Synthetic Control Arms vs. Traditional Designs: The Future of Neuroscience Clinical Trials

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the paradigm shift from traditional randomized control trials (RCTs) to synthetic control arms (SCAs) in neuroscience.

Synthetic Control Arms vs. Traditional Designs: The Future of Neuroscience Clinical Trials

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the paradigm shift from traditional randomized control trials (RCTs) to synthetic control arms (SCAs) in neuroscience. It explores the foundational principles of SCAs, detailing their construction from real-world data and historical trial datasets. The content covers practical methodological applications across neurodegenerative, psychiatric, and rare neurological diseases, supported by case studies. It further addresses critical troubleshooting strategies for mitigating bias and optimizing data quality, and presents a rigorous validation framework comparing the efficacy, ethical, and economic outcomes of SCAs against traditional designs. The synthesis offers actionable insights for designing more efficient, patient-centric, and successful neuroscience trials.

Synthetic Control Arms 101: Redefining Clinical Trial Foundations in Neuroscience

In clinical trials, a control arm is the group of participants that does not receive the investigational therapy being studied, serving as a comparison benchmark to evaluate whether the new treatment is safe and effective [1] [2]. These control groups provide critical context, helping researchers determine if observed outcomes result from the experimental intervention or other factors such as natural disease progression or placebo effects [3]. The fundamental principle of controlled trials enables discrimination of patient outcomes caused by the investigational treatment from those arising from other confounding variables [3].

Traditional Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) remain the gold standard for clinical research, where participants are randomly assigned to either treatment or control arms, balancing both known and unknown confounding factors to ensure valid conclusions [4] [3]. However, evolving methodological approaches have introduced innovative alternatives like synthetic control arms (SCAs) that leverage external data sources to optimize trial efficiency and accelerate drug development, particularly valuable in rare diseases or complex conditions where recruitment challenges exist [4] [5].

Defining Traditional Control Arms

Traditional control arms constitute groups of participants within the same clinical trial who receive a reference treatment rather than the investigational therapy. These concurrent controls enable direct comparison under identical study conditions and timeframes [3]. Several standardized control arm methodologies have been established in clinical research, each with specific applications and implementation considerations.

Types of Traditional Control Arms

Placebo Concurrent Control: Placebos are inert substances or interventions designed to simulate medical therapy without specificity for the condition being treated [3]. They must share identical appearance, frequency, and formulation as the active drug to maintain blinding. Placebo controls help discriminate outcomes due to the investigational intervention from outcomes attributable to other factors and are used to demonstrate superiority or equivalence [3]. Ethical considerations restrict their use to situations where no effective treatment exists and no permanent harm (death or irreversible morbidity) would result from delaying available active treatment for the trial duration [3].

Active Treatment Concurrent Control: This design compares a new drug to an established standard therapy or evaluates a combination of new and standard therapies versus standard therapy alone [3]. The active comparator should preferably represent the current standard of care. This approach can demonstrate equivalence, non-inferiority, or superiority and is considered most ethical when approved treatments exist for the disease under study [3]. The Declaration of Helsinki mandates using standard treatments as controls when available [3].

No Treatment Concurrent Control: In this design, no intervention is administered to the control arm, requiring objective study endpoints to minimize observer bias [3]. The inability to blind participants and researchers to treatment assignment represents a significant limitation, as knowledge of who is receiving no treatment may influence outcome assessment and reporting [3].

Dose-Comparison Concurrent Control: Different doses or regimens of the same treatment serve as active and control arms in this design, establishing relationships between dosage and efficacy/safety profiles [3]. This approach may include active and placebo groups alongside different dose groups but can prove inefficient if the drug's therapeutic range is unknown before trial initiation [3].

Methodological Variations in Controlled Trials

Several specialized trial designs incorporate control arms in unique configurations to address specific research scenarios:

Add-on Design: All patients receive standard treatment, with the experimental therapy or placebo added to this background therapy [3]. This design measures incremental benefit beyond established treatments but may require large sample sizes if the additional improvement is modest [3].

Early Escape Design: Patients meeting predefined negative efficacy criteria are immediately withdrawn from the study to minimize exposure to ineffective treatments [3]. The time to withdrawal serves as the primary outcome variable, though this approach may sacrifice statistical power and primarily evaluates short-term efficacy [3].

Double-Dummy Technique: When comparator interventions differ in nature (e.g., oral versus injectable), both groups receive both a active and placebo formulation to maintain blinding [3]. For example, one group receives active drug A with placebo matching drug B, while the other receives active drug B with placebo matching drug A [3].

Table 1: Traditional Control Arm Types and Characteristics

| Control Arm Type | Key Features | Primary Applications | Ethical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo Control | Inert substance matching investigational treatment; maintains blinding | Superiority trials; conditions with no established treatment | Only justified when withholding treatment causes no permanent harm |

| Active Treatment Control | Established standard of care as comparator | Equivalence, non-inferiority, or superiority trials | Preferred when effective treatments exist; aligns with Declaration of Helsinki |

| No Treatment Control | No intervention administered; requires objective endpoints | Conditions where placebo effect is minimal | Challenging for blinding; may raise ethical concerns if effective treatment exists |

| Dose-Comparison Control | Different doses or regimens of same intervention | Dose-response relationship establishment | All participants receive active treatment, just at different levels |

Defining Synthetic Control Arms

Synthetic control arms (SCAs) represent an innovative methodology that utilizes external data sources to construct comparator groups, reducing or potentially eliminating the need for concurrent placebo or standard-of-care control arms within the same trial [4] [5]. Also known as external control arms, SCAs are generated using statistical methods applied to one or more external data sources, such as results from separate clinical trials or real-world data (RWD) [5]. The FDA defines external controls as any control group not part of the same randomized study as the group receiving the investigational therapy [5].

SCAs are particularly valuable when traditional RCTs with concurrent control arms present ethical concerns, practical difficulties, or feasibility challenges [5]. By leveraging existing data, SCAs can provide supportive evidence that contextualizes treatment effects and safety profiles in situations where this information would not otherwise be available, especially in single-arm trials [5]. Regulatory agencies including the FDA and EMA have increasingly accepted RWD-based SCAs, recognizing their value in modern clinical development, particularly for rare diseases and serious conditions with unmet medical needs [4] [6].

SCAs are constructed using patient-level data from patients not involved in the investigational clinical trial, with these external patients "matched" to the experimental participants using statistical methods to achieve balanced baseline characteristics [5]:

Historical Clinical Trial Data: Data from previous clinical trials provides highly standardized, quality-controlled information, though it may not fully represent the broader patient population due to recruitment biases [5].

Real-World Data (RWD): RWD originates from routine clinical practice through electronic health records, insurance claims, patient registries, and other healthcare sources [4] [5]. While offering higher volume and greater diversity, RWD often requires more processing to standardize formats and address missing data elements [5].

Combined Data Approaches: Mixed SCAs integrate both clinical trial and real-world data sources to maximize population matching and statistical power, as demonstrated in a 2025 DLBCL lymphoma study that combined data from the LNH09-7B trial and the REALYSA real-world observational cohort [7].

Methodological Framework for Synthetic Control Arms

Constructing valid SCAs requires rigorous statistical methodologies to minimize bias and ensure comparable groups [5] [6]:

Propensity Score Matching (PSM): This statistical technique estimates the probability of a patient receiving the investigational treatment based on observed baseline characteristics, creating balanced groups by matching trial participants with similar individuals from external data sources [5] [7].

Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (IPTW): Using propensity scores, IPTW assigns weights to patients in the external control group to create a synthetic population that resembles the baseline characteristics of the trial participants [7]. Stabilized IPTW (sIPTW) variants help minimize variance in the weighted population [7].

Covariate Balance Assessment: After applying matching or weighting methods, researchers assess balance using standardized mean differences (SMD) for each covariate included in the propensity score model, with SMD <0.1 generally indicating adequate balance [7].

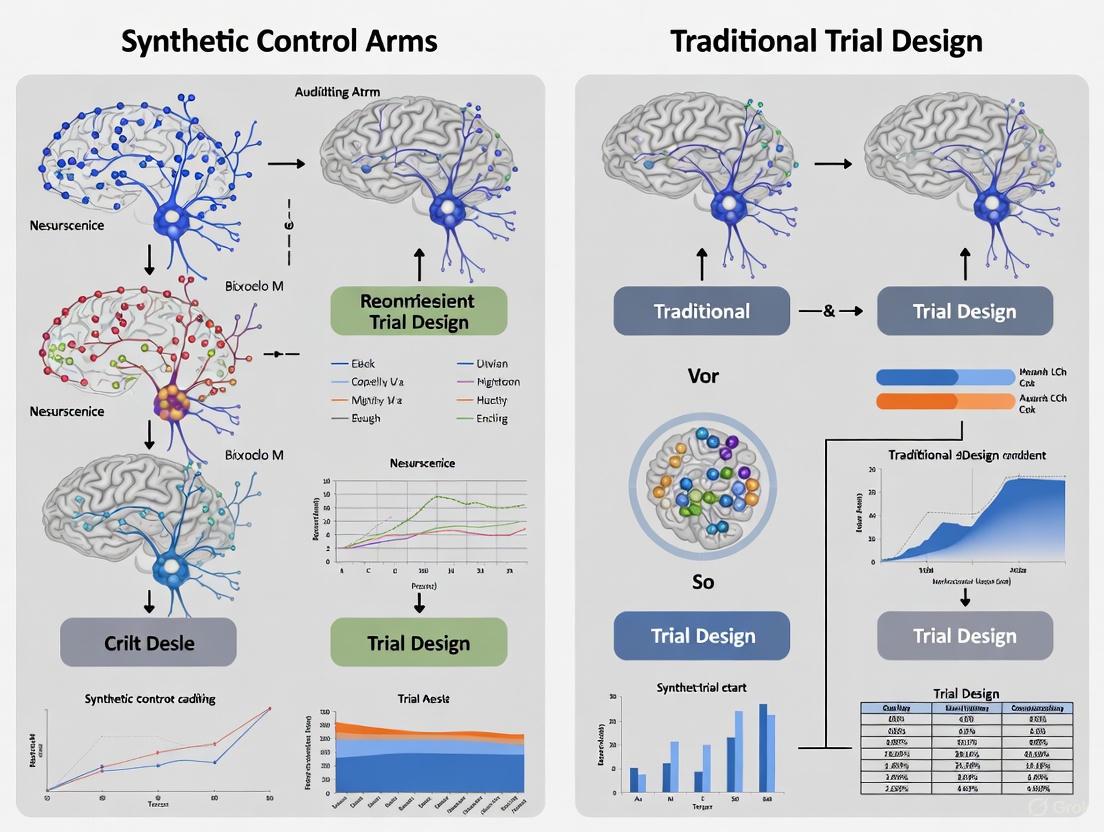

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for constructing and validating synthetic control arms:

Comparative Analysis: Synthetic vs. Traditional Control Arms

Advantages and Limitations

Table 2: Comprehensive Comparison of Synthetic vs. Traditional Control Arms

| Characteristic | Traditional Control Arms | Synthetic Control Arms |

|---|---|---|

| Ethical Considerations | Ethical concerns when assigning patients to placebo in life-threatening conditions with no clear standard of care [4] | Reduces ethical concerns by ensuring all trial participants receive active treatment [4] |

| Recruitment & Timelines | Recruiting control-arm patients can be difficult, leading to extended timelines, especially in rare diseases [4] [5] | Accelerates development by reducing need to recruit control patients; shortens trial durations [4] |

| Cost Implications | Higher costs associated with recruiting, randomizing, and following control-arm patients [5] | More cost-effective by avoiding expenses related to control patient recruitment and trial conduct [5] |

| Generalizability | May lack diversity and representativeness due to strict inclusion criteria [4] | Enhances generalizability through diverse real-world populations from multiple geographies [4] |

| Data Quality | Highly standardized data collection with consistent quality [5] | Variable quality depending on source; missing data and standardization challenges [5] |

| Bias Control | Randomization balances both known and unknown confounding factors [3] | Potential for selection bias if external data unrepresentative; only addresses measured confounders [5] |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Established regulatory pathway with clear expectations [3] | Growing acceptance but requires robust justification and validation [5] [6] |

| Methodological Flexibility | Limited flexibility once trial begins | Can incorporate multiple data sources and adapt to new information [5] |

Application Contexts and Appropriateness

The decision between synthetic and traditional control arms depends heavily on specific research contexts and constraints:

Rare Diseases and Precision Medicine: SCAs offer particular value in rare diseases where recruiting sufficient control patients presents significant challenges [4] [6]. Similarly, in precision medicine with genetically defined subpopulations, SCAs can provide historical comparators when concurrent randomization proves impractical [6].

Oncology Applications: SCAs have gained traction in oncology, where rapid treatment advances may render concurrent controls ethically problematic when superior alternatives emerge during trial conduct [5] [6]. Regulatory approvals have been granted for several oncology treatments based partially on synthetic control evidence [6].

Neuroscience Research Context: For neuroscience applications, particularly in neurodegenerative diseases with progressive courses and limited treatments, SCAs may address ethical concerns about placebo assignment while providing meaningful comparative data [4] [6]. However, careful attention to outcome measurement standardization is essential, as many neurological endpoints involve functional assessments potentially influenced by observer bias [3].

Experimental Evidence and Validation Studies

Case Study: DLBCL Lymphoma Research (2025)

A November 2025 study demonstrated the application of mixed synthetic control arms for elderly patients (≥80 years) with newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), a population typically underrepresented in clinical trials [7]. The research aimed to validate SCAs by reconstructing the control arm of the SENIOR randomized trial using external data sources.

Methodology:

- Data Sources: Combined real-world data from the REALYSA observational cohort (n=127) with historical clinical trial data from the LNH09-7B trial (n=149) to create a mixed SCA [7].

- Patient Matching: Used stabilized Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (sIPTW) based on propensity scores to balance baseline characteristics including sex, age, disease stage, performance status, and international prognostic index score [7].

- Endpoint: Overall survival (OS) censored at 24 months to address follow-up duration disparities [7].

- Missing Data Handling: Employed multiple imputation with 15 imputations per patient for covariates with substantial missing values in the real-world cohort [7].

Results: The synthetic control arm demonstrated comparable performance to the internal control arm of the SENIOR trial. After weighting, all covariates showed good balance with standardized mean differences <0.1. The hazard ratio for overall survival comparing the mixed SCA to the SENIOR experimental arm was 0.743 (95% CI: 0.494-1.118, p=0.1654), not statistically different from the original SENIOR results [7]. Sensitivity analyses using only real-world data and different missing data management approaches yielded consistent findings, supporting methodological robustness [7].

Regulatory Precedents and Historical Applications

Several regulatory decisions have established precedents for synthetic control arm acceptance:

Cerliponase Alfa Approval: The FDA approved cerliponase alfa for a specific form of Batten disease based on a synthetic control study comparing 22 patients from a single-arm trial against an external control group of 42 untreated patients [6].

Alectinib Label Expansion: Across 20 European countries, alectinib (a non-small cell lung cancer treatment) received expanded labeling based on a synthetic control study using external data from 67 patients [6].

Palbociclib Indication Expansion: The kinase inhibitor palbociclib gained an expanded indication for men with HR+, HER2-advanced or metastatic breast cancer based on external control data [6].

Implementation Considerations and Research Toolkit

Essential Methodological Components

Successfully implementing synthetic control arms requires careful attention to several methodological components:

Propensity Score Estimation: The foundation of valid SCA construction, involving logistic regression with carefully selected covariates that potentially influence both treatment assignment and outcomes [7]. Key covariates typically include demographic factors, disease characteristics, prognostic indicators, and prior treatment history [7].

Balance Diagnostics: After applying weighting or matching methods, researchers must quantitatively assess covariate balance between the investigational arm and the synthetic control using standardized mean differences, with values <0.1 generally indicating adequate balance [7].

Sensitivity Analyses: Comprehensive sensitivity analyses testing different statistical approaches, inclusion criteria, and missing data handling methods are essential to demonstrate result robustness [6] [7].

Regulatory and Protocol Considerations

Engaging regulatory agencies early when considering synthetic control arms is strongly recommended by the FDA, EMA, and MHRA [5]. Regulatory submissions should include:

- Justification for the proposed study design and reasons why traditional randomization is impractical or unethical [5]

- Detailed description of all data sources accessed with rationale for source selection and exclusion [5]

- Proposed statistical analysis plan with methodologies for addressing potential biases [5]

- Comprehensive data management plan and submission strategy for agency review [5]

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Control Arm Implementation

| Research Component | Purpose/Function | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality RWD Sources | Provides real-world patient data for SCA construction | Verify data quality, completeness, and relevance to target population; assess longitudinal follow-up [4] [5] |

| Propensity Score Methods | Statistical balancing of baseline characteristics | Select appropriate covariates; choose between matching, weighting, or stratification approaches [5] [7] |

| Multiple Imputation Techniques | Handles missing data in real-world sources | Determine appropriate imputation models; assess impact of missing data patterns [7] |

| Sensitivity Analysis Framework | Tests robustness of findings to methodological choices | Plan varied analytical approaches; assess impact of different assumptions [6] [7] |

| Regulatory Engagement Strategy | Facilitates agency feedback and acceptance | Prepare comprehensive briefing documents; schedule early meetings [5] |

Synthetic control arms represent a significant methodological advancement in clinical trial design, offering a viable alternative to traditional concurrent control arms in specific circumstances. While traditional RCTs with internal control arms remain the gold standard for establishing efficacy due to randomization's unique ability to balance both known and unknown confounders [3], SCAs provide a valuable approach when ethical, practical, or feasibility concerns limit traditional trial conduct [4] [5].

The growing regulatory acceptance of synthetic control methodologies reflects their potential to address challenging research scenarios, particularly in rare diseases, precision medicine applications, and situations where established standards of care make randomization ethically problematic [6] [7]. As real-world data sources continue to expand in quality and comprehensiveness, and statistical methodologies for leveraging these data become increasingly sophisticated, the appropriate application of synthetic control arms will likely continue to expand, offering promising opportunities to accelerate therapeutic development while maintaining scientific rigor.

The pursuit of novel therapeutics for complex neurological disorders is increasingly hampered by the methodological and ethical constraints of traditional randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Challenges such as patient recruitment, ethical concerns with placebo arms, and extensive heterogeneity in rare diseases are particularly acute in neuroscience. This review objectively compares the performance of an innovative alternative—synthetic control arms (SCAs)—against traditional trial designs. We synthesize current experimental data and regulatory guidance to demonstrate that SCAs, which use external data sources to construct virtual control groups, offer a viable path for accelerating drug development while maintaining scientific rigor in neurological research.

Neuroscience drug development faces a perfect storm of methodological challenges. Rare diseases with small patient populations, such as spinal cord injury (SCI), make recruiting for traditional RCTs difficult and sometimes impractical [8]. Furthermore, the ethical dilemma of assigning patients to placebo or substandard care in life-threatening or severely debilitating conditions creates significant barriers to trial participation and completion [5] [9]. The extensive heterogeneity in the clinical presentation and recovery trajectories of many neurological disorders further complicates the creation of well-matched control groups through randomization alone [8]. These limitations collectively underscore why traditional trials are reaching their practical and ethical limits in neuroscience, necessitating a paradigm shift toward more innovative designs.

Head-to-Head: Synthetic Control Arms vs. Traditional Randomized Trials

The following analysis compares the core characteristics, performance metrics, and applicability of synthetic control arms against traditional randomized trial designs.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Trial Designs

| Feature | Traditional Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) | Synthetic Control Arm (SCA) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Methodology | Prospective randomization of patients to investigational or concurrent control arm [10]. | External data (historical trials, RWD) analyzed to create a virtual control group matched to the investigational arm [10] [5]. |

| Control Group Source | Patients recruited and treated concurrently within the same study [11]. | Real-world data (RWD), historical clinical trial data, registry data [10] [5] [4]. |

| Typical Trial Duration | Longer, due to the need to recruit and follow a full control cohort [9]. | Shorter, attributed to faster recruitment as all trial patients receive the investigational treatment [9] [4]. |

| Ethical Concerns | Higher; patients may be assigned to a placebo or inferior standard of care, which can deter participation [5] [6]. | Lower; all enrolled patients receive the investigational therapy, removing the placebo dilemma [9] [4]. |

| Patient Recruitment | Challenging, especially for rare diseases; ~50% of patients may not receive the active drug [9]. | Easier; as all patients receive the active drug, participation is more attractive [5] [9]. |

| Primary Regulatory Challenge | Maintaining clinical equipoise and managing high costs/delays [6]. | Demonstrating control arm comparability and mitigating unknown confounding and bias [10] [5]. |

| Ideal Application | Common diseases with established standards of care and large available populations. | Rare diseases, severe conditions with unmet medical need, and orphan diseases [10] [5] [8]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics from Experimental Data

| Performance Metric | Traditional RCT (Typical Range) | Synthetic Control Arm (Evidence from Research) |

|---|---|---|

| Cohort Size Requirement | Requires full control cohort (often 1:1 ratio) [6]. | No or significantly fewer concurrent control patients needed; one Phase II case reduced trial size using SCA-informed sizing [10]. |

| Data Quality & Standardization | High, due to controlled, prospective, and protocol-driven data collection [5]. | Variable; high if built from historical clinical trial data, but can be lower with RWD due to missing data or formatting issues [10] [5]. |

| Risk of Bias | Low risk of selection and confounding bias due to randomization. | Risk of unknown confounding and selection bias is a key concern, mitigated via statistical methods [10] [5]. |

| Predictive Accuracy (Case Study) | N/A (Baseline) | In a spinal cord injury model, a convolutional neural network predicting recovery achieved a median RMSE of 0.55 for motor scores, showing no significant difference from randomized controls in simulation [8]. |

| Regulatory Precedence | Established gold standard for decades. | Growing acceptance; FDA and EMA have approved drugs using SCA data, particularly in oncology and rare diseases [10] [6]. |

Experimental Protocols: How Synthetic Control Arms Are Built and Validated

The construction of a regulatory-grade synthetic control arm is a multi-stage process that relies on robust data and rigorous methodology.

Core Methodology and Workflow

The process begins with the acquisition and curation of high-quality external data, followed by patient matching and statistical analysis to create a virtual cohort for comparison.

Detailed Protocol: Building a Machine Learning-Driven SCA for Spinal Cord Injury

A 2025 study on spinal cord injury (SCI) provides a template for a data-driven SCA protocol [8].

- Objective: To generate synthetic controls from personalized predictions of neurological recovery for use in single-arm trials for acute traumatic SCI.

- Data Sources:

- Primary Cohort: Data from 4,196 patients from the European Multicenter Study about Spinal Cord Injury (EMSCI).

- External Validation: Data from 587 patients from the historical Sygen trial.

- Input Data: International Standards for Neurological Classification of SCI (ISNCSCI) assessments, including segmental motor scores (MS), light touch scores (LTS), pinprick scores (PPS), AIS grade, and neurological level of injury (NLI). Patient age, sex, and time of assessment were also included.

- Model Benchmarking: Six prediction architectures were trained and compared:

- Regularized linear regression

- Random forest

- Extreme gradient-boosted trees (XGBoost)

- Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

- Sequence-to-sequence transformers

- Graph Neural Networks (GNN)

- Performance Evaluation: Model performance was quantified using the root mean squared error (RMSE) between true and predicted segmental motor scores below the initial neurological level of injury (RMSEbl.NLI).

- Validation: The best-performing model was applied in a simulation framework to model the randomization process and in a case study re-evaluating the completed NISCI trial as a single-arm trial post hoc.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for SCA Implementation

| Tool / Resource | Function & Application | Example / Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality RWD Sources | Provide the raw, real-world data from clinical practice used to build the control population. | IRIS Registry (Ophthalmology), AUA AQUA Registry (Urology); Verana Health curates data from over 90 million de-identified patients [4]. |

| Historical Clinical Trial Data | Provides a source of high-quality, standardized control data with less missing information. | Data from previous RCTs in the same disease area, such as the Sygen trial for spinal cord injury [10] [8]. |

| Propensity Score Matching | A statistical method to balance baseline characteristics between the investigational arm and the external control pool, reducing selection bias. | Creates an "apples-to-apples" comparison by matching patients on key prognostic factors [5]. |

| Machine Learning Models | Advanced algorithms to predict patient outcomes and create more precise, individualized counterfactuals. | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) for predicting sequential motor score recovery [8]. |

| Sensitivity Analysis Frameworks | Assess the robustness of the trial's conclusions by testing how they hold up under different assumptions about unmeasured confounding. | "Tipping point" analyses to determine how much unmeasured confounding would be needed to alter the study's primary finding [10]. |

Signaling Pathways in Trial Design: A Conceptual Workflow

The decision to employ a synthetic control arm is not arbitrary. It follows a logical pathway based on specific trial constraints and scientific requirements. The following diagram outlines the key decision points and methodological branches in modern clinical trial design.

Discussion and Future Directions

Synthetic control arms represent a significant evolution in clinical trial methodology, particularly suited to the pressing challenges of neuroscience research. While traditional RCTs remain the gold standard where feasible, the evidence indicates that SCAs are a scientifically valid and ethically superior alternative in contexts of high unmet medical need, rarity, and heterogeneity [10] [8]. Regulatory bodies like the FDA and EMA are increasingly receptive to this approach, especially when supported by high-quality data and robust statistical methods that address potential confounding [5] [6].

The future of SCAs lies not only in full replacement of control arms but also in hybrid designs, where a small randomized control arm is supplemented with synthetic control patients [10]. This hybrid model can bolster confidence in the results by allowing a direct comparison between randomized controls and external data patients. As machine learning models for outcome prediction become more sophisticated and real-world data sources continue to grow in quality and scope, the adoption of synthetic control arms is poised to accelerate, helping to bring effective neurological therapies to patients faster and more efficiently.

Synthetic control arms (SCAs) are transforming clinical trial design by using existing data to create virtual control groups, offering a powerful alternative to traditional randomized control arms. In neuroscience research, where patient recruitment is challenging and placebo groups can raise ethical concerns, SCAs provide a pathway to more efficient and robust comparative studies. The foundation of any effective SCA lies in the strategic use of two primary data sources: clinical trial repositories and real-world evidence (RWE).

This guide objectively compares the performance characteristics of these data sources and the platforms that provide them, supported by current experimental data and methodological insights.

Composing a Synthetic Control Arm: Source Data and Workflow

Constructing a SCA is a multi-stage process that relies on robust data and rigorous statistical methods to ensure the virtual control group is comparable to the interventional arm. The following diagram illustrates the key stages, from raw data sourcing to the final analysis-ready SCA.

Synthetic Control Arm Construction Workflow

The validity of a SCA hinges on the quality and appropriateness of its underlying data. The two principal sources—historical clinical trial data and real-world data (RWD)—offer complementary strengths and weaknesses.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Data Sources for Synthetic Control Arms

| Characteristic | Historical Clinical Trial Data | Real-World Data (RWD) |

|---|---|---|

| Data Standardization & Quality | Highly standardized; consistent collection; generally low missing data [5] | Variable formats and quality; requires extensive processing; potential for missing data [5] |

| Patient Population Representativeness | Can suffer from recruitment bias; may under-represent elderly, certain ethnic, or socio-economic groups [5] | Broader representation of real-world demographics and clinical practice [12] |

| Data Volume & Diversity | Lower volume; limited to specific trial protocols and populations [5] | Higher volume; captures diverse treatment patterns and comorbidities [13] |

| Primary Strengths | High internal validity due to controlled collection; familiar to regulators [5] | High external validity/generalizability; large sample sizes [13] [12] |

| Key Limitations | May not reflect current standard of care or broader patient populations [5] | Potential for unmeasured confounding; data curation is resource-intensive [5] [14] |

Market analysis indicates that RWD is the dominant data source for SCAs, holding a 53.5% market share in 2024 due to its volume and real-world applicability. However, the hybrid approach (RWD + Historical Trial Data) is expected to be the fastest-growing segment, as it can mitigate the limitations of using either source alone [14].

Key Platform Vendors and Technology Solutions

Specialized technology platforms are essential for curating, managing, and analyzing the complex data required for SCAs. The table below summarizes leading providers of real-world evidence and clinical data solutions.

Table 2: Key RWE and Clinical Data Platform Vendors

| Provider | Core Technology & Data Focus | Reported Applications & Differentiators |

|---|---|---|

| IQVIA | Large-scale, multi-source RWE analytics; one of the largest global longitudinal datasets [15] [16] | Supports regulatory and payer evidence needs; uses AI/ML for outcome prediction [16] [17] |

| Flatiron Health | Oncology-focused RWE platform; data from a network of oncology clinics and EHRs [15] [16] | High-quality, structured oncology data; demonstrated use in FDA-accepted SCAs (e.g., in NSCLC) [14] [16] |

| Aetion | Transparent and validated real-world analytics platform with a focus on regulatory-grade evidence [16] | Emphasizes reproducibility and audit trails; used by regulators like FDA and EMA for policy simulations [16] |

| Optum Life Sciences | Integrated healthcare data from claims, EHRs, and provider networks; strong payer perspective [15] [16] | Expertise in health economics and U.S. payer insights; robust data for cost and utilization analyses [16] |

| TriNetX | Global health research network providing access to EHR data from healthcare organizations [15] | Platform facilitates cohort discovery and feasibility analysis for clinical trials [15] |

The adoption of AI/ML analytics platforms is a key technological trend, as they are crucial for analyzing vast datasets to create well-matched synthetic control groups. This technology segment held the largest share (37.5%) of the SCA market in 2024 [14].

Experimental Protocol for SCA Validation: A Case Study in DLBCL

A 2025 study on diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in elderly patients provides a robust, real-world example of SCA construction and validation, offering a template for neuroscience applications [7].

Objective

To build and validate a mixed SCA from real-world and clinical trial data for patients aged ≥80 years with newly diagnosed DLBCL, and to assess if it could replicate the results of the SENIOR randomized controlled trial (RCT) [7].

- Real-World Data (RWD): Patient-level data from the REALYSA observational cohort [7].

- Historical Clinical Trial Data: Data from the LNH09-7B clinical trial [7].

- Validation Data: Data from the SENIOR RCT (used as the benchmark for comparison) [7].

Methodology

- Patient Matching: Patients from the SCA sources (REALYSA and LNH09-7B) were matched to the SENIOR trial arms based on key covariates, including sex, age, disease stage, performance status, and other prognostic factors [7].

- Statistical Harmonization - sIPTW: A stabilized Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (sIPTW) approach was used to balance the covariates between the SCA and the SENior trial arms. This technique weights patients based on their propensity scores to create a balanced synthetic cohort [7].

- Endpoint Analysis: The primary endpoint was Overall Survival (OS), censored at 24 months. The hazard ratio (HR) between the SCA and the SENIOR experimental arm was calculated [7].

Results and Validation

The SCA successfully replicated the results of the original RCT. The analysis showed no statistically significant difference in overall survival between the SCA and the SENIOR experimental arm, with a Hazard Ratio of 0.743 [0.494-1.118] (p = 0.1654). This confidence interval overlapped with that of the original SENIOR trial, confirming the SCA's ability to mimic the internal control arm [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for SCA Research

Building a regulatory-grade SCA requires a suite of methodological and technological "reagents."

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SCA Development

| Tool / Solution | Function in SCA Research |

|---|---|

| Propensity Score Matching (PSM) | A statistical method to reduce selection bias by matching each patient in the treatment arm with one or more patients from external data sources with similar observed characteristics [5] [12]. |

| Stabilized Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting (sIPTW) | A weighting technique used to balance covariate distributions between the treatment and synthetic control arm, improving the validity of comparative outcomes [7]. |

| AI/ML Analytics Platforms | Technology used to analyze large, complex datasets (RWD, clinical trials), identify patterns, and create precise synthetic control groups through advanced algorithms [14]. |

| Multiple Imputation Methods | A statistical approach for handling missing data, which is common in RWD. It creates multiple plausible values for missing data to avoid bias and retain statistical power [7]. |

| Real-World Evidence (RWE) Platforms | Integrated software solutions (e.g., from IQVIA, Flatiron, Aetion) that provide curated data, analytics tools, and workflows specifically designed for generating regulatory-grade evidence [15] [16]. |

For neuroscience researchers, the strategic selection and combination of data sources is paramount for constructing valid synthetic control arms. While historical clinical trial data offers precision and standardization, real-world evidence provides essential generalizability and volume.

The emerging best practice is a hybrid approach, leveraging the strengths of both to create robust, efficient, and ethically advantageous alternatives to traditional control groups. Supported by advanced AI/ML platforms and rigorous statistical methodologies like sIPTW, SCAs are poised to accelerate drug development in neuroscience and beyond, offering a viable path to generate robust evidence even for the most challenging patient populations.

The use of external controls in clinical drug development represents a paradigm shift in how evidence of therapeutic efficacy is established, particularly in fields like neuroscience research where traditional randomized controlled trials (RCTs) face significant ethical and practical challenges. External control arms (ECAs), including synthetic control arms (SCAs), utilize existing data from external sources—such as historical clinical trial data, real-world evidence (RWE), or natural history studies—to construct comparator groups when randomizing patients to a control intervention may be unethical or unfeasible. This approach has gained substantial traction in orphan drug development and oncology trials, and is increasingly being applied to complex neurological disorders such as Alzheimer's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and rare genetic neurological conditions.

The regulatory landscape governing these innovative trial designs is evolving rapidly, with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) demonstrating both convergence and divergence in their approaches. While both agencies recognize the potential of external controls to accelerate development of promising therapies, particularly for serious conditions with unmet medical needs, they maintain distinct regulatory philosophies, evidence standards, and implementation frameworks. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines provide a foundational framework for trial quality and design, but specific regulatory expectations for external controls continue to develop through case-by-case applications and emerging guidance documents. Understanding these nuanced differences is critical for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to implement synthetic control arms successfully within global development programs.

FDA and EMA: Structural Foundations and Regulatory Philosophies

Organizational Structure and Governance

The FDA and EMA differ fundamentally in their organizational structures, which directly influences their approach to evaluating innovative trial designs like external controls.

The FDA operates as a centralized federal authority within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, functioning as a unified regulatory body with direct decision-making power. The Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) and Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) employ full-time review teams who conduct comprehensive assessments of new drug applications [18] [19]. This centralized model enables relatively streamlined decision-making processes and consistent internal communication. The FDA maintains direct authority to approve, reject, or request additional information independently, with decisions applying immediately to the entire United States market upon approval [19].

In contrast, the EMA functions as a coordinating network rather than a centralized decision-making authority. Based in Amsterdam, the EMA coordinates the scientific evaluation of medicines through a complex network of national competent authorities across EU Member States [20]. For the centralized procedure, EMA's scientific committees—primarily the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP)—conduct evaluations by appointing Rapporteurs from national agencies who lead the assessment. The CHMP issues scientific opinions that are then forwarded to the European Commission, which holds the legal authority to grant actual marketing authorization [19]. This decentralized model incorporates broader European perspectives but requires more complex coordination across diverse healthcare systems and regulatory traditions.

Review Timelines and Procedural Frameworks

These structural differences manifest in varying review timelines and procedural approaches that impact development planning for sponsors utilizing external controls:

Table: Comparative Review Timelines and Procedures

| Aspect | FDA (United States) | EMA (European Union) |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Review Timeline | 10 months for New Drug Applications (NDAs) and Biologics License Applications (BLAs) [19] | 210-day active assessment (approximately 7 months), plus clock-stop periods and European Commission decision-making, typically totaling 12-15 months [18] [19] |

| Priority/Accelerated Review | 6 months for priority review of applications addressing serious conditions [18] [19] | 150 days for accelerated assessment of medicines of major public health interest [19] |

| Decision-Making Authority | FDA has direct approval authority [19] | EMA provides recommendations to European Commission, which grants marketing authorization [20] |

| Expedited Pathway Options | Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, Accelerated Approval, Priority Review [19] | Accelerated Assessment, Conditional Approval [19] |

ICH Guidelines: Quality Foundations for Innovative Trial Designs

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) provides critical foundational guidelines that establish quality standards for clinical development programs, including those utilizing external controls. While not specifically addressing external controls, several ICH guidelines create the framework within which these innovative designs must operate.

The ICH E8(R1) guideline on "General Considerations for Clinical Studies" emphasizes the importance of quality by design principles throughout clinical development [21]. This guideline encourages sponsors to identify factors critical to quality (CTQ) during trial planning, including those related to data collection, patient population definitions, and endpoint selection—all particularly relevant when constructing external control arms. The guideline promotes a risk-based approach to clinical trial design and conduct, recognizing that innovative designs may require tailored methodologies to ensure reliability and interpretability of results [21].

ICH E9 on "Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials" provides the statistical foundation for evaluating trial designs, including discussions on trial design choices, bias reduction, and handling of missing data [21]. The addendum ICH E9(R1) specifically addresses estimands and sensitivity analysis, providing a structured framework for aligning trial objectives with design elements and statistical analyses. This is especially pertinent to external control arms, where precise definition of the target estimand and thoughtful handling of potential confounding are critical to regulatory acceptance [21].

ICH E6(R2) on "Good Clinical Practice" establishes standards for clinical trial conduct, data integrity, and participant protection. For external controls utilizing real-world data, compliance with GCP principles—particularly regarding data accuracy, reliability, and robust audit trails—is essential for regulatory acceptability [21].

The FDA and EMA have demonstrated commitment to harmonizing their approaches to quality by design, as evidenced by their joint pilot program for parallel assessment of quality-by-design applications [22]. This collaboration has resulted in strong alignment on implementation of ICH Q8, Q9, and Q10 guidelines, fostering greater consistency in regulatory expectations for innovative approaches, including potentially those involving external controls [22].

Regulatory Approaches to External Controls: Comparative Analysis

Evidentiary Standards and Acceptance Criteria

The FDA and EMA maintain notably different approaches to evidentiary standards for drug approval, which directly impacts their acceptance of external controls in supporting efficacy determinations.

The FDA's statutory requirement for "substantial evidence of effectiveness" has traditionally been interpreted as requiring at least two adequate and well-controlled investigations [20]. However, the agency has demonstrated significant flexibility in implementing this standard, particularly for serious conditions with unmet needs. FDA guidance acknowledges that substantial evidence may be demonstrated with one adequate and well-controlled study along with confirmatory evidence [20]. This flexibility creates regulatory space for external controls to potentially serve as confirmatory evidence when derived from appropriate sources and subjected to rigorous methodological controls.

The EMA generally expects multiple sources of evidence supporting efficacy but may place greater emphasis on consistency across studies and generalizability to European populations [19]. The agency has issued specific reflection papers on topics relevant to external controls, including "Single-arm Trials as Pivotal Evidence for the Authorisation of Medicines in the EU" and "Guideline on Clinical Trials in Small Populations" [20]. These documents indicate openness to innovative designs while emphasizing methodological rigor and comprehensive bias assessment.

Table: Comparative Evidentiary Standards for External Controls

| Consideration | FDA Approach | EMA Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Basis for Efficacy Determination | Substantial evidence from adequate and well-controlled studies, potentially including one pivotal trial with confirmatory evidence [20] | Multiple sources of evidence supporting benefit-risk assessment, with emphasis on consistency and generalizability [19] |

| Explicit Guidance on External Controls | Limited specific guidance, but accepted within expedited programs and rare disease development [20] | Reflection paper on single-arm trials as pivotal evidence [20] |

| Key Methodological Concerns | Control for confounding, data quality, relevance of historical data, statistical approaches to address bias [20] | Comparability of external data to target population, reliability of data sources, appropriateness of statistical methods [20] |

| Natural History Study Utilization | Specific draft guidance on natural history studies for drug development [20] | Considered within framework for registry-based studies and real-world evidence [20] |

Expedited Pathways and Rare Disease Applications

Both agencies have developed specialized pathways that frequently accommodate external controls, particularly for rare diseases and serious conditions where traditional RCTs may be impractical or unethical.

The FDA's expedited programs include Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, Accelerated Approval, and Priority Review designations [19]. The Accelerated Approval pathway is particularly relevant for external controls, as it allows approval based on effects on surrogate or intermediate endpoints reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit, with required post-approval confirmatory studies [19]. This pathway has frequently accommodated innovative trial designs, including those utilizing external controls, especially in oncology and rare neurological disorders.

The EMA's expedited mechanisms include Conditional Approval and Accelerated Assessment [19]. The Conditional Approval pathway allows authorization based on less comprehensive data than normally required when addressing unmet medical needs, with obligations to complete ongoing or new studies post-approval [19]. The Accelerated Assessment reduces the standard review timeline from 210 to 150 days for medicines of major public health interest representing therapeutic innovation [19].

For orphan drug development, both agencies offer special designations with varying criteria. The FDA grants orphan designation for products treating conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 individuals in the United States, while EMA's threshold is not more than 5 in 10,000 individuals in the EU [20]. The EMA additionally requires that the product either addresses a condition with no available treatment or provides "significant benefit" over existing therapies [20]. These orphan drug pathways frequently accommodate external controls due to the challenges of conducting traditional RCTs in small patient populations.

Practical Application: Implementing External Controls in Neuroscience Research

Methodological Framework and Protocol Development

Successfully implementing external controls in neuroscience research requires meticulous attention to methodological details and comprehensive protocol development. The following workflow outlines key considerations when designing studies incorporating synthetic control arms:

Defining the Target Estimand: The ICH E9(R1) estimand framework provides a structured approach to precisely define the treatment effect of interest, accounting for intercurrent events (e.g., treatment discontinuation, use of rescue medication) and how they will be handled in the analysis [21]. For neuroscience applications, this includes careful consideration of disease progression patterns, standard care variations, and concomitant medications.

Data Source Identification and Assessment: Potential data sources for external controls in neuroscience include historical clinical trials, disease registries, natural history studies, and real-world data from electronic health records. Each source must be evaluated for completeness, accuracy, and relevance to the target population. Key considerations include diagnostic criteria consistency, endpoint measurement standardization, and follow-up duration compatibility [20].

Statistical Analysis Plan Development: The statistical analysis plan must pre-specify methods for addressing confounding and bias, which are inherent challenges when using external controls. Propensity score methods, matching techniques, and sensitivity analyses should be detailed to demonstrate robustness of results across various assumptions and methodological approaches [20].

Researchers implementing external controls in neuroscience should be familiar with key methodological resources and regulatory documents:

Table: Essential Resources for External Control Implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Application in Neuroscience Research |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Guidelines | FDA: "Rare Diseases: Natural History Studies for Drug Development"; EMA: "Guideline on Registry-Based Studies" [20] | Informs development of natural history studies for neurodegenerative diseases; guides utilization of patient registries for external controls |

| Statistical Methodologies | Propensity score matching, weighting, stratification; Bayesian dynamic borrowing; Sensitivity analyses [20] | Addresses confounding in ALS trials; incorporates historical data with precision in rare epilepsy studies |

| Data Standards | CDISC standards (required for FDA submissions) [21] | Ensures regulatory compliance in data structure for Alzheimer's disease trials |

| Quality Frameworks | ICH E8(R1) quality by design principles; ICH E6(R2) Good Clinical Practice [21] | Guides critical-to-quality factor identification in Parkinson's disease trials; ensures data integrity standards for real-world data sources |

Comparative Regulatory Analysis: FDA vs. EMA on External Controls

Strategic Considerations for Global Development Programs

Researchers pursuing global development programs incorporating external controls must navigate nuanced differences in FDA and EMA expectations:

Clinical Trial Design Preferences: The EMA generally expects comparison against relevant existing treatments when available, while the FDA has traditionally been more accepting of placebo-controlled trials even when active treatments exist [19]. This difference has implications for external control construction, as EMA may expect the external control to reflect current standard of care rather than historical placebo responses.

Pediatric Development Requirements: The EU's Pediatric Investigation Plan (PIP) requirement mandates earlier pediatric development planning compared to FDA's Pediatric Research Equity Act (PREA) [19]. This front-loaded requirement may create opportunities for incorporating external controls in pediatric neuroscience studies, where randomized trials are particularly challenging.

Risk Management Planning: The EMA requires a Risk Management Plan (RMP) for all new marketing authorization applications, typically more comprehensive than standard FDA risk management documentation [19]. For products approved based on studies with external controls, the RMP may require more extensive post-authorization safety studies and monitoring commitments.

Emerging Trends and Future Evolution

Both agencies are actively evolving their approaches to external controls, with several emerging trends particularly relevant to neuroscience research:

Real-World Evidence Integration: Both FDA and EMA have initiatives to advance the use of real-world evidence in regulatory decision-making [20]. The FDA's Real-World Evidence Program and EMA's Data Quality Framework represent significant steps toward establishing standardized approaches for utilizing real-world data in external controls [20].

Advanced Statistical Methodologies: Regulatory acceptance of more complex statistical approaches, including Bayesian methods that dynamically borrow information from external controls, is increasing particularly in orphan drug development [20]. These methodologies are especially promising for neuroscience applications with progressive diseases where historical natural history data may provide informative baselines.

International Harmonization Efforts: Despite differences in specific implementation, both agencies participate in international harmonization initiatives through the ICH and collaborative bilateral programs [22] [20]. The FDA-EMA parallel assessment pilot for quality-by-design applications demonstrates a commitment to regulatory convergence that may extend to innovative trial designs like external controls [22].

The regulatory evolution of FDA and EMA approaches to external controls reflects a broader transformation in drug development paradigms, particularly impactful in complex fields like neuroscience research. While both agencies maintain distinct regulatory philosophies and procedural frameworks, they share a common commitment to facilitating efficient development of innovative therapies for serious conditions with unmet medical needs. The ICH guidelines provide a foundational framework for quality and statistical rigor that supports appropriate implementation of external controls.

Successful navigation of this evolving landscape requires researchers to engage early with both agencies, develop robust methodological approaches addressing potential confounding and bias, and maintain flexibility to accommodate region-specific regulatory expectations. As regulatory science continues to advance, external controls—particularly synthetic control arms—are poised to play an increasingly important role in accelerating the development of transformative neuroscience therapies while maintaining the evidentiary standards necessary to protect patient welfare and ensure therapeutic benefit.

Building Better Trials: Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Neurology and Psychiatry

In the evolving landscape of neuroscience clinical research, the demand for robust and ethical study designs is paramount. The growing use of synthetic control arms (SCAs) presents a compelling alternative to traditional randomized controlled trials (RCTs), especially when assigning patients to a placebo or standard-of-care group is unethical, impractical, or leads to high dropout rates [5] [23]. The core validity of an SCA hinges on a single critical process: statistically matching patients receiving an investigational therapy to comparable patients from external data sources, such as historical clinical trials or real-world data (RWD) [24] [5]. This matching is primarily accomplished through propensity score (PS) methods, which distill multiple patient covariates into a single probability of having received the treatment. The accuracy of this "statistical engine room" directly determines the reliability of the entire trial. This guide provides an objective comparison of the methods used to estimate propensity scores, from traditional logistic regression to modern machine learning (ML) algorithms, equipping researchers with the data needed to build more valid and powerful synthetic control arms.

Synthetic vs. Traditional Controls: A Paradigm Shift

Synthetic control arms are a type of external control where a control group is constructed using statistical methods on patient-level data from one or more external sources, rather than being recruited concurrently [5]. The table below contrasts this innovative approach with traditional trial designs.

Table 1: Comparison of Synthetic Control Arms and Traditional Randomized Trials

| Aspect | Traditional Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) | Trial with a Synthetic Control Arm (SCA) |

|---|---|---|

| Control Group | Concurrently recruited patients randomized to control/placebo. | Constructed from external data (historical trials, RWD) [5]. |

| Key Advantage | Gold standard for minimizing bias through randomization. | Addresses ethical/recruitment challenges; can be faster and more cost-effective [5] [23]. |

| Key Limitation | Can be unethical, impractical, or slow to recruit; high dropout risk [23]. | Validity is entirely dependent on the quality and comparability of external data and the matching process [5]. |

| Ideal Use Case | Most scenarios where feasible and ethical. | Rare diseases, serious conditions with known outcomes, when concurrent randomization is infeasible [24] [5]. |

The Propensity Score Engine: Estimation Methods

The propensity score is the probability of a patient being in the treatment group given their observed baseline characteristics [25]. Accurate estimation is critical. Below, we compare the dominant methods.

Traditional Workhorse: Logistic Regression

For decades, logistic regression (LR) has been the default model for estimating propensity scores, used in up to 98% of medical articles applying PS methods [26]. It models the log-odds of treatment assignment as a linear combination of covariates. Its main strengths are interpretability and simplicity. However, its performance relies on the researcher correctly specifying the model, including all relevant interactions and non-linear terms—assumptions that are often violated in complex real-world data [25].

Modern Challengers: Machine Learning Algorithms

Machine learning models offer a powerful alternative by automatically detecting complex relationships and interactions without relying on pre-specified model forms [25] [27]. The following visualization outlines the core workflow for using these models in patient matching.

The most prominent ML algorithms for this task include:

- Random Forests (RF): An ensemble method that builds many decision trees on bootstrapped samples and averages the results. It is particularly strong at handling non-additive relationships and is less prone to overfitting than a single tree [25] [28].

- Boosted CART (e.g., Gradient Boosting): Another ensemble method that builds trees sequentially, with each new tree focusing on the errors of the previous ones. It is known for high prediction accuracy and has been shown to perform well in PS weighting [25] [27].

- Other Models: Bagged CART, Neural Networks, and Naive Bayes classifiers have also been explored, with varying performance depending on the data structure and application [25] [28].

Comparative Performance Data

The theoretical advantages of ML models are validated by extensive simulation studies and empirical comparisons. The following tables summarize key performance metrics from the literature.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of PS Models in Simulation Studies

| Estimation Method | Key Strengths | Key Weaknesses / Considerations | Performance in Complex Scenarios (Non-linearity & Non-additivity) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression (LR) | Interpretable, simple, widely accepted. | Prone to model misspecification bias [25]. | Subpar performance; high bias and poor CI coverage [25]. |

| Random Forests (RF) | Handles complex interactions well; robust. | Less interpretable ("black box"); requires tuning [28]. | Excellent performance, often top-ranked, especially for PS weighting [28]. |

| Boosted CART | High prediction accuracy; handles non-linearity. | Computationally intensive; sensitive to tuning [25]. | Substantially better bias reduction and consistent coverage vs. LR [25]. |

| Neural Networks | Very flexible function approximator. | "Black box"; requires large sample sizes and significant tuning. | Excellent performance, similar to Random Forests [28]. |

Table 3: Empirical Results from a Real-World Data Analysis (Lee et al., 2019 [28])

| Metric | Logistic Regression | Random Forests | Boosted CART | Neural Networks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Standardized Average Mean (ASAM)* | Baseline | Best Overall Balance | Good Balance | Excellent Balance |

| Bias of Causal Effect Estimator | Moderate | Lowest | Low | Low |

| Recommendation | Reliable for simple, main-effects models. | Top performer, especially for PS weighting. | Strong alternative, requires careful tuning. | Strong alternative, requires large data. |

Note: A lower ASAM indicates better covariate balance between matched groups. A threshold of <10% is commonly used [28].

A 2025 study on educational data further underscores that results can be mixed; while ML models like Random Forest and Gradient Boosted Machines often show superior prediction accuracy, they do not always guarantee perfect covariate balance and may even worsen balance for specific variables like race/ethnicity [26]. This highlights the non-negotiable need for rigorous post-matching diagnostics regardless of the method used.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure reproducibility, this section details the core methodologies used in the cited comparative studies.

- Data Generation: Simulate multiple datasets (e.g., n=500, 1000, 2000) with a binary exposure, continuous outcome, and ten covariates. Covariates are generated with pre-specified correlations.

- Scenario Design: Create several scenarios systematically varying the degree of non-linearity (e.g., quadratic terms) and non-additivity (interaction terms) in the true propensity score model.

- Propensity Score Estimation: Estimate propensity scores for each simulated dataset using all methods under comparison (e.g., LR, CART, RF, Boosted CART).

- Application of PS: Apply the propensity scores using a consistent method (e.g., weighting for the average treatment effect on the treated).

- Performance Evaluation: For each method and scenario, calculate performance metrics:

- Covariate Balance: Using metrics like Absolute Standardized Average Mean (ASAM).

- Bias: Percent absolute bias of the estimated treatment effect versus the known true effect.

- Coverage: Whether the 95% confidence interval for the effect contains the true value.

- Data Source: Use a well-defined observational dataset (e.g., birth records, educational longitudinal data).

- Define Treatment/Outcome: Clearly specify the treatment (e.g., labor induction, STEM major) and outcome (e.g., caesarean section, graduation outcome).

- Model Fitting: Fit the propensity score using different algorithms on the same set of pre-treatment covariates.

- Matching/Weighting: Use a consistent matching algorithm (e.g., 1:1 nearest-neighbor with caliper) or weighting scheme based on the estimated scores.

- Balance Assessment: Compute balance metrics (e.g., SMD, ASAM) for the matched/weighted sample.

- Effect Estimation & Comparison: Estimate the treatment effect and compare the results and the quality of balance achieved by the different PS estimation methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit for Patient Matching

Successfully implementing a patient matching strategy requires a suite of methodological and computational tools. The following table details the essential "research reagents" for this task.

Table 4: Essential Toolkit for Propensity Score-Based Patient Matching

| Tool / Solution | Function / Purpose | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | Provides the environment for data manipulation, model fitting, and analysis. | R (with MatchIt, twang, randomForest packages) [25] [27] or Python (with scikit-learn, causalinference libraries). |

| Propensity Score Models | The core algorithms that estimate the probability of treatment assignment. | Logistic Regression, Random Forests, Gradient Boosting Machines [25] [27] [28]. |

| Matching Algorithms | The procedures that use PS to create comparable treatment and control groups. | Nearest-neighbor (with/without caliper), Optimal matching, Full matching [27]. The choice impacts bias and sample size. |

| Balance Diagnostics | Metrics and plots to verify that matching successfully balanced covariates. | Absolute Standardized Mean Differences (ASAM/SMD) (target <0.1) [28], Visualizations (e.g., Love plots, distribution plots) [27]. |

| High-Quality Data | The foundational input for constructing a valid synthetic control arm. | Curated RWD, historical clinical trial data. Must be relevant, complete, and representative of the trial population [24] [5]. |

The final workflow, incorporating both model selection and critical validation checks, can be summarized as follows.

The construction of synthetic control arms represents a significant advancement in clinical trial methodology, particularly for neuroscience where patient heterogeneity and ethical concerns are prominent. The statistical engine powering these designs—propensity score-based patient matching—has itself evolved. While logistic regression remains a reliable and interpretable tool for simpler scenarios, empirical evidence consistently demonstrates that machine learning algorithms, particularly Random Forests and Boosted CART, provide superior performance in the presence of the complex, non-linear relationships often found in real-world patient data [25] [28]. For researchers aiming to build the most robust and valid synthetic controls, adopting a multi-model strategy, rigorously validating covariate balance, and transparently reporting methodology are no longer best practices—they are necessities for gaining the confidence of regulators and the scientific community.

The evaluation of novel therapies for Alzheimer's disease (AD) faces a critical challenge: the growing ethical and practical difficulty of enrolling participants into concurrent placebo control groups, especially as effective treatments become available. This reluctance can stall the development of potentially groundbreaking therapies. Synthetic control arms (SCAs) have emerged as an innovative statistical methodology that can potentially overcome this barrier. This case study examines the proof-of-concept implementation of SCAs in Alzheimer's research, using data from the I-CONECT trial, and provides a comparative analysis with traditional randomized controlled trial (RCT) designs [29] [5].

SCAs are constructed from external data sources—such as historical clinical trial data or real-world data (RWD)—using statistical methods to create a control group that is comparable to the intervention group in a current study. This approach is particularly relevant in neuroscience research, where patient recruitment is often a major bottleneck, and the use of placebos can raise significant ethical concerns [5] [6].

Proof-of-Concept: The I-CONECT Trial and NACC-UDS Dataset

Experimental Aims and Design

A 2025 proof-of-concept study directly tested the feasibility and reliability of synthetic control methods in Alzheimer's disease research. The researchers utilized the I-CONECT trial, which investigates the impact of conversational interaction on cognitive function, as a platform for their analysis. The primary aim was to determine if a high-quality control group could be synthesized from existing data to replace or augment a concurrent control arm without compromising the validity of the efficacy estimates [29].

The study employed two distinct statistical methods for creating the synthetic controls:

- Case Mapping: This method involves identifying individual historical patients from an external database who closely match each participant in the current intervention group.

- Case Modeling: This approach uses statistical models to create a composite control profile based on the characteristics of the intervention group as a whole [29].

Data Source and Patient Matching

The external data was sourced from the National Alzheimer's Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set (NACC-UDS), a large, standardized database compiling clinical and neuropathological data from numerous US Alzheimer's Disease Centers. This registry provided an ideal pool for identifying historical cases with similar demographic, biological, and social characteristics to the participants in the I-CONECT trial. The quality of the SCA hinges on the robustness of this data source and the sophistication of the algorithms used to match or model the patients [29].

Table 1: Key Components of the SCA Workflow in the I-CONECT Proof-of-Concept Study

| Component | Description | Role in SCA Creation |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention Group | Participants from the I-CONECT trial receiving the conversational interaction intervention. | Served as the target for matching; the group to which the synthetic control would be compared. |

| External Data Source (NACC-UDS) | A large, curated registry of patient data from numerous Alzheimer's Disease Centers. | Provided the raw historical data from which potential control patients were selected or modeled. |

| Similarity Algorithms | Statistical methods (e.g., for case mapping and modeling) used to assess and match patient characteristics. | Critical for ensuring the synthetic control group is comparable to the intervention group in key baseline covariates. |

| Primary Outcome | Cognitive function measures. | The endpoint used to compare the treatment effect between the intervention group and the synthetic control. |

Results and Validation

The study demonstrated that synthetic control methods are both feasible and reliable for Alzheimer's disease studies. The key finding was the close alignment of treatment effect estimates between the original randomized trial and the analyses using synthetic controls [29].

- In parallel-group designs, the treatment effect size (β) for the primary cognitive outcome was 1.67 in the original trial. The SCA analyses produced nearly identical estimates, ranging from 1.40 to 1.65 [29].

- For n-of-1 designs, which focus on individual patient responses, the two SCA methods showed a high level of agreement in identifying treatment responders, with a Kappa statistic between 0.75 and 0.82 [29].

This validation confirmed that a well-constructed SCA could replicate the results of a traditional RCT in this context, providing a viable alternative when a concurrent control arm is not feasible.

Comparative Analysis: SCAs vs. Traditional RCT Designs

The implementation of SCAs presents a paradigm shift in clinical trial design. The following table contrasts the two approaches across several critical dimensions.

Table 2: Comparison of Synthetic Control Arm vs. Traditional Randomized Controlled Trial Designs

| Feature | Traditional RCT (Placebo/Standard-of-Care) | Synthetic Control Arm (SCA) |

|---|---|---|

| Control Group Source | Concurrently recruited patients, randomized to control. | Historical data from previous trials, registries, or real-world sources [5] [23]. |

| Patient Recruitment | Can be slow and challenging; requires recruiting enough patients for all arms. | Faster for the intervention arm; no need to recruit for the control arm [5] [30]. |

| Ethical Concerns | Higher; patients may be reluctant to participate due to chance of placebo assignment. | Lower; all trial participants receive the investigational therapy [5] [6]. |

| Cost & Duration | Typically higher costs and longer duration due to larger scale and longer recruitment. | Potentially reduced costs and shorter timelines by eliminating control arm operations [5] [30]. |

| Risk of Bias | Gold standard; randomization minimizes confounding and selection bias. | Susceptible to selection bias and unmeasured confounding if matching is imperfect [5] [6]. |

| Generalizability | Can be limited by strict inclusion/exclusion criteria. | May better reflect real-world populations if using broad RWD sources [30]. |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Well-established and widely accepted. | Growing acceptance but requires robust justification and validation [5] [6]. |

| Ideal Use Case | Common diseases, where recruitment is feasible; high-stakes regulatory submissions. | Rare diseases, oncology, settings where recruitment is impractical or unethical [5] [30] [6]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodological Framework

Implementing a valid SCA requires a rigorous, pre-specified methodology. The following workflow outlines the key steps, drawing from the I-CONECT study and other successful implementations [29] [7].

Diagram 1: SCA Implementation Workflow.This chart outlines the sequential steps for creating and validating a synthetic control arm, from data sourcing to regulatory submission.

Data Source Selection and Justification

The first step is identifying high-quality, relevant external data. As showcased in the I-CONECT study, ideal sources are often large, prospectively collected datasets with detailed patient-level information [29]. Common sources include:

- Historical Clinical Trial Data: Highly standardized and quality-controlled, but may have narrow inclusion criteria [5].

- Disease Registries & Natural History Studies: e.g., NACC-UDS for Alzheimer's, CRC-SCA for spinocerebellar ataxia [29] [31]. These are crucial for understanding disease progression.

- Real-World Data (RWD): From electronic health records (EHRs) or claims databases. Higher volume but requires significant processing to standardize and handle missing data [5] [7].

Data Processing and Harmonization

Data from different sources must be harmonized to ensure comparability. This involves:

- Mapping Variables: Ensuring outcome definitions (e.g., cognitive scores), lab values, and demographic data are consistent between the trial and external data [6].

- Managing Missing Data: Using methods like multiple imputation to account for missing covariates, as was done in the DLBCL study where 15 imputations per patient were used [7].

- Temporal Alignment: Accounting for changes in standard of care over time to avoid comparing against outdated practices [5].

Patient Matching and Covariate Balancing

This is the statistical core of SCA creation. The goal is to create a synthetic control group with baseline characteristics that are balanced with the intervention group. The predominant method is Propensity Score Matching or related techniques [7] [6].

- Propensity Score (PS): The probability of a patient being in the intervention group, given their observed covariates. It is typically estimated using logistic regression [7].