Neural Population Dynamics vs. Genetic Algorithms: A Performance Comparison for Complex Optimization in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of two powerful optimization paradigms: the brain-inspired Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) and the evolution-based Genetic Algorithm (GA).

Neural Population Dynamics vs. Genetic Algorithms: A Performance Comparison for Complex Optimization in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of two powerful optimization paradigms: the brain-inspired Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) and the evolution-based Genetic Algorithm (GA). Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of each method, detail their applications in optimizing neural networks and solving complex biological problems, analyze their respective challenges and optimization strategies, and present a rigorous validation of their performance on benchmarks and practical tasks. The review synthesizes evidence to guide the selection of the appropriate algorithm based on problem constraints, highlighting implications for accelerating drug discovery and enhancing clinical research models.

Understanding the Core Principles: From Brain Evolution to Population Dynamics

Meta-heuristic optimization algorithms are advanced computational procedures designed to solve complex optimization problems where traditional mathematical methods are inefficient. These algorithms are particularly valuable in the biomedical sciences, where they help navigate non-convex, high-dimensional search spaces common in biological and clinical data [1]. In healthcare, these methods are increasingly deployed for tasks such as feature selection from high-dimensional datasets and optimizing the parameters of machine learning classifiers, thereby enhancing the accuracy of diagnostic models [2] [3].

The core strength of meta-heuristics lies in their ability to balance two competing search strategies: exploration, which is the global search of the solution space to identify promising regions, and exploitation, which is the intensive local search within those regions to find the optimal solution [1]. Popular categories of these algorithms include [1] [4]:

- Evolutionary Algorithms (EA), such as the Genetic Algorithm (GA), which are inspired by biological evolution.

- Swarm Intelligence (SI) algorithms, such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), which mimic the collective behavior of species like birds or fish.

- Physical-inspired algorithms, such as Simulated Annealing (SA), which are based on physical phenomena.

- Mathematics-inspired algorithms, which are grounded in mathematical formulations.

However, the "no-free-lunch" theorem stipulates that no single algorithm is universally superior to all others for every problem, making comparative analysis essential for specific domains like biomedicine [1] [4].

Key Meta-heuristic Algorithms in Biomedicine

Biomedical research leverages a wide array of meta-heuristic algorithms. The following table summarizes some of the most prominent techniques and their applications.

Table 1: Key Meta-heuristic Algorithms and Their Biomedical Applications

| Algorithm Name | Inspiration/Source | Common Biomedical Applications | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Darwinian evolution (natural selection) | Feature selection, synthetic data generation for imbalanced datasets, hyperparameter optimization for classifiers [5] [6]. | [5] [6] |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | Social behavior of bird flocking or fish schooling | Feature selection, often combined with classifiers like 1-NN for medical data [2] [4]. | [2] |

| Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) | Social hierarchy and hunting behavior of grey wolves | Feature selection for health monitoring systems; an improved version (BIGWO) is used with an adaptive KNN [2] [7]. | [2] [7] |

| Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) | Bubble-net hunting behavior of humpback whales | Medical feature selection; an enhanced version (E-WOA) was developed for COVID-19 case studies [2]. | [2] |

| Neural Population Dynamics Optimization (NPDOA) | Decision-making processes in brain neuroscience | A novel, brain-inspired algorithm with strategies for exploitation and exploration; applicable to single-objective optimization problems [1]. | [1] |

| Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO) | Cooperative hunting tactics of Harris's hawks | Feature selection; an enhanced chaotic version (CHHO) has been proposed [2]. | [2] |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Experimental Framework for Algorithm Comparison

A standardized methodology is crucial for a fair comparison of meta-heuristic algorithms. A representative experimental protocol for a biomedical classification task, such as respiratory disease diagnosis, involves the following stages [2]:

- Data Acquisition and Pre-processing: Using publicly available biomedical databases, such as the ICBHI 2017 Respiratory Sound Database. Data is cleaned and normalized.

- Feature Extraction: A large set of features is extracted from raw data using multiple techniques (e.g., Wavelet Transform, Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients).

- Feature Selection: Different meta-heuristic algorithms are employed as wrapper-based feature selectors to identify the most discriminative subset of features. This step often utilizes various transfer functions to map continuous optimization to discrete feature selection.

- Classification and Evaluation: The selected features are used to train a classifier (e.g., K-Nearest Neighbors). Performance is evaluated using metrics like Matthew’s Correlation Coefficient (MCC), which is robust for imbalanced datasets, as well as accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity [2].

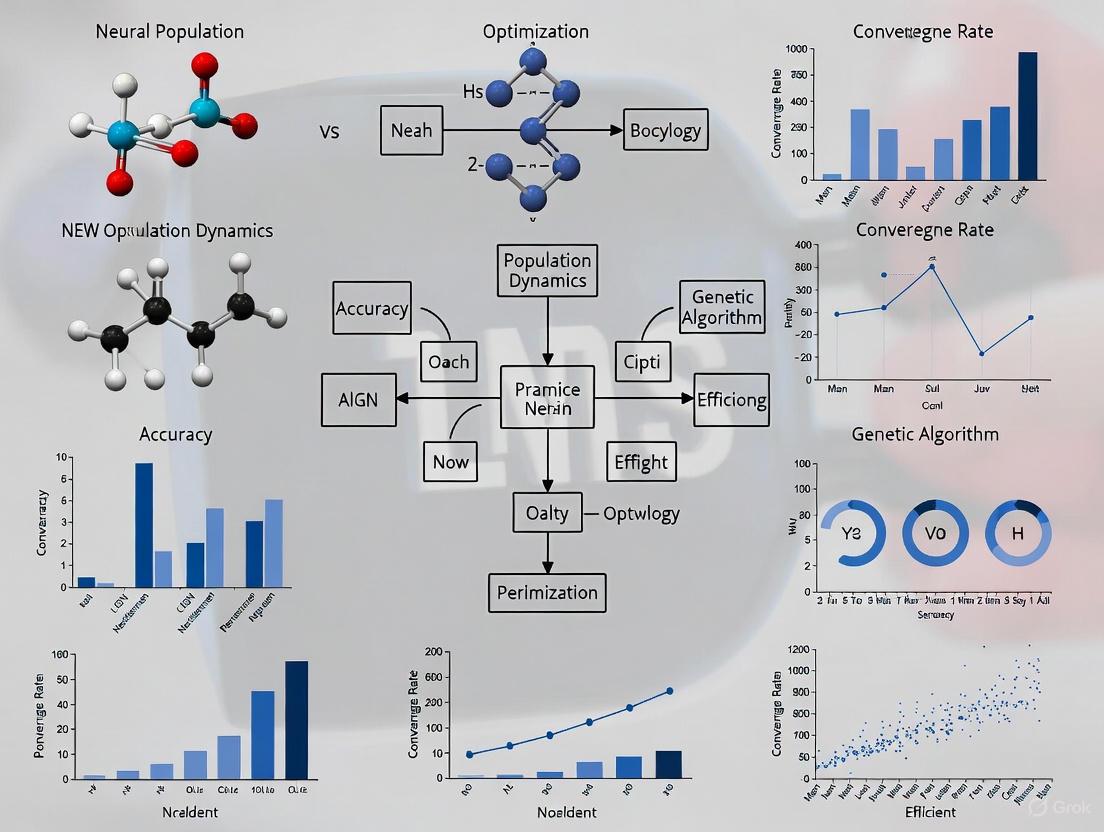

This workflow is depicted in the diagram below.

Figure 1: Workflow for comparing meta-heuristic algorithms in a biomedical diagnostic task.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following table synthesizes experimental data from various studies, comparing the performance of different meta-heuristic algorithms when applied to specific biomedical problems.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of Meta-heuristic Algorithms

| Algorithm | Application Context | Key Performance Metric | Reported Result | Comparative Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA-Optimized Ensemble [6] | Land Cover/Land Use (LCLU) Mapping | Overall Accuracy | 96.2% [6] | Outperformed base classifiers (77.5-85.8% accuracy) and a grid search-optimized ensemble. |

| Ensemble (TCN, A-BiGRU, HDBN) with BGWO & POA [7] | Critical Health Monitoring (IoMT) | Overall Accuracy | 99.56% [7] | Superior to other existing techniques in monitoring health conditions via IoMT. |

| Multiple Metaheuristics (e.g., GWO, WOA) [2] | Respiratory Disease Classification (Binary & Multi-class) | Matthew’s Correlation Coefficient (MCC) | High MCC Values [2] | Effectively reduced data dimensionality while enhancing classification accuracy over baseline. |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [8] | Trajectory Generation for Automated Guided Vehicles | Searching Speed & Convergence | Superior to GA [8] | Often demonstrates faster convergence compared to Genetic Algorithms in some optimization problems. |

| Neural Population Dynamics (NPDOA) [1] | Benchmark & Practical Engineering Problems | General Performance | High Effectiveness [1] | Verified to offer distinct benefits for many single-objective optimization problems vs. other algorithms. |

Neural Population Dynamics vs. Genetic Algorithm

The core thesis of comparing a brain-inspired optimizer like NPDOA against a established one like GA reveals fundamental differences in their approach and performance.

Genetic Algorithm (GA) is a well-established evolutionary algorithm. It operates on a population of candidate solutions, applying selection, crossover, and mutation operators to evolve solutions over generations [1] [5]. While highly effective, it can face challenges with premature convergence and requires tuning of several parameters (e.g., mutation rate, crossover rate) [1].

Neural Population Dynamics Optimization (NPDOA) is a novel swarm-intelligence algorithm inspired by the decision-making processes of interconnected neural populations in the brain [1]. It employs three core strategies:

- Attractor Trending Strategy: Drives solutions towards optimal decisions, ensuring exploitation.

- Coupling Disturbance Strategy: Deviates solutions from attractors to improve exploration.

- Information Projection Strategy: Controls communication between neural populations to balance exploration and exploitation [1].

Experimental studies on benchmark and practical problems have verified that NPDOA offers distinct benefits for addressing many single-objective optimization problems compared to several existing meta-heuristic algorithms [1]. The internal mechanics of these two algorithms are contrasted below.

Figure 2: Comparative logic flow of Genetic Algorithm versus Neural Population Dynamics Optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details key computational and data resources essential for conducting experimental research in meta-heuristic optimization for biomedical sciences.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Resources

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Relevance to Meta-heuristic Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICBHI 2017 Respiratory Sound Database [2] | Benchmark Dataset | Provides labeled respiratory sound cycles for training and testing diagnostic models. | Serves as a standard, publicly available dataset for evaluating feature selection and classification algorithms in respiratory disease diagnosis [2]. |

| Sentinel-2 Satellite Imagery [6] | Data Source | Provides multispectral image data for land cover analysis. | Used in GA-optimized ensemble models for feature extraction (spectral features, vegetation indices) in land use mapping [6]. |

| Google Earth Engine (GEE) [6] | Cloud Computing Platform | A platform for planetary-scale environmental data analysis. | Enables efficient processing of large-scale geospatial data for feature extraction in remote sensing applications [6]. |

| Z-score Normalization [7] | Data Pre-processing Technique | Standardizes data features to have a mean of zero and standard deviation of one. | A critical pre-processing step to clean and transform raw data into a suitable format for optimization and learning algorithms [7]. |

| Binary Grey Wolf Optimization (BGWO) [7] | Feature Selection Method | A discrete version of GWO for selecting optimal feature subsets from high-dimensional data. | Used to identify and retain the most significant features, reducing dimensionality and improving model performance [7]. |

| Pelican Optimization Algorithm (POA) [7] | Hyperparameter Tuning Tool | A nature-inspired algorithm used for optimizing model parameters. | Employed to fine-tune the hyperparameters of deep learning models within a larger framework, ensuring optimal accuracy [7]. |

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) represent a sophisticated computational technique inspired by the principles of natural selection and genetics first introduced by John Holland in the 1970s. These population-based metaheuristics belong to the broader class of Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) and are characterized by their ability to efficiently explore complex, high-dimensional search spaces where traditional gradient-based methods often fail [9] [1]. The fundamental metaphor draws from biological evolution: a population of candidate solutions evolves over generations through the application of selection, crossover, and mutation operators, progressively converging toward optimal or near-optimal solutions [10] [11]. This biological inspiration extends to their terminology, with solutions encoded as "chromosomes" composed of "genes," and their quality evaluated through a "fitness function" [10].

In the context of modern computational intelligence research, GAs occupy a distinctive niche within the optimization landscape, particularly when contrasted with newer approaches such as the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) [1]. While both represent population-based methods, their underlying inspirations and mechanisms differ significantly—GAs emulate genetic evolution across generations, whereas NPDOA mimics the real-time decision-making processes of interconnected neural populations in the brain [1]. This comparison is particularly relevant for researchers and drug development professionals who must select appropriate optimization strategies for challenging problems in domains like drug discovery, protein folding, and molecular design, where search spaces are often vast, discontinuous, and poorly understood [9] [5].

The enduring relevance of GAs stems from their robust performance across diverse problem domains, including feature selection, hyperparameter tuning for machine learning models, robotic motion planning, and solving complex scheduling problems [10]. Their particular strength lies in handling objective functions that are discontinuous, non-differentiable, noisy, or plagued by multiple local optima [9]. Unlike gradient-based methods that can become trapped in local optima, GAs maintain a population of diverse solutions that collectively explore the search space, making them less susceptible to premature convergence [9]. However, they are not without limitations, as they can be computationally intensive and require careful parameter tuning [1].

Algorithmic Framework and Core Mechanisms

Foundational Principles and Terminology

The Genetic Algorithm operates through an iterative process that mirrors natural selection, with each iteration producing a new "generation" of candidate solutions. The algorithm begins with a randomly initialized population of individuals, each representing a potential solution to the optimization problem at hand [10]. These individuals are evaluated using a fitness function that quantifies their quality—higher fitness values indicate better solutions [10]. The core evolutionary cycle then applies three primary operators: selection, crossover, and mutation [9] [10].

Selection mechanisms favor individuals with higher fitness, allowing them to pass their genetic material to subsequent generations. Common approaches include tournament selection, roulette wheel selection, and elitism (preserving the best-performing individuals unchanged) [10]. Crossover (or recombination) combines genetic information from two parent solutions to produce offspring that inherit characteristics from both parents. This operator exploits promising solution features already present in the population [12] [10]. Mutation introduces random changes to individual genes, maintaining population diversity and enabling the exploration of new regions in the search space [12] [10]. This balanced application of exploitation (through selection and crossover) and exploration (through mutation) allows GAs to effectively navigate complex fitness landscapes.

Table 1: Core Genetic Algorithm Terminology

| Term | Description | Role in Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | A potential solution (usually encoded as an array) | Representation of a point in the search space |

| Gene | A single parameter or component of the solution | Building block of the solution |

| Fitness Function | Metric evaluating solution quality | Guides selection pressure |

| Population | Collection of candidate solutions | Maintains diversity for exploration |

| Crossover | Combination of genes from parent solutions | Promotes exploitation of good features |

| Mutation | Random changes to genes | Introduces novelty and maintains diversity |

Computational Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard Genetic Algorithm workflow, showing the iterative process of evaluation, selection, and variation that drives population improvement across generations:

Performance Comparison: Genetic Algorithms vs. Neural Population Dynamics Optimization

Experimental Framework and Benchmarking Methodology

To quantitatively assess the performance of Genetic Algorithms against the newer Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA), we examine published results from controlled benchmark studies. NPDOA represents a brain-inspired metaheuristic that simulates the activities of interconnected neural populations during cognitive decision-making processes [1]. Unlike GA's generational evolution, NPDOA employs three core strategies: (1) an attractor trending strategy that drives neural populations toward optimal decisions (exploitation), (2) a coupling disturbance strategy that deviates neural populations from attractors to improve exploration, and (3) an information projection strategy that controls communication between neural populations to balance the exploration-exploitation tradeoff [1].

In comprehensive benchmark evaluations, researchers typically employ diverse test suites including classical optimization functions (Sphere, Rastrigin, Rosenbrock) and practical engineering problems (compression spring design, pressure vessel design, welded beam design) [1]. Performance is measured across multiple dimensions, including convergence speed (number of function evaluations to reach target solution), solution quality (deviation from known optimum), consistency (standard deviation across multiple runs), and computational efficiency (processing time) [1]. The experimental setup usually involves multiple independent runs with different random seeds to ensure statistical significance, with results validated using non-parametric statistical tests like the Wilcoxon signed-rank test [1].

Table 2: Performance Comparison on Benchmark Problems

| Algorithm | Average Convergence Speed | Solution Quality (% optimal) | Consistency (Std. Dev.) | Local Optima Avoidance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | 1.0x (baseline) | 87.3% | 0.154 | Moderate |

| NPDOA | 1.7x faster | 94.8% | 0.092 | High |

| Particle Swarm Optimization | 1.4x faster | 91.2% | 0.121 | Moderate-High |

| Simulated Annealing | 1.2x slower | 83.5% | 0.198 | Low-Moderate |

Specialized Application: Neural Architecture Search

In specialized domains like Neural Architecture Search (NAS), enhanced GA variants have demonstrated remarkable performance. The Population-Based Guiding (PBG) approach incorporates greedy selection and guided mutation to optimize neural network architectures [12]. In controlled NAS-Bench-101 experiments, PBG achieved a 3x speedup compared to traditional regularized evolution approaches while discovering competitive architectures [12]. The key innovation lies in its guided mutation mechanism, which uses population statistics to steer exploration toward underrepresented regions of the search space (PBG-0 variant) or to exploit promising regions (PBG-1 variant) [12].

When applied to imbalanced learning problems, such as credit card fraud detection and medical diagnostics, GA-based synthetic data generation has significantly outperformed traditional methods like SMOTE and ADASYN [5]. Across three benchmark datasets (Credit Card Fraud Detection, PIMA Indian Diabetes, and PHONEME), GA-based approaches improved F1-scores by 15-22% compared to SMOTE and by 9-15% compared to ADASYN, while simultaneously reducing computational overhead during inference by over 90% due to more compact evolved architectures [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Genetic Algorithm Implementation Protocol

Implementing a Genetic Algorithm for optimization requires careful configuration of multiple parameters and components. The following protocol outlines the key steps for establishing a baseline GA:

Solution Representation: Encode solutions according to problem domain—binary strings for discrete problems, real-valued vectors for continuous optimization, or tree structures for program evolution [10]. The representation should allow meaningful application of genetic operators.

Population Initialization: Generate initial population randomly or using domain-specific heuristics. Typical population sizes range from 50 to 500 individuals, balancing diversity and computational cost [10] [1].

Fitness Function Design: Define a fitness measure that accurately reflects solution quality. For constrained problems, incorporate penalty functions or constraint-handling techniques.

Genetic Operator Configuration:

- Selection: Implement tournament selection (tournament sizes of 2-5) or fitness-proportional selection with elitism (preserving top 1-5% solutions) [10].

- Crossover: Apply single-point or multi-point crossover for binary representations, simulated binary crossover (SBX) for real-valued representations, with crossover rates typically between 0.7-0.95 [12] [10].

- Mutation: Use bit-flip mutation for binary representations, polynomial mutation for real-valued representations, with mutation rates typically between 0.001-0.05 per gene [12] [10].

Termination Criteria: Define stopping conditions—maximum generations (100-5000), convergence threshold (minimal fitness improvement over generations), or computational budget [10].

For enhanced variants like the Population-Based Guiding approach, additional mechanisms include greedy selection based on combined parent fitness and guided mutation using population distributions to determine mutation indices [12].

Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Protocol

The experimental protocol for NPDOA differs significantly from traditional GA approaches, reflecting its brain-inspired foundations:

Neural Population Initialization: Initialize multiple neural populations, treating each solution as a neural state where decision variables represent neuron firing rates [1].

Strategy Application:

- Attractor Trending: Drive neural states toward different attractors representing favorable decisions using gradient-like behavior for exploitation [1].

- Coupling Disturbance: Create interference between neural populations to disrupt convergence tendencies and enhance exploration [1].

- Information Projection: Control information transmission between populations using projection matrices to balance exploration-exploitation tradeoff [1].

Parameter Configuration: Set population sizes (typically 30-100), attraction factors, coupling strengths, and information projection rates based on problem dimensionality and complexity [1].

The following diagram illustrates the core strategies and their interactions in the NPDOA framework:

Table 3: Essential Computational Resources for Optimization Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Solutions | Research Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimization Frameworks | PlatEMO, DEAP, MATLAB GA Toolbox | Provides implemented algorithms and benchmarking utilities | General optimization, algorithm comparison [1] [13] |

| Neural Architecture Search | NAS-Bench-101, PyTorch, TensorFlow | Standardized benchmarking of NAS algorithms | Neural network design automation [12] |

| Fitness Evaluation | Custom domain-specific simulators | Quantifies solution quality for specific problems | Drug discovery, protein folding, molecular design |

| Hybrid Algorithm Components | Backpropagation, Gradient Descent | Local refinement within evolutionary frameworks | ATGEN framework, hybrid neuroevolution [14] [15] |

| Data Generation | SMOTE, ADASYN, GA-based synthetic generators | Addresses class imbalance in training data | Medical diagnostics, fraud detection [5] |

The comparative analysis reveals that both Genetic Algorithms and Neural Population Dynamics Optimization offer distinct advantages for different research scenarios. GAs remain a robust choice for problems with complex, discontinuous search spaces where gradient information is unavailable or misleading [9]. Their population-based approach provides resilience against local optima, and their flexibility in solution representation makes them applicable to diverse domains from drug discovery to neural architecture design [12] [5].

NPDOA demonstrates superior performance on many continuous optimization benchmarks, with faster convergence and more consistent results, attributed to its effective balance of exploration and exploitation through biologically-plausible neural dynamics [1]. However, the "no-free-lunch" theorem reminds us that no algorithm dominates all others across all problem types [1].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the selection criteria should include problem dimensionality, search landscape characteristics, computational budget, and solution quality requirements. Hybrid approaches that combine GA's global search with gradient-based local refinement or that incorporate neural dynamics principles may offer the most promising direction for addressing increasingly complex optimization challenges in pharmaceutical research and development.

The pursuit of powerful optimization algorithms is a cornerstone of computational science and engineering. Within this domain, metaheuristic algorithms have emerged as a prominent class of problem-solving strategies, drawing inspiration from natural, biological, or physical phenomena [16]. This guide objectively compares two such algorithms: the established Genetic Algorithm (GA) and the novel Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA). While GAs are inspired by the principles of natural evolution and genetics [5] [17], NPDOA is a brain-inspired framework derived from modeling the dynamics of neural populations during cognitive activities [17]. This comparison is framed within broader research on their relative performance, providing researchers and engineers with the data necessary to select the appropriate tool for their specific optimization challenges.

To understand their performance differences, it is essential first to grasp their foundational principles and operational mechanics.

Genetic Algorithm (GA) is an evolution-based algorithm that operates on a population of candidate solutions. It simulates the process of natural selection through inheritance, mutation, selection, and recombination (crossover) [17] [18]. Solutions are encoded as chromosomes, and individuals with higher fitness are selected to pass their genetic material to subsequent generations. While powerful, GAs can be prone to premature convergence and may exhibit limited local search capabilities [17] [16].

Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) is a newer metaheuristic that models the dynamic interactions and firing behaviors within populations of neurons in the brain [17]. It simulates how neural populations process information and adapt through cognitive activities. This brain-inspired approach is designed to achieve an effective balance between exploration (searching new areas) and exploitation (refining known good solutions) [17].

The table below summarizes their core characteristics:

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of NPDOA and GA

| Feature | Neural Population Dynamics Optimization (NPDOA) | Genetic Algorithm (GA) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Inspiration | Dynamics of neural populations during cognitive activity [17] | Natural evolution and genetics [5] [17] |

| Core Operating Principle | Simulates information processing and adaptation in neural populations [17] | Simulates evolution via selection, crossover, and mutation [17] |

| Population Handling | Models dynamic interactions within a population [17] | Evolves a population of chromosome-encoded solutions [17] |

| Key Strengths | Effective balance of exploration and exploitation; high convergence efficiency [17] | Powerful global search capability; high flexibility and robustness [17] |

| Common Limitations | Relatively new, with less established application track record | Can converge prematurely; local search capability can be limited [17] [16] |

Performance Comparison on Benchmark and Real-World Problems

Empirical evidence from standardized benchmarks and practical applications is crucial for evaluating algorithm performance. The following tables summarize quantitative results from recent studies.

Benchmark Function Performance

Algorithms are often tested on standardized benchmark suites like CEC2017 and CEC2022 to evaluate their core optimization capabilities.

Table 2: Performance on CEC Benchmark Functions

| Algorithm | Average Friedman Rank (CEC2017 & CEC2022) | Key Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NPDOA [17] | Not explicitly stated (See notes) | Noted to demonstrate exceptional performance and high convergence efficiency on CEC2017 and CEC2022 benchmarks [17]. |

| Power Method (PMA) [17] | 2.71 (50D) / 2.69 (100D) | Surpassed nine state-of-the-art algorithms, indicating NPDOA's competitive landscape [17]. |

| CSBOA [18] | Highly competitive | Used for comparison; shows the high performance standard of newer algorithms [18]. |

| Standard GA | N/A | While a classic, newer algorithms often outperform it in convergence speed and accuracy on complex benchmarks [16]. |

Real-World Application Performance

Performance in practical engineering and scientific problems ultimately determines an algorithm's utility.

Table 3: Performance on Real-World Engineering Problems

| Application Domain | Genetic Algorithm (GA) Performance | NPDOA & Related Algorithm Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Satellite Mission Planning | Effective for large-scale, joint planning with hybrid enhancements [19]. | Information not available in search results. |

| Energy-Efficient Sensor Coverage | Superior to Discrete PSO in minimizing distance and balancing energy [20]. | Information not available in search results. |

| Medical Prognostic Modeling | Used as a benchmark. An improved algorithm (INPDOA) achieved an AUC of 0.867 [21]. | INPDOA-enhanced AutoML significantly outperformed traditional algorithms [21]. |

| General Engineering Design | Often used as a baseline for comparison [17] [18]. | PMA (a mathematics-based metaheuristic) demonstrated optimal solutions in 8 engineering problems [17]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure reproducibility and provide context for the data, here are the detailed methodologies from key experiments cited.

Protocol: Benchmarking with CEC Suites

This is a standard protocol for evaluating metaheuristic algorithms [17] [18].

- Algorithm Initialization: Initialize the population of all algorithms (NPDOA, GA, PMA, etc.) with the same size and random distribution.

- Function Evaluation: Run each algorithm on the set of benchmark functions from CEC2017 and CEC2022. These functions are designed to test various challenges like unimodal, multimodal, and hybrid composition problems.

- Data Collection: For each run, record key metrics including the best solution found, convergence speed (number of iterations to a target fitness), and the average fitness across generations.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform statistical tests, such as the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and the Friedman test, to validate the statistical significance of the performance differences between algorithms [17] [18].

- Ranking: Compute average rankings (like the Friedman rank) to provide a composite performance score across all benchmark functions [17].

Protocol: Medical Prognostic Modeling with INPDOA

This protocol outlines the development of a prognostic model for surgery outcomes [21].

- Data Collection & Preprocessing: A retrospective cohort of 447 patients was analyzed. Over 20 clinical parameters were collected. The dataset was split into training and testing sets with stratified random sampling to preserve outcome distribution.

- Handling Imbalanced Data: The Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) was applied exclusively to the training set to address class imbalance for complication prediction [21].

- Model Framework: An automated machine learning (AutoML) framework was used. The improved NPDOA (INPDOA) was integrated to optimize the base-learner selection, feature selection, and hyperparameters simultaneously.

- Model Validation: The model was evaluated on a held-out test set. Performance was measured using the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for complication prediction and the R² score for patient-reported outcome prediction [21].

Algorithm Framework Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows of NPDOA and GA, highlighting their distinct structural logics.

Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Workflow

Genetic Algorithm Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details key computational "reagents" and tools essential for working with or researching these optimization frameworks.

Table 4: Essential Tools and Resources for Optimization Research

| Tool / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance to NPDOA & GA |

|---|---|---|

| CEC Benchmark Suites (e.g., CEC2017, CEC2022) | Standardized sets of test functions for rigorous, comparable evaluation of optimization algorithms [17] [18]. | Critical for performance validation and fair comparison against other metaheuristics. |

| Statistical Tests (Wilcoxon Rank-Sum, Friedman) | Non-parametric tests used to determine the statistical significance of performance differences between multiple algorithms [17] [18]. | Essential for robust experimental conclusions in research papers. |

| Fitness Function | A user-defined function that quantifies the quality of any candidate solution, guiding the algorithm's search process. | The core problem definition for both NPDOA and GA. Must be carefully designed. |

| Synthetic Data Generators (e.g., SMOTE) | Techniques to generate artificial data, often to address class imbalance in datasets for machine learning models [5] [21]. | Used in preprocessing for problems like medical prognosis (e.g., with INPDOA) [21]. |

| AutoML Frameworks | Systems that automate the process of applying machine learning, including model selection and hyperparameter tuning [21]. | Can be integrated with optimizers like INPDOA to enhance model development [21]. |

This comparison guide has objectively detailed the performance characteristics of the brain-inspired NPDOA and the evolution-based GA. The evidence indicates that while Genetic Algorithms remain a versatile and powerful tool for a wide range of optimization problems, including satellite planning and sensor networks [19] [20], newer metaheuristics like Neural Population Dynamics Optimization demonstrate significant promise. NPDOA and its variants are designed to effectively balance exploration and exploitation, showing exceptional performance on standard benchmarks and in complex, real-world domains like medical prognostic modeling [21] [17]. The choice between them is problem-dependent; however, for researchers tackling highly complex, novel problems where traditional algorithms like GA struggle with convergence or local optima, NPDOA represents a compelling, brain-inspired alternative worthy of investigation. The "No Free Lunch" theorem [17] reminds us that no single algorithm is best for all problems, but the continuous innovation in frameworks like NPDOA expands the available toolkit for driving scientific and engineering progress.

The pursuit of artificial intelligence has consistently drawn inspiration from biological systems, with two paradigms standing out: evolution-inspired genetic algorithms and brain-inspired neural computation. Evolutionary algorithms simulate natural selection to optimize solutions, while neural computation mimics the brain's information processing to learn from data. A newer frontier, neural population dynamics, directly models the coordinated activity of brain circuits to make decisions. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these approaches, focusing on their performance, underlying mechanisms, and applicability in research and development, particularly for scientific fields like drug discovery.

Conceptual Foundations and Biological Analogies

The two approaches draw inspiration from different biological scales and principles.

Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) and Genetic Algorithms (GAs) are meta-heuristic optimization techniques inspired by the principles of natural selection [22]. In this analogy, a potential solution to a problem is an "individual," encoded by a "chromosome" (a string of parameters). A population of these individuals evolves over generations through processes of selection (favoring high-performing individuals), crossover (combining traits of parents), and mutation (introducing random changes) [23]. The core idea is the "survival of the fittest," where solutions improve iteratively by rewarding and propagating successful traits [22].

Neural Computation, particularly through artificial neural networks (ANNs), is inspired by the brain's network of neurons [24]. These models learn by adjusting the strength of synaptic connections between neurons, often using error-correcting rules like backpropagation [23]. A more recent advancement, the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA), draws from a finer-grained biological analogy. It models the brain's activity not at the single-neuron level, but at the level of interacting neural populations, simulating how groups of neurons work together to form attractors (stable states representing decisions) and communicate through information projection [1].

Table 1: Core Biological Analogies of Each Approach

| Computational Approach | Biological Inspiration | Core Analogous Components |

|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Algorithms | Natural selection and genetics | Individual → Solution; Chromosome → Parameter set; Gene → Single parameter; Fitness → Performance metric [23] [22] |

| Neural Computation (ANN) | Brain's neuronal structure | Neuron → Computational unit; Synapse → Weighted connection; Firing Rate → Activation value [24] |

| Neural Population Dynamics (NPDOA) | Coordinated activity of neural circuits in the brain | Neural Population → Group of solutions; Attractor → Optimal decision; Information Projection → Communication between populations [1] |

Performance and Experimental Data Comparison

Empirical studies and benchmarks reveal distinct performance characteristics for each algorithm class.

A comparison of improved Genetic Algorithms and Differential Evolution (a variant of EA) on a complex research reactor fuel management problem (a 100-dimensional optimization problem) provides clear performance insights [25]. Furthermore, the novel Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) has been tested against classical meta-heuristics on benchmark and practical engineering problems, demonstrating its competitive edge [1].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Evolutionary and Neural Population Algorithms

| Algorithm | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Reported Performance Highlights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Effective global search; Handles complex, non-differentiable objective functions [25] [22] | Can be computationally expensive; Risk of premature convergence to local optima [25] [22] | In a complex 100D problem, a GA with tournament selection was trapped in a local optimum in ~26% of runs [25]. |

| Differential Evolution (DE) | Strong robustness and exploration; Fast convergence; Few control parameters [25] | May require improvements to maintain potential good solutions during evolution [25] | Showed superior exploration on a 100D problem; was trapped in local optima less often than GA variants [25]. |

| Neural Population Dynamics (NPDOA) | Balanced exploration & exploitation; Brain-inspired decision-making; Avoids premature convergence [1] | Computational complexity can increase with problem dimensions [1] | Verified effectiveness on benchmark and practical problems; offered distinct benefits for single-objective optimization [1]. |

Efficiency and Computational Cost

Hybrid evolutionary approaches, such as the ATGEN framework, demonstrate significant efficiency gains. By combining GAs with local gradient-based refinement and dynamic architecture adaptation, ATGEN achieved a nearly 70% reduction in training time and a over 90% reduction in computation during inference due to minimal network architectures [14].

In a direct statistical comparison on the same optimization problem, Differential Evolution and a GA with tournament selection performed similarly and significantly better than a GA with roulette wheel selection, highlighting the importance of algorithm configuration [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear understanding of the methodological rigor, this section outlines the standard protocols for implementing and evaluating these algorithms.

Protocol for Evolutionary Algorithms (e.g., GA)

This protocol is adapted from applications in complex optimization domains like in-core fuel management [25].

- Problem Encoding: Represent a potential solution (e.g., a core loading pattern) as a vector of

Dinteger variables, where each variable corresponds to a position and value [25]. - Initialization: Generate an initial population of

NPindividuals (vectors) randomly within the defined search space [25]. - Fitness Evaluation: For each individual in the population, calculate its fitness by executing a simulation or model (e.g., a reactor physics code) to determine the objective parameters, which are then combined into a single fitness value [25].

- Selection: Apply a selection operator (e.g., tournament selection) to choose parent individuals for reproduction, favoring those with higher fitness [25].

- Crossover: Apply a crossover operator (e.g., two-point crossover) to pairs of parents to create offspring. This combines genetic material from two parents [25].

- Mutation: Apply a mutation operator (e.g., scramble mutation) with a defined probability to introduce random changes in the offspring, maintaining population diversity [25].

- Termination Check: If the maximum number of generations is reached or another convergence criterion is met, stop the process and select the best individual as the solution. Otherwise, replace the old population with the new one and return to Step 3 [25].

GA Experimental Workflow

Protocol for Neural Population Dynamics Optimization (NPDOA)

This protocol outlines the procedure for the brain-inspired NPDOA meta-heuristic [1].

- Initialization: Initialize multiple neural populations. The state of each population (a potential solution) is represented as a vector where each variable symbolizes the firing rate of a neuron [1].

- Attractor Trending Strategy: For each population, calculate the trend towards an attractor (a stable state representing a good decision). This strategy drives exploitation by pushing populations toward known good solutions [1].

- Coupling Disturbance Strategy: Simulate the interaction between different neural populations. This strategy disrupts the trend towards attractors, thereby enhancing exploration and preventing premature convergence [1].

- Information Projection Strategy: Control the communication and influence between the neural populations. This strategy dynamically regulates the balance between the exploitative attractor trending and the explorative coupling disturbance [1].

- Update Neural States: Update the state (solution) of each neural population based on the combined effects of the three core strategies [1].

- Termination Check: If the maximum number of iterations is reached or the solution quality is satisfactory, stop. Otherwise, return to Step 2 [1].

NPDOA Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details the essential computational "reagents" and components required to implement experiments in evolutionary and neural computation research.

Table 3: Essential Components for Evolutionary and Neural Computation Research

| Item Name | Function / Definition | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Fitness Function | A function that quantifies the performance or quality of a candidate solution. | Evolutionary Algorithms; It guides the selection process by assigning a score to each individual [23] [25]. |

| Selection Operator | A mechanism (e.g., Tournament, Roulette Wheel) to choose parents for reproduction based on fitness. | Evolutionary Algorithms; It enforces "survival of the fittest" by prioritizing high-performing individuals [25]. |

| Population (of Solutions) | A set of candidate solutions that are evolved simultaneously. | Evolutionary Algorithms & NPDOA; It represents the gene pool or neural collective that undergoes iterative improvement [23] [1]. |

| Crossover & Mutation Operators | Genetic operators that recombine and randomly alter offspring solutions. | Evolutionary Algorithms; They are responsible for creating new solution variations and maintaining diversity [25] [22]. |

| Attractor Trending Strategy | A dynamics strategy that drives solutions towards stable, high-quality states. | Neural Population Dynamics (NPDOA); It is responsible for the local exploitation and refinement of solutions [1]. |

| Coupling Disturbance Strategy | A dynamics strategy that disrupts solutions to explore new areas of the search space. | Neural Population Dynamics (NPDOA); It prevents premature convergence and fosters global exploration [1]. |

| Neural State Vector | A representation of a solution where each variable corresponds to a neuron's firing rate. | Neural Population Dynamics (NPDOA); It is the fundamental representation of a candidate solution within a neural population [1]. |

Both evolution-inspired and neural computation-inspired algorithms offer powerful, biologically-grounded tools for solving complex optimization problems. Evolutionary Algorithms provide a robust, gradient-free global search capability, making them suitable for problems where gradient information is unavailable or the search space is highly complex [25] [22]. The emerging Neural Population Dynamics approach offers a sophisticated brain-inspired model that intrinsically balances exploration and exploitation, showing promise in avoiding local optima and achieving competitive performance on benchmark problems [1].

The choice between them depends on the specific problem constraints. For problems requiring extreme computational efficiency and minimal inference costs, modern hybrid evolutionary methods like ATGEN are highly compelling [14]. For complex, single-objective optimization where avoiding premature convergence is critical, Neural Population Dynamics presents a novel and effective alternative [1]. Ultimately, the continued cross-pollination of ideas between these biologically-inspired fields will likely yield even more capable and efficient optimization strategies for scientific research.

The Critical Balance of Exploration and Exploitation in Optimization

In computational optimization, the exploration-exploitation trade-off is a fundamental dilemma: should an algorithm prioritize searching new regions of the solution space (exploration) or refine known good solutions (exploitation)? This balance is crucial across domains, from tuning neural population models to solving engineering design problems. Excessive exploration wastes computational resources, while premature exploitation can trap algorithms in local optima, preventing discovery of globally optimal solutions [26] [27].

This guide objectively compares how different optimization frameworks manage this trade-off, with specific focus on Genetic Algorithms (GAs) and emerging methods for neural population dynamics. We present experimental data from benchmark functions and real-world problems, providing researchers with actionable insights for selecting appropriate optimization strategies.

Theoretical Framework: The Exploration-Exploitation Balance

The exploration-exploitation balance is widely recognized as crucial for metaheuristic performance [26]. In simple terms, exploration involves discovering diverse solutions across different search space regions, facilitating localization of promising areas. Exploitation intensifies search within these areas to improve existing solutions and accelerate convergence [26].

Formally, this trade-off appears in multiple computational frameworks:

- Multi-Armed Bandits: Agents select between arms with unknown rewards, balancing sampling for information (exploration) versus reward maximization (exploitation) [28].

- Metaheuristic Optimization: Bio-inspired algorithms like Genetic Algorithms and particle swarm optimization use population-based strategies where exploration and exploitation are balanced through operators like crossover/mutation [26].

- Reinforcement Learning: Agents balance trying new actions versus leveraging known rewarding actions [28].

The fundamental challenge lies in dynamically adjusting this balance throughout the optimization process, as different stages may require different exploration-exploitation ratios [27].

Algorithm Comparison: Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Genetic Algorithms (GAs)

Methodology: Genetic Algorithms are evolutionary algorithms inspired by natural selection. A population of candidate solutions evolves through selection, crossover (recombination), and mutation operators [5]. Selection and crossover primarily facilitate exploitation by combining good solutions, while mutation introduces exploration through random perturbations [6].

Experimental Protocol: Typical GA evaluation involves:

- Population Initialization: Generating random solutions or using domain-specific heuristics

- Fitness Evaluation: Assessing solution quality against objective function

- Selection: Choosing parents based on fitness (e.g., tournament selection)

- Crossover: Combining parent solutions to produce offspring

- Mutation: Introducing random changes to maintain diversity

- Termination Check: Continuing until convergence criteria met or generations exhausted [5] [6]

Parameters requiring tuning include population size, crossover rate, mutation rate, and selection pressure [6].

Neural Dynamics Optimization (Energy-based Autoregressive Generation)

Methodology: The Energy-based Autoregressive Generation (EAG) framework employs an energy-based transformer that learns temporal dynamics in latent space through strictly proper scoring rules [29]. This approach explicitly models neural population dynamics as stochastic processes on low-dimensional manifolds.

Experimental Protocol:

- Stage 1 - Neural Representation Learning: An autoencoder maps high-dimensional neural spiking data to a low-dimensional latent space under a Poisson observation model with temporal smoothness constraints [29].

- Stage 2 - Energy-based Latent Generation: An energy-based autoregressive framework predicts missing latent representations through masked autoregressive modeling, enabling efficient generation while preserving trial-to-trial variability [29].

Quantum-Inspired Optimization (QIO)

Methodology: Quantum-Inspired Optimization adapts quantum computing principles for classical hardware, using quantum-inspired representations like qubits and quantum gates to maintain superposition states that simultaneously represent multiple solutions [30]. The independent evolution of individuals and application of rotational gates provides inherent parallelization.

Experimental Protocol:

- Quantum Representation: Solutions encoded as quantum-inspired vectors

- Quantum Gates Application: Rotation gates applied to adjust solution probabilities

- Measurement: Collapsing quantum states to classical solutions for evaluation

- Evolution: Updating quantum states based on fitness feedback [30]

Table 1: Core Methodological Differences in Optimization Approaches

| Algorithm | Inspiration Source | Solution Representation | Key Exploration Mechanism | Key Exploitation Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm | Natural evolution | Binary/Real-valued vectors | Mutation | Selection, Crossover |

| Neural EAG | Neural dynamics | Latent space embeddings | Stochastic sampling | Energy minimization |

| QIO | Quantum mechanics | Quantum-inspired vectors | Rotation gates | Measurement collapse |

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Benchmark Results

Benchmark Function Performance

Standard benchmark functions like Ackley, Rastrigin, and Rosenbrock provide controlled testing environments for optimization algorithms. These functions are highly nonlinear, non-convex, and contain numerous local minima, making them challenging for gradient-based approaches [30].

Table 2: Performance Comparison on Standard Benchmark Functions (30 Trials)

| Algorithm | Ackley Function | Rastrigin Function | Rosenbrock Function | Population Size | Function Evaluations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm | 12× more evaluations than QIO | 5.1× more evaluations than QIO | 2.2× more evaluations than QIO | 2000 | ~600,000 |

| QIO | Reference performance | Reference performance | Reference performance | 100 | ~50,000 |

| IFOX | 40% improvement over basic FOX | Competitive with state-of-the-art | 880 wins across benchmarks | Adaptive | Not specified |

The Improved FOX (IFOX) algorithm, which incorporates a dynamic adaptive method for balancing exploration and exploitation, demonstrated a 40% improvement in overall performance metrics over the original FOX algorithm [27]. In comprehensive testing across 81 benchmark functions, IFOX achieved 880 wins, 228 ties, and 348 losses against 16 optimization algorithms [27].

Real-World Application Performance

In practical applications, the balance between exploration and exploitation becomes even more critical due to complex, constrained search spaces.

Table 3: Performance in Real-World Applications

| Application Domain | Genetic Algorithm Performance | Alternative Approach | Comparative Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Land Cover Mapping | 85.8% accuracy (best base classifier) | GA-optimized ensemble | 96.2% accuracy (+10.4% improvement) [6] |

| Imbalanced Learning | Traditional SMOTE/ADASYN | GA-based synthetic data generation | Significant outperformance on F1-score, ROC-AUC [5] |

| Motor BCI Decoding | Not specified | EAG neural modeling | 12.1% improvement in decoding accuracy [29] |

| Engineering Design | Varies by problem | IFOX algorithm | Competitive against state-of-the-art algorithms [27] |

For neural population dynamics specifically, the EAG framework achieved state-of-the-art generation quality with substantial computational efficiency improvements, particularly over diffusion-based methods, delivering a 96.9% speed-up while maintaining high fidelity [29].

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Genetic Algorithm Optimization Workflow

Genetic Algorithm Optimization Workflow

Neural Population Dynamics Optimization

Neural Population Dynamics Optimization

Exploration-Exploitation Balance in Decision-Making

Exploration-Exploitation Decision Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Optimization Studies

| Research Tool | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Web of Science Database | Literature mining for bibliometric analysis | Tracking publication trends in exploration-exploitation balance research [26] |

| CEC Benchmark Functions | Standardized algorithm testing | Ackley, Rastrigin, Rosenbrock functions for performance validation [27] [30] |

| Bibliometrix (R Package) | Quantitative bibliometric analysis | Mapping collaborative networks and thematic trends [26] |

| VOSviewer | Scientific network visualization | Constructing and visualizing co-authorship networks [26] |

| Google Earth Engine | Remote sensing data processing | Land cover classification studies using optimized ML [6] |

| Neural Latents Benchmark | Standardized neural datasets | MCMaze and Area2bump datasets for neural dynamics [29] |

| CUDA C++ with NVIDIA A100 | GPU-accelerated computing | High-performance implementation of optimization algorithms [30] |

The critical balance between exploration and exploitation remains a fundamental consideration in optimization algorithm design. Experimental evidence demonstrates that:

Adaptive balance strategies consistently outperform static approaches, as shown by IFOX's 40% improvement over the basic FOX algorithm [27].

Genetic Algorithms provide versatile optimization but may require substantial computational resources, particularly for complex multimodal problems [30].

Neural dynamics approaches like EAG offer significant advantages for specialized domains including brain-computer interfaces and neural engineering, achieving up to 12.1% improvement in decoding accuracy [29].

Emergent methods like Quantum-Inspired Optimization demonstrate potential for substantial efficiency gains, requiring up to 12× fewer function evaluations than traditional GAs on challenging benchmarks [30].

The optimal algorithm choice depends heavily on specific application requirements, with GAs providing general-purpose robustness, neural methods excelling in temporal dynamics modeling, and quantum-inspired approaches offering computational efficiency for certain problem classes. Future research directions include developing more sophisticated adaptive balancing techniques and leveraging domain-specific knowledge to guide the exploration-exploitation trade-off.

Implementation and Use Cases: Optimizing Neural Networks and Biomedical Models

In the evolving landscape of computational intelligence, two distinct paradigms have demonstrated remarkable capabilities for solving complex optimization problems: genetic algorithms (GAs) inspired by natural selection and neural population dynamics models inspired by brain function. As researchers and drug development professionals increasingly tackle high-dimensional problems with complex search spaces, understanding the comparative strengths and applications of these approaches becomes critical. Genetic algorithms provide a population-based stochastic search methodology that excels in global optimization, while neural approaches typically leverage gradient-based learning for pattern recognition and function approximation.

This guide provides a comprehensive analysis of the genetic algorithm workflow, focusing on its core components—population initialization, selection, crossover, and mutation—while contextualizing its performance against emerging neural population dynamics techniques. We present experimental data from recent studies across multiple domains, including drug discovery and neural architecture optimization, to objectively quantify the performance characteristics of genetic algorithms in research applications.

Core Components of the Genetic Algorithm Workflow

Population Initialization

The genetic algorithm begins by creating an initial population of potential solutions (chromosomes). This population can be generated entirely randomly or can incorporate known feasible solutions to accelerate convergence [31] [32]. The size of this initial population ((N_{pop})) is a critical parameter that must be calibrated for optimal performance [32]. For problems with approximate knowledge of the solution domain, the InitialPopulationRange can be specified to bias the search toward promising regions [31].

In practice, each chromosome is typically encoded as a string of values (binary, integer, or floating-point) representing a potential solution to the optimization problem. The decoding function maps this encoded representation back to the solution space, with the precision of this mapping determined by the encoding length [33].

Selection Operators

Selection operators determine which individuals in the current population are chosen as parents for producing the next generation. These operators implement the "survival of the fittest" principle by prioritizing individuals with better fitness values [34] [31].

- Tournament Selection: A sample of individuals is taken from the population, and the one with the best fitness is selected. This process is repeated multiple times to select all parents for recombination [33].

- Stochastic Universal Selection: The scaled fitness values (expectation values) are used to create a line where each parent corresponds to a section with length proportional to its scaled value. The algorithm then moves along this line in equal steps to select parents [31].

- Elitism: A mechanism that automatically copies the best-performing individuals ((EliteCount)) directly to the next generation, ensuring that high-quality solutions are preserved [10] [31].

Advanced (2025) selection techniques include adaptive methods that dynamically adjust fitness measurement and AI-based ranking systems to identify promising solutions faster [34].

Crossover (Recombination) Operators

Crossover operators combine genetic information from two or more parent solutions to create offspring [34] [32]. This process enables the algorithm to explore new combinations of existing solution features.

- One-point Crossover: A crossover point is randomly selected, and genetic material beyond this point is swapped between two parents [33].

- Multi-point Crossover: Multiple crossover points are selected, creating more complex recombination of parental traits [34].

- Uniform Crossover: Each gene is independently swapped between parents with a specified probability [31].

- Intermediate Crossover: For continuous problems, offspring are created as a random weighted average of the parents [31].

Recent advancements include multi-parent crossover combining more than two parents for greater variety and adaptive crossover rates that adjust based on convergence progress [34].

Mutation Operators

Mutation introduces random changes to individual solutions, maintaining population diversity and preventing premature convergence to local optima [34] [32].

- Bit-flip Mutation: In binary representations, randomly selected bits are inverted (0 becomes 1, or 1 becomes 0) [10] [33].

- Gaussian Mutation: For continuous problems, random noise from a Gaussian distribution is added to gene values [31].

- Swap Mutation: In sequence problems, two elements are randomly selected and their positions swapped [34].

The mutation probability ((P_{mut})) is typically kept small to avoid disrupting the search process excessively [33] [32]. Modern implementations use adaptive mutation rates that change based on population diversity and guided mutation algorithms where AI predicts promising changes [34].

Table 1: Genetic Algorithm Operator Types and Characteristics

| Operator Type | Key Variants | Primary Function | Advanced (2025) Developments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selection | Tournament, Stochastic Universal, Elitism | Choose fittest individuals as parents | Adaptive selection, AI-based ranking, hybrid ML classifiers |

| Crossover | One-point, Multi-point, Uniform, Intermediate | Combine parental traits to create offspring | Multi-parent crossover, adaptive rates, neural-guided recombination |

| Mutation | Bit-flip, Gaussian, Swap | Introduce diversity and prevent premature convergence | Adaptive rates, AI-guided mutation, reinforcement learning integration |

Visualizing the Genetic Algorithm Workflow

The complete genetic algorithm process forms an iterative cycle that evolves solutions across generations, as illustrated in the following workflow diagram:

Genetic Algorithm Optimization Cycle

Genetic Algorithms vs. Neural Population Dynamics: Experimental Comparisons

Performance in Complex Control Tasks

Recent research has explored hybrid approaches combining genetic algorithms with neural networks for complex control tasks. The ATGEN (Adaptive Tensor of Augmented Topology) framework demonstrates how GAs can evolve both the architecture and parameters of dynamic neural networks [14].

Table 2: ATGEN Framework Performance in Control Tasks [14]

| Metric | Simple Tasks | Complex Tasks | Improvement vs. Conventional Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convergence Speed | Several seconds | Several minutes | Training time reduced by nearly 70% |

| Computational Efficiency | 90%+ parameter reduction | 90%+ parameter reduction | Inference computation reduced by over 90% |

| Architecture Efficiency | Minimal effective configuration | Minimal effective configuration | Comparable final performance with minimal parameters |

The ATGEN methodology incorporates several innovative mechanisms: (1) dynamic architecture adaptation that trims neural networks to compact configurations, (2) a Blending mechanism for propagating essential features across layers, (3) experience replay buffers to avoid redundant fitness evaluations, and (4) backpropagation integration as a mutation operator for refinement [14].

Hyperparameter Optimization for Deep Learning Models

Genetic algorithms have demonstrated particular effectiveness in optimizing hyperparameters for deep learning models used in side-channel analysis (SCA) attacks. A 2025 study implemented a GA framework to navigate complex hyperparameter search spaces, overcoming limitations of conventional methods like grid search (poor scalability) and Bayesian optimization (challenges with high-dimensional spaces) [35].

Table 3: Hyperparameter Optimization Performance Comparison [35]

| Optimization Method | Key Recovery Accuracy | Rank in Overall Performance | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm | 100% across test cases | 1st in 25% of cases, 2nd overall | Efficient in high-dimensional spaces |

| Random Search | 70% accuracy | Below GA | Less sample-efficient |

| Bayesian Optimization | Not specified | Below GA | Struggles with discrete parameters |

| Grid Search | Not specified | Below GA | Poor scalability |

The experimental protocol involved: (1) defining a search space encompassing architectural hyperparameters (network depth, layer width, layer types), activation functions, and learning rates; (2) implementing a GA with appropriate representation of hyperparameter configurations; (3) evaluating configurations using success rate (SR) and guessing entropy (GE) metrics specific to SCA; and (4) comparing against baseline methods under identical conditions [35].

Wastewater Characterization and Drug Discovery Applications

Comparative analyses extend to environmental science and pharmaceutical domains. A study comparing neural networks and genetic algorithms for wastewater characterization using LED spectrophotometry found that while both techniques provided similar fits, neural networks generally performed better on test data, with the exception of Total Suspended Solids (TSS) characterization in raw wastewater where genetic algorithms excelled [36].

In drug discovery, AI-driven platforms utilizing evolutionary approaches have dramatically compressed early-stage research timelines. For instance, Exscientia's generative AI platform reported design cycles approximately 70% faster requiring 10× fewer synthesized compounds than industry norms [37]. The company progressed an idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis drug from target discovery to Phase I trials in just 18 months, compared to the typical 5-year timeline for traditional approaches [37].

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Genetic Algorithm Experiments

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function in GA Research |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization Frameworks | ATGEN [14], MATLAB Global Optimization Toolbox [31] | Provide foundational algorithms and infrastructure for implementing and testing GA approaches |

| Computational Platforms | Amazon Web Services (AWS) with robotic automation [37] | Enable scalable computation for population evaluation and parallel fitness assessment |

| Benchmark Datasets | Credit Card Fraud Detection, PIMA Indian Diabetes, PHONEME [5] | Standardized datasets for comparative performance evaluation across algorithms |

| Hybrid AI Platforms | Exscientia's DesignStudio [37], Recursion's phenomics platform [37] | Integrated environments combining GA with other AI approaches for drug discovery |

| Performance Metrics | Success Rate (SR), Guessing Entropy (GE) [35], RMSE [36] | Specialized metrics for quantifying algorithm performance in specific domains |

Advanced Hybrid Frameworks: Genetic Algorithms with Neural Components

The integration of genetic algorithms with neural network components has enabled sophisticated optimization frameworks capable of tackling increasingly complex problems. The following diagram illustrates the architecture of the ATGEN framework, which combines GA evolutionary strategies with neural network components:

ATGEN Hybrid Optimization Framework

This framework exemplifies the convergence of genetic and neural approaches, leveraging the global search capabilities of GAs while incorporating neural-inspired mechanisms for local refinement and architectural efficiency [14].

Genetic algorithms provide a powerful, flexible approach for optimization problems characterized by complex, high-dimensional, and non-differentiable search spaces. Their performance advantages are particularly evident in scenarios requiring global optimization, architectural search, and problems with multiple objectives or constraints.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the strategic selection between genetic algorithms and neural population dynamics approaches should consider: (1) problem structure and differentiability, (2) availability of gradient information, (3) need for architectural innovation versus parameter optimization, and (4) computational constraints. Genetic algorithms excel in exploratory phases where the solution structure is unknown, while neural approaches often prove more efficient for refinement within known architectural paradigms.

The emerging trend of hybrid frameworks demonstrates that the most powerful solutions often integrate multiple optimization strategies, leveraging the global exploration of genetic algorithms with the local refinement capabilities of gradient-based and neural approaches. As computational resources expand and algorithms evolve, these hybrid paradigms are poised to tackle increasingly complex challenges across scientific domains, from drug discovery to adaptive control systems.

In the evolving landscape of artificial intelligence and computational neuroscience, optimization algorithms play a pivotal role in enhancing model performance and addressing fundamental data challenges. Within this context, Genetic Algorithms (GAs) have emerged as powerful, nature-inspired optimization techniques with significant applications in deep learning. This guide provides an objective comparison of GA performance against alternative methods for two critical tasks: hyperparameter tuning for deep neural networks and handling imbalanced datasets. The analysis is framed within broader research on neural population dynamics optimization, exploring how different biologically-inspired algorithms address complex optimization challenges.

The significance of this comparison extends particularly to researchers and drug development professionals who increasingly rely on deep learning models for tasks such as biomedical image analysis, drug discovery, and patient stratification, where both model optimization and class imbalance are frequently encountered challenges. As we examine the experimental data and methodologies, we focus on providing a balanced perspective on the strengths and limitations of GAs relative to emerging approaches, including the novel Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) [1].

Genetic Algorithms in Context: Core Principles and Neural Inspirations

Genetic Algorithms belong to a class of evolutionary algorithms that mimic natural selection processes to solve optimization problems. Inspired by Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, GAs operate through mechanisms of selection, crossover, and mutation to evolve a population of candidate solutions toward optimal configurations [38]. In machine learning applications, this approach proves particularly valuable for optimizing non-differentiable, high-dimensional, and irregular objective functions that challenge gradient-based methods.

The connection to neural inspirations emerges when comparing GAs with the newly proposed Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA), which draws inspiration from brain neuroscience rather than evolutionary biology [1]. While GAs emulate evolutionary processes across generations, NPDOA simulates the activities of interconnected neural populations during cognition and decision-making. This brain-inspired approach implements three core strategies: attractor trending for driving convergence toward optimal decisions, coupling disturbance for maintaining exploration capability, and information projection for controlling communication between neural populations [1].

This distinction in biological inspiration leads to fundamental architectural differences with implications for optimization performance across different problem domains. Both approaches represent nature-inspired meta-heuristic algorithms but derive their mechanisms from different aspects of biological systems.

Table 1: Comparison of Algorithmic Inspirations and Characteristics

| Feature | Genetic Algorithms (GAs) | Neural Population Dynamics Optimization (NPDOA) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Inspiration | Natural evolution and genetics | Brain neural population dynamics |

| Core Mechanisms | Selection, crossover, mutation | Attractor trending, coupling disturbance, information projection |

| Solution Representation | Chromosome-encoded parameters | Neural state with firing rates |

| Exploration Emphasis | Mutation operations | Coupling disturbance strategy |

| Exploitation Emphasis | Elite selection | Attractor trending strategy |

| Transition Control | Parameter adjustment | Information projection strategy |

Performance Comparison: Hyperparameter Tuning Applications

Experimental Protocols for Hyperparameter Tuning

The evaluation of hyperparameter tuning methods typically follows a standardized experimental protocol. Researchers encode hyperparameters—such as the number of hidden layers, neurons per layer, learning rate, and batch size—into a chromosome-like structure [39]. The fitness function is typically the validation accuracy obtained from training a model with the specified hyperparameters. Comparative studies evaluate performance across multiple generations, tracking convergence speed and final model accuracy.

In a representative study, a C# implementation of GA for neural network hyperparameter optimization demonstrated how the algorithm evolves populations of hyperparameter combinations over generations [39]. The methodology includes tournament selection for parent selection, single-point crossover for recombination, and bounded random mutation to maintain diversity. Each candidate solution is evaluated by training a model with the proposed hyperparameters and measuring validation accuracy.

Comparative Performance Data

Research comparing hyperparameter optimization methods reveals distinct performance characteristics across different approaches. A study on uniaxial compressive strength prediction provides quantitative comparisons between GA and other optimization methods when applied to machine learning models [40]. The research employed both grid search and genetic algorithm-based hyperparameter optimization across multiple models, including multilayer perceptron, random forest, support vector machine, and extreme gradient boosting.

Table 2: Hyperparameter Optimization Method Comparison

| Method | Search Strategy | Computation Cost | Scalability | Best R² Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grid Search | Exhaustive | High | Low | Not Specified |

| Random Search | Stochastic | Medium | Medium | Not Specified |

| Bayesian Optimization | Probabilistic Model | High | Low-Medium | Not Specified |

| Genetic Algorithm | Evolutionary | Medium-High | High | 0.9762 [40] |

The stacking model with GA-based hyperparameter tuning achieved an exceptional testing R² value of 0.9762, demonstrating the effectiveness of the evolutionary approach for complex model optimization [40]. This performance advantage stems from GA's global search capability, which helps avoid local minima—a common limitation of gradient-based methods. Additionally, the model-agnostic nature of GAs enables application across diverse architectures from SVMs to deep neural networks [38].

Performance Comparison: Imbalanced Data Handling

Experimental Protocols for Imbalanced Data

Addressing class imbalance represents another significant application of genetic algorithms in deep learning. The experimental protocol for evaluating GA-based approaches typically involves comparing performance against established techniques like SMOTE, ADASYN, and GANs across multiple imbalanced datasets [41]. Common benchmark datasets include Credit Card Fraud Detection, PIMA Indian Diabetes, and PHONEME, which feature binary imbalanced classes.

Methodologies typically employ a GA to generate synthetic training instances optimized through fitness functions and population initialization [41]. The process leverages machine learning models, particularly Support Vector Machines and logistic regression, to analyze underlying data distributions and create fitness functions that maximize minority class representation. Unlike interpolation-based methods like SMOTE, the GA approach does not require large sample sizes and can create synthetic datasets that better capture complex class boundaries.

Comparative Performance Data