Large-Scale Neural Circuit Mapping: A Comprehensive Guide to Technologies, Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the cutting-edge technologies revolutionizing large-scale neural circuit mapping, a field critical for understanding brain function and treating neurological disorders.

Large-Scale Neural Circuit Mapping: A Comprehensive Guide to Technologies, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the cutting-edge technologies revolutionizing large-scale neural circuit mapping, a field critical for understanding brain function and treating neurological disorders. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of mapping functional circuits during behaviorally relevant time windows. It details the mechanisms, strengths, and limitations of key methodological approaches, including activity-dependent genetic tools, viral tracing, and high-throughput imaging. The content further addresses practical challenges in data management and technology validation, offering insights for troubleshooting and optimizing research pipelines. Finally, it synthesizes how these integrated technologies are paving the way for precision neuromedicine and transforming therapeutic discovery for conditions like depression, Alzheimer's, and schizophrenia.

The Foundation of Functional Connectomics: From Brain Regions to Behaviorally-Active Cells

In the study of complex networks, from artificial systems to the mammalian brain, a fundamental challenge is the identification of functional units—the building blocks that perform discrete computations or processes. Traditional analyses often assume that these units correspond to cohesive modules, where nodes are densely connected internally but sparsely connected between modules [1]. However, emerging evidence suggests a more complex landscape where sparse modules, composed of nodes with sparse internal connections that are densely linked to other modules, widely co-exist with cohesive ones [1]. Understanding the nature and interaction of these modules is critical, particularly in neuroscience, where elucidating the relationship between neural structure, dynamics, and behavior remains a primary goal. The BRAIN Initiative highlights this by identifying the analysis of interacting neural circuits as a area rich with opportunity, requiring knowledge of how activities of individual neurons and populations reflect variables like stimuli, expectations, choices, and actions [2].

Theoretical Framework: Classes of Functional Modules

Research into complex networks has revealed that functional units extend beyond the classical concept of densely interconnected communities. The following table summarizes the key types of identified modules:

Table 1: Types of Functional Modules in Complex Networks

| Module Type | Structural Definition | Functional Role | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohesive Modules | Nodes with tight, dense internal connections and sparser connections to other modules. [1] | Perform localized, specialized computations or information processing. | Traditionally the focus of community detection; often larger in size. [1] |

| Sparse Modules | Nodes with sparse internal connections that are densely connected with other sparse or cohesive modules. [1] | Act as integration hubs or communication bridges between specialized modules. | Widely co-exist with cohesive modules; generally smaller in size. [1] |

The interaction between these modules is not random; cohesive and sparse modules are often found to be spatially closely related, forming a complex interplay that underpins system function [1].

Application in Large-Scale Neural Circuit Mapping

The theoretical framework of functional units is being rigorously tested and refined in neuroscience through ambitious large-scale mapping projects. The International Brain Laboratory (IBL) has generated a seminal brain-wide dataset to understand how computations are distributed across the brain during complex behavior [3].

Experimental Protocol: Brain-Wide Neural Activity Mapping

Objective: To simultaneously record the activity of neurons across the entire mouse brain during a decision-making task to identify neural correlates of behavior and define functional units.

Methodology Details:

- Behavioral Task: Mice were trained on a visual decision-making task. A stimulus appeared on the left or right of a screen, and the mouse had to turn a wheel to center the stimulus for a reward. The task incorporated sensory, cognitive, and motor components [3].

- Neural Recording:

- Technology: 699 Neuropixels probes were inserted across 139 mice [3].

- Spatial Coverage: The recording grid covered the left forebrain and midbrain (representing contralateral stimuli/actions) and the right hindbrain and cerebellum (representing ipsilateral side) [3].

- Neuronal Yield: The study recorded 621,733 units, with 75,708 well-isolated neurons identified after stringent quality control [3].

- Data Processing & Localization:

Table 2: Key Reagents and Research Tools for Large-Scale Neural Circuit Mapping

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Neuropixels Probes | High-density electrophysiology probes for simultaneous recording of hundreds of neurons across multiple brain regions. [3] |

| Allen Common Coordinate Framework (CCF) | A standardized 3D reference atlas for the mouse brain, allowing precise anatomical registration of recorded neurons. [3] |

| Kilosort Software | An algorithm for spike sorting, which clusters electrical signals from recordings to identify the activity of single neurons. [3] |

| DeepLabCut | A tool for markerless pose estimation based on deep learning, used to track body parts and analyze animal behavior from video data. [3] |

The initial analysis of this vast dataset revealed how representations of task variables are distributed across the brain, highlighting potential functional units based on encoding properties.

Table 3: Summary of Neural Correlates from a Brain-Wide Map (Source: [3])

| Task Variable | Encoding Pattern in the Brain | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Visual Stimulus | Transiently appeared in classical visual areas after stimulus onset, then spread to ramp-like activity in midbrain and hindbrain. [3] | Representations were more constrained to specific regions and influenced fewer individual neurons compared to other variables. |

| Choice & Action | Neural responses correlated with impending motor action were found "almost everywhere in the brain." [3] | This suggests a highly distributed network for action preparation and execution. |

| Reward | Responses to reward delivery and consumption were "widespread." [3] | Indicates that reward processing is a broad function shared across many neural circuits. |

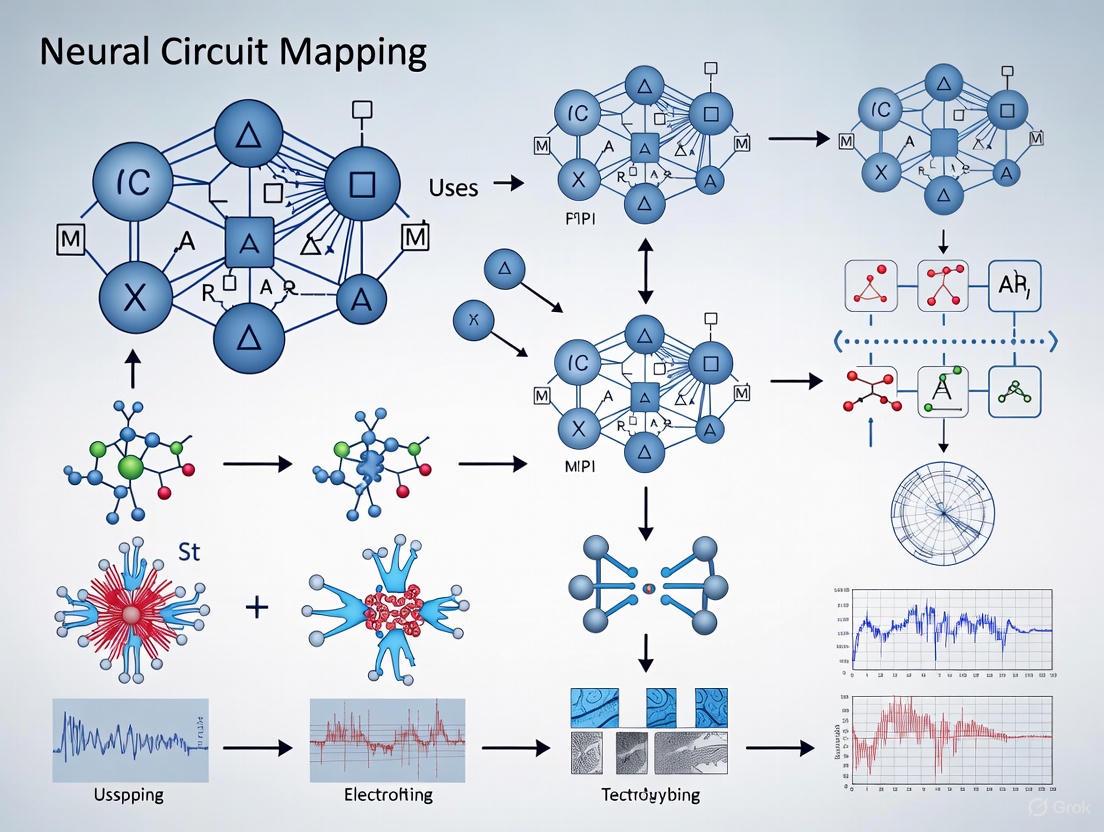

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and analytical workflow for defining functional units in neural circuits, from data acquisition to final interpretation.

The conceptual relationship between network structure and the identified types of functional modules can be summarized as follows:

Discussion and Future Directions

The convergence of complex network theory and large-scale experimental neuroscience is transforming our ability to define functional units. The findings that task variables like action are encoded nearly brain-wide, while others are more constrained, challenge purely localized models of function and support a hybrid model containing both specialized (cohesive) and integrative (sparse) modules [1] [3]. This aligns with the BRAIN Initiative's goal to integrate across spatial and temporal scales to achieve a unified view of the nervous system [2].

Future research must move beyond correlation to causation. This requires integrating the types of large-scale monitoring described here with precise interventional tools to test the significance of identified units, a direction also emphasized as a priority for the BRAIN Initiative [2]. Furthermore, a major ongoing challenge is the development of new theoretical and data analysis tools to make sense of the immense, complex datasets being generated. Success in this endeavor will provide a mechanistic understanding of mental function, ultimately informing the development of targeted therapeutic strategies for brain disorders.

Why Map Circuits? Linking Neural Dynamics to Cognition, Emotion, and Disease

Understanding the brain requires more than a catalog of its parts; it demands a blueprint of its intricate wiring and the dynamics of electrical activity that flow through it. Neural circuit mapping aims to create this blueprint, providing a detailed diagram of how individual neurons connect into functional networks to generate thoughts, emotions, and actions [2] [4]. Disruptions in these circuits are now understood to be the root cause of a wide spectrum of neurological and psychiatric diseases, making circuit-level analysis not merely an academic exercise but a critical step toward precision therapeutics [5] [4]. The central thesis is that by linking the brain's physical structure (its connectome) with its dynamic, millisecond-scale activity (its neural dynamics), we can uncover the fundamental principles that bridge biology to behavior and cognition [2]. This application note details the technologies, experimental protocols, and quantitative findings that are making this vision a reality, providing a resource for researchers and drug development professionals working at the forefront of neuroscience.

Quantitative Data from Large-Scale Mapping Efforts

Recent large-scale consortium projects have generated unprecedented datasets, quantifying the brain's connectivity and activity at an immense scale. The tables below summarize key metrics from two landmark studies.

Table 1: Scale of the MICrONS Program Circuit Mapping Dataset [5]

| Metric | Scale/Quantity | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Volume Analyzed | 1 cubic millimeter | Previously considered an unattainable goal; size of a grain of sand. |

| Total Data Volume | 1.6 Petabytes | Equivalent to 22 years of non-stop HD video. |

| Brain Slices Imaged | >25,000 | Each slice 1/400th the width of a human hair. |

| Neurons Reconstructed | >200,000 | Enables population-level analysis of circuit structure. |

| Synapses Mapped | 523 million | Provides unprecedented detail on connection points. |

| Axon Length Reconstructed | 4 kilometers | Reveals the immense density of long-range connections. |

Table 2: Scale of the Brain-Wide Neural Activity Map [3]

| Metric | Scale/Quantity | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Total Neurons Recorded | 621,733 | From 699 Neuropixels probe insertions. |

| Well-Isolated Neurons | 75,708 | Stringent quality control for single-neuron analysis. |

| Number of Mice | 139 | Ensures robustness and reproducibility across subjects. |

| Brain Areas Covered | 279 | Comprehensive coverage of the left forebrain/midbrain and right hindbrain/cerebellum. |

| Participating Laboratories | 12 | Demonstrates a standardized, collaborative approach. |

| Behavioral Task | IBL decision-making task | Integrates sensory, cognitive, and motor processing. |

Experimental Protocols for Circuit Mapping and Manipulation

Protocol: High-Resolution Electron Microscopy Connectomics

This protocol outlines the process for generating a synaptic-resolution wiring diagram from a fixed brain sample, as used in the MICrONS project [5].

Tissue Preparation and Sectioning:

- Purpose: To prepare neural tissue for ultra-high-resolution imaging.

- Procedure: A fixed cubic millimeter of brain tissue is embedded in resin. Using an ultramicrotome, the tissue block is serially sectioned into more than 25,000 ultra-thin slices (approximately 40 nm thick).

- Critical Note: Maintaining the order and integrity of the section ribbon is paramount for subsequent automated image alignment and 3D reconstruction.

Large-Scale Electron Microscopy Imaging:

- Purpose: To acquire high-resolution images of every slice.

- Procedure: An automated array of electron microscopes is used to image the entire surface of each tissue slice at nanoscale resolution (e.g., 4x4 nm per pixel). This generates a stack of 2D images representing the complete 3D volume.

- Output: A multi-petabyte dataset of raw EM images.

Automated Volume Reconstruction and Proofreading:

- Purpose: To trace neurons and identify synapses from the image stack.

- Procedure: (a) Image Alignment: 2D images are computationally aligned into a coherent 3D volume. (b) Segmentation: Machine learning algorithms (convolutional neural networks) identify the boundaries of individual neurons and subcellular structures in the aligned volume. (c) Proofreading: Human experts manually correct the automated segmentation errors to ensure biological accuracy, a time-intensive but critical step.

- Output: A complete 3D reconstruction of all neurons, axons, dendrites, and synapses within the tissue volume.

Protocol: Brain-Wide Functional Recording with Neuropixels

This protocol describes the methodology for large-scale electrophysiological recording of neural activity across the brain in behaving animals [3].

Probe Planning and Stereo-tactic Surgery:

- Purpose: To strategically target a wide array of brain regions.

- Procedure: A coordinate grid is planned for probe insertions to cover the left hemisphere of the forebrain and midbrain, and the right hemisphere of the cerebellum and hindbrain. Under deep anesthesia, mice are implanted with a cranial window and headplate. On the day of recording, one or more Neuropixels probes are inserted into the brain along the planned coordinates.

Behavioral Training and Synchronized Data Acquisition:

- Purpose: To record neural activity during a defined cognitive behavior.

- Procedure: Mice are trained to proficiency on the International Brain Laboratory (IBL) visual decision-making task. During the recording session, wideband neural data from the probes is acquired simultaneously with behavioral data (wheel movements, licks, video of whiskers and paws) and task event markers (stimulus onset, feedback).

- Critical Note: Precise synchronization of neural, behavioral, and task data streams is essential for correlating brain activity with specific aspects of behavior.

Spike Sorting and Anatomical Localization:

- Purpose: To assign action potentials to individual neurons and map them to brain regions.

- Procedure: (a) Spike Sorting: Raw voltage traces are processed using software like Kilosort to separate the activity of individual neurons ("units") from noise and other units. Stringent quality metrics are applied to identify well-isolated single neurons. (b) Histology and Registration: After the recording, the brain is processed histologically to reconstruct the probe track. The location of each recorded neuron is mapped onto a standard brain atlas, such as the Allen Common Coordinate Framework.

Protocol: Functional Circuit Interrogation with Optogenetics

This protocol is used to test the causal role of a specific neural circuit in behavior by selectively activating or inhibiting it [4].

Targeted Viral Vector Delivery:

- Purpose: To genetically introduce light-sensitive proteins (opsins) into a defined population of neurons.

- Procedure: Using stereo-tactic surgery, an adeno-associated virus (AAV) encoding an opsin (e.g., Channelrhodopsin-2 for activation, Halorhodopsin for inhibition) is injected into a specific brain region. The virus is engineered to be cell-type-specific using promotors (e.g., CaMKIIα for excitatory neurons).

Optical Fiber Implantation and Light Delivery:

- Purpose: To deliver light to the transfected brain region to control opsin activity.

- Procedure: An optical fiber (or cannula) is implanted directly above or into the viral injection site. After a several-week period for opsin expression, laser light of a specific wavelength (e.g., 473 nm blue light for ChR2) is delivered through the fiber in precise patterns (pulses, ramps) during animal behavior.

Behavioral Analysis and Functional Validation:

- Purpose: To assess the behavioral consequences of circuit manipulation.

- Procedure: The animal's behavior is quantified with and without optical stimulation. A change in behavior (e.g., impaired memory recall, induced movement, altered decision-making) demonstrates a causal role for the manipulated circuit. Post-hoc histology is required to confirm opsin expression and fiber placement.

Visualizing Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The following diagrams, generated with DOT language, illustrate key experimental workflows and logical relationships in neural circuit research.

Diagram 1: Connectomics Data Generation Pipeline.

Diagram 2: Causal Testing with Optogenetics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Neural Circuit Mapping

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Adeno-associated Virus (AAV) Vectors | Gene delivery shuttle; engineered for cell-type specificity. | Used to express fluorescent reporters, opsins (optogenetics), and DREADDs (chemogenetics) in defined neuronal populations [6] [4]. |

| Monosynaptic Rabies Virus Tracers | Retrograde tracer for mapping direct inputs to a starter cell population. | Elucidates micro-connectivity, e.g., identifying all presynaptic partners of a specific neuron type [4]. |

| Neuropixels Probes | High-density silicon probes for large-scale electrophysiology. | Enables simultaneous recording of hundreds to thousands of neurons across multiple brain regions in behaving animals [3]. |

| Tetracysteine Display of Optogenetic Elements (Tetro-DOpE) | Multifunctional probe combining real-time monitoring and manipulation. | Allows for simultaneous optogenetic control and calcium imaging of the same neuronal population, enhancing precision [4]. |

| Cre-recombinase Driver Lines | Genetically engineered mouse lines for cell-type-specific targeting. | Provides genetic access to specific cell types (e.g., parvalbumin interneurons) when combined with Cre-dependent viral vectors [4]. |

In the field of large-scale neural circuit mapping, identifying and characterizing neurons activated by specific experiences represents a fundamental challenge. Researchers cannot directly monitor every neuron in a behaving organism and instead rely on molecular proxies of neural activity. Two primary categories of such proxies have emerged: (1) calcium transients, which report millisecond-to-second-scale electrochemical activity, and (2) Immediate Early Genes (IEGs), which reflect subsequent, sustained molecular responses on a timescale of minutes to hours. While both report on aspects of neuronal activation, they capture fundamentally different phases and provide complementary information. Calcium imaging reveals the rapid, moment-to-moment dynamics of neural coding, whereas IEG expression provides a temporally integrated "timestamp" of neurons that were strongly activated during a specific time window. This application note details the experimental protocols, key reagents, and interpretive frameworks for employing these essential tools in modern neuroscience research, framed within the context of advanced neural circuit mapping technologies.

Immediate Early Genes (IEGs) as Activity Markers

Molecular Biology and Signaling Pathways of Key IEGs

Immediate Early Genes are a class of genes rapidly and transiently expressed in neurons without requiring de novo protein synthesis. They are broadly categorized into transcription factor IEGs (e.g., c-Fos, c-Jun, Npas4, Zif268) and effector IEGs (e.g., Arc, Homer1a, BDNF) [7]. Transcription factor IEGs regulate the expression of downstream target genes, while effector IEGs directly modulating synaptic function.

The expression of IEGs is typically driven by activation of specific signaling cascades initiated by neuronal activity and calcium influx. Calcium acts as a critical second messenger, linking membrane depolarization to gene transcription [8]. Elevated intracellular calcium activates enzymes like CaM kinases, which phosphorylate transcription factors such as cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB), serum response factor (SRF), and Elk-1. These transcription factors then bind to promoter elements (e.g., CRE, SRE) in IEGs, driving their transcription [9] [7]. For instance, c-Fos induction is linked to the MAPK signaling pathway and involves activation by CREB, Elk-1, and SRF [9]. Arc expression is regulated by a synaptic activity-responsive element (SARE) in its promoter, which integrates signals from MAPK, CREB, SRF, and MEF2 [9].

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathway from neuronal activity to IEG expression:

Protocol: Immunohistochemical Detection of IEG Proteins

This protocol details the simultaneous detection of Arc and c-Fos proteins in fixed brain tissue, adapted from recent studies [9] [10].

Materials and Reagents

- Primary Antibodies: Rabbit anti-Arc (e.g., Synaptic Systems), Rat anti-c-Fos (e.g., Santa Cruz Biotechnology)

- Secondary Antibodies: Species-specific antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488, 555, or 647

- Fixative: 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS

- Blocking Solution: PBS with 10% normal goat serum and 0.3% Triton X-100

- Mounting Medium: Antifade mounting medium with DAPI

Procedure

Perfusion and Tissue Preparation:

- Deeply anesthetize the animal (e.g., with ketamine/dexmedetomidine).

- Perform transcardial perfusion with ice-cold PBS followed by 4% PFA.

- Post-fix the brain in 4% PFA for 24-48 hours at 4°C, then cryoprotect in 30% sucrose.

- Section the brain on a cryostat (30-40 μm thickness) and collect free-floating sections.

Immunohistochemistry:

- Wash sections in PBS (3 × 5 minutes).

- Incubate in blocking solution for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Incubate with primary antibodies (diluted in blocking solution) for 48 hours at 4°C under gentle agitation.

- Wash in PBS (3 × 10 minutes).

- Incubate with secondary antibodies (1:1000 in blocking solution) for 2 hours at room temperature, protected from light.

- Wash in PBS (3 × 10 minutes).

- Mount sections on glass slides and coverslip with antifade mounting medium.

Image Acquisition and Analysis:

- Image using a confocal or epifluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets.

- Use automated cell detection algorithms (e.g., in ImageJ or custom software) to quantify IEG-positive cells [10].

- Normalize cell counts to area (cells/mm²) or use stereological methods for unbiased counting.

Critical Considerations

- Timing: Sacrifice animals 1 hour after behavioral stimulation for optimal c-Fos and Arc protein detection [9].

- Controls: Include both positive (e.g., kainic acid injection) and negative (home cage) controls.

- Specificity: Optimize antibody concentrations and include no-primary-antibody controls to confirm specificity.

Comparative Properties of Major IEGs

Table 1: Properties of Key Immediate Early Genes Used as Neural Activity Markers

| IEG | Type | Primary Function | Kinetics (mRNA/Protein) | Role in Plasticity & Memory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c-Fos | Transcription Factor | Forms AP-1 complex with Jun family; regulates downstream gene expression [7] | mRNA: detectable within minutes [9]; Protein: peaks ~1-2 hours [9] | Essential for LTP, LTD, and long-term memory consolidation; critical for engram formation [7] |

| Arc/Arg3.1 | Effector Protein | AMPA receptor trafficking; synaptic scaling; heterosynaptic weakening [9] [7] | mRNA: rapidly detected; Protein: peaks 1-4 hours [9] | Required for LTP consolidation and long-term memory; links activity to synaptic modification [9] |

| Npas4 | Transcription Factor | Regulates excitatory-inhibitory balance; promotes inhibitory synapse development [10] [7] | Rapidly induced | Crucial for memory consolidation; maintains circuit stability [10] |

| Zif268/Egr-1 | Transcription Factor | Synaptic plasticity; regulates genes involved in synaptic function [7] | Rapidly induced | Important for late-phase LTP and memory consolidation, particularly in cortex [7] |

Calcium Transients as Activity Markers

Genetically Encoded Calcium Indicators (GECIs)

Calcium imaging relies on indicators whose fluorescence properties change with intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca²⁺]). Genetically Encoded Calcium Indicators (GECIs), particularly the GCaMP family, have become the standard for monitoring neural activity in vivo. GCaMPs are engineered fusion proteins comprising a circularly permuted green fluorescent protein (cpGFP), calmodulin (CaM), and a CaM-binding peptide (e.g., RS20) [11]. Upon calcium binding, conformational changes enhance GFP fluorescence.

Recent engineering efforts have produced the jGCaMP8 series, which shows significantly improved kinetics and sensitivity compared to previous generations [11]. These sensors include:

- jGCaMP8s: High sensitivity with slower decay

- jGCaMP8m: Balanced sensitivity and kinetics

- jGCaMP8f: Fastest kinetics for tracking high-frequency activity

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism of GCaMP-type calcium indicators:

Protocol: Neural Activity Imaging with jGCaMP8 Sensors

This protocol describes the use of latest-generation GECIs for monitoring neural population activity in vivo.

Materials and Reagents

- Viral Vectors: AAV vectors expressing jGCaMP8 variants (e.g., AAV9-Syn-jGCaMP8s)

- Surgical Equipment: Stereotaxic apparatus, microsyringe pump

- Imaging System: Two-photon or epifluorescence microscope with appropriate excitation (~480 nm) and emission (~510 nm) filters

- Data Acquisition Software: Suite2P, ScanImage, or similar

Procedure

Viral Expression:

- Inject AAV expressing jGCaMP8 into the brain region of interest using stereotaxic surgery.

- Allow 2-4 weeks for sufficient expression.

In Vivo Imaging:

- For head-fixed imaging, implant a cranial window over the region of interest.

- Anesthetize or head-restrain the animal and position under the microscope objective.

- Illuminate with 480 nm light (appropriate power to minimize phototoxicity).

- Acquire images at 10-30 Hz frame rate, depending on spatial resolution requirements.

Data Analysis:

- Extract fluorescence traces (F) for each region of interest (ROI).

- Calculate ΔF/F₀ = (F - F₀)/F₀, where F₀ is the baseline fluorescence.

- Use deconvolution algorithms to infer spike probabilities from calcium transients.

Critical Considerations

- Sensor Selection: Choose jGCaMP8 variant based on experimental needs: jGCaMP8s for sensitivity to single spikes, jGCaMP8f for tracking high-frequency bursts [11].

- Phototoxicity: Minimize laser power and exposure duration.

- Motion Correction: Use computational methods to correct for brain movement.

Advanced Calcium-Based Activity Marking Tools

Beyond real-time monitoring, new calcium integrators enable permanent or reversible labeling of active neurons:

CaMPARI is a photoconvertible calcium sensor that permanently changes from green to red fluorescence when illuminated with violet light in the presence of high calcium, providing a snapshot of activity during a user-defined time window [12].

rsCaMPARI (reversibly switchable CaMPARI) extends this concept by allowing erasing and re-marking of activity. Its off-switching kinetics under blue light are calcium-dependent, while violet light resets the fluorescence, enabling multiple snapshots of neuronal activity in the same preparation [12].

FLiCRE is a molecular integrator that records transient calcium elevation directly into transcriptional changes, enabling subsequent readout of activity history through sequencing or histology [13].

Table 2: Comparison of Calcium-Based Activity Markers and Their Properties

| Tool | Mechanism | Temporal Resolution | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jGCaMP8 series [11] | Fluorescence intensity change with [Ca²⁺] | Milliseconds to seconds (half-rise time: ~2-7 ms) | Real-time monitoring of neural population dynamics | High sensitivity to single APs; multiple variants optimized for speed/sensitivity | Requires constant imaging; photobleaching with extended use |

| CaMPARI [12] | Calcium-dependent photoconversion (green→red) | Seconds to minutes | Snapshot of activity during specific behavioral epoch | Large field of view; no need for real-time imaging; post-hoc analysis | Irreversible conversion; single-use |

| rsCaMPARI [12] | Calcium-dependent reversible photoswitching | Seconds to minutes | Multiple activity snapshots in same sample | Erasable and re-markable; enables within-subject comparisons | Lower contrast than CaMPARI; requires precise light control |

| FLiCRE [13] | Calcium- and light-dependent transcriptional recording | Minutes | Linking cellular activity history to transcriptome | Permanent genetic record; compatible with scRNA-seq | Complex molecular biology; lower temporal resolution |

Comparative Analysis and Integration of Methods

Divergent and Complementary Information from Different Proxies

A critical finding from recent research is that different activity markers can identify substantially different neuronal populations. A 2025 study examining Arc and c-Fos expression following contextual fear conditioning found that fewer than 50% of total labeled cells expressed both markers across memory states [9]. This divergence was brain region-dependent and influenced by memory state, suggesting that Arc and c-Fos may mark functionally distinct ensembles rather than providing redundant readouts of neural activity.

Similarly, a 2025 study examining c-Fos, Arc, and Npas4 found that combinative expression patterns varied significantly across brain areas, with co-expression increasing more prominently in prefrontal cortex and amygdala following experience compared to dentate gyrus and retrosplenial cortex [10]. These findings indicate that IEG expression is not universal but reflects specific molecular responses in different circuit elements.

The relationship between calcium activity and IEG expression is equally complex. In cultured hippocampal neurons, increased correlated activity following chemical LTP induction was specifically enriched between Arc-positive neurons, suggesting that Arc expression correlates with functional connectivity refinement [14]. Furthermore, neurons expressing different IEG combinations (Arc+/c-Fos+ vs. Arc+/c-Fos-) showed different patterns of correlated activity, linking specific molecular signatures to network-level functions [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Neural Activity Mapping

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Key Features & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| IEG Antibodies | Rabbit anti-Arc, Rat anti-c-Fos, Rabbit anti-Npas4 [9] [10] | Immunohistochemical detection of IEG proteins | Enable multiplexed labeling; optimized for fixed tissue; species-specific |

| GECI Viral Vectors | AAV-Syn-jGCaMP8s/f/m [11] | Expression of calcium sensors in specific cell types | Cell-type specific promoters (e.g., Syn, CaMKIIa); high expression titers; various serotypes for targeting |

| Calcium Integrators | AAV-CaMPARI, AAV-rsCaMPARI [12] | Permanent or reversible activity marking | Large field of view; compatible with freely behaving animals; minimal equipment requirements |

| Activity Recorders | FLiCRE AAV vectors [13] | Genetic recording of calcium activity history | Compatible with single-cell RNA sequencing; links activity to cell identity |

| Neural Actuators | AAV-ChR2, AAV-NpHR | Optogenetic control of neural activity | Causal manipulation of tagged ensembles; validation of functional connectivity |

Calcium transients and IEG expression provide complementary yet distinct windows into neural activity. The choice between them—or decision to use both—depends critically on the experimental questions. Calcium imaging offers unparalleled temporal resolution for decoding real-time neural computation, while IEG mapping provides a temporally integrated view of ensembles recruited during meaningful experiences. The emerging understanding that different markers identify overlapping but non-identical populations [9] [10] suggests that a multi-modal approach will be essential for comprehensive neural circuit mapping. Future developments will likely focus on (1) further improving the temporal resolution and sensitivity of calcium indicators, (2) expanding the toolkit of IEG-based strategies to capture different phases of neuronal responses, and (3) developing integrated methods that simultaneously monitor multiple aspects of neural activity across spatial and temporal scales.

The Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative represents a transformative, large-scale effort to revolutionize our understanding of the mammalian brain. Launched in 2013, this ambitious project aims to generate a comprehensive, dynamic picture of the brain that reveals how individual cells and complex neural circuits interact at the speed of thought [2]. The BRAIN 2025 report, published in June 2014, established a rigorous scientific vision with a multi-year plan containing specific timetables, milestones, and cost estimates for achieving these goals [2] [15]. The initiative's primary focus during its first five years was on accelerated technology development, strategically shifting toward integrating these technologies to make fundamental discoveries about brain function in the subsequent five years [2]. This decadal plan emphasizes pursuing human studies and non-human models in parallel, crossing boundaries in interdisciplinary collaborations, and integrating spatial and temporal scales to build a unified view of neural circuit function [2].

The overarching vision is best captured by the initiative's seventh goal: combining diverse approaches into a single, integrated science of cells, circuits, brain, and behavior [2] [16]. This synthetic approach will enable penetrating solutions to longstanding problems in brain function, with the expectation of entirely new, unexpected discoveries resulting from the novel technologies developed. The initiative has identified the analysis of circuits of interacting neurons as particularly rich in opportunity, with potential for revolutionary advances [2]. Understanding a circuit requires identifying and characterizing component cells, defining their synaptic connections, observing their dynamic activity patterns during behavior, and perturbing these patterns to test their significance [2].

Table: The Seven Primary Goals of the BRAIN Initiative as Outlined in BRAIN 2025

| Goal Number | Priority Area | Key Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Discovering Diversity | Identify and provide experimental access to different brain cell types to determine their roles in health and disease [16]. |

| 2 | Maps at Multiple Scales | Generate circuit diagrams that vary in resolution from synapses to the whole brain [16]. |

| 3 | Monitor Neural Activity | Produce a dynamic picture of the functioning brain through large-scale monitoring of neural activity [16]. |

| 4 | Interventional Tools | Link brain activity to behavior with precise interventional tools that change neural circuit dynamics [16]. |

| 5 | Theory & Data Analysis Tools | Produce conceptual foundations for understanding the biological basis of mental processes [16]. |

| 6 | Human Neuroscience | Develop innovative technologies to understand the human brain and treat its disorders [16]. |

| 7 | Integrated Approaches | Integrate technological and conceptual approaches to discover how dynamic patterns of neural activity are transformed into cognition, emotion, perception, and action [16]. |

Application Note: Large-Scale Structural and Functional Mapping

Breakthrough in Circuit Mapping: The MICrONS Program

The Machine Intelligence from Cortical Networks (MICrONS) program stands as a landmark achievement in the BRAIN Initiative's mission to create comprehensive wiring diagrams of the brain. This collaborative effort, involving more than 150 scientists and researchers from multiple institutions, has produced the largest wiring diagram and functional map of a mammalian brain to date [5]. The project specifically aimed to build a complete functional wiring diagram of a cubic millimeter portion of a mouse's visual cortex, a goal once considered unattainable [5].

The technological scale of this endeavor is unprecedented. From a tissue sample measuring approximately one cubic millimeter, researchers created a wiring diagram containing more than 200,000 cells, 4 kilometers of axons, and 523 million synapses [5]. The dataset itself reaches 1.6 petabytes in size—equivalent to 22 years of non-stop HD video—and is freely available through the MICrONS Explorer platform [5]. This resource offers never-before-seen insight into brain function and organization, particularly in the visual system, and has been described as having transformative potential comparable to the Human Genome Project [5].

Among the most significant findings from the MICrONS project was the discovery of a new principle of inhibition within the brain. Contrary to the established view of inhibitory cells as a simple damping force, researchers found a far more sophisticated communication system where inhibitory cells are highly selective about which excitatory cells they target, creating a network-wide system of coordination and cooperation [5]. Some inhibitory cells work together to suppress multiple excitatory cells, while others are more precise, targeting only specific types. This discovery fundamentally changes our understanding of neural circuit regulation and has profound implications for understanding brain disorders involving disruptions in neural communication [5].

Brain-Wide Neural Activity Mapping

In a complementary approach to structural mapping, recent research supported by the BRAIN Initiative has achieved unprecedented scale in recording neural activity across the brain during complex behavior. A 2025 study published in Nature reported a comprehensive set of recordings from 621,733 neurons recorded with 699 Neuropixels probes across 139 mice in 12 laboratories [3]. This brain-wide map assessed how neural activity encodes key task variables during a decision-making task with sensory, motor, and cognitive components.

The recordings covered 279 brain areas in the left forebrain and midbrain and the right hindbrain and cerebellum, providing a systematic survey of brain regions using a single task with sufficient behavioral complexity [3]. The study revealed that neural correlates of certain variables, such as reward and action, were found in many neurons across essentially the whole brain. In contrast, correlates of other variables, such as the input stimulus, could be decoded from a narrower range of regions and significantly influenced the activity of fewer individual neurons [3]. These publicly available data represent a valuable resource for understanding how computations distributed across and within brain areas drive behavior.

Table: Quantitative Summary of Recent Large-Scale Brain Mapping Achievements

| Parameter | MICrONS Program (Structural) | IBL Brain-Wide Map (Functional) |

|---|---|---|

| Species | Mouse | Mouse |

| Brain Volume Mapped | 1 mm³ (visual cortex) | Entire hemisphere |

| Neurons Captured | >200,000 cells | 621,733 units (75,708 well-isolated neurons) |

| Synapses Mapped | 523 million | Not applicable |

| Spatial Resolution | Subcellular (electron microscopy) | Single-cell (Neuropixels probes) |

| Data Volume | 1.6 petabytes | Not specified |

| Key Finding | New principle of inhibitory neuron organization | Widespread encoding of action and reward variables |

| Data Accessibility | MICrONS Explorer platform | GitHub and online visualization |

Experimental Protocols for Neural Circuit Mapping

Protocol: MICrONS-Style Circuit Reconstruction

This protocol outlines the methodology for creating a complete wiring diagram of neural circuits, based on the approach pioneered by the MICrONS program [5].

Materials and Equipment

- Experimental Animals: Adult mice (any strain, typically 8-16 weeks old)

- Visual Stimulation System: Monitor for presenting movies and YouTube clips

- Two-Photon Microscopy System: For recording brain activity in vivo

- Tissue Processing Equipment: Vibratome or compresstome for brain slicing

- Electron Microscopes: Array for high-resolution imaging of brain slices

- Computational Infrastructure: High-performance computing cluster with specialized reconstruction software

Procedure

In Vivo Functional Imaging:

- Secure mouse in stereotaxic apparatus under appropriate anesthesia.

- Use two-photon microscopy to record brain activity from a defined region of the visual cortex (e.g., 1 mm³ volume) while the animal watches various visual stimuli, including movies and YouTube clips.

- Record dynamic neural activity throughout the visual stimulation protocol.

Tissue Preparation and Sectioning:

- Perfuse the animal transcardially with fixative followed by EM-compatible reagents.

- Extract the brain region of interest and embed in appropriate resin for electron microscopy.

- Section the tissue into ultra-thin slices (approximately 25,000 layers, each 1/400th the width of a human hair) using an ultramicrotome.

Electron Microscopy Imaging:

- Collect serial sections on EM grids.

- Acquire high-resolution images of each slice using an array of electron microscopes.

- Ensure overlapping fields between consecutive sections for accurate 3D reconstruction.

Image Processing and 3D Reconstruction:

- Align all EM images into a coherent stack using feature matching algorithms.

- Apply artificial intelligence and machine learning tools to trace neuronal processes, identify synaptic connections, and reconstruct the 3D architecture of the neuropil.

- Merge functional imaging data with structural reconstruction to create a comprehensive structure-function map.

Data Analysis and Validation:

- Identify all neuronal and glial cell types within the reconstructed volume.

- Map synaptic connections between neurons to establish circuit wiring diagrams.

- Correlate structural connectivity with functional activity patterns recorded during visual stimulation.

- Employ computational tools to identify organizational principles and test existing theories of neural circuit function.

Protocol: Brain-Wide Neural Activity Mapping During Behavior

This protocol describes the methodology for large-scale neural recording across multiple brain regions during complex behavior, based on the approach described in the Nature 2025 brain-wide map study [3].

Materials and Equipment

- Experimental Animals: 139 mice (94 male and 45 female) trained on decision-making task

- Neuropixels Probes: 699 probes for high-density electrophysiological recording

- Behavioral Apparatus: Setup for International Brain Laboratory (IBL) decision-making task including screen, wheel, and reward delivery system

- Video Recording System: Three cameras for behavioral monitoring

- DeepLabCut Software: For automated tracking of body parts and behavioral events

- Data Processing Infrastructure: Centralized servers for data upload, preprocessing, and sharing

Behavioral Task Procedure

Task Design:

- Implement the IBL decision-making task where mice must indicate the position of a visual stimulus by turning a wheel.

- Begin with 90 unbiased trials, then implement blocks of trials where the prior probability for the stimulus to appear on the left or right is constant at a ratio of 20:80% or 80:20%.

- Vary stimulus contrast across five possible values (100, 25, 12.5, 6.25, and 0%).

- Provide positive feedback (water reward) for correct choices and negative feedback (white-noise pulse and time out) for incorrect choices.

Animal Training:

- Train mice until they achieve stable performance (typically >81% correct choices).

- Ensure animals learn to exploit the block structure of the task, performing significantly better than chance on 0% contrast trials.

Neural Recording During Behavior:

- Insert Neuropixels probes following a standardized grid covering the left hemisphere of the forebrain and midbrain and the right hemisphere of the cerebellum and hindbrain.

- Record from multiple brain regions simultaneously while animals perform the decision-making task.

- Collect data from at least 400 trials per session.

Data Processing and Spike Sorting:

- Upload data to a central server and preprocess using standardized interfaces.

- Perform spike sorting using a version of Kilosort with custom additions.

- Apply stringent quality-control metrics to identify well-isolated neurons.

Anatomical Localization:

- Reconstruct probe tracks using serial-section two-photon microscopy.

- Assign each recording site and neuron to a brain region in the Allen Common Coordinate Framework.

Neural Data Analysis:

- Correlate neural activity with task variables including visual stimuli, choices, actions, and rewards.

- Use standardized analysis methods to ensure consistency across recordings from different laboratories.

- Employ statistical models to identify encoding of task variables across brain regions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Neural Circuit Mapping

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Neuropixels Probes | High-density electrophysiology probes for recording hundreds of neurons simultaneously across multiple brain regions [3]. | Brain-wide mapping of neural activity during complex behavior [3]. |

| Viral Tracers (AAV) | Gene delivery vehicles for labeling, recording, marking, and manipulating specific neuronal cell types [2] [16]. | Cell-type-specific monitoring and manipulation in non-human animals and humans [16]. |

| Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) | Light-sensitive ion channel for optogenetic control of neural activity with high temporal precision [17]. | Precise activation of specific neural populations to establish causal links to behavior [2]. |

| Kilosort Software | Automated spike sorting algorithm for identifying single-neuron activity from raw electrophysiological data [3]. | Processing of high-density neural recordings from Neuropixels probes [3]. |

| Allen Common Coordinate Framework (CCF) | Standardized 3D reference atlas for precise anatomical localization of recording sites and neurons [3]. | Registration of neural data to consistent brain coordinates across experiments [3]. |

| Electron Microscopy Arrays | High-resolution imaging systems for visualizing ultrastructural details including synapses and subcellular features [5]. | Dense reconstruction of neural circuits at nanometer resolution [5]. |

| Two-Photon Microscopy | Fluorescence imaging technique for monitoring neural activity in living animals with cellular resolution [5]. | Recording calcium dynamics in identified cell types during behavior [5]. |

| DeepLabCut | Markerless pose estimation software for tracking animal behavior from video recordings [3]. | Quantifying behavioral variables synchronized with neural recordings [3]. |

Data Standards and Informatics Infrastructure

The BRAIN Initiative places strong emphasis on data standardization, sharing, and informatics infrastructure to ensure the reproducibility and maximal utility of the vast datasets generated by its research programs [18]. The initiative supports the development of informatics infrastructure including data archives, data standards, and computational tools for analyzing, visualizing, and integrating diverse neural data [18]. This infrastructure facilitates data sharing across different BRAIN Initiative projects and promotes secondary analysis and reuse of datasets.

Key goals of the BRAIN Initiative informatics program include building data science infrastructure useful to the broader research community, making data and tools openly available, supporting FAIR principles of data sharing, and improving the rigor and reproducibility of BRAIN Initiative research [18]. Rather than building an all-encompassing infrastructure, the program creates tailored infrastructure to serve particular domains of scientific research, including integrated approaches to understanding circuit function, invasive devices for human CNS recording, non-invasive neuromodulation, next-generation imaging, and brain cell census or atlas construction [18].

The initiative has established specialized data archives that provide access to datasets and software tools, enabling users to analyze archived data directly in cloud environments without downloading to local machines [18]. These archives adopt and update data standards to support data sharing, scientific rigor, and reproducibility for experiments and data analysis. The BRAIN Initiative Cell Census Network (BICCN) has further developed a comprehensive data ecosystem for sharing and integrating multimodal cellular data, creating a foundational resource for the neuroscience community [19]. This ecosystem includes standardized data formats, common coordinate systems, and computational tools that enable researchers to explore and analyze comprehensive datasets on brain cell types [19].

The field of neuroscience is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving from describing static anatomical structures to understanding dynamic, behaviorally-relevant neural activity. Traditional neuroanatomical methods provided detailed snapshots of brain connectivity but could not capture the millisecond-to-second timescales at which neural circuits operate during behavior. This limitation has been addressed through the development of time-window-specific labeling technologies that enable researchers to tag, trace, and manipulate neurons based on their activity during precisely defined behavioral epochs. These methodologies represent a convergence of molecular biology, optics, and genetics, allowing for the functional dissection of neural circuits with unprecedented temporal precision. The significance of this paradigm shift is underscored by its alignment with the BRAIN Initiative's vision to produce "a dynamic picture of the brain that shows how individual brain cells and complex neural circuits interact at the speed of thought" [2].

This technical advancement is particularly valuable for drug discovery and development, as it enables the identification of specific neural ensembles and circuits underlying pathological states in neurological and psychiatric disorders. By focusing on functionally defined neural populations rather than anatomically defined regions, researchers can develop more targeted therapeutic interventions with potentially fewer off-target effects. This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for implementing these cutting-edge technologies, with a specific focus on their utility for researchers in both academic and pharmaceutical settings.

Molecular Mechanisms of Activity-Dependent Labeling

Time-window-specific labeling technologies operate by integrating two key molecular events: (1) neuronal activity signals (typically calcium influx or immediate-early gene expression), and (2) a user-defined trigger (light or drug administration). This "AND-gate" logic ensures that only neurons active during the specific experimental time window are labeled [20] [21].

Calcium-Triggered Labeling Systems

Calcium serves as a universal second messenger in neuronal signaling, with intracellular calcium concentrations rising rapidly during action potentials. Calcium-dependent labeling systems exploit this phenomenon to tag active neurons:

- Single-Component Calcium Integrators: Tools like CaMPARI (Calcium Modulated Photoactivatable Ratiometric Integrator) are engineered fluorescent proteins that undergo irreversible photoconversion from green to red fluorescence when illuminated with violet light in the presence of elevated calcium concentrations. This system operates on very fast timescales (seconds) but requires light illumination, which can penetrate tissue poorly [22] [21].

- Calcium-Dependent Transcriptional Systems: More complex systems like Cal-Light and FLiCRE (Fast Light and Calcium-Regulated Expression) combine calcium sensing with light-gated transcriptional activation. In these systems, calcium-bound calmodulin interacts with a light-oxygen-voltage (LOV) domain that is light-sensitive. Only when both calcium is elevated and specific light wavelengths are applied does a transcription factor become active and drive expression of a reporter gene [20] [23] [21]. This transcriptional readout allows for stronger signal amplification and subsequent manipulation of labeled neurons.

The following diagram illustrates the molecular logic of calcium- and light-gated systems like Cal-Light:

Immediate-Early Gene (IEG) Systems

Immediate-early genes such as Fos, Arc, and Egr1 are rapidly and transiently expressed following neuronal activation, reaching peak expression within 30-60 minutes after stimulation [20] [21]. Traditional IEG-based labeling (e.g., in Fos-tTA or Fos-CreER transgenic mice) has temporal resolution on the scale of hours. However, when combined with drug-dependent switches, these systems enable more precise temporal control:

- TRAP (Targeted Recombination in Active Populations): In TRAP mice, the Fos promoter drives expression of a drug-inducible Cre recombinase (CreER). Administration of tamoxifen (or its metabolite 4-OHT) during a behavioral epoch causes permanent genetic labeling of neurons that were active during that time window [23] [21]. The temporal resolution is determined by tamoxifen pharmacokinetics, typically requiring 2-3 days between labeling sessions [21].

The diagram below outlines the workflow for IEG-based systems like TRAP:

Quantitative Comparison of Labeling Technologies

Selecting the appropriate labeling technology requires careful consideration of temporal parameters, spatial scale, and experimental constraints. The following table provides a comparative analysis of major time-window-specific labeling systems:

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Major Time-Window-Specific Labeling Technologies

| Technology | Molecular Mechanism | Temporal Resolution | Time Window | Primary Readout | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CaMPARI [22] [21] | Ca²⁺-dependent photoconversion | Seconds | Seconds | Fluorescence conversion (Green→Red) | Very fast; works in freely moving animals | Limited tissue penetration; no genetic access |

| Cal-Light [20] [21] | Ca²⁺ + Light → Transcription | Minutes | Minutes | Reporter gene expression | High specificity; genetic access for manipulation | Requires blue light illumination |

| FLiCRE [23] | Ca²⁺ + Light → Recombinase | Minutes | Minutes | Recombinase-dependent reporter | Permanent genetic labeling; high amplification | Complex viral delivery |

| TRAP [23] [21] | IEG + Drug → Recombinase | Hours | 1-6 hours | Recombinase-dependent reporter | Whole-brain access; well-established mouse lines | Lower temporal resolution; drug kinetics dependence |

| TetTag [21] | IEG + Drug → Transcription | Days | Hours | Reporter gene expression | Whole-brain mapping | Low temporal resolution (2-3 days between tags) |

Application Notes for Drug Development Research

Time-window-specific labeling technologies offer powerful applications throughout the drug discovery and development pipeline:

- Target Identification: These tools can identify specific neural ensembles activated in disease states or by existing therapeutics. For example, applying these methods in animal models of Alzheimer's disease has revealed early dysfunction in entorhinal-hippocampal circuits, highlighting potential therapeutic targets [24].

- Mechanism of Action Studies: By labeling neurons activated by psychoactive compounds, researchers can identify the specific circuits through which these compounds exert their effects. This approach has been used to study the effects of serotonergic hallucinogens like LSD, revealing that its neural and experiential effects are mediated by 5-HT2A receptor-dependent modulation of cortical pyramidal neuron gain [25].

- Therapeutic Efficacy Assessment: The progression of circuit-level dysfunction can be tracked longitudinally in disease models, and the rescue of normal activity patterns by therapeutic candidates can serve as a functional biomarker of efficacy. This is particularly valuable for disorders like Alzheimer's, where circuit dysfunction appears before overt pathology [24].

- Human iPSC-Derived Models: The principles of functional circuit mapping are now being extended to in vitro human models. Ultra-high-density CMOS microelectrode arrays (MEAs) with >200,000 electrodes enable field potential imaging of brain organoids, allowing for single-cell spike detection and network connectivity analysis in human tissue [26].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Mapping Behaviorally-Activated Ensembles Using Cal-Light

Application: Identifying neurons activated during a specific learning task or sensory experience.

Materials:

- AAV vectors expressing Cal-Light system components

- Stereotaxic injection apparatus

- Fiber optic cannulas and laser system (473 nm)

- Behavioral apparatus

- Standard immunohistochemistry supplies

Procedure:

Surgical Preparation:

- Anesthetize subject and secure in stereotaxic frame.

- Inject AAV9-CaM-FLEx-QF and AAV9-LOV-QUAS-GFP (or similar) into target brain region.

- Implant fiber optic cannula positioned above injection site.

Recovery and Expression:

- Allow 3-4 weeks for viral expression and protein stability.

Behavioral Paradigm with Light Delivery:

- Habituate subject to behavioral context and tethering.

- Deliver 473 nm light pulses (e.g., 1 s ON/2 s OFF, 10 mW/mm² at fiber tip) throughout the behavioral task (typically 30-60 minutes).

- Include appropriate control groups without light or without behavior.

Tissue Processing and Analysis:

- After 24-48 hours, perfuse and fix brain.

- Section brain and process for GFP immunohistochemistry.

- Image labeled neurons using confocal or light sheet microscopy.

- Quantify labeled cells by brain region and correlate with behavioral measures.

Troubleshooting:

- Low labeling: Verify light power at fiber tip; check viral titer and expression.

- High background: Reduce light power or optimize calcium sensitivity thresholds.

- Non-specific labeling: Include additional controls (no behavior, no light).

Protocol 2: Circuit Tracing from Behaviorally-Activated Neurons Using TRAP

Application: Identifying inputs to neurons activated during a specific behavioral epoch.

Materials:

- TRAP2 mice (Fos-CreER²) or similar

- Tamoxifen or 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT)

- AAV-FLEX-G-deleted Rabies-GFP and AAV-FLEX-TVA

- Standard histology supplies

Procedure:

TRAP Labeling:

- Administer tamoxifen (100 mg/kg, i.p.) or 4-OHT (10-50 mg/kg, i.p.) 30-60 minutes before behavioral task.

- Subject animals to behavioral paradigm.

- Wait 24-48 hours for Cre-mediated recombination and protein expression.

Monosynaptic Tracing:

- Inject AAV-FLEX-TVA (envelope protein) and AAV-FLEX-RG (rabies glycoprotein) into target brain region.

- After 3 weeks, inject EnvA-pseudotyped G-deleted Rabies-GFP.

- Allow 7 days for retrograde transport.

Analysis:

- Perfuse and section brain.

- Image starter cells (GFP+ in target region) and input neurons (GFP+ in connected regions).

- Calculate connectivity strength index: (number of presynaptic neurons in each region) / (number of starter cells).

Troubleshooting:

- Low TRAP efficiency: Optimize tamoxifen dose and timing relative to behavior.

- Incomplete tracing: Verify viral titer and injection placement.

- Non-specific labeling: Include no-tamoxifen controls.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of time-window-specific labeling requires specific genetic tools, viral vectors, and compounds. The following table details key reagents:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Time-Window-Specific Labeling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetically Encoded Sensors | CaMPARI, Cal-Light, FLiCRE | Convert neuronal activity into permanent labels | Available as plasmids or packaged in AAVs; require viral delivery |

| Transgenic Mouse Lines | TRAP2 (Fos-CreER²), Fos-tTA, Arc-CreER | Provide genetic access to recently active neurons | Enables whole-brain studies without viral delivery limitations |

| Inducing Agents | Tamoxifen, 4-Hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT), Doxycycline | Activate inducible recombinase or transcription systems | Timing of administration critical for temporal precision |

| Viral Vectors | AAVs (serotypes 1, 2, 5, 8, 9), Rabies virus (ΔG) | Deliver genetic constructs and enable trans-synaptic tracing | AAV serotype selection affects tropism and spread |

| Activity Reporters | GFP, tdTomato, mCherry, Channelrhodopsin | Visualize and manipulate labeled neurons | Fluorescent proteins for visualization; opsins for manipulation |

Time-window-specific labeling technologies have fundamentally transformed our approach to studying neural circuits, bridging the gap between static anatomy and dynamic function. The protocols and applications outlined herein provide a roadmap for researchers to implement these powerful methods in their own investigations, particularly those focused on understanding the circuit basis of neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on improving temporal resolution, expanding the palette of simultaneously usable labels for comparing multiple time points or behavioral states, and enhancing compatibility with non-invasive imaging techniques for longitudinal studies in the same subjects. As these tools continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly accelerate the development of circuit-based therapeutics for brain disorders, bringing us closer to the BRAIN Initiative's vision of a comprehensive understanding of the brain in health and disease [2].

The Neurotechnologist's Toolkit: Methods for Mapping, Monitoring, and Manipulating Circuits

A central challenge in modern neuroscience is the precise identification and manipulation of neuronal ensembles that are activated during specific behaviors, sensory experiences, or cognitive states. Activity-dependent genetic labeling technologies represent a revolutionary approach for capturing neural activity patterns during user-defined time windows, enabling researchers to permanently tag populations of active neurons for subsequent visualization, connectivity analysis, or functional manipulation [27] [21]. These tools bridge the critical gap between transient neural activity and stable genetic access, allowing for the examination of functional neural circuits with unprecedented precision.

The fundamental principle underlying these technologies involves coupling molecular proxies of neuronal activation—typically intracellular calcium transients or immediate early gene (IEG) expression—with inducible genetic systems that provide permanent labels or functional actuators [27] [21]. When a neuron is activated, membrane depolarization leads to calcium influx through voltage-gated channels, triggering downstream signaling pathways including calmodulin (CaM) activation and phosphorylation of transcription factors like CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein) [27]. This ultimately drives the expression of IEGs such as Fos, Arc, and Egr1 [28]. Activity-dependent tools harness these signaling cascades to link neuronal activation to the expression of reporter genes or optogenetic actuators within precisely defined temporal windows controlled by light or drug administration.

These technologies are particularly valuable within the broader context of large-scale neural circuit mapping initiatives such as the BRAIN Initiative and the MICrONS project, which aim to reconstruct complete wiring diagrams of neural circuits and understand their functional dynamics [2] [5]. The ability to tag neurons active during specific behaviors and then trace their connections or manipulate their activity provides crucial insights into the circuit-level mechanisms underlying perception, cognition, and action, with significant implications for understanding and treating neurological and psychiatric disorders [2] [5].

Activity-dependent genetic labeling technologies can be broadly classified into several categories based on their molecular mechanisms, temporal resolution, and readout modalities. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of major technology classes.

Table 1: Classification of Major Activity-Dependent Genetic Labeling Technologies

| Technology Class | Molecular Mechanism | Temporal Resolution | Stimulation Required | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IEG-Based Systems (TRAP, TetTag) | Drug-regulated IEG promoter activity | Hours to days [21] | Drug (e.g., doxycycline, 4-OHT) [21] | Whole-brain mapping of neurons active over days [27] |

| Calcium Integrators (CaMPARI, CaMPARI2) | Calcium-dependent photoconversion | Seconds to minutes [27] [21] | Blue/UV light + calcium | Large-scale activity mapping in transparent organisms [27] |

| Transcriptional Reporters (FLARE, Cal-Light, CaST) | Calcium/light-gated transcription | Minutes to hours [29] [30] | Blue light + calcium [30] or biotin [29] | Recording and manipulating ensembles in defined windows [29] [30] |

| Improved Systems (cytoFLARE, scFLARE) | Optimized calcium sensing and nuclear export | Minutes [30] | Blue light + calcium | High-sensitivity neuronal tagging in complex models [30] |

Immediate Early Gene (IEG)-Based Systems

IEG-based systems utilize promoters of activity-dependent genes such as Fos, Arc, and Egr1 to drive the expression of genetic reporters or actuators. The Temporal Targeting (TetTag) system uses a doxycycline-regulated transgene under control of the Fos promoter to express a tagged marker protein during a specific time window defined by doxycycline administration [21]. Similarly, Targeted Recombination in Active Populations (TRAP) employs Cre recombinase under control of the Fos promoter in combination with drug-dependent Cre activity [27]. These systems are particularly valuable for whole-brain mapping studies due to the widespread availability of transgenic mouse lines and the ability of drugs to uniformly penetrate brain tissue [21].

Calcium-Dependent Photoconvertible Tools

CaMPARI and CaMPARI2 are engineered fluorescent proteins that undergo irreversible photoconversion from green to red fluorescence when illuminated with violet light in the presence of high calcium concentrations [27]. These single-component tools operate on timescales of seconds, making them ideal for capturing neural activity during brief behavioral episodes. However, they require illumination with specific light wavelengths and have limited utility in deep brain structures or non-transparent organisms due to light scattering [27] [21].

Calcium and Light-Gated Transcriptional Reporters

This class of tools includes FLARE (Fast Light- and Activity-Regulated Expression), Cal-Light, and their optimized variants, which combine calcium sensing with light-gated transcriptional activation. These systems typically employ a modular design where calcium-dependent protein interactions (CaM/M13) reconstitute a protease (TEVp) that cleaves and releases a transcription factor from a light-sensitive membrane anchor, allowing it to translocate to the nucleus and drive reporter gene expression only during coincident calcium elevation and blue light illumination [27] [30]. The recently developed cytoFLARE system improves sensitivity through cytosolic tethering of the transcription factor and optimization of CaM/M13 binding affinity, achieving a 2.7-fold improvement in signal-to-background ratio compared to previous versions [30].

Biochemical Tagging Approaches

The most recent innovation in this field is Ca2+-activated split-TurboID (CaST), which uses an enzyme-catalyzed approach to biochemically tag activated cells with biotin within 10 minutes of stimulation [29]. Unlike transcription-based systems that require hours for protein expression, CaST provides immediate readout capability and does not require light stimulation, making it uniquely suitable for non-invasive applications in freely behaving animals [29].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Selected Activity-Dependent Tools

| Tool Name | Signal-to-Background Ratio | Time to Readout | Minimum Activation Window | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRAP | Varies by line | 6-18 hours [29] | ~1 hour | Whole-brain access, well-established lines |

| CaMPARI2 | ~6-fold [27] | Immediate | Seconds | Single-component, rapid response |

| FLiCRE | ~5-fold [30] | 6-18 hours [29] | 1-5 minutes | Moderate temporal resolution |

| cytoFLARE | 8.4-fold (light), 6.5-fold (calcium) [30] | 6-18 hours [29] | 1 minute | High sensitivity, suitable for Drosophila |

| CaST | AUC: 0.93 [29] | Immediate | 10 minutes [29] | No light required, immediate readout |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: cytoFLARE-Mediated Neuronal Ensemble Tagging in Drosophila

Application: Labeling and optogenetic manipulation of nociceptive neurons in Drosophila larvae [30].

Materials:

- cytoFLARE transgenic Drosophila lines

- Blue light delivery system (LED or laser)

- Optogenetic setup for activation (e.g., ChR2)

- Immunohistochemistry reagents for visualization

- Confocal microscope

Procedure:

- Genetic Crosses: Generate flies expressing cytoFLARE in neuronal populations of interest using Gal4/UAS system.

- Sensory Stimulation: Apply specific sensory stimulus (e.g., thermal or mechanical) to activate nociceptive pathways while simultaneously delivering blue light (470 nm) to the whole animal or targeted body regions.

- Light Administration: Illuminate with blue light for 1-5 minutes during the behavioral stimulus to define the tagging window.

- Wait for Expression: Allow 6-24 hours for transcription factor translocation and reporter gene expression (e.g., GFP, optogenetic actuators).

- Validation: Sacrifice a subset of animals and process for immunohistochemistry to confirm specific labeling of activated ensembles.

- Functional Manipulation: In remaining animals, use expressed optogenetic tools (e.g., ChR2 for activation, NpHR for inhibition) to manipulate tagged ensembles during behavior tests.

- Analysis: Quantify behavioral changes and correlate with activated ensemble manipulation.

Troubleshooting:

- High background: Optimize blue light intensity and duration to minimize leakiness.

- Low signal: Ensure calcium stimulation is sufficient during the light window; consider increasing stimulus intensity.

- Variable expression: Maintain consistent genetic background and experimental conditions.

Protocol: CaST-Based Biochemical Tagging in Mice

Application: Rapid tagging of prefrontal cortex neurons activated by psilocybin administration [29].

Materials:

- AAV vectors expressing CaST-IRES

- Stereotaxic surgery equipment

- Biotin (cell-permeable)

- Psilocybin or other pharmacological agents

- Streptavidin-conjugated detection reagents

- Confocal microscope or flow cytometry equipment

Procedure:

- Stereotaxic Injection: Inject AAV-CaST-IRES into the medial prefrontal cortex of mice using standard stereotaxic procedures.

- Recovery: Allow 3-4 weeks for viral expression and recovery from surgery.

- Biotin Administration: Inject biotin intraperitoneally or intravenously to provide the tagging substrate.

- Pharmacological Stimulation: Administer psilocybin or vehicle control immediately after biotin injection.

- Tissue Processing: Sacrifice animals 10 minutes to 1 hour after stimulation and perfuse with fixative.

- Detection: Process brain sections for streptavidin-based detection (e.g., streptavidin-Alexa Fluor 647).

- Analysis: Image and quantify biotin-positive cells to identify activated ensembles.

Troubleshooting:

- Low biotinylation: Increase biotin dose or extend the interval between biotin administration and perfusion.

- High background: Include controls without viral expression to account for endogenous biotinylation.

- Regional variability: Verify viral expression patterns and injection placement.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

The molecular engineering of activity-dependent tools exploits natural signaling pathways that convert neuronal activity into stable genetic labels. The following diagrams illustrate the key mechanisms underlying major tool classes.

IEG-Based Systems Mechanism

Diagram 1: IEG-Based System Mechanism. Neuronal activity triggers calcium influx and CREB phosphorylation, leading to IEG promoter activation. Drug administration controls the temporal window for reporter expression. [27] [28]

Calcium and Light-Gated Transcriptional Reporter Mechanism

Diagram 2: Calcium/Light-Gated System Mechanism. Coincident blue light and calcium elevation trigger TEV protease reconstitution and transcription factor release, driving reporter gene expression. [27] [30]

CaST Biochemical Tagging Mechanism

Diagram 3: CaST Biochemical Tagging Mechanism. Calcium elevation triggers reconstitution of split-TurboID, which uses exogenous biotin to label nearby proteins, enabling immediate detection. [29]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Activity-Dependent Labeling Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viral Vectors | AAV1, AAV2, AAV5, AAV9 | Deliver genetic constructs to target cells | Serotype determines tropism and spread |

| Transgenic Animals | Fos-tTA, Fos-Cre, UAS-reporter lines | Provide cell-type-specific expression | Background strain may affect results |

| Activity-Dependent Tools | TRAP, CaMPARI2, FLARE, cytoFLARE, CaST | Tag active neurons | Choose based on temporal resolution needs |

| Inducing Agents | Doxycycline, 4-OHT, Biotin, Blue Light | Control time window of tagging | Pharmacokinetics affect temporal precision |

| Detection Reagents | Antibodies (anti-GFP, anti-RFP), Streptavidin-conjugates | Visualize tagged neurons | Sensitivity and background vary |

| Optogenetic Actuators | Channelrhodopsin (ChR2), Halorhodopsin (NpHR) | Manipulate tagged ensembles | Activation kinetics differ |

| Calcium Indicators | GCaMP6, GCaMP7 | Validate activity patterns | Signal-to-noise varies by indicator |

Applications in Neural Circuit Mapping

Activity-dependent genetic labeling technologies have become indispensable tools for deciphering the functional organization of neural circuits. In the context of large-scale mapping projects like the MICrONS program, which reconstructed a cubic millimeter of mouse visual cortex containing over 200,000 cells and 523 million synapses, these tools provide crucial functional annotations to complement structural connectomics [5]. When integrated with brain-wide activity mapping efforts such as the International Brain Laboratory's dataset of 621,733 neurons recorded during decision-making behavior, activity-dependent tagging enables researchers to identify and manipulate specific ensembles encoding task variables like sensory stimuli, choices, and rewards [3].

These technologies have revealed fundamental principles of neural circuit function, including the discovery that inhibitory neurons exhibit highly selective targeting of excitatory cells rather than acting as blanket suppressors [5]. Furthermore, they have enabled the identification of engram cells—neuronal populations that store specific memories—and their reactivation during recall, providing insights into the cellular basis of memory formation and retrieval [27]. In preclinical studies, these approaches have been used to investigate circuit mechanisms underlying neurological and psychiatric disorders and to identify potential targets for therapeutic intervention [2] [5].

Recent innovations in complementary technologies, such as the PRIME fiber-optic system that enables reconfigurable light delivery to multiple brain regions through a single implant, further enhance the utility of activity-dependent tools by allowing more precise temporal and spatial control during the tagging process [31]. Similarly, advances in large-scale neural recording using high-density electrodes like Neuropixels provide unprecedented opportunities to validate the specificity and completeness of genetic tagging approaches [3] [32].