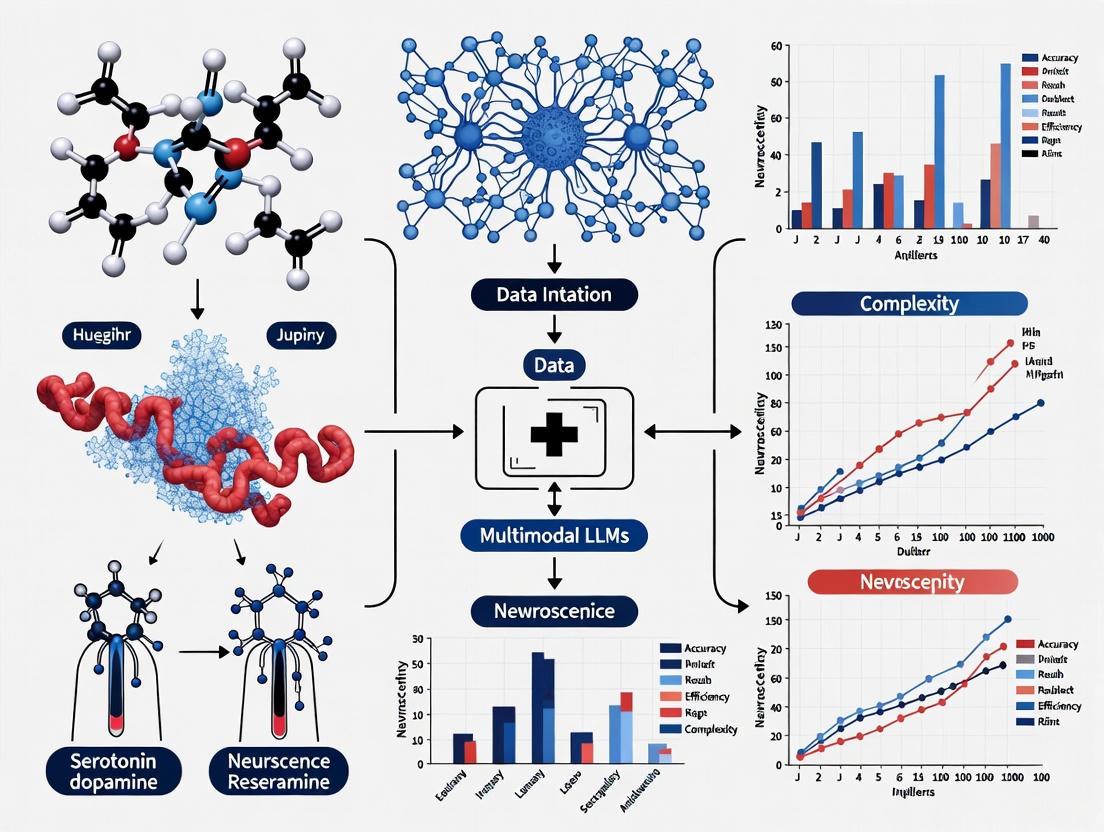

Multimodal LLMs in Neuroscience: A New Paradigm for Brain Research and Clinical Innovation

Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) are poised to revolutionize neuroscience research and clinical practice.

Multimodal LLMs in Neuroscience: A New Paradigm for Brain Research and Clinical Innovation

Abstract

Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) are poised to revolutionize neuroscience research and clinical practice. This article explores the profound impact of MLLMs, from decoding brain activity to predicting experimental outcomes. We examine how MLLMs integrate diverse data modalities—including text, imaging, and brain recordings—to offer unprecedented insights into neural mechanisms. While these models demonstrate remarkable capabilities in synthesizing scientific literature and assisting in diagnosis, significant challenges remain, including issues of grounding, reasoning inflexibility, and hallucination. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review provides a comprehensive analysis of current methodologies, validation benchmarks, and future directions, highlighting both the transformative potential and critical limitations of MLLMs in advancing our understanding of the brain.

Grounding Understanding: How MLLMs Process and Represent Neural Information

The symbol grounding problem represents a foundational challenge in artificial intelligence, cognitive science, and philosophy of mind, concerning how arbitrary symbols manipulated by a computational system acquire real-world meaning rather than remaining mere tokens governed by syntactic rules [1]. First articulated by Stevan Harnad in 1990, this problem arises from the observation that symbols in traditional AI systems are defined solely in terms of each other, leading to definitional circularity or infinite regress [1]. In neuroscience AI, this challenge manifests acutely as researchers attempt to bridge the gap between high-dimensional vector representations in machine learning models and meaningful neuroscientific concepts with real-world referents. The core issue can be summarized as follows: without direct connection to nonsymbolic experience, no symbol within a system can acquire intrinsic meaning, creating what Harnad described as a "grounding kernel" of basic symbols that must acquire meaning through direct connections to the world [1].

The advent of multimodal large language models (LLMs) and foundation models in neuroscience research has brought renewed urgency to the symbol grounding problem. These models demonstrate remarkable capabilities in processing and generating scientific text, predicting experimental outcomes, and even formulating hypotheses [2] [3]. However, the question remains whether these models genuinely understand the neuroscientific concepts they manipulate or merely exhibit sophisticated pattern matching without true semantic comprehension. As LLMs increasingly integrate into drug development pipelines and clinical decision support systems, resolving the symbol grounding problem becomes not merely theoretical but essential for ensuring the reliability, interpretability, and ethical application of AI in neuroscience [4] [5] [6].

Theoretical Foundations of Symbol Grounding

Formal Definitions and Computational Limits

Formally, the symbol grounding problem can be expressed through dictionary networks, where a vocabulary V(D) = {w₁,...,wₙ} contains definitional dependencies for each word def(w) ⊂ V(D) [1]. A subset G ⊆ V(D) is considered "grounded" if its meanings are acquired non-symbolically, with the reachable set R(D,G) comprising all words whose meanings can be reconstructed from G through finite look-up. This formulation reveals the computational complexity of symbol grounding, which reduces to the NP-complete feedback vertex set problem [1]. Algorithmic information theory further demonstrates that most possible data strings are incompressible (random), meaning a static symbolic system can only ground a vanishing fraction of all possible worlds [1].

Recent formal analyses have established rigorous limits on symbol grounding in computational systems. Any closed symbolic system can only ground concepts it was specifically designed for, while the overwhelming majority of possible worlds are algorithmically random and thus ungroundable within such systems [1]. The "grounding act"—the adaptation or information addition required for new grounding—cannot be algorithmically deduced from within the existing system and must import information extrinsically [1]. This has profound implications for neuroscience AI, suggesting that purely symbolic approaches to understanding neural phenomena will inevitably encounter grounding limitations without incorporating non-symbolic components such as intention, affect, and embodiment [1].

From Biological to Artificial Systems

In biological agents, symbol grounding emerges through evolutionary feedback loops where internal variables (such as fitness estimators) become representations by virtue of their functional role in survival and adaptation [1]. Genuine "aboutness" or semantic reference arises when internal variables participate in regulating stochastic adaptation, with higher-level symbols further stabilized through social communication [1]. This biological perspective highlights three requirements often missing in artificial systems: (i) nonlinear self-reproduction or strong selection, (ii) internal models guiding adaptation, and (iii) communication or social convergence to stabilize shared meanings [1].

For artificial agents in neuroscience, this suggests that effective symbol grounding may require not just causal connections between representations and referents, but structured functional coupling to adaptive goals, potentially implemented through reinforcement learning frameworks with carefully designed reward functions [1] [3]. The lack of biological self-reproduction or robust analogs in AI systems represents a key barrier to reproducing genuine semantic grounding in computational neuroscience models [1].

Multimodal AI Approaches to Symbol Grounding in Neuroscience

Multimodal Integration Strategies

Multimodal AI approaches offer promising pathways toward addressing the symbol grounding problem in neuroscience by creating direct connections between symbolic representations and non-symbolic data modalities [4] [3]. These systems learn to associate concepts across different data types—such as text, genomic sequences, neuroimaging, and chemical structures—enabling them to find patterns and relate information across modalities [4]. For example, vision-language models like Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training (CLIP) generate latent representations that capture cross-modal semantic relationships, enabling alignment of neural activity patterns with textual descriptions or visual stimuli [3].

The integration of diverse neuroscience data sources through multimodal language models (MLMs) creates opportunities for more robust symbol grounding [4] [6]. By simultaneously processing genomic data, biological images, clinical records, and scientific literature, MLMs can detect and connect trends across different modalities, potentially developing representations grounded in multiple aspects of neuroscientific reality [4]. This multimodal approach helps overcome limitations of traditional methods that analyze only single information sources, moving toward a more holistic understanding of complex neurological phenomena [4].

Table 1: Multimodal Data Types in Neuroscience AI

| Data Modality | Examples | Grounding Function |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Data | DNA sequences, epigenetic markers, transcriptomics | Grounds molecular-level concepts in biological primitives |

| Neuroimaging | fMRI, EEG, MEG, sEEG, ECoG, CT | Grounds cognitive concepts in brain structure/function |

| Clinical Data | Electronic health records, treatment outcomes, symptoms | Grounds disease concepts in patient manifestations |

| Chemical Structures | Drug molecules, metabolites, neurotransmitters | Grounds pharmacological concepts in molecular features |

| Scientific Literature | Research articles, patents, clinical trial protocols | Grounds theoretical concepts in collective knowledge |

Embodied and Interactive Grounding

Beyond multimodal integration, embodied approaches to AI offer additional grounding mechanisms through sensorimotor interaction with environments [1]. In robotic applications, symbol grounding emerges through mapping between words and physical features via real-time sensorimotor streams, with symbol meaning distilled through online probabilistic models that associate sensory features with symbolic labels [1]. While direct embodiment presents challenges for many neuroscience AI applications, interactive systems that engage with laboratory environments, experimental apparatus, or clinical settings may provide analogous benefits.

Interactive grounding mechanisms enable continuous refinement of symbol meaning through operational feedback [1] [7]. For instance, AI systems that both predict experimental outcomes and receive feedback on those predictions can progressively ground their scientific concepts in empirical reality [2]. This creates a virtuous cycle where symbol manipulation leads to testable predictions, whose verification or falsification subsequently refines the symbols themselves—a process mirroring the scientific method itself [2] [7].

Experimental Evidence and Validation Frameworks

Benchmarking Symbolic Understanding in Neuroscience AI

The development of specialized benchmarks has enabled systematic evaluation of symbol grounding capabilities in neuroscience AI systems. BrainBench, a forward-looking benchmark for predicting neuroscience results, evaluates how well AI systems can predict experimental outcomes from methodological descriptions [2]. In rigorous testing, LLMs surpassed human experts in predicting neuroscience results, with models averaging 81.4% accuracy compared to human experts' 63.4% [2]. This performance advantage persisted across all neuroscience subfields: behavioral/cognitive, cellular/molecular, systems/circuits, neurobiology of disease, and development/plasticity/repair [2].

Table 2: BrainBench Performance Across Neuroscience Subfields

| Neuroscience Subfield | LLM Accuracy (%) | Human Expert Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral/Cognitive | 82.1 | 64.3 |

| Cellular/Molecular | 80.7 | 62.9 |

| Systems/Circuits | 81.5 | 63.8 |

| Neurobiology of Disease | 80.9 | 62.5 |

| Development/Plasticity/Repair | 81.6 | 63.2 |

Crucially, ablation studies demonstrated that LLMs' superior performance depends on integrating information throughout research abstracts, including methodological details, rather than relying solely on local context in results sections [2]. When restricted to results passages only, model performance declined significantly, indicating that genuine understanding requires grounding predictions in methodological context [2]. This suggests that these models develop some capacity to ground scientific concepts in experimental practices rather than merely recognizing surface linguistic patterns.

Mechanistic Evidence for Symbol Grounding

Beyond behavioral benchmarks, mechanistic analyses provide direct evidence for symbol grounding processes in AI systems. Causal and saliency-flow analyses within Transformer architectures reveal that emergent symbol grounding arises in middle-layer aggregate attention heads, which functionally route environmental tokens to support reliable grounding of linguistic outputs [1]. When these specific components are disabled, grounding capabilities deteriorate significantly, establishing their mechanistic necessity [1].

Notably, comparative analyses indicate that LSTMs lack such specialized grounding mechanisms and consistently fail to acquire genuine grounding both behaviorally and at the circuit level [1]. This suggests that specific architectural features—particularly the self-attention mechanisms in Transformers—enable the development of symbol grounding capabilities that are absent in earlier neural network architectures [1] [3].

Technical Implementation: Methods and Protocols

Experimental Protocol: BrainBench for Grounding Evaluation

The BrainBench protocol provides a standardized methodology for evaluating symbol grounding capabilities in AI systems [2]. The benchmark consists of 200 test items derived from recent journal articles, each presenting two versions of an abstract: the original and an altered version that substantially changes the study's outcome while maintaining overall coherence [2]. Test-takers (both AI and human) must identify the correct (original) abstract based on methodological plausibility and consistency with established neuroscience knowledge.

Procedure:

- Stimulus Presentation: System receives paired abstracts (original and altered)

- Methodology Analysis: System processes methodological descriptions and theoretical background

- Outcome Evaluation: System evaluates plausibility of stated results given methods

- Selection: System selects which abstract represents the actual study outcome

- Confidence Assessment: System rates confidence in its prediction

- Performance Validation: Accuracy is measured against ground truth

This protocol specifically targets forward-looking prediction capabilities rather than backward-looking knowledge retrieval, emphasizing genuine understanding over memorization [2]. The altered abstracts are created by neuroscience experts to ensure they are methodologically coherent but scientifically implausible, requiring deep understanding rather than surface pattern matching [2].

Multimodal Pre-training for Enhanced Grounding

Implementing effective symbol grounding in neuroscience AI requires specialized pre-training approaches that integrate multiple data modalities [4] [3]. The following protocol outlines a representative methodology for developing grounded neuroscience AI systems:

Data Collection and Curation:

- Gather diverse neuroscience data: neuroimaging (fMRI, EEG), genomic sequences, clinical records, chemical structures, and scientific literature

- Implement rigorous data quality controls: factual accuracy, contextual accuracy, consistency, and completeness [6]

- Address missing data, inconsistencies, and duplicates through normalization procedures

- Ensure regulatory compliance (FDA, EMA guidelines) for clinical data [6]

Multimodal Model Architecture:

- Implement transformer-based architecture with specialized attention mechanisms

- Design modality-specific encoders for different data types (genomic, imaging, text)

- Create cross-modal attention layers to enable information integration across modalities

- Incorporate biological constraints and domain knowledge to improve interpretability [3]

Pre-training Procedure:

- Employ self-supervised learning on large-scale multimodal datasets

- Utilize contrastive learning objectives to align representations across modalities

- Implement masked modeling approaches across different data types

- Scale model parameters, training data, and computational resources proportionally [3]

Fine-tuning and Validation:

- Specialize pre-trained models on specific neuroscience tasks (diagnosis, drug discovery)

- Validate grounding through forward-looking benchmarks like BrainBench

- Perform mechanistic analysis to identify grounding-related components

- Implement continuous monitoring for data drift and performance maintenance [6]

Visualizing Symbol Grounding Architectures

The Neuroscience AI Research Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Neuroscience AI with Symbol Grounding

| Tool/Category | Function | Grounding Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| BrainBench [2] | Forward-looking benchmark for predicting neuroscience results | Evaluates symbolic understanding beyond memorization |

| Transformer Architectures [3] | Self-attention mechanisms for processing sequential data | Enables integration across methodological context and results |

| Multimodal Language Models (MLMs) [4] [6] | Integration of diverse data types (genomic, clinical, imaging) | Creates cross-modal references for symbol grounding |

| Brain Foundation Models (BFMs) [3] | Specialized models for neural signal processing | Grounds concepts in direct brain activity measurements |

| Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) [7] | Dynamic integration of knowledge bases during inference | Connects symbols to established scientific knowledge |

| Self-Supervised Learning [3] | Pre-training on unlabeled data across modalities | Enables learning of grounded representations without explicit labeling |

| Mechanistic Circuit Analysis [1] | Identification of grounding-related components in models | Validates genuine understanding versus surface pattern matching |

| Dynamic Medical Graph Framework [8] | Temporal and structural modeling of health data | Grounds concepts in disease progression and patient trajectories |

Implications for Drug Discovery and Clinical Translation

The symbol grounding problem has profound practical implications for AI applications in neuroscience drug discovery and development. Multimodal language models are increasingly employed to integrate genomic, chemical, clinical, and structural information to identify therapeutic targets and predict clinical responses [4] [9]. These applications depend critically on the models' ability to ground their symbolic manipulations in real biological and clinical phenomena rather than merely exploiting statistical patterns in training data.

In pharmaceutical research, MLMs analyze diverse data sources—including genomic sequences, protein structures, clinical records, and scientific literature—to identify candidate molecules that simultaneously satisfy multiple criteria: efficacy, safety, and bioavailability [4] [5]. The grounding of symbolic representations in these varied modalities enables more reliable prediction of clinical outcomes and better stratification of patient populations for clinical trials [4] [6]. For example, MLMs can correlate genetic variants with clinical biomarkers, optimizing trial design and improving probability of success [4].

The transition from unimodal to multimodal AI in drug development represents a crucial step toward addressing the symbol grounding problem [6]. Traditional approaches analyzing single data sources in isolation lack the cross-modal references necessary for robust symbol grounding, whereas integrated multimodal systems can develop representations that connect molecular structures to clinical outcomes through intermediate biological mechanisms [4] [5]. This enhanced grounding directly impacts drug development efficiency, with AI-designed molecules like DSP-1181 achieving clinical trial entry in under one year—an unprecedented timeline in the pharmaceutical industry [5].

Future Directions and Challenges

Despite significant progress, substantial challenges remain in achieving comprehensive symbol grounding in neuroscience AI. Current systems still face limitations in genuine understanding, particularly when confronted with novel scenarios outside their training distribution [1] [7]. The theoretical limits established by algorithmic information theory suggest that no closed, self-contained symbolic system can guarantee universal symbol grounding, necessitating open-ended, dynamically adaptive approaches [1].

Future research directions should focus on several key areas. First, developing more sophisticated benchmarks that probe grounding capabilities across a wider range of neuroscientific contexts and task types [2] [3]. Second, creating architectural innovations that more effectively integrate embodied, interactive components to provide richer grounding experiences [1] [7]. Third, establishing formal frameworks for evaluating and ensuring grounding quality in clinical and research applications [6].

The mutual influence between neuroscience and AI promises continued progress on these challenges [3]. As neuroscientific insights inform more biologically plausible AI architectures, and AI capabilities enable more sophisticated neuroscience research, this virtuous cycle may gradually narrow the grounding gap [3]. However, ethical considerations around data privacy, algorithmic bias, and clinical responsibility must remain central to this development process, particularly as these systems increasingly influence patient care and therapeutic development [7] [6].

The symbol grounding problem in neuroscience AI thus represents not merely a technical obstacle but a fundamental aspect of developing artificial systems that genuinely understand and can responsibly advance neuroscientific knowledge and clinical practice.

Developmental vs. Non-Developmental Learning Pathways for Brain-Inspired AI

The pursuit of artificial intelligence (AI) that emulates human cognitive capabilities has long been inspired by the brain. Traditionally, this "brain-inspired" agenda has followed a non-developmental pathway, constructing AI systems with fixed, pre-defined architectures that mimic specific, mature neurobiological functions [10] [11]. However, a nascent developmental pathway is gaining traction, proposing that AI should acquire intelligence through a staged, experience-dependent learning process reminiscent of human cognitive development [12] [13]. This whitepaper examines the core principles, experimental evidence, and methodological frameworks of these two divergent pathways. Framed within a broader thesis on their interplay, we argue that the emergence of Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) is not only catalyzing progress in both directions but is also creating a novel, powerful tool for testing neuroscientific hypotheses, thereby closing the loop between AI development and brain research.

The Non-Developmental Pathway: Engineering Brain-Inspired Modules

The non-developmental pathway seeks to directly reverse-engineer specific cognitive functions of the mature brain into AI architectures. This approach does not aim to replicate the developmental journey but instead focuses on the end-state principles of neural computation.

Core Principles and Architectures

This pathway is characterized by the design of modular components, each inspired by the functional role of a specific brain region or network [14]. Key innovations include:

- Specialized Modules for Planning: The Modular Agentic Planner (MAP) is a archetypal example, incorporating distinct modules inspired by prefrontal cortex (PFC) subregions [14]. These include a TaskDecomposer (anterior PFC), which breaks down goals into subgoals; an Actor (dorsolateral PFC), which proposes actions; and a Monitor (Anterior Cingulate Cortex), which assesses action validity and provides feedback.

- Oscillatory Synchronization for Graph Learning: Moving beyond static graph convolutions, the HoloGraph model treats graph nodes as coupled oscillators, drawing direct inspiration from neural synchrony in the brain [15]. Its dynamics are governed by a Kuramoto-style model, enabling it to overcome issues like over-smoothing and perform complex reasoning on graph-structured data.

Quantitative Performance of Non-Developmental Models

The table below summarizes the demonstrated capabilities of key non-developmental models on challenging benchmarks, highlighting their performance without a developmental trajectory.

Table 1: Performance of Non-Developmental, Brain-Inspired AI Models

| Model/Architecture | Core Inspiration | Key Benchmark Tasks | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modular Agentic Planner (MAP) [14] | Prefrontal cortex modularity | Graph Traversal, Tower of Hanoi, PlanBench, StrategyQA | Significant improvements over standard LLMs (e.g., GPT-4) and other agentic baselines; effective transfer across tasks. |

| HoloGraph [15] | Neural oscillatory synchronization | Graph reasoning tasks | Effectively addresses over-smoothing in GNNs; demonstrates potential for complex reasoning on graphs. |

| Hierarchical Reasoning Model (HRM) [16] | Brain's multi-timescale processing | ARC-AGI, Sudoku-Extreme (9x9), Maze-Hard (30x30) | Outperformed much larger LLMs; achieved 100% on 4x4 mazes and 98.7% on 30x30 mazes with only 1000 training examples. |

Experimental Protocol for a Non-Developmental Architecture

Objective: To evaluate the efficacy of a brain-inspired modular planning architecture (e.g., MAP) on a complex reasoning task.

- Task Formulation: Define a planning task ({{{\mathcal{T}}}}=({{{\mathcal{S}}}},{{{\mathcal{A}}}},T,{s}{0},{s}{goal})) where the transition function (T) is described in natural language rather than formal specification [14].

- Module Instantiation: Implement distinct LLM-based modules (TaskDecomposer, Actor, Monitor, Predictor, Evaluator, Coordinator). Each module is primed with a specific prompt detailing its role and provided with ≤3 in-context learning examples [14].

- Algorithm Execution: Execute the MAP algorithm, which involves:

- The TaskDecomposer receiving the start and goal states to generate a sequence of subgoals.

- The Actor proposing potential actions for a current state and subgoal.

- The Monitor validating proposed actions against task rules.

- The Predictor and Evaluator performing state prediction and evaluation for tree search.

- The Coordinator managing the overall process and subgoal progression.

- Evaluation: Compare the generated plan against the ground-truth optimal plan. Metrics include success rate, plan length optimality, and computational efficiency compared to baseline LLMs and other agentic systems [14].

Diagram 1: MAP's modular, PFC-inspired architecture.

The Developmental Pathway: Learning a Foundation Model

In stark contrast, the developmental pathway posits that intelligence emerges from a structured learning process, analogous to human cognitive development. This view recasts the protracted "helpless" period of human infancy not as a state of brain immaturity, but as a critical phase for self-supervised learning of a foundational world model [12] [13].

Core Principles and Evidence

- Infant Helplessness as Pre-training: Cross-species neurodevelopmental alignments show that human brains at birth are not exceptionally immature. Instead, the infant's extended period of dependency is leveraged for intensive, self-supervised learning from multi-sensory data, building a "foundation model" that underpins all future learning and rapid generalization [12].

- Efficiency of Biological Learning: Unlike large AI models that require massive data and energy, human infants achieve robust foundational learning with remarkable efficiency, offering an inspiration for more sustainable and powerful AI [13].

Experimental Protocol for a Developmental Pathway

Objective: To utilize MLLMs as in-silico models for testing hypotheses of human concept development, such as the emergence of category-specific representations.

- Stimulus Selection: Curate a comprehensive set of object concepts (e.g., 1,854 everyday items) spanning diverse categories (e.g., living, non-living, faces, places) [17].

- Odd-One-Out Task Administration: Present triplets of concepts to both human participants and MLLMs (e.g., text-only LLMs and vision-augmented MLLMs) and collect their "odd-one-out" judgments. Scale this to millions of trials for the AI models [17].

- Concept Space Embedding: Use the collected triplet judgments from the AI to construct a low-dimensional concept embedding space (e.g., 66-dimensional) for each model.

- Neuroscientific Validation: Compare the AI-derived concept dimensions with human neuroimaging data (fMRI). Analyze the alignment between specific dimensions in the AI's embedding space and the functional profiles of well-defined brain regions like the Fusiform Face Area (FFA), Parahippocampal Place Area (PPA), and Extrastriate Body Area (EBA) [17].

Diagram 2: Convergent learning in infants and MLLMs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and methodological "reagents" essential for research at the intersection of brain-inspired AI and neuroscience.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Brain-Inspired AI Research

| Research Reagent | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Modular Agentic Planner (MAP) Framework [14] | A blueprint for constructing planning systems from specialized, interacting LLM modules. | Implementing and testing hypotheses about prefrontal cortex modularity in complex task solving. |

| Kuramoto-style Oscillatory Synchronization Model [15] | A mathematical framework for modeling the dynamics of coupled oscillators, inspired by neural synchrony. | Developing graph neural networks (e.g., HoloGraph) that overcome over-smoothing and exhibit advanced reasoning. |

| Odd-One-Out Triplet Task Paradigm [17] | A cognitive task used to probe the conceptual structure and relationships within a model's or human's internal representations. | Quantifying the alignment between AI-derived concept spaces and human brain representations. |

| Cross-Species Neurodevelopmental Alignment Data [12] [13] | Datasets and models that align neurodevelopmental events across species to assess brain maturity. | Providing evidence for the "foundation model" hypothesis of human infant learning. |

| Geometric Scattering Transform (GST) [15] | A signal processing technique used to construct graph wavelets for analyzing functional brain data. | Serving as basis functions for modeling neural oscillators in HoloBrain, a model of whole-brain oscillatory synchronization. |

Impact of Multimodal LLMs on Neuroscience Research

Multimodal LLMs are revolutionizing neuroscience research by serving as computable in-silico models that exhibit emergent brain-like properties. This creates a powerful feedback loop for testing developmental and non-developmental theories of intelligence.

- Validation of Brain-Inspired AI Principles: The finding that MLLMs spontaneously develop internal representations that align with the ventral visual stream in the human brain provides strong, data-driven validation for the core tenets of brain-inspired AI [17]. This convergence suggests that MLLMs are capturing fundamental computational principles of biological intelligence.

- A New Framework for Cognitive Neuroscience: MLLMs offer a novel, high-dimensional experimental substrate. Researchers can perform "ablation studies" on these models, manipulate their training data, and analyze their internal states in ways that are impossible with human brains, thereby generating new, testable hypotheses about neural computation [17]. For instance, the discovery of 66 interpretable conceptual dimensions within an MLLM directly informs the search for the fundamental dimensions of human semantic memory [17].

Table 3: Quantitative Evidence of MLLM-Brain Alignment

| Study Focus | MLLM Capability / Emergent Property | Quantitative Finding | Neuroscientific Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concept Organization [17] | Formation of an interpretable, 66-dimensional concept space from "odd-one-out" judgments. | Dimensions cleanly separated concepts (e.g., living vs. non-living, faces vs. places). | Alignment with functional specialization in the ventral visual stream (FFA, PPA, EBA). |

| Model vs. Human Judgment [17] | Higher consistency with human "odd-one-out" choices. | Multimodal models (GeminiProVision, Qwen2_VL) showed higher human-likeness than text-only LLMs. | Demonstrates that multimodal training grounds models in human-like conceptual understanding. |

| Internal Representation Dimensionality [16] | Emergent separation of representational capacity in a hierarchical model (HRM). | High-level module Participation Ratio (PR=89.95) vs. low-level (PR=30.22), a ratio of ~2.98. | Closely mirrors the PR ratio observed in the mouse cortex (~2.25), suggesting a general principle. |

The developmental and non-developmental pathways for brain-inspired AI represent complementary strategies in the quest for advanced machine intelligence. The non-developmental pathway, exemplified by modular architectures and oscillatory models, offers a direct engineering route to imbue AI with specific, robust cognitive functions. The developmental pathway, inspired by infant learning, promises a more fundamental approach to creating general and efficient intelligence through structured, self-supervised experience. The rise of MLLMs is profoundly impacting this landscape, serving as a catalytic force that validates brain-inspired design principles and provides an unprecedented experimental toolkit for neuroscience. This synergistic relationship is rapidly accelerating progress, bringing the fields of AI and neuroscience closer together in the shared mission to understand and replicate intelligence.

The human brain is a fundamentally multimodal system, natively integrating streams of information from vision, language, and other senses. Traditional artificial intelligence models, with their unimodal focus, have provided limited windows into this complex, cross-modal processing. The emergence of Multimodal Large Language Models (LLMs) and Vision-Language Models (VLMs) represents a paradigm shift, offering a new class of computational tools that mirror the brain's integrative capabilities. This whitepaper details how these models are revolutionizing neuroscience research by providing a testable framework for investigating the neural mechanisms of multimodal integration, accelerating the prediction of experimental outcomes, and creating novel pathways for decoding brain activity. Framed within a broader thesis on their transformative impact, this document provides a technical guide to the experimental protocols, key findings, and essential research tools at this frontier.

Neural Data Acquisition and Preprocessing Protocols

A critical foundation for studying multimodal integration is the acquisition of high-fidelity neural data collected during exposure to naturalistic, multimodal stimuli.

Intracranial Recordings with Naturalistic Stimuli

Stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG) provides direct, high-temporal-resolution measurements of neural activity. The following protocol is adapted from studies investigating vision-language integration [18].

- Stimulus Presentation: Participants watch feature-length movies from annotated banks (e.g., the Aligned Multimodal Movie Treebank, AMMT). Movies provide dynamic, simultaneous visual and linguistic input.

- Neural Recording: Intracranial field potentials are recorded using SEEG electrodes at a high sampling rate (e.g., 2 kHz) [18].

- Event Alignment: The continuous neural and movie data are parsed into discrete, time-locked events.

- Language-aligned events: Word onsets with their sentence context and the corresponding movie frame at the moment of utterance.

- Vision-aligned events: Visual scene cuts detected algorithmically (e.g., with PySceneDetect) and the closest subsequent sentence [18].

- Neural Response Extraction: For each event, a 4000ms window of neural activity is extracted, spanning 2000ms before to 2000ms after the event. This window is then segmented into smaller sub-windows for analysis [18].

Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) for Decoding

fMRI offers whole-brain coverage, which is valuable for decoding studies. The protocol for decoding spoken text is as follows [19]:

- Task Paradigm: fMRI data is collected during structured human-human or human-robot conversations, recording brain activity and conversational signals synchronously.

- Brain Parcellation: The raw, low-resolution fMRI signals are refined using brain parcellation techniques to enhance signal quality and localization.

- Preprocessing: Standard fMRI preprocessing steps are applied, including motion correction, normalization, and hemodynamic response function (HRF) deconvolution to relate neural activity to the BOLD signal.

Table 1: Key Neural Data Acquisition Methods

| Method | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Resolution | Primary Use Case | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG) [18] | Very High (milliseconds) | High (precise neural populations) | Probing neural sites of multimodal integration | Direct neural recording with high fidelity during complex tasks. |

| Functional MRI (fMRI) [19] [20] | Low (seconds) | Whole-brain | Decoding stimuli or text from brain activity; mapping networks | Comprehensive brain coverage for decoding and network analysis. |

Multimodal Model Architectures and Experimental Frameworks

Architectures for Probing and Decoding

Different model architectures are employed based on the research goal: probing neural activity or decoding it.

- Probing Integration Sites: Models like CLIP, SLIP, ALBEF, and BLIP are used. Their internal representations are extracted and used to predict neural activity via linear regression. Integration sites are identified where multimodal models significantly outperform unimodal or linearly-integrated models [18].

- Decoding Text from Brain Activity: An end-to-end Multimodal LLM architecture (e.g., BrainDEC) is used [19]:

- Encoder: A transformer-based encoder, often pre-trained on an image-captioning-like task to map sequences of fMRI data to an embedding, is used. It may incorporate an augmented embedding layer and a customized attention mechanism.

- Frozen LLM: A large language model is kept frozen.

- Instruction Tuning: The encoder's output is aligned with the frozen LLM's embedding space via a projection layer. The interlocutor's text is fed to the LLM as an instruction, guiding the generation of the participant's predicted textual response [19].

A Controlled Framework for Neuron-Level Analysis

To move beyond model outputs and study fine-grained processing, a neuron-level encoding framework has been developed [20].

- Definition of an Artificial Neuron (AN): In transformer-based VLMs (e.g., CLIP, METER), an "artificial neuron" is defined as a single head in a multi-head attention module. This provides a fine-grained unit of analysis [20].

- Temporal Response Construction: The activation of each AN is computed over the time series of movie stimuli.

- Hemodynamic Convolution: The temporal response is convolved with a canonical Hemodynamic Response Function (HRF) to account for the delay in the fMRI BOLD signal.

- Sparse Dictionary Learning (SDL): HRF-convolved responses are fed to an SDL algorithm to extract representative temporal activation patterns, which serve as regressors.

- Neural Encoding Model: These regressors are used in a sparse regression model to predict the activity of individual brain voxels, treated as biological neurons (BNs). The predicted voxel responses can be aggregated to analyze functional brain networks (FBNs) [20].

Diagram 1: Neuron-level encoding framework.

Key Quantitative Findings and Experimental Evidence

Research leveraging these protocols has yielded several evidence-based findings on the alignment between multimodal models and neural processing.

Identification of Multimodal Integration Sites

Using SEEG and model comparison, a significant number of neural sites exhibit properties of multimodal integration [18].

- Prevalence: On average, 12.94% (141 out of 1090) of all recorded neural sites show significantly better prediction from multimodal models [18].

- Brain Regions: Identified regions include the superior temporal cortex, middle temporal cortex, inferior parietal cortex, supramarginal gyrus, superior frontal lobe, caudal middle frontal cortex, and pars orbitalis [18].

- Model Performance: CLIP-style contrastive training was found to be particularly effective at predicting neural activity at these integrative sites [18].

Table 2: Key Evidence from Multimodal Integration Studies

| Finding Category | Key Evidence | Quantitative Result / Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Identification of Integration Sites [18] | Multimodal models (e.g., CLIP) predict SEEG activity better than unimodal models in specific brain regions. | ~12.9% of neural sites (141/1090) are identified as multimodal integration sites. |

| Superior Predictive Power of LLMs [2] | LLMs (e.g., BrainGPT) outperform human experts in predicting novel neuroscience results on the BrainBench benchmark. | LLMs averaged 81.4% accuracy vs. human experts' 63.4% accuracy. |

| Architectural Influence on BN Activation [20] | CLIP's independent encoders vs. METER's cross-modal fusion lead to different brain network activation patterns. | CLIP shows modality-specific specialization; METER shows unified cross-modal activation. |

| Functional Redundancy & Polarity [20] | VLMs exhibit overlapping neural representations and mirrored activation trends across layers, similar to the brain. | Mirrors the brain's fault-tolerant processing and complex, bidirectional information flow. |

Superior Predictive Power of LLMs in Neuroscience

LLMs demonstrate a remarkable capacity to integrate scientific knowledge for forward-looking prediction.

- BrainBench Benchmark: A forward-looking benchmark tests the ability to predict experimental outcomes by choosing the original abstract from a pair where one has an altered result [2].

- LLM vs. Human Expert Performance: General-purpose LLMs significantly surpassed human neuroscience experts, achieving an average accuracy of 81.4% compared to 63.4% for experts [2].

- Domain-Specific Tuning: BrainGPT, an LLM further tuned on the neuroscience literature, performed even better, demonstrating the value of specialized training [2].

- Basis for Prediction: LLMs' performance dropped significantly when provided only with the results passage, indicating they integrate information from the methods and background sections of abstracts to make predictions, rather than relying on superficial cues [2].

Architectural Impact on Brain-Like Properties

The specific architecture of a VLM directly influences how its internal processing mirrors the brain [20].

- CLIP vs. METER: CLIP, with its independent vision and language branches connected via contrastive loss, fosters modality-specific specialization in its artificial neurons. In contrast, METER, which uses cross-modal attention (fusion) layers, leads to more unified, modality-invariant representations [20].

- Implication: This results in distinct patterns of biological neuron activation, demonstrating that model architecture is a key determinant in developing more brain-like artificial intelligence.

Diagram 2: VLM architectures and their neural correlates.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details key computational and data resources essential for research in this domain.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource Name / Type | Function / Purpose | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG) [18] | Records high-fidelity neural activity from intracranial electrodes during complex, naturalistic stimuli. | Provides high temporal resolution data crucial for studying the dynamics of multimodal integration. |

| Aligned Multimodal Movie Treebank (AMMT) [18] | A stimulus dataset of feature-length movies with aligned word-onset times and visual scene cuts. | Enables precise alignment of multimodal stimuli (language and vision events) with neural recordings. |

| Vision-Language Models (VLMs) (CLIP, METER) [18] [20] | Pretrained models used as sources of artificial neuron activity to predict and analyze brain data. | CLIP uses contrastive learning; METER uses cross-attention. Architectural choice influences brain alignment. |

| BrainBench [2] | A forward-looking benchmark for evaluating the prediction of novel neuroscience results. | Used to test the ability of LLMs and humans to predict experimental outcomes from abstract methods. |

| Sparse Dictionary Learning (SDL) [20] | A technique to extract representative temporal activation patterns from artificial neuron responses. | Creates efficient regressors for neural encoding models that predict biological neuron (voxel) activity. |

| Neural Encoding Model (Sparse Regression) [20] | A statistical model that uses artificial neuron patterns to predict brain activity. | The core analytical tool for quantifying the alignment between model representations and neural data. |

Multimodal LLMs and VLMs have transcended their roles as mere engineering achievements to become indispensable instruments for neuroscience. They provide a quantitative, testable framework for probing the neural underpinnings of multimodal integration, decoding language from brain activity, and predicting scientific outcomes. The rigorous experimental protocols and findings detailed in this whitepaper underscore a growing and necessary synergy between artificial intelligence and neuroscience. This synergy promises not only to deepen our fundamental understanding of the brain but also to accelerate the development of diagnostics and therapeutics for neurological disorders, ultimately fulfilling the promise of brain-inspired AI and AI-enhanced brain science.

The integration of artificial intelligence into neuroscience represents a paradigm shift in how researchers approach the complexity of neural systems. Within this transformation, a new class of specialized large language models (LLMs) has emerged, designed specifically to navigate the unique challenges of neuroscientific inquiry. These models, exemplified by BrainGPT, move beyond general-purpose AI capabilities to offer targeted functionalities that accelerate discovery and enhance analytical precision. Their development marks a critical evolution in the impact of multimodal LLMs on neuroscience research, enabling unprecedented synthesis of literature, prediction of experimental outcomes, and interpretation of complex neurological data. This whitepaper examines the technical architecture, performance benchmarks, and practical implementation of specialized LLMs tailored for neuroscience domains, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for leveraging these tools in scientific investigation and therapeutic development.

BrainGPT: Architectural Framework and Capabilities

BrainGPT represents a significant advancement in specialized AI models for neuroscience, with two distinct implementations demonstrating the versatility of domain-specific adaptation. The first variant focuses on 3D brain CT radiology report generation (RRG), addressing critical limitations in medical image interpretation [21]. This model was developed using a clinically visual instruction tuning (CVIT) approach on the curated 3D-BrainCT dataset comprising 18,885 text-scan pairs, enabling sophisticated interpretation of volumetric medical images that traditional 2D models cannot process effectively [21] [22]. The architectural innovation lies in its anatomy-aware fine-tuning and clinical sensibility, which allows the model to generate diagnostically relevant reports with precise spatial localization of neurological features.

A second BrainGPT implementation specializes in predicting experimental outcomes in neuroscience research [2]. This model was fine-tuned on extensive neuroscience literature to forecast research findings, demonstrating that AI can integrate noisy, interrelated findings to anticipate novel results better than human experts [2] [23]. The model's predictive capability stems from its training on vast scientific corpora, allowing it to identify underlying patterns across disparate studies that may elude human researchers constrained by cognitive limitations and literature overload.

Table: BrainGPT Implementation Comparison

| Implementation | Primary Function | Training Data | Architecture | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D CT Report Generation | Automated radiology report generation | 18,885 text-scan pairs from 3D-BrainCT dataset | Clinically visual instruction tuning (CVIT) | Volumetric image interpretation beyond 2D limitations |

| Experimental Outcome Prediction | Forecasting neuroscience research results | Broad neuroscience literature | Fine-tuned LLM (adapted from Mistral) | Forward-looking prediction vs. backward-looking retrieval |

The technical sophistication of BrainGPT models reflects a broader trend in neuroscience AI: the movement from general-purpose models to highly specialized systems engineered for specific research workflows. This specialization enables more accurate, clinically relevant outputs that align with the complex, multi-dimensional nature of neurological data analysis.

Performance Benchmarks and Quantitative Evaluation

Evaluation Metrics and Comparative Performance

Specialized LLMs for neuroscience require equally specialized evaluation frameworks that capture their clinical and scientific utility. For the radiology-focused BrainGPT, traditional NLP metrics such as BLEU and ROUGE proved inadequate for assessing diagnostic quality, leading to the development of the Feature-Oriented Radiology Task Evaluation (FORTE) [21]. This novel evaluation scheme captures the clinical essence of generated reports by focusing on four essential keyword components: degree, landmark, feature, and impression [21]. Under this framework, BrainGPT achieved an average FORTE F1-score of 0.71, with component scores of 0.661 (degree), 0.706 (landmark), 0.693 (feature), and 0.779 (impression) [21].

Perhaps more significantly, in Turing-like tests evaluating linguistic style and clinical acceptability, 74% of BrainGPT-generated reports were indistinguishable from human-written ground truth [21] [22]. This demonstrates not only technical competence but the model's ability to produce outputs that integrate seamlessly into clinical workflows, a critical requirement for real-world adoption.

The predictive BrainGPT variant demonstrated remarkable performance on BrainBench, a forward-looking benchmark designed to evaluate prediction of neuroscience results [2]. In comparative assessments, this specialized model achieved 86% accuracy in predicting experimental outcomes, surpassing both general-purpose LLMs (81.4% average accuracy) and human neuroscience experts (63.4% accuracy) [2] [23]. Even when restricting human responses to only those with the highest domain expertise, accuracy reached just 66%, still significantly below LLM performance [2].

Table: Performance Comparison on BrainBench

| Model/Expert Type | Accuracy | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| BrainGPT (neuroscience-specialized) | 86% | Fine-tuned on neuroscience literature |

| General-purpose LLMs (average) | 81.4% | 15 different models tested |

| Human neuroscience experts (average) | 63.4% | 171 screened experts |

| Human experts (top 20% expertise) | 66.2% | Restricted to high self-reported expertise |

Advanced Capabilities and Real-World Validation

Beyond quantitative metrics, specialized neuroscience LLMs demonstrate qualitatively advanced capabilities with significant research implications. The predictive BrainGPT model exhibited well-calibrated confidence, with higher confidence correlating with greater accuracy—a crucial feature for reliable research assistance [23]. This confidence calibration enables potential hybrid teams combining human expertise and AI capabilities for more accurate predictions than either could achieve alone [23].

A compelling real-world validation emerged when researchers tested the model on a potential Parkinson's disease biomarker discovered by Michael Schwarzschild from Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital [24]. Despite the finding's innovative nature, BrainGPT correctly identified this result as most likely, demonstrating an ability to uncover overlooked research and connect disparate scientific literature that had hinted at similar findings decades earlier [24].

Methodological Framework: Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Clinical Visual Instruction Tuning for 3D CT Interpretation

The development of BrainGPT for radiology report generation employed a sophisticated methodological approach centered on clinical visual instruction tuning (CVIT) [21]. This process involved several critical stages:

Dataset Curation: The foundation was the creation of the 3D-BrainCT dataset, consisting of 18,885 text-scan pairs with comprehensive lesion details including degree, spatial landmarks, and diagnostic impressions of both neuronal and vascular CT features [21]. This scale and specificity addressed the previously limited exploration of 3D medical images in MLLM applications.

Instruction Tuning Variants: Researchers implemented four distinct fine-tuning conditions: regular visual instruction tuning (RVIT) with plain instruction and in-context example instruction, and clinical visual instruction tuning (CVIT) with template instruction and keyword instruction [21]. This graduated approach enabled precise assessment of how different levels of clinical guidance affected model performance.

Sentence Pairing and Evaluation: To address the list-by-list architecture of brain CT reports, the team applied sentence pairing to decompose multi-sentence paragraphs into smaller semantic granularity [21]. This process significantly enhanced traditional metric scores, increasing METEOR by 5.28 points, ROUGE-L by 6.48 points, and CIDEr-R by 114 points on average [21].

BrainBench Framework for Predictive Assessment

The evaluation of BrainGPT's predictive capabilities employed the novel BrainBench framework, specifically designed for forward-looking assessment of scientific prediction abilities [2]. The methodology encompassed:

Benchmark Construction: BrainBench consists of pairs of neuroscience study abstracts from the Journal of Neuroscience, with one version representing the actual published abstract and the other containing a plausibly altered outcome [2]. These alterations were created by domain experts to maintain coherence while substantially changing the study's conclusions.

Testing Protocol: Both LLMs and human experts were tasked with selecting the correct (original) abstract from each pair [2]. For LLMs, this involved computing the likelihood of each abstract using perplexity scoring, while human experts underwent screening to confirm their neuroscience expertise before participation.

Controlled Analysis: To determine whether LLMs were genuinely integrating methodological information or simply relying on local context in results sections, researchers conducted ablation studies using only results passages and contexts with randomly swapped sentences from the same subfield [2]. These controls confirmed that LLMs were indeed integrating information across the entire abstract, not just results sections.

Implementing specialized LLMs for neuroscience research requires both computational resources and domain-specific assets. The following table outlines key components of the research toolkit for developing and deploying models like BrainGPT:

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Neuroscience LLMs

| Resource | Function | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| 3D-BrainCT Dataset | Training data for radiology report generation | 18,885 text-scan pairs with comprehensive lesion details [21] |

| BrainBench Benchmark | Forward-looking evaluation of predictive capabilities | Abstract pairs from Journal of Neuroscience with original vs. altered outcomes [2] |

| FORTE Evaluation Scheme | Clinical essence assessment of generated reports | Feature-oriented evaluation focusing on degree, landmark, feature, and impression [21] |

| Clinical Visual Instruction Tuning (CVIT) | Enhancing medical domain knowledge in foundation models | Anatomy-aware fine-tuning with structured clinical templates [21] |

| DANDI Archive | Neurophysiology data repository for model training and validation | Hundreds of datasets with brain activity recordings for developing specialized applications [24] |

These resources collectively enable the development of neuroscience-specialized LLMs that transcend general-purpose capabilities, offering targeted functionality for specific research challenges. The combination of domain-specific training data, specialized evaluation frameworks, and clinical integration methodologies distinguishes these implementations from conventional AI applications in neuroscience.

Implementation Considerations and Future Directions

The successful implementation of specialized LLMs in neuroscience research requires careful attention to several critical factors. Data quality and domain relevance emerge as paramount concerns, as evidenced by the curated 3D-BrainCT dataset's crucial role in BrainGPT's radiology capabilities [21]. Similarly, evaluation specificity must align with clinical and research objectives, moving beyond traditional NLP metrics to domain-relevant assessments like FORTE and BrainBench [21] [2].

Future developments in this space will likely focus on increased multimodal integration, combining neuroimaging data, electrophysiological recordings, and scientific literature within unified architectures [24]. The CellTransformer project, which applies LLM-inspired approaches to cellular organization data, demonstrates the potential for cross-pollination between neurological data types [24]. Additionally, explainability and interpretability enhancements will be crucial for clinical adoption, with techniques like LLM-augmented explainability pipelines already emerging to identify predictive features in complex neurological datasets [24].

As these specialized models evolve, they promise to transform not only how neuroscience research is conducted but how scientific insights are generated and validated. The demonstrated ability of BrainGPT to predict experimental outcomes and generate clinically relevant interpretations suggests a future where human-machine collaboration becomes fundamental to neuroscientific discovery, potentially accelerating therapeutic development and deepening our understanding of neural systems through augmented intelligence.

From Theory to Practice: MLLM Applications in Neuroscience and Medicine

The integration of multimodal large language models (MLLMs) with non-invasive brain imaging techniques is revolutionizing neuroscience research, particularly in the domain of decoding spoken language from brain activity. This convergence represents a fundamental shift from traditional brain-computer interfaces, offering unprecedented capabilities for translating thought to text without surgical intervention. Modern MLLMs are attempting to circumvent the symbol grounding problem—a fundamental limitation of pure language models where meanings of words are not grounded in real-world experience—by linking linguistic knowledge with other modalities such as vision and, crucially, neural activity patterns [25].

The emergence of this technology carries profound implications for both basic neuroscience and clinical applications. For individuals with severe communication impairments due to conditions like ALS, locked-in syndrome, aphasia, or brainstem stroke, non-invasive language decoding offers a potential pathway to restore communication without the risks associated with surgical implantation [26] [27]. Furthermore, these approaches provide neuroscientists with novel tools to investigate the fundamental neural representations underlying language perception, production, and imagination, thereby bridging long-standing gaps in our understanding of human cognition.

Theoretical Foundations: From Symbol Grounding to Neural Semantics

The Symbol Grounding Problem in Neuroscience Context

Large language models (LLMs) face a fundamental limitation known as the symbol grounding problem, wherein the meanings of the words they generate are not intrinsically connected to real-world experiences or referents [25]. While these models demonstrate impressive syntactic capabilities, they are essentially "disembodied" systems operating on statistical patterns in training data without genuine understanding. This limitation becomes particularly critical when applying AI to brain decoding, where the objective is to map biologically-grounded neural representations to linguistic constructs.

MLLMs offer a potential pathway toward solving this problem by creating bridges between symbolic representations and continuous neural signals. By aligning the architecture of language models with multimodal neural data, researchers can potentially develop systems that achieve deeper semantic understanding through their connection to actual brain states [25]. This approach mirrors human concept acquisition, where concrete words (e.g., "dog," "bus") are grounded through direct perceptual and sensorimotor experiences, while abstract words (e.g., "truth," "democracy") rely more heavily on linguistic context [25].

Neural Representations of Language

The human brain represents language through distributed networks that span multiple regions, with particularly important roles played by the parietal-temporal-occipital association region and prefrontal cortex [26]. Research has demonstrated that activity in each of these regions separately represents individual words and phrases, with sufficient information to reconstruct word sequences from neural activity alone [26].

A crucial insight from recent studies is that rich conceptual representations exist outside traditional language regions. The "mind captioning" approach has demonstrated that structured semantic information can be extracted directly from vision-related brain activity without activating the canonical language network [28]. This suggests that nonverbal thought can be translated into language by decoding the structured semantics encoded in the brain's visual and associative areas, opening new possibilities for decoding mental content even when language production systems are compromised.

Technical Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Core Methodological Framework

Non-invasive language decoding from fMRI relies on establishing a mapping between the hemodynamic response measured by fMRI and linguistic representations. The fundamental workflow involves three critical stages: (1) data acquisition during language stimulation, (2) feature extraction and alignment, and (3) text generation through decoding models.

The Mind Captioning Approach

A groundbreaking method called "mind captioning" has demonstrated the ability to generate coherent, structured text from human brain activity by leveraging semantic features as an intermediate representation [28]. This approach bypasses traditional language centers altogether, instead decoding semantic information encoded in visual and associative brain regions.

The experimental protocol involves:

- Stimulus Presentation: Participants watch or listen to narrative stories while undergoing fMRI scanning, typically for extended periods (e.g., 16 hours total) to capture sufficient training data [26].

- Semantic Feature Extraction: Deep language models (e.g., DeBERTa-large) extract semantic features from captions corresponding to the presented stimuli.

- Linear Decoder Construction: Models are trained to translate whole-brain activity into semantic features of corresponding captions.

- Text Generation via Iterative Optimization: Beginning with random word sequences, the system iteratively refines candidates by aligning their semantic features with brain-decoded features through word replacement and masking processes [28].

This method has proven effective even when participants simply recall video content from memory, demonstrating that rich conceptual representations persist in nonverbal form and can be translated into structured language descriptions [28].

Brain2Qwerty: A Typing-Based Paradigm

Another innovative approach, Brain2Qwerty, decodes language production by capturing brain activity while participants type memorized sentences on a QWERTY keyboard [29]. This method leverages the neural correlates of motor intention and execution, combined with linguistic prediction.

The key methodological steps include:

- Motor-Linguistic Integration: Participants briefly memorize sentences then type them while MEG or EEG records brain activity.

- Deep Learning Architecture: The Brain2Qwerty model is specifically designed to decode sentences from neuroimaging data during typing.

- Performance Characterization: With MEG, this approach achieves a character error rate (CER) of 32% on average, with best participants reaching 19% CER, substantially outperforming EEG-based implementations (67% CER) [29].

This paradigm demonstrates that decoding benefits from incorporating motor-related neural signals and can achieve practical accuracy levels for communication applications.

Quantitative Performance Analysis

Comparative Performance Across Methods

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Non-Invasive Language Decoding Approaches

| Method | Modality | Task | Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mind Captioning | fMRI | Video description | Semantic accuracy | Captured gist of content | [28] |

| Brain2Qwerty | MEG | Sentence typing | Character Error Rate | 19-32% | [29] |

| Brain2Qwerty | EEG | Sentence typing | Character Error Rate | 67% | [29] |

| Linear Decoders | MEG/EEG | Word identification | Top-10 accuracy | ~6% | [30] |

| Deep Learning Pipeline | MEG/EEG | Word identification | Top-10 accuracy | Up to 37% | [30] |

| Huth et al. fMRI Decoder | fMRI | Story listening | Semantic fidelity | Reproduced meaning not exact words | [26] |

Impact of Experimental Parameters on Decoding Performance

Table 2: Factors Influencing Decoding Accuracy Across Studies

| Factor | Impact on Performance | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Recording Device | MEG outperforms EEG due to higher signal-to-noise ratio | p < 10⁻²⁵ in large-scale comparison [30] |

| Perception Modality | Reading outperforms listening to sentences | p < 10⁻¹⁶ in paired comparison [30] |

| Training Data Volume | Log-linear improvement with more data | Steady improvement without saturation [30] |

| Test Averaging | 2-fold improvement with 8 trial averages | Near 80% top-10 accuracy achievable [30] |

| Stimulus Type | Better for concrete vs. abstract concepts | Aligns with grounded cognition theories [25] |

Large-scale evaluations across 723 participants and approximately five million words have revealed consistent patterns in decoding performance [30]. The amount of training data per subject emerges as a critical factor, with a weak but significant trend (p < 0.05) showing improved decoding with more data per individual [30]. This suggests that for fixed recording budgets, "deep" datasets (few participants over many sessions) may be more valuable than "broad" datasets (many participants over few sessions) [30].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for fMRI Language Decoding

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging Hardware | 3T fMRI scanners, MEG systems with SQUID sensors, High-density EEG systems | Capture neural activity with sufficient spatial (fMRI) or temporal (MEG/EEG) resolution |

| Stimulus Presentation | Narrative stories, Audiobooks, Silent films, Typing interfaces | Elicit rich, naturalistic language processing in the brain |

| Computational Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow, Custom decoding pipelines | Implement and train deep learning models for brain decoding |

| Language Models | DeBERTa-large, RoBERTa, GPT architectures | Extract semantic features and generate coherent text |

| Analysis Tools | Linear decoders, Transformer networks, Contrastive learning objectives | Map neural signals to linguistic representations |

| Validation Metrics | BLEU, ROUGE, Character Error Rate, Top-k accuracy | Quantify decoding performance and semantic fidelity |

Technical Workflow: From Neural Signals to Text

The complete pipeline for decoding spoken text from fMRI involves multiple processing stages with specific technical requirements at each step:

Integration with Multimodal LLMs: Future Directions

The next frontier in non-invasive language decoding involves tighter integration with multimodal large language models that can jointly process neural signals, text, and other modalities. Current research indicates that MLLMs have the potential to achieve deeper understanding by grounding linguistic representations in neural activity patterns, effectively creating a bridge between biological and artificial intelligence [25].

Promising directions include:

- Developmental integration: Inspired by human cognitive development, future systems could learn through structured curricula that progress from simple to complex concepts, rather than training on randomly ordered datasets [25].

- Cross-modal alignment: Advanced attention mechanisms that can identify correspondences between neural activation patterns and linguistic representations across different modalities.

- Personalized decoding: Models that adapt to individual neural representations while leveraging shared linguistic structure across individuals.

Notably, LLMs have already demonstrated remarkable capabilities in predicting neuroscience results, surpassing human experts in forecasting experimental outcomes on forward-looking benchmarks like BrainBench [2]. This predictive capability suggests that LLMs have internalized fundamental patterns in neuroscience that can be leveraged to guide decoding approaches.

The decoding of spoken text from fMRI represents a transformative intersection of neuroscience and artificial intelligence, with multimodal LLMs serving as the critical enabling technology. While current systems already demonstrate the feasibility of capturing the gist of perceived or imagined language, significant challenges remain in improving accuracy, temporal resolution, and real-world applicability. The continued advancement of these technologies promises not only to restore communication for those with severe impairments but also to illuminate fundamental aspects of how the human brain represents and processes language. As multimodal LLMs become increasingly sophisticated, their integration with neural decoding approaches will likely accelerate, potentially leading to more natural and efficient brain-computer communication systems that approach human-level language understanding.

The accelerating volume of scientific literature presents a formidable challenge to human researchers, making it increasingly difficult to synthesize decades of disparate findings into novel hypotheses. Within neuroscience, this challenge is particularly acute due to the field's interdisciplinary nature, diverse methodologies, and often noisy, complex data [2]. In response to this challenge, a transformative approach has emerged: leveraging large language models (LLMs) trained on the scientific corpus not merely as information retrieval systems but as predictive engines for scientific discovery. This paradigm shifts the focus from backward-looking tasks, such as summarizing existing knowledge, to forward-looking scientific inference—the ability to forecast the outcomes of novel experiments [2] [31].

This technical guide examines the development, application, and implications of BrainBench, a forward-looking benchmark designed to quantitatively evaluate the ability of LLMs to predict experimental outcomes in neuroscience. We frame this investigation within a broader thesis on the impact of multimodal LLMs (MLLMs), which integrate language with other data modalities such as vision and action, on neuroscience research [25] [19]. While LLMs demonstrate remarkable predictive capabilities by identifying latent patterns in published literature, the path toward a deeper, human-like understanding of neuroscience likely requires embodied, multimodal systems that can ground linguistic symbols in sensory and interactive experiences [25] [32].

BrainBench: A Benchmark for Forward-Looking Prediction

Conceptual Framework and Design Rationale

Traditional benchmarks for evaluating AI in science, such as MMLU, PubMedQA, and MedMCQA, are predominantly backward-looking. They assess a model's capacity to retrieve and reason over established world knowledge [2]. In contrast, scientific progress is inherently forward-looking, reliant on generating and testing novel hypotheses. BrainBench was created to formalize this capability, testing whether an AI can integrate interrelated but often noisy findings to forecast new results [2] [33].

The core hypothesis is that LLMs, by training on vast swathes of the scientific literature, construct an internal statistical model that captures the fundamental patterning of methods and results in neuroscience. What might be dismissed as a "hallucination" in a fact-retrieval task could instead be a valid generalization or prediction in this forward-looking context [2]. BrainBench provides a controlled environment to quantify this predictive ability and compare it directly to human expertise.

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

The BrainBench evaluation protocol is structured as a forced-choice task centered on manipulated scientific abstracts [2] [34].

- Stimulus Creation: The test is built from genuine abstracts of recent neuroscience journal articles. For each original abstract, an altered version is programmatically generated. This altered version substantively changes the study's reported outcome while maintaining overall narrative coherence and linguistic plausibility.

- Task Formulation: Both LLMs and human experts are presented with the two versions of the abstract (original and altered). Their task is to identify which one represents the actual, published results.

- Performance Metric: The primary metric is accuracy—the percentage of correct identifications across a large set of test cases.

- Benchmark Scope: BrainBench encompasses 200 test cases spanning five major neuroscience subfields [2]:

- Behavioural/Cognitive

- Cellular/Molecular

- Systems/Circuits

- Neurobiology of Disease

- Development/Plasticity/Repair

This experimental design, summarized in the workflow below, tests the model's ability to discern a scientifically plausible outcome from an implausible one based on its integrated understanding of the field.

Quantitative Results: LLMs vs. Human Experts

The empirical findings from the BrainBench evaluation demonstrate a significant performance advantage of LLMs over human neuroscientists.

Table 1: Comparative Performance on BrainBench [2] [34]

| Participant Type | Average Accuracy | Number of Participants/Models | Key Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Neuroscience Experts | 63.4% | 171 | Screened for expertise; included doctoral students, postdocs, and faculty. |

| Top 20% of Human Experts | 66.2% | (Subset) | Accuracy for most expert humans on specific test items. |

| General-Purpose LLMs (Average) | 81.4% | 15 models | Included various versions of Falcon, Llama, Mistral, and Galactica. |

| BrainGPT (Neuroscience-Tuned LLM) | 86.0% | 1 | A Mistral-based model further tuned on neuroscience literature (2002-2022). |

Statistical analysis confirmed that the performance gap between LLMs and human experts was highly significant (t(14) = 25.8, p < 0.001, Cohen's d = 9.27) [2]. This indicates that the average LLM outperformed the average human expert by approximately 18 percentage points, a substantial margin.

Performance Across Neuroscience Subfields and Model Characteristics

LLMs consistently outperformed human experts across all five neuroscience subfields, with no single domain presenting a unique obstacle to model performance [2]. Furthermore, the study revealed several key insights into model architecture and performance:

- Model Size: Smaller models with 7 billion parameters (e.g., Llama2-7B, Mistral-7B) performed comparably to much larger models, suggesting a sufficiency of scale for this task.

- Model Type: Base LLMs generally outperformed their instruction-tuned or "chat-optimized" counterparts. This suggests that alignment for conversational flow may come at the cost of scientific inference capabilities.

- Domain-Specific Tuning: The superior performance of BrainGPT (86% accuracy) highlights the value of continued training on domain-specific literature, boosting performance beyond general-purpose models.

Mechanisms of LLM Prediction and Integration with Multimodal Systems

How LLMs Make Predictions: Beyond Memorization

A critical question is whether LLMs' success stems from genuine understanding or simple memorization of training data. Several lines of evidence from the BrainBench studies point to the former:

- Integration of Context: When LLMs were evaluated only on the isolated results sentences that differed between abstracts, their performance dropped significantly. This demonstrates that their predictive power derives from integrating information across the entire abstract, including background and methodological details, rather than relying on local cues [2].

- Resistance to Memorization: Analysis using the zlib-perplexity ratio—a measure that identifies memorized text—showed no signs that BrainBench test cases were part of the models' training data. For comparison, a known text like the Gettysburg Address showed clear signs of memorization in the same analysis [2].

Recent research from MIT provides a potential mechanistic explanation, suggesting that LLMs process diverse information through a centralized, semantic hub—analogous to the human brain's anterior temporal lobe. In this model, an English-dominant LLM converts inputs from various modalities (including other languages, code, and math) into abstract, English-like representations for reasoning before generating an output [35]. This allows for the integration of meaning across disparate data types.

The Multimodal Frontier: From Text Prediction to Grounded Understanding