Neural Population Dynamics Optimization: Algorithms for Brain Computation and Biomedical Innovation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of neural population dynamics optimization algorithms, a cutting-edge framework that combines dynamical systems theory, machine learning, and large-scale neural recordings to understand brain computation.

Neural Population Dynamics Optimization: Algorithms for Brain Computation and Biomedical Innovation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of neural population dynamics optimization algorithms, a cutting-edge framework that combines dynamical systems theory, machine learning, and large-scale neural recordings to understand brain computation. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles of how populations of neurons collectively perform computations through their coordinated temporal evolution. We detail key methodological advances, including low-rank dynamical models, active learning for efficient data collection, and privileged knowledge distillation that integrates behavioral data. The article further addresses central troubleshooting and optimization challenges, such as overcoming local minima and managing high-dimensional data, and provides a rigorous validation framework comparing algorithm performance across biomedical applications. Finally, we discuss the transformative potential of these algorithms in accelerating drug discovery and improving clinical trial design.

The Core Principles of Neural Population Dynamics and Their Computational Role

Defining Computation Through Neural Population Dynamics (CTD)

Computation Through Neural Population Dynamics (CTD) is a foundational framework in modern neuroscience for understanding how neural circuits perform computations. This approach posits that the brain processes information through the coordinated, time-varying activity of populations of neurons, which can be formally described using dynamical systems theory [1] [2]. The core insight of CTD is that cognitive functions—including decision-making, motor control, timing, and working memory—emerge from the evolution of neural population states within a low-dimensional neural manifold [2] [3]. This stands in contrast to perspectives that focus on individual neuron coding, instead emphasizing that collective dynamics are fundamental to neural computation [4].

The CTD framework has gained prominence due to significant advances in experimental techniques that enable simultaneous recording of large neural populations, coupled with computational developments in modeling and analyzing high-dimensional dynamical systems [2] [4]. This framework provides a powerful lens through which researchers can interpret complex neural data, formulate testable hypotheses about neural function, and even develop novel brain-inspired optimization algorithms, such as the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) [5].

Mathematical Foundations of Neural Population Dynamics

Core Dynamical Systems Formulation

At the heart of CTD is the formal treatment of a neural population as a dynamical system. The activity of a population of N neurons is represented by an N-dimensional vector, x(t), where each element represents the firing rate of a single neuron at time t [2]. The evolution of this neural population state is governed by the equation:

[ \frac{dx}{dt} = f(x(t), u(t)) ]

Here, (f) is a function—potentially nonlinear—that captures the intrinsic dynamics of the neural circuit, including the effects of synaptic connectivity and neuronal biophysics. The variable (u(t)) represents external inputs to the circuit from other brain areas or sensory pathways [2] [6]. This formulation allows the trajectory of neural activity through state space to be modeled as a dynamical system, analogous to physical systems like pendulums or springs [2].

Linear Approximations and Fixed Point Analysis

While neural dynamics are often nonlinear, linear approximations around fixed points provide valuable analytical insights. A linear dynamical system (LDS) is described by:

[ x(t+1) = Ax(t) + Bu(t) ]

Here, (A) is the dynamics matrix that determines how the current state evolves, and (B) is the input matrix that determines how external inputs affect the state [6] [4]. The fixed points of the system—where (dx/dt = 0)—are critical for understanding its computational capabilities. Around these points, dynamics can be characterized as attractors (stable states), repellers (unstable states), or oscillators [6]. These dynamical motifs are thought to underpin various cognitive functions, such as memory retention (via attractors) and rhythmic pattern generation (via oscillators) [6].

State Space Representation and Dimensionality Reduction

The concept of state space is central to visualizing and analyzing neural population dynamics. Each axis in this space represents the activity of one neuron (or a latent factor), and the instantaneous activity of the entire population is a single point in this high-dimensional space [2]. Over time, this point traces a path called the neural trajectory [2].

A key observation in neural data is that these trajectories often lie on a low-dimensional neural manifold, despite the high dimensionality of the native state space [3] [4]. This means that although thousands of neurons may be recorded, their coordinated activity can be described using many fewer variables. Dimensionality reduction techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) are essential tools for identifying these manifolds and visualizing the underlying neural trajectories [2] [3].

Table 1: Key Mathematical Concepts in Neural Population Dynamics

| Concept | Mathematical Representation | Neural Interpretation | Computational Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neural Population State | (x(t) = [x1(t), x2(t), ..., x_N(t)]) | Firing rates of N neurons at time t | Represents the current state of the population |

| Dynamics Function | (\frac{dx}{dt} = f(x(t), u(t))) | Intrinsic circuit properties & connectivity | Determines how the state evolves over time |

| Fixed Points | (f(x^, u^) = 0) | Stable or unstable equilibrium states | Attractors for memory, decision states |

| Linear Approximation | (\frac{d\delta x}{dt} = A\delta x(t) + B\delta u(t)) | Local dynamics around an operating point | Enables analytical analysis of stability |

| Neural Manifold | Low-dimensional subspace embedded in high-dimensional state space | Collective modes of population activity | Constrains and guides neural computation |

Experimental and Methodological Approaches

Measuring and Analyzing Neural Population Activity

Experimental investigation of CTD requires simultaneous recording from many neurons. Modern techniques include high-density electrophysiology, calcium imaging, and neuropixels probes that can monitor hundreds to thousands of neurons simultaneously across multiple brain areas [4]. The typical workflow involves:

- Neural State Extraction: Preprocessing raw neural recordings (spikes or fluorescence) to obtain firing rates or deconvolved activity for each neuron [2].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Applying PCA or other methods to identify the low-dimensional neural manifold and project high-dimensional data into this subspace [3].

- Dynamics Identification: Using statistical methods to infer the dynamical system (f) that best describes the observed neural trajectories [2] [3].

Recent advances include methods like MARBLE (MAnifold Representation Basis LEarning), which uses geometric deep learning to decompose on-manifold dynamics into local flow fields and map them into a common latent space [3]. This allows for comparison of neural computations across sessions, individuals, or even species.

Perturbation Experiments to Test Causality

A critical advancement in CTD research is the move from observational studies to causal perturbation experiments. These involve manipulating neural activity and observing how the system responds, thus testing hypotheses about computational mechanisms [4]. Two primary approaches are:

- Within-Manifold Perturbations: Displacing the neural state along dimensions of the naturally occurring neural manifold. This tests whether specific dimensions are causally related to behavior [4].

- Outside-Manifold Perturbations: Pushing the neural state into dimensions not typically visited during natural behavior. This can reveal latent computational capacities or stability properties [4].

Techniques for implementing these perturbations include optogenetics, electrical microstimulation, and even task manipulations that alter sensory-motor contingencies [4].

CTD Experimental Workflow: From data acquisition to computational interpretation

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA)

From Biological Principles to Optimization Framework

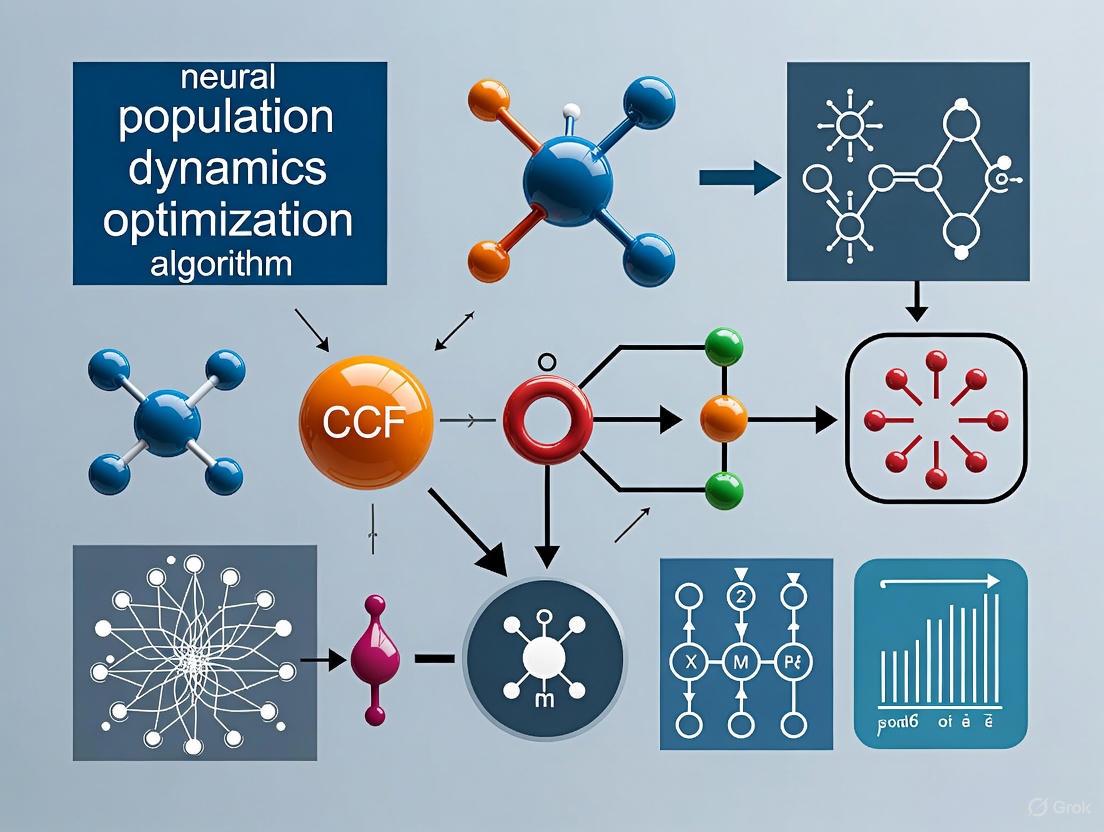

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) is a novel brain-inspired meta-heuristic optimization method that directly translates principles of CTD into an algorithmic framework for solving complex optimization problems [5]. In NPDOA, potential solutions to an optimization problem are represented as neural populations, with each decision variable corresponding to a neuron and its value representing the firing rate of that neuron [5]. The algorithm simulates the activities of interconnected neural populations during cognition and decision-making, implementing three core strategies derived from neural population dynamics [5].

Core Dynamics Strategies in NPDOA

NPDOA implements three fundamental strategies that balance exploration and exploitation, mirroring computations in biological neural systems:

- Attractor Trending Strategy: This strategy drives neural populations toward optimal decisions, ensuring exploitation capability. It mimics how neural populations converge toward stable states associated with favorable decisions [5].

- Coupling Disturbance Strategy: This strategy deviates neural populations from attractors by coupling them with other neural populations, thereby improving exploration ability. It prevents premature convergence by introducing controlled disruptions [5].

- Information Projection Strategy: This strategy controls communication between neural populations, enabling a transition from exploration to exploitation. It regulates the impact of the other two dynamics strategies on neural states [5].

These strategies work together to maintain the crucial balance between exploring new solution spaces and exploiting promising regions, a challenge faced by both artificial optimization algorithms and biological neural systems [5].

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Studying Neural Population Dynamics

| Protocol/Technique | Key Measurements | Analytical Methods | Insights Gained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delay Reaching Task | Neural activity during preparation and movement phases [6] | Analysis of preparatory activity as initial conditions [6] | How initial neural states determine subsequent motor outputs |

| Integration-Based Tasks | Neural trajectories during evidence accumulation [7] | Identification of integration dynamics and attractor states [7] | Mechanisms of decision-making and working memory |

| Multi-Area Recordings | Simultaneous neural activity from connected brain areas [4] | Communication subspace (CS) analysis [4] | How information is selectively communicated between areas |

| Optogenetic Perturbations | Neural trajectory changes following targeted perturbations [4] | Comparison of pre- and post-perturbation dynamics [4] | Causal evidence for computational mechanisms |

| Pharmacological Manipulations | Changes in neural dynamics and behavior [4] | Altered dynamics matrices (A) in LDS models [4] | How circuit properties influence computation |

NPDOA Algorithm Structure: Balancing exploration and exploitation through neural-inspired strategies

Research Toolkit: Essential Methods and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Neural Population Dynamics Studies

| Tool/Technique | Type | Primary Function | Key Applications in CTD |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Density Electrophysiology (Neuropixels) [4] | Measurement | Record hundreds to thousands of neurons simultaneously | Measuring neural population states across brain areas |

| Optogenetics [4] | Perturbation | Precisely control specific neural populations with light | Causal testing of computational hypotheses via within/outside-manifold perturbations |

| Dimensionality Reduction (PCA, t-SNE, UMAP) [3] | Analytical | Identify low-dimensional neural manifolds | Visualizing and analyzing neural trajectories in reduced state spaces |

| Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) [2] [7] | Modeling | Trainable dynamical systems for task modeling | Modeling how neural circuits perform computations through dynamics |

| Linear Dynamical Systems (LDS) [4] | Modeling | Linear approximation of neural dynamics | Baseline models for neural population dynamics; analytical tractability |

| MARBLE [3] | Analytical | Geometric deep learning for neural dynamics | Comparing dynamics across conditions, sessions, and individuals |

| Multi-Plasticity Network (MPN) [7] | Modeling | Network with synaptic modulations during inference | Studying computational capabilities of synaptic dynamics without recurrence |

| Pharmacological Agents (e.g., muscimol) [4] | Perturbation | Transiently alter circuit dynamics | Testing how changes in dynamics matrix (A) affect computation |

The framework of Computation Through Neural Population Dynamics represents a paradigm shift in how neuroscientists conceptualize brain function. By viewing neural computation through the lens of dynamical systems, researchers can leverage powerful mathematical tools to explain how neural circuits give rise to behavior. The CTD perspective has already yielded significant insights into motor control, decision-making, working memory, and timing [1] [2].

Future research directions include expanding CTD to model brain-wide computations across multiple interacting areas [4], developing more sophisticated methods for comparing neural computations across individuals and species [3], and further refining brain-inspired algorithms like NPDOA for solving complex engineering problems [5]. As measurement technologies continue to advance, enabling even larger-scale neural recordings, the CTD framework will likely play an increasingly central role in unraveling the mysteries of neural computation and developing novel artificial intelligence systems inspired by brain principles.

The brain's remarkable computational abilities emerge not from the isolated firing of individual neurons, but from the collective, time-varying activity of large neural populations. Understanding these population dynamics represents a fundamental challenge in modern neuroscience. The dynamical systems framework provides a powerful approach to this challenge, treating neural circuit activity as trajectories through a high-dimensional state space, governed by deterministic and stochastic differential equations [8]. This perspective represents a paradigm shift from descriptive phenomenological models towards a mechanistic understanding of neural computation.

This framework is catalyzing a transformation in precision psychiatry and therapeutic development. By moving beyond static correlations and focusing on the temporal evolution of neural circuit function, it offers a path to detect neuropsychiatric risk prior to the emergence of overt symptoms and to monitor treatment response through quantitative, physiology-based biomarkers [9]. The core thesis is that mental and neurological disorders are ultimately disorders of neural circuit dynamics that develop and change over time, suggesting that monitoring these dynamics can provide crucial personalized information about disease trajectory and treatment efficacy [9].

Theoretical Foundations

From Neural Activity to Dynamical Systems

At its core, the dynamical systems framework for neural circuits posits that the neuroelectric field—the electromagnetic field generated by the synchronized activity of neurons—forms a dynamical system whose properties can be quantified from electrophysiological measurements [9]. This field is considered the physical substrate for all cognition and behavior, serving as the receptor of all sensory input and the physical effector of all movement [9].

The mathematical foundation typically involves describing neural population activity through differential equations that capture how the system state evolves over time. A common formulation for recurrent neural networks (RNNs), which serve as key computational models, is:

[ \tau\dot{x}(t) = -x(t) + Jr(t) + Bu(t) + b ]

Here, (x(t)) represents the synaptic currents, (r(t)) represents the firing rates, (J) is the recurrent connectivity matrix, (Bu(t)) represents external inputs, and (b) is a bias term [8]. This equation captures the essential dynamics of how neural populations integrate inputs over time and transform them into patterns of activity.

Key Computational Principles

Recent theoretical advances have identified several key principles of neural computation within the dynamical systems framework:

- Latent Computing: Neural computations are often low-dimensional, embedded within high-dimensional neural dynamics through latent processing units that enable robust coding despite representational drift in individual neurons [10].

- Manifold Constraint: Neural population dynamics typically evolve on low-dimensional manifolds—smooth subspaces within the high-dimensional state space—that constrain and shape the computational trajectories [3].

- Compositionality: Circuits can perform multiple tasks through compositional representations that combine a shared computational core with specialized neural modules, allowing flexibility and generalization [11].

Table 1: Core Theoretical Concepts in Neural Population Dynamics

| Concept | Mathematical Description | Computational Role |

|---|---|---|

| State Space | High-dimensional space where each axis represents one neuron's firing rate | Provides complete description of population activity at any moment |

| Trajectories | Path through state space over time, ( \vec{x}(t) ) | Encodes temporal evolution of neural processing |

| Attractors | States toward which the system evolves (fixed points, limit cycles) | Underlies stable memory storage and decision states |

| Manifolds | Low-dimensional subspaces ( \mathcal{M} ) constraining trajectories | Reduces dimensionality, reveals computational organization |

| Stability | Lyapunov exponents, Jacobian eigenvalues | Determines robustness to noise and perturbation |

Computational Methodologies

Dynamical Feature Extraction from Neural Data

Extracting dynamical features from experimental recordings requires specialized methodologies. For electrophysiological data such as EEG, the pipeline typically involves:

- Signal Acquisition: Using high-density EEG sensors to measure the neuroelectric field at millisecond resolution [9].

- State Space Reconstruction: Employing embedding techniques to reconstruct the underlying dynamical system from observed time series.

- Feature Quantification: Computing dynamical properties such as stability, oscillatory modes, and attractor landscapes using model-free approaches from dynamical systems theory [9].

These extracted features serve as quantitative proxies for neural circuit function and can be combined with personal and clinical data in machine learning models to create risk prediction models for psychiatric conditions [9].

Advanced Algorithms for Modeling Population Dynamics

Recent methodological advances have significantly improved our ability to infer neural population dynamics:

MARBLE (MAnifold Representation Basis LEarning) uses geometric deep learning to decompose on-manifold dynamics into local flow fields and map them into a common latent space [3]. The method represents the dynamics as a vector field (Fc = (f1(c), \ldots, fn(c))) anchored to a point cloud (Xc = (x1(c), \ldots, xn(c))) of neural states, then approximates the unknown manifold by a proximity graph to define tangent spaces and parallel transport between nearby vectors [3].

Cross-population Prioritized Linear Dynamical Modeling (CroP-LDM) specifically addresses the challenge of distinguishing shared dynamics across brain regions from within-region dynamics [12]. By prioritizing cross-population prediction accuracy in its learning objective, it ensures extracted dynamics correspond to genuine interactions rather than being confounded by within-population dynamics.

iJKOnet approaches learning population dynamics from a different angle, framing it as an energy minimization problem in probability space and leveraging the Jordan-Kinderlehrer-Otto (JKO) scheme for efficient time discretization [13]. This method combines the JKO framework with inverse optimization techniques to learn the underlying stochastic dynamics from observed marginal distributions at discrete time points.

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Neural Population Dynamics Methods

| Method | Theoretical Foundation | Dynamical Features Captured | Scalability | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MARBLE [3] | Geometric deep learning, manifold theory | Local flow fields, fixed point structure | ~1000 neurons | Within- and across-animal decoding |

| CroP-LDM [12] | Prioritized linear dynamical systems | Cross-region directional interactions | Multi-region recordings | Identifying dominant interaction pathways |

| AutoLFADS [14] | Sequential variational autoencoders | Single-trial latent dynamics | Large-scale populations (~1000 neurons) | Motor, sensory, cognitive areas |

| iJKOnet [13] | Wasserstein gradient flows, JKO scheme | Population-level stochastic evolution | Population-level data | Single-cell genomics, financial markets |

Workflow for Neural Population Dynamics Analysis

The following diagram illustrates a generalized computational workflow for analyzing neural population dynamics, integrating elements from multiple methodologies described in the search results:

Figure 1: Computational workflow for clinical application of neural population dynamics, from raw data acquisition to clinical validation.

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Protocol 1: Identifying Neural Manifolds with MARBLE

Objective: To learn interpretable representations of neural population dynamics and identify the underlying manifold structure during cognitive tasks [3].

Procedure:

- Data Collection: Simultaneously record single-neuron activity from relevant brain regions (e.g., premotor cortex in macaques during reaching, hippocampus in rats during navigation) at sampling rates ≥1 kHz.

- Preprocessing: Calculate firing rates using Gaussian kernel smoothing (σ = 20-50 ms). Organize data into trials aligned to behavioral events.

- Manifold Learning:

- Input: Neural firing rates {x(t; c)} for trials under condition c.

- Construct proximity graph to approximate underlying manifold.

- Define local flow fields (LFFs) around each neural state.

- Train geometric deep learning architecture to map LFFs to latent vectors zi using contrastive learning.

- Validation: Assess within- and across-animal decoding accuracy of behavioral variables. Compare neural trajectories across conditions using optimal transport distance between latent distributions.

Key Outputs: Low-dimensional latent representations that parametrize high-dimensional neural dynamics; quantitative similarity metric between dynamical systems across conditions and animals [3].

Protocol 2: Tracking Cross-Population Dynamics with CroP-LDM

Objective: To quantify directional interactions between neural populations in different brain regions, prioritizing shared dynamics over within-region dynamics [12].

Procedure:

- Neural Recording: Simultaneously record multi-unit activity from at least two brain regions (e.g., motor and premotor cortex) during structured behavioral tasks.

- Data Preparation: Bin spike counts into 10-20 ms time bins. Define source and target populations.

- Model Fitting:

- Initialize CroP-LDM with prioritized learning objective for cross-population prediction.

- Learn latent states representing shared dynamics using subspace identification.

- Optionally perform causal (filtering) or non-causal (smoothing) inference.

- Interaction Quantification: Calculate partial R² metric to quantify non-redundant information flow between regions. Identify dominant interaction pathways.

Key Outputs: Interpretable measures of directional influence between brain regions; low-dimensional latent states capturing shared dynamics [12].

Protocol 3: Automated Single-Trial Inference with AutoLFADS

Objective: To automatically infer accurate single-trial neural population dynamics without extensive manual hyperparameter tuning [14].

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Segment neural data (spike counts) into trials or overlapping continuous segments. For self-paced behaviors, use overlapping segments without trial alignment.

- Automated Hyperparameter Optimization:

- Implement coordinated dropout (CD) to prevent identity overfitting.

- Use Population-Based Training (PBT) with evolutionary algorithms for dynamic hyperparameter adjustment.

- Distribute training over dozens of workers simultaneously.

- Model Selection: Use validation likelihood as reliable metric (enabled by CD regularization).

- Rate Inference: Merge inferred firing rates from overlapping segments using weighted combination.

Key Outputs: Denoised single-trial firing rates; latent factors; inputs capturing task-related structure [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density EEG | Measures neuroelectric field dynamics at millisecond resolution | Precision psychiatry brain function checkups [9] |

| Multi-electrode Arrays | Simultaneously records hundreds of neurons across brain regions | Studying cross-population dynamics [12] |

| MARBLE Algorithm | Learns manifold-constrained neural representations | Identifying consistent dynamics across animals [3] |

| AutoLFADS Framework | Automated inference of single-trial dynamics | Modeling less structured, naturalistic behaviors [14] |

| CroP-LDM | Prioritizes learning of shared cross-region dynamics | Identifying dominant interaction pathways [12] |

| iJKOnet | Learns population dynamics from distribution snapshots | Single-cell genomics, financial markets [13] |

| RNNs (vanilla, E-I) | Biologically plausible models of neural computation | Testing circuit mechanisms of decision making [11] |

| Optimal Control Tools | Computes efficient stimulation for modulating dynamics | Controlling oscillations and synchrony [15] |

Applications in Psychiatric Research and Drug Development

The dynamical systems framework offers particularly promising applications in psychiatric research and therapeutic development through several key approaches:

Neural Trajectory Monitoring for Precision Psychiatry

A fundamental application involves reconceptualizing mental health as a trajectory through time rather than a fixed state [9]. This enables:

- Risk Detection Prior to Symptom Emergence: By monitoring changes in neural circuit function through brief, routine EEG measurements analyzed using dynamical systems theory, it may be possible to detect neurophysiological changes that precede observable symptoms [9].

- Personalized Treatment Monitoring: Treatment can be viewed as an intervention designed to redirect a patient's neural trajectory toward more desirable states, with dynamical features providing quantitative metrics of treatment efficacy [9].

- Objective Biomarkers: Dynamical features extracted from EEG provide objective, physiology-based proxies for neural circuit function that complement subjective clinical assessments [9].

Circuit Mechanisms of Decision Making for Cognitive Disorders

Research into the neural basis of economic choice reveals how recurrent neural networks implement value-based decision making through specific circuit mechanisms [11]. Key findings include:

- Two-Stage Computation: Value computation occurs upstream in feedforward pathways where learned input weights store subjective preferences, while value comparison is implemented within recurrent circuits via competitive recurrent inhibition [11].

- Compositional Representations: Single networks can perform multiple tasks through compositional codes combining shared computational cores with specialized modules [11].

These mechanisms provide testable hypotheses for disorders of decision making (e.g., addiction, impulsivity) and suggest potential targets for therapeutic intervention.

Control of Neural Oscillations for Therapeutic Intervention

Optimal control theory applied to neural population models enables precise manipulation of oscillatory dynamics [15]. This approach offers potential for:

- Synchronization Modulation: Controlling synchrony in pathologically synchronized networks (e.g., Parkinson's disease tremors).

- State Switching: Driving transitions between stationary and oscillatory states or between different oscillatory patterns.

- Novel Cost Functionals: Using Fourier, cross-correlation, or variance-based costs to target oscillations without specifying exact reference trajectories [15].

Future Directions

The dynamical systems framework continues to evolve with several promising research directions:

- Integration with Molecular Mechanisms: Future work must bridge the gap between circuit-level dynamics and molecular/cellular processes, potentially through multi-scale modeling approaches.

- Closed-Loop Therapeutic Applications: Real-time monitoring of neural trajectories could enable closed-loop neuromodulation systems that automatically adjust stimulation parameters based on detected state transitions.

- Cross-Species Validation: Developing methods like MARBLE that identify consistent dynamics across animals [3] will be crucial for translating findings from animal models to human applications.

- Network-Level Integration: Combining within-region dynamical analysis with cross-region interaction mapping to understand how distributed neural circuits coordinate to produce cognition and behavior.

As these methodologies mature and become more widely adopted, the dynamical systems framework promises to transform both our fundamental understanding of neural computation and our approach to diagnosing and treating neuropsychiatric disorders.

A fundamental shift is occurring in neurophysiology: the population doctrine is drawing level with the single-neuron doctrine that has long dominated the field [16]. This doctrine posits that the fundamental computational unit of the brain is the population, not the individual neuron [16]. Neural population dynamics describe how the activities across a population of neurons evolve over time due to local recurrent connectivity and inputs from other neural populations [17]. These dynamics provide a framework for understanding neural computation, with studies modeling them to gain insight into processes underlying decision-making, timing, and motor control [18].

The core insight is that neural population activity evolves on low-dimensional manifolds—smooth subspaces within the high-dimensional space of all possible neural activity patterns [19] [20]. This means that while we might record from hundreds of neurons, their coordinated activity traces out trajectories in a much lower-dimensional space [18]. Understanding the structure of these manifolds and the dynamics that unfold upon them has become central to modern neuroscience [20].

Table: Key Concepts in Neural State Space Analysis

| Concept | Definition | Computational Significance |

|---|---|---|

| State Space | Neuron-dimensional space where each axis represents one neuron's activity | Provides spatial view of neural population states as vectors with direction and magnitude [16] |

| Manifold | Low-dimensional subspace where neural population dynamics actually evolve | Reflects underlying computational structure; enables dimensionality reduction [19] [20] |

| Neural Trajectory | Time course of neural population activity patterns in characteristic order | Reveals computational processes through evolution of population state over time [21] |

| Flow Field | Dynamical system governing how neural state evolves from any given point | Determines possible paths and computations; reflects network connectivity [21] |

| Attractor | Stable neural state or pattern toward which dynamics evolve | Implements memory, decisions, or stable motor outputs [5] [22] |

Theoretical Foundations of Neural State Spaces

The State Space Framework

For a population of d neurons, the neural state space is a d-dimensional space where each axis represents the firing rate of one neuron [16]. At each moment in time, the population's activity forms a vector—the neural state—occupying a specific point in this space [16]. As time progresses, this point moves, tracing a neural trajectory that represents the temporal evolution of population activity [16] [18].

The neural state vector has both direction and magnitude [16]. The direction reflects the pattern of activity across neurons, potentially encoding information such as object identity in inferotemporal cortex [16]. The magnitude represents the total activity level across the population and may predict behavioral outcomes like memory performance [16].

Manifolds and Low-Dimensional Structure

Despite the high dimensionality of the neural state space, empirical evidence shows neural population dynamics typically evolve on low-dimensional manifolds [19] [18] [20]. This low-dimensional structure arises from correlations in neural activity and constraints imposed by network connectivity [18]. The discovery of this structure enables powerful dimensionality reduction techniques, making analysis of complex neural data tractable.

Figure 1: The conceptual workflow from high-dimensional neural activity to computation via low-dimensional manifolds and trajectories.

Analytical Methodologies and Visualization Techniques

Dimensionality Reduction for Manifold Identification

Identifying low-dimensional manifolds requires specialized dimensionality reduction techniques:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Linear method that finds orthogonal directions of maximum variance [20]

- Targeted Dimensionality Reduction (TDR): Linear method designed for neural data with specific targeting [20]

- Gaussian Process Factor Analysis (GPFA): Probabilistic method that extracts smooth, low-dimensional latent trajectories from noisy neural data [21]

- t-SNE and UMAP: Nonlinear manifold learning methods that preserve local structure [20]

These techniques transform high-dimensional neural data into more interpretable low-dimensional visualizations while preserving essential dynamical features.

Analyzing Neural Trajectories and Dynamics

Once neural trajectories are identified in low-dimensional state spaces, several analytical approaches characterize their properties:

- Trajectory Geometry: Examining the shape, curvature, and separation of trajectories associated with different behaviors or cognitive states [21]

- Distance Metrics: Quantifying relationships between neural states using Euclidean distance, vector angles, or Mahalanobis distance (which accounts for covariance structure between neurons) [16]

- Dynamic Flow Fields: Characterizing the vector fields that describe how neural states evolve from any given point in state space [21]

Table: Comparison of Neural State Space Analysis Methods

| Method | Type | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | Linear | Finds maximal variance directions; computationally efficient | Misses nonlinear structure; may obscure relevant dynamics |

| GPFA | Probabilistic | Extracts smooth trajectories; handles noise effectively | Complex implementation; requires parameter tuning |

| LFADS (Latent Factor Analysis via Dynamical Systems) | Nonlinear (RNN) | Infers single-trial dynamics; models underlying dynamical system | Requires substantial data; complex training [23] [20] |

| MARBLE (Manifold Representation Basis Learning) | Geometric Deep Learning | Maps local flow fields; enables cross-system comparison; unsupervised [19] [20] | New method with limited track record; computationally intensive |

| CEBRA (Consistent EmBeddings of Recordings using Auxiliary variables) | Representation Learning | Learns joint behavior-neural embeddings; high decoding accuracy | Often requires behavioral supervision for cross-animal consistency [20] |

The MARBLE Framework for Neural Dynamics

The MARBLE (MAnifold Representation Basis LEarning) framework represents a recent advancement in analyzing neural population dynamics [19] [20]. This unsupervised geometric deep learning method:

- Decomposes on-manifold dynamics into local flow fields (LFFs) that capture dynamical behavior in local neighborhoods [20]

- Uses contrastive learning to map LFFs into a common latent space without requiring behavioral supervision [20]

- Provides a well-defined similarity metric (optimal transport distance) to compare dynamics across conditions, sessions, or animals [20]

- Operates in both embedding-aware and embedding-agnostic modes, enabling comparison across different neural recordings [20]

Figure 2: The MARBLE analytical workflow for obtaining interpretable representations of neural dynamics.

Experimental Protocols for Neural State Space Analysis

Experimental Design Considerations

Studies investigating neural population dynamics typically employ:

- Large-Scale Neural Recordings: Simultaneous monitoring of dozens to hundreds of neurons using techniques like two-photon calcium imaging, multi-electrode arrays, or Neuropixels [17] [18] [21]

- Structured Behavioral Tasks: Tasks with well-defined cognitive processes (decision-making, motor planning, memory) to link neural dynamics to computation [21]

- Causal Perturbations: Techniques like optogenetics or electrical stimulation to test hypotheses about dynamical mechanisms [18]

Protocol: Measuring Neural Dynamics with Two-Photon Imaging and Optogenetics

This protocol measures neural population dynamics in mouse cortex using two-photon calcium imaging combined with two-photon holographic optostimulation [17]:

- Surgical Preparation: Prepare transgenic mice expressing calcium indicators (e.g., GCaMP) and channelrhodopsin in excitatory neurons.

- Neural Recording: Record neural population activity at 20Hz using two-photon calcium imaging of a 1mm×1mm field of view containing 500-700 neurons [17].

- Photostimulation Design: Define 100 unique photostimulation groups, each targeting 10-20 randomly selected neurons [17].

- Trial Structure: For each trial:

- Deliver a 150ms photostimulus to a selected neuron group

- Follow with a 600ms response period before next trial begins

- Repeat for ~2000 trials across 25 minutes [17]

- Data Preprocessing: Extract calcium traces from recorded images and convert to firing rate estimates.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply GPFA or PCA to obtain low-dimensional neural trajectories.

- Dynamical Modeling: Fit dynamical systems models (e.g., low-rank autoregressive models) to the neural trajectories [17].

Protocol: Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) Constraint Testing

This protocol tests constraints on neural trajectories using a BCI paradigm in non-human primates [21]:

- Neural Recording: Implant multi-electrode array in motor cortex and record from ~90 neural units [21].

- State Extraction: Transform neural activity into 10D latent states using causal Gaussian Process Factor Analysis (GPFA) [21].

- BCI Mapping: Create intuitive "movement-intention" mapping that projects 10D latent states to 2D cursor position.

- Behavioral Task: Train animals to perform two-target BCI task moving cursor between diametrically opposed targets.

- Trajectory Analysis: Identify natural neural trajectories during successful task performance.

- Separation-Maximizing Projection: Find 2D projection that maximizes separation between A-to-B and B-to-A trajectories.

- Flexibility Testing: Challenge animals to produce neural trajectories in time-reversed order or follow prescribed paths in neural state space [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools for Neural Population Dynamics Research

| Tool/Technique | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Two-Photon Calcium Imaging | Records activity from hundreds to thousands of neurons simultaneously with cellular resolution | Monitoring neural population dynamics in rodent cortex during behavior [17] |

| Multi-Electrode Arrays | Records extracellular action potentials from dozens to hundreds of neurons | Investigating motor cortex dynamics during primate reaching and BCI tasks [21] |

| Two-Photon Holographic Optogenetics | Precisely stimulates experimenter-specified groups of individual neurons | Causal perturbation of neural populations to test dynamical models [17] |

| Dimensionality Reduction Algorithms (PCA, GPFA) | Extracts low-dimensional manifolds from high-dimensional neural data | Identifying neural trajectories underlying cognitive processes [18] [21] |

| Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) Models | Models nonlinear neural dynamics and generates testable predictions | Theorizing about computational mechanisms implemented by neural circuits [18] |

| Geometric Deep Learning (MARBLE) | Learns interpretable representations of neural dynamics on manifolds | Comparing neural computations across animals and conditions [19] [20] |

Applications in Cognitive and Clinical Neuroscience

Revealing Computational Mechanisms

Neural state space analysis has provided insights into diverse cognitive functions:

- Decision-Making: Neural trajectories in parietal and prefrontal cortex exhibit dynamics consistent with evidence accumulation toward decision boundaries [16] [18]

- Working Memory: Persistent neural states implement memory maintenance through attractor dynamics [16] [18]

- Motor Control: Motor cortex trajectories follow consistent paths that correspond to movement kinematics [21]

- Semantic Cognition: Semantic knowledge is organized in attractor landscapes where concept similarity reflects neural state proximity [22]

Clinical and Translational Applications

Understanding neural population dynamics holds promise for:

- Brain-Machine Interfaces: Decoding neural trajectories enables more naturalistic prosthetic control [21]

- Neurological Disorders: Aberrant neural dynamics may underlie conditions like Parkinson's disease, schizophrenia, and epilepsy

- Drug Development: Assessing how pharmacological interventions affect neural dynamics could provide new therapeutic evaluation metrics

Integration with Neural Population Dynamics Optimization

The visualization and analysis of neural state spaces directly informs the development of Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithms (NPDOA) [5]. These brain-inspired meta-heuristic optimization methods implement three key strategies derived from neural population principles:

- Attractor Trending Strategy: Drives solutions toward optimal decisions, ensuring exploitation capability [5]

- Coupling Disturbance Strategy: Deviates solutions from attractors through coupling mechanisms, improving exploration ability [5]

- Information Projection Strategy: Controls communication between solution populations, enabling transition from exploration to exploitation [5]

This bio-inspired approach demonstrates how principles extracted from neural state space analysis can inform algorithm development in other domains, creating a virtuous cycle between neuroscience and computational optimization.

Neural state spaces provide a powerful framework for visualizing and analyzing population activity and trajectories. The population doctrine—that neural computation occurs at the level of populations rather than individual neurons—has reshaped modern neuroscience [16]. By combining large-scale neural recordings with sophisticated analytical techniques, researchers can now identify low-dimensional manifolds, track neural trajectories, and characterize the dynamical flow fields that implement neural computation.

These approaches have revealed fundamental constraints on neural activity [21] and provided insights into how cognitive processes emerge from network-level dynamics. As analytical methods like MARBLE continue to advance [19] [20], and as recording technologies enable even larger-scale monitoring of neural populations, state space analysis will undoubtedly yield further insights into the computational principles of brain function.

The integration of neural state space analysis with optimization algorithms further demonstrates the bidirectional exchange between neuroscience and computer science, where principles extracted from brain function can inspire novel computational methods with broad applicability [5].

Neural population dynamics represent a fundamental framework for understanding how collective neural activity gives rise to cognition. This technical review examines the mechanisms by which neural populations support three core cognitive functions: decision-making, motor control, and working memory. We explore how dynamics emerge from circuit-level interactions and how these processes are increasingly being formalized through optimization algorithms such as the Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA). By synthesizing recent experimental and computational advances, we provide a comprehensive overview of population coding principles, their manifestation across brain regions, and their implications for developing brain-inspired computational methods. The integration of neuroscientific findings with optimization frameworks offers promising avenues for both understanding neural computation and advancing artificial intelligence.

Neural population dynamics refer to the time-varying patterns of activity across ensembles of neurons that collectively encode information and drive behavior. Rather than focusing on single-neuron responses, this approach examines how cognitive representations emerge from the coordinated activity of neural populations [22]. Population dynamics provide a mechanistic link between synaptic-level processes and system-level cognitive functions, operating through low-dimensional manifolds that constrain neural activity trajectories [3].

The theoretical foundation of population dynamics originates from the understanding that representations in the central nervous system are encoded as patterns of activity involving highly interconnected neurons distributed across multiple brain regions [22]. These dynamics are characterized by several key properties: (1) trajectories in state space that evolve over time during cognitive processes, (2) attractor states that represent stable network configurations corresponding to specific representations or decisions, and (3) transitions between states that implement cognitive operations such as decision formation or memory recall [24].

Recent methodological advances have enabled unprecedented access to population-level activity through large-scale electrophysiology, calcium imaging, and fMRI, revealing that neural dynamics operate on multiple timescales and are distributed brain-wide rather than being confined to specific regions [25]. This distributed nature suggests that cognitive functions emerge from interactions across multiple neural systems, each contributing distinct computational properties to the overall process.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Frameworks

Population Coding and Representation

In population coding frameworks, information is represented not by individual neurons but by patterns of activity across neural ensembles. This distributed representation provides robustness to noise and enables complex computations through population vectors and basis functions [22]. The mathematics underlying these representations typically involves high-dimensional state spaces where each dimension corresponds to the activity of one neuron, with cognitive processes mapping to trajectories through this space.

A key concept is the neural manifold—a low-dimensional subspace that captures the majority of task-relevant variance in population activity. Within this manifold, different cognitive states correspond to distinct locations, and cognitive operations correspond to movements through the manifold [3]. Formally, if we represent a population of N neurons' activity as a vector x(t) = [x₁(t), x₂(t), ..., x_N(t)]^T, the neural manifold hypothesis states that these points lie near a d-dimensional subspace where d ≪ N.

Dynamical Systems Approaches

Neural population dynamics are frequently modeled using dynamical systems theory, which describes how neural states evolve over time according to differential equations of the form:

[ \frac{dx}{dt} = F(x, u, t) ]

where x represents the neural state, u represents inputs, and F defines the dynamics [24]. These equations can capture various dynamical regimes including fixed points (attractors), limit cycles, and chaotic dynamics, each of which may subserve different cognitive functions.

Attractor dynamics are particularly important for understanding cognitive functions such as working memory and decision-making. In these models, basins of attraction correspond to different memory states or decision alternatives, with the depth of these basins determining the stability of representations [24]. Noise-driven transitions between attractors can model stochastic decision processes or memory errors.

Table 1: Key Mathematical Frameworks for Neural Population Dynamics

| Framework | Core Principle | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attractor Networks | Dynamics converge to stable states (attractors) | Working memory, decision-making | Often requires fine-tuning of parameters |

| Linear Dynamical Systems | Dynamics approximated as linear transformations | Dimensionality reduction, neural decoding | May oversimplify nonlinear neural dynamics |

| Nonlinear Oscillators | Coupled oscillators with nonlinear interactions | Motor control, rhythmic movements | Complex analysis, many parameters |

| Gaussian Processes | Probabilistic framework for neural trajectories | Modeling uncertainty in neural dynamics | Computationally intensive for large populations |

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA)

The NPDOA represents a novel brain-inspired metaheuristic that formalizes principles of neural population dynamics into an optimization framework [5]. This algorithm implements three core strategies derived from neural systems:

Attractor trending strategy: Drives neural populations toward optimal decisions, ensuring exploitation capability by converging toward stable states associated with favorable decisions.

Coupling disturbance strategy: Deviates neural populations from attractors through coupling with other neural populations, improving exploration ability by disrupting convergence to suboptimal states.

Information projection strategy: Controls communication between neural populations, enabling transition from exploration to exploitation by regulating information transmission.

In NPDOA, each decision variable represents a neuron, with its value corresponding to the neuron's firing rate. The algorithm simulates activities of interconnected neural populations during cognition and decision-making, with neural states transferring according to neural population dynamics [5]. This framework provides a powerful approach for solving complex optimization problems while simultaneously offering insights into neural computation principles.

Decision-Making

Neural Mechanisms of Evidence Accumulation

Decision-making involves gradually accumulating sensory evidence toward a threshold that triggers a choice. This process is implemented in neural circuits through ramping activity that integrates evidence over time [24]. Neurophysiological studies across species demonstrate that during perceptual decisions, neural populations in parietal, prefrontal, and premotor cortices exhibit firing rates that gradually increase until reaching a decision threshold, at which point a choice is initiated [24] [25].

The dynamics of decision formation can be visualized in state space as a trajectory moving from an initial undecided state toward decision-selective attractor states [24]. The speed and trajectory of this movement depend on both the strength of sensory evidence and the architecture of the underlying neural circuits. In such frameworks, reaction time differences and accuracy trade-offs emerge naturally from the dynamics of the evidence accumulation process.

Brain-wide studies in mice performing visual change detection tasks reveal that evidence integration occurs not only in traditional decision areas but distributed across most brain regions, including frontal cortex, thalamus, basal ganglia, midbrain, and cerebellum [25]. This suggests highly parallelized evidence accumulation mechanisms rather than serial processing through a limited number of areas.

Experimental Protocols for Studying Decision Dynamics

Key experiments investigating decision-making dynamics often employ perceptual decision tasks where subjects report judgments about sensory stimuli while neural activity is recorded. A classic paradigm is the random-dots motion (RDM) direction discrimination task, where subjects judge the net direction of motion in a dynamic dot display [24]. The difficulty is controlled by varying the motion coherence, allowing researchers to examine how evidence quality affects neural dynamics.

Analysis methods include:

- Single-neuron tuning analysis: Examining how firing rates of individual neurons correlate with stimulus features or choices.

- Population decoding: Using pattern classifiers to read out decision variables from population activity.

- Dynamical systems analysis: Fitting dynamical models to neural trajectories to identify underlying computational principles.

Recent technical advances enable large-scale recordings across multiple brain regions simultaneously during decision tasks. For example, Neuropixels probes allow monitoring of thousands of neurons across the mouse brain, revealing distributed representations of decision variables [25]. These experiments typically involve:

- Training animals on decision tasks with controlled sensory evidence

- Implanting electrodes or performing calcium imaging across multiple regions

- Recording neural activity during task performance

- Analyzing temporal dynamics of evidence representation using generalized linear models or dimensionality reduction techniques

Diagram 1: Neural Dynamics of Decision-Making

Table 2: Brain Regions Implicated in Decision-Making and Their Contributions

| Brain Region | Contribution to Decision-Making | Key Dynamics | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Posterior Parietal Cortex | Evidence accumulation, sensorimotor transformation | Ramping activity toward decision threshold | Monkey neurophysiology during RDM tasks [24] |

| Prefrontal Cortex | Executive control, rule representation, value coding | Stable working memory representations, decision-related activity | Monkey and human recording studies [24] [26] |

| Premotor Cortex | Action selection, motor preparation | Choice-selective activity before movement | Mouse brain-wide recordings [25] |

| Striatum | Action valuation, selection | Activity correlated with chosen value, action selection | Mouse fMRI and electrophysiology [25] |

Working Memory

Stable and Dynamic Memory Representations

Working memory (WM)—the ability to maintain and manipulate information over short periods—relies on both stable and dynamic neural population codes. Traditional models proposed that WM is maintained through persistent activity in prefrontal cortex (PFC) neurons [26]. However, recent evidence reveals a more complex picture where WM representations can transform and evolve over the delay period while still preserving information.

Human fMRI studies using multivariate decoding have demonstrated coexisting stable and dynamic neural representations of WM content across multiple cortical visual field maps [26]. Surprisingly, these studies found greater dynamics in early visual cortex compared to high-level visual and frontoparietal cortex, challenging traditional hierarchical models of WM maintenance.

Population dynamics during WM tasks often exhibit representational reformatting, where the neural code transforms into formats more proximal to upcoming behavior. For example, during a memory-guided saccade task, V1 population activity initially encodes a narrowly tuned activation centered on the peripheral memory target, which then spreads inward toward foveal locations, forming a vector along the trajectory of the forthcoming memory-guided saccade [26]. This suggests that WM representations are not static but actively transform to support subsequent actions.

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Working Memory Dynamics

Standard protocols for investigating WM dynamics include:

- Delayed response tasks: Subjects encode a stimulus, maintain it during a delay period, then respond based on the memorized information.

- Continuous report tasks: Subjects reproduce continuous features (e.g., orientation, color) of remembered stimuli.

- Sequence memory tasks: Subjects remember and reproduce sequences of items or locations.

Analysis approaches focus on:

- Temporal decoding: Training classifiers at different time points to assess how information content changes over time

- Neural trajectory analysis: Visualizing population activity paths in low-dimensional space

- Cross-temporal generalization: Testing whether classifiers trained at one time point generalize to other time points, indicating stable representations

Advanced neuroimaging techniques such as population receptive field mapping have made these neural dynamics interpretable by relating BOLD signals to underlying neural representations [26]. These methods allow researchers to visualize how specific visual features are represented and transformed in neural populations during WM maintenance.

Diagram 2: Working Memory Dynamics and Reformatting

Motor Control

From Preparation to Execution

Motor control involves the transformation of movement intentions into precisely coordinated muscle activations. Neural population dynamics play a crucial role in this process, with distinct dynamical regimes for movement preparation versus execution [25]. During preparation, neural populations in motor and premotor cortices exhibit activity patterns that encode upcoming movements while the body remains still, demonstrating a clear dissociation between movement planning and execution.

Brain-wide recordings in mice performing decision-making tasks reveal that preparatory activity is distributed across dozens of brain regions, not just traditional motor areas [25]. This preparatory activity forms a neural subspace that is distinct from the subspace active during movement execution, allowing for independent control of preparation and implementation. The transition from preparation to execution is marked by a collapse of the preparatory subspace and activation of execution-related patterns.

The relationship between evidence accumulation and motor preparation is particularly revealing. In areas that accumulate evidence, shared population activity patterns encode both visual evidence and movement preparation, with these representations being distinct from movement-execution dynamics [25]. This suggests that learning aligns evidence accumulation with action preparation across distributed brain regions.

Experimental Approaches to Motor Dynamics

Studying motor dynamics requires techniques that can capture both planning and execution phases with high temporal precision. Common approaches include:

- Reach-to-target tasks: Subjects move their hand from a starting position to targets, allowing study of trajectory formation and correction.

- Postural maintenance tasks: Subjects maintain specific postures against perturbations, revealing stability mechanisms.

- Sequential movement tasks: Subjects execute movement sequences, illuminating chunking and timing mechanisms.

Analysis methods focus on:

- Neural manifolds: Identifying low-dimensional subspaces that capture movement-related variance

- Condition-invariant dynamics: Discovering neural patterns that are consistent across similar movements

- Neural trajectories: Tracking the evolution of population activity through state space during movement

Recent technical advances such as markerless motion capture combined with large-scale neural recordings enable comprehensive investigation of how neural dynamics relate to detailed kinematic features [25]. These approaches reveal that motor cortex does not simply represent movement parameters but implements dynamics that generate appropriate temporal patterns for movement control.

Analysis Methods and Computational Tools

Advanced Analysis Techniques

Understanding neural population dynamics requires specialized analytical approaches that can extract meaningful patterns from high-dimensional neural data. Several key methods have emerged:

Dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Gaussian Process Factor Analysis (GPFA), and variational autoencoders (VAEs) identify low-dimensional structure in neural population activity [3]. These methods project high-dimensional neural data into meaningful subspaces where dynamics can be visualized and interpreted.

Manifold learning approaches including UMAP, t-SNE, and the recently developed MARBLE (MAnifold Representation Basis LEarning) framework go beyond linear dimensionality reduction to capture nonlinear structure in neural dynamics [3]. MARBLE specifically decomposes on-manifold dynamics into local flow fields and maps them into a common latent space using unsupervised geometric deep learning.

Dynamical systems modeling fits formal models to neural data to identify underlying computational principles. These include linear dynamical systems, switching linear dynamical systems, and recurrent neural network models that can capture both the continuous evolution and discrete transitions in neural activity [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Studying Neural Population Dynamics

| Tool/Category | Function/Purpose | Example Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuropixels Probes | High-density electrophysiology recording from hundreds of neurons simultaneously | Brain-wide recording of decision-making in mice [25] | Requires specialized implantation surgery and data processing pipelines |

| Two-Photon Calcium Imaging | Optical recording of neural population activity with cellular resolution | Monitoring cortical population dynamics during learning | Limited penetration depth, typically cortical |

| Virus-Based Tools (GCaMP, jGCaMP) | Genetically encoded calcium indicators for monitoring neural activity | Large-scale population imaging in specific cell types | Expression time, potential toxicity at high levels |

| Dimensionality Reduction Software | Algorithms for identifying low-dimensional neural manifolds | PCA, UMAP, MARBLE for analyzing population dynamics [3] | Choice of algorithm depends on data structure and scientific question |

| Neural Decoding Tools | Classifiers for extracting information from population activity | Readout of decision variables or movement intentions | Cross-validation essential to avoid overfitting |

| Optogenetics | Precise manipulation of specific neural populations | Causal testing of population dynamics hypotheses | Limited to genetically targeted populations, potential network effects |

Methodological Framework for Experimental Investigation

Integrated Experimental Design

Comprehensive investigation of neural population dynamics across cognitive functions requires carefully designed experiments that combine behavioral tasks with neural recordings and perturbations. An effective experimental framework includes:

Task design with parametric manipulation: Systematic variation of sensory evidence, memory demands, or motor requirements to probe different dynamical regimes.

Large-scale neural recording: Simultaneous monitoring of neural activity across multiple brain regions using Neuropixels, calcium imaging, or other high-yield techniques.

Population-level analysis: Application of dimensionality reduction, decoding, and dynamical systems analysis to identify population codes.

Causal manipulation: Optogenetic or chemogenetic perturbation of specific neural populations to test necessity and sufficiency.

For example, a comprehensive experiment might involve training mice on a memory-guided decision task while recording from dozens of brain regions using Neuropixels, then applying dimensionality reduction to identify neural manifolds, and finally using optogenetics to perturb specific population activity patterns at key decision points [25].

Data Analysis Pipeline

A standardized analysis pipeline for population dynamics typically includes:

Preprocessing: Spike sorting, calcium trace deconvolution, or BOLD signal preprocessing to extract neural activity.

Dimensionality reduction: Application of PCA, FA, or nonlinear methods to identify low-dimensional neural manifolds.

Neural decoding: Training classifiers or regression models to read out task variables from neural activity.

Dynamical systems analysis: Fitting dynamical models to neural trajectories and identifying fixed points, limit cycles, or other dynamical features.

Cross-condition alignment: Using methods like CCA or MARBLE to align neural representations across sessions, subjects, or conditions [3].

This pipeline enables researchers to move from raw neural data to interpretable dynamical portraits of cognitive processes, facilitating comparison across studies and species.

Neural population dynamics provide a powerful framework for understanding how distributed neural activity gives rise to cognition. Across decision-making, working memory, and motor control, we observe consistent principles: cognitive representations emerge from trajectories through low-dimensional neural manifolds, distributed brain regions contribute to cognitive computations, and learning shapes neural dynamics to support task performance.

The formalization of these principles in optimization algorithms like NPDOA demonstrates the bidirectional value between neuroscience and computational methods [5]. Neuroscience provides inspiration for novel algorithms, while computational formalization offers testable hypotheses about neural function.

Future research directions include:

- Cross-species comparisons of population dynamics to identify conserved computational principles

- Longitudinal studies of how neural dynamics change during learning and development

- Integration of molecular and systems levels to understand how microcircuit properties give rise to population dynamics

- Clinical applications of dynamics-based approaches to diagnose and treat neurological disorders

As recording technologies continue to improve, providing access to larger neural populations across more brain regions, population dynamics approaches will likely play an increasingly central role in unraveling the neural basis of cognition.

Key Experimental Evidence from Multiple Brain Regions

Understanding how the brain makes decisions requires studying how groups of neurons, or neural populations, work together across different brain areas. Research on neural population dynamics seeks to uncover the computational principles that govern these complex, distributed processes. A central focus in this field is the development of optimization algorithms that can explain how neural circuits efficiently transform sensory information into decisions and actions. This whitepaper synthesizes key experimental evidence from multiple brain regions, highlighting how diverse neural populations implement core computations, with particular relevance for developing novel therapeutic strategies in neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Quantitative Evidence from Key Brain Regions

Studies recording from multiple brain areas simultaneously have revealed that evidence accumulation is not confined to a single "decision center" but is a distributed process implemented by distinct neural dynamics in different regions.

Table 1: Distinct Evidence Accumulation Signatures Across Rat Brain Regions [27]

| Brain Region | Abbreviation | Key Finding | Characteristic Neural Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior-dorsal Striatum | ADS | Near-perfect accumulation of sensory evidence. | Graded representation of accumulated evidence; reflects decision vacillation. |

| Frontal Orienting Fields | FOF | Unstable accumulator favoring early evidence. | Activity appears categorical but is driven by unstable integration sensitive to early input. |

| Posterior Parietal Cortex | PPC | Graded evidence accumulation. | Weaker correlates of graded accumulation compared to ADS. |

| Whole-Animal Behavior | (N/A) | Distinct from all recorded neural models. | Suggests behavioral-level accumulation is constructed from multiple neural-level accumulators. |

Table 2: Brain-Wide Encoding of Decision Variables in Mice [25]

| Neural Encoding Type | Prevalence Across Brain Regions | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|

| Sensory Evidence (Stimulus) | Sparse (5-45% of neurons), but distributed. | Found in visual areas, frontal cortex, basal ganglia, hippocampus, cerebellum; absent in orofacial motor nuclei. |

| Lick Preparation | Substantial fraction, distributed globally. | Activity build-up preceding movement, observed across dozens of regions. |

| Lick Execution | Widespread (>50% of neurons). | Dominant signal across the brain, indicating global recruitment for action. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The findings summarized above were made possible by rigorous experimental designs and advanced recording techniques.

- Subject and Training: Data were collected from 11 well-trained, food-restricted rats performing at a high level.

- Task Design: Rats listened to two simultaneous streams of randomly timed auditory clicks from left and right speakers. After the click train ended, they were required to orient to the side that had more clicks to receive a reward.

- Data Collection and Analysis: Researchers analyzed 37,179 behavioral choices and recordings from 141 neurons from the FOF, PPC, and ADS. Only neurons with significant tuning for choice during the stimulus period (two-sample t-test, p<0.01) were included.

- Computational Modeling: A unified latent variable model was developed to infer probabilistic evidence accumulation models jointly from choice data, neural activity, and precisely controlled stimuli. This framework allowed for the direct comparison of accumulation models that best described neural activity in each region versus the model that best described the animal's choices.

- Subject and Training: Head-fixed, food-restricted mice were trained on a visual change detection task. They had to report a sustained increase in the speed of a visual grating by licking a reward spout, while remaining stationary during evidence presentation.

- Task Design: The stimulus speed fluctuated noisily, and mice had to integrate this ambiguous evidence over time (3-15.5 seconds). The design dissociated sensory evidence from early movement-related activity.

- Data Collection: Dense recordings were performed using Neuropixels probes from 15,406 units across 51 brain regions (cortex, basal ganglia, thalamus, midbrain, cerebellum, etc.), combined with high-speed videography of face and pupil movements.

- Data Analysis: Single-cell Poisson generalized linear models (GLMs) were used to identify neurons significantly encoding visual evidence, lick preparation, and lick execution. A cross-validated nested test held out a predictor of interest to assess its unique contribution to neural activity.

Visualization of Core Concepts

Unified Modeling of Neural and Behavioral Data

Distributed Evidence-to-Action Transformation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Neural Population Dynamics Research

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Neuropixels Probes | High-density silicon electrodes for simultaneous recording from hundreds to thousands of neurons across multiple brain regions [25]. |

| Poisson Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) | Statistical models for identifying how task variables (sensory evidence, choice, action) are encoded in neural spiking activity [25]. |

| Latent Variable Models | Computational framework for inferring shared, unobserved variables (e.g., accumulated evidence) that jointly explain neural activity and behavior [27]. |

| Task-Control Software | Precisely controlled presentation of sensory stimuli (e.g., auditory clicks, visual gratings) and behavioral contingency management [27] [25]. |

| High-Speed Videography | Tracking of facial movements and pupil dynamics to correlate neural activity with nuanced behaviors and arousal states [25]. |

Key Algorithms and Models: From Theory to Biomedical Application

Low-Rank Linear Dynamical Systems for Efficient Dimensionality Reduction

Low-rank linear dynamical systems (LDS) represent a powerful computational framework for extracting interpretable, low-dimensional latent dynamics from high-dimensional neural population recordings. These models address a fundamental challenge in modern neuroscience: understanding how coordinated activity across many neurons gives rise to brain function, while overcoming the curse of dimensionality that plagues direct analysis of high-dimensional neural data. The core principle involves constraining the dynamics of a neural population to evolve within a low-dimensional subspace, characterized by a low-rank connectivity matrix that captures the essential computational structure of the circuit.

The mathematical foundation of low-rank LDS begins with the state-space formulation, where observed neural activity (\bm{x}(t) \in \mathbb{R}^N) from N neurons is governed by latent dynamics (\bm{z}(t) \in \mathbb{R}^K) with K << N. The system evolves according to:

[\bm{z}(t) = \bm{A}\bm{z}(t-1) + \bm{\epsilon}(t)] [\bm{x}(t) = \bm{C}\bm{z}(t) + \bm{\omega}(t)]

where (\bm{A} \in \mathbb{R}^{K \times K}) is the state transition matrix, (\bm{C} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times K}) is the observation matrix, and (\bm{\epsilon}(t)), (\bm{\omega}(t)) represent process and observation noise respectively. The low-rank constraint is implemented by factorizing the connectivity matrix (\bm{W} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times N}) as (\bm{W} = \bm{U}\bm{V}^T), where (\bm{U}, \bm{V} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times K}) with K << N. This factorization dramatically reduces the number of parameters from O(N²) to O(NK), enabling robust estimation from limited data while revealing the underlying computational structure [28].

In the broader context of neural population dynamics optimization research, low-rank LDS provides a principled approach to solving the inverse problem of inferring latent dynamics and connectivity from partially observed neural activity. Recent advances have focused on extending these models to capture more complex neural phenomena, including disentangled representations, cross-population interactions, and nonlinear dynamics, while maintaining interpretability and computational efficiency.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Frameworks

Core Mathematical Principles

The theoretical underpinnings of low-rank LDS stem from dynamical systems theory and statistical inference. The low-rank constraint on neural connectivity reflects a fundamental organizational principle of neural circuits: that high-dimensional neural activity is driven by a limited number of collective modes or neural ensembles. Mathematically, this is expressed through the eigen-decomposition of the connectivity matrix (\bm{W} = \sum{i=1}^K \lambdai \bm{u}i \bm{v}i^T), where each mode (\lambdai) represents a dynamical timescale with corresponding spatial pattern (\bm{u}i) and input projection (\bm{v}_i) [28].

From a statistical perspective, learning low-rank LDS involves maximizing the likelihood of observed neural data under the model constraints. The complete-data log-likelihood for a sequence of T observations is given by:

[\mathcal{L}(\theta) = \sum_{t=1}^T \log p(\bm{x}(t) | \bm{z}(t); \bm{C}) + \log p(\bm{z}(t) | \bm{z}(t-1); \bm{A}) - \text{regularization terms}]

where (\theta = {\bm{A}, \bm{C}, \bm{Q}, \bm{R}}) represents all model parameters, with (\bm{Q}) and (\bm{R}) being noise covariance matrices. The low-rank constraint is typically enforced through regularization or explicit parameterization, such as the Disentangled Recurrent Neural Network (DisRNN) framework which encourages group-wise independence among latent dimensions [28].

Disentangled Low-Rank Representations