Brain-Inspired Metaheuristic Algorithms: A Comprehensive Overview for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive examination of brain-inspired metaheuristic algorithms, exploring their foundational principles, methodological implementations, optimization challenges, and validation frameworks.

Brain-Inspired Metaheuristic Algorithms: A Comprehensive Overview for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of brain-inspired metaheuristic algorithms, exploring their foundational principles, methodological implementations, optimization challenges, and validation frameworks. Targeting researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we analyze how these algorithms leverage computational models of neural processes to solve complex optimization problems in biomedical domains. The review covers emerging applications in CNS drug discovery, neuroimaging analysis, and clinical diagnostics, while addressing critical implementation considerations and comparative performance metrics. By synthesizing current research trends and practical applications, this overview serves as both an educational resource and strategic guide for leveraging brain-inspired computing in scientific innovation.

The Neuroscience Behind Brain-Inspired Computing: From Biological Principles to Algorithmic Foundations

Theoretical Foundations of Neural Population Dynamics

Neural population dynamics is a conceptual and analytical framework for understanding how collective activity within large groups of neurons gives rise to brain functions. This approach moves beyond studying individual neurons to focus on how coordinated activity patterns across neural populations evolve over time to support cognition, perception, and action. The core principle posits that neural computations emerge from the coordinated temporal evolution of population activity states within a high-dimensional neural space. Research across multiple brain regions has revealed that these population dynamics operate within low-dimensional manifolds, where complex neural activity patterns can be described by a relatively small number of latent variables [1] [2].

A fundamental characteristic of neural population dynamics is its context-dependent nature. Studies of the posterior parietal cortex (PPC) have revealed that neurons projecting to the same target area exhibit elevated pairwise activity correlations structured as information-enhancing motifs. This specialized correlation structure enhances population-level information about behavioral choices and is uniquely present when animals make correct, but not incorrect, decisions [3]. Similarly, research in primary visual cortex demonstrates that contrast gain control can be understood as a reparameterization of population response curves, where neural populations adjust their gain factors collectively in response to environmental statistics [4]. This coordinated adjustment maintains invariant contrast-response relationships across different environments, facilitating stable stimulus representation.

The dynamical regimes observed in neural populations vary considerably depending on the behavioral context and brain region. During reaching movements, primary motor cortex (M1) exhibits low-dimensional rotational dynamics characteristic of an autonomous pattern generator. However, during grasping movements, these dynamics are largely absent, with M1 activity instead resembling the more "tangled" dynamics typical of sensory-driven responses [2]. This fundamental difference suggests that the dynamical principles governing neural population activity are tailored to specific computational requirements and effector systems.

Neural Dynamics of Decision-Making

Decision-making represents a prime cognitive process for studying neural population dynamics, as it involves the gradual accumulation of sensory evidence toward a categorical choice. Attractor network models have been particularly influential in conceptualizing the neural dynamics underlying decision formation. These models propose that decision-making emerges from the evolution of neural population activity toward stable attractor states corresponding to different decision outcomes [1].

Recent research using unsupervised deep learning methods to infer latent dynamics from large-scale neural recordings has revealed sophisticated dynamical patterns during decision-making. Studies of rats performing auditory evidence accumulation tasks identified that neural trajectories evolve through two sequential regimes: an initial phase dominated by sensory inputs, followed by a transition to a phase dominated by autonomous dynamics. This transition is marked by a change in the neural mode (flow direction) and is thought to represent the moment of decision commitment [1]. The timing of this neural commitment transition varies across trials and is not time-locked to stimulus or response events, providing a potential neural correlate of internal decision states.

Different brain regions exhibit distinct accumulation strategies during decision-making. Comparative studies of the posterior parietal cortex (PPC), frontal orienting fields (FOF), and anterior-dorsal striatum (ADS) during pulse-based accumulation tasks reveal region-specific dynamics. The FOF shows dynamics consistent with an unstable accumulator that favors early evidence, while the ADS reflects near-perfect accumulation, and the PPC displays weaker graded accumulation signals. Notably, all these regional accumulation models differ from the model that best describes the animal's overall choice behavior, suggesting that whole-organism decision-making emerges from the integration of multiple neural accumulation processes [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Evidence Accumulation Characteristics Across Brain Regions

| Brain Region | Accumulation Type | Temporal Weighting | Choice Certainty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior-Dorsal Striatum (ADS) | Near-perfect accumulation | Balanced | Extensive choice vacillation |

| Frontal Orienting Fields (FOF) | Unstable accumulation | Favors early evidence | Greater choice certainty |

| Posterior Parietal Cortex (PPC) | Graded accumulation | Intermediate | Moderate certainty |

The structure of neural population codes significantly influences decision accuracy. In the PPC, specialized correlation structures among neurons projecting to the same target area enhance population-level information about behavioral choices. These information-enhancing network structures are present specifically during correct decisions but break down during errors, demonstrating how coordinated population dynamics support behavioral accuracy [3].

Experimental Methods and Analysis Techniques

Neural Recording Approaches

Studying neural population dynamics requires recording from large numbers of neurons simultaneously while animals perform controlled behavioral tasks. Two-photon calcium imaging through cranial windows provides high-resolution spatial information about neural activity, particularly in superficial cortical layers. This approach allows for identification of projection-specific neuronal populations through retrograde tracing techniques, wherein fluorescent tracers conjugated to different colors are injected into target areas to label neurons with specific axonal projections [3]. For higher temporal resolution and deeper structure recordings, Neuropixels probes enable simultaneous monitoring of hundreds of neurons across multiple brain regions, providing unprecedented access to network-level interactions during decision-making [1].

Electrophysiological recordings from chronically implanted electrode arrays offer another key methodology, particularly suitable for studying motor cortex dynamics during naturalistic behaviors. These arrays provide millisecond-scale temporal resolution of spiking activity across neuronal populations, enabling detailed analysis of dynamics in relation to movement parameters [2]. Each recording modality offers complementary strengths, with calcium imaging providing rich spatial and genetic information, while electrophysiological methods deliver superior temporal resolution.

Analytical Frameworks for Dynamics Inference

Several sophisticated analytical frameworks have been developed to infer latent dynamics from population recording data:

Flow Field Inference from Neural Data using Deep Recurrent Networks (FINDR) is an unsupervised deep learning method that estimates the low-dimensional stochastic dynamics best accounting for population spiking data. This approach models the instantaneous change of decision variables (ż) as a function of the current state (z), external inputs (u), and noise (η) through the equation: ż = F(z, u) + η. FINDR approximates F using a gated multilayer perceptron network, with each neuron's firing rate modeled as a weighted sum of the z variables followed by a softplus nonlinearity [1].

Vine Copula (NPvC) Models provide a nonparametric approach for estimating multivariate dependencies among neural activity, task variables, and movement parameters. This method expresses multivariate probability densities as products of copulas, which quantify statistical dependencies, and marginal distributions. NPvC models break down complex multivariate dependency estimation into sequences of simpler bivariate dependencies, offering advantages over generalized linear models in capturing nonlinear relationships and discounting collinearities between task and behavioral variables [3].

Latent Factor Analysis via Dynamical Systems (LFADS) infers latent dynamics from neural population data to improve single-trial firing rate estimates. This approach benefits analyses particularly when neural populations act as dynamical systems, with greater improvements indicating stronger underlying dynamics [2].

Table 2: Key Analytical Methods for Neural Population Dynamics

| Method | Primary Function | Advantages | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| FINDR | Infers low-dimensional stochastic dynamics | Flexible, interpretable, captures decision noise | Identifying transition points in decision commitment [1] |

| NPvC Models | Estimates multivariate dependencies | Captures nonlinear relationships, robust to collinearities | Isolating task variable contributions to neural activity [3] |

| LFADS | Infers latent dynamics for firing rate estimation | Handles high-dimensional, nonlinear dynamics | Comparing dynamical structure across brain regions [2] |

| jPCA | Identifies rotational dynamics | Reveals low-dimensional manifolds | Characterizing motor cortex dynamics during reaching [2] |

Dynamics Quantification Metrics

Several specialized metrics enable quantification of dynamical properties from neural population data:

The neural tangling metric (Q) assesses the degree to which network dynamics are governed by a smooth, consistent flow field. In smooth autonomous dynamical systems, neural trajectories passing through nearby points in state space should have similar derivatives. The tangling metric quantifies deviations from this principle, with lower values indicating more autonomous dynamics characteristic of pattern generators, and higher values indicating more input-driven dynamics [2].

Cross-temporal generalization in decoding analyses evaluates the temporal stability of neural representations. Representations that show strong cross-temporal generalization indicate more stable neural codes, while poor generalization suggests more dynamic, time-varying representations [6].

Decoding accuracy for task variables or movement parameters provides a functional measure of information content in neural population activity. Improvements in decoding accuracy through dynamical methods like LFADS indicate the presence of underlying dynamics that support the generated behavior [2].

Computational Modeling Approaches

Macroscopic Brain Modeling

Coarse-grained modeling approaches simulate macroscopic brain dynamics by representing neural populations or brain regions as individual nodes. These models strike a balance between biological realism and computational tractability, enabling whole-brain simulations that can be informed by empirical data from modalities like fMRI, dMRI, and EEG. Common implementations include the Wilson-Cowan model, Kuramoto model, and dynamic mean-field (DMF) model, which use closed-form equations to describe population-level dynamics [7].

The process of model inversion—identifying parameters that best fit empirical data—is computationally demanding but essential for creating biologically plausible models. Recent advances have addressed these challenges through dynamics-aware quantization frameworks that enable accurate low-precision simulation while maintaining dynamical characteristics. These approaches facilitate deployment on specialized hardware, including brain-inspired computing architectures, achieving significant acceleration over conventional CPUs [7].

Attractor Network Models of Decision-Making

Attractor network models provide a dominant theoretical framework for understanding decision-making dynamics. Several specific implementations have been proposed:

The DDM line attractor model posits a line attractor in neural space with point attractors at the ends representing decision bounds. Evidence inputs drive movement along the line attractor until a bound is reached, corresponding to decision commitment [1].

Bistable attractor models feature two point attractors representing decision options, with a one-dimensional stable manifold between them corresponding to evidence accumulation. Evidence inputs align with this slow manifold, driving the system toward one attractor or the other [1].

Non-normal dynamics models, inspired by trained recurrent neural networks, also employ line attractors but allow evidence inputs that are not aligned with the attractor. These models accumulate evidence through non-normal autonomous dynamics that transiently amplify specific input patterns [1].

Each model makes distinct predictions about the relationship between autonomous and input-driven dynamics, which can be tested experimentally using the inference methods described previously.

Visualization of Neural Population Dynamics

Experimental Workflow for Decision-Making Studies

The following diagram outlines a typical experimental workflow for studying neural population dynamics during decision-making tasks:

Neural Trajectories in Decision-Making

This diagram illustrates the evolution of neural population activity during evidence accumulation:

Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Neural Population Dynamics Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Two-photon Calcium Imaging | High-resolution spatial mapping of neural activity | Recording from identified neuronal populations in PPC [3] |

| Neuropixels Probes | Large-scale electrophysiology across multiple brain regions | Simultaneous recording from frontal cortex and striatum [1] |

| Retrograde Tracers | Labeling neurons based on projection targets | Identifying PPC neurons projecting to ACC, RSC, and contralateral PPC [3] |

| FINDR Software | Unsupervised inference of latent dynamics | Discovering decision-related dynamics in frontal cortex [1] |

| NPvC Modeling Framework | Multivariate dependency estimation | Isolating task variable contributions while controlling for movements [3] |

| LFADS | Single-trial neural trajectory inference | Comparing dynamics across brain regions during decision-making [2] |

The pursuit of advanced artificial intelligence increasingly turns to neuroscience for inspiration, seeking to replicate the brain's unparalleled efficiency in computation, learning, and adaptation. This whitepaper distills three foundational neurobiological principles—attractor networks, neural plasticity, and information encoding—that provide a biological blueprint for developing sophisticated brain-inspired metaheuristic algorithms. These principles represent core mechanisms by which biological neural systems achieve stable computation, adapt to experience, and process information. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these mechanisms is paramount for designing algorithms that mimic cognitive functions and for identifying novel therapeutic targets in neurological disorders. The following sections provide a technical deep dive into each principle, summarizing key quantitative data, experimental protocols, and essential research tools to facilitate the translation of biological intelligence into computational innovation.

Attractor Networks: The Brain's Engine for Stable Computation

Attractor networks are a class of recurrent neural networks that evolve toward a stable pattern over time. These stable states, or attractors, allow the brain to maintain persistent activity patterns representing memories, decisions, or perceptual states, making them a fundamental concept for modeling cognitive processes [8].

Computational Typology of Neural Attractors

The brain implements multiple attractor types, each supporting distinct computational functions, from maintaining a single stable state to integrating continuous sensory information [9] [8].

Table 1: Types of Attractor Networks in Neural Computation

| Attractor Type | Mathematical Properties | Postulated Neural Correlates | Computational Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Point Attractor | Single, stable equilibrium state [8] | Stored memory patterns in Hopfield networks [9] | Associative memory, pattern completion, classification [8] |

| Ring Attractor | Continuous, one-dimensional set of stable states forming a ring [9] | Head-direction cells in the limbic system [9] | Encoding of cyclic variables (e.g., head direction) [9] |

| Plane Attractor | Continuous, two-dimensional set of stable states [9] | Grid cells in the medial entorhinal cortex [9] | Spatial navigation and path integration [9] |

| Limit Cycle | Stable, closed trajectory for periodic oscillation [9] | Central pattern generators in the spinal cord [9] | Rhythmic motor outputs (e.g., walking, chewing) [8] |

Experimental Evidence and Protocol: Mapping Attractor DynamicsIn Vitro

Recent innovations in recording techniques have provided direct evidence for attractor dynamics in biological neural networks. The following protocol, adapted from Gillett et al. (2024), details a method for identifying and manipulating attractors in cultured cortical networks [10].

Protocol: Revealing Attractor Plasticity in Cultured Cortical Networks

- Primary Objective: To identify a vocabulary of spatiotemporal firing patterns that function as discrete attractors and to track their plasticity in response to targeted stimulation.

- Preparation: Plate cortical neurons from rodent embryos on a multi-electrode array (MEA) with 120 electrodes. Use mature networks (18-21 days in vitro, DIV) that exhibit synchronized bursting activity [10].

- Data Acquisition: Record extracellular multi-unit activity spontaneously and in response to electrical stimulation. Identify network bursts—synchronized firing events where the summed activity across electrodes crosses a predefined threshold [10].

- Pattern Classification: For each burst, represent the activity as a spatiotemporal pattern. Cluster all recorded bursts into distinct groups based on pattern similarity using a graph-based approach that incorporates multiple similarity measures. These clusters define the network's attractor vocabulary [10].

- Basin of Attraction Analysis: Define the initial condition of a burst as the spatial activity at threshold-crossing. For burst pairs with highly similar initial conditions, calculate the instantaneous correlation of their activity trajectories over time. Convergence to high correlation indicates the presence of a common basin of attraction [10].

- Stimulation Paradigm: Select specific attractor patterns and apply localized electrical stimulation to evoke them repeatedly.

- Plasticity Assessment: Following the stimulation period, re-record spontaneous activity. Quantify changes in the frequency of the stimulated attractors within the spontaneous vocabulary compared to pre-stimulation levels [10].

Key Finding: Stimulating specific attractors paradoxically leads to their elimination from spontaneous activity, while they remain reliably evoked by direct stimulation. This is explained by a Hebbian-like mechanism where stimulated pathways are strengthened at the expense of non-stimulated pathways leading to the same attractor state [10].

Visualization of a Ring Attractor Network

The following diagram models the core architecture of a ring attractor, which is theorized to underlie the function of head-direction cells in the navigational system.

Neural Plasticity: The Substrate for Learning and Adaptation

Neuroplasticity is the nervous system's capacity to change its activity and structure in response to experience. This involves adaptive structural and functional changes, allowing the brain to learn from new experiences, acquire new knowledge, and recover from injury [11] [12].

Mechanisms and Phases of Plasticity After Injury

The plastic response to brain injury, such as stroke, unfolds in a temporally structured sequence, providing a critical window for therapeutic intervention [11].

Table 2: Temporal Phases of Neuroplasticity Following Neural Injury

| Phase | Time Post-Injury | Key Biological Processes | Potential Therapeutic Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute | First 48 hours | Initial cell death; recruitment of secondary neuronal networks to maintain function [11]. | Neuroprotective agents to minimize initial damage and cell death. |

| Subacute | Following weeks | Shift in cortical pathways from inhibitory to excitatory; synaptic plasticity and formation of new connections [11]. | Intensive, task-specific rehabilitation to guide new connection formation. |

| Chronic | Weeks to months | Axonal sprouting and further reorganization of neural circuitry around the site of damage [11]. | Constraint-induced movement therapy; pharmacological cognitive enhancers. |

Experimental Workflow: Tracking Large-Scale Plasticity with Computational Modeling

Cutting-edge research uses coarse-grained computational models to bridge brain structure and function, enabling the study of plasticity at a macroscopic level.

Protocol: Coarse-Grained Modeling of Macroscopic Brain Dynamics

- Primary Objective: To construct a data-driven, whole-brain model that simulates large-scale dynamics and allows for the identification of patient-specific parameters through model inversion [7].

- Model Selection: Employ a coarse-grained model, such as the dynamic mean-field (DMF) model, where each node represents the mean activity of a brain region or neuronal population [7].

- Data Integration: Integrate multi-modal empirical data into the model. Structural connectivity from diffusion MRI (dMRI) defines the connection weights between nodes. Functional data from functional MRI (fMRI) or electroencephalography (EEG) serves as the target for model fitting [7].

- Model Inversion (Identification): This is an optimization process to find the model parameters that best fit the empirical functional data.

- Simulation: The model, with its current parameters and structural connectivity, is simulated to generate simulated functional signals (e.g., BOLD signals for fMRI).

- Evaluation: The simulated functional signals are compared to the empirical functional data to calculate a goodness-of-fit measure.

- Parameter Adjustment: The model parameters are adjusted based on the fit results.

- The process (simulation → evaluation → adjustment) repeats for many iterations until a near-optimal parameter set is identified [7].

- Acceleration with Brain-Inspired Computing: The model inversion process is computationally intensive. To accelerate it, the model can be quantized (converted to low-precision) and deployed on highly parallel hardware architectures, such as brain-inspired computing chips (e.g., Tianjic) or GPUs, achieving significant speedups [7].

Visualization of the Model Inversion Workflow

The following diagram outlines the computational pipeline for inverting a macroscopic brain model, a process key to studying large-scale plastic changes.

Information Encoding: Forging Persistent Neural Representations

Encoding is the critical process by which sensory information and experiences are transformed into a construct that can be stored in the brain and later recalled as memory. It serves as the gateway between perception and lasting memory [13] [14] [15].

Types and Substrates of Memory Encoding

The brain employs multiple, distinct encoding strategies, each with different neural substrates and resulting in memories with varying strengths and properties.

Table 3: Cognitive and Neural Classifications of Information Encoding

| Encoding Type | Definition | Key Brain Regions | Experimental Manipulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semantic Encoding | Processing sensory input based on its meaning and context [13]. | Left Inferior Prefrontal Cortex (LIPC); Orbitofrontal Cortex [13]. | Deeper, semantic processing of words (e.g., living/non-living judgment) vs. shallow processing (e.g., letter counting) [13]. |

| Visual Encoding | Converting images and visual sensory information into memory [13]. | Visuo-spatial sketchpad in working memory; Amygdala for emotional valence [13]. | fMRI activation shows hippocampal and prefrontal activity increases with focused attention during learning [14]. |

| Elaborative Encoding | Actively relating new information to existing knowledge in memory [13]. | Hippocampus; Prefrontal Cortex [14]. | Using mnemonics or creating associative stories to link new items to known concepts [15]. |

| Acoustic Encoding | Encoding of auditory impulses and the sound of information [13]. | Phonological loop in working memory [13]. | Testing for the phonological similarity effect (PSE) in verbal working memory tasks [13]. |

Molecular Basis: Long-Term Potentiation (LTP)

At the synaptic level, a key mechanism for encoding is long-term potentiation (LTP), the experience-dependent strengthening of synaptic connections. The NMDA receptor is critical for initiating LTP. Its activation requires two conditions: (1) the binding of glutamate released from the presynaptic neuron, and (2) sufficient depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron to displace the magnesium ion that blocks the receptor's channel. When these conditions are met, calcium influx through the NMDA receptor triggers intracellular cascades that lead to the insertion of more neurotransmitter receptors into the postsynaptic membrane, thereby strengthening the synapse and lowering the threshold for future activation [13]. This process is a cellular embodiment of Hebb's rule: "neurons that fire together, wire together" [13].

Visualization of the Multistage Memory Process

The following diagram illustrates the pathway from sensory input to long-term memory retrieval, highlighting the role of distinct encoding strategies.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Neuroscience

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Research | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-Electrode Arrays (MEAs) | Extracellular recording and stimulation of neural activity from multiple sites simultaneously [10]. | Mapping spatiotemporal firing patterns and attractor dynamics in in vitro cultured cortical networks [10]. |

| Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) | Non-invasive measurement of brain activity by detecting changes in blood flow (BOLD signal) [7]. | Whole-brain functional connectivity mapping and validation of coarse-grained computational models [7]. |

| Diffusion MRI (dMRI) | Non-invasive reconstruction of white matter tracts by measuring the diffusion of water molecules [7]. | Providing structural connectivity matrices to constrain whole-brain computational models [7]. |

| Positron Emission Tomography (PET) | Imaging brain function by detecting radiolabeled tracers, allowing for quantification of cerebral blood flow or neurotransmitter systems [13]. | Identifying hippocampal activation during episodic encoding and retrieval; studying neurochemical correlates of memory [13]. |

| Cortical Neuronal Cultures | In vitro model system for studying network-level dynamics and plasticity in a controlled environment [10]. | Investigating spontaneous network bursts, pattern vocabulary, and the effects of stimulation on attractor plasticity [10]. |

Optimization challenges are pervasive in fields ranging from engineering design and logistics to artificial intelligence and drug discovery. Traditional optimization methods often struggle with the high dimensionality, non-convexity, and complex constraints characteristic of these real-world problems. Brain-inspired metaheuristic algorithms have emerged as powerful alternatives, demonstrating remarkable effectiveness in navigating complex search spaces without requiring gradient information or differentiable objective functions [16].

This technical guide provides a comprehensive taxonomy and analysis of nature-inspired metaheuristic optimization algorithms, framing them within a structured biological and physical inspiration framework. These algorithms simulate natural processes—including evolution, collective animal behavior, and physical laws—to solve complex optimization problems. Their relevance to drug development professionals and researchers lies in their proven applicability to molecular docking simulation, biomedical diagnostics, protein structure prediction, and parameter tuning for machine learning models used in pharmaceutical research [17] [16] [18].

We present a detailed classification of these algorithms into three primary categories—evolutionary, swarm intelligence, and physics-based approaches—complete with structured comparisons, experimental methodologies, and visualization of their underlying mechanisms. The growing commercial significance of these approaches is underscored by market analyses indicating rapid expansion, particularly for swarm intelligence applications which are projected to grow at a CAGR of 31.5% from 2025-2029 [19].

Algorithmic Taxonomy and Classification Framework

Metaheuristic algorithms can be systematically classified based on their fundamental sources of inspiration. This taxonomy organizes them into three principal categories, each with distinct mechanistic foundations and representative algorithms.

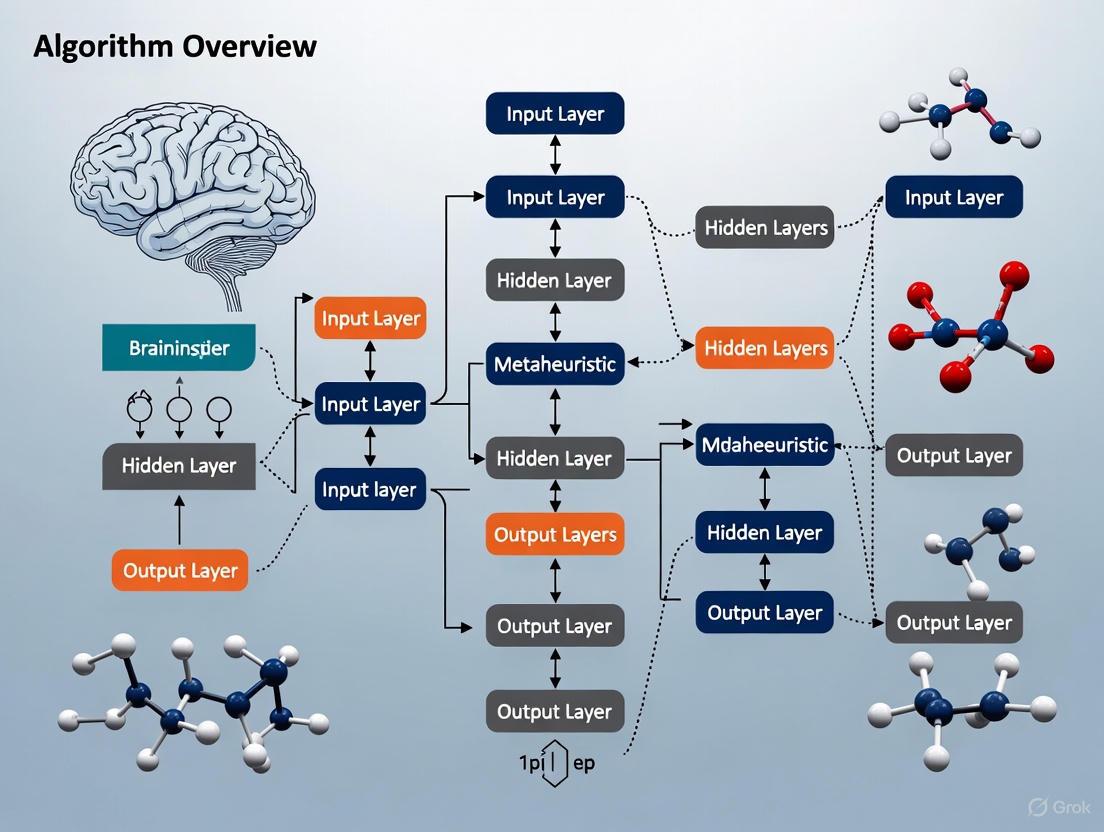

Hierarchical Classification

The diagram below illustrates the hierarchical relationship between major algorithm categories and their inspirations.

Comprehensive Algorithm Classification

Table 1: Detailed Classification of Metaheuristic Algorithms by Inspiration Category

| Category | Inspiration Source | Representative Algorithms | Key Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evolutionary Algorithms | Darwinian natural selection | Genetic Algorithm (GA) [17], Genetic Programming (GP) [20], Differential Evolution (DE) [16], Evolution Strategies (ES) [20] | Selection, Crossover, Mutation, Recombination |

| Swarm Intelligence | Collective behavior of animals | Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [17], Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) [17], Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) [17], Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) [17], Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) [17] | Self-organization, Decentralized control, Stigmergy, Leadership-followership |

| Physics-Based Approaches | Physical laws and phenomena | Archimedes Optimization Algorithm (AOA) [20], Centered Collision Optimizer (CCO) [16], Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA) [20], Simulated Annealing (SA) [20] | Physical collisions, Gravitational forces, Thermodynamic processes, Fluid dynamics |

| Human-Based Algorithms | Human social behavior | Harmony Search (HS) [20], Teaching Learning-Based Algorithm (TLBA) [20], League Championship Algorithm (LCA) [20] | Social interaction, Learning processes, Competitive behaviors |

Evolutionary Algorithms

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs) form a cornerstone of bio-inspired optimization, operating on principles directly drawn from Darwinian evolution. These population-based metaheuristics simulate natural selection processes, where a population of potential solutions evolves over generations through mechanisms mimicking biological evolution [21]. EAs maintain a population of candidate solutions and artificially "evolve" this population over time through structured yet stochastic operations [21].

The fundamental cycle of EAs begins with initialization of a random population, followed by iterative application of selection, reproduction, and replacement operations. Selection mechanisms favor fitter individuals based on their objective function values, analogous to survival of the fittest in nature. Reproduction occurs through genetic operators—primarily crossover (recombination) and mutation—which create new candidate solutions by combining or modifying existing ones [20]. The algorithm terminates when predefined stopping criteria are met, such as reaching a maximum number of generations or achieving a satisfactory solution quality.

Representative Algorithms and Applications

Table 2: Major Evolutionary Algorithm Variants and Their Applications

| Algorithm | Key Features | Typical Applications | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) [17] | Uses binary or real-valued representation, roulette wheel selection, crossover, mutation | Combinatorial optimization, feature selection, scheduling | Robust, parallelizable, handles non-differentiable functions |

| Differential Evolution (DE) [16] | Uses difference vectors for mutation, binomial crossover | Engineering design, numerical optimization, parameter tuning | Simple implementation, effective continuous optimization |

| Genetic Programming (GP) [20] | Evolves computer programs, tree-based representation | Symbolic regression, automated program synthesis, circuit design | Discovers novel solutions without predefined structure |

| Evolution Strategy (ES) [20] | Self-adaptive mutation parameters, real-valued representation | Mechanical engineering design, neural network training | Effective local search, self-adaptation to problem landscape |

EAs have demonstrated particular success in biomedical and pharmaceutical applications. In drug discovery, they facilitate molecular docking simulations by efficiently searching the conformational space of ligand-receptor interactions [17]. Their ability to handle high-dimensional, non-linear problems makes them valuable for optimizing complex biological systems where traditional methods struggle with multiple local optima and noisy evaluation functions.

Swarm Intelligence Algorithms

Theoretical Foundations and Models

Swarm Intelligence (SI) algorithms simulate the collective behavior of decentralized, self-organized systems found in nature. These algorithms model how simple agents following basic rules can generate sophisticated group-level intelligence through local interactions [22]. The theoretical foundation of SI rests on several biological models that explain emergent collective behaviors.

The Boids model exemplifies self-driven particle systems, simulating flocking behavior through three simple rules: separation (avoid crowding neighbors), alignment (steer toward average heading of neighbors), and cohesion (move toward average position of neighbors) [22]. Pheromone communication models, particularly those inspired by ant foraging, utilize stigmergy—indirect coordination through environmental modifications—where artificial pheromones reinforce promising solution paths [22]. Leadership decision models simulate hierarchical structures observed in bird flocks or wolf packs, where leader individuals influence group direction [22]. Empirical research models leverage data-driven observations of natural swarms, such as the topological interaction rules in starling murmurations [22].

Algorithmic Diversity and Methodologies

Table 3: Swarm Intelligence Algorithms and Methodological Approaches

| Algorithm | Biological Inspiration | Key Update Mechanism | Parameter Tuning Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [17] | Bird flocking, fish schooling | Velocity update based on personal and global best | Inertia weight, acceleration coefficients, neighborhood topology |

| Ant Colony Optimization (ACO) [17] | Ant foraging behavior | Probabilistic path selection based on pheromone trails | Evaporation rate, pheromone importance, heuristic influence |

| Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) [17] | Honeybee foraging | Employed, onlooker, and scout bees with different roles | Limit for abandonment, colony size, modification rate |

| Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) [17] | Wolf pack hierarchy | Encircling, hunting, and attacking prey based on alpha, beta, delta leadership | Convergence parameter a decreases linearly from 2 to 0 |

The commercial significance of SI is substantial, with the global swarm intelligence market projected to grow by USD 285.1 million during 2024-2029, accelerating at a CAGR of 31.5% [23]. This growth is driven by increasing demand for autonomous and collaborative systems across transportation, logistics, healthcare, and robotics applications [19].

Physics-Based Optimization Algorithms

Principles and Methodologies

Physics-Based Optimization Algorithms derive their inspiration from physical laws and phenomena rather than biological systems. These algorithms model physical processes such as gravitational forces, electromagnetic fields, thermodynamic systems, and mechanical collisions to guide the search for optimal solutions [20]. Unlike evolutionary or swarm approaches that emulate biological adaptation, physics-based methods leverage mathematical formulations of physical principles to navigate complex solution spaces.

The Archimedes Optimization Algorithm (AOA) exemplifies this category, simulating the principle of buoyancy where objects immersed in fluid experience an upward force equal to the weight of the fluid they displace [20]. In AOA, candidate solutions are represented as objects with density, volume, and acceleration properties, with these parameters updated iteratively based on collisions with other objects to balance exploration and exploitation.

The Centered Collision Optimizer (CCO) represents a more recent advancement, inspired by head-on collision equations in classical physics [16]. CCO employs a unified position update strategy operating simultaneously in both original and decorrelated solution spaces, significantly enhancing global search capability and improving local optima escape. Additionally, its Space Allocation Strategy accelerates convergence and improves search efficiency [16].

Performance Comparison and Applications

Table 4: Physics-Based Algorithm Performance Comparison

| Algorithm | Physical Inspiration | Competitive Algorithms Compared Against | Performance Superiority |

|---|---|---|---|

| Archimedes Optimization Algorithm (AOA) [20] | Archimedes' principle of buoyancy | GA, DE, FA, BA, WOA, GWO, SCA, MPA | 72.22% of cases with stable dispersion in box-plot analyses |

| Centered Collision Optimizer (CCO) [16] | Head-on collision physics | 25 high-performance algorithms including CEC2017 champions | Superior accuracy, stability, statistical significance on CEC2017, CEC2019, CEC2022 benchmarks |

| Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA) [20] | Newton's law of gravitation | PSO, GA, DE | Effective for continuous optimization with mass interactions |

Extensive evaluations demonstrate that CCO consistently outperforms 25 high-performance algorithms—including two CEC2017 champion algorithms—in terms of accuracy, stability, and statistical significance across multiple benchmark suites (CEC2017, CEC2019, and CEC2022) [16]. On six constrained engineering design problems and five photovoltaic cell parameter identification tasks, CCO achieved the highest accuracy, consistently ranking first among nine competitive algorithms [16].

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Standardized Evaluation Methodology

Rigorous evaluation of brain-inspired algorithms requires standardized experimental protocols to ensure meaningful performance comparisons. The following workflow outlines the established methodology for benchmarking metaheuristic optimization algorithms.

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Algorithm Development

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CEC Benchmark Suites [16] | Standardized Test Problems | Algorithm performance evaluation on constrained, unconstrained, and real-world problems | Comparative analysis of convergence, accuracy, and robustness |

| EvoHyp Library [24] | Software Framework | Evolutionary hyper-heuristic development in Java and Python | Automated selection and generation of low-level heuristics |

| MATLAB Central Code Repository [16] | Algorithm Implementation | Publicly accessible source code for algorithm validation | CCO and other physics-based algorithm implementation |

| PRISMA Guidelines [18] | Methodological Framework | Systematic literature review and evidence synthesis | Structured analysis of algorithm performance across studies |

Benchmarking typically employs three complementary problem categories: synthetic benchmark functions (e.g., CEC2017, CEC2019, CEC2022) with known optima to measure convergence speed and accuracy; constrained engineering design problems to evaluate constraint handling capabilities; and real-world applications to assess practical utility [16]. Performance metrics commonly include solution quality (distance to known optimum), convergence speed (function evaluations versus solution improvement), robustness (performance consistency across multiple runs), and statistical significance (e.g., Wilcoxon signed-rank test) [16].

For specialized domains such as medical applications, additional domain-specific metrics are employed. In brain tumor segmentation, for instance, performance evaluation typically includes the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC), Jaccard Index (JI), Hausdorff Distance (HD), and Average Symmetric Surface Distance (ASSD) to quantify segmentation accuracy against expert-annotated ground truth [18].

Emerging Trends and Future Research Directions

The field of brain-inspired algorithms continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping future research directions. Hybrid metaheuristics that combine strengths of different algorithmic families are gaining prominence, such as swarm intelligence integrated with evolutionary approaches or physics-based algorithms enhanced with local search mechanisms [17] [16]. These hybrids often demonstrate superior performance compared to their standalone counterparts by more effectively balancing exploration and exploitation.

Explainable AI approaches are being increasingly applied to metaheuristics, creating explainable hyper-heuristics that provide insights into algorithm decision-making processes and performance characteristics [24]. This transparency is particularly valuable for building trust in sensitive applications like medical diagnostics and drug discovery.

Transfer learning in evolutionary computation represents another frontier, where knowledge gained from solving one set of problems is transferred to accelerate optimization of related problems [24]. This approach shows particular promise for computational biology and pharmaceutical applications where similar molecular structures or biological pathways may benefit from transferred optimization knowledge.

The integration of metaheuristics with deep learning continues to advance, particularly in medical imaging applications like brain tumor segmentation where algorithms such as PSO, GA, GWO, WOA, and novel hybrids including CJHBA and BioSwarmNet optimize hyperparameters, architectural choices, and attention mechanisms in deep neural networks [18]. This synergy between bio-inspired optimization and deep learning demonstrates significantly enhanced segmentation accuracy and robustness, particularly in multimodal settings involving FLAIR and T1CE modalities [18].

As the field progresses, research challenges remain in improving algorithm scalability, convergence guarantees, reliability assessment, and interpretability—particularly for high-stakes applications in healthcare and pharmaceutical development [17]. Addressing these challenges will require continued interdisciplinary collaboration between computer scientists, biologists, physicists, and domain specialists to further refine these powerful optimization tools.

The pursuit of optimal solutions in complex biomedical optimization problems represents a significant challenge for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. Traditional metaheuristic algorithms, including Genetic Algorithms (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), have established themselves as powerful tools for navigating high-dimensional, non-linear problem spaces prevalent in biological systems. These population-based optimization techniques draw inspiration from natural processes such as evolution, swarm behavior, and foraging patterns to efficiently explore solution landscapes that are intractable for exact optimization methods. In biomedical contexts, these algorithms have demonstrated considerable success in applications ranging from medical image segmentation and disease diagnosis to drug discovery and treatment optimization.

However, the escalating complexity of modern biomedical problems—particularly in neurology, oncology, and pharmaceutical development—has revealed limitations in traditional metaheuristics, including premature convergence, parameter sensitivity, and difficulties in modeling complex biological systems. This has catalyzed the emergence of brain-inspired metaheuristic algorithms that incorporate principles from neuroscience and cognitive science to overcome these limitations. These advanced algorithms mimic organizational principles of the human brain, such as topographic mapping, contextual processing, and hierarchical memory systems, to achieve superior performance in biomedical optimization tasks.

This technical guide provides a comprehensive comparative analysis between traditional and brain-inspired metaheuristic approaches, with a specific focus on their applications, efficacy, and implementation in complex biomedical optimization scenarios. By examining algorithmic frameworks, performance metrics, and experimental protocols, we aim to equip researchers with the knowledge necessary to select and implement appropriate optimization strategies for their specific biomedical challenges, ultimately accelerating progress in healthcare innovation and therapeutic development.

Theoretical Foundations: From Biological Inspiration to Computational Frameworks

Traditional Metaheuristics: Principles and Classifications

Traditional metaheuristic algorithms are high-level, problem-independent algorithmic frameworks designed to guide subordinate heuristics in exploring complex solution spaces. These methods are particularly valuable for addressing NP-hard, large-scale, or poorly understood optimization problems where traditional exact algorithms become computationally prohibitive. Metaheuristics can be broadly classified into several categories based on their source of inspiration and operational characteristics [25].

Evolutionary algorithms, including Genetic Algorithms (GA) and Differential Evolution (DE), are inspired by biological evolution and employ mechanisms such as selection, crossover, and mutation to evolve populations of candidate solutions toward optimality. Swarm intelligence algorithms, such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), emulate the collective behavior of decentralized biological systems like bird flocks, fish schools, and ant colonies. Physics-based algorithms draw inspiration from physical laws, with examples including the Gravitational Search Algorithm and Water Cycle Algorithm, where search agents follow rules derived from phenomena like gravity or fluid dynamics [25].

A critical aspect governing the performance of all metaheuristic algorithms is the balance between exploration (diversification) and exploitation (intensification). Exploration facilitates a broad search of the solution space to escape local optima, while exploitation focuses on intensively searching promising regions identified through previous iterations. Effective metaheuristics dynamically manage this balance throughout the optimization process, typically emphasizing exploration in early iterations and gradually shifting toward exploitation as the search progresses [25].

Brain-Inspired Metaheuristics: Neuroscience Foundations

Brain-inspired metaheuristics represent a paradigm shift in optimization methodology by incorporating organizational principles and processing mechanisms observed in the human brain. Unlike traditional nature-inspired approaches, these algorithms leverage specific neurocognitive phenomena such as topographic organization, contextual gating, and parallel distributed processing to enhance optimization capabilities [26].

The TopoNets algorithm exemplifies this approach by implementing brain-like topography in artificial neural networks, where computational elements responsible for similar tasks are positioned in proximity, mirroring the organizational structure of the cerebral cortex. This topographic organization has demonstrated 20% improvements in computational efficiency with minimal performance degradation, making it particularly valuable for resource-constrained biomedical applications [26].

Another significant brain-inspired mechanism is context-dependent gating, which addresses the challenge of "catastrophic forgetting" in continual learning scenarios. By activating random subsets of nodes (approximately 20%) for each new task, this approach enables single networks to learn and perform hundreds of tasks with minimal accuracy loss, effectively modeling the brain's ability to leverage overlapping neural populations for multiple functions without interference [27].

Brain-inspired computing architectures further extend these principles through specialized hardware implementations. Platforms such as Tianjic, SpiNNaker, and Loihi employ decentralized many-core architectures that offer massive parallelism, high local memory bandwidth, and exceptional energy efficiency—attributes directly inspired by the brain's neural organization [7].

Comparative Performance Analysis in Biomedical Applications

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Domains

The comparative efficacy of traditional versus brain-inspired metaheuristics can be quantitatively evaluated across multiple biomedical domains using standardized performance metrics. The table below summarizes key findings from experimental studies in prominent application areas.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Metaheuristic Algorithms in Biomedical Applications

| Application Domain | Algorithm Category | Specific Algorithms | Performance Metrics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Disease Prediction | Traditional Metaheuristics | GA-optimized Random Forest (GAORF) | Prediction Accuracy: 92-95% [28] | GAORF outperformed PSO and ACO variants on Cleveland dataset |

| Brain Tumor Segmentation | Traditional Metaheuristics | PSO-optimized U-Net [18] | Dice Score: 87-92% [18] | Effective for hyperparameter tuning and architecture search |

| Brain Tumor Segmentation | Brain-Inspired Metaheuristics | BioSwarmNet [18] | Dice Score: 93-96% [18] | Superior boundary detection in heterogeneous tumor regions |

| Macroscopic Brain Modeling | Traditional Implementation | CPU-based Simulation [7] | Simulation Time: 120-240 minutes [7] | Baseline for performance comparison |

| Macroscopic Brain Modeling | Brain-Inspired Computing | TianjicX Implementation [7] | Simulation Time: 0.7-13.3 minutes [7] | 75-424x acceleration over CPU baseline |

| Medical Image Segmentation | Hybrid Approach | GWO-optimized FCM [29] | Segmentation Accuracy: 94-97% [29] | Enhanced robustness to initialization and noise |

Advantages of Brain-Inspired Approaches in Complex Biomedical Problems

Brain-inspired metaheuristics demonstrate several distinct advantages when applied to complex biomedical optimization problems. Their architectural alignment with neurobiological systems provides inherent benefits for modeling brain disorders and processing neuroimaging data. The dynamics-aware quantization framework enables accurate low-precision simulation of brain dynamics, maintaining functional fidelity while achieving significant acceleration (75-424×) over conventional CPU-based implementations [7]. This computational efficiency makes individualized brain modeling clinically feasible for applications in therapeutic intervention planning.

The exceptional continual learning capability of brain-inspired algorithms addresses a critical limitation in evolving biomedical environments. Through context-dependent gating mechanisms, these algorithms can learn up to 500 tasks with minimal performance degradation, effectively mitigating catastrophic forgetting [27]. This attribute is particularly valuable for healthcare systems that accumulate data progressively over time and require models to adapt without retraining from scratch.

Furthermore, brain-inspired metaheuristics exhibit superior performance in scenarios with limited annotated data, a common challenge in medical imaging. Algorithms such as BioSwarmNet and TopoNets demonstrate enhanced robustness in segmenting heterogeneous tumor structures from multi-modal MRI data (FLAIR, T1CE, T2), achieving Dice Similarity Coefficients of 93-96% even with small sample sizes [18] [26]. This capability stems from their inherent structural regularization and efficient feature transformation properties.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation Guidelines

Workflow for Brain-Inspired Metaheuristic Optimization

The implementation of brain-inspired metaheuristics follows a systematic workflow that integrates neuroscience principles with computational optimization. The following Graphviz diagram illustrates this pipeline:

Protocol for Brain Tumor Segmentation Optimization

A representative experimental protocol for brain tumor segmentation using brain-inspired metaheuristics involves the following methodical steps:

Multi-modal MRI Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Collect comprehensive neuroimaging data including T1-weighted, T1 contrast-enhanced (T1CE), T2-weighted, and FLAIR sequences from standardized databases (e.g., BraTS). Implement intensity normalization, skull stripping, and bias field correction to ensure data consistency. Co-register all modalities to a common spatial coordinate system to enable cross-modal feature integration [18].

Bio-Inspired Metaheuristic Configuration: Select appropriate brain-inspired algorithms such as BioSwarmNet or TopoNets based on problem constraints. For BioSwarmNet, initialize population size (typically 50-100 agents), define movement parameters based on neural excitation-inhibition principles, and establish fitness functions combining Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) and Hausdorff Distance (HD) metrics. Configure hierarchical parallelism to leverage GPU or brain-inspired computing architectures [18] [7].

Architecture Search and Hyperparameter Optimization: Deploy the metaheuristic to optimize deep learning architecture components including filter sizes (3×3 to 7×7), network depth (4-8 encoding layers), attention mechanism placement, and learning rate schedules (1e-4 to 1e-3). Utilize the algorithm's exploration-exploitation balance to efficiently navigate this high-dimensional search space [18].

Cross-Validation and Performance Assessment: Implement k-fold cross-validation (typically k=5) to ensure robust performance estimation. Evaluate segmentation accuracy using multiple metrics including DSC (targeting >0.90), Jaccard Index (JI), HD (targeting <5mm), and Average Symmetric Surface Distance (ASSD). Compare against traditional metaheuristics (PSO, GA) and baseline deep learning models to quantify performance improvements [18].

Protocol for Neural Model Parameter Identification

For biophysically detailed neural modeling, brain-inspired metaheuristics enable efficient parameter identification:

Empirical Data Integration: Acquire multi-modal neural data including fMRI, dMRI, and EEG recordings. Preprocess to extract relevant features such as functional connectivity matrices, structural connectivity graphs, and spectral power distributions [7].

Model Inversion Framework Setup: Implement a population-based metaheuristic optimization algorithm to enhance parallelization potential. Define parameter search spaces for neural mass models (e.g., Wilson-Cowan, Hopf, or Dynamic Mean-Field models) based on physiological constraints. Establish likelihood functions quantifying fit between simulated and empirical functional data [7].

Dynamics-Aware Quantization: Apply range-based group-wise quantization to manage numerical precision across different neural populations. Implement multi-timescale simulation strategies to address temporal heterogeneity in neural signals. This enables accurate low-precision simulation compatible with brain-inspired computing architectures [7].

Hierarchical Parallelism Mapping: Distribute the optimization workload across brain-inspired computing resources (e.g., TianjicX) or GPU clusters. Exploit architectural parallelism at multiple levels: individual neural populations, parameter combinations, and simulation instances. This approach has demonstrated 75-424× acceleration over conventional CPU implementations [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementation of brain-inspired metaheuristic optimization requires specialized computational frameworks and resources. The following table catalogues essential research reagents and their functions in experimental workflows.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Brain-Inspired Optimization

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brain-Inspired Computing Architectures | Tianjic, SpiNNaker, Loihi [7] | Specialized hardware for low-precision, parallel simulation of neural dynamics | Macroscopic brain modeling, real-time biomedical signal processing |

| Medical Imaging Datasets | BraTS (Brain Tumor Segmentation), ADNI (Alzheimer's Disease) [18] | Standardized, annotated medical images for algorithm training and validation | Brain tumor segmentation, neurological disorder classification |

| Optimization Frameworks | BioSwarmNet, TopoNets, CJHBA [18] [26] | Pre-implemented brain-inspired algorithm architectures with customizable components | Medical image analysis, disease diagnosis, treatment optimization |

| Neuroimaging Data Processing Tools | FSL, FreeSurfer, SPM [7] | Preprocessing and feature extraction from structural and functional MRI data | Connectome mapping, neural biomarker identification |

| Metaheuristic Benchmarking Suites | COCO, Nevergrad, Optuna [25] | Standardized environments for algorithm performance evaluation and comparison | Objective performance assessment across diverse problem domains |

Experimental Validation Metrics and Tools

Rigorous validation of brain-inspired metaheuristics requires specialized metrics and assessment tools:

Clinical Performance Metrics: For segmentation tasks, Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC) and Jaccard Index (JI) quantify spatial overlap with manual annotations; Hausdorff Distance (HD) and Average Symmetric Surface Distance (ASSD) measure boundary accuracy [18]. For predictive modeling, standard metrics include accuracy, precision, F1 score, sensitivity, specificity, and Area Under the Curve (AUC) [30] [28].

Computational Efficiency Metrics: Key indicators include execution time, speedup factor (relative to baseline), memory consumption, energy efficiency, and scalability across parallel architectures [7]. For brain-inspired hardware, performance per watt is particularly informative.

Statistical Validation Tools: Employ statistical tests including Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Mann-Whitney U, Wilcoxon signed-rank, and Kruskal-Wallis tests to establish significant differences between algorithms [25]. Cross-validation with multiple random initializations ensures result robustness.

This comprehensive analysis demonstrates that brain-inspired metaheuristic algorithms offer significant advantages over traditional approaches for complex biomedical optimization problems. Through their architectural alignment with neural systems, specialized hardware implementations, and advanced learning mechanisms, these algorithms achieve superior performance in domains such as medical image analysis, disease diagnosis, and neural modeling. The documented 75-424× acceleration in macroscopic brain modeling, alongside improved segmentation accuracy (Dice scores of 93-96%), positions brain-inspired metaheuristics as transformative tools for biomedical research and clinical applications [7] [18].

Future research directions should focus on several promising areas. Developing hybrid metaheuristics that integrate the strengths of both traditional and brain-inspired approaches could yield further performance improvements. Creating standardized benchmarking frameworks specific to biomedical applications would facilitate more objective algorithm comparisons. Extending these methods to emerging domains such as single-cell genomics, drug synergy prediction, and personalized treatment optimization represents another valuable research trajectory. Additionally, advancing the explainability and interpretability of brain-inspired algorithms will be crucial for their adoption in clinical decision-making contexts.

As biomedical problems continue to increase in complexity and scale, brain-inspired metaheuristics offer a powerful paradigm for extracting meaningful patterns and optimal solutions from high-dimensional biological data. Their continued refinement and application promise to accelerate biomedical discovery and enhance healthcare delivery across diverse clinical domains.

The quest to understand brain function requires bridging vast scales of biological organization, from the activity of individual neurons to the coordinated dynamics of entire brain regions. Theoretical models provide the essential mathematical frameworks to navigate this complexity, forging links between brain structure and function with empirical data [31]. The development of these frameworks is not merely an academic exercise; it is a critical component of brain-inspired computing and holds significant promise for identifying new therapeutic targets in drug development by enabling precise, individualized brain simulations [7]. The central challenge in computational neuroscience lies in selecting the appropriate level of abstraction. Fine-grained modeling attempts to simulate networks using microscopic neuron models as fundamental nodes, offering high biological fidelity at the cost of immense computational demands and parameters that are often difficult to constrain with current empirical data [7]. In contrast, coarse-grained modeling abstracts the collective behaviors of neuron populations into simpler dynamical systems, offering a more tractable path for integrating macroscopic data from neuroimaging modalities like fMRI, dMRI, and EEG [7]. This guide provides an in-depth examination of the core theoretical frameworks that span these scales, detailing their mathematical foundations, experimental validation, and practical application within modern computational pipelines.

Foundational Models of Neural Activity

Single-Neuron and Microcircuit Models

At the finest scale, single-neuron models describe the electrochemical dynamics that govern signal generation and integration. A pivotal model in this domain is the θ-neuron, or Ermentrout–Kopell canonical model, which is the normal form for a saddle-node on a limit cycle bifurcation [32]. It describes a neuron using a phase variable, ( \theta \in [0, 2\pi) ), with a spike emitted when ( \theta ) passes through ( \pi ). Its dynamics for a stimulus ( I ) are given by: [ \dot{\theta} = 1 - \cos\theta + (1 + \cos\theta)I ] The θ-neuron is formally equivalent to the Quadratic Integrate-and-Fire (QIF) model under the transformation ( v = \tan(\theta/2) ), where ( v ) represents the neuronal membrane voltage [32]. This equivalence provides a bridge between phase-based and voltage-based modeling paradigms.

Macroscopic Neural Population Models

Coarse-grained models, often called neural mass or neural population models, describe the average activity of large groups of neurons. These models are powerful tools for simulating large-scale brain dynamics and linking them to measurable signals.

Table 1: Key Macroscopic Neural Population Models

| Model Name | Core Mathematical Formulation | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Wilson-Cowan Model [7] | Coupled differential equations for interacting excitatory and inhibitory populations | Modeling population-level oscillations and bistability |

| Kuramoto Model [7] | ( \dot{\theta}i = \omegai + \frac{K}{N} \sum{j=1}^{N} \sin(\thetaj - \theta_i) ) | Studying synchronization phenomena in neural systems |

| Hopf Model [7] | Normal form for a supercritical Hopf bifurcation: ( \dot{z} = (\lambda + i\omega)z - z|z|^2 ) | Simulating brain rhythms near criticality |

| Dynamic Mean-Field (DMF) Model [7] | Describes average firing rate and synaptic gating variables of a neural population | Whole-brain simulation and model inversion with fMRI data |

A recent breakthrough is the development of next-generation neural mass models that are mathematically exact reductions of spiking neural networks, overcoming the phenomenological limitations of earlier models [32]. For a globally coupled network of QIF neurons with heterogeneous drives, the mean-field dynamics in the thermodynamic limit are described by a complex Riccati equation for a variable ( W(t) = \pi R(t) + iV(t) ), where ( R ) is the population firing rate and ( V ) is the average membrane voltage [32]: [ \dot{W} = \Delta - gW + i[\mu0 + g v{\text{syn}} - W^2] ] This exact mean-field description incorporates population synchrony as a fundamental variable, enabling the model to capture rich dynamics like event-related synchronization and desynchronization (ERS/ERD), which are crucial for interpreting neuroimaging data [32].

Figure 1: From Spiking Networks to Mean-Field Models. This workflow illustrates the exact mathematical reduction of a complex, finite-sized spiking network to a low-dimensional, next-generation mean-field model that tracks population-level observables.

A Framework for Large-Scale Brain Dynamics

The Model Inversion Pipeline

A primary application of coarse-grained models is data-driven whole-brain modeling through model inversion—the process of fitting a model's parameters to empirical data [7]. This pipeline integrates structural connectivity (e.g., from dMRI) and functional data (e.g., from fMRI) to create individualized brain models. The standard workflow involves:

- Initialization: A macroscopic model (e.g., DMF or Hopf) is initialized with an empirical structural connectivity matrix and a initial parameter set ( \Theta ).

- Simulation: The model simulates long-duration brain dynamics to generate simulated functional signals.

- Evaluation: The simulated functional connectivity is compared against the empirical functional connectivity to compute a goodness-of-fit measure.

- Parameter Update: An optimization algorithm adjusts the parameters ( \Theta ), and the process iterates from step 2 until a convergence criterion is met [7].

Computational Challenges and Accelerated Architectures

The model inversion process is notoriously computationally intensive, often requiring thousands of iterations of long simulations, which limits research efficiency and clinical translation [7]. To address this bottleneck, advanced computing architectures are now being deployed:

- Brain-Inspired Computing Chips: Architectures like SpiNNaker, Loihi, and Tianjic offer highly parallel, low-power computation. They are particularly well-suited for simulating neural dynamics but typically require low-precision computation to maximize efficiency [7].

- Graphics Processing Units (GPUs): GPUs provide massive parallelism and are widely used in medical image processing. Their application to macroscopic brain dynamics is growing, though their architectural potential has not been fully exploited [7].

A key innovation is the development of a dynamics-aware quantization framework that enables accurate low-precision simulation of brain models. This framework includes a semi-dynamic quantization strategy to handle large transient variations and range-based group-wise quantization to manage spatial heterogeneity across brain regions [7]. Experimental results demonstrate that this approach, when combined with hierarchical parallelism mapping strategies, can accelerate parallel model simulation by 75–424 times on a TianjicX brain-inspired computing chip compared to high-precision simulations on a baseline CPU, reducing total identification time to mere minutes [7].

Figure 2: The Model Inversion Workflow. The core iterative process for fitting a macroscopic brain model to an individual's empirical neuroimaging data. The simulation step (green) is the most computationally intensive and is the primary target for hardware acceleration.

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Quantitative Benchmarking of Computational Methods

Robust benchmarking is essential for advancing computational techniques in neuroscience. Systematic comparisons are used to evaluate the performance of different algorithms, from feature selection methods to hierarchical modeling approaches. A recent study comparing statistical, tree-based, and neural network approaches for hierarchical data modeling found that tree-based models (e.g., Hierarchical Random Forest) consistently outperformed others in predictive accuracy and explanation of variance while maintaining computational efficiency [33]. In contrast, neural approaches, while excelling at capturing group-level distinctions, required substantial computational resources and could exhibit prediction bias [33]. Similarly, in the realm of feature selection for detecting non-linear signals, traditional methods like Random Forests, TreeShap, mRMR, and LassoNet were found to be more reliable than many deep learning-based feature selection and saliency map methods, especially when quantifying the relevance of a few non-linearly-entangled predictive features diluted in a large number of irrelevant noisy variables [34].

Synthetic Data for Controlled Validation

The use of synthetic datasets with known ground truth is a critical methodology for quantitatively evaluating the performance of feature selection and modeling techniques [34]. These datasets are purposely constructed to pose specific challenges:

- The RING Dataset: Tests the ability to recognize a circular, non-linear decision boundary defined by two predictive features.

- The XOR Dataset: Presents the archetypal non-linearly separable problem where features are only informative when considered synergistically.

- The RING+XOR Dataset: Combines predictive features from RING and XOR to create a more complex challenge with four relevant features, preventing bias towards methods that favor small feature sets [34].

These datasets allow researchers to know precisely which features are relevant, providing a solid ground truth for benchmarking the reliability of different computational approaches [34].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item/Resource | Function/Role in Research |

|---|---|

| Synthetic Benchmark Datasets (RING, XOR, etc.) [34] | Provide a controlled ground truth for quantitatively validating feature selection methods and model performance. |

| Population-Dynamics-Aware Quantization Framework [7] | Enables accurate simulation of brain models on low-precision hardware (e.g., brain-inspired chips), dramatically accelerating computation. |

| Hierarchical Parallelism Mapping [7] | A system engineering strategy to exploit parallel resources of advanced computing architectures (GPUs, brain-inspired chips) for brain model simulation. |

| Mean-Field Reduction Techniques (Ott-Antonsen, Montbrió et al.) [32] | Mathematical methods for deriving exact low-dimensional equations that describe the macroscopic dynamics of large spiking neural networks. |

| Model Inversion Pipeline [7] | The overarching workflow for fitting model parameters to empirical data, integrating multi-modal neuroimaging data into a unified modeling framework. |

Theoretical frameworks for neural modeling, from single neurons to large-scale populations, provide an indispensable foundation for understanding brain function and developing brain-inspired computing paradigms. The field is moving decisively towards coarse-grained, multi-scale approaches that are tightly constrained by empirical data and powered by advanced computational architectures. The integration of exact mean-field reductions with accelerated hardware promises to make individualized brain modeling a practical tool for both basic research and clinical applications, including drug development and the design of therapeutic interventions for brain disorders. Future progress will depend on continued close collaboration between neuroscientists, mathematicians, and computer scientists to develop new models that more faithfully capture neural dynamics and to create even more efficient computational infrastructures for exploring the vast parameter spaces of the brain.

Implementation Strategies and Cutting-Edge Applications in Biomedical Research

The Neural Population Dynamics Optimization Algorithm (NPDOA) is a novel brain-inspired metaheuristic algorithm designed to solve complex optimization problems. Inspired by the dynamics of neural populations in the brain during cognitive activities, NPDOA simulates how groups of neurons collectively process information to arrive at optimal decisions [35] [36]. Metaheuristic algorithms are popular for their efficiency in tackling complex, non-linear problems that are challenging for traditional deterministic methods [36]. As a member of this class, NPDOA distinguishes itself by modeling the intricate interactions and communication patterns observed in biological neural networks, offering a fresh approach to navigating high-dimensional solution spaces [35] [37]. This technical guide details the architecture, core strategies, and experimental validation of NPDOA, framing it within a broader overview of brain-inspired optimization techniques and highlighting its potential applications, particularly in data-intensive fields like drug discovery and development [38] [39].

Algorithmic Architecture and Core Strategies

The NPDOA framework is built upon the concept of a neural population, where each individual in the population represents a potential solution to the optimization problem. The algorithm iteratively refines these solutions by applying three brain-inspired strategies that govern how the individuals (neurons) interact, explore the solution space, and converge towards an optimum [35] [37].

The core architecture and the interaction of its strategies can be visualized as a continuous cycle, as illustrated in the following workflow:

Attractor Trending Strategy

This strategy is responsible for local exploitation, driving the neural population towards the current best-known solutions (the "attractors") [35] [40].

- Mechanism: The algorithm identifies one or more elite individuals (attractors) in the population that exhibit high fitness. Other individuals in the population are then drawn towards these attractors through positional updates.

- Biological Analogy: This mimics the process where neural assemblies synchronize their activity around a dominant pattern, leading to a stable decision state [35].

- Mathematical Insight: The update is typically governed by equations that calculate a direction vector from an individual to the attractor, often combined with a step size parameter. This refines existing solutions and improves the algorithm's convergence accuracy [40].

Coupling Disturbance Strategy

This strategy facilitates global exploration by introducing disruptions that prevent the population from converging prematurely to local optima [35].

- Mechanism: Individuals are "coupled" with other randomly selected individuals in the population. This coupling creates a disturbance, deviating the individual's trajectory away from the current attractors.

- Biological Analogy: This simulates the cross-inhibition and complex interactions between different neural groups, which can lead to a shift in the overall network state and exploration of new activity patterns [35].

- Mathematical Insight: The disturbance is often modeled as a stochastic term or a vector derived from the difference between coupled individuals. This increases the diversity of the population and helps the algorithm escape local optima [40].

Information Projection Strategy

This strategy acts as a control mechanism, managing the transition between the explorative and exploitative phases of the algorithm [35] [37].

- Mechanism: It regulates the communication and information flow between the neural populations. Based on the progression of the search (e.g., iteration number or fitness improvement), it modulates the influence of the attractor trending and coupling disturbance strategies.