Brain-Computer Interfaces in 2025: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Applications and Future Trends

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technology, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Brain-Computer Interfaces in 2025: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Applications and Future Trends

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technology, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of BCI systems, from non-invasive EEG to invasive and semi-invasive cortical implants. The scope covers the methodological pipeline—including signal acquisition, preprocessing, feature extraction, and classification—and details transformative medical applications in rehabilitation, communication, and neuroprosthetics. The review also addresses critical challenges in signal optimization, system reliability, and clinical translation, while offering a comparative analysis of leading technologies and validation frameworks essential for transitioning from laboratory research to real-world, plug-and-play clinical and biomedical applications.

Core Principles and the Modern BCI Landscape: Signals, Systems, and Key Players

A Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) is a system that establishes a direct communication pathway between the brain's electrical activity and an external device, such as a computer or robotic limb [1]. This technology bypasses conventional neuromuscular pathways, translating neural signals into digital commands [2]. A closed-loop BCI system is characterized by its real-time operation, which includes not only decoding neural signals to control an external device but also providing feedback to the user, creating a continuous cycle of interaction between the brain and the machine [3]. This feedback is crucial for the user to adjust their mental commands and for the system to adapt its decoding algorithms, enabling precise control for applications in rehabilitation, communication, and assistive technology [3] [2]. This document details the core principles, current applications, and experimental protocols central to BCI control applications research.

Core Components and Signaling Pathway of a Closed-Loop BCI

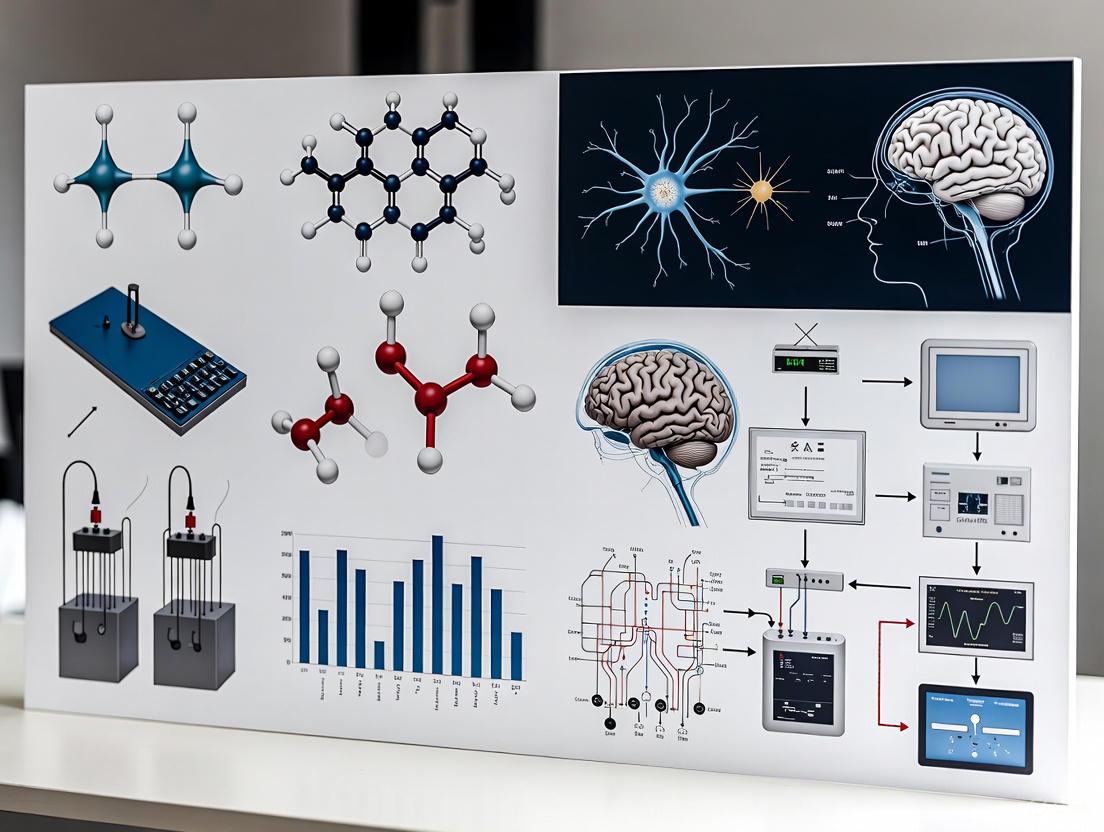

The operation of a closed-loop BCI can be conceptualized as a sequential signaling pathway. The diagram below illustrates the core workflow and the logical relationships between each component.

Closed-Loop BCI Workflow

Figure 1: The closed-loop BCI workflow. This diagram outlines the fundamental pathway from neural signal acquisition to device control and sensory feedback, which completes the loop for user adaptation.

A closed-loop BCI system functions through four standard, sequential components [3]:

- Signal Acquisition: The measurement of brain signals using various modalities. Invasive techniques, such as microelectrode arrays (e.g., Neuralink, Blackrock Neurotech), are implanted directly into the brain tissue to record the activity of individual neurons with high fidelity [2] [1]. Partially invasive techniques, like electrocorticography (ECoG), place electrodes on the surface of the brain, while endovascular approaches (e.g., Synchron's Stentrode) place electrodes within blood vessels [2] [4]. Non-invasive techniques, such as electroencephalography (EEG), record electrical activity from the scalp [3] [1].

- Signal Processing and Feature Translation: The acquired neural signals are typically noisy and must be processed. This stage involves filtering artifacts and extracting informative features (e.g., power in specific frequency bands, firing rates of neurons) [3]. Subsequently, machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms, such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and support vector machines (SVMs), translate these features into commands that represent the user's intent [3].

- Device Output: The translated commands are executed to control an external device. This could be a computer cursor, a robotic arm, a speech synthesizer, or a wheelchair [2] [1].

- Sensory Feedback: The result of the device's action is relayed back to the user in real-time, typically through visual or auditory channels. This feedback is perceived by the user's brain, allowing them to assess the outcome and subconsciously adjust their neural activity for the next command, thereby closing the loop [3] [2].

Applications and Quantitative Performance Metrics

BCI technologies are being developed for a range of medical applications, particularly for individuals with severe neurological impairments. The table below summarizes key application areas and associated performance metrics from recent research and clinical trials.

Table 1: Key BCI Applications and Performance Metrics (2020-2025)

| Application Area | Specific Task / Paradigm | Key Performance Metrics (Reported Values) | Selected Companies/Institutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Communication & Control | Text spelling via Steady-State Visual Evoked Potential (SSVEP) [5] | Information Transfer Rate (ITR): ~5.42 bits/sec [5] | Various research labs |

| Text spelling for locked-in syndrome [6] [4] | Typing speed, Accuracy, System longevity (>9 years) [6] [4] | Blackrock Neurotech, Johns Hopkins | |

| Motor Restoration & Rehabilitation | Control of robotic arm for self-feeding [1] | Task completion rate, Accuracy of movement trajectory | University of Pittsburgh |

| Combined BCI with Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES) for stroke rehab [7] | Restoration of movement, Improvement in clinical motor function scales | Various research labs | |

| Speech Decoding | Decoding speech from motor cortex activity [2] | Word decoding accuracy (~99%), Latency (<0.25 seconds) [2] | Neuralink, Paradromics |

The addressable market for these medical BCIs is significant. In the United States alone, an estimated 5.4 million people live with paralysis, and the global market for invasive BCIs is projected to be substantial, driven by these unmet clinical needs [2].

Experimental Protocols for BCI Research

Protocol: SSVEP-based BCI Speller

This protocol is adapted from the design of the BETA database, a large-scale benchmark for SSVEP-BCI applications [5].

- Objective: To design and validate a high-speed BCI speller for communication, using non-invasive EEG to record steady-state visual evoked potentials.

- Materials:

- EEG system with 64 channels.

- Visual stimulation monitor (e.g., 27-inch LED, 60Hz refresh rate).

- Software for sampled sinusoidal stimulation.

- Stimulus Design:

- Create a virtual keyboard with 40 targets (letters, numbers, symbols) arranged in a QWERTY layout.

- Implement a sampled sinusoidal stimulation method, with target frequencies ranging from 8 to 15.8 Hz.

- Ensure sufficient color contrast and spacing between targets to minimize visual interference.

- Procedure:

- Participant Preparation: Recruit participants with normal or corrected-to-normal vision. Apply EEG cap according to standard 10-20 system.

- Task: Instruct participants to focus on a cued target character on the screen. Each character will flicker at its specific frequency.

- Data Acquisition: Record EEG data across four blocks of trials. Each trial involves a cue period followed by a stimulation period.

- Signal Processing: Use frequency recognition methods like Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) to identify the target frequency the user is attending to.

- Validation: Calculate performance metrics, including classification accuracy and Information Transfer Rate (ITR), to validate the system.

Protocol: Implantable BCI for Communication in Locked-in Syndrome

This protocol summarizes the methodology from ongoing clinical trials, such as the CortiCom Study [6].

- Objective: To assess the safety and efficacy of a fully-implanted BCI system for restoring communication capabilities in patients with chronic locked-in syndrome.

- Materials:

- Implantable electrode array (e.g., ECoG grid or microelectrode array).

- Implantable wireless transmitter or transcutaneous pedestal.

- Decoding computer with specialized software.

- Participant Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria:

- Inclusion: Adults (age 22-70) with locked-in syndrome caused by brainstem stroke, trauma, or ALS; ability to communicate reliably only with caregiver assistance; cleared for brain surgery [6].

- Exclusion: Pre-existing visual impairment; presence of other diseases or implants that would contraindicate surgery or participation [6].

- Procedure:

- Surgical Implantation: A neurosurgeon implants electrodes onto the surface of the brain (ECoG) or into the cortical tissue (microelectrodes). The device is connected to a transmitter implanted in the chest.

- Post-operative Recovery: Allow for healing from surgery as per standard clinical protocols.

- Calibration & Training: Participants train with the BCI for up to 4 hours per day, several days per week, for a minimum of 6 months to one year. The system is calibrated to decode the user's neural signals associated with intent (e.g., moving a cursor, selecting a letter).

- Testing & Data Collection: Participants perform standardized communication tasks (e.g., typing, triggering an alert). Safety, accuracy, and communication speed data are collected.

- Data Analysis: Evaluate the system's performance based on typing speed, accuracy, and the incidence of adverse events.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for BCI Experiments

| Item | Function / Application in BCI Research |

|---|---|

| High-Density EEG System | Non-invasive recording of brain signals from the scalp; used in SSVEP, P300, and motor imagery paradigms [5]. |

| Microelectrode Arrays (Utah Array) | Invasive neural interfaces for recording and stimulating the activity of individual neurons or small neural populations; provide high signal fidelity [2] [1]. |

| Endovascular Stentrode | A minimally invasive electrode array delivered via blood vessels; records cortical signals without open-brain surgery [2] [4]. |

| Electrocorticography (ECoG) Grid | A partially invasive array of electrodes placed on the surface of the brain; offers a balance between signal resolution and invasiveness [1]. |

| Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) | A statistical method used for frequency recognition in SSVEP-based BCI systems [5]. |

| Deep Learning Algorithms (CNNs, RNNs) | Machine learning models for decoding complex neural signals, such as those for speech or kinematic parameters, from high-dimensional neural data [3]. |

| Robotic Arm / Assistive Device | An external actuator controlled by the BCI output to provide physical interaction with the environment for users with paralysis [1]. |

| Fmoc-Cys(tert-butoxycarnylpropyl)-OH | Fmoc-Cys(tert-butoxycarnylpropyl)-OH [102971-73-3] |

| 4-Hydroxy-2-oxoglutaric acid | 2-Hydroxy-4-oxopentanedioic Acid | High Purity |

BCI System Integration and Feedback Pathway

The integration of AI-driven decoding with the feedback loop is a critical advancement in modern BCI systems. The following diagram details the integration of the AI decoder within the broader system context and the specific data flows involved in the feedback pathway, which is essential for user adaptation and system performance.

Figure 2: AI-driven closed-loop BCI integration. This diagram emphasizes the central role of the AI/ML decoder in processing extracted neural features to predict user intent, which is then executed to generate sensory feedback, completing the adaptive loop.

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) is paramount for enhancing the performance of closed-loop BCIs [3]. Techniques such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Support Vector Machines (SVMs) improve real-time classification of neural signals for cognitive state monitoring and device control [3]. Transfer Learning (TL) is being explored to address the challenge of high variability in brain signals between users, which otherwise requires lengthy calibration sessions for each new subject [3]. The feedback loop is critical for the user to correct their mental commands, and for the AI model itself to adapt over time, creating a more robust and personalized system [3] [2].

Brain-computer interface (BCI) technology facilitates direct communication between the human brain and external devices, offering transformative potential for both clinical applications and human augmentation [8]. The core of BCI systems lies in their ability to record and interpret neural activity through various neuroimaging modalities, each with distinct characteristics, advantages, and limitations. These modalities span a spectrum from non-invasive techniques that measure brain activity externally to invasive methods that require surgical implantation of recording electrodes [9] [8].

The selection of an appropriate neuroimaging modality is paramount for BCI control applications, as it directly impacts signal quality, spatial and temporal resolution, practical implementation, and ultimately, the feasibility and performance of the BCI system [8] [10]. Non-invasive techniques like electroencephalography (EEG) and functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) offer safer, more accessible options, though often at the cost of signal resolution. In contrast, invasive methods such as electrocorticography (ECoG) and intracortical microelectrode arrays (MEAs) provide high-fidelity neural signals but carry surgical risks and are subject to long-term biocompatibility challenges [9] [8] [11].

This article provides a comparative analysis of these key neuroimaging modalities within the context of BCI control applications. It presents structured quantitative comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and visual frameworks to guide researchers and scientists in selecting and implementing the most appropriate modality for their specific BCI research and development objectives.

Comparative Analysis of Neuroimaging Modalities

The performance characteristics of neuroimaging modalities used in BCI research vary significantly across key parameters. The following table provides a systematic comparison of non-invasive and invasive modalities to inform research design decisions.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Neuroimaging Modalities for BCI Applications

| Modality | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Invasiveness | Key BCI Applications | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEG [8] [10] | Low (Centimeters) | High (Milliseconds) | Non-invasive | Communication systems, motor imagery, epilepsy monitoring, sleep studies | Low spatial resolution, susceptible to noise and artifacts |

| fNIRS [8] [10] | Medium (1-2 cm) | Low (Seconds) | Non-invasive | Cognitive state monitoring, neurofeedback, emotional recognition | Low temporal resolution, measures hemodynamic response (indirect) |

| MEG [8] [12] | High (Millimeters) | High (Milliseconds) | Non-invasive | Mapping neural networks, clinical brain mapping | Expensive, non-portable, limited access |

| fMRI [8] [12] | High (Millimeters) | Low (Seconds) | Non-invasive | Localizing brain function, neurofeedback | Expensive, non-portable, measures indirect hemodynamic response |

| ECoG [9] [8] | High (Millimeters) | High (Milliseconds) | Semi-invasive (Subdural) | Refractory epilepsy mapping, motor decoding for prosthetics | Requires craniotomy, limited cortical coverage |

| Intracortical MEA [9] [8] | Very High (Microns) | Very High (Milliseconds) | Invasive (Intracortical) | High-dimensional prosthetic control, decoding movement kinematics | Highest surgical risk, potential for tissue reaction over time |

The choice of modality often involves a trade-off between key parameters. Invasive BCIs, such as those using intracortical microelectrode arrays, provide the highest spatial and temporal resolution, capturing signals from individual neurons or small neuronal populations [9]. This enables complex control tasks, such as dexterous manipulation of robotic arms [9] [13]. Conversely, non-invasive BCIs like EEG trade off signal resolution for safety and accessibility, making them suitable for a wider user base and applications where high precision is less critical [11]. Emerging research aims to bridge this gap; for instance, a 2025 study demonstrated real-time control of a robotic hand at the individual finger level using a deep-learning-based EEG decoder, showcasing the potential for more naturalistic control with non-invasive systems [13].

Experimental Protocols for BCI Modalities

Protocol: Non-invasive BCI for Robotic Hand Control via EEG

This protocol details the methodology for achieving real-time robotic hand control at the individual finger level using an EEG-based BCI, as demonstrated by recent research [13].

- Objective: To establish a closed-loop BCI system that translates finger movement execution (ME) and motor imagery (MI) into real-time control of a robotic hand.

- Primary Modality: Non-invasive Electroencephalography (EEG).

- Experimental Setup:

- Participants: Able-bodied individuals with prior BCI experience.

- EEG Acquisition: High-density EEG system is used to record scalp potentials.

- Robotic Interface: A robotic hand prosthesis is synchronized with the BCI output.

- Visual Cueing: A computer screen provides task instructions and visual feedback.

- Procedure:

- Offline Session (Model Training):

- Participants perform cued ME and MI of individual fingers (e.g., thumb, index, pinky).

- EEG data is recorded to train a subject-specific deep learning decoder (e.g., EEGNet).

- Online Session (Real-Time Control):

- The trained model decodes EEG signals in real-time.

- Decoded outputs are converted into commands to actuate the corresponding robotic finger.

- Participants receive simultaneous visual (on-screen) and physical (robotic hand movement) feedback.

- Model Fine-Tuning:

- To mitigate inter-session variability, the base model is fine-tuned using data from the first half of each online session, which is then applied to the second half to enhance performance.

- Offline Session (Model Training):

- Data Analysis:

- Performance Metrics: Majority voting accuracy, precision, and recall for each finger class are calculated.

- Statistical Testing: A repeated-measures ANOVA is used to assess performance improvements across sessions.

Protocol: Invasive BCI for Dexterous Control via Intracortical Arrays

This protocol outlines the use of invasive microelectrode arrays for high-precision BCI control, fundamental to applications requiring dexterous manipulation [9].

- Objective: To decode movement intentions from motor cortex activity for multi-dimensional control of external devices.

- Primary Modality: Invasive Intracortical Microelectrode Arrays (MEA).

- Experimental Setup:

- Participants: Typically individuals with tetraplegia in clinical trials, or animal models (e.g., non-human primates) in foundational research.

- Implantation: A microelectrode array (e.g., 96-channel) is surgically implanted into the primary motor cortex (M1) or posterior parietal cortex.

- Signal Acquisition: A neural signal processor records action potentials (spikes) and local field potentials (LFPs).

- Procedure:

- Neural Recording: Participants are instructed to observe, imagine, or attempt to perform specific arm and hand movements.

- Decoder Calibration: Recorded neural signals are correlated with kinematic parameters (e.g., velocity, position, gripping force) to calibrate a real-time decoding algorithm (e.g., Kalman filter, Bayesian decoder).

- Closed-Loop Control: The participant uses the decoded motor commands to control a computer cursor or robotic prosthetic arm in real-time, with visual feedback guiding the task.

- Data Analysis:

- Kinematic Decoding: The accuracy of the decoder is evaluated by comparing the decoded trajectory to the intended or actual movement trajectory.

- Task Performance: Success rates in completing functional tasks (e.g., reach-and-grasp) are measured.

Signaling Pathways and System Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core logical frameworks and information pathways in BCI systems, from signal acquisition to closed-loop control.

BCI Modality Comparison Framework

This diagram outlines the hierarchical relationship between signal invasiveness and resolution, which is a fundamental concept for comparing neuroimaging modalities.

Generalized BCI System Workflow

This workflow depicts the standard signal processing pipeline common to most BCI systems, regardless of the specific acquisition modality.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful BCI experimentation relies on a suite of specialized hardware, software, and analytical tools. The following table catalogs essential components for building and testing BCI systems.

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for BCI Development

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in BCI Research |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Acquisition Hardware | EEG caps, ECoG grids/strips, Intracortical Microelectrode Arrays (e.g., Utah Array), fNIRS optodes, MEG scanner, fMRI scanner [8] [10] | Captures raw neural or hemodynamic signals from the brain with varying degrees of spatial and temporal resolution. |

| Data Processing Platforms | BrainAMP, NIRScout, OpenBCI, custom microcontroller units [10] | Amplifies, digitizes, and sometimes preprocesses the acquired neural signals. |

| Signal Processing & ML Libraries | EEGLab, BCILAB, Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch [14] [13] | Provides algorithms for preprocessing (e.g., ICA, wavelet transforms), feature extraction, and classification/decoding of brain signals. |

| Decoding Algorithms | Population Vector Algorithm, Kalman Filter, Bayesian Decoder, Convolutional Neural Networks (e.g., EEGNet) [9] [13] | Translates processed neural features into predicted user intent or kinematic parameters for device control. |

| External Actuators | Robotic arms (e.g., prosthetic limbs), computer cursors, spelling applications, virtual reality environments [9] [8] [13] | Serves as the end-effector controlled by the BCI, providing functional output and feedback to the user. |

| Integrated Dual-Modality Systems | Custom fNIRS-EEG helmets with 3D-printed or thermoplastic mounts [10] | Enables simultaneous acquisition of electrophysiological (EEG) and hemodynamic (fNIRS) data for a more comprehensive brain activity picture. |

| Methyl prednisolone-16alpha-carboxylate | Methyl prednisolone-16alpha-carboxylate | RUO | Methyl prednisolone-16alpha-carboxylate: A key metabolite for steroid metabolism and immunoassay research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 2-Bromo-3,5-dimethoxytoluene | 2-Bromo-3,5-dimethoxytoluene, CAS:13321-73-8, MF:C9H11BrO2, MW:231.09 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

A brain-computer interface (BCI) is a system that measures central nervous system activity and converts it into artificial output to change the ongoing interactions between the brain and its external or internal environment [2]. In plainer terms, a BCI translates thought into action. This document details the standard BCI signal processing pipeline, a closed-loop system comprising four sequential stages: Signal Acquisition, Preprocessing, Decoding (Feature Extraction and Translation), and Output Generation. The content herein is framed within a broader thesis on BCI control applications, providing application notes and detailed experimental protocols for researchers and scientists.

The BCI Signal Processing Pipeline: A Stage-by-Stage Analysis

The BCI closed-loop system enables direct communication between a person and a computer, allowing users to operate external devices through their brain activity [15]. The system's backbone is its sequential design: acquire, decode, execute, and provide feedback [2]. Figure 1 illustrates the complete workflow of this pipeline, from signal acquisition to the final output and feedback loop.

Figure 1. The BCI Closed-Loop Processing Pipeline. This diagram outlines the standard stages of a BCI system, from capturing brain signals to generating a device output and providing feedback to the user. The feedback loop is critical for users to adjust their mental strategy.

Stage 1: Signal Acquisition

The first stage involves measuring neural activity from the brain. Methods vary in their invasiveness and spatial resolution, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Neural Signal Acquisition Modalities in BCI Research

| Method | Invasiveness | Key Players/Examples | Key Characteristics & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electroencephalography (EEG) | Non-invasive | Kernel Flow [16] | Measures electrical activity via scalp electrodes; portable but susceptible to noise; used for Motor Imagery, SSVEP, and P300 paradigms [17]. |

| Electrocorticography (ECoG) | Minimally Invasive | Precision Neuroscience (Layer 7) [2] | Electrodes placed on the cortical surface; higher signal resolution than EEG; suitable for speech decoding and communication restoration. |

| Microelectrode Arrays | Invasive | Neuralink, Paradromics, Blackrock Neurotech [2] [16] | Micro-electrodes penetrate cortical tissue to record from individual neurons; provides the highest signal fidelity; targets severe paralysis and communication restoration. |

| Endovascular Stent Electrodes | Minimally Invasive | Synchron (Stentrode) [2] [18] | Electrodes delivered via blood vessels; balances signal quality and surgical risk; enables digital device control for paralyzed users. |

Stage 2: Preprocessing

Raw neural signals are inherently noisy. Preprocessing aims to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) by removing artifacts and isolating relevant components. A recent 2025 study systematically evaluated preprocessing techniques for EEG-based BCIs, highlighting the performance impact of different pipelines [19].

Table 2: Efficacy of Common Preprocessing Techniques in EEG-based BCIs [19]

| Preprocessing Technique | Function | Contribution to Performance & Suitability for Online BCI |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline Correction | Removes DC offset and slow drifts | Consistently provided the most beneficial preprocessing effects; recommended for online implementation. |

| Bandpass Filtering | Isolates specific frequency bands (e.g., Mu 8-13 Hz, Beta 13-30 Hz) | Consistently provided the most beneficial preprocessing effects; recommended for online implementation. |

| Surface Laplacian | Spatial filter that improves locality and reduces volume conduction | Enhanced effectiveness when used with spatial-information algorithms; recommended for online implementation. |

| Independent Component Analysis (ICA) | Separates statistically independent sources (e.g., removes eye blinks, muscle artifacts) | Useful for artifact removal; can be computationally intensive for real-time use. |

Stage 3: Decoding

The decoding stage translates preprocessed signals into meaningful commands. It consists of two substages: feature extraction and feature translation/classification.

Feature Extraction

This process identifies and quantifies informative features from the preprocessed neural data. The choice of feature is often tied to the BCI paradigm.

Table 3: Feature Extraction Methods for Key BCI Paradigms

| BCI Paradigm | Description | Relevant Features & Extraction Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Motor Imagery (MI) | User imagines a movement without executing it [20]. | Event-Related Desynchronization/Synchronization (ERD/ERS) in Mu/Beta rhythms; Common Spatial Patterns (CSP); Wavelet Transform [20]. |

| P300 | Response to a rare, target stimulus amidst frequent stimuli. | Positive deflection in EEG signal around 300ms post-stimulus; temporal filtering and averaging [17]. |

| Steady-State Visual Evoked Potential (SSVEP) | Response to a visual stimulus flickering at a fixed frequency. | Oscillatory activity at the stimulus frequency and its harmonics; Power Spectral Density (PSD) analysis [17]. |

Feature Translation and Classification

This final decoding step uses machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms to map the extracted features to a specific output command. Table 4 compares the performance of various classifiers on a Motor Imagery task, highlighting the superiority of a hybrid deep learning model.

Table 4: Classifier Performance on Motor Imagery EEG Data [20]

| Classifier Type | Specific Model | Reported Accuracy | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional ML | Random Forest (RF) | 91.00% | Achieved the highest accuracy among traditional classifiers tested. |

| Traditional ML | Support Vector Classifier (SVC) | (Reported, value not given) | A commonly used, robust classifier for BCI. |

| Traditional ML | k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | (Reported, value not given) | Performance can be sensitive to feature scaling. |

| Deep Learning | Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | 88.18% | Excels at extracting spatial features from EEG. |

| Deep Learning | Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) | 16.13% | Poor performance alone on this specific task. |

| Deep Learning | Hybrid CNN-LSTM | 96.06% | Proposed model; combines spatial (CNN) and temporal (LSTM) feature extraction. |

Stage 4: Output Generation and Feedback

The classified intent is converted into a command for an external device. Examples include moving a robotic arm, controlling a wheelchair, typing text, or generating synthetic speech [2]. A key advancement in 2025 was Synchron's BCI integration with Apple's BCI Human Interface Device profile, allowing users to control Apple devices natively with their thoughts [18]. The resulting device action is fed back to the user visually or audibly, closing the loop and enabling the user to refine their mental commands for improved control.

Experimental Protocol: Decoding Inner Speech from Motor Cortical Activity

Background and Objective

Restoring communication is a primary goal of invasive BCI research. While decoding attempted speech has been successful, it can be fatiguing for users. This protocol, based on a recent 2025 Stanford study, details a methodology for decoding inner speech (imagined speech without movement) from signals in the motor cortex, a step toward more fluent and comfortable communication BCIs [21].

Figure 2 visualizes the experimental workflow for this inner speech decoding study.

Figure 2. Experimental Workflow for Inner Speech Decoding. This protocol involves implanting microelectrode arrays in the motor cortex of participants with severe speech impairments to record neural activity during both attempted and inner speech.

Detailed Methodology

Participants and Surgical Preparation

- Participants: Recruit individuals with severe speech and motor impairments (e.g., from ALS, brainstem stroke, or spinal cord injury). The Stanford study included four such participants [21].

- Implantation: Under regulatory and ethical approval, implant microelectrode arrays (e.g., the Utah array, smaller than a pea) onto the surface of the brain in regions of the motor cortex critical for speech articulation [21].

Data Collection and Experimental Paradigm

- Stimuli Presentation: Participants are presented with visual or auditory cues of words or sentences they are to produce.

- Task Conditions:

- Attempted Speech: The participant attempts to physically speak the cued words, even if no sound is produced.

- Inner Speech: The participant silently imagines speaking the cued words, focusing on the sounds and feeling of speech without any physical attempt [21].

- Neural Recording: The implanted arrays record high-resolution neural activity during both conditions over multiple trials to build a robust dataset.

Signal Processing and Decoding

- Preprocessing: Apply bandpass filtering and other preprocessing techniques (see Table 2) to raw neural data to improve SNR.

- Feature Extraction: Identify and isolate repeatable patterns of neural activity associated with phonemes—the smallest units of speech [21].

- Machine Learning Model Training: Use machine learning (e.g., neural networks) to train a decoder. The model is trained to recognize the neural patterns associated with each phoneme and learn how to stitch them together into coherent words and sentences. The study noted that inner speech patterns were a "similar, but smaller, version of the activity patterns evoked by attempted speech" [21].

Output Generation and Privacy Mitigation

- Output: The trained decoder translates real-time neural signals into text or synthetic speech output.

- Privacy Control: To prevent accidental decoding of unintended inner thoughts, the protocol can implement a "password-protection" system. The BCI only decodes speech if the user first imagines a specific, rare passphrase (e.g., "as above, so below"), effectively acting as a mental 'enter' key [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Materials and Reagents for an Invasive Speech BCI Study

| Item | Function & Application in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Microelectrode Arrays (e.g., Utah Array) | High-density arrays for recording neural activity from populations of neurons in the cortical speech areas. The core data acquisition hardware [21]. |

| Neural Signal Amplifier & Digitizer | Conditions and converts analog microvolt-level brain signals into digital data for processing. |

| Sterile Surgical Equipment & Implant Tools | For the sterile implantation of the microelectrode arrays according to standard neurosurgical practice. |

| ML-Compatible Computing Cluster | High-performance computer with GPU acceleration for training the complex phoneme and language decoding models. |

| Stimulus Presentation Software (e.g., Psychopy) | To accurately present visual/auditory cues to the participant and synchronize them with neural data recording. |

| BCI Software Platform (e.g., BCI2000, OpenViBE) | An integrated software environment for real-time data acquisition, stimulus presentation, signal processing, and decoder operation. |

The BCI signal processing pipeline provides the foundational framework for transforming neural activity into actionable commands. As of 2025, advances in electrode technology, sophisticated preprocessing pipelines, and powerful AI-driven decoding models are pushing BCIs from laboratory demonstrations toward real-world clinical applications. The experimental protocol on inner speech decoding exemplifies the field's trajectory, tackling complex challenges like decoding internal states while proactively addressing ethical concerns such as neural privacy. Future work will focus on improving the robustness, speed, and accessibility of these systems, ultimately aiming to restore fundamental abilities like communication and mobility.

Application Notes: Core Technologies and Methodologies

The commercial brain-computer interface (BCI) landscape in 2025 is defined by pioneering companies translating laboratory research into clinical-grade neurotechnology. These systems are designed to transform thought into action for patients with severe paralysis and communication deficits, employing diverse technological pathways from fully implantable intracortical arrays to endovascular electrodes [2]. The following application notes detail the core methodologies and experimental protocols from four key industry innovators.

Neuralink

- Core Technology & Mechanism: Neuralink's "Link" is a coin-sized, fully implantable device containing ultra-high-bandwidth micro-electrodes threaded into the cortical surface by a specialized robotic surgeon [2]. The system is designed for wireless operation, sealed within the skull, and aims to record from more individual neurons than prior devices to achieve high-fidelity control of digital interfaces [2] [22].

- Primary Application & Trial Status: The first product, "Telepathy," aims to enable individuals with paralysis to control computers or other digital devices through thought alone [22]. An early feasibility human trial began in January 2024. As of mid-2025, five individuals with severe paralysis have received the implant and are using it to control digital and physical devices with their thoughts [2]. A second product, "Blindsight," aimed at restoring limited vision, has received FDA breakthrough device designation [22].

Synchron

- Core Technology & Mechanism: Synchron's "Stentrode" is an endovascular BCI delivered via a catheter through the jugular vein and lodged in the superior sagittal sinus, a blood vessel draining the motor cortex [2]. This approach avoids open brain surgery by recording brain signals through the vessel wall, representing a minimally invasive alternative to craniotomy [23] [2].

- Primary Application & Trial Status: The Stentrode is designed to allow patients with paralysis to control digital devices for tasks like texting and emailing [24]. A four-patient trial demonstrated the ability to control a computer via thought, with no serious adverse events or vessel blockages reported after 12 months [2]. The company is advancing towards a pivotal clinical trial and has established partnerships with mainstream technology ecosystems [2].

Blackrock Neurotech

- Core Technology & Mechanism: Blackrock's approach is built upon the "Utah Array" (NeuroPort Electrode), a bed-of-nails style intracortical electrode that has been the cornerstone of many academic BCI studies for over two decades [25] [2]. The company provides a complete BCI ecosystem, including implantable electrodes, hardware, and software [25]. They are developing next-generation technologies like "Neuralace," a flexible lattice for less invasive cortical coverage [2].

- Primary Application & Trial Status: Blackrock's technology enables control of prosthetics, computer functions, and communication for people with paralysis [25] [26]. Their first device for clinical use, the "MoveAgain" BCI system, received an FDA Breakthrough Designation in 2021 [25]. The technology has been validated over 19+ years of human studies and is currently being used in expanding in-home trials where paralyzed users live with the BCI daily [2] [26].

Paradromics

- Core Technology & Mechanism: The "Connexus BCI" is a fully implantable, high-data-rate platform using a modular array of 421 micro-electrodes, each thinner than a human hair, to capture activity from individual neurons [27] [28]. The device features an integrated wireless transmitter implanted in the chest and is engineered for long-term stability and high bandwidth, reportedly achieving over 200 bits per second in pre-clinical models [27] [28].

- Primary Application & Trial Status: The primary initial application is the restoration of speech and computer control for people with severe motor impairments, such as those caused by ALS, stroke, or spinal cord injury [27] [29]. The company received FDA Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) approval in late 2025 for its "Connect-One" Early Feasibility Study, with the first-in-human recording successfully completed at the University of Michigan [27] [28] [29]. The clinical study is slated to begin in late 2025 across three US sites [29].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Key BCI Platform Specifications (2025)

| Company | Implant Type | Channel Count/Data Rate | Surgical Approach | Clinical Trial Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuralink | Intracortical microelectrode array | High (specifics not detailed) | Robotic-assisted craniotomy [2] | Early Feasibility Study (5 participants as of mid-2025) [2] |

| Synchron | Endovascular stent electrode | Not specified in detail | Minimally-invasive endovascular [23] [2] | Completed 4-patient trial; advancing to pivotal trial [2] |

| Blackrock Neurotech | Utah Array (intracortical) | Versatile system configurations [25] | Craniotomy [2] | MoveAgain FDA Breakthrough Designation (2021); in-home trials [25] [2] |

| Paradromics | Intracortical microelectrode array | 421 electrodes; >200 bits/sec [27] | Craniotomy (familiar to neurosurgeons) [27] [2] | FDA IDE approved; Connect-One Study starting late 2025 [27] |

Table 2: Primary Clinical Applications and Demonstrated Capabilities

| Company | Target Patient Population | Demonstrated/Planned Functional Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Neuralink | Severe paralysis [2] [22] | Control of digital and physical devices [2] |

| Synchron | Paralysis with limited mobility [24] | Computer control, texting, emailing, online access [2] [24] |

| Blackrock Neurotech | Paralysis, neurological disorders [25] | Prosthetic limb control, typing (up to 90 char/min), email, digital art, word decoding (62 words/min) [25] [26] |

| Paradromics | Severe motor impairment (ALS, stroke, SCI) with speech loss [27] [29] | Restoration of speech via text/synthesized speech, computer control [27] [28] |

Experimental Protocols

General BCI Workflow and Signal Processing Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the core, universal signal processing pathway shared by modern implantable BCI systems.

Protocol 1: Surgical Implantation and Acute Recording

This protocol outlines the common procedures for the surgical implantation of intracortical BCIs, such as those from Paradromics and Blackrock Neurotech, and the subsequent acute neural recording validation [27] [28] [29].

- Objective: To surgically implant a BCI device and verify its functionality by recording neural signals in an acute setting.

- Materials:

- Procedure:

- Patient Preparation and Sterile Draping: Position the patient and prepare the surgical site according to standard neurosurgical protocols.

- Craniotomy: Perform a craniotomy to expose the dura mater over the target brain region (e.g., motor cortex for movement, speech cortex for communication) [2].

- Device Implantation:

- Closure and Signal Verification: Secure the device and partially close the surgical site. Connect the implant to the neural signal processor to verify the presence of multi-unit or single-unit neural activity.

- Acute Recording (if applicable): In an intraoperative setting, such as during epilepsy surgery, present the patient with motor or cognitive tasks (e.g., attempting to move a hand, imagine speaking) to confirm that task-modulated neural signals are being recorded [28].

- Conclusion: The device may be explanted (in an acute study) or fully secured for long-term implantation based on the study protocol [28].

Protocol 2: Chronic In-Home BCI Use for Communication

This protocol describes the methodology for deploying a BCI system for long-term, at-home use to restore communication, representative of the trials conducted by Blackrock Neurotech and planned by Paradromics [2] [26].

- Objective: To evaluate the safety and efficacy of a chronically implanted BCI in enabling computer control and communication for a paralyzed individual in their home environment.

- Materials:

- Chronically Implanted BCI System: e.g., Blackrock's MoveAgain system or Paradromics' Connexus BCI with its chest-mounted receiver [25] [27].

- External Decoder/Computer System: A computer equipped with the BCI software suite for real-time decoding of neural signals into control commands [25] [27].

- Calibration Software: Custom software for daily decoder calibration.

- Data Logging System: To record neural data, performance metrics, and user outcomes.

- Procedure:

- System Setup and Calibration: Each day, the participant dons the external headstage or connects wirelessly to the implant. A calibration routine is run where the participant is instructed to attempt specific motor imagery (e.g., moving a cursor left/right, attempting to speak) while the system records the corresponding neural patterns [25] [26].

- Decoder Training: Machine learning models are trained on the calibration data to create a personalized decoder that maps neural activity to intended outputs [2].

- Task Performance (Closed-Loop Control): The participant uses the trained decoder to perform functional tasks in a closed-loop setting. This includes:

- Data Collection and Outcome Measures:

- Long-Term Follow-up: Data is collected over months to years to assess system stability, performance improvement, and long-term safety [2] [26].

Protocol-Specific Visual Workflow

The following diagram details the specific workflow for chronic in-home BCI deployment and data collection as outlined in Protocol 2.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Components for BCI Research & Development

| Item / Component | Function / Rationale | Exemplar Product / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Implantable Electrode Array | The primary transducer for recording neural electrical activity; design dictates signal fidelity and longevity. | Utah Array (Blackrock) [25] [2], Stentrode (Synchron) [2], Connexus Micro-Electrodes (Paradromics) [27]. |

| Neural Signal Processor | Hardware for amplifying, filtering, and digitizing microvolt-level neural signals from electrodes. | Blackrock's headstage and acquisition hardware [25]. A critical component of the complete BCI ecosystem. |

| Biocompatible Materials | Ensures long-term safety and stability of the implant by minimizing immune response and tissue damage. | Use of titanium, platinum-iridium, and flexible, biocompatible polymers [27] [2]. |

| Decoding Software Suite | Machine learning algorithms to translate raw neural data into predicted user intent (e.g., movement, speech). | Advanced AI software for decoding intended speech or movement [27] [2]. |

| Surgical Tooling | Enables precise and repeatable implantation of the BCI device. | Robotic surgeon (Neuralink) [2] or standard neurosurgical tools for craniotomy. |

| (1,4-Dimethylpiperazin-2-yl)methanol | (1,4-Dimethylpiperazin-2-yl)methanol, CAS:14675-44-6, MF:C7H16N2O, MW:144.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Diethylene glycol monostearate | Diethylene glycol monostearate, CAS:106-11-6, MF:C22H44O4, MW:372.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) technology, establishing a direct communication pathway between the human brain and external devices, is poised to fundamentally transform human-machine interaction [30] [31]. This field, progressing from foundational assistive applications to potential cognitive and sensory enhancement, represents a critical frontier in neurotechnology research and development. This document provides a detailed analysis of the projected market landscape from 2025 to 2040, examines the evolving policy and regulatory environment, and offers standardized experimental protocols for key BCI control applications. It is structured to serve researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals by synthesizing quantitative market data, delineating clear methodological frameworks, and cataloging essential research tools, thereby supporting advanced research within a broader thesis on BCI control applications.

Global Market Landscape and Growth Projections

The global BCI market is on a trajectory of significant expansion, driven by technological advancements, increasing investment, and the broadening of applications beyond healthcare into consumer and industrial sectors [30] [32]. Market analyses consistently project a robust Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR), with variations in absolute figures reflecting different methodological scopes and regional focuses. The following tables summarize key quantitative projections and market segmentations to facilitate comparative analysis.

Table 1: Global BCI Market Size Projections (2024-2040)

| Base Year (Value) | Projection Year (Value) | Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | Source / Region Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| USD 2.09 Billion (2024) [33] | USD 8.73 Billion (2033) [33] | 15.13% [33] | Global Projection |

| USD 3.21 Billion (2025) [32] | USD 12.87 Billion (2034) [32] | 16.7% [32] | Global Projection |

| Not Specified | USD 70-200 Billion (2030-2040) [34] | Not Specified | McKinsey Global Forecast |

| ~RMB 1 Billion (2023) [34] | >RMB 120 Billion (2040) [34] | ~26% [34] | China Domestic Market |

Table 2: BCI Market Segmentation by Type, Application, and Region (2024-2025)

| Segmentation Category | Leading Segment | High-Growth Segment | Key Regional Leader | Fastest-Growing Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product Type | Non-Invasive BCIs (Largest share in 2024) [32] [33] | Invasive BCIs (Significant growth predicted) [32] | North America (Advanced infrastructure & key players) [32] [33] | Asia-Pacific (Projected fastest growth) [32] |

| Application | Healthcare (58.6% share in 2022) [32] | Smart Home Control (CAGR of 19.4%) [32] |

The market's momentum is fueled by several key drivers. The growing prevalence of neurodegenerative disorders (e.g., ALS, Parkinson's, spinal cord injuries) creates a pressing need for assistive and rehabilitative technologies [30] [32]. Concurrently, technological advancements in artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML) for signal decoding, and miniaturization of wireless systems are enhancing BCI performance and usability [30] [31]. Increased funding from both government entities and private venture capital is further accelerating R&D and commercialization, with notable investments in companies like Neuralink, Synchron, and Precision Neuroscience [30] [31] [32].

Policy and Regulatory Initiatives

The regulatory landscape for BCI is complex and evolving, aiming to balance innovation with safety, efficacy, and ethical considerations. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) plays a pivotal role, exemplified by its "Breakthrough Device" program which accelerates the development and review of devices for life-threatening or irreversibly debilitating conditions [32]. Recent FDA approvals for limited commercial use of devices from companies like Precision Neuroscience mark significant regulatory milestones [32].

Globally, policy initiatives are increasingly recognizing BCI as a strategic technology. The European Union has its own regulatory frameworks for medical devices and data privacy that impact BCI development and deployment [30]. Notably, China's 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) explicitly identified BCI as a key technology for the first time, emphasizing brain-machine fusion as a national priority and spurring regional support and industrial alliances [34]. This policy direction is catalyzing the growth of the domestic BCI ecosystem, involving major tech firms and research institutions.

Beyond medical device regulation, data privacy and security present a formidable regulatory challenge. The collection and interpretation of neural data raise profound questions about brain privacy and ownership [30] [32]. Cybersecurity threats to BCI devices, which could potentially allow malicious actors to manipulate a user's actions, are a critical concern that regulatory frameworks must address [32]. Furthermore, the potential for cognitive enhancement introduces complex ethical issues related to cognitive liberty, equity, and what it means to be human, necessitating ongoing dialogue among scientists, ethicists, and policymakers [30].

Experimental Protocols for BCI Control Applications

This section outlines standardized protocols for common BCI control paradigms, providing a reproducible methodology for research in this domain.

Protocol: P300-Based Spelling and Smart Home Control Application

1. Objective: To establish a non-invasive BCI system enabling users to communicate via a virtual keyboard and control basic smart home devices using the P300 event-related potential.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- EEG Acquisition System: A high-density EEG system (e.g., 32-channel or 64-channel) with active or passive electrodes.

- Electrolyte Gel: Conductive electrolyte gel to ensure impedance below 10 kΩ.

- Stimulus Presentation Software: Software capable of rendering a visual P300 speller matrix (e.g., 6x6 grid of characters and icons) and delivering precise timing markers.

- Signal Processing Unit: A computer with installed BCI software (e.g., BCI2000, OpenVibe) for real-time signal processing.

- Smart Home Interface: A custom API or middleware (e.g., based on IoT protocols like MQTT) to translate BCI commands into actions for devices like lights, TVs, or blinds.

3. Methodology: 1. Subject Preparation: Position the subject 60-80 cm from the visual stimulus monitor. Apply the EEG cap according to the 10-20 international system. Fill electrodes with conductive gel, focusing on sites Pz, Cz, and Oz, and ensure impedance is optimized. 2. System Calibration: Initiate a calibration run. Instruct the subject to focus on a pre-determined sequence of characters as they are highlighted. Record at least 10-15 repetitions of each target character to train a classifier (e.g., Linear Discriminant Analysis or Support Vector Machine). 3. Real-Time Operation: In the operational phase, the rows and columns of the speller matrix are randomly intensified. The system acquires EEG signals, extracts features (typically time-domain averaging or wavelet transforms), and applies the trained classifier to detect the P300 potential, thereby identifying the character or icon the user is focusing on. 4. Smart Home Integration: Map specific commands (e.g., "LIGHT ON," "TV OFF") to icons within the speller matrix. Upon selection, the BCI software triggers the corresponding command via the smart home interface.

4. Data Analysis: * Accuracy: Calculate the character selection accuracy as (Number of Correct Selections / Total Number of Selections) * 100. * Information Transfer Rate (ITR): Compute ITR in bits per minute to quantify communication bandwidth, accounting for both accuracy and speed.

Protocol: Motor Imagery (MI) for Neuroprosthetic Control

1. Objective: To implement a non-invasive BCI that decodes hand motor imagery (MI) patterns to control a robotic or prosthetic limb.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- EEG System: A multi-channel EEG system with a focus on sensors over the sensorimotor cortex (e.g., C3, Cz, C4).

- Visual Feedback Display: A monitor to provide real-time feedback on the MI task and prosthetic device state.

- Prosthetic Arm/Output Device: A robotic arm or a virtual representation that can be controlled via digital commands.

- Signal Processing Software: Software capable of processing sensorimotor rhythms (e.g., Mu/Beta rhythms) and running classification algorithms in real-time.

3. Methodology: 1. Subject Preparation & Screening: Apply the EEG cap as in Protocol 4.1. Screen the subject for their ability to generate distinct sensorimotor rhythm patterns during kinesthetic motor imagery (e.g., imagining squeezing a ball with the right hand). 2. Classifier Training: Conduct a training session. Present visual cues (e.g., arrows) instructing the subject to imagine either "Right-Hand Movement" or "Rest." Record EEG data for multiple trials (e.g., 80-100 trials per class). Use this data to train a spatial filter (e.g., Common Spatial Patterns) and a classifier to distinguish between the two mental states. 3. Closed-Loop Control with Feedback: In the closed-loop phase, the subject is presented with a goal (e.g., "grasp the object"). The system processes the EEG signals in real-time, applies the trained model, and translates the decoded intent into a proportional or discrete command for the prosthetic device. Visual feedback of the moving prosthetic is provided to the user to facilitate learning and improve control.

4. Data Analysis: * Offline Accuracy: Assess the classifier's performance using cross-validation on the calibration data. * Online Performance: Evaluate the success rate in completing specific tasks (e.g., reaching and grasping an object) within a time limit. * Electrophysiological Changes: Analyze event-related desynchronization (ERD) in the Mu/Beta bands over the contralateral sensorimotor cortex during MI.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for BCI research, particularly for the protocols described above.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for BCI Experiments

| Item Name | Function / Application in BCI Research |

|---|---|

| Electroencephalography (EEG) System with Ag/AgCl Electrodes | The primary hardware for non-invasive recording of electrical activity from the scalp. Used for acquiring P300, Motor Imagery, and other evoked or spontaneous potentials [30]. |

| Conductive Electrolyte Gel | Improves electrical conductivity between the scalp and EEG electrodes, crucial for reducing impedance and obtaining high-quality, low-noise neural signals. |

| Electrocorticography (ECoG) Grid/Strip | A semi-invasive neural interface placed on the surface of the cortex. Offers higher spatial resolution and signal fidelity than EEG for more precise control applications [30]. |

| Intracortical Microelectrode Array (e.g., Utah Array) | Invasive neural interface implanted into the cortex to record single-neuron or multi-unit activity. Provides the highest signal resolution for complex prosthetic control [30]. |

| Signal Processing & BCI Software Platform (e.g., BCI2000, OpenVibe) | Software environment for designing experiments, acquiring data, implementing real-time signal processing pipelines (filtering, feature extraction, classification), and providing feedback. |

| Stimulus Presentation Software (e.g., Psychtoolbox, Presentation) | Software for rendering and controlling visual, auditory, or somatosensory stimuli with millisecond precision, ensuring accurate synchronization with neural data acquisition. |

| Classifiers (LDA, SVM, Deep Learning Models) | Algorithms that translate extracted neural features into device control commands. LDA and SVM are common for P300 and MI; deep learning is emerging for more complex decoding [32]. |

| Methyl-1,2-cyclopentene oxide | Methyl-1,2-cyclopentene oxide, CAS:16240-42-9, MF:C6H10O, MW:98.14 g/mol |

| N-(6-FORMYLPYRIDIN-2-YL)PIVALAMIDE | N-(6-FORMYLPYRIDIN-2-YL)PIVALAMIDE, CAS:372948-82-8, MF:C11H14N2O2, MW:206.24 g/mol |

BCI Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and core components of a standard BCI experiment, from signal acquisition to closed-loop feedback.

Diagram 1: BCI System Workflow. The process is a closed loop, beginning with Neural Signal Generation (e.g., from a user performing motor imagery), which is captured by Signal Acquisition Hardware. The raw data undergoes Preprocessing and Feature Extraction before a Classification/Decoding algorithm translates the neural patterns into a Device Command. The resulting User Feedback completes the loop, allowing the user to adapt their brain activity, a process known as neurofeedback or closed-loop learning.

From Signal to Action: BCI Methodologies and Their Transformative Medical Applications

In Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) research, the efficacy of control applications is fundamentally constrained by the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of neural recordings. Electroencephalography (EEG), a predominant non-invasive BCI modality, is particularly susceptible to contaminating artifacts of both physiological and non-physiological origin. These artifacts can obscure critical neural patterns, thereby degrading BCI performance and reliability. Consequently, advanced signal processing techniques for artifact removal are indispensable for enhancing the fidelity of neural signals. This application note provides a detailed examination of three cornerstone methodologies—Independent Component Analysis (ICA), Wavelet Transform (WT), and Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA)—framed within the context of BCI control applications. We elucidate the underlying principles, present structured experimental protocols, and offer a comparative analysis to guide researchers and scientists in selecting and implementing optimal artifact removal strategies for their specific BCI paradigms.

Theoretical Foundations of Artifact Removal Techniques

Independent Component Analysis (ICA)

ICA is a blind source separation (BSS) technique that decomposes a multivariate signal into additive, statistically independent sub-components. The core assumption is that the recorded multi-channel EEG signal is a linear mixture of independent sources originating from the brain and various artifactual sources (e.g., ocular movements, muscle activity, cardiac rhythms). The model is formalized as X = AS, where X is the observed data matrix, A is the unknown mixing matrix, and S contains the underlying independent sources. The objective of ICA is to find a de-mixing matrix W such that Y = WX provides an estimate of the original source signals S [35] [14].

A critical step in ICA-based artifact removal is the identification and rejection of artifactual components. This often relies on measuring the non-Gaussianity of the components, frequently approximated using negentropy (J(y) = H(yGauss) - H(y)), where H is the differential entropy. Components with high negentropy are typically considered non-Gaussian and are candidates for being neural signals, though certain artifacts like eye blinks also exhibit high non-Gaussianity, necessitating careful inspection [35]. While powerful, ICA requires manual or semi-automated component classification, can be computationally intensive, and its performance is sensitive to the amount of available data [14].

Wavelet Transform (WT)

Wavelet Transform provides a multi-resolution analysis of a signal by decomposing it into basis functions (wavelets) that are localized in both time and frequency. This is a significant advantage over Fourier-based methods for processing non-stationary signals like EEG. The Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) is commonly used, employing a series of high-pass and low-pass filters to break down a signal into approximation (low-frequency) and detail (high-frequency) coefficients at different scales [36] [14].

Denoising in the wavelet domain typically involves thresholding the detail coefficients associated with noise. A common hybrid approach combines DWT with scalar quantization (DWTSQ) to both denoise and compress EEG signals, improving transmission efficiency in wireless BCI systems [36]. Advanced variants, such as denoising in the fractional wavelet domain using adaptive models, have been developed to better preserve the non-stationary and quasi-stationary components of the EEG while effectively removing noise [37]. The choice of the mother wavelet and the thresholding function (e.g., soft, hard) are critical parameters that influence the denoising performance.

Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA)

While CCA is widely known as a feature extraction method for Steady-State Visual Evoked Potentials (SSVEPs), it also serves as a robust tool for artifact removal. CCA is a multivariate statistical method that finds linear combinations of two sets of variables that maximize the correlation between them. In the context of artifact removal, CCA can separate neural activity from artifacts by maximizing the correlation between the EEG signal and reference signals, thereby isolating artifact components [14].

Its utility is further demonstrated in hybrid spatial filtering methods. For instance, the CCA of Task-Related Components (CCAoTRC) method applies a spatial filter derived from Task-Related Component Analysis (TRCA) to enhance the SNR of the data before employing CCA for frequency recognition. This hybrid approach has been shown to be particularly effective for data recorded outside electromagnetic shields, making it suitable for real-world BCI applications [38].

Application Notes and Comparative Analysis

The selection of an appropriate artifact removal technique is highly dependent on the specific BCI paradigm, the nature of the artifacts, and the required signal integrity for downstream decoding tasks.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Artifact Removal Techniques in BCI Applications

| Technique | Primary Mechanism | Best-Suited BCI Paradigms | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICA | Blind source separation into independent components. | P300, Motor Imagery, general pre-processing. | Effective separation of neural and artifactual sources; does not require reference signals [39]. | Manual component classification is often needed; computationally intensive; performance depends on data quantity [14]. |

| Wavelet Transform | Multi-resolution time-frequency analysis and thresholding. | Epileptic spike detection, P300, data compression for transmission [36] [37]. | Preserves temporal localization of transients; suitable for non-stationary signals; allows for signal compression. | Selection of wavelet basis and threshold is critical and can be complex; may distort signal if not optimized [14]. |

| Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) | Maximizes correlation with reference signals or between signal subsets. | SSVEP frequency recognition, artifact removal in noisy environments [38] [14]. | High efficiency and robustness; can be combined with individual calibration data to improve performance [40]. | Standard CCA may be sensitive to noise; reference signals may not capture all individual variations. |

| Hybrid Methods (e.g., CCAoTRC, H-TRCCA) | Combines spatial filtering (e.g., TRCA) with CCA. | SSVEP, especially with limited training data or low SNR [38] [41]. | Leverages strengths of multiple methods; superior performance and robustness with limited calibration data [41]. | Increased algorithmic complexity; may require calibration data. |

Table 2: Impact of Artifact Removal on BCI Performance Metrics

| Study Focus | Technique Used | Key Performance Outcome | Implication for BCI Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robustness of ICA Artifact Removal [39] | Automated ICA Classifier | Little influence on average BCI performance with state-of-the-art methods; strong individual variation when using slow motor-related features. | Highlights the need for personalized processing pipelines, especially in motor rehabilitation BCIs. |

| SSVEP Recognition with Limited Data [41] | Hybrid H-TRCCA (CCA+TRCA) | Achieved 91.44% accuracy and 188.36 bits/min ITR using only two training trials. | Enables faster setup and higher usability for SSVEP-based communication and control systems. |

| Denoising for Signal Transmission [36] | DWT based Scalar Quantization | Improved SNR and classification accuracy for transmitted EEG signals. | Critical for the development of robust wireless and wearable BCI systems. |

| SSVEP in Noisy, Real-World Conditions [38] | CCAoTRC (CCA with TRC spatial filter) | Increased Wide-band SNR by 0.66 dB; achieved 70.94% accuracy in non-shielded environments. | Facilitates the deployment of practical BCIs outside controlled laboratory settings. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates a recommended, multi-stage approach for artifact removal in a BCI system, integrating the discussed techniques.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: ICA for Ocular and Muscle Artifact Removal

This protocol is designed for the removal of common physiological artifacts, such as those from eye blinks (EOG) and muscle activity (EMG), from continuous EEG data.

1. Preprocessing:

- Data Import: Load raw EEG data (e.g., .set, .edf, or .xls format).

- Filtering: Apply a bandpass filter (e.g., 1-40 Hz) to remove DC offset and high-frequency noise.

- Re-referencing: Re-reference the data to the average of all electrodes or a specific reference (e.g., mastoids).

2. ICA Decomposition:

- Execute ICA decomposition using an algorithm such as Infomax or FastICA. The input is the preprocessed, multi-channel EEG data matrix.

- Critical parameters include the stopping convergence value (e.g., 1e-7) and maximum number of iterations (e.g., 1000).

3. Component Classification:

- Visualize independent components (ICs) by their topography, time course, and frequency spectrum.

- Identify artifactual components:

- Ocular Artifacts: Characterized by strong frontal scalp maps and large, low-frequency deflections in the time series.

- Muscle Artifacts: Exhibit high-frequency "spiky" activity in the time series and a broadband frequency spectrum.

- Utilize automated classifiers (e.g., ICLabel, EEGLAB plug-ins) or manual expert labeling to flag components for rejection [39].

4. Signal Reconstruction:

- Project the data back to the sensor space, excluding the artifactual components. This involves multiplying the de-mixing matrix Wâ»Â¹ by the source matrix S with the artifact components set to zero.

Protocol 2: Wavelet-Based Denoising for P300 Enhancement

This protocol focuses on enhancing the SNR of event-related potentials like the P300, which is crucial for P300 spellers.

1. Signal Preparation:

- Epoching: Segment the continuous EEG into epochs time-locked to the stimulus onset (e.g., -100 ms to 800 ms).

- Baseline Correction: Remove the mean baseline (-100 ms to 0 ms) from each epoch.

2. Wavelet Decomposition:

- Select a mother wavelet (e.g., Daubechies 4 'db4' is often suitable for EEG).

- Decompose each single-trial epoch into multiple levels (e.g., 5-8 levels) using DWT, producing one set of approximation coefficients and multiple sets of detail coefficients.

3. Thresholding and Denoising:

- Apply a thresholding rule (e.g., adaptive thresholding based on negentropy as in [35] or Stein's Unbiased Risk Estimate (SURE)) to the detail coefficients at each level.

- Use a thresholding function (soft or hard) to suppress coefficients below the threshold, which are presumed to be noise.

4. Signal Reconstruction:

- Reconstruct the denoised single-trial P300 epoch from the thresholded wavelet coefficients using the inverse DWT.

- Average the denoised single-trials to obtain a clean ERP waveform with an enhanced P300 component.

Protocol 3: Hybrid CCA-TRCA for SSVEP Recognition

This protocol outlines a hybrid method for robust SSVEP target identification, which inherently handles artifacts through optimized spatial filtering.

1. Data Preparation and Preprocessing:

- Training Data: Collect calibration data where the user focuses on known, flickering targets.

- Epoching: Segment EEG data into trials corresponding to each stimulation event.

- Filter Bank Decomposition (Optional): Decompose the EEG signals into sub-band components (e.g., covering harmonics) to leverage filter bank analysis [40].

2. Spatial Filter Construction:

- TRCA Filter: Compute a spatial filter W_TRCA that maximizes the inter-trial covariance of the training data for each stimulus frequency, enhancing task-related components [41].

- CCA Reference Templates: Generate reference signals Y for each stimulus frequency

fas sine-cosine pairs at the fundamental and harmonic frequencies: Y = [sin(2Ï€ft), cos(2Ï€ft), ..., sin(2Ï€Nhft), cos(2Ï€Nhft)]áµ€.

3. Target Identification during Testing:

- For a test epoch X, calculate the correlation coefficients between the spatially filtered test data and the reference signals for all possible frequencies.

- Candidate Selection: Use a clustering algorithm (e.g., k-means++) on the correlation coefficients to identify candidate stimuli with the highest average correlations [41].

- Decision Making: For each candidate stimulus, sum the correlation values from CCA-based filters and combine them with the correlation coefficient from the TRCA-based filter. The target frequency is identified as the one with the highest combined correlation value.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for BCI Artifact Removal Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tool / Software / Dataset | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Libraries | EEGLAB (with ICLabel, PREP pipeline) | Provides a complete interactive environment for ICA, including decomposition, visualization, and automated component labeling [39]. |

| BCILAB, MNE-Python | Offers comprehensive toolboxes for BCI research, including implementations of CCA, TRCA, and wavelet analysis. | |

| MATLAB Signal Processing Toolbox, PyWavelets | Supplies built-in functions for performing Discrete Wavelet Transform and various thresholding techniques. | |

| Benchmark Datasets | BCI Competition Datasets (e.g., 2003, P300) | Standardized data for developing and benchmarking denoising algorithms, such as for P300 enhancement [35]. |

| Benchmark Dataset (Wang et al., 2016) | Contains SSVEP data from 35 subjects, essential for validating SSVEP frequency recognition methods like H-TRCCA [41]. | |

| BETA Dataset (Liu et al., 2020) | Comprises SSVEP data from 70 subjects recorded in a non-laboratory environment, ideal for testing robustness and real-world applicability [38] [41]. | |

| Hardware & Acquisition | High-density EEG Systems (64+ channels) | Provides sufficient spatial information for effective source separation using ICA and spatial filtering techniques. |

| Wearable, Wireless EEG Headsets | Target systems for which efficient denoising and compression algorithms (e.g., DWTSQ) are developed [36]. | |

| 2-Ethyl-6-nitroquinolin-4-amine | 2-Ethyl-6-nitroquinolin-4-amine, CAS:1388727-03-4, MF:C11H11N3O2, MW:217.22 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (4-Bromo-3-methylphenyl)thiourea | (4-Bromo-3-methylphenyl)thiourea |

The evolution of Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) represents one of the most significant advancements at the intersection of neuroscience and artificial intelligence. At the core of this technology lies the challenge of accurately interpreting neural activity to enable direct communication between the brain and external devices. This process critically depends on sophisticated computational pipelines for feature extraction and intent decoding – the translation of raw, often noisy, brain signals into actionable commands. The performance of modern BCIs hinges on deploying advanced machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms that can navigate the complexities of neural data. These methodologies are foundational to developing clinical-grade neurotechnology for conditions such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), spinal cord injuries, and stroke, offering a pathway to restore communication and mobility for severely paralyzed individuals [2] [42].

Theoretical Foundations of Neural Signal Processing

The BCI pipeline systematically converts brain signals into device control, comprising stages of signal acquisition, preprocessing, feature extraction, decoding, and output with feedback.

The BCI Signal Processing Pipeline

A standardized BCI pipeline involves sequential stages: signal acquisition (collecting raw neural data), pre-processing (filtering and artifact removal), feature extraction (identifying discriminative patterns), decoding/classification (translating features into intent), and output with feedback (executing commands and providing user feedback) [2]. This closed-loop architecture is the backbone of current BCI research, enabling users to adapt their mental strategies based on system performance.

Signal Acquisition Paradigms

Brain signals can be captured through various modalities, each with distinct trade-offs between invasiveness and spatial-temporal resolution. Electroencephalography (EEG), a non-invasive technique, measures electrical potentials from the scalp and is widely used due to its portability and high temporal resolution [43] [17]. In contrast, intracortical microelectrode arrays (e.g., the Utah array or Neuralink's chip) are implanted directly into the brain tissue, providing high-fidelity signals from individual neurons but requiring neurosurgery [2]. Endovascular BCIs (e.g., Synchron's Stentrode) offer a middle ground, recording cortical signals from within blood vessels with minimal invasiveness [2]. The choice of acquisition modality directly influences the subsequent design of feature extraction and decoding algorithms.

Mathematical Representation of Neural Signals

Multichannel neural signals are formally represented as a matrix \(\mathscr{X} \in {R}^{C \times T}\), where \(C\) denotes the number of channels (electrodes) and \(T\) represents the temporal dimension [43]. Each element \(x_{c,t}\) corresponds to the electrical potential measured at channel \(c\) at time point \(t\). The observed signal is a composite of neural activity and noise, modeled as:

where \(s_s(t)\) represents the \(s^{th}\) source signal, \(a_{c,s}\) is its mixing coefficient at channel \(c\), and \(η_{c,t}\) represents measurement noise [43]. This formulation underpins the development of advanced signal processing techniques for source separation and noise reduction.

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Architectures for BCIs

Traditional Machine Learning Approaches

Before the rise of deep learning, BCI systems predominantly relied on classical machine learning techniques coupled with hand-crafted features. Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) and its extension, Filter Bank CSP (FBCSP), have been dominant feature extraction methods for motor imagery tasks, designed to maximize the variance between two classes of neural signals [43]. These spatial features were typically classified using algorithms such as Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) and Support Vector Machines (SVM), which achieved accuracies of 65-80% for binary classification problems but often plateaued due to the high-dimensional, non-stationary nature of EEG signals [43].

Deep Learning Architectures

Deep learning has revolutionized neural signal processing by enabling end-to-end learning from raw or minimally processed data, automatically discovering optimal feature representations.