High-Resolution MRI vs. Standard MRI: A Deep Dive into Tissue Specificity for Research and Drug Development

This article explores the transformative impact of high-resolution and ultra-high-field Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) on tissue specificity, a critical factor for researchers and drug development professionals.

High-Resolution MRI vs. Standard MRI: A Deep Dive into Tissue Specificity for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of high-resolution and ultra-high-field Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) on tissue specificity, a critical factor for researchers and drug development professionals. We cover the foundational physics behind resolution and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) gains at higher field strengths. The piece details methodological hardware advancements, such as high-performance gradient coils and multi-channel receiver arrays, and their application in neurology, oncology, and musculoskeletal imaging. It also addresses key challenges like intensity standardization and artifacts, providing optimization strategies. Finally, we examine the validation of high-resolution MRI through its role as a qualified biomarker in clinical trials and its comparative performance against standard MRI, synthesizing how these advances de-risk and accelerate the drug development pipeline.

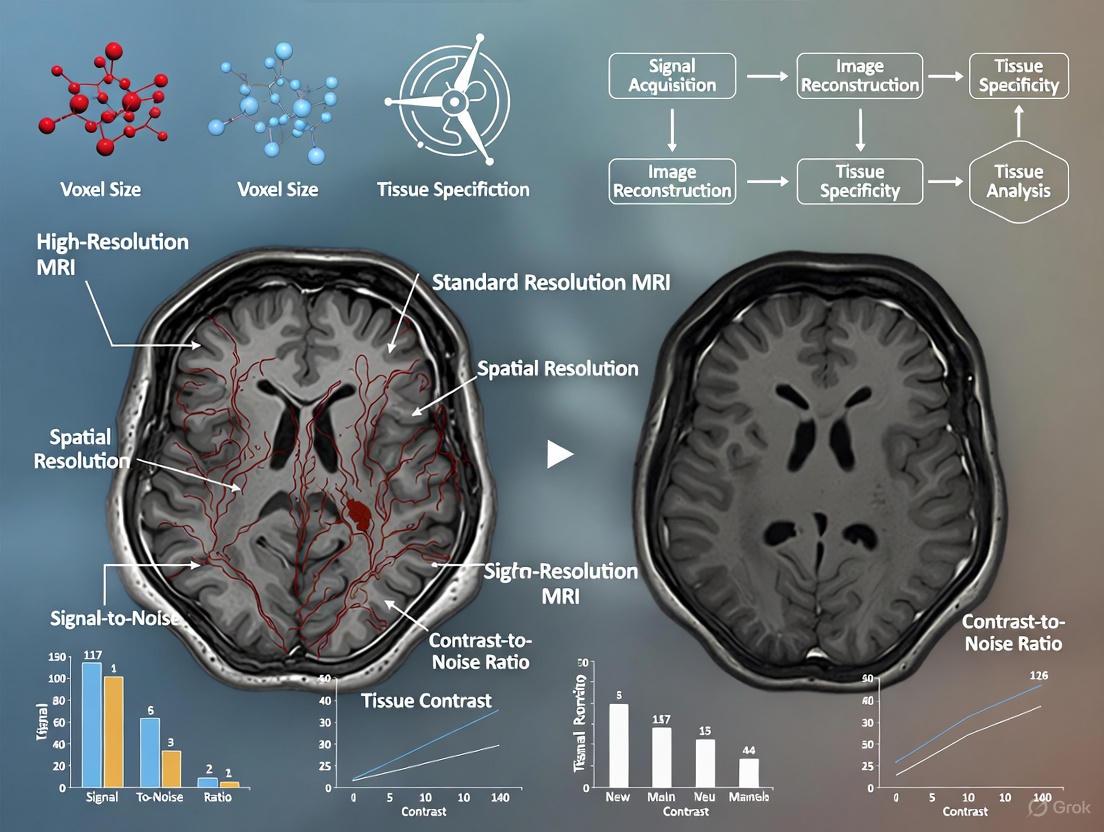

The Fundamental Principles: How Magnetic Field Strength and Resolution Dictate Tissue Contrast

In magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the pursuit of higher spatial resolution is fundamentally constrained by the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The relationship between SNR and the main magnetic field strength (B0) serves as a critical foundation for technological advancement in neuroimaging, particularly in research requiring exquisite anatomical detail. The intrinsic SNR gain at higher fields enables researchers to achieve superior spatial resolution within practically feasible scan times, thereby facilitating more precise visualization of neural structures and pathological features. This principle is especially relevant for high-resolution MRI studies focused on tissue specificity, where the ability to discriminate fine anatomical details can significantly impact the detection and characterization of neurological disorders [1]. The following sections will explore the fundamental physics underlying the B0-SNR relationship, present experimental validations across various field strengths, detail the advanced hardware that exploits this principle, and examine practical applications in contemporary neuroscience and clinical research.

The Fundamental Physics of SNR and Field Strength Dependence

The signal-to-noise ratio in MRI has a well-established theoretical dependence on the main magnetic field strength. The fundamental relationship is often described as SNR ∝ B0, suggesting a linear improvement with increasing field strength [1]. However, empirical measurements in practical imaging scenarios frequently reveal a more complex, supralinear relationship. At ultra-high fields (≥7T), the intrinsic SNR has been shown to increase with B0 raised to a power greater than one, with studies reporting exponents of approximately 1.65 [2]. This supralinear gain is a key motivation for developing ultra-high-field MRI systems for research applications.

The physical basis for this relationship stems from the population difference between nuclear spin states aligned with and against the main magnetic field. This difference, which determines the net measurable magnetization, increases approximately linearly with B0 according to the principles of quantum mechanics. Consequently, the available signal for image formation is greater at higher fields. The practical realization of this theoretical gain is modulated by several factors, including changes in tissue relaxation times (T1, T2, T2) and increasing technical challenges related to B0 and B1 field inhomogeneity at higher field strengths [2] [1]. For instance, T1 relaxation times lengthen with increasing B0, which can affect contrast mechanisms, while T2 values shorten, influencing the signal in gradient-echo-based sequences.

Figure 1: The Fundamental Relationship Between Magnetic Field Strength and Image Quality. This diagram illustrates the direct relationship between increasing main magnetic field strength (B₀) and improvements in both signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and the resulting image quality parameters, underpinned by fundamental physical principles.

Experimental Validation and Quantitative Data

Empirical Evidence from Multi-Field Strength Studies

Experimental measurements consistently validate the theoretical supralinear gain in SNR with increasing field strength. A comprehensive 2024 study systematically evaluated SNR across five field strengths from 3T to 14.1T using small surface coils relevant for animal imaging. Before coil sensitivity correction, the observed SNR increase in non-conductive samples was highly supralinear, ranging from B0^1.6 to B0^2.7 depending on the distance from the coil. In conductive samples, which better mimic biological tissues, the growth was approximately linear near the coil surface and increased up to a B0^2.0 dependence at greater distances. After correcting for coil sensitivity, the ultimate intrinsic SNR increase was independent of sample loading with a consistent B0^2.1 dependence, confirming the substantial benefit of higher magnetic fields [3].

High-Resolution Structural Imaging at Ultra-High Field

The practical benefit of increased SNR is most directly realized through enhanced spatial resolution. As summarized in Table 1, the improved SNR at 7T enables routine acquisition of structural images at sub-millimeter resolutions that are challenging to achieve at lower field strengths. For example, 7T MRI can visualize the hippocampal formation at 450-μm in-plane resolution, revealing anatomical details critical for epilepsy research [1]. The next-generation 7T scanner described by [4] pushes this further, achieving functional imaging studies at 0.35–0.45 mm isotropic resolution, which begins to approach the scale of cortical columns and layers.

Table 1: Typical Structural Imaging Resolutions Achievable at Different Field Strengths

| Field Strength | Typical Isotropic Resolution (mm) | Voxel Volume (μL) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.5T | 1.0 × 1.0 × 1.0 | 1.0 | Clinical standard, general neuroimaging |

| 3.0T | 0.8 × 0.8 × 0.8 | 0.51 | Pre-surgical planning, detailed anatomy |

| 7.0T | 0.6 × 0.6 × 0.6 | 0.22 | Mesoscale imaging, cortical layers |

| Next-Gen 7T | 0.35 × 0.35 × 0.35 | 0.04 | Cortical columns, laminar fMRI |

The Resolution-SNR Trade-Off in MRS

The relationship between voxel size and SNR becomes more complex at high magnetic fields. A foundational 2001 study challenged the conventional wisdom that SNR is linearly proportional to voxel volume in proton MR spectroscopy (¹H-MRS). When voxel dimensions were halved (reducing volume eightfold), the metabolite SNR decreased only fourfold due to a commensurate twofold decrease in local linewidths (Δυ). This T2 increase with smaller voxels occurs because regional B0 inhomogeneities (ΔB0), which dominate linewidths at high fields, are averaged more effectively in smaller voxels. This phenomenon means that both spatial and spectral resolution can be doubled at a significantly smaller-than-expected SNR penalty, enabling quality high spatial resolution (0.75 × 0.75 × 0.75 cm³) metabolic maps in clinically feasible acquisition times [5].

Advanced Hardware for Exploiting the B0-SNR Relationship

Next-Generation Gradient Systems

Maximizing the benefit of high field strength requires complementary advances in gradient performance. A next-generation 7T scanner described by [4] features an asymmetric head-only gradient coil with a third layer of windings, achieving performance metrics an order of magnitude greater than standard 7T systems: 200 mT/m maximum amplitude and 900 T/m/s slew rate. This enhanced gradient performance enables higher resolution diffusion imaging, reduces echo spacing in EPI sequences to minimize T2* blurring and geometric distortion, and permits shorter echo times for increased signal [4].

High-Density Receiver Array Coils

Radiofrequency receiver technology plays a crucial role in translating field strength advantages into measurable signal. The same next-generation 7T system implements a 128-channel receiver system with both 64- and 96-channel receiver coil arrays. Compared to a standard 32-channel array, these high-density arrays provide approximately 30% higher SNR in cortical regions due to smaller coil elements (∼4 cm diameter) that better match the tissue geometry of the human head. Additionally, the accelerated parallel imaging capability of these arrays reduces the g-factor noise penalty, enabling higher acceleration factors for faster acquisition [4].

Table 2: Key Hardware Components for Maximizing SNR at Ultra-High Field

| Component | Standard 7T Performance | Next-Generation 7T Performance | Impact on SNR/Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Strength | 80 mT/m (AC84) | 200 mT/m (Impulse) | ↑ Encoding resolution, ↓ TE |

| Gradient Slew Rate | 400-500 T/m/s | 900 T/m/s | ↑ Acquisition speed, ↓ distortions |

| Receiver Channels | 32 channels | 128 channels | ↑ Parallel imaging acceleration |

| Coil Element Size | ~6-8 cm diameter | ~4 cm diameter | ↑ Cortical SNR by ~30% |

Methodologies for SNR Measurement and Sequence Optimization

Standardized SNR Measurement Protocols

Consistent methodology is essential for valid comparison of SNR across platforms and field strengths. The most common approach involves region-of-interest (ROI) measurements:

- Place the first ROI on homogeneous tissue with high signal intensity (e.g., white matter)

- Place the second ROI outside the tissue in the image background

- Calculate SNR = Signalmean / Noisestandard_deviation [6]

For dynamic studies like DCE-MRI, an alternative definition uses repeated measurements: SNR = Signalmean / Standarddeviationacrossbaselineimageframes [7]. This approach accounts for temporal stability in addition to spatial noise characteristics.

Sequence Parameter Optimization for SNR

Beyond field strength, numerous acquisition parameters influence the final image SNR:

- Slice Thickness: Increasing slice thickness from 2mm to 6mm can increase SNR by approximately 125% (from 40% to 90% relative SNR), though with reduced spatial resolution and increased partial volume effects [6]

- Receiver Bandwidth: Halving the receiver bandwidth increases SNR by approximately 30%, though at the cost of increased susceptibility artifacts and longer scan times [6]

- Repetition Time (TR) and Echo Time (TE): Increasing TR enhances SNR but reduces T1 weighting; decreasing TE increases SNR but reduces T2 weighting [6]

Applications in Neuroimaging Research

Mesoscale Imaging of Cortical Architecture

The enhanced SNR at 7T enables visualization of brain architecture at an unprecedented scale. As illustrated in Figure 2, next-generation 7T scanners achieve sufficient resolution to resolve cortical layers and columns, which are fundamental functional units of cerebral organization. With human cortical thickness varying between 1.5 and 4.5 mm, and cortical columnar features measuring 0.6–1.0 mm, resolutions of 0.3–0.6 mm are required to adequately sample these structures while minimizing partial volume effects [4].

Figure 2: Research Applications Enabled by High-SNR Ultra-High Field MRI. This workflow diagram illustrates how the increased SNR available at ultra-high magnetic fields enables mesoscale imaging, which in turn facilitates specific research applications with direct clinical impact.

Advanced Contrast Mechanisms and Multinuclear Imaging

Ultra-high-field MRI extends beyond anatomical imaging to leverage novel contrast mechanisms and multinuclear spectroscopy:

- Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging (SWI): Sensitivity to susceptibility effects scales with B0, dramatically improving visualization of venous microvasculature, microbleeds, and iron deposits [1]

- Time-of-Flight Angiography: The combination of higher SNR and longer T1 values at 7T enhances background suppression, increasing vessel-to-tissue contrast and enabling visualization of smaller arterial branches [1]

- MR Spectroscopic Imaging: Spectral separation of metabolite peaks increases linearly with B0, improving quantification of neurotransmitters and metabolic markers in disorders like brain tumors [1]

- Multinuclear Imaging: SNR gains make non-proton nuclei (²³Na, ³¹P) accessible, providing insights into cellular energetics and ion homeostasis in pathological states [1]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Hardware and Methodological Components for High-Resolution Neuroimaging Research

| Component | Function/Role | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density Receiver Coils | Increase signal reception proximity to cortex | Maximize SNR for cortical surface imaging |

| High-Performance Gradients | Enable faster spatial encoding | Reduce distortion in EPI; enable high-resolution DTI |

| Parallel Transmission Systems | Mitigate B1+ inhomogeneity at UHF | Improve image uniformity in body regions |

| Motion Correction Systems | Enable long acquisitions without degradation | Facilitate ultra-high resolution (<0.5 mm) imaging |

| Deep Learning Super-Resolution | Enhance lower-field images computationally | Harmonize multi-site data (1.5T→3T quality) [8] |

| Adiabatic RF Pulses | Overcome B1+ inhomogeneity | Accurate spectral localization in MRSI [1] |

In the realms of neuroimaging, oncology, and drug development, the precise definition of spatial sampling scale—determined by the interplay between spatial resolution and voxel volume—fundamentally shapes the interpretation of biological phenomena. Spatial resolution defines the smallest distinguishable distance between two points, while voxel volume represents the three-dimensional pixel size that constitutes the fundamental unit of digital image data. These parameters establish the boundaries of what can be observed and quantified across macroscopic to mesoscopic biological scales, directly impacting the detection of pathological changes, assessment of therapeutic efficacy, and validation of drug targets. For researchers and pharmaceutical developers, the selection of imaging parameters represents a critical tradeoff between field of view, sampling granularity, signal-to-noise ratio, and practical constraints. This guide objectively compares the performance of high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) against standard-resolution approaches, supported by experimental data quantifying their differential impacts on measurement accuracy, biological specificity, and clinical relevance.

Technical Foundations: Voxel Geometry and Its Biological Interpretation

Fundamental Principles of Voxel-Based Sampling

In medical imaging, a voxel (volume pixel) represents the smallest unit of a three-dimensional image, with dimensions defined by field of view, matrix size, and slice thickness according to the relationship: Voxel Volume = (Field of View / Matrix Size) × Slice Thickness [9]. This geometric definition establishes the fundamental sampling scale that governs the detection and quantification of biological structures. The partial volume effect occurs when a single voxel contains multiple tissue types, resulting in a signal average that obscures anatomical boundaries and reduces measurement accuracy [10]. This effect becomes particularly problematic when voxel dimensions approach or exceed the size of structures under investigation, such as small brain nuclei or thin cortical layers.

The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in MRI maintains an inverse relationship with voxel size at fixed acquisition times, creating a fundamental tradeoff that imaging protocols must optimize for specific applications [11]. While smaller voxels provide finer spatial resolution, they simultaneously reduce SNR, potentially obscuring subtle contrast differences in soft tissues. Furthermore, voxel geometry—whether isotropic (equal dimensions in all axes) or anisotropic (unequal dimensions)—significantly impacts the accuracy of volumetric measurements and edge detection, particularly for small, complex anatomical structures [10].

Biological Context Determines Optimal Voxel Parameters

The optimal voxel size varies substantially across biological applications, with different structures imposing distinct resolution requirements as summarized in Table 1. For instance, the subthalamic nucleus and internal globus pallidus—key targets for deep brain stimulation in Parkinson's disease—exhibit post-mortem volumes of approximately 130mm³ and 377mm³ respectively [10]. To ensure deviations remain within an acceptable range (Dice coefficient > 0.75), simulation studies indicate that isotropic voxel volumes should not exceed 5% of the total structure volume [10]. Similar considerations apply to cortical layer imaging, where high-resolution 4D vascular space occupancy (VASO) MRI at 7 Tesla employs submillimeter resolution to distinguish microvascular volumetric pulsatility across six cortical layers [12].

Figure 1: Fundamental relationships between imaging parameters and data quality. Voxel volume is determined by acquisition parameters, which collectively influence spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio. These factors subsequently impact critical image quality metrics relevant to biological interpretation.

Comparative Performance: High-Resolution vs. Standard MRI

Tissue Specificity Across Resolution Scales

Table 1: Performance Comparison of MRI Resolution Scales Across Biological Contexts

| Biological Context | Standard Resolution (Typical Parameters) | High Resolution (Typical Parameters) | Quantifiable Impact on Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cortical Layer Analysis | 1mm isotropic voxels [13] | 0.6-0.8mm isotropic at 7T [12] | Enables differentiation of 6 cortical layers with distinct microvascular pulsatility profiles (mvPI: 0.18±0.04 in pial mater vs. 0.08±0.02 in middle layers) [12] |

| Small Brain Nuclei (STN/GPi) | 1mm³ isotropic [10] | 0.6-0.8mm isotropic [10] | Dice similarity coefficients decline from >0.9 to <0.75 when voxel volume exceeds 5% of structure volume [10] |

| Vestibular Schwannoma Volumetry | 1.2×0.9×4.0mm anisotropic [9] | 0.5×0.5×0.8mm isotropic [9] | Segmentation accuracy decreases by 22-35% with larger voxels; AI-based methods outperform manual segmentation at all resolutions [9] |

| Microvascular Pulsatility | Limited to large vessels [12] | 0.75mm isotropic 4D VASO at 7T [12] | Reveals laminar mvPI gradient from pial surface (0.18±0.04) to white matter (0.06±0.02); detects aging effects in deep WM (P=0.006) [12] |

| Multisite VBM Studies | 1-1.5mm isotropic [13] | 0.8-1mm isotropic [13] | Pipeline choice alone alters location of reported group differences; only 10.98% spatial overlap in sex differences across 4 pipelines [13] |

Quantitative Impacts on Measurement Accuracy

The transition from standard to high-resolution imaging produces quantifiable improvements in measurement precision across diverse applications. In neurofibromatosis type 2-related schwannomatosis (NF2-SWN), vestibular schwannoma volumetry demonstrates significantly improved accuracy with smaller voxel dimensions. A systematic evaluation of segmentation performance across varying voxel sizes revealed that larger voxels (1.2 × 0.9 × 4.0 mm) reduced segmentation accuracy by 22-35% compared to high-resolution acquisitions (0.5 × 0.5 × 0.8 mm), with AI-based segmentation outperforming manual methods particularly at coarser resolutions [9]. These findings highlight the critical importance of voxel optimization for longitudinal tumor monitoring in clinical trials.

In cerebral microvasculature imaging, high-resolution 4D vascular space occupancy (VASO) at 7 Tesla enables quantification of microvascular volumetric pulsatility index (mvPI) across cortical layers—a measurement inaccessible to standard-resolution approaches [12]. This technique reveals a pronounced laminar gradient in mvPI, with highest values at the pial surface (0.18 ± 0.04) that progressively decrease through gray matter to white matter. Critically, this spatial resolution enables detection of aging-related changes, demonstrating significantly elevated deep white matter mvPI in older participants (P = 0.006) [12]. Furthermore, the method reveals territory-specific pulsatility patterns, with middle cerebral artery regions exhibiting higher mvPI than anterior or posterior cerebral artery territories across cortical layers [12].

The reproducibility of voxel-based morphometry (VBM) findings exhibits pronounced dependency on processing pipelines, with substantial variability introduced by software choices alone. A systematic comparison of four commonly used VBM pipelines (CAT, FSLVBM, FSLANAT, sMRIPrep) revealed generally low spatial similarity between processed gray matter maps from the same participants across different pipelines [13]. When examining sex differences, only 10.98% spatial overlap was observed across all four pipelines at a conventional cluster-level threshold (pFWE < 0.05), indicating that analytical choices alone can substantially alter the anatomical localization of reported group differences [13].

Experimental Protocols for Resolution-Specific Validation

High-Resolution Microvascular Pulsatility Mapping

The protocol for assessing cerebral microvascular volumetric pulsatility employs high-resolution 4D VASO MRI at 7 Tesla with simultaneous pulse recording to achieve the necessary spatiotemporal resolution for microvascular assessment [12]. The methodology involves several critical stages:

Image Acquisition: Implement 0.75mm isotropic resolution using a 3D turbo-FLASH (TFL) pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling (pCASL) sequence at 7 Tesla with cardiac synchronization to resolve pulsatility across the cardiac cycle [12].

Tissue Segmentation: Derive laminar profiles from T1-weighted MRI, segmenting gray matter into six equi-volume layers from superficial to deep, plus separate pial mater and superficial white matter layers. Deep white matter regions are obtained by subtracting superficial white matter from total white matter [12].

Hemodynamic Calculation: Compute cerebral blood flow (CBF) from ASL data, then estimate baseline cerebral blood volume (CBV0) using the relationship CBV0 = CBF × arterial transit time. Calculate CBV changes across cardiac cycles (ΔCBV = CBVmax - CBVmin) from VASO signals [12].

Pulsatility Quantification: Derive microvascular volumetric pulsatility index (mvPI) as mvPI = ΔCBV / CBV0, representing the fractional volume change of microvasculature between systolic and diastolic phases [12].

Validation: Perform test-retest scans with long intervals (3-8 months), non-parametric reliability testing, and simulations to demonstrate reproducibility and accuracy [12].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for high-resolution microvascular pulsatility mapping. This protocol enables layer-specific quantification of volumetric pulsatility across cardiac cycles, revealing gradients inaccessible to standard-resolution approaches.

Voxel Size Impact Assessment in Tumor Volumetry

The systematic evaluation of voxel size effects on segmentation accuracy employs a resampling approach to quantify performance degradation across resolution scales [9]:

Subject Population: Include patients with NF2-SWN with vestibular schwannomas, acquiring high-resolution T1 post-contrast MRI scans as ground truth reference.

Multi-resolution Simulation: Use linear interpolation to resample original high-resolution images (e.g., 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.8 mm) to progressively larger voxel sizes (0.8 × 0.8 × 0.9 mm, 0.8 × 0.8 × 1.6 mm, and 1.2 × 0.9 × 4.0 mm) representing clinically common protocols [9].

Segmentation Methods: Apply both manual segmentation by trained researchers (with neuroradiologist review) and AI-based auto-segmentation using convolutional neural networks to all resolution levels.

Accuracy Quantification: Calculate percentage volume change relative to original high-resolution segmentation, Dice similarity coefficients for spatial overlap, and Hausdorff distances for boundary agreement [9].

Statistical Analysis: Employ Wilcoxon signed-rank tests to compare segmentation performance across voxel sizes and between methods (AI vs. manual), with visualization using R ggplot2 and tidyverse packages [9].

Implementation Framework for Research and Development

Research Reagent Solutions for High-Resolution Imaging

Table 2: Essential Research Materials and Analytical Tools for Resolution-Specific Studies

| Category | Specific Solution | Research Application | Performance Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging Hardware | 7 Tesla MRI Scanner | Ultra-high field imaging for cortical layer analysis [12] | Enables <0.8mm isotropic resolution; essential for microvascular pulsatility mapping |

| Pulse Sequences | 3D turbo-FLASH (TFL) pCASL | Cerebral blood flow and volume quantification [12] | Provides 0.75mm isotropic resolution with cardiac synchronization |

| Segmentation Software | Simpleware (Synopsys) | Manual and AI-based tumor volumetry [9] | "Paint by Threshold" tool with AI auto-segmentation capability |

| Voxel-Based Morphometry | CAT12 (SPM), FSLVBM, FSLANAT, sMRIPrep | Gray matter volume analysis [13] | Pipeline choice significantly affects results; CAT shows higher within-pipeline homogeneity |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Visium HD, Xenium, MERFISH | Spatial gene expression correlation with imaging [14] | 55μm to subcellular resolution; bridges molecular and structural analysis |

| Motion Quantification | Voxel Volume Overlap (VVO) | Motion artifact assessment in fMRI [15] | Voxel-size sensitive motion metrics; superior to traditional displacement parameters |

Integration Guidelines for Drug Development Applications

The implementation of resolution-optimized imaging in pharmaceutical research requires strategic consideration of multiple factors:

Target Structure Dimensions: Match voxel volume to biological scale of interest, ensuring isotropic voxels do not exceed 5% of total structure volume for acceptable accuracy (Dice > 0.75) [10]. For small nuclei (<150mm³), this typically requires submillimeter isotropic resolution.

Longitudinal Sensitivity: Optimize SNR-resolution tradeoff for detection of subtle change over time. For vestibular schwannoma monitoring, high-resolution protocols (0.5 × 0.5 × 0.8 mm) significantly improve growth detection sensitivity compared to clinical standard acquisitions [9].

Multimodal Correlation: Integrate high-resolution MRI with emerging spatial transcriptomics technologies like Visium HD (55μm resolution) or Xenium (subcellular) to bridge imaging findings with molecular mechanisms in drug target validation [14].

Analytical Consistency: Standardize VBM processing pipelines across multi-site trials to minimize software-introduced variability, as pipeline differences can alter the anatomical localization of reported group differences [13].

Motion Management: Implement voxel-volume-overlap (VVO) metrics rather than traditional displacement parameters for motion quantification in high-resolution functional studies, as motion effects are highly dependent on voxel dimensions [15].

The comparative analysis of high-resolution versus standard MRI establishes that voxel volume and spatial resolution parameters fundamentally constrain biological interpretation across research and drug development applications. High-resolution approaches (0.5-0.8mm isotropic) at 7 Tesla provide unprecedented access to laminar architecture, microvascular dynamics, and small structure volumetry, enabling detection of subtle pathological changes and aging effects inaccessible to standard protocols. However, these advances require careful optimization of the SNR-resolution tradeoff and standardized analytical pipelines to ensure reproducible findings. For pharmaceutical researchers, the strategic selection of voxel parameters should be guided by target biology, required measurement precision, and integration with complementary spatial molecular technologies. As imaging continues to evolve toward mesoscopic scales, the precise definition of sampling volume remains foundational to accurate biomarker quantification and therapeutic efficacy assessment.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at high magnetic field strengths offers a powerful window into tissue microstructure and composition by leveraging intrinsic contrast mechanisms. Unlike methods relying on external contrast agents, techniques such as T1 mapping, T2* imaging, and quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) derive contrast from the inherent magnetic properties of biological tissues themselves [16] [17]. The strength of these signals is significantly enhanced at higher fields (e.g., 3 Tesla and above), providing improved signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) crucial for resolving fine anatomical details [18] [17]. This guide objectively compares these core intrinsic contrast mechanisms, framing them within ongoing research on high-resolution MRI for superior tissue specificity, with particular relevance for neuroscience and drug development.

Core Principles of Intrinsic Contrast Mechanisms

Intrinsic MRI contrast originates from how tissue water protons interact with their local molecular environment following radiofrequency excitation in a magnetic field. The signal is governed by several key physical processes, each providing unique biological information.

- T1 (Longitudinal Relaxation): T1 relaxation time represents the rate at which protons recover their magnetization along the main magnetic field (B0) after excitation. It is sensitive to the presence of macromolecules like proteins and lipids, with myelin content being a primary determinant in the brain [19] [20].

- T2* (Effective Transverse Relaxation): T2* reflects the rate of signal decay due to a combination of static magnetic field inhomogeneities (spin-spin relaxation and local magnetic susceptibilities) and true T2 relaxation [19] [17]. It is particularly sensitive to paramagnetic substances such as iron stored in ferritin and deoxyhemoglobin in venous blood [19] [17].

- Magnetic Susceptibility (χ): Magnetic susceptibility is a fundamental property of a material that quantifies its degree of magnetization in response to an external magnetic field. In tissues, variations in susceptibility arise from differences in the concentration of diamagnetic (e.g., myelin, calcium) and paramagnetic (e.g., iron, deoxygenated blood) components [16] [17]. Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping (QSM) is a dedicated technique to map this property in three dimensions by solving an inverse problem from the magnetic field map derived from MRI phase images [16].

The following diagram illustrates the core principles and primary tissue sources of these three intrinsic contrast mechanisms.

Comparative Analysis of T1, T2*, and Magnetic Susceptibility

The following table provides a direct, data-driven comparison of the three intrinsic contrast mechanisms, summarizing their biophysical basis, primary applications, key advantages, and inherent limitations for tissue characterization.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of intrinsic MRI contrast mechanisms at high field

| Feature | T1 Mapping | T2* Mapping | Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping (QSM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biophysical Basis | Longitudinal recovery of proton magnetization; sensitive to interactions with macromolecules/lattice [20]. | Signal decay from spin-spin interactions & local magnetic field inhomogeneities [19]. | Quantifies tissue bulk magnetic susceptibility from magnetic field perturbations [16]. |

| Primary Tissue Sources | Myelin content, water-bound macromolecules [19]. | Tissue iron (ferritin), deoxygenated blood (deoxyhemoglobin) [19] [17]. | Paramagnetic iron (ferritin, hemosiderin), diamagnetic myelin & calcium [16] [17]. |

| Key Applications | Tissue segmentation (GM/WM/CSF), detection of cortical lesions, myelin quantification [19]. | Detection of cerebral microbleeds, venous vasculature imaging, BOLD fMRI [21] [19]. | Differentiating iron from myelin, quantifying iron deposition, mapping brain oxygen extraction [16] [17]. |

| Advantages at High Field | Improved SNR, better grey-white matter contrast [18]. | Stronger susceptibility effects, enhanced CNR for veins and iron [17]. | Increased contrast-to-noise, superior quantification of susceptibility sources [16] [17]. |

| Limitations/Challenges | Sensitive to RF transmit field (B1+) inhomogeneities [19]. | Sensitive to B0 inhomogeneity; signal loss in regions near air/tissue interfaces [21]. | Ill-posed inverse problem requiring sophisticated processing; streaking artifacts [16]. |

Experimental Protocols for Simultaneous Multi-Parametric Mapping

Advanced MRI sequences now enable the simultaneous acquisition of T1, T2*, and magnetic susceptibility maps within a single, time-efficient scan, ensuring perfect spatial co-registration of parameters. Below are detailed methodologies for two prominent approaches.

Multi-Echo MP2RAGE (ME-MP2RAGE)

The ME-MP2RAGE sequence combines the B1+-insensitive T1 mapping of the standard MP2RAGE sequence with a multi-echo readout to simultaneously capture T2* and susceptibility data [19].

Detailed Protocol [19]:

- Pulse Sequence: A magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo sequence featuring an adiabatic inversion pulse followed by two separate GRE readout blocks.

- Multi-Echo Readout: Each GRE block acquires multiple gradient echoes (e.g., 4-6 echoes) at different echo times (TEs) after a single radiofrequency excitation.

- Key Parameters (7T Example):

- Resolution: Up to 0.6 mm isotropic nominal resolution.

- Readout: Echo times (TEs) are distributed across the readout to adequately sample the T2* decay curve.

- Inversion Times: TI,1 and TI,2 are optimized for robust T1 fitting at the target field strength.

- Data Processing:

- T1 Map: Calculated from the two images acquired at inversion times TI,1 and TI,2 using the standard MP2RAGE signal model [19].

- T2* Map: Obtained by fitting the signal decay across the multiple echo times within each readout block to a mono-exponential decay model.

- Susceptibility Map (QSM): The phase data from the multi-echo readout is used to compute a field map, which is then processed using QSM algorithms (e.g., threshold-based k-space division or regularized inversion) to yield a quantitative susceptibility map [16] [19].

- Acquisition Time: Approximately 19 minutes for a whole-brain dataset at 7T [19].

MR Multitasking

The MR Multitasking framework provides an alternative method for simultaneous multi-parametric mapping by efficiently capturing data across multiple contrast dimensions.

Detailed Protocol [22]:

- Pulse Sequence: Utilizes hybrid T2-prepared inversion-recovery pulse modules combined with multi-echo GRE readouts.

- Data Structure: The underlying image is represented as a six-dimensional low-rank tensor, encompassing three spatial dimensions and three temporal dimensions corresponding to T1 recovery, T2 decay, and multi-echo T2* behavior.

- Key Parameters:

- Scan Time: A single 9.1-minute scan for whole-brain coverage.

- Outputs: Co-registered quantitative maps of T1, T2, T2*, and magnetic susceptibility.

- Data Processing: The high-dimensional data is reconstructed and then fitted using a dictionary-based or model-based approach to generate the final parametric maps.

- Validation: Phantom studies have shown substantial consistency with reference methods (R² > 0.98) [22].

The workflow for these simultaneous mapping techniques, from data acquisition to the generation of quantitative maps, is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of high-field intrinsic contrast imaging requires both specific hardware and specialized software tools.

Table 2: Essential materials and tools for high-field intrinsic contrast research

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| High-Field MRI Scanner (≥3T) | Provides the foundational high magnetic field necessary for enhanced SNR and CNR, making subtle susceptibility and relaxation contrasts detectable [18] [17]. |

| Multi-Channel RF Coils | Advanced coil arrays are critical for parallel imaging, which accelerates data acquisition and increases SNR, enabling high-resolution studies within feasible scan times. |

| Optimized Pulse Sequences | Prototype or product sequences like ME-MP2RAGE [19] and MR Multitasking [22] are essential for efficient, simultaneous multi-parametric data collection. |

| Gadolinium-Based Contrast Agents | Used in Dynamic Susceptibility Contrast (DSC) perfusion studies, which exploit T2* effects to measure cerebral blood volume and flow [23]. A preload is often used to minimize T1 leakage effects in tumor studies [23]. |

| Phantom Validation Kits | Materials with known relaxation times and magnetic susceptibilities are indispensable for validating the accuracy and quantifying the performance of mapping sequences [22] [19]. |

| QSM Reconstruction Software | Specialized software (e.g., MEDI, STAR-QSM) is required to solve the ill-posed inverse problem in QSM, involving steps like phase unwrapping, background field removal, and dipole inversion [16]. |

The intrinsic contrast mechanisms of T1, T2, and magnetic susceptibility provide a powerful, non-invasive toolkit for characterizing tissue microstructure at high magnetic field strengths. T1 mapping offers insights into myelin and macromolecular structure, T2 is sensitive to iron and blood oxygenation, and QSM allows for the precise quantification of tissue magnetic susceptibility, helping to disentangle the contributions of iron and myelin. While each mechanism has distinct strengths and limitations, the development of integrated sequences like ME-MP2RAGE and MR Multitasking enables the efficient acquisition of co-registered multi-parametric maps. This comprehensive quantitative approach is proving invaluable in both basic neuroscience research and the development of new therapeutic agents, providing robust imaging biomarkers for tissue characterization in health and disease.

The human brain functions through intricately organized neural circuits that operate at a scale finer than whole brain regions but larger than individual neurons. This intermediate level, known as the mesoscale, encompasses cortical layers, columns, and fine anatomic structures that form the fundamental processing units of cognition. For decades, the investigation of these structures in living humans remained largely inaccessible, trapped between the resolution limits of non-invasive macroscale imaging and the invasive nature of microscopic techniques. The mesoscale represents a critical gap in our understanding, as it is precisely at this level that functional specialization emerges through specific laminar and columnar architectures.

The development of ultra-high field Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) systems, particularly 7 Tesla (7T) scanners and beyond, has begun to bridge this methodological divide. This comparison guide objectively examines the capabilities of current mesoscale imaging technologies, focusing specifically on how high-resolution MRI compares against standard resolution approaches in resolving cortical layers, columns, and fine anatomical structures. We present quantitative performance data, detailed experimental protocols, and analytical frameworks that enable researchers to select appropriate methodologies for investigating the brain's mesoscale organization, with significant implications for basic neuroscience and drug development programs targeting specific neural circuits.

Technical Specifications and Performance Comparison

Resolution and Hardware Capabilities

The pursuit of mesoscale imaging has driven innovations in MRI hardware to overcome the inherent signal-to-noise and spatial encoding limitations of conventional systems. The table below compares the key performance characteristics of a standard 7T system, a next-generation 7T system, and a 9.4T experimental system.

Table 1: Performance comparison of MRI systems for mesoscale imaging

| System Component | Standard 7T Scanner | Next-Gen 7T Scanner | 9.4T Experimental System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Gradient Strength | 80 mT/m | 200 mT/m | Not specified |

| Maximum Slew Rate | 200 T/m/s | 900 T/m/s | Not specified |

| Receiver Channels | 32-channel | 128-channel (96-ch Rx coil) | Not specified |

| Typical fMRI Resolution (Isotropic) | 0.8-1.0 mm | 0.35-0.45 mm | 0.35 mm (demonstrated) |

| Cortical SNR Improvement | Baseline | ~30% in cortex | High (specifics not provided) |

| Key Limitations | PNS limits, lower SNR in cortex | Acoustic noise, specialized design | Limited availability, technical challenges |

The next-generation 7T scanner exemplifies the hardware advances required for mesoscale imaging, featuring a head-only asymmetric gradient coil with an additional third layer of windings that enables dramatically improved performance—200 mT/m maximum gradient strength and 900 T/m/s slew rate compared to 80 mT/m and 200 T/m/s in standard 7T systems [4]. This enhanced gradient performance directly enables higher spatial resolution by permitting shorter echo spacing (0.58 ms at 0.6 mm isotropic versus 1.21 ms with standard gradients), which reduces T2* blurring and geometric distortion [4]. Furthermore, the increased channel count in receiver systems (up to 128 channels versus standard 32-channel arrays) with smaller coil elements (~4 cm diameter) significantly boosts signal in the cerebral cortex while reducing g-factor noise for accelerated acquisitions [4].

Functional and Structural Resolution Comparison

The improved hardware capabilities directly translate to enhanced performance in functional and structural imaging of mesoscale structures, as quantified in the table below.

Table 2: Mesoscale structure imaging capabilities comparison

| Imaging Target | Standard Resolution (3T/7T) | High Resolution (7T+) | Biological Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ocular Dominance Columns (ODCs) | Not resolvable | Localized with 1 mm isotropic fMRI [24] | 0.7-1.0 mm width in humans |

| V2 Thin/Thick Stripes | Indirect inference only | Direct mapping at 0.8 mm isotropic [25] | 1.5-2.0 mm width in humans |

| Cortical Layers | Partial depth sampling | Full laminar profiling across all layers | 1.5-4.5 mm total thickness |

| Hippocampal Subfields | Limited by partial volume effects | Subfield differentiation possible [26] | <2 mm for most subfields |

| Functional Connectivity | Between regions | Between columns and layers [24] | Horizontal fibers span up to 8 mm |

The functional imaging advances are particularly notable. High-resolution fMRI at 7T can now resolve ocular dominance columns (ODCs) in human primary visual cortex using 1 mm isotropic resolution, demonstrating stronger functional connectivity between columns of similar ocular polarity—a finding consistent with anatomical studies in animals but previously unobservable in humans [24]. In the secondary visual cortex (V2), functional mapping of thin and thick stripes has been achieved using 0.8 mm isotropic resolution by exploiting their differential sensitivity to color and binocular disparity, respectively [25]. Quantitative MRI techniques applied at these resolutions can subsequently probe microstructural differences between these functional compartments, revealing lower longitudinal relaxation rates (R1) in thin and thick stripes compared to pale stripes—indicative of higher myelination in the latter [25].

Experimental Protocols for Mesoscale Imaging

Functional Mapping of Cortical Columns

The reliable identification of cortical columns requires specialized experimental paradigms that exploit known functional specializations. For ODC mapping, dichoptic stimulation protocols present different visual inputs to each eye separately [24]. The subsequent analysis employs an ocular dominance index (ODI) to quantify voxel-wise preference for one eye over the other. In resting-state paradigms, functional connectivity between voxels can be analyzed as a function of their ocular preference, revealing stronger correlations between similarly-tuned columns even over distances up to 35 mm—far exceeding the reach of single horizontal fibers [24].

For V2 stripe mapping, color-selective thin stripes are localized using isoluminant color stimuli compared to luminance-matched achromatic stimuli, while disparity-selective thick stripes are identified using stimuli with varying binocular disparity [25]. The resulting activation patterns show the characteristic stripe-like organization running perpendicular to the V1/V2 border, with center-to-center distances of approximately 4-8 mm in humans. The robustness of these functional maps can be confirmed through test-retest reliability across multiple scanning sessions [24].

Cortical Depth and Laminar Analysis

Mesoscale imaging necessitates specialized cortical sampling strategies to resolve depth-dependent organization. The cortical grid approach provides advantages over standard surface meshes for local applications by creating regular 2D grids directly in gray matter at specified spatial resolutions [27] [28]. This method better reflects local distances and angles when quantitatively analyzing functional data, as each vertex is surrounded by four neighbors at constant distances with 90-degree angles between edges—unlike the variable geometry of standard triangulated meshes [27].

Two primary approaches exist for defining cortical depth:

- Equidistant sampling: Places surfaces at equal distances between white matter and pial boundaries, preserving geometric distance but varying the volume of tissue represented at different depths [27] [28].

- Equi-volume sampling: Adjusts depth level spacing to preserve the volume of tissue represented within each surface, accounting for the changing surface area through the cortical ribbon [27] [28].

Current evidence suggests that equi-volume sampling yields a slight advantage over equidistant sampling given limitations in fMRI voxel size, participant motion, coregistration, and segmentation accuracy [27] [28]. This approach particularly improves the correspondence between functional activation profiles and underlying laminar anatomy.

Acquisition Sequences for High-Resolution fMRI

Achieving mesoscale resolution requires specialized acquisition sequences that balance spatial resolution, signal-to-noise ratio, and imaging speed. The 3D Echo Planar Time- and Dynamic-resolved Imaging (TIDY) sequence represents a recent advancement that addresses key challenges in high-resolution fMRI [29]. This approach leverages a multi-dimensional encoding design with time- and dynamic-resolved reconstruction to achieve distortion-free fMRI at ultra-high spatiotemporal resolutions, enabling whole-brain coverage at 500 μm isotropic resolution with 885 ms volume TR, or partial-brain imaging at 340 μm isotropic resolution [29].

For laminar fMRI, the choice of contrast mechanism is crucial. While traditional gradient-echo BOLD remains widely used, its sensitivity to large venous structures can introduce vascular biases. Recent simulations suggest that small voxel sizes (<0.8 mm) reduce extravascular dephasing from large veins in gradient-echo BOLD at 7T, potentially improving neuronal specificity [30]. Alternative approaches include VASO (Vascular Space Occupancy), which aims to suppress blood signal to enhance specificity to parenchymal tissue, though it suffers from lower SNR that can be mitigated with denoising techniques like NORDIC [30].

Table 3: Essential research reagents and resources for mesoscale imaging

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultra-High Field Scanners | 7T MRI with high-performance gradients; 9.4T experimental systems | Provide fundamental SNR and resolution for mesoscale studies | Gradient performance (strength, slew rate) determines practical resolution limits |

| Multi-Channel Receiver Coils | 64-channel head coils; 96-channel arrays | Increase SNR in cerebral cortex and enable parallel imaging acceleration | Smaller coil elements (~4cm) improve cortical signal [4] |

| Cortical Analysis Tools | FreeSurfer; CBS High-Res Brain Processing Tools | Surface reconstruction, cortical depth sampling, and alignment | Regular grid approaches advantageous for quantitative spatial analysis [27] |

| Pulse Sequences | 3D TIDY-EPI; Multi-echo GRE; VASO | Optimized acquisition for high-resolution fMRI | Balance resolution, distortion, and SNR; TIDY enables distortion-free sub-0.5mm imaging [29] |

| Quantitative MRI Protocols | Multi-parameter mapping (MPM); Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping (QSM) | Derive microstructural parameters (R1, R2*, MWF) related to myelin and iron | R1 values serve as myelin surrogate; can differentiate V2 stripe types [25] |

Data Analysis Frameworks and Computational Tools

Analytical Approaches for Columnar and Laminar Signals

The analysis of mesoscale fMRI data presents unique challenges that require specialized approaches. For laminar fMRI, layer-dependent regional homogeneity (ReHo) provides a model-free method for characterizing mesoscale functional structure across layers and columns without requiring predefined regions of interest [30]. This technique measures local, short-distance time course similarities across cortical depth, generating depth-dependent similarity matrices that can quantify laminar separability in high-resolution fMRI data [30].

The analysis of functional connectivity between cortical columns requires careful consideration of distance effects and ocular preference. Studies of ODC connectivity typically bin vertex pairs by distance and compare functional correlation strength between those with alike versus unalike ocular polarity [24]. A consistent finding shows that while functional connectivity decreases with distance, the selectivity for similarly-tuned columns persists across relatively long distances (up to 35 mm) without significant interaction between distance and selectivity effects [24].

Validation Approaches and Multi-Modal Correlation

A critical challenge in mesoscale imaging is the validation of inferred neural features against ground truth histological methods. The CLARITY tissue clearing technique provides one validation pathway by enabling 3D mapping of fluorescently labeled neurofilaments and vasculature throughout intact tissue samples [31]. Comparisons between diffusion MRI fiber orientation estimates and CLARITY neurofilament orientations in human thalamic samples show mean angular differences of approximately 19°±15°, supporting the validity of dMRI for mesoscale structural mapping [31]. This multi-modal validation approach is particularly valuable for establishing the biological specificity of MRI-based mesoscale measurements.

For hippocampal subfield imaging, methodological considerations become particularly important due to the small size of these structures. While anatomical segmentation based on cytoarchitectonic probabilistic atlases is widely used, current imaging resolution at 3T makes it difficult to avoid partial volume effects for layers less than 2 mm thick [26]. Alternative functional segmentation approaches based on the anterior-posterior axis of the hippocampus may better reflect the structure's functional and molecular heterogeneity, though this remains an area of active methodological development [26].

The quest for mesoscale imaging has transformed from a technological aspiration to an achievable scientific enterprise with the advent of ultra-high field MRI systems and specialized acquisition methodologies. The performance comparisons presented in this guide demonstrate that next-generation 7T scanners with high-performance gradients and multi-channel receiver arrays now provide sufficient resolution and signal-to-noise ratio to resolve cortical layers, columns, and fine anatomical structures that were previously accessible only through invasive methods in animal models or post-mortem human tissue.

The implications for research and drug development are substantial. Mesoscale imaging enables the in vivo investigation of circuit-level pathologies in neurological and psychiatric disorders, potentially identifying novel biomarkers and treatment targets. The ability to track laminar-specific activity patterns may illuminate pathological information flow in conditions such as schizophrenia, while columnar-level functional connectivity mapping could reveal circuit disruptions in autism spectrum disorders. As these technologies continue to evolve, with even higher field systems (10.5T, 11.7T) under development and increasingly sophisticated analysis tools emerging, the mesoscale frontier in human neuroscience is poised to yield transformative insights into brain organization in health and disease.

Hardware Innovations and Imaging Techniques Powering Specificity in Research and Clinical Trials

Advancements in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are fundamentally reshaping neuroscience and drug development research by enabling the visualization of the human brain at an unprecedented scale. Traditional fMRI studies typically operate at spatial resolutions around 3.0 mm isotropic, sufficient for mapping broad functional territories but inadequate for deciphering the brain's fine-grained mesoscale circuitry—the level of cortical layers and columns that form the essential architecture of neural computation [4]. To bridge this gap, researchers require a significant leap in spatial resolution, down to 0.3–0.6 mm, which demands a comprehensive re-engineering of MRI hardware, particularly the gradient coils responsible for spatial encoding [4]. This guide objectively compares a key innovation in this domain—asymmetric head gradient coils—against standard alternatives, providing researchers with the experimental data and methodological context needed to evaluate their potential for high-resolution tissue specificity research.

Hardware Showdown: Quantitative Performance Comparison

Gradient Coil Performance Specifications

Next-generation asymmetric head gradient coils represent a radical departure from conventional whole-body and symmetric head coil designs. Unlike symmetric coils, which place the region of interest (ROI) at the geometric center, asymmetric coils shift the ROI toward one end (e.g., the patient end) to better accommodate the human head and shoulders while maximizing performance within limited space [32]. This configuration, often featuring novel designs like connected primary and shielding layers at one end, allows for more efficient wire patterns, improved cooling system access, and superior electromagnetic performance [33] [32].

The following table summarizes the performance characteristics of key gradient coil designs, highlighting the transformative potential of asymmetric head coils.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of MRI Gradient Coils

| Gradient Coil Model / Type | Maximum Strength (Gmax in mT/m) | Maximum Slew Rate (SR in T/m/s) | Key Application / Distinguishing Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Whole-Body (SC72) [4] | 80 | 200 | Clinical whole-body imaging; baseline for comparison |

| Head-Only Asymmetric (AC84) [4] | 80 | 400 | Early high-performance head imaging |

| NexGen 'Impulse' Asymmetric Head Coil [4] | 200 | 900 | Ultra-high-resolution human brain imaging (0.35-0.45 mm) |

| NeuroFrontier Proposed Head Coil [34] | 650 | 600 | Ultra-high-gradient neuroimaging; highest reported Gmax |

| Typical Head Gradient Benefit [35] | Higher than whole-body | Higher than whole-body | Reduced PNS limitations, enabling faster switching |

Imaging Performance and Outcomes

The performance gains translate directly into superior imaging capabilities. The core advantage lies in the ability to generate stronger magnetic field gradients (Gmax) and switch them more rapidly (slew rate). This directly enhances the spatial and temporal encoding processes at the heart of MRI.

Table 2: Experimental Imaging Outcomes with High-Performance Gradients

| Performance Metric | Standard Whole-Body Gradient (SC72) | Next-Gen Asymmetric Head Gradient ('Impulse') |

|---|---|---|

| Achievable Isotropic Resolution (EPI) [4] | 0.7 mm | 0.45 mm |

| Echo Spacing (EPI at 0.5 mm) [4] | 1.41 ms | 0.68 ms |

| Minimum TE (EPI at 0.5 mm) [4] | ~45 ms (∼40% signal loss) | ~23 ms (minimal signal loss) |

| Point Spread Function (PSF) [4] | Larger blurring at high resolution | Smaller blurring, maintains integrity up to ~0.5 mm |

| Geometric Distortion [4] | Higher due to longer echo spacing | Reduced due to shorter echo spacing |

| g-factor Noise Penalty [4] | Higher with 32-channel array | Lower with 64-/96-channel arrays, enabling higher acceleration |

Experimental Deep Dive: Methodology and Protocols

Characterizing Peripheral Nerve Stimulation (PNS) Thresholds

A critical physiological constraint of high-performance gradients is PNS, which causes involuntary muscle twitches and can limit usable performance. Experimental protocols are essential to safely map these thresholds.

Objective: To empirically determine the PNS thresholds for each gradient axis (X, Y, Z) of a high-performance head coil and investigate the impact of subject position and variability [36].

Methodology:

- Participants: Studies typically involve 20-30 healthy adult volunteers under approved ethical guidelines [36].

- Stimulation Sequence: A train of 128 alternating bipolar trapezoidal pulses (mimicking an EPI readout) is played for each gradient axis separately. The rise time (τ) is varied (e.g., 0.1, 0.22, 0.3, 0.5 ms) while the gradient amplitude is progressively increased until the subject first reports a sensation [36].

- Threshold Definition: The PNS threshold is identified as the lowest gradient amplitude (in mT/m) that elicits a sensation for a given rise time.

- Positioning Variants: The process is repeated with the subject's head positioned at isocenter and then moved in steps (e.g., 2 cm, 4 cm) toward the feet to assess sensitivity to position [36].

Key Findings:

- PNS thresholds can be axis-dependent; for the 'Impulse' coil, the X-axis threshold was significantly lower than predicted by initial models [36].

- Thresholds are sensitive to head position within the coil; the X-axis threshold increased by approximately 20 mT/m per centimeter moved toward the foot end [36].

- Significant inter-subject variability exists, influenced by factors such as age, underscoring the need for robust safety models that incorporate experimental data [36].

The experimental workflow for PNS characterization and its integration into coil design is systematic and multi-staged, as shown below.

Evaluating Ultra-High-Resolution Functional and Diffusion Imaging

The primary application of these coils is pushing the boundaries of resolution in fMRI and diffusion MRI (dMRI).

Objective: To demonstrate the feasibility and advantages of sub-millimeter and sub-0.5 mm isotropic resolution imaging for neuroscience applications [4] [34].

Protocol for High-Resolution fMRI:

- Pulse Sequence: Multi-band or single-shot Echo-Planar Imaging (EPI).

- Spatial Resolution: Acquisition of data at resolutions ranging from 0.8 mm down to 0.35 mm isotropic [4].

- Performance Leverage: The high slew rate of the 'Impulse' coil is used to minimize the echo spacing (ES) and echo time (TE), thereby reducing T2* signal decay and geometric distortion. This enables shorter echo train lengths and less image blurring (a narrower Point Spread Function) [4].

- Outcome Analysis: Visualization of layer-specific functional activity and columnar organization, which is otherwise obscured by partial volume effects at standard resolutions.

Protocol for High-Angular Resolution dMRI:

- Pulse Sequence: Diffusion-weighted EPI or advanced sequences like oscillating gradient spin echo [34].

- Performance Leverage: The very high Gmax (e.g., 200-650 mT/m) enables the application of strong diffusion-sensitizing gradients. This permits the use of very high b-values (e.g., >3000 s/mm²) for better sensitivity to restricted diffusion and short diffusion times for probing smaller cellular structures [34].

- Outcome Analysis: Improved estimation of white matter tract integrity and cortical microstructure, providing enhanced contrast for lesions and more accurate metrics for neurite density and orientation dispersion [34].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ultra-High-Field Neuroimaging

| Tool / Resource | Function & Relevance to High-Resolution Research |

|---|---|

| High-Performance Head Gradient Coil (e.g., 'Impulse', 'NeuroFrontier') | Core hardware providing Gmax > 200 mT/m and SR > 600 T/m/s for sub-millimeter spatial encoding and reduced TE [4] [34]. |

| Ultra-High-Density RF Receiver Array (e.g., 64-, 96-, 128-channel) | Boosts signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in the cerebral cortex and reduces g-factor noise, enabling parallel imaging acceleration to compensate for high-resolution's intrinsic SNR penalty [4]. |

| Multi-Channel RF Transmit System (e.g., 8- or 16-channel) | Improves B1+ field uniformity at ultra-high fields (7T and above), crucial for obtaining homogeneous images across the entire brain at high resolution [4]. |

| AI-Empowered Reconstruction & CS | Artificial Intelligence and Compressed Sensing algorithms enable drastic acceleration of acquisitions by reconstructing high-quality images from highly undersampled data, mitigating the long scan times associated with high-resolution protocols [34]. |

| Optical Motion Tracking System | Provides prospective motion correction in real-time. This is essential for sub-millimeter imaging, where even micron-scale head movements can introduce severe artifacts and obscure subtle biological signals [34]. |

Discussion: Implications for Tissue Specificity and Therapeutic Development

The integration of asymmetric head gradient coils into modern MRI systems marks a pivotal shift from macroscopic to mesoscopic brain mapping. For neuroscientists and drug development professionals, this enhanced resolution directly translates to improved tissue specificity. Researchers can now begin to dissect unique functional or structural profiles within individual cortical layers, which are known to have distinct genetic expression, connectivity, and roles in information processing [4]. In neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's, where pathology may originate in specific layers, or in psychiatry, where circuit-based therapeutics are emerging, this granularity is invaluable.

Furthermore, the ability of ultra-strong gradients to probe tissue microstructure with dMRI provides a non-invasive window into cellular-level changes. For drug developers, this offers a potential biomarker for treatment efficacy, sensitive to alterations in neurite density, axon diameter, or cellularity that precede gross volumetric changes detectable on standard scanners [34]. The relationship between hardware capability and biological insight is a positive feedback loop, driving discovery and therapeutic innovation.

While challenges remain—including managing physiological limits like PNS, acoustic noise, and the high costs associated with these advanced systems—the trajectory is clear. The ongoing innovation in asymmetric and PNS-optimized coil designs, coupled with AI-driven acquisition and analysis, is firmly establishing ultra-high-resolution MRI as an indispensable tool for unlocking the secrets of the human brain and accelerating the pace of therapeutic discovery.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has become the mainstay of human imaging in neuroscience, yet typical studies utilizing isotropic spatial resolution on the order of 3.0 mm (27 μl voxel volume) lack the granularity to explore neural circuits at the scale of cerebral columns and cortical layers [4]. With human cortex thickness varying between 1.5 and 4.5 mm and cortical columnar features being 0.6–1.0 mm, advancing resolution to the mesoscale (0.3–0.6 mm) is essential to adequately sample cortical layers and columns while minimizing partial volume averaging of surrounding tissues [4]. This resolution leap requires substantial improvements in the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which can be achieved through higher magnetic field strengths and advanced radiofrequency (RF) hardware, particularly high-density receiver array coils [4] [37].

Over years, improvements to major MRI scanner system components have led to higher SNR and higher resolution imaging, but such hardware advancements were often developed in isolation [4]. The integration of ultra-high field systems (≥7 Tesla) with dedicated high-performance hardware creates a synergistic effect, pushing the boundaries of what is achievable in human neuroimaging [4]. This review comprehensively examines the role of high-density receiver array coils in advancing cortical imaging, providing objective performance comparisons with experimental data, and situating these technological advances within the broader context of high-resolution MRI research.

Fundamental Principles of High-Density Array Coils

Physical Basis of Signal Reception in MRI

The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) represents the fundamental metric for image quality in magnetic resonance imaging. SNR improvements enable either higher spatial resolution through smaller voxel sizes, faster acquisition times, or improved contrast-to-noise ratio for functional studies. The principle underlying surface coil technology is that coil sensitivity is highly dependent on proximity to the tissue of interest – the closer a coil element is placed to tissue, the better its SNR performance [37]. This relationship explains why standard volume coils (e.g., birdcage coils), while providing relatively uniform sensitivity, cannot match the peak SNR achievable with surface coils placed directly adjacent to the cortex.

High-density array coils capitalize on this principle by utilizing multiple small coil elements arranged in conformal patterns around the head. Each small coil element offers high sensitivity to nearby tissues but with a limited penetration depth. By combining signals from numerous such elements, it becomes possible to achieve both high SNR in cortical regions and comprehensive brain coverage [4]. The penetration depth of surface coils is roughly equivalent to their diameter, meaning that reducing coil diameter increases SNR close to the surface at the cost of decreased sensitivity in deeper tissues [38]. However, this limitation can be mitigated by increasing the number of receive elements, creating a dense array that maintains high surface SNR while preserving adequate sensitivity at depth through the composite image formed from all channels [38].

Technical Evolution from Single Channel to Multi-Channel Arrays

The progression from single-channel surface coils to modern high-density arrays represents one of the most significant advancements in MRI hardware. Early array coils with just 4 irregularly shaped receivers demonstrated the potential of this approach, showing SNR improvements of 1-1.5 times in central brain areas and 2-3 times in cortical regions compared to volume coils [37]. This foundational work established that array coils could dramatically increase quality and resolution over large brain volumes while maintaining compatibility with standard neuroimaging configurations.

Modern high-density arrays have expanded this concept dramatically, with channel counts growing from 4 to 32, 64, 96, and now 128 channels [4] [39]. This progression has been enabled by advances in coil decoupling techniques, preamplifier design, and digital receiver systems capable of processing numerous parallel channels. Each technological iteration has brought reductions in individual coil element size, with optimal loop diameters of approximately 4 cm at 7T for maximizing cortical signal [4]. The development of self-decoupled coil designs, including recent toroidal configurations, further facilitates dense packing by eliminating traditional decoupling limitations [40].

Performance Comparison: High-Density Arrays vs. Standard Alternatives

Quantitative SNR and g-Factor Analysis

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Different Receiver Array Coils at 7 Tesla

| Array Configuration | Cortical SNR Improvement | g-Factor Performance | Acceleration Capability | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32-channel (standard) | Reference level | Higher noise penalty | Moderate acceleration | General neuroimaging |

| 64-channel array | ~30% improvement [4] | Reduced g-factor [4] | R = 4-5 [4] | High-resolution fMRI |

| 96-channel array | ~30% improvement [4] | Superior g-factor [4] | R = 5-8 [4] | Laminar fMRI, diffusion imaging |

| 72-channel Connectome | 1.4x higher SNR [39] | Improved g-factor [39] | High acceleration for diffusion | Connectomics, high-b-value DWI |

| Dedicated cerebellar array | 2-3x surface SNR [38] | Significant g-factor gains [38] | Accelerated cerebellar imaging | Cerebellar fMRI, cognitive studies |

The performance advantages of high-density arrays are quantifiable across multiple metrics. Compared to standard 32-channel arrays, 64-channel and 96-channel configurations demonstrate approximately 30% higher SNR in cortical regions [4]. This improvement is not uniform throughout the brain but is particularly pronounced in peripheral regions adjacent to the coil elements. The center of the coil array does not show significantly higher SNR for higher channel count arrays, highlighting the importance of targeted coil design for cortical applications [4].

Beyond raw SNR improvements, high-density arrays excel in parallel imaging performance, characterized by the g-factor, which represents the noise amplification resulting from accelerated acquisition. Arrays with higher channel counts and reduced coil loop sizes consistently demonstrate lower g-factor penalties, enabling higher acceleration factors (R) without prohibitive SNR loss [4]. This capability is particularly valuable for high-resolution EPI sequences used in fMRI, where shorter echo trains reduce T2* blurring and geometric distortions [4].

Specialized Array Configurations for Targeted Imaging

Table 2: Specialized High-Density Array Configurations and Applications

| Array Type | Configuration | Target Region | Performance Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asymmetric head array | 96-ch Rx, 16-ch Tx [4] | Whole-brain cortex | Improved image uniformity, reduced power deposition |

| Cerebellar array | 3Tx/32Rx [38] | Cerebellum and brainstem | Improved B1+ and SNR at cerebellar surface |

| Flexible supplemental coil | Elliptical flex coil [41] | Frontal and subcortical | Recovers signal in half-volume coil configurations |

| Connectome array | 72-ch with field monitoring [39] | Whole-brain connectomics | Enables high-b-value diffusion with field correction |

| Implantable coils | Single-loop or figure-8 [42] | Preclinical deep structures | 100-500% SNR increase over surface arrays |

Not all imaging applications require whole-brain coverage, and targeted high-density arrays can provide optimized performance for specific neuroanatomical regions. For cerebellar imaging – particularly challenging due to its location at the brain's base and small structural features – dedicated arrays combining 3-channel transmit with 32-channel receive elements have demonstrated substantial improvements in B1+ transmit efficiency and SNR [38]. These specialized arrays address the specific challenges of ultra-high field imaging in the cerebellum, where traditional volume coils produce signal cancellation.

Similarly, flexible array designs enable novel configurations that balance SNR with practical experimental requirements. When front-face clearance is needed for visual stimulation devices or virtual reality systems, a half-volume head coil supplemented with a forehead flex coil can recover the SNR losses in frontal and subcortical regions that would otherwise occur with a posterior-only array [41]. This configuration maintains the ability to detect task-related fMRI signals in regions critical for emotional decision-making and perception, such as the amygdala [41].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Bench-Level Characterization of Array Performance

Comprehensive evaluation of high-density array coils begins with RF bench-level metrics before progressing to imaging experiments. Standard characterization includes measurements of quality factor (Q), tuning, matching, and inter-element coupling [39]. The quality factor represents the efficiency of energy storage in the coil relative to energy loss, with higher Q factors generally indicating better coil performance. Proper tuning ensures the coil resonates at the Larmor frequency of the scanner (e.g., 298 MHz for 7T), while matching optimizes power transfer between the coil and the transmission line.

Inter-element coupling measurements are particularly critical for high-density arrays, as electromagnetic interactions between adjacent coil elements can degrade performance. Contemporary arrays minimize coupling through overlap optimization, low-input-impedance preamplifiers, and in some designs, common-mode suppression techniques [39]. The effectiveness of decoupling is quantified through scattering (S)-parameter measurements, with S12 values below -15 dB generally indicating sufficient isolation between elements. Additional bench tests include evaluation of active detuning circuits, which must effectively decouple receive elements during the transmit phase to prevent perturbation of the B1+ field and ensure patient safety.

In Vivo Imaging Protocols for Performance Validation

Following bench characterization, array performance is validated through a series of in vivo imaging experiments designed to quantify SNR, parallel imaging capability, and ultimate image quality. Standard protocols include:

SNR Mapping: Multiple techniques exist for SNR quantification, including the multiple replica method (repeated identical acquisitions) and difference method (subtraction of two acquisitions) [39]. These measurements are performed throughout the brain to characterize the spatial distribution of signal sensitivity, with particular attention to cortical regions.

Parallel Imaging Evaluation: The acceleration capability of arrays is quantified through g-factor mapping, typically performed by comparing fully sampled reference data with retrospectively or prospectively accelerated acquisitions [4] [39]. This evaluation includes both in-plane (e.g., SENSE, GRAPPA) and through-plane (e.g., multiband) acceleration techniques, with contemporary high-density arrays supporting combined acceleration factors of R=8 or higher with acceptable g-factor penalties [4].

Functional and Structural Imaging: Ultimate validation comes from high-resolution fMRI and structural imaging protocols. For fMRI, the critical metric is temporal SNR (tSNR), which incorporates both thermal noise and physiological fluctuations [38]. High-density arrays consistently demonstrate tSNR improvements in cortical regions, directly translating to enhanced detection sensitivity for BOLD activation [38]. For structural imaging, qualitative assessment of cortical architecture visualization provides compelling evidence of improved spatial resolution, with some studies demonstrating clear visualization of the stria of Gennari in visual cortex [37].

Integration with Complementary Technologies

Synergy with High-Performance Gradient Systems

The benefits of high-density receiver arrays are magnified when combined with advanced gradient systems. Next-generation MRI scanners designed for ultra-high-resolution human brain imaging incorporate asymmetric head-only gradient coils capable of reaching 200 mT/m amplitude and 900 T/m/s slew rates [4]. These performance characteristics represent approximately five-fold improvement over standard whole-body gradient systems [4].

The synergy between high-performance gradients and dense arrays is particularly evident in echo-planar imaging (EPI), the workhorse sequence for fMRI. The Impulse gradient coil achieves shorter echo spacing (0.58 ms at 0.6 mm resolution versus 1.21 ms with body gradients), resulting in reduced T2* blurring and geometric distortion [4]. When combined with the acceleration capabilities of high-density arrays, this enables high-resolution EPI with minimal distortion, crucial for layer-specific fMRI where precise spatial localization is paramount.

Field Monitoring and Correction Systems

Advanced diffusion imaging with strong diffusion-sensitizing gradients presents particular challenges due to nonlinear spatiotemporal magnetic field disturbances. The integration of field monitoring systems directly into high-density array coils addresses this limitation by enabling real-time measurement and correction of field perturbations [39]. These systems typically employ 16-channel field monitoring arrays based on NMR field cameras that concurrently measure magnetic field dynamics during image acquisition [39].

The combination of high-density receiver arrays with integrated field monitoring creates a powerful platform for high-resolution diffusion imaging, substantially reducing geometric distortions, blurring, and ghosting in high-b-value DWI [39]. This integration has proven particularly valuable for Connectome-style scanners, where the goal is mapping brain microstructure with sub-millimeter isotropic resolution throughout the entire brain [39].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Technologies

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for High-Density Array Experiments