Advanced Artifact Removal in Neurotechnology: From Foundational Principles to Cutting-Edge AI Applications

This comprehensive review examines state-of-the-art artifact removal techniques in neurotechnology signal processing, addressing the critical challenge of distinguishing genuine neural signals from contamination across EEG, ECoG, and intracortical recordings.

Advanced Artifact Removal in Neurotechnology: From Foundational Principles to Cutting-Edge AI Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive review examines state-of-the-art artifact removal techniques in neurotechnology signal processing, addressing the critical challenge of distinguishing genuine neural signals from contamination across EEG, ECoG, and intracortical recordings. We explore foundational artifact characterization, methodological innovations spanning traditional signal processing to modern deep learning architectures, optimization strategies for clinical and research applications, and rigorous validation frameworks. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this synthesis of current literature provides both theoretical understanding and practical implementation guidance, with particular emphasis on emerging machine learning approaches that are revolutionizing artifact handling in brain-computer interfaces, neuroprosthetics, and clinical neuroscience.

Understanding Neural Signal Contamination: Sources, Characteristics, and Impact

In the field of neurotechnology signal processing, the accurate distinction between authentic neural activity and artifacts is a foundational challenge. Artifacts, defined as any recorded signals that do not originate from the brain's electrical activity, significantly compromise data integrity and can lead to misinterpretation in both research and clinical applications [1]. The amplitude of electroencephalography (EEG) signals typically ranges from microvolts to tens of microvolts, making them particularly susceptible to contamination from various sources that can be orders of magnitude larger [1]. For instance, ocular artifacts can reach 100–200 µV, vastly exceeding the amplitude of cortical signals [1]. Within the context of advanced artifact removal research, a critical first step involves the systematic classification of these contaminating signals into physiological and non-physiological categories. This classification is not merely academic; it directly informs the selection of appropriate detection and removal algorithms, as the characteristics and origins of these artifacts demand tailored processing strategies [2] [1]. This document provides a detailed framework for understanding these artifact sources, supported by quantitative data, experimental protocols, and visualization tools essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working in neurotechnology.

Artifact Classification and Characteristics

Artifacts in neural signals are broadly categorized based on their origin. Physiological artifacts arise from the subject's own biological processes, while non-physiological artifacts (also termed technical artifacts) stem from external sources, instrumentation, or the environment [3] [1]. The following sections delineate these categories in detail.

Physiological Artifacts

Physiological artifacts are generated by the body's electrical or mechanical activities. Their key characteristic is a potential overlap in frequency and topography with genuine neural signals, making them particularly challenging to remove without affecting the signal of interest [3].

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Physiological Artifacts

| Artifact Type | Origin | Typical Causes | Time-Domain Signature | Frequency-Domain Signature | Topographical Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ocular (EOG) | Corneo-retinal dipole (eye) [1] | Blinks, saccades, lateral gaze [1] | Sharp, high-amplitude deflections [1] | Dominant in delta/theta bands (0.5–8 Hz) [1] | Primarily frontal (e.g., Fp1, Fp2) [1] |

| Muscle (EMG) | Muscle contractions [1] | Jaw clenching, swallowing, talking [1] | High-frequency, burst-like noise [1] | Broadband, dominates beta/gamma (>13 Hz) [1] | Temporal, frontal, and neck regions [3] |

| Cardiac (ECG/ Pulse) | Electrical activity of the heart [3] | Heartbeat [1] | Rhythmic, spike-like waveforms [1] | Overlaps multiple EEG bands [1] | Central, posterior, or neck-adjacent channels [1] |

| Respiration | Chest/head movement [1] | Breathing cycles [1] | Slow, rhythmic waveforms [1] | Very low frequency (delta band) [1] | Widespread, often frontal |

| Perspiration | Sweat gland activity [1] | Heat, stress, long recordings [1] | Very slow baseline drifts [1] | Very low frequency (delta/theta) [1] | Widespread, can short electrodes |

Non-Physiological Artifacts

Non-physiological artifacts originate from the recording environment, hardware, or experimental setup. They are often more easily prevented or removed due to their distinct, often non-biological, characteristics [3] [1].

Table 2: Characteristics of Common Non-Physiological Artifacts

| Artifact Type | Origin | Typical Causes | Time-Domain Signature | Frequency-Domain Signature | Topographical Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode Pop | Sudden impedance change [1] | Drying gel, cable motion, poor contact [1] | Abrupt, high-amplitude transient [1] | Broadband, non-stationary [1] | Typically isolated to a single channel [1] |

| Cable Movement | Cable motion/ interference [1] | Tugging cables, subject movement [1] | Sudden deflections or rhythmic drift [1] | Artificial peaks at low/mid frequencies [1] | Can affect multiple channels |

| AC Power Line | Electromagnetic interference [1] | AC power (50/60 Hz), unshielded cables [1] | Persistent high-frequency oscillation [1] | Sharp peak at 50/60 Hz and harmonics [1] | Global across all channels |

| Incorrect Reference | Faulty reference electrode [1] | Omitted reference, dried gel [1] | High-amplitude shift across all channels [1] | Abnormally high global power [1] | Global across all channels |

| Motion Artifact | Head/body movement [4] | Gross motor activity, walking [1] | Large, low-frequency noise bursts [2] | Dominates lower frequencies | Widespread |

Quantitative Performance of Artifact Detection Methods

Recent advances in artifact management have demonstrated the efficacy of specialized computational approaches. The following table summarizes performance metrics from contemporary studies, highlighting the advantage of artifact-specific models.

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Modern Artifact Detection Algorithms

| Detection Method | Artifact Target | Key Performance Metric | Reported Value | Optimal Parameters | Source Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Lightweight CNN [5] | Eye Movements | ROC AUC | 0.975 | 20s temporal window | TUH EEG Corpus [5] |

| Deep Lightweight CNN [5] | Muscle Activity | Accuracy | 93.2% | 5s temporal window | TUH EEG Corpus [5] |

| Deep Lightweight CNN [5] | Non-Physiological | F1-Score | 77.4% | 1s temporal window | TUH EEG Corpus [5] |

| CNN vs. Rule-Based [5] | Various | Avg. F1-Score Improvement | +11.2% to +44.9% | Artifact-specific windows | TUH EEG Corpus [5] |

| NeuroClean Pipeline [6] | Mixed Artifacts | Classification Accuracy | 97% (vs. 74% on raw data) | Motor imagery task | LFP Data [6] |

| Victor-Purpura Metric [7] | Eye Blink Timing | Music Decoding Accuracy | 56% (chance: 25%) | Cost factor (q) tuning | Music Imagery Dataset [7] |

Experimental Protocols for Artifact Management

Protocol: Deep Lightweight CNN for Specific Artifact Detection

This protocol is adapted from a study that developed specialized convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for detecting distinct artifact classes, demonstrating significant superiority over traditional rule-based methods [5].

1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Source: Utilize the Temple University Hospital (TUH) EEG Corpus or a similar dataset with expert-annotated artifact labels (κ > 0.8 is ideal for reliability) [5].

- Standardization: Resample all recordings to a uniform sampling rate (e.g., 250 Hz). Apply a bandpass filter (e.g., 1–40 Hz) and a notch filter (50/60 Hz) to remove line noise [5].

- Montage & Referencing: Convert signals to a standardized bipolar montage. Apply average referencing to reduce common-mode noise and remove DC offsets [5].

- Normalization: Use global normalization (e.g., RobustScaler) across all channels and timepoints to standardize the input range for stable model training [5].

2. Adaptive Segmentation:

- Segment the continuous EEG into non-overlapping windows. Critically, use different window lengths optimized for specific artifacts: 20s for eye movements, 5s for muscle activity, and 1s for non-physiological artifacts, based on validation performance [5].

3. CNN Model Training:

- Develop and train three distinct CNN systems, each dedicated to one primary artifact class (eye movement, muscle, non-physiological).

- Train the models on a held-out training set, using the annotated artifacts as ground truth labels.

- Compare the performance against standard rule-based clinical detection methods on a separate test set, using metrics such as F1-score, ROC AUC, and accuracy [5].

4. Validation:

- Perform cross-validation and report performance metrics for each artifact-specific model separately. The expected outcome is a significant improvement in F1-score (e.g., +11.2% to +44.9%) over rule-based methods [5].

Protocol: Automated Artifact Removal with NeuroClean Pipeline

This protocol outlines the use of an unsupervised, automated pipeline for conditioning EEG and LFP data, validated via subsequent classification task performance [6].

1. Bandpass Filtering:

- Apply a Butterworth bandpass filter (e.g., 1 Hz to 500 Hz) to reduce very low and high-frequency noise. If the signal sampling rate is below 500 Hz, adjust the upper band accordingly [6].

2. Line Noise Removal:

- Use the ZapLine filter (or similar) to remove power supply noise (e.g., 50/60 Hz) and its harmonics. This method employs spectral and spatial filtering to target line frequencies without broadly affecting the signal [6].

3. Bad Channel Rejection:

- Identify and reject broken or artifact-ridden channels using an iterative algorithm based on standard deviation (SD) features.

- Criteria for rejection include: SD above the 75th percentile, SD below 0.1 µV, or SD above 100 µV. Iterate until no new bad channels are detected or a maximum number of iterations (e.g., 5) is reached [6].

4. Independent Component Analysis (ICA) with Cluster-MARA:

- Perform ICA (e.g., using FastICA) to decompose the signal into statistically independent components.

- Instead of relying on pre-trained models, use the Cluster-MARA algorithm to automatically reject artifactual components. This involves:

- Extracting features from each component (e.g., spatial range, average log band power in 8-13 Hz).

- Clustering components based on these features to identify and remove artifact clusters [6].

5. Validation via Classification Task:

- To objectively assess the pipeline's utility without a "ground truth" clean signal, evaluate the cleaned data in a machine learning classification task (e.g., motor imagery).

- The performance (e.g., accuracy of a Multinomial Logistic Regression model) on the cleaned data should show a substantial improvement compared to the raw data (e.g., >97% vs. 74%) [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key Resources for Artifact Management Research

| Item Name | Type | Critical Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| TUH EEG Artifact Corpus [5] | Dataset | Provides a large, expert-annotated public dataset for developing and benchmarking artifact detection algorithms. |

| Standardized Bipolar Montage [5] | Signal Processing Technique | Reduces common-mode noise and standardizes channel configuration across diverse recording setups. |

| RobustScaler [5] | Normalization Algorithm | Preserves relative amplitude relationships between channels while standardizing input for stable model training. |

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) [6] [8] | Blind Source Separation Algorithm | Decomposes multi-channel EEG into independent sources, facilitating the identification and removal of artifactual components. |

| Cluster-MARA [6] | Machine Learning Classifier | An automated, unsupervised algorithm for rejecting artifactual ICA components without requiring pre-trained models. |

| Victor-Purpura Spike Train Distance [7] | Metric | Quantifies the dissimilarity between temporal event sequences (e.g., blink times), useful for analyzing artifact timing patterns. |

| BioSemi Active II System [7] | EEG Hardware | Example of a high-density (64-electrode) research-grade EEG system used for acquiring high-quality data. |

| BLINKER [7] | Software Tool | A specialized algorithm for the automated detection and extraction of eye-blink times from EEG data or ICA components. |

In electroencephalography (EEG) and related neurotechnologies, physiological artifacts are signals recorded by the system that do not originate from brain neural activity. These artifacts present a significant challenge for signal processing, particularly in the context of drug development and clinical research, where the accurate interpretation of neural signals is paramount. Contamination from ocular, muscle, and cardiac activity can obscure genuine brain activity, mimic pathological patterns, or introduce confounding variables in experimental data, potentially leading to misdiagnosis or flawed research conclusions [1]. The relaxed constraints of modern wearable EEG systems, which enable monitoring in real-world environments, further amplify these challenges due to factors such as dry electrodes, reduced scalp coverage, and subject mobility [9]. Therefore, the precise identification and removal of these artifacts is a critical step in the neurotechnology signal processing pipeline to ensure data integrity and the reliability of subsequent analyses.

Ocular Artifacts (EOG)

Origin and Characteristics

Ocular artifacts, primarily caused by eye blinks and movements, are among the most common and prominent sources of contamination in EEG signals. The eye acts as an electric dipole due to the charge difference between the cornea (positively charged) and the retina (negatively charged). When the eye moves or the eyelid closes during a blink, this dipole shifts, generating a large electric field disturbance that is measurable on the scalp [1]. The electrooculogram (EOG) signal associated with these activities typically reaches amplitudes of 100–200 µV, often an order of magnitude larger than the underlying neural EEG signals, which are in the microvolt range [1]. This amplitude disparity makes ocular artifacts particularly disruptive.

- Time-Domain Signature: Ocular artifacts manifest as slow, high-amplitude deflections in the EEG signal. They are most prominent over frontal electrodes (e.g., Fp1, Fp2) due to their proximity to the eyes. The morphology of the artifact is directly related to the nature of the eye movement; blinks produce symmetric, broad deflections, while saccades generate sharper, more transient waveforms [1].

- Frequency-Domain Signature: The spectral energy of ocular artifacts is dominant in the low-frequency delta (0.5–4 Hz) and theta (4–8 Hz) bands. This overlap with frequencies of interest for cognitive neuroscience and clinical studies means that uncorrected artifacts can be misinterpreted as genuine slow-wave neural activity [1].

Quantitative Profile of Ocular Artifacts

Table 1: Characteristics of Ocular (EOG) Artifacts

| Feature | Specification | Impact on EEG Signal |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Origin | Corneo-retinal dipole (eye) [1] | Large amplitude signals swamp neural data. |

| Typical Causes | Blinks, saccades, lateral gaze [1] | Obscures underlying brain activity. |

| Amplitude Range | 100–200 µV [1] | Can be 10-20x larger than cortical EEG. |

| Spectral Overlap | Delta (0.5–4 Hz) and Theta (4–8 Hz) bands [1] | Mimics cognitive or pathological slow waves. |

| Spatial Distribution | Maximal over frontal electrodes (Fp1, Fp2) [1] | Localized contamination, but can spread. |

Experimental Protocol for Ocular Artifact Removal

Objective: To effectively identify and remove ocular artifacts from multi-channel EEG data using Independent Component Analysis (ICA), preserving the integrity of the underlying neural signals.

Workflow:

Materials and Reagents:

- Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Ocular Artifact Management

Item Function/Description EEG System with EOG Reference A minimum 2-channel setup for recording horizontal and vertical eye movements. Essential for reference-based methods [10]. Blind Source Separation (BSS) Toolbox Software implementation (e.g., EEGLAB, MNE-Python) containing algorithms like FastICA for signal decomposition [10]. High-Pass Filter (Cutoff: 0.5-1 Hz) Removes very slow drifts, improving the stability and performance of ICA [1].

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Record continuous EEG data alongside a dedicated EOG reference channel. The EOG channel is typically placed near the eyes to capture the ocular signal directly.

- Preprocessing: Apply a band-pass filter (e.g., 1.5–40 Hz) to the raw data to remove slow drifts and high-frequency noise. Segment the data into epochs if required by the experimental paradigm [10].

- ICA Decomposition: Use an ICA algorithm (e.g., FastICA) to decompose the preprocessed EEG data into statistically independent components (ICs). Each IC represents a source signal that contributed to the scalp recording.

- Component Identification: Identify ICs corresponding to ocular artifacts. This can be achieved through:

- Reference Correlation: Calculating the correlation (e.g., using Pearson correlation or the Randomized Dependence Coefficient - RDC) between each IC and the EOG reference channel. Components with high correlation are flagged as artifacts [10].

- Topographical & Spectral Analysis: Visually inspecting the scalp topography of the IC (should show strong frontal weighting) and its power spectrum (should be dominated by low frequencies) [1].

- Component Removal: Subtract the identified artifact components from the original data matrix.

- Signal Reconstruction: Reconstruct the clean EEG signal from the remaining neural components.

- Validation: Qualitatively inspect the cleaned data for the absence of large frontal deflections corresponding to blinks or eye movements. Quantitatively, calculate the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) improvement in the frontal channels [10].

Muscle Artifacts (EMG)

Origin and Characteristics

Muscle artifacts arise from the electrical activity produced by muscle contractions, known as electromyography (EMG). These artifacts are a major concern in EEG analysis due to their broad spectral characteristics and high amplitude. Even minor contractions of the frontalis, temporalis, or masseter muscles during jaw clenching, swallowing, talking, or frowning can generate significant EMG signals [1]. Unlike the relatively localized and low-frequency ocular artifacts, muscle artifacts are broadband and can affect a wide range of electrodes.

- Time-Domain Signature: EMG artifacts appear as high-frequency, spiky, and irregular activity superimposed on the EEG signal. The amplitude is directly proportional to the strength of the muscle contraction [1].

- Frequency-Domain Signature: The spectral content of EMG is broadband, dominating the beta (13–30 Hz) and gamma (>30 Hz) ranges. This overlap poses a significant challenge for studying high-frequency neural oscillations, which are crucial for understanding cognitive processes and motor functions [1].

Quantitative Profile of Muscle Artifacts

Table 3: Characteristics of Muscle (EMG) Artifacts

| Feature | Specification | Impact on EEG Signal |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Origin | Muscle fiber contractions (EMG) [1] | Injects high-frequency noise into the signal. |

| Typical Causes | Jaw clench, swallowing, talking, head movement [1] | Creates widespread, irregular contamination. |

| Amplitude Range | Variable, can be very high | Obscures genuine brain signals. |

| Spectral Overlap | Beta (13–30 Hz) and Gamma (>30 Hz) bands [1] | Masks high-frequency cognitive/motor rhythms. |

| Spatial Distribution | Widespread, often maximal over temporal sites | Can corrupt signals across the scalp. |

Experimental Protocol for Muscle Artifact Removal

Objective: To detect and suppress myogenic contamination using advanced signal processing techniques, such as wavelet transforms or deep learning, which are effective for non-stationary, high-frequency noise.

Workflow:

Materials and Reagents:

- Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Muscle Artifact Management

Item Function/Description Wavelet Toolbox Software library (e.g., in MATLAB or Python's PyWavelets) for performing multi-resolution signal analysis and thresholding [9]. Deep Learning Framework Framework such as TensorFlow or PyTorch for implementing and training models like CNN-LSTM hybrids or Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [11]. Curated Dataset A dataset containing paired contaminated and clean EEG signals for training and validating data-driven models like GANs [11].

Procedure (Wavelet-Based Approach):

- Wavelet Transform: Decompose the raw EEG signal into different frequency sub-bands using a discrete wavelet transform. This decomposition separates the signal into approximation coefficients (low-frequency trends) and detail coefficients (high-frequency information).

- Coefficient Analysis: Identify detail coefficients that correspond to the high-frequency EMG artifact. Apply a thresholding rule (e.g., soft or hard thresholding) to these coefficients to attenuate the artifact power while preserving neural information.

- Inverse Transform: Reconstruct the denoised EEG signal from the thresholded wavelet coefficients using the inverse wavelet transform.

Procedure (Deep Learning Approach):

- Model Selection: Choose a suitable architecture. For example, a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) can be trained where the generator learns to map artifact-contaminated EEG to clean EEG, and the discriminator learns to distinguish between the cleaned and genuine clean signals [11].

- Model Training: Train the model on a dataset where input (contaminated EEG) and target (clean EEG) pairs are available. The model learns the complex, non-linear relationships between artifacts and neural signals.

- Prediction & Removal: Use the trained model to process new, contaminated EEG data and output the cleaned signal.

Cardiac Artifacts (ECG)

Origin and Characteristics

Cardiac artifacts are caused by the electrical activity of the heart, known as the electrocardiogram (ECG), or the ballistocardiogram (BCG) effect in simultaneous EEG-fMRI recordings. The pulsatile movement of blood in the scalp and head with each heartbeat can also create a potential field detectable by EEG electrodes [1]. While usually weaker than ocular or muscle artifacts, their rhythmic nature can be problematic.

- Time-Domain Signature: Cardiac artifacts appear as rhythmic, sharp waveforms (often resembling the QRS complex of an ECG) that recur at the frequency of the subject's heart rate (typically 60-100 beats per minute, or ~1-1.7 Hz). They are often most visible in electrodes close to the neck and on the earlobes [1].

- Frequency-Domain Signature: The artifact overlaps with several EEG bands, including delta and alpha rhythms. Its fundamental frequency and harmonics can create distinct peaks in the power spectrum [10].

Quantitative Profile of Cardiac Artifacts

Table 5: Characteristics of Cardiac (ECG/BCG) Artifacts

| Feature | Specification | Impact on EEG Signal |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Origin | Heart electrical activity (ECG) or pulse (BCG) [1] | Introduces rhythmic, non-neural signals. |

| Typical Causes | Heartbeat [1] | Consistent, periodic contamination. |

| Amplitude Range | Generally low, but variable | Can be mistaken for pathological spikes. |

| Spectral Overlap | Delta and Alpha bands, with peaks at heart rate [10] | Can be confused with neural oscillations. |

| Spatial Distribution | Maximal at central/neck-adjacent & ear electrodes [1] | Localized, pulse-synchronous signals. |

Experimental Protocol for Cardiac Artifact Removal

Objective: To remove rhythmic cardiac contamination using an ECG reference signal and source separation techniques, ensuring the preservation of concurrent neural oscillations.

Workflow:

Materials and Reagents:

- Table 6: Research Reagent Solutions for Cardiac Artifact Management

Item Function/Description ECG Sensor A dedicated sensor (e.g., a finger clip or chest strap) to record a clear cardiac reference signal [10]. Synchronized Data Acquisition System A system that can record EEG and ECG signals simultaneously with a shared time clock. Event-Related Field (ERF) Analysis Toolbox Software for analyzing evoked responses, used to validate the quality of the cleaned signal in auditory or sensory paradigms [10].

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Record EEG data simultaneously with a dedicated ECG lead to obtain a clear reference of the cardiac cycle.

- Preprocessing: Apply standard band-pass filtering (e.g., 1.5–40 Hz) and epoching to the continuous data.

- ICA Decomposition: Perform ICA on the preprocessed EEG data to separate it into independent components.

- Component Identification: Identify the cardiac artifact component by:

- Temporal Correlation: Correlating the time course of each IC with the R-peaks of the simultaneously recorded ECG signal. The IC with the highest temporal locking to the cardiac cycle is identified as the artifact component [10].

- Component Removal & Signal Reconstruction: Remove the identified cardiac component and reconstruct the EEG signal from the remaining components.

- Validation: Assess the effectiveness of the removal by inspecting the cleaned data for the absence of pulse-synchronous artifacts. Quantitatively, evaluate the improvement in the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of event-related fields (ERFs) or the clarity of auditory evoked potentials [10].

Integrated Analysis and Discussion

The management of physiological artifacts is a non-negotiable prerequisite for robust neurotechnology signal processing, especially in critical applications like drug development where subtle changes in brain activity are monitored. Each major artifact type—ocular, muscular, and cardiac—presents unique spatial, temporal, and spectral signatures, necessitating a tailored approach for its removal [9]. While traditional methods like ICA and wavelet transforms remain pillars in artifact removal pipelines, the field is rapidly evolving. The systematic review by [9] indicates that deep learning approaches are emerging as powerful tools, particularly for complex artifacts like EMG and motion, showing promise for real-time applications in wearable systems.

A critical finding from recent literature is the underutilization of auxiliary sensors, such as Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs), which have significant potential to enhance artifact detection in the ecological conditions typical of wearable EEG use [9]. Furthermore, the performance of artifact removal algorithms is typically assessed using a suite of quantitative metrics, including but not limited to, Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), Signal-to-Artifact Ratio (SAR), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Normalized Mean Square Error (NMSE), which provide objective measures of the quality of the cleaned signal [11]. Future research in neurotechnology artifact removal will likely focus on the development of fully automated, adaptive pipelines that can intelligently identify and remove multiple artifact types without human intervention, thereby increasing the reliability and scalability of brain monitoring in both clinical and real-world settings.

In neurotechnology signal processing, particularly in electroencephalography (EEG) and brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), ensuring data integrity is paramount for both research and clinical applications. Technical artifacts originating from non-physiological sources significantly compromise signal quality, leading to misinterpretation of neural data. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for identifying, characterizing, and mitigating three prevalent technical artifacts: electrode popping, cable movement, and power line interference. This work supports a broader thesis on advanced artifact removal pipelines in neurotechnology, aiming to enhance the reliability of neural signal analysis for drug development and neurological research.

Artifact Characterization and Quantitative Analysis

Technical artifacts exhibit distinct spatial, temporal, and spectral signatures. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each artifact type for systematic identification [12].

Table 1: Characterization of Key Technical Artifacts in EEG Recordings

| Artifact Type | Spatial Distribution | Temporal Signature | Spectral Signature | Primary Cause |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode Pop | Highly localized to a single channel [12] | Sudden, discrete DC shift or signal drop-out; signal goes out of range [12] | Broadband, non-rhythmic | Loose electrode or poor skin contact [12] |

| Cable Movement | Can affect multiple channels on the same cable | Sudden, high-amplitude, non-stereotypical changes in the time domain [12] | Broadband | Triboelectric noise from conductor friction or motion in a magnetic field [12] |

| Power Line Interference | Widespread, often global across all channels | Frequent, monotonous waves at 50 Hz or 60 Hz [12] | Sharp peak at 50/60 Hz and its harmonics [12] | Environmental electromagnetic interference from mains power [12] |

The performance of artifact management strategies is quantified using specific metrics. The following table outlines common assessment parameters and reported performance values from recent research, providing benchmarks for evaluating new methodologies [9].

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Artifact Management Pipelines in Wearable Neurotechnology

| Performance Metric | Definition | Typical Benchmark (from literature) | Common Reference Signal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Overall correctness of artifact detection | ~71% (when clean signal is available as reference) [9] | Simultaneously recorded clean signal [9] |

| Selectivity | Ability to correctly identify clean EEG segments | ~63% [9] | Physiological brain signal [9] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) Improvement | Reduction in noise power relative to signal post-processing | Varies by technique and artifact severity | Pre- and post-processing signal segments |

Experimental Protocols for Artifact Investigation

Protocol for Inducing and Recording Electrode Popping Artifacts

Objective: To systematically generate and characterize electrode popping artifacts for validating detection algorithms. Materials: EEG acquisition system, standard Ag/AgCl electrodes, conductive paste, scalp phantom or human participant, impedance meter. Methodology:

- Setup: Apply electrodes to the scalp or phantom according to a standard 10-20 system. Ensure all electrodes have low impedance (<5 kΩ).

- Baseline Recording: Record a 5-minute baseline EEG with all electrodes secure.

- Artifact Induction: Gradually loosen a single designated electrode (e.g., C4) to simulate poor contact. This can be done by slightly retracting the electrode or reducing the amount of conductive paste.

- Data Acquisition: Record EEG activity during the induction phase. Continuously monitor impedance values if supported by the amplifier.

- Validation: Mark the timestamps of induced pops. The resulting data should show sudden, large-amplitude deflections localized to the loosened channel, as characterized in Table 1 [12]. Analysis: Apply proposed detection algorithms (e.g., threshold-based outlier detection, kurtosis measures) to the recorded data and compute accuracy and selectivity against the ground truth timestamps.

Protocol for Studying Cable Movement Artifacts

Objective: To investigate the properties of artifacts induced by cable motion under controlled conditions. Materials: Wireless and wired EEG systems, motion platform (or manual controlled movement), IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit) sensors (optional but recommended). Methodology:

- Controlled Setup: Fit a participant or mannequin head with a standard EEG cap connected via a wired system.

- Stationary Baseline: Record a 5-minute EEG segment with the participant remaining completely still.

- Motion Paradigm: Execute a series of standardized movements:

- Slow, repetitive torso rotations.

- Sudden head turns.

- Gentle tugging and swaying of the electrode cable bundle.

- Synchronized Monitoring: Synchronize EEG recording with motion tracking data from the IMU attached to the cable or the participant's head.

- Control Condition: Repeat the motion paradigm using a wireless EEG system or a system with actively shielded cables to benchmark the artifact reduction [12]. Analysis: Correlate motion sensor data with EEG signal anomalies. Characterize the amplitude and frequency content of the motion artifacts. Evaluate the effectiveness of motion filters and common average reference techniques in mitigating these artifacts.

Protocol for Mapping Power Line Interference

Objective: To assess the spatial distribution and intensity of power line interference in a lab environment. Materials: EEG system, a phantom head filled with conductive saline, spectrum analyzer (optional). Methodology:

- Environmental Setup: Place the saline phantom in the typical experimental setting.

- Recording: Record "EEG" from the phantom with no active signal source. This captures the ambient electromagnetic noise.

- Spatial Mapping: Systematically move the phantom and/or the acquisition system to different locations in the lab (e.g., near power outlets, far from walls, under lighting) and repeat the recording.

- Spectral Analysis: Perform a Fourier Transform on the recorded data from each location and channel.

- Analysis: Identify and quantify the peak magnitudes at 50/60 Hz and their harmonics. Create a spatial map of the lab indicating high-interference zones. This data is critical for optimizing lab setup. Mitigation Validation: Test the efficacy of hardware solutions (active shielding [12]) and post-processing filters (notch filters, adaptive filtering) using the data collected from high-interference zones.

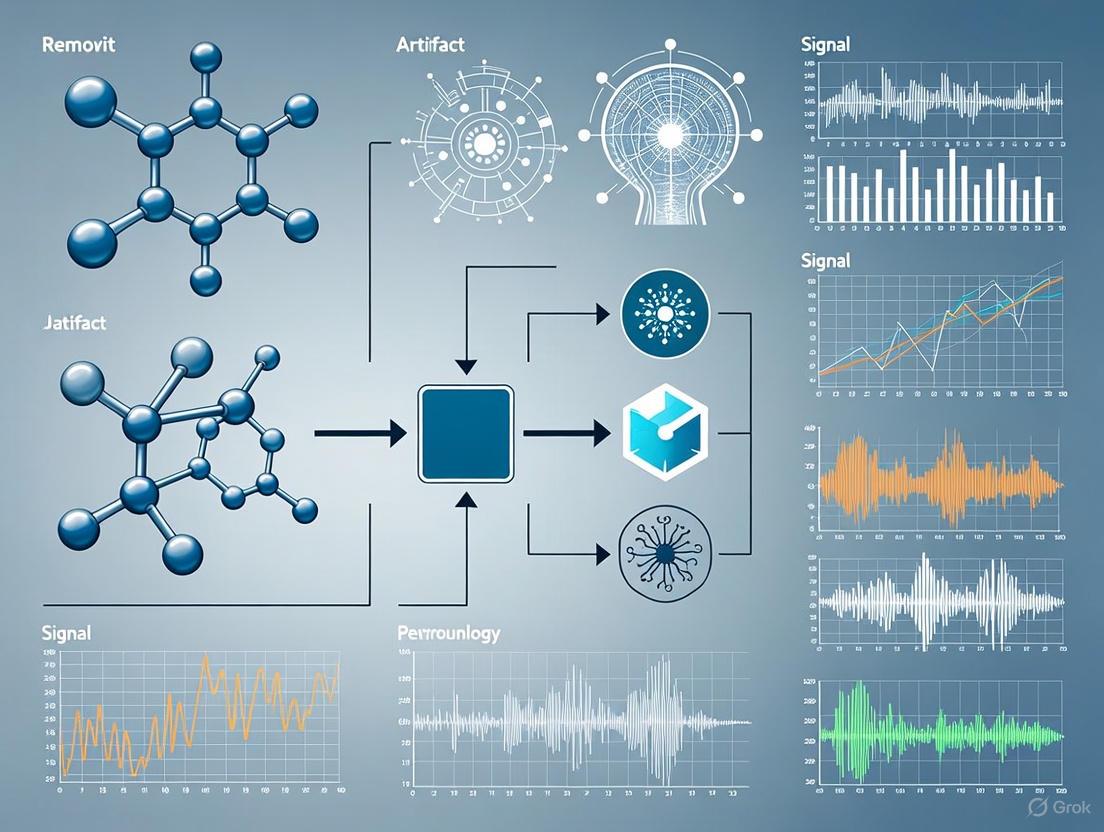

Visualization of Artifact Identification and Mitigation Workflows

The following diagrams outline logical workflows for identifying artifacts and a generalized signal processing pipeline for their mitigation, as discussed in the protocols and literature.

Artifact Identification Workflow

Diagram 1: A decision-tree workflow for identifying technical artifacts based on their spatial, temporal, and spectral characteristics.

Signal Processing Pipeline

Diagram 2: A modular signal processing pipeline for the detection and selective mitigation of multiple technical artifacts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details essential materials and software tools for conducting rigorous research on technical artifacts in neurotechnology.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Technical Artifact Investigation

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Usage in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Active Shielded Cables | Minimizes capacitive coupling and mains interference; reduces triboelectric noise from cable movement [12]. | Used in Protocol 3.2 as a control and in Protocol 3.3 as a primary hardware mitigation strategy. |

| IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit) Sensors | Provides quantitative, synchronized motion data for correlating physical movement with cable and motion artifacts. | Critical for Protocol 3.2 to objectively timestamp and quantify movement. |

| Scalp Phantom (Conductive Saline) | Provides a stable, reproducible "head" model for controlled artifact induction without biological variability. | Used in Protocol 3.3 for mapping environmental power line interference. |

| Notch Filter | Software or hardware filter designed to suppress a narrow frequency band, specifically the 50/60 Hz power line noise [12]. | Applied in Protocol 3.3 and as a standard step in the mitigation pipeline (Diagram 2). |

| Impedance Meter / Monitoring | Measures electrode-skin contact impedance in real-time. High or fluctuating impedance indicates risk of electrode pops [12]. | Used for setup validation in Protocol 3.1 and for diagnosing the cause of pops. |

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) | A blind source separation algorithm used to isolate and remove artifacts, including some cable movement artifacts, from EEG data [9]. | A potential advanced technique for the "Blind Source Separation" module in Diagram 2. |

Artifact Propagation Mechanisms and Volume Conduction Effects

In neurotechnology, the fidelity of neural recordings is paramount for both basic scientific research and clinical applications. The acquisition of these signals, however, is frequently compromised by electrical artifacts introduced during therapeutic or investigative electrical stimulation. These artifacts, which can be several orders of magnitude larger than the neural signals of interest, pose a significant challenge for brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), deep brain stimulation (DBS) systems, and other neural prosthetics [13] [14]. The core mechanism underlying the spread of these disruptive signals is volume conduction—the process by which electrical potentials propagate through biological tissues from their source to recording electrodes at a distance [15]. Understanding these propagation mechanisms is the critical first step in developing effective artifact removal strategies, which in turn are essential for advancing closed-loop and bi-directional neurotechnologies.

Quantitative Characterization of Artifacts

The impact of stimulation artifacts is directly measurable, and their characteristics vary significantly depending on the stimulation modality, parameters, and recording setup.

Table 1: Comparative Amplitudes of Neural Signals and Stimulation Artifacts

| Signal Type | Typical Amplitude | Relative Scale | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Neural Recordings | 110 μV peak-to-peak | 1x | Intracortical microelectrode arrays [13] |

| Intramuscular FES Artifacts | ~440 μV | 4x baseline | Recorded in motor cortex [13] |

| Surface FES Artifacts | ~19.25 mV | 175x baseline | Recorded in motor cortex [13] |

| ECoG Stimulation Artifacts | Up to ±1,100 μV | N/A | Propagated through cortical tissue [16] |

| DBS Artifacts | Up to 3 V | 1,000,000x LFP | Contaminating μV-range Local Field Potentials [14] |

Table 2: Spatial Propagation of Stimulation Artifacts

| Stimulation Modality | Recording Modality | Observed Propagation Distance | Key Spatial Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subdural ECoG Stimulation | ECoG Grid | 4.43 mm to 38.34 mm | Follows electric dipole potential distribution (R² = 0.80 median fit) [16] |

| sEEG Stimulation | sEEG | Modeled via Finite Element Method (FEM) | Mismatch between measured/simulated potentials modulated by electrode distance [17] |

| Cortical Microstimulation | Linear Multielectrode Array | Across entire array | Highly consistent artifact waveforms across channels [18] |

Mechanisms of Volume Conduction

Volume conduction, often termed "electrical spread," describes the phenomenon where electrical potentials are measured at a distance from their source through a conducting medium [15]. In the context of neural recording, the tissues between the stimulation site and the recording electrode—such as skin, skull, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and brain tissue—form this medium. These tissues possess distinct electrical conductivity properties, which cause the electrical signals to spread, refract, and alter in appearance by the time they reach the recording electrodes [15].

A key concept for understanding artifact propagation is the distinction between near-field and far-field potentials. Near-field potentials are recorded relatively close to their source, while far-field potentials are recorded at a distance and are most relevant to artifacts that propagate to the cortical surface or to distant intracranial locations [15]. Empirical and modeling studies have demonstrated that the spatial distribution of artifacts from cortical stimulation closely follows the potential distribution of an electric dipole [16]. This model provides a powerful framework for predicting the amplitude and spread of artifacts across an electrode array, which is invaluable for both hardware design and signal processing.

Figure 1: Signaling pathway of artifact propagation via volume conduction. Electrical stimulation injects current into biological tissues, creating far-field potentials that propagate to recording electrodes and obscure true neural signals.

Experimental Protocols for Characterization and Removal

Protocol for Characterizing Artifact Propagation

Objective: To empirically map the spatial and temporal characteristics of stimulation artifacts in an ECoG or sEEG setup [16] [17].

- Setup and Subjects: Conduct studies during eloquent cortex mapping procedures in epilepsy patients implanted with subdural ECoG grids or sEEG electrodes. The placement of electrodes is determined solely by clinical needs.

- Stimulation Parameters: Use a clinical cortical stimulator to deliver biphasic square pulse trains. Typical parameters include:

- Pulse Width: 200-250 μs per phase.

- Amplitude: 2-12 mA (typically in 2 mA increments).

- Epoch Duration: 2-5 seconds of stimulation per channel.

- Configuration: Bipolar stimulation between adjacent electrodes.

- Data Acquisition: Record data continuously throughout the mapping procedure at a sampling rate of at least 512 Hz. Precisely timestamp all stimulation epochs for offline analysis.

- Co-registration: Post-implantation, co-register pre-implantation MRI (or post-explantation MRI) and post-implantation CT images using a non-rigid co-registration toolbox (e.g., Elastix). This step determines the 3D coordinates of each ECoG electrode in reference to the brain anatomy.

- Time-Domain Analysis: Segment data around each stimulation pulse. Characterize artifacts for properties such as phase-locking and "ratcheting" patterns.

- Frequency-Domain Analysis: Compute the power spectral density of the recorded signal during stimulation. Identify broadband power increases and power bursts at the fundamental stimulation frequency and its super-harmonics.

- Spatial Modeling: Fit an electric dipole model to the measured artifact amplitudes across the grid for each stimulation pulse. Evaluate the goodness-of-fit (e.g., R²) to validate the model.

Protocol for Implementing the LRR Artifact Reduction Method

Objective: To reduce stimulation artifacts in intracortical recordings for brain-computer interface applications using the Linear Regression Reference (LRR) method, which outperforms blanking and common average referencing (CAR) [13].

- Neural Data Acquisition: Record from intracortical microelectrode arrays (e.g., 96-channel arrays). Amplify, bandpass filter (0.3 Hz – 7.5 kHz), and digitize (30 kHz) the signals.

- Stimulation Trigger Recording: Record an output trigger signal from the stimulation device to synchronize neural data with stimulation periods.

- LRR Algorithm Application:

- For each recording channel, define a set of other channels to be used as references.

- For every time point, create a channel-specific reference signal as a weighted sum of the signals from the reference channels.

- The weights are computed using linear regression to predict the artifact on the channel of interest based on the reference channels. The underlying assumption is that the highly consistent artifact is shared across channels, while neural signals are more local.

- Subtract the channel-specific reference signal from the channel of interest signal.

- Performance Validation:

- Artifact Magnitude: Quantify the peak-to-peak artifact voltage before and after LRR application. LRR has been shown to reduce large surface FES artifacts to less than 10 μV [13].

- Neural Feature Preservation: Compare standard neural features (e.g., threshold crossings, band power) extracted during non-stimulation and stimulation periods after LRR processing.

- Decoding Performance: Evaluate the performance of an iBCI decoder (e.g., for continuous grasping) during stimulation periods with and without LRR mitigation. LRR has been shown to recover >90% of normal decoding performance during surface stimulation [13].

Figure 2: LRR method workflow. A channel-specific reference is created for each channel via linear regression and subtracted to remove common artifact components.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Intracortical Microelectrode Arrays | High-density arrays (e.g., 96-ch) for recording microvolt-scale neural signals. | Recording motor commands in motor cortex for iBCI control [13]. |

| Percutaneous Intramuscular Electrodes | Implanted stimulating electrodes for Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES). | Activating paralyzed limb muscles in a neuroprosthesis [13]. |

| Subdural ECoG Grids/Strips | Electrode grids placed on the cortical surface for recording and stimulation. | Mapping eloquent cortex and characterizing artifact propagation [16]. |

| Stereotactic EEG (sEEG) Electrodes | Multi-lead depth electrodes implanted deep into brain structures. | Recording and stimulating from deep brain regions; validating volume conduction models [17]. |

| Isolated Bio-stimulator | Battery-powered, isolated stimulator (e.g., custom FES unit, clinical cortical stimulator). | Delivering controlled electrical pulses without introducing noise to recording equipment [13] [16]. |

| Finite Element Method (FEM) Software | Computational tool for creating detailed volume conduction models of the head. | Simulating the propagation of electrical potentials through complex biological tissues [17]. |

| Linear Regression Reference (LRR) Algorithm | A software-based artifact removal method that creates channel-specific reference signals. | Removing FES artifacts from iBCI recordings to restore decoding performance [13]. |

| ERAASR Algorithm | "Estimation and Removal of Array Artifacts via Sequential principal components Regression." | Cleaning artifact-corrupted signals on multielectrode arrays to recover underlying spiking activity [18]. |

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a foundational tool in clinical neurology, neuroscience research, and brain-computer interface (BCI) development. However, the recorded signals are persistently contaminated by artifacts—unwanted signals of non-neural origin—that threaten the validity of all downstream applications [3] [1]. These artifacts can originate from physiological sources like eye movements and muscle activity, or from non-physiological sources such as electrical interference and electrode issues [3] [1]. Effective artifact removal is therefore not merely a preprocessing step but a critical determinant of data integrity. This Application Note details the impact of artifacts on key applications, provides validated protocols for their removal, and offers a toolkit for researchers to implement these methods effectively.

Artifact Types and Their Specific Impacts on Downstream Applications

Artifacts distort the amplitude and spectral properties of neural signals, with consequences that vary significantly across applications. The table below catalogs major artifact types and their specific interference mechanisms.

Table 1: Artifact Types, Characteristics, and Downstream Impacts

| Artifact Type | Origin | Signal Characteristics | Impact on BCI Performance | Impact on Clinical Diagnosis | Impact on Research Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ocular (EOG) | Eye blinks and movements [1] | High-amplitude, low-frequency deflections (<4 Hz) [3] [1] | Masks event-related potentials; corrupts features for low-frequency-based BCIs [3] | Mimics delta/theta activity in frontal lobes; can be misread as abnormal slow waves [1] | Obscures genuine low-frequency cognitive processes (e.g., theta during memory) [3] |

| Muscle (EMG) | Facial, jaw, neck muscle contractions [1] | Broadband, high-frequency noise (20-300 Hz) [1] | Swamps sensorimotor rhythms (beta/gamma); severely degrades Motor Imagery classification [3] [19] | Obscures pathological high-frequency oscillations (HFOs) in epilepsy; mimics spike-wave complexes [3] [1] | Contaminates high-frequency brain activity associated with cognition (e.g., gamma oscillations) [3] |

| Cardiac (ECG) | Electrical activity of the heart [3] [1] | Rhythmic, periodic waveform at ~1-1.5 Hz [3] | Introduces periodic noise that can be mistaken for a control signal in slow-paced BCIs | Can be misinterpreted as epileptiform spikes, especially in sleep studies [1] | Can introduce spurious, periodic correlations in functional connectivity analyses |

| Motion & Electrode Pop | Head movement, poor electrode contact [1] | Abrupt, high-amplitude transients [1] | Causes large, non-stationary noise bursts that crash real-time decoders [1] | High-amplitude spikes can be misclassified as epileptic spikes or seizure onset [1] | Epoch rejection leads to significant data loss, reducing statistical power and introducing bias |

Quantitative Performance of Artifact Removal Methodologies

A range of techniques from classical to deep learning has been developed to mitigate artifacts. Their performance, measured by standardized quantitative metrics, is summarized below.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Artifact Removal Methodologies

| Methodology | Underlying Principle | Reported Performance Metrics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression | Linear subtraction of artifact template from reference channels (EOG/ECG) [3] | Not specified in search results; historically used for ocular artifacts [3] | Simple, computationally efficient [3] | Assumes linearity and stationarity; risks removing neural signals [3] |

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) | Blind source separation; identifies and removes artifactual components [3] [1] | Most commonly used algorithm; effective for Ocular/EMG artifacts [3] | Powerful for separating non-linear mixtures of sources [3] | Requires manual component inspection; computationally intensive; not real-time [3] |

| Temporal Signal Space Separation (tSSS) | Spatial filtering based on Maxwell's equations; separates external artifacts [20] | Validated for MEG during Deep Brain Stimulation; enabled >90% pattern classification accuracy comparable to DBS-off data [20] | Highly effective for magnetic and external artifacts in MEG [20] | Specific to MEG systems; requires specialized hardware and software [20] |

| GAN-LSTM (AnEEG) | Deep learning; generator produces clean EEG, discriminator evaluates fidelity [11] | Lower NMSE/RMSE; higher CC, SNR, and SAR vs. wavelet techniques [11] | Data-driven; can model complex, non-linear artifact types [11] | Requires large datasets for training; risk of over-fitting [11] |

| Transformer-Based Denoising | Self-attention mechanisms to capture global temporal dependencies [19] | ~5-10% accuracy gain in MI decoding; 11.15% RRMSE reduction, 9.81 dB SNR improvement (GCTNet) [19] [11] | Excellent at modeling long-range temporal contexts in EEG [19] | Computationally heavy; quadratically scaling complexity; sparse real-time validation [19] |

| PARRM | Template-based subtraction using known stimulation period [21] | Exceeds state-of-the-art filters in recovering complex signals without contamination [21] | High-fidelity signal recovery; suitable for closed-loop neuromodulation [21] | Applicable primarily in neurostimulation with a precise periodic artifact [21] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Artifact Removal in Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) with MEG

This protocol, adapted from [20], quantitatively validates that artifact removal salvages neural data without distorting the underlying brain signals.

- Aim: To quantitatively assess the efficacy of tSSS and other preprocessing in recovering neural signals from MEG data contaminated by DBS artifacts.

- Experimental Setup:

- Subjects: 8 patients with bilateral DBS implants for Parkinson's disease and 9 healthy controls [20].

- Task: Visual categorization task. This paradigm is selected because object recognition is unaffected by DBS, ensuring any differences between DBS-on and DBS-off conditions are due to artifacts, not neural changes [20].

- Conditions: MEG recordings are performed with the DBS stimulator ON and OFF.

- Data Acquisition:

- Record MEG data using a whole-head system (e.g., a 306-channel Elekta Neuromag system).

- Stimulation parameters (e.g., target: STN/GPi, frequency, pulse width, amplitude) must be documented for each patient [20].

- Preprocessing and Artifact Removal:

- Apply tSSS: Use Temporal Signal Space Separation to suppress external magnetic interferences, including those from the DBS implant and extension wires [20].

- Band-Pass Filter: Filter data to a relevant frequency band for the task (e.g., 1-40 Hz).

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to denoise and reduce data dimensionality [20].

- Validation via Machine Learning:

- Feature Extraction: Use the spatiotemporal pattern of evoked neural fields across MEG sensors on a single-trial basis [20].

- Train Classifiers: Train a multivariate pattern analysis (MVPA) classifier to distinguish between different visual object categories.

- Train and test on DBS-off data.

- Train and test on DBS-on data (after artifact removal).

- Cross-Condition Testing:

- Train a classifier on DBS-on data and test it on DBS-off data.

- Train a classifier on DBS-off data and test it on DBS-on data.

- Success Metrics:

- High Classification Accuracy in within-condition tests (DBS-on vs. DBS-off) demonstrates that neural data can be salvaged after artifact removal.

- Comparable Cross-Condition Classification Accuracy indicates that the spatiotemporal patterns of neural activity are similar between DBS-on and DBS-off, validating that the artifact removal process does not distort the underlying neural signal [20].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for validating artifact removal in DBS with MEG.

Protocol 2: A Deep Learning Pipeline for EEG Denoising and Motor Imagery Decoding

This protocol leverages a state-of-the-art transformer-based deep learning model to denoise EEG and decode motor imagery (MI) tasks, a core BCI application.

- Aim: To remove artifacts and classify MI tasks from raw, multi-channel EEG signals using a unified deep-learning framework.

- Data Preparation:

- Dataset: Use a public benchmark dataset like BCI Competition IV 2a (4-class MI) [19] [22].

- Partitioning: Employ a strict subject-agnostic, cross-validation scheme with fixed training and testing partitions to prevent data leakage and ensure generalizability [19].

- Preprocessing: Apply a band-pass filter (e.g., 4-38 Hz). Decimate the data to a uniform sampling rate (e.g., 250 Hz). Normalize the data per channel.

- Model Architecture: GCTNet (GAN-guided CNN-Transformer Network) [11]:

- Generator: The core denoising component. It takes raw, contaminated EEG as input and outputs clean EEG.

- Discriminator: A 1D convolutional network that judges whether the generator's output is indistinguishable from ground-truth clean EEG [11].

- Training Procedure:

- Loss Function: Use a composite loss including:

- Adversarial Loss: From the discriminator, ensuring generated signals are realistic.

- Temporal-Spatial-Frequency Loss: e.g., Mean-Squared Error on the time series and power spectral density to enforce similarity in both time and frequency domains [11].

- Optimization: Train the generator and discriminator in an adversarial manner until equilibrium is reached.

- Loss Function: Use a composite loss including:

- End-to-End Validation (Denoise → Decode):

- Pass held-out test data through the trained generator to obtain denoised signals.

- Train a separate, simpler classifier (e.g., a linear SVM or a shallow CNN) on the denoised training data to perform MI classification.

- Report the classification accuracy on the denoised test data. This "Denoise → Decode" benchmark is the most relevant metric for BCI applications [19].

Diagram 2: Deep learning pipeline for EEG denoising and MI decoding.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Datasets for Artifact Removal Research

| Tool/Dataset | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Artifact Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCI Competition IV 2a | Public Dataset | Benchmark for multi-class Motor Imagery classification [19] [22] | Provides real EEG with inherent artifacts for developing and benchmarking denoising algorithms [19] |

| EEG DenoiseNet | Public Dataset | Collection of clean EEG and artifact (EOG, EMG) segments [11] | Enables creation of semi-simulated datasets with known ground truth for controlled model training [11] |

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) | Algorithm | Blind source separation for signal decomposition [3] [1] | The most common method for identifying and removing physiological artifacts like ocular and muscle activity [3] |

| Temporal Signal Space Separation (tSSS) | Algorithm | Spatial filtering for MEG signal cleaning [20] | Critical for removing magnetic artifacts in specialized recordings, such as those during DBS [20] |

| Transformer Architecture | Deep Learning Model | Models long-range dependencies via self-attention [19] | State-of-the-art for capturing global temporal structures in EEG for both denoising and classification [19] [11] |

| Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) | Deep Learning Framework | Adversarial training for data generation/denoising [11] | Used to learn the mapping from artifact-laden to clean EEG signals in a data-driven manner [11] |

Signal-to-Noise Challenges in Microvolt-Range Neural Recordings

The pursuit of high-fidelity neural recordings is fundamentally linked to overcoming signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) challenges, particularly when capturing microvolt-range signals such as extracellular action potentials. As the field progresses toward high-density microelectrode arrays (HD-MEAs) with thousands of recording sites, these challenges intensify due to factors including increased crosstalk, reduced electrode size, and the inherent limitations of wireless data transmission in implantable systems [23] [24] [25]. Effective signal processing and artifact removal are not merely beneficial but essential for extracting meaningful neural information from noise-corrupted data, especially in applications ranging from basic neuroscience to pharmaceutical development and closed-loop therapeutic devices [24] [2].

This document outlines the primary sources of noise in neural recording systems, provides detailed protocols for assessing and mitigating these challenges, and presents a curated toolkit of reagents and solutions to support researchers in this field.

Neural signals span multiple orders of magnitude in both voltage and frequency. Understanding these characteristics is crucial for designing systems that optimize SNR.

Table 1: Characteristics of Neural Signals of Interest

| Signal Type | Amplitude Range | Frequency Bandwidth | Primary Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Action Potentials (Spikes) | 50 μV - 500 μV [24] | 300 Hz - 6 kHz [24] | Firing of individual neurons near the electrode. |

| Local Field Potentials (LFP) | 0.1 mV - 5 mV [23] | 3 Hz - 300 Hz [25] | Synchronous synaptic activity of a neuronal population. |

| Multi-Unit Activity (MUA) | Tens to hundreds of μV [25] | > 300 Hz [25] | Superposition of unresolved action potentials from multiple neurons. |

Table 2: Common Noise and Artifact Sources in Neural Recordings

| Noise/Artifact Type | Typical Magnitude | Spectral Characteristics | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Noise | Determined by electrode impedance and temperature [23] | Broadband | Electronic components and electrode interface. |

| Crosstalk | Varies with line proximity and frequency [25] | Increases with frequency [25] | Capacitive coupling between closely-spaced interconnects. |

| Motion Artifacts | Can exceed neural signals [2] | Typically low-frequency | Movement of electrode relative to tissue, especially with dry electrodes. |

| Stimulation Artifacts | Can saturate front-end amplifiers [26] | Dependent on stimulation parameters | Residual voltage from electrical stimulation pulses. |

| Background Neural Noise | Inherent to the biological signal [24] | Broadband | Superposition of distant neural activity. |

The following diagram illustrates the pathways through which these various noise sources contaminate the recorded neural signal.

Experimental Protocols for SNR Assessment and Artifact Management

Protocol: In Vivo Assessment of Signal Fidelity and Crosstalk

This protocol is designed to evaluate the impact of crosstalk and other noise sources on recordings from high-density arrays in an animal model, adapting methods from recent literature [25].

- Primary Objective: To quantify the degree of crosstalk contamination in neural signals recorded by a high-density microelectrode array and to distinguish it from genuine biological signal correlation.

- Materials:

- Conformable polyimide-based microelectrode array (e.g., 4x4 array with 50 µm electrode radius) [25].

- State-of-the-art neural signal acquisition system.

- Animal model (e.g., anesthetized rat).

- Whisker stimulation apparatus.

- Procedure:

- Surgical Implantation: Implant the microelectrode array epidurally over the somatosensory cortex (barrel field) of the anesthetized rat.

- Evoked Potential Recording: Apply controlled mechanical stimulation to the C2 whisker to evoke a repeatable neural response.

- Data Acquisition:

- Record somatosensory evoked potentials (SEPs) across all array channels.

- Simultaneously record multi-unit activity (MUA).

- Note the physical layout of the electrodes on the cortex and the routing layout of the interconnects on the array.

- Data Analysis:

- Waveform Analysis: Plot SEP and MUA spike waveforms for channels at increasing distances from the primary response focus (e.g., Electrode 1).

- Cross-Correlation: Compute spike cross-correlation between a reference channel and all other channels.

- Coherence Mapping: Calculate signal coherence between channels in both the LFP (3-300 Hz) and MUA (>300 Hz) bands. Generate coherence maps and compare them against the routing layout of the array.

- Expected Outcome & Interpretation:

- Positive Result for Crosstalk: A high signal coherence in the MUA band between channels that are adjacently routed but physically distant on the cortex is a strong indicator of crosstalk contamination [25].

- Biological Correlation: A coherence pattern that correlates solely with the inter-electrode distance on the cortical surface suggests a biological origin.

Protocol: Artifact Detection and Removal in Wearable EEG

This protocol summarizes a systematic pipeline for managing artifacts in wearable EEG systems, which often face similar SNR challenges to implantable systems but with different artifact profiles [2].

- Primary Objective: To detect, identify, and remove common artifacts from wearable EEG data without compromising the underlying neural signal.

- Materials:

- Wearable EEG system (≤16 channels, often with dry electrodes).

- Optional: Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs) for motion tracking.

- Procedure:

- Data Acquisition & Preprocessing: Record EEG in the ecological environment of interest. Apply basic bandpass filtering (e.g., 0.5-50 Hz).

- Artifact Detection:

- Method A (Wavelet Transform): Decompose the signal using wavelet transforms. Identify artifact components by applying thresholding to the wavelet coefficients.

- Method B (Deep Learning): Use a trained deep neural network (e.g., a convolutional neural network) to classify epochs of data as "clean" or "contaminated" by specific artifact types (e.g., ocular, muscular).

- Method C (Auxiliary Sensors): Use data from synchronized IMUs to identify periods of significant motion that correlate with artifacts in the EEG.

- Artifact Removal:

- For methods A and B, remove or reconstruct the identified artifact components from the signal.

- Apply techniques like the Artifact Subspace Reconstruction (ASR) algorithm to remove high-amplitude, transient artifacts.

- Validation:

- Accuracy: Assess the agreement between the processed signal and a known clean reference, if available.

- Selectivity: Evaluate the algorithm's ability to remove artifacts while preserving the physiological signal of interest [2].

- Troubleshooting:

- Over-cleaning: If neural signals appear unnaturally flat or key features are lost, adjust the detection thresholds to be less sensitive.

- Under-cleaning: If obvious artifacts remain, consider combining multiple detection methods (e.g., wavelet transform followed by ICA).

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Neural Recording Experiments

| Item Name | Specification/Example | Primary Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density Microelectrode Array (HD-MEA) | CMOS-based, >3000 electrodes/mm², integrated amplifiers [23] | High-spatiotemporal-resolution recording from electrogenic cells (neurons, cardiomyocytes). |

| Platinum-Iridium Electrode | PI20030.1A3 (MicroProbes for Life Science) [26] | Chronic implantation for electrical stimulation; provides stable interface and charge injection. |

| Calcium Indicator Virus | AAV1.Syn.GCaMP6s.WPRE.SV40 [26] | Genetically encodes a fluorescent calcium indicator in neurons for simultaneous optical imaging of activity. |

| Genetically Modified Model Organism | Ai14 x Gad2-IRES-Cre mice (Jackson Laboratory) [26] | Provides specific labeling of inhibitory neuron populations for targeted recording and manipulation. |

| Conformable Polyimide Array | 4x4 array, 50 µm electrode radius [25] | Epidural recording with minimal mechanical mismatch to soft brain tissue, improving signal stability. |

| Surgical Adhesive / Dental Cement | C&B Metabond (Parkell) [26] | Secures chronic cranial implants (headplates, connectors) to the skull. |

| Artifact Subspace Reconstruction (ASR) | Algorithm for MATLAB/Python [2] | Removes high-amplitude, transient artifacts from multi-channel EEG/MEA data in an automated fashion. |

| Spike Sorting Software Suite | Suite2p [26] | Processes raw imaging or electrophysiology data to extract spike times from individual neurons. |

Emerging Solutions and Computational Tools

Beyond physical reagents, computational tools are critical for modern artifact management:

- On-Implant Signal Processing: For brain-implantable devices, real-time spike detection and compression algorithms are essential for reducing data volume before wireless transmission, mitigating a major bottleneck in high-density recording [24].

- Crosstalk Back-Correction Algorithm: A novel computational method that uses a characterized electrical model of the recording chain to estimate and subtract crosstalk contamination from acquired neural signals, helping to recover ground-truth data [25].

- Independent Component Analysis (ICA): A classic blind source separation technique that remains widely used for isolating and removing artifacts like eye blinks and muscle activity from multi-channel recordings [2].

Methodological Innovations: From Traditional Filtering to Deep Learning Architectures

In neurotechnology, the accurate recording of neural signals is paramount for both scientific discovery and clinical applications. However, these microvolt-scale signals are highly susceptible to contamination by artifacts—unwanted signals from non-neural sources. Artifacts can originate from environmental electromagnetic interference, the subject's own physiological activities (such as heartbeats or muscle movement), or, in closed-loop systems, from stimulation artifacts (SA) generated by concurrent electrical stimulation [27] [1]. While software-based post-processing methods are valuable, hardware-based solutions provide the first and most critical line of defense. They prevent signal distortion at the acquisition stage, avoiding the irreversible saturation of amplifiers which can lead to permanent data loss. This document details hardware-centric strategies—encompassing physical shielding, advanced reference strategies, and specialized amplifier design—for effective artifact mitigation, providing a foundation for robust neural signal acquisition in research and clinical settings.

Electromagnetic Shielding

Principles and Materials

Electromagnetic interference (EMI) is a pervasive source of artifact, often manifesting as 50/60 Hz "line noise" from AC power sources [1]. Shielding operates on the principle of using conductive materials to create a barrier that attenuates the strength of an electromagnetic wave as it passes through. The Shielding Effectiveness (SE) is the metric used to quantify this performance, expressed in decibels (dB). Research into conductive coatings for glass, essential for windows in experimental chambers or vehicle-based labs, demonstrates the practical application of this principle. Studies on coatings composed of materials like In₂O₃ and SnO₂ have shown SE of 35–40 dB in the 10 kHz–1 GHz range, effectively shielding over 97% of EMP energy while maintaining high optical transmittance [28].

Quantitative Shielding Performance

Table 1: Shielding Effectiveness of Conductive Coating Materials

| Material/Coating Composition | Shielding Effectiveness (dB) | Frequency Range | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conductive Metal Oxide (e.g., In₂O₃, SnO₂) [28] | 35 - 40 dB | 10 kHz - 1 GHz | High transmittance (74-77%), sheet resistance 6.4-6.8 Ω/□ |

| Metal Meshes [28] | ~31.4 dB | C-band | Applied directly to glass substrates |

| Saline Layers (3mm) [28] | ~22 dB | C-band | Liquid-based shielding approach |

| ITO Coated Glass [28] | ~21 dB | 14.5 GHz | A commonly used transparent conductive material |

Diagram 1: Shielding blocks external interference.

Reference Strategies for Artifact Reduction

Common Average Referencing (CAR)

A common hardware-based strategy to mitigate common-mode artifacts involves manipulating the reference electrode. Common Average Referencing (CAR) is a technique where the signal from each recording electrode is referenced to the average of all signals from the electrode array [13]. This approach effectively suppresses artifacts that appear uniformly across the array because the common-mode artifact is subtracted out. While CAR is a powerful tool, its performance can be degraded by impedance mismatches between electrodes. In the context of intracortical recordings contaminated by functional electrical stimulation (FES) artifacts, CAR has been shown to reduce artifacts, though it may be outperformed by more sophisticated methods like Linear Regression Reference (LRR) [13].

Linear Regression Reference (LRR)

The Linear Regression Reference (LRR) method represents a more advanced evolution of reference strategies. Instead of a simple average, LRR creates a channel-specific reference signal for each electrode, composed of a weighted sum of signals from other channels in the array [13]. This technique is particularly effective because it can account for spatial variations in artifact propagation. In experimental comparisons, LRR demonstrated superior performance in recovering iBCI decoding performance during stimulation, achieving over 90% of normal decoding performance during surface FES and nearly full performance during intramuscular FES [13].

Table 2: Comparison of Reference Strategies for FES Artifact Reduction

| Method | Principle | Performance in FES-iBCI Context | Advantages & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Average Reference (CAR) [13] | References each channel to the average of all channels. | Reduces artifact magnitude; outperformed by LRR. | Simple to implement; less effective with impedance mismatch. |

| Linear Regression Reference (LRR) [13] | Uses a weighted, channel-specific sum of other channels as a reference. | >90% normal decoding performance with surface FES; nearly full performance with intramuscular FES. | Highly effective at recovering neural info; more computationally complex. |

| Blanking [13] | Excludes data during stimulation and artifact periods. | Decreases iBCI decoding performance due to data loss. | Simple; ignores neural information during blanking periods. |

Amplifier Design for Artifact Tolerance

Architectural Challenges and Solutions

The front-end amplifier, or Neural Recording Front-End (NRFE), is critical for initial signal conditioning. Traditional NRFE designs are highly susceptible to saturation from large stimulation artifacts (SA), which can be several orders of magnitude larger than neural signals. SA can be categorized into Common-Mode Artifacts (CMA) and Differential-Mode Artifacts (DMA), with CMA voltages potentially reaching 750 mV and DMA voltages up to 75 mV [27]. In contrast, neural action potentials are typically around 100 µV, making the threat of saturation clear.

Key Amplifier Design Specifications

Table 3: Neural Recording Front-End System Requirements

| Parameter | Typical Requirement or Value | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Input-Referred Noise (IRN) [27] | < 1 µVrms | Critical for resolving small neural signals. |

| Amplification Gain [27] | 40 - 80 dB | Balances signal resolution and dynamic range. |

| Bandwidth [27] | 0.5 Hz - 10 kHz | Covers local field potentials (LFP) and action potentials (AP). |

| Stimulation Artifact Tolerance [27] | CMA: ~750 mV, DMA: ~75 mV | Must not saturate the amplifier input stage. |

Modern integrated circuit designs employ several techniques to overcome these challenges. The Capacitively-Coupled Chopper Instrumentation Amplifier (CCIA) is a common topology that helps mitigate low-frequency noise and offset voltages [27]. To enhance artifact tolerance, designers incorporate features like current-reuse technology to lower input-referred noise, ripple reduction loops (RRL) to manage chopper-induced ripple, and impedance enhancement techniques to maintain signal integrity [27]. A fully differential stimulator (FDS) can be used on the stimulation side to help cancel out common-mode artifacts before they reach the recorder [27].

Diagram 2: NRFE interfaces with stimulation artifacts.

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Protocol: Evaluating Reference Strategies in FES-iBCI Systems

This protocol is adapted from research characterizing artifact reduction methods for intracortical Brain-Computer Interfaces (iBCIs) used with Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) [13].

- Objective: To characterize stimulation artifacts and compare the performance of software-based artifact reduction methods (Blanking, CAR, LRR) in an offline analysis setting.

- Materials and Setup:

- Subject: A participant with tetraplegia and two implanted 96-channel intracortical microelectrode arrays in the motor cortex.

- Stimulation: Thirty-six intramuscular stimulating electrodes and surface patch electrodes placed in the contralateral limb.

- Stimulator: A custom, battery-powered, isolated Universal External Control Unit (UECU).

- Neural Signal Acquisition: Intracortical signals are amplified, filtered (0.3 Hz – 7.5 kHz bandpass), and digitized at 30 kHz using a commercial neural signal processor.

- Synchronization: An output trigger from the stimulator is recorded by the neural processor to synchronize stimulation and recording.

- Procedure:

- Characterization: Record intracortical signals during both intramuscular and surface FES with varying parameters. Quantify baseline neural recording amplitude and artifact amplitude for both stimulation types.

- Data Collection: Perform an iBCI task (e.g., intended movement decoding) while applying FES. Record the neural data and the intended movement commands.

- Artifact Reduction (Offline): Apply the three artifact reduction methods (Blanking, CAR, LRR) to the same pre-recorded data blocks.

- Blanking: Exclude data segments during and immediately following each stimulation pulse.

- CAR: Re-reference each channel to the average signal of all channels.

- LRR: For each channel, create a reference from a weighted linear combination of other channels to model and subtract the artifact.

- Performance Metrics:

- Artifact Magnitude: Measure the peak-to-peak voltage of the artifact before and after applying each reduction method.

- Neural Feature Integrity: Assess how well the method preserves the original neural features used for decoding.