Precision Neuromodulation: Optimizing TMS Protocols with Neuroimaging and AI for Clinical Translation

This article synthesizes the latest advancements in transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) protocol optimization, a critical endeavor for enhancing the efficacy and reliability of this non-invasive neuromodulation therapy.

Precision Neuromodulation: Optimizing TMS Protocols with Neuroimaging and AI for Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article synthesizes the latest advancements in transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) protocol optimization, a critical endeavor for enhancing the efficacy and reliability of this non-invasive neuromodulation therapy. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational neurobiology of TMS, the critical shift from standardized to personalized targeting methodologies, and the integration of multimodal neuroimaging and artificial intelligence (AI) for precision engagement. The content further addresses current methodological challenges and troubleshooting strategies, evaluates validation through electrophysiological and clinical outcomes, and discusses the future trajectory of TMS towards closed-loop, biomarker-driven systems for neuropsychiatric and neurological disorders.

The Neurobiological Basis of TMS: From Circuit Dysfunction to Targeted Intervention

Core Pathophysiology of Reward and Control Circuits in Neuropsychiatric Disorders

Pathophysiology of Reward and Control Circuits

Dysfunction in the brain's reward and cognitive control circuits is a transdiagnostic feature observed across numerous neuropsychiatric disorders. The core pathophysiology involves disrupted communication between key nodes within the limbic cortico-striatal-thalamic circuit [1].

Key Neural Circuitry and Disruption

Table 1: Core Components of the Reward and Control Circuitry

| Brain Region | Primary Function in Reward/Control | Manifestation of Dysfunction |

|---|---|---|

| Ventral Striatum (VS) / Nucleus Accumbens (NAc) | Incentive salience ("wanting"), reward prediction error coding, goal-directed behavior [2] [1]. | Blunted response to reward anticipation; impaired reward learning; anhedonia [3] [1]. |

| Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA) | Source of dopaminergic projections to VS, PFC, and amygdala; critical for reward signaling [1]. | Dysregulated dopamine release, affecting downstream targets and reward perception [1]. |

| Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex (vmPFC) / Orbitofrontal Cortex (OFC) | Value representation, outcome evaluation, and decision-making [2]. | Impaired value computation and flexible decision-making [2]. |

| Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (DLPFC) | Cognitive control, goal maintenance, and effort allocation [3]. | Reduced activation during cognitive control tasks; inflexible control allocation [3]. |

The interplay between these regions is critical for adaptive behavior. The mesolimbic dopamine pathway, originating in the VTA and projecting to the VS, is central for reward motivation and learning [1]. This pathway is gated and modulated by prefrontal regions, including the DLPFC and vmPFC/OFC [3] [2]. In Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), for example, adolescents show diminished activation in the left DLPFC and bilateral VLPFC during cues requiring high cognitive control, alongside weaker functional connectivity between these regions when rewards are involved [3]. This suggests a core deficit in integrating motivational and control signals.

Theoretical Frameworks for Circuit Dysfunction

The Expected Value of Control (EVC) theory provides a computational framework for understanding these deficits. It posits that cognitive control is allocated based on a cost-benefit analysis, where the brain weighs anticipated rewards against the effort cost of exerting control [3]. In depression, reduced sensitivity to anticipated rewards and an overestimation of effort costs lead to a diminished EVC, resulting in suboptimal allocation of cognitive control and impaired task performance [3]. This is supported by Hierarchical Drift Diffusion Modeling (HDDM) findings showing that depressed adolescents have a reduced starting bias toward rewarding responses and broader decision thresholds in reward contexts [3].

Application to Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Protocol Optimization

The pathophysiological insights guide target selection and parameter refinement for Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) protocols. While the search results primarily detail Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS), the principles of targeting and parameter optimization are analogous and highly informative for TMS research.

Rationale for Target Engagement

TMS protocols can be optimized to modulate specific nodes of the dysregulated reward and control network:

- Stimulating Control Hubs: The DLPFC is a primary TMS target for disorders like MDD. The rationale is that facilitating DLPFC activity can enhance top-down cognitive control over negative emotional processing and improve the allocation of effort towards rewarded behaviors, thereby increasing the perceived EVC [3].

- Modulating Reward Valuation: While deeper structures like the VS are not directly accessible with standard TMS, the vmPFC/OFC can be targeted with specific coil geometries or through connectivity-guided protocols. Modulating this region may help normalize value representation and decision-making processes that are deficient in addiction and depression [2].

Table 2: Key TMS Protocol Parameters and Optimization Considerations

| Parameter | Considerations for Protocol Optimization | Evidence from Neuromodulation Research |

|---|---|---|

| Target | DLPFC (dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) is the most common target. Connectivity-based neuronavigation to specific network nodes (e.g., fronto-striatal circuit) may enhance efficacy [3]. | tDCS studies show that electrode montage (placement) substantially influences outcomes, underscoring the importance of precise targeting [4]. |

| Stimulus Intensity | Typically defined as a percentage of the individual's resting motor threshold (RMT). | In tDCS, intensity effects are non-linear; increasing intensity does not always enhance efficacy and can sometimes reverse effects [4]. This suggests careful titration of TMS intensity is crucial. |

| Pulse Pattern | Standard high-frequency (e.g., 10 Hz) vs. patterned protocols (e.g., Theta Burst Stimulation). | Patterned protocols may induce more robust neuroplastic changes. tDCS research shows "online" stimulation (during task performance) can be more effective than "offline" due to "activity-selectivity" [4]. |

| Number of Sessions | Multi-session protocols are standard for clinical effects. | Systematic reviews of tDCS suggest that interventions with ten or more sessions show more consistent cognitive improvements [5]. |

| Timing | The relationship between stimulation and task performance. | Evidence for "online" tDCS being more effective suggests that applying TMS during the performance of a reward or cognitive control task may optimize target engagement [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating TMS Effects

The following protocols are adapted from methodologies used to study circuit function and neuromodulation.

Protocol 1: Probing Reward-Modulated Cognitive Control with fMRI-navigated TMS

This protocol investigates how TMS over the DLPFC influences behavioral and neural correlates of reward-based decision-making.

- Participants: Recruit patient cohorts (e.g., MDD) and matched healthy controls.

- Task: AX-CPT (Continuous Performance Test) under reward and non-reward conditions [3].

- Cues: Letters "A" or "B" appear as cues.

- Probes: Letters "X" or "Y" appear as probes.

- Condition: The target trial is an "A" cue followed by an "X" probe (AX trial), requiring a specific response. Other combinations (AY, BX, BY) are non-targets.

- Reward Manipulation: In reward blocks, correct and fast responses on a subset of trials (e.g., AX trials) receive monetary or social reward feedback. No rewards are given in neutral blocks.

- Measures:

- Behavioral: Response time (RT) and error rates for AY and BX trials, which require proactive and reactive control [3].

- Computational: Hierarchical Drift Diffusion Modeling (HDDM) to decompose decisions into drift rate, decision threshold, and starting bias [3].

- Neural: Pre- and post-TMS fMRI to assess changes in activation within the reward network (VS, vmPFC) and connectivity between DLPFC and VS.

- TMS Protocol:

- Neuronavigation: Use individual fMRI data to identify the DLPFC target based on functional connectivity with the VS.

- Stimulation: Apply 10 Hz TMS (or intermittent Theta Burst Stimulation) to the left DLPFC. A control group receives sham TMS.

- Timing: "Online" stimulation is applied during the performance of the AX-CPT task.

- Dosage: A multi-session protocol (e.g., 10-15 sessions) is recommended for investigating therapeutic potential [5].

Protocol 2: Optimizing Target Engagement via Behavioral Synchronization

This protocol tests the principle of "activity-selectivity"—that stimulation is most effective when the target network is actively engaged [4].

- Task: A probabilistic reward learning task where participants learn to choose stimuli associated with different reward probabilities.

- Design: A within-subject, crossover design.

- Stimulation Timing:

- Condition A (Online TMS): TMS pulses are applied concurrently with the presentation of the reward-predicting cue or during the reward outcome phase.

- Condition B (Offline TMS): TMS is applied as a priming session before the task begins.

- Outcomes: The primary outcome is the learning rate, measured by the increase in choices for the high-probability reward stimulus. Secondary outcomes include model-based parameters from reinforcement learning models and VS activation measured with concurrent TMS-fMRI.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Simplified Reward Circuit Diagram

Experimental Protocol Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Research on Reward Circuits and Neuromodulation

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| AX-CPT Task | A well-established behavioral paradigm to dissociate proactive and reactive cognitive control and test its modulation by reward contingencies [3]. |

| Hierarchical Drift Diffusion Model (HDDM) | A computational modeling tool to decompose behavioral task performance (e.g., AX-CPT) into distinct cognitive processes such as evidence accumulation rate (drift rate) and response caution (decision threshold), providing deeper insight into the mechanisms of impairment [3]. |

| fNIRS / fMRI | Functional neuroimaging techniques (functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) to measure hemodynamic responses and map neural activity within the reward and control circuits during task performance [3]. |

| Probabilistic Reward Learning Task | A family of tasks (e.g., two-armed bandit) used to assess reward learning and valuation. Critical for probing the function of the VS and vmPFC/OFC and their modulation by TMS [2]. |

| Neuromodulation Platform (TMS/tDCS) | Devices for non-invasive brain stimulation. TMS uses magnetic pulses to induce neuronal depolarization, while tDCS uses weak electrical currents to modulate cortical excitability. Both are used to test causal relationships between brain circuits and behavior [4] [5]. |

| Computational Models (Reinforcement Learning, EVC) | Mathematical models that formalize theories of how the brain learns from rewards (Reinforcement Learning) or allocates control (Expected Value of Control). These models generate quantitative predictions and fit behavioral/neural data [3]. |

| Hdac-IN-31 | Hdac-IN-31, MF:C25H24N4O2, MW:412.5 g/mol |

| Pefloxacin-d3 | Pefloxacin-d3, MF:C17H20FN3O3, MW:336.38 g/mol |

Understanding the dopaminergic, serotonergic, and glutamatergic pathways is fundamental to advancing neuromodulation therapies, particularly transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). These neurotransmitter systems regulate core brain functions—motor control, motivation, emotional affect, and cognition—and are frequently dysregulated in neurological and psychiatric disorders [6]. The efficacy of TMS is critically dependent on its ability to target and modulate these specific neurochemical pathways [7] [8]. This document provides a structured overview of these key systems, quantitative receptor data, and detailed experimental protocols to support research aimed at optimizing TMS parameters for precise engagement of these neurotransmitter pathways.

The following table summarizes the core functions, primary brain pathways, and associated disorders for the three key neurotransmitter systems.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Key Neurotransmitter Systems

| System | Primary Functions | Key Brain Pathways | Associated Disorders |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopaminergic | Motor control, reward, motivation, cognition [9] | Nigrostriatal, Mesolimbic, Mesocortical [10] | Parkinson's disease, Depression, ADHD, Addiction [7] [11] [10] |

| Serotonergic | Mood regulation, sleep, appetite, pain perception [9] | Projections from Dorsal Raphe Nucleus to Cortex, Amygdala, Hippocampus [9] | Depression, Anxiety, Chronic Pain [7] [9] |

| Glutamatergic | Major excitatory neurotransmission, synaptic plasticity, learning & memory [12] | Corticostriatal, Thalamocortical, Hippocampal circuits [7] | Depression, Chronic Pain, Neurodegenerative disorders [7] [9] [12] |

Data from positron emission tomography (PET) studies in healthy individuals provide a normative atlas of receptor density across the human cortex, which is crucial for informing TMS target engagement [6]. The values below represent relative, z-scored density across the cortex for various receptors and transporters.

Table 2: Relative Cortical Receptor and Transporter Density (z-scored) from PET Imaging [6]

| Receptor / Transporter | Mean Density (z-score) | Standard Deviation | Primary Neurotransmitter System |

|---|---|---|---|

| D1 receptor | 0.01 | 1.01 | Dopaminergic |

| D2 receptor | 0.02 | 0.99 | Dopaminergic |

| DAT | -0.03 | 0.98 | Dopaminergic |

| 5-HTâ‚A receptor | -0.01 | 1.02 | Serotonergic |

| 5-HTâ‚B receptor | 0.04 | 0.97 | Serotonergic |

| 5-HTâ‚‚A receptor | 0.05 | 1.03 | Serotonergic |

| SERT | -0.05 | 1.01 | Serotonergic |

| mGluR5 | 0.03 | 0.99 | Glutamatergic |

| NET | 0.00 | 1.00 | Norepinephrine (for comparison) |

Experimental Protocols for TMS Modulation Studies

Protocol 1: Investigating TMS-Induced Dopaminergic Changes in Rodent Models

Application: This protocol is designed to study the effects of high-frequency rTMS on the nigrostriatal and mesolimbic dopaminergic pathways in a rodent model of depression [10].

Workflow Diagram:

Detailed Methodology:

- Animal Model Preparation: Use adult male or female Sprague-Dawley rats. Induce a depression-like phenotype using the Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress (CUMS) paradigm for 4-6 weeks. This involves exposing animals to varying, mild stressors daily (e.g., cage tilt, damp bedding, period of food/water deprivation) [10].

- Behavioral Baseline Assessment: Prior to TMS, assess depression-like behaviors using a test battery:

- Sucrose Preference Test (SPT): Measures anhedonia.

- Forced Swim Test (FST): Measures behavioral despair.

- Open Field Test (OFT): Assesses general locomotor activity and anxiety.

- Elevated Plus Maze (EPM): Further assesses anxiety-like behavior [10].

- rTMS Stimulation Protocol:

- Apparatus: A rodent-specific TMS coil with a compatible stimulator.

- Parameters: Apply 10 Hz rTMS. A typical protocol involves daily sessions for 15 days, with each session consisting of multiple trains (e.g., 50-100 trains), each train lasting 4-10 seconds with an inter-train interval of 26-60 seconds [10].

- Targeting: The coil is positioned over the skull to target the prefrontal cortex. A sham stimulation group (coil placed at an angle or using a sham coil) must be included for control.

- Post-Stimulation Assessment: Re-run the behavioral test battery (SPT, FST, OFT, EPM) 24 hours after the final TMS session.

- Tissue Preparation and Analysis:

- Brain Extraction: Euthanize animals and perfuse transcardially with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Extract and post-fix brains.

- Immunofluorescence: Section brain regions of interest (e.g., dorsal striatum, prefrontal cortex). Incubate sections with primary antibodies against Tyrosine Hydroxylase (TH) and Dopamine D2 Receptors (D2R), followed by appropriate fluorescently-conjugated secondary antibodies [10].

- Imaging & Quantification: Use a confocal or fluorescence microscope to acquire images. Quantify fluorescence intensity or the number of labeled cells in defined regions using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ).

Protocol 2: Human TMS Target Engagement with Neuroimaging

Application: This protocol outlines a method for personalized TMS target engagement of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) based on individual functional neuroimaging and structural connectivity, primarily aiming to modulate the serotonergic and glutamatergic systems implicated in depression [8] [13].

Workflow Diagram:

Detailed Methodology:

- Participant Screening and MRI Acquisition: Recruit eligible patients (e.g., with Major Depressive Disorder). Acquire high-resolution T1-weighted structural MRI, resting-state functional MRI (fMRI), and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) data [8] [13].

- Target Identification:

- Functional Targeting: Process resting-state fMRI data to identify the specific area within the left DLPFC that is most anti-correlated with the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (sgACC), a key node in depressive pathology [13].

- Structural Connectivity: Process DWI data using tractography to map the structural connectivity of the target region, particularly focusing on pathways like the cingulum bundle [8].

- Neuronavigation Setup: Import the structural MRI and the identified target coordinates into a frameless stereotactic neuronavigation system. Co-register the patient's head to their MRI scan prior to the first TMS session.

- TMS Stimulation Protocol:

- Apparatus: A navigated TMS system with a figure-of-eight coil.

- Protocol Selection: Apply intermittent Theta Burst Stimulation (iTBS) or 10 Hz rTMS.

- iTBS Parameters: 3-pulse 50 Hz bursts repeated at 5 Hz (theta frequency). A common protocol is 2-second trains repeated every 10 seconds for a total of 600 pulses per session [7] [14].

- Targeting: Use the neuronavigation system to ensure precise and consistent coil placement over the personalized DLPFC target throughout the treatment course. The coil angle is often adjusted to induce a posterior-anterior current flow in the cortex [8].

- Outcome Monitoring: Assess clinical symptoms using standardized scales like the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS-17) or Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) at baseline, weekly during treatment, and at follow-ups [14].

- Neurophysiological Verification (Optional): Use concurrent TMS with electroencephalography (TMS-EEG) to record and analyze TMS-evoked potentials (TEPs), providing a direct measure of cortical reactivity and target engagement at the neurophysiological level [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Neurotransmitter & TMS Research

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Selective Antibodies | Immunohistochemical labeling of specific proteins in tissue. | Anti-Tyrosine Hydroxylase (TH) for dopaminergic neurons; Anti-Dopamine D2 Receptor (D2R); Anti-5-HTâ‚A/5-HTâ‚‚A receptors [10]. |

| Radiolabeled PET Tracers | In vivo quantification of receptor/transporter density in humans. | [¹¹C]SCH23390 (D1 receptor); [¹¹C]raclopride (D2 receptor); [¹¹C]DASB (SERT); [¹¹C]ABP688 (mGluR5) [6]. |

| TMS-Compatible Neuromavigator | Precises positioning of TMS coil over individualized brain target. | Systems that integrate real-time MRI and/or fMRI data with optical tracking of the patient's head and TMS coil [8] [13]. |

| High-Density TMS-EEG System | Direct measurement of TMS-induced cortical potentials and oscillations. | A 64+ channel EEG system with hardware and software designed to suppress TMS-induced artifacts, allowing clean recording of TMS-evoked potentials [8]. |

| d-cycloserine & Lisdexamfetamine | Pharmacological augmentation of TMS to enhance neuroplasticity. | Used in accelerated protocols (e.g., ONE-D) to potentially potentiate NMDA receptor-dependent plasticity and enhance catecholamine release [14]. |

| Asperglaucin B | Asperglaucin B, MF:C19H26O3, MW:302.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Galectin-3-IN-2 | Galectin-3-IN-2, MF:C24H30FN3O10S, MW:571.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Signaling Pathway Integration in TMS

The therapeutic effects of TMS are mediated through the modulation of complex, interconnected signaling pathways. The following diagram synthesizes the key neurochemical interactions influenced by TMS, particularly in the context of depression and chronic pain comorbidity [7] [9].

Pathway Diagram:

As illustrated, TMS acts on a network level. For example, high-frequency stimulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex can lead to dopamine release in the striatum [7], modulate serotonin from the dorsal raphe nucleus [9], and induce long-term potentiation (LTP)-like plasticity through glutamatergic NMDA receptor activation [7]. This simultaneous modulation of multiple neurotransmitter systems underpins the broad therapeutic potential of TMS for complex neuropsychiatric disorders.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) has emerged as a powerful non-invasive tool for modulating brain networks and inducing neuroplastic changes. By generating focused magnetic fields that induce electrical currents in targeted cortical regions, TMS can transiently or lastingly alter neural excitability and connectivity. The therapeutic potential of TMS is increasingly being realized across various neurological and psychiatric disorders, particularly through repetitive TMS (rTMS) protocols that can produce neuroplastic effects outlasting the stimulation period. This review synthesizes current theoretical frameworks explaining how TMS induces neuroplasticity and modulates brain networks, with particular emphasis on protocol optimization for research and clinical applications. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing targeted, effective neuromodulation therapies, especially for conditions characterized by network dysconnectivity, where functional integration between brain regions is profoundly disturbed [15].

Theoretical Foundations of TMS-Induced Neuroplasticity

Basic Mechanisms of TMS Action

TMS operates on the principle of electromagnetic induction, where a brief, high-intensity current passed through a coil placed on the scalp generates a time-varying magnetic field perpendicular to the coil. This magnetic field, typically reaching 1-3 cm into the cortex, induces a secondary electrical current in the underlying brain tissue that can depolarize neurons and generate action potentials. The neurophysiological effects of TMS depend critically on stimulation parameters, particularly frequency. Low-frequency rTMS (≤1 Hz) generally suppresses cortical excitability, while high-frequency rTMS (≥5 Hz) tends to facilitate it. The pattern of stimulation also significantly influences outcomes, as evidenced by theta-burst stimulation (TBS), which delivers high-frequency pulses in short bursts to mimic natural theta rhythms and can produce rapid, powerful, and lasting plasticity [16] [17].

The after-effects of rTMS are believed to be mediated by neuroplastic mechanisms similar to long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD). These involve complex molecular cascades including NMDA receptor activation, calcium influx, and subsequent changes in gene expression and protein synthesis that ultimately modify synaptic strength. Research using NMDA receptor blockers has provided causal evidence for the role of these receptors in rTMS after-effects, demonstrating that the plasticity-inducing effects can be pharmacologically disrupted [18] [19].

Network-Level Effects of TMS

While early TMS research focused predominantly on local effects at the stimulation site, contemporary frameworks emphasize that TMS modulates distributed brain networks. The effects of TMS are not confined to the targeted region but propagate to anatomically and functionally connected remote areas through established neural pathways. This network modulation is particularly relevant for therapeutic applications, as many neurological and psychiatric disorders involve distributed network disturbances rather than isolated regional dysfunction [15] [20].

Concurrent TMS-fMRI studies have robustly demonstrated that stimulating one node of a network can modulate activity throughout the entire network. For instance, TMS over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) - a common target for depression treatment - acutely modulates connectivity within critical brain circuits including the cognitive control network and default mode network. These network-level changes correlate with clinical improvement, suggesting they represent a key mechanism of therapeutic action [21]. The state of the targeted network at the time of stimulation significantly influences TMS effects, supporting the concept of "state-dependency" where current brain activity patterns shape response to neuromodulation [20].

Key Neuroplasticity Mechanisms

Synaptic Plasticity and Homeostatic Metaplasticity

The after-effects of rTMS are primarily mediated through activity-dependent synaptic plasticity. The induced electrical fields can alter the timing of pre- and postsynaptic spikes, potentially engaging spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) mechanisms that strengthen or weaken synaptic connections based on temporal correlations. Repeated TMS sessions are thought to cumulatively modify synaptic weights in targeted circuits, leading to lasting reorganization of functional networks [18].

Homeostatic metaplasticity mechanisms ensure that neural activity operates within dynamic physiological ranges. The brain's response to TMS is influenced by its recent history of activity, with prior neural activity levels potentially shifting the threshold for subsequent plasticity induction. This homeostatic regulation may explain some of the variability in TMS responses across individuals and sessions, and highlights the importance of considering stimulation history in protocol design [18].

Oscillatory Entrainment and Phase-Dependent Effects

TMS can entrain neural oscillations by synchronizing the firing patterns of neuronal populations. This is particularly evident with patterned protocols like TBS, but also occurs with conventional rTMS. The phase of ongoing oscillations represents a brain state that influences neuronal excitability and responsiveness to stimulation. Emerging evidence suggests that synchronizing TMS pulses to specific phases of endogenous rhythms (e.g., alpha oscillations) can enhance efficacy and reduce interindividual variability in response [21] [19].

Combined TMS-EEG studies have demonstrated that the phase of oscillatory activity at the time of stimulation significantly influences TMS effects. For instance, delivering TMS pulses at the peak phase of beta oscillations in the motor cortex produces facilitatory after-effects, while stimulation at the trough phase may be inhibitory. This phase-dependency offers promising avenues for optimizing stimulation timing to maximize target engagement [19].

Neurotransmitter Systems

TMS-induced plasticity involves multiple neurotransmitter systems, including glutamate (for excitatory transmission), GABA (for inhibitory transmission), and monoamines (for neuromodulation). Different TMS protocols appear to engage distinct neurotransmitter systems - for example, short-interval intracortical inhibition (SICI) is thought to reflect GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition, while intracortical facilitation (ICF) involves glutamatergic NMDA receptors. Short-latency afferent inhibition (SAI) provides a marker of cholinergic function, and has been shown to be modulated by specific TMS protocols [19].

The differential engagement of neurotransmitter systems by various TMS parameters provides a neurochemical basis for protocol optimization. Understanding these neurochemical effects is particularly important for developing TMS as a therapeutic tool, as different neuropsychiatric conditions involve distinct neurotransmitter imbalances.

Table 1: Neuroplasticity Mechanisms in TMS

| Mechanism | Key Processes | Relevant TMS Protocols | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synaptic Plasticity | LTP/LTD-like effects; NMDA receptor activation; calcium-dependent signaling | rPPS; iTBS; cTBS | NMDA receptor blockade abolishes facilitatory after-effects [19] |

| Oscillatory Entrainment | Phase-dependent effects; neural synchronization; cross-frequency coupling | EEG-synchronized TMS; tACS-TMS combinations | Enhanced efficacy with phase-locked stimulation [21] |

| Neurotransmitter Modulation | GABAergic inhibition; glutamatergic excitation; cholinergic modulation | LF-rTMS (GABA); HF-rTMS (glutamate); SAI protocols (ACh) | SICI (GABAA) and LICI (GABAB) changes post-TMS [19] |

| Network Reorganization | Functional connectivity changes; network topology shifts; pathway strengthening | DLPFC stimulation for depression; M1 stimulation for motor disorders | fMRI demonstrated DMN, CCN modulation [21] [20] |

Measuring and Quantifying TMS Effects

Neurophysiological Measures

Motor evoked potentials (MEPs) recorded via electromyography represent the gold standard for quantifying TMS effects on corticospinal excitability. Beyond MEP amplitude, various paired-pulse TMS paradigms permit assessment of specific inhibitory and facilitatory circuits within the motor cortex. These include short-interval intracortical inhibition (SICI), intracortical facilitation (ICF), short-latency afferent inhibition (SAI), and long-interval intracortical inhibition (LICI), each probing distinct neuropharmacological mechanisms [15] [19].

TMS combined with electroencephalography (TMS-EEG) provides a direct measure of cortical reactivity and connectivity beyond the motor system. TMS-EEG can capture TMS-evoked potentials (TEPs) and oscillatory responses across the cortex, offering insights into local and network-level excitability and connectivity. This approach is particularly valuable for assessing TMS effects in non-motor regions targeted for therapeutic applications [15].

Functional Connectivity and Network Analysis

Resting-state functional connectivity analyses, derived from either fMRI or EEG, enable quantification of TMS-induced changes in network organization. Studies have demonstrated that rTMS can modify functional connectivity patterns in distributed networks, with these changes often correlating with clinical improvements. For example, in mal de debarquement syndrome, rTMS-induced symptom changes were correlated with connectivity changes in the alpha band over parietal and occipital cortices [15].

Independent component analysis (ICA) of fMRI data has revealed that TMS over the primary motor cortex modulates not only the targeted motor network but also non-motor networks including those involved in bodily self-consciousness, such as the insular and rolandic operculum systems. These widespread effects highlight the network-level actions of TMS and underscore that stimulation at any node influences distributed brain systems [20].

Table 2: Quantitative Measures of TMS-Induced Neuroplasticity

| Measure | Methodology | Neural Correlate | Application in Protocol Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motor Evoked Potentials (MEP) | EMG recording from target muscle | Corticospinal excitability | Determining stimulation intensity; measuring facilitatory/inhibitory effects |

| Paired-Pulse Paradigms (SICI, LICI, ICF, SAI) | Condition-test pulse sequences | Intracortical inhibition/facilitation; cholinergic function | Probing specific neurotransmitter systems; target engagement verification |

| TMS-Evoked Potentials (TEPs) | EEG response to TMS pulses | Cortical reactivity and connectivity | Assessing direct cortical responses in non-motor regions |

| Resting-State Functional Connectivity | fMRI or EEG correlation analysis | Network integration and segregation | Evaluating network-level treatment effects; identifying novel targets |

| Oscillatory Power and Synchronization | Spectral analysis of EEG | Local and network oscillations | State-dependent stimulation; entrainment effects |

| Behavioral Measures | Task performance | Cognitive/motor function | Linking neurophysiological effects to functional outcomes |

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Standard rTMS Protocols for Research

Depression Protocol (DLPFC Stimulation)

- Target: Left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC)

- Localization: EEG 10-20 system (F3) or neuronavigation based on individual anatomy

- Parameters: 10 Hz frequency, 120% resting motor threshold, 4-second train duration, 26-second intertrain interval, 3000 pulses per session

- Session Schedule: Daily sessions for 4-6 weeks

- Mechanistic Basis: Modulates cognitive control network and default mode network connectivity; normalizes prefrontal-limbic interactions [21]

Motor Cortex Plasticity Protocol

- Target: Primary motor cortex (M1) hand area

- Localization: Motor hotspot identified via single-pulse TMS

- Parameters:

- Facilitatory: 10 Hz at 80-90% RMT or iTBS (2-second trains, 8-second intervals)

- Inhibitory: 1 Hz at 100-110% RMT or cTBS (continuous theta burst)

- Outcome Measures: MEP amplitude, SICI, ICF, SAI

- Applications: Studying basic plasticity mechanisms; developing protocols for motor recovery [19]

State-Dependent and Personalized Protocols

Emerging approaches aim to optimize TMS efficacy by personalizing stimulation parameters based on individual brain anatomy, connectivity, and dynamic state:

EEG-Guided Phase-Locked TMS

- Principle: Deliver TMS pulses at specific phases of endogenous oscillations

- Implementation: Real-time EEG analysis with trigger generation for TMS

- Evidence: Enhanced and more consistent plasticity effects when stimulating at peak of sensorimotor beta oscillations [21] [19]

fMRI-Neuronavigated Targeting

- Principle: Target stimulation based on individual functional connectivity profiles

- Implementation: Identify stimulation targets based on rs-fMRI connectivity maps

- Evidence: Improved clinical outcomes in depression when targeting DLPFC regions with strongest negative connectivity to subgenual cingulate [21]

Combined TMS-tACS Protocols

- Principle: Modulate oscillatory activity with tACS while inducing plasticity with TMS

- Implementation: Simultaneous application of tACS and TMS with precise phase relationship

- Evidence: rPPS synchronized to peak phase of β-tACS enhanced and stabilized facilitatory after-effects in M1 [19]

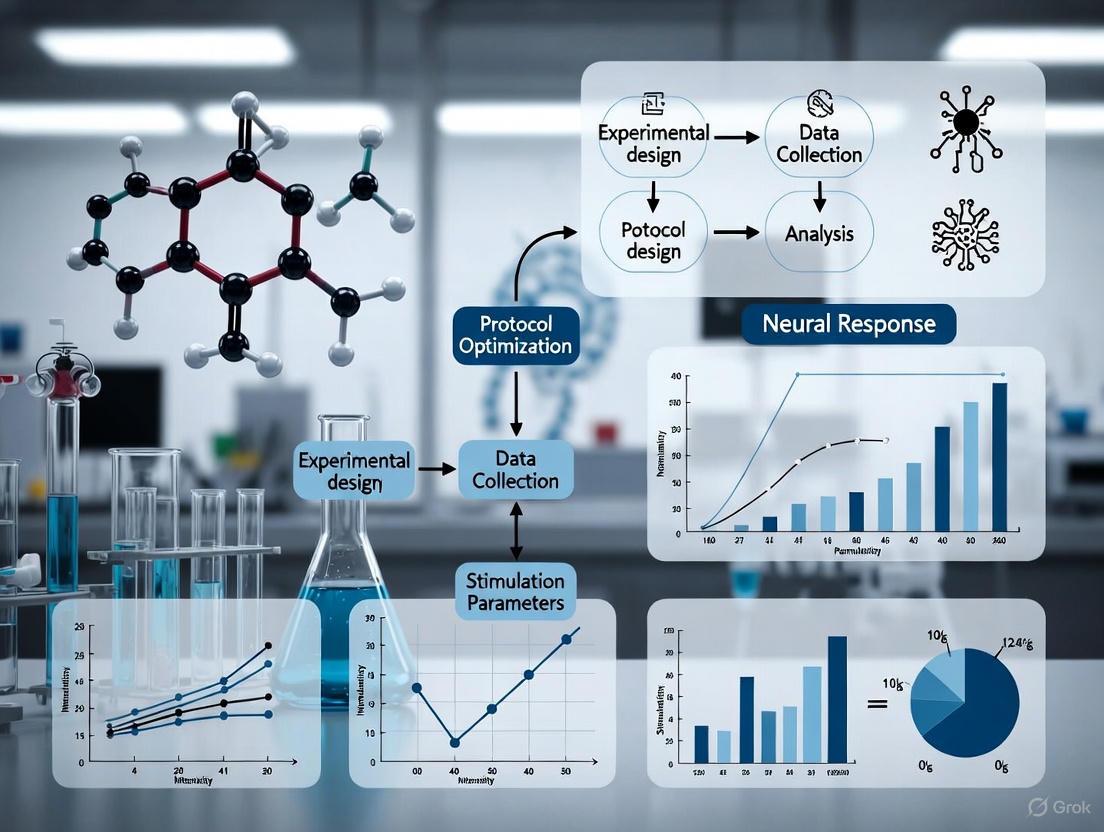

TMS Protocol Development Workflow: This diagram illustrates the iterative process for developing and optimizing TMS protocols, highlighting key decision points and individualization factors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for TMS Neuroplasticity Studies

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMS Devices | DuoMAG MP-Quad TMS; MagVenture; Brainsway | Delivering precise magnetic stimulation | Output characteristics; coil types; cooling systems |

| Neurophysiological Monitoring | EMG systems; EEG with TMS-compatible amplifiers; fMRI | Measuring TMS effects | Compatibility with TMS; artifact handling; temporal resolution |

| Neuronavigation | MRI-based systems (BrainSight; Localite); 3D camera systems | Precision targeting | Accuracy; registration methods; real-time tracking |

| Pharmacological Agents | NMDA receptor antagonists; GABAA agonists; cholinergic drugs | Probing plasticity mechanisms | Dosage; timing; safety with TMS |

| Behavioral Tasks | Cognitive batteries; motor learning paradigms; mood scales | Linking plasticity to function | Sensitivity to change; reliability; clinical relevance |

| Computational Tools | Electric field modeling; network analysis; signal processing | Predicting and analyzing effects | Realism of models; computational demands |

| TRPA1 Antagonist 1 | TRPA1 Antagonist 1 is a potent, selective channel blocker for pain and inflammation research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals | |

| Cletoquine-d4-1 | Cletoquine-d4-1, MF:C16H22ClN3O, MW:311.84 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The theoretical frameworks explaining TMS-induced neuroplasticity have evolved from simplistic excitation/inhibition models toward sophisticated network-level perspectives that account for state-dependent, oscillatory, and neurotransmitter-mediated mechanisms. The future of TMS protocol optimization lies in personalized approaches that integrate individual structural and functional neuroimaging, real-time state assessment, and closed-loop systems that adapt stimulation parameters based on ongoing brain activity. As research continues to elucidate the complex relationships between TMS parameters and neuroplastic outcomes, we move closer to realizing the full potential of this powerful neuromodulation technique for both basic neuroscience and therapeutic applications.

Further validation of biomarker-driven approaches and refinement of state-dependent stimulation protocols will be essential for enhancing the precision and efficacy of TMS interventions. The integration of TMS with other neuromodulation techniques, such as tACS, represents a promising frontier for inducing more specific and powerful neuroplastic changes. As these approaches mature, they will undoubtedly expand the therapeutic reach of TMS across a broader range of neurological and psychiatric conditions characterized by network dysfunction.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) has emerged as a promising therapeutic tool for various neurological and psychiatric disorders. The efficacy of TMS is critically dependent on the precise selection of stimulation targets, which requires a deep understanding of the functional roles and neurocircuitry of specific brain regions. This protocol optimization research focuses on four key cortical targets: the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), pre-supplementary motor area (pre-SMA), insula, and subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (sgACC). These regions form critical nodes in networks governing cognitive control, emotional regulation, and decision-making processes. Understanding their distinct functions and interconnections enables more precise TMS targeting, potentially enhancing treatment outcomes for conditions including depression, addiction, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and clinicians, integrating current neuroanatomical, functional, and methodological insights to refine TMS protocols.

The following table summarizes the core functional roles and associated networks of the four target regions.

Table 1: Functional Profiles of Key TMS Targets

| Brain Region | Primary Functional Roles | Associated Networks/Pathways | Behavioral/Cognitive Correlates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex (DLPFC) | Executive control, working memory, adaptive coding of task-relevant information [22], conflict-induced behavioral adaptation [23]. | Multiple-Demand (MD) Network; top-down modulation of sensory and association cortices [22]. | Cognitive control, planning, behavioral flexibility. |

| Pre-Supplementary Motor Area (Pre-SMA) | Cognitive motor control, response selection, conflict monitoring [23]. | Cingulo-Opercular Network [24]. | Action planning, error detection, sequence learning. |

| Anterior Insula (aINS) | Interoceptive awareness, salience processing, risk assessment, integrating bodily states into subjective feeling [25] [26]. | Salience Network; functional connectivity with amygdala-striatal reward circuit (vAI) and prefrontal control system (dAI) [25]. | Risk-taking tendency [26], emotional experience, urge generation. |

| Subgenual Anterior Cingulate Cortex (sgACC) | Emotional processing, reward learning, autonomic regulation. | Default Mode and Affective Networks; target for antidepressant TMS via connectivity with DLPFC [24]. | Negative affect, mood regulation, visceral responses to emotion. |

Functional Connectivity and Circuit-Based Targeting

Effective TMS protocols are increasingly based on functional connectivity profiles. The distinct sub-regions of our targets interact with specific circuits to mediate behavior.

Insula Subdivisions and Their Networks

The insula is not a unitary structure. A tripartite subdivision reveals specialized functions and connectivity patterns crucial for somatic marker hypothesis and interoceptive processing [25]:

- Posterior Insula (PI): Primarily connected to the visceral-sensorimotor system, receiving and integrating interoceptive signals.

- Ventral Anterior Insula (vAI): Predominantly connected to the amygdala-striatal system, modulating reward-seeking and emotional processes.

- Dorsal Anterior Insula (dAI): Predominantly connected to prefrontal regions, modulating self-control and higher-order cognitive processes [25].

Quantitatively, cognitive performance is positively correlated with functional connectivity (FC) between the dAI and the ventrolateral PFC, and negatively correlated with FC between the vAI and reward-related regions like the orbitofrontal cortex and sgACC [25].

DLPFC in Top-Down Facilitation

Causal evidence from concurrent TMS-fMRI studies demonstrates that the DLPFC is necessary for enhancing the coding of task-relevant information across the frontoparietal network. Disruption of the right DLPFC with TMS specifically decreases the representation of attended stimulus features, with no statistically detectable effect on irrelevant information [22]. This supports a primary role for the DLPFC in facilitatory mechanisms rather than direct inhibition.

Cross-Dataset Validation for Target Identification

Robust target identification, particularly for disorders like ADHD, can be achieved by combining meta-analysis with cross-dataset validation of functional connectivity. This approach has identified consistent brain surface targets, including the DLPFC, right inferior frontal gyrus, and pre-SMA/SMA, by analyzing resting-state fMRI data from independent cohorts [27]. This method enhances the generalizability and reliability of identified TMS locations.

Experimental Protocols for Target Validation

Protocol 1: Functional Connectivity Mapping for Target Engagement

This protocol details how to identify a patient-specific DLPFC target based on its anti-correlation with the sgACC, a common clinical approach.

- Objective: To derive an individualized TMS target for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) treatment by mapping the DLPFC region with strongest negative functional connectivity to the sgACC.

- Materials: MRI scanner, T1-weighted structural imaging protocol, resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI) protocol, data processing software (e.g., SPM, FSL, or DPABI).

- Procedure:

- Data Acquisition: Acquire high-resolution T1-weighted structural images and a 10-minute rs-fMRI scan (eyes open, fixating on a cross) for each participant.

- Preprocessing: Process rs-fMRI data using a standard pipeline, including slice-timing correction, realignment, normalization to MNI space, and smoothing with a 6mm Gaussian kernel. Regress out nuisance signals (white matter, cerebrospinal fluid, motion parameters).

- Seed-Based FC Analysis:

- Define a spherical seed region of interest (ROI) for the sgACC (e.g., MNI coordinates: ±x, y, z).

- Extract the average BOLD time series from the sgACC seed.

- Calculate the Pearson's correlation coefficient between this seed time series and the time series of every other voxel in the brain.

- Convert correlation coefficients to z-scores using Fisher's transformation to create a subject-level FC map.

- Target Identification: Identify the voxel or cluster within the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex mask that shows the highest negative correlation (strongest anti-correlation) with the sgACC seed. This peak coordinate defines the patient-specific TMS target.

Protocol 2: Concurrent TMS-fMRI for Causal Mechanism Investigation

This protocol leverages multimodal integration to test the causal influence of a stimulated site on network function and information processing.

- Objective: To assess the causal effect of DLPFC stimulation on the coding of task-relevant information in distal brain regions using concurrent TMS-fMRI.

- Materials: MRI-compatible TMS system, head coil with integrated TMS unit, task-based fMRI paradigm, multivariate pattern analysis (MVPA) software.

- Procedure:

- Localization: Neurologically coregister the TMS coil position to the individual's structural MRI. Define the DLPFC target using the 10-20 EEG system (e.g., F3/F4) or an fMRI-guided neuronavigation system.

- Stimulation Paradigm: Employ a within-subjects design with Active (e.g., 110% motor threshold) and Control (e.g., 40% motor threshold) TMS intensities. During fMRI, deliver a short TMS train (e.g., 3 pulses at 13 Hz) on each trial of a cognitive task (e.g., a feature-selection task where participants attend to one stimulus dimension and ignore another) [22].

- Imaging & Analysis:

- Acquire whole-brain fMRI data during the task under both TMS conditions.

- Use Multivariate Pattern Analysis (MVPA) to quantify the strength of task-relevant and task-irrelevant information coding in regions of interest (e.g., frontoparietal network, visual cortices).

- Statistically compare the information coding strength between Active and Control TMS conditions across the brain.

Protocol 3: Behavioral Assay for Insula-Mediated Risk-Taking

This protocol details a behavioral task suitable for probing the function of the anterior insula, which can serve as a biomarker for target engagement.

- Objective: To quantify individual differences in risk-taking tendency relevant to insula function using the Analgesic Decision-making Task (ADT) [26].

- Materials: Paper-and-pencil or computerized version of the ADT, questionnaires for prior pain experience and imagined pain relief.

- Procedure:

- Task Administration: Present participants with 22 figurative scenarios across three sub-tasks: Analgesic Effect (ANE), Adverse Effect (ADE), and Time-course Effect (TE). In each scenario, participants choose between a "riskless" (conservative) and a "riskier" (more potent but less certain/slower/riskier) analgesic treatment.

- Behavioral Quantification: Calculate a Risk Preference Index (RPI) for each participant as the total frequency of choosing the riskier option across all scenarios (RPI = Nriskier / 22). Calculate sub-scores (RPIANE, RPI_ADE, RPITE) for each task domain.

- Correlation with Neural Measures: In a research context, the RPI can be correlated with structural (e.g., grey matter volume) and functional (e.g., degree centrality) signatures of the anterior insula to validate its behavioral relevance [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for TMS Protocol Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MRI-Compatible TMS System | Allows for precise, neuronavigated stimulation and concurrent causal investigation of network effects. | Systems from MagVenture, Magstim, or Neurosoft with specialized MR coils. Critical for Protocol 2. |

| Neuromavigation System | Precisely coregisters the TMS coil with the subject's neuroanatomy for accurate target engagement. | Brainsight, Localite, or Visor2 systems that use infrared tracking. |

| Functional Connectivity Toolboxes | Software for preprocessing and analyzing resting-state and task-based fMRI data. | CONN, DPABI, FSL, SPM12. Used for seed-based correlation analysis in Protocol 1. |

| Analgesic Decision-Making Task (ADT) | A behavioral probe for quantifying risk-taking tendency, linked to anterior insula function. | Paper-and-pencil or computerized version [26]. Used as a behavioral assay in Protocol 3. |

| Multivariate Pattern Analysis (MVPA) Toolbox | Decodes information content from distributed patterns of brain activity in fMRI data. | The Princeton MVPA Toolbox, PyMVPA, or custom scripts in Python/MATLAB. Essential for analyzing data in Protocol 2. |

| High-Definition TMS Cap | Improves the precision and focality of TMS stimulation without neuronavigation. | 4x1 ring configuration caps for HD-TMS from companies like Soterix Medical. |

| Pyrimethanil-13C,15N2 | Pyrimethanil-13C,15N2, MF:C12H13N3, MW:202.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| FTase Inhibitor III | FTase Inhibitor III – Farnesyltransferase Inhibitor | FTase Inhibitor III is a cell-permeable inhibitor that blocks Ras protein processing. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Signaling Pathways and Logical Workflows

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the key functional relationships and experimental workflows described in this article.

Functional Networks of Insula Subregions

DLPFC Causal Facilitation Mechanism

TMS Target Identification Workflow

Advanced TMS Methodologies: From Standardized Protocols to Personalized Targeting

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) has emerged as a cornerstone non-invasive neuromodulation technique in clinical neuroscience and psychiatry. Within its arsenal, several distinct protocols have been developed and refined, each with unique mechanisms and therapeutic applications. This analysis focuses on three predominant TMS modalities: conventional repetitive TMS (rTMS), the patterned protocol Theta Burst Stimulation (TBS), and Deep TMS. The optimization of these protocols is critical for enhancing treatment efficacy, efficiency, and accessibility across various neuropsychiatric conditions, particularly treatment-resistant depression (TRD). The evolution from standardized, one-size-fits-all rTMS protocols toward personalized, biomarker-guided approaches represents the forefront of TMS research and development [28] [29].

Comparative Efficacy and Safety Profiles

Quantitative data from recent meta-analyses and clinical trials provide a foundation for comparing the clinical outcomes of different TMS protocols. The tables below summarize key efficacy and safety parameters across multiple neurological and psychiatric indications.

Table 1: Comparative Efficacy of TMS Protocols in Treatment-Resistant Depression

| Protocol | Stimulation Parameters | Session Duration | Remission Rates | Key Comparative Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 Hz rTMS | 10 Hz, 3000 pulses/session | ~37.5 minutes [30] | 20-30% [29] | Similar efficacy to TBS; robust evidence base [31] |

| Standard iTBS | 50 Hz bursts, 600 pulses/session | ~3-10 minutes [31] [29] | 20-30% [29] | Non-inferior to 10 Hz rTMS for TRD [31] |

| Accelerated iTBS (SNT/PAiT) | 50 Hz bursts, 1800 pulses/session, 10 sessions/day for 5 days | ~10 minutes/session [29] | Up to ~79% [29] | High remission in studies; requires further validation [29] |

| Deep TMS | H-coil, 18-20 Hz | ~20 minutes | Not specified in results | Investigational for TRD [28] |

Table 2: Protocol Performance Across Other Neurological Conditions

| Condition | Most Effective Protocol | Key Outcome | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Stroke Motor Recovery | ≥10 Hz rTMS (mild/severe, convalescent phase); iTBS (acute/subacute phase) [32] | Best for upper limb function & daily living [32] | Network Meta-Analysis of 95 RCTs [32] |

| Parkinson's Disease Depression | rTMS (DLPFC-targeted) | Improves depressive symptoms [7] | Mechanism: Prefrontal-striatal dopamine pathway modulation [7] |

| Late-Life Depression | Bilateral or High-Frequency rTMS [33] | Remission rates: 20-63% [33] | Scoping Review (16 studies) [33] |

| PD Anxiety | cTBS (DLPFC-targeted) | Potential anxiolytic effects [7] | Indirect amygdala/hippocampal regulation [7] |

Table 3: Safety and Tolerability Profile

| Adverse Event | rTMS vs. TBS (Odds Ratio) | Statistical Significance | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Headache | OR = 1.00 [31] | Not significant (CI: 0.72-1.40) | Most common, typically transient and self-limiting [29] [33] |

| Nausea | OR = 1.42 [31] | Not significant (CI: 0.79-2.54) | |

| Fatigue | OR = 0.87 [31] | Not significant (CI: 0.46-1.64) | |

| Scalp Discomfort | Not quantitatively compared | Common to all protocols | Well-tolerated; rarely leads to discontinuation [29] [33] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standard 10 Hz rTMS for TRD

- Objective: To alleviate depressive symptoms in patients with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) or Treatment-Resistant Depression (TRD).

- Methodology:

- Rationale: High-frequency stimulation increases cortical excitability in the left DLPFC, a key node in the affective network [7] [17].

Accelerated iTBS (PAiT/SNT Protocol)

- Objective: To induce rapid remission in TRD through intensive, personalized stimulation.

- Methodology:

- Personalized Targeting: Target the left DLPFC subregion with strongest functional MRI (fMRI) anticorrelation to the subgenual Anterior Cingulate Cortex (sgACC) using resting-state fMRI [28] [29].

- Parameters: iTBS pattern, 1800 pulses per session, intensity at 90% of resting motor threshold [29].

- Accelerated Course: 10 sessions per day, with a 50-minute inter-session interval, over 5 days (50 sessions total) [29].

- Rationale: Functional connectivity-guided targeting may more effectively modulate dysfunctional mood circuits, while the accelerated, spaced schedule enhances synaptic strengthening via long-term potentiation-like mechanisms [7] [29].

Post-Stroke Motor Rehabilitation Protocol

- Objective: To improve upper limb motor function and activities of daily living (ADL) post-stroke.

- Methodology:

- Paradigm Selection: Choose protocol based on stroke phase [32]:

- Acute/Subacute Phase (<3 months): iTBS to affected motor cortex or 1 Hz rTMS to unaffected hemisphere.

- Convalescent Phase (>3 months): ≥10 Hz rTMS to affected motor cortex.

- Parameters: Follow established safety guidelines for frequency and pulse count [32].

- Course: Typically 10-20 sessions integrated with physical/occupational therapy.

- Paradigm Selection: Choose protocol based on stroke phase [32]:

- Rationale: Aims to rebalance interhemispheric competition by increasing excitability of the affected hemisphere or decreasing inhibition from the unaffected hemisphere [32].

Signaling Pathways and Neurophysiological Mechanisms

The therapeutic effects of TMS protocols are mediated through the induction of complex neuroplastic changes. The diagram below illustrates the primary signaling pathways and neural mechanisms involved.

Diagram 1: Neuroplasticity pathways activated by TMS.

Experimental Workflow for Protocol Comparison

A standardized methodology is essential for the direct comparison of TMS protocols in a research setting. The following workflow outlines a rigorous experimental design for evaluating efficacy in TRD.

Diagram 2: Workflow for comparative TMS trials.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Materials and Equipment for TMS Research

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TMS Device with TBS Capability | Core stimulation delivery | Must support conventional rTMS and TBS patterns (iTBS, cTBS) [31] [29]. |

| Neuronavigation System | Precision targeting via individual anatomy/connectivity | Integrates structural MRI (sMRI) or functional MRI (fMRI) for personalized coil placement [28] [29]. |

| MRI-Compatible EEG Cap | Concurrent TMS-EEG for mechanism investigation | Assesses immediate electrophysiological effects and cortical excitability [28]. |

| Structural MRI (sMRI) | Anatomical guidance & target identification | Used for targeting BA9/BA46 border [28]. |

| Resting-State fMRI | Functional connectivity mapping for target personalization | Identifies DLPFC subregion with optimal anticorrelation to sgACC [28] [29]. |

| Clinical Rating Scales | Primary outcome measurement for depression trials | HDRS, MADRS; essential for standardized efficacy assessment [28] [29]. |

| Motor Threshold Kit | Individualized stimulation intensity calibration | EMG system for measuring motor evoked potentials (MEPs) [33]. |

| Remdesivir-d4 | Remdesivir-d4, MF:C27H35N6O8P, MW:606.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Top1 inhibitor 1 | Top1 inhibitor 1, MF:C24H22N6O2, MW:426.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative analysis of rTMS, TBS, and Deep TMS reveals a nuanced landscape where no single protocol is universally superior. While standard 10 Hz rTMS and iTBS demonstrate comparable efficacy for TRD, their selection hinges on clinical context, with iTBS offering significant time efficiency [31]. The emergence of accelerated, connectivity-guided iTBS protocols promises enhanced remission rates, though these findings require validation in larger, independent trials [29]. Future research must prioritize the optimization of stimulation parameters, the development of reproducible personalized targeting methods, and the clarification of long-term outcomes and cost-effectiveness to solidify the role of each protocol in the next generation of neuromodulation therapies.

A Generalized Workflow for fMRI-Guided, Electric-Field-Optimized TMS Targeting

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) represents a cornerstone of non-invasive neuromodulation, yet its clinical efficacy has been limited by historical standardization in targeting approaches. The conventional reliance on scalp-based measurement systems, such as the Beam F3 method, fails to account for profound inter-individual variability in brain anatomy and functional network organization [34] [35]. This "one target for all" paradigm results in poorly defined TMS-induced electric field (E-field) intensity and uncertain engagement of the intended neurocircuitry, particularly for cortical targets beyond the primary motor cortex [8]. Consequently, the optimization of TMS protocols now demands a precision medicine framework that integrates individual functional neuroanatomy with computational modeling of induced electric fields.

The convergence of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electric field (E-field) modeling technologies has enabled a new generation of personalized TMS targeting. fMRI provides a non-invasive window into the intrinsic functional architecture of an individual's brain, allowing for the identification of patient-specific network nodes implicated in disease pathophysiology [34] [36]. When combined with computational approaches that simulate the TMS-induced E-field distribution, clinicians and researchers can now optimize coil placement and orientation to maximize the electric field strength in the target region while minimizing off-target stimulation [37]. This integrated methodology is particularly crucial for engaging deeply embedded structures, such as the subgenual cingulate cortex (SGC), through their functional connections with superficial cortical areas like the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) [38] [39].

This protocol outlines a generalized workflow for integrating resting-state fMRI with electric field modeling to optimize TMS targeting, a approach with demonstrated efficacy in neuropsychiatric disorders. Naturalistic clinical data reveals that fMRI-guided targeting significantly improves outcomes in treatment-resistant depression, with response rates increasing from 62.2% with standard targeting to 77.5% with fMRI guidance (Number Needed to Treat = 6.5) [35]. Furthermore, studies quantifying E-field distributions confirm that functional targeting combined with coil orientation optimization produces significantly higher field intensity in the target region compared to anatomical approaches [37]. The following sections provide a comprehensive technical framework for implementing this precision targeting approach in both research and clinical settings.

The generalized workflow for fMRI-guided, E-field-optimized TMS comprises five integrated stages: (1) Neuroimaging Acquisition, (2) Target Identification, (3) Electric Field Modeling, (4) Neuronavigation, and (5) Treatment Delivery. This systematic approach transforms raw imaging data into a personalized stimulation protocol that maximizes target engagement while accounting for individual neuroanatomical variations.

Table 1: Key Stages in fMRI-Guided E-Field-Optimized TMS Workflow

| Stage | Primary Inputs | Core Processes | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Neuroimaging Acquisition | Participant anatomy | T1-weighted MRI, resting-state fMRI, DTI (optional) | Anatomical volumes, BOLD time series, fiber tracts |

| 2. Target Identification | Processed fMRI data | Seed-based connectivity analysis (e.g., SGC as seed) | Personalized DLPFC target based on maximal anti-correlation with SGC |

| 3. Electric Field Modeling | T1 MRI, target coordinates | Finite Element Method (FEM) simulation, coil placement optimization | E-field magnitude and distribution, optimal coil orientation |

| 4. Neuronavigation | Target coordinates, T1 MRI, participant registration | MRI-to-head co-registration, real-time tracking | Real-time coil positioning guidance |

| 5. Treatment Delivery | Optimized protocol | iTBS/rTMS application, clinical monitoring | Applied stimulation, clinical outcomes, adverse event documentation |

Figure 1. Generalized Workflow for Precision TMS. This integrated pipeline transforms multi-modal neuroimaging data into an optimized, personalized TMS protocol. The process begins with data acquisition, progresses through computational target identification and electric field optimization, and culminates in precisely navigated treatment delivery with outcome assessment.

Quantitative Data and Comparative Efficacy

The implementation of fMRI-guided, E-field-optimized TMS protocols has yielded substantial improvements in both targeting precision and clinical outcomes. Quantitative analyses demonstrate the superiority of this integrated approach over conventional methods across multiple domains, from electric field characteristics to real-world clinical response rates.

Table 2: Electric Field Characteristics Across Targeting Methods in DLPFC Stimulation

| Targeting Method | E-Field Magnitude (V/m) in Functional Target | E-Field Magnitude (V/m) in Anatomical Target | Spatial Dispersion | Optimal Coil Orientation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Targeting | 102.5 ± 18.3 | 78.4 ± 15.7 | Greater | Parallel to LOI (P < 0.001) |

| Anatomical Targeting | 85.7 ± 16.2 | 95.1 ± 19.5 | Lesser | Less critical |

| Statistical Significance | P < 0.001 | P < 0.01 | P < 0.05 | Directionally specific |

Electric field modeling reveals critical differences between targeting approaches. When the coil is positioned over the functionally defined target, the E-field magnitude is significantly higher in the functional target compared to adjacent anatomical regions [37]. This effect exhibits directional specificity, with parallel alignment to the local cortical orientation producing maximal field intensity (P < 0.001), while perpendicular orientation maintains functional stability with reduced anatomical interference [37]. These findings establish coil orientation optimization as a critical strategy for enhancing TMS precision.

Table 3: Clinical Outcomes of fMRI-Guided Versus Standard TMS for Depression

| Outcome Measure | fMRI-Guided aTMS (n=115) | Beam F3 Targeting (n=80) | Statistical Significance | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response Rate | 77.5% | 62.2% | P = 0.035 | OR = 2.30 |

| Remission Rate | 51.8% (overall sample) | 51.8% (overall sample) | Not reported | N/A |

| Number Needed to Treat | 6.5 | - | - | - |

| Patients with >5 Medication Failures | Lower response | Lower response | P = 0.038 (predictor) | - |

Naturalistic clinical data from 195 patients with treatment-resistant depression demonstrates the significant advantage of fMRI-guided accelerated TMS (aTMS) over standard scalp-based targeting [35]. After propensity score matching to control for baseline characteristics, the fMRI-guided group showed significantly higher response rates (77.5% vs. 62.2%, P = 0.035), with an odds ratio of 2.30 [35]. Multivariate logistic regression identified fMRI guidance as the only independent predictor of treatment response, highlighting its critical role in optimizing outcomes [35].

Experimental Protocols

Neuroimaging Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Purpose: To acquire high-quality structural and functional MRI data for personalized target identification and E-field modeling.

Materials and Equipment:

- 3T MRI scanner with minimum 45 mT/m gradient strength

- 32-channel or higher head coil

- T1-weighted MPRAGE sequence (1mm isotropic resolution)

- T2*-weighted BOLD fMRI (3.5×3.5×4mm or higher resolution, TR=2000ms, 20+ minutes resting-state)

- Diffusion MRI (optional; 2mm isotropic, 64+ directions, b=1000 s/mm²)

Procedure:

- Structural Acquisition: Obtain T1-weighted anatomical images using a sagittal 3D MPRAGE sequence (FOV=256mm, matrix=256×256, slice thickness=1mm, no gap).

- Functional Acquisition: Acquire resting-state fMRI data with participants instructed to keep their eyes open, fixate on a crosshair, and remain awake. Implement real-time prospective motion correction.

- Data Preprocessing:

- Spatial Alignment: Coregister functional and structural images using SPM12 or FSL.

- Atlas Registration: Normalize images to standard MNI space using nonlinear transformation.

- Motion Censoring: Apply ART-based scrubbing with framewise displacement threshold of 0.5mm.

- Nuisance Regression: Implement global signal regression and bandpass temporal filtering (0.009-0.08 Hz).

- Spatial Smoothing: Apply 6mm FWHM Gaussian kernel.

Quality Control:

- Verify minimal head motion (<2mm translation, <2° rotation)

- Confirm adequate signal-to-noise ratio in prefrontal regions

- Ensure successful normalization to template space

Connectivity-Based Target Identification

Purpose: To identify the personalized DLPFC target exhibiting strongest anti-correlation with the subgenual cingulate cortex (SGC).

Materials and Software:

- Preprocessed fMRI data

- CONN toolbox or similar connectivity analysis package

- SGC seed region mask (default mask in CONN)

- Custom scripts for peak identification

Procedure:

- Seed Definition: Extract the BOLD time series from the SGC seed region (MNI coordinates: x=±4, y=26, z=-10).

- Voxel-wise Connectivity: Compute Pearson correlation coefficients between the SGC time series and all gray matter voxels in the prefrontal cortex.

- Connectivity Map Generation: Convert correlation coefficients to z-scores using Fisher transformation.

- Target Identification: Identify the voxel or cluster within the left DLPFC showing the strongest negative correlation (anti-correlation) with the SGC.

- Target Refinement: Apply manual review considering cluster size, anticipated tolerability, and accessibility with TMS coil placement.

Validation:

- Verify target location within Brodmann areas 9/46

- Confirm statistically significant anti-correlation (P < 0.05, FDR-corrected)

- Document target coordinates in both MNI and native space

Electric Field Modeling and Coil Optimization

Purpose: To simulate TMS-induced electric fields and optimize coil placement and orientation for maximal target engagement.

Materials and Software:

- T1-weighted anatomical in native space

- Target coordinates in native space

- SimNIBS software package (v4.0+)

- Figure-8 coil model (e.g., MagVenture MC-B70)

Procedure:

- Head Model Generation:

- Segment T1 image into five tissue types: skin, skull, CSF, gray matter, white matter

- Generate tetrahedral head mesh with approximately 3 million elements

Coil Placement:

- Position coil center over target coordinate

- Orient coil handle posteriorly at 45° from midline as starting position

Electric Field Simulation:

- Apply 100% stimulator output as input parameter

- Solve Maxwell's equations using finite element method

- Calculate E-field magnitude (Eₙᵣₘₛ) and normal component (E⊥)

Coil Optimization:

- Systematically vary coil orientation in 15° increments

- Identify orientation producing maximal E-field magnitude in target

- Calculate E-field ratio between target and adjacent regions

Validation:

- Confirm maximal E-field magnitude at target coordinates

- Verify acceptable E-field distribution (≤150 V/m in non-target regions)

- Document optimal coil orientation and expected target engagement

Neuronavigation and Treatment Delivery

Purpose: To precisely deliver TMS stimulation to the personalized target using real-time neuronavigation.

Materials and Equipment:

- Neuronavigation system (e.g., Localite TMS Navigator)

- Tracking markers and stereotactic camera

- TMS stimulator with figure-8 coil

- Optimized stimulation parameters

Procedure:

- System Calibration:

- Calibrate tracking system according to manufacturer specifications

- Register subject's head to MRI coordinates using facial landmarks

- Verify registration accuracy (<3mm error)

Coil Positioning:

- Position coil over target using neuronavigation guidance

- Orient coil according to E-field optimization results

- Maintain consistent coil contact and angle throughout session

Stimulation Protocol:

- Apply intermittent theta-burst stimulation (iTBS) protocol: 3-pulse 50Hz bursts repeated at 5Hz, 2s trains, 8s inter-train interval, 600 pulses/session

- Deliver multiple daily sessions (8-10 sessions/day) over 5 days for accelerated protocol

- Stimulation intensity: 90-120% resting motor threshold

Quality Assurance:

- Monitor head motion throughout session

- Recalibrate if movement exceeds 3mm

- Document actual stimulation site for each session

Safety Monitoring:

- Document adverse events (headache, fatigue, anxiety)

- Screen for seizure risk factors

- Implement contingency protocols for treatment-emergent anxiety

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for fMRI-Guided TMS

| Category | Item/Reagent | Specifications | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging Equipment | 3T MRI Scanner | Minimum 45 mT/m gradient, 32-channel head coil | High-resolution structural and functional data acquisition |

| Analysis Software | CONN Toolbox | v20+ with SPM12 integration | Resting-state functional connectivity analysis |

| Electric Field Modeling | SimNIBS | v4.0+ with headreco pipeline | Personalized E-field simulation and coil optimization |

| Neuronavigation | Localite TMS Navigator | Infrared tracking, MRI integration | Real-time coil positioning and target engagement verification |

| Stimulation Equipment | Figure-8 Coil | 70-75mm diameter, liquid-cooled | Focal TMS stimulation with precise field containment |

| Clinical Assessment | CGI-I Scale | 7-point clinician-rated instrument | Primary outcome measurement for treatment response |

| Computational Resources | High-Performance Workstation | 64GB RAM, GPU acceleration | Processing of neuroimaging data and E-field simulations |

| Dienogest-d6 | Dienogest-d6, MF:C20H25NO2, MW:317.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| L-Glutamine-15N2,d5 | L-Glutamine-15N2,d5, MF:C5H10N2O3, MW:153.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Figure 2. Mechanism of Action for Depression Treatment. This schematic illustrates the neurobiological rationale for targeting the DLPFC-SGC circuit in depression treatment. The model emphasizes how aberrant network connectivity manifests as depressive symptoms and how targeted stimulation induces network-level modulation that produces clinical improvement.

The integration of fMRI-guided targeting with electric field optimization represents a paradigm shift in transcranial magnetic stimulation, moving beyond standardized approaches toward truly personalized neuromodulation. The generalized workflow presented here provides a comprehensive framework for implementing this precision medicine approach, with robust empirical support demonstrating significantly enhanced clinical outcomes [35] and superior target engagement [37]. This methodology transforms TMS from a region-based to a circuit-based treatment, directly addressing the network-level pathophysiology underlying neuropsychiatric disorders.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on real-time closed-loop optimization, combining fMRI guidance with electrophysiological biomarkers to dynamically adjust stimulation parameters based on instantaneous brain state [36]. Additionally, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches promises to further enhance target identification and outcome prediction [36]. As these technologies mature, fMRI-guided E-field-optimized TMS will establish a new standard for precision in neuromodulation, offering enhanced therapeutic efficacy for treatment-resistant conditions through circuit-specific engagement tailored to the individual's unique functional neuroanatomy.

The Rise of Multi-Locus TMS (mTMS) for Electronic Targeting and Network Modulation

Multi-locus transcranial magnetic stimulation (mTMS) represents a groundbreaking advancement in non-invasive brain stimulation technology that enables electronic targeting of cortical structures without physical coil movement. Unlike conventional TMS systems limited to single-site stimulation through mechanical manipulation, mTMS employs a transducer consisting of multiple overlapping coils whose individual electric fields can be superposed to create a precisely controlled resultant field [40]. This technological innovation allows researchers to stimulate distinct cortical targets with sub-millisecond interstimulus intervals, facilitating the investigation of causal interactions in functional brain networks and enabling more personalized therapeutic interventions for neurological disorders [41].

The fundamental operating principle of mTMS relies on the precise control of relative currents in multiple coils arranged in a spatially specific configuration. By adjusting the amplitude and timing of currents through each coil, the location, orientation, and characteristics of the induced electric field (E-field) maximum can be electronically manipulated within a defined cortical region [40]. This capability for rapid electronic targeting represents a paradigm shift from traditional TMS approaches, overcoming the limitations of mechanical coil movement and enabling novel experimental and therapeutic protocols previously impossible with conventional technology [42].

Technical Specifications and Performance Characteristics

mTMS System Components and Capabilities

The core mTMS system comprises several integrated components: a multi-coil transducer array, specialized power electronics with independent control channels, a field-programmable gate array (FPGA) for precise temporal control, and targeting software incorporating electric field optimization algorithms [40] [43]. Modern mTMS systems typically feature 5-6 independently controlled coil channels, each driven by its own H-bridge circuit and pulse capacitor, enabling true parallel control of stimulation parameters across all coils [40] [42].

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Representative mTMS Systems

| Parameter | 5-Coil mTMS System | Clinical mTMS Device | Preclinical 2-Coil Array |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Coils | 5 (oval, figure-of-eight, four-leaf-clover) | 5 | 2 |

| Targeting Area | ~30 mm diameter cortical region [40] | Similar to 5-coil system [42] | Smaller, predefined regions |

| Interstimulus Intervals | Sub-millisecond capability [40] | Millisecond-range [42] | Protocol-dependent |

| Control Electronics | Independent H-bridge circuits [40] | Enhanced safety features [42] | MRI-compatible [43] |

| Key Applications | Motor mapping, network interactions [40] | Clinical diagnostics, therapeutic protocols [42] | Simultaneous fMRI studies [43] |

Targeting Precision and Electric Field Control