Spiking Neural Networks: The Next Frontier in Brain-Inspired Computing for Biomedical Research

Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs), the third generation of neural networks, offer a paradigm shift from traditional artificial neural networks (ANNs) by mimicking the brain's efficient, event-driven communication.

Spiking Neural Networks: The Next Frontier in Brain-Inspired Computing for Biomedical Research

Abstract

Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs), the third generation of neural networks, offer a paradigm shift from traditional artificial neural networks (ANNs) by mimicking the brain's efficient, event-driven communication. This article provides a comprehensive overview of SNNs for researchers and drug development professionals, covering their foundational principles in biology, recent breakthroughs in training methodologies like surrogate gradients and exact gradient descent, and their inherent advantages in energy efficiency and temporal data processing. We delve into the challenges of network optimization and troubleshooting, present a comparative analysis of SNN performance against ANNs, and explore their emerging potential in biomedical applications, from processing neuromorphic sensor data to enhancing privacy in sensitive clinical datasets. The synthesis of current research and future directions aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to leverage SNNs for advanced, efficient, and robust computational models in healthcare and drug discovery.

Understanding Spiking Neural Networks: Biological Inspiration and Core Principles

Action potentials are the fundamental units of communication in the nervous system, representing rapid, all-or-nothing electrical signals that enable neurons to transmit information over long distances. These discrete events are initiated when the sum of excitatory and inhibitory inputs to a neuron causes its membrane potential to reach a critical threshold, typically around -50 mV [1] [2]. The exquisite biophysical mechanisms underlying action potential generation not only enable complex computations in biological neural networks but also serve as the primary inspiration for spiking neural networks (SNNs) in artificial intelligence research. As the third generation of neural networks, SNNs directly emulate the event-driven, sparse communication patterns of biological neurons, offering promising advantages in energy efficiency and temporal data processing for applications ranging from robotics to neuromorphic vision systems [3] [4] [5].

Understanding the precise mechanisms of action potential generation and propagation provides critical insights for developing more efficient and biologically plausible artificial neural systems. This technical guide examines the biophysical principles of neuronal communication, quantitative characterization of action potentials, experimental methodologies for their investigation, and the direct translation of these biological principles to computational models in brain-inspired computing research.

Biophysical Mechanisms of Action Potential Generation

Ion Channels and Membrane Potential Dynamics

The generation of an action potential is governed by the precise orchestration of voltage-gated ion channels embedded in the neuronal membrane. In the resting state, neurons maintain a steady membrane potential of approximately -70 mV through the action of leak channels and ATP-driven pumps, particularly the Na/K-ATPase, which creates concentration gradients of sodium (Na+) and potassium (K+) ions across the membrane [2]. The resulting equilibrium potential for Na+ is approximately +60 mV, while for K+ it is approximately -85 mV, establishing the electrochemical driving forces that shape action potential dynamics [2].

When depolarizing inputs exceed the threshold potential, voltage-gated sodium channels (Nav) undergo rapid conformational changes. These channels contain positively charged amino acids in their S4 alpha-helices that are repelled by membrane depolarization, triggering a conformation change that opens the channel pore [2]. This initiates a positive feedback loop where Na+ influx further depolarizes the membrane, activating additional sodium channels. After approximately 1 ms, these channels become inactivated through a mechanism involving the linker region between domains III and IV, which blocks the pore and prevents further ion movement [2].

Simultaneously, voltage-gated potassium channels (Kv) activate, though with slower kinetics. Their opening permits K+ efflux, which drives the membrane potential back toward the resting state and eventually causes a brief hyperpolarization below the resting potential before the membrane stabilizes again [2]. This entire sequence typically occurs within 1-2 milliseconds, creating the characteristic spike shape of an action potential.

Propagation and Saltatory Conduction

Action potentials propagate along the axon through local circuit currents. In unmyelinated axons, depolarization of one membrane segment passively spreads to adjacent regions, bringing them to threshold in a continuous wave. However, in myelinated axons, the lipid-rich myelin sheath insulates the axon, forcing the depolarizing current to travel rapidly through the cytoplasm to the next node of Ranvier, where voltage-gated sodium channels are highly concentrated [2]. This saltatory conduction increases propagation velocity by more than an order of magnitude compared to unmyelinated fibers of the same diameter [2].

Table 1: Key Ion Channel Properties in Action Potential Generation

| Ion Channel Type | Activation Threshold | Kinetics | Primary Function | Equilibrium Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage-gated Na+ (Nav) | ~-50 mV | Fast (≈1 ms) Rapid depolarization | +60 mV | |

| Voltage-gated K+ (Kv) | ~-50 mV | Slow Repolarization | -85 mV | |

| Leak K+ channels | N/A | Tonic Maintenance of resting potential | -85 mV |

Quantitative Characterization of Action Potentials

Electrophysiological Parameters

Action potentials exhibit characteristic quantitative features that can be precisely measured using electrophysiological techniques. The resting membrane potential typically ranges from -60 to -70 mV in central neurons, with threshold potentials generally lying between -50 and -55 mV [1] [2]. The peak amplitude of action potentials relative to the resting state generally reaches approximately +30 to +40 mV, resulting in an absolute peak potential around +20 to +30 mV [2]. The entire depolarization-repolarization cycle typically spans 1-2 milliseconds in fast-spiking neurons, though duration varies significantly across neuronal types [2].

Following the repolarization phase, most neurons experience a refractory period consisting of an absolute phase (approximately 1-2 ms) during which no subsequent action potential can be generated, followed by a relative refractory period where stronger stimulation is required to elicit another spike [2]. These properties limit the maximum firing rate of neurons to approximately 200-500 Hz for the most rapid spikers, though most cortical neurons operate at far lower frequencies.

Ion Concentration Dynamics and Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz Equation

The membrane potential at any moment can be mathematically described by the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation, which takes into account the relative permeability of the membrane to different ions and their concentration gradients [4]:

$$ vm = \frac{RT}{F} \ln \frac{PK[K^+]{out} + P{Na}[Na^+]{out} + P{Cl}[Cl^-]{in}}{PK[K^+]{in} + P{Na}[Na^+]{in} + P{Cl}[Cl^-]_{out}} $$

Where R is the universal gas constant, T is absolute temperature, F is the Faraday constant, [A]out and [A]in are extracellular and intracellular ion concentrations, and PA is the membrane permeability for ion A [4]. For a typical neuron at rest, the relative permeability ratios are PK:PNa:PCl = 1:0.04:0.45, while at the peak of the action potential, these ratios shift dramatically to approximately 1:12:0.45 due to the massive increase in sodium permeability [4].

Table 2: Quantitative Parameters of Neuronal Action Potentials

| Parameter | Typical Range | Determining Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Resting Membrane Potential | -60 to -70 mV | K+ leak channels, Na/K-ATPase activity |

| Threshold Potential | -50 to -55 mV | Density and properties of voltage-gated Na+ channels |

| Peak Amplitude | +20 to +30 mV (absolute) | Na+ equilibrium potential, channel density |

| Duration | 1-2 ms | Kinetics of Na+ channel inactivation and K+ channel activation |

| Refractory Period | 1-4 ms | Recovery kinetics of voltage-gated ion channels |

| Maximum Firing Frequency | 200-500 Hz | Duration of action potential plus refractory period |

Experimental Methodologies for Action Potential Investigation

Electrophysiological Recording Techniques

Intracellular recording methods, particularly whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiology, provide the most direct means of investigating action potential mechanisms. This technique involves forming a high-resistance seal between a glass micropipette and the neuronal membrane, allowing precise control of the intracellular environment and accurate measurement of membrane potential dynamics [2]. For investigation of ion channel properties, voltage-clamp configurations enable researchers to measure current flow through specific channel populations while controlling the membrane potential.

Extracellular recording techniques, including multi-electrode arrays, permit simultaneous monitoring of action potentials from multiple neurons, making them particularly valuable for studying network dynamics. These approaches detect the extracellular current flows associated with action potentials, though they provide less direct information about subthreshold membrane potential dynamics [6].

Pharmacological and Genetic Manipulations

Selective ion channel blockers serve as essential tools for dissecting the contributions of specific current components to action potential generation. Tetrodotoxin (TTX), a potent blocker of voltage-gated sodium channels, completely abolishes action potentials when applied at sufficient concentrations [2]. Similarly, tetraethylammonium (TEA) and 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) block various potassium channel subtypes, typically prolonging action potential duration by slowing repolarization.

Genetic approaches, including knockout models and channelopathies, provide complementary insights into action potential mechanisms. Naturally occurring mutations in ion channel genes can cause various neurological disorders, offering valuable opportunities to study structure-function relationships in human patients and animal models [2].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Action Potential Investigation

| Reagent/Technique | Primary Function | Experimental Application |

|---|---|---|

| Tetrodotoxin (TTX) | Blocks voltage-gated Na+ channels | Isolating Na+ current contribution to action potentials |

| Tetraethylammonium (TEA) | Blocks certain K+ channels | Studying repolarization mechanisms |

| 4-Aminopyridine (4-AP) | Blocks transient K+ channels | Investigating action potential duration modulation |

| Patch-clamp electrophysiology | Intracellular recording | Direct measurement of membrane potential dynamics |

| Multi-electrode arrays | Extracellular recording | Network-level analysis of spiking activity |

| Voltage-sensitive dyes | Optical monitoring | Large-scale mapping of action potential propagation |

From Biological Neurons to Spiking Neural Networks

Computational Models of Spiking Neurons

The transition from biological action potentials to computationally efficient neuron models involves various levels of abstraction. The most biologically detailed models, such as the Hodgkin-Huxley formalism, mathematically describe the ionic currents underlying action potential generation using systems of nonlinear differential equations [3]. While highly accurate, these models are computationally expensive for large-scale simulations.

For more efficient computation in large-scale SNNs, simplified models such as the Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) neuron offer a balance between biological plausibility and computational efficiency [3] [4]. The LIF model approximates the neuron as an electrical RC circuit that integrates incoming synaptic inputs until a threshold is reached, at which point a spike is generated and the membrane potential resets [3]. Even simpler models, such as the Integrate-and-Fire (IF) neuron, remove the leak component to further reduce computational complexity [3].

Information Encoding in Biological and Artificial Spiking Systems

Biological neurons employ multiple coding schemes to represent information in spike trains. Rate coding, one of the earliest discovered mechanisms, represents information through the firing rate of neurons, with higher stimulus intensities generally producing higher firing frequencies [3]. Temporal coding schemes, including latency coding and inter-spike interval coding, utilize the precise timing of spikes to convey information more efficiently [3]. Population coding distributes information across the activity patterns of multiple neurons, enhancing robustness and representational capacity [3].

These biological encoding strategies directly inform input representation methods in SNNs. For processing static data such as images with SNNs, rate coding commonly converts pixel intensities into proportional firing rates [3]. For event-based sensors such as dynamic vision sensors (DVS) or single-photon avalanche diode (SPAD) arrays, which naturally produce temporal data streams, SNNs can process these signals directly without artificial encoding, leveraging their inherent compatibility with temporal data [3].

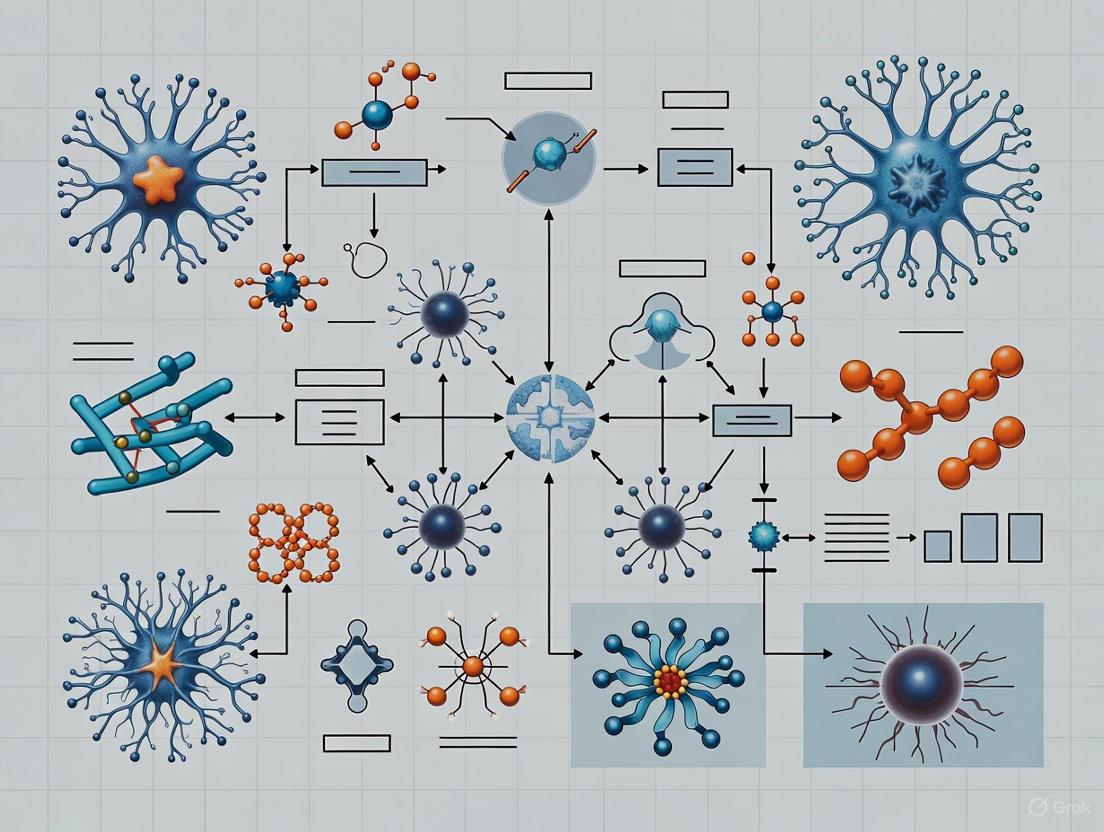

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for investigating action potential mechanisms and translating them to computational models:

Applications in Brain-Inspired Computing and Future Perspectives

The translation of action potential principles to SNNs has enabled significant advances in multiple application domains. In robotics and continuous control, fully spiking architectures can be trained end-to-end to control robotic arms with multiple degrees of freedom, achieving stable training and accurate torque control in simulated environments [5]. For neural interfaces, ultra-low-power SNNs enable unsupervised identification and classification of multivariate temporal patterns in continuous neural data streams, making them promising candidates for future embedding in neural implants [6].

In visual processing, SNNs demonstrate particular promise for energy-efficient, event-driven computation with dynamic vision sensors, though current progress remains constrained by reliance on small datasets and limited sensor-hardware integration [3]. As neuromorphic hardware platforms such as Loihi, TrueNorth, and SpiNNaker continue to mature, they offer increasingly efficient substrates for implementing SNNs that closely emulate the sparse, event-driven computation of biological neural networks [3] [4] [5].

The following diagram illustrates the structure and signal processing differences between biological neurons, artificial neurons, and spiking neurons:

Future research directions include developing more sophisticated neuron models that better capture the computational capabilities of biological neurons while maintaining computational efficiency, improving learning algorithms for SNNs to better leverage their temporal dynamics and sparse activity, and advancing neuromorphic hardware designs to support more complex and large-scale SNN implementations [3] [7]. As these areas progress, the continued study of biological action potential mechanisms will remain essential for inspiring more efficient and capable brain-inspired computing systems.

Action potentials represent one of nature's most elegant solutions to the challenge of rapid, long-distance communication in neural systems. Their all-or-nothing nature, refined by evolution across millions of years, provides a robust signaling mechanism that enables the complex computations underlying perception, cognition, and behavior. The precise biophysical mechanisms of action potential generation—from voltage-gated ion channel dynamics to saltatory conduction in myelinated axons—offer a rich source of inspiration for developing more efficient artificial neural systems.

As brain-inspired computing continues to evolve, the principles of action potential generation and propagation will remain fundamental to designing next-generation neural networks. By maintaining a close dialogue between neuroscience and artificial intelligence research, we can continue to extract valuable insights from biological neural systems while developing increasingly sophisticated computational models for solving complex real-world problems. The ongoing translation of biological principles to computational frameworks promises to yield not only more efficient artificial systems but also deeper understanding of the neural mechanisms that underlie biological intelligence.

The relentless pursuit of artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities has been increasingly shadowed by concerns over its growing computational and energy demands [8]. Conventional artificial neural networks (ANNs), while achieving remarkable accuracy, rely on continuous-valued activations and energy-intensive multiply-accumulate (MAC) operations, making their deployment in power-constrained edge environments challenging [8] [9]. This tension has catalyzed the exploration of more sustainable, brain-inspired paradigms, chief among them being Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs).

SNNs represent the third generation of neural networks, narrowing the gap between artificial computation and biological neural processing [8] [10]. They fundamentally depart from ANNs by encoding and transmitting information through discrete spike events over time. This event-driven, sparse computational model is not only more biologically plausible but also unlocks the potential for substantial gains in energy efficiency, particularly on specialized neuromorphic hardware [8] [11]. This technical guide explores the core principles of SNNs, framing the definition of spikes as discrete, event-driven signals within the broader context of brain-inspired computing research.

Fundamental Principles: From Continuous Activations to Discrete Spikes

The transition from ANN to SNN necessitates a foundational shift in how information is represented and processed.

The ANN Paradigm: Continuous and Synchronous

In ANNs, neurons typically output continuous-valued activation functions (e.g., ReLU). Information propagates synchronously through the network in a layer-by-layer fashion. The core operation is the multiply-accumulate (MAC), where input activations are multiplied by synaptic weights and summed. This process is dense and occurs for every neuron in every layer for every input, regardless of the input's value [12] [9].

The SNN Paradigm: Discrete and Event-Driven

In contrast, SNNs communicate via binary spikes (0 or 1). A neuron's state is not a single value but a time-varying membrane potential. Input spikes cause this potential to increase ("integrate"). When the potential crosses a specific threshold, the neuron "fires," emitting an output spike and then resetting its potential [8] [13]. This leads to two key characteristics:

- Discrete Signals: Information is encoded in the timing and/or rate of these all-or-nothing spike events.

- Event-Driven Computation: Computational updates (accumulates, or ACs) only occur when a spike arrives, leading to inherent sparsity [12]. This replaces the more costly MAC operation with a simpler accumulate (AC) operation, a primary source of potential energy savings [12] [10].

Table 1: Core Operational Differences Between ANN and SNN Neurons

| Feature | Artificial Neuron (ANN) | Spiking Neuron (SNN) |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Type | Continuous-valued activations | Discrete, binary spikes (0 or 1) |

| Communication | Synchronous, layer-wise | Asynchronous, event-driven |

| Core Operation | Multiply-Accumulate (MAC) | Accumulate (AC) |

| Internal State | Typically stateless | Dynamic membrane potential with memory |

| Information Encoding | Scalar value | Spike timing and/or firing rate |

Encoding and Neuron Models: The Machinery of Spikes

Transforming real-world data into spikes and modeling the neuronal dynamics are critical to SNN functionality.

Input Encoding Strategies

Converting static or dynamic data into spike trains is the first step in the SNN processing pipeline [8] [14]. Common encoding schemes include:

- Rate Coding: The firing rate of a spike train is proportional to the input value's intensity. While simple, it often requires many time steps to represent information accurately [8] [14].

- Temporal Coding: Information is embedded in the precise timing of spikes. Time-to-First-Spike (TTFS) is a popular scheme where a stronger stimulus leads to an earlier spike, enabling fast decision-making with fewer spikes [14].

- Population Coding: A group of neurons collectively represents a single input value, with each neuron tuned to different features, enabling robust and distributed representations [14].

- Direct Input/Latency Coding: For static data like images, pixel values can be directly applied to the membrane potential of the first layer for a single time step or converted into spike latencies [8].

Core Spiking Neuron Models

The Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) model is the most widely used in practical SNN applications due to its balance of biological plausibility and computational efficiency [8] [14]. Its dynamics are governed by the differential equation:

τm * (dVm/dt) = - (Vm - Vrest) + I(t)

Where τ<sub>m</sub> is the membrane time constant, V<sub>m</sub> is the membrane potential, V<sub>rest</sub> is the resting potential, and I(t) is the input current from incoming spikes. When V<sub>m</sub> exceeds the threshold V<sub>th</sub>, a spike is emitted, and V<sub>m</sub> is reset [8] [13].

Advanced models like the Izhikevich neuron and the recently proposed Multi-Synaptic Firing (MSF) neuron offer enhanced capabilities. The MSF neuron, inspired by biological multisynaptic connections, uses multiple thresholds to emit multiple spikes per time step, allowing it to simultaneously encode spatial intensity (via instantaneous rate) and temporal dynamics (via spike timing), generalizing both LIF and ReLU neurons [13].

Diagram 1: SNN Input Encoding and Neuron Models

Training Spiking Neural Networks: Overcoming the All-or-Nothing Barrier

The non-differentiable nature of spike generation, a binary event, poses a significant challenge for applying standard backpropagation. The field has developed several sophisticated strategies to overcome this.

Supervised Learning with Surrogate Gradients

This is the most common method for direct training of SNNs. During the forward pass, the hard threshold function is used to generate binary spikes. During the backward pass, this non-differentiable function is replaced with a smooth surrogate gradient (e.g., based on the arctangent or fast sigmoid functions), which allows gradients to flow backward through time (BPTT) [8] [15]. This approach enables end-to-end training of deep SNNs while preserving their temporal dynamics [8] [14].

ANN-to-SNN Conversion

This method involves first training an equivalent ANN with constraints (e.g., ReLU activation) to achieve high performance. The trained weights are then transferred to an SNN where the firing rates of the spiking neurons approximate the activation values of the original ANN [14] [15]. While this bypasses the direct training difficulty, it often requires a large number of time steps to accurately approximate the ANN's activations, which can negate the energy and latency benefits of SNNs [14] [15].

Unsupervised Learning with STDP

Spike-Timing-Dependent Plasticity (STDP) is a biologically plausible, unsupervised local learning rule. It adjusts synaptic strength based on the precise timing of pre- and post-synaptic spikes. If a pre-synaptic spike occurs before a post-synaptic spike, the synapse is strengthened (Long-Term Potentiation); otherwise, it is weakened (Long-Term Depression) [14]. While energy-efficient and elegant, purely STDP-trained networks often struggle to match the task accuracy of supervised methods on complex benchmarks [10].

Table 2: Comparison of Primary SNN Training Methodologies

| Training Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surrogate Gradient (BPTT) | Uses smooth gradient approximations during backward pass | High accuracy on complex tasks (vision, speech); preserves temporal dynamics | Computationally intensive training; surrogate mismatch |

| ANN-to-SNN Conversion | Maps pre-trained ANN weights and activations to SNN firing rates | Leverages mature ANN toolchains; high conversion accuracy for some models | High latency (many time steps); performance loss in low-latency regimes |

| STDP (Unsupervised) | Adjusts weights based on relative spike timing | High energy efficiency; biological plausibility; online learning | Typically lower accuracy on supervised tasks; scaling challenges |

Experimental Benchmarks and Performance Analysis

Empirical studies provide critical insight into the performance and efficiency trade-offs between ANNs and SNNs.

Standardized Benchmarking on Vision Tasks

A comprehensive tutorial-study benchmarked SNNs against architecturally matched ANNs on MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets [8]. The experiments utilized a shallow fully connected network on MNIST and a deeper VGG7 architecture on CIFAR-10, testing various neuron models (LIF, sigma-delta) and input encodings (direct, rate, temporal). Key findings are summarized below:

Table 3: Benchmark Results for SNNs vs. ANNs on Vision Tasks [8]

| Dataset / Model | ANN Baseline Accuracy | Best SNN Configuration | SNN Accuracy | Key Efficiency Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNIST (FCN) | 98.23% | Sigma-Delta Neuron + Rate/Sigma-Delta Encoding | 98.1% | Competitive accuracy, energy below ANN baseline |

| CIFAR-10 (VGG7) | 83.6% | Sigma-Delta Neuron + Direct Input (2 time steps) | 83.0% | Up to 3x efficiency vs. matched ANN; minimal performance gap |

The study identified that thresholds and the number of time steps are decisive factors. Intermediate thresholds and the minimal time window that still meets accuracy targets typically maximize efficiency per joule [8].

Fair Comparison in a Regression Task: Optical Flow

A critical study on event-based optical flow estimation addressed common comparison pitfalls by implementing both ANN and SNN (LIF neurons) versions of the same "FireNet" architecture on the same neuromorphic processor (SENECA) [12]. Both networks were sparsified to have less than 5% non-zero activations/spikes.

Key Experimental Protocol & Finding:

- Methodology: The ANN and SNN were designed with identical structures, parameter counts, and activation/spike densities. Performance, energy, and time were measured on the same hardware [12].

- Result: The SNN implementation was found to be more time- and energy-efficient. This was attributed to the different spatial distribution of spikes versus activations; the SNN produced fewer pixels with spikes, leading to fewer memory accesses—a dominant factor in energy consumption [12]. This highlights that beyond the AC-vs-MAC advantage, spike sparsity patterns can yield additional hardware benefits.

Application in Speech Enhancement and Brain-Machine Interfaces

SNNs are being actively applied to complex temporal tasks. A three-stage hybrid fine-tuning scheme (ANN pre-training → ANN-to-SNN conversion → hybrid fine-tuning) has been successfully applied to speech enhancement models like Wave-U-Net and Conv-TasNet, enabling fully spiking networks to operate directly on raw waveforms with performance close to their ANN counterparts [15].

In implantable brain-machine interfaces (iBMIs), where energy and memory footprints are extremely constrained, SNNs have shown a favorable Pareto front in the accuracy vs. memory/operations trade-off, making them strong candidates for decoder-integrated implants [16].

For researchers embarking on SNN development and benchmarking, the following tools and concepts form a essential toolkit.

Table 4: Essential Research Toolkit for SNN Development

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| LIF / Sigma-Delta Neuron | Neuron Model | Baseline model for balancing biological plausibility and computational efficiency [8]. |

| MSF Neuron | Neuron Model | Advanced model for simultaneous spatiotemporal encoding; generalizes LIF and ReLU [13]. |

| Surrogate Gradient (aTan) | Training Algorithm | Enables gradient-based learning (BPTT) by approximating the non-differentiable spike function [8]. |

| Rate / Temporal Coding | Encoding Scheme | Converts continuous data into spike trains; choice depends on latency and energy constraints [8] [14]. |

| SLAYER / SpikingJelly | Software Framework | Simulates and trains SNNs using surrogate gradient methods [8]. |

| Intel Lava / Loihi | Software/Hardware | Open-source framework for neuromorphic computing; Loihi is a research chip for executing SNNs [8] [11]. |

| Activation Sparsification | Optimization Technique | Method to increase sparsity in both ANNs and SNNs, crucial for fair efficiency comparisons [12]. |

The field of spiking neural networks is rapidly evolving, driven by the need for energy-efficient and temporally dynamic AI. Research is advancing on several fronts:

- Architecture Search (SNNaS): Automating the discovery of optimal SNN architectures tailored for spike-based computation, rather than adapting ANN designs, is a critical research direction that leverages hardware/software co-design [14].

- Advanced Neuron Models: Bio-inspired models like the Multi-Synaptic Firing (MSF) neuron demonstrate that enhancing the representational capacity of single neurons can significantly boost performance while preserving low-power characteristics [13].

- Hybrid Training Paradigms: Combining the stability of ANN pre-training with the precision of SNN fine-tuning, as seen in the three-stage hybrid pipeline, is a promising path for applying SNNs to challenging dense prediction tasks like speech enhancement [15].

In conclusion, the definition of spikes as discrete, event-driven signals marks a fundamental shift from the continuous paradigm of ANNs. This shift is not merely an algorithmic detail but the core enabler of a more efficient, biologically plausible, and temporally aware form of neural computation. While challenges in training and hardware integration remain, SNNs, underpinned by their sparse and event-driven nature, are poised to be a cornerstone of sustainable and brain-inspired computing, particularly for the next generation of edge AI and real-time processing systems.

Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) represent the third generation of neural networks, distinguished by their event-driven computation and close alignment with biological neural processes [17]. Within these networks, spiking neuron models define how input signals are integrated over time and how action potentials are generated, forming the computational basis for brain-inspired artificial intelligence systems. The selection of a neuron model involves a critical trade-off between biological plausibility, computational complexity, and implementation efficiency [18] [19]. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of two fundamental models: the Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) model, prized for its computational efficiency, and the Izhikevich model, renowned for its ability to reproduce rich biological firing patterns while maintaining reasonable computational demands. Understanding these models' mathematical foundations, dynamic behaviors, and implementation considerations is essential for advancing neuromorphic computing research and applications across various domains, including robotic control, medical diagnosis, and pattern recognition [18] [20].

Mathematical Foundations and Model Dynamics

Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) Model

The LIF model extends the basic integrate-and-fire mechanism by incorporating a leak current that mimics the natural decay of membrane potential in biological neurons. The model's dynamics are governed by a differential equation that describes the evolution of the membrane potential:

LIF Membrane Potential Dynamics: [ \taum \frac{dV}{dt} = -(V - EL) + RI(t) ] Where (\taum = R Cm) represents the membrane time constant, (V) is the membrane potential, (EL) is the leak reversal potential, (R) is the membrane resistance, (Cm) is the membrane capacitance, and (I(t)) is the input current [21]. When the membrane potential (V) crosses a specified threshold (V{th}), the neuron fires a spike, and (V) is reset to a resting potential (V{reset}) for a refractory period (\tau_{ref}).

The LIF model's implementation can be visualized through its core operational workflow, which encompasses both the subthreshold integration and spike generation mechanisms:

Izhikevich Neuron Model

The Izhikevich model strikes a balance between biological fidelity and computational efficiency by combining a quadratic nonlinearity with a recovery variable. The model is described by a two-dimensional system of differential equations:

Izhikevich Model Equations: [ \frac{dV}{dt} = 0.04V^2 + 5V + 140 - u + I ] [ \frac{du}{dt} = a(bV - u) ] With the spike reset condition: [ \text{if } V \geq 30 \text{ mV, then } V \leftarrow c, u \leftarrow u + d ] Where (V) represents the membrane potential, (u) is the recovery variable that accounts for potassium channel activation and sodium channel inactivation, and (I) is the synaptic input current [18] [17]. The parameters (a), (b), (c), and (d) are dimensionless constants that determine the model's dynamics and allow it to reproduce various neural firing patterns observed in biological systems, including tonic spiking, bursting, and chaotic behavior.

The dynamic behavior of the Izhikevich model can be visualized through its phase plane analysis, which reveals the interaction between membrane potential and recovery variable:

Comparative Analysis of Model Characteristics

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of LIF and Izhikevich Neuron Models

| Characteristic | Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) | Izhikevich Model |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Complexity | Low (1 differential equation) | Medium (2 differential equations) |

| Biological Plausibility | Limited | High (multiple firing patterns) |

| Hardware Implementation Cost | Low resource utilization | Moderate resource requirements |

| FPGA Operating Frequency | High (reference implementation) | ~3.18x faster than original [18] |

| Power Consumption | Low | Moderate (depends on implementation) |

| Number of Parameters | 4-6 (Cm, Rm, Vth, Vreset, etc.) | 4 (a, b, c, d) plus 2 state variables |

| Firing Patterns | Regular spiking only | 20+ patterns (tonic, bursting, chaotic) [17] |

| Memory Requirements | Low | Moderate (additional state variables) |

Table 2: Dynamic Behavior Capabilities of Neuron Models

| Dynamic Behavior | LIF Model | Izhikevich Model |

|---|---|---|

| Tonic Spiking | Limited implementation | Full support [17] |

| Bursting | Not supported | Full support [17] |

| Spike Frequency Adaptation | Requires extension | Native support |

| Chaotic Dynamics | Not supported | Identifiable through bifurcation analysis [18] |

| Initial Bursting | Not supported | Full support |

| Delayed Firing | Not supported | Full support [17] |

| Subthreshold Oscillations | Not supported | Possible with parameter tuning |

| Mixed Mode Oscillations | Not supported | Supported |

Hardware Implementation and Experimental Protocols

FPGA Implementation and CORDIC-Based Design

Recent advances in digital hardware design have enabled efficient implementation of both LIF and Izhikevich models on Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs). A modified Izhikevich model employing the Coordinate Rotation Digital Computer (CORDIC) algorithm demonstrates particular promise for neuromorphic applications. This approach uses adder and shifter operations to eliminate multipliers, resulting in a more efficient digital hardware implementation [18]. The CORDIC-based Izhikevich model can accurately replicate biological behaviors while achieving approximately 3.18 times speed increase compared to the original model when implemented on a Spartan6 board [18].

Experimental Protocol 1: CORDIC-Based Izhikevich Implementation

- Model Modification: Replace multiplication operations with CORDIC iterations using only adders and shifters

- Error Analysis: Quantify discrepancies between original and modified models using normalized root mean square error (NRMSE)

- Dynamic Evaluation: Assess preservation of firing patterns across parameter variations

- FPGA Synthesis: Implement design on target FPGA (e.g., Spartan6) using HDL implementation

- Performance Metrics: Evaluate operation frequency, power consumption, and resource utilization

- Validation: Compare with biological data or software simulations of original model

Memristor-CMOS Hybrid Implementations

Emerging nanoscale devices, particularly memristors, offer promising alternatives to traditional CMOS for implementing neuron models. Volatile memristors demonstrate characteristics suitable for emulating biological neurons, with resistance that spontaneously switches from low to high resistance states after removal of external voltage [19].

Table 3: Hardware Implementation Technologies for Neuron Models

| Technology | Advantages | Limitations | Neuron Model Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMOS | Mature technology, high reliability | Area-intensive for membrane capacitor | LIF, Izhikevich (simplified) |

| FPGA | Reconfigurability, rapid prototyping | Higher power consumption than ASIC | Both models (CORDIC-Izhikevich) [18] |

| Memristor-CMOS Hybrid | Compact size, energy efficiency | Variability in memristor characteristics | LIF (demonstrated) [19] |

| Analog CMOS | High speed, low power for specific configurations | Limited programmability, sensitivity to noise | LIF (optimized) |

Experimental Protocol 2: Memristor-Based LIF Neuron Characterization

- Circuit Design: Implement membrane capacitor using Metal-Insulator-Metal (MIM) capacitor or replace with memristive device

- Leakage Mechanism: Utilize partially switched-on NMOS transistor or memristor as leakage path

- Threshold Implementation: Design comparator circuit with precise threshold detection

- Reset Mechanism: Implement spike-triggered reset circuit or utilize volatile memristor self-reset

- Characterization: Apply input currents of varying amplitudes and durations

- Metrics Measurement: Record firing frequency, spike shape, power consumption, and area utilization

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 4: Essential Research Toolkit for Neuron Model Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| FPGA Development Boards | Digital hardware implementation | Spartan6 for CORDIC-Izhikevich [18] |

| NEST Simulator | Large-scale network simulation | IF model simulation with STDP [22] |

| CMOS PDK | Transistor-level implementation | 55nm CMOS for LIF neurons [19] |

| Memristor Models | Volatile/non-volatile device simulation | LIF neuron without reset circuit [19] |

| Verilog-A | Behavioral modeling of neuron circuits | Biphasic RC-based LIF implementation [19] |

| STDP Learning Rules | Synaptic plasticity implementation | Cortical plasticity experiments [23] |

Applications in Neural Networks and Neuromorphic Systems

Decision-Making Systems

The Basal Ganglia (BG) plays a central role in action selection and reinforcement learning in biological systems. SNNs modeling the cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loop have been successfully implemented using integrate-and-fire neurons for decision-making tasks in intelligent agents [20]. These networks incorporate dopamine regulation and spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) to modulate learning, demonstrating the application of biologically realistic neuron models in autonomous systems.

Experimental Protocol 3: Brain-Inspired Decision-Making SNN

- Network Architecture: Implement cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loop with 360+ IF units [23]

- Pathway Implementation: Model direct ("Go"), indirect ("No Go"), and hyperdirect pathways

- Dopamine Modulation: Incorporate D1 receptor facilitation of direct pathway and D2 receptor facilitation of indirect pathway

- STDP Learning: Apply spike-timing-dependent plasticity rules to cortico-striatal synapses

- Task Application: Deploy network to decision-making tasks (UAV navigation, obstacle avoidance)

- Performance Comparison: Evaluate against traditional reinforcement learning methods

Privacy-Enhanced SNNs with Temporal Dynamics

Izhikevich-inspired temporal dynamics can enhance privacy preservation in SNNs without modifying the underlying LIF neuron structure. Input-level transformations such as Poisson-Burst and Delayed-Burst dynamics introduce biological variability that improves resilience against membership inference attacks [17].

Experimental Protocol 4: Temporal Dynamics for Privacy Enhancement

- Spike Encoding: Implement Rate-based, Poisson-Burst, and Delayed-Burst input dynamics

- Network Training: Train identical LIF-based SNN architectures with different dynamics

- Membership Inference Attacks: Apply model inversion attacks to assess privacy vulnerability

- Privacy Metrics: Quantify Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) with lower values indicating better protection

- Performance Evaluation: Measure classification accuracy on benchmark datasets (MNIST, CIFAR-10)

- Efficiency Analysis: Compare GPU/CPU memory usage and power consumption across dynamics

The Leaky Integrate-and-Fire and Izhikevich neuron models represent complementary approaches in the neuromorphic computing landscape. The LIF model offers computational efficiency and straightforward implementation, making it suitable for large-scale network simulations where biological detail can be sacrificed for performance. In contrast, the Izhikevich model provides a balance between computational efficiency and biological expressivity, enabling the replication of diverse neural firing patterns essential for understanding brain function and developing biologically plausible intelligent systems. Recent advances in digital hardware design, particularly FPGA implementations using multiplier-free CORDIC algorithms and memristor-based analog implementations, continue to expand the application space for both models. The choice between these models ultimately depends on the specific application requirements, considering the trade-offs between biological fidelity, computational efficiency, and implementation constraints in brain-inspired computing systems.

Information encoding represents a foundational component of spiking neural networks (SNNs), determining how external stimuli are transformed into the temporal spike patterns that constitute the native language of neuromorphic computation. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three principal encoding strategies—temporal patterns, rank order, and population coding—situated within the broader context of brain-inspired computing research. We synthesize current theoretical frameworks, experimental protocols, and performance benchmarks, highlighting how these biologically-plausible encoding schemes enable the low-latency, energy-efficient processing that distinguishes SNNs from conventional artificial neural networks. The analysis demonstrates that selective implementation of these encoding methods can yield accuracy within 1-2% of ANN baselines while achieving up to threefold improvements in energy efficiency, positioning SNNs as transformative technologies for embedded AI, real-time robotics, and sustainable computing applications.

Spiking neural networks represent the third generation of neural network models, narrowing the gap between artificial intelligence and biological computation by processing information through discrete, event-driven spikes over time [8]. Unlike traditional artificial neural networks (ANNs) that employ continuous-valued activations, SNNs leverage temporal dynamics and sparse computation to achieve remarkable energy efficiency—particularly on neuromorphic hardware—while natively capturing time-dependent signal structure [8] [24]. The translation of sensory data into spike-based representations constitutes a critical first step in the SNN processing pipeline, directly influencing network performance, power consumption, and temporal resolution [25] [26].

In biological nervous systems, sensory organs employ diverse encoding strategies to transform physical stimuli into patterns of neural activity. Early research suggested rate coding as the predominant information transmission mechanism, but subsequent studies have demonstrated that all sensory systems embed perceptual information in precise spike timing to enable rapid processing [25]. The human visual system, for instance, completes object recognition within approximately 150 milliseconds—a timeline incompatible with rate-based integration but readily achievable through temporal coding mechanisms [25]. This biological evidence has motivated the development of artificial encoding schemes that optimize the trade-offs between representational capacity, latency, and computational efficiency.

This technical guide examines three advanced encoding paradigms—temporal patterns, rank order, and population coding—that transcend conventional rate-based approaches. We frame our analysis within the broader research agenda of brain-inspired computing, which seeks to develop systems that emulate the brain's exceptional efficiency, robustness, and adaptive capabilities. Through standardized benchmarking, quantitative comparison, and implementation guidelines, we provide researchers with a comprehensive framework for selecting and optimizing encoding strategies based on application-specific requirements for accuracy, latency, and energy constraints.

Theoretical Foundations and Classification

Taxonomy of Neural Encoding Schemes

Neural encoding strategies can be fundamentally categorized according to whether information is represented in firing rates or precise spike timing. Rate coding schemes embed information in the average number of spikes over a defined time window, while temporal coding utilizes the exact timing and order of spikes to convey information [25]. Population codes, often mischaracterized as a separate category, represent a dimensional extension where information is distributed across ensembles of neurons in either rate or temporal domains [25].

Table 1: Classification of Neural Encoding Schemes

| Encoding Category | Subtype | Information Carrier | Biological Plausibility | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate Coding | Count Rate | Average spike count over time | Moderate | Low to Moderate |

| Density Rate | Spike probability over trials | Low | Low | |

| Population Rate | Aggregate activity across neurons | High | Moderate | |

| Temporal Coding | Time-to-First-Spike (TTFS) | Latency to first spike | High | High |

| Inter-Spike-Interval (ISI) | Timing between spikes | High | High | |

| Rank Order | Sequence of firing across population | High | High | |

| Temporal Contrast | Change detection over time | High | High | |

| Population Coding | N/A | Distributed patterns across ensembles | High | Variable |

Temporal Pattern Coding

Temporal coding schemes exploit the precise timing of spikes to achieve high information density and rapid signal transmission. The most fundamental approach, Time-to-First-Spike (TTFS) coding, encodes stimulus intensity in the latency between stimulus onset and the first spike emitted by a neuron [25] [24]. In this scheme, stronger stimuli trigger earlier spikes, creating an inverse relationship between input magnitude and firing delay that enables single-spike information transmission with minimal latency [24]. Biological evidence for TTFS coding has been identified across sensory modalities, including visual, auditory, and tactile systems [25].

Inter-Spike-Interval (ISI) coding extends this principle by representing information in the precise temporal gaps between consecutive spikes within a train [25]. This approach enables continuous value representation through temporal patterns rather than single events, increasing representational capacity at the cost of additional integration time. Temporal contrast coding represents a specialized variant that responds primarily to signal changes over time, effectively suppressing static background information to enhance resource allocation toward dynamic stimulus features [25].

Rank Order Coding

Rank order coding represents a population-level temporal scheme where information is embedded in the relative firing sequence across a group of neurons [27]. Rather than absolute spike times, the order in which different neurons fire conveys the stimulus properties, creating a sparse but highly efficient representational format. This approach aligns with neurobiological evidence showing that object categories can be encoded in spike sequences contained within short (~100ms) population bursts whose timing remains independent of external stimulus timing [27].

The computational advantages of rank order coding include rapid information extraction—since classification can occur after the first wave of spikes—and inherent noise resistance due to its relative rather than absolute timing dependencies. Experimental implementations have demonstrated that spoken words transformed into spatio-temporal spike patterns through cochlear models can be effectively learned and recognized using rank-order-based networks without supervision [27].

Population Coding

Population coding distributes information across ensembles of neurons, leveraging the collective activity patterns of neural groups to represent stimulus features with enhanced robustness and discrimination capacity [25]. In biological systems, this approach enables graceful degradation—where the loss of individual neurons minimally impacts overall function—and supports multidimensional representation through specialized tuning curves across population members [25].

Artificial implementations of population coding typically employ groups of neurons with overlapping but distinct response properties, creating a distributed representation where stimulus characteristics can be decoded from the aggregate activity pattern. This approach is particularly valuable for representing continuous variables and complex feature spaces, as the combined activity of multiple neurons provides a higher-dimensional representational basis than individual units can achieve independently [25] [24].

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Benchmarking Methodology

Standardized evaluation protocols enable direct comparison of encoding schemes across consistent architectural and task constraints. Following established experimental frameworks [8], benchmarks should employ: (1) identical network architectures across encoding conditions; (2) standardized datasets with both static (e.g., MNIST, CIFAR-10) and temporal (e.g., speech, tactile) characteristics; (3) multiple neuron models including leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF) and adaptive variants; and (4) consistent training methodologies, preferably surrogate gradient learning for supervised contexts. Performance metrics should encompass not only final accuracy but also temporal evolution of accuracy, spike efficiency per inference, energy consumption proxies, and latency to first correct classification.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarks Across Encoding Schemes on Standard Datasets

| Encoding Scheme | MNIST Accuracy (%) | CIFAR-10 Accuracy (%) | Time Steps to Decision | Relative Energy Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate Coding | 97.8 | 81.5 | 50-100 | 1.0x (baseline) |

| TTFS | 97.2 | 79.8 | 5-20 | 3.2x |

| Rank Order | 96.5 | 78.3 | 10-25 | 2.8x |

| Population Rate | 98.1 | 82.1 | 20-50 | 1.5x |

| Sigma-Delta | 98.1 | 83.0 | 2-10 | 2.5x |

Interpretation of Comparative Results

Experimental data reveals consistent trade-offs between encoding approaches. Rate coding implementations generally achieve competitive accuracy—reaching 98.1% on MNIST and 83.0% on CIFAR-10 with sigma-delta neurons [8]—but require extended temporal windows for integration, resulting in higher latency and energy consumption. Temporal coding schemes like TTFS demonstrate substantially faster decision-making (as few as 2-10 time steps) and superior energy efficiency (up to 3.2× improvements over rate coding) but may exhibit slight accuracy reductions on complex visual tasks [8] [24].

Sigma-delta encoding emerges as a particularly balanced approach, achieving ANN-equivalent accuracy (83.0% on CIFAR-10 vs. 83.6% for ANN baseline) while maintaining significant energy advantages through minimal time step requirements [8]. The number of time steps and firing thresholds represent critical tuning parameters across all schemes, with intermediate thresholds and the minimal time window satisfying accuracy targets typically maximizing efficiency per joule [8].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol 1: Temporal Encoding for Static Image Classification

Objective: Implement and evaluate time-to-first-spike encoding for MNIST digit classification.

Materials: MNIST dataset; snnTorch or SpikingJelly framework; shallow fully-connected network (784-800-10) with LIF neurons.

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize pixel values to [0,1] range using torchvision.transforms.

- TTFS Encoding: Convert pixel intensities to spike times using inverse relationship:

spike_time = T_max * (1 - pixel_value)where T_max represents maximum simulation time. - Network Configuration: Initialize network with LIF neurons (τmem=10ms, Vth=1.0).

- Training: Employ surrogate gradient descent (arctan surrogate function) with BPTT, learning rate=1e-3, batch_size=128.

- Evaluation: Measure accuracy across time steps, latency to correct classification, and total synaptic operations.

Expected Outcomes: Classification accuracy >97% within 20 time steps, with first decisions emerging within 5-10 steps. Energy consumption should approximate 35% of equivalent rate-coded implementation [8] [28].

Protocol 2: Rank Order Coding for Audio Pattern Recognition

Objective: Implement rank order coding for spoken digit recognition from the Free Spoken Digit dataset.

Materials: FSDD dataset; cochlear model filter bank; spiking convolutional network.

Procedure:

- Cochlear Processing: Decompose audio signals into frequency channels using 32-band Gammatone filter bank.

- Feature Extraction: Generate sonogram representation through time-binning of channel energies.

- Rank Order Encoding: Convert feature map to spike sequence where higher activation values fire earlier.

- Network Architecture: Implement 2-layer convolutional SNN with stdp learning.

- Evaluation: Measure accuracy, robustness to noisy conditions, and energy per classification.

Expected Outcomes: Accuracy >90% with significant noise robustness; 3× faster classification compared to rate-based approaches [27] [26].

Protocol 3: Population Coding for Tactile Information Processing

Objective: Implement population coding for dynamic tactile stimulus classification.

Materials: Tactile sensor data; heterogeneous neuron population with varied tuning curves; Intel Loihi or SpiNNaker platform.

Procedure:

- Tuning Curve Design: Create population of 50 LIF neurons with sigmoidal tuning curves spanning stimulus range.

- Stimulus Encoding: Map sensor values to population activity patterns through divergent connections.

- Decoding: Implement Bayesian optimal decoding or population vector readout.

- Validation: Test on slip detection and texture discrimination tasks.

- Metrics: Measure classification fidelity, adaptation speed, and power consumption.

Expected Outcomes: Sub-millisecond latency, sub-milliwatt power consumption, and graceful performance degradation under neuron failure conditions [24].

Visualization Framework

Computational Graph for Encoding Schemes

Figure 1: Computational taxonomy of neural encoding schemes, illustrating the transformation of raw sensory data into spike-based representations through distinct algorithmic pathways.

Experimental Workflow for Encoding Evaluation

Figure 2: Standardized experimental workflow for systematic evaluation of encoding schemes, encompassing data processing, model development, and multi-dimensional performance assessment.

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Solution | Function/Purpose | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Frameworks | snnTorch [28] | SNN simulation and encoding | spikegen.latency() for TTFS encoding |

| Intel Lava [8] | Neuromorphic computing | Cross-platform SNN deployment | |

| SpikingJelly [8] | SNN research platform | Surrogate gradient training | |

| Neuromorphic Hardware | Intel Loihi [8] [26] | Event-based processing | Energy-efficient SNN deployment |

| SpiNNaker [8] [26] | Massively parallel SNN simulation | Large-scale network emulation | |

| Encoding Modules | Poisson Generator [28] | Rate coding implementation | spikegen.rate(data, num_steps=100) |

| Latency Encoder [28] | Temporal coding | spikegen.latency(data, tau=10) |

|

| Delta Modulator [28] | Change detection | spikegen.delta(data, threshold=0.1) |

|

| Datasets | MNIST/CIFAR-10 [8] | Benchmark validation | Standardized performance comparison |

| Free Spoken Digit [26] | Temporal pattern recognition | Audio processing applications | |

| Tactile Sensing [24] | Robotic perception | Real-world sensorimotor integration |

Information encoding represents a critical determinant of overall system performance in spiking neural networks, establishing the fundamental representation through which sensory data is transformed into computationally useful spike patterns. Temporal coding schemes offer exceptional efficiency for latency-sensitive applications, while rank order coding provides rapid classification through sparse sequential representations. Population coding delivers robustness and enhanced representational capacity for complex feature spaces. The selective implementation of these approaches—guided by application-specific requirements for accuracy, latency, and energy constraints—enables researchers to harness the full potential of brain-inspired computing paradigms.

Future research directions should focus on adaptive encoding frameworks that dynamically adjust coding strategies based on stimulus characteristics and task demands, hybrid schemes that combine the advantages of multiple approaches, and tighter co-design between encoding algorithms and neuromorphic hardware architectures. As SNN methodologies continue to mature, advanced encoding strategies will play an increasingly pivotal role in bridging the gap between biological information processing and artificial intelligence systems, ultimately enabling more efficient, robust, and adaptive machine intelligence across embedded, robotic, and edge computing domains.

Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs), often regarded as the third generation of neural networks, represent a paradigm shift in brain-inspired computing by mimicking the event-driven and sparse communication of biological neurons [10] [29]. Unlike traditional Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) that rely on continuous-valued activations, SNNs process information through discrete, asynchronous spikes, leading to fundamental computational advantages. These inherent properties position SNNs as a transformative technology for applications where energy efficiency, real-time temporal processing, and computational sparsity are critical, such as in edge AI, neuromorphic vision, robotics, and autonomous space systems [30] [10] [7]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the three core advantages of SNNs—energy efficiency, temporal dynamics, and sparsity—framed within the context of advanced brain-inspired computing research. It offers a detailed examination of the underlying mechanisms, supported by quantitative data from current research and elaborated methodologies for experimental validation.

Energy Efficiency: The Core Driver

The energy superiority of SNNs stems from their event-driven nature. Neurons remain idle until they receive incoming spikes, and communication occurs through binary events, drastically reducing the energy-intensive multiply-accumulate (MAC) operations prevalent in ANNs [10] [29].

Quantitative Energy Analysis

Recent empirical studies across diverse applications demonstrate significant energy reductions.

Table 1: Measured Energy Efficiency of SNNs Across Applications

| Application Domain | Model / Technique | Energy Savings / Consumption | Baseline for Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D Scene Rendering | SpiNeRF (Direct-trained SNN) [29] | Up to 72.95% reduction | Full-precision ANN-based NeRF |

| Natural Language Processing | SpikeBERT with Product Sparsity [31] | 11x reduction in computation | SNN with standard bit sparsity |

| Hardware Acceleration | Prosperity Architecture [31] | 193x improvement in energy efficiency | NVIDIA A100 GPU |

| Unsupervised Learning | STDP-trained SNNs [10] | As low as 5 mJ per inference | Not Specified |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring SNN Energy Efficiency

A standard protocol for a hardware-agnostic theoretical energy estimation, as utilized in space application studies [30] [32], involves the following steps:

- Spike Activity Profiling: Run inference on a target dataset (e.g., EuroSAT for scene classification) and profile the network's activity. The key metric is the average number of spikes per neuron per time step, which determines activity sparsity.

- Energy Model Formulation: Develop an energy model based on the fundamental operations of an SNN. A standard model accounts for:

- Synaptic Operations: Energy consumed when a spike triggers a synaptic weight lookup and membrane potential update. The cost is proportional to the number of incoming spikes and fan-out connections.

- Neuronal Dynamics: Energy required for leak integration, threshold comparison, and reset mechanisms of each neuron at every time step.

- The total energy

E_totalcan be modeled as:E_total = N_spikes * (E_synaptic) + N_neurons * T * (E_leak + E_threshold), whereTis the number of time steps.

- Hardware-Specific Calibration: To predict energy consumption on specific neuromorphic hardware (e.g., BrainChip Akida AKD1000), the theoretical model is calibrated using the hardware's documented energy costs for its primitive operations [30].

- Validation: The model's predictions are validated against actual physical measurements from the hardware platform to ensure accuracy.

Temporal Dynamics: Encoding Time in Computation

SNNs inherently process information encoded in time, as the timing of spikes carries critical information. This makes them exceptionally suited for spatio-temporal data like video, audio, and biomedical signals [10] [33].

Neuron Models with Complex Dynamics

The Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) model is the standard SNN neuron. A more advanced variant, the Adaptive LIF (adLIF) neuron, adds a second state variable for an adaptation current, w(t) [33]. The dynamics are described by:

Membrane Potential Integration:

τ_u * du/dt = -u(t) + I(t) - w(t)whereτ_uis the membrane time constant,u(t)is the membrane potential, andI(t)is the input current.Adaptation Current Dynamics:

τ_w * dw/dt = -w(t) + a * u(t) + b * z(t)whereτ_wis the adaptation time constant,acontrols sub-threshold coupling, andbscales the spike-triggered adaptation.

This negative feedback loop enables complex dynamics like sub-threshold oscillations and spike-frequency adaptation, allowing the network to act as a temporal filter and respond to changes in input spike density [33].

Diagram 1: adLIF neuron dynamics. The adaptation current creates a feedback loop that filters temporal inputs.

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing Temporal Feature Detection

To validate the temporal processing capabilities of an adaptive RSNN, as performed in [33], the following methodology can be employed:

- Network Architecture: Construct a recurrent SNN (RSNN) using adLIF neurons. The Symplectic Euler method is recommended for discretizing neuron dynamics to ensure training stability and model expressivity.

- Dataset: Use spatio-temporal benchmark datasets, such as spiking speech commands (SHD) or event-based vision (DVS128 Gesture).

- Training: Train the network using Backpropagation Through Time (BPTT) with surrogate gradients to approximate the non-differentiable spike function. Crucially, this can be done without batch normalization due to the inherent stability provided by the adaptation mechanism.

- Ablation Study: Compare performance against a control RSNN composed of standard LIF neurons.

- Analysis:

- Evaluate classification accuracy on test sets.

- Probe the network's dynamics by analyzing neuronal responses to input sequences with varying temporal statistics (e.g., sudden changes in spike rate) to demonstrate its robustness and sensitivity to temporal change.

Sparsity: The Key to Computational Efficiency

Sparsity in SNNs is twofold: dynamic sparsity in activation (spikes) and potential static sparsity in connectivity (synaptic weights). This drastically reduces data movement, which is a primary energy bottleneck in von Neumann architectures [31] [34].

Advanced Sparsity Techniques

Beyond inherent activation sparsity, research has developed advanced techniques to enhance sparsity further.

Table 2: Techniques for Enhancing Sparsity in SNNs

| Technique | Mechanism | Reported Performance Gain |

|---|---|---|

| Product Sparsity [31] | Reuses inner product results by leveraging combinatorial similarities in matrix multiplications. Reduces redundant computations. | Density reduced to 1.23% (from 13.19% with bit sparsity). 11x computation reduction. |

| Spatio-Temporal Pruning [34] | Combines spatial pruning (using LAMPS for layer-wise balance) with dynamic temporal pruning to reduce time-steps. | 98.18% parameter reduction with 0.69% accuracy improvement on DVS128 Gesture. |

| Temporal Condensing-and-Padding (TCP) [29] | Addresses irregular temporal lengths in data for hardware-friendly parallel processing, maintaining efficiency. | Enabled high-quality, energy-efficient NeRF rendering on GPUs and neuromorphic hardware. |

Experimental Protocol: Spatio-Temporal Pruning

The methodology for dynamic spatio-temporal pruning, achieving extreme parameter reduction, is outlined below [34]:

Spatial Pruning:

- Initialization: Start with a dense, randomly initialized SNN.

- Training: Train the network for a few epochs to allow connectivity patterns to emerge.

- Scoring: Use the Layer-adaptive Magnitude-based Pruning Score (LAMPS) to assign an importance score to each weight. LAMPS considers global statistics and inter-layer parameter counts to prevent bottlenecks.

- Pruning: Remove a predefined percentage of weights with the lowest scores.

- Rewinding & Retraining: Reset the remaining weights to their values from an early training iteration ("rewinding") and retrain the pruned network. Steps 3-5 are repeated iteratively to achieve the target sparsity.

Temporal Pruning:

- Redundancy Analysis: Analyze the network's activity on sequential data (e.g., from a Dynamic Vision Sensor) to identify layers where the output spike pattern becomes stable before the end of the simulation time window.

- Adaptive Halt: Implement a mechanism that dynamically halts computation for a given sample once the output of a specific layer meets a stability criterion, thus reducing temporal redundancy.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for SNN Experimentation

| Item / Platform | Function / Description | Relevance to SNN Research |

|---|---|---|

| BrainChip Akida AKD1000 [30] | A commercial neuromorphic processor. | Used for validating energy efficiency models and deploying SNNs in power-constrained environments (e.g., space). |

| Surrogate Gradient [10] [33] | A differentiable approximation of the spike function's non-differentiable threshold step. | Enables direct training of deep SNNs using backpropagation through time (BPTT). |

| ANN-to-SNN Conversion [10] [29] | A method to convert a pre-trained ANN into an equivalent SNN. | Provides a path to leverage ANN performance in SNNs, though often at the cost of longer latency. |

| Dynamic Vision Sensor (DVS) [34] | A neuromorphic sensor that outputs asynchronous events (spikes) corresponding to changes in log-intensity of light. | Provides native spatio-temporal input data for SNNs, ideal for testing temporal dynamics. |

| Prosperity Architecture [31] [35] | A specialized hardware accelerator designed for SNNs. | Implements "Product Sparsity" to efficiently handle the combinatorial sparsity patterns in SNN computation. |

The inherent advantages of Spiking Neural Networks—profound energy efficiency, rich temporal dynamics, and multifaceted sparsity—are not merely theoretical. As evidenced by recent breakthroughs in 3D rendering, natural language processing, and extreme model compression, these properties are being quantitatively demonstrated in complex, real-world tasks. The ongoing development of sophisticated training algorithms like surrogate gradient learning, coupled with specialized neuromorphic hardware and sparsity-enhancing techniques, is rapidly closing the performance gap with traditional deep learning while maintaining a decisive edge in efficiency. For researchers and engineers, mastering the experimental protocols and tools surrounding SNNs is crucial for unlocking the next generation of brain-inspired, sustainable, and adaptive computing systems, particularly at the edge and in autonomous applications.

Advanced Training Methods and Emerging Biomedical Applications of SNNs

Spiking Neural Networks (SNNs) represent the third generation of neural network models, offering a brain-inspired alternative to conventional Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) by processing information through discrete, event-driven spikes [10] [36]. This operational paradigm closely mirrors biological neural processes, offering the potential for remarkable energy efficiency and temporal dynamics unmatched by traditional deep learning approaches [37]. However, the fundamental challenge in training SNNs stems from the non-differentiable nature of the spiking mechanism, where the Heaviside step function used in the forward pass results in a derivative that is zero everywhere except at the threshold, where it is infinite [38].

This article examines two groundbreaking approaches that overcome this fundamental barrier: Surrogate Gradient (SG) Descent and Smooth Exact Gradient Descent. Surrogate Gradient methods approximate the derivative during the backward pass to enable gradient-based optimization [39] [38], while Smooth Exact Gradient methods, particularly those using Quadratic Integrate-and-Fire (QIF) neurons, facilitate exact gradient calculation by ensuring spikes appear and disappear only at the trial end [40] [41]. Within the broader context of brain-inspired computing research, these algorithms are pivotal for developing energy-constrained, latency-sensitive, and adaptive applications such as robotics, neuromorphic vision, and edge AI systems [10] [37].

The Fundamental Challenge: Non-Differentiability in SNNs

In spiking neurons, the output spike ( S[t] ) at time ( t ) is generated when the membrane potential ( U[t] ) exceeds a specific threshold ( U_{\rm thr} ):

[ S[t] = \Theta(U[t] - U_{\rm thr}) ]

where ( \Theta(\cdot) ) represents the Heaviside step function. The derivative of this function with respect to the membrane potential is the Dirac Delta function ( \delta(U - U_{\rm thr}) ), which is zero everywhere except at the threshold, where it approaches infinity [38]. This property renders standard backpropagation inapplicable, as gradients cannot flow backward through the non-differentiable spike-generation function.

Surrogate Gradient Descent

Core Principle and Theoretical Foundation

Surrogate Gradient Descent addresses the non-differentiability problem by employing an approximate derivative during the backward pass while maintaining the exact Heaviside function in the forward pass [39] [38]. This method separates the forward and backward pathways: the forward pass uses exact spike-based computation for efficient, event-driven processing, while the backward pass uses a continuous, smoothed surrogate function to estimate gradients.

The surrogate function effectively tricks the optimization process into behaving as if the network were built from differentiable units, enabling the use of standard gradient-based optimizers like Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) and Adam [38] [37]. This approach has become particularly powerful when combined with Backpropagation Through Time (BPTT) for training recurrent spiking networks, allowing SNNs to achieve performance comparable to ANNs in various machine learning tasks [42].

Common Surrogate Functions

Multiple surrogate functions have been proposed, all centered around the threshold and often parameterized by a smoothness factor ( k ).

Fast Sigmoid Surrogate: This function uses a piecewise linear approximation that is computationally efficient [38]. [ \frac{\partial \tilde{S}}{\partial U} = \frac{1}{(k \cdot |U{OD}| + 1.0)^2} ] where ( U{OD} = U - U_{\rm thr} ) represents the membrane potential overdrive.

Sigmoid Surrogate: A smooth sigmoidal function provides a closer approximation to the derivative of the spike function.

- ArcTan Surrogate: The shifted ArcTangent function offers another smooth, analytically tractable alternative [38].

In these functions, the hyperparameter ( k ) controls the sharpness of the approximation. As ( k \rightarrow \infty ), the surrogate derivative converges toward the true Dirac Delta derivative, but in practice, a finite ( k ) (e.g., 25) provides more stable training [38].

Experimental Implementation and Protocol

Implementation with snnTorch: The following code illustrates implementing a Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) neuron with a fast sigmoid surrogate gradient using the snnTorch library [38]:

Workflow Diagram:

Figure 1: Surrogate Gradient Descent Workflow. The forward pass uses exact spike-based computation, while the backward pass employs a surrogate function to enable gradient flow.

Training Protocol for Image Classification:

- Network Architecture: Construct a Convolutional SNN (CSNN) with architecture: 12C5-MP2-64C5-MP2-1024FC10, where 12C5 denotes 12 filters of 5×5 convolution, MP2 is 2×2 max-pooling, and 1024FC10 is a fully-connected layer mapping to 10 outputs [38].

- Data Preparation: Use the MNIST dataset, normalized with mean=0 and std=1. Employ a DataLoader with batch size=128.

- Simulation Parameters: Run simulation for

num_steps=50time steps. Use Leaky Integrate-and-Fire (LIF) neurons with decay ratebeta=0.5. - Optimization: Utilize the Adam optimizer with surrogate gradient descent and cross-entropy loss minimization.

- Performance Metrics: Monitor classification accuracy, loss convergence, and spike activity across training epochs [38].

Performance and Applications

Surrogate gradient-trained SNNs have demonstrated remarkable performance, closely approximating ANN accuracy (within 1-2%) across various benchmarks [10]. They exhibit faster convergence by approximately the 20th epoch and achieve inference latency as low as 10 milliseconds, making them suitable for real-time applications [10].

This approach is particularly effective for energy-constrained applications, with experiments showing substantial energy savings compared to equivalent ANNs, especially when deployed on neuromorphic hardware such as Intel's Loihi or SpiNNaker systems [42] [37].

Smooth Exact Gradient Descent

Core Principle and Theoretical Foundation

In contrast to surrogate methods, Smooth Exact Gradient Descent achieves exact gradient calculation by utilizing neuron models with continuously changing spike dynamics, particularly Quadratic Integrate-and-Fire (QIF) neurons [40] [41]. The key innovation lies in ensuring that spikes only appear or disappear at the end of a trial, where they cannot disrupt subsequent neural dynamics.

The QIF neuron model is governed by the differential equation: [ \dot{V} = V(V-1) + I ] where ( V ) represents the membrane potential and ( I ) represents synaptic input currents. Unlike the LIF model, where ( \dot{V} ) decays linearly with ( V ), the QIF incorporates a voltage self-amplification mechanism that becomes significant once the potential is large enough to generate spike upstrokes [40].

Mechanism of Non-Disruptive Spike (Dis-)Appearance