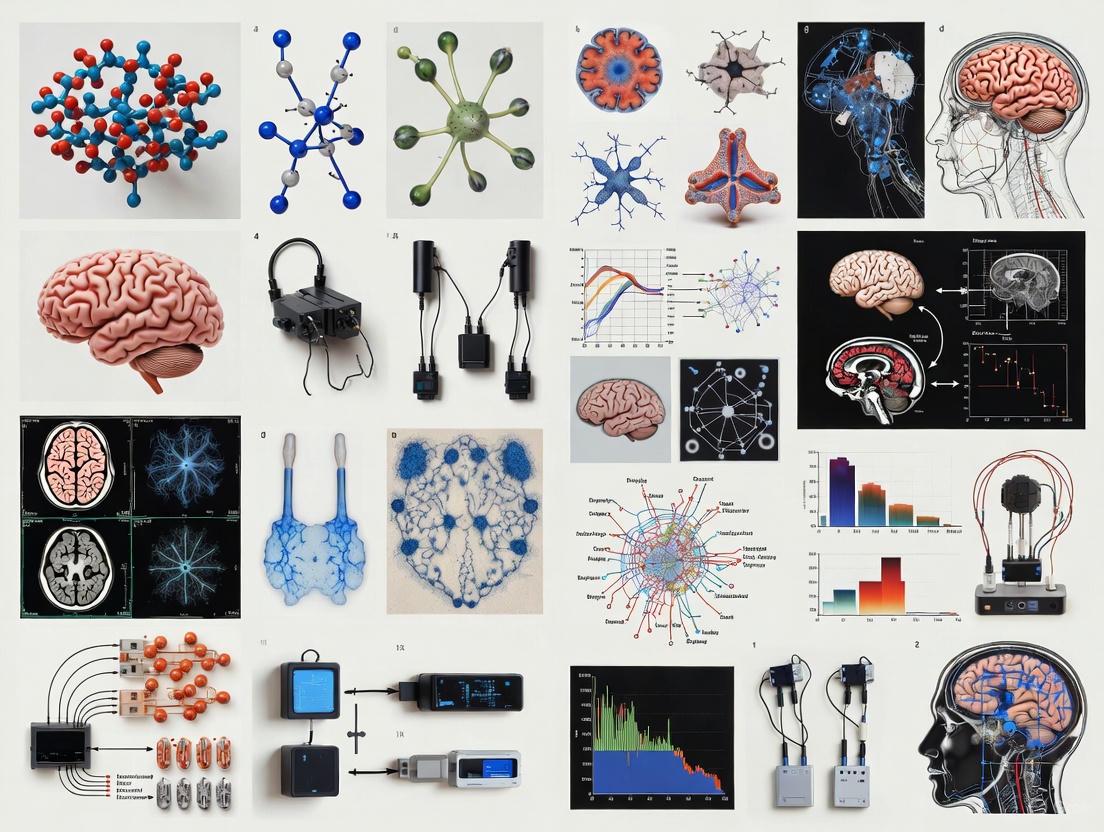

Brain-Computer Interfaces in 2025: A Neuroscience and Clinical Applications Review for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current state and future trajectory of Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) for an audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Brain-Computer Interfaces in 2025: A Neuroscience and Clinical Applications Review for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current state and future trajectory of Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) for an audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of how BCIs translate neural activity into commands, from non-invasive EEG to high-bandwidth implantable systems. The review details the methodological approaches of leading neurotech companies and their specific clinical applications in neurorehabilitation, assistive communication, and prosthetics. It critically examines the technical and optimization challenges, including signal fidelity and biocompatibility, and addresses the pressing neuroethical considerations. Finally, it validates the technology's progress through an overview of ongoing human trials, market growth projections, and the increasing integration of AI, offering a data-driven perspective on the near-term clinical and research landscape.

Decoding the Brain: The Core Principles and Neural Signaling Behind BCIs

Brain-computer interface (BCI) technology represents a transformative advancement in neuroscience research, establishing a direct communication pathway between the brain and external devices. This technical guide provides a comprehensive examination of the core BCI pipeline, which converts neural activity into functional outputs through a structured sequence of processing stages. BCIs operate on the fundamental principle of acquiring brain signals, processing them to decode user intentions, and executing commands that enable users to interact with their environment without relying on peripheral nerves and muscles [1]. As of 2025, these systems have evolved from laboratory demonstrations to clinically viable neurotechnology, with applications ranging from restoring communication for paralyzed individuals to facilitating neurorehabilitation for stroke survivors [2] [3].

The complete BCI pipeline functions as an integrated closed-loop system, continuously adapting to the user's brain activity and providing real-time feedback. This closed-loop design forms the backbone of current BCI research and development, creating a continuous cycle where brain signals are acquired, decoded, executed, and fed back to the user for adjustment [2]. The convergence of deep learning with neural data has dramatically improved the accuracy and speed of these systems, with some speech BCIs now achieving 99% accuracy in decoding words from brain activity with latency under 0.25 seconds [2]. This guide systematically examines each component of this pipeline, providing researchers and drug development professionals with detailed methodological frameworks and technical specifications essential for advancing BCI applications in clinical neuroscience.

Core Components of the BCI Pipeline

Signal Acquisition

Signal acquisition constitutes the foundational stage of the BCI pipeline, responsible for measuring and recording cerebral signals using various sensor modalities. This component bears the critical responsibility of capturing neural activity with sufficient fidelity for subsequent processing and decoding stages [4]. The signal acquisition methodology directly influences the quality of feature extraction and ultimately determines the overall performance ceiling of the BCI system.

Table: Comparison of BCI Signal Acquisition Methods

| Method | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Invasiveness | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEG | Low (~1 cm) | High (ms) | Non-invasive | Motor imagery, SSVEP, P300 paradigms [5] [4] |

| ECoG | Medium (~1 mm) | High (ms) | Semi-invasive (surface implant) | Speech decoding, motor control [2] |

| Intracortical Microarrays | High (~100 μm) | High (ms) | Fully invasive | High-dimensional prosthetic control [2] [6] |

| Endovascular Stentrode | Medium (~1 mm) | Medium | Minimally invasive | Continuous environmental control [2] |

| fMRI | High (~1-2 mm) | Low (seconds) | Non-invasive | Research localization [1] |

Electroencephalography (EEG) remains the most widely used acquisition method in non-invasive BCI systems, measuring electrical signals primarily generated by neuronal postsynaptic potentials through electrodes placed on the scalp [1]. These signals are characteristically weak, typically in the microvolt (μV) range, and suffer from limited spatial resolution due to signal attenuation through the skull and other tissues [4]. Despite these limitations, EEG-based systems dominate research and clinical applications due to their safety, portability, and relatively low cost.

Invasive acquisition methods, including electrocorticography (ECoG) and intracortical microelectrode arrays, offer superior signal quality by recording directly from the cortical surface or within brain tissue. ECoG measures electrical activity using electrodes implanted beneath the skull but on the surface of the brain, capturing signals with higher amplitude and spatial resolution than EEG [1]. Intracortical microarrays, such as Neuralink's chip or Paradromics' Connexus BCI, penetrate the cortical tissue to record action potentials and local field potentials from individual neurons or small neuronal populations [2] [6]. These fully invasive approaches provide the highest signal bandwidth but require neurosurgical implantation and face challenges related to long-term signal stability and tissue response [1].

Innovative approaches continue to emerge in signal acquisition technology. Synchron's Stentrode represents a minimally invasive alternative, deploying an endovascular electrode array through blood vessels to record cortical activity from within the vasculature [2]. Precision Neuroscience has developed an ultra-thin electrode array designed for minimal invasiveness that slips between the skull and brain surface [2]. Each acquisition method presents distinct trade-offs between signal quality, invasiveness, risk profile, and practical implementation constraints that must be carefully considered based on the specific BCI application and target user population.

Signal Processing and Feature Extraction

Once brain signals are acquired, they undergo extensive processing to extract meaningful features that encode the user's intentions. This component involves preprocessing to enhance signal quality, followed by feature extraction to identify discriminative patterns in the neural data. The processing pipeline must address numerous challenges, including low signal-to-noise ratio (particularly in non-invasive methods), artifacts from physiological and environmental sources, and the inherent non-stationarity of brain signals [3].

Table: Common Feature Extraction Methods in BCI Systems

| Feature Type | Description | BCI Paradigms | Key Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-Domain | Amplitude, latency, and morphology of evoked potentials | P300, Movement-Related Cortical Potentials | Peak detection, Template matching [5] |

| Frequency-Domain | Power within specific frequency bands | Motor Imagery, SSVEP | Bandpass filtering, Power spectral density, Wavelet transforms [5] [4] |

| Spatio-Spectral | Combined spatial and frequency information | Motor Imagery, Cognitive State Monitoring | Common Spatial Patterns, Laplacian filtering [5] [7] |

| Time-Frequency | Spectral content evolution over time | Motor Imagery, Asynchronous BCIs | Wavelet transforms, Short-Time Fourier Transform [5] |

| Deep Learning Features | Automated feature learning from raw data | All paradigms, particularly motor imagery | Convolutional Neural Networks, Autoencoders [3] [7] |

For motor imagery BCIs, the most relevant features are typically derived from sensorimotor rhythms (8-30 Hz) that exhibit characteristic changes during movement imagination. The key phenomenon utilized is Event-Related Desynchronization (ERD) - a decrease in power in specific frequency bands during movement preparation and execution - and Event-Related Synchronization (ERS) - a power increase following movement completion [5]. These patterns display contralateral dominance, meaning that imagining right hand movement primarily produces ERD/ERS patterns over the left hemisphere, and vice versa [5] [4].

Contemporary BCI systems increasingly employ machine learning and deep learning approaches for feature extraction and pattern recognition. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can learn spatiotemporal features directly from raw or minimally processed neural signals, potentially bypassing the need for manually engineered features [3] [7]. Transfer learning techniques address the challenge of inter-subject variability by leveraging knowledge from previous users to reduce calibration time for new users [3]. These AI-driven methods have demonstrated remarkable performance, with some studies reporting classification accuracies above 85% for lower-limb motor imagery tasks [7].

Figure 1: BCI Signal Processing and Feature Extraction Workflow

Feature Translation and Device Output

The feature translation stage converts the extracted neural features into commands for external devices, creating a direct mapping between brain activity and real-world outcomes. This component employs classification algorithms that categorize neural patterns into discrete commands or regression approaches that provide continuous control parameters [5]. The translation algorithm must be calibrated to the individual user's neural patterns, typically through an initial training session where users perform specific mental tasks while the system learns the corresponding neural signatures.

For discrete control, such as selecting letters from a virtual keyboard, classification algorithms including Support Vector Machines (SVM), Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), and tree-based methods are commonly employed [5] [3]. These algorithms assign neural patterns to predefined categories corresponding to different commands. For continuous control applications, such as moving a robotic arm or cursor, regression techniques establish a functional relationship between neural features and continuous output parameters [5]. The translation process must operate in real-time with minimal latency to ensure responsive control, particularly for complex tasks like speech synthesis or prosthetic manipulation.

The output commands drive various assistive technologies according to the user's intentions. Common output devices include:

- Communication interfaces: Virtual keyboards for spelling (e.g., P300 speller), speech synthesis systems

- Motor neuroprosthetics: Robotic arms, exoskeletons, functional electrical stimulation systems

- Mobility aids: Brain-controlled wheelchairs, smart home environmental control systems

- Entertainment and computing: Mind-controlled games, web browsers, artistic expression tools

Recent advances in output technology have demonstrated increasingly sophisticated applications. Speech BCIs can now decode imagined speech directly from cortical activity, with systems achieving information transfer rates sufficient for practical communication [2] [6]. For example, Paradromics' BCI system learns the neural patterns corresponding to intended speech sounds and converts them into either text display or synthetic voice output using the participant's own voice recordings [6]. Motor BCIs have enabled paralyzed individuals to control complex robotic arms with multiple degrees of freedom, performing tasks like drinking from a cup or self-feeding [2].

Closed-Loop Feedback

Closed-loop feedback constitutes the final critical component of the BCI pipeline, completing the communication cycle by providing the user with information about the system's interpretation of their neural commands. This feedback enables users to adjust their mental strategies in real-time, forming an adaptive control loop that improves performance through learning and calibration. The feedback mechanism can be delivered through visual, auditory, or tactile modalities, with visual feedback being the most common in current systems [8].

The effectiveness of feedback depends on several factors, including timing, modality, and information content. Immediate feedback allows users to make rapid adjustments to their mental strategies, while delayed feedback can disrupt the learning process [8]. Multimodal feedback systems combine visual, auditory, and tactile cues to enhance the user's awareness of system performance, particularly for users with sensory impairments [9]. The information content must be sufficiently rich to guide learning without overwhelming the user with extraneous cognitive load [8].

Advanced closed-loop systems incorporate adaptive algorithms that continuously update the feature translation parameters based on the user's performance and changing neural patterns. This adaptability is crucial for maintaining BCI performance over time, as neural signals may exhibit non-stationarity due to learning, fatigue, or physiological changes [3]. Modern approaches employ collaborative co-adaptation, where both the user and the system learn and adjust simultaneously, optimizing the interaction for long-term use [8].

Figure 2: Closed-Loop Feedback System in BCI

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol Design for Motor Imagery BCI

Motor imagery (MI) protocols require users to mentally simulate specific movements without executing them physically. Well-designed MI experiments control numerous factors to ensure reliable signal acquisition and interpretation. The standard protocol involves:

Participant Preparation and Setup: Application of EEG cap or other recording equipment with proper impedance checking (<5 kΩ for EEG). For implanted systems, verification of electrode functionality and signal quality [5] [7].

Baseline Recording: Resting-state activity recording for 2-5 minutes with eyes open and closed to establish individual alpha frequency and baseline power spectra [5].

Task Instruction and Training: Clear demonstration of the required motor imagery tasks (e.g., "imagine squeezing your right hand without actually moving it") with practice trials to ensure comprehension [5].

Experimental Trial Structure:

- Fixation cross display (2 seconds)

- Visual cue indicating the specific motor imagery task (1 second)

- Motor imagery period (3-5 seconds) with continuous feedback

- Rest period (randomized 2-4 seconds between trials) [5]

Block Design: Multiple trials (typically 20-40) grouped into blocks with rest periods between blocks to prevent fatigue. A complete session generally comprises 4-8 blocks [5].

The number of trials required depends on the classification approach, with most studies employing 50-200 trials per class for robust classifier training [5]. Counterbalancing of conditions across participants and randomized trial presentation are essential to control for order effects and learning.

P300 Speller Protocol

The P300 speller paradigm relies on the P300 event-related potential, a positive deflection occurring approximately 300ms after the presentation of a rare or significant stimulus. The standard protocol implements the classic matrix speller developed by Farwell and Donchin [4] [1]:

Stimulus Presentation: A 6×6 matrix of characters (letters, numbers, symbols) is displayed. Rows and columns flash in random sequences, with each flash lasting 100ms and an inter-stimulus interval of 75-125ms [4].

Task Instruction: Participants focus attention on a specific character in the matrix and mentally count how many times it flashes [4].

Trial Structure: Each character selection comprises multiple sequences (typically 5-15) where all rows and columns flash once. Increasing sequences improves accuracy at the cost of speed [4].

Signal Processing: EEG signals are filtered (0.1-30Hz), segmented into epochs time-locked to stimulus onset (-100 to 600ms), baselined to pre-stimulus period, and averaged across trials for each channel [4].

Classification: Features (typically time-points in the averaged ERP) are fed to a classifier such as SWLDA or SVM to identify the target row and column [4].

Modern variations include the face speller, which uses images of faces instead of character intensifications, and region-based paradigms that group characters to reduce the number of stimuli [9].

SSVEP BCI Protocol

Steady-State Visual Evoked Potential (SSVEP) protocols use visual stimuli flickering at specific frequencies to elicit brain responses at the same frequency (and harmonics):

Stimulus Design: Multiple visual stimuli (typically 4-8) flicker at different frequencies between 6-40Hz. Frequencies are selected to avoid harmonics overlapping and to maximize response strength [4] [10].

Stimulus Presentation: Stimuli are presented simultaneously on a display, with the participant directed to focus on one target. Each trial lasts 2-5 seconds depending on the desired balance between speed and accuracy [10].

Signal Processing: EEG signals are processed using methods like Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) or Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to identify the frequency component with the highest power [10].

Target Identification: The frequency with the strongest neural response is mapped to the corresponding command [10].

Recent SSVEP implementations have incorporated space-time-coding metasurfaces to enhance security and reliability of the visual stimulation [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Research Reagents and Materials for BCI Experiments

| Category | Item | Specifications | Research Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Acquisition | EEG Electrode Cap | 16-256 channels, Ag/AgCl electrodes | Scalp potential recording for non-invasive BCI [5] [4] |

| Conductive Gel | Electrolyte-chloride based | Improves electrode-skin contact impedance [5] | |

| Utah Array | 96-256 microelectrodes, Silicon substrate | Intracortical recording for high-resolution signals [2] | |

| ECoG Grid | 8x8-16x16 platinum-iridium electrodes | Subdural cortical surface recording [2] | |

| Signal Processing | EEG Amplifier | 24-bit resolution, 0.1-1000 Hz bandwidth | Signal conditioning and digitization [5] |

| Notch Filter | 50/60 Hz rejection | Power line interference removal [5] | |

| Common Average Reference | Software implementation | Global noise reduction in multichannel recordings [5] | |

| Software & Algorithms | CSP Algorithm | MATLAB/Python implementation | Spatial filtering for motor imagery discrimination [5] [7] |

| SVM Classifier | Linear/RBF kernels | Pattern classification for intent recognition [5] [3] | |

| CNN Architecture | 1D/2D convolutional layers | End-to-end learning from raw neural data [3] [7] | |

| Calibration & Testing | BCI2000 | Open-source platform | Protocol presentation and data collection [5] |

| OpenVibe | Open-source platform | Signal processing and machine learning for BCI [5] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

BCI technology continues to evolve beyond basic assistive devices toward increasingly sophisticated applications. In clinical neuroscience, BCIs are being developed for neurorehabilitation, leveraging neuroplasticity to restore function after neurological injury. For example, BCIs can detect movement intention in stroke patients and trigger functional electrical stimulation or robotic assistance, creating Hebbian learning mechanisms that strengthen damaged neural pathways [3]. These systems are transitioning from laboratory demonstrations to clinical validation, with several companies conducting pivotal trials required for regulatory approval [2].

Emerging applications include cognitive state monitoring for Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (AD/ADRD). BCI closed-loop systems integrated with AI can analyze brain signals to identify patterns associated with cognitive decline, potentially enabling earlier and more accurate diagnoses than traditional methods [3]. These systems can provide real-time alerts to caregivers when patients experience significant cognitive challenges, facilitating timely interventions [3].

The security of BCI systems represents another critical research direction. Recent work has explored the vulnerability of wireless BCI systems to eavesdropping and malicious attacks. Advanced encryption methods, including physical-layer security approaches using space-time-coding metasurfaces, are being developed to protect the privacy of neural data [10]. These systems can encrypt information into multiple ciphertexts transmitted through different harmonic frequency channels, preventing unauthorized access to sensitive brain data [10].

Future progress in BCI technology will depend on advances in three crucial areas: development of more convenient and robust signal acquisition hardware, validation through long-term real-world studies with disabled users, and improvement of day-to-day reliability to approach natural muscle-based function [1]. As these challenges are addressed, BCIs have the potential to transform not only assistive technology but also human-computer interaction more broadly, ultimately creating seamless integration between human intelligence and artificial systems.

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) have emerged as transformative tools for neuroscience research and clinical applications, offering unprecedented windows into neural function. The core of any BCI system is its neural recording modality, which dictates the trade-offs between signal resolution, invasiveness, and practical implementation. Electroencephalography (EEG), electrocorticography (ECoG), and microelectrode arrays represent three distinct points on this spectrum, each with characteristic advantages and limitations for specific research and therapeutic contexts.

Understanding these trade-offs is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals selecting appropriate technologies for specific applications. This technical guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these neural interfacing technologies, focusing on their fundamental operating principles, technical specifications, and suitability for various research paradigms within brain-machine interface applications.

Fundamental Operating Principles

Electroencephalography (EEG) represents the least invasive approach, recording electrical activity from electrodes placed on the scalp. These electrodes capture the summed, postsynaptic potentials of billions of cortical neurons after the signals have passed through and been filtered by the skull, cerebrospinal fluid, and other tissues. This biological filtering results in signals with limited spatial resolution but provides a broad overview of global brain dynamics.

Electrocorticography (ECoG) involves electrode grids or strips placed directly on the exposed cortical surface, typically during neurosurgical procedures. By bypassing the skull, ECoG captures local field potentials (LFPs) with higher fidelity and spatial resolution than EEG. These signals represent the coordinated activity of neuronal populations across cortical layers within a few millimeters of the electrode [11]. Recent advances have led to micro-electrocorticography (µECoG) featuring higher-density electrode arrays with smaller contacts and tighter spacing, significantly improving spatial resolution [12] [13].

Microelectrode Arrays represent the most invasive and highest-resolution option. These devices feature micro-scale electrodes that penetrate into brain tissue, typically 1-2 mm deep, enabling recording of both local field potentials and action potentials (spikes) from individual neurons or small neuronal ensembles [11]. Unlike ECoG's population-level signals, intracortical electrodes capture the precise timing of individual neuronal firing, providing unparalleled temporal and spatial resolution for decoding neural computations.

Quantitative Technical Comparison

The table below summarizes key technical parameters across the three neural recording modalities:

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Neural Recording Modalities

| Parameter | EEG | ECoG | Microelectrode Arrays |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | ~1-10 cm | ~1-10 mm | ~50-500 µm |

| Temporal Resolution | ~10-100 ms | ~1-10 ms | <1 ms |

| Signal Types Captured | Summed cortical potentials | Local field potentials (LFPs) | Single-unit & multi-unit activity, LFPs |

| Typical Electrode Count | 32-256 channels | 64-256 channels (clinical)Up to 1,024+ (research µECoG) | 96-1,024+ channels |

| Invasiveness Level | Non-invasive | Minimally invasive (surface recording) | Highly invasive (tissue-penetrating) |

| Surgical Procedure | None | Craniotomy or cranial "micro-slit" [12] [14] | Craniotomy with penetrating insertion |

| Information Transfer Rate | Low | Medium | High (≥10× ECoG) [11] |

| Decoding Latency | High (multi-second) | Medium (multi-second) | Low (~100-200 ms) [11] |

| Chronic Stability | High | Medium-high | Medium (signal degradation possible) |

Performance Metrics for Brain-Machine Interfaces

The fundamental differences in signal acquisition directly impact BCI performance metrics, particularly for communication and motor control applications:

Table 2: BCI Performance Comparison for Communication Applications

| Performance Metric | ECoG-based Speech BCI | Microelectrode-based Speech BCI |

|---|---|---|

| Vocabulary Size | ~50-1,000 words | Up to 125,000+ words [11] |

| Words Per Minute | ~78 WPM | ~62 WPM [11] |

| Word Error Rate | ~25% | ~2.5-23.8% [11] |

| Decoding Latency | Multi-second delays | ~100s of milliseconds [11] |

| Training Time | Extended training often required | Reduced training time demonstrated [11] |

For motor applications, ECoG has demonstrated capabilities for decoding basic hand gestures with accuracies ranging from 70% to 97%, though typically limited to distinguishing between 2-4 gesture types [11]. In contrast, intracortical microelectrodes have enabled more complex, continuous control of prosthetic limbs with higher degrees of freedom and precision approaching natural movement.

Experimental Methodologies

Implementation Protocols

EEG Experimental Setup: Standard experimental protocols involve applying conductive gel or using saline-based electrodes positioned according to the international 10-20 system. Impedance should be maintained below 5-10 kΩ to ensure signal quality. Data acquisition typically occurs at sampling rates of 250-2000 Hz with appropriate bandpass filtering (e.g., 0.1-100 Hz) to capture relevant neural oscillations while removing drift and high-frequency noise.

ECoG/µECoG Array Implantation: Recent minimally invasive approaches utilize "cranial micro-slit" techniques involving 500-900μm wide incisions in the skull for subdural insertion of thin-film arrays [12]. Surgical planning employs fluoroscopic or computed tomographic guidance with neuroendoscopic monitoring. This procedure enables implantation of high-density arrays (e.g., 1,024 electrodes) in under 20 minutes with minimal tissue damage [12]. Electrode-tissue interface optimization is critical, with impedance characteristics tailored to electrode size (e.g., 802 kΩ for 20μm electrodes vs. 8.25 kΩ for 380μm electrodes) [12].

Microelectrode Array Implantation: Penetrating arrays require full craniotomy and careful insertion to target depth (typically cortical layers IV-V). Systems like the Utah array are inserted using pneumatic insertion devices, while newer technologies like Neuralink's N1 implant require robotic assistance for inserting thousands of flexible threads [14] [15]. Chronic implantation necessitates careful consideration of meningeal closure and connector fixation to prevent infection and maintain stability.

Signal Processing Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the typical signal processing pipeline for neural data across recording modalities:

Neural Signal Processing Pipeline

Decoding Approaches for Motor and Speech Applications

Motor Decoding: For EEG, sensorimotor rhythms (mu/beta rhythms) during motor imagery provide the control signals for BCIs, typically decoded using common spatial patterns or Riemannian geometry. ECoG-based motor decoding often focuses on high-gamma (70-150 Hz) power modulations in sensorimotor cortex, which provide robust movement-related signals [16]. Microelectrode arrays enable decoding based on individual neuron tuning properties (direction, velocity, force) and population vector algorithms that reconstruct continuous movement parameters with high fidelity.

Speech Decoding: ECoG-based speech BCIs typically utilize articulatory representations from sensorimotor cortex or auditory representations from superior temporal gyrus, employing deep learning models to map neural features to phonemes or words [11]. Microelectrode arrays have demonstrated superior performance for speech decoding, with recent studies achieving 97.5% accuracy with 125,000-word vocabulary by predicting phonemes every 80 milliseconds from intracortical signals in speech-related areas [11].

The Researcher's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Neural Interface Research

| Material/Component | Function/Purpose | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density Microelectrode Arrays | Neural signal acquisition | 1,024-channel thin-film µECoG arrays [12]; 256-channel Utah arrays [14] |

| Flexible Substrate Materials | Conformable neural interfaces | Polyimide, parylene-C substrates for cortical surface contact [12] [13] |

| Integrated Electronics | Signal conditioning & processing | CMOS-based amplifiers, filters, analog-to-digital converters [16] [17] |

| Digital Holographic Imaging | Non-invasive neural activity recording | Nanometer-scale tissue deformation measurement through scalp [18] |

| Biocompatible Encapsulation | Chronic implantation stability | Silicon carbide, Parylene C, medical-grade silicones [12] |

| Low-Power Processors | On-chip signal processing | Application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) for feature extraction [16] |

Technology Selection Framework

The relationship between signal resolution, invasiveness, and application suitability follows a predictable pattern, illustrated in the following decision framework:

Neural Interface Technology Selection Framework

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of neural interfacing is rapidly evolving, with several promising developments shaping future research directions. Minimally invasive surgical approaches are reducing the barrier to high-resolution neural recording, with cranial "micro-slit" techniques enabling implantation of 1,024-electrode µECoG arrays without traditional craniotomy [12] [14]. These approaches maintain the safety profile of surface recording while approaching the resolution previously available only with penetrating electrodes.

High-density microelectrode arrays represent another frontier, with recent devices featuring up to 236,880 electrodes on a single chip enabling simultaneous readout of 33,840 channels at 70 kHz [17]. This massive scaling enables unprecedented mapping of neural networks across multiple spatial scales, from subcellular compartments to entire functional networks.

Novel non-invasive technologies are also emerging, with digital holographic imaging systems demonstrating the ability to detect nanometer-scale tissue deformations associated with neural activity through the intact scalp [18]. While still in early development, this approach could potentially provide non-invasive alternatives for high-resolution neural recording in the future.

Low-power circuit design has become increasingly critical as channel counts escalate. Research focuses on optimizing the trade-off between classification rate and input data rate, with findings suggesting that increasing channel count can simultaneously reduce power consumption per channel through hardware sharing while increasing information transfer rate [16].

These technological advances are driving the field toward solutions that balance high performance with practical implementation, potentially enabling broader adoption in both clinical and research settings. As these technologies mature, researchers and drug development professionals will have an expanding toolkit for investigating neural function and developing novel therapeutic interventions.

Key Neural Signals and What They Represent for Device Control

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) translate specific neural signals into commands for external devices, creating direct communication pathways between the brain and computers. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the key neural signals—including action potentials, local field potentials (LFPs), and motor imagery-related electroencephalography (EEG) patterns—and their roles in device control. Framed within the broader context of brain-machine interface (BMI) applications for neuroscience research, this guide details the signal characteristics, decoding methodologies, and experimental protocols essential for developing next-generation neurotechnology. The content is structured to assist researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in understanding the technical foundations and practical implementations of neural signal processing for therapeutic and assistive technologies.

Brain-computer interfaces establish a direct communication channel between the human brain and external devices, bypassing conventional neuromuscular pathways [19]. The core functionality of any BCI system relies on its capacity to accurately acquire and decode specific neural signals generated by the user's central nervous system. These signals can be broadly categorized into two types: those generated from invasive recording methods, such as intra-cortical microelectrode arrays that capture single-unit activity and local field potentials, and those obtained through non-invasive techniques like electroencephalography (EEG) that measure aggregated cortical activity [20] [21]. The information encoded within these signals ranges from motor commands and cognitive states to responses to external stimuli, which can be translated into control signals for devices ranging from computer cursors to advanced prosthetic limbs.

The representation of user intent through neural signals is fundamentally linked to the concept of neural coding, which refers to how information is represented and transmitted by patterns of neural activity [19]. In practical BCI applications, this involves mapping specific neural signal features—such as the firing rate of a neuron, the power in a particular frequency band of the LFP, or the amplitude of an event-related potential in the EEG—to distinct commands for device control. The development of effective BCI systems therefore requires a multidisciplinary approach integrating neuroscience, signal processing, machine learning, and engineering to accurately interpret the neural code and translate it into reliable control signals with minimal latency.

Key Neural Signals for Device Control

Action Potentials (Spikes)

Action potentials, or "spikes," are all-or-none electrochemical impulses generated by individual neurons when rapidly changing membrane potentials exceed a specific threshold [20]. These signals represent the fundamental unit of neural communication in the central nervous system, with information encoded through firing rates and temporal patterns of individual neurons or neuronal populations.

Signal Characteristics: Extracellularly recorded action potentials typically manifest as amplitude fluctuations ranging from 50 to 500 μV that occur over a time course of 1-2 milliseconds [20]. They are characterized by their specific waveform shape, which can vary across different neuronal types.

Information Representation: In motor BCIs, the firing rates of neurons in the primary motor cortex (M1) often correlate with movement parameters such as direction, velocity, and force [20]. For device control, the intended movement trajectory is decoded from the collective activity patterns of neuronal populations.

Acquisition Methodology: Recording action potentials requires high-impedance microelectrodes implanted directly into cortical tissue, typically providing the highest spatial and temporal resolution for neural decoding [20]. These signals are usually bandpass filtered between 300 Hz and 6-10 kHz to isolate them from lower-frequency components and sampled at rates up to 20-30 kSamples/sec [20].

Local Field Potentials (LFPs)

Local field potentials represent the low-frequency component (typically <300 Hz) of neural signals, reflecting the synchronous synaptic activity of local neuronal populations rather than individual action potentials [20]. LFPs are considered to be the integrated input signals of a brain region and are believed to represent the average of neuronal activities occurring both nearby and farther away from the recording electrode.

Signal Characteristics: LFPs are continuous voltage signals dominated by frequency-specific oscillations that have been linked to various brain states and functions. These oscillations are categorized into different frequency bands, each associated with distinct cognitive or motor processes relevant to device control.

Information Representation: Specific frequency bands within the LFP carry distinct information. For instance, beta band oscillations (13-30 Hz) in sensorimotor cortex are modulated during motor preparation and execution, while gamma band oscillations (30-200 Hz) have been correlated with various cognitive and motor processes [20]. The table below summarizes the key LFP frequency bands and their functional correlates for device control.

Table 1: Local Field Potential Frequency Bands and Their Functional Correlates

| Frequency Band | Range | Functional Correlates for Device Control |

|---|---|---|

| Delta | 0.5-4 Hz | Deep sleep, pathological states |

| Theta | 4-8 Hz | Working memory, navigation |

| Alpha | 8-13 Hz | Relaxed wakefulness, idling state |

| Beta | 13-30 Hz | Motor planning, sustained muscle contraction |

| Gamma | 30-200 Hz | Feature binding, attention, motor processing |

- Acquisition Methodology: LFPs are recorded using the same implanted microelectrodes as action potentials but are processed with different filters (typically 0.5-300 Hz) and lower sampling rates [20]. This signal component is often more stable over long-term recordings compared to action potentials.

Motor Imagery EEG Signals

Motor imagery (MI) signals recorded through non-invasive electroencephalography (EEG) represent the cortical activation patterns associated with the mental simulation of movement without physical execution [22]. These signals form the basis for many non-invasive BCIs aimed at restoring communication and control for individuals with motor impairments.

Signal Characteristics: MI is characterized by contralateral desynchronization of mu rhythms (8-12 Hz) and beta rhythms (13-30 Hz) over sensorimotor areas during imagination of limb movements [22]. This phenomenon, known as event-related desynchronization (ERD), is followed by synchronization (ERS) after movement termination.

Information Representation: The spatial pattern and timing of ERD/ERS across electrode locations provide discriminative features for classifying different types of motor imagery (e.g., left hand vs. right hand vs. foot movements), which can be mapped to discrete control commands for external devices [22].

Acquisition Methodology: EEG signals are typically recorded from 16 to 256 electrodes placed on the scalp according to the international 10-20 system, sampled at rates of 128-1000 Hz, and referenced to a common average or specific reference site [22].

Quantitative Data on Neural Signal Classification

The accurate classification of neural signals is paramount for effective device control. Recent advances in machine learning and deep learning have significantly improved decoding accuracies. The table below summarizes performance metrics for various classification approaches applied to motor imagery EEG data, based on a 2025 study using the PhysioNet EEG Motor Movement/Imagery Dataset [22].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Classification Algorithms for Motor Imagery EEG Signals

| Classification Algorithm | Accuracy | Key Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | 91.00% | Robust to outliers, handles nonlinear relationships | Limited temporal modeling |

| Support Vector Classifier (SVC) | 84.72% | Effective in high-dimensional spaces | Sensitive to kernel choice and parameters |

| k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) | 83.33% | Simple implementation, no training phase | Computationally intensive with large datasets |

| Logistic Regression (LR) | 79.17% | Probabilistic output, fast training | Assumes linear separability |

| Naive Bayes (NB) | 75.00% | Computational efficiency, works with small datasets | Strong feature independence assumption |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | 88.18% | Automatic spatial feature extraction | Requires large datasets, computationally intensive |

| Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) | 16.13% | Models temporal dependencies | Low accuracy with raw EEG, requires careful tuning |

| Hybrid CNN-LSTM | 96.06% | Captures both spatial and temporal features | Complex architecture, extensive computation needed |

The substantial performance improvement demonstrated by the hybrid CNN-LSTM model highlights the importance of leveraging both spatial and temporal characteristics of neural signals for accurate decoding in BCI systems [22]. This approach achieved a remarkable 96.06% accuracy in classifying motor imagery tasks, significantly outperforming traditional machine learning models and individual deep learning approaches [22].

Experimental Protocols for Neural Signal Acquisition

Intracortical Signal Recording for Invasive BCIs

Objective: To acquire high-quality action potentials and local field potentials from the cerebral cortex for precise device control.

Materials and Equipment:

- High-density microelectrode array (e.g., Utah array, Neuropixels probe)

- Low-noise preamplifiers and signal conditioning circuits

- Analog-to-digital converter with at least 16-bit resolution

- Wireless telemetry system or percutaneous connector

- Reference and ground electrodes

- Neural signal processing unit

Methodology:

- Surgical Implantation: Sterotactically implant the microelectrode array into the target brain region (e.g., primary motor cortex for motor BCIs) under general anesthesia using aseptic techniques.

- Signal Acquisition: Configure acquisition parameters with bandpass filtering: 0.5-300 Hz for LFP and 300-6000 Hz for action potentials, sampling at 20-30 kSamples/sec [20].

- Signal Preprocessing:

- For spike detection: Apply a high-pass filter (300 Hz cutoff) followed by amplitude thresholding to identify action potentials.

- For LFP analysis: Apply a low-pass filter (300 Hz cutoff) and downsample to approximately 1 kSample/sec.

- Feature Extraction:

- For spikes: Extract spike counts per time bin, wavelet features, or principal components.

- For LFP: Compute power spectral density in specific frequency bands using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) or wavelet transforms.

- Real-time Processing: Implement decoding algorithms with minimal latency (<100 ms) for closed-loop device control.

Quality Control: Regularly assess signal-to-noise ratio, electrode impedance, and unit isolation quality. Exclude channels with excessive noise or unstable recordings.

Figure 1: Intracortical Signal Recording and Processing Workflow

Motor Imagery EEG Recording Protocol

Objective: To acquire and classify EEG signals associated with motor imagery for non-invasive BCI control.

Materials and Equipment:

- EEG cap with 16-64 electrodes positioned according to the 10-20 system

- High-input impedance amplifiers with common-mode rejection ratio >100 dB

- Analog bandpass filters (0.5-100 Hz)

- ADC with at least 16-bit resolution, sampling at 250-1000 Hz

- Visual cue presentation system

- Electrically shielded room

Methodology:

- Experimental Setup: Apply conductive electrode gel to achieve electrode-skin impedance below 5 kΩ. Position ground electrode at AFz and reference at linked mastoids or Cz.

- Paradigm Design: Implement a cue-based trial structure:

- Fixation cross (2 s)

- Visual cue indicating imagined movement type (e.g., left hand, right hand, feet) (3-4 s)

- Rest period (randomized 2-3 s)

- Data Acquisition: Record continuous EEG during the experiment with proper labeling of trial types and timing markers.

- Preprocessing:

- Apply bandpass filter (0.5-45 Hz) to remove DC drift and high-frequency noise

- Remove ocular and muscle artifacts using Independent Component Analysis (ICA)

- Re-reference to common average reference

- Feature Extraction:

- Extract trial epochs from -1 to 4 s relative to cue onset

- Compute log-variance of filtered signals in mu (8-12 Hz) and beta (13-30 Hz) bands

- Apply spatial filters (e.g., Common Spatial Patterns) to enhance discriminability

- Classification: Train and validate classifiers (e.g., Random Forest, SVM, or CNN-LSTM) using cross-validation.

Quality Control: Monitor data quality in real-time for artifacts. Reject trials with amplitude exceeding ±100 μV or with abnormal spectra.

Figure 2: Motor Imagery EEG Experimental Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key research reagents, components, and equipment essential for BCI research and development, particularly focused on neural signal acquisition and processing for device control applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Neural Signal-Based Device Control

| Category | Item | Specification/Example | Function in BCI Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recording Electrodes | Intracortical Microelectrode Arrays | Utah array, Neuropixels probes | High-density neural recording from cortical tissue with high spatial resolution |

| Electroencephalography (EEG) Electrodes | Ag/AgCl sintered electrodes, active electrodes | Non-invasive recording of brain potentials from scalp surface | |

| Electrocorticography (ECoG) Grids | Platinum-iridium electrodes on flexible substrate | Subdural recording with higher spatial resolution than EEG | |

| Signal Acquisition Hardware | Neural Amplifiers | Intan Technologies RHD series, Blackrock systems | Low-noise amplification and conditioning of weak neural signals |

| Analog-to-Digital Converters | 16-24 bit resolution, >20 kS/s sampling rate | Conversion of analog neural signals to digital format for processing | |

| Wireless Telemetry Systems | Custom RF or infrared transmitters | Wireless data transmission from implanted devices to external receivers | |

| Signal Processing Tools | Digital Signal Processors | Texas Instruments TMS320 series, FPGA implementations | Real-time processing of neural signals for feature extraction |

| Machine Learning Libraries | Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Implementation of classification and decoding algorithms | |

| Spectral Analysis Tools | Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), Wavelet Transform | Frequency domain analysis of neural oscillations | |

| Experimental Paradigms | Motor Imagery Tasks | Left/right hand, foot, tongue imagery | Elicitation of discriminable brain patterns for device control |

| Visual Evoked Potential Stimuli | SSVEP, P300 speller paradigms | Elicitation of time-locked neural responses for BCI control | |

| Validation & Testing | Phantom Brains | Conductive gel-filled models with electrode placements | Testing and validation of recording systems without human subjects |

| Bench Testing Equipment | Signal generators, oscilloscopes, impedance testers | Verification of system performance and signal quality |

The precise decoding of neural signals for device control represents a frontier in neuroscience research with transformative potential for therapeutic applications. Action potentials provide the highest resolution information for detailed movement control but require invasive recording approaches. Local field potentials offer more stable signals over long durations and capture population-level activity patterns relevant to brain states. Motor imagery EEG signals enable completely non-invasive BCI systems, though with more limited information transfer rates. The continuing advancement of neural decoding algorithms, particularly hybrid deep learning approaches that achieve over 96% classification accuracy, promises to significantly enhance the performance and reliability of next-generation BCI systems. As these technologies mature, they will increasingly enable individuals with neurological disorders to interact with their environment through direct neural control, ultimately improving quality of life and functional independence.

The Role of AI and Deep Learning in Advanced Signal Decoding

Advanced signal decoding represents a transformative frontier in neuroscience, particularly for brain-machine interface (BMI) applications. The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI), and specifically deep learning, is overcoming long-standing barriers in interpreting the brain's complex neural signals. This paradigm shift moves beyond simple signal classification to the reconstruction of intricate cognitive processes, from imagined speech to motor intentions. By leveraging AI's pattern recognition capabilities, researchers can now decode semantic information, predict motor disturbances, and model neuronal biophysics with unprecedented accuracy. This technical guide examines the core methodologies, experimental protocols, and quantitative performance benchmarks that define the current state of AI-driven neural decoding, providing researchers with the foundational knowledge to advance this rapidly evolving field.

Core Applications in Neuroscience and Neurotechnology

The application of AI to neural decoding spans multiple domains of brain function, each with distinct computational challenges and clinical implications. The table below summarizes three prominent applications.

Table 1: Key Applications of AI in Neural Signal Decoding

| Application Domain | AI Model Type | Key Function | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Semantic Decoding for Communication [23] | Machine Learning Classifier | Decodes word categories from intracranial brain activity. | Up to 77% accuracy for 15 categories; 97% accuracy for living/non-living distinction [23]. |

| Motor Symptom Prediction in Parkinson's [23] | Deep Learning Model | Predicts freezing of gait (FoG) episodes from neural signatures. | Enabled prediction of FoG before clinical onset, allowing for potential preemptive DBS intervention [23]. |

| Neuronal Biophysical Modeling [23] | Deep Learning System (NeuroInverter) | Infers ion channel composition from a neuron's electrical signals. | Successfully predicted ion channels for 170 different neuron types, including those not seen in training [23]. |

These applications demonstrate a common trend: the movement from reactive to predictive and generative models. Rather than merely classifying observed brain states, modern AI decoders infer intended actions, simulate internal representations, and forecast future neurological events. This is crucial for developing next-generation BCIs that are proactive and truly restorative [24].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Decoding Semantic Content from Intracranial Recordings

The high-accuracy decoding of semantic content, as demonstrated in recent studies, relies on a precise experimental and analytical protocol [23].

- Subject Population & Recording: The protocol uses rare intracranial recordings from epilepsy patients undergoing presurgical monitoring. Electrodes are placed directly on the cortical surface or within brain tissue to achieve a high signal-to-noise ratio.

- Stimulus Presentation: Participants are presented with words from a set of pre-defined semantic categories (e.g., tools, animals). The task involves actively thinking about the presented word.

- Data Acquisition & Preprocessing: Neural activity is recorded while the patient engages with the stimulus. The data is cleaned, and features are extracted, often focusing on frequency bands or spatial patterns of activity known to be involved in semantic processing.

- Model Training & Testing: A machine learning classifier (e.g., a support vector machine or a neural network) is trained on a subset of the neural data to associate specific brain activity patterns with their corresponding word categories. The model's performance is then validated on a held-out test set, not used during training.

This methodology's success, achieving up to 77% accuracy, hinges on the quality of invasive recordings and the model's ability to learn distributed semantic representations [23].

Non-Invasive Sentence Decoding via Motor Imagery

For non-invasive applications, a key protocol involves decoding language production via the associated motor plans. The Brain2Qwerty architecture is a prime example [25].

- Task Design: Participants are asked to memorize and then type sentences on a QWERTY keyboard while their brain activity is recorded via magnetoencephalography (MEG) or electroencephalography (EEG).

- Signal Alignment: The recorded brain signals are precisely aligned in time with the keystrokes. This creates a labeled dataset where neural data is mapped to specific motor outputs.

- Model Architecture (Brain2Qwerty): A deep learning model, such as a convolutional or recurrent neural network, is designed to take the temporal neural data as input. The model learns the complex mapping between the brain's motor and cognitive activity during typing and the corresponding characters.

- Output & Evaluation: The model's output is a sequence of characters. Performance is rigorously evaluated using the Character Error Rate (CER), which measures the edit distance between the decoded sentence and the ground truth. This protocol has achieved a CER as low as 19% for the best participants using MEG [25].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Invasive vs. Non-Invasive Linguistic Decoding

| Methodology | Decoding Target | Key Metric | Reported Performance | Primary Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive (ECoG) [23] | Word Category | Accuracy | 77% (15 categories) | Requires intracranial surgery. |

| Non-Invasive (MEG) [25] | Typed Sentences | Character Error Rate (CER) | 19% (best participant) | Lower signal-to-noise ratio. |

| Non-Invasive (EEG) [25] | Typed Sentences | Character Error Rate (CER) | 67% (average) | Signal attenuation by the skull. |

AI-Driven Gait Analysis from Video

Beyond neural signals, AI can decode motor function from simple videos, offering a highly accessible diagnostic tool [23].

- Data Collection: Smartphone videos are recorded of individuals performing walking tasks. This creates a large dataset of both normal and impaired gait patterns.

- Computer Vision Processing: AI algorithms based on computer vision extract body keypoints and kinematic parameters (e.g., step length, joint angles) from the video frames without the need for wearable sensors.

- Model Validation: The output of the AI model is compared against the gold-standard assessments of expert rehabilitation clinicians and 3D motion capture systems. The model is refined until its outputs show a high correlation with clinical judgement.

- Clinical Integration: The final system provides an automated, objective, and interpretable assessment of gait impairments, making it a potential tool for telemedicine and routine clinical monitoring.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The process of AI-driven neural decoding can be conceptualized as a multi-stage pipeline, from data acquisition to the final decoded output. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for decoding linguistic and motor information.

AI Neural Decoding Pipeline

A critical conceptual framework in this field is the alignment between artificial and biological neural networks, which enables effective decoding. The brain's predictive processing during language comprehension creates a temporal structure that AI models can learn to map.

Brain-AI Representation Alignment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Translating AI decoding models from concept to practice requires a suite of specialized tools and computational resources. The following table details key components of the modern neuro-AI research pipeline.

Table 3: Essential Resources for AI-Driven Neural Decoding Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tool / Technique | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Acquisition | Electrocorticography (ECoG) | Provides high-fidelity intracranial recordings for training accurate decoders, often in clinical populations [23]. |

| Data Acquisition | Magnetoencephalography (MEG) | Offers non-invasive, high-temporal-resolution brain data suitable for decoding rapid processes like typing imagery [25]. |

| Computational Framework | Deep Learning Architectures (e.g., Brain2Qwerty) | Custom neural network models designed to map temporal brain signals to structured outputs like text [25]. |

| Computational Framework | Pre-trained Large Language Models (LLMs) | Provides powerful semantic representations that can be aligned with brain activity to improve decoding of meaning [26]. |

| Model Training & Validation | Character Error Rate (CER) / Word Error Rate (WER) | Standardized metrics for quantitatively evaluating the performance of sequential text decoding models [26] [25]. |

| Biophysical Simulation | Blue Brain Project Cell Library | Provides millions of computer-simulated "brain cells" for training models like NeuroInverter to infer ion channel properties [23]. |

From Lab to Clinic: Methodologies of Leading Neurotech and Their Transformative Applications

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) represent a transformative frontier in neuroscience and neurotechnology, aiming to restore function for patients with severe neurological impairments. This whitepaper provides a technical analysis of four leading companies—Neuralink, Synchron, Paradromics, and Precision Neuroscience—each pursuing distinct technological pathways in implantable BCI design. These approaches involve fundamental trade-offs between signal fidelity, invasiveness, and long-term safety. The field is advancing rapidly from academic research toward clinical application, with recent regulatory milestones enabling first-in-human trials focused on motor restoration and communication. The evolution of these platforms is poised to create new paradigms for understanding brain function and developing therapeutic interventions.

Company Profiles and Technical Specifications

The competitive landscape for implantable BCIs is defined by differing solutions to the core challenge of safely accessing high-quality neural signals.

Table 1: Company Profiles and Technological Approaches

| Company | Core Technology | Implantation Method | Key Differentiators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuralink | N1 Implant with 1024-electrode flexible polymer threads [27] | Craniotomy; specialized robotic insertion (R1 robot) [28] | High channel count; focus on consumer usability and surgical automation [27] [28] |

| Synchron | Stentrode endovascular electrode array [29] [6] | Minimally invasive; delivered via blood vessels [29] [6] | Avoids open brain surgery; "butcher ratio" of zero (no neurons killed during implantation) [29] |

| Paradromics | Connexus BCI using platinum-iridium microwires [30] [28] | Craniotomy; EpiPen-like rapid inserter [28] | Materials for long-term biocompatibility; >200 bps data rate in pre-clinical models [31] [28] |

| Precision Neuroscience | Layer 7 Cortical Interface (surface electrode array) [32] [33] | Minimally invasive "microslit" craniotomy [33] | Surface placement avoids penetrating brain tissue; designed to be safe and removable [32] [33] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance and Clinical Status (as of 2025)

| Company | Reported Information Transfer Rate | Electrode Count / Scale | Clinical Trial Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuralink | 4-10 bps (in human participant) [27] [28] | 1024 electrodes [27] | Early Feasibility Study (N=3+ patients) [27] |

| Synchron | <1-2 bps (estimated from benchmarks) [31] | 12-16 electrodes [6] | Early Feasibility Study; first to start US trials for permanent BCI [34] [6] |

| Paradromics | >200 bps (in pre-clinical models) [31] [28] | ~1600 channels planned [34] | FDA IDE approved for Connect-One Early Feasibility Study (2025) [30] [6] |

| Precision Neuroscience | Not publicly benchmarked | High-density surface array [33] | FDA 510(k) clearance for Layer 7 (2025); clinical partnerships initiated [32] [33] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Paradromics' SONIC Benchmarking Protocol

The Standard for Optimizing Neural Interface Capacity (SONIC) is an application-agnostic engineering benchmark designed to measure the fundamental information-carrying capacity of a BCI system [31].

Methodology:

- Animal Model: Preclinical experiments conducted in sheep [31].

- Stimulus Presentation: Controlled sequences of sounds (five-note musical tone sequences) are presented to the animal. Each unique sequence is mapped to a character, creating a "dictionary" for transmission [31].

- Neural Recording: The fully implanted Connexus BCI records neural activity from the auditory cortex while the stimuli are presented [31].

- Signal Decoding: Recorded neural signals are processed to predict which specific sounds were presented.

- Information Calculation: The mutual information between the presented sound sequences and the decoded predictions is computed. This provides a rigorous, task-agnostic measure of the information transfer rate in bits per second (bps), while also accounting for system latency [31].

Neuralink's Motor Control Decoding Protocol

Neuralink's initial human trials focus on restoring computer control for individuals with paralysis [27].

Methodology:

- Patient Implantation: The N1 device is implanted in the region of the motor cortex responsible for hand movement [6].

- Calibration/Training: Participants are asked to imagine performing specific hand movements (e.g., moving a cursor on a screen) while the system records associated neural patterns. This calibrates the "decoder"—a software model that maps neural activity to intended cursor movements [27].

- Real-time Control: The participant uses their imagined movements to control a computer mouse, navigate interfaces, and play games [27].

- Performance Metric: Control performance is evaluated using tasks like the "Webgrid" test, which calculates the achieved information transfer rate in bits per second [27].

- Model Retraining: The decoder model requires periodic recalibration (retraining) to maintain performance, a process that participants initially reported could take up to 45 minutes [27].

Synchron's Endovascular BCI Protocol for Device Implantation

Synchron's Stentrode is implanted without a craniotomy, using established endovascular techniques [29] [6].

Methodology:

- Access: The device is inserted into a blood vessel, typically via the jugular vein in the neck [29].

- Navigation: Using catheter-based delivery, the stent-electrode array is navigated through the venous system and deployed in a blood vessel adjacent to the primary motor cortex [29] [6].

- Integration: The stent expands to anchor against the vessel wall, and the device becomes incorporated into the vessel through natural vascular remodeling over time [35].

- Signal Recording: The embedded electrodes record aggregate neural signals (local field potentials) from the surrounding brain tissue through the blood vessel wall [6]. These signals are used to control assistive technologies, such as cursor selection via imagined motor actions like foot movement [6].

Signaling Pathways and System Workflows

The core workflow for an implanted BCI involves a multi-stage process from signal acquisition to device control. The following diagram generalizes this pipeline, with variations depending on the specific company's technology.

Figure 1: Generalized BCI System Workflow. This diagram illustrates the standard signal processing pipeline from neural activity to device control, common across invasive BCI platforms.

The fundamental biological process that enables BCI functionality is the generation and propagation of action potentials by neurons.

Figure 2: Basis of BCI Signal Generation. Neural communication relies on electrochemical signals. A cognitive intent triggers ion flow across a neuron's membrane, generating a rapid electrical pulse called an action potential. This pulse creates a tiny, detectable extracellular electrical field that BCI electrodes are designed to record [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and testing of BCIs rely on a suite of specialized materials and biological tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials in BCI Development

| Item / Reagent | Function in BCI R&D | Specific Examples from Company Tech |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatible Electrode Materials | Ensure long-term stability and minimize immune response in brain tissue. | Paradromics: Platinum-Iridium microwires [28]. Neuralink: Flexible polymer threads [28]. |

| Hermetic Encapsulation | Protects electronic components from the corrosive saline environment of the body. | Paradromics: Titanium alloy body [28]. |

| Surgical Insertion Tools | Enable precise, safe, and repeatable placement of the neural interface. | Neuralink: R1 surgical robot [28]. Paradromics: EpiPen-like mechanical inserter [28]. |

| Pre-clinical Animal Models | Provide a biological system for testing safety, longevity, and performance preclinically. | Paradromics: Sheep model for chronic recording [31] [6]. Synchron: Sheep model for vascular remodeling [35]. |

| Signal Processing Algorithms | Decode raw neural data into intended commands; includes filtering, spike sorting, and classification. | Machine learning models for translating neural activity into cursor movement [27] or text/speech [6]. |

| Benchmarking Paradigms | Provide standardized, application-agnostic tests to quantify system performance. | Paradromics' SONIC benchmark using auditory stimuli [31]. Neuralink's Webgrid test for cursor control [27]. |

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) represent a transformative frontier in neuroscience research, aiming to restore communication for individuals with severe paralysis resulting from conditions such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), brainstem stroke, or locked-in syndrome [36]. These systems create a direct, non-muscular communication channel by decoding neural signals from the brain and translating them into text or synthetic speech [37] [38]. This technical guide examines the core mechanisms, experimental protocols, and reagent solutions underpinning modern speech and texting BCIs, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a foundational understanding of this rapidly advancing field.

Core BCI Paradigms for Communication

Signal Acquisition Modalities

BCIs utilize various technologies to record brain activity. Electroencephalography (EEG), particularly non-invasive systems using electrode caps, is popular due to its relatively low cost and ease of use [36]. For higher signal fidelity, researchers employ invasive techniques such as microelectrode arrays implanted on the brain's surface to record neural activity directly from the motor cortex [37] [39]. These arrays, each smaller than a pea, capture detailed neural patterns associated with speech production [37]. Electrocorticography (ECoG) using high-density electrode arrays placed on the brain surface also provides robust neural signal capture for speech decoding [39].

Primary Communication Approaches

2.2.1 Attempted Speech Decoding This approach decodes neural signals generated when a user attempts to speak, even if no sound is produced. The brain's motor cortex generates signals for articulator movements (lips, tongue, larynx) which BCIs intercept and translate [37] [39]. This method typically provides strong, decodable neural signals but can be physically fatiguing for users with partial paralysis [37].

2.2.2 Inner Speech Decoding Inner speech (or "inner monologue") involves imagining speech without any attempted movement. Stanford Medicine scientists have demonstrated that inner speech evokes clear, though smaller, neural activity patterns in motor regions similar to attempted speech [37] [38]. While currently more challenging to decode accurately, this approach offers a less fatiguing communication channel [38].

2.2.3 Visual Evoked Potential Systems For text-based communication, P300 Event-Related Potential (ERP) systems present users with a matrix of characters or symbols. When a desired character flashes infrequently amidst common stimuli, it elicits a detectable P300 brain wave approximately 300ms after stimulus onset [40] [36]. This enables direct text generation from brain signals.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary BCI Communication Approaches

| Approach | Neural Signal Source | Best For | Accuracy/Performance | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attempted Speech | Motor cortex during speech attempts | Users with some residual movement | Higher accuracy in current systems | Physical fatigue, muscle artifact |

| Inner Speech | Motor cortex during imagined speech | Users seeking comfort & fluency | Proof-of-concept demonstrated (50-word vocab: 67-86% accuracy) [38] | Weaker signal strength, privacy concerns |

| P300 ERP Spelling | Visual cortex P300 responses | Text-based communication | ~92% accuracy with random forest classifier [36] | Limited vocabulary, visual fatigue |

Quantitative Performance Data

Recent studies demonstrate rapid advancement in BCI communication performance. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent clinical research.

Table 2: Recent Performance Metrics in Speech and Text BCI Systems

| Study Focus | Vocabulary Size | Accuracy/Intelligibility | Speed/Latency | Subject Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inner Speech Decoding (Stanford) [38] | 50 words | 67-86% accuracy (error rates 14-33%) | Not specified | 4 participants with ALS or stroke |

| Inner Speech Decoding (Stanford) [38] | 125,000 words | 46-74% accuracy (error rates 26-54%) | Not specified | 4 participants with ALS or stroke |

| Real-time Speech Synthesis (UC Berkeley/UCSF) [39] | Not specified | High intelligibility, maintains precision of non-streaming approach | Near-synchronous (<1 second from intent to first sound) | 1 participant with severe paralysis |

| P300 Symbol Selection [36] | 12 commands | 92.25% average accuracy | Not specified | 10 healthy volunteers |

| Previous Speech Synthesis (Non-streaming) [39] | Not specified | High intelligibility | ~8 seconds delay per sentence | 1 participant with severe paralysis |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Inner Speech Decoding Protocol

The Stanford inner speech study involved participants with severe speech and motor impairments who had microelectrode arrays implanted in speech-related regions of the motor cortex [37] [38]. The experimental workflow comprised:

- Training Data Collection: Participants either attempted to speak or imagined saying specific words and sentences without vocalization [38].

- Neural Signal Processing: Implanted arrays recorded neural activity patterns, with machine learning algorithms identifying repeatable patterns associated with speech elements [37].

- Phoneme-Based Decoding: Researchers trained algorithms to recognize neural patterns associated with phonemes (the smallest units of speech), then stitched recognized phonemes into words and sentences [37].

- Real-Time Testing: Participants imagined speaking whole sentences while the BCI decoded sentences in real time using both constrained (50-word) and large (125,000-word) vocabularies [38].

Inner Speech BCI Workflow

P300-Based Text Communication Protocol

The symbol-based P300 BCI protocol for intelligent home control demonstrates a standardized approach applicable to text communication [40] [36]:

- Stimulus Presentation: Users observe a flashing paradigm typically consisting of a 6×6 or 7×6 matrix of characters, numbers, or symbols. The 7×6 version includes alphabet, space, enter, and punctuation characters [40].

- Configuration Data Collection: Configuration data is obtained by having subjects watch flashes of letters in individual words. Standard configuration uses 21 characters with 30 target flashes per character [40].

- Signal Classification: Classifier weights are determined using stepwise linear discriminant analysis (SWLDA) with specific parameters (Decimation Frequency=20Hz, Max Model Features=60, Response Window 0 to 800ms after flash) [40].

- Performance Calibration: The number of sequences is configured for each subject by averaging the number of sequences that provide maximal written symbol rate. Configuration weights are calculated using all 21 characters [40].

- Accuracy Validation: System accuracy is tested by having the subject copy a 5-character word. If accuracy is ≤60%, configuration is repeated [40].

P300 BCI Texting Protocol

Real-Time Speech Synthesis Protocol

The UC Berkeley/UCSF approach for real-time speech synthesis represents a breakthrough in latency reduction [39]:

- Neural Data Sampling: The neuroprosthesis samples neural data from the motor cortex, particularly areas involved in speech production planning and articulator control [39].

- Silent Speech Training: Researchers collect training data by having subjects look at text prompts and silently attempt to speak them, establishing mapping between neural activity windows and target sentences without vocalization [39].

- AI-Based Audio Generation: For subjects without vocalization ability, researchers use pretrained text-to-speech models to generate audio targets, potentially incorporating the subject's pre-injury voice for more natural output [39].

- Streaming Implementation: The system employs speech detection methods to identify brain signals indicating speech attempt onset, enabling audio output generation within 1 second of detected speech intent [39].

- Generalization Testing: To verify the model learns genuine speech building blocks rather than pattern-matching training data, researchers test synthesis of vocabulary not included in training (e.g., NATO phonetic alphabet words) [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for BCI Communication Research

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Microelectrode Arrays | Record neural activity from brain surface | Multiple electrodes, smaller than pea-sized [37] |

| High-Density Electrode Arrays | Record from brain surface with spatial precision | Used in clinical trials for speech neuroprosthesis [39] |

| 32-Channel EEG Caps | Non-invasive neural signal acquisition | Used in P300 BCI research [36] |

| BCI2000 Software Platform | Configurable BCI system implementation | Supports checkerboard flash patterns [40] |

| Stepwise Linear Discriminant Analysis (SWLDA) | Statistical classification of neural signals | Standard parameters: Decimation Frequency=20Hz, Max Model Features=60 [40] |

| Random Forest Classifier | Machine learning for P300 detection | Used in symbol-based BCI achieving >92% accuracy [36] |

| Word Prediction Software | Enhances communication rate | WordQ version 3.4 with 5 word suggestions [40] |

Addressing Inner Speech Privacy Concerns

The potential for BCIs to accidentally decode private thoughts represents a significant ethical consideration in BCI research [37]. Stanford researchers have demonstrated two effective mitigation strategies:

- Selective Output Suppression: Training decoders to distinguish attempted speech from inner speech and silence the latter, effectively preventing decoding of inner speech while maintaining attempted speech decoding accuracy [37] [38].

- Password-Protected Decoding: Implementing a system that only decodes inner speech after detecting a specific unlock phrase (e.g., "as above, so below") imagined by the user. This system demonstrated >98% recognition accuracy for the unlock phrase [37].

Future Research Directions

The field of communicative BCIs continues to evolve with several promising research trajectories:

- Hardware Improvements: Development of fully implantable, wireless systems to increase accuracy, reliability, and ease of use [37].

- Expressive Speech Synthesis: Decoding paralinguistic features (tone, pitch, loudness) to bridge the gap to fully naturalistic speech [39].

- Multi-Modal Approaches: Combining BCIs with other assistive technologies to enhance communication robustness [36].

- Cross-Modality Generalization: Creating algorithms that work across different neural signal acquisition methods (microelectrode arrays, ECoG, non-invasive recordings) [39].