Multimodal LLMs in Brain MRI: Benchmarking Performance, Methods, and Clinical Readiness for Sequence Classification

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) for brain MRI sequence classification, a critical task for automating medical imaging workflows.

Multimodal LLMs in Brain MRI: Benchmarking Performance, Methods, and Clinical Readiness for Sequence Classification

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) for brain MRI sequence classification, a critical task for automating medical imaging workflows. We explore the foundational principles of MLLMs in radiology, detail cutting-edge methodological architectures like mixture-of-experts and clinical visual instruction tuning, and investigate performance optimization and troubleshooting strategies to mitigate challenges such as hallucination. Through a validation and comparative lens, we benchmark leading models including ChatGPT-4o, Claude 4 Opus, and Gemini 2.5 Pro, synthesizing empirical evidence on their accuracy and limitations. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review outlines a roadmap for the safe and effective integration of MLLMs into biomedical research and clinical practice.

The Foundation of MLLMs in Radiology: Core Concepts and the Imperative for Brain MRI Classification

Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) represent a transformative evolution in artificial intelligence, engineered to process and synthesize information across diverse data types such as images, text, and clinical records. Within the specialized domain of medical imaging, and particularly for brain MRI analysis, these models demonstrate significant potential to augment diagnostic accuracy, streamline radiologist workflows, and enhance clinical decision-making. This guide provides an objective comparison of the current performance landscape of leading MLLMs in the critical task of brain MRI sequence classification, a fundamental capability upon which more complex diagnostic reasoning is built. Recent empirical evidence reveals a rapidly advancing field where models like ChatGPT-4o and Gemini 2.5 Pro show remarkable proficiency in basic image recognition tasks, yet a considerable performance gap persists when these models are compared to human radiologists in complex, integrative diagnostic scenarios [1] [2]. Furthermore, challenges such as model hallucinations and an inability to fully leverage multimodal context underscore the necessity of rigorous validation and expert oversight for any prospective clinical application [3] [4]. The following sections detail the experimental protocols, quantitative performance data, and essential research frameworks shaping this dynamic field.

Performance Comparison Tables

Core Classification Performance on Brain MRI Tasks

Table 1: Accuracy of MLLMs in Fundamental Brain MRI Recognition Tasks (n=130 images) [1] [5]

| Model | Modality Identification | Anatomical Region (Brain) | Imaging Plane | Contrast-Enhancement Status | MRI Sequence Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChatGPT-4o | 100% | 100% | 100% | 98.46% | 97.7% |

| Gemini 2.5 Pro | 100% | 100% | 100% | 98.46% | 93.1% |

| Claude 4 Opus | 100% | 100% | 99.23% | 95.38% | 73.1% |

Diagnostic Accuracy in Clinical-Style Evaluations

Table 2: MLLM vs. Radiologist Performance on Neuroradiology Differential Diagnosis [2]

| Group | Clinical Context (Text) Alone | Key Images Alone | Complete Case (Text + Images) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPT-4o | 34.0% | 3.8% | 35.2% |

| Gemini 1.5 Pro | 44.7% | 7.5% | 42.8% |

| Neuroradiologists | 16.4% | 42.0% | 50.3% |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

MRI Sequence Classification Protocol

A seminal study directly evaluating MLLMs on brain MRI sequence classification employed a rigorous, zero-shot prompting methodology [1] [5]. The experimental setup was as follows:

- Imaging Dataset: The study utilized 130 brain MRI images from adult patients without pathological findings. These represented 13 standard MRI sequences, including T1-weighted (T1w), T2-weighted (T2w), FLAIR (in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes), SWI, DWI, ADC, and contrast-enhanced T1w sequences.

- Model Input: Each model was provided with a single, high-resolution, anonymized JPEG image per trial, with no annotations or textual markings.

- Standardized Prompting: A consistent, zero-shot prompt in English was used for all model queries. The prompt explicitly stated the query was for research purposes and requested identification of the modality, anatomical region, imaging plane, contrast-enhancement status, and specific MRI sequence.

- Session Control: To prevent in-context learning from influencing results, a new chat session was initiated for every single image query, ensuring no conversation history was retained.

- Ground Truth and Analysis: Two radiologists independently reviewed and classified all model responses as "correct" or "incorrect" in consensus. Accuracy was calculated for each task, and statistical differences in sequence classification performance were analyzed using Cochran's Q test and pairwise McNemar tests with Bonferroni correction.

Human-AI Collaboration Workflow

A separate study investigated the real-world scenario of human-MLLM collaboration for brain MRI differential diagnosis [4]. Its protocol simulated a clinical support tool usage:

- Case Selection: Forty challenging brain MRI cases with definitive, confirmed diagnoses were selected.

- Study Design: Six radiology residents participated in a randomized, crossover study. Each evaluated 20 cases using a conventional internet search and 20 cases using an LLM-based search engine (PerplexityAI, powered by GPT-4).

- Task and Measurement: For each case, residents provided a ranked list of the three most likely differential diagnoses. The primary outcome was diagnostic accuracy, with interpretation time and confidence levels recorded as secondary measures.

- Log Analysis: All interactions with the LLM were logged and subsequently analyzed by a panel of radiologists to identify errors, such as user inaccuracies in describing image findings and LLM hallucinations.

MLLM Architecture for MRI Analysis

Key Findings and Clinical Implications

Performance Variations and Hallucinations

The comparative analysis of MLLMs reveals critical performance variations and operational risks. While models excel at foundational recognition tasks, their performance diverges significantly on more complex duties like specific sequence classification, with ChatGPT-4o (97.7%) and Gemini 2.5 Pro (93.1%) substantially outperforming Claude 4 Opus (73.1%) [1]. Misclassifications were not random; they followed patterns, such as the frequent confusion of FLAIR sequences with T1-weighted or diffusion-weighted sequences [5]. A paramount finding across studies is the occurrence of hallucinations—where models generate factually incorrect or irrelevant information. For instance, Gemini 2.5 Pro sometimes produced hallucinations involving unrelated clinical details like "hypoglycemia" and "Susac syndrome" [1] [5]. Another critical limitation is that, unlike radiologists, MLLMs such as GPT-4o and Gemini 1.5 Pro showed no statistically significant improvement in diagnostic accuracy when integrating multimodal information (text and images) compared to using text context alone [2]. This indicates they primarily rely on clinical text for diagnosis rather than effectively synthesizing visual findings.

The Promise of Human-AI Collaboration

Despite their standalone limitations, MLLMs demonstrate substantial value as collaborative tools. In a controlled study, radiology residents using an LLM-based search engine achieved significantly higher diagnostic accuracy (61.4%) compared to using conventional internet searches (46.5%) [4]. Furthermore, when neuroradiologists were provided with diagnostic suggestions from Gemini 1.5 Pro, their accuracy improved significantly from 47.2% to 56.0% [2]. This underscores a central theme in current research: the optimal path forward likely involves human-AI collaboration, where the clinician's expertise is augmented, not replaced, by the model's capabilities. Effective collaboration, however, requires users to navigate challenges such as inaccurate case descriptions in prompts and insufficient contextualization of LLM responses [4].

Table 3: Essential Resources for MLLM Research in Brain MRI Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Field |

|---|---|---|---|

| OmniBrainBench [6] | Benchmark Dataset | Evaluates MLLMs across full clinical workflow on brain imaging. | Provides a comprehensive benchmark covering 15 modalities and 15 clinical tasks, enabling robust model comparison. |

| 3D-BrainCT Dataset [7] | Dataset | Large-scale collection of 3D brain CT scans with paired text reports. | Supports training and evaluation of MLLMs on volumetric medical data, addressing a key limitation of 2D image analysis. |

| FORTE (Feature-Oriented Radiology Task Evaluation) [7] | Evaluation Metric | Gauges clinical essence of generated reports by extracting key radiological keywords. | Moves beyond traditional NLP metrics to assess the clinical utility and information density of MLLM-generated reports. |

| MMRQA Framework [8] | Evaluation Framework | Integrates signal metrics (SNR, CNR) with MLLMs for MRI quality assessment. | Bridges quantitative signal processing with semantic reasoning, enhancing interpretability for technical quality control. |

| CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training) [3] | Pre-trained Model | Aligns visual and textual data into a shared representational space. | Serves as a foundational vision encoder and alignment model for many custom medical MLLM architectures. |

| LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) [3] [8] | Fine-Tuning Method | Efficiently adapts large pre-trained models to new tasks with minimal parameters. | Enables parameter-efficient fine-tuning of MLLMs for specialized medical tasks, reducing computational costs. |

MRI Sequence Classification Workflow

The Clinical Significance of Accurate Brain MRI Sequence Identification

In the visually intensive discipline of radiology, multimodal Large Language Models (LLMs) represent a significant advancement with the potential to enhance diagnostic workflows [9]. However, the foundational competence of any model tasked with analyzing medical images lies in its ability to first recognize basic image characteristics, such as the specific Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) sequence used [9]. Accurate MRI sequence identification is a critical prerequisite for downstream clinical decision-making, automated image analysis, and large-scale research data curation. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the performance of emerging multimodal LLMs against established deep learning methods in classifying brain MRI sequences, presenting objective experimental data to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Performance Comparison of Classification Models

The ability to automatically and accurately identify MRI sequences is crucial for handling the vast, heterogeneous imaging data generated in multicenter clinical trials and routine care. The table below summarizes the performance of various AI models on this task.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI Models on Brain MRI Sequence Classification

| Model Type | Specific Model | Overall Accuracy | Key Strengths | Notable Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multimodal LLM | ChatGPT-4o [9] | 97.7% (127/130) | High accuracy in plane identification (100%) and contrast-status (98.46%) | - |

| Multimodal LLM | Gemini 2.5 Pro [9] | 93.1% (121/130) | Excellent contrast-status identification (98.46%) | Occasional hallucinations (e.g., irrelevant clinical details) |

| Multimodal LLM | Claude 4 Opus [9] | 73.1% (95/130) | - | Lower accuracy, particularly on SWI and ADC sequences |

| CNN | ResNet-18 (HD-SEQ-ID) [10] | 97.9% | High accuracy across vendors/scanners; robust in multicenter settings | Lower accuracy for SWI (84.2%) |

| CNN-Transformer Hybrid | MedViT [11] | 89.3% - 90.5%* | Superior handling of domain shift (e.g., adult to pediatric data) | - |

| GPT-4 based LLM | GPT-4 Classifier [12] | 83.0% (0.83) | High interpretability of decisions | Lower accuracy than specialized CNNs |

Note: Accuracy improved from 89.3% to 90.5% with expert domain knowledge adjustments [11].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To critically evaluate the data presented, an understanding of the underlying experimental methodologies is essential. The following sections detail the protocols from key cited studies.

Multimodal LLM Evaluation Protocol

A 2025 comparative analysis evaluated three advanced multimodal LLMs using a standardized zero-shot prompting approach [9].

- Dataset: 130 brain MRI images from adult patients without pathological findings, representing 13 standard MRI series (including T1w, T2w, FLAIR, SWI, DWI, ADC, and contrast-enhanced variants). Images were exported in high-quality JPEG format without annotations [9].

- Prompting: A standardized English prompt was used for each model in a new session to prevent in-context adaptation. The prompt asked the model to identify the modality, anatomical region, imaging plane, contrast-enhancement status, and specific MRI sequence [9].

- Evaluation: Responses were independently reviewed by two radiologists and classified as "correct" or "incorrect." Accuracy was calculated for each task, with MRI sequence classification as the primary outcome. Statistical differences were analyzed using Cochran's Q test and McNemar test with Bonferroni correction [9].

Deep Learning Model Training Protocol

Multiple studies have developed and validated specialized deep learning models for sequence classification, often using large-scale, heterogeneous datasets to ensure generalizability.

- Dataset (HD-SEQ-ID): A retrospective, multicentric dataset of 63,327 MRI sequences from 2179 glioblastoma patients across 249 hospitals and 29 scanner types was used to train a ResNet-18 based CNN. The model was designed to differentiate nine sequence types, including T1, T2, FLAIR, post-contrast T1, SWI, ADC, DWI with low and high b-values, and a T2*/DSC-related class [10].

- Preprocessing & Training: 2D midsection images from each sequence were allocated using a stratified split to ensure balanced groups across institutions, patients, and sequence types. The training data (~80% of the total) was further split into training and validation folds. The network was trained with data augmentation (Gaussian noise, intensity normalization) using the Adam optimizer and cross-entropy loss [10].

- Domain Shift Mitigation (MedViT): To address performance degradation due to domain shift (e.g., applying a model trained on adult data to pediatric scans), a hybrid CNN-Transformer model (MedViT) was evaluated. The study involved training the model on an adult MRI dataset and testing it on a pediatric dataset, with and without expert domain knowledge adjustments to align the model's classification task with the target data characteristics [11].

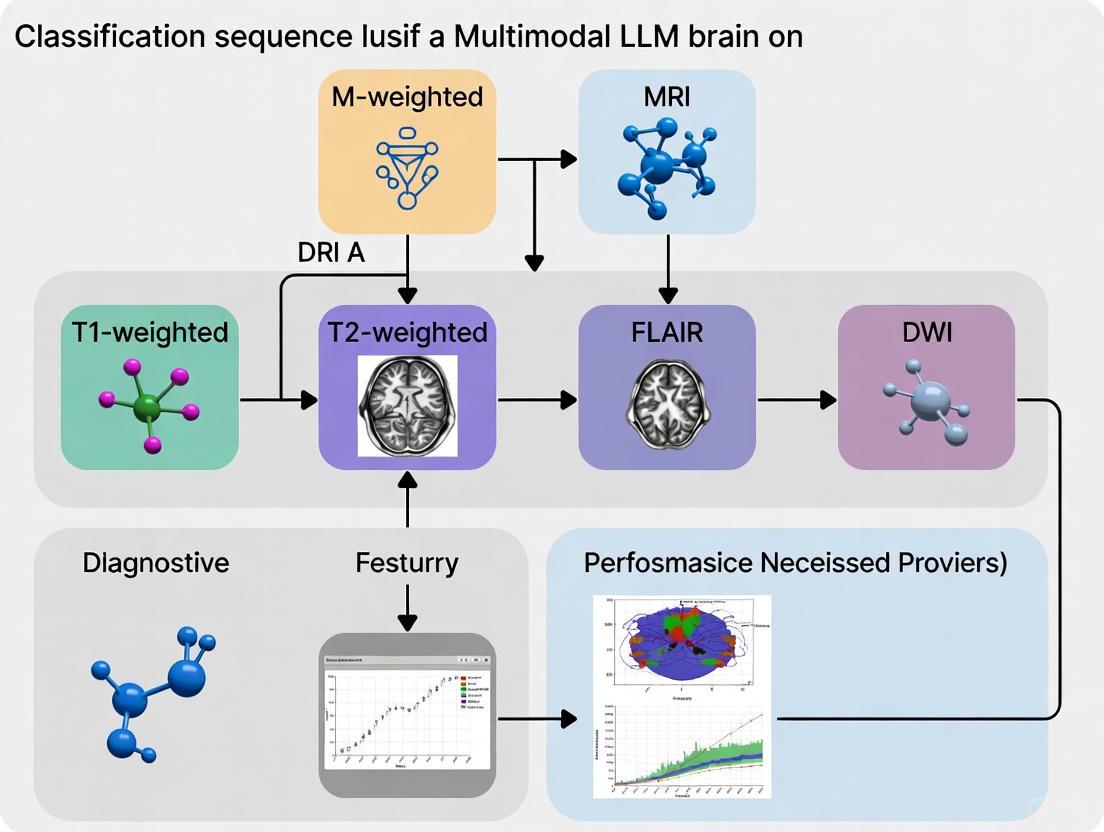

Figure 1: Experimental Workflows for MRI Sequence Classification. The workflows for evaluating Multimodal LLMs (top) and training specialized Deep Learning models (bottom) involve distinct processes tailored to their respective architectures and learning paradigms [9] [10].

Clinical Consequences of Misidentification

Inaccurate sequence classification is not merely a technical error; it has direct implications for clinical and research workflows.

- Hallucinations in LLMs: The Gemini 2.5 Pro model, while accurate, was noted to occasionally produce "hallucinations," generating irrelevant clinical details such as "hypoglycemia" and "Susac syndrome" that were not present in the input image or prompt context [9]. This underscores the need for careful validation and expert oversight before clinical integration.

- Specific Sequence Challenges: Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences were frequently misclassified as T1-weighted or diffusion-weighted sequences by LLMs. Furthermore, Claude 4 Opus demonstrated lower accuracy in classifying susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) sequences [9]. Similar challenges were observed in deep learning models, with the ResNet-18 model achieving its lowest accuracy (84.2%) on SWI sequences [10]. These specific weaknesses highlight areas requiring model improvement.

- Impact on Quantitative Workflows: The registration of longitudinal MRI data, essential for tracking tumor treatment, is highly influenced by the input sequences. Research shows that using contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1-CE) sequences yields the lowest registration errors, while using FLAIR sequences consistently produces the worst results [13]. Misidentifying a sequence could therefore lead to the selection of a suboptimal registration pathway, compromising the accuracy of longitudinal comparisons.

The Scientist's Toolkit

The following table details key computational tools and resources that facilitate research in automated MRI sequence classification.

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Automated MRI Sequence Classification

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| HD-SEQ-ID [10] | Pre-trained CNN (ResNet-18) | Provides a device- and sequence-independent model for high-accuracy classification of 9 MRI sequence types. | www.github.com/neuroAI-HD/HD-SEQ-ID |

| MedViT [11] | CNN-Transformer Hybrid Architecture | A modern neural network designed to be more robust to domain shift (e.g., between different patient populations or scanner types). | Code adaptation from original publication |

| MRISeqClassifier [14] | Deep Learning Toolkit | A toolkit tailored for smaller, unrefined MRI datasets, enabling precise sequence classification with limited data using multiple CNN architectures and ensemble methods. | www.github.com/JinqianPan/MRISeqClassifier |

The accurate identification of brain MRI sequences is a foundational step in automating and enhancing radiology workflows. Current evidence indicates that while general-purpose multimodal LLMs like ChatGPT-4o can achieve high accuracy, their performance is not yet universally superior to specialized deep learning models like the ResNet-18-based HD-SEQ-ID, which was trained on extensive, heterogeneous medical data. The choice between these approaches involves a trade-off between the flexibility and ease of use of LLMs and the potentially higher, more reliable accuracy of specialized models in a clinical context. Key challenges remain, including model hallucinations, specific weaknesses in classifying sequences like FLAIR and SWI, and the detrimental effects of domain shift. Future developments should focus on incorporating expert domain knowledge, improving model robustness across diverse datasets, and rigorous real-world validation to ensure that these technologies can be safely and effectively integrated into clinical and research pipelines.

In the rapidly evolving field of artificial intelligence, multimodal large language models (MLLMs) represent a significant leap forward, capable of processing and interpreting diverse data types such as text, images, and audio. Their application in specialized domains like medical imaging, particularly brain MRI sequence classification, holds immense promise for enhancing diagnostic accuracy and streamlining clinical workflows [15]. However, the integration of these advanced models into critical healthcare settings is hampered by three persistent and inherent challenges: data scarcity, immense computational demands, and the perilous risk of hallucinations. This guide objectively compares the performance of leading MLLMs in brain MRI research contexts, detailing the experimental protocols that reveal their capabilities and limitations.

Data Scarcity and Complexity in Medical Imaging

The development of robust MLLMs hinges on access to large-scale, high-quality, and accurately annotated multimodal datasets. This requirement is particularly acute in medical imaging, where data is often scarce, complex, and fraught with privacy concerns.

- Limited Annotated Data: Collecting aligned multimodal datasets, such as medical scans paired with expert annotations, is notoriously expensive and time-consuming [15]. This scarcity is even more pronounced for low-resource languages and specialized medical tasks, limiting the diversity and global applicability of the resulting models [16].

- Data Alignment Complexity: For a model to effectively understand the relationship between an MRI image and a textual diagnosis, the data must be meticulously aligned during training. This process requires a robust framework to connect visual and textual data, which is a non-trivial undertaking [16].

- Generalization Challenges: Models trained on limited or insufficiently diverse datasets struggle to generalize to real-world clinical scenarios, where patient demographics, imaging equipment, and protocols can vary widely. A 2025 study on brain tumor classification highlighted that such variability contributes to the difficulty in extracting meaningful features and limits model generalization [17].

Table 1: Data-Related Challenges in Multimodal LLMs for Medical Imaging

| Challenge | Impact on Model Performance | Exemplified in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Limited Annotated Medical Data | Reduces model accuracy and reliability; increases overfitting. | Scarcity of annotated CT/MRI datasets for brain tumors [17]. |

| Multimodal Data Alignment | Impairs model's ability to correlate images with correct textual descriptions (e.g., MRI sequences). | Need for unified training on image-caption pairs [16]. |

| Low-Resource Language Data | Creates bias towards high-resource languages (e.g., English), excluding global populations. | Underrepresentation of languages like Wolof, Amharic in AI training data [16]. |

Computational and Infrastructure Demands

The architectural complexity of MLLMs translates directly into massive computational requirements for both training and inference, posing a significant barrier to entry and scalability.

- Training Costs: Training MLLMs requires orders of magnitude more compute power than text-only models [15]. The integration of vision transformers (ViTs) with LLMs to create models that can "see and reason" is particularly resource-intensive [15].

- Inference Pipelines: Deploying these models in practical applications, such as a system where a user uploads an MRI scan and a question, requires unified pipelines for processing multi-input queries, which adds layers of computational complexity [15].

- Specialized Hardware: Running open-source MLLMs often necessitates high-performance computing clusters equipped with multiple high-end GPUs, such as NVIDIA H100s, to manage the computational load in a reasonable time frame [18].

The Persistent Peril of Hallucinations

Hallucinations—where models generate plausible but factually incorrect or unfaithful information—pose the most significant risk to the clinical adoption of MLLMs. In a medical context, these errors are not merely inconvenient; they can be dangerous [19] [18].

Experimental Evidence of Hallucination Risks

A comprehensive 2025 study in Communications Medicine exposed the profound vulnerability of LLMs to adversarial hallucination attacks in clinical decision support scenarios [18].

- Methodology: Researchers created 300 physician-validated clinical vignettes, each containing a single fabricated detail (e.g., a fictitious lab test, a made-up radiological sign, or an invented medical syndrome). These were presented to six different LLMs (both closed- and open-source) under various conditions: default settings, with a mitigating prompt, and with a temperature setting of 0 to minimize randomness.

- Results: The findings were stark. Hallucination rates across models ranged from 50% to 82%, meaning models elaborated on the planted false detail in a majority of cases. While a specialized mitigation prompt that instructed the model to use only clinically validated information reduced the overall hallucination rate from 66% to 44%, it failed to eliminate the risk. For the best-performing model, GPT-4o, the rate was reduced from 53% to 23%. Adjusting temperature settings offered no significant improvement [18].

This study underscores that even state-of-the-art models are highly susceptible to generating false clinical information, highlighting the critical need for expert oversight [18].

Hallucinations in Brain MRI Classification

Specialized evaluations on brain MRI data reveal that hallucination is not a uniform phenomenon and can manifest differently across models.

A 2025 comparative analysis evaluated three advanced MLLMs—ChatGPT-4o, Claude 4 Opus, and Gemini 2.5 Pro—on their ability to classify fundamental characteristics of 130 brain MRI images [9].

- Experimental Protocol: The models were tested in a zero-shot setting. Each was prompted to identify the imaging modality, anatomical region, imaging plane, contrast-enhancement status, and specific MRI sequence from high-quality JPEG images without any annotations. A new session was initiated for each query to prevent in-context adaptation [9].

- Performance Data: The results, summarized in Table 2 below, show that while basic recognition was flawless, performance varied significantly in the critical task of MRI sequence classification. Furthermore, Gemini 2.5 Pro exhibited "occasional hallucinations, including irrelevant clinical details such as 'hypoglycemia' and 'Susac syndrome,'" which were entirely unrelated to the input image [9].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Multimodal LLMs in Brain MRI Recognition Tasks (n=130 images) [9]

| Model | Modality Identification Accuracy | Anatomical Region Accuracy | Imaging Plane Classification Accuracy | Contrast-Enhancement Status Accuracy | MRI Sequence Classification Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChatGPT-4o | 100% | 100% | 100% | 98.46% | 97.69% |

| Claude 4 Opus | 100% | 100% | 99.23% | 95.38% | 73.08% |

| Gemini 2.5 Pro | 100% | 100% | 100% | 98.46% | 93.08% |

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow used in this comparative study, highlighting the standardized process for evaluating model performance and the points where errors like hallucinations can occur.

Underlying Causes and Emerging Mitigations

Understanding the root causes of hallucinations is key to developing effective countermeasures. Recent research has moved beyond attributing hallucinations solely to noisy data or architectural quirks, reframing them as a systemic incentive problem [19].

- Incentivized Guessing: The next-token prediction objective and common benchmarking leaderboards often reward models for producing confident, fluent text over carefully calibrated but uncertain responses. This trains models to "bluff" rather than admit uncertainty [19].

- Cross-Modal Confusion: In multimodal settings, the model may incorrectly infer relationships between an image and text, leading to unfaithful descriptions [9] [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key resources and methodologies employed in the cited research to evaluate and mitigate these inherent challenges.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Methods for MLLM Evaluation in Medical Imaging

| Research Reagent / Method | Function & Explanation | Exemplar Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Physician-Validated Clinical Vignettes | Provides a ground-truthed, clinically relevant benchmark for testing model reasoning and susceptibility to fabrication. | Used to test adversarial hallucination attacks with fabricated medical details [18]. |

| Zero-Shot Prompting | Evaluates the model's inherent capability without task-specific fine-tuning, testing its generalizability. | Used to prompt MLLMs with standardized questions about MRI images [9]. |

| Mitigation Prompts | A prompt-based strategy instructing the model to use only validated information and acknowledge uncertainty. | Reduced hallucination rate in GPT-4o from 53% to 23% [18]. |

| Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) | Augments model prompts with information retrieved from authoritative, external knowledge bases to ground responses in fact. | Cited as a promising mitigation strategy when combined with span-level verification [19]. |

| Adversarial Hallucination Attack Framework | A testing methodology where deliberate fabrications are embedded in prompts to systematically probe model weaknesses. | Framework used to quantify how often LLMs elaborate on false clinical details [18]. |

The diagram below outlines the core incentive-driven mechanism that leads to model hallucinations and the primary mitigation strategies being explored.

The journey to integrate multimodal LLMs into reliable brain MRI classification tools is well underway, with models like ChatGPT-4o and Gemini 2.5 Pro demonstrating impressive accuracy. However, this analysis confirms that the inherent challenges of data scarcity, computational demands, and hallucination risks remain formidable. The experimental data reveals that even the most advanced models are prone to generating fabricated information, especially when prompted with subtle inaccuracies. Therefore, the path forward requires a multi-faceted approach: continued development of diverse and representative medical datasets, investment in computational efficiency, and a fundamental shift in model training towards rewarding calibrated uncertainty rather than confident guessing. For researchers and clinicians, this underscores the non-negotiable need for rigorous, independent validation and expert human oversight when applying these powerful tools to patient care.

Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) represent a transformative advancement in artificial intelligence, engineered to process and interpret heterogeneous data types including images, text, and audio within a unified architectural framework. In the specialized domain of brain MRI analysis, MLLMs deploy a sophisticated tripartite architecture: a vision encoder that processes medical images to extract salient visual features, a multimodal connector that creates a shared representational space aligning visual features with linguistic concepts, and a pre-trained Large Language Model (LLM) that serves as the cognitive engine, reasoning about the aligned representations to generate clinically-relevant insights [20] [7]. The application of this architecture to brain MRI sequence classification represents a critical research frontier, offering the potential to augment diagnostic accuracy, standardize interpretation, and streamline radiologist workflows [9] [21].

This guide provides a systematic comparison of core MLLM architectures, focusing on their performance in brain MRI sequence classification—a fundamental task that underpins more complex diagnostic procedures. We synthesize recent experimental evidence, delineate methodological protocols, and contextualize findings within the broader landscape of biomedical artificial intelligence research, aiming to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the analytical framework necessary to evaluate and deploy these technologies in clinical and research settings.

Core Architectural Components of MLLMs

The operational efficacy of any MLLM in medical imaging hinges on the seamless integration of its three fundamental components, each fulfilling a distinct and critical role in the analytical pipeline.

Vision Encoders: From Pixels to Semantic Features

Vision encoders function as the perceptual front-end of the MLLM, transforming raw image pixels into structured, high-dimensional feature representations. In brain MRI analysis, common vision encoders are based on Vision Transformer (ViT) architectures, which process images by dividing them into patches, flattening them, and applying self-attention mechanisms to capture both local features and global contextual relationships [22] [23]. Alternative approaches may utilize Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), such as ResNet, which excel at capturing hierarchical local features through convolutional operations [24]. For 3D medical volumes like complete MRI scans, specialized 3D convolutional networks or vision transformers adapted for volumetric data are employed to capture spatial relationships across slices [7]. The choice of vision encoder directly impacts the model's ability to discern subtle anatomical variations and pathological signatures present in different MRI sequences.

Multimodal Connectors: Bridging Visual and Linguistic Semantics

The multimodal connector is the architectural linchpin that projects the high-dimensional output of the vision encoder into the embedding space of the pre-trained LLM. This component is typically a lightweight neural network, such as a multi-layer perceptron (MLP), which performs feature dimension alignment and transformation [20]. Advanced connector designs, such as those incorporating cross-attention mechanisms, enable dynamic, feature-specific interaction between visual and linguistic tokens, allowing the model to learn fine-grained alignments—for instance, between a specific image patch showing a tumor and the textual concept "glioma" [25]. The design of this connector is a primary differentiator among MLLMs and is critical for minimizing semantic loss during the transition from visual to textual domain.

Pre-trained LLMs: The Cognitive Engine for Reasoning and Reporting

The pre-trained LLM serves as the core cognitive engine, processing the aligned visual-language embeddings to perform the final reasoning and generate coherent textual output. Models such as GPT-4, Claude, and Gemini provide a powerful foundational knowledge base and syntactic capabilities [9] [26]. In medical applications, these general-purpose LLMs are often subjected to further domain-specific fine-tuning—a process referred to as Clinical Visual Instruction Tuning (CVIT)—to adapt them for clinical reporting conventions and terminology [7]. This component leverages its pre-existing world knowledge and reasoning capabilities, now grounded in the visual context, to perform tasks such as sequence classification, differential diagnosis, and radiology report generation.

Table 1: Core Architectural Components of Representative MLLMs

| Model Name | Vision Encoder | Multimodal Connector | Pre-trained LLM (Cognitive Engine) | Key Architectural Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BrainGPT [7] | Vision Transformer for 3D CT | MLP with Clinical Visual Instruction Tuning (CVIT) | Otter model, fine-tuned | Anatomy-aware fine-tuning for 3D volumetric data |

| GPT-4o [9] | Proprietary Vision Encoder | Proprietary connector | GPT-4 | General-purpose multimodal integration |

| Gemini 2.5 Pro [9] [20] | ViT-based | Projection layer, possibly with cross-attention | Gemini LLM | Advanced multimodal reasoning, hybrid architecture |

| Qwen 2.5 VL [20] | Vision Transformer (ViT) | Designed for efficient alignment | Qwen LLM | Optimized for visual question answering and reasoning |

| MultiViT [25] | 3D ViT for sMRI, 2D CNN for FNC | Cross-attention layers | Custom architecture for classification | Fuses structural (sMRI) and functional (fMRI) data |

Performance Comparison in Brain MRI Sequence Classification

Recent benchmarking studies have quantitatively evaluated the proficiency of various MLLMs in the fundamental task of identifying MRI sequences, a critical prerequisite for accurate pathological diagnosis.

A pivotal 2025 study directly compared the performance of three advanced MLLMs—ChatGPT-4o, Claude 4 Opus, and Gemini 2.5 Pro—on a brain MRI sequence classification task involving 130 images across 13 standard series [9]. The experimental protocol required models to identify the sequence in a zero-shot setting, meaning they were not specifically fine-tuned on the test dataset. The results demonstrated a significant performance differential, with ChatGPT-4o achieving the highest accuracy of 97.7%, followed by Gemini 2.5 Pro at 93.1%, and Claude 4 Opus at 73.1% [9]. These findings indicate that while some MLLMs possess a remarkable capacity for medical image interpretation, performance is not uniform across models.

A detailed analysis of error patterns revealed specific challenges. Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences were frequently misclassified as T1-weighted or diffusion-weighted sequences, suggesting potential difficulties in distinguishing fluid suppression signatures [9]. Furthermore, Claude 4 Opus exhibited lower accuracy on more specialized sequences like susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps [9]. Notably, the study also reported instances of "hallucination" in Gemini 2.5 Pro's outputs, where the model generated irrelevant clinical details not present in the image, such as mentions of "hypoglycemia" and "Susac syndrome" [9]. This underscores a critical challenge for clinical deployment, where diagnostic reliability is paramount.

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Brain MRI Sequence Classification [9]

| Model | Sequence Classification Accuracy | Contrast-Enhancement Status Accuracy | Imaging Plane Classification Accuracy | Common Misclassifications & Hallucinations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChatGPT-4o | 127/130 (97.7%) | 128/130 (98.46%) | 130/130 (100%) | FLAIR sequences misclassified as T1 or DWI |

| Gemini 2.5 Pro | 121/130 (93.1%) | 128/130 (98.46%) | 130/130 (100%) | Occasional hallucinations (e.g., "hypoglycemia") |

| Claude 4 Opus | 95/130 (73.1%) | 124/130 (95.38%) | 129/130 (99.23%) | Lower accuracy on SWI and ADC sequences |

Experimental Protocols and Evaluation Methodologies

Robust experimental design is essential for the valid assessment of MLLM performance in medical imaging tasks. The following section outlines the standard protocols and emerging evaluation frameworks used in the field.

Data Curation and Preprocessing

The foundation of any reliable experiment is a high-quality, well-annotated dataset. Research in this domain often utilizes publicly available brain MRI datasets (e.g., BraTS for tumors) or carefully curated institutional datasets [22] [7]. A typical preprocessing pipeline involves several critical steps: anonymization to remove protected health information, conversion to a standardized format (e.g., JPEG for 2D slices, NIfTI for 3D volumes), and resolution standardization [9]. For 3D model training, this may also include co-registration of multi-sequence scans to a common anatomical space and intensity normalization to account for scanner-specific variations [25] [7]. In the study comparing ChatGPT-4o, Gemini, and Claude, images were exported in high-quality JPEG format (minimum resolution 994×1382 pixels) without compression or annotations to ensure a clean input signal [9].

Model Fine-Tuning and Specialized Training

While general-purpose MLLMs show promise, optimal performance in clinical tasks often requires domain adaptation. Clinical Visual Instruction Tuning (CVIT) is an advanced fine-tuning paradigm that incorporates clinical knowledge into the model. As implemented in the BrainGPT model for 3D CT reporting, CVIT can take several forms, including the use of structured clinical templates and keyword-focused guidelines that direct the model's attention to diagnostically salient features [7]. Another approach involves hybrid architecture fine-tuning, where models like TransXAI combine CNNs for local feature extraction with vision transformers to capture long-range dependencies in MRI data, enhancing segmentation and classification accuracy [23].

Evaluation Metrics Beyond Traditional NLP

The unique requirements of medical reporting necessitate evaluation metrics that go beyond those used for general natural language processing. Traditional metrics like BLEU and ROUGE, which measure n-gram overlap with reference reports, often fail to capture clinical accuracy and completeness [7]. In response, researchers have developed task-specific evaluation frameworks. The Feature-Oriented Radiology Task Evaluation (FORTE) is one such framework designed to gauge the clinical essence of generated reports by extracting and scoring keywords across four essential components: degree, landmark, feature, and impression [7]. This provides a more nuanced assessment of a model's diagnostic utility than traditional metrics.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for evaluating MLLM performance in brain MRI analysis, incorporating both traditional and clinical metrics.

The development and validation of MLLMs for brain MRI analysis require a curated set of data, computational tools, and evaluation frameworks. The following table details key resources that constitute the essential toolkit for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for MLLM Development in Brain MRI Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Research | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Brain MRI Datasets | BraTS [22] [23], Brain Tumor MRI Dataset [24] | Model training and benchmarking for segmentation and classification tasks | Multi-institutional, annotated, multi-modal MRI (T1, T1Gd, T2, FLAIR) |

| 3D Volumetric Datasets | 3D-BrainCT [7], OASIS [25] | Training and evaluation for 3D model architectures | Volumetric scans with corresponding textual reports or diagnoses |

| Pre-trained Vision Encoders | Vision Transformer (ViT) [22] [20], ResNet50 [24], SigLIP-L [20] | Extracting visual features from 2D/3D medical images | Pre-trained on large-scale image datasets (e.g., ImageNet) |

| Pre-trained LLMs | GPT-4/4o [9] [26], Claude, Gemini, LLaMA [26] | Serving as the cognitive engine for language understanding and generation | Contains billions of parameters, strong zero-shot reasoning capability |

| Multimodal Fusion Architectures | Cross-attention layers [25], MLP projectors [20] | Aligning visual features with language embeddings | Can be simple (linear layers) or complex (cross-modal attention) |

| Evaluation Frameworks | FORTE [7], Turing-style expert review [9] [7] | Assessing clinical relevance and accuracy of model outputs | Moves beyond traditional NLP metrics to focus on clinical utility |

The systematic evaluation of core MLLM architectures reveals a rapidly evolving landscape with significant potential to transform brain MRI analysis. Current evidence indicates that tripartite architecture—vision encoder, multimodal connector, and cognitive LLM—is highly effective, with models like ChatGPT-4o demonstrating remarkable proficiency (97.7% accuracy) in fundamental tasks like sequence classification [9]. However, performance variability, susceptibility to hallucination, and the limitations of traditional evaluation metrics highlight that these systems are currently augmentative rather than substitutive for clinical expertise.

Future research must prioritize several critical directions: First, the development of standardized, multi-institutional 3D MRI datasets with high-quality annotations is essential for robust training and validation [21] [7]. Second, advancing explainability (XAI) frameworks is crucial for clinical adoption, enabling radiologists to understand the reasoning behind model predictions and build trust in AI-assisted diagnostics [23]. Finally, creating specialized, clinically-validated evaluation metrics like FORTE that move beyond linguistic similarity to measure diagnostic fidelity and clinical actionability will be fundamental for translating technical progress into genuine improvements in patient care [7]. As these architectural components continue to mature and integrate more deeply with clinical workflows, MLLMs are poised to become indispensable collaborators in the pursuit of precision neurology and oncology.

Architectures and Applications: How MLLMs are Engineered for Brain MRI Analysis

The application of Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) to 3D medical imaging represents a transformative frontier in medical AI. This guide objectively compares two pioneering architectures—BrainGPT for 3D brain CT report generation and mpLLM for Visual Question Answering (VQA) on multiparametric 3D brain MRI. Framed within broader research on brain MRI sequence classification, this analysis covers their architectural philosophies, experimental performance, and suitability for specific clinical research tasks. Performance data indicates that BrainGPT achieves a Turing test pass rate of 74% and a feature-oriented radiology task evaluation score of 0.71, while mpLLM outperforms baseline models by 5.3% on VQA tasks [7] [27].

BrainGPT: A Holistic Framework for 3D CT Report Generation

BrainGPT is designed to address the critical challenge of generating diagnostically relevant reports from volumetric 3D brain CT scans [7]. Its development involved a comprehensive framework encompassing dataset curation, model fine-tuning, and the creation of a novel evaluation metric.

- Architecture Foundation: Built upon the open-source Otter model, which itself is based on the OpenFlamingo architecture [28]. The model incorporates a CLIP ViT-L/14 visual encoder, a Perceiver Resampler, and an LLaMA-7B language model as its core components [28].

- Clinical Visual Instruction Tuning (CVIT): A key innovation in BrainGPT's training is the use of CVIT, which enhances the model's medical domain knowledge. This includes "keyword instruction," guiding the model to structure reports around specific radiological concepts like Degree, Landmark, Feature, and Impression [7] [28].

- FORTE Evaluation Metric: The authors identified that traditional Natural Language Processing (NLP) metrics were insufficient for evaluating clinical report quality. They developed the Feature-Oriented Radiology Task Evaluation (FORTE), a structured keyword extraction method that assesses the clinical essence of generated reports [7].

mpLLM: A Mixture-of-Experts for Multiparametric MRI VQA

The mpLLM model is engineered to tackle the complexities of Visual Question Answering (VQA) involving multiple, interrelated 3D MRI modalities, a common scenario in clinical practice for diagnosing brain tumors and other intracranial lesions [27].

- Prompt-Conditioned Hierarchical Mixture-of-Experts (MoE): This is the core architectural innovation of mpLLM. It efficiently fuses multiple 3D modalities by routing information through modality-level and token-level projection experts based on the input question. This design dramatically reduces the computational burden compared to simply concatenating vision tokens from all modalities [27] [29].

- Efficient Training without Massive Paired Data: A significant advantage of mpLLM is that it does not require pre-training on large-scale image-report datasets, which are often scarce in medicine. Instead, it can be trained end-to-end on a VQA dataset [27].

- Synthetic VQA Protocol: To overcome the lack of annotated VQA data for 3D brain mpMRI, mpLLM integrates a synthetic data generation protocol that derives medically relevant questions from existing segmentation annotations, which are then clinically validated by medical experts [27].

Table 1: Core Architectural Comparison of BrainGPT and mpLLM

| Feature | BrainGPT | mpLLM |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Task | Automated Report Generation (RRG) [7] | Visual Question Answering (VQA) [27] |

| Imaging Modality | 3D Brain Computed Tomography (CT) [7] | Multiparametric 3D Brain MRI (mpMRI) [27] |

| Core Technical Innovation | Clinical Visual Instruction Tuning (CVIT) [7] | Prompt-Conditioned Hierarchical Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) [27] |

| Data Strategy | Curation of a large-scale dataset (3D-BrainCT: 18,885 text-scan pairs) [7] | Synthetic VQA generation from segmentation masks [27] |

| Key Evaluation Metric | FORTE (Feature-Oriented Radiology Task Evaluation) [7] | Accuracy on expert-validated VQA tasks [27] |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Benchmarking

BrainGPT Experimental Setup and Results

Protocol:

- Dataset: The model was trained and evaluated on the in-house 3D-BrainCT dataset containing 18,885 text-scan pairs [7].

- Fine-Tuning: Four variants of BrainGPT were created by applying different levels of Visual Instruction Tuning (VIT) to the base Otter model: Regular VIT (Plain and In-context Example instructions) and Clinical VIT (Template and Keyword instructions) [7] [28].

- Evaluation: Generated reports were evaluated using both traditional NLP metrics (e.g., BLEU, CIDEr) and the novel FORTE metric. A critical post-processing step of sentence pairing was applied to improve metric alignment. A Turing-like test with 11 physician raters was conducted to assess the clinical indistinguishability of the reports [7].

Performance:

- FORTE Score: The BrainGPT model achieved an average FORTE F1-score of 0.71, with sub-scores for Impression (0.779) and Landmark (0.706) being particularly strong [7].

- Turing Test: In a blinded evaluation, 74% of reports generated by BrainGPT were deemed indistinguishable from those written by human radiologists [7].

- Traditional Metrics: After sentence pairing, the hierarchical improvement from RVIT to CVIT models was best captured by the CIDEr-R metric, which increased from 125.86 (BrainGPT-plain) to 153.3 (BrainGPT-keyword) [7] [28].

mpLLM Experimental Setup and Results

Protocol:

- Dataset: The model was evaluated on the first clinically validated VQA dataset for 3D brain mpMRI, created using its synthetic VQA protocol [27].

- Comparison Baselines: mpLLM was benchmarked against strong medical Vision-Language Model (VLM) baselines [27].

- Ablation Studies: The importance of its core components—modality-level and token-level experts, and prompt-conditioned routing—was validated through ablation experiments [27].

Performance:

- The mpLLM architecture outperformed strong medical VLM baselines by 5.3% on average across multiple mpMRI datasets [27].

Contextual Performance in MRI Sequence Classification

While not their primary function, the capabilities of general MLLMs on tasks like MRI sequence classification provide a useful baseline for understanding the domain's challenges. A recent study evaluated models like ChatGPT-4o, Claude 4 Opus, and Gemini 2.5 Pro on classifying 13 standard brain MRI series [9].

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking Across Tasks and Models

| Model / Task | Key Metric | Reported Score | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| BrainGPT (RRG) | FORTE (Avg. F1) | 0.71 [7] | Higher scores indicate better capture of clinical keywords. |

| BrainGPT (Turing Test) | Human Rater Accuracy | 74% [7] | Percentage of reports deemed human-like. |

| mpLLM (VQA) | Accuracy vs. Baselines | +5.3% [27] | Average improvement over other medical VLMs. |

| General MLLMs (Sequence ID) | |||

| ⋄ ChatGPT-4o | Classification Accuracy | 97.7% [9] | On a dataset of 130 brain MRI images. |

| ⋄ Gemini 2.5 Pro | Classification Accuracy | 93.1% [9] | Occasional hallucinations noted [9]. |

| ⋄ Claude 4 Opus | Classification Accuracy | 73.1% [9] | Struggled with SWI and ADC sequences [9]. |

Visualizing Architectures and Workflows

BrainGPT Clinical Fine-Tuning and Evaluation Workflow

mpLLM Mixture-of-Experts Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

For researchers aiming to work in this domain, the following tools and datasets featured in the evaluated models are critical.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D-BrainCT Dataset [7] | Proprietary Dataset | Provides text-scan pairs for training and evaluating 3D CT report generation models. | Training BrainGPT models [7]. |

| FORTE Metric [7] | Evaluation Metric | Gauges clinical relevance of generated reports by extracting structured keywords (Degree, Landmark, Feature, Impression). | Evaluating diagnostic quality beyond text similarity [7]. |

| Synthetic VQA Protocol [27] | Data Generation Method | Generates medically valid Visual Q&A pairs from segmentation annotations, mitigating data scarcity. | Creating training data for mpLLM without manual VQA annotation [27]. |

| Clinical Visual Instruction Tuning [7] | Training Methodology | Enhances model's clinical reasoning by incorporating structured templates and keyword guidelines during fine-tuning. | Steering BrainGPT to generate clinically sensible reports [7] [28]. |

| Hierarchical MoE Architecture [27] | Model Architecture | Enables parameter-efficient fusion of multiple, interrelated 3D image modalities for joint reasoning. | Allowing mpLLM to process T1w, T2w, and FLAIR MRI sequences effectively [27]. |

| VQA-RAD & ROCOv2 [30] | Public Benchmark Datasets | Standardized datasets for evaluating model performance on medical Visual Question Answering and image captioning. | Benchmarking MLLM performance on clinical tasks [30]. |

The application of Large Language Models (LLMs) in specialized domains like healthcare requires moving beyond general-purpose capabilities to developing nuanced medical expertise. This transition is primarily achieved through three specialized training paradigms: pre-training on domain-specific corpora, instruction tuning to follow task-oriented prompts, and alignment to ensure outputs meet clinical standards. Within the specific context of multimodal LLM (MLLM) performance on brain MRI sequence classification—a critical task for diagnostic assistance and automated report generation—the choice of training strategy significantly impacts model accuracy, reliability, and clinical utility. These paradigms enable the transformation of general foundation models into specialized tools that can interpret complex medical images, classify intricate MRI sequences, and generate clinically coherent radiology reports, thereby addressing one of the most visually and diagnostically challenging tasks in modern radiology.

Comparative Analysis of Training Paradigms

The following table summarizes the core objectives, methodologies, and representative models for each of the three primary training paradigms in the medical domain.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Training Paradigms for Medical LLMs/MLLMs

| Training Paradigm | Primary Objective | Key Methodology | Representative Medical Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-training | To build foundational medical knowledge and representations from a broad, unlabeled corpus [31] [32]. | Self-supervised learning on large-scale biomedical text (e.g., clinical notes, literature) and images (e.g., X-rays, CTs) [31] [32]. | BioBERT, ClinicalBERT, BiomedGPT (base versions) [33] [32] |

| Instruction Tuning | To adapt models to follow instructions and perform diverse, specific tasks based on natural language prompts [33] [34]. | Supervised fine-tuning on datasets of (instruction, input, output) triplets covering tasks like NER, RE, and QA [33] [35]. | Llama2-MedTuned, Med-Alpaca, BiomedGPT (instruction-tuned) [33] [32] |

| Alignment | To refine model behavior to be helpful, safe, and adhere to clinical standards and constraints [7] [36]. | Human (or AI) feedback on generated outputs (e.g., RLHF), multi-agent review frameworks, and specialized evaluation metrics [7] [36]. | BrainGPT (CVIT), Medical AI Consensus framework [7] [36] |

Experimental Performance in Brain MRI Sequence Classification

Recent benchmarking studies provide quantitative data on the performance of differently trained models on the critical task of brain MRI sequence classification. The table below compares the accuracy of leading multimodal LLMs, highlighting the tangible outcomes of their underlying training approaches.

Table 2: Model Performance on Brain MRI Sequence Classification (n=130 images, 13 series) [9]

| Multimodal LLM | Modality Identification Accuracy | Anatomical Region Recognition Accuracy | Imaging Plane Classification Accuracy | Contrast-Enhancement Status Accuracy | MRI Sequence Classification Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChatGPT-4o | 100% | 100% | 100% | 98.46% | 97.69% |

| Gemini 2.5 Pro | 100% | 100% | 100% | 98.46% | 93.08% |

| Claude 4 Opus | 100% | 100% | 99.23% | 95.38% | 73.08% |

Statistical analysis using Cochran's Q test revealed that the differences in MRI sequence classification accuracy were statistically significant (p < 0.001), underscoring the variable efficacy of different model architectures and training strategies [9]. The most frequent misclassifications involved Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences, often confused with T1-weighted or diffusion-weighted sequences. Furthermore, Gemini 2.5 Pro exhibited occasional "hallucinations," generating irrelevant clinical details such as "hypoglycemia" and "Susac syndrome," a critical failure mode for clinical deployment [9].

Impact of Specialized Instruction Tuning

Specialized instruction tuning demonstrably enhances model performance on clinical tasks. The Llama2-MedTuned models, instruction-tuned on approximately 200,000 biomedical samples, showed potential to achieve results on par with specialized encoder-only models like BioBERT and BioClinicalBERT for classical biomedical NLP tasks such as Named Entity Recognition (NER) and Relation Extraction (RE) [33]. In radiology report generation, the Clinically Visual Instruction Tuned (CVIT) BrainGPT model, trained on the 3D-BrainCT dataset, achieved an average Feature-Oriented Radiology Task Evaluation (FORTE) F1-score of 0.71. In a Turing-like test, 74% of its generated reports were indistinguishable from human-written ground truth [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Instruction Tuning for Biomedical NLP

The development of Llama2-MedTuned provides a template for effective instruction tuning [33].

- Dataset Curation: A comprehensive instruction dataset of ~200,000 samples was assembled from diverse public biomedical datasets. This included data for Named Entity Recognition (NCBI-disease, BC5CDR), Relation Extraction (i2b2-2010, GAD), Natural Language Inference (MedNLI), Document Classification (HoC), and Question Answering (ChatDoctor, PMC-Llama).

- Prompt Template: A structured prompt format with three components was adopted: 1) Instruction: One of 5-10 randomly chosen task descriptions; 2) Input: The original text from the source dataset; 3) Output: The expected model response.

- Training Configuration: Models were fine-tuned using the Llama2 (7B and 13B) base models with a batch size of 10 per GPU and DeepSpeed Zero 3 optimization [33].

Protocol 2: Evaluating MLLMs on Brain MRI Classification

A rigorous protocol for evaluating multimodal LLMs on brain MRI classification tasks is detailed in recent comparative studies [9].

- Data Preparation: 130 brain MRI images from adult patients without pathological findings were selected, representing 10 single-slice images for each of 13 standard MRI series (e.g., Axial T1w, T2w, FLAIR, DWI, SWI, ADC, and contrast-enhanced variants). Images were exported in high-quality JPEG format without annotations.

- Prompting and Evaluation: A standardized, zero-shot English prompt was used for all models, asking them to identify the modality, anatomical region, imaging plane, contrast status, and specific MRI sequence. To prevent in-context adaptation, a new chat session was initiated for each query.

- Ground Truth and Analysis: Two radiologists independently reviewed and classified LLM responses as "correct" or "incorrect" in consensus. Accuracy was calculated for each task, and differences in sequence classification performance were analyzed using Cochran's Q test and pairwise McNemar tests with Bonferroni correction [9].

Protocol 3: Clinical Visual Instruction Tuning (CVIT) for Report Generation

The BrainGPT study established a advanced protocol for aligning models with clinical reasoning [7].

- Base Model and Data: The open-source Otter foundation model was used. It was fine-tuned on a curated dataset of 18,885 3D brain CT text-scan pairs.

- Fine-Tuning Conditions: Four distinct instruction-tuning strategies were compared:

- Plain Instruction: Basic role instruction (e.g., "You are a radiology assistant").

- In-Context Example Instruction: Plain instruction supplemented with 3-shot examples.

- Template Instruction: Incorporation of structured clinical QA templates.

- Keyword Instruction: Use of categorical guidelines focused on essential radiology keywords.

- Evaluation Metric - FORTE: A novel Feature-Oriented Radiology Task Evaluation metric was introduced to move beyond traditional NLP scores. FORTE extracts and evaluates four key components from radiology reports:

degree,landmark,feature, andimpression[7].

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Medical MLLM Specialization Pipeline

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end pipeline for transforming a general-purpose foundation model into a specialized medical MLLM.

Multi-Agent Framework for Evaluation and Alignment

For complex clinical tasks like radiology report generation, a multi-agent framework ensures rigorous evaluation and alignment, as depicted below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This section details key datasets, models, and evaluation tools essential for research and development in medical MLLMs for brain MRI analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Medical MLLM Development

| Category | Name | Description and Function |

|---|---|---|

| Datasets | 3D-BrainCT [7] | A curated dataset of 18,885 text-scan pairs of 3D brain CTs. Used for training and evaluating models on volumetric medical image interpretation. |

| Llama2-MedTuned-Instructions [33] | An instruction dataset of ~200,000 samples compiled from various biomedical tasks (NER, RE, NLI, QA). Used for instruction tuning general LLMs for medicine. | |

| Base Models | Llama2 (7B/13B) [33] | A powerful, open-source autoregressive language model. Serves as a common base model for subsequent medical instruction tuning. |

| Otter [7] | An open-source multimodal model. Used as the foundation for clinical visual instruction tuning in the BrainGPT study. | |

| Specialized Models | BiomedGPT-Large/XL [32] | Scaled-up vision-language models (472M/930M parameters). Demonstrate the impact of model scaling on performance across 6 multi-modal biomedical tasks. |

| BrainGPT [7] | A Clinically Visual Instruction Tuned (CVIT) model for 3D CT radiology report generation. Exemplifies the application of advanced instruction tuning. | |

| Evaluation Tools | FORTE [7] | Feature-Oriented Radiology Task Evaluation. A clinical essence metric that evaluates reports on degree, landmark, feature, and impression components. |

| HumanELY [37] | A standardized framework and web app for human evaluation of LLMs in healthcare, addressing metrics like accuracy, harm, and coherence. | |

| Multi-Agent Framework [36] | A benchmark environment with ten specialized agents (e.g., classifier, composer, evaluator) for rigorous radiology report generation and evaluation. |

Multimodal LLM Performance in Brain MRI Sequence Classification

Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) represent a transformative advancement in medical artificial intelligence, combining the reasoning capabilities of large language models with computer vision to interpret complex clinical data. In radiology, these models are increasingly applied to two critical tasks: Visual Question Answering (VQA), which allows interactive querying about image content, and Automated Radiology Report Generation (RRG), which produces preliminary diagnostic reports [3]. The analysis of brain MRI presents particular challenges due to the multiplicity of standard sequences (T1-weighted, T2-weighted, FLAIR, DWI, etc.), each providing complementary clinical information. Accurate sequence classification forms the foundational step toward more complex interpretation tasks, yet this capability varies significantly across current MLLM implementations [9]. This comparison guide examines the current state of MLLM performance specifically for brain MRI sequence classification and related tasks, providing researchers with objective performance data and methodological insights to inform their work.

Performance Comparison Tables

Brain MRI Sequence Classification Accuracy of General-Purpose MLLMs

Table 1: Performance of general-purpose MLLMs on brain MRI sequence classification tasks

| Model | Sequence Classification Accuracy | Contrast-Enhancement Status Accuracy | Imaging Plane Classification Accuracy | Notable Strengths | Common Errors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChatGPT-4o | 97.69% (127/130) [9] | 98.46% (128/130) [9] | 100% (130/130) [9] | Excellent sequence recognition, high reliability | Rare misclassification of FLAIR as T1-weighted or DWI |

| Gemini 2.5 Pro | 93.08% (121/130) [9] | 98.46% (128/130) [9] | 100% (130/130) [9] | Strong overall performance | Occasional hallucinations, adding irrelevant clinical details |

| Claude 4 Opus | 73.08% (95/130) [9] | 95.38% (124/130) [9] | 99.23% (129/130) [9] | Competent basic recognition | Struggles with SWI and ADC sequences, lower sequence accuracy |

Specialized Model Performance on 3D Brain MRI Tasks

Table 2: Performance of specialized medical MLLMs on 3D brain MRI tasks

| Model | Primary Task | Key Metric | Performance | Architecture | Clinical Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BrainGPT [7] | 3D CT Report Generation | FORTE F1-Score | 0.71 (average) [7] | Clinical Visual Instruction Tuning (CVIT) | 74% of reports indistinguishable from human in Turing test [7] |

| mpLLM [27] | 3D mpMRI VQA | Average Improvement | Outperforms baselines by 5.3% [27] | Prompt-conditioned hierarchical Mixture-of-Experts | Clinician-validated VQA dataset and model responses |

| MedVersa [38] | Radiology Report Generation | RadCliQ-v1 Score | 1.46 ± 0.03 on IU X-ray findings [38] | Multitask model | Not specified for brain MRI applications |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Brain MRI Sequence Classification Protocol

The comprehensive evaluation of general-purpose MLLMs for brain MRI sequence classification employed a rigorous methodology [9]. Researchers collected 130 brain MRI images from adult patients without pathological findings, representing 13 standard MRI series including axial T1-weighted, T2-weighted, FLAIR (axial, coronal, sagittal), SWI, DWI, ADC, and contrast-enhanced sequences across multiple planes. All images were exported in high-quality JPEG format (minimum resolution 994×1382 pixels) without compression, cropping, or annotations. The study utilized a zero-shot prompting approach with a standardized prompt that asked models to identify: (1) radiological modality, (2) anatomical region, (3) imaging plane, (4) contrast-enhancement status, and (5) specific MRI sequence. To prevent in-context adaptation, researchers initiated a new session for each prompt by clearing chat history. Two radiologists independently reviewed and classified responses as "correct" or "incorrect" through consensus, with hallucinations defined as statements unrelated to the input image or prompt context.

3D Medical Imaging Evaluation Metrics

Specialized models for 3D medical imaging employ tailored evaluation frameworks that address the limitations of traditional natural language processing metrics [7]. The Feature-Oriented Radiology Task Evaluation (FORTE) was specifically developed to capture clinical essence in generated reports by evaluating four essential keyword components: degree, landmark, feature, and impression [7]. This approach recognizes that traditional metrics like BLEU and ROUGE-L correlate poorly with radiologist evaluations [27]. FORTE employs structured keyword extraction that addresses multi-semantic context, recognizes synonyms, and transfers across modalities. Similarly, the S-Score metric evaluates structured reports by measuring both disease prediction accuracy and precision of disease-specific details, demonstrating stronger alignment with human assessments than traditional metrics [39].

Diagram 1: Brain MRI sequence classification experimental workflow. This protocol tests MLLM capability to identify fundamental image characteristics using zero-shot prompting and radiologist consensus validation [9].

Key Architectural Approaches

Specialized Architectures for 3D Medical Imaging

Medical MLLMs employ specialized architectures to address the unique challenges of 3D medical images. BrainGPT utilizes Clinical Visual Instruction Tuning (CVIT) to enhance medical domain knowledge, incorporating four fine-tuning conditions: plain instruction (describing the model's role as a radiology assistant), in-context example instruction (adding 3-shot examples), template instruction (using structured clinical QA templates), and keyword instruction (providing categorical guidelines focused on keywords) [7]. This hierarchical approach progressively enhances clinical sensibility in report generation.

The mpLLM architecture introduces a prompt-conditioned hierarchical Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) specifically designed for multiparametric 3D brain MRI [27]. This approach routes computation across modality-level and token-level projection experts to fuse multiple interrelated 3D modalities efficiently. Unlike modality-specific or modality-agnostic vision encoders, mpLLM's low-level components are lightweight projection functions that train end-to-end with the language model during fine-tuning, dramatically reducing GPU memory usage by processing a single fused vision token representation rather than multiple separate image tokens [27].

Diagram 2: Medical MLLM architecture overview showing standard components (black) and specialized medical adaptations (red). Medical MLLMs build upon general architectures but incorporate domain-specific enhancements like hierarchical MoE and clinical instruction tuning [27] [3].

Table 3: Key research reagents and resources for medical MLLM development

| Resource | Type | Key Features | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3D-BrainCT Dataset [7] | Dataset | 18,885 text-scan pairs of 3D brain CT | Training and evaluation of 3D report generation models |

| MIMIC-STRUC [39] | Structured Dataset | Chest X-ray with disease severity, location, probability | Structured radiology report generation development |

| FORTE [7] | Evaluation Framework | Feature-oriented radiology task evaluation | Clinical essence measurement in generated reports |

| S-Score [39] | Evaluation Metric | Measures disease prediction accuracy and detail precision | Structured report quality assessment |

| ReXGradient-160K [40] | Benchmark Dataset | 273,004 chest X-rays from 160,000 studies | Large-scale RRG and VQA benchmarking |

| Clinical Visual Instruction Tuning [7] | Training Methodology | Enhances medical domain knowledge | Specialized medical MLLM development |

| Hierarchical MoE Architecture [27] | Model Architecture | Efficient fusion of multiple 3D modalities | Multiparametric MRI analysis |

Current MLLMs demonstrate varying capabilities in brain MRI sequence classification and related tasks. General-purpose models like ChatGPT-4o achieve remarkably high accuracy (97.69%) in basic sequence recognition [9], while specialized architectures like BrainGPT and mpLLM address more complex 3D medical imaging challenges through clinical visual instruction tuning and hierarchical mixture-of-experts approaches [7] [27]. The field continues to evolve with improved evaluation metrics like FORTE and S-Score that better capture clinical utility compared to traditional NLP metrics [39] [7]. As these technologies mature, they hold significant promise for enhancing radiologist workflow efficiency and diagnostic consistency, particularly for complex 3D imaging modalities like brain MRI.

The application of Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) to brain MRI analysis represents a frontier in medical artificial intelligence, offering potential breakthroughs in diagnostic accuracy, workflow efficiency, and personalized treatment planning. However, a significant bottleneck hindering progress in this domain is the severe scarcity of high-quality, clinically validated image-text paired datasets for training and evaluation [41]. Unlike natural images, medical data requires specialized expertise for annotation, involves privacy concerns that limit sharing, and encompasses complex 3D volumetric data that standard 2D models cannot effectively process [29] [41].

In response to these challenges, two innovative data solutions have emerged as particularly promising: Synthetic Visual Question Answering (VQA) Generation and Clinical Visual Instruction Tuning (CVIT). These approaches address the data scarcity problem from different angles—synthetic generation creates artificial but medically relevant training data, while CVIT enhances model training through structured, clinically-grounded instruction formats. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these methodologies, their experimental protocols, performance outcomes, and practical implementation considerations for researchers and drug development professionals working at the intersection of AI and neuroimaging.

Methodology and Experimental Protocols

Synthetic VQA Generation for 3D Brain MRI

The synthetic VQA approach focuses on algorithmically generating medically relevant question-answer pairs from existing medical image annotations, thereby creating scalable training resources without additional manual clinical labeling.

Experimental Protocol for mpLLM (Multiparametric LLM):

- Data Generation Pipeline: The protocol utilizes existing segmentation annotations from 3D brain MRI datasets to automatically generate medically relevant VQA pairs [29] [42]. This involves creating templates for different question types (e.g., "Is there evidence of [pathology] in the [region]?") and populating them with anatomical and pathological information derived from segmentation masks.

- Clinical Validation: Generated VQA pairs undergo rigorous review by medical experts to ensure clinical relevance and accuracy, creating what researchers describe as "the first clinically validated VQA dataset for 3D brain mpMRI" [29].

- Model Architecture: The mpLLM implements a prompt-conditioned hierarchical mixture-of-experts (MoE) architecture specifically designed to handle multiple interrelated 3D MRI modalities [29] [42]. This includes modality-level experts that process different MRI sequences (T1, T2, FLAIR, etc.) and token-level experts that handle specific regions or features within volumes.

- Training Strategy: The model trains efficiently without image-report pretraining by routing across these specialized experts and leveraging the synthetic VQA data [42]. This approach addresses the limited availability of naturally occurring image-text paired supervision in medical domains.

Clinical Visual Instruction Tuning (CVIT)

CVIT enhances standard visual instruction tuning by incorporating clinical expertise directly into the training process through structured instructions and guidelines.

Experimental Protocol for BrainGPT:

- Instruction Variants: Researchers developed four distinct instruction tuning conditions [41]:

- Plain Instruction: Basic role instruction (model as radiology assistant)

- In-context Example Instruction: 3-shot examples added to plain instruction

- Template Instruction: Structured clinical QA templates added to plain instruction

- Keyword Instruction: Categorical guidelines focused on essential radiology keywords

- Dataset Curation: The approach utilizes the 3D-BrainCT dataset containing 18,885 text-scan pairs, emphasizing lesion diversity including degree, spatial landmarks, and diagnostic impressions [41].

- Evaluation Framework: The protocol introduces Feature-Oriented Radiology Task Evaluation (FORTE), a specialized evaluation scheme that captures clinical essence by focusing on four key components: degree, landmark, feature, and impression [41].

- Model Training: BrainGPT builds upon the Otter foundation model with CVIT enhancements, enabling multi-image captioning capacity with clinical-sensible interpretation of volumetric brain CT scans [41].

Table 1: Core Methodological Differences Between Approaches

| Aspect | Synthetic VQA Generation | Clinical Visual Instruction Tuning (CVIT) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Innovation | Algorithmic generation of training data from existing annotations | Enhancement of training protocol with clinical expertise |

| Data Requirements | Segmentation masks or anatomical labels | Paired image-text datasets with clinical reports |

| Clinical Validation | Post-generation expert review | Integrated into instruction design |

| Architecture Impact | Requires specialized models (e.g., MoE) for 3D data | Compatible with various base architectures |

| Evaluation Focus | Accuracy on medically relevant VQA tasks | Clinical utility and information fidelity (via FORTE) |

Performance Comparison and Benchmark Results

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Both synthetic VQA and CVIT approaches demonstrate significant performance improvements over baseline models, though they excel in different aspects of medical MLLM capabilities.

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Methodologies

| Model/Methodology | Dataset/Task | Performance Metrics | Baseline Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| mpLLM (Synthetic VQA) | Multiple mpMRI datasets | +5.3% average improvement on medical VQA | Outperforms strong medical VLM baselines by significant margin [29] |

| BrainGPT (CVIT) | 3D-BrainCT Report Generation | FORTE F1-score: 0.71 (Degree: 0.661, Landmark: 0.706, Feature: 0.693, Impression: 0.779) | Superior to baseline Otter model (low BLEU-4 and CIDEr-R scores) [41] |