NPDOA Parameter Sensitivity Analysis: A Guide for Robust Drug Discovery and Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide to parameter sensitivity analysis for the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA), tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

NPDOA Parameter Sensitivity Analysis: A Guide for Robust Drug Discovery and Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to parameter sensitivity analysis for the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA), tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers the foundational principles of NPDOA and the critical role of sensitivity analysis in quantifying uncertainty and robustness in computational models. The content explores methodological approaches for implementation, including advanced techniques like the one-at-a-time (OAT) method, and their application in real-world scenarios such as identifying molecular drug targets in signaling pathways. It further addresses common troubleshooting challenges and optimization strategies to enhance model performance and reliability. Finally, the article discusses validation frameworks and comparative analyses with other optimization algorithms, offering a complete resource for leveraging NPDOA to build more predictive and trustworthy models in biomedical research.

Understanding NPDOA and the Critical Role of Sensitivity Analysis in Computational Biomedicine

Core Principles and Algorithm Definition

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) is a metaheuristic optimization algorithm that models the dynamics of neural populations during cognitive activities [1]. It belongs to the category of population-based metaheuristic optimization algorithms (PMOAs), which are characterized by generating multiple potential solutions (individuals) that evolve over iterations to form new populations [2]. As a mathematics-based metaheuristic, NPDOA falls within the broader classification of algorithms inspired by mathematical theories and concepts, rather than direct biological swarm behaviors or evolutionary principles [1].

The fundamental innovation of NPDOA lies in its utilization of recurrent neural networks (RNNs) to capture temporal dependencies in solution sequences. RNNs are particularly suited for this purpose as they excel at processing temporal or sequential data, analyzing past patterns within sequences to predict future outcomes [2]. This capability allows NPDOA to learn from the historical inheritance relationships between individuals in successive populations, creating a feedback mechanism that guides the generation of promising new solutions.

Biological Inspiration and Mechanistic Analogy

NPDOA draws its inspiration from the dynamic processes of neural populations during cognitive tasks. While specific details of its biological mapping are not fully elaborated in the available literature, the algorithm conceptually mirrors how interconnected neurons exhibit coordinated activity patterns that evolve over time to solve computational problems.

The algorithm operates on a principle analogous to "all cells come from pre-existing cells" – a concept drawn from cellular pathology that similarly applies to population-based algorithms where each new generation of solutions emerges from previous populations [2]. This genealogical approach to solution evolution enables NPDOA to track ancestral relationships between solutions, forming time series data that captures the progression toward optimality.

Table: Comparison of NPDOA with Traditional Optimization Approaches

| Feature | Traditional Deterministic Methods | Heuristic Algorithms | NPDOA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Mathematical theories & problem structure [1] | Heuristic rules [1] | Neural population dynamics & RNNs [1] [2] |

| Solution Guarantee | Optimal with strict assumptions [1] | Near-optimal [1] | High-quality with exploration/exploitation balance [1] |

| Computational Complexity | High for large-scale problems [1] | Variable quality [1] | Adaptive complexity with learning [2] |

| Local Optima Avoidance | Prone to getting stuck [1] | Variable performance [1] | Effective through dynamic exploration [1] |

| Learning Capability | None | Limited | Yes, via RNN sequence learning [2] |

Algorithm Workflow and Architecture

The NPDOA framework implements an Evolution and Learning Competition Scheme (ELCS) that creates a synergistic relationship between traditional evolutionary mechanisms and neural network-guided optimization [2]. This architecture enables the algorithm to automatically select the most promising method for generating new individuals based on their demonstrated performance.

NPDOA Algorithm Workflow: Integration of evolutionary and learning approaches

The workflow operates through several key mechanisms:

Population Initialization: The algorithm begins with a randomly generated population of potential solutions, similar to other population-based metaheuristics.

Genealogical Archiving: Each individual maintains an archive storing information about its ancestors across generations, creating time series data that captures evolutionary trajectories [2].

Fitness Evaluation: All individuals are evaluated using an objective function specific to the optimization problem.

Competitive Generation Mechanism: The ELCS creates a probabilistic competition between traditional evolutionary operators and the RNN predictor. The method that produces more individuals with better fitness receives higher selection probability in subsequent iterations [2].

RNN-Guided Solution Generation: The RNN component learns from ancestral sequences to predict new candidate solutions with improved fitness, effectively modeling how neural populations adapt based on historical activity patterns.

Advantages and Performance Characteristics

NPDOA demonstrates several distinctive advantages that make it suitable for complex optimization tasks:

Balance Between Exploration and Exploitation

The algorithm effectively balances global exploration of the search space with local refinement of promising solutions. This balance is achieved through the complementary actions of the traditional evolutionary component (exploration) and the RNN guidance mechanism (exploitation) [1].

Adaptive Learning Capability

Unlike traditional metaheuristics that follow fixed update rules, NPDOA's RNN component enables it to learn patterns from the specific optimization landscape, adapting its search strategy based on accumulated experience [2].

Robustness Against Local Optima

The integration of multiple solution generation mechanisms and the maintenance of diverse solution archives help prevent premature convergence to suboptimal solutions, a common challenge in optimization [1].

Table: NPDOA Performance on Benchmark Functions

| Benchmark Suite | Dimensions | Performance Ranking | Key Competitive Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|

| CEC 2017 [1] | 30 | 3.00 (Friedman ranking) | NRBO, SSO, SBOA, TOC [1] |

| CEC 2017 [1] | 50 | 2.71 (Friedman ranking) | NRBO, SSO, SBOA, TOC [1] |

| CEC 2017 [1] | 100 | 2.69 (Friedman ranking) | NRBO, SSO, SBOA, TOC [1] |

| CEC 2022 [1] | Multiple | Superior performance | Classical and state-of-the-art PMOAs [1] |

Technical Support Center: NPDOA Troubleshooting Guide

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does my NPDOA implementation converge prematurely to suboptimal solutions?

A: Premature convergence typically indicates insufficient exploration diversity. Implement three corrective measures: First, increase the population size to maintain genetic diversity. Second, adjust the competition probability parameters in the ELCS to favor the method (PMOA or RNN) that demonstrates better diversity maintenance. Third, introduce an archive management strategy that preserves historically important solutions while preventing overcrowding of similar individuals [2].

Q2: How should I configure the RNN architecture within NPDOA for optimal performance?

A: The RNN configuration should align with problem complexity. For moderate-dimensional problems (10-50 dimensions), begin with a single-layer LSTM or GRU network with 50-100 hidden units. For high-dimensional problems (100+ dimensions), implement a deeper architecture with 2-3 layers and 100-200 units per layer. Utilize hyperbolic tangent (tanh) activation functions to handle the signed, continuous-valued optimization landscapes typical of numerical optimization problems [2].

Q3: What is the appropriate stopping criterion for NPDOA experiments?

A: Establish a multi-factor stopping criterion that combines: (1) Maximum iteration count (1000-5000 iterations depending on problem complexity), (2) Solution quality threshold (when fitness improvement falls below 0.01% for 50 consecutive iterations), and (3) Population diversity metric (when genotypic diversity drops below 5% of initial diversity). This approach balances computational efficiency with solution quality assurance [1].

Q4: How does NPDOA compare to other metaheuristics like Genetic Algorithms or Particle Swarm Optimization?

A: NPDOA differs fundamentally through its integration of learning mechanisms. While Genetic Algorithms (evolution-based) and Particle Swarm Optimization (swarm intelligence-based) rely on fixed update rules, NPDOA employs RNNs to learn patterns from the optimization process itself. This enables adaptation to problem-specific characteristics, particularly beneficial for problems with temporal dependencies or complex correlation structures [1] [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for NPDOA Implementation

| Component | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Population Initializer | Generates initial candidate solutions | Use Latin Hypercube Sampling for better space coverage; problem-dependent representation |

| Fitness Evaluator | Assesses solution quality | Encodes problem-specific objective function; most computationally expensive component |

| Genealogical Archive | Stores ancestral solution sequences | Implement with circular buffers; control size to manage memory usage [2] |

| RNN Predictor | Learns from sequences to generate new solutions | LSTM/GRU networks; dimension matching between input/output layers [2] |

| Competition Manager | Selects between PMOA and RNN generation methods | Tracks success rates; implements probabilistic selection with adaptive weights [2] |

| Diversity Metric | Monitors population variety | Genotypic and phenotypic measures; triggers diversity preservation when low |

Experimental Protocol for Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

For researchers conducting parameter sensitivity analysis on NPDOA, follow this standardized protocol:

Baseline Configuration: Establish a reference parameter set including population size (50-100), RNN architecture (single-layer GRU with 64 units), learning rate (0.01), and competition probability (initially 0.5 for both methods).

Sensitivity Metric Definition: Quantify parameter sensitivity using normalized deviation in objective function value (Δf/f_ref) and success rate across multiple runs.

One-Factor-at-a-Time Testing: Systematically vary each parameter while keeping others constant, executing 30 independent runs per configuration to account for algorithmic stochasticity.

Interaction Analysis: Employ factorial experimental designs to identify significant parameter interactions, particularly between population size and RNN complexity.

Benchmark Suite Application: Evaluate sensitivity across diverse problem types from CEC 2017 and CEC 2022 benchmark suites, including unimodal, multimodal, hybrid, and composition functions [1].

This protocol enables comprehensive characterization of NPDOA's parameter sensitivity profile, supporting robust algorithm configuration for specific application domains including drug development and engineering design optimization.

What is parameter sensitivity analysis and why is it a critical step in model validation?

Parameter Sensitivity Analysis is a method used to determine the robustness of an assessment by examining the extent to which results are affected by changes in the methods, models, values of unmeasured variables, or assumptions [3]. Its primary purpose is to identify "results that are most dependent on questionable or unsupported assumptions" [3].

In the context of NPDOA (Improved Nuclear Predator Optimization Algorithm) parameter sensitivity analysis research, it is a critical way to assess the impact, effect, or influence of key assumptions or variations on the overall conclusions of a study [3]. Consistency between the results of a primary analysis and the results of a sensitivity analysis may strengthen the conclusions or credibility of the findings [3].

What are the core methodological steps for conducting a parameter sensitivity analysis?

The general workflow for performing a parameter sensitivity analysis involves a structured process from defining the scope to interpreting the results, as shown in the diagram below.

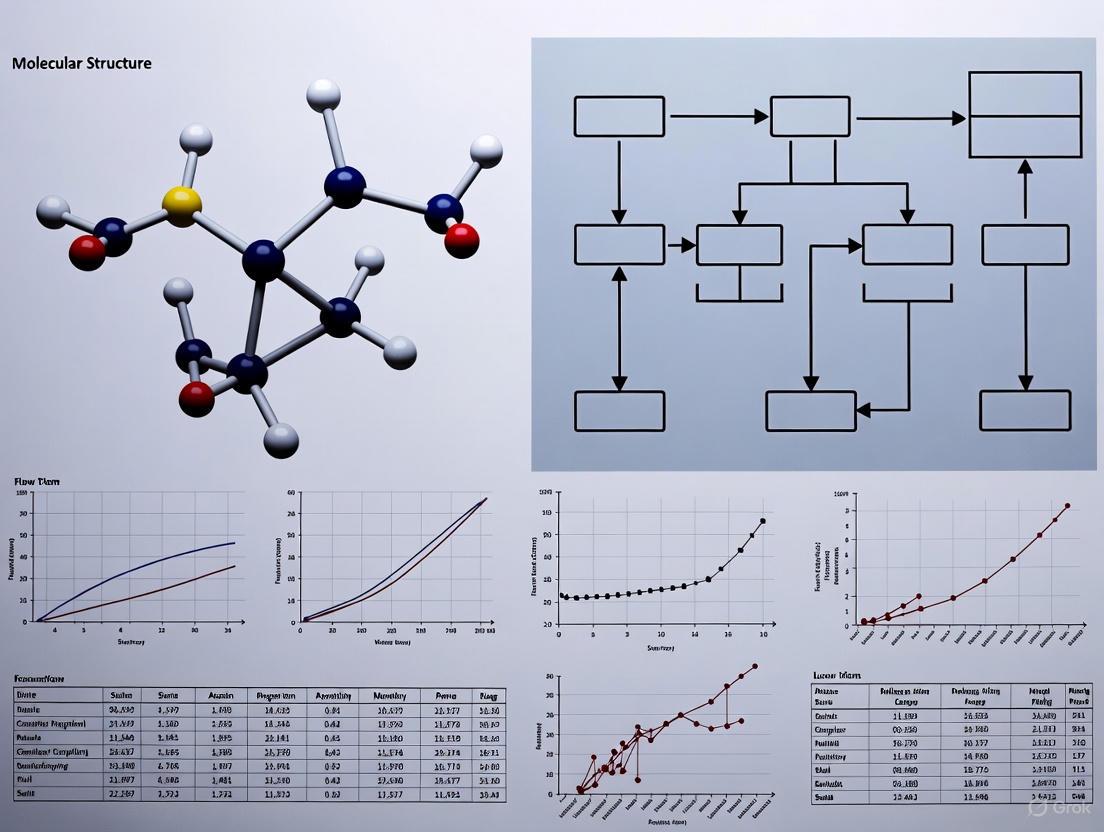

Figure 1: The core workflow for conducting a parameter sensitivity analysis.

The table below outlines the key reagent solutions and computational tools required for implementing this methodology.

Research Reagent Solutions for Sensitivity Analysis

| Item/Tool Category | Specific Example | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization Framework | INPDOA-enhanced AutoML [4] | Base model architecture for evaluating parameter sensitivity. |

| Sensitivity Analysis Theory | Fiacco's Framework, Robinson's Theory [5] | Provides mathematical foundation for evaluating solution sensitivity to parameter changes. |

| Reference Point | NPD Team (NPDT) Expectations [6] | Serves as a benchmark for evaluating gains and losses in decision-making. |

| Visualization System | MATLAB-based CDSS [4] | Enables real-time prognosis visualization and interpretation of sensitivity results. |

| Statistical Validation | Decision Curve Analysis [4] | Quantifies the net benefit improvement of the model over conventional methods. |

How does parameter sensitivity analysis integrate into a broader research workflow like NPDOA development?

Parameter sensitivity analysis is not an isolated activity but a component integrated throughout the model development and validation lifecycle. Its role in a broader research workflow, such as developing an INPDOA algorithm, is visualized below.

Figure 2: The role of sensitivity analysis in a broader model development workflow.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: My model's results change significantly when I slightly alter a parameter. Does this mean my model is invalid?

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: High sensitivity to a single parameter.

- Investigation Steps:

- Check Parameter Plausibility: Are the tested parameter variations within a realistic, physically or biologically plausible range? An overly wide range may yield misleading sensitivity.

- Identify Interactions: Use global sensitivity analysis methods to check if the effect is isolated or if it interacts with other parameters. The issue might be a parameter combination, not a single parameter.

- Review Model Structure: Examine if the model structure itself is overly dependent on that parameter, indicating a potential structural flaw.

- Solution: If the parameter is critical and its true value is highly uncertain, prioritize obtaining more precise estimates for it through further experimentation or literature review. If the model structure is at fault, consider model refinement.

FAQ 2: How do I choose between local (one-at-a-time) and global sensitivity analysis methods?

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Uncertainty in selecting the appropriate sensitivity analysis method.

- Decision Framework:

- Use Local Methods (e.g., OAT) when your model is computationally very expensive, and you need a first-order, quick screening of parameter influences. It is simpler to implement and interpret but can miss parameter interactions [5].

- Use Global Methods (e.g., Sobol', Morris) when your model has suspected parameter interactions and you need a comprehensive understanding of how parameters collectively influence the output. This is the preferred approach for robust validation but is more computationally demanding.

- Solution: For a rigorous analysis like validating an NPDOA model, start with a global method or use a local method for preliminary screening followed by a global method on the most influential parameters.

FAQ 3: After performing sensitivity analysis, how do I report the results to convince reviewers of my model's robustness?

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Effectively communicating sensitivity analysis findings.

- Reporting Checklist:

- Clearly State the Method: Specify whether the analysis was local or global and justify the choice.

- Define Parameter Ranges: Explicitly state the ranges or distributions tested for each parameter and the rationale behind them.

- Present Quantitative Results: Use tables or plots (e.g., Tornado plots, Sobol' indices) to show the relative influence of parameters. The table below provides a template.

- Link to Conclusion: Directly state how the results of the sensitivity analysis support the robustness (or highlight the limitations) of your primary findings [7] [3].

Example Table for Reporting Sensitivity Analysis Results

| Parameter | Base Case Value | Tested Range | Sensitivity Index | Impact on Primary Outcome | Robustness Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning Rate | 0.01 | 0.001 - 0.1 | 0.75 | High: AUC varied from 0.80 to 0.87 | Model is sensitive; parameter requires precise tuning. |

| Batch Size | 32 | 16 - 128 | 0.15 | Low: AUC variation < 0.01 | Model is robust to this parameter. |

| Number of Hidden Layers | 3 | 1 - 5 | 0.45 | Medium: Performance peaked at 3 layers | Robust within a defined range. |

FAQ 4: In my clinical trial analysis, the results changed when I handled missing data differently. How should I interpret this?

Troubleshooting Guide:

- Problem: Conclusions are not robust to different methods of handling missing data.

- Investigation Steps:

- Analyze Missingness Pattern: First, determine if the data is missing completely at random (MCAR), at random (MAR), or not at random (MNAR). This informs the choice of handling method.

- Pre-specify Methods: In your protocol, pre-specify the primary method for handling missing data (e.g., multiple imputation) and plan sensitivity analyses using alternative methods (e.g., complete-case analysis, last observation carried forward) [7] [3].

- Solution: If results are consistent across different plausible methods, confidence in the conclusions is high. If results change, you must transparently report this and conclude that your findings are conditional on the assumptions about the missing data. The validity of the primary analysis is strengthened by showing its results are similar to the sensitivity analysis [7].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary goal of parameter sensitivity analysis in drug response modeling? Parameter sensitivity analysis aims to identify which input parameters in your drug response model have the most significant impact on the output. This helps you distinguish critical process parameters (CPPs) from non-critical ones, allowing you to focus experimental resources on controlling the factors that truly matter for model accuracy and reliability [8] [9].

Q2: Why is quantifying uncertainty important in this context? Quantifying uncertainty is essential because all mathematical models and experimental data contain inherent variability. Explicitly measuring uncertainty helps researchers understand the confidence level in model predictions, supports robust decision-making in drug development, and ensures the development of reliable, high-quality treatments [10].

Q3: Which experimental design is most efficient when screening a large number of potential factors? A Screening Design of Experiments (Screening DOE), such as a fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman design, is the most efficient choice. These designs allow you to investigate the main effects of many factors with a minimal number of experimental runs, quickly identifying the most influential variables before moving on to more detailed optimization studies [11].

Q4: What is the difference between a critical process parameter (CPP) and a critical quality attribute (CQA)? A Critical Quality Attribute (CQA) is a measurable property of the final product (e.g., drug potency, purity) that must be controlled to ensure product quality. A Critical Process Parameter (CPP) is a process variable (e.g., temperature, mixing time) that has a direct, significant impact on a CQA. Controlling CPPs is how you ensure your CQAs meet the desired standards [9].

Q5: How can I handle uncertainty that arises from differences between individual biological donors? Donor-to-donor variability is a common source of uncertainty in biological models. A robust approach is to use a linear mixed-effects model within your Design of Experiments (DOE). This statistical model can separate the fixed effects of the process parameters you are testing from the random effects of donor variability, providing more accurate insights into which parameters are truly critical [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Variability in Model Outputs Despite Tightly Controlled Inputs

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Unidentified interactions between process parameters.

- Cause: Inadequate measurement system.

- Solution: Conduct a Gage Repeatability and Reproducibility (Gage R&R) study. If the measurement system's variation contributes more than 20% to the total observed variation, your measurements are too noisy to detect meaningful parameter effects, and the measurement process must be improved first [9].

- Cause: Uncontrolled noise factors (e.g., reagent lot variation, operator differences).

- Solution: Implement randomization and blocking in your experimental design. Using multiple lots of a critical raw material and statistically "blocking" on this factor can isolate its effect from the process parameters you are studying [9].

Issue 2: The Model Fails to Accurately Predict New Experimental Data

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Poor distinction between aleatoric (data) and epistemic (model) uncertainty.

- Solution: Implement Uncertainty Estimation (UE) techniques like Bayesian Neural Networks (BNNs) or Ensemble Methods. BNNs treat model parameters as probability distributions, simultaneously capturing both types of uncertainty. Ensembles train multiple models and use their prediction variance as a measure of confidence [10].

- Cause: The model's operational range is too narrow.

- Solution: Ensure your parameter sensitivity analysis is conducted over a sufficiently wide "knowledge space." The ranges used in your DOE should encompass all plausible operating conditions to build a model that is robust and generalizable [9].

Issue 3: Inefficient or Overwhelming Experimental Workflow for Parameter Screening

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Attempting a full factorial analysis with too many factors.

- Cause: Incorrect assumption of negligible interaction effects.

- Solution: If you suspect interactions are important, choose a definitive screening design or a fractional factorial design with higher resolution. If your initial screening results are ambiguous, techniques like "folding" the design can help de-alias and reveal significant interactions [11].

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Staged Design of Experiments for Identifying Critical Parameters

This protocol outlines a systematic approach to efficiently identify CPPs that influence key outputs in drug response models, aligning with the NPDOA research context [9].

Objective: To screen a large number of process parameters and identify those with a statistically significant impact on a predefined Critical Quality Attribute (CQA). Workflow:

- Screening Phase: Utilize a fractional factorial or Plackett-Burman design to evaluate the main effects of many factors (typically 5+). This efficiently narrows down the list of potential CPPs.

- Refining Phase: On the reduced set of factors, conduct a full factorial design. This estimates both main effects and two-factor interactions more precisely.

- Optimization Phase: Use a Central Composite or Box-Behnken design on the confirmed CPPs to model nonlinear (quadratic) effects and identify the optimal operating range (design space).

Key Parameters to Vary: Factors like temperature, pH, mixing time, reagent concentrations, and cell passage number. Expected Output: A ranked list of parameters by significance, an understanding of their interactions, and a defined design space for optimal model performance.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Uncertainty Using Ensemble Methods

This protocol provides a practical method for quantifying prediction uncertainty in complex, non-linear drug response models.

Objective: To attach a confidence estimate to every prediction made by a drug response model. Workflow:

- Model Training: Train multiple instances of your base model (e.g., neural network, random forest) on the same dataset. Vary the initial random seeds, or use bootstrap sampling to create slightly different training sets for each model.

- Prediction: For a new input, generate a prediction from each model in the ensemble.

- Uncertainty Quantification: Calculate the mean of the predictions as the final model output. Use the variance or standard deviation of the predictions across the ensemble as the measure of uncertainty for that output.

- High Variance: Indicates high model (epistemic) uncertainty, often due to a lack of similar data in the training set.

- Low Variance: Indicates high confidence in the prediction [10].

Key Parameters: Number of models in the ensemble, model architecture, and training parameters. Expected Output: A prediction accompanied by a quantitative uncertainty metric (e.g., standard deviation, confidence interval).

The following tables summarize core concepts and data related to critical parameter identification and uncertainty estimation.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Design of Experiments (DOE) Types

| DOE Type | Primary Purpose | Key Strength | Key Limitation | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening (e.g., Plackett-Burman) [11] | Identify vital few factors from many | High efficiency; minimal runs | Cannot estimate interactions reliably; confounding | Early-stage factor screening |

| Full Factorial [9] | Estimate all main effects and interactions | Comprehensive; reveals interactions | Run number grows exponentially with factors | Refining analysis on a small number of factors (<5) |

| Response Surface (e.g., Central Composite) [9] | Model curvature and find optimal settings | Can identify non-linear relationships | Requires more runs than factorial designs | Final-stage optimization of critical parameters |

Table 2: Classification and Quantification of Uncertainty Types in AI/ML Models

| Uncertainty Type | Source | Common Quantification Methods | Impact on Drug Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aleatoric (Data Uncertainty) [10] | inherent noise in the input data | entropy of the output distribution, data variance | Limits model precision; cannot be reduced with more data. |

| Epistemic (Model Uncertainty) [10] | lack of knowledge or training data in certain regions | Bayesian Neural Networks, Ensemble variance, MC Dropout | Can be reduced by collecting more data in sparse regions. |

| Distributional [10] | input data is from a different distribution than the training data | distance measures (e.g., reconstruction error), anomaly detection | Model may perform poorly on new patient populations or experimental conditions. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Drug Response Modeling Experiments

| Item | Function in Experiment | Criticality Note |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh Human Blood / Primary Cells | Biologically relevant starting material for autologous therapies or ex-vivo testing. | High donor-to-donor variability is a major source of uncertainty; requires multiple donors for robust results [8]. |

| Cell Culture Media & Supplements | Provides the nutrient base for maintaining cell viability and function during experiments. | Batch-to-batch variation can be a significant noise factor; consider blocking designs or using a single, large batch [9]. |

| Chemical Coagulants (e.g., Thrombin) | Used in assays to simulate or measure biological processes like clotting or gel formation. | Parameters like time-to-use and filtration can be potential Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) that impact product attributes [8]. |

| Ascorbic Acid / Other Activators | Acts as a reagent to activate specific biological pathways or cellular responses in the model. | Pre-mixing with other components can be a significant CPP, affecting outcomes like time-to-gel [8]. |

| Defined Buffers & pH Solutions | Maintains a stable and physiologically relevant chemical environment for the assay. | Temperature and pH are classic parameters to investigate for criticality in almost all biochemical models. |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Experimental Workflow for Parameter Analysis

Uncertainty Estimation & Explainability Framework

The Impact of Parameter Variability on Predictive Outcomes in Biological Systems

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why does my predictive biological model show high outcome variability even with high-quality input data? High outcome variability often stems from unaccounted-for parameter sensitivity. Key biological and experimental parameters, such as product weight and biological respiration rates, have been shown to collectively account for over 80% of output variability in systems like modified atmosphere storage [12]. To diagnose, perform a sensitivity analysis (e.g., Monte Carlo simulations or one-factor-at-a-time methods) to identify which parameters your model is most sensitive to, and then prioritize refining the estimates for those [12].

2. What is the difference between a large assay window and a good Z'-factor, and which is more important for a robust predictive assay? A large assay window indicates a strong signal change between the minimum and maximum response states. The Z'-factor, however, is a more comprehensive metric of assay robustness as it integrates both the assay window size and the data variability (noise) [13]. An assay can have a large window but be too noisy for reliable screening. A Z'-factor > 0.5 is generally considered suitable for screening, as it indicates a clear separation between positive and negative controls [13].

3. My probabilistic genotyping results vary significantly when I re-run the analysis. What could be causing this? Inconsistent results in probabilistic genotyping software (PGS) can be caused by variations in the analytical parameters set by the user, such as the analytical threshold, stutter models, and drop-in parameters [14]. Different software programs use different statistical models, and the same data analyzed with different parameters or different PGS can yield different outcomes. Ensure consistent and proper parametrization across all analyses and that all users have a firm understanding of how the informatics tools work [14].

4. How can I improve the predictive performance of an Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) model for a biological outcome? Enhancing an AutoML model often involves optimizing the underlying algorithm and feature selection. Research has demonstrated that using an improved metaheuristic algorithm for AutoML optimization can significantly boost performance. For instance, one study showed that an INPDOA-enhanced AutoML model achieved a test-set AUC of 0.867 for predicting surgical complications, outperforming traditional models. This approach synergistically optimizes base-learner selection, feature screening, and hyperparameters [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Predictive Performance in a Computational Biological Model

Step 1: Identify Influential Parameters

- Action: Conduct a global sensitivity analysis on all input parameters.

- Protocol: Use a Monte Carlo simulation approach. Define a probability distribution for each input parameter (e.g., respiration rate, diffusion rate, product weight). Run the model thousands of times, each time sampling from these distributions. Analyze the output (e.g., via regression techniques) to quantify how much of the output variance each input parameter explains [12].

- Expected Outcome: A ranked list of parameters by their influence on model predictions.

Step 2: Incorporate Non-Linear Relationships

- Action: Review the relationship between the most sensitive parameters and the model output.

- Protocol: If the initial model uses linear assumptions, replace them with biologically accurate non-linear equations. For example, model the effect of temperature on a respiration rate using an Arrhenius equation, which captures the exponential relationship commonly seen in biological systems [12].

- Expected Outcome: Improved model fidelity, especially when extrapolating beyond the original calibration data range.

Step 3: Validate with a Focus on Key Parameters

- Action: Design a validation experiment that specifically tests the model's behavior under varying conditions of the most sensitive parameters.

- Protocol: As performed in a broccoli storage study, set up a physical system (e.g., a 70-litre storage box) and run it under a dynamic temperature profile (e.g., 1°C to 20°C). Measure the key outcome (e.g., O₂ concentration) and compare it to the model's predictions. A robust model should maintain stability, such as holding O₂ at 3.5 ± 0.5% despite the fluctuations [12].

Issue: Lack of Assay Window in a TR-FRET-Based Drug Discovery Assay

Step 1: Verify Instrument Setup

- Action: Confirm the microplate reader is configured correctly for TR-FRET.

- Protocol: Refer to instrument-specific setup guides. The most common reason for no assay window is an incorrect choice of emission filters. TR-FRET requires precise filter sets that match the donor and acceptor dyes (e.g., Tb or Eu). Test your reader's setup using control reagents from your assay kit [13].

Step 2: Check Reagent and Compound Handling

- Action: Investigate the preparation of stock solutions and reagents.

- Protocol: The primary reason for differences in EC50/IC50 values between labs is often differences in 1 mM stock solution preparation. Ensure accurate weighing, dissolution, and storage of compounds. For the reagents, use ratiometric data analysis (acceptor signal / donor signal) to account for lot-to-lot variability and pipetting errors [13].

Step 3: Perform a Development Reaction Test

- Action: Determine if the problem is with the instrument or the biochemical reaction.

- Protocol: Using the assay's 100% phosphopeptide control and substrate, perform a development reaction with buffer. Do not expose the phosphopeptide to development reagent. Expose the substrate to a 10-fold higher concentration of development reagent. A properly functioning biochemistry should show a 10-fold difference in the ratio between these two controls. If not, the development reagent concentration likely needs optimization [13].

Table 1: Parameter Sensitivity Analysis in a Modified Atmosphere Storage Model (Case Study: Broccoli) This table summarizes the impact of varying key parameters on the Blower ON Frequency (BOF), which is critical for maintaining O₂ control. The data illustrates that not all parameters contribute equally to outcome variability [12].

| Parameter | Impact on Output Variability | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Product Weight | High | One of the two most influential parameters. |

| Respiration Rate | High | One of the two most influential parameters. |

| Product Weight & Respiration Rate (Combined) | >80% | Accounted for over 80% of BOF variability. |

| Temperature | Medium | Affected BOF and respiration rates, causing temporary gas fluctuations. |

| Gas Diffusion Rate | Lower | Less influential compared to product-related parameters. |

Table 2: Performance of an INPDOA-Enhanced AutoML Model in a Surgical Prognostic Study This table compares the predictive performance of a novel AutoML model against traditional methods for forecasting outcomes in autologous costal cartilage rhinoplasty [4].

| Model / Metric | AUC (1-Month Complications) | R² (1-Year ROE Score) |

|---|---|---|

| INPDOA-Enhanced AutoML | 0.867 | 0.862 |

| Traditional ML Models | Lower | Lower |

| First-Generation Regression Models | ~0.68 (e.g., CRS-7 scale) | Not Specified |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Sensitivity Analysis Using Monte Carlo Simulation

This methodology is used to evaluate the impact of parameter variability on model robustness and identify critical parameters [12].

- Define Input Parameters and Distributions: Identify all model inputs (e.g., product respiration rate, supply chain temperature, gas diffusion, product quantity). For each, define a realistic probability distribution (e.g., Normal, Uniform) based on experimental measurements or literature.

- Generate Parameter Sets: Use software to randomly sample a value from each parameter's distribution, creating thousands of unique input vectors.

- Run Simulations: Execute the model for each generated input vector.

- Analyze Output: Collect the output data from all simulations. Use statistical methods (e.g., regression analysis, variance decomposition) to determine the contribution of each input parameter to the variance in the output.

- Validate: Conduct a physical experiment, like monitoring O₂ in a 70-litre box with 16 kg of broccoli under dynamic temperatures, to confirm the model's stability despite parameter uncertainties [12].

Protocol 2: Development of an INPDOA-Enhanced AutoML Prognostic Model

This protocol outlines the steps for creating a high-performance predictive model for biological or clinical outcomes [4].

- Data Collection and Cohort Partitioning: Collect a retrospective dataset with over 20 parameters spanning demographic, clinical, surgical, and behavioral domains. Divide the data into training and internal test sets (e.g., 8:2 split) using stratified random sampling to preserve outcome distribution. An external validation set from a different center is recommended.

- Automated Machine Learning Framework: Implement an AutoML framework that integrates three synergistic mechanisms:

- Base-Learner Selection: The algorithm selects from options like Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machine, XGBoost, or LightGBM.

- Feature Screening: Bidirectional feature engineering identifies critical predictors.

- Hyperparameter Optimization: An Improved Native Prairie Dog Optimization Algorithm (INPDOA) is used to fine-tune model parameters.

- Model Validation and Interpretation: Validate the final model on the held-out test sets. Use SHAP values to quantify variable contributions, ensuring the model is explainable. Perform decision curve analysis to confirm clinical utility [4].

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Parameter Sensitivity Analysis Workflow

INPDOA AutoML Model Development

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for Predictive Biology Experiments

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| LanthaScreen TR-FRET Assays | Used in drug discovery for studying kinase activity and protein interactions. The ratiometric (acceptor/donor) readout accounts for pipetting and reagent variability [13]. |

| Z'-LYTE Assay Kit | A fluorescence-based assay for kinase inhibition profiling. The output is a ratio that correlates with the percentage of phosphorylated peptide substrate [13]. |

| Microplate Reader with TR-FRET Capability | Essential for reading TR-FRET assays. Must be equipped with the precise excitation and emission filters recommended for the specific donor (Tb or Eu) and acceptor dyes [13]. |

| Programmable Air Blower System | Used in controlled-atmosphere studies (e.g., produce storage) to regulate gas composition (O₂, CO₂) within a sealed environment based on sensor input or a mathematical model [12]. |

| Probabilistic Genotyping Software (PGS) | Analyzes complex forensic DNA mixtures. Proper parameterization (analytical threshold, stutter models) is critical for reliable, reproducible results [14]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core purpose of a sensitivity coefficient in our parameter analysis? A sensitivity coefficient quantifies how much a specific model output (e.g., a predicted drug efficacy metric) changes in response to a small change in a particular input parameter. This helps you identify which parameters have the most significant impact on your results, guiding where to focus experimental refinement and resources [15].

Q2: How does a partial derivative differ from an ordinary derivative? An ordinary derivative is used for functions of a single variable and describes the rate of change of the function with respect to that variable. A partial derivative, crucial for multi-variable functions common in complex biological models, measures the rate of change of the function with respect to one specific input variable, while holding all other input variables constant [16].

Q3: The sensitivity analysis results show high uncertainty. What are the primary sources? High uncertainty in sensitivity analysis often stems from two key areas. First, parameter uncertainty, which includes variability inherent in the experimental measurements of the parameters themselves or a lack of precise knowledge about them. Second, model structure uncertainty, which arises from the assumptions and simplifications built into the mathematical model itself [15].

Q4: What is the difference between uncertainty and variability? In the context of model analysis, uncertainty refers to a lack of knowledge about the true value of a parameter that is, in theory, fixed (e.g., the exact value of a physical constant). Variability, by contrast, represents true heterogeneity in a parameter across different experiments, biological systems, or environmental conditions, and it cannot be reduced with more data [15].

Q5: Why is a structured troubleshooting process important for resolving model errors? A structured process prevents wasted effort and ensures issues are resolved systematically. It transforms troubleshooting from a matter of intuition into a repeatable skill. This involves first understanding the problem, then isolating the root cause by changing one variable at a time, and finally implementing and verifying a fix [17] [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inconsistent Sensitivity Coefficients Across Model Runs

Symptoms: The calculated sensitivity coefficients for a given parameter vary significantly between repeated analyses, making it difficult to draw reliable conclusions.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Data Quality | Review the experimental data used to fit the model parameters for noise, outliers, or missing values. | Clean the dataset, repeat key experiments to improve data reliability, and consider using data smoothing techniques where appropriate. |

| Model Instability | Check if the model is highly sensitive to its initial conditions. Run the model from multiple starting points. | Reformulate unstable parts of the model, implement stricter convergence criteria for solvers, or switch to a more robust numerical integration method. |

| Incorrect Parameter Scaling | Verify if parameters with different physical units have been appropriately normalized before sensitivity analysis. | Recalculate coefficients after scaling all input parameters to a common, dimensionless range (e.g., from 0 to 1) to ensure a fair comparison. |

Issue: High Parameter Uncertainty Obscuring Analysis

Symptoms: The uncertainty ranges for your key parameters are so large that the results of the sensitivity analysis are inconclusive.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Parameter Identifiability | Perform an identifiability analysis to check if multiple parameter sets can produce an equally good fit to your experimental data. | Redesign experiments to capture dynamics that are specifically influenced by the non-identifiable parameters. |

| Inadequate Experimental Design | Determine if the experimental data was collected under conditions that effectively excite the model's dynamics related to the uncertain parameters. | Use optimal experimental design (OED) principles to plan new experiments that maximize information gain for the most uncertain parameters. |

| Need for Advanced Uncertainty Quantification | Check if you are relying solely on single-point estimates without propagating uncertainty. | Implement a Monte Carlo analysis, which involves running the model thousands of times with parameter values randomly sampled from their uncertainty distributions to build a full profile of output uncertainty [15]. |

Key Experimental Protocols and Data

Protocol: Partial Derivative-Based Dynamic Sensitivity Analysis

This methodology is adapted from advanced techniques used for dynamic model interpretation, such as in Non-linear Auto Regressive with Exogenous (NARX) models [16].

- Model Definition: Ensure your system's model is defined as a differentiable function of its parameters. For a parameter vector θ, the model output is y = f(θ).

- Compute Partial Derivatives: Calculate the partial derivative of the model output with respect to each parameter of interest. This gives the local sensitivity ( Si ) for parameter ( \thetai ): ( Si = \frac{\partial f(\mathbf{\theta})}{\partial \thetai} )

- Normalize Coefficients (Optional): To compare sensitivities across parameters with different units, compute normalized (relative) sensitivity coefficients: ( S{i, \text{relative}} = \frac{\partial f(\mathbf{\theta})}{\partial \thetai} \times \frac{\theta_i}{f(\mathbf{\theta})} )

- Dynamic Profiling: Repeat the calculation of ( S_i ) across the entire time-course of a dynamic simulation to understand how parameter sensitivity evolves over time.

- Validation: Where possible, validate the results against a brute-force method, such as the forward difference method, where you observe the output change from a small, deliberate perturbation of each parameter [16].

Quantitative Data on Sensitivity Analysis Methods

The table below summarizes core methods for assessing parameter sensitivity and uncertainty.

| Method | Key Principle | Best Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Local (Partial Derivative) | Calculates the local slope of the output with respect to an input parameter. | Quickly identifying key parameters in a well-defined operating region; dynamic sensitivity profiling [16]. |

| Global (Monte Carlo) | Propagates uncertainty by running the model many times with inputs from probability distributions. | Understanding the overall output uncertainty and interactions between parameters [15]. |

| Scenario Analysis | Evaluates model output under a defined set of "best-case" and "worst-case" parameter conditions. | Assessing the potential range of outcomes and the robustness of a conclusion [15]. |

| Pedigree Matrix | A systematic way to assign data quality scores and corresponding uncertainty factors based on expert judgment. | Estimating uncertainty when quantitative data is missing or incomplete, often used in life-cycle assessment [15]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Parameter Sensitivity Analysis |

|---|---|

| High-Throughput Screening Assays | Generate large, consistent datasets required for robust model fitting and sensitivity analysis across many experimental conditions. |

| Parameter Estimation Software | Tools to computationally determine the model parameters that best fit your experimental data, providing the baseline values for sensitivity analysis. |

| Uncertainty Quantification Libraries | Software packages (e.g., in Python or R) that provide built-in functions for performing Monte Carlo analysis and calculating advanced sensitivity indices. |

| Sensitivity Analysis Toolboxes | Integrated software tools designed to automate the calculation of various sensitivity measures, from simple partial derivatives to complex global indices. |

Visualized Workflows and Relationships

Workflow for Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

Implementing Sensitivity Analysis for NPDOA: Methods and Real-World Applications in Drug Development

Sensitivity Analysis (SA) is fundamentally defined as "the study of how uncertainty in the output of a model can be apportioned to different sources of uncertainty in the model input" [19]. Within the context of New Product Development and Optimization in Analytics (NPDOA) parameter research, particularly in drug development, this translates to understanding how variations in model parameters—such as pharmacokinetic properties, clinical trial design parameters, or manufacturing variables—affect critical outcomes like efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness. SA is distinct from, yet complementary to, uncertainty analysis; while uncertainty analysis quantifies the overall uncertainty in model predictions, SA identifies which input factors contribute most to this uncertainty [20]. This is crucial for building credible models, making reliable inferences, and informing robust decisions in high-stakes environments like pharmaceutical development [19].

Historically, SA techniques fall into two broad categories: local and global [19] [20]. Local methods, such as One-at-a-Time (OAT), explore the model's behavior around a specific reference point in the input space. In contrast, global methods, such as variance-based approaches, vary all input factors simultaneously across their entire feasible space, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the model's behavior, including interaction effects between parameters [19]. For nonlinear models typical of complex biological and economic systems in drug development, global sensitivity analysis is generally preferred, as local methods can produce misleading results [19] [21].

Core Methodologies: From Local to Global

Local Sensitivity Analysis Methods

One-at-a-Time (OAT) The OAT approach is one of the simplest and most intuitive SA methods [20].

- Protocol: It involves starting from a baseline set of input values (e.g., nominal parameter values). One input factor is then varied while all other factors are held constant at their baseline values. The process is repeated for each input factor of interest [20].

- Sensitivity Measure: The change in model output is observed for each variation. Sensitivity can be measured by monitoring changes in the output, for example, by calculating partial derivatives or through linear regression on the data points generated [20].

- Key Characteristics:

- Advantages: Practical, easy to implement and interpret, and computationally inexpensive. If a model fails during an OAT run, the responsible input factor is immediately identifiable [20].

- Limitations: It does not fully explore the input space and cannot detect interactions between input variables. It is unsuitable for nonlinear models because the results are valid only at the chosen reference point and do not account for the influence of other varying parameters [19] [20]. The proportion of the input space it explores shrinks superexponentially as the number of inputs increases [20].

Derivative-Based Local Methods These methods are based on the partial derivatives of the output with respect to an input factor.

- Protocol: The partial derivative of the output (Y) with respect to an input factor (X_i) is computed, typically at a fixed point in the input space (e.g., the baseline or nominal values), denoted as (x^0) [20].

- Sensitivity Measure: The absolute value or square of the partial derivative, (\left| \frac{\partial Y}{\partial Xi} \right|{x^0}), is used as a local sensitivity measure [20].

- Key Characteristics:

- Advantages: Computationally efficient, especially when using adjoint modelling or Automated Differentiation, which can compute all partial derivatives at a cost only several times that of a single model evaluation. They allow for the creation of a sensitivity matrix that provides a system overview [20].

- Limitations: Like OAT, they are local and do not explore the entire input space. Their effectiveness is limited for nonlinear models and they do not account for interactions [20].

OAT Analysis Workflow

Global Sensitivity Analysis Methods

Global methods are designed to overcome the limitations of local approaches by varying all factors simultaneously over their entire range of uncertainty [19].

Variance-Based Methods Variance-based methods, often considered the gold standard for global SA, decompose the variance of the output into portions attributable to individual inputs and their interactions [19].

- Protocol: These methods require a sampling strategy that covers the entire input space, often using Monte Carlo or quasi-Monte Carlo sequences. The model is executed repeatedly for different combinations of input values drawn from their defined probability distributions [20].

- Sensitivity Measures: The key measures are the first-order (or main effect) Sobol' index and the total-order Sobol' index [19].

- The first-order index ((Si)) measures the fractional contribution of an input factor (Xi) to the variance of the output (Y), without accounting for interactions with other factors. It is formally defined as (Si = \frac{V[E(Y|Xi)]}{V(Y)}), where (V[E(Y|X_i)]) is the variance of the conditional expectation [19].

- The total-order index ((S{Ti})) measures the total contribution of (Xi) to the output variance, including all its interactions with other factors [19].

- Key Characteristics:

- Advantages: They provide a complete and intuitive description of sensitivity, capturing both main effects and interaction effects. They are model-free, meaning they work for any model, regardless of linearity or additivity [19].

- Limitations: They are computationally demanding, often requiring thousands of model runs to achieve stable estimates of the indices, which can be prohibitive for very complex, time-consuming models [20].

Screening Methods (Morris Method) The Morris method, also known as the method of elementary effects, is an efficient global screening technique for models with many parameters [20].

- Protocol: It is a so-called "one-at-a-time" design, but it is applied globally. It computes elementary effects by taking repeated steps along the various parametric axes at different points in the input space. The mean ((\mu)) and standard deviation ((\sigma)) of these elementary effects are then calculated for each factor [20].

- Sensitivity Measures: The mean ((\mu)) estimates the overall influence of the factor on the output. The standard deviation ((\sigma)) indicates whether the factor is involved in interactions with other factors or has nonlinear effects [20].

- Key Characteristics:

- Advantages: It is far more efficient than variance-based methods, requiring significantly fewer model evaluations (typically tens per factor), making it suitable for initial screening to identify the most important factors in high-dimensional problems [20].

- Limitations: It provides qualitative rankings ((\mu) and (\sigma)) rather than exact variance decompositions. It is less accurate for quantifying the precise contribution to output variance compared to Sobol' indices [20].

Global SA Methodology Selection

Comparative Analysis of Sensitivity Analysis Methods

The table below provides a structured comparison of the key SA methods discussed, highlighting their primary use cases and characteristics.

| Method | Analysis Type | Key Measures | Handles Interactions? | Computational Cost | Primary Use Case in NPDOA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-at-a-Time (OAT) | Local | Partial derivatives, finite differences | No [20] | Low | Initial, quick checks; simple models [20] |

| Derivative-Based | Local | (\left| \frac{\partial Y}{\partial X_i} \right|) | No | Low to Moderate | Local gradient analysis; system overview matrices [20] |

| Morris Method | Global | Mean (μ) and Std. Dev. (σ) of elementary effects | Yes (indicated by σ) [20] | Moderate | Factor screening for models with many parameters [20] |

| Variance-Based (Sobol') | Global | First-order ((Si)) and total-order ((S{Ti})) indices | Yes (explicitly quantified) [19] | High | In-depth analysis for key parameters; quantifying interactions [19] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for SA

Implementing a robust sensitivity analysis requires both conceptual and practical tools. The following table lists key "research reagents" – essential materials and software components – for conducting SA in an NPDOA context.

| Item / Reagent | Function / Explanation | Example Tools / Implementations |

|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty Quantification Framework | Defines the input space by specifying plausible ranges and probability distributions for all uncertain parameters, a foundational step before SA [19] [20]. | Expert elicitation, literature meta-analysis, historical data analysis. |

| Sampling Strategy | Generates a set of input values for model evaluation. The design of experiments is critical for efficiently exploring the input space [19] [20]. | Monte Carlo, Latin Hypercube Sampling, Quasi-Monte Carlo sequences (Sobol' sequences). |

| SA Core Algorithm | The computational engine that calculates the chosen sensitivity indices from the model's input-output data. | R (sensitivity package), Python (SALib library), MATLAB toolboxes. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) / Meta-models | Addresses the challenge of computationally expensive models. HPC speeds up numerous model runs, while meta-models (surrogates) are simplified, fast-to-evaluate approximations of the original complex model [20]. | Cloud computing clusters; Gaussian Process emulators, Polynomial Chaos Expansion, Neural Networks. |

| Visualization & Analysis Suite | Creates plots and tables to interpret and communicate SA results effectively, such as scatter plots, tornado charts, and index plots [20]. | Python (Matplotlib, Seaborn), R (ggplot2), commercial dashboard software (Tableau). |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: When should I use a local method like OAT instead of a global method? A1: OAT should be used sparingly. It is only appropriate for a preliminary, rough check of a model's behavior around a baseline point, or for very simple, linear models where interactions are known to be absent. For any model used for substantive analysis or decision-making, particularly in a regulatory context like drug development, a global method is strongly recommended. A systematic review revealed that many published studies use SA poorly, often relying on OAT for nonlinear models where it is invalid [21].

Q2: My model is very slow to run. How can I perform a variance-based SA that requires thousands of evaluations? A2: This is a common challenge. You have two primary strategies:

- Screening: First, use an efficient screening method like the Morris method to identify the subset of factors that have non-negligible effects. You can then perform a full variance-based analysis on this reduced set of factors, dramatically lowering the computational cost [20].

- Meta-modelling: Build a statistical surrogate model (e.g., a Gaussian Process emulator or a polynomial model) that approximates your original complex model. These surrogate models are fast to evaluate, allowing you to perform the thousands of runs needed for variance-based SA on the surrogate instead [20].

Q3: In my variance-based SA, what is the difference between the first-order and total-order indices, and how should I interpret them? A3:

- The First-Order Index ((Si)) measures the *main effect* of (Xi) on the output variance. A high (Si) means (Xi) is important by itself.

- The Total-Order Index ((S{Ti})) measures the *total effect* of (Xi), including all its interactions with all other input factors.

Interpretation Guide:

- If (Si \approx S{Ti}): The factor (X_i) is primarily additive and has little involvement in interactions.

- If (S{Ti} > Si): The factor (Xi) is involved in interactions with other factors. The difference ((S{Ti} - S_i)) quantifies the variance caused by these interactions [19].

- For Factor Prioritization, focus on factors with high (S_{Ti}) – these are the ones that, if determined precisely, would reduce the output variance the most.

- For Factor Fixing, a factor with a very low (S_{Ti}) (close to zero) can be fixed to a nominal value without significantly affecting the output variability [19].

Q4: How do I handle correlated inputs in my sensitivity analysis? A4: Most standard SA methods, including OAT and classic variance-based methods, assume input factors are independent. If inputs are correlated, applying these methods can yield incorrect results [20]. This is an advanced topic. Methods to address correlations include:

- Using sampling techniques that preserve the correlation structure of the inputs.

- Employing SA methods specifically designed for correlated inputs, which may involve more complex statistical approaches. It is crucial to acknowledge this limitation and seek expert statistical guidance if strong correlations exist among your model inputs.

Advanced Topics: Integrating SA into the NPDOA Workflow

Sensitivity analysis is not a one-off task but an integral part of the model development and decision-making lifecycle. In NPDOA, SA can be applied in several distinct modes, as outlined in the table below [19].

| SA Mode | Core Question | Application in Drug Development | Recommended Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Prioritization | Which uncertain factors, if determined, would reduce output variance the most? [19] | Identifying which pharmacokinetic parameter (e.g., clearance, volume of distribution) warrants further precise measurement to reduce uncertainty in dose prediction. | Variance-Based (Total-order index) |

| Factor Fixing (Screening) | Which factors have a negligible effect and can be fixed to a nominal value? [19] | Simplifying a complex disease progression model by fixing non-influential patient demographic parameters to reduce model complexity. | Morris Method or Variance-Based (Total-order index) |

| Factor Mapping | Which regions of the input space lead to a desired (or undesired) model behavior? [19] | Identifying the combination of drug efficacy and safety tolerance thresholds that lead to a favorable risk-benefit profile. | Monte Carlo Filtering, Scenario Discovery |

SA in the Modeling Workflow

A Novel OAT Method for Drug Target Identification in Signaling Pathways

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core principle behind the Novel OAT (One-At-a-Time) Sensitivity Analysis method for finding drug targets? A1: This method is designed to find a single model parameter (representing a specific biochemical process) whose targeted change significantly alters a defined cellular response. It systematically reduces each kinetic parameter in a signaling pathway model, one at a time, to simulate the effect of pharmacological inhibition. The parameters that cause the largest, biologically desired change in the system's output (e.g., prolonged high p53 levels to promote apoptosis) when decreased are ranked highest, pointing to the most promising processes for drug targeting [22].

Q2: How does the OAT sensitivity analysis method handle the issue of cellular heterogeneity in drug response? A2: The method incorporates a specific parameter randomization procedure that is tailored to the model's application. This allows the researcher to tackle the problem of heterogeneity in how individual cells within a population might respond to a drug, providing a more robust prediction of potential drug targets [22].

Q3: My experimental validation shows that inhibiting a top-ranked target has a weaker effect than predicted. What could be the reason? A3: This discrepancy often arises from compensatory mechanisms within the network. Signaling pathways often contain redundant elements or parallel arms. If a top-ranked process is inhibited, a parallel pathway or a related transporter (e.g., OAT3 may compensate for the loss of OAT1, and vice-versa) might maintain the system's function, dampening the overall therapeutic effect [23] [24]. It is recommended to investigate the potential for simultaneous inhibition of multiple high-ranking targets.

Q4: What are the advantages of using chemical proteomics for target identification of natural products, and how does it relate to this method? A4: Chemical proteomics is an unbiased, high-throughput approach that can comprehensively identify multiple protein targets of a small molecule (like a natural product) at the proteome level [25]. It can be considered a complementary experimental strategy. The novel OAT method uses computational models to predict which processes are the best targets, and subsequently, chemical proteomics can be employed to experimentally identify the actual molecules that interact with a drug candidate designed to hit that predicted target [22] [25].

Q5: Why is a double-knockout model necessary for studying OAT1 and OAT3 functions? A5: OAT1 and OAT3 have a significant overlap in their substrate spectra and can functionally compensate for each other. Knocking out only one of them often does not result in a strong phenotypic change in the excretion of organic anionic substrates. A Slc22a6/Slc22a8 double-knockout model is required to truly abolish this transport function and observe substantial changes in drug pharmacokinetics or metabolite handling [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Correlation Between Model Predictions and Wet-Lab Results

This is a common challenge when translating in silico findings to the laboratory.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Over-simplified model | Compare model structure to recent literature on pathway crosstalk. | Incorporate additional regulatory feedback loops or crosstalk with other pathways known from experimental data. |

| Incorrect nominal parameter values | Perform a literature review to ensure kinetic parameters are accurate for your specific cellular context. | Re-estimate parameters using new experimental data or employ global sensitivity analysis to identify the most influential parameters. |

| Off-target effects in validation | Use a CRISPR/Cas9-generated knockout model to ensure target specificity, rather than relying solely on pharmacological inhibitors [23]. | Validate findings using multiple, distinct inhibitors or genetic knockout models. |

Issue: Low Confidence in Parameter Ranking

This occurs when the sensitivity analysis does not clearly distinguish the most important parameters.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inappropriate sensitivity metric | Check if the chosen model output (e.g., AUC, peak value) truly reflects the desired therapeutic outcome. | Test multiple biologically relevant outputs (e.g., duration, amplitude, time-to-peak) for sensitivity analysis. |

| High parameter interdependence | Use a global sensitivity analysis method (e.g., varying all parameters simultaneously with multivariable regression) to detect interactions [26]. | Complement the OAT analysis with a global method like the regression-based approach used for stochastic models [26]. |

| Unaccounted for stochasticity | For systems with small molecule counts (e.g., single-cell responses), run stochastic simulations instead of deterministic ones. | Adopt a sensitivity analysis framework designed for stochastic models, which uses regression on many random parameter sets to relate parameters to outputs [26]. |

Experimental Protocols

Core Protocol: Novel OAT Sensitivity Analysis for Drug Target Identification

This protocol outlines the key steps for applying the novel OAT method to a mathematical model of a signaling pathway to identify potential drug targets [22].

1. Model Selection and Preparation:

- Select a mechanistic ordinary differential equation (ODE) model that accurately describes the dynamics of your signaling pathway of interest.

- Define a therapeutically relevant model output (e.g., concentration of phosphorylated p53). This output should be a variable whose change aligns with a desired therapeutic outcome.

2. Parameter Selection and Perturbation:

- From the model, select kinetic parameters that represent biochemical processes susceptible to pharmacological inhibition (e.g., reaction rates).

- Exclude fixed constants like Michaelis-Menten coefficients.

- For each parameter ( p_i ), run a simulation where its nominal value is reduced (e.g., by 50% or 75%) to simulate drug-induced inhibition, while all other parameters are held at their nominal values.

3. Sensitivity Calculation and Ranking:

- For each simulation, calculate a sensitivity index that quantifies the change in the therapeutically relevant output. This could be the area under the curve (AUC) of the output's time course or its maximum value.

- Rank all parameters based on the absolute value of their sensitivity index. Parameters whose reduction leads to the largest desired change in the output are ranked highest.

4. Biological Interpretation and Target Prioritization:

- Map the highest-ranking parameters back to the specific biochemical processes they represent (e.g., "Mdm2 transcription rate").

- The molecules involved in these top-ranked processes (e.g., the enzyme or transcription factor) are your candidate molecular drug targets.

The workflow can be visualized as follows:

Supporting Protocol: Target Validation using a Double-Knockout Model

This protocol describes the use of a CRISPR/Cas9-generated double-knockout model to validate the role of OAT1 and OAT3 in drug disposition, which can be adapted for targets identified in signaling pathways [23].

1. Animal Model Generation:

- Design single guide RNA (sgRNA) sequences targeting critical exons of the genes of interest (e.g., Slc22a6 for OAT1 and Slc22a8 for OAT3).

- Co-inject the sgRNA-Cas9 complexes into fertilized rat eggs using microinjection.

- Transplant the surviving embryos into pseudo-pregnant females to generate founder (F0) animals.

2. Genotype Identification and Breeding:

- Extract DNA from founder animals and perform PCR and sequencing to identify individuals with successful knockout alleles.

- Breed heterozygous animals to generate wild-type (WT), heterozygous (HET), and homozygous knockout (KO) offspring for the study.

3. Functional Validation:

- In knockout models, use quantitative PCR (qPCR) to confirm the absence of target mRNA expression in relevant tissues (e.g., kidney).

- Perform pharmacokinetic studies. Administer a prototype substrate drug (e.g., Furosemide or p-aminohippuric acid for OATs) to WT and KO animals.

- Measure the drug concentration in blood and urine over time. A substantial decrease in renal clearance in the KO animals confirms the critical role of the targeted transporters in the drug's elimination.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table lists key reagents and their applications in the described methodologies.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 System [23] | Generation of highly specific single- or double-gene knockout animal models (e.g., OAT1/OAT3 KO rats) for target validation. | Offers high specificity, efficiency, and the ability to edit multiple genes simultaneously. |

| Chemical Proteomics Probes [25] | Experimental identification of protein targets for small molecule drugs or natural products. Typically consist of a reactive drug derivative, a linker, and a tag (e.g., biotin) for enrichment. | The probe must retain the pharmacological activity of the parent molecule to ensure accurate target identification. |

| p-Aminohippuric Acid (PAH) [24] | Classic prototypical substrate used to experimentally define and probe the function of the organic anion transporter (OAT) pathway, particularly OAT1. | Used for decades as a benchmark for organic anion transport studies in kidney physiology and pharmacology. |

| Probenecid [24] | Classic, broad-spectrum inhibitor of OAT-mediated transport. Used experimentally to confirm OAT involvement in a drug's transport. | A standard tool for operationally defining the classical organic anion transport system, though it is not specific to a single OAT isoform. |

| Slc22a6/Slc22a8 Double-Knockout Rat Model [23] | A preferred in vivo model for studying the integrated physiological and pharmacological roles of OAT1 and OAT3 without functional compensation. | More pharmacologically relevant than single knockouts for studying the clearance of shared substrates. |

Signaling Pathway & Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of analyzing a signaling pathway, from model construction to target identification, integrating both computational and experimental phases.

This guide provides technical support for researchers applying sensitivity analysis to identify molecular drug targets in biological systems. The p53/Mdm2 regulatory module serves as a case study, demonstrating how computational methods can prioritize parameters for therapeutic intervention. These methodologies are particularly relevant for thesis research on Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) parameter sensitivity, as similar mathematical principles apply to analyzing complex, nonlinear systems.

Technical FAQs and Troubleshooting

General Sensitivity Analysis Concepts

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between local and global sensitivity analysis methods in biological modeling?

Local methods (One-at-a-Time or OAT) change a single parameter while keeping others fixed, ideal for identifying specific drug targets that selectively alter single processes [22]. Global methods vary all parameters simultaneously to explore interactions but are computationally intensive [22]. For drug target identification where drugs bind selectively to single targets, OAT approaches are often most appropriate [22].

Q2: How does sensitivity analysis for drug discovery differ from traditional engineering applications?

Biological sensitivity analysis must account for therapeutic intent—whether increasing or decreasing kinetic parameters provides therapeutic benefit [22]. It also addresses cellular response heterogeneity using parameter randomization procedures tailored to biological applications [22]. The goal is identifying processes where pharmacological alteration (represented by parameter changes) significantly alters cellular responses toward therapeutic outcomes [22].

Methodology and Experimental Design

Q3: What are the critical steps in designing a sensitivity analysis experiment for target identification?

- Define Therapeutic Objective: Determine which system output variable represents the desired therapeutic state

- Select Analysis Method: Choose OAT for targeted interventions or global methods for system-level understanding

- Establish Parameter Range: Define biologically plausible parameter variation ranges

- Compute Sensitivity Indices: Quantify how parameter changes affect output variables

- Rank Parameters: Identify parameters whose alteration most efficiently drives system toward therapeutic state [22]

Q4: How do I determine which system output to monitor for drug target analysis?

Select output variables representing clinically relevant phenotypes. For the p53 system, phosphorylated p53 (p53PN) level was chosen as it directly correlates with apoptosis induction, a desired cancer therapeutic outcome [22]. Choose outputs with clear biological significance to your disease context.

Technical Implementation

Q5: What computational tools are available for implementing sensitivity analysis?

While specific tools weren't detailed in the research, the mathematical framework involves:

- Ordinary differential equation models of signaling pathways

- Parameter variation algorithms

- Sensitivity index calculation methods

- Statistical analysis of cellular response heterogeneity [22]

Q6: How should parameter variations be scaled in biological sensitivity analysis?

Parameter variations should reflect biologically plausible ranges, typically determined from experimental literature. For drug target identification, variations should represent achievable therapeutic modulation levels.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Insensitive Parameter Ranking

Symptoms: Sensitivity analysis fails to identify parameters that significantly alter system output.

Solutions:

- Verify parameter variations span biologically relevant ranges

- Check that output variable accurately reflects therapeutic objective

- Confirm system nonlinearities aren't masking parameter effects