Optimizing BCI System Performance: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers and Clinicians

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and healthcare professionals aiming to optimize Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) systems for clinical and research applications.

Optimizing BCI System Performance: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers and Clinicians

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers and healthcare professionals aiming to optimize Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) systems for clinical and research applications. It explores the foundational principles of both invasive and non-invasive neural signal acquisition, detailing the latest methodological advances in signal processing and machine learning. The content delves into practical strategies for troubleshooting common performance issues, enhancing signal-to-noise ratio, and improving user adaptation. Furthermore, it offers a critical analysis of validation frameworks and comparative performance metrics essential for evaluating BCI technologies. By synthesizing cutting-edge research and current market trends, this guide aims to bridge the gap between technical development and practical, patient-centric biomedical application.

Demystifying BCI Foundations: From Neural Signals to System Architecture

The signal acquisition module is the foundational component of any Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) system, bearing the critical responsibility for the detection and recording of cerebral signals [1]. The efficacy of the entire BCI system is largely contingent upon the progress in these initial signal acquisition methodologies [1]. This pipeline serves as the primary gateway for capturing neural data, which subsequent processing, decoding, and output components rely upon. In the context of BCI system performance optimization research, ensuring the integrity of this first stage is paramount, as any degradation or artifact introduced here propagates through the entire system, compromising control accuracy and reliability.

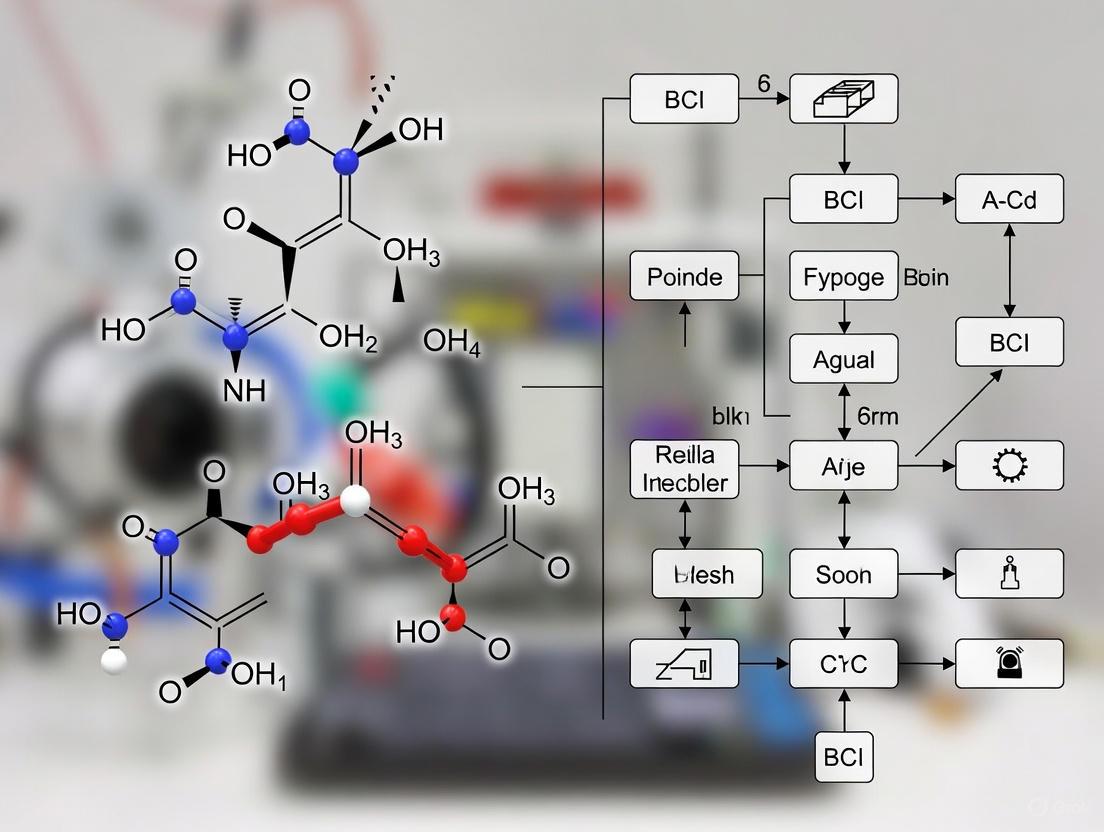

The Core Stages of the BCI Signal Acquisition Pipeline

A BCI system operates via a closed-loop design, and the signal acquisition pipeline forms the first critical segment of this loop [2] [3]. The journey from neural activity to a digitized signal ready for processing involves several distinct stages, each with its own technical considerations and potential failure points. The following diagram illustrates the complete pathway and the key troubleshooting checkpoints, which are detailed in Section 4.

A Two-Dimensional Framework for BCI Acquisition Technologies

When selecting a signal acquisition technology, researchers must navigate a complex trade-space. A modern, comprehensive framework classifies these technologies along two independent dimensions: the surgical procedure's invasiveness and the sensor's operating location [1].

- Surgery Dimension (Invasiveness of Procedures): This perspective, crucial for clinical feasibility and ethical considerations, classifies procedures based on the anatomical trauma caused [1].

- Detection Dimension (Operating Location of Sensors): This engineering-focused dimension is directly linked to the theoretical upper limit of signal quality and biocompatibility risk. It classifies technologies based on the sensor's physical location during operation [1].

The table below summarizes this two-dimensional framework, outlining the characteristics, examples, and inherent trade-offs of each category.

Table 1: Two-Dimensional Classification of BCI Signal Acquisition Technologies

| Category | Key Characteristics | Example Technologies | Signal Quality & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Invasive / Non-Implantation | No anatomical trauma; sensors on body surface [1]. | Electroencephalography (EEG), functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS), Magnetoencephalography (MEG) [4]. | Lower signal quality; suitable for neurorehabilitation, communication, and basic device control [4]. |

| Minimal-Invasive / Intervention | Minor trauma, avoids brain tissue; leverages natural cavities [1]. | Stentrode (Synchron) - deployed via blood vessels [2]. | Moderate to high signal quality; target applications include computer control for paralysis [2]. |

| Invasive / Implantation | Anatomical trauma to brain tissue; sensors implanted [1]. | Utah Array (Blackrock), Neuralink, Precision Neuroscience's Layer 7 [2]. | High-fidelity signals; enables complex control of prosthetics, robotic arms, and speech decoding [2] [4]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Signal Acquisition Issues & Solutions

Even with a well-designed setup, signal acquisition problems are common. This section provides a structured FAQ to diagnose and resolve frequent issues, directly supporting research reproducibility and system optimization.

FAQ 1: Why are the waveforms identical across all my data channels?

- Problem: A common issue where time-series graphs show nearly identical noise patterns on multiple or all channels [5].

- Diagnosis: This typically indicates a problem with a shared component across channels, most commonly the reference or ground electrode [5]. The SRB2 pin on the Cyton board, which acts as a common reference, is a primary suspect.

- Solutions:

- Check Reference & Ground Connections: Verify that the SRB2 pins are correctly connected using a y-splitter cable to an earclip electrode. Ensure the BIAS pin is also properly connected to its earclip [5].

- Swap or Replace Ear Clips: The reference ear clip itself might be faulty. Try replacing it with a new one [5].

- Verify Hardware Settings: In the acquisition software's hardware settings, confirm that the SRB2 is set to ON for all required channels [5].

- Isolate the Board: Test the acquisition board (e.g., Cyton) with a simple setup, such as using conductive paste and a single channel, to rule out a fault in the headset or wiring [5].

FAQ 2: How can I reduce persistent high-amplitude environmental noise?

- Problem: Recordings show noise with amplitudes that are abnormally high (e.g., nearing 1000 µV, whereas normal EEG is generally below 100 µV) [5].

- Diagnosis: This is frequently caused by environmental electromagnetic interference (EMI) or poor electrode contact.

- Solutions:

- Mitigate Power Line Interference:

- Unplug your laptop from its power adapter and run on battery [5].

- Use a fully charged battery (under 6V) for the BCI system itself [5].

- Increase the distance between the subject, the computer, and other electronic equipment [5].

- Toggle on the digital notch filters (e.g., 50/60 Hz) built into the acquisition software [5].

- Improve Electrode-Skin Contact:

- Ensure electrode impedances are checked and are as low as possible. Values below 200 kΩ are often recommended for good quality EEG [5].

- Re-prep and clean the scalp application sites. Use fresh conductive gel if applicable.

- Use a USB Hub: Plug the BCI dongle into a powered USB hub rather than directly into the computer's port to reduce ground loop noise [5].

- Mitigate Power Line Interference:

FAQ 3: What does a "railed" channel indicate, and how do I fix it?

- Problem: A channel is described as "railed," meaning the signal is hitting the maximum or minimum voltage limit of the analog-to-digital converter (ADC).

- Diagnosis: The signal's voltage range exceeds the vertical scale set for the channel. This can be caused by a poor connection at that specific electrode (creating a very high impedance contact) or a hardware fault [5].

- Solutions:

- Check the Specific Electrode: Ensure the electrode for the railed channel is properly connected, screwed in tightly, and making good contact with the scalp [5].

- Inspect for Broken Wires: Examine the cable and electrode mount for that specific channel for any signs of damage or broken wires [5].

- Verify Hardware Integrity: If a single channel is consistently railed across different setups and electrodes, the hardware for that specific channel on the board may be faulty [5].

FAQ 4: How can I address intermittent data streaming or packet loss errors?

- Problem: Data streaming halts unexpectedly with "data streaming error" messages or warnings about packet loss [5].

- Diagnosis: This is often related to communication issues between the dongle and the board, or high CPU load on the host computer.

- Solutions:

- Use a USB Extension Cable: Drape the dongle and its cord over a monitor to get it away from potential interference on the desk or laptop [5].

- Close Unnecessary Applications: Ensure no other resource-intensive programs (e.g., web browsers with multiple tabs) are running during data acquisition [5].

- Check Battery Level: A low battery in the BCI headset can cause intermittent operation. Use a fully charged battery [5].

- Adjust Software Parameters: Increasing the

SampleBlockSizeparameter can reduce the system update rate and potentially stabilize streaming [6].

Table 2: Quick-Reference Troubleshooting Matrix

| Symptom | Most Likely Causes | Immediate Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Identical waveforms on all channels [5] | Faulty reference/ground electrode or connection. | Check SRB2 and BIAS earclip connections; swap earclips. |

| High-amplitude noise (~1000 µV) [5] | Environmental EMI; poor electrode contact. | Unplug laptop power; increase distance from electronics; check impedances. |

| 'Railed' channel [5] | Poor contact on specific channel; broken wire. | Check electrode connection and wire for the affected channel. |

| Intermittent data streaming [5] | Wireless interference; low battery; high CPU load. | Use USB extension; charge battery; close other apps. |

| Poor impedance on a channel | Electrode not making contact; dried gel. | Re-adjust electrode; re-apply conductive gel if used. |

Advanced Methodologies: Enhancing Reliability in Research

For researchers aiming to optimize BCI performance, especially in noisy real-world environments, advanced computational techniques are being developed. These methodologies focus on creating more robust signal representations.

Experimental Protocol: Mixture-of-Graphs-Driven Information Fusion (MGIF) Framework

- Objective: To enhance BCI system robustness against environmental noise and interference by integrating multi-graph knowledge for stable Electroencephalography (EEG) representations [7].

- Methodology:

- Multi-Graph Construction: The framework begins by constructing complementary graph architectures. An electrode-based structure captures spatial relationships between electrodes, while a signal-based structure models inter-channel dependencies in the EEG data [7].

- Spectral Encoding: Filter bank-driven multi-graph constructions are employed to encode spectral information from different frequency bands, which is crucial for paradigms like SSVEP or motor imagery [7].

- Knowledge Fusion: A self-play-driven fusion strategy is used to optimize the combination of embeddings from the different graphs, leveraging their complementary strengths [7].

- Adaptive Gating: An adaptive gating mechanism monitors electrode states in real-time, enabling selective information fusion. This minimizes the impact of unreliable electrodes that may be suffering from artifacts or poor contact [7].

- Outcome: Extensive offline and online evaluations validate that the MGIF framework achieves significant improvements in BCI reliability and classification accuracy across challenging environments [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Equipment for BCI Signal Acquisition Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| EEG Amplifier & Board | Amplifies microvolt-level brain signals for acquisition. | OpenBCI Cyton (with Daisy for more channels), g.USBamp. Critical for signal integrity [5] [6]. |

| Electrode Type | Transduces ionic current in the brain to electrical current in the system. | Wet (Ag/AgCl), Dry, or Semi-Dry electrodes. Choice impacts impedance, setup time, and comfort [5]. |

| Electrode Cap / Headset | Holds electrodes in standardized positions (10-20 system). | Ultracortex Mark IV (OpenBCI), EASYCAP. Ensures consistent spatial configuration [5]. |

| Conductive Gel/Paste | Reduces impedance between scalp and electrode. | EEG/ECG conductive gel. Essential for wet electrodes; improves signal quality [5]. |

| Reference & Ground Electrodes | Provides a common reference point for all signal measurements. | Typically earclip electrodes. Quality is critical, as faults here affect all channels [5]. |

| Visual Stimulator | Presents visual cues to elicit brain responses (e.g., P300, SSVEP). | LCD/LED monitors with precise timing. Integrated LEDs on a metasurface for SSVEP [8]. |

| Field-Programmable Gate Array (FPGA) | Enables real-time signal processing and fusion of control signals. | Used in space-time-coding metasurface platforms for low-latency, secure BCI communication [8]. |

Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) translate neural activity into commands for external devices, creating direct communication pathways between the brain and computers. The core of any BCI system is its signal acquisition method, which fundamentally divides the technology into two categories: non-invasive and invasive techniques [9]. Non-invasive methods, such as Electroencephalography (EEG), record signals from the scalp without surgical intervention. Invasive techniques, including Electrocorticography (ECoG) and Intracortical Microelectrode Arrays, involve surgical implantation of electrodes directly onto the brain's surface or into the cortical tissue [10] [11]. The choice of modality involves significant trade-offs between signal fidelity, risk, and practical implementation, making the comparative understanding of EEG, ECoG, and intracortical arrays essential for researchers aiming to optimize BCI system performance [2].

Technical Comparison of BCI Modalities

Quantitative Comparison Table

The following table summarizes the key technical characteristics of the three primary BCI signal acquisition modalities.

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Primary BCI Modalities

| Parameter | EEG (Non-invasive) | ECoG (Invasive) | Intracortical Arrays (Invasive) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Low (cm-range) [10] | High (mm-range) [11] | Very High (µm-range) [10] |

| Temporal Resolution | Good (Milliseconds) [12] | Excellent (Milliseconds) [11] | Excellent (Sub-millisecond) [10] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Low [10] | High [11] | Very High [10] |

| Frequency Range | Typically < 90 Hz [10] | Up to several hundred Hz [10] | Up to several kHz (including action potentials) [10] |

| Primary Signal Source | Extracellular currents from pyramidal neurons [10] | Cortical surface potentials (LFPs & EPs) [11] | Extracellular action potentials (APs) & Local Field Potentials (LFPs) [10] |

| Typical Applications | Neurofeedback, P300 spellers, basic motor control [13] [14] | Communication neuroprostheses, advanced motor control [11] | High-dimensional prosthetic control, sensory restoration [10] [2] |

| Key Advantage | Safety, ease of use, low cost [9] | Excellent balance of fidelity and stability [11] | Highest information transfer rate [10] |

| Primary Disadvantage | Low spatial resolution, vulnerable to noise [10] | Requires craniotomy, limited cortical coverage [10] | Highest risk, potential for tissue response & signal degradation [10] |

Signal Characteristics and Information Content

The fundamental differences in signal acquisition location lead to profound variations in the information content available to the BCI.

- EEG Signals are generated primarily by post-synaptic extracellular currents in pyramidal neurons. Because these signals must pass through the cerebrospinal fluid, skull, and scalp, they experience significant spatial distortion and low-pass filtering, which attenuates high-frequency components and buries them in background noise [10]. This limits EEG largely to the analysis of lower frequency brain rhythms (e.g., alpha, beta, gamma) and event-related potentials like the P300 [12] [13].

- ECoG Signals are recorded from the cortical surface, bypassing the skull. This provides a much clearer window into brain activity, capturing both low-frequency dynamics and high-frequency broadband (HFB) activity (>30 Hz). HFB activity is strongly correlated with local neuronal firing and population-level processing, making it a robust feature for BCI control [11].

- Intracortical Signals provide the most direct measure of neural computation. Microelectrodes can record two primary types of signals: Local Field Potentials (LFPs), which reflect the summed synaptic activity of a local neuronal population, and Action Potentials (APs or "spikes"), which are the all-or-nothing firing of individual neurons [10]. This allows for decoding intended movement kinematics with high precision and has enabled control of high-degree-of-freedom robotic prosthetics [10] [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Researchers

1. What is the primary technical trade-off between invasive and non-invasive BCIs? The core trade-off is between signal fidelity and safety/accessibility. Invasive methods (ECoG, Intracortical) offer higher spatial and temporal resolution, providing access to richer neural information essential for complex control tasks. Non-invasive methods (EEG) eliminate surgical risks and are more readily deployable, but their low spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio limit their performance and application scope [10] [9].

2. For a motor imagery BCI, why might ECoG be preferred over EEG for a clinical population? Studies, such as those with locked-in syndrome (LIS) patients, show that ECoG's high-frequency band (HFB) power remains a robust and decodable feature even in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or brain stem stroke. In contrast, the low-frequency band (LFB) oscillations used in EEG-based motor imagery can be significantly affected by the etiology of the brain damage, potentially leading to "BCI illiteracy" where users cannot generate reliable EEG modulations [11] [14].

3. What are the major long-term stability challenges for implanted intracortical arrays? The primary challenge is the foreign body response. Chronic implantation can lead to glial scarring and encapsulation of the electrodes, which insulates them from nearby neurons. This can cause a decline in the amplitude of recorded action potentials and an increase in impedance over time, ultimately degrading signal quality and necessitating complex recalibration or even explantation [10] [2].

4. How can machine learning (ML) mitigate some limitations of non-invasive BCIs? ML and deep learning models, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Transfer Learning, can improve the classification of noisy EEG signals. These algorithms can enhance feature extraction and adapt to the high variability in brain signals across users and sessions, reducing the need for lengthy per-user calibration, which is a significant bottleneck for practical BCI use [3].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Non-Invasive BCI (EEG) Troubleshooting

Problem: Identical, high-amplitude noise present on all EEG channels. This is a classic symptom of a problem with a common reference electrode.

- Step 1: Verify Reference and Ground Connections. Check that the SRB2 (reference) and BIAS (ground) earclip electrodes are firmly attached. Ensure the skin under the electrodes is clean and abraded if necessary to achieve an impedance below 2000 kOhms, though ideally below 1000 kOhms for a stronger signal [5] [15].

- Step 2: Check Hardware Configuration. Confirm that the SRB2 pins on the acquisition board (e.g., OpenBCI Cyton) are properly ganged together using a Y-splitter cable, with the single end connected to the reference earclip [5].

- Step 3: Reduce Environmental Noise.

- Unplug your laptop from its power adapter.

- Use a USB hub to move the Bluetooth dongle away from the computer.

- Sit away from monitors, power cables, and fluorescent lights.

- Ensure all electrodes have good scalp contact [5].

Problem: Low P300 Speller accuracy in a pilot study. This can be caused by user state, experimental setup, or signal processing issues.

- Step 1: Consider Participant Factors. Accuracy in P300 systems is known to be inversely correlated with age, likely due to declines in concentration and visual processing. Adjust task difficulty or use a different BCI paradigm for older subjects [13].

- Step 2: Optimize the Stimulus Paradigm. Ensure the stimulus (e.g., flashing) is salient and the timing (e.g., inter-stimulus interval) is appropriate. A very fast or very slow paradigm can reduce the P300 amplitude.

- Step 3: Verify Classifier Training. Ensure the classifier is trained on a sufficient amount of task-specific data. Use a standardized word or sequence for calibration (e.g., "THE QUICK BROWN FOX") before testing with target words [13].

Invasive BCI (ECoG/Intracortical) Experimental Considerations

Problem: Signal drift or degradation over weeks in a chronic implant study. This is a common challenge in long-term invasive BCI research.

- Step 1: Distinguish Biological from Technical Drift. Determine if the change is due to biological encapsulation (a slow, gradual change) or a technical fault (a sudden change). Monitor electrode impedance and noise floors regularly.

- Step 2: Implement Adaptive Decoding. Use machine learning models that can adapt to slow changes in the neural signal properties. Regularly update the decoder's parameters using recent data to maintain performance despite signal drift [10] [3].

- Step 3: Leverage Stable Signal Features. Research indicates that Local Field Potentials (LFPs) may be more stable over time than single-unit action potentials. If spike signals degrade, consider switching a control algorithm to use LFP features, such as high-frequency band power, which can still provide excellent control [10].

Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials and Solutions for BCI Experimentation

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| OpenBCI Ultracortex Mark IV | 3D-printable, modular headset for holding EEG electrodes. | Allows for customizable electrode positioning according to the 10-20 system. The frame should be sized based on head circumference (S: 42-50cm, M: 48-58cm, L: 58-65cm) [12]. |

| Active Dry Electrodes (e.g., ThinkPulse) | Capture brain signals without conductive gel. | Ideal for repeated home or lab use. More susceptible to noise than wet electrodes; ensure excellent scalp contact [12]. |

| PiEEG Board | EEG data acquisition board that interfaces with Raspberry Pi. | An open-source alternative for real-time EEG signal acquisition, supporting 8 or 16 channels [12]. |

| Conductive "10-20" Paste | Improves electrical connection between electrode and skin. | Critical for reducing impedance and obtaining clean EEG and EKG signals. Apply as a small mound between the electrode and skin [15]. |

| Utah Array (Blackrock Neurotech) | A common intracortical microelectrode array. | A bed-of-nails style implant with multiple electrodes; used in many foundational BCI studies. Can cause scarring over time [2]. |

| Stentrode (Synchron) | An endovascular ECoG electrode array. | Minimally invasive device delivered via blood vessels; rests in the superior sagittal sinus against the motor cortex, avoiding open-brain surgery [2]. |

Experimental Protocol: Sensorimotor Rhythm Modulation for BCI Control

This protocol outlines a procedure for detecting event-related desynchronization (ERD) in the mu/beta rhythms during motor imagery, a common paradigm for both EEG and ECoG-based BCIs.

Objective: To train a BCI system to detect changes in sensorimotor rhythm power associated with imagined hand movement.

Background: The sensorimotor cortex displays a decrease in power in the mu (8-12 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) frequency bands during actual or imagined movement. This phenomenon, known as ERD, can be used as a control signal for a BCI [11].

Materials:

- Signal acquisition system (EEG, ECoG, or intracortical array).

- Electrodes positioned over the hand-knob area of the sensorimotor cortex (e.g., C3/C4 in the 10-20 system for EEG).

- A visual cueing system (e.g., a computer monitor).

- Signal processing software (e.g., BCI2000, OpenBCI GUI, or custom MATLAB/Python scripts).

Procedure:

- Setup and Calibration: Position the participant in front of the monitor. For EEG, ensure all electrode impedances are below a predefined threshold (e.g., 50 kΩ). Record a 2-minute baseline with the participant at rest, eyes open.

- Paradigm Design: Implement a cue-based trial structure. Each trial should consist of:

- A fixation period (2-3 s): A crosshair appears to focus attention.

- A cue period (3-4 s): An arrow appears, instructing the participant to imagine opening and closing the cued hand (e.g., right hand for a right arrow). The participant should kinesthetically imagine the movement without executing it.

- A rest period (4-5 s): The screen blanks, and the participant relaxes.

- Data Acquisition: Run a session of at least 100 trials (50 per hand). Record the continuous neural data along with event markers for the start of each cue and rest period.

- Signal Processing and Feature Extraction:

- Filtering: Bandpass filter the data to isolate the mu (8-12 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) rhythms.

- Feature Calculation: For each channel of interest, calculate the log-power of the filtered signals in short, overlapping time windows (e.g., 100 ms windows).

- ERD Calculation: Normalize the power during the cue period against the average power from the baseline or fixation period. ERD is manifested as a significant decrease in this normalized power.

The following diagram illustrates the signal processing workflow for this protocol.

Diagram 1: Signal processing workflow for sensorimotor BCI.

The selection of a BCI modality is a foundational decision that dictates the system's potential performance, application suitability, and development pathway. Non-invasive EEG offers a safe and accessible entry point for communication and basic neurofeedback applications. In contrast, invasive techniques, ECoG and intracortical arrays, provide the high-fidelity signals necessary for complex, dexterous control and are the focus of cutting-edge clinical trials aimed at restoring function to individuals with severe paralysis [2]. Future optimization of BCI systems will rely on hybrid approaches, advanced machine learning to overcome signal limitations, and continued innovation in electrode materials and design to enhance the stability and biocompatibility of invasive interfaces [10] [3]. Understanding these core technologies empowers researchers to select the appropriate tool for their specific experimental or clinical objectives.

The performance of a Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) system is fundamentally governed by three core technical benchmarks: spatial resolution, temporal resolution, and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). These parameters determine the system's ability to accurately interpret neural signals and translate them into reliable control commands. Spatial resolution refers to the ability to distinguish between distinct neural activity sources, typically measured in millimeters. Temporal resolution indicates how precisely a system can track changes in neural activity over time, measured in milliseconds or seconds. SNR quantifies the strength of the desired neural signal relative to background noise, which is crucial for detecting subtle neural patterns amid biological and environmental interference [16] [17] [18].

Understanding the inherent trade-offs between these metrics is essential for BCI system selection and optimization. No single neuroimaging modality excels in all three domains simultaneously. For instance, non-invasive approaches like electroencephalography (EEG) offer excellent temporal resolution but suffer from limited spatial resolution due to signal dispersion through the skull and other tissues. In contrast, invasive methods provide superior spatial resolution and SNR but require surgical implantation and carry medical risks [17] [18]. These performance characteristics directly influence which BCI applications are feasible, from high-speed communication systems requiring millisecond precision to neuroprosthetics demanding precise spatial localization of motor commands.

Comparative Analysis of BCI Modalities

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Major BCI Signal Acquisition Technologies

| Modality | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Invasiveness | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEG | ~10 mm [17] | ~0.05 s (50 ms) [17] | Low [19] [20] | Non-invasive | Research, neurofeedback, assistive technology [21] [16] |

| MEG | ~5 mm [17] | ~0.05 s (50 ms) [17] | Moderate (in shielded environments) | Non-invasive | Cognitive research, clinical diagnostics |

| fNIRS | ~5 mm [22] | ~1 s [17] | Low to Moderate [22] | Non-invasive | Neurorehabilitation, cognitive monitoring [19] [22] |

| fMRI | ~1 mm [17] | ~1 s [17] | High (in controlled settings) | Non-invasive | Brain mapping, research tool |

| ECoG | ~1 mm [17] | ~0.003 s (3 ms) [17] | High [17] | Invasive (subdural) | Epilepsy monitoring, advanced BCI prototypes |

| Intracortical Recording | 0.05-0.5 mm [17] | ~0.003 s (3 ms) [17] | Very High [17] [23] | Invasive (intracranial) | High-performance neuroprosthetics, fundamental research |

Table 2: Signal Characteristics and Practical Implementation Factors

| Modality | Signal Type | Portability | Setup Complexity | Cost | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEG | Electrical | High [17] | Low to Moderate | Low to Moderate | Low spatial resolution, sensitive to artifacts [16] [20] |

| MEG | Magnetic | Low [17] | High | Very High | Requires magnetically shielded room, expensive [21] |

| fNIRS | Hemodynamic | High [22] | Moderate | Moderate | Slow temporal response, superficial penetration [22] |

| fMRI | Metabolic | Low [17] | Very High | Very High | Immobile, expensive, noisy environment |

| ECoG | Electrical | High [17] | Very High (surgical) | High | Surgical risks, limited coverage |

| Intracortical Recording | Electrical | High [17] | Very High (surgical) | Very High | Surgical risks, long-term stability concerns [17] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How can we improve the low signal-to-noise ratio in our EEG-based motor imagery BCI experiments?

Challenge: EEG signals possess inherently low SNR, as they measure the average activity of large neuron populations with electrodes on the scalp surface. This makes it difficult to distinguish motor imagery patterns from background noise [19] [20].

Solutions:

- Advanced Signal Processing: Implement spatial filtering techniques like Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) or Independent Component Analysis (ICA) to isolate task-relevant neural activity from noise and artifacts [16] [20].

- Dry Electrode Innovations: Consider using modern dry electrodes that provide more durable contact without conductive gel, though they may be more prone to motion artifacts [21] [16].

- Artifact Removal: Develop protocols to identify and remove physiological artifacts (eye blinks, muscle activity) through blind source separation or regression techniques [16] [18].

- Deep Learning Approaches: Utilize convolutional neural networks (CNNs) like EEGNet that can automatically learn hierarchical representations from raw signals and recognize nuances in noninvasive brain signals, potentially improving classification accuracy despite low SNR [23].

- Hardware Optimization: Ensure proper electrode placement according to the international 10-20 system, check impedance levels, and select appropriate amplifier gains to minimize hardware-induced noise [16] [24].

FAQ 2: What strategies can address the limited spatial resolution of non-invasive BCI systems for precise control applications?

Challenge: Non-invasive modalities like EEG have limited spatial resolution (~10 mm), making it difficult to decode fine-grained neural patterns, such as individual finger movements [17] [23].

Solutions:

- High-Density Arrays: Increase electrode density (64-256 channels) to improve spatial sampling, though this introduces greater computational complexity [18] [23].

- Source Localization: Apply EEG source imaging techniques that use mathematical models to estimate the cortical origins of scalp-recorded potentials, effectively enhancing spatial resolution [23].

- fNIRS Optimization: For hemodynamic-based BCIs, improve spatial specificity through precise optode placement using 3D digitization and anatomical guidance to reliably target specific regions of interest across sessions [22].

- Hybrid Approaches: Combine multiple modalities (e.g., EEG-fNIRS) to leverage complementary strengths—EEG's high temporal resolution with fNIRS's better spatial specificity [21] [17].

- Advanced Decoding Algorithms: Implement deep learning architectures that can learn to discriminate between highly correlated neural patterns from adjacent cortical areas, as demonstrated in recent individual finger decoding research [23].

FAQ 3: Why does our BCI system exhibit performance variability across sessions and subjects, and how can we mitigate this?

Challenge: EEG signals show high inter-subject and inter-session variability due to their non-stationary nature, anatomical differences, and changing mental states, requiring frequent system recalibration [19] [20].

Solutions:

- Transfer Learning: Employ domain adaptation techniques that leverage data from multiple subjects to reduce calibration time for new users [19] [20].

- Adaptive Classification: Implement algorithms that continuously update classifier parameters during online operation to track non-stationarities in the signal [18].

- Standardized Protocols: Develop and consistently follow experimental protocols for electrode placement, impedance checking, and task instructions to minimize procedural variability [16] [22].

- Data Augmentation: Use techniques like window warping, segmentation and recombination, or adding Gaussian noise to artificially expand training datasets and improve model generalization [20].

- Fine-Tuning Approach: As demonstrated in recent robotic hand control studies, start with a base model trained on group data, then fine-tune with a small amount of subject-specific data to achieve optimal performance while maintaining efficiency [23].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmark Validation

Protocol 1: Assessing Temporal Resolution through Motor Imagery Paradigms

Objective: Quantify the temporal resolution of a BCI system by measuring its ability to detect rapid changes in neural activity during motor imagery tasks.

Materials and Setup:

- EEG system with minimum 16 channels focused on sensorimotor areas (C3, Cz, C4)

- Display system for visual cues

- Data acquisition software with real-time processing capabilities

- Robotic hand or visual feedback system [23]

Procedure:

- Place electrodes according to the international 10-20 system, with particular focus on the sensorimotor cortex.

- Instruct the participant to perform cued motor imagery of left hand, right hand, or foot movements in random order.

- Use a trial structure: 2s baseline, 3s cue presentation, 4s motor imagery period, 2s rest.

- Record EEG data throughout the experiment with sampling rate ≥256 Hz.

- Apply temporal filters (e.g., 8-30 Hz bandpass for mu and beta rhythms) to extract relevant frequency components.

- Calculate Event-Related Desynchronization (ERD) and Event-Related Synchronization (ERS) in the mu (8-12 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) bands.

- Measure the system's ability to detect significant ERD/ERS patterns within 500ms of task initiation as an indicator of temporal resolution. [16] [20] [23]

Analysis:

- Compute latency between cue presentation and significant ERD detection across multiple trials.

- Calculate classification accuracy for different temporal window sizes to determine optimal processing intervals.

- Assess information transfer rate (bits per minute) as a comprehensive measure of system efficiency.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Spatial Resolution through Finger Movement Decoding

Objective: Determine the spatial resolution of a BCI system by assessing its capability to discriminate between individual finger movements based on neural signals.

Materials and Setup:

- High-density EEG system (64+ channels) or ECoG array if invasive

- Signal acquisition system with high input impedance and common-mode rejection

- Robotic hand setup for real-time visual feedback [23]

- Deep learning framework (e.g., EEGNet implementation) [23]

Procedure:

- Set up recording equipment with comprehensive coverage of the sensorimotor cortex.

- For non-invasive systems: Use 3D digitization to record precise electrode positions.

- Instruct participants to perform either actual movements or motor imagery of individual fingers (thumb, index, pinky) in response to visual cues.

- Implement a trial structure: 2s rest, 1s pre-cue baseline, 4s movement execution/imagery period.

- Record neural data throughout, ensuring proper artifact monitoring.

- For offline analysis, train a deep learning classifier (e.g., EEGNet) to discriminate between different finger movements.

- For real-time testing, provide continuous visual feedback of decoded finger movements via robotic hand. [23]

Analysis:

- Calculate confusion matrices to assess classification accuracy between different finger pairs.

- Perform source localization to identify cortical regions contributing most to classification.

- Compute spatial discrimination threshold as the minimum cortical distance between activations that the system can reliably distinguish.

Protocol 3: Quantifying Signal-to-Noise Ratio in BCI Systems

Objective: Measure and optimize the SNR of a BCI system to improve overall performance and reliability.

Materials and Setup:

- BCI acquisition system (EEG, fNIRS, or other modality)

- Ground and reference electrodes properly placed

- Impedance checking capability

- Electrically shielded room (if available) [24]

Procedure:

- Set up the acquisition system according to manufacturer guidelines.

- Ensure proper skin preparation and electrode placement to minimize impedance.

- For EEG: Record 2 minutes of resting-state data with eyes open as noise baseline.

- Present controlled stimuli or tasks known to elicit robust neural responses (e.g., motor imagery, visual evoked potentials).

- Collect data across multiple trials (minimum 40 trials per condition).

- Systematically vary acquisition parameters (e.g., filter settings, gain values) to determine optimal configurations.

- For fNIRS systems: Implement short-distance channels to regress out superficial contaminants. [22]

Analysis:

- Calculate SNR as the ratio of task-related signal power to resting-state power in relevant frequency bands.

- Compare SNR across different electrode positions to identify optimal recording sites.

- Assess the relationship between impedance values and SNR measures.

- Evaluate the impact of different preprocessing techniques (filtering, artifact removal) on final SNR.

Signaling Pathways and System Workflows

BCI System Signal Processing Workflow

BCI Modality Trade-offs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Materials and Equipment for BCI Performance Evaluation

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density EEG System (64+ channels) | Records electrical brain activity from scalp surface | Essential for spatial resolution studies; requires proper electrode positioning according to 10-20 system [16] [23] |

| Dry Electrodes | Enables faster setup without conductive gel | Improves practicality but may increase motion artifacts; suitable for rapid prototyping [21] |

| fNIRS Optodes (sources and detectors) | Measures hemodynamic responses via light absorption | Provides better spatial specificity than EEG; optimal for studying cortical specialization [22] |

| ECoG Grid/Strip Electrodes | Records electrical activity from cortical surface | Offers high spatial and temporal resolution for invasive studies; requires surgical implantation [17] |

| Deep Learning Framework (e.g., EEGNet, CNN) | Automated feature extraction and classification | Handles complex pattern recognition in noisy signals; reduces need for manual feature engineering [20] [23] |

| 3D Digitization System | Records precise sensor positions on head | Critical for spatial accuracy and reproducibility across sessions; enables source localization [22] |

| Robotic Hand/Feedback Device | Provides real-time visual/physical feedback | Essential for closed-loop experiments and motor imagery studies; enhances user learning [23] |

| Signal Processing Library (e.g., MATLAB, Python) | Implements filtering, artifact removal, and analysis | Customizable pipelines for specific research questions; enables algorithm development [16] [20] |

Emerging Solutions and Future Directions

The field of BCI performance optimization is rapidly evolving, with several promising approaches addressing fundamental limitations. Deep learning methods are demonstrating remarkable capabilities in decoding complex neural patterns despite challenging SNR conditions. For instance, recent research has shown that convolutional neural networks like EEGNet can achieve 80.56% accuracy for two-finger motor imagery tasks and 60.61% for three-finger tasks in real-time robotic control applications [23]. These approaches benefit from transfer learning strategies where base models pre-trained on population data are fine-tuned with small amounts of subject-specific data, significantly reducing calibration requirements while maintaining performance [20] [23].

For improving spatial resolution in non-invasive systems, hybrid approaches that combine multiple neuroimaging modalities show particular promise. Integrating EEG's millisecond-scale temporal resolution with fNIRS's centimeter-scale spatial specificity provides complementary information that enhances overall decoding accuracy [21] [17]. Additionally, hardware innovations in electrode design and array density continue to push the boundaries of what non-invasive systems can achieve. The development of high-density arrays with 256+ channels, combined with advanced source localization algorithms, is gradually narrowing the spatial resolution gap between invasive and non-invasive approaches [18] [23].

Future directions in BCI performance optimization point toward adaptive closed-loop systems that continuously monitor signal quality and automatically adjust processing parameters in real-time. Such systems would maintain optimal performance despite changing environmental conditions or user states. Furthermore, the integration of multimodal feedback approaches—combining visual, haptic, and proprioceptive cues—has shown potential for enhancing user learning and improving overall BCI control precision [17] [23]. As these technologies mature, they will enable more robust and practical BCI applications across clinical, research, and consumer domains.

BCI Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting

This technical support center provides essential guidance for researchers and scientists aiming to optimize Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) system performance. The following FAQs address common experimental challenges.

FAQ 1: Why is my BCI system's classification accuracy unacceptably low or seemingly random?

Low BCI accuracy can stem from user-related, acquisition-related, or software-related factors [25].

- User-Related Factors: Inherent physiological variability between users affects signal transmission; different head shapes and cortical volumes act as a strong lowpass filter on the EEG signal [25]. User state is also critical; lack of skill, motivation, or fatigue, especially in paradigms like motor imagery, severely impacts performance [25].

- Acquisition-Related Factors:

- Electrode Conductivity: High impedance at the electrode-skin interface creates noise [25]. Visually inspect the signal for expected artifacts (e.g., eye blinks) and check for a strong alpha component (~10 Hz) in the occipital lobe with eyes closed [5] [25].

- Electrical Interference: 50/60 Hz power line noise and interference from other electronic devices can corrupt signals [25] [26].

- Hardware Issues: A faulty amplifier or poor wireless connection can cause data loss or noise [25].

- Software/DSP Factors: Suboptimal classification parameters or bugs in the processing pipeline can reduce effectiveness. Classifiers often need re-calibration for each user and session due to neural signal non-stationarity [25].

FAQ 2: My EEG data shows identical, high-amplitude noise on all channels. What is the cause?

This pattern typically indicates a problem with a common component shared across all channels, most often the reference or ground electrodes [5].

- Primary Suspects: Loose, broken, or poorly connected reference (SRB) or bias (BIAS) electrodes are the most likely cause [5]. Verify the physical connections and cables for these specific electrodes.

- Environmental Noise: While possible, environmental noise usually doesn't manifest as perfectly identical waveforms on every channel. Nonetheless, ensure your setup is away from power cables, monitors, and other sources of electromagnetic interference [26].

- Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Swap Components: Replace the ear clip electrodes used for reference and ground [5].

- Simplify Setup: Test the system with a single channel using a known-good setup, such as cup electrodes with conductive paste, to isolate the problem [5].

- Change Location: Test the equipment in a different room to rule out environmental factors [5].

- Check Impedance: Use the software's impedance check feature. Values should ideally be low, for example, below 2000 kOhms for a decent reading with some systems, though lower is generally better [5].

FAQ 3: How can I minimize 50/60 Hz AC power line noise and other environmental interference in my recordings?

- Use Software Filters: Engage the built-in software notch filter (50 Hz or 60 Hz, as appropriate for your region) in your acquisition software [26].

- Improve Setup Geometry:

- Use a USB hub or extension cord to move the Bluetooth dongle away from the computer [5] [26].

- Sit slightly away from the computer monitor and avoid proximity to power cords or outlets [26].

- Ensure the subject's body is not blocking the line of sight between the transmitter and receiver for wireless systems [25].

- Secure Electrodes: Movement of electrode cables induces noise. Bind cables together with tape to minimize motion and ensure electrodes are snug against the scalp [26]. Active electrodes can significantly reduce this movement noise.

- Power Management: Use a fully charged battery and, if applicable, unplug the laptop from its power adapter during recordings [5] [26].

FAQ 4: Should I choose an EEG headset with a fixed or customizable electrode montage for my research?

The choice depends on your research phase and objectives [27].

- Fixed Montages are ideal for application-oriented phases where ease of use, consistency, and comfort are priorities. They are best when the relevant brain areas are well-defined and limited in number [27].

- Customizable Montages are essential for exploratory research. They provide the flexibility to cover extensive brain areas, identify neural correlates, and determine the minimal number of sensors required for a specific task [27].

Table 1: Comparison of Fixed vs. Customizable EEG Montages for Research

| Feature | Fixed Montage | Customizable Montage |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use Case | Application-oriented phase, out-of-lab studies | Exploratory research phase, in-lab studies |

| Flexibility | Low; predefined electrode positions | High; interchangeable electrode positions |

| Ease of Use | High; simple and quick setup | Lower; requires expertise and more time |

| Consistency | High across sessions | Requires careful setup for reproducibility |

| Targeting Specific Areas | Limited to pre-defined areas | Excellent; can target any brain region |

| Typical Sensor Count | Lower, covering only essential areas | Higher, with comprehensive head coverage |

The Current BCI Landscape: Major Players and Clinical Progress

The BCI field is rapidly transitioning from laboratory research to clinical trials, driven by significant venture capital investment and technological innovation.

Key Companies and Technologies

Leading companies are pursuing diverse technological approaches, from minimally invasive to high-bandwidth implants [2].

Table 2: Leading BCI Companies, Technologies, and Clinical Status (2025)

| Company | Technology & Approach | Key Differentiator | Clinical Trial Focus & Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuralink | Implantable chip with thousands of micro-electrodes | Ultra-high bandwidth; implanted via robotic surgery | Restoring device control in paralysis; 5 patients in trials as of mid-2025 [2]. |

| Synchron | Stentrode endovascular BCI | Minimally invasive; implanted via blood vessels | Enabling computer control for paralysis; demonstrated safety in 4-patient trial; moving toward pivotal trial [2]. |

| Precision Neuroscience | Layer 7 Cortical Interface | Ultra-thin electrode array placed on brain surface | "Peel and stick" BCI for communication; FDA 510(k) cleared for up to 30-day implantation [2]. |

| Paradromics | Connexus BCI | Modular, high-channel-count implant for fast data | Focus on restoring speech; first-in-human recording in 2025; planning clinical trial for late 2025 [2]. |

| Blackrock Neurotech | Neuralace & Utah array | Long-standing provider of neural electrode arrays | Advancing neural implants for paralyzed patients; conducting in-home daily use tests [2]. |

Funding Trends and Market Outlook

Venture capital funding for BCI technology has seen explosive growth, underscoring strong investor confidence.

- Overall Investment: The global BCI market attracted $2.3 billion in venture capital in 2024, a three-fold increase from 2022 levels [28]. The market size is projected to grow from $2.83 billion in 2025 to $8.73 billion by 2033, at a CAGR of 15.13% [29].

- Landmark Rounds: Neuralink's $650 million Series E round in June 2025 marked the largest single funding event in BCI history [28]. Other significant rounds include Precision Neuroscience's $155 million total funding and Blackrock Neurotech's $200 million round in 2024 [28].

- Geographic Distribution: North America leads with approximately 40% of total funding, followed by Europe. The Asia-Pacific region is experiencing the highest growth rates, fueled by national initiatives and expanding healthcare investment [28] [29].

Table 3: Select Major BCI Funding Rounds (2024-2025)

| Company | Funding Round & Amount | Lead Investors |

|---|---|---|

| Neuralink | $650M Series E (2025) | ARK Invest, Founders Fund, Sequoia Capital [28] |

| Precision Neuroscience | $155M Total Funding | Various Institutional Investors [28] |

| Blackrock Neurotech | $200M (2024) | Tether [28] |

| INBRAIN Neuroelectronics | $50M Series B | imec.xpand [28] |

| Paradromics | $53M Total Funding | Prime Movers Lab [28] |

Experimental Protocols for System Validation

To ensure BCI data quality and system performance, researchers should implement standardized validation protocols.

Protocol: Alpha Wave Localization and System Check

This experiment verifies that the EEG system is correctly capturing brain activity and that electrode impedances are acceptable.

- Setup: Use a research-grade EEG system with at least one electrode placed at the Oz position (occipital lobe) according to the 10-20 international system [27]. The reference and ground should be securely attached, for example, to the ear lobes.

- Procedure:

- Instruct the subject to sit comfortably with eyes open for 30 seconds while recording a baseline.

- Then, instruct the subject to close their eyes and remain relaxed for 60 seconds.

- Repeat the eyes-open (30s) / eyes-closed (60s) cycle 3-5 times.

- Data Analysis:

- Process the data through a bandpass filter (e.g., 8-13 Hz for Alpha waves).

- Compute the power spectral density or FFT for eyes-open and eyes-closed periods.

- Expected Outcome: A clear increase in alpha band (~10 Hz) power in the Oz channel should be observed when the subject's eyes are closed, confirming proper system function [5] [25]. Failure to see this may indicate poor electrode contact or hardware malfunction.

Protocol: Verification of Motor Imagery Signal Acquisition

This protocol is used to validate the setup for motor imagery-based BCI paradigms.

- Setup: Position electrodes over the left and right motor cortices (e.g., C3 and C4 positions). The ground and reference are placed on the ear lobes or mastoids.

- Procedure:

- Instruct the subject to remain relaxed and not perform any movement for 30 seconds (resting baseline).

- Then, instruct the subject to imagine opening and closing their right hand without any actual movement for 45 seconds.

- Return to a rest state for 30 seconds.

- Repeat the sequence for imagination of the left hand.

- Conduct multiple trials (e.g., 20 per class).

- Data Analysis: Use machine learning algorithms (e.g., Common Spatial Patterns followed by a Linear Discriminant Analysis or Support Vector Machine) to classify the two mental states (left vs. right hand imagery).

- Expected Outcome: A classification accuracy significantly above chance (50% for two classes) indicates successful capture of motor imagery signals. This validates the experimental setup and the user's ability to generate controllable signals [25].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key components for a typical invasive BCI research setup, as inferred from leading companies' technologies.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced BCI Development

| Item / Component | Function / Application in BCI Research |

|---|---|

| High-Density Microelectrode Arrays | Core sensing component for invasive BCIs; records neural activity from large populations of neurons. Essential for high-bandwidth applications like speech decoding [2]. |

| Flexible Bioelectronic Interfaces | Thin, conformable electrode arrays that minimize tissue damage and improve long-term signal stability (e.g., Precision Neuroscience's Layer 7, Blackrock's Neuralace) [2]. |

| Graphene-Based Neural Interfaces | Emerging material offering superior biocompatibility and electrical properties compared to traditional metals like platinum or iridium oxide [28]. |

| AI/ML Decoding Models | Software algorithms (e.g., CNNs, SVMs) that translate raw neural signals into intended commands. Critical for achieving high-accuracy control and communication [3]. |

| Minimally Invasive Delivery Systems | Surgical tools or endovascular catheters for implanting BCI devices with reduced risk and trauma (e.g., Synchron's stent delivery system) [2]. |

Workflow and System Diagrams

The following diagrams illustrate core BCI processes and troubleshooting logic using the specified color palette.

BCI Closed-Loop Signal Processing Pipeline

Troubleshooting Logic for Low BCI Accuracy

Advanced Methodologies and Cutting-Edge Applications in Clinical BCI

In Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) research, data preprocessing serves as the foundational stage that significantly influences overall system performance. Electroencephalogram (EEG) signals, the most commonly employed neurophysiological signals in non-invasive BCI systems, possess an inherently low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and are frequently contaminated by various artifacts originating from both external sources and physiological processes [30] [31]. Effective preprocessing enhances signal quality, facilitates more accurate feature extraction, and ultimately improves the classification accuracy and information transfer rate (ITR) of BCI systems [32] [33]. Within the context of BCI system performance optimization research, mastering artifact removal and signal enhancement techniques is not merely a preliminary step but a critical determinant of experimental validity and practical application success. This technical support center provides targeted guidance to address common preprocessing challenges, supported by current methodologies and quantitative comparisons.

Troubleshooting Guides: Addressing Common Preprocessing Challenges

Problem 1: How can I identify and remove physiological artifacts from my EEG data?

Solution: Physiological artifacts constitute the most common and challenging contaminants in EEG data. The table below summarizes the primary artifact types and recommended removal techniques.

Table 1: Physiological Artifact Identification and Removal Guide

| Artifact Type | Primary Source | Frequency Characteristics | Recommended Removal Methods | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ocular Artifacts | Eye blinks and movements [34] | Similar to EEG bands [35] | Regression, Independent Component Analysis (ICA) [34] [35] | Risk of bidirectional interference; ICA is often superior [35]. |

| Muscle Artifacts (EMG) | Head/neck muscle activity [34] | Broad spectrum (0 to >200 Hz) [35] | ICA, Wavelet Transform [34] [35] | Challenging due to broad frequency distribution and statistical independence from EEG [34]. |

| Cardiac Artifacts (ECG/Pulse) | Heartbeat [34] | ~1.2 Hz (Pulse) [35] | Reference waveform (ECG), ICA [34] [35] | Pulse artifacts are difficult; ECG artifacts are easier to remove with a reference [34]. |

Experimental Protocol for ICA-based Artifact Removal: Independent Component Analysis (ICA) is a blind source separation technique that separates multichannel EEG data into statistically independent components [34] [35].

- Data Preparation: Collect multi-channel EEG data. The number of channels should be sufficient for effective source separation.

- Filtering: Apply a band-pass filter (e.g., 1-40 Hz) to remove extreme frequency noise that may interfere with ICA decomposition.

- ICA Decomposition: Use an ICA algorithm (e.g., Infomax, FastICA) to decompose the filtered EEG data into independent components:

S = U * Y, whereYis the input signal andUis the unmixing matrix [34]. - Component Identification: Analyze the topographic maps, time courses, and power spectra of the components to identify those corresponding to artifacts (e.g., eye blinks, muscle noise).

- Signal Reconstruction: Remove the artifact-laden components and reconstruct the clean EEG signal using the remaining components.

Problem 2: My SSVEP peaks are unclear or have low amplitude. What preprocessing steps can enhance the signal?

Solution: Steady-State Visually Evoked Potentials (SSVEPs) require enhancement of specific frequency components and their harmonics.

- Sub-band Filtering: Use a filter bank to decompose the EEG signal into multiple sub-bands, typically covering the fundamental and harmonic frequencies of the SSVEP stimuli. This isolates the relevant spectral information [30].

- Spatial Filtering: Apply algorithms like Task-Related Component Analysis (TRCA) or Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA). TRCA, for instance, enhances the SNR by maximizing the inter-trial covariance of the SSVEP signals, effectively extracting task-related components [30].

- Advanced Hybrid Frameworks: For maximum performance, consider a fusion approach. A framework like eTRCA+sbCNN combines the feature extraction power of an ensemble TRCA with the learning capability of a sub-band Convolutional Neural Network (sbCNN), summing their classification scores for superior frequency recognition [30].

Table 2: SSVEP Signal Enhancement Techniques Comparison

| Technique | Primary Mechanism | Key Advantage | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Bank CCA (FBCCA) | Multi-band decomposition & spatial filtering [30] | Enhances harmonics information | Foundational method, improved ITR over standard CCA [30] |

| Ensemble TRCA (eTRCA) | Maximizes inter-trial covariance [30] | Effective noise suppression, state-of-the-art traditional method | High ITR (e.g., 186.76 bits/min on BETA dataset) [30] |

| eTRCA + sbCNN | Fusion of traditional ML and Deep Learning scores [30] | Leverages complementarity of both approaches | Significantly outperforms single-model algorithms [30] |

Problem 3: How do I optimize the preprocessing pipeline for a Motor Imagery (MI)-based BCI?

Solution: Optimizing preprocessing for MI-BCI involves careful selection of frequency bands and time intervals to capture Event-Related Desynchronization (ERD) and Synchronization (ERS).

Experimental Protocol for MI-BCI Preprocessing Optimization: A study optimizing preprocessing for MI-BCI using the Taguchi method and Grey Relational Analysis (GRA) provides a robust methodology [33].

- Data Selection: Use a standardized dataset like BCI Competition IV-2b. Focus on channels C3, Cz, and C4.

- Define Factors and Levels: Optimize these key preprocessing parameters [33]:

- Time Interval (A): Post-cue intervals (e.g., 0-2s, 0-3s, 0-4s, 0-5s).

- Time Window & Step Size (B): For segmentation (e.g., 2s window with 0.125s step).

- Frequency Bands (C & D): Theta band (e.g., 4-8 Hz) and Mu+Beta bands (e.g., 8-30 Hz).

- Feature Extraction & Classification: Extract Hjorth features and classify with an SVM.

- Multi-objective Optimization: Use Taguchi GRA to find the parameter combination that maximizes classification accuracy while minimizing computational timing cost. The reported optimal combination was a 0-4s time interval, 2s window with 0.125s step, and using both Theta and Mu+Beta bands [33].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why do I get different results when using the same preprocessing pipeline with different software (e.g., OpenBCI GUI vs. LSL/BrainFlow)?

This is often due to differences in how the software handles raw data, not the preprocessing steps themselves. The OpenBCI GUI may apply minimal transformation, while direct access via PyLSL or BrainFlow might involve different data handling, such as potential truncation of the raw data's DC offset or the use of different libraries (e.g., Pandas) for data output, which can alter the raw values before your custom preprocessing is applied [36]. Solution: Always verify the raw data amplitude and properties are consistent across acquisition methods before applying your preprocessing pipeline.

What is the most effective single method for artifact removal?

While the "best" method depends on the artifact and data, Independent Component Analysis (ICA) is widely regarded as one of the most powerful and flexible single methods, particularly for ocular and muscle artifacts [34] [35]. It is superior to older techniques like regression and PCA because it does not require reference channels and can separate sources based on statistical independence rather than just orthogonality [34] [35].

For a real-time BCI, should I prioritize accuracy over processing speed?

Not exclusively. The ultimate goal is to find a balance. A complex pipeline may yield high accuracy but fail in real-time applications due to excessive latency. Research shows that optimizing the preprocessing stage considering both accuracy and timing cost is crucial for feasible online BCI systems [33]. For example, optimizing time window length and step size can significantly reduce processing time with minimal accuracy loss.

Are deep learning methods replacing traditional preprocessing?

Not yet, but they are being powerfully integrated. Deep learning models like sub-band CNNs (sbCNN) can automatically learn features from preprocessed or raw data [30]. However, traditional methods like spatial filters (TRCA) are often more interpretable and computationally efficient. The current state-of-the-art trend is to combine both, leveraging the strengths of each, as seen in the eTRCA+sbCNN framework [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Algorithms for BCI Preprocessing

| Item/Algorithm | Primary Function | Typical Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) | Blind source separation for artifact isolation and removal [34] [35] | General-purpose artifact removal, especially for ocular and EMG artifacts. |

| Task-Related Component Analysis (TRCA) | Spatial filtering to maximize inter-trial covariance [30] | SSVEP frequency recognition; enhances SNR of task-related components. |

| Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) | Spatial filtering to maximize correlation between EEG and reference templates [30] | SSVEP frequency recognition; a foundational training-free method. |

| Filter Bank | Decomposes signal into multiple frequency sub-bands [30] | SSVEP harmonic enhancement; MI-BCI rhythm isolation. |

| Wavelet Transform | Multi-resolution time-frequency analysis [34] | Non-stationary signal analysis; can be used for artifact removal and feature extraction. |

| Sub-band CNN (sbCNN) | Deep learning model for classifying filtered EEG [30] | State-of-the-art SSVEP classification; often used in hybrid models. |

| MNE-Python | Open-source Python package for EEG/MEG data analysis [36] | Full pipeline implementation: filtering, ICA, epoching, source localization. |

| BrainFlow | A unified library for a uniform data acquisition from various devices [36] | Consistent data collection from multiple BCI hardware platforms. |

Motor Imagery-based Brain-Computer Interfaces (MI-BCIs) translate the neural activity associated with imagined movements into control commands for external devices. This technology offers significant potential for neurorehabilitation and assistive technologies, particularly for individuals with motor impairments. The performance of these systems critically depends on the effective extraction and selection of discriminative features from electroencephalography (EEG) signals, which are characterized by a low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and non-stationary properties [31] [20]. The process of feature extraction and selection forms the core computational pipeline that enables the translation of raw brain activity into actionable commands, directly impacting the system's classification accuracy, robustness, and real-time applicability.

This technical support center document addresses the fundamental challenges and solutions in feature extraction and selection, framed within the broader context of optimizing BCI system performance. The guidance provided herein is structured to assist researchers and scientists in troubleshooting specific experimental issues, with methodologies ranging from conventional machine learning approaches, such as Common Spatial Patterns (CSP), to advanced deep learning embeddings that automatically learn feature representations from raw data [20] [37]. The subsequent sections provide a detailed technical framework, including comparative analyses, experimental protocols, and visualization tools, to facilitate the development and refinement of high-performance MI-BCI systems.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Feature Extraction and Selection Challenges

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary feature extraction challenges in MI-BCI systems, and how can they be mitigated? EEG signals used in MI-BCI systems present three major challenges for feature extraction. First, they possess a very low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), as the signals of interest are mixed with other brain activities and artifacts [20]. Second, EEG signals are inherently non-stationary, meaning their statistical properties change over time due to factors like fatigue or changes in the user's mental state [20]. Finally, there is high inter-subject variability, where EEG characteristics differ significantly across individuals, making it difficult to build universal models [20] [38].

Mitigation strategies include:

- Spatial Filtering: Using techniques like Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) to enhance the SNR by maximizing the variance between two classes of signals [37].

- Advanced Signal Processing: Employing time-frequency analysis (e.g., wavelets) to handle non-stationarity [39].

- Adaptive and Subject-Specific Calibration: Regularly recalibrating the system or using transfer learning to adapt to individual users and session-specific signal variations [20].

FAQ 2: How do I choose between traditional feature extraction methods and deep learning? The choice depends on your specific constraints regarding data availability, computational resources, and the need for interpretability.

Traditional Methods (e.g., CSP, Band Power, AR models):

- Use when: The available dataset is small, computational resources are limited, or you require clear interpretability of which features (e.g., sensorimotor rhythms) are driving the classification [40].

- Advantages: Lower computational cost, well-understood, and effective for many paradigms [20].

- Disadvantages: Often require manual feature engineering and may not capture complex, non-linear patterns in the data [20].

Deep Learning Methods (e.g., EEGNet, CNNs, RNNs):

- Use when: Large datasets are available, and the goal is to maximize classification accuracy for a complex task without manual feature design [20] [41].

- Advantages: Can automatically learn optimal feature representations from raw or pre-processed data, often leading to superior performance [20].

- Disadvantages: Require large amounts of data to avoid overfitting, are computationally intensive, and can act as "black boxes" with low interpretability [20] [41].

FAQ 3: What is the impact of high-dimensional feature vectors on MI-BCI performance, and how can it be addressed? High-dimensional feature vectors, often resulting from multi-channel, multi-branch feature extraction pipelines, can lead to the "curse of dimensionality" [39]. This phenomenon occurs when the number of features is excessively large compared to the number of available training trials, resulting in several problems:

- Reduced Classification Accuracy: The classifier may overfit to noise or irrelevant features in the training data, leading to poor generalization on new, unseen data [39].

- Increased Computational Complexity: Training and operation times become longer, which can hinder the development of real-time BCI systems [37] [39].

Solutions involve dimensionality reduction and feature selection:

- Feature Selection Algorithms: Methods like Relief-F and multi-objective evolutionary algorithms can identify and retain the most discriminative features, significantly reducing dimensionality while maintaining or even improving accuracy [37] [39].

- Sparse Representation: Techniques that enforce sparsity can help in constructing a more efficient and discriminative feature set [39].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Consistently Low Classification Accuracy

- Potential Causes:

- Non-discriminative Features: The extracted features do not adequately capture the ERD/ERS patterns associated with different motor imagery tasks.

- Insufficient Pre-processing: Inadequate artifact removal (e.g., from eye blinks or muscle movement) or suboptimal frequency band selection can obscure the relevant neural signals [38].

- Overfitting: The model is too complex for the amount of available training data.

- Solutions:

- Optimize Feature Extraction: Implement a multi-branch approach. For example, decompose the EEG signal into sub-bands (e.g., Alpha, Beta), extract CSP features from each narrow band, and then fuse them [37]. This captures more specific frequency information.

- Enhance Pre-processing: Apply a band-pass filter (e.g., 8-30 Hz) to isolate mu and beta rhythms, which are most relevant for motor imagery [38] [40].

- Apply Feature Selection: Use a robust feature selection method like Relief-F to eliminate redundant and non-discriminative features, thereby reducing the feature space and mitigating overfitting [37].

Problem 2: Poor Generalization Across Subjects and Sessions

- Potential Cause: The non-stationary nature of EEG signals leads to significant variations in feature distributions between different recording sessions and different individuals [20].

- Solutions:

- Utilize Transfer Learning (TL): Train a model on data from multiple subjects and then fine-tune it with a small amount of data from a new subject. The "leave-one-subject-out" and adaptation learning approaches have been shown to reduce training time and improve subject-specific classification accuracy [20].

- Employ Domain Adaptation Techniques: Algorithms that explicitly compensate for the distribution shift between training and test data can enhance cross-session and cross-subject reliability.

- Data Augmentation: Increase the effective size and diversity of your training set using methods like adding Gaussian noise, signal cropping, or window warping. This makes the model more robust to variations [20].

Problem 3: High Computational Latency Unsuitable for Real-Time BCI

- Potential Causes:

- Inefficient Feature Extractors: The chosen feature extraction algorithm is computationally too heavy.

- Feature Vector Dimensionality: The number of features is too high, slowing down the classification process.

- Solutions:

- Algorithm Selection: For real-time systems, prefer computationally efficient feature extractors like Mean Absolute Value (MAV), Band Power (BP), or Auto-Regressive (AR) models, which have been successfully used in online BCI systems [40].

- Implement Dimensionality Reduction: As outlined in FAQ 3, applying feature selection is critical. Using a smaller, optimized set of features can dramatically decrease computation time without sacrificing performance [37] [39].

- Channel Selection: Reduce the number of EEG channels used for feature extraction by identifying the most informative electrodes for the specific MI task, as this directly reduces the data dimensionality [41].

Comparative Technical Analysis of Feature Engineering Methods

Quantitative Performance of Feature Extraction Algorithms

Table 1: Comparison of traditional and deep learning-based feature extraction methods for MI-BCI.

| Method Category | Specific Technique | Reported Performance (Accuracy) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Filtering | Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) [37] | Varies by dataset; baseline for many studies. | Maximizes variance between classes; effective for binary MI. | Performance drops without subject-specific tuning. |

| Time-Domain | Mean Absolute Value (MAV) [40] | ~75% (subject-specific, 3-class) | Computationally very simple and fast. | May miss complex spectral patterns. |

| Time-Domain | Auto-Regressive (AR) Models [40] | ~75% (subject-specific, 3-class) | Models signal generation process; good for stationary signals. | Sensitive to noise and non-stationarity. |

| Frequency-Domain | Band Power (BP) [40] | ~75% (subject-specific, 3-class) | Intuitively linked to ERD/ERS phenomena. | Requires precise band selection. |

| Deep Learning | EEGNet [41] | Superior to many benchmarks across paradigms. | High accuracy; good generalization with limited data. | Lower physiological interpretability. |

| Feature Fusion | CSP + DTF + Graph Theory (CDGL) [41] | 89.13% (Beta band, 8 electrodes) | Combines spatial, spectral, and network connectivity features. | Increased computational complexity. |

Performance of Feature Selection Techniques

Table 2: Efficacy of different feature selection strategies in improving MI-BCI classification.

| Feature Selection Method | Type | Impact on Performance | Computational Cost | Key Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relief-F [37] | Filter | Improved accuracy with reduced feature vector size. | Moderate | Effective at identifying features that distinguish nearby instances. |

| Evolutionary Multi-objective [39] | Wrapper | Similar or better Kappa values with significant feature reduction. | High | Optimizes for both accuracy and classifier generalization. |

| LASSO [41] | Embedded | Effective for filtering redundant features in fused models. | Low to Moderate | Built into the learning process, promotes sparsity. |

| Performance-based Additive Fusion [38] | Wrapper | Achieved 99% accuracy in a subject-independent algorithm. | High | Systematically builds an optimal feature subset from a large pool. |

Experimental Protocols for Feature Engineering

Protocol 1: Multi-Band CSP with Feature Selection

This protocol details the methodology for achieving high classification accuracy using a multi-band decomposition and robust feature selection, as validated on multiple benchmark datasets [37].

Data Acquisition & Pre-processing:

- Record or obtain multi-channel EEG data according to the international 10-20 system.

- Apply a band-pass filter (e.g., 8-30 Hz) to retain mu and beta rhythms.

- Segment the data into epochs time-locked to the motor imagery cue.

Multi-Band Feature Extraction: