Neural Population Dynamics: From Circuit Computation to Novel Therapeutic Targets

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of neural population dynamics, a foundational framework for understanding how brain-wide networks perform computations driving cognition and behavior.

Neural Population Dynamics: From Circuit Computation to Novel Therapeutic Targets

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of neural population dynamics, a foundational framework for understanding how brain-wide networks perform computations driving cognition and behavior. We cover core principles, from dynamical systems theory and low-dimensional manifolds to state-of-the-art methodologies like privileged knowledge distillation and large-scale modeling. The content critically addresses challenges in interpreting dynamics and optimizing models, while presenting validation through comparative studies across brain regions and behaviors. Finally, we discuss the translational potential of this framework for developing targeted interventions in neurological and psychiatric disorders, offering a roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals.

The Language of the Brain: Core Principles of Neural Population Dynamics

Defining Computation Through Neural Population Dynamics (CTD)

Computation Through Neural Population Dynamics (CTD) posits that the brain performs computations through the coordinated, time-varying activity of populations of neurons, rather than through the isolated firing of single cells. This framework treats the trajectory of neural population activity in a high-dimensional state space as the fundamental medium of computation, underlying functions from motor control to cognition [1]. This whitepaper synthesizes the core principles, analytical approaches, and key experimental evidence that establish CTD as a central paradigm for understanding brain function, with implications for research and therapeutic development.

Theoretical Foundations of Neural Population Dynamics

The CTD framework is grounded in the observation that cognitive functions and behaviors are reliably associated with stereotyped sequences of neural population activity. These sequences, or neural trajectories, are thought to be generated by the intrinsic structure of neural circuits and can implement computations necessary for goal-directed behavior [2] [1].

A key principle is that these dynamics are often obligatory, or constrained by the underlying neural circuitry. A seminal brain-computer interface (BCI) study demonstrated that non-human subjects could not voluntarily reverse the natural sequences of neural activity in their motor cortex, even with explicit feedback and rewards. This provides causal evidence that stereotyped activity sequences are a fundamental property of the network's wiring, not merely a transient epiphenomenon [2].

Furthermore, neural population codes are organized at multiple spatial scales. Local population activity, characterized by heterogeneous and sparse firing, is modulated by large-scale brain states. This multi-scale organization suggests that local information representations and their computational capacities are state-dependent [3].

A Computational Framework for Population Dynamics

Analytical Foundations: From Data to Dynamics

The application of the CTD framework requires reducing high-dimensional neural recordings to a lower-dimensional latent space where computations can be visualized and analyzed.

- Dynamical Systems Theory: This mathematical framework provides the tools to describe how the state of a neural population (its point in state space) evolves over time. Critical concepts include the state space (a coordinate system where each axis represents the activity of one neuron or a latent factor), neural trajectories (the path of the population state through this space), and attractors (states or trajectories toward which the dynamics evolve) [1].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Techniques such as Gaussian-process factor analysis (GPFA) are used to extract smooth, low-dimensional trajectories from noisy, high-dimensional spike train data, revealing the underlying computational structure [1].

Core Computational Motifs

Research has identified several key computational motifs implemented by population dynamics:

- Linearly Separable Dynamics for Decoding: Complex neural trajectories can often be decoded using simple linear readouts, enabling downstream brain areas to extract behaviorally relevant information [1].

- Mixed Selectivity and High-Dimensional Representations: Neurons with nonlinear mixed selectivity—responding to a combination of task variables in a non-additive way—create a high-dimensional neural representation. This high dimensionality enriches the population code and facilitates linear decoding by downstream neurons [3].

- Optimal Inference via Recurrent Dynamics: Categorical perception can be implemented by recurrent neural networks that approximate optimal probabilistic inference. These networks dynamically integrate bottom-up sensory inputs with top-down categorical priors to form a perceptual estimate [4].

Table 1: Key Computational Motifs in Neural Population Dynamics

| Computational Motif | Functional Role | Neural Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed-Point Attractors | Stability, memory maintenance | Persistent activity patterns in working memory networks |

| Limit Cycles | Rhythm generation, timing | Central pattern generators for locomotion |

| Neural Trajectories | Sensorimotor transformation, decision-making | Stereotyped sequences of activity in motor and parietal cortex |

| High-Dimensional Manifolds | Mixed selectivity, complex representation | Heterogeneous tuning in association cortex |

Experimental Evidence and Protocols

A Protocol for Testing the Obligatory Nature of Neural Dynamics

The following protocol is derived from the BCI experiment that causally tested for one-way neural paths [2].

- Objective: To determine whether naturally occurring sequences of neural population activity are obligatory and cannot be voluntarily overridden.

- Experimental Setup:

- Subject Preparation: Implant a multi-electrode array in the primary motor cortex (M1) of a non-human primate (e.g., rhesus macaque).

- Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) Calibration:

- Record population activity during a natural motor task (e.g., reaching).

- Use dimensionality reduction (e.g., GPFA) to identify the native, stereotyped neural trajectories that precede movement.

- Map the neural population activity to the velocity of a computer cursor.

- Experimental Paradigm:

- Control Condition: The subject performs a standard center-out task using the BCI cursor, which follows the native neural dynamics.

- Perturbation Condition: The BCI mapping is altered to require a time-reversed version of the native neural trajectory to successfully move the cursor to the target.

- Provide real-time visual feedback of cursor position and a fluid reward for successful target acquisition.

- Key Measurements:

- Behavioral Performance: Success rate and movement time in the control vs. perturbation condition.

- Neural Activity: The actual neural trajectories produced in the perturbation condition are compared to the native and the time-reversed trajectories.

- Expected Outcome: Subjects are unable to produce the time-reversed neural trajectories, even with incentive. The measured trajectories will collapse back onto the native, obligatory paths, supporting the CTD hypothesis [2].

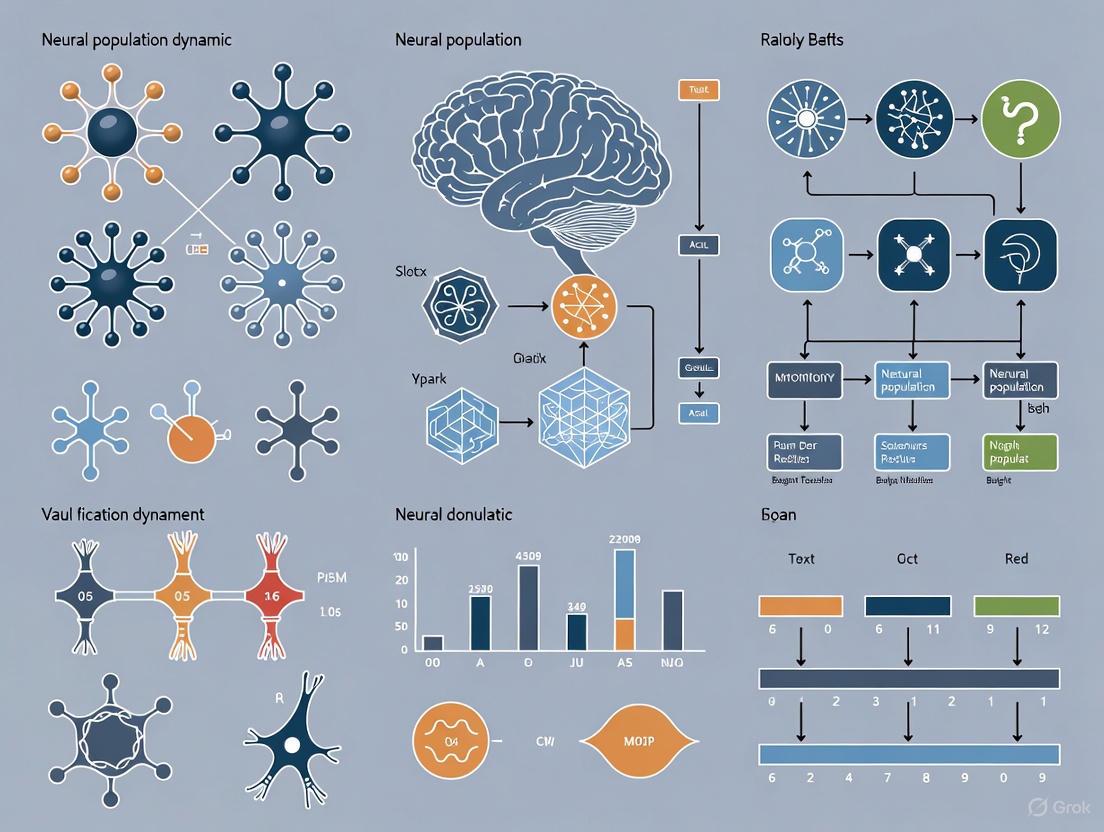

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow and the core finding of this paradigm:

A Protocol for Studying Population Dynamics in Categorical Perception

This protocol is based on the recurrent neural network model used to explain categorical color perception [4].

- Objective: To model how recurrent dynamics between neural populations implement probabilistic inference for categorical perception.

- Network Architecture:

- Hue-Selective Population: A pool of neurons with narrow, homogeneous tuning to different color hues. They receive bottom-up sensory input.

- Category-Selective Population: A pool of neurons with broad tuning, each representing a color category (e.g., "red," "green," "blue"). They receive input from hue-selective neurons.

- Recurrent Connections:

- Lateral connections among hue-selective neurons implement a "continuity prior" (expectation that hue changes slowly).

- Top-down connections from category-selective to hue-selective neurons implement a "categorical prior" (expectation that hues belong to known categories).

- Experimental Simulation:

- Present a dynamic sequence of color stimuli to the model input.

- Record the evolving activity of both the hue-selective and category-selective populations over time.

- Key Measurements:

- The evolution of the population activity vector in the hue-selective population.

- The time at which a category-selective neuron becomes active, signifying a perceptual decision.

- The bias in the hue representation towards the categorical center over time.

- Expected Outcome: The model accounts for neurophysiological phenomena such as the clustering of population representations and temporal evolution of perceptual memory, demonstrating how recurrent dynamics approximate optimal Bayesian inference [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details key methodological tools and computational models essential for research in neural population dynamics.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for CTD Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Application in CTD |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Electrode Arrays (MEAs) | High-density electrodes for simultaneous recording from hundreds of neurons. | Capturing high-dimensional population activity with high temporal resolution [2]. |

| Dimensionality Reduction (GPFA) | Gaussian-process factor analysis; a statistical method for extracting smooth, low-dimensional trajectories from neural data. | Revealing the underlying neural trajectories that are hidden in noisy high-dimensional data [1]. |

| Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) | A real-time system that maps neural activity to an output (e.g., cursor movement). | Performing causal experiments to test the necessity and sufficiency of specific neural dynamics for behavior [2]. |

| Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) Models | Computational models of neural circuits with recurrent connections. | Theorizing and simulating how network connectivity gives rise to dynamics that implement computation [4] [5]. |

| Dynamical Mean-Field Theory (DMFT) | A theoretical framework for analyzing the dynamics of large, heterogeneous recurrent networks. | Understanding how single-neuron properties (e.g., graded-persistent activity) shape and expand the computational capabilities of a network [5]. |

Advanced Topics and Future Directions

The Role of Heterogeneity in Population Dynamics

Neural populations are highly heterogeneous. Traditional mean-field theories often average over this heterogeneity, but recent advances in Dynamical Mean-Field Theory (DMFT) now allow for the analysis of populations with highly diverse neuronal properties. For instance, the incorporation of neurons with graded persistent activity (GPA)—which can maintain firing for minutes without input—shifts the chaos-order transition point in a network and expands the dynamical regime favorable for temporal information computation [5]. This suggests that neural heterogeneity is not mere noise but a critical feature that enhances computational capacity.

Adaptation and Dynamic Coding

Neural populations must encode stimulus features reliably despite continuous changes in other, "nuisance" variables like luminance and contrast. Information-theoretic analyses show that the mutual information between V1 neuron spike counts and stimulus orientation is dependent on luminance and contrast and changes during adaptation. This adaptation does not necessarily maintain information rates but likely keeps the sensory system within its limited dynamic range across a wide array of inputs [6]. This demonstrates how population codes are dynamically adjusted by the recent stimulus history.

A Unified Framework for Brain Function

The CTD framework offers a unifying language for bridging levels of analysis, from single-neuron properties to network-level computation and behavior. By characterizing the lawful evolution of population activity, it provides a path toward a more general theory of how neural circuits give rise to cognition. Future work will focus on linking these dynamics more directly to animal behavior, understanding their development and plasticity, and exploring their disruption in neurological and psychiatric disorders, thereby opening new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

The dynamical systems framework provides a powerful mathematical foundation for understanding how neural computation emerges from the collective activity of neural populations. This approach reveals how low-dimensional computational processes are embedded within high-dimensional neural activity, enabling robust brain function despite representational drift in individual neurons. By treating the state of a neural population as a trajectory in a high-dimensional state space, this framework bridges scales from single neurons to brain-wide circuits, offering profound insights for basic neuroscience and therapeutic development. This technical guide details the core principles, analytical methods, and experimental protocols underpinning this transformative approach to studying brain function.

A dynamical system is formally defined as a system in which a function describes the time dependence of a point in an ambient space [7]. In neuroscience, this framework allows researchers to model the brain's activity as a trajectory through a state space, where the current state evolves according to specific rules to determine future states.

The geometrical definition of a dynamical system is a tuple 〈T, M, f〉 where T represents time, M is a manifold representing all possible states, and f is an evolution rule that specifies how states change over time [7]. When applied to neural systems, the manifold M corresponds to the possible activity states of a neural population, with dimensions representing factors such as firing rates of individual neurons or latent variables.

Key Mathematical Concepts:

- State Space: A geometric space where each point represents a possible state of the neural population

- Trajectories: Paths through state space representing the temporal evolution of population activity

- Attractors: Preferred states toward which the system evolves, potentially corresponding to cognitive states or behavioral outputs

- Manifolds: Lower-dimensional subspaces within the high-dimensional neural state space that capture structured patterns of activity

Core Theoretical Principles: From Single Neurons to Population Dynamics

The Latent Computing Paradigm

Recent theoretical work establishes that neural computations are implemented by latent processing units—core elements for robust coding embedded within collective neural dynamics [8]. This framework yields five key principles:

- Low-dimensional computation generates high-dimensional dynamics: Neural computations that are low-dimensional can nevertheless generate the high-dimensional neural dynamics observed experimentally [8]

- Inherent coding redundancy: The manifolds defined by neural dynamical trajectories exhibit inherent coding redundancy as a direct consequence of the universal computing capabilities of the underlying dynamical system [8]

- Linear readouts suffice for behavior: Linear decoders of neural population activity can optimally subserve downstream circuits controlling behavioral outputs [8]

- Scale-dependent prediction: Whereas recordings from thousands of neurons may suffice for near-optimal decoding from instantaneous activity patterns, experimental access to millions of neurons may be necessary to predict neural ensemble dynamical trajectories across timescales of seconds [8]

- Robustness to representational drift: Despite variable activity of single cells, neural networks can maintain stable representations of computed variables through latent processing units [8]

Evidence Accumulation as a Model System

Decision-making tasks requiring evidence accumulation provide a compelling demonstration of population dynamics. Different brain regions implement distinct accumulation strategies while collectively supporting behavior [9]:

Table 1: Evidence Accumulation Strategies Across Rat Brain Regions

| Brain Region | Accumulation Strategy | Relation to Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Frontal Orienting Fields (FOF) | Unstable accumulator favoring early evidence | Differs from behavioral accumulator |

| Anterior-dorsal Striatum (ADS) | Near-perfect accumulation | More veracious representation |

| Posterior Parietal Cortex (PPC) | Graded evidence accumulation (weaker than ADS) | Distinct from choice model |

| Whole-Animal Behavior | Stable accumulation | Synthesized from regional strategies |

This regional specialization demonstrates that accumulation at the whole-animal level is constructed from diverse neural-level accumulators rather than a single unified mechanism [9].

Analytical Methods and Computational Tools

State Space Reconstruction and Dimensionality Reduction

The foundational step in analyzing neural population dynamics involves reconstructing the underlying state space from recorded neural activity:

- Data Collection: Simultaneously record from multiple neurons (typically tens to hundreds) during behavior

- State Representation: Represent population state at each time point as a vector of activity (e.g., firing rates)

- Dimensionality Reduction: Apply methods like PCA, GPFA, or LFADS to identify low-dimensional manifolds

- Trajectory Analysis: Examine how population states evolve over time within this reduced space

Dynamical Systems Theory Applications

Phase Space Reconstruction: For a system with unknown equations, time series measurements enable reconstruction of essential functional dynamics through delay embedding [10]. This approach has been successfully applied to physical systems and engineered control systems, and is now being adapted for neuroelectric field analysis [10].

Critical Mathematical Tools:

- Lyapunov exponents: Measure sensitivity to initial conditions

- Bifurcation analysis: Identifies qualitative changes in dynamics with parameter variation

- Attractor reconstruction: Maps stable states in neural state space

- Stability analysis: Determines robustness to perturbation

Figure 1: Analytical Workflow for Neural Population Dynamics

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Evidence Accumulation Task with Multi-region Recording

This protocol enables simultaneous characterization of accumulation strategies across brain regions [9]:

Subjects: 11 rats trained on auditory pulse-based accumulation task Task Structure:

- Animals listen to two simultaneous series of randomly timed auditory clicks from left and right speakers

- After click train ends, animal orients to side with greater number of clicks for reward

- 37,179 behavioral choices analyzed with simultaneous neural recordings

Neural Recording:

- Brain Regions: Posterior Parietal Cortex (PPC), Frontal Orienting Fields (FOF), Anterior-dorsal Striatum (ADS)

- Electrophysiology: 141 neurons total (68 FOF, 25 PPC, 48 ADS)

- Inclusion Criterion: Significant tuning for choice during stimulus period (two-sample t-test, p<0.01)

Analysis Framework:

- Develop latent variable model linking behavior and neural activity

- Fit drift-diffusion models jointly to choice data and neural activity

- Compare accumulation strategies across regions using probabilistic evidence accumulation models

Protocol 2: EEG-Based Dynamical Assessment for Clinical Translation

This protocol adapts dynamical systems analysis for clinical applications using accessible EEG technology [10]:

Participants: Clinical populations with psychiatric disorders + matched controls EEG Acquisition:

- Portable EEG devices for routine clinical settings

- Brief recordings (5-15 minutes) during rest and task conditions

- High-density electrode placement (64-128 channels recommended)

Dynamical Feature Extraction:

- State Space Reconstruction: From multichannel EEG time series

- Lyapunov Exponents: Quantifying system stability and chaos

- Correlation Dimension: Estimating system complexity

- Entropy Measures: Information-theoretic characterization of dynamics

Clinical Integration:

- Combine dynamical features with EHR data and clinical assessments

- Develop risk prediction models using machine learning

- Monitor treatment response through trajectory changes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Neural Population Dynamics Studies

| Item | Function | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| High-density Neural Probes | Simultaneous recording from hundreds of neurons | Neuropixels probes (960 sites); 64-256 channel arrays |

| Electrophysiology Systems | Signal acquisition and processing | 30kHz sampling rate; hardware filtering; spike sorting capability |

| Optogenetic Equipment | Circuit-specific manipulation | Lasers (473nm, 593nm); fiber optics; Cre-driver lines |

| Behavioral Apparatus | Task presentation and monitoring | Auditory/visual stimuli; response ports; reward delivery |

| Computational Resources | Data analysis and modeling | High-performance computing; GPU acceleration; >1TB storage |

| Portable EEG Systems | Clinical translation of dynamics | 64-128 channels; wireless capability; dry electrodes |

| Calcium Imaging Systems | Population activity visualization | Miniature microscopes; GCaMP indicators; fiber photometry |

Applications in Basic Research and Therapeutic Development

Precision Psychiatry Framework

Dynamical systems theory enables a paradigm shift from symptom-based diagnosis to trajectory monitoring in psychiatry [10]. The framework incorporates:

- Quantitative snapshots of neural circuit function from electrophysiological measurements

- Latent neurodynamical features combined with personal and clinical data

- Personalized trajectory monitoring for risk prediction prior to symptom emergence

- Treatment response assessment through changes in neural dynamics

Figure 2: Dynamical Systems Framework for Precision Psychiatry

Drug Development Applications

The dynamical systems framework offers transformative approaches for CNS drug development:

Target Identification:

- Identify pathological neural dynamics associated with specific disorders

- Map circuit-level effects of genetic risk factors

- Discover novel therapeutic targets based on dynamical signatures

Biomarker Development:

- EEG-based dynamical biomarkers for patient stratification

- Treatment response biomarkers based on trajectory changes

- Objective metrics for clinical trial endpoints

Mechanism of Action Studies:

- Characterize drug effects on neural population dynamics

- Identify optimal therapeutic windows through dynamics monitoring

- Understand circuit-level actions of pharmacological agents

Quantitative Data Synthesis

Table 3: Key Quantitative Findings in Neural Population Dynamics Research

| Experimental Finding | Quantitative Result | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Neuron count for decoding | Thousands of neurons suffice for instantaneous decoding; millions may be needed for second-scale trajectory prediction [8] | Guides experimental design for temporal resolution needs |

| Regional accumulation differences | FOF, PPC, and ADS each show distinct accumulation models, all differing from behavioral model [9] | Challenges simple brain-behavior correspondence |

| Choice prediction improvement | Incorporating neural activity reduced uncertainty in moment-by-moment accumulated evidence [9] | Supports unified neural-behavioral modeling |

| Clinical EEG application | Brief (5-15 minute) EEG recordings sufficient for dynamical feature extraction [10] | Enables clinical translation with accessible technology |

| Representational drift robustness | Stable computation maintained despite single-neuron variability [8] | Highlights population-level coding principles |

Future Directions and Technical Challenges

Emerging Methodological Frontiers

Large-Scale Neural Recording: As recording technology advances to simultaneously monitor thousands to millions of neurons, new analytical approaches will be needed to characterize ultra-high-dimensional dynamics [8].

Closed-Loop Interventions: Real-time monitoring of neural population dynamics enables closed-loop therapeutic approaches that intervene when trajectories approach pathological states.

Multi-Scale Integration: A major challenge remains integrating dynamics across spatial and temporal scales, from synaptic-level events to brain-wide network dynamics spanning milliseconds to days.

Clinical Implementation Challenges

Standardization: Developing standardized protocols for dynamical feature extraction across clinical sites requires rigorous validation and harmonization.

Interpretability: Translating complex dynamical metrics into clinically actionable insights remains a significant hurdle.

Accessibility: Making dynamical analysis tools accessible to clinical researchers without specialized mathematical training will be crucial for widespread adoption.

The dynamical systems framework continues to evolve as a unifying language for connecting neural mechanisms to cognitive function and dysfunction. By providing quantitative methods to track how neural population states evolve over time, this approach offers powerful tools for both basic neuroscience and the development of novel therapeutic strategies for brain disorders.

The brain generates complex behavior through the coordinated activity of massive neural populations. An emerging framework posits that this orchestrated activity possesses a low-dimensional structure, constrained to neural manifolds. These manifolds are mathematical subspaces that describe the collective states of a neural population, shaped by intrinsic circuit architecture and extrinsic behavioral demands [11]. This whitepaper explores the neural manifold framework as a crucial paradigm for understanding how distributed brain circuits perform computations. We review fundamental principles, detail experimental and analytical methodologies, and examine applications in therapeutic development, providing researchers with a technical guide to the state of the art.

Significant experimental and theoretical work has revealed that the coordinated activity of interconnected neural populations contains rich structure, despite its seemingly high-dimensional nature. The emerging challenge is to uncover the computations embedded within this structure and how they drive behavior—a concept termed computation through neural population dynamics [1]. This framework aims to identify general motifs of population activity and quantitatively describe how neural dynamics implement computations necessary for goal-directed behavior.

The neural manifold framework posits that these dynamics are not high-dimensional and chaotic but are constrained to low-dimensional subspaces. These subspaces, or manifolds, reflect the underlying computational principles of the circuit. The activity of large neural populations from an increasing number of brain regions, behaviors, and species shows this low-dimensional structure, which arises from both intrinsic (e.g., connectivity) and extrinsic (e.g., behavior) constraints to the neural circuit [11].

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Foundations

What is a Neural Manifold?

A neural manifold is a mathematical description of the possible collective states of a population of neurons given the constraints of the neural circuit. Formally, it is a low-dimensional subspace embedded within the high-dimensional state space of all possible activity patterns of the population [11].

- Dimensionality Reduction: The process of identifying a manifold involves dimensionality reduction techniques to find a small set of latent variables that capture the majority of the variance in the population activity. These latent variables often correspond to meaningful computational or behavioral variables.

- Dynamic Trajectories: Within the manifold, neural activity evolves over time as a trajectory. These trajectories can represent cognitive processes, motor plans, or sensory representations. The geometry of the manifold and the flow of the trajectories within it are fundamental to the computation being performed [1].

The CHARM Framework

The Complex Harmonics (CHARM) framework is a specific mathematical approach that performs the necessary dimensional manifold reduction to extract nonlocality in critical spacetime brain dynamics. It leverages the mathematical structure of Schrödinger's wave equation to capture the nonlocal, distributed computation made possible by criticality and amplified by the brain's long-range connections [12]. Using a large neuroimaging dataset of over 1000 people, CHARM has captured the critical, nonlocal, and long-range nature of brain dynamics, revealing significantly different critical dynamics between wakefulness and sleep states [12].

Table 1: Key Concepts in Neural Manifold Theory

| Concept | Mathematical Description | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| State Space | High-dimensional space where each axis represents the firing rate of one neuron | The complete set of possible activity states for the neural population |

| Manifold | A low-dimensional geometric surface (e.g., a line, plane, or curved surface) within the state space | The constrained set of activity patterns the circuit can produce due to its connectivity and function |

| Latent Variable | A variable that is not directly measured but is inferred from the population activity | A computational variable (e.g., reach direction, decision confidence, timing) that the population collectively represents |

| Dynamic Trajectory | A path through the state space over time | The evolution of a neural computation, such as from sensory evidence accumulation to a motor command |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

The study of neural manifolds requires a pipeline from data acquisition to mathematical analysis.

Data Acquisition Protocols

1. Multi-electrode Array Recordings:

- Objective: To record the simultaneous activity of hundreds to thousands of neurons across one or multiple brain regions in a behaving animal.

- Protocol: Implant high-density electrode arrays (e.g., Neuropixels probes [11]) into target brain regions (e.g., motor cortex, prefrontal cortex). Train an animal (e.g., non-human primate, rodent) on a behavioral task (e.g., reaching, decision-making). Record extracellular spike waveforms and local field potentials while the animal performs the task. Synchronize neural data with high-resolution behavioral tracking (e.g., video, kinematics).

- Key Consideration: The number of simultaneously recorded neurons directly impacts the ability to resolve the true dimensionality of the underlying manifold.

2. Whole-Brain Functional Imaging:

- Objective: To capture brain-wide neural activity at cellular resolution.

- Protocol: Utilize light-sheet microscopy in transparent or rendered transparent model organisms (e.g., zebrafish larvae). Genetically encode calcium indicators (e.g., GCaMP). Mount the animal in agarose and image the entire brain at a high temporal resolution during spontaneous or evoked behaviors [11].

- Key Consideration: This provides a comprehensive view but often at a lower temporal resolution than electrophysiology.

Core Analytical Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard pipeline for identifying and analyzing neural manifolds from population recording data.

1. Dimensionality Reduction:

- Purpose: To extract the low-dimensional latent variables from the high-dimensional neural data.

- Common Techniques: Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Factor Analysis (FA), Gaussian Process Factor Analysis (GPFA), and non-linear methods like autoencoders or t-SNE [1]. The CHARM framework uses complex harmonics derived from wave equations [12].

- Output: A set of latent factors and the corresponding "neural manifold" that describes the dominant patterns of co-variation across the population.

2. Dynamical Systems Analysis:

- Purpose: To model how the state of the population evolves within the manifold over time.

- Protocol: Fit linear or non-linear dynamical systems models to the low-dimensional trajectories. Identify fixed points (stable states), limit cycles (rhythmic patterns), and other dynamical features that characterize the computation [1]. For example, in motor cortex, reaching movements are generated by neural trajectories flowing through a "manifold attractor" [11].

Quantitative Data in Manifold Research

The field relies on quantitative metrics to validate and characterize neural manifolds. The table below summarizes key metrics reported in recent studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Metrics from Key Manifold and BBB Permeability Studies

| Study / Model | Dataset / Compounds | Key Performance Metrics | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARM Framework [12] | >1000 human neuroimaging datasets | N/A (Theoretical framework validation) | Captured nonlocal, long-range dynamics; differentiated wakefulness vs. sleep critical dynamics |

| Liu et al. (Regression) [13] | 1,757 compounds | 5-fold CV Acc: 0.820–0.918 | Machine learning model predicting blood-brain barrier permeability with high accuracy |

| Shaker et al. (LightBBB) [13] | 7,162 compounds | Accuracy: 89%, Sensitivity: 0.93, Specificity: 0.77 | High sensitivity indicates good identification of BBB-penetrating compounds |

| Boulamaane et al. [13] | 7,807 molecules | AUC: 0.97, External Accuracy: 95% | Ensemble model achieving high predictive power for BBB permeability |

| Kumar et al. [13] | Training: 1,012 compounds | R²: 0.634, Q²: 0.627, R²pred: 0.697 | Quantitative RASAR model showing robust predictive performance on external validation |

Applications in Drug Development and Neurology

Understanding neural manifolds and the associated brain dynamics has profound implications for developing treatments for neurological diseases.

The Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) Challenge

The BBB is a highly selective endothelial structure that restricts the passage of about 98% of small-molecule drugs from the bloodstream into the central nervous system, presenting a major obstacle in drug development for brain diseases [13]. Predicting BBB permeability (BBBp) is therefore a critical first step.

Machine Learning for BBB Permeability Prediction

Machine learning (ML) models are increasingly used to predict BBBp, potentially reducing reliance on expensive animal models. These models are trained on large datasets of known compounds and their measured BBB penetration (often expressed as logBB) [13].

- Input Features: Molecular descriptors (e.g., logP, molecular weight) or simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) strings.

- Common Algorithms: Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Deep Neural Networks (DNN) [13].

- Output: A classification (BBB+ or BBB-) or a regression value (predicted logBB) indicating the likelihood of a compound crossing the BBB.

A Multiscale Computational Framework for Drug Delivery

Beyond predicting permeability, computational frameworks are being developed to model the entire drug delivery process. The diagram below outlines a multiscale framework for mechanically controlled brain drug delivery, such as Convection-Enhanced Delivery (CED).

This integrated approach aims to predict and optimize outcomes for techniques like CED, which have been plagued by issues like uneven drug distribution and backflow [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit

The following table details key reagents, tools, and computational resources essential for research in neural manifolds and related therapeutic development.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Item / Resource | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Neuropixels Probes | Hardware | High-density silicon probes for recording hundreds to thousands of neurons simultaneously [11]. |

| GCaMP Calcium Indicators | Genetic reagent | Genetically encoded fluorescent sensors for imaging neuronal activity using microscopy (e.g., light-sheet) [11]. |

| chroma.js | Software Library | A JavaScript library for color conversions and scale generation, useful for creating accessible, high-contrast data visualizations [15]. |

| font-color-contrast | Software Module | A JavaScript module to select black or white font based on background brightness, ensuring visualization accessibility [16]. |

| Random Forest / XGBoost | Algorithm | Machine learning classifiers used for predicting Blood-Brain Barrier permeability from molecular features [13]. |

| Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Models | Computational Framework | In silico models that relate a molecule's chemical structure to its biological activity, including BBB permeability [13]. |

Discussion and Future Directions

The neural manifold framework has fundamentally shifted how neuroscientists view brain computation, from a focus on single neurons to the dynamics of populations. It provides a powerful language to describe how cognitive and motor functions emerge from neural circuit activity. The application of this framework, combined with advanced in silico models for BBB permeability, holds great promise for accelerating the development of therapeutics for neurological disorders.

Future work will focus on bridging conceptual gaps, such as understanding how manifolds in different brain regions interact in a "network of networks" [11] and how the manifold structure changes in disease states [14] [13]. As recording technologies continue to provide ever-larger datasets, the neural manifold framework will remain an essential tool for building an integrative view of brain function.

The brain's cognitive and computational functions are increasingly understood through the lens of neural population dynamics—the time-evolving patterns of activity across ensembles of neurons. The state space approach provides a powerful mathematical framework for reducing the high dimensionality of neural data and representing these patterns as trajectories within a lower-dimensional space. These neural trajectories offer a window into the underlying computational principles of brain function, revealing how networks of neurons collectively encode information, make decisions, and generate behavior. Research demonstrates that the manner in which neural activity unfolds over time is central to sensory, motor, and cognitive functions, and that these activity time courses are shaped by the underlying network architecture [17]. The state space approach enables researchers to move beyond analyzing single neurons in isolation to understanding the collective dynamics of neural populations that form the true substrate of brain computation.

Visualizing these dynamics through trajectories and flow fields has become increasingly important in both basic neuroscience and drug development. For pharmaceutical researchers, understanding how neural population dynamics are altered in disease states—and how candidate compounds might restore normal dynamics—provides a powerful framework for evaluating therapeutic efficacy beyond single biomarkers. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of the conceptual foundations, analytical methods, and practical applications of state space analysis for understanding neural computation.

Mathematical Foundations of State Space Analysis

Core Theoretical Framework

At its core, the state space approach treats the activity of a neural population at any moment as a single point in an abstract space where each dimension represents the activity level of one neuron or, more commonly, a latent variable derived from the population. Over time, this point moves through the space, tracing a neural trajectory that reflects the computational process unfolding in the network. The flow field represents the forces or dynamics that govern the direction and speed of these trajectories at each point in the state space.

A powerful implementation of this framework involves Piecewise-Linear Recurrent Neural Networks (PLRNNs) within state space models. These models approximate nonlinear neural dynamics through a system that is linear in regions separated by thresholds, making them both computationally tractable and dynamically expressive. The fundamental PLRNN equation describes the evolution of the latent neural state vector z at time t [18]:

zₜ = A zₜ₋₁ + W max(zₜ₋₁ - θ, 0) + C sₜ + εₜ

Where:

- A is a diagonal matrix of auto-regression weights (representing intrinsic neuronal properties)

- W is the off-diagonal matrix of connection weights between units

- θ represents activation thresholds

- max(·,0) is the piecewise-linear activation function

- sₜ represents external inputs weighted by matrix C

- εₜ is Gaussian process noise

This formulation balances biological plausibility with mathematical tractability, allowing researchers to infer the latent dynamics from noisy, partially observed neural data.

Fixed Point Analysis and Dynamical Regimes

A particular advantage of the PLRNN framework is that all fixed points can be obtained analytically by solving a system of linear equations, enabling comprehensive characterization of the dynamical landscape [18]. The fixed points satisfy:

z* = (I - A - WΩ)⁻¹ (WΩ θ + h)

Where Ω denotes the set of units below threshold, and WΩ is the connectivity matrix with columns corresponding to units in Ω set to zero. This analytical accessibility enables researchers to identify attractor states believed to underlie cognitive processes like working memory, and to understand how neural circuits transition between different computational states.

Table 1: Key Mathematical Formulations for State Space Analysis

| Concept | Mathematical Representation | Computational Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| State Space | (\mathbb{R}^M) where M is dimensionality | Working space of neural population activity |

| Neural Trajectory | ({\mathbf{z}1, \mathbf{z}2, ..., \mathbf{z}_T}) | Temporal evolution of population activity during computation |

| Flow Field | (F(\mathbf{z}) = \frac{d\mathbf{z}}{dt}) | Governing dynamics at each point in state space |

| Fixed Points | (\mathbf{z}^) where (F(\mathbf{z}^) = 0) | Stable states (e.g., memory representations) |

| Linearized Dynamics | (\mathbf{J} = \frac{\partial F}{\partial \mathbf{z}}|_{\mathbf{z}^*}) | Local stability properties near fixed points |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Neural Data Acquisition for State Space Analysis

State space analysis begins with acquiring multivariate neural time series data through various recording modalities. The choice of acquisition method depends on the spatial and temporal scales of interest, balancing resolution with population coverage. For studying circuit-level computations, multiple single-unit recordings using tetrodes or silicon probes provide the temporal precision needed to resolve individual spikes while monitoring dozens to hundreds of neurons simultaneously. Alternatively, calcium imaging techniques offer cellular resolution with genetic specificity, though with slower temporal dynamics. Each modality presents distinct challenges for subsequent state space reconstruction, requiring specialized preprocessing and statistical treatments.

A critical experimental paradigm for studying neural computation involves brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) that allow researchers to challenge animals to manipulate their own neural activity patterns. In one groundbreaking experiment, monkeys were challenged to violate the naturally occurring time courses of neural population activity in motor cortex, including traversing natural activity patterns in time-reversed manners [17]. This approach revealed that animals were unable to violate these natural neural trajectories when directly challenged to do so, providing empirical support that observed activity time courses reflect fundamental computational constraints of the underlying networks.

State Space Model Estimation Protocol

The following protocol outlines the steps for estimating state space models from neural data using the PLRNN framework:

Step 1: Data Preprocessing and Dimensionality Reduction

- Begin with spike sorting and binning of neural recordings (e.g., 10-50ms bins)

- Apply initial dimensionality reduction using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify dominant activity patterns

- Optionally smooth data using kernel techniques to reduce noise while preserving dynamics

Step 2: Model Initialization

- Initialize PLRNN parameters (A, W, θ) using empirical estimates

- Set dimensionalities: M latent states, matched to the complexity of the observed data

- Define observation model linking latent states to measured neural activity

Step 3: Expectation-Maximization (EM) Algorithm

- E-step: Infer latent state distribution given current parameters and observations

- Use a global Laplace approximation or particle filters to approximate state posteriors

- M-step: Update model parameters to maximize expected complete-data log-likelihood

- Iterate until convergence of model evidence or parameter stability

Step 4: Model Validation

- Assess model fit through reconstruction of observed neural activity

- Validate predictive performance on held-out data

- Check dynamical consistency through fixed point analysis and stability characterization

This semi-analytical maximum-likelihood estimation framework provides a statistically principled approach for recovering nonlinear dynamics from noisy neural recordings [18].

Visualization Techniques for Neural Trajectories

Dimensionality Reduction Methods

Visualizing high-dimensional neural dynamics requires projecting state spaces into lower dimensions that preserve essential computational features. Several dimensionality reduction techniques have been adapted specifically for neural data:

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) remains a widely used linear technique that projects data onto orthogonal axes of maximal variance. While PCA effectively captures global population structure, it may miss nonlinear features critical for understanding neural computation.

t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) is a nonlinear technique that preserves local structure by minimizing the divergence between probability distributions in high and low dimensions [19]. t-SNE excels at revealing cluster structure in neural data but may distort global relationships.

PHATE (Potential of Heat-diffusion for Affinity-based Transition Embedding) is a newer method specifically designed for visualizing temporal progression in biological data, making it particularly suitable for analyzing neural trajectories across different behavioral conditions.

The choice of visualization technique should align with the scientific question—whether focusing on discrete attractor states (where cluster preservation matters) or continuous dynamics (where trajectory smoothness is prioritized).

Flow Field Reconstruction

Beyond visualizing individual trajectories, reconstructing the entire flow field provides a complete picture of the dynamical landscape underlying neural computation. Flow fields represent the direction and magnitude of state change at each point in the state space, effectively showing the "forces" governing neural dynamics.

Local linear approximation methods estimate the Jacobian matrix at regular points in the state space, then interpolate to create a continuous vector field. Gaussian process regression provides a probabilistic alternative that naturally handles uncertainty in the estimated dynamics. These flow field visualizations reveal key computational features including:

- Fixed points (attractor states) where flow converges

- Repellors where flow diverges

- Limit cycles representing rhythmic activity patterns

- Saddles marking transitions between different computational states

In working memory tasks, for example, flow fields typically show distinct fixed points corresponding to different memory representations, with the system's state being drawn toward the appropriate attractor based on task conditions.

Experimental Applications and Case Studies

Delayed Alternation Working Memory Task

The application of state space analysis to multiple single-unit recordings from the rodent anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) during a delayed alternation working memory task provides a compelling case study [18]. In this task, animals must maintain information across a delay period to correctly alternate between goal locations. State space models estimated from kernel-smoothed spike data successfully captured the essential computational dynamics underlying task performance, including stimulus-selective delay activity that persisted during the memory period.

Interestingly, the estimated models were rarely multi-stable but rather were tuned to exhibit slow dynamics in the vicinity of a bifurcation point. This suggests that neural circuits may implement working memory through mechanisms more subtle than classic attractor models with multiple discrete stable states. Instead, the dynamics appear to be delicately balanced to maintain information without committing to fully separate attractors, potentially providing greater flexibility in real-world cognitive operations.

Motor Cortex Dynamics During Reaching

Studies of neural population dynamics in motor cortex during reaching movements have revealed remarkably consistent rotational dynamics in neural state space [17]. These rotational trajectories appear to form a fundamental computational primitive for generating motor outputs, with different phases of rotation corresponding to different movement directions and speeds.

When researchers challenged monkeys to produce time-reversed versions of their natural neural trajectories using a BCI paradigm, animals were unable to violate these natural dynamical patterns [17]. This provides strong evidence that the observed neural trajectories reflect fundamental computational constraints of the underlying network architecture, rather than merely epiphenomenal correlates of behavior.

Table 2: Key Experimental Findings from Neural Trajectory Studies

| Brain Area | Behavioral Task | Key Dynamical Feature | Computational Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prefrontal Cortex | Working memory | Slow dynamics near bifurcation points | Flexible maintenance without rigid attractors |

| Motor Cortex | Reaching movements | Consistent rotational trajectories | Dynamical primitive for movement generation |

| Anterior Cingulate Cortex | Delayed alternation | Stimulus-selective delay activity | Temporal persistence of task-relevant information |

| Hippocampus | Spatial navigation | Sequence replay during sharp-wave ripples | Memory consolidation and planning |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Neural Trajectory Analysis

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Neural Recording Systems | Neuropixels probes, tetrode arrays, 2-photon microscopes | High-dimensional neural activity acquisition with cellular resolution |

| Data Analysis Platforms | MATLAB, Python with NumPy/SciPy, Julia | Implementation of state space estimation algorithms and visualization |

| Statistical Toolboxes | PLRNN State Space Toolbox, GPFA, LFADS | Specialized algorithms for neural trajectory extraction and modeling |

| Visualization Software | Matplotlib, Plotly, BrainNet, D3.js | Creation of static and interactive neural trajectory visualizations |

| Dimensionality Reduction Tools | PCA, t-SNE, UMAP, PHATE | Projection of high-dimensional neural data into visualizable spaces |

| Computational Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch | Development and training of custom neural network models for dynamics |

Visualization Schematics for State Space Analysis

Neural State Space Estimation Workflow

Neural Trajectories in Working Memory

Future Directions and Clinical Applications

Emerging Computational Approaches

The field of neural population dynamics is rapidly evolving with several promising research directions. Machine learning and deep learning techniques are being integrated with state space modeling to handle increasingly large-scale neural recordings and capture more complex dynamical features [19]. Virtual and augmented reality platforms offer new opportunities for creating immersive experimental environments where neural dynamics can be studied in more naturalistic contexts. From a theoretical perspective, researchers are developing more sophisticated approaches for relating neural trajectories to specific computational operations, moving beyond descriptive accounts to mechanistic explanations of how dynamics implement cognition.

Applications in Drug Development and Neurological Disorders

For pharmaceutical researchers, neural trajectory analysis provides a powerful framework for understanding how neurological and psychiatric disorders alter brain dynamics and how therapeutic interventions might restore normal function. In conditions like Parkinson's disease, state space analysis has revealed characteristic alterations in basal ganglia dynamics that correlate with motor symptoms. Similarly, in psychiatric conditions like schizophrenia and depression, researchers have identified specific disruptions in prefrontal and limbic dynamics during cognitive and emotional processing.

The state space approach offers particularly promising biomarkers for drug development because it captures system-level dynamics that may be disrupted even when individual neuronal properties appear normal. By quantifying how candidate compounds affect neural trajectories in disease models, researchers can obtain more sensitive and mechanistically informative measures of therapeutic potential than traditional behavioral assays alone. Furthermore, understanding how drugs reshape the dynamical landscape of neural circuits—for instance, by stabilizing specific attractor states or increasing the robustness of trajectories—provides a principled framework for optimizing therapeutic interventions.

The brain does not function as a mere collection of independent neurons; rather, it operates through the coordinated activity of neural populations whose patterns evolve over time. This temporal evolution, known as neural population dynamics, provides a fundamental framework for understanding how sensory inputs are transformed into motor outputs and decisions. Significant experimental, computational, and theoretical work has identified rich structure within this coordinated activity, revealing that the brain's computations are implemented through these dynamics [1]. This framework posits that the time evolution of neural activity is not arbitrary but is shaped by the underlying network connectivity, effectively forming a "flow field" that constrains and guides neural trajectories. This perspective unifies concepts from various brain functions—including sensory processing, decision-making, and motor control—into a cohesive principle of brain-wide computation. The following sections explore the empirical evidence supporting this framework, the experimental methodologies enabling its discovery, and its implications for understanding brain function.

Core Principles of Neural Population Dynamics

Defining Dynamics and Neural Trajectories

At its core, the dynamical systems view describes the brain's internal state at any moment as a point in a high-dimensional space, where each dimension corresponds to the firing rate of one neuron. The evolution of this state over time forms a neural trajectory—a time course of population activity patterns in a characteristic sequence [20]. These trajectories are believed to be central to sensory, motor, and cognitive functions. In network models, the time evolution of activity is shaped by the network's connectivity, where the activity of each node at a given time is determined by the activity of every node at the previous time point, the network's connectivity, and its inputs [20]. Such dynamics give rise to the computation being performed by the network.

Motor Control as a Dynamical Process

Motor control can be reframed as a problem of decision-making under uncertainty, where the goal is to maximize the utility of movement outcomes [21]. This statistical decision theory perspective suggests that the choice of a movement plan and control strategy involves Bayesian inference and optimization, processes naturally implemented through neural dynamics. The motor system appears to generate movements by steering neural activity along specific trajectories within this state space, with the underlying network constraints ensuring that these trajectories are robust and reproducible.

Decision-Making Through Dynamics

Perceptual decisions rely on learned associations between sensory evidence and appropriate actions, involving the filtering and integration of relevant inputs to prepare and execute timely responses [22]. Brain-wide recordings in mice performing decision-making tasks have revealed that evidence integration emerges across most brain areas in sparse neural populations that drive movement-preparatory activity. Visual responses evolve from transient activations in sensory areas to sustained representations in frontal-motor cortex, thalamus, basal ganglia, midbrain, and cerebellum, enabling parallel evidence accumulation [22]. In areas that accumulate evidence, shared population activity patterns encode visual evidence and movement preparation, distinct from movement-execution dynamics.

The Constrained Nature of Neural Trajectories

A key prediction from the dynamical systems framework is that neural trajectories should be difficult to violate because they reflect the underlying network-level computational mechanisms. Recent experiments using brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) have directly tested this hypothesis by challenging monkeys to volitionally alter the time evolution of their neural population activity, including traversing natural activity time courses in a time-reversed manner [20]. Animals were unable to violate these natural time courses, providing empirical support that activity time courses observed in the brain reflect fundamental network constraints.

Key Experimental Evidence and Methodologies

Testing Dynamical Constraints with Brain-Computer Interfaces

To directly test the robustness of neural activity time courses, researchers have employed BCI paradigms that provide users with moment-by-moment visual feedback of their neural activity [20]. This approach harnesses a user's volition to attempt to alter the neural activity they produce, thereby causally probing the limits of neural function. In one seminal study, researchers recorded the activity of approximately 90 neural units from the motor cortex of rhesus monkeys implanted with multi-electrode arrays. The recorded neural activity was transformed into ten-dimensional latent states using a causal form of Gaussian process factor analysis (GPFA). Animals then controlled a computer cursor via a BCI mapping that projected these latent states to the two-dimensional position of the cursor [20].

Table 1: Key Experimental Parameters from BCI Constraint Study

| Parameter | Specification |

|---|---|

| Subjects | Rhesus monkeys |

| Neural Recording | ~90 units from motor cortex |

| Array Type | Multi-electrode array |

| Dimensionality Reduction | Causal Gaussian Process Factor Analysis (GPFA) |

| Latent State Dimensions | 10-dimensional |

| BCI Mapping | 10D to 2D cursor position |

| Task Paradigm | Two-target center-out task |

A critical design element was the use of different 2D projections of the 10D neural space. The initial "movement-intention" (MoveInt) projection allowed animals to move the cursor flexibly throughout the workspace. However, when researchers identified a "separation-maximizing" (SepMax) projection that revealed direction-dependent curvature of neural trajectories, they found that animals could not alter these fundamental dynamics even when strongly incentivized to do so [20].

Brain-Wide Dynamics in Decision-Making

Complementing the focal motor cortex studies, recent research has investigated brain-wide neural activity in mice learning to report changes in ambiguous visual input [22]. After learning, evidence integration emerged across most brain areas in sparse neural populations that drive movement-preparatory activity. The research demonstrated that visual responses evolve from transient activations in sensory areas to sustained representations in frontal-motor cortex, thalamus, basal ganglia, midbrain, and cerebellum, enabling parallel evidence accumulation.

Table 2: Brain-Wide Evidence Accumulation Findings

| Brain Area | Role in Evidence Integration |

|---|---|

| Sensory Areas | Transient visual responses |

| Frontal-Motor Cortex | Sustained evidence representations |

| Thalamus | Evidence accumulation |

| Basal Ganglia | Evidence accumulation |

| Midbrain | Evidence accumulation |

| Cerebellum | Evidence accumulation |

In areas that accumulate evidence, shared population activity patterns encode visual evidence and movement preparation, distinct from movement-execution dynamics. Activity in the movement-preparatory subspace is driven by neurons integrating evidence, which collapses at movement onset, allowing the integration process to reset [22].

Experimental Workflow for Probing Neural Dynamics

The following Graphviz diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow used to test constraints on neural dynamics:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Neural Dynamics Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-electrode Arrays | High-density neural recording | Simultaneously recording ~90 motor cortex units [20] |

| Causal GPFA | Dimensionality reduction | Extracting 10D latent states from neural population data [20] |

| Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) | Neural activity manipulation | Challenging animals to alter neural trajectories [20] |

| Brain-Wide Calcium Imaging | Large-scale neural activity recording | Monitoring evidence integration across brain areas [22] |

| Optogenetics | Targeted neural manipulation | Testing causal role of specific populations [1] |

Conceptual Diagram of Neural Trajectory Constraints

The following Graphviz diagram illustrates the core concept of constrained neural trajectories and the experimental paradigm:

Discussion and Implications

Theoretical Implications for Brain Function

The convergence of evidence from motor control and decision-making studies suggests a unified principle of brain function: computation through neural population dynamics. This framework helps explain how distributed neural networks can systematically transform sensory inputs into motor outputs. The constrained nature of neural trajectories indicates that these dynamics are not merely epiphenomenal but reflect fundamental computational mechanisms embedded in the network architecture of neural circuits. Furthermore, the discovery that learning aligns evidence accumulation to action preparation across dozens of brain regions [22] provides a mechanism for how experience shapes neural dynamics to support adaptive behavior.

Methodological Advances and Future Directions

The application of dynamical systems theory to neuroscience has driven significant methodological innovations, including new approaches to neural data analysis and experimental design. BCI paradigms that manipulate the relationship between neural activity and behavior have proven particularly powerful for causal testing of neural dynamics [20]. Future research will likely focus on understanding how these dynamics emerge during learning, how they are modulated by behavioral state and context, and how they are disrupted in neurological and psychiatric disorders. The development of increasingly sophisticated brain-wide recording technologies will enable more comprehensive characterization of neural dynamics across brain regions and their coordination during complex behaviors.

The framework of computation through neural population dynamics represents a paradigm shift in neuroscience, providing a principled approach to understanding how the brain links sensation to action. The experimental evidence from both motor control and decision-making studies consistently demonstrates that neural activity evolves along constrained trajectories that reflect the underlying network architecture and support specific computations. This dynamical perspective continues to yield fundamental insights into brain function and offers promising avenues for future research in both basic and clinical neuroscience.

Linking Single-Neuron Rate Coding to Population-Level Dynamics

This technical guide examines the mechanistic links between the firing rates of individual neurons and the emergent dynamics of neural populations, a foundational relationship for understanding brain function. Framed within a broader thesis on neural population dynamics, we synthesize recent experimental and computational advances to demonstrate that population-level computations are both constrained by and built upon the heterogeneous properties of single neurons. We provide a quantitative framework and practical methodologies for researchers aiming to bridge these scales of neural organization, with direct implications for interpreting neural circuit function and dysfunction in disease states.

In the brain, information about behaviorally relevant variables—from sensory stimuli to motor commands and cognitive states—is encoded not by isolated neurons but by the coordinated activity of neural populations [3]. The fundamental challenge in systems neuroscience lies in understanding how the diverse response properties of individual neurons give rise to robust, population-level representations and computations. Single-neuron rate coding, where information is carried by a cell's firing frequency, provides a critical input to these population dynamics. However, as we will explore, the population code is more than a simple sum of its parts; it is shaped by the heterogeneity of single-neuron tuning, the relative timing of spikes, and the network state, which collectively determine the coding capacity of a neural population [3].

Theoretical and experimental work increasingly supports the view that neural computations are implemented by the temporal dynamics of population activity [17] [23]. Recent studies using brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) have provided empirical evidence that these naturally occurring time courses of population activity reflect fundamental computational mechanisms of the underlying network, to the extent that they cannot be easily violated or altered through learning [17] [23]. This suggests that the dynamics of neural populations form a fundamental constraint on brain function, linking the microscopic properties of single neurons to macroscopic behavioral outputs.

Theoretical Framework: Geometry and Dynamics of Population Coding

A Common Principle for Sensory and Cognitive Variables

The brain represents both sensory variables and dynamic cognitive variables using a common principle: encoded variables determine the topology of neural representation, while heterogeneous tuning curves of single neurons define the representation geometry [24]. In primary visual cortex, for example, the orientation of a visual stimulus—a one-dimensional circular variable—is encoded by population responses organized on a ring structure that mirrors the topology of the encoded variable. The orientation-tuning curves of individual neurons jointly define the embedding of this ring in the population state space [24].

Emerging evidence indicates that this same coding principle applies to dynamic cognitive processes such as decision-making. In the primate dorsal premotor cortex (PMd), populations of neurons encode the same dynamic "decision variable" predicting choices, despite individual neurons exhibiting diverse temporal response profiles [24]. Heterogeneous firing rates arise from the diverse tuning of single neurons to this common decision variable, revealing a unified geometric principle for neural encoding across sensory and cognitive domains.

The Role of Single-Neuron Heterogeneity

The computational properties of population codes are fundamentally shaped by the diverse selectivity of individual neurons. This heterogeneity manifests in several key dimensions:

- Diverse stimulus tuning: Neighboring neurons may have different stimulus preferences or tuning widths, enabling them to carry complementary information [3].

- Temporal diversity: Neurons exhibit varied temporal response profiles during cognitive tasks, which may seem incompatible with population-level encoding of a unified cognitive variable, but can be reconciled through appropriate population models [24].

- Mixed selectivity: In higher association areas, neurons often show complex, nonlinear selectivity to multiple task variables, creating high-dimensional population representations that facilitate linear decoding by downstream areas [3].

Contrary to the intuition that information increases steadily with population size, recent work reveals that only a small fraction of neurons in a given population typically carry significant sensory information in a specific context [3]. A small but highly informative subset of neurons can often carry essentially all the information present in the entire observed population, suggesting a sparse structure in neural population codes.

Quantitative Approaches and Experimental Findings

Inferring Population Dynamics from Single-Neuron Activity

Cutting-edge computational approaches now enable researchers to simultaneously infer population dynamics and tuning functions of single neurons from spike data. One such method models neural activity as arising from a latent decision variable ( x(t) ) governed by a nonlinear dynamical system:

[ \dot{x} = -D\frac{d\Phi(x)}{dx} + \sqrt{2D}\xi(t) ]

where ( \Phi(x) ) is a potential function defining deterministic forces, and ( \xi(t) ) is Gaussian white noise with magnitude ( D ) that accounts for stochasticity of latent trajectories [24]. In this framework, spikes of each neuron are modeled as an inhomogeneous Poisson process with instantaneous firing rate ( \lambda(t) = fi(x(t)) ), where the tuning functions ( fi(x) ) define each neuron's unique dependence on the latent variable.

When applied to primate PMd during decision-making, this approach revealed that despite heterogeneous trial-averaged responses, single neurons showed remarkably consistent dynamics during choice formation on single trials [24]. The inferred potentials consistently displayed a nearly linear slope toward the decision boundary corresponding to the correct choice, with a single potential barrier separating it from the incorrect choice, suggesting an attractor mechanism for decision computation.

Quantitative Characterization of Single-Neuron Contributions

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings from Decision-Making Studies in Primate PMd

| Parameter | Monkey T | Monkey O | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurons with reliable model fit | 117/128 (91%) | 67/88 (76%) | Majority of neurons conform to population coding model |

| Spike-time variance explained | 0.27 ± 0.14 | 0.22 ± 0.13 | Model captures significant portion of neural response |

| Residual vs. point-process variance correlation | r = 0.80 | r = 0.73 | Model accounts for nearly all explainable variance |

| Neurons with single-barrier potential | 102/117 (87%) | 66/67 (98.5%) | Consistent attractor dynamics across population |

Dynamical Constraints on Neural Population Activity

Recent BCI studies have revealed fundamental constraints on neural population dynamics. When monkeys were challenged to violate the naturally occurring time courses of neural population activity in motor cortex—including traversing natural activity trajectories in a time-reversed manner—they were unable to do so despite extensive training [17]. These findings provide empirical support for the view that activity time courses reflect underlying network-level computational mechanisms that cannot be easily altered, suggesting that neural activity dynamics both reflect and constrain how the brain performs computations [23].

This constrained nature of population dynamics has important implications for understanding brain function and learning. Rather than being infinitely flexible, neural populations appear to operate within a structured dynamical space, where learning may involve finding new trajectories within existing constraints rather than creating entirely new dynamics [23].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Inferring Latent Dynamics from Spike Data

This protocol enables researchers to discover neural representations of dynamic cognitive variables directly from spike data [24].

Workflow Overview

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Neural Recording: Record spiking activity using linear multielectrode arrays from relevant cortical areas (e.g., primate dorsal premotor cortex) during a decision-making task.

- Task Design: Employ a reaction-time task where animals discriminate between stimuli (e.g., checkerboard with varying color proportions) and report decisions by touching targets. Vary stimulus difficulty across trials.

- Spike Sorting: Isolate single-neuron spike trains from recorded signals.

- Model Specification:

- Define a latent variable ( x(t) ) governed by the equation: ( \dot{x} = -D\frac{d\Phi(x)}{dx} + \sqrt{2D}\xi(t) )

- Model spikes of each neuron ( i ) as an inhomogeneous Poisson process with rate ( \lambda(t) = fi(x(t)) )

- Initialize ( x(t) ) from distribution ( p0(x) ) at trial start

- Terminate trial when ( x(t) ) reaches decision boundary

- Model Fitting: Simultaneously infer functions ( \Phi(x) ), ( p0(x) ), ( fi(x) ) and noise magnitude ( D ) by maximizing model likelihood. Use shared optimization across stimulus conditions with only ( \Phi(x) ) varying between conditions.

- Model Validation:

- Calculate proportion of spike-time variance explained by model

- Compare with baseline prediction from trial-average firing rates

- Correlate residual unexplained variance with estimated point-process variance

- Analysis:

- Examine shape of inferred potential ( \Phi(x) ) for features like slopes and barriers

- Analyze distribution of initial states ( p0(x) )

- Characterize heterogeneity in tuning functions ( fi(x) ) across neurons

Protocol 2: Combining HD-MEA and Optogenetics for Network Analysis

This protocol enables investigation of interactions between single-neuron activity and network-wide dynamics [25].

Workflow Overview

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Cell Preparation: Culture rat cortical neurons on high-density microelectrode arrays (HD-MEAs) containing 26,400 electrodes with 17.5-μm pitch.

- Optogenetic Transduction: Introduce channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) tagged with GFP using adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors. Allow expression for >30 days in vitro to ensure mature neuronal networks.

- Experimental Setup: Integrate electrical recording via HD-MEA with optogenetic stimulation using a digital mirror device (DMD) mounted on an upright microscope. Shield setup from external light and maintain at 37°C with CO₂ supply.

- Stimulation Targeting:

- Capture fluorescence images of GFP to identify ChR2-expressing neurons

- Overlay stimulation area divided into grids

- Manually select grids containing ChR2-GFP-expressing neurons

- Deliver optical stimulation sequentially to each selected location

- Stimulation Parameters: Use 50×50 μm² optical stimulation with 5 ms pulses at intensity of 15.4 mW/mm² to reliably induce single spikes in targeted neurons with minimal jitter.

- Artifact Handling: Mitigate stimulation artifacts using bandpass filtering (300-3500 Hz). Narrow stimulation area to minimize artifact amplitude.

- Response Classification:

- Identify direct responses with minimal jitter during stimulation period

- Identify indirect synaptic responses with considerable jitter after stimulus period

- Map spatial distribution of responding neurons

- Network Analysis:

- Examine network burst-dependent changes in single-neuron response properties

- Identify "leader neurons" that initiate network-wide bursting activity

- Characterize firing properties of hub neurons

Protocol 3: Automated High-Throughput Single-Neuron Characterization

This protocol enables rapid, standardized characterization of single-neuron properties using simplified spiking models [26].

Step-by-Step Procedure