

Diagram 1: AI Segmentation Workflow. This diagram outlines the standard workflow for training and evaluating a deep learning model for brain tumor segmentation from multi-modal MRI inputs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The development and validation of AI-driven segmentation tools rely on a suite of key resources, from public datasets to software frameworks. The table below catalogs essential "research reagents" for this field.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for AI-Based Brain Tumor Segmentation

| Item Name / Category | Specifications / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Public Benchmark Datasets | BraTS (Brain Tumor Segmentation) Challenge Datasets [9] [21] | Provides standardized, multi-institutional, expert-annotated MRI data for model training, benchmarking, and fair comparison against state-of-the-art methods. |

| Multi-modal MRI Scans | T1-weighted, T1-CE (contrast-enhanced), T2-weighted, T2-FLAIR [3] [9] | Provides complementary tissue contrasts necessary for a comprehensive evaluation of tumor sub-regions (edema, enhancing core, necrosis). |

| Annotation / Ground Truth | Pixel-wise manual segmentation labels by expert neuroradiologists [9] [21] | Serves as the gold standard for training supervised deep learning models and for evaluating the accuracy of automated segmentation outputs. |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow, MONAI (Medical Open Network for AI) | Provides open-source libraries and tools for building, training, and deploying complex deep learning architectures for medical imaging. |

| High-Performance Computing | NVIDIA GPUs (e.g., A100, V100) with CUDA cores | Accelerates the computationally intensive processes of model training and inference on large 3D medical image volumes. |

| Evaluation Metrics | Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC), Hausdorff Distance (HD95) [3] [21] | Quantifies the spatial overlap and boundary accuracy of segmented masks against ground truth, enabling objective performance assessment. |

Visualization of Methodological Evolution

The conceptual and architectural shift from traditional methods to modern AI solutions can be visualized as a logical pathway, highlighting the key differentiators in their approach to feature extraction and learning.

Diagram 2: Evolution of Segmentation Methodologies. This diagram contrasts the fundamental workflows of traditional machine learning methods, which rely on manually engineered features, with deep learning approaches that learn features directly from data in an end-to-end manner.

Application Note: AI-Driven Diagnostic Segmentation for Tumor Identification and Characterization

Background and Clinical Rationale

Accurate and timely diagnosis of brain tumors is a critical determinant of patient outcomes. Manual segmentation of tumors from multi-sequence Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans by radiologists is a time-intensive process prone to inter-observer variability, creating bottlenecks in diagnostic pathways [7] [14]. Automated AI-based tumor segmentation addresses this challenge by providing rapid, quantitative, and reproducible analysis of tumor characteristics, enabling more consistent and early detection.

Quantitative Performance of Diagnostic AI Models

Advanced deep learning models have demonstrated high performance in delineating brain tumors, as evidenced by evaluation metrics on benchmark datasets. The following table summarizes the capabilities of state-of-the-art models, including the novel ARU-Net architecture, which integrates residual connections and attention mechanisms [7].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of AI Models for Brain Tumor Diagnostic Segmentation

| AI Model / Architecture | Reported Accuracy | Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) | Intersection over Union (IoU) | Key Diagnostic Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARU-Net [7] | 98.3% | 98.1% | 96.3% | Superior capture of heterogeneous tumor structures and fine structural details. |

| U-Net + Residual + ACA [7] | ~97.2% | ~95.0% | ~88.6% | Effective feature refinement in lower convolutional layers. |

| Baseline U-Net [7] | ~94.0% | ~91.7% | ~80.9% | Baseline performance for a standard encoder-decoder segmentation network. |

| SVM with RBF Kernel [14] | 81.88% (Classification) | N/A | N/A | Effective for tumor classification tasks using traditional machine learning. |

Recommended Clinical Protocol for Diagnostic Segmentation

Purpose: To standardize the acquisition of MRI data for optimal performance of automated AI segmentation tools in tumor diagnosis. Primary Modalities: T1-weighted, T1-weighted contrast-enhanced (T1ce), T2-weighted, and T2-FLAIR [7] [23] [24].

- Patient Preparation: Standard MRI safety screening. The use of contrast agents (for T1ce sequences) should follow institutional guidelines.

- Image Acquisition:

- AI Integration & Analysis:

- Pre-processing: Implement a standardized pre-processing pipeline on acquired DICOM images. This should include:

- Contrast Enhancement: Apply Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) to improve feature visibility [7].

- Denoising: Use filters (e.g., Linear Kuwahara) to reduce noise while preserving critical edges of tumor contours [7].

- Intensity Normalization: Standardize pixel intensity values across scans to ensure model consistency.

- Model Inference: Process the pre-processed multi-sequence volume through a validated segmentation AI (e.g., ARU-Net) to generate a voxel-wise classification map.

- Pre-processing: Implement a standardized pre-processing pipeline on acquired DICOM images. This should include:

- Output and Reporting:

- The AI system should output a segmentation mask overlay on the original MRI, delineating tumor sub-regions (e.g., enhancing tumor, necrotic core, peritumoral edema).

- The quantitative report should include tumor volume, location, and morphometric features derived from the segmentation mask to aid in diagnosis and grading [7] [14].

Diagram 1: AI Diagnostic Segmentation Workflow

Application Note: AI-Enhanced Surgical Planning and Intraoperative Guidance

Background and Clinical Rationale

Precise surgical planning is paramount for maximizing tumor resection while minimizing damage to eloquent brain areas responsible for critical functions like movement, speech, and cognition. AI segmentation provides a foundational 3D map of the tumor and its relationship to surrounding neuroanatomy, which is essential for pre-operative planning and can be integrated with intraoperative navigation systems [24] [25].

Experimental Protocol for Surgical Planning Models

Objective: To generate patient-specific, high-fidelity 3D models of brain tumors for pre-surgical simulation and intraoperative guidance. Dataset: High-resolution 3D MRI sequences (T1ce, T2) are essential. Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) for tractography and functional MRI (fMRI) can be co-registered for advanced planning [24].

- Data Acquisition:

- Acquire pre-operative MRI using dedicated "STEREOTACTIC BRAIN" or "DTI BRAIN" protocols [24]. These protocols are optimized for high spatial fidelity and minimal distortion.

- AI Processing and Integration:

- Tumor and Anatomy Segmentation: Employ a robust AI model (e.g., an ARU-Net variant trained on surgical cases) to segment the tumor, necrotic core, and key anatomical structures.

- Multi-Modal Fusion: Integrate the AI-generated segmentation masks with DTI-based white matter tractography (e.g., corticospinal tract) and fMRI activation maps if available.

- 3D Reconstruction: Convert the fused 2D segmentation masks into a 3D volumetric model suitable for import into surgical navigation systems.

- Clinical Application:

- Pre-surgical Planning: The 3D model allows surgeons to visualize tumor margins in relation to critical functional areas, plan the safest surgical trajectory, and simulate the resection.

- Intraoperative Navigation: The model is uploaded to the surgical navigation system, providing real-time guidance during the procedure. The system tracks surgical instruments in relation to the patient's anatomy and the pre-defined 3D model.

Key Reagent Solutions for Surgical Planning Research

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for AI-Driven Surgical Planning

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application in Protocol |

|---|---|

| ARU-Net or Similar Architecture [7] | Provides the core segmentation algorithm; its high Dice score ensures accurate 3D model boundaries. |

| Multi-sequence MRI Data (T1ce, T2) [7] [23] | The primary input data for the AI model to identify different tumor sub-regions and anatomy. |

| Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) [24] | Enables the reconstruction of white matter tracts to be avoided during surgery. |

| Functional MRI (fMRI) [24] | Identifies eloquent cortical areas (e.g., motor, speech) for functional preservation. |

| Surgical Navigation Software | The platform for importing 3D models and enabling real-time intraoperative guidance. |

Diagram 2: AI Surgical Planning Pipeline

Application Note: AI-Powered Treatment Monitoring and Response Assessment

Background and Clinical Rationale

Monitoring tumor evolution—whether progression, regression, or pseudo-progression—in response to therapy (e.g., radiation, chemotherapy) is vital for adaptive treatment strategies. AI segmentation automates the longitudinal tracking of volumetric changes with superior consistency and sensitivity compared to manual 1D or 2D measurements like Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) criteria [23] [25].

Quantitative Analysis of Treatment Monitoring AI

AI models must handle longitudinal data and potential variations in imaging protocols over time. Research has shown that using AI-generated images to complete missing sequences can significantly enhance the consistency and accuracy of segmentation across multiple time points [23].

Table 3: AI Performance in Handling Missing Data for Longitudinal Studies

| Scenario | Method for Handling Missing MRI Sequence | Impact on Segmentation Dice Score (DSC) |

|---|---|---|

| Missing T1ce | Using AI-generated T1ce from other sequences (UMMGAT) [23] | Significant improvement in DSC for Enhancing Tumor (ET) compared to copying available sequences. |

| Missing T2 or FLAIR | Using AI-generated T2/FLAIR from other sequences (UMMGAT) [23] | Significant improvement in DSC for Whole Tumor (WT) compared to copying available sequences. |

| Multiple Missing Sequences | Using AI to generate all missing inputs (UMMGAT) [23] | Provides more accurate segmentation of heterogeneous tumor components than methods using copied sequences. |

Experimental Protocol for Treatment Response Monitoring

Objective: To quantitatively assess changes in tumor volume and sub-region characteristics across multiple follow-up MRI scans, even with incomplete or inconsistent imaging data. Dataset: Longitudinal MRI scans from the same patient (Baseline, Follow-up 1, Follow-up 2, etc.). Each time point should ideally include T1, T1ce, T2, FLAIR [23].

- Image Acquisition and Integrity Check:

- Perform follow-up scans using a consistent MRI protocol (e.g., "ROUTINE BRAIN W/WO" or "TUMOR BRAIN" protocol) [24].

- Document any missing sequences or significant changes in acquisition parameters compared to baseline.

- Data Harmonization and Completion:

- If sequences are missing at a follow-up time point, employ an unsupervised generative AI model like UMMGAT (Unpaired Multi-center Multi-sequence Generative Adversarial Transformer) to synthesize the missing sequences based on the available ones [23].

- This step ensures a consistent, complete multi-sequence input for the segmentation model across all time points, mitigating cross-center or cross-scanner inconsistencies.

- Longitudinal Segmentation and Analysis:

- Process all complete (or completed) multi-sequence MRI volumes through the same, validated AI segmentation model.

- Extract quantitative metrics from the segmentation masks at each time point: Volumes of Whole Tumor, Enhancing Tumor, and Necrotic Core.

- Response Assessment:

- Calculate the percentage change in key volumetric metrics between time points.

- Generate a longitudinal report with trend graphs, providing an objective basis for evaluating treatment efficacy and guiding potential therapy modifications.

Diagram 3: AI Treatment Monitoring Workflow

From CNNs to Transformers: A Deep Dive into AI Methodologies and Their Applications

Application Notes

Automated brain tumor segmentation from MRI scans is a critical task in neuro-oncology, supporting diagnosis, treatment planning, and disease monitoring. The evolution of deep learning has produced three dominant architectural paradigms, each with distinct strengths and limitations for this specialized domain. This document provides a structured overview of Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)-based, U-Net-based, and Vision Transformer (ViT) models, framing their development within the context of automated tumor segmentation research for brain MRI.

Core Architectural Paradigms and Performance

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and representative performance metrics of the three main architectural paradigms in brain tumor segmentation.

Table 1: Comparison of Architectural Paradigms for Brain Tumor Segmentation

| Architectural Paradigm | Key Characteristics & Strengths | Common Model Variants | Reported Performance (Dice Score) | Primary Clinical Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN-based Models | - Strong local feature extraction [26]- Parameter sharing efficiency [26]- Established, robust performance | - Darknet53 [27]- ResNet50 [27]- VGG16, VGG19 [28] | - 98.3% accuracy (classification) [27]- 0.937 Dice (segmentation) [27] | - High-accuracy tumor classification [27]- Initial automated segmentation tasks |

| U-Net-based Models | - Encoder-decoder structure [3]- Skip connections for spatial detail preservation [3] [21]- Foundation for extensive modifications | - 3D U-Net [29]- Attention U-Net [3]- nnU-Net [3]- ARU-Net [7] | - 0.856 (Tumor Core) [29]- 0.981 Dice [7]- 98.3% accuracy [7] | - Precise pixel-wise tumor subregion segmentation (e.g., TC, ET) [29]- Clinical research benchmark |

| Vision Transformer (ViT) Models | - Self-attention for global context [30] [31]- Captures long-range dependencies [30]- Less inductive bias than CNNs | - Pure ViT [28]- UNETR [30]- TransBTS [30] | - ~0.93 Median Dice (BraTS2021) [30]- 96.72% accuracy (classification) [28] | - Handling complex, heterogeneous tumor structures [30]- Multi-modal MRI integration |

Performance Across Tumor Sub-regions

Segmentation performance can vary significantly across different tumor sub-regions due to challenges like class imbalance and varying contrast. The following table details the performance of specific models on the enhancing tumor (ET), tumor core (TC), and whole tumor (WT) regions, as commonly evaluated in benchmarks like the BraTS challenge.

Table 2: Detailed Model Performance on Brain Tumor Sub-regions

| Model Name | Architecture Type | MRI Modalities Used | Dice Score (Enhancing Tumor) | Dice Score (Tumor Core) | Dice Score (Whole Tumor) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D U-Net [29] | U-Net-based | T1C + FLAIR | 0.867 | 0.926 | - |

| BiTr-Unet [30] | Hybrid (CNN+ViT) | T1, T1c, T2, FLAIR | 0.8874 | 0.9350 | 0.9257 |

| ARU-Net [7] | U-Net-based (with Attention) | T1, T1C+, T2 | - | - | 0.981 |

| MM-MSCA-AF [3] | U-Net-based | T1, T2, FLAIR, T1-CE | 0.8158 (Necrotic) | 0.8589 (Overall) | - |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Training a 3D U-Net with Minimal MRI Sequences

This protocol is adapted from a study that successfully achieved high segmentation accuracy using a reduced set of MRI sequences, which can enhance practical applicability and generalizability [29].

Objective: To train a 3D U-Net model for segmenting Tumor Core (TC) and Enhancing Tumor (ET) using only T1C and FLAIR MRI sequences.

Materials:

- Dataset: MICCAI BraTS 2018 and 2021 datasets [29].

- Software Framework: PyTorch or TensorFlow with 3D convolutional layer support.

- Hardware: GPU with sufficient memory for 3D volumetric data (e.g., ≥ 12GB VRAM).

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Obtain the BraTS dataset, which includes native T1, post-contrast T1-weighted (T1C), T2-weighted (T2), and T2-FLAIR volumes.

- Select only the T1C and FLAIR sequences for each patient. Discard T1 and T2 volumes to create the minimal input set.

- Preprocess the data as per BraTS standards, including co-registration to a common template, interpolation to a uniform resolution (e.g., 1mm³), and skull-stripping.

Data Preprocessing & Augmentation:

- Normalize the intensity values of each modality independently to zero mean and unit variance.

- Apply on-the-fly data augmentation to mitigate overfitting. Use 3D transformations such as:

- Random rotation (range: ±15°)

- Random flipping (horizontal)

- Elastic deformations

- Additive Gaussian noise

Model Configuration:

- Implement a standard 3D U-Net architecture [29]. The encoder (contracting path) should use 3D convolutional layers with 3x3x3 kernels and ReLU activation, followed by 2x2x2 max-pooling for downsampling.

- The decoder (expanding path) should use 3D transposed convolutions for upsampling.

- Incorporate skip connections between corresponding encoder and decoder levels to preserve fine-grained spatial details.

Model Training:

- Loss Function: Use a combination of Dice loss and Cross-Entropy loss to handle class imbalance.

- Optimizer: Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 1e-4.

- Training Regimen: Train for a maximum of 1000 epochs with early stopping if the validation loss does not improve for 50 consecutive epochs.

- Validation: Use 5-fold cross-validation on the training dataset (e.g., BraTS 2018 with n=285) to tune hyperparameters.

Model Evaluation:

- Test Dataset: Use a held-out test set (e.g., a combination of BraTS 2018 validation set and BraTS 2021 data, n=358) [29].

- Metrics: Evaluate the model using Dice Similarity Coefficient (Dice), Hausdorff Distance (HD95), Sensitivity, and Specificity for the ET and TC sub-regions independently.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Hybrid CNN-Transformer Model (BiTr-Unet)

This protocol outlines the steps for building a hybrid architecture that leverages the local feature extraction of CNNs and the global contextual understanding of Transformers [30].

Objective: To implement and train the BiTr-Unet model for multi-class brain tumor segmentation on multi-modal MRI scans.

Materials:

- Dataset: BraTS2021 dataset (T1, T1c, T2, FLAIR).

- Software: Python, PyTorch, NiBabel for handling NIfTI files.

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Convert each patient's multi-modal MRI scans (NIfTI files) into a 4D NumPy array (Dimensions: 4 x H x W x D).

- Apply z-score normalization to each 3D MRI modality independently.

- Cache the preprocessed data as Pickle (.pkl) files for faster I/O during training.

Network Architecture:

- 3D CNN Encoder: Construct an encoder with four downsampling stages using 3x3x3 convolutional blocks with a stride of 2. Integrate 3D Convolutional Block Attention Modules (CBAM) after each downsampling stage to adaptively refine features [30].

- Transformer Bottleneck: At the bottleneck of the U-Net (the deepest layer), project the feature map into a sequence of embeddings. Pass them through two stacked Transformer layers (unlike TransBTS's one) with multi-head self-attention to capture long-range dependencies [30].

- 3D CNN Decoder: Build a decoder with four upsampling stages using 3D transposed convolutions. Incorporate skip connections from the encoder's CBAM-refined feature maps.

Training Configuration:

- Loss Function: Employ a combined loss of Dice and Cross-Entropy.

- Optimizer: AdamW optimizer with a weight decay of 1e-5.

- Learning Rate: Use a learning rate scheduler with warm-up.

- Batch Size: Use a small batch size (e.g., 1 or 2) due to GPU memory constraints of 3D volumes.

Evaluation:

- Submit the segmentation results of the BraTS2021 validation and test sets to the official online evaluation platform.

- The model should be evaluated on the median Dice score and Hausdorff Distance (95%) for the Whole Tumor, Tumor Core, and Enhancing Tumor [30].

Model Architecture and Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the typical structure of a hybrid CNN-Transformer model, which integrates the strengths of both architectural paradigms for precise brain tumor segmentation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section catalogs essential resources for developing and benchmarking automated brain tumor segmentation models.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Brain Tumor Segmentation Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Key Features / Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| BraTS Dataset [29] [30] | Benchmark Data | The primary benchmark for training and evaluating brain tumor segmentation algorithms. | - Multi-institutional, multi-parametric MRI (T1, T1c, T2, FLAIR)- Annotated tumor subregions (ET, TC, WT)- Updated annually (e.g., 2,000+ cases in BraTS2021) |

| nnU-Net [3] [21] | Software Framework | An out-of-the-box segmentation tool that automatically configures the entire training pipeline. | - Automates network architecture, preprocessing, and training- Reproducible state-of-the-art performance- Baseline for method comparison |

| Dice Similarity Coefficient (Dice) [7] [3] | Evaluation Metric | Quantifies the spatial overlap between the automated segmentation and the ground truth mask. | - Primary metric for segmentation accuracy- Robust to class imbalance- Ranges from 0 (no overlap) to 1 (perfect overlap) |

| Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) [30] | Algorithmic Module | Integrated into CNN architectures to adaptively refine features by emphasizing important channels and spatial regions. | - Lightweight, plug-and-play module- Improves model performance with minimal computational overhead- Available for 2D and 3D CNNs |

| Hausdorff Distance (HD95) [29] [30] | Evaluation Metric | Measures the largest segmentation error between boundaries, using the 95th percentile for robustness. | - Critical for assessing the accuracy of tumor boundary delineation- Important for surgical planning and radiotherapy |

The accurate segmentation of brain tumors from Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is a cornerstone of modern neuro-oncology, influencing diagnosis, treatment planning, and therapeutic monitoring [8]. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have revolutionized this domain, and among them, the U-Net architecture has emerged as a predominant framework for biomedical image segmentation [32] [33]. Its design is particularly suited to medical applications where annotated data is often scarce. However, the standard U-Net architecture faces challenges when segmenting the complex and heterogeneous structures of brain tumors, which can vary greatly in size, shape, and location [33].

To address these limitations, the core U-Net has been significantly enhanced through advanced architectural modifications. Two of the most impactful innovations are residual connections and attention mechanisms [34] [35]. Residual connections help mitigate the vanishing gradient problem, enabling the training of deeper, more powerful networks [35]. Attention mechanisms, conversely, allow the network to dynamically focus its resources on the most relevant regions of the input image, such as tumor boundaries, while suppressing irrelevant background information [34] [33]. Framed within the context of automated tumor segmentation for brain MRI, this article provides a detailed examination of the U-Net architecture, its key variants, and the experimental protocols that demonstrate their superior performance in current research.

Core U-Net Architecture and Evolutionary Variants

The original U-Net, introduced in 2015, features a symmetric encoder-decoder structure with skip connections [35]. The encoder (contracting path) progressively downsamples the input image, learning hierarchical feature representations. The decoder (expansive path) upsamples these features back to the original input resolution, producing a segmentation map. The critical innovation lies in the skip connections, which concatenate feature maps from the encoder to the decoder at corresponding levels. This allows the decoder to leverage both high-level semantic information and low-level spatial details, enabling precise localization [35].

While powerful, the standard U-Net has limitations, including potential training instability in very deep networks and a lack of selective focus in its skip connections. This has spurred the development of sophisticated variants, as summarized below.

Key U-Net Variants: A Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Comparison of Core U-Net Architectures and Their Applications in Tumor Segmentation

| Architecture | Core Innovation | Mechanism & Advantages | Primary Use-Cases in Tumor Segmentation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original U-Net [35] | Encoder-decoder with skip connections | Combines contextual information (encoder) with spatial precision (decoder via skip connections); effective with limited data. | Foundational model; cell/tissue segmentation. |

| Residual UNet (ResUNet) [34] [35] | Residual blocks within layers | Uses residual (skip) connections within blocks; alleviates vanishing gradients, enables deeper networks, stabilizes training. | Brain tumor segmentation, cardiac MRI analysis, subtle feature detection. |

| Attention UNet [34] [35] | Attention gates in skip connections | Dynamically weights encoder features before concatenation; suppresses irrelevant regions, highlights critical structures. | Pancreas segmentation, small liver lesions, complex tumor boundaries. |

| RSU-Net [36] | Combines residuals & self-attention | Residual connections ease training; self-attention mechanism at bottom aggregates global context for a larger receptive field. | Cardiac MRI segmentation (addressing unclear boundaries). |

| Multi-Scale Attention U-Net [33] | Multi-scale kernels & pre-trained encoder | Uses (1\times1, 3\times3, 5\times5) kernels to capture features at different scales; EfficientNetB4 encoder enhances feature extraction. | Brain tumor segmentation with high variability in size/shape. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical evolution and relationships between these key U-Net variants:

Quantitative Performance in Brain Tumor Segmentation

Recent studies demonstrate that enhanced U-Net models achieve state-of-the-art performance on public brain tumor datasets. The integration of powerful pre-trained encoders and advanced loss functions has been particularly impactful.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Advanced U-Net Models on Brain Tumor Segmentation

| Model Architecture | Encoder Backbone / Key Feature | Dataset | Dice Coefficient | Intersection over Union (IoU) | Accuracy | Reference Metric (AUC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VGG19-based U-Net [32] | VGG-19 (fixed pre-trained weights) | TCGA Lower-Grade Glioma | 0.9679 | 0.9378 | - | 0.9957 |

| Multi-Scale Attention U-Net [33] | EfficientNetB4 | Figshare Brain Tumor | 0.9339 | 0.8795 | 99.79% | - |

| 3D U-Net (iSeg) [37] | 3D U-Net for Lung Tumors | Multicenter Lung CT (Internal Cohort) | 0.73 (median) | - | - | - |

The experimental results underscore significant advancements. The VGG19-based U-Net established a very high benchmark, leveraging transfer learning to extract rich features [32]. The Multi-Scale Attention U-Net further pushed performance boundaries by integrating multi-scale convolutions and an EfficientNetB4 encoder, achieving exceptional accuracy on the Figshare dataset [33]. For context, a 3D U-Net model (iSeg) developed for lung tumor segmentation on CT images demonstrated robust performance (Dice 0.73) across multiple institutions, highlighting the generalizability and clinical utility of the U-Net framework in oncology [37].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and facilitate further research, this section outlines detailed methodologies from key studies on brain tumor segmentation.

Protocol 1: VGG19 U-Net with Transfer Learning

This protocol is based on a study that achieved an AUC of 0.9957 for segmenting FLAIR abnormalities in lower-grade gliomas [32].

- Dataset: The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) lower-grade glioma collection (MRI scans and FLAIR abnormality segmentation masks).

- Model Architecture:

- Encoder: VGG19 with fixed pre-trained weights (transfer learning).

- Decoder: Symmetric to the encoder, with skip connections.

- Loss Function: Focal Tversky Loss (parameters: (\textrm{alpha}=0.7), (\textrm{gamma}=0.75)) to handle class imbalance.

- Training Strategy:

- Optimizer: Aggressive learning rate of 0.05.

- Stabilization: Batch normalization layers are used to stabilize training with the high learning rate.

- Preprocessing: Utilizes standard techniques including image registration and bias field correction.

Protocol 2: Multi-Scale Attention U-Net with EfficientNetB4

This protocol details the methodology for a model that achieved 99.79% accuracy on the Figshare brain tumor dataset [33].

- Dataset: Publicly available Figshare brain tumor dataset (MRI).

- Model Architecture:

- Encoder: EfficientNetB4 (pre-trained) for optimized feature extraction.

- Decoder: U-Net decoder with integrated Multi-Scale Attention Mechanism.

- Attention Module: Employs parallel convolutional layers with (1\times1), (3\times3), and (5\times5) kernels to capture tumor features and boundaries at multiple scales.

- Training Details:

- Preprocessing: Standard techniques including Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE), Gaussian blur, and intensity normalization. The model does not rely heavily on data augmentation, demonstrating inherent generalization.

- Evaluation: Comprehensive metrics including Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC), IoU, Mean IoU, Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and Specificity.

The workflow for implementing and evaluating these models is systematic, as shown below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section catalogues essential computational "reagents" and tools critical for developing automated tumor segmentation models.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for AI-Based Tumor Segmentation

| Tool / Component | Type / Category | Function in Research | Exemplar Use-Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Encoders (VGG19, EfficientNetB0-B7) [32] [33] | Model Component / Feature Extractor | Provides powerful, transferable feature representations from natural images; boosts performance, especially with limited medical data. | VGG19 encoder in U-Net for brain tumor segmentation [32]. |

| Focal Tversky Loss [32] | Loss Function | Addresses severe class imbalance by focusing on hard-to-classify pixels and optimizing for tumor boundaries. | Used with VGG19-U-Net for segmenting FLAIR abnormalities [32]. |

| Dice Loss / Cross-Entropy Hybrid [36] | Loss Function | Combines benefits of distributional learning (CE) and overlap-based optimization (Dice), leading to stable training and good convergence. | Used in RSU-Net for cardiac MRI segmentation [36]. |

| 3D U-Net Architecture [37] | Model Architecture | Extends U-Net to volumetric data, enabling segmentation using full 3D contextual information from multi-slice scans (e.g., CT, MRI). | iSeg model for gross tumor volume (GTV) segmentation in lung CT [37]. |

| AI-based Acceleration (ACS) [22] | Reconstruction Software / MRI Protocol | FDA-approved AI-compressed sensing drastically reduces MRI scan times, decreasing motion artifacts and increasing patient throughput. | Accelerating whole-body MR protocols in clinical practice [22]. |

Discussion and Future Directions

The integration of residual connections and attention mechanisms has profoundly advanced the U-Net's capabilities for brain tumor segmentation. Residual connections facilitate the training of deeper networks, unlocking more complex feature representations [35]. Attention mechanisms, particularly the multi-scale variants, allow the network to dynamically focus on diagnostically relevant regions, such as complex tumor boundaries and small lesions, while ignoring irrelevant healthy tissue [34] [33]. This leads to more accurate and robust segmentation performance.